Abstract

Background

Radical hysterectomy is one of the standard treatments for stage Ia2 to IIa cervical cancer. Bladder dysfunction caused by disruption of the pelvic autonomic nerves is a common complication following standard radical hysterectomy and can affect quality of life significantly. Nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy is a modified radical hysterectomy, developed to permit resection of oncologically relevant tissues surrounding the cervical lesion, while preserving the pelvic autonomic nerves.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy in women with stage Ia2 to IIa cervical cancer.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 4), MEDLINE via Ovid (1946 to May week 2, 2018), and Embase via Ovid (1980 to 2018, week 21). We also checked registers of clinical trials, grey literature, reports of conferences, citation lists of included studies, and key textbooks for potentially relevant studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the efficacy and safety of nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy compared to standard radical hysterectomy for women with early stage cervical cancer (stage Ia2 to IIa).

Data collection and analysis

We applied standard Cochrane methodology for data collection and analysis. Two review authors independently selected potentially relevant RCTs, extracted data, evaluated risk of bias of the included studies, compared results and resolved disagreements by discussion or consultation with a third review author, and assessed the certainty of evidence.

Main results

We identified 1332 records as a result of the search (excluding duplicates). Of the 26 studies that potentially met the review criteria, we included four studies involving 205 women; most of the trials had unclear risks of bias. We identified one ongoing trial.

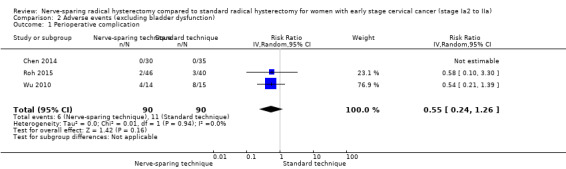

The analysis of overall survival was not feasible, as there were no deaths reported among women allocated to standard radical hysterectomy. However, there were two deaths in among women allocated to the nerve‐sparing technique. None of the included studies reported rates of intermittent self‐catheterisation over one month following surgery. We could not analyse the relative effect of the two surgical techniques on quality of life due to inconsistent data reported. Nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy reduced postoperative bladder dysfunctions in terms of a shorter time to postvoid residual volume of urine ≤ 50 mL (mean difference (MD) ‐13.21 days; 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐24.02 to ‐2.41; 111 women; 2 studies; low‐certainty evidence) and lower volume of postvoid residual urine measured one month following operation (MD ‐9.59 days; 95% CI ‐16.28 to ‐2.90; 58 women; 2 study; low‐certainty evidence). There were no clear differences in terms of perioperative complications (RR 0.55; 95% CI 0.24 to 1.26; 180 women; 3 studies; low‐certainty evidence) and disease‐free survival (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.00 to 106.95; 86 women; one study; very low‐certainty evidence) between the comparison groups.

Authors' conclusions

Nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy may lessen the risk of postoperative bladder dysfunction compared to the standard technique, but the certainty of this evidence is low. The very low‐certainty evidence for disease‐free survival and lack of information for overall survival indicate that the oncological safety of nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy for women with early stage cervical cancer remains unclear. Further large, high‐quality RCTs are required to determine, if clinically meaningful differences of survival exist between these two surgical treatments.

Plain language summary

Nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy for early stage cervical cancer

The issue Radical hysterectomy is one of the standard treatments for early stage cervical cancer. In this operation, the uterus (womb), cervix, upper vagina and tissues surrounding the cervix and upper vagina are removed. Because of the extent of this operation, women may experience problems with urinating which impacts on quality of life.

The aim of the review Nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy is a modified radical hysterectomy technique developed to preserve pelvic nerves in order to prevent bladder dysfunction. However, there is the potential that the operation may reduce survival and increase the chance of cancer recurring. We searched the scientific databases for articles published to May 2018 and included the studies in which women were randomly allocated to either standard operation or nerve‐sparing operation.

What are the main findings? We found four small studies that compared nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy versus standard radical hysterectomy. None of the included studies reported data on overall survival and rate of intermittent self‐catheterisation (procedure in which patient periodically inserts a small tube (catheter) through the urethra into the bladder to empty it of urine) over one month following surgery. We could not assess the relative effect of these two operations on quality of life due to inconsistent data reported. Women undergoing nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy had better voiding (a technique of bladder training in which the woman is instructed to urinate according to pre‐determined schedules) functions following surgery than those undergoing standard radical hysterectomy. We found no evidence that women undergoing nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy were more likely to have adverse consequences of surgery or relapse of their cancer. The certainty of the evidence is therefore low or very low.

What are the conclusions? Nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy may reduce the chance of bladder dysfunction compared to standard radical hysterectomy. However, the certainty of this evidence is low and further studies have the potential to better inform this outcome. We are very uncertain as to whether nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy is safe in terms of cancer survival outcomes. The evidence of cancer recurrence was of very low‐certainty, there were no long term data available regarding risk of death from cancer or other causes. High‐quality international studies involving many women would be needed to tell us whether nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy is beneficial in terms of survival for women with early stage cervical cancer, since risk of recurrence in this group are low.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy compared to standard radical hysterectomy for women with early stage cervical cancer (stage Ia2 to IIa) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women with stage Ia2 to IIa cervical cancer Settings: University/Tertiary Hospitals Intervention: nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection Comparison: standard radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard RH | Nerve‐sparing RH | |||||

| Overall survival | see comment | see comment | (0 studies) | Survival was reported in two studies. No deaths were reported in the standard group and only two deaths in the nerve‐sparing group were reported so we could not calculate the HR (Table 2). | ||

| Rate of ISC one month after operation | see comment | see comment | (0 studies) | No information reported in any of the included studies (see Effects of interventions). | ||

|

Time to PVR ≤ 50 mL (days) |

Mean 17.38 |

MD 13.21 lower (24.02 lower to 2.41 lower) |

MD ‐13.21 (‐24.02 to ‐2.41) | 111 women (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | |

| PVR one month after operation (mL) | Mean 80.25 |

MD 45.25 lower (59.81 lower to 30.69 lower) |

MD ‐45.25 (‐59.81 to ‐30.69) | 86 women (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | |

| Perioperative complications (excluding bladder dysfunction) | 122 per 1000 |

55 fewer per 1000 (from 32 more to 93 fewer) |

RR 0.55 (0.24 to 1.26) |

180 women (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | |

|

Disease‐free survival (median follow‐up: 101 months; range 13 to 137 months) |

50 per 1000 |

19 fewer per 1000 (50 fewer to 5,298 more) |

HR 0.63 (0.00 to 106.95) |

86 women (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low2 | Survival was reported in two studies. In one study, however there had been only one case with cancer recurrence so this precluded analysis of HR (Table 2). |

| Quality of life | see comment | see comment | (0 studies) | One study reported quality of life but there had been inconsistency between the statement of the authors and reported data. So, we did not perform any analyses for this outcome (see Effects of interventions). | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

RH: radical hysterectomy; ISC: Intermittent self‐catheterisation; PVR: Postvoid residual volume of urine CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: Mean difference; HR: Hazard ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate‐certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low‐certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low‐certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Unclear risk of selection/detection/performance biases and small sample size/non‐normally distributed data (‐2)

2Unclear risk of selection/detection/performance biases, small number of sample size and reported events, and applying unadjusted HRs in the analyses (‐3)

Background

Description of the condition

Cervical cancer remains a major health burden, with an age‐standardised incidence rate (ASR) of 14.0 per 100,000 person‐years (Ferlay 2015). In 2012, there were an estimated 528,000 new cases worldwide (Ferlay 2015). Approximately 85% of the global burden and nine out of 10 (87%) cervical cancer deaths occur in low‐ and/or middle‐income countries (Ferlay 2015). This high rate of cervical cancer‐related death in these countries is mainly due to deficiencies in surveillance systems (Parkin 2014). Treatment for cervical cancer depends on the clinical stage of the disease. Staging of cervical cancer (processes carried out to find out how far the cancer has spread) is based on clinical findings obtained from physical examination and diagnostic tests, which are used to assess the size of cervical mass, invasion into the tissues surrounding the cervix, and the spread to lymph nodes or distant organs (FIGO Committee 2014). The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system for cervical cancer is provided in Appendix 1 (FIGO Committee 2014).

A radical hysterectomy (also known as a Wertheim's hysterectomy) is performed to remove the uterus (womb), cervix, upper vagina and the parametria (tissues surrounding the cervix and upper vagina) (Marin 2014; Verleye 2009). Radical hysterectomy, in conjunction with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy (the surgical removal of the lymph nodes found in the pelvis), is the standard surgical treatment for FIGO stage Ia2–IIa cervical cancer, when preservation of fertility is not required or advisable (Verleye 2009), although more limited treatment, such as cone biopsy (removal of a cone shaped piece of tissue from the cervix) or simple hysterectomy, with lymph node dissection, is increasingly considered for small volume disease. Concurrent chemoradiation (combination of drug and radiotherapy given at the same time) is also acknowledged as a standard treatment option for women with early stage cervical cancer (Vale 2010). Decision‐making is based on individual patient characteristics and preferences, as well as weighing up the surgical risks with the longer‐term risks of chemoradiation.

Radical hysterectomy can be performed via laparotomy (open surgery), laparoscopic or robotic techniques (types of less invasive surgery). At present, there are three standard classification systems for radical hysterectomy (Marin 2014; Verleye 2009), including the Piver‐Rutledge‐Smith classification (Piver 1974), Querleu and Morrow classification (Querleu 2008), and the Gynecological Cancer Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (GCG‐EORTC) classification (Mota 2008) (See Appendix 2). See Cibula 2011; Marin 2014 and Querleu 2008 for detailed diagrams and figures demonstrating the differences in the types of hysterectomy.

Five‐year survival rates of women undergoing radical hysterectomy for stage Ia2 to IIa cervical cancer are over 80% (Hongladaromp 2014; Kim 2000; Mahawerawat 2013; Srisomboon 2011; Suprasert 2010). The procedure can, however, result in significant long‐term complications (Laterza 2015; Manchana 2009; Suprasert 2010). Bladder dysfunction (problems with urinating), caused by the disruption of the pelvic autonomic nerves during resections of parametria and paracolpium (the tissues surrounding the vagina), can be a major, distressing complication and may occur in up to 70% of women following radical hysterectomy (Laterza 2015; Plotti 2011; Suprasert 2010). Early postoperative bladder dysfunction includes a significant reduction of maximal urethral closure pressure (MUCP), increased volume of postvoid residual urine (PVR), detrusor muscle under activity and diminished bladder sensation, which, in some cases, may require prolonged urethral catheterisation. Late postoperative bladder dysfunction involves a persistent reduction of MUCP, voiding with abdominal straining, high volume of PVR, detrusor muscle over‐activity, and stress urinary incontinence (loss of urine caused by physical stress, e.g. sneezing or jumping) with estimates ranging from 8% to 47% (Katepratoom 2014; Laterza 2015).

Description of the intervention

The uterus, upper vagina, bladder and rectum receive innervation from both the sympathetic and parasympathetic supplies of the autonomic nervous system (a control system that acts largely unconsciously and regulates bodily functions). These nerves control smooth muscle function and pain sensation in viscera (internal organs). The sympathetic supply arises from the eleventh thoracic vertebra (T11) to the second lumbar vertebra (L2) nerve roots, which form a branching network called the superior hypogastric plexus (also referred to as the presacral nerve). The superior hypogastric plexus enters the pelvis, dividing into right and left hypogastric nerves. The pelvic splanchnic nerve is formed from parasympathetic fibres from S2‐S4 nerve roots. The pelvic splanchnic nerve merges with the hypogastric nerve to form left and right inferior hypogastric plexuses, which travel via the uterosacral ligaments (tissues that connect between the posterior‐lower part of the uterus to the anterior aspect of the sacrum) where they branch to supply the uterus and bladder (Fujii 2007; Huber 2015).

In terms of urinary function, the sympathetic nervous system relaxes the bladder muscle (detrusor muscle) to increase bladder capacity and constricts the internal urethral sphincter to inhibit the micturition (bladder voiding) reflex. The parasympathetic nervous system stimulates a series of contractions of the bladder muscle and relaxes the internal urethral sphincter (muscle that acts as a valve to control the exit of urine from the bladder), resulting in voluntary urination (Laterza 2015).

Nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy is a modified radical hysterectomy, developed to permit surgical removal (resection) of oncologically relevant tissues surrounding the cervical lesion, while preserving pelvic autonomic nerves (Charoenkwan 2010; Fujii 2008; Kato 2003). During nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy, parametrial dissection is carried out under directed visualisation of the adjacent pelvic autonomic nerves. Fibres of the hypogastric nerve can be identified in the mesoureter (tissues surrounding the ureter), approximately 2 cm to 3 cm beneath the ureter (tubes that carry urine from kidneys to the bladder). To minimise the risk of accidental transection (severing), the hypogastric nerve is partly dissected away from the level of resection of the posterior parametrium. During resection of the lateral parametrium, the inferior hypogastric plexus is directly visualised, partly dissected and separated to avoid disruption during resection. The vesical branch of inferior hypogastric plexus can be identified by following the course of the inferior hypogastric plexus from the uterosacral ligaments and is separated from the blood vessels of the tissue surrounding the vagina during resection of the anterior parametrium (Charoenkwan 2006; Charoenkwan 2010; Fujii 2007; Fujii 2008).

Previous studies proposed that nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy may be feasible without compromising the extent of resection and the rate of cancer recurrence when compared to the standard techniques of radical hysterectomy (Charoenkwan 2006; Kim 2015a; Xue 2016). A factor predicting the likelihood of the success of nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy is the FIGO stage of the disease. Women with stage Ib1 cervical cancer are more likely to have successful preservation of autonomic nerves during laparoscopic nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy than those with a higher stage of disease (stage Ib2 to IIa) (Kim 2015a).

How the intervention might work

The extent of potential injury to pelvic autonomic nerves is associated with the extent of the operation (Butler‐Manuel 2000; Ercoli 2003). The surgical steps of radical hysterectomy that potentially damage the pelvic autonomic nerves are the resection of parametrial tissues, particularly posterior and anterior parametria (Ercoli 2003). Previous quantitative immunocytochemistry studies (postoperative examination of tissue removed during surgery using antibodies to highlight nerve fibres when viewed under a microscope) indicated that the presence of nerve trunks (the main stem of a nerve), autonomic ganglia (nerve connection hubs), and free nerve fibres within the parametrial tissues, which were transected during conventional radical hysterectomy (Butler‐Manuel 2000; Ercoli 2003; Maas 2005; Mantzaris 2008). In addition, when a more careful approach is used during resection of the parametria, through identification and isolation of the adjacent pelvic autonomic nerves, significantly fewer autonomic nerves are disrupted iatrogenically (inadvertently) during nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy than in conventional radical hysterectomy (Maas 2005; Mantzaris 2008). This results in a substantial reduction in nerve disruption and may lower the risk of developing bladder dysfunction after radical hysterectomy (Charoenkwan 2010; Fujii 2007; Tseng 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

Although the survival outcomes of women undergoing standard radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy for stage Ia2 to IIa cervical cancer are generally good, bladder dysfunction following standard radical hysterectomy can affect quality of life significantly (Ceccaroni 2012; Wu 2010. Nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy may offer improved quality of life. However, there is the potential that a nerve‐sparing approach may compromise oncological outcomes and increase the risk of disease recurrence. We aimed to assess the benefits and harms of this approach in order to inform women and their surgeons about whether a more refined surgical approach is warranted, or whether a more traditional radical resection is to be recommended.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy in women with stage Ia2 to IIa cervical cancer.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Women aged 18 years or older undergoing radical hysterectomy (Piver class III, Querleu and Morrow type C, or European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (GCG‐EORTC) type III) for stage Ia2 to IIa cervical cancer. Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 display the details of the FIGO staging classification of cervical cancer, and the classifications of radical hysterectomy, respectively. If studies include other stages of cervical cancer, we planned to contact trial authors to retrieve data related to the women with stage Ia2 to IIa cervical cancer only.

Types of interventions

Randomised controlled trials comparing nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy versus standard radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer stage Ia2 to IIa irrespective of the types of surgical approach (i.e. laparotomy, laparoscopy or other minimally invasive surgery). See Description of the intervention for details of the differences between nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy and standard radical hysterectomy.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Overall survival: survival until death from all causes. Survival assessed from the time when women were enrolled in the study.

Rate of intermittent self‐catheterisation (ISC) at one month after the operation.

Quality of life: assessed using a scale that has been validated through reporting of norms in a peer‐reviewed publication, i.e. EORTC QLQ‐CX24 cervical cancer‐specific quality of life questionnaire (Greimel 2006).

Secondary outcomes

Time to postvoid residual volume of urine ≤ 50 mL after operation (days) (amounts of urine measured by clean intermittent catheterisation after the patient feels as though bladder is empty).

Postvoid residual urine volume (PVR) of urine at one month, three months, six months, and 12 months after operation (mL).

Adverse events (excluding bladder dysfunction): we planned to categorise the severity of the following adverse events according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE 2010): febrile morbidity; surgical site infections; genitourinary complications (e.g. fistula, hydronephrosis, vaginal stenosis); gastrointestinal complications (e.g. fistula, constipation); lymphovascular complications (e.g. lymphocyst, lymphoedema, thrombosis, embolism); direct surgical morbidity (e.g. injury to bladder, ureter, small bowel or colon); reoperation (an operation to correct a condition not corrected by a previous operation or to correct the complications of a previous operation); readmission (a hospitalisation that occurs within 30 days after discharge from hospital); blood component transfusion (the transfer of blood or blood components from one person (the donor) into the bloodstream of another person (the recipient).

Subjective urinary symptoms: using a standard questionnaire, i.e. International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) (Barry 1992)

Disease‐free survival (DFS): survival until the appearance of a new lesion of disease. Survival will be assessed from the time when women are enrolled in the study.

Rate of cancer recurrence: we will classify recurrences as loco‐regional or distant.

Rate of urinary tract infection during the month after operation diagnosed by cultivation of urine.

Maximal urethral closure pressure (MUCP) from urodynamic measurements (cmH2O).

Maximum flow rate (mL per second) and number of women with low maximum flow rate (< 15 mL per second) obtained urodynamic measures.

Detrusor pressure at maximum flow and number of women with low detrusor pressure at maximum flow (< 25 cmH2O).

Sexual dysfunction: using a validated scale, i.e. Sexual function‐Vaginal change Questionnaire (SVQ) (Jensen 2004).

Cost‐effectiveness: using a validated scale, i.e. European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO‐MCBS) (Cherny 2015).

Operative time (minutes).

Estimated blood loss (mL).

See Table 1 which reports the following outcomes listed in order of priority.

Overall survival

Rate of ISC one month after operation;

Time to postvoid residual volume of urine ≤ 50 mL after operation;

Postvoid residual volume of urine one month after operation;

Rate of adverse event excluding bladder dysfunction;

Disease‐free survival (DFS); and

Quality of life.

Search methods for identification of studies

We included RCTs, irrespective of the language of publication, publication status or sample size.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 4), in the Cochrane Library;

MEDLINE via Ovid (1946 to May week 2, 2018);

Embase via Ovid (1980 to 1980 to 2018, week 21).

Appendix 3, Appendix 4, and Appendix 5 display the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Embase. All relevant articles were identified on PubMed and we made a further search for newly published articles using the 'related articles’ feature.

Searching other resources

Ongoing trials and grey literature

We searched the World Health Organization's International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/en) and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify any ongoing trials. Had we identified ongoing trials that had not been published, we planned to approach the principal investigators and major co‐operative groups active in this area, to ask for relevant data. We searched the following databases for grey literature: Open Grey (www.opengrey.eu) and Index to Theses (ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: UK & Ireland).

Handsearching

We handsearched the citation lists of included studies, key textbooks and previous systematic reviews. We planned to contact experts in the field to identify further reports of trials. We also handsearched the reports of conferences from the following sources (from the year when electronic conference proceedings became available to current):

Annual Meeting of the American Society of Gynecologic Oncology;

Annual Meeting of the European Society of Medical Oncology;

Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology;

Annual Meeting of the British Gynaecological Cancer Society;

Biennial Meeting of the Asian Society of Gynecologic Oncology;

Biennial Meeting of the Asia and Oceania Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology;

Biennial Meeting of the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology; and

Biennial Meeting of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to a reference management database (EndNote). After duplicates were removed, we transferred these data to Covidence (www.covidence.org). We excluded those studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria and we obtained copies of the full text of potentially relevant references. Independently, two review authors (CK and AA) assessed the eligibility of the retrieved reports/publications. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person (KG or PL). We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study. We used the details regarding the selection process in Covidence to complete a PRISMA flow diagram and 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (CK and AA) independently extracted study characteristics and outcome data from included studies. We noted when outcome data were not reported in a usable way in the Characteristics of included studies table. We intended to resolve disagreements by consensus or by involving a third person (KG or PL).

For included studies, we extracted the following data.

Author, year of publication and journal citation (including language)

Country

Setting

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study design and methodology

-

Study population and disease characteristics

Total number enrolled

Participant characteristics

Age

Co‐morbidities

Other baseline characteristics

Surgical technique (laparotomy, laparoscopy or robotic‐assisted procedure)

Estimated blood loss (mL)

Stage of cervical cancer

Histopathological subtype of cervical cancer

Tumour size (largest tumour diameter)

Lymphadenectomy details including technique (sampling versus complete dissection) and status of lymph nodes (negative or positive for metastasis)

Radicality of the operation

Operative time (minutes)

Postoperative adjuvant treatment received and indication

-

Intervention details

Nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy

-

Comparison

Conventional radical hysterectomy

Risk of bias in study (see below)

Duration of follow‐up

Outcomes: for each outcome, we extracted the outcome definition and unit of measurement (if relevant). For adjusted estimates, we recorded variables adjusted for in analyses.

Results: we extracted the number of participants allocated to each intervention group, the total number analysed for each outcome and the missing participants.

Notes: funding for trial and notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

We extracted results as follows.

For time‐to‐event data (survival outcomes and time to postvoid residual urine (PVR)≤ 50 mL after operation), we extracted the log of the hazard ratio (log(HR)) and its standard error from trial reports. If these were not reported, we estimated the log (HR) and its standard error using the methods of Parmar 1998.

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. adverse events and urinary tract infection), we extracted the number of women in each treatment arm who experienced the outcome of interest and the number of women assessed at endpoint, in order to estimate a risk ratio (RR).

For continuous outcomes (e.g. time to PVR ≤ 50 mL after operation, volume of PVR and quality of life measures), we extracted the final value and standard deviation (SD) of the outcome and the number of women assessed at endpoint in each treatment arm at the end of follow‐up, in order to estimate the mean difference (MD) between treatment arms (if trials measured outcomes on the same scale) or standardised mean difference (SMF) (if trials measured outcomes on different scales) between treatment arms and its standard error. If continuous outcomes were expressed as median and range, we contacted the study author to obtain sample mean and SD. If this was not possible, we converted these data using the formula, as suggested by Wan 2014.

Where possible, we intended to extract data according to an intention‐to‐treat analysis, in which participants are analysed in the groups to which they were assigned.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed and reported on the methodological quality and risk of bias of included studies in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), which recommends the explicit reporting of the following individual issues for RCTs.

Selection bias: random sequence generation and allocation concealment

Performance bias: blinding of participants and personnel (outcome assessors)

Detection bias: blinding of outcome assessment

Attrition bias: incomplete outcome data (i.e. incomplete follow‐up outcomes and treatment‐related complications)

Reporting bias: selective reporting of outcomes

Other potential bias

Two review authors (CK and AA) applied the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool independently and resolved differences by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (KG or PL). We judged each item as being at high, low or unclear risk of bias as set out in the criteria displayed in Appendix 6 (Higgins 2011). We provided a quote from the study report or a statement (or both) as justification for the judgement for each item in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarised the results in both a 'Risk of bias' graph and a 'Risk of bias' summary. When interpreting treatment effects and meta‐analyses, we took into account the risk of bias for the studies that contributed to that outcome. Where information on risk of bias relates to unpublished data, or correspondence with trial authors, we recorded this in the table.

Measures of treatment effect

We used the following measures of the effect of treatment.

For time‐to‐event outcomes (DFS), we analysed data using hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

For dichotomous outcomes (adverse events, cancer recurrence) we analysed data on the basis of the number of events and number of people assessed in the intervention and comparison groups. We used these to calculate the RR and 95% CI.

For continuous outcomes (volume of PVR, subjective urinary, MUCP, flow rate, detrusor pressure, operative time, and estimated blood loss), we analysed data based on the mean, standard deviation (SD) and number of people assessed for both the intervention and comparison groups to calculate the MD between treatment arms with a 95% CI. If the MD was reported without individual group data, we intended to use this to report the study results. If more than one study measured the same outcome using different tools, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI using the inverse variance method.

Unit of analysis issues

The units of analysis are the participants receiving interventions of interest. A study with multiple intervention groups is not applicable for this review, as we compared the two interventions, namely nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy versus standard radical hysterectomy.

Dealing with missing data

We did not impute missing outcome data for any of the outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plots. Also, we assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the I² statistic and Chi² test (Deeks 2001; Higgins 2011). We performed subgroup analysis to investigate the potential heterogeneity of the included studies, if feasible. If there was evidence of substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity across the included studies, we applied a narrative review approach to data synthesis.

Assessment of reporting biases

We were unable to assess reporting bias, as only four studies met our inclusion criteria.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using Cochrane Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2014). We applied the random‐effects model with inverse variance weighting for all meta‐analyses (DeSimonian 1986).

For time‐to‐event data, we calculated pooled HRs using the generic inverse variance method.

For any dichotomous outcomes, we computed the RR for each study and then pooled these.

For continuous outcomes, we pooled the MD between the treatment arms, if all trials measured the outcome on the same scale; otherwise we pooled SMDs.

Main outcomes of 'Summary of findings' table for assessing the certainty of the evidence

We have prepared a Table 1 to summarise the results of the meta‐analysis based on the methods described in Chapter 11 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011).

We presented the results of meta‐analyses and overall certainty of the evidence for seven main outcomes as outlined in Types of outcome measures according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, which take into account issues not only related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias), but also to external validity such as directness of results (Langendam 2013). We created a 'Summary of findings' table using GRADEpro GDT (www.gradepro.org). We downgraded the evidence from high certainty by one level for each serious limitation, or by two levels for any very serious limitation. The GRADE levels of evidence can be interpreted as shown below.

High certainty: the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate certainty: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low certainty: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low certainty: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As only four studies assessing 205 women, met our inclusion criteria, subgroup analyses according to stage of the disease (Ia2‐Ib1 versus Ib2 or higher stages), and degree of lymph node dissection (pelvic versus pelvic and para‐aortic) as mentioned in the review protocol were not feasible. However, we considered factors in the interpretation of review findings. In future updates, we will perform subgroup analysis according to these factors, if feasible.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed no sensitivity analyses, as all data were obtained from published RCTs that contained only women with cervical cancer stage Ia2 to IIa and all included RCTs were at unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment. In future updates, if statistical heterogeneity is detected and there is a sufficient number of included studies, we will perform sensitivity analyses to determine the possible contribution of other clinical or methodological differences between the trials, specifically:

repeating the analysis excluding any unpublished studies:

repeating the analysis excluding RCTs judged to be at high or unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment;

repeating the analysis excluding RCTs that contained women with cervical cancer other than stage Ia2 to IIa.

Results

Description of studies

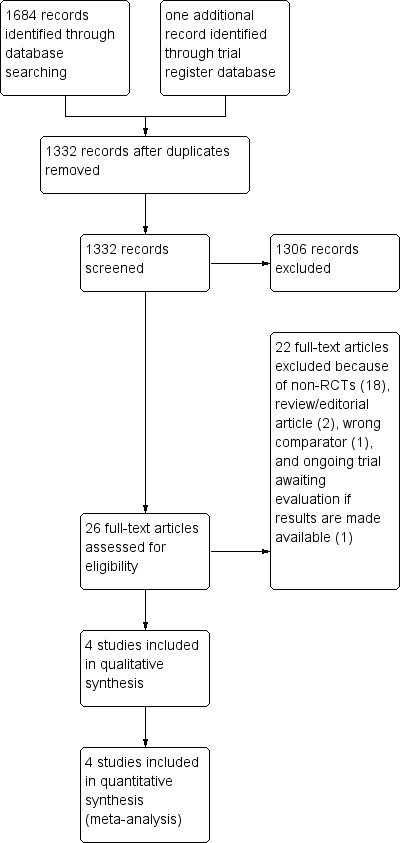

See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow of study selection.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Results of the search

We ran a broad search in May 2018, MEDLINE search retrieved 711 studies. Searches of Embase and CENTRAL identified 921 studies and 52 studies, respectively. Searching trial register databases identified one ongoing study. After de‐duplication, we screened titles and abstracts of 1332 references and excluded 1306 that obviously did not meet the review inclusion criteria. Of the 26 studies that potentially met our inclusion criteria, we excluded 21 references after reviewing the full‐text and added on reference to Ongoing studies, leaving four studies assessing a total of 205 for quantitative synthesis. Searches of the grey literature, conference proceedings, and citation lists of included studies revealed no potentially eligible studies.

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies

Participants

Chen 2012 recruited 25 women with FIGO stage Ib1 to IIa cervical cancer (nine women with Ib1 stage disease; six with Ib2; 10 with IIa) who received neither neoadjuvant treatment and had no clinical bladder dysfunction. Thirteen participants (four women with Ib1stage disease; four with Ib2, and five with IIa) and 12 participants (five women with Ib1 stage disease; two with Ib2; five with IIa) were randomly assigned to undergo open nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy and standard open radical hysterectomy, respectively.

Chen 2014 randomised 65 women with FIGO stage Ia2 to IIa cervical cancer (five women with Ia2 stage disease; 20 with Ib1; 10 with Ib2; 25 with IIa; and five with missing data on stage of cancer) to undergo laparoscopic nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy (N = 30) or standard laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (N = 35).

Roh 2015 randomised 92 women with FIGO stage Ib1 to IIa cervical cancer to undergo nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy (N = 48) or standard radical hysterectomy (N = 44). However, only participants with a follow‐up duration of more than one year after surgery were included in the final analyses (40 in open standard radical hysterectomy and 46 in open nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy). None of the participants had clinical urinary dysfunction before the operation.

Wu 2010 recruited 31 women with FIGO stage Ib1 to IIa cervical cancer who had no abnormal bladder function before the operation confirmed by urodynamic study. However, only 29 participants completed the study and were included in the analysis. Fifteen participants (12 women with Ib1 stage disease; two with Ib2; and one with IIa), and 14 participants (10 women with Ib1stage disease and four with IIa) were randomly assigned to undergo open nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy and open standard radical hysterectomy, respectively.

Interventions

The intervention in Chen 2012; Roh 2015; and Wu 2010 was class III (PIVER III) nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy. The comparator was standard class III radical hysterectomy with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy. All operations in Chen 2012; Roh 2015; and Wu 2010 were performed via laparotomy (Chen 2012; Roh 2015; Wu 2010). In Chen 2014, operations were conducted via laparoscopy.

Outcomes reported

Chen 2012 reported the amount of removed nerve bundles and vessels, operative time, blood loss, and postoperative bladder and bowel functions including time to postvoid residual urinary volume (PVR) ≤ 50 mL, time to first flatus and defecation, and status at last follow‐up.

Chen 2014 reported blood loss, operative time, perioperative complications, bladder functions (duration of the postoperative catheterisation, maximum flow rate (MFR), maximum detrusor pressure (MDP)) assessed by urodynamic study performed at six to 12 months, intestinal functions, urinary symptoms, and quality of sexual life. The authors evaluated intestinal functions, urinary symptoms, and quality of sexual life 12 months following the operation. However, the authors did not report the number of participants assessed for bladder function assessment and quality of sexual life. We contacted the authors via their published contact details to ask for additional information, but none have been forthcoming.

Roh 2015 reported bladder function recovery including time to PVR < 50 mlLand bladder function (PVR, maximal urethral closure pressure (MUCP), MFR, average flow rate (AFR), bladder compliance, and detrusor pressure at maximum flow) assessed by urodynamic study performed one, three and 12 months following the operation; and subjective urinary symptoms using International Prostate Symptom Score (IPPS); disease‐free survival (DFS); and overall survival.

Wu 2010 reported postoperative complications, operative time, amount of blood loss, bladder function recovery including time to PVR < 100 mL and postoperative bladder function (PVR, MUCP, MFR, AFR, bladder compliance, and stress incontinence), and quality of life.

Excluded studies

After obtaining the full‐text articles, we excluded 21 references and added on reference to Ongoing studies for the following reasons.

Eighteen references were non‐RCTs in which results were compared between women who underwent nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy and those who did not (Barbic 2012; Bogani 2014; Ceccaroni 2012; Charoenkwan 2010; Cibula 2010; Ditto 2009; Hockel 2000; Kanao 2014; Kim 2017; Querleu 2002; Raspagliesi 2006; Raspagliesi 2017; Shi 2016; Skret‐Magierlo 2010; Su 2017; Todo 2006; Tseng 2012; Yang 2016).

One RCT compared type II versus type III hysterectomy for cervical cancer, which is not a comparator of interest in this review (Milani 1991).

One reference was a review article describing the surgical techniques for parametrial dissection during laparoscopic nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy (Ceccaroni 2010).

One reference was an editorial article (Sakuragi 2015).

One reference was an ongoing trial awaiting evaluation once the results are made available (Gaballa 2015).

For further details, see the Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Risk of bias in included studies

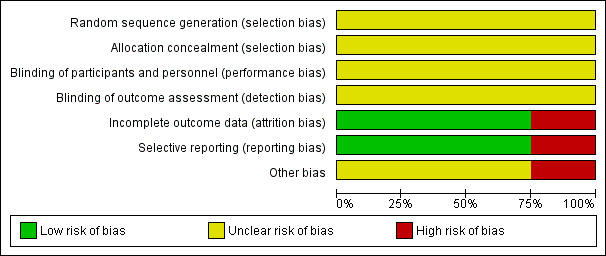

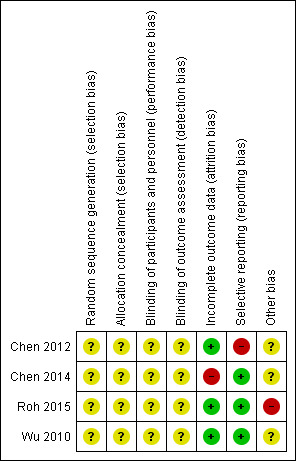

For further details on risk of bias in all included studies, see Characteristics of included studies table; Figure 2; and Figure 3.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

There was no statement regarding the method used to generate and conceal the allocation sequence in any of the included studies. We determined this to indicate unclear risk of selection bias (Figure 2; Figure 3).

Blinding

There was no detailed description regarding the blinding of participants and personnel in any of the included studies. Some outcomes, such as subjective bladder dysfunction, quality of sexual life, and quality of life, are likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. We, therefore, determined this domain to be at unclear risks of performance bias and detection bias (Figure 2; Figure 3).

Incomplete outcome data

Rates of incomplete outcome data in Chen 2012 and Roh 2015 were approximately 8% and 4%, respectively. In Wu 2010, all participants were analysed for all outcomes and there was no missing data. We, therefore, judged Chen 2012; Roh 2015; and Wu 2010 as having low risk of attrition bias. In Chen 2014, only 16 women (24.6%) in both groups had undergone the urodynamic study to evaluate postoperative bladder functions (7 or 23.3% in the nerve‐sparing group and 9 or 25.7% in the standard surgery group) which was one of the primary outcomes of interest in this study. We, therefore, judged Chen 2014 as having high risk of attrition bias (Figure 2; Figure 3).

Selective reporting

All potential relevant outcomes were reported in Chen 2014; Roh 2015; and Wu 2010, so we judged these studies as having low risk of reporting bias. The two‐year DFS reported in Chen 2012 was considered to be too short for determining survival outcome of women with early stage cervical cancer, indicating high risk of bias secondary to selective reporting (Figure 2; Figure 3).

Other potential sources of bias

In Roh 2015, the analyses were not based on an intention‐to‐treat basis, as they randomised 92 women, but included only women with an adequate follow‐up duration of more than one year after the surgery in the analyses (86 women; 40 in standard surgery and 46 in nerve‐sparing surgery). We therefore determined Roh 2015 as having high risk for this domain. Information in Chen 2012; Chen 2014; and Wu 2010 were insufficient for assessment of whether an important risk of bias existed (Figure 2; Figure 3).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Overall survival

Chen 2012, evaluated 25 women with median follow‐up of 34 months and found one patient, who underwent nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy, developed distant metastasis and died 11 months after operation. Roh 2015, assessing 86 women with a median follow‐up of 111 months in the nerve‐sparing group and 101 months in the standard surgery group, observed that one patient, who underwent nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy, died after developing liver and lung metastases. No women assigned to standard radical hysterectomy in either of the included studies died from any cause (Table 2). Thus, we could not calculate the hazard ratio of death from these two included studies. The remaining two included studies did not report data on overall survival (Chen 2014; Wu 2010).

1. Cancer recurrence.

| Study | Follow‐up time | Recurrence stratified by groups | Sites of recurrence | Death from any causes | |

| Nerve‐sparing RH | Standard RH | ||||

| Roh 2015 | Median follow‐up time of the entire cohort: 101 months (range, 13 to 137 months) | 3/46 (6.52%) | 2/40 (5.0%) | Lung (2) Lung and liver (1) Lung and pelvis (1) Para‐aortic node (1) |

one participant in nerve‐sparing group had lung and liver metastases |

| Chen 2012 | Median follow‐up time nerve‐sparing RH group: 33.5 months (range, 25 to 37 months); median follow‐up time in standard RH group: 34 months (range, 27 to 37 months) | 1/12 (8.3%) | 0/13 (0%) | Sigmoid colon (1) | one participant in nerve‐sparing group had colonic metastasis |

RH, radical hysterectomy

Intermittent self‐catheterisation (ISC) at one month after the operation

No information on ISC at one month after the operation was reported in any of the included studies. In Roh 2015, ISC had to be performed in three of the 40 women who were allocated to the standard radical hysterectomy group, but in none who allocated to the nerve‐sparing group (7.5% versus 0%, P < 0.001). However, there was no detailed description regarding the criteria for ISC in this study.

Quality of life

Wu 2010 reported health‐related quality of life evaluated one year after operation using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐ cervical cancer (FACT‐Cx). Higher values in this assessment represent better quality of life (Webster 2003). The authors of this study stated in the discussion section of their published article that the quality of life among women in the nerve‐sparing group was better than reported among women in the standard operation group. This statement, however, contradicts results reported, which noted that women assigned to nerve‐sparing surgery had lower scores than those reported in the standard surgery group (5.36 ± 2.47 versus 22.33 ± 8.38, respectively; Wu 2010). We contacted the author to ask about this inconsistency, but we have received no response. Thus, any analysis for this outcome was not performed.

Secondary outcomes

Time to postvoid residual volume of urine (PVR) ≤ 50 mL after operation

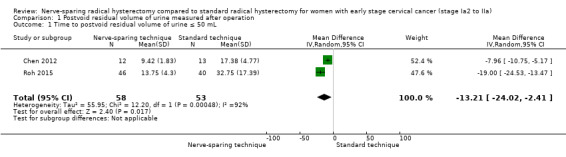

Meta‐analysis assessing 111 women (Chen 2012; Roh 2015) showed that women who had nerve‐sparing surgery had shorter time to PVR ≤ 50 mL than those given standard radical hysterectomy (mean difference (MD) ‐13.21 days; 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐24.02 to ‐2.41; Analysis 1.1). The percentage of variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than to chance may represent considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 92%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Postvoid residual volume of urine measured after operation, Outcome 1 Time to postvoid residual volume of urine ≤ 50 mL.

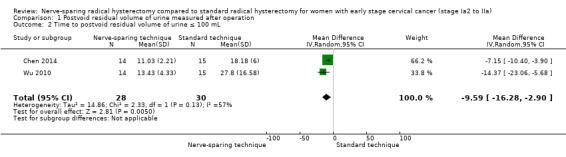

Time to postvoid residual volume of urine (PVR) ≤ 100 mL after operation

Meta‐analysis assessing 58 women (Chen 2014; Wu 2010) observed a shorter time to PVR ≤ 100 mL among women undergoing nerve‐sparing surgery compared to those who underwent standard radical hysterectomy (MD ‐9.59 days; 95%CI ‐16.28 to ‐2.90; Analysis 1.2) see Differences between protocol and review). The percentage of variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than to chance may represent moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 57%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Postvoid residual volume of urine measured after operation, Outcome 2 Time to postvoid residual volume of urine ≤ 100 mL.

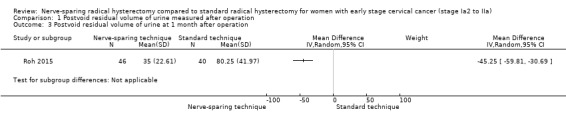

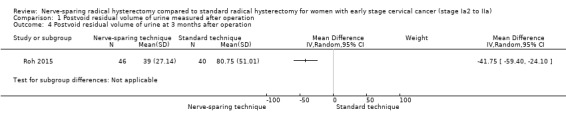

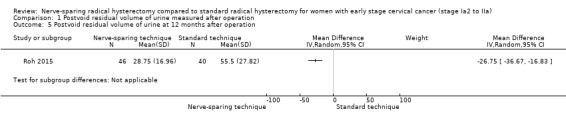

Postvoid residual volume of urine (PVR) one month, three months, six months, and 12 months after operation

Roh 2015 reported PVR at one month, three months, and 12 months in 86 women following radical hysterectomy. Women undergoing nerve‐sparing surgery had lower PVR as evaluated over these three time points than those who underwent standard radical hysterectomy (at one month; MD ‐45.25; 95% CI ‐59.81 to ‐30.69; at three months; MD ‐41.75; 95% CI ‐59.40 to ‐24.10; and at 12 months; MD ‐26.75; 95% CI ‐36.67 to ‐16.83; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.4: Analysis 1.5). No information on PVR at six months after operation was reported in any of the included studies.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Postvoid residual volume of urine measured after operation, Outcome 3 Postvoid residual volume of urine at 1 month after operation.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Postvoid residual volume of urine measured after operation, Outcome 4 Postvoid residual volume of urine at 3 months after operation.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Postvoid residual volume of urine measured after operation, Outcome 5 Postvoid residual volume of urine at 12 months after operation.

Adverse events (excluding bladder dysfunction)

Meta‐analysis assessing 180 women (Chen 2014; Roh 2015; Wu 2010) showed no differences in risk of perioperative complications between women who underwent nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy and those who underwent standard radical hysterectomy (risk ratio (RR) 0.55; 95% CI 0.24 to 1.26; Analysis 2.1). However, these studies did not report the severity of adverse event in details (see Differences between protocol and review). The percentage of variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than to chance was not important (I2 = 0%). Table 3 displays the types of perioperative complications reported in Chen 2014; Roh 2015; and Wu 2010. No information on perioperative complication was reported in Chen 2012.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse events (excluding bladder dysfunction), Outcome 1 Perioperative complication.

2. Perioperative complications.

| Study | Complications | Nerve‐sparing RH | Standard RH |

| Wu 2010 | Lymphocoele | 1/14 (7.1%) | 2/15 (13.3%) |

| Postoperative fever | 2/14 (14.3%) | 4/15 (26.7%) | |

| Poor incision healing | 1/14 (7.1%) | 2/15 (13.3%) | |

| Intestinal obstruction | 0/14 (0%) | 0/15 (0%) | |

| Urinary tract injury | 0/14 (0%) | 0/15 (0%) | |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0/14 (0%) | 0/15 (0%) | |

| Chen 2014 | Bladder injury | 0/30 (0%) | 0/35(0%) |

| Fistula/ureter injury | 0/30 (0%) | 0/35(0%) | |

| Gastrointestinal injury | 0/30 (0%) | 0/35(0%) | |

| Roh 2015 | Incisional hernia | 1/46 (2.2%) | 1/40 (2.5%) |

| Infected lymphocoele | 1/46 (2.2%) | 2/40 (5.0%) |

RH, radical hysterectomy; Data are present as number of event divided by number of women evaluated

Subjective urinary symptoms

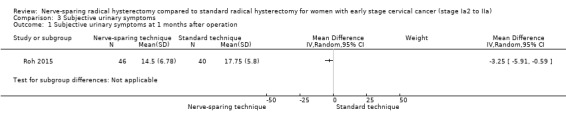

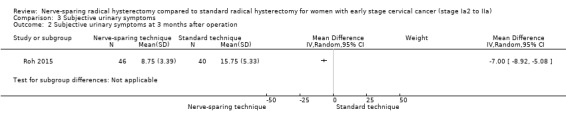

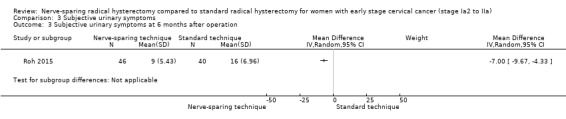

Roh 2015 reported subjective urinary symptoms among the two comparison groups using a standard self‐administered questionnaire of International Prostate Symptom Score (IPPS). Lower IPPS values represent better urinary function (Barry 1992). Women undergoing nerve‐sparing surgery had lower score evaluated at one months (MD ‐3.25; 95% CI ‐5.91 to ‐0.59), three months (MD ‐7.00; 95% CI ‐8.92 to ‐5.08), and 12 months (MD ‐7.00; 95% CI ‐9.67 to ‐4.33) than those who underwent standard radical hysterectomy (Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2 and Analysis 3.3).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subjective urinary symptoms, Outcome 1 Subjective urinary symptoms at 1 months after operation.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subjective urinary symptoms, Outcome 2 Subjective urinary symptoms at 3 months after operation.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subjective urinary symptoms, Outcome 3 Subjective urinary symptoms at 6 months after operation.

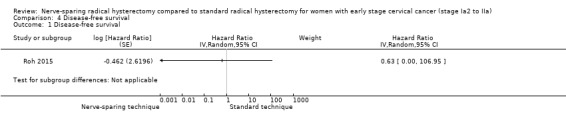

Disease‐free survival (DFS)

Roh 2015 assessed 86 women and found no difference in the risk of cancer recurrence between women undergoing nerve‐sparing surgery and those who underwent standard radical hysterectomy (hazard ratio (HR) 0.63; 95% CI 0.00 to 106.95); Analysis 4.1). We estimated HRs indirectly from the published data. However, HR in this study was not adjusted for important prognostic factors. In addition, a remarkably wide range of associated 95% CIs, which included the value of no difference, might preclude drawing a meaningful conclusion regarding this outcome. In Chen 2012, one patient in the nerve‐sparing group experienced disease recurrence nine months after operation, while none who were assigned to standard radical hysterectomy developed recurrence of disease. Thus, we cannot calculate the HR of freedom from cancer recurrence in this study. Wu 2010 and Chen 2014 did not report data on DFS.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Disease‐free survival, Outcome 1 Disease‐free survival.

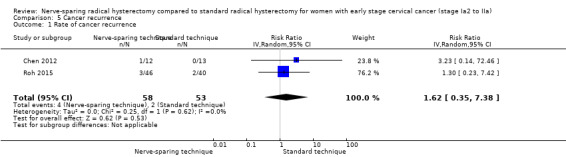

Cancer recurrence

The rate of cancer recurrence was reported in two of the four included studies (Chen 2012; Roh 2015). In Chen 2012, one patient in the nerve‐sparing group (one of 12 women) developed recurrence in the sigmoid colon, while none of the 13 women allocated to the standard surgery group had cancer recurrence (Table 2). In Roh 2015, approximately 6.5% of women assigned to the nerve‐sparing group experienced recurrent cervical cancer, which was comparable to the 5.0% reported for women undergoing standard radical hysterectomy (Table 2). When we pooled the data from these two included studies (Chen 2012; Roh 2015), no difference was demonstrated (111 women; RR 1.62; 95% CI 0.35 to 7.38; Analysis 5.1). The percentage of variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than to sampling error (chance) was not important (I2 = 0%).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Cancer recurrence, Outcome 1 Rate of cancer recurrence.

Urinary tract infection during the month after operation

No information on urinary tract infection over the month following surgery was reported in any of the included studies.

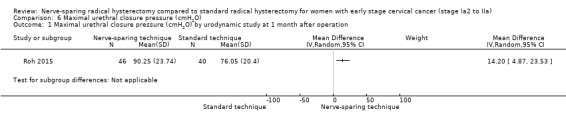

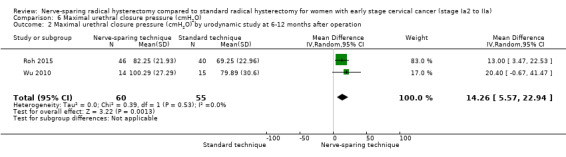

Maximal urethral closure pressure (MUCP)

High MUCP indicates good urinary bladder function (Laterza 2015). Roh 2015 reported that women undergoing nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy had higher MUCP assessed at one month after operation than women assigned to the standard surgery group (MD 14.20 cmH2O; 95 CI 4.87 to 23.53; Analysis 6.1). Meta‐analysis of 115 women obtained from Roh 2015 and Wu 2010 assessing MUCP six to 12 months after operation showed that the higher MUCP among women undergoing nerve‐sparing surgery persisted (MD 14.26 cmH2O ; 95% CI 5.57 to 22.94; Analysis 6.2).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Maximal urethral closure pressure (cmH2O), Outcome 1 Maximal urethral closure pressure (cmH2O) by urodynamic study at 1 month after operation.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Maximal urethral closure pressure (cmH2O), Outcome 2 Maximal urethral closure pressure (cmH2O) by urodynamic study at 6‐12 months after operation.

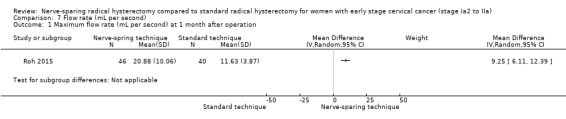

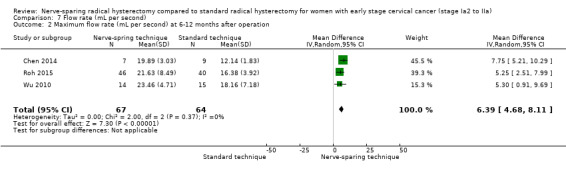

Maximum flow rate (MFR) and number of women with low MFR

High MFR represents good detrusor contractility (Laterza 2015). In Roh 2015, women undergoing nerve‐spring radical hysterectomy had higher MFR assessed at one month following operation than women allocated in the standard surgery group (MD 9.25 mL/sec; 95% CI 6.11 to 12.39; Analysis 7.1). Meta‐analysis of 131 women (Chen 2014; Roh 2015; Wu 2010) showed a persistent higher MFR assessed at six to 12 months after operation among women in the nerve‐sparing group than those who underwent standard operation (MD 6.39 mL/sec; 95% CI 4.68 to 8.11; Analysis 7.2). The percentage of variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than to chance was not important (I2= 0%). No information on the number of women with low MFR was reported in any of the included studies.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Flow rate (mL per second), Outcome 1 Maximum flow rate (mL per second) at 1 month after operation.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Flow rate (mL per second), Outcome 2 Maximum flow rate (mL per second) at 6‐12 months after operation.

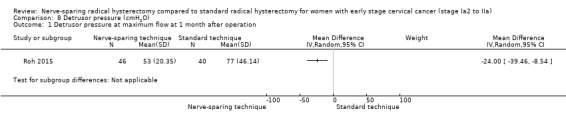

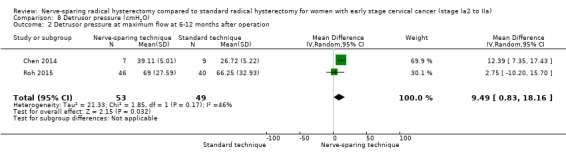

Detrusor pressure at maximum flow and number of women with low detrusor pressure

Roh 2015 noted lower detrusor pressure at one month after operation among women undergoing nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy than those in standard surgery group (MD‐24.00 cmH2O; 95 CI ‐39.46 to ‐8.54; Analysis 8.1). However, meta‐analysis assessing 102 women six to 12 months after operation showed a higher detrusor pressure among women undergoing nerve‐sparing surgery (MD 9.49 cmH2O; 95% CI 0.83 to 18.16; Analysis 8.2). The percentage of variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than to chance may represent moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 46%). No information on the number of women with low detrusor pressure at maximum flow was reported in any of the included studies.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Detrusor pressure (cmH2O), Outcome 1 Detrusor pressure at maximum flow at 1 month after operation.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Detrusor pressure (cmH2O), Outcome 2 Detrusor pressure at maximum flow at 6‐12 months after operation.

Sexual dysfunction

Only Chen 2014 reported the impact of nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy on sexual function using Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) at one year following surgery. Higher FSFI scores represent better quality of sexual life. Chen 2014 observed that women undergoing laparoscopic nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy had higher FSFI scores than women in the standard surgery group (23.34 ± 3.69 versus 17.57 ± 2.28; Chen 2014). However, the authors did not report the number of participants assessed in each comparison group. We, therefore, could not analyse the relative effect of different surgical techniques on the sexual functions among the comparison groups.

Cost‐effectiveness

The included studies did not report on cost‐effectiveness.

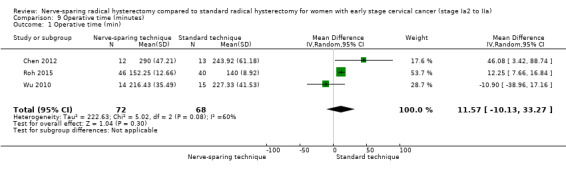

Operative time

Meta‐analysis of three included studies, which assessed a total of 140 women, showed that there was no difference in terms of operative time between the groups (MD 11.57 minutes; 95% CI ‐10.13 to 33.27; Analysis 9.1). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than chance may represent moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 60%). We did not include Chen 2014 in the meta‐analysis for this outcome due to insufficient data.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Operative time (minutes), Outcome 1 Operative time (min).

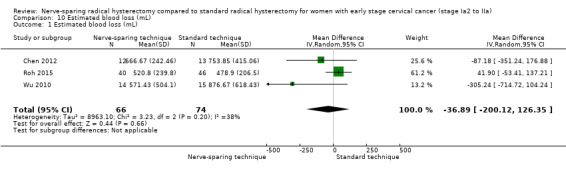

Estimated blood loss

Meta‐analysis of three included studies, which evaluated a total of 140 women, showed no difference in the amount of estimated blood loss between women who underwent nerve‐sparing operation and those who underwent standard operation (MD ‐36.89 mL; 95 CI ‐200.12 to 126.35; Analysis 10.1). The percentage of variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than chance was not important (I2 = 38%). We did not include Chen 2014 in the meta‐analysis for this outcome due to insufficient data.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Estimated blood loss (mL), Outcome 1 Estimated blood loss (mL).

Discussion

This review compared nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy to standard radical hysterectomy in individuals with early stage cervical cancer. Four small randomised controlled trials (RCTs) met the review inclusion criteria.

Summary of main results

We identified four small RCTs assessing a total of 205 women, but most of our analyses are based on fewer numbers of studies/women. The effectiveness and safety of nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy were incompletely assessed. All included studies had small sample sizes with an unclear risk of bias in most of the domains assessed, due to insufficient information provided. In addition, the results of the main comparisons were based on low‐ to very low‐certainty evidence. The very low‐certainty evidence for disease‐free survival (DFS) and lack of information for overall survival indicate that the oncological safety of nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy for women with early stage cervical cancer remains unknown. However, two women assigned to nerve‐sparing surgery died (one from Chen 2012 and one from Roh 2015), whereas no deaths occurred among women assigned to standard radical hysterectomy (Table 2). This finding may raise a concern about the safety of nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy for early stage cervical cancer, but the numbers are too small to draw meaningful conclusions and we are unable to tell whether this is due to chance or represents a true difference.

Nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy minimised the risk of postoperative bladder dysfunction. When compared to women who underwent standard radical hysterectomy, those who underwent nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy exhibited shorter times to small volume of postvoid residual urine (PVR), lower volume of PVR, and higher urethral closure pressure and flow rate as assessed by urodynamic study, indicating better urinary bladder function. In addition, women in the nerve‐sparing group were less likely to complain about urinary tract symptoms. There was no difference between the comparison groups with regard to measures of perioperative complications, estimated blood loss, and operative time.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Primary outcomes of this review were overall survival, rate of intermittent self‐catheterisation at one month following surgery, and quality of life. Only two of the included studies, including 111 women, reported survival data. As there had been two deaths among women in the nerve‐sparing group, but none in women assigned to standard surgery group, the relative effect measures on the risk of death could not be estimated (Table 2). None of the four included studies reported rate of intermittent self‐catheterisation at one month following surgery. One included study reported health‐related quality of life, but the reported data were inconsistent throughout the published article, precluding analysis of this outcome. Therefore, there were no available data for the analysis of primary outcomes of interest in this review.

Secondary outcomes of this review included postoperative bladder function, DFS, cancer recurrence, cost‐effectiveness, sexual functions, and perioperative outcomes. Although there were no differences between women undergoing nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy and those undergoing standard radical hysterectomy in terms of progression‐free survival or rate of cancer recurrence. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution as there were only five women who experienced recurrent disease, which is likely to be too infrequent to draw a meaningful conclusion. One included study reported postoperative sexual functions. However, the data were insufficient for analysis.

None of the four included studies reported data on urinary tract infection or cost‐effectiveness. We could not analyse the relative effect of the two surgical techniques on quality of life and sexual functions due to insufficient or inconsistent reported data.

Similar to all systematic reviews, applicability of evidence is limited by the quantity and quality of the review results. The lack of data regarding all primary outcomes of interest in this review and the low to very low certainty of available evidences regarding these outcomes (see Quality of the evidence) may make it difficult to generalise the findings of this review. Another potential limitation to the applicability of this review is that the operations in three of the four included studies were performed via laparotomy. Only one small study, assessing 65 women, used laparoscopy as the surgical approach, but analyses of some important outcomes (i.e. time to PVR < 100 mL and results of the postoperative urodynamic evaluation) were based on fewer (29 women and 16 women for each outcome, respectively). In addition, this study did not report survival rate and rate of cancer recurrence. As such, the applicability of the existing evidence to a group of women undergoing laparoscopic radical hysterectomy may be questionable.

Some outcome measures (i.e. quality of life, lower urinary tract symptoms and sexuality) may be affected by culture and ethnicity (Gotay 2002; Heinemann 2016; Maserejian 2014). As all four included studies were undertaken in Asian countries, findings of this review may not be fully applicable to populations in different settings.

Quality of the evidence

The lack of large, high‐quality RCT data is the fundamental limitation of this review. We identified four small RCTs with unclear risk of bias in most of the domains assessed. In addition, there was insufficient information available to assess the risks of selection and detection biases, which might preclude drawing a meaningful conclusion from the review. Another limitation of this review is the small number of included studies, which is reflected by the very large and non‐informative 95% confidence intervals in some comparisons. The relative small sample size also has the potential to affect its accuracy with regard to statistical heterogeneity (IntHout 2015; von Hippel 2015). Thus, we applied the random‐effects model for all meta‐analyses.

We assessed the certainty of evidence using the GRADE approach for the main outcomes (see Table 1). Based on the concerns regarding the unclear risk of the selection, performance, and detection biases with the small sample size, we downgraded the evidence to low certainty for time to postvoid residual volume of urine ≤ 50 mL, PVR volume of urine one month following operation, and rate of perioperative complications (Figure 2; Figure 3).

We downgraded the evidence to very low certainty for the estimation of DFS among the two comparison groups based on the unclear risk of bias for most of the domains assessed, the small sample size and small number of reported events, and application of unadjusted hazard ratios in the analyses (Figure 2; Figure 3). None of the included studies reported rate of intermittent self‐catheterisation following operation. In addition, we could not determine the relative effect of the two different surgeries on the overall survival and quality of life as there had been insufficient or inconsistent data reported.

The very low‐certainty evidence for DFS and lack of information for estimating the difference in overall survival noted in this review indicate that the oncological safety of nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy remains an issue of debate.

Potential biases in the review process

With assistance from the Information Specialist, Cochrane Gynaecological, Neuro‐oncology & Orphan Cancer Group, we conducted a comprehensive search, including a thorough search of the grey literature, conference proceedings, key textbooks, citation lists of included studies, and registered databases of ongoing trials. Two review authors independently sifted through all studies and extracted data. We restricted included studies to RCTs in order to obtain the best evidence. Thus, we have attempted to lessen bias in the review process. However, as there were few studies that were included in the review, there remains the possibility that there may be other unpublished studies that we did not discover. We were unable to assess this possibility as the analyses were limited to meta‐analyses that examined either a single or just small number of studies.

Another source of potential biases is the incomplete or inconsistent data reported in some included studies. Despite our best efforts, we were not able to get detailed data from the authors of the included studies. There were no issues associated with conflicts of interests of the authors of this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Several systematic reviews comparing nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy versus standard radical hysterectomy for early stage cervical cancer have been published in recent years (Aoun 2015; Basaran 2015; Kim 2015b; Long 2014; van Gent 2016; Xue 2016). Overall, the conclusions drawn from these reviews are consistent in that nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy resulted in less bladder dysfunction than standard radical hysterectomy without compromising the survival. However, this evidence should be interpreted with caution, as all of these systematic reviews included a body of non‐randomised evidence obtained from various forms of non‐randomised studies (NRSs). Despite lacking randomisation, high‐quality NRSs can sometimes complement the evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Schünemann 2013). However, it has been acknowledged that there is no standard surgical techniques for nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy. Therefore, there is likely a wide variation in surgical techniques used for this procedure across various settings (Sakuragi 2015). In addition, NRSs undertaken to evaluate nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy usually involved small sample sizes. These may be key limitations of NRSs, leading to a substantial heterogeneity when attempting to perform meta‐analyses, as has been noted in previous reviews (Kim 2015b; Long 2014; van Gent 2016; Xue 2016). As such, we did not include NRSs, as they were unlikely to contribute to the certainty of evidence.

In this review, all included studies were RCTs comparing two techniques for performing Piver class III radical hysterectomy in order to diminish the amount of variation in the procedure. Similar to previous reviews, we found that nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy may lessen bladder dysfunction following operation compared to standard radical hysterectomy. However, there is insufficient evidence from RCTs to ascertain the oncological safety of nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy for women with early stage cervical cancer.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Low‐ to very low‐certainty evidence obtained from the four small randomised controlled trials (RCTs) indicated that women undergoing nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy are at decreased risk of postoperative bladder dysfunction when compared to those who underwent standard radical hysterectomy. However, these trials had insufficient numbers of women and there was a lack of data regarding clinically important outcomes.

In addition, there is insufficient evidence to indicate whether nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy offers an oncological efficacy equivalent to standard radical hysterectomy for women with early stage cervical cancer.

Implications for research.

We were not able to estimate the relative effect of nerve‐sparing surgery compared to standard surgery on overall survival, quality of life, and sexual dysfunction, due to lack of long‐term outcome data. As recurrence rates are low in this group of patients, an adequately powered, international, high‐quality, randomised controlled trial is necessary to re‐assess whether nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy is an oncological equivalent to, and results in less morbidity than, standard radical hysterectomy for women with early stage cervical cancer.

Over the past 10 to 20 years, a minimally invasive radical hysterectomy has been widely introduced (Park 2017; Spirtos 2002). Several studies have reported high feasibility and safety of nerve‐sparing radical hysterectomy performing via laparoscopic or robotic‐assisted techniques (Chong 2013; Kim 2015a; Kyo 2016). As stated earlier, the surgical approach in one included study of this review was laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (Chen 2014; see Characteristics of included studies). There is one ongoing study comparing conventional versus nerve‐sparing hysterectomy using laparoscopic approach (Gaballa 2015; see Characteristics of ongoing studies). However, early findings from the multicentre, international Phase III randomised study suggested that women with early stage cervical cancer who underwent laparoscopic or robotic‐assisted radical hysterectomy carried higher rates of disease recurrence and worse survival than women who underwent surgery via an open approach (Ramirez 2018). These unexpected findings may raise further questions of whether minimally invasive radical hysterectomy continues to be a viable option for future research in surgical treatment for early stage cervical cancer.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jo Morrison for clinical and editorial advice; Jo Platt for designing the search strategy; Gail Quinn, Clare Jess and Tracey Harrison for their contributions to the editorial process; and Dylan Southard for assisting with English language presentation.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Gynaecological, Neuro‐oncology and Orphan Cancers Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the review authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS, or the Department of Health.

We would like to thank the referees for many helpful suggestions and comments, some of these referees include Janos Balega, Elly Brockbank, Andy Bryant, Fani Kokka and John Tidy.

Appendices

Appendix 1. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging for carcinoma of the cervix

| FIGO Stage | Description | ||

| I | The carcinoma is confined to the cervix. | ||

| IA | Invasive cancer identified only microscopically. (All gross lesions even with superficial invasion are Stage IB cancers.) Invasion is limited to measured stromal invasion with a maximum depth of 5 mm and no wider than 7 mm. | ||

| IA1 | Measured invasion of stroma ≤ 3 mm in depth and ≤ 7 mm width | ||

| IA2 | Measured invasion of stroma > 3 mm and < 5 mm in depth and ≤ 7 mm width | ||

| IB | Clinical lesions confined to the cervix, or preclinical lesions greater than stage IA | ||

| IB1 | Clinical lesions no greater than 4 cm in size | ||

| IB2 | Clinical lesions > 4 cm in size | ||

| II | The carcinoma extends beyond the uterus, but has not extended onto the pelvic wall or to the lower third of vagina. | ||

| IIA | Involvement of up to the upper two‐thirds of the vagina. No obvious parametrial involvement | ||

| IIA1 | Clinically visible lesion ≤ 4 cm | ||

| IIA2 | Clinically visible lesion > 4 cm | ||

| IIB | Parametrial involvement, but not onto the pelvic sidewall | ||

| III | The carcinoma has extended onto the pelvic sidewall. On rectal examination, there is no cancer free space between the tumour and pelvic sidewall. The tumour involves the lower third of the vagina. All cases of hydronephrosis or non‐functioning kidney should be included unless they are known to be due to other causes. | ||

| IIIA | Involvement of the lower vagina but no extension onto pelvic sidewall | ||

| IIIB | Extension onto the pelvic sidewall, or hydronephrosis/non‐functioning kidney | ||

| IV | The carcinoma has extended beyond the true pelvis or has clinically involved the mucosa of the bladder and/or rectum. | ||

| IVA | Spread to adjacent pelvic organs | ||

| IVB | Spread to distant organs | ||

Appendix 2. Classifications of radical hysterectomy

| Piver‐Rutledge‐Smith (Piver 1974) | Extent of surgery | |

| Class I: extrafascial hysterectomy |

|

|

| Class II: modified radical hysterectomy (Wertheim) |

|