Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM), the most severe and common brain tumor in adults, is characterized by multiple somatic mutations and aberrant activation of inflammatory responses. Immune cell infiltration and subsequent inflammation cause tumor growth and resistance to therapy. Somatic loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding tumor suppressor protein p53 (TP53) are frequently observed in various cancers. However, numerous studies suggest that TP53 regulates malignant phenotypes by gain-of-function (GOF) mutations. Here we demonstrate that a TP53 GOF mutation promotes inflammation in GBM. Ectopic expression of a TP53 GOF mutant induced transcriptomic changes, which resulted in enrichment of gene signatures related to inflammation and chemotaxis. Bioinformatics analyses revealed that a gene signature, upregulated by the TP53 GOF mutation, is associated with progression and shorter overall survival in GBM. We also observed significant correlations between the TP53 GOF mutation signature and inflammation in the clinical database of GBM and other cancers. The TP53 GOF mutant showed upregulated C–C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFA) expression via nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) signaling, consequently increasing microglia and monocyte-derived immune cell infiltration. Additionally, TP53 GOF mutation and CCL2 and TNFA expression correlated positively with tumor-associated immunity in patients with GBM. Taken together, our findings suggest that the TP53 GOF mutation plays a crucial role in inflammatory responses, thereby deteriorating prognostic outcomes in patients with GBM.

Subject terms: CNS cancer, Cancer microenvironment, Cancer genetics

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM), the most fatal brain cancer, accounts for 82% patients with malignant glioma [1]. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy after surgical resection are used as standard therapy; however, owing to the recurrence of GBM, the 5-year survival rate is less than 5% [1, 2].

Genome-wide sequencing has revealed core mutations in GBM, including amplification in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and mutations in phosphatase and tensin homolog and TP53 [3]. Transcriptomic analysis demonstrated that patients with GBM exhibit different gene expression profiles, and that GBM can be classified into several subtypes [4]. Nevertheless, the development of individual mutation-specific therapeutic regimens remains poorly investigated. Presently, radiotherapy, combined with temozolomide or bevacizumab therapy, prolongs patient survival by an average of 2 months [5]. Therefore, understanding the relationship between somatic mutations and tumor characteristics is important for custom-designing individualized therapy for patients with GBM.

The tumor suppressor TP53 is a regulator of cell cycle, apoptosis, and senescence. Various stresses, such as replicative or oxidative stress, and anti-tumor therapy, activate TP53 (hereafter termed p53) by increasing its stability [6]. The activated p53 acts as a transcriptional regulator of its downstream genes such as regulators of cell cycle (CDKN1A), apoptosis (PUMA), and DNA repair (14-3-3σ and XPC). TP53 is involved in the regulation of autophagy and metabolism, indicating that p53 performs a wide range of functions [7].

Somatic alterations in TP53 are the most extensively investigated genetic variations. TP53 mutations have been detected in >90% patients with ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma and pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma [8, 9]. Approximately 30% patients with GBM harbor TP53 mutations, whereas mutations are rarely detected in thyroid carcinoma and renal clear cell carcinoma [3, 10, 11]. TP53 mutations are predominantly point mutations, which lead to amino acid substitutions in the DNA binding domain (DBD). In particular, substitution of “hotspot” arginine residues within the DBD such as R175, R248, and R273, which bind directly to DNA, prevents a TP53 loss-of-function (LOF) mutant from functioning as a transcription factor [6].

Recent findings show that mutant p53 gains de novo functions that do not occur in wild-type (WT) p53. Previous studies suggest that the gain-of-function (GOF) mutant TP53 contributes to tumor malignancies by promoting proliferation, tumor forming ability, invasiveness, and angiogenesis [12]. Additionally, inhibition of the p53 GOF mutant suppressed cancer progression, indicating that mutant p53 can act as an independent oncoprotein [13, 14]. However, several studies on GOF mutations have compared phenotypes of cell lines with different TP53 status; therefore, it is plausible that differences in these phenotypes are caused not only by the p53 GOF mutation per se, but also by the different genetic background of each cell line. Additionally, several genes, which specifically bind to mutant p53, or genes that can be regulated by TP53 GOF mutations, are known; however, a comprehensive understanding of how cell physiology is altered by TP53 GOF mutations is still limited [12]. A bioinformatics-based unbiased approach can clarify the relationship between the transcriptomic changes caused by TP53 GOF mutations and the resulting phenotypic differences; such an approach can also demonstrate clinical relevance using the patient gene expression database.

Inflammation regulates cancer progression in early and late stages [15], and inflammatory conditions increase the risk of cancer at the onset of the tumor. The most well-studied model is inflammatory bowel disease, which promotes tumorigenesis in colorectal carcinoma by causing DNA damage and providing growth-promoting cytokines [16]. In the late stage, activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) promotes cell proliferation and resistance to chemotherapy [17]. NFκB releases cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukins (ILs), and chemokines.

Cytokines downstream of NFκB promote chemotaxis and convert myeloid cells of the M1-like tumor-suppressing phenotype to the M2-like tumor-promoting phenotype [15]. Myeloid cells with M2-like phenotypes that are associated with tumor tissues, such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs), promote angiogenesis, proliferation, survival, and invasion via secretion of cytokines [18, 19]. Blocking of TAM-like polarization by inhibiting colony stimulating factor-1 receptor suppresses cancer progression, implying that TAMs play an essential role in tumor maintenance [20, 21].

Here we demonstrate that the TP53 GOF mutation promotes inflammation, which has a profound effect on patient prognosis. The genetic signature, upregulated by the TP53 GOF mutant, was closely related to the grade of the brain tumors and displayed positive correlations with inflammation-related gene signatures in the patient gene expression dataset. In particular, we observed that the TP53 GOF mutant promotes microglia and myeloid-derived immune cell infiltration by upregulating CCL2 and TNFA expression, and that the TP53 GOF mutation is associated with the tumor-associated myeloid signature. Our data also show that the association between TP53 mutation and inflammatory response is universal across cancer types, indicating that TP53 GOF mutation may significantly affect cancer progression.

Results

TP53 status correlates with malignant histology in GBM xenograft tumor

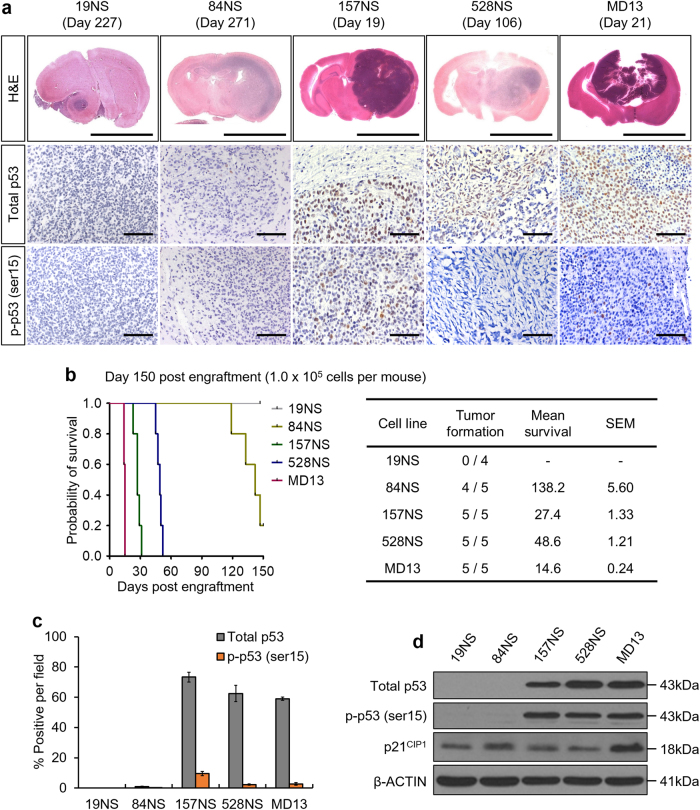

To investigate the genetic factors responsible for the histological features associated with GBM malignancies, we transplanted patient-derived GBM cells in Balb/c nu/nu mice. Compared to 19NS and 84NS tumors, 157NS, 528NS, and MD13 tumors showed an increase in tumor initiating capacity, size, cellular density, necrosis, and hemorrhage (Fig. 1a, b, Supplementary Fig. S1a). Somatic mutation in TP53 is the most prominent genetic abnormality that is closely related to malignancy; TP53-mutant tumors exhibit higher accumulation of p53 than do tumors with TP53WT [12] cDNA sequencing showed that all five GBM cell lines harbored a substitution in the P72R amino acid, which is one of the common single-nucleotide polymorphisms with intact function; therefore, this mutation is hereafter considered as WT (Supplementary Fig. S1b–d) [22]. Unlike 19NS and 84NS, 157NS, 528NS, and MD13 harbor additional amino acid substitutions, particularly the R248L substitution in 157NS and MD13, this is one of the common hotspot DBD mutations (Supplementary Fig. S1b–d) [6]. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed that the 157NS, 528NS, and MD13 tumors show relatively high p53 accumulation, whereas the 19NS and 84NS tumors showed negligible p53 expression (Fig. 1a, c). Few cells of the 157NS, 528NS, and MD13 tumors were positive for serine 15-phosphorylated p53 (p-p53), a damage-induced active form of p53. Western blot analysis showed high levels of total and phosphorylated p53 in 157NS, 528NS, and MD13, but not those of p21CIP1, a prominent downstream target of p53 (Fig. 1d). These results indicate that tumors harboring a TP53 hotspot mutation display malignant histological features and accumulate p53.

Fig. 1.

The distinct histological features of patient-derived GBM are associated with p53 expression. a Representative images of H&E staining and IHC. The date displayed above each photo indicates the time of mouse sacrifice. b Tumor forming capacities of patient-derived GBM. A Kaplan–Meier survival plot of mice grafted with the same number of each GBM cell lines (left), and a table displaying the mean overall survival (right). c Quantification of IHC provided in a. d Western blot analysis for total p53, phosphorylated p53 (p-p53, ser15), and p21CIP1. Representative microscopic images of H&E and IHC are magnified 6× (scale bar = 5 mm) and 200× (scale bar = 100 μm), respectively. The bar graph represents the mean ± SEM

GBM xenograft tumors possess TP53 LOF somatic mutation

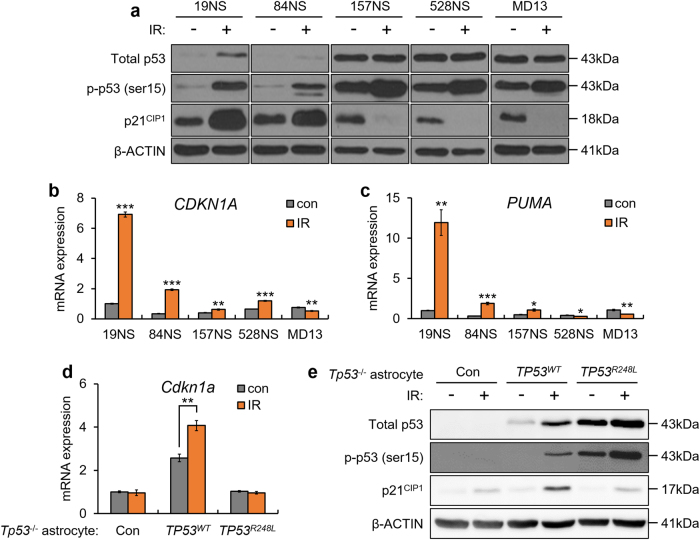

We investigated the activity of p53 as a transcriptional regulator to determine whether the TP53R248L is a LOF mutant. p53 phosphorylation and p21CIP1 levels increased in 19NS and 84NS after ionizing radiation (IR)-mediated DNA damage, but not in 157NS, 528NS, and MD13, which showed low levels of p21CIP1, similar to the results of previous studies (Fig. 2a) [7, 23–25]. The mRNA levels of CDKN1A and PUMA increased more than two-fold in IR-exposed 19NS and 84NS; however, these levels changed slightly in 157NS, 528NS, and MD13 (Fig. 2b, c). Furthermore, when ectopically expressed in astrocytes derived from TP53-/- mouse, TP53R248L did not promote p21CIP1 expression during IR (Fig. 2d, e). Our results demonstrate that expression of the TP53 mutation in 157NS and MD13 does not activate the downstream signals similar to the WT, which is a feature of LOF mutants.

Fig. 2.

Targeted sequence analysis shows TP53 LOF mutations in patient-derived GBM cell lines. a Western blot analysis for total p53, p-p53 (ser15), and p21CIP1 after treatment with 10 Gy IR. b qPCR analysis, showing mRNA expression of CDKN1A and PUMA after treatment with 10 Gy IR. c qPCR analysis, showing CDKN1A mRNA level after treatment with 10 Gy IR. d qPCR analysis, showing mRNA expression of Cdkn1a after treatment with 10 Gy IR, in Tp53-/- astrocytes transduced with TP53WT or TP53R248L. eWestern blot analysis for total p53, p-p53 (ser15), and p21CIP1 after treatment with 10 Gy IR, in Tp53-/- astrocytes transduced with TP53WT or TP53R248L. The bar graph data represent the mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, n = 3)

TP53R248L upregulates inflammation-related and chemotaxis-related transcriptome

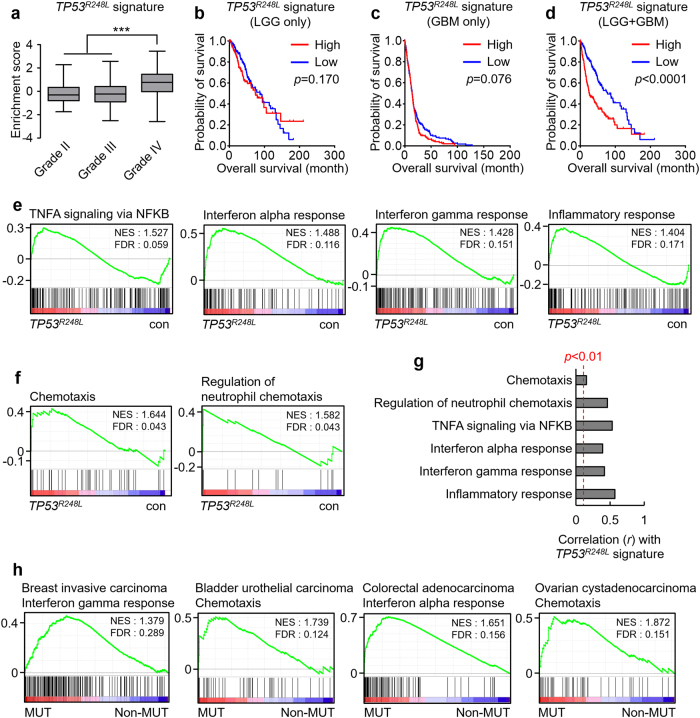

The TP53R248L-expressing xenograft tumors showed features independent of the deficiency of WT p53 activity. Therefore, we assumed that the mutant TP53 affected GBM properties via de novo GOF. To examine the transcriptomic changes mediated by the TP53 GOF, we first used RNA sequencing after overexpressing TP53R248L in 19NS (TP53WT) (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Among the differentially expressed genes, the expression levels of which are increased by TP53R248L overexpression, we selected genes with >2-fold increase in expression and a probability (PA) of ≥0.7; we considered these genes to be signature of TP53R248L (Supplementary Fig. S2, Supplementary Table 1). A single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA), performed using a gene expression dataset of low-grade glioma (LGG) or GBM patients at The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), revealed that the TP53R248L signature was relatively enriched in grade IV patients (Fig. 3a). TP53R248L signature enrichment did not affect the overall survival of patients with LGG (Fig. 3b). Among patients with GBM, the group with relatively enriched TP53R248L signature, showed shorter overall survival, although this was not statistically significant (Fig. 3c). Conversely, the same analysis, conducted on the combined dataset of patients with LGG and GBM, showed that the overall survival rate of the TP53R248L signature-enriched group was considerably reduced (Fig. 3d), indicating that the TP53R428L signature is closely related to tumor aggressiveness.

Fig. 3.

TP53R248L mutation promotes the progression of GBM and enriches inflammation-related signatures. a Tumor grade-dependent enrichment of the TP53R248L signature in patients with low-grade glioma or GBM (***P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA). b–d Kaplan–Meier survival plots showing the overall survival of patients with respect to the TP53R248L signature enrichment. e GSEA demonstrating the enrichment of inflammation-related signatures in TP53R248L-overexpressing 19NS GBM cell line. f GSEA showing the enrichment of chemotaxis-associated signatures in TP53R248L-overexpressing 19NS GBM cell line. g Correlations between TP53R248L signature and inflammation/chemotaxis-related signatures in the TCGA GBM patient expression dataset. h GSEA showing the enrichment of inflammation/chemotaxis-related signatures in various types of cancer with TP53 DNA binding domain (DBD)-mutated (MUT) or non-mutated (non-MUT)

To better understand the biological significance of the transcriptomic changes that occur during TP53R248L expression, we performed GSEA using the RNA sequencing results and hallmark signatures. Interestingly, inflammation-related signatures, including TNFA via NFκB signaling, and interferon and inflammation responses, were enriched in 19NS overexpressing TP53R248L (Fig. 3e). Additionally, the chemotaxis-related gene signatures were enriched (Fig. 3f), highlighting the relationship between the TP53 GOF mutation and inflammation.

Next, we examined whether the TP53R248L-mediated transcriptomic changes, which activate inflammation-related responses, recapitulate the changes in patient expression profile. ssGSEA using the TCGA GBM patient dataset showed that the enrichment scores of inflammation-related and chemotaxis-related gene signatures correlated positively with that of the TP53R248L signature (Fig. 3g). Next, we accessed the TCGA expression datasets for cancer types with frequent TP53 mutation. GSEA showed that the immune response-related signature was prominently enriched in groups possessing the TP53 DBD mutation (Fig. 3h). Therefore, it is likely that TP53 GOF mutation can cause immune-related pathological differences in GBM and other cancers.

TP53R248L GBM xenograft tumors display higher intratumoral immune cell infiltration

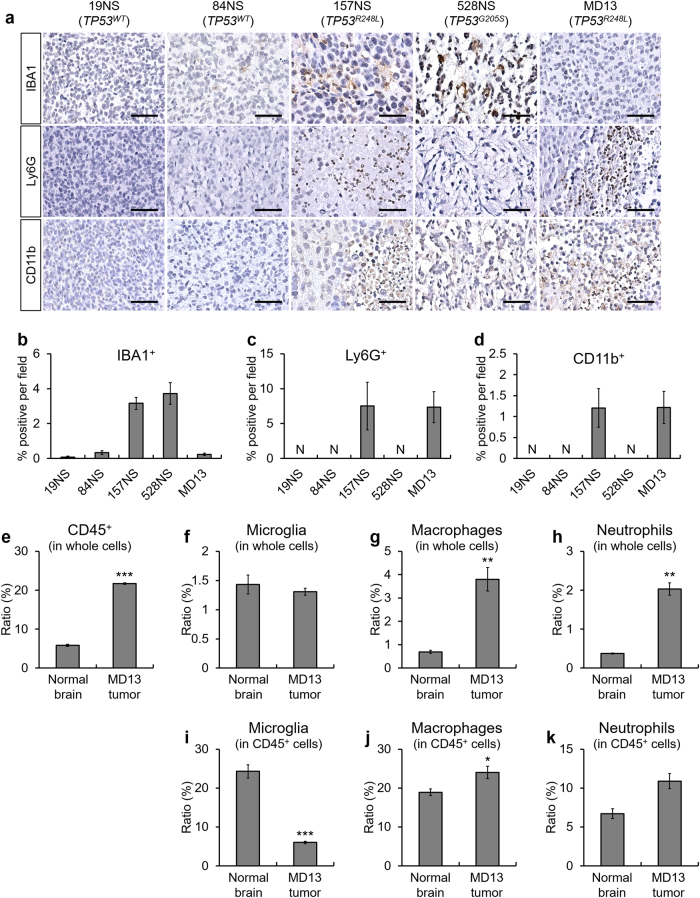

After identifying the TP53R248L-induced transcriptomic changes involved in inflammation and chemotaxis, we investigated whether the TP53R248L-expressing tumors show increased presence of immune cells. We immunohistochemically assessed the markers of four different types of immune cells: IBA1 (microglia), F4/80 (macrophage), Ly6G (neutrophil), and CD11b (monocyte-derived lineage) (Fig. 4a). Tumors with TP53WT from 19NS and 84NS cells showed scant immune cell infiltration, whereas markedly elevated immune cell infiltration was detected in the 157NS, 528NS, and MD13 tumors (Fig. 4a–d, Supplementary Fig. S3). Patient-derived GBM lines, such as MD30, 83NS, and 1123NS, also harbor TP53R248L mutation, with distinct tendencies of hallmark signature enrichment (Supplementary Fig. S4a, b). The tumors from these cell lines also displayed infiltration of various immune cells (Supplementary Fig. S4c–f).

Fig. 4.

TP53R248L xenograft tumor shows high immune cell population infiltration. a Representative IHC images showing immune cell markers including IBA1, Ly6G, and CD11b. Three mice per cell lines were used except for 19NS. Brain tumor tissue from one mouse was used for 19NS because of its low tumor-forming ability (Fig. 1b). Representative microscope images are magnified 200× (scale bar = 100 μm). b–d Quantification of IHC for the composition of IBA1+, Ly6G+, and CD11b+ immune cells, respectively. e–k Flow cytometry measurement of immune cell composition in the MD13 xenograft brain tumor and normal brain. Dot plots showing the results of the flow cytometry analyses are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. The bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. N indicates no detection

Next, we performed flow cytometry to evaluate tumor immune cell composition and circulation in tumor-grafted mice (Fig. 4e–k, Supplementary Figs. S5–S8). Compared to the normal brain, MD13 xenograft tumors contained large numbers of CD45+ cells, macrophages (CD45+/CD11b+/F4/80+), and neutrophils (CD45+/CD11b+/Ly6G+) (Fig. 4e, h, Supplementary Fig. S5). Among CD45+ cells, both microglia and macrophages express IBA1. Hence, we used an antibody against TMEM119 to specifically detect the microglia [26]. The proportion of microglia among the CD45+ cells decreased in the MD13 tumor, whereas those of macrophages and neutrophils increased slightly or did not change significantly, respectively (Fig. 4i, k, Supplementary Fig. S5). In addition, MD13-grafted mice showed increase in the number of circulatory macrophages and neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. S6a–d). Similarly, we observed alterations in immune cell composition in the tumor and circulation of 157NS-grafted mice (Supplementary Figs. S7–S8). These results suggest that TP53R248L actively regulates immune cell recruitment and affects the composition of intratumoral immune cells in GBM, along with systemic inflammation.

TP53R248L promotes chemotaxis

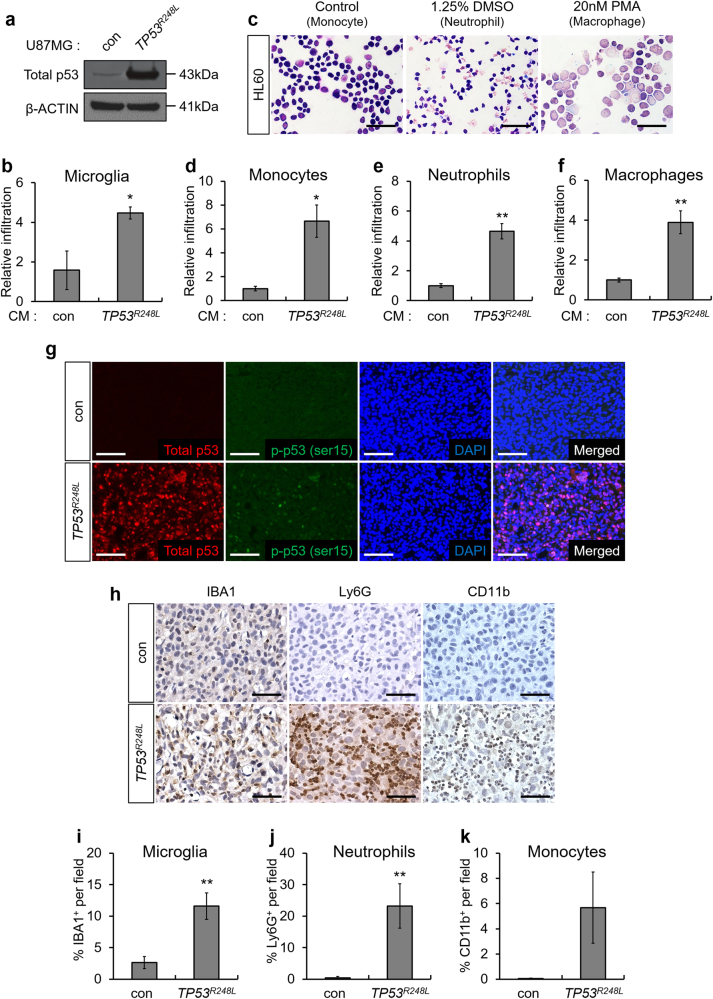

To investigate whether ectopically expressed TP53R248L promotes chemotaxis, we overexpressed TP53R248L in U87MG because 19NS rarely forms xenograft tumors (Fig. 1b). Transwell migration assay showed an increase in the number of migrating microglia in the TP53R248L-conditioned medium (CM) compared to that in TP53WT-CM (Fig. 5a, b). To model the infiltration of immune cells of myeloid lineage, we used the HL60 premyelocytic monocyte-like cell line, and differentiated them into neutrophils and macrophages using dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and phorbol myristic acid (PMA), respectively (Fig. 5c) [27, 28]. Transwell migration assay showed that TP53R248L-CM increased migration of HL60-derived immune cells (Fig. 5d–f).

Fig. 5.

Ectopic expression of TP53R248L promotes immune cell infiltration. a Western blot analysis showing p53 expression in TP53R248L-overexpressing U87MG cell line. b Relative infiltration rate of BV2 microglia grown in conditioned medium (CM) generated using control U87MG and TP53R248L-overexpressing U87MG cell lines (n = 3). c Differentiation of HL60 to neutrophils and macrophages was confirmed by Diff-Quik staining (magnification 400×, scale bar = 50 μm). d–f Relative infiltration rate of HL60-derived monocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages grown in CM from control U87MG and TP53R248L-overexpressing U87MG cell lines (n = 3). g Representative microscopic images of fluorescent IHC showing total p53 and p-p53 (ser15) in orthotopically transplanted tumors generated using TP53R248L-overexpressing U87MG cell line (magnification 200×, scale bar = 100 μm). h Representative microscopic images of IHC showing expression of immune cell markers such as IBA1, Ly6G, and CD11b (magnification 200×, scale bar = 100 μm). i–k Quantification of IHC showing the composition of IBA1+, Ly6G+, and CD11b+ cells. The bar graphs represent mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001)

Next, we, investigated whether TP53R248L overexpression stimulated immune cell recruitment in vivo. IHC showed that the infiltration of IBA1+ microglia and Ly6G+ neutrophils in the TP53R248L-overexpressing U87MG tumors was markedly increased compared to that in control tumors, whereas infiltration of CD11b+ monocytes did not increase significantly (Fig. 5g–k). Similarly, overexpression of TP53R248L promoted the infiltration of IBA1+ microglia and F4/80+ macrophages in 84NS xenograft tumor (Supplementary Fig. S9). Collectively, our results demonstrate that the GOF mutant TP53R248L promotes chemotaxis.

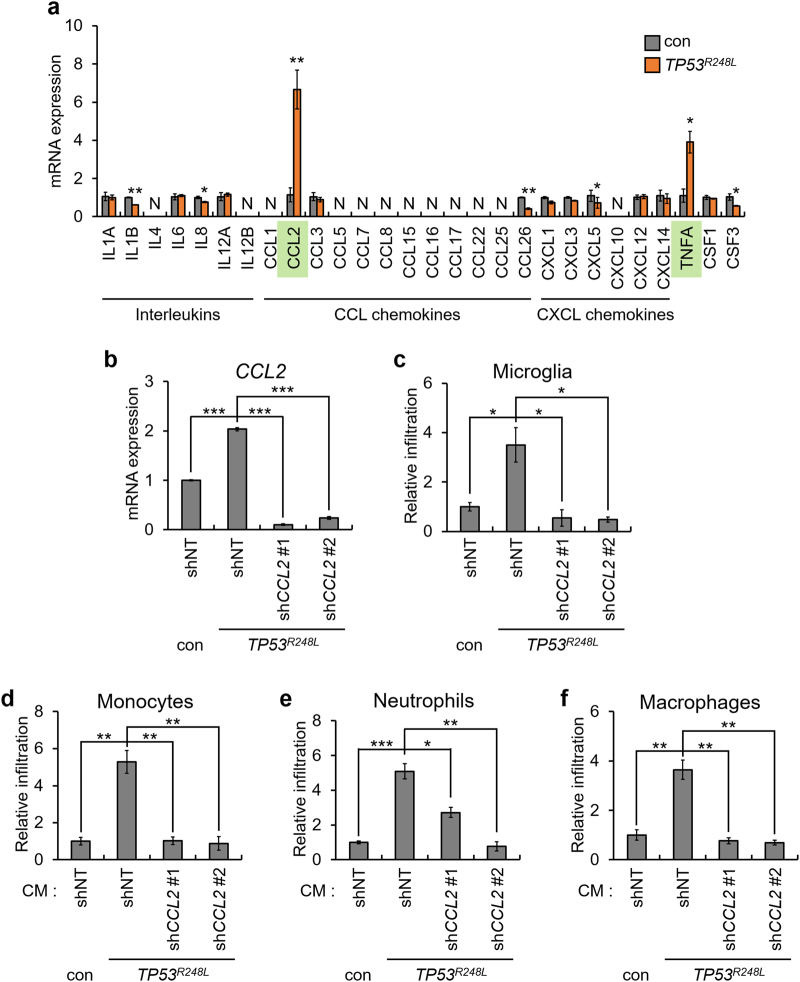

TP53R248L upregulates CCL2 and TNFA to promote chemotaxis

To investigate the mechanism underlying the TP53R248L-mediated promotion of chemotaxis, we determined the expression of cytokines with chemotactic ability. Among cytokines, the expression of CCL2 and TNFA markedly increased upon TP53R248L overexpression (Fig. 6a). Considering that TP53R248L promotes infiltration of the mouse-derived BV2 microglia, and that TNFα lacks interspecies reactivity between human and mouse, we hypothesized that CCL2 predominantly affects chemotaxis [29]. Hence, we knocked down CCL2 using short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) in TP53R248L-overexpressing U87MG cells (Fig. 6b). TP53R248L overexpression-mediated increase in immune cell infiltration was reduced by CCL2 knockdown, indicating that p53R248L promotes chemotaxis via CCL2 (Fig. 6c–f).

Fig. 6.

TP53R248L promotes immune cell infiltration by upregulating CCL2 and TNFA. a qPCR analysis showing expression of chemoattractive cytokines in TP53R248L-overexpressing U87MG cell line. b qPCR analysis confirming shRNA-mediated knockdown of CCL2 in TP53R248L-overexpressing U87MG cell line. shNT indicates non-targeting control shRNA. c–f Relative infiltration rate of BV2 microglia, HL60-derived monocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages grown in CM from a TP53R248L-overexpressing U87MG cell line with or without CCL2 knockdown, and control counterpart cells. The bar graphs represent mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n = 3)

Next, we investigated whether CCL2 knockdown inhibited the progression of TP53R248L-expressing tumors. Decrease in the CCL2 expression did not affect proliferation of TP53R248L-expressing U87MG cells (Supplementary Fig. S10a). In addition, CCL2 knockdown prolonged mean overall survival of mice grafted with TP53R248L-expressing U87MG, although it was not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. S10b). Thus, our observations suggest that TP53R248L-mediated increase in CCL2 expression may promote immune cell recruitment, although it is not exclusively responsible for tumor progression.

We investigated the mechanism via which mutant p53 regulates CCL2 expression. Previous studies suggest that p53WT suppresses CCL2 expression, while concurrently, mutant p53 may functionally block p53WT in a dominant-negative manner [6, 30]. Thus, we confirmed that TP53R248L acts as a dominant-negative mutant and suppresses the p53WT-mediated negative regulation of CCL2 expression. CCL2 mRNA level was not reduced in TP53WT cells by IR-mediated activation of p53, and the dominant-negative deletion mutant TP53 (TP53DD) reduced CCL2 and TNFA expression (Supplementary Fig. S11a–d). These results indicate that CCL2 and TNFA expression levels are not increased by the dominant-negative effect of TP53R248L on TP53WT.

As observed in the transcriptomic analyses, overexpression of TP53R248L induced enrichment of gene signatures related to NFκB signaling (Fig. 3e). Similarly, a previous study has shown that mutant p53 activates the NFκB signaling pathway in an inflammatory microenvironment [31]. Thus, we hypothesized that TP53R248L increases CCL2 and TNFA expression via the NFκB signaling pathway. We observed that treatment with the NFκB inhibitor, Bay11-7085, inhibited the TP53R248L-mediated increase in CCL2 and TNFA expression, indicating that TP53R248L upregulates CCL2 and TNFA by increasing NFκB signaling (Supplementary Fig. S12a, b).

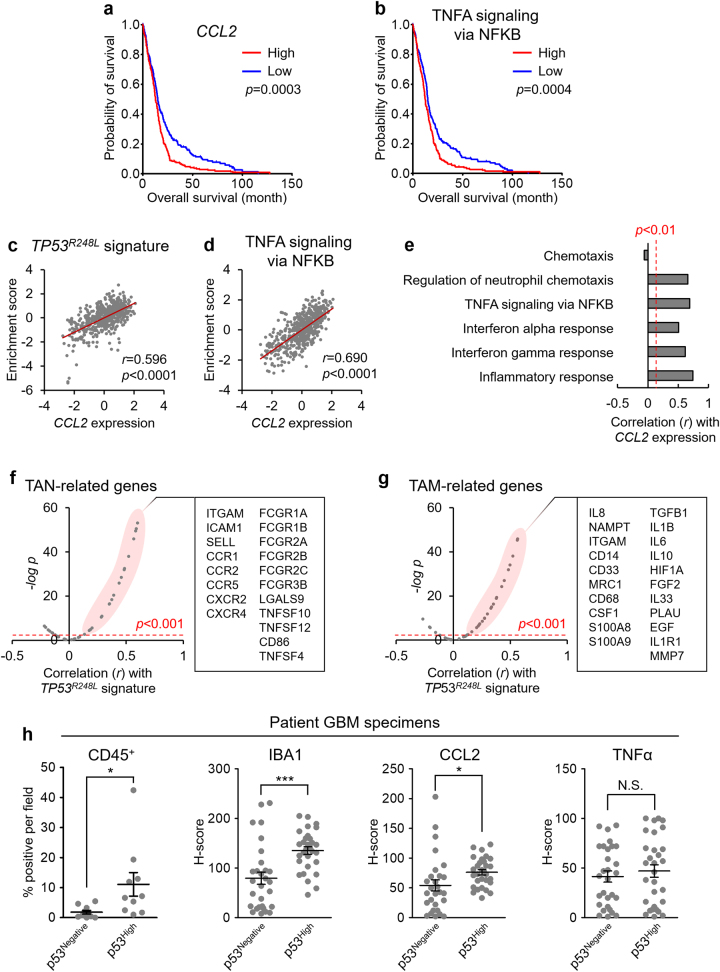

TP53R248L-derived inflammatory responses critically affect patient prognosis

Since the TP53R248L signature affects patient survival and promotes inflammation, we analyzed the TCGA dataset of patients with GBM to determine the clinical relevance of CCL2 and TNFA expression. CCL2 expression and enrichment of TNFA signaling via NFκB negatively affect patient survival (Fig. 7a, b). CCL2 expression correlated positively with enrichment scores of the TP53R248L and TNFA signaling signature; there was also a significant correlation with signatures associated with inflammation and chemotaxis (Fig. 7c–e).

Fig. 7.

CCL2 and TNFA, induced by TP53R248L, affect patient prognosis and tumor-associated myeloid signatures. a, b Kaplan–Meier survival plots showing overall survival of patients with respect to CCL2 expression and enrichment of TNFA signaling via NFκB signature. c, d Correlation between CCL2 expression and enrichment scores of the TP53R248L signature, and TNFA signaling via NFκB signature. e Correlations between TP53R248L signature and inflammation/chemotaxis-related signatures. f, g Correlations between the TP53R248L signature and expression of TAN-related and TAM-related genes. All bioinformatics analyses were performed with the TCGA GBM patient gene set. h Quantification of IHC for CD45, IBA1, CCL2, and TNFα in the patient-derived GBM tissues, grouped by p53 levels (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; n = 10 for each group)

Next, we determined whether TP53R248L regulated the TAM-like conversion of immune cells to establish a tumor-favoring inflammatory microenvironment [15]. Notably, the expression of TAN-related and TAM-related genes showed a strong positive correlation with the TP53R248L signature enrichment score and CCL2 and TNFA expression in the TCGA dataset of patients with GBM (Fig. 7f, g, Supplementary Fig. S13a–d) [32, 33].

To address the clinical significance of inflammatory responses caused by the TP53 GOF mutations, we performed IHC against CD45, IBA1, CCL2, and TNFα using patient GBM tissues, which are negative (p53Negative) or highly positive (p53High) for p53. p53High GBM tissues exhibited increase in the number of CD45+ cells and IBA1+ microglia (Fig. 7h, Supplementary Fig. S14). Similarly, CCL2 expression was higher in the p53High GBM, whereas TNFA expression did not show any difference (Fig. 7h, Supplementary Fig. S14). Furthermore, ssGSEA using the IVY Glioblastoma Atlas Project (IVY GAP) database revealed that the TP53R248L signature correlates positively with inflammation-related signatures in perinecrotic zones and cellular tumor regions (Supplementary Fig. S15). Taken together, our results suggest that the TP53 GOF mutation facilitates inflammatory responses, which may eventually affect tumor progression.

Discussion

The TP53 LOF mutation results in uncontrolled proliferation and desensitization of cancer cells to therapies; however, the effect of a TP53 mutation on prognostic outcomes is still uncertain for GBM [7]. A clinical study indicated that patients with TP53 mutation are less sensitive to treatment; however, other studies did not indicate any significant reduction in the overall survival rate of patients with TP53 mutations [34–36]. No significant differences were observed in the resistance of several GBM cell lines with TP53 mutation to temozolomide in vitro [37]. Interestingly, TP53 mutations did not affect prognosis; however, the overall survival rate of a group of patients, with overexpression of mutant TP53, was significantly reduced [36]. Similarly, several studies have also shown that overall survival is reduced in patients with high TP53 immunoreactive glioma [38, 39], suggesting clinical significance of the TP53 GOF mutation.

Inflammation accelerates cancer progression in GBM and enables resistance to treatment. Analysis of tissue samples from patients, used for selecting prognostic gene signatures, indicated that predictive gene signatures were mostly associated with inflammatory response [40]. Similarly, increase in the number of neutrophils and inflammatory serum protein levels is associated with poor prognosis [41, 42]. A recent transcriptome-wide analysis revealed that recurrent tumors undergo microenvironmental evolution, which involves increased infiltration of tumor-associated microglia and macrophages, and that the composition of TAM is associated with earlier recurrence [43]. These results indicate that inflammation is important for predicting the severity and treatment outcome of GBM.

Our observations support previous experimental evidence indicating that inflammation and TP53 GOF mutations are important determinants of prognosis in GBM. Overexpression of TP53R248L induced transcriptomic alterations, resulting in enrichment of inflammation-related gene signatures. The TP53R248L signature was related to the progression and prognosis of brain tumors. TP53R248L promoted infiltration of immune cells by CCL2 upregulation via NFκB signaling. In addition, we observed that TP53 GOF mutation increased immune cell infiltration and CCL2 expression in specimens of patients with GBM.

TNFα facilitates tumor vascularization and hemorrhagic necrosis, and also affects therapeutic sensitivity, primarily through NFκB signaling [44]. Recent studies showed that the mesenchymal subtype of GBM is more invasive than the proneural subtype, and is associated with poor prognosis after treatment [3, 45]. NFκB is a regulator of proneural–mesenchymal transition, maintenance, and resistance to radiation therapy in the mesenchymal subtype of GBM [46, 47]. 157NS and MD13 harbor EGFR mutation (EGFRvIII), which may affect NFκB signaling activity [48]. However, 84NS, which shows less malignant phenotype than 157NS and MD13, also expresses EGFRvIII. In addition, TP53R248L promoted NFκB signaling in 19NS and U87MG, which do not express EGFRvIII [48]. Thus, our observation that NFκB-related inflammatory response is facilitated by TP53R248L irrespective of EGFR status implies that the TP53 GOF mutation may broadly influence properties of GBM.

We observed that CCL2, upregulated by TP53R248L, promotes chemotaxis. CCL2 not only attracts microglia into the GBM, but also promotes the invasion of GBM cells by upregulating IL6 via CCR2 [49]. CCL2 induces the polarization of monocytes to TAM, which was also observed in the patient database analysis [50]. CCL2 recruits regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells to suppress anti-tumor immunity, suggesting that the TP53 GOF mutation may neutralize responses to immunotherapy [51]. Since our experiments were conducted using mice lacking mature lymphoids, the effect of TP53 GOF mutation on tumor-associated acquired immunity should be validated by further studies.

In conclusion, we have shown that the TP53 GOF mutation results in transcriptome-wide changes that promote inflammatory responses and facilitate chemotaxis via NFκB-mediated upregulation of CCL2 (Supplementary Fig. S16). Our results indicate that the association between the TP53 GOF mutation and tumor-associated inflammation may be a critically disruptive feature in therapies against GBM.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

Patient-derived GBM lines, including 19NS, 84NS, 157NS, 528NS, MD13, MD30, 83NS, and 1123NS, were kindly provided by Dr. Ichiro Nakano (Department of Neurosurgery, Ohio State University, USA). These cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/F12 (Lonza, Basel, SUI) supplemented with 0.2% B27 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, R&D Systems), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies Carlsbad, CA, USA), 2 mmol/L L-glutamine (Life Technologies), and 50 μg/mL gentamicin (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA). U87MG was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Tp53-/- mouse astrocytes were kindly provided by Drs. Ronald DePinho and Lynda Chin (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, USA) [52]. The BV2 mouse microglial cell line was a gift from Dr. Jong Bae Park (National Cancer Center, Korea). U87MG, Tp53-/- astrocytes, and BV2 were cultured in DMEM (Lonza) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biotechnics Research, Lake Forest, CA, USA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, and 50 μg/mL gentamicin. HL60 cells, a gift from Dr. Taehoon Chun (Korea University, Korea), were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 (RPMI-1640; Lonza) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, and 28 mmol/L HyClone HEPES (General Electronics Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK).

Cell line construction

To construct the TP53R248L-overexpressing U87MG and 19NS GBM cell lines and the Tp53-/- astrocyte cell line, TP53WT and TP53R248L coding DNA sequences (CDS) were cloned into a pLL CMV puro mammalian lentiviral expression vector. To construct the TP53R248L-overexpressed CCL2 knocked down U87MG cell lines, TP53R248L CDS was cloned into a pLL CMV blast vector. pLKO.1 puro vector-cloned shRNAs targeting CCL2 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA; shCCL2 #1: MISSION shRNA NM_002982.3-108s21c1; shCCL2 #2: MISSION shRNA NM_002982.3-214s21c1). Non-targeting shRNA (pLKO.1 shNT puro, Sigma-Aldrich) was used as control.

To produce the lentivirus, each expression vector was transfected into transformed human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK293T) with second-generation lentiviral packaging plasmids pMD2.G and psPAX2 using the PolyExpress transfection reagent (Excellgen, Rockville, MD, USA). Twenty-four hours after transfection, the culture medium was harvested, incubated with Lenti-X concentrator (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA, USA), and centrifuged to obtain the concentrated lentivirus. The cells were infected with the lentiviruses in the presence of 6 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h. Overexpression was confirmed by western blot and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) (see “qPCR analysis” in Materials and Methods).

Orthotopic GBM engraftment

19NS (1 × 105 cells), 84NS (1 × 104 cells), 157NS (1 × 103 cells), 528NS (1 × 103 cells), MD13 (1 × 103 cells), MD30 (1 × 103 cells), 83NS (1 × 103 cells), 1123NS (1 × 103 cells), and U87MG (1 × 105 cells) (Fig. 5) and 3 × 105 cells (Supplementary Fig. S10) were harvested, washed, and resuspended with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Sigma-Aldrich). Specifically, 1 × 105 cells of 19NS, 84NS, 157NS, 528NS, and MD13 were prepared for the experiment shown in Fig. 1b. Living cells were counted after staining with trypan blue (Invitrogen), and a defined number of cells was grafted into the caudate putamen (coordinates relative to the bregma; medial-lateral +2 mm, dorsal-ventral −3 mm) of mice brains using a stereotaxic injection device (JD-SI-02; Jeung Do Bio & Plant, Seoul, Korea). Tumor-bearing mice were sacrificed when the body weights decreased below 15 g. Cardiac perfusion with PBS, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) perfusion, was performed to wash out the blood and fix the tissue, respectively. The removed brains were additionally fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h and paraffin-embedded for further histological analysis. Animal experiments were performed in the specific pathogen-free facility with the approval of the Korea University Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee (approval no. KUIACUC-2017-35).

Histological analysis of mouse xenograft tumors

Paraffin-embedded tissues were micro-sectioned at the thickness of 4 μm. Tissue sections were used for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and IHC. H&E was purchased from Merck, and staining was conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Microscopic images were obtained using an Axio Imager M1 upright microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, German); the intensity of the IHC stain was quantified using the Metamorph Offline software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

For chromogenic IHC, tissue sections were boiled for 20 min in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval; the buffer contained 10 mM sodium citrate (SAMCHUN Chemical, Seoul, Korea) and 0.05% Tween-20 (LPS Solution, Daejeon, Korea). Endogenous peroxidase was blocked in 9:1 mixture of methanol (DUKSAN Science, Seoul, Korea) and 30% H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min. The tissue sections were sequentially incubated with primary antibodies, washed, incubated with secondary antibodies, and developed using the Vectastain ABC horse radish peroxidase (HRP) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and DAB peroxidase substrate kits (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The tissue sections were subsequently counterstained using hematoxylin.

For fluorescent IHC, tissues were prepared using the same procedure as that for chromogenic IHC but without blocking the endogenous peroxidase. After incubation with the primary and fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies, the tissues were stained with 1 μg/mL 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Sigma-Aldrich).

IHC of patient GBM specimens

All GBM specimens were collected with written informed consent under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Samsung Medical Center (2010-04-001 and 2010-04-004). After obtaining signed informed consent, tumor specimens were obtained from patients with GBM and embedded into a paraffin block.

Tissue sections of paraffin-embedded GBM specimens were stained with antibodies against p53, IBA1, CCL2, and TNFα. Vectra 3.0 automated quantitative pathology imaging system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and inForm® Tissue Finder™ software (PerkinElmer) were used for the quantification. At least three fields were randomly selected for each specimen, while 1–2 fields were analyzed for the small-sized specimen. The H-score was calculated from the percentage of cells (0–100%) in each intensity category (0, 1+, 2+, and 3+) after automatic segmentation of cells into cytoplasm and nucleus. The final H-score was on a continuous scale between 0 and 300. CD45+ cells were quantified by calculating the percentage of IHC-positive cells in the 10 randomly selected fields per specimen.

TP53 protein coding region-targeted sequencing

RNA samples, extracted from 19NS, 84NS, 157NS, 528NS, and MD13, were processed for cDNA synthesis using the RevertAid first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). TP53 coding sequence was amplified from the cDNA samples of each GBM cell line using Ex Taq (Takara, Shiga, Japan) and a set of primers as follows: forward 5′-GTGACACGCTTCCCTGGATT-3′ and reverse 5′-GCTGTCAGTGGGGAACAAGA-3′ (45 cycles for 19NS and 84NS, and 30 cycles for 157NS, 528NS, and MD13). Amplicons from each cDNA sample were cloned into the pGEM T Easy plasmid, followed by bacterial transformation. More than eight colonies harboring the amplicon-cloned plasmid were selected for each GBM line; the plasmid DNA was extracted and sequenced, targeting the cloned TP53 CDS. Nucleotide substitutions were considered mutations only when the substitutions were detected in all the plasmid samples extracted from the colonies of each GBM line. The results, presented as sequencing peaks, were generated using Chromas 2.6.4 (Technelysium, South Brisbane, Australia).

qPCR analysis

cDNA was synthesized from the extracted RNA using RevertAid first strand cDNA synthesis kit. Genomic DNA was extracted using Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). qPCR analysis was conducted using the CFX Connect real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 18S ribosomal RNA and GAPDH were used as housekeeping controls for human and mouse cells, respectively. The sequences of the PCR primers for each TP53 exon were obtained from the International Agency for Research on Cancer TP53 database (p53.iarc.fr). The other primers used for the analyses are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Western blot analysis

Protein extracts from whole-cell lysates were prepared using RIPA lysis buffer (LPS Solution) containing 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor (Roche, Basel, Swiss). Protein was quantified using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Protein extracts (30 μg) were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Pall, Cortland, NY, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat skim milk, followed by incubation with primary antibodies. After incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, target proteins were visualized using the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Elpis Biotech, Daejeon, Korea).

Flow cytometry of the immune cells

Brain xenograft tumors were resected from mice grafted with MD13 (n = 3) or 157NS (n = 3). Similarly, brains were collected from mice without engraftment (n = 6), and blood and spleens were collected from all animals. Trypsin-mediated digestion was used to dissociate brain and brain tumor tissues into single cells, and splenocytes were physically dissected from the spleens. Erythrocytes were eliminated from the tissue-derived cells and blood using Gey’s balanced salt solution. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with the following antibodies (1:200 in RPMI medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum): CD45-APC, TMEM119, Ly6G-PE, CD11b-FITC, and F4/80-PE. Cells were washed with PBS and additionally incubated with Alexa 594 anti-rabbit IgG (1:500) for detecting microglia. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using FACSVerse (BD Biosciences).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: total p53 (DO-1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), phospho-p53 (ser15) (9284; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), p21CIP1 (C-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), β-actin (C4; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CD45 (2B11 + PD7/26; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), CD45-APC (561018; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), human IBA1 (ab5076; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse IBA1 (019-19741; Wako, Osaka, Japan), TMEM119 (ab210405, Abcam), Ly6G (551459; BD Biosciences), Ly6G-PE (551461; BD Biosciences), CD11b-FITC (AAS28610c; Antibody Verify, Las Vegas, NV, USA), CCL2 (ab9669; Abcam), TNFα (559071; BD Biosciences), HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (Thermo Fisher Scientific), HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (Thermo Fisher Scientific), biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories), biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories), biotinylated anti-goat IgG (Vector Laboratories), Alexa 594 anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen), Alexa 594 anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen), and Alexa 488 anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen).

Treatment with IR

Cells were harvested and stained with trypan blue to count living cells. They were subsequently treated with 10 Gy of gamma irradiation by exposure to 137Cs isotope using an IBL 473C irradiator (Pharmalucence, Billerica, MA, USA). After 16 h, the cells were harvested to extract protein and RNA for western blot and qPCR, respectively.

Immune cell infiltration assay

For the BV2 microglial infiltration assay, 6 × 105 U87MG cells were seeded on a 60-mm culture dish. After 24 h, the culture medium was replaced with 2 mL DMEM without supplementation. The culture medium was harvested after 24 h and used as CM in further analysis. BV2 cells were serum-starved in DMEM without supplementation for 24 h; then, 5 × 104 cells per well were loaded into the upper chamber of a 6.5-mm Transwell with 8.0-μm pore (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) coated with 10% Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and 0.2% gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich). The lower chamber was filled with 700 μL CM. After 24 h, cells on the bottom of the upper chamber, which had infiltrated across the Matrigel, were stained with crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich). Staining intensity was quantified using the Metamorph Offline software.

HL60 cells were differentiated into neutrophils and macrophages by treatment with 1.25% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) and 20 nM PMA (Sigma-Aldrich) for 72 h, respectively. Differentiated HL60 cells were confirmed by Diff-Quik staining (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan). Microscopic images were acquired using an Axio Imager M1 upright microscope. CM was generated as described above; however, RPMI-1640 medium was used instead of DMEM. HL60 cells (1 × 105) were loaded into the upper chamber of a 6.5-mm Transwell with 5.0-μm pore (Corning), and the lower chamber was filled with 800 μL CM. After 24 h, the cells that had infiltrated into the CM of the lower chamber were harvested and counted using a LUNA-II automated cell counter (Logos Biosystems, Anyang, Korea).

In vitro cell growth analysis

For in vitro cell growth analysis, TP53R248L-overexpressing U87MG, with or without CCL2 knockdown, were seeded onto a 6-well plate (1.0 × 105 cells per well). Cell confluence was quantified using the IncuCyte ZOOM system (ESSEN Bioscience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Inhibition of NFκB signaling

To block NFκB signaling, 10 μM Bay11-7085 (Merck, Darmstadt, German) was added to serum-free DMEM. Cells were harvested after 24 h, RNA was extracted, and cDNA was sequentially synthesized and processed for qPCR as described above.

Bioinformatics analysis

RNA sequencing was performed by the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI, Shenzen, China). Raw fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) and probability values (PA) calculated by the performer’s algorithm were used for further analyses. Genes with PA > 0.7, the expression levels of which were increased by more than 2-fold after overexpression of TP53R248L, were grouped and designated as the TP53R248L signature (GSE101980).

A gene expression dataset of patients with GBM and a combined dataset of patients with LGG and GBM, compiled by TCGA, was downloaded from the GlioVis data portal [53]. Patient gene expression datasets of breast invasive carcinoma, bladder urothelial carcinoma, colorectal adenocarcinoma, and ovarian cystadenocarcinoma were compiled by TCGA and downloaded from cBioPortal. A gene expression dataset of patient-derived GBM lines was provided by Dr. Ichiro Nakano. A dataset of sub-tumor localization-specific gene expression was downloaded from the IVY GAP.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted using GSEA version 3.0 (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA) and the RNA sequencing data consisting of triplicate FPKM values for each gene. Hallmark signatures, including TNFA signaling via NFKB, interferon alpha and gamma responses, and inflammatory response, were obtained from Molecular Signature Database (MSigDB). The gene sets of Chemotaxis and Regulation of neutrophil chemotaxis were also downloaded from MSigDB. The result was considered statistically significant when the false discovery rate was < 0.3. Single-sample GSEA (ssGSEA) was conducted with ssGSEAProjection version 8 (Broad Institute). To investigate the grade-dependent enrichment of the TP53R248L signature, as well as correlations among gene expression and enrichment of gene sets, gene expression values and enrichment scores were normalized as z-scores. The extent of correlation is displayed as a correlation coefficient (r).

Kaplan–Meier survival plots were generated using SPSS statistics (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). TAN-related and TAM-related genes were quoted from previous studies [32, 33], and the correlations were investigated using the expression dataset of GBM patients. Heat maps were generated using the Genesis software [54].

Statistics

Data presented as bar graphs are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Data were analyzed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistics for bioinformatics analyses are explained above (see “Bioinformatics analysis” in Materials and methods).

Supplementary information is available at Cell Death and Differentiation’s website.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Joonbeom Bae, Dr. Chang-Yong Choi, and Sang-Pil Choi from Korea University for their advice on experiments related to immune cells, and Ock Ran Kim (Seoul National University Hospital) for advice on histological analyses. This work was supported by grants to Hyunggee Kim from the National Research Foundation (NRF) (2015R1A5A1009024 and 2017M3A9A8031425), Next-Generation Biogreen 21 Program (PJ01107701), Brain Korea 21 Plus, and Korea University, from the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) (HI14C3418) to D-HN, and from the NRF (2016M3C7A1913844) to SHK. The bio-specimens for this study were provided by Samsung Medical Center Biobank.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Do-Hyun Nam, Phone: +82234103497, Email: nsnam@skku.edu.

Hyunggee Kim, Phone: +82232903059, Email: hg-kim@korea.ac.kr.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41418-018-0126-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Omuro A, DeAngelis LM. Glioblastoma and other malignant gliomas: a clinical review. J Am Med Assoc. 2013;310:1842–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, Rouse C, Chen Y, Dowling J, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2007–2011. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:iv1–63. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155:462–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chinot OL, Wick W, Mason W, Henriksson R, Saran F, Nishikawa R, et al. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy–temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:709–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001008. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bieging KT, Mello SS, Attardi LD. Unravelling mechanisms of p53-mediated tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:359–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–15. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489:519–25. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell. 2014;159:676–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499:43–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller PA, Vousden KH. Mutant p53 in cancer: new functions and therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:304–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexandrova EM, Yallowitz AR, Li D, Xu S, Schulz R, Proia DA, et al. Improving survival by exploiting tumour dependence on stabilized mutant p53 for treatment. Nature. 2015;523:352–6. doi: 10.1038/nature14430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soragni A, Janzen DM, Johnson LM, Lindgren AG, Thai-Quynh Nguyen A, Tiourin E, et al. A designed inhibitor of p53 aggregation rescues p53 tumor suppression in ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shalapour S, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer: an eternal fight between good and evil. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3347–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI80007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terzic J, Grivennikov S, Karin E, Karin M. Inflammation and colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2101–14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oeckinghaus A, Ghosh S. The NF-κB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000034. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granata F, Frattini A, Loffredo S, Staiano RI, Petraroli A, Ribatti D, et al. Production of vascular endothelial growth factors from human lung macrophages induced by group IIA and group X secreted phospholipases A2. J Immunol. 2010;184:5232–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tjiu JW, Chen JS, Shun CT, Lin SJ, Liao YH, Chu CY, et al. Tumor-associated macrophage-induced invasion and angiogenesis of human basal cell carcinoma cells by cyclooxygenase-2 induction. J Investig Dermatol. 2009;129:1016–25. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pyonteck SM, Akkari L, Schuhmacher AJ, Bowman RL, Sevenich L, Quail DF, et al. CSF-1R inhibition alters macrophage polarization and blocks glioma progression. Nat Med. 2013;19:1264–72. doi: 10.1038/nm.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu Y, Knolhoff BL, Meyer MA, Nywening TM, West BL, Luo J, et al. CSF1/CSF1R blockade reprograms tumor-infiltrating macrophages and improves response to T cell checkpoint immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer models. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5057–69. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whibley C, Pharoah PD, Hollstein M. p53 polymorphisms: cancer implications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:95–107. doi: 10.1038/nrc2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abbas T, Sivaprasad U, Terai K, Amador V, Pagano M, Dutta A. PCNA-dependent regulation of p21 ubiquitylation and degradation via the CRL4Cdt2 ubiquitin ligase complex. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2496–506. doi: 10.1101/gad.1676108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bendjennat M, Boulaire J, Jascur T, Brickner H, Barbier V, Sarasin A, et al. UV irradiation triggers ubiquitin-dependent degradation ofp21(WAF1) to promote DNA repair. Cell. 2003;114:599–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stuart SA, Wang JY. Ionizing radiation induces ATM-independent degradation of p21Cip1 in transformed cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15061–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808810200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett ML, Bennett FC, Liddelow SA, Ajami B, Zamanian JL, Fernhoff NB, et al. New tools for studying microglia in the mouse and human CNS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E1738–46. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525528113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarella C, Ferrero D, Gallo E, Pagliardi GL, Ruscetti FW. Induction of differentiation of HL-60 cells by dimethyl sulfoxide: evidence for a stochastic model not linked to the cell division cycle. Cancer Res. 1982;42:445–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Padilla PI, Wada A, Yahiro K, Kimura M, Niidome T, Aoyagi H, et al. Morphologic differentiation of HL-60 cells is associated with appearance of RPTPbeta and induction of Helicobacter pylori VacA sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15200–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bossen C, Ingold K, Tardivel A, Bodmer JL, Gaide O, Hertig S, et al. Interactions of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and TNF receptor family members in the mouse and human. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13964–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang X, Asano M, O’Reilly A, Farquhar A, Yang Y, Amar S. p53 is an important regulator of CCL2 gene expression. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:929–43. doi: 10.2174/156652412802480844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooks T, Pateras IS, Tarcic O, Solomon H, Schetter AJ, Wilder S, et al. Mutant p53 prolongs NF-kappaB activation and promotes chronic inflammation and inflammation-associated colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:634–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eruslanov EB, Bhojnagarwala PS, Quatromoni JG, Stephen TL, Ranganathan A, Deshpande C, et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils stimulate T cell responses in early-stage human lung cancer. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:5466–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI77053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartwig T, Montinaro A, von Karstedt S, Sevko A, Surinova S, Chakravarthy A, et al. The TRAIL-induced cancer secretome promotes a tumor-supportive immune microenvironment via CCR2. Mol Cell. 2017;65:730–42.e735. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Chen JX, Liu JP, You C, Liu YH, Mao Q. Gain of function of mutant TP53 in glioblastoma: prognosis and response to temozolomide. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1337–44. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiraishi S, Tada K, Nakamura H, Makino K, Kochi M, Saya H, et al. Influence of p53 mutations on prognosis of patients with glioblastoma. Cancer. 2002;95:249–57. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pollack IF, Finkelstein SD, Woods J, Burnham J, Holmes EJ, Hamilton RL, et al. Expression of p53 and prognosis in children with malignant gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:420–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee SY. Temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma multiforme. Genes Dis. 2016;3:198–210. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kyritsis AP, Bondy ML, Hess KR, Cunningham JE, Zhu D, Amos CJ, et al. Prognostic significance of p53 immunoreactivity in patients with glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:1617–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin Y, Xiao W, Song T, Feng G, Dai Z. Expression and prognostic significance of p53 in glioma patients: a meta-analysis. Neurochem Res. 2016;41:1723–31. doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-1888-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arimappamagan A, Somasundaram K, Thennarasu K, Peddagangannagari S, Srinivasan H, Shailaja BC, et al. A fourteen gene GBM prognostic signature identifies association of immune response pathway and mesenchymal subtype with high risk group. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mostafa H, Pala A, Högel J, Hlavac M, Dietrich E, Westhoff MA, et al. Immune phenotypes predict survival in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9:77. doi: 10.1186/s13045-016-0272-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang PF, Song HW, Cai HQ, Kong LW, Yao K, Jiang T, et al. Preoperative inflammation markers and IDH mutation status predict glioblastoma patient survival. Oncotarget. 2017;8:50117–23. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Q, Hu B, Hu X, Kim H, Squatrito M, Scarpace L, et al. Tumor evolution of glioma-intrinsic gene expression subtypes associates with immunological changes in the microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:42–56 e46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Horssen R, ten Hagen TL, Eggermont AM. TNF-alpha in cancer treatment: molecular insights, antitumor effects, and clinical utility. Oncologist. 2006;11:397–408. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-4-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carro MS, Lim WK, Alvarez MJ, Bollo RJ, Zhao X, Snyder EY, et al. The transcriptional network for mesenchymal transformation of brain tumours. Nature. 2010;463:318–25. doi: 10.1038/nature08712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhat Krishna PL, Balasubramaniyan V, Vaillant B, Ezhilarasan R, Hummelink K, Hollingsworth F, et al. Mesenchymal differentiation mediated by NF-κB promotes radiation resistance in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:331–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim SH, Ezhilarasan R, Phillips E, Gallego-Perez D, Sparks A, Taylor D, et al. Serine/threonine kinase MLK4 determines mesenchymal identity in glioma stem cells in an NF-κB-dependent manner. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:201–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han J, Chu J, Keung Chan W, Zhang J, Wang Y, Cohen JB, et al. CAR-engineered NK cells targeting wild-type EGFR and EGFRvIII enhance killing of glioblastoma and patient-derived glioblastoma stem cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11483. doi: 10.1038/srep11483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J, Sarkar S, Cua R, Zhou Y, Hader W, Yong VW. A dialog between glioma and microglia that promotes tumor invasiveness through the CCL2/CCR2/interleukin-6 axis. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:312–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roca H, Varsos ZS, Sud S, Craig MJ, Ying C, Pienta KJ. CCL2 and interleukin-6 promote survival of human CD11b+peripheral blood mononuclear cells and induce M2-type macrophage polarization. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34342–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang AL, Miska J, Wainwright DA, Dey M, Rivetta CV, Yu D, et al. CCL2 produced by the glioma microenvironment is essential for the recruitment of regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2016;76:5671. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bachoo RM, Maher EA, Ligon KL, Sharpless NE, Chan SS, You MJ, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor and Ink4a/Arf: convergent mechanisms governing terminal differentiation and transformation along the neural stem cell to astrocyte axis. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:269–77. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bowman RL, Wang Q, Carro A, Verhaak RGW, Squatrito M. GlioVis data portal for visualization and analysis of brain tumor expression datasets. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:139–41. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sturn A, Quakenbush J, Trajanoski Z. Genesis: cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:207–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.