Abstract

Engaging healthcare providers in acute care patient portal implementation is critical to ensure productive use. However, few studies have assessed provider’s perceptions of an acute care portal after implementation. In this study, we surveyed 63 nurses, physicians, and physician assistants following a 3-year randomized trial of an acute care portal. The survey assessed providers’ perceptions of the portal and its impact on care delivery. Respondents reported that the portal positively impacted care, and they perceived that their patients found it usable and trustworthy. Respondents reported that all the portal’s features were useful, especially the display of laboratory test results. Compared with the results of a patient survey, providers underestimated the portal’s usefulness to patients, and ranked features as very useful significantly less often than patients (57% vs. 74%; p<0.001). Our study found that providers supported their patients’ use of the portal, but may have underappreciated the portal’s value to patients.

Introduction

Over 92% of US healthcare organizations offered online patient portals in 2015, an increase from only 43% in 2013.1 Despite their widespread availability outside the hospital, few portals offer electronic access to information for hospitalized patients.2,3 The US meaningful use financial incentive program for electronic health record (EHR) adoption requires that hospitals provide the capability for patients to view, download, and transmit their own health information.4 However, information release is not required until 36 hours after hospital discharge.5

Even without well-aligned financial incentives, some healthcare organizations have adopted acute care patient portals, or portals available in the hospital setting.6-9 Acute care portals have been reported to improve the patient’s hospital experience,10 support patient-provider communication,11-16 prevent medical errors,11,17-19 and promote patients’ engagement in care.20-22 Hospitalization is a stressful time for many patients and families, and acute care portals may provide information that can reduce their stress. In the US, the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guarantees patients’ right to review their medical data. Acute care portals can actualize this provision, by overcoming barriers such as time delays and photocopying costs.

Despite the potential benefits, the adaptation of patient portals to the inpatient setting presents challenges. One challenge is implementing acute care portals without negatively impacting care delivery, while at the same time maximizing the portal’s potential to improve the communication of health information.10 In previous studies, healthcare providers have expressed concerns about sharing information such as laboratory test results through portals, including increased anxiety, anger, and confusion from patients.20,23 Engaging providers in the implementation of acute care portals is critical to prevent such unintended negative consequences.

Previous studies have engaged healthcare providers in acute care portal development, and described providers’ perspectives on portal content.11,20,23-27 A remaining gap is to assess providers’ perceptions of acute care portals and their impact on care delivery after implementation.8,28,29 To address this gap, we surveyed physicians, physician assistants, and nurses to evaluate their perceptions of an acute care portal used in a three-year randomized trial. The portal displayed the patient’s health information and offered communication features, such as entering comments and recording pain level. The survey assessed providers’ 1) perceptions of patients’ technology use, 2) perceptions of the acute care portal and its impact on care delivery, and 3) perceptions of the usefulness of portal features.

Methods

Study Design

The randomized trial was conducted from March 2014 to May 2017 on two medical and surgical step-down units at an urban academic medical center. The protocol for this trial has been previously described6 and the trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01970852). Patient surveys were included in the study protocol. In June 2017, after the completion of patient recruitment, we surveyed healthcare providers working on the study units to assess their perceptions. The Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Provider Surveys

A content expert used an iterative process to develop the provider survey instrument. The instrument was based on provider surveys from previous studies,20,23,26,30 as well as the Telemedicine Satisfaction and Usefulness Questionnaire.31 The instrument was tested and reviewed by the study team, which included 3 clinicians and an expert in questionnaire development. Questions used both negatively and positively worded stems to guard against acquiescence.

The final survey contained 5 items on inpatients’ technology use, 8 items on perceptions of the portal and its impact on care, and 8 items on usefulness of portal features. Questions about perceptions and usefulness were answered on Likert-type scales. In addition, we included 2 questions about the provider’s role and number of years in that role. The survey was delivered both using paper and electronically using an online tool (Qualtrics LLC, Provo, UT).

Participants and Recruitment

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: We included healthcare providers who worked directly with patients hospitalized on the trial units within the past 3 years. We excluded healthcare providers who claimed they were unaware of the trial.

Recruitment Protocol: A research coordinator administered surveys to providers working on the floor. The coordinator approached providers during a convenient time for them and secured informed consent of participants. Additionally, a member of the study team sent an email to providers inviting them to participate. Recruitment continued until all 66 providers working daytime shifts had been contacted.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using R version 3.3.3. To examine differences in responses by provider role and years in role, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test for ordinal data and Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for nominal data. We used a significance level of p<0.05 for all statistical tests.32 For the Kruskal-Wallis test, subsequent pairwise comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. To examine differences in responses by question, we used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Where the same question was administered to patients in the patient survey6 and to providers in the provider survey, we compared responses. To examine differences in patients’ and providers’ responses, we used the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test for ordinal data. For items within the usefulness of features section of the survey, we conducted a factor analysis and reported the Cronbach’s alpha.

Results

Study Population

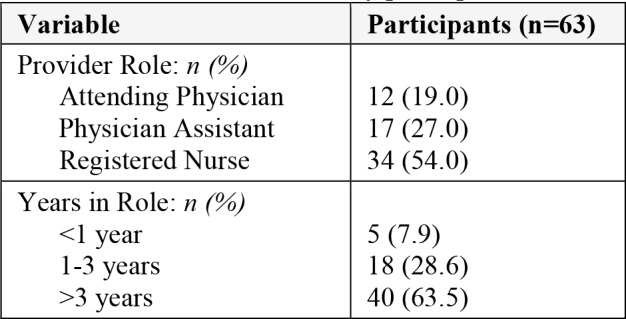

Of the 66 providers approached, 63 (95.5%) completed the survey (Table 1). The 3 individuals who did not complete the survey stated that they were unaware of the acute care portal trial. Participants included attending physicians (19%), physician assistants (27%), and nurses (54%). Most participants (64%) had over 3 years of experience working in their current role.

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey participants.

|

Perceived Technology Use of Inpatients

Most providers (81%) reported a belief that more than 50% of their patients used a personal laptop, tablet, or smartphone during their hospital stay. However, fewer providers (48%) reported a belief that more than 75% of their patients used a personal device. Moreover, nurses were significantly more likely than other providers (65% vs. 29%; p=0.006) to report that more than 75% of their patients used a personal device.

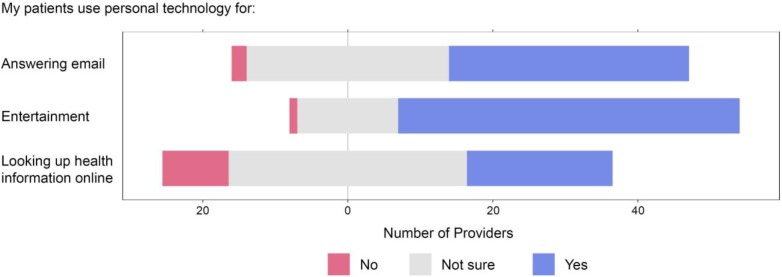

While most providers reported a belief that their patients used technology for email and entertainment, fewer knew whether patients used technology to find health information online (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Perceived technology use of inpatients.

Providers’ Perceptions of the Acute Care Patient Portal

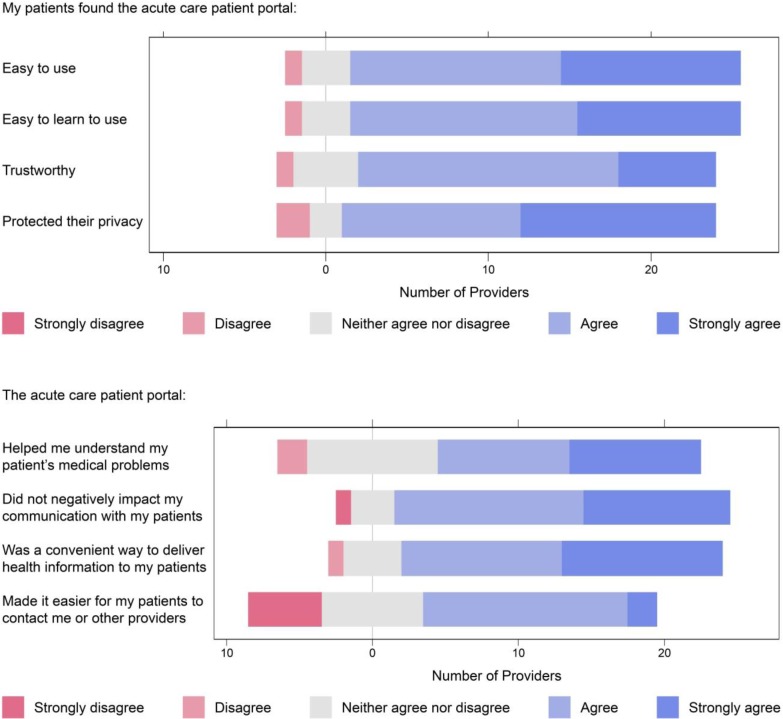

Of the 63 participants, 28 (44%) reported caring for one or more patients who used the acute care portal. In general, providers reported a belief that their patients found the portal usable and trustworthy, and that the portal positively impacted care delivery (Figure 2). Providers did not report any patients who found inaccurate information in the portal, even though 24 (17%) portal users reported finding inaccurate information, and 7 (6%) reported communicating that inaccurate information to a provider.

Figure 2.

Providers’ perceptions of the acute care patient portal.

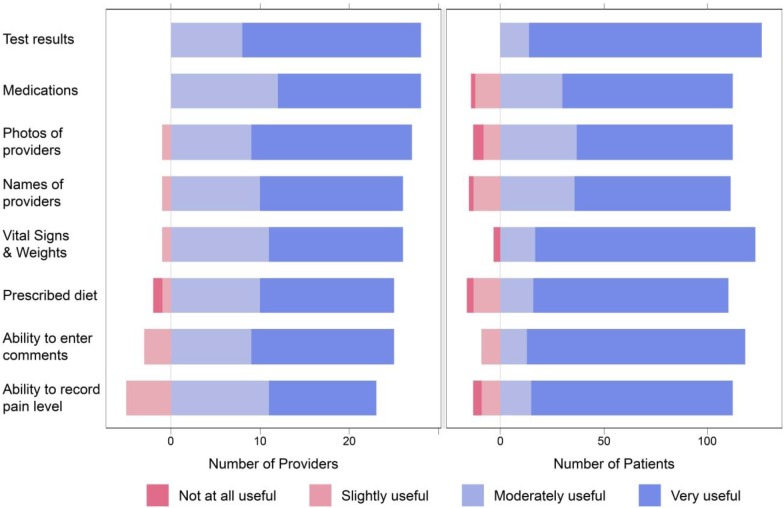

Perceived Usefulness of Portal Features for Hospitalized Patients

In general, providers and patients reported that the acute care portal’s features were useful (Figure 3). Both providers and patients agreed that the most useful feature was the laboratory test results. Overall, providers ranked features as very useful significantly less often than patients (p<0.001). Providers ranked features as very useful 57% of the time, while patients ranked them as very useful 74% of the time. In particular, providers underestimated the importance of the ability to enter comments (83% vs. 57% very useful; p=0.005), the ability to record pain level (77% vs. 43% very useful; p<0.001), and vital signs and weight (84% vs. 54% very useful; p=0.002) to patients. Cronbach’s alpha for all items about usefulness of features is 0.960, indicating high internal consistency.

Figure 3.

Perceived usefulness of portal features for hospitalized patients.

Discussion

This study assessed providers’ perceptions of an acute care patient portal used in a randomized controlled trial. The portal displayed the patient’s health information and offered basic communication features, such as entering comments and recording pain level. In general, providers found the portal useful, usable, and trustworthy, and reported a positive impact on care delivery. These results may allay concerns that providers are reluctant to share health information with patients via an acute care portal.33

Few physicians and physician assistants (29%) thought that more than 75% of their patients carried personal devices. However, data on personal devices in the United States suggest that most patients carry them, particularly in urban areas. In 2018, the Pew Research Center reported that 83% of urban Americans use smartphones, with similar usage statistics reported among Black, Latino, and older adults (ages 50-65).34 At our institution, 91.3% of patients reported owning a personal computer. When compared with these data, our results suggest that physicians and physician assistants underestimate their patient’s technology use. One possible reason is the stereotype that older individuals do not use technology.35 Perceiving certain patients as less likely to use technology may impact how providers promote acute care portals to those patients. Ancker and colleagues studied the impact of a universal access policy on patient portal use in the outpatient setting.36 The policy required hospital staff to offer portal access to all patients. As a result, disparities in portal use by age disappeared. In fact, older patients became more likely to become repeat users than younger patients. Implementers of acute care portals should consider similar policies or training to encourage providers to promote use among all patients in the hospital setting.

Similarly, most providers did not know whether their patients used technology to find health information online. Data from our randomized trial suggest that 77% of patients search for health information online. Providers’ perceptions of patients’ online habits may influence whether that provider thinks the portal is useful for their patients. Factors that may influence how providers perceive their patients’ online habits include not only the patient’s age, but also his or her socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, and preferred language. Future research should explore how these factors impact providers’ interactions with acute care portals and the patients who use them.

Only 44% of providers recalled caring for a patient who used the acute care portal. One possible explanation is that providers did not always notice when their patients used the portal. If true, this may mitigate the concern that greater transparency of health information for hospitalized patients will antagonize providers and negatively impact care.

Provider’s slight disagreement with the statement “the acute care patient portal makes it easier for my patients to contact me” highlights the challenge of integration with the EHR. In this case, patient-entered comments or pain levels from the portal may not have been easily accessible or obvious in the EHR. Furthermore, none of the providers surveyed recalled any patients who reported inaccurate information in the portal. However, 24 (17%) portal users reported finding inaccurate information, and 7 (6%) reported that they communicated it to a provider. Both providers’ lack of recall and patients’ lack of communication highlight the need for better mechanisms that allow patients to report inaccurate information. For example, better visibility of patient-entered comments in the EHR may improve communication. Future research should explore strategies for patients to contribute to their health record and improve its quality.

Overall, providers expressed more positivity about the acute care portal than our research team expected given previous surveys.11,20,23-28 In this survey, every provider reported that displaying laboratory test results in the portal was moderately useful or very useful. In contrast, previous surveys found that providers expressed concerns about displaying test results.20,23 Before the trial, about 40% of providers working on the trial units worried that displaying test results electronically might increase their workload, cause anxiety, or increase liability.20 After the trial, provider’s hesitation about sharing test results appeared to decrease. The decreased hesitation about displaying tests results may indicate that the provider’s initial concerns did not transpire. This is consistent with previous research suggesting that displaying test results did not impact the clinical workflow despite provider’s initial reluctance to include them.8

Providers ranked the portal’s features as very useful significantly less often than patients (57% vs. 74%; p<0.001). In particular, providers underestimated the value patients placed on communication features such as entering comments or recording pain levels. Previous studies have similarly reported that patients value communication features highly.10-12 One possible reason is that communication features place more burden on providers than information display features. This explanation is consistent with previous research suggesting that providers value features that provide the greatest benefit to patients with the least additional work for themselves.11

Limitations

We conducted our study at a large academic medical center with an advanced informatics infrastructure, which may limit its generalizability. We did not collected any unstructured data, which could have provided additional insight. This study assessed providers’ perceptions of an acute care portal used on two medical and surgical step-down units, and results may not generalize to other inpatient settings. Our acute care portal only included health information display and basic communication features. providers’ perceptions of portals with different features, such as secure messaging or scheduling, may differ.

Conclusion

We surveyed healthcare providers to assess their perceptions of an acute care patient portal used during a randomized trial. Providers found the portal usable, useful, and trustworthy, and reported a positive impact on care delivery. Providers underestimated the usefulness of portal features to patients. Our results suggest that the implementation of acute care patient portals will not adversely impact providers.

Funding

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS21816, PI: Vawdrey).

References

- 1.American Hospital Association. Individuals’ Ability to Electronically Access Their Hospital Medical Records, Perform Key Tasks is Growing [Internet] 2016. [cited 2017 Feb 8]. Available from: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/16jul-tw-healthIT.pdf.

- 2.Collins SA, Vawdrey DK, Kukafka R, Kuperman GJ. Policies for patient access to clinical data via PHRs: current state and recommendations. J Am Med Informatics Assoc [Internet] 2011 Dec 1;18(Supplement 1):i2–7. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000400. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3241176&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prey JE, Woollen J, Wilcox L, Sackeim AD, Hripcsak G, Bakken S, et al. Patient engagement in the inpatient setting: a systematic review. J Am Med Informatics Assoc [Internet] 2014 Jul 1;21(4):742–50. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002141. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jamia/article-lookup/doi/10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitton A, Poku M, Bates D. Policy context and considerations for patient engagement with health information technology. In: Grando M, Rozenblum R, Bates D, editors. Information Technology for Patient Empowerment in Healthcare. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter Inc; 2015. pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- 5.2014 Edition EHR Certification Criteria Grid Mapped to Meaningful Use Stage 2 [Internet] Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/2014editionehrcertificationcriteria_mustage2.pdf.

- 6.Masterson Creber R, Prey J, Ryan B, Alarcon I, Qian M, Bakken S, et al. Engaging hospitalized patients in clinical care: Study protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials [Internet] 2016 Mar;47:165–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.01.005. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dykes PC, Rozenblum R, Dalal A, Massaro A, Chang F, Clements M, et al. Prospective Evaluation of a Multifaceted Intervention to Improve Outcomes in Intensive Care. Crit Care Med [Internet] 2017;3:1. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002449. Available from: http://insights.ovid.com/crossref?an=00003246-900000000-96602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Runaas L, Hanauer D, Maher M, Bischoff E, Fauer A, Hoang T, et al. BMT Roadmap: A User-Centered Design Health Information Technology Tool to Promote Patient-Centered Care in Pediatric Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant [Internet] 2017;23(5):813–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.01.080. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Leary KJ, Lohman ME, Culver E, Killarney A, Smith GR, Liebovitz DM. The effect of tablet computers with a mobile patient portal application on hospitalized patients’ knowledge and activation. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2015;23(1):159–65. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grossman L V, Choi SW, Collins S, Dykes PC, O’Leary KJ, Rizer M, et al. Implementation of acute care patient portals: recommendations on utility and use from six early adopters. J Am Med Inform Assoc [Internet]. 2017 Sep 4;1:8550–8550. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx074. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20800578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caligtan CA, Carroll DL, Hurley AC, Gersh-Zaremski R, Dykes PC. Bedside information technology to support patient-centered care. Int J Med Inform [Internet] 2012;81(7):442–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.12.005. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalal AK, Dykes PC, Collins S, Lehmann LS, Ohashi K, Rozenblum R, et al. A web-based, patient-centered toolkit to engage patients and caregivers in the acute care setting: A preliminary evaluation. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2016;23(1):80–7. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stade D, Dykes P. Nursing Leadership in Development and Implementation of a Patient-Centered Plan of Care Toolkit in the Acute Care Setting. CIN Comput Informatics, Nurs [Internet] 2015 Mar;33(3):90–2. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000149. Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00024665-201503000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maher M, Hanauer DA, Kaziunas E, Ackerman MS, Derry H, Forringer R, et al. A Novel Health Information Technology Communication System to Increase Caregiver Activation in the Context of Hospital-Based Pediatric Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Pilot Study. JMIR Res Protoc [Internet] 2015;4(4):e119. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4918. Available from: http://www.researchprotocols.org/2015/4/e119/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maher M, Kaziunas E, Ackerman M, Derry H, Forringer R, Miller K, et al. User-Centered Design Groups to Engage Patients and Caregivers with a Personalized Health Information Technology Tool. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant [Internet] 2016 Feb;22(2):349–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.08.032. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1083879115005935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dykes PC, Carroll DL, Hurley AC, Benoit A, Chang F, Pozzar R, et al. Building and testing a patient-centric electronic bedside communication center. J Gerontol Nurs [Internet] 2013;39(1):15–9. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20121204-03. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23244060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couture B, Cleveland J, Ergai A, Katsulis Z, Ichihara N, Goodwin A, et al. User-Centered Design of theMySafeCare Patient Facing Application. CIN Comput Informatics, Nurs [Internet] 2015 Jun;33(6):225–6. Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00024665-201506000-00001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohashi K, Dykes PC, Stade DL, Chen E, Massaro AF, Bates DW, et al. 2014. An Electronic Patient Safety Checklist Tool for Interprofessional Healthcare Teams and Patients. In: AMIA 2014 Annual Symposium. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilcox L, Woollen J, Prey J, Restaino S, Bakken S, Feiner S, et al. Interactive tools for inpatient medication tracking: A multi-phase study with cardiothoracic surgery patients. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2016;23(1):144–58. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prey JE, Restaino S, Vawdrey DK. Providing hospital patients with access to their medical records. AMIA. Annu Symp proceedings AMIA Symp [Internet] 2014;2014:1884–93. Available from: http://search.proquest.com/docview/1680181359?accountid=14732%5Cnhttp://bd9jx6as9l.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&rfr_id=info:sid/ProQ:medlineshell&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journal&rft.genre=article&rft. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vawdrey DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, Bakken S, Feiner S, Boyer A, et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA . Annu Symp proceedings AMIA Symp [Internet] 2011;2011:1428–35. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22195206%5Cnhttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC3243172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly MM, Hoonakker PLT, Dean SM. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2017;24(1):153–61. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilcox LG, Gatewood J, Morris D, Tan DS, Feiner S, Horvitz E. Physician Attitudes about Patient-Facing Information Displays at an Urban Emergency Department. AMIA Annu Symp Proc [Internet] 2010;2010:887–91. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3041441/%5Cnhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3041441/pdf/amia-2010_sympproc_0887.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dykes PC, Stade D, Chang F, Dalal A, Getty G, Kandala R, et al. Participatory Design and Development of a Patient-centered Toolkit to Engage Hospitalized Patients and Care Partners in their Plan of Care. AMIA . Annu Symp proceedings AMIA Symp [Internet] 2014;2014:486–95. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25954353%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4419925. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins SA, Gazarian P, Stade D, McNally K, Morrison C, Ohashi K, et al. Clinical Workflow Observations to Identify Opportunities for Nurse, Physicians and Patients to Share a Patient-centered Plan of Care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc [Internet] 2014;2014:414–23. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25954345%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4419989. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilcox L, Feiner S, Liu A, Restaino S, Collins S, Vawdrey D. Designing inpatient technology to meet the medication information needs of cardiology patients. In: Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGHIT symposium on International health informatics - IHI ’12 [Internet] 2012. p. 831. Available from: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2110363.2110466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Collins SA, Rozenblum R, Leung WY, Morrison CR, Stade DL, McNally K, et al. Acute care patient portals: a qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives on current practices. J Am Med Informatics Assoc [Internet] 2016. Jun 29, p. ocw081. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jamia/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/jamia/ocw081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.O’Leary KJ, Sharma RK, Killarney A, O’Hara LS, Lohman ME, Culver E, et al. patients’ and healthcare providers’ perceptions of a mobile portal application for hospitalized patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak [Internet] 2016;16(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0363-7. Available from: http://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12911-016-0363-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hefner JL, Sieck CJ, Walker DM, Huerta TR, McAlearney AS. System-Wide Inpatient Portal Implementation: Survey of Health Care Team Perceptions. JMIR Med Informatics [Internet] 2017;5(3):e31. doi: 10.2196/medinform.7707. Available from: http://medinform.jmir.org/2017/3/e31/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilcox L, Morris D, Tan D, Gatewood J. Designing patient-centric information displays for hospitals. Proc 28th Int Conf Hum factors Comput Syst - CHI ’10 [Internet]; 2010. p. 2123. Available from: http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=1753326.1753650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakken S, Grullon-Figueroa L, Izquierdo R, Lee N, Morin P, Palmas W, et al. Development, validation and use of english and spanish versions of the telemedicine satifaction and usefullness questionnaire. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2006;13(6):660–7. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benjamin DJ, Berger JO, Johannesson M, Nosek BA, Wagenmakers E-J, Berk R, et al. Redefine statistical significance. Nat Hum Behav [Internet] 2017. (January) pp. 6–10. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-017-0189-z. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Dalal AK, Dykes P, Mcnally K, Stade D, Ohashi K, Collins S, et al. Washington, DC: 2014. Engaging Patients, Providers, and Institutional Stakeholders in Developing a Patient-centered Microblog. In: AMIA 2014 Annual Symposium. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pew Research Center. 2018 Mobile Fact Sheet [Internet] 2018. [cited 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/

- 35.Pew Research Center. Older Adults and Technology Use [Internet] 2018. [cited 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/04/03/older-adults-and-technology-use/

- 36.Ancker JS, Nosal S, Hauser D, Way C, Calman N. Access policy and the digital divide in patient access to medical records. Heal Policy Technol [Internet] 2017;6(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2016.11.004. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]