Abstract

Common Data Elements (CDEs) are defined as “data elements that are common to multiple data sets across different studies” and provide structured, standardized definitions so that data may be collected and used across different datasets. CDE collections are traditionally developed prospectively by subject-matter and domain experts. However, there has been little systematic research and evidence to demonstrate how CDEs are used in real-world datasets and the subsequent impact on data discoverability. Our study builds upon previous mapping work to investigate the number of CDEs that could be identified using a varying level of commonness threshold in a real-world data repository, the Database of Phenotypes and Genotypes (dbGaP). In an analyzed collection of mapped variables from 426 dbGaP studies, only 1,414 PhenX variables (PHENotypes and eXposures; a CDE initiative) are observed out of all 24,938 defined PhenX variables. Results include CDEs that are identified with varying levels of commonness thresholds. After the semantic grouping of 68 PhenX variables collected in at least 15 studies (n=15), we observed 32 truly “common” common data elements. We discuss benefits of post-hoc mapping of study data to a CDE framework for purposes of findability and reuse, as well as the informatics challenges of pre-populating clinical research case report forms with data from Electronic Health Record that are typically coded in terminologies aimed at routine healthcare needs.

Introduction

In recent years, sharing of de-identified individual patient level data from observational and interventional human clinical studies is slowly becoming the norm. Because of this trend, researchers began to pay greater attention to research Common Data Elements (CDEs) that are defined as data elements that are common to multiple data sets across different clinical studies. CDEs provide structured, standardized definitions so that data may be collected and used across different datasets. Citing Sheehan et al,1 institutes and centers within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have been involved in the identification and development of CDEs for more than 20 years. In general, CDEs are identified and specified by a working group of subject-matter experts and their draft recommendations are reviewed through a public vetting process and then released. These recommendations (and in some instances, requirements) are designed for prospective studies, that is, to be used before the data collection process begins. There has been an increase in amount of NIH funding opportunity announcements that include mention of “common data elements” but little to no research on the implementation of CDEs in real-world data.

This study explores real world use of data elements found in past clinical studies deposited in data sharing platforms, such as ClinicalTrials.gov, Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) or Project Data Sphere. We illustrate this approach using the example of the PHENotypes and eXposures Toolkit (PhenX) and dbGap database. PhenX research common data element initiative2,3 defines 24,938 data elements; however, when we consider individual participant data from several hundred past clinical studies that are linked to PhenX, only 1,414 PhenX variables were used at least once in a real world shared dataset. When all CDEs from different initiatives are combined (not taking real world usage into account), the total number of data elements can be overwhelmingly high. By focusing only on CDEs that are used by past studies, we hope to better focus the efforts around further harmonization of CDEs across various initiatives. Past frequency of use of individual research data elements can also help guide researchers select relevant CDEs when searching a CDE repository. Our investigation of real world use of CDEs is also driven by our need to generate a small subset of highly used CDEs that we plan to use in a related project that focuses on annotation of CDEs with routine healthcare terminologies.4

Materials

Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes

dbGaP is a repository of patient level study data maintained by National Center for Biotechnology Information at the National Library of Medicine (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap). It was developed to archive and distribute the data and results from studies that have investigated the interaction of genotype and phenotype in humans. This initiative was partially driven by NIH Genomic Data Sharing Policy.5 For each included study, there are documents (such as informed consent or study protocol), variables (e.g., peak bilirubin level), datasets and analyses. It includes studies that, in addition to phenotypic data, also collected genomic data (e.g., whole exome sequencing or genotyping).

PhenX

The PhenX Toolkit is a catalog of recommended, standard measures of phenotypes and environmental exposures for use in biomedical research (www.phenxtoolkit.org). The abbreviation stands for Phenotypes and eXposures. It was designed to facilitate cross-study analysis, potentially increasing the scientific impact of individual studies. PhenX is funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute with co-funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. It is organized into protocols, measures and variables. PhenX was adopted by dbGaP6 and data from past studies were mapped to PhenX variables (post-hoc mapping) to make it easier for researchers that want to re-use data from past studies. Mapping performed centrally and at the repository level eliminates the need for each data re-using researcher to perform this mapping locally once data is downloaded. PhenX variables and protocols have been modelled in LOINC (Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes) and in Cancer Data Standards Registry and Repository (caDSR).6 PhenX employs composite IDs to identify variables, protocol and measures. These IDs can be derived from the 12 digit variable ID. For example, for variable ‘Weight’ with ID PX150203030000, the protocol ID is the first six digits (150203) and it identifies the ‘Integrated Fitness - Child’ protocol. Last 6 digits identify specific PhenX variables within protocols. PhenX Protocol ID can further be decomposed into domain (first 2 digits; code 15 identifies Physical Activity and Physical Fitness domain), measure (adding the middle 2 digits; code ‘1502’ identifies ‘Integrated Fitness measure’) and protocol (last 2 digits).

Methods

We adopted a definition of CDE that states that a data element is common if it is shared by at least n studies. (where n >=2). An alternative way to describe the value of n is commonness threshold value. We used dbGaP variable mapping file (obtained in October 2017) that provides usage of different data elements across a large set of clinical studies. A similar but not identical mapping is available on the PhenX website.7 We analyze how often different data elements are used and determine how many data elements satisfy a definition of a common data element with increasing value of n. In the second step, we used a commonness threshold value of n=15 (semantic pilot subset) and analyzed a subset of data elements using manual semantic mapping approach (single mapper; pilot analytical approach). We chose a threshold of 15 in order to reduce the number of manual mappings required to be made. Our goal was to arrive at pilot results about how CDEs (at PhenX variable level) can be best grouped.

Results

dbGaP input data

We used an existing mapping between clinical study variables (deposited in dbGaP) and PhenX variables obtained from the dbGaP team. This mapping was created by an external contractor (RTI International). This contractor is also the custodian for the PhenX toolkit website and the PhenX CDE collection. The mapping file contained 20,635 study variables from 426 dbGaP studies that were mapped to 1,414 distinct PhenX variables. Note that as of March 2018 dbGaP contains a total of 902 studies. We chose not to further convert the 1,414 PhenX variables to a higher level PhenX construct of PhenX measure in order to preserve the mapping at the original granularity level on which it was produced. This variable-measure hierarchical relationship can, in some cases, provide useful semantic aggregation. For example, three PhenX variables of ‘Medical Record Birthweight Gram’ (PX020201010100), ‘Medical Record Birthweight Pound’ (Variable ID: PX020201010200) and ‘Medical Record Birthweight Ounce’ (PX020201010300) and all grouped under PhenX measure ‘Birth Weight’ (measure ID: 020200).8 However, for a significant proportion of other PhenX variables, we found this relationship not useful. This conclusion is further supported by the deprecation of PhenX measures concepts in the LOINC terminology (deprecated in LOINC version 2.46 from Dec 26, 2013). The official LOINC deprecation reason is the following: ‘Reason for deprecated status: Measure terms were added to match PhenX hierarchy but make it difficult to locate protocols (which contain the set of variables you would use for a particular purpose). They have been deprecated and mapped directly to protocols. No replacement term defined.’ See LOINC concept page for a representative concept.9 In our study, we chose not to use the abstraction to PhenX protocol construct because it does not preserve semantic granularity needed for our analysis (e.g., Demographic protocol (PhenX protocol ID 010000) merges gender, race, age and marital status into a single protocol ID). PhenX website allows display of any protocols using the following URL pattern https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/ index.php?pageLink=browse.protocoldetails&id=<ProtID>

Sensitivity analysis of data element frequency (commonness threshold)

After establishing the optimal level of input data element aggregation (PhenX variable level), we proceeded to the analysis of frequency of use by different studies in dbGaP included in the mapping file. The most common data element identified across studies was gender (PhenX variable ID PX010701010000, LOINC code 46098-0) used in 344 studies. On the other end of the frequency of element use spectrum, 654 data elements are used only in a single study (46% out of all 1,414 elements with study data).

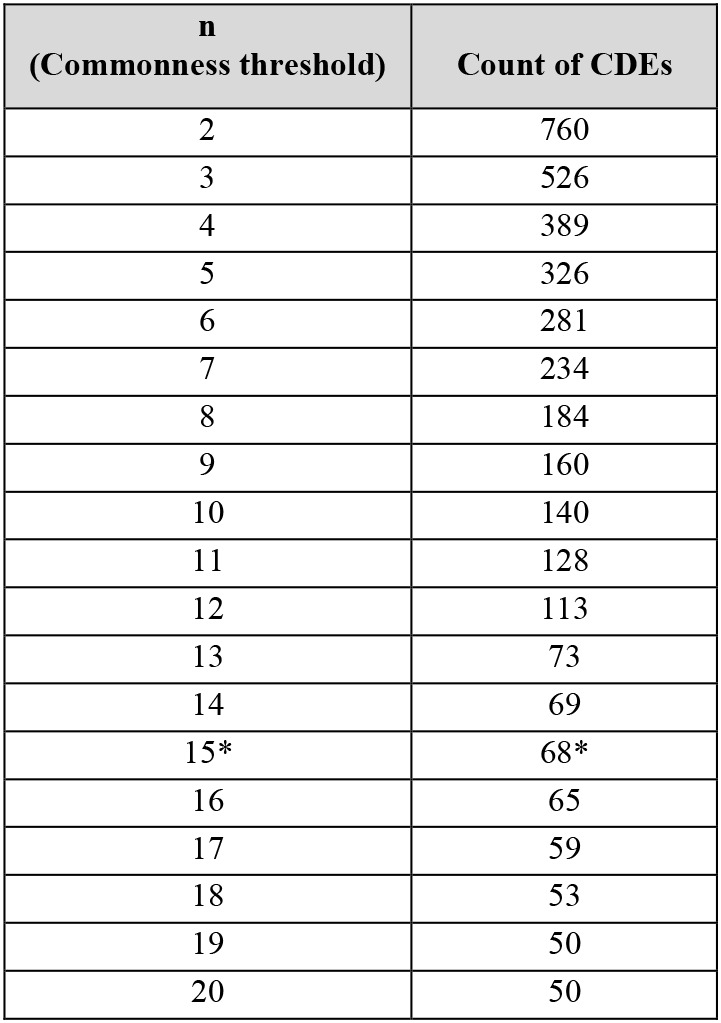

Table 1 shows how many CDEs could be identified (second column) with an increasing value of n for commonness threshold, starting with n of 2 that gives the largest count of 760 CDEs. The table is limited to 20 rows; however, full table is available in the project repository (at https://github.com/lhncbc/CDE) as supplemental table S1.

Table 1.

Number of CDEs as a function of n (* indicates the semantic pilot subset analyzed in the second step)

|

To illustrate the Table 1 results, we see, for example, that given a collection of 426 dbGaP studies and a requirement of at least 5 or more studies to be collecting the same data element, we would find that 326 data elements are considered common under such definition. If we require that at least 15 or more studies collect the same element as commonness threshold, the number of CDEs drops to 68 elements. These results are highly dependent on (1) the level of mapping granularity (PhenX variable level) due to possible semantic duplicates, (2) the sample of studies being mapped to the data harmonization framework (only dbGaP studies which are mostly studies with a genomic component) and (3) the clinical breath and information model of the targeted data harmonization framework (PhenX catalog and PhenX protocol-measure-variable information model).

Semantic analysis of Common Data Elements

Table 2 shows CDEs (PhenX variables) that appear in at least 15 studies. Only the top 25 CDEs are shown in the table when ordered by CDE usage. See supplemental files S2 for all 1,414 variables and supplemental file S3 for the full semantic pilot subset in project repository. The S3 file includes LOINC mapping columns in addition to the SNOMED column listed in Table 2. In order to semantically group the most frequent data elements, we mapped each PhenX variable to a SNOMED CT concepts (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine) and, where applicable, to a LOINC concept. We observed several phenomena in data elements semantics that we summarize below.

Table 2.

Top 25 CDEs in dbGaP when ordered by usage frequency (column ‘# of studies’) (SCT stands for SNOMED CT; SCTID is a SNOMED CT concept identifier)

| PhenX Variable ID | PhenX Variable Name | # of studies | SCT concept | SCTID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PX010701010000 | Gender | 344 | Gender | 263495000 |

| PX091601390000 | Sex | 330 | Gender | 263495000 |

| PX120701020000 | Sex_Code | 330 | Gender | 263495000 |

| PX091601400000 | Race | 190 | Race | 103579009 |

| PX021501030100 | Measured_Weight_1_Pounds | 84 | Body weight | 27113001 |

| PX021501030200 | Measured_Weight_2_Pounds | 84 | Body weight | 27113001 |

| PX021501030600 | Measured_Weight_2_Kilograms | 84 | Body weight | 27113001 |

| PX021501030700 | Measured_Weight_3_Kilograms | 84 | Body weight | 27113001 |

| PX091601380000 | Weight | 84 | Body weight | 27113001 |

| PX130501200000 | Weight | 84 | Body weight | 27113001 |

| PX141001100000 | Weight | 84 | Body weight | 27113001 |

| PX141001100100 | Weight_Units | 84 | Unit | 258666001 |

| PX150101010000 | Weight | 84 | Body weight | 27113001 |

| PX150203030000 | Weight | 84 | Body weight | 27113001 |

| PX151401030000 | Weight | 84 | Body weight | 27113001 |

| PX091601370000 | Height | 83 | Body Height | 50373000 |

| PX120601200000 | Self_Reported_Height | 83 | Body Height | 50373000 |

| PX120601190000 | Self_Reported_Weight | 81 | Body weight | 27113001 |

| PX010101020000 | Age | 44 | Age | 424144002 |

| PX010101020100 | Age_Coded | 38 | Age | 424144002 |

| PX091601360000 | Age | 36 | Age | 424144002 |

| PX120701030000 | Age | 36 | Age | 424144002 |

| PX010501010000 | Hispanic_Ethnicity | 35 | Ethnicity | 397731000 |

| PX010101010300 | Birthdate_Year | 34 | Date of Birth | 184099003 |

Same variable in multiple protocols: Some variables appeared (with identical variable name) in multiple protocols. For example, ‘Weight’ variable appeared as separate PhenX variable in protocols ‘Cardiorespiratory Fitness - Exercise Test Estimate - One Mile Walk’ protocol (protocol ID: 150101) and ‘Oral Glucose Tolerance Test’ protocol (protocol ID: 141001). We mapped such identical variables to SNOMED CT/LOINC concept for weight and considered them a single data element. The presence of multiple weight variables in PhenX is partially by design and is related to the PhenX conceptual model (PhenX concepts of Domain → Collection → Measure → Protocol → Variable; see ‘About PhenX Toolkit’ section of their website). This design may not be optimal from the perspective of data re -using researcher.

Similar variables: Some variables measured the same underlying concept but used different data collection mechanism. For example, ‘Self reported height’ and ‘Height’. We mapped such similar variables to SNOMED CT/LOINC concept for height and considered them a single data element.

Highly granular Boolean variables: Some variables were boolean or flag indicators for a concept value of a higher level data element. For example, ‘Race white’, ‘Race black’ boolean variables. We mapped such granular boolean variables to the higher SNOMED CT/LOINC concept (the concept of race in the listed example above).

After semantic mapping, we identified 32 distinct CDEs (in the subset of 68 CDEs using the threshold of 15). The six most common CDEs after semantic mapping were gender, weight, height, age and race. Complete list of semantic grouping concepts is available in supplemental file S3. Due to sometimes greater granularity required for research data collection (domain of CDEs) and sometimes lower granularity required for routine healthcare (domain of SNOMED CT and similar terminologies), for example, in collecting data on smoking frequency, some CDEs could not be mapped to a single concept in SNOMED CT/LOINC. However, this context of missing target concept was observed in only 4 data elements in our semantic pilot subset. A partial motivation for our semantic pilot study was to assess the feasibility to populate research data collection from EHR data (encoded in LOINC and SNOMED), therefore we considered non-matching elements as a separate higher semantic group. In related prior work by our research group, we explored the use of post-coordinated SNOMED CT expressions to model complex research data elements.4

Discussion

Many CDE initiatives use expert consensus to arrive at common research data elements to be recommended in future studies (a top-down approach). In contrast, our study is unique by looking at the real world use of research data elements (dbGaP collection of actual shared study data from completed studies). We use a bottom-up approach (driven by real world completed studies) to identify common data elements. A large number of all defined PhenX variables (more than 24,000 variables) reduces to 1,414 elements observed in dbGaP deposited studies (given the mapping file used in our study). The universe of data elements further reduces to 760 CDEs if we require that at least 2 studies collect the same element. Adopting yet higher commonness threshold of n=15 and mapping to higher semantic concepts, we observed only 32 common data elements. Our choice of commonness threshold of 15 (CDEs that are shared by at least 15 studies) was driven by our goal to produce some pilot results and to limit the amount of manual mapping. For a larger sample of studies (e.g., more than 426 that were used in this work) or groups of studies by therapeutic area, a different commonness threshold may be more appropriate. Further research that produces data similar to our Table 1 results (number of CDEs observed as a function of the commonness threshold) using different study repositories (besides dbGaP) is needed.

Our work complements previous analyses of CDEs. Carter at al. analyzed drug-related standards across HL7, openEHR, PhenX and caDSR.10 For the domain of substance abuse and addiction, Conway at al. analyzed 141 active and submitted grants for CDEs.11 In contrast to these studies, our work analyzes directly data presented to data re-using researchers by looking at a patient-level study data repository. The most closely related work (on a much smaller sample of 23 studies and using case report forms data as input) by Bruland at al. study from 2016 identified 133 common data elements.12

Limitations

Our results are limited by several factors. First, the sample of studies, including when it was generated, greatly affects what CDEs are identified. Inclusion of few large studies with large number of phenotypic variables can significantly affect the results especially when lower commonness thresholds are chosen. For example, in our sample of 426 studies, the studies with the largest number of PhenX variables were ‘Whole Genome Association Study of Bipolar Disorder’ (361 variables), ‘Framingham Cohort’ (316 variables), ‘Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Cohort’ (274 variables), ‘CARDIA Cohort’ (269 variables) and ‘GWAS on Cataract and HDL study in the PMRP’ (268 variables). Supplemental file S2 lists all study names for a given PhenX variable and supplemental file S4 lists separately all studies in our sample. A larger set of studies would likely lead to more accurate characterization of CDEs. We have performed similar (but more limited) analysis on 28,812 studies from ClinicalTrials.gov (CTG) basic summary results database. We analyzed 2,101 distinct baseline data elements titles (n >=2) and 1,155 outcomes data elements titles (n >=5). CTG does not perform any central semantic post-processing similar to dbGaP and our limited CTG analysis did not include any semantic grouping effort. See project repository for limited CTG results.

Second, our semantic grouping and pilot semantic analysis is biased by being performed by a single mapper and by our mapping design choices (threshold of 15, and SNOMED CT/LOINC as mapping targets).

Benefits and challenges of CDEs

Repositories of past studies that are mapped to a CDE initiative (such as PhenX) facilitate analysis for researchers re-using collected data and aggregating data across studies. A centrally performed post-hoc mapping of study data allows map-once-use-many paradigm where each data user does not have to map the data locally during data re-use time. Many study data repositories leave the data in the native format (as submitted by researchers) and dbGaP is one of few pioneering repositories that experiment with post-hoc data mapping14 (mapping of data to CDE not at study design stage prior to study start but after the date where data has been collected). Via further mapping of PhenX CDEs to LOINC codes, dbGaP essentially also supports data retrieval using a clinical terminology (see Figures 1 and 2). Figure 3 shows a search strategy that looks for studies with gender, weight and year of birth. As of March 2018, 12 studies out of all 906 studies in dbGaP are retrieved by this search. Many CDE initiatives, that are traditionally oriented towards researchers as target users and focus on the clinical research domain, are realizing a possible relationship to EHR records and routine healthcare terminologies, such as LOINC, SNOMED CT or RxNorm.4

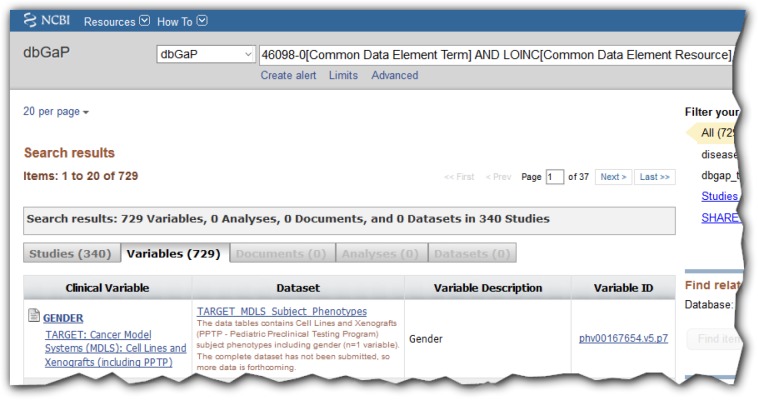

Figure 1.

Search results in dbGaP for LOINC code for gender (46098-0) with 340 studies found. See13 for search details.

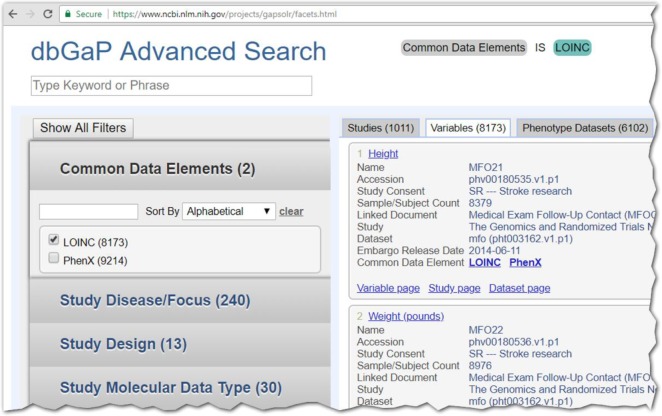

Figure 2.

Partial screenshot of advanced search (variables tab) in dbGaP showing the LOINC search filter capability

Figure 3.

Search string to retrieve studies with gender (46098-0), weight (3141-9) and year of birth (mapped to LOINC concept of birth date; 21112-8) in dbGaP

Conclusion

Our study shows a bottom-up approach to defining what is a common data element. After semantic grouping and a high-bar definition of a CDE, we observed only 32 common data elements in a collection of 426 studies.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/ National Library of Medicine (NLM)/ Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications (LHNCBC). The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of NLM, NIH, or the Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- 1.Sheehan J, Hirschfeld S, Foster E. Clin Trials. 2016. Improving the value of clinical research through the use of Common Data Elements. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stover PJ, Harlan WR, Hammond JA, Hendershot T, Hamilton CM. PhenX: a toolkit for interdisciplinary genetics research. Current opinion in lipidology. 2010;21(2):136–40. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283377395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarty CA, Huggins W, Aiello AE. PhenX RISING: real world implementation and sharing of PhenX measures. BMC. medical genomics. 2014;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huser V, Burke C, Nguyen M, Amos L. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2017. Annotation of Research Common Data Elements Using Clinical Terminologies. [Google Scholar]

- 5.NIH. Genomic Data Sharing (GDS) Policy. 2015. https://osp.od.nih.gov/scientific-sharing/genomic-data-sharing (accessed Feb 1 2018).

- 6.Pan H, Tryka KA, Vreeman DJ. Using PhenX measures to identify opportunities for cross-study analysis. Human mutation. 2012;33(5):849–57. doi: 10.1002/humu.22074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.PhenX. Resources. 2017. https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/index.php?pageLink=resource.download (accessed March 4 2018)

- 8.PhenX. Birth Weight Measure. 2017. https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/index.php?pageLink=browse.protocols&filter=1&id=020200 (accessed Feb 15 2018)

- 9.LOINC. Term 62262-1. 2017. https://r.details.loinc.org/LOINC/62262-1.html?sections=Comprehensive (accessed Feb 15 2018)

- 10.Carter EW, Sarkar IN, Melton GB, Chen ES. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. 2015 2015. Representation of Drug Use in Biomedical Standards, Clinical Text, and Research Measures. pp. 376–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conway KP, Vullo GC, Kennedy AP. Data compatibility in the addiction sciences: an examination of measure commonality. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2014;141:153–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruland P, McGilchrist M, Zapletal E. Common data elements for secondary use of electronic health record data for clinical trial execution and serious adverse event reporting. BMC medical research methodology. 2016;16(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0259-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.dbGaP. Search for gender in dbGaP. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap?doptcmdl=SVariables&term=46098-0[Common+Data+Element+Term]+AND+LOINC[Common+Data+Element+Resource] (accessed March 10 2018)

- 14.Huser V, Bloomberg D. Clin Trials. 2018. Data Sharing Platforms for De-identified Data from Human Clinical Trials (accepted; in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]