Abstract

As the quantity and detail of association studies between clinical phenotypes and genotypes grows, there is a push to make summary statistics widely available. Genome wide summary statistics have been shown to be vulnerable to the inference of a targeted individual's presence. In this paper, we show that presence attacks are feasible with phenome wide summary statistics as well. We use data from three healthcare organizations and an online resource that publishes summary statistics. We introduce a novel attack that achieves over 80% recall and precision within a population of 16,346, where 8,173 individuals are targets. However, the feasibility of the attack is dependent on the attacker's knowledge about 1) the targeted individual and 2) the reference dataset. Within a population of over 2 million, where 8,173 individuals are targets, our attack achieves 31% recall and 17% precision. As a result, it is plausible that sharing of phenomic summary statistics may be accomplished with an acceptable level of privacy risk.

1. Introduction

Decreasing costs in high throughput sequencing technologies, in combination with the increasing detail of electronic health records data, has led to rapid growth in the number of association studies between clinical phenotypes and genotypes1. At the same time, there is an increasing push to make information about such studies available on a broad scale for secondary uses. This movement is driven by a variety of factors, including open data initiatives2, but also formal policy promulgated by extramural funding agencies, such as the Genome Data Sharing policy of the National Institutes of Health3. Along these lines, there is evidence to suggest that the reuse of data can enable transparency, validation of findings, and support novel investigations4. Certain initiatives, such as the Personal Genome Project, aim to make individual-level data accessible to potential users5. However, not all participants in research studies are comfortable with such detailed information being handed over to the public over concerns that they will be reidentified7. Thus, to protect the privacy of the participants, various programs aim to release summary statistics about certain factors about the participants in the study only. Often, these factors correspond to the rates at which certain genomic variables, such as specific alleles, were observed in the study, or in subpopulations of the study (e.g., a Caucasian or African American race).

Yet, it has been shown that sharing summary statistics can still lead to privacy concerns6. Specifically, it was discovered that if someone has access to allele frequencies for 1) the study pool, 2) some reference population, and 3) the genomic variants of a targeted individual, then, under the right conditions, it can be predicted with some certainty if the target is the member of the pool. This attack is executed by comparing the similarity of the target individual’s alleles to the rates at which such alleles manifest in the pool and reference (which serves as an indication of a random background of individuals from which the biased pool could have been selected), such that when the target is sufficiently similar to the pool, their membership may be disclosed. This attack, which was first posited by Homer and colleagues8, was so surprising and successful that it prompted the NIH, as well as the Welcome Trust, to remove all genomic summary statistics from the public domain9. Over time, the NIH has reconsidered this position and recently solicited public comments on how best to make such summary statistics more widely available again10. However, as the NIH has deliberated on next steps with respect to the public dissemination of summary statistics, other programs have pushed forward, such as the Exome Aggregation Consortium (EXaC)1, which has created an online browser for data on over 60,000 individuals11, and the Sequence and Phenotype Integration Exchange (SPHINX)2, a web-based tool for exploring data associated with the drug response implications of genetic variation across the pharmacogenetics cohort of the Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) consortium12. As these resources have been brought online, so too have solutions for mitigating the likelihood of success of the presence detection through genomic summary data problem13-15.

While association studies have evolved to perform genome-wide scans, they have evolved to incorporate phenome- wide scans16,17. This is notable because it expands the scope of data sharing, as well as the privacy attack surface. In this respect, one must question the extent to which making summary phenome statistics available allow for presence detection attacks as well. To investigate this question, in this paper, we use a targeted individual’s phenotype information and statistical summary data about a given dataset to detect if the targeted individual is in the dataset or not. We collect data from SPHINX, Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), Northwestern University (NW) and Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPW) to perform this analysis. Specifically, we use SPHINX as the pool dataset, and the other three datasets as references. Based on these datasets, we performed a systematic series of controlled experiments to assess the risk of phenotypic membership detection. We show that this attack is possible and can achieve a relatively accurate result (over 80% precision and recall) under certain conditions. However, at the same time, we find that the strength of this attack can be controlled and is likely mitigated by natural phenomena. In particular, this is because the attack is dependent upon the adversary’s knowledge about the target and reference dataset. And, as we illustrate, the attack weakens as we limit the amount of phenotypic information available to the adversary, as well as when the size of the reference dataset grows. A particularly notable finding is that when the number of phenotypic features available to the attacker is no greater than 6 (a plausible number of features available to an adversary18), the recall and precision of this attack is below 13%.

2. Related Research

Over time, there have been a variety of attacks perpetrated against de-identified medical and genomic data that have indicated the potential for privacy violations. Generally speaking, there are different classes of privacy attacks that have been realized, two of which are worth noting for context. The first type of attack6 corresponds to identity disclosure. In this attack, the adversary aims to infer a person’s identity (e.g., personal name) from de-identified records. One common technique employed in such an attack is linkage, where a de-identified record is related to some identified clinical records through features they commonly share, often referred to as quasi-identifiers23,24. This style of attack has been applied to exploit uniqueness in genomic sequences19, but also the combination of an individual’s demographics20, sets of health care facilities they visited21, laboratory test results they received22, and diagnoses they were billed for24. It should be recognized, however, a linkage attack requires datasets to be disclosed in a manner that reveal individual-level data.

The second type of attack corresponds to membership detection. In this attack, summary statistics are invoked to detect a known person’s existence in the given dataset. The idea behind this attack is to measure how similar the individual’s data is to the statistics of the attacked dataset. In this scenario, the similarity measure varies according to the data that is available. For instance, in the seminal work of Homer and colleagues, they measure the similarity in terms of the rate at which minor alleles are realized8. In the work of Gymrek and colleagues, the similarity measure relies on the distance in terms of short tandem repeats (STRs) on the Y chromosome25. By contrast, the attack postulated by Sankararaman and colleagues14 relies less on a similarity measure and more on a probabilistic model, which specifically corresponds to a likelihood ratio test based on if a targeted individual is more likely to be in, than out, of a study pool. Bustamante and colleagues28 demonstrate a similar membership detection attack, which was applied to the Beacon platform of the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health, based on a likelihood ratio test that needs only the genomic presence data. Countermeasures for this attack, such as systematically hiding parts of the genome have been proposed29,30. Wan and colleagues13 demonstrate a way to find the optimal strategy to mitigate the privacy risk of such a membership detection attack based on game theoretic analyses using real world datasets include SPHINX and 1000Genomes.

To date, the membership attack has focused on genomic data only. In this paper, we propose a new perspective of the membership attack, whereby we use a targeted individual’s phenotypic information to detect their membership in a dataset. This attack diverges from previous investigations in several notable ways. First, phenotypic and genomic data are different both in terms of quality and quantity. While a person harbors on the order of 10 million basic genomic variants (e.g., single nucleotide polymorphisms or short tandem repeats), the typical structured phenomic information drawn from the clinical domain corresponds to no more than 1000 possible variants (and often orders of magnitude less). Second, we add controls to the feature space, such that we test what happens when the attacker only has partial knowledge about the targeted individual, which is a more likely occurrence in the phenotypic than genotypic scenario18. Third, we perform our analysis using several different datasets to create a generalizable result, which is atypical in investigations that focused on genomic data in prior studies.

3. Materials & Methods

3.1. Materials

3.1.1. eMERGE-PGx dataset

The eMERGE-Pharmacogenetics (PGx)27 dataset contains the genetic sequencing and phenotype data (demographics, medications, and ICD-9, PheWAS codes and CPT codes) of 8,173 subjects. These subjects are from 9 different eMERGE-PGx sites: Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), Cincinnati Childrens Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), Geisinger Health System (GHS), Kaiser Permanente Washington with University of Washington (KPW), Marshfield Clinic, Mayo Clinic, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Northwestern University (NW), and Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC). In particular, this dataset provides the individual records of each subject. In each record, a list of phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) codes is generated from the subject’s phenotypic information16. A complete PheWAS code has 5 digits including the root code (i.e., the first 3 digits) and child code (i.e., the last 2 digits). Some of the PheWAS codes in the dataset only contained the root code, while others contained the root and child codes. For consistency, we rolled up every 5 digit code to its 3 digit form. For example, after the roll-up, a subject with PheWAS codes 008.51, 008.52, and 008.60 will be represented by a single code: 008. A total number of 579 PheWAS root codes appeared in the dataset at least once. The prevalence of each 3-digit PheWAS code was computed based on the individual level records. Here, prevalence is defined as the proportion of patients that were assigned the code. After preprocessing, the data consisted of the prevalence of 579 PheWAS codes.

3.1.2. VUMC SD Dataset

The VUMC Synthetic Derivative (SD) dataset contains de-identified individual level records of over 2 million subjects31. These subjects are the set of patients that received any medical care at VUMC. 11.0% of the participants in eMERGE-PGx are sampled from the VUMC. For each subject, this dataset contains a list of ICD-9 codes derived from the electronic medical record. The SD is a set of records that is no longer linked to the identified medical record from which it is derived and has been altered to the point it no longer closely resembles the original record. We map each ICD9 codes to a 3 digit PheWAS code and compute the prevalence of each PheWAS code in the VUMC SD population. After preprocessing, we obtained the prevalence of 564 PheWAS codes and the individual-level data of 2,155,348 subjects.

3.1.3. KPW and NW Datasets

The KPW and NW datasets contain the aggregated statistics of ICD-9 codes of 2,446,230 patients that received care from KPW and 1,602,402 patients Northwestern University Memorial Hospital. 12.1% and 8.9% of participants in eMERGE-PGx are sampled from KPW and NW respectively. For this study, we rely on the counts of patients who received each ICD-9 code. Based on the ICD-9 PheWAS mapping, we compute the count of each 3-digit PheWAS code as the sum of the count of each ICD-9 code that is mapped to the PheWAS code. This preprocessing provided the prevalence of 452 PheWAS codes for subjects from KPW, as well as NW. Table 1 provides a summary of the datasets.

Table 1:

A summary of the datasets studied in this investigation.

| Dataset | Population | Num. PheWAS Codes | Summary Statistics | Individual-level Records | Sample Proportion in eMERGE-PGx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eMERGE-PGx | 8,173 | 579 | Yes | Yes | - |

| VUMC SD | 2,155,348 | 564 | Yes | Yes | 11.0% |

| KPW | 2,446,230 | 452 | Yes | No | 12.1% |

| NW | 1,602,402 | 452 | Yes | No | 8.9% |

3.2. Membership Detection based on Likelihood Ratio (LR) test

Based on this data, we now provide intuition into the attack. Given the set of PheWAS codes a subject has been assigned, along with the prevalence of PheWAS codes in the pool and the reference, we can make a prediction about if the target is in the pool (or reference) based on a likelihood ratio (LR) test. Formally, we represent each individual as a set of PheWAS codes in a binary vector , where xi = 1 if the subject has the ith PheWAS code and 0 otherwise. We then compute the LR score as:

where P(x|pool) and P(x|ref) is the probability that a subject x is in the pool and reference, respectively, given their PheWAS codes prevalences.

We represent the prevalence of the ith PheWAS code in the pool and reference as P(pool, i) and P(ref, i), respectively. We can derive P(x|pool) and P(x|ref), where:

And, we can represent the LR score in terms of P(pool, i) and P(ref, i):

Now, given a predefined threshold θ, we predict that the subject is in the pool if their LR score is above the threshold. Otherwise, we predict that the individual is in the reference.

3.3. Performance measures

We use standard measures to measure the performance of the attack. Recall is the fraction of correctly predicted pool subjects over the size of the pool. It measures the completeness of our prediction. Precision is the fraction of correctly predicted pool subjects over all subjects we predicted as in the pool. It measures the relevance of our prediction. Accuracy is the fraction of all the correctly predicted subjects over all subjects in the pool and reference. It measures the prediction accuracy for both the pool and the reference. In this attack, since we care more about the subjects’ presence in the pool, but not the reference, accuracy is not as important of a measure as others in practice, but we report it for completeness. The F1 score is the harmonic average of the precision and recall and is the primary privacy measure employed by our experiments. Let TP be the number of correctly predicted pool subjects, FP be the number of subjects predicted in the pool by mistake, TN be the number of correctly predicted reference subjects, P be the size of pool and N be the size of reference shown in, then , , and .

4. Experiments & Results

To perform our experiments, we set the eMERGE-PGx dataset as the pool and use VUMC SD, KPW and NW as the reference populations.

4.1. eMERGE-PGx vs VUMC SD

We first investigated the extent to which a targeted individual can be detected in the eMERGE-PGx pool of 8,173 individuals. To perform this analysis, we randomly sampled a subset of subjects from the VUMC SD to form the reference set. We simulated scenarios with three different ratios of the pool and reference sample size: 1:1, 1:25, 1:250. As such, the reference set sizes for each scenario is 8,173, 204,325, and 2,155,348 (all subjects in VUMC SD). The details of the experimental setup are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Design of the experiments that assess the influence of the prior probability of a targeted individual being in the pool.

| Scenario | Pool Size | Reference Size | Proportion (pool:reference) |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | 8,173 | 8,173 | 1:1 |

| b | 8,173 | 204,325 | 1:25 |

| c | 8,173 | 2,155,348 (all subjects in the reference) | 1:250 |

In each setting, for each subject in the union of the pool and the reference, we compute the LR test score. We make one of two claims based on the score: i) the subject is in the pool or ii) the subject is in the reference. We say that a FP occurs when we claim the subject is in the pool, but they were really in the reference. We repeated the experiment 10 times, each time randomly sampling a portion of records from VUMC SD. The average precision, recall and accuracy of the 10 runs at 20 different threshold levels are shown in Figure 1. For every threshold θ, we compute the variance of recall and precision at 10 runs, and report the average variance of recall and precision. For Figure 1.a, the average variance of recall is 4 × 10–6, the average variance of precision is 2 × 10–5. For Figure 1.b, the average variance of recall is 1 × 10–7, the average variance of precision is 1 × 10–3. These results imply that average performance of our attack is highly stable in the context of these experiments.

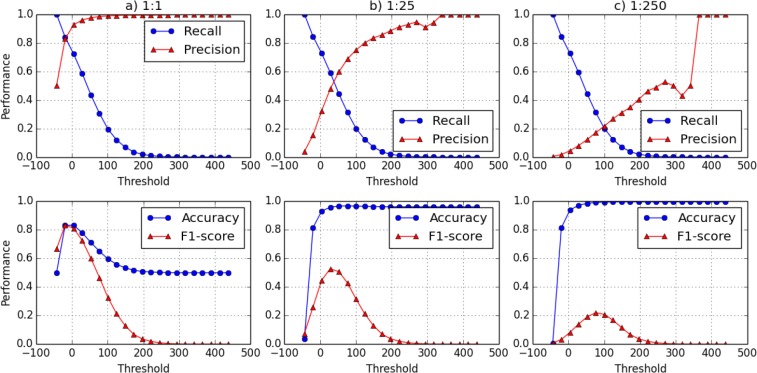

Figure 1:

The performance of the phenotypic presence detection attack as a function of threshold θ with different pool:reference sample proportion. The proportion decreases from left to right. Recall and Precision are shown in the first row and Accuracy and F1 are shown in the second row.

There are several notable findings that are illustrated in Figure 1. First, it can be seen that the most successful attack setting is realized when the pool and reference are of equal size, as shown in Figure 1.a. In this case, the recall, precision, and F1 score are all maximized when the threshold is θ = –20 (recall = 0.839; precision = 0.828; F1 = 0.833). This means that, at this threshold, we correctly detected the presence of more than 80% of the subjects with a false positive rate of approximately 18%.

Second, as shown in Figures 1.a and 1.b, it can be seen that the precision changes significantly with changes in the pool to reference proportion. In particular, as the size of the reference grows, the initial precision value drops from 0.5 to 0.04 and eventually falls to 0.004. This is due to the change in the prior probability that a target is in the pool. When the attacker chooses the lowest threshold (θ ≈ –50), they will predict every subject as a member of the pool because every record has a score that is greater or equal to the lowest score. It can be seen that, as the ratio changes from 1:1, 1:25 to 1:250, the prior probability of being in the pool decreases and, as a result, the attack performance at the lowest threshold worsens. Moreover, we can see that the shape of the precision rate (as a function of the proportion) changes as well. Specifically, it shifts from a concave to a convex function. This happens because, as we increase the size of reference, more subjects in the reference appear to be similar to those in the pool. As the number of false positives grows, the precision decreases. Eventually, when the threshold is raised to a sufficiently high level, the precision becomes 1, which occurs at the point when only a few true positive samples remain.

Third, the F1 score decreases as we increase the size of reference. This is expected because the precision is decreasing. However, it should be recognized that the decrease in the precision and the increase in the size of the reference population are not changing at the same rate. As we increase the population size from 8,000 to 2.2 million people, the highest F1 score drops by 75% of its initial value. We further recognize that as the size of reference increases, the threshold for the best overall performance (i.e., the highest F1 score) increases as well. This is an artifact of the decrease in precision. This observation suggests that, when the size of the reference population is large, the adversary should rely upon a larger threshold value.

Fourth, as can be seen in Figure 1.b and Figure 1.c, the precision has a small gap at θ around 300. This happened because of the large size of the reference population (i.e., 2.2 million people). In this case, the probability that it contains several subjects that look like they came from the pool is relatively high. As a result, these subjects remain in the predicted pool until θ is sufficiently large, which occurs when θ is approximately 300. This probability reduces as the reference population becomes smaller. By comparing Figures 1.b and 1.c, it can be seen that the red line (which corresponds to the precision) in 1.b is much smoother than the one in 1.c.

In summary, the findings from this experiment indicate that, as we increase the size of the reference population, the power of the attack decreases. This is primarily due to the fact that the prior probability of a target being in the pool will decrease. Notably, this finding is in alignment with the findings of Heatherly and colleagues26, which indicated that a larger population can offer better privacy protection than a smaller one.

4.2. eMERGE-PGx vs KPW and eMERGE-PGx vs NW

Next, we conducted a similar set of experiments with the three reference datasets based on summary statistics: eMERGE-PGx vs. KPW, eMERGE-PGx vs. NW, and eMERGE-PGx vs. VUMC SD. In these experiments, we set eMERGE-PGx as the pool. For the purpose of generalizability, we randomly generate a set of subjects, with Phe-WAS codes. We represent these as , where xi = 1 is the ith PheWAS code in the record. We assume that each xi is independently randomly distributed and P(xi = 1) is the prevalence of the PheWAS code in the dataset. For each dataset, we generate 204,325 subjects, such that the proportion between the pool and reference is 1:25.

We compute the LR test score for the union of all the subjects in eMERGE-PGx and the simulated datasets. To mitigate the impact of the randomness, we generated 10 random datasets of a given size for each reference. The average precision, recall, accuracy and F1 score are shown for the VUMC SD, KPW and NW reference datasets in Figures 2.a, 2.b, and 2.c, respectively. All of the variances for the recall and precision for three experiments are smaller than 1 × 10–6. Again, this result implies that the average performance from the experiments is likely to be stable.

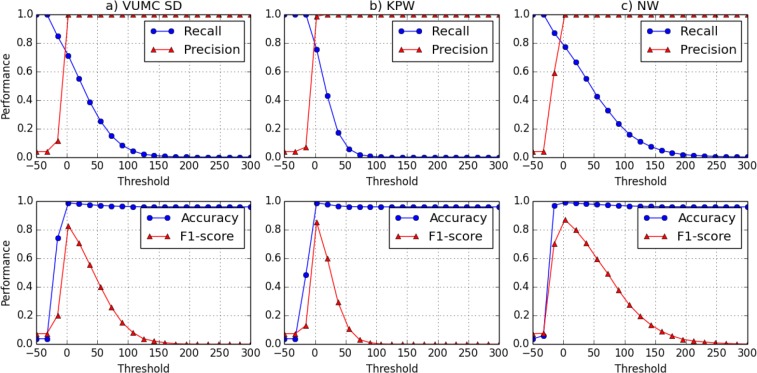

Figure 2:

The performance of the attack as a function of the threshold θ with three different reference populations. From left to right, three reference populations are VUMC SD, KPW and NW. Recall and Precision are shown in the first row and Accuracy and F1 are shown in the second row.

It can be seen that NW has the highest F1 score (0.87), followed by KPW (0.85), and then VUMC SD (0.83). The difference in the three highest F1 scores is not that large. However, we note that this might be an artifact of using simulated data in these experiments.

4.3. eMERGE-PGx vs VUMC SD using a Subset of PheWAS Codes

The previous experiments are based on the assumption that the adversary knows the presence and absence of all the PheWAS codes for all the subjects. Thus, in this experiment, we assessed the performance of the LR test in a scenario when the adversary’s knowledge is limited to only a subset of the PheWAS codes for a targeted individual. This is a more realistic scenario because it is unlikely that an attacker will know everything about everyone18. In this experiment, we use eMERGE-PGx as the pool and all subjects from the VUMC SD as the reference. We conducted two sets of experiments. The first experiment relies on 5 PheWAS codes, the second experiment relies on 55 PheWAS codes. We compare these results with the earlier experiment that permitted the adversary to leverage all 557 PheWAS codes.

We performed 10 runs for each experiment. In each run, we used a set of randomly selected PheWAS code to compute the LR test score. The average results for the runs are depicted in Figure 3. For Figure 3.b, where the adversary has 55 PheWAS codes, the average variance of recall is 7 × 10–4, and the average variance of precision is 0.019 . For Figure 3.c, where the adversary has 5 PheWAS codes, the average variance of recall is 0.018, and the average variance of precision is 0.026. It can be seen that as the number of features decreases, the range of the LR score decreases as well. Specifically, the range for the threshold shrinks from [-100, 500] to [-5, 15].

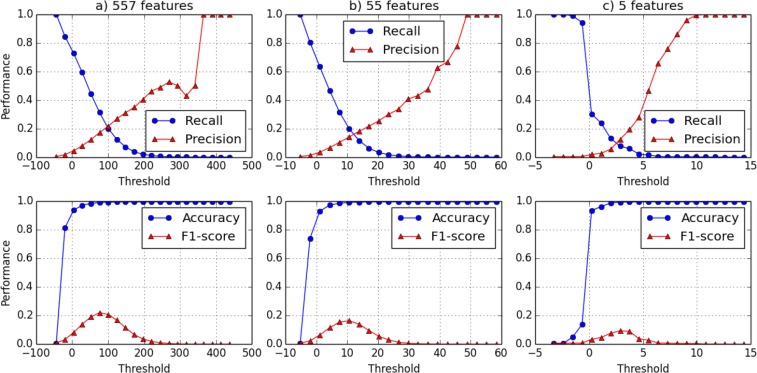

Figure 3:

The performance of the attack as a function of threshold θ and the number of phenotypic features available to the adversary. The number of PheWAS codes used in each experiment decreases from left to right. Recall and Precision are shown in the first row and Accuracy and F1 are shown in the second row.

These results indicate that, as the number of features decreases, the precision, recall and the F1 also decrease. When the adversary has 55 PheWAS codes, they can achieve a 19.8% recall and 14.1% precision, with a maximum F1 score of 16.5%. However, when the adversary only has access to 5 features, the maximum F1 score is 9.4%, with 7.6% recall and 12.4% precision. This suggests that when the attacker has limited knowledge about the targeted individual, detecting their membership in the pool becomes much more difficult. While 10% predictive power may seem large, this suggests that the adversary’s success is, on average, similar to the risk tolerance often recommended by federal agencies and other various policies in practice18. This is notable because it further suggests that amendment to the summary statistics may not be necessary to make the data publicly accessible.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we introduced an algorithmic approach to detect an individual’s membership in a study based on summary phenotype statistics. We showed that this attack is plausible using multiple reference populations. We further showed that if an adversary has complete knowledge about a targeted individual’s phenotype, they can achieve relatively high performance (over 80% precision and recall). At the same time, we also observed that the result is not robust. Specifically, the performance of the attack is sensitive to an adversary’s knowledge about a targeted individual’s phenotypic information and the reference dataset. In particular, as the number of phenotypic facts known to the adversary decreases and as the prior probability that a targeted individual is in the study pool decreases, the power of this attack diminishes and may be sufficiently low to support the dissemination of summary phenotypic information without amendment. However, we wish to stress that this suggestion is based on the expectation that the adversary is limited in their knowledge. In the event that the adversary is not limited, or the organization planning to share data has no intuition into the capabilities of the adversary, then additional safeguards may be needed. For instance, it may be more prudent for the organization to require users of the resource to enter into a data use agreements, suppress certain phenotypic variables that are driving the disparity between the pool and the reference, or some combination of the two (a strategy that has shown feasible for the dissemination of genomic summary data13,32).

Despite the findings of this study, there are limitations to this investigation we wish to highlight, as we believe they provide opportunities for improvement and extension. First, we assumed that the prevalence of each PheWAS code is independent of other codes. However, this is unlikely to be the case in practice, such that the LR test employed by the attacker may not be as accurate as suggested. Second, in this investigation, if a targeted individual lacked an indication of a certain diagnosis, we assumed they did not have it. Yet, in reality, a lack of a diagnosis may not be definitive, such that the model may need to focus only on positively documented diagnoses and neglect those that fail to be indicated. Third, in the standard LR test setting, the pool should be a part of the reference set (i.e., it is anticipated that the pool is a biased selection from the reference population). But in the data we collected, eMERGE-PGx is not a subset of others. However, the magnitude of eMERGE-PGx is relatively small (only 0.4% of all patients who visited the VUMC), such that it is safe to assume that the affiliation between the pool and reference will have minimal impact on the result of this investigation. Fourth, for each experiment, we cycle over an entire range of all LR scores to find the best threshold. In practice, the attacker is unaware of which threshold is the best one. This will reduce the feasibility of the attack.

Though there are limitations to this study and ways by which the attack could be refined, we believe that this study makes it evident that there is a potential for the recognition of an individual in a study based on their phenotypic characteristics. Still, it should be noted that this analysis makes an assumption that an adversary has (or is able to gather) the knowledge necessary to perpetrate this attack. In the event that data is to be made public, then it is possible that adversaries may be able to satisfy this criterion. When this criterion is not satisfiable (e.g., if the organization managing the resource can verify that the recipient of the data is unable to obtain such knowledge), then the performance of the attack reported in this paper should be considered an upper bound and the actual risk may be substantially lower than what we have reported.

Acknowledgements

This research was sponsored, in part, by grants R01HG006844, U01HG006385, U01HG006378, and RM1HG009034 (the Center for Genetic Privacy and Identity in Community Settings) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Bowton E, Field JR, Wang S, et al. Biobanks and electronic medical records: enabling cost-effective research. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(234):234cm3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manolio TA, Fowler DM, Starita LM, et al. Bedside back to bench: building bridges between basic and clinical genomic research. Cell. 2017;169(1):6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institutes of Health. 2014. Aug 27, NIH genomic data sharing policy. NOT-OD-14-124. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paltoo DN, Rodriguea LL, Feolo M, et al. Data use under the NIH GWAS data sharing policy and future directions. Nat Genet. 2014;46(9):934–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball MP, Bobe JR, Chou MF, et al. Harvard Personal Genome Project: lessons from participatory public research. Genome Med. 2014;6(2):10. doi: 10.1186/gm527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naveed M, Ayday E, Clayton EW,an, et al. Privacy in the genomic era. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2015 Sep 29;48(1):6. doi: 10.1145/2767007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hull SC, Sharp RR, Botkin JR, et al. Patients’ views on identifiability of samples and informed consent for genetic research. Am J Bioeth. 2008;8(10):62–70. doi: 10.1080/15265160802478404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Homer N, Szelinger S, Redman M, Duggan D, Tembe W, Muehling J, Pearson JV, Stephan DA, Nelson SF, Craig DW. Resolving individuals contributing trace amounts of DNA to highly complex mixtures using high-density SNP genotyping microarrays. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000167. e1000167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zerhouni EA, Nabel EG. Protecting aggregate genomic data. Science. 2008;322(5898):322. doi: 10.1126/science.322.5898.44b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institutes of Health. 2017. Sep 20, Request for comments: proposal to update data management of genomic summary results under the NIH genomic data sharing policy. NOT-OD-17-110. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karczewski KJ, Weisburd B, Thomas B, et al. The ExAC browser: displaying reference data information from over 60 000 exomes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45(D1):D840–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottesman O, Kuivaniemi H, Tromp G, et al. The Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network: past, present, and future. Genet Med. 2013;15(10):761–71. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wan Z, Vorobeychik Y, Xia W, et al. Expanding access to large-scale genomic data while promoting privacy: a game theoretic approach. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100(2):316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sankararaman S, Obozinski G, Jordan MI, Halperin E. Genomic privacy and limits of individual detection in a pool. Nat Gen. 2009;41(9):965–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig D, Goor RM, Wang Z, et al. Assessing and managing risk when sharing aggregate genetic variant data. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:730–6. doi: 10.1038/nrg3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denny JC, Ritchie M, Basford MA, et al. PheWAS: demonstrating the feasibility of a phenome-wide scan to discover genedisease associations. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(9):1205–10. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X, Meng X, Spiliopoulou A, et al. 2018. Feb, MR-PheWAS: exploring the causal effect of SUA level on multiple disease outcomes by using genetic instruments in UK Biobank. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 6:annrheumdis-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Emam K, Rodger S, Malin B. Anonymising and sharing individual patient data. BMJ. 2015;350:h1139. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin Z, Owen AB, Altman R. Genetics: genomic research and the human subject privacy. Science. 2004;305(5681):183. doi: 10.1126/science.1095019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Emam K, Buckeridge D, Tamblyn R, et al. The re-identification risk of Canadians from longitudinal demographics. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2011;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malin B, Sweeney L. How (not) to protect genomic data privacy in a distributed network: using trail re-identification to evaluate and design anonymity protection systems. J Biomed Inform. 2004;37(3):179–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atreya R, Smith JC, McCoy, et al. Reducing patient re-identification risk for laboratory results within research datasets. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(1):95–101. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malin B, Sweeney L. 2000. Determining the identifiability of DNA database entries. Proc AMIA Symp; pp. 537–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loukides G, Denny JC, Malin B. The disclosure of diagnosis codes can breach research participants’ privacy. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17(3):322–7. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2009.002725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gymrek M, McGuire AL, Golan D, Halperin E, Erlich Y. Identifying personal genomes by surname inference. Science. 2013;339(6117):321–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1229566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heatherly R, Denny JC, Haines JL, et al. Size matters: How population size influences genotypephenotype association studies in anonymized data. J Biomed Inform. 2014;52:243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, Stallings SC, Gordon AS, et al. Design and anticipated outcomes of the eMERGE-PGx project: a multicenter pilot for preemptive pharmacogenomics in electronic health record systems. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;96(4):482–9. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2014.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shringarpure SS, Bustamante CD. Privacy risks from genomic data-sharing beacons. Am J Hum Genet. 2015 Nov 5;97(5):631–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raisaro JL, Tramr F, Ji Z, et al. Addressing Beacon re-identification attacks: quantification and mitigation of privacy risks. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(4):799–805. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wan Z, Vorobeychik Y, Kantarcioglu M, Malin B. Controlling the signal: Practical privacy protection of genomic data sharing through Beacon services. BMC Med Genom. 2017;10(2):39. doi: 10.1186/s12920-017-0282-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roden DM, Pulley JM, Basford MA, et al. Development of a largescale deidentified DNA biobank to enable personalized medicine. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2008 Sep 1;84(3):362–9. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wan Z, Vorobeychik Y, Xia W, et al. A game theoretic framework for analyzing re-identification risk. PloS one. 2015 Mar 25;10(3):e0120592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]