Abstract

Background

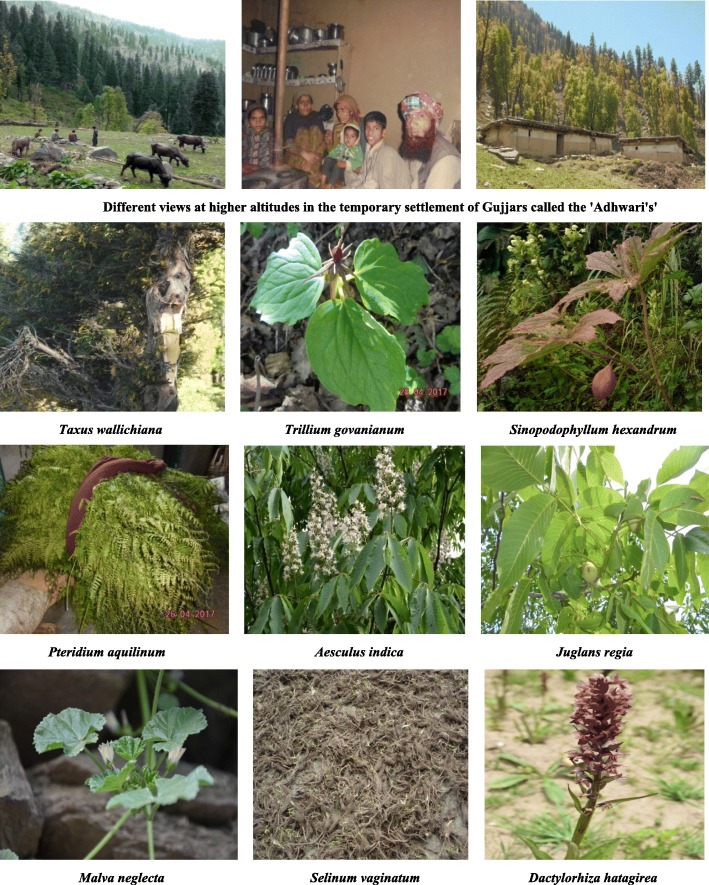

The wild plants not only form an integral part of the culture and traditions of the Himalayan tribal communities but also contribute largely to the sustenance of these communities. The tribal people use large varieties of wild fruits, vegetables, fodder, medicinal plants, etc. for meeting their day-to-day requirements. The present study was conducted in Churah subdivision of district Chamba where large populations of Muslim Gujjars inhabit various remote villages. These tribal people are semi-pastoralists, and they seasonally (early summers) migrate to the upper altitudes (Adhwari’s) along with their cattle and return to permanent settlements before the onset of winters. A major source of subsistence of these tribal people is on natural resources to a wide extent, and thus, they have wide ethnobotanical knowledge. Therefore, the current study was aimed to report the ethnobotanical knowledge of plants among the Gujjar tribe in Churah subdivision of district Chamba, Himachal Pradesh.

Methods

Extensive field surveys were conducted in 15 remote villages dominant in Gujjar population from June 2016 to September 2017. The Gujjars of the area having ethnobotanical knowledge of the plants were interrogated especially during their stay at the higher altitudes (Adhwari’s) through well-structured questionnaires, interviews, and group meetings. The data generated was examined using quantitative tools such as use value, fidelity, and informant consensus factor (Fic).

Results

This study reveals 83 plants belonging to 75 genera and 49 families that were observed to have ethnobotanical uses. Plants were listed in five categories as per their use by the Gujjars, i.e. food plants, fruit plants, fodder plants, household, and ethnomedicinal plants. The leaves, fruits, and roots were the most commonly used plant parts in the various preparations. The highest number of plants was recorded from the family Rosaceae followed by Polygonaceae and Betulaceae. On the basis of use value (UV), the most important plants in the study area were Pteridium aquilinum, Juglans regia, Corylus jacquemontii, Urtica dioica, Diplazium maximum, and Angelica glauca. Maximum plant species (32) were reported for ethnomedicinal uses followed by food plants (22 species), household purposes (16 species), edible fruits (15 species), and as fodder plants (14 species). The agreement of the informants conceded the most from the use of various plants used as food plants and fruit plants (Fic = 0.99), followed by fodder plants and household uses (Fic = 0.98) while it was least for the use of plants in ethnomedicine (Fic = 0.97). The fidelity value varied from 8 to 100% in all the use categories. Phytolacca acinosa (100%), Stellaria media (100%), and Urtica dioica (100%) were among the species with high fidelity level used as food plants, while the important species used as fruit plants in the study area were Berberis lycium (100%), Prunus armeniaca (100%), and Rubus ellipticus (100%). Some important fodder plants with high fidelity values (100%) were Acer caesium, Aesculus indica, Ailanthus altissima, and Quercus semecarpifolia. The comparison of age interval with the number of plant use revealed the obvious transfer of traditional knowledge among the younger generation, but it was mostly concentrated in the informants within the age group of 60–79 years.

Conclusions

Value addition and product development of wild fruit plants can provide an alternate source of livelihood for the rural people. The identification of the active components of the plants used by the people may provide some useful leads for the development of new drugs which can help in the well-being of mankind. Thus, bioprospection, phytochemical profiling, and evaluation of economically viable products can lead to the optimum harnessing of Himalayan bioresources in this region.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13002-019-0286-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Gujjar, Tribe, Adhwari, Himalaya, Informant consensus factor, Use value, Fidelity level

Introduction

In India, about 54 million tribal people inhabit about 5000 forest-dominated villages that constitute about 15% of the total geographic area [1]. Traditionally, these tribal groups are known to use a large number of wild plants for various purposes like medicine, food, fodder, fuel, essence, culture, and other miscellaneous purposes [2]. Thus, forests have maintained the very existence of numerous tribes and their culture for centuries, while fulfilling their social, economic, cultural, religious, nutritional, and medical needs [3–8]. Thus, these tribal communities are a rich depository of various ethnobotanical uses of plants and guardians of indigenous traditional knowledge associated with surrounding biological resources which they have used for generations in their day-to-day life [9, 10].

Among all the tribal groups, Gujjars are described as the largest pastoral community in India [11]. The tribe is described by varying names as ‘Goojar or Gurjara’ and is believed to have originated in the times of Huns. The tribe migrated to northern India and settled in various regions of Himachal Pradesh mainly Chamba, Kangra, Una, and Bilaspur [12]. The Muslim Gujjars are known to have first set foot in the princely states of Chamba and Sirmour because of the growing inadequacy of grazing resources in the neighbouring states of Jammu and Kashmir and then gradually migrated to other localities of the state [13]. The Gujjars of Chamba and Kangra are called as the ‘Ban Gujjars’ as they are nomads/semi-nomads practicing a pastoral lifestyle and comprise primarily of the Muslim population. In Chamba, the total Gujjar population is 9784 out of which 97.12% are Muslims [14], while Gujjars of Una and Bilaspur are settled Gujjars called the ‘Heer Gujjars’ and comprise mainly of Hindu population. Despite leading diverse lifestyles, one thing common among all Gujjars is that they all rear large herds of buffaloes.

The semi-nomadic Gujjars have permanent places to stay at the lower elevations, but they temporarily leave for higher altitudes called ‘Adhwari’s’ to graze their cattle mainly comprising buffaloes from mid-May till mid-October. The temporary migration takes along a predetermined set route that is covered in about 2–3 days [15]. The pasture lands are well distributed to the various families of Gujjars through a permit by the forest department of the area, thus also witnessing the proper management of the forest area. The main source of income of the Gujjars is selling of milk and milk products in the local market.

There is no doubt that the various tribal sects like the Gujjars while living in the remote mountain regions depend largely on wild plant resources for sustenance. Their nomadic employment from the ancestry makes them a good knowledge holder as a way of obtaining food and finding pasture for livestock that makes them more dependent on the environment [16]. Thus, they have a wide knowledge of use and practices of plant resources which is passed on verbally from one generation to another [17, 18]. Thereby, documentation of ethnobotanical knowledge is essential for the conservation and utilisation of biological resources [19]. This will also ensure future research on medicinal plant safety and efficacy to validate traditional use and prevent destructive changes in knowledge transmissions between generations [20, 21].

Thereby, the present study was undertaken to investigate and document the ethnobotanical knowledge of the Gujjars of Churah region, which they inherit based on the experiences and observations from their ancestors.

Methods

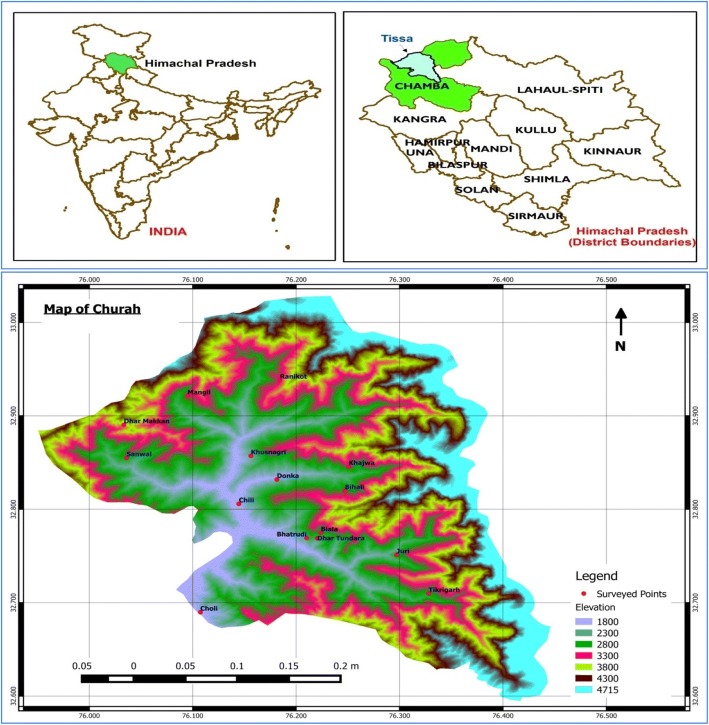

Study site

The present investigation was undertaken in Churah subdivision of district Chamba of Himachal Pradesh which is located in the Western Himalaya. The district lies between 32° 11′ to 33° 13′ N latitude and 75° 49′ to 77° 3′ E longitude with an altitudinal range varying between 800 and 5200 m amsl. Vegetation growth is mainly found in the Ravi basin, which is semi-tropical to Himalayan temperate and sub-Alpine to Alpine types. The maximum Gujjar population in the district consists of Muslims. These are a semi-pastoral tribe, and they seasonally (early summers) migrate to the upper altitudes along with their cattle and return back to permanent settlements before the onset of winters. They celebrate festivals like Eid-ul-Fitr, Id-ul-Zuha, and Shab-I-qader. The social status of these tribal people is generally poor, and they live an isolated life only confined to their own community. The main occupation of the Gujjars is rearing buffaloes, and they sell milk and milk products in the market. In the past, not much in-depth studies pertaining to various ethnobotanical aspects on Gujjar tribal community have been conducted [22, 23].

Data collection

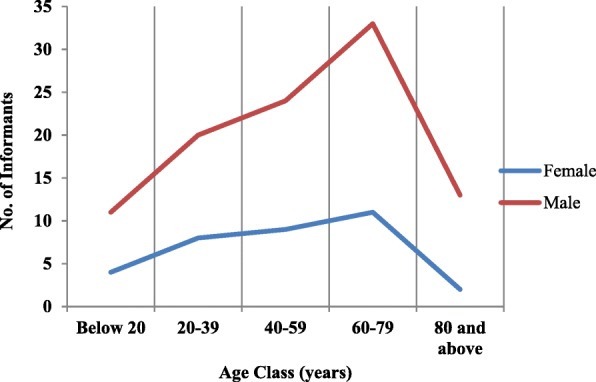

Rigorous field surveys were conducted in 15 remote villages of Churah subdivision during June 2016 to September 2017 across all seasons to collect maximum information and authenticate the information provided by the local informants during the earlier visits. These villages were shortlisted on the basis of maximum Gujjar populations and thereby were selected for the surveys (Fig. 1). The interviews were conducted both at the permanent settlements and at the higher altitudes (Adhwari’s) for which trekking was done. A total of 135 informants within the age group of 11–90 years were interviewed (Fig. 2). The data helped us to analyse the trend of flow of ethnobotanical knowledge between different age classes. Traditional healers having sound knowledge of ethnomedicinal uses of plants were also interviewed in this study. The information was collected through structured questionnaires, interviews, and group discussions on various ethnobotanical aspects (Additional file 1). Trade-related information about the plants wherever available was also recorded.

Fig. 1.

Map showing the location of surveyed villages

Fig. 2.

Demographic description of the informants

Before the initiation of the interviewing process, the consent of the informants was also taken for participation in the study. The Gujjar informants did express some uneasiness in the beginning while sharing information, but gradually they responded quite well. A translator was hired to communicate and translate Gojri into Hindi. Details pertaining to the local name of the plant collected, plant parts used, ethnobotanical use of plants, and method of use were recorded. The informants were also asked to collect and show the plant specimens on site. The complete plant specimens, including its flower or fruit, were collected, dried, and assigned a voucher number (PLP) and then deposited as a record in the herbarium of the institute for future reference. The plant specimens were identified by using Flora of Himachal Pradesh [24]; Flora of Chamba [25]; Flowers of Himalaya [26].

Data analysis

A comprehensive data analysis was done using different quantitative indices viz. use value, fidelity, and informant consensus factor (Fic).

Use value

The relative importance of the species was calculated using the use value which is a quantitative tool [27]:

UV = ΣU/n

where U is the number of plants cited by each informant for a given species and n is the total number of informants. Use values are high when there are many use reports for a plant signifying its importance, and approach to zero (0) when the use reports are low.

Validation of plant names, family, and plant authority was carried out using the database (http://www.theplantlist.org).

Informant consensus factor

Informant consensus factor was used to test the agreement on the use of plants in the various categories between the informants. Fic was calculated using the formula [28, 29]:

Fic = (Nur − Nt)/(Nur − 1)

where Nur refers to the number of use reports for a particular use/ailment category and Nt is the number of species used for a particular use/ailment category by all informants. The product of this factor ranges from 0 to 1. A high Fic value (close to 1) indicates that relatively few plant species are used by a large proportion of the informants while a low value indicates the disagreement of the informants on the use of plant species in the different categories [30–32].

Fidelity level (Fl%)

It is used to determine the most preferred species in the same use category [33].

Fl (%) = Np/N × 100

where Np refers to use reports cited for a given species for a particular category and N is the total number of use reports cited for any given species. High Fl value (near to 100%) is observed for plants in which use reports refer to its same way of use, whereas low Fl values are obtained from plants having multiple different uses [18, 34].

Scatter diagram

A scatter diagram was used to compare the flow of ethnobotanical information among the different age classes of the informants.

Results

Attributes of the informants

The characteristics of the informants is given in Fig. 2. Maximum male and female informants who had extensive ethnobotanical knowledge belonged to the age group between 60 and 79 years. The informants below the age of 20 years also responded well depicting the obvious transfer of traditional knowledge among the younger generation (Fig. 2). The children accompany the elders to the higher altitudes and help them in collecting wild plants. They learn about the uses of various plants through observations and especially wild fruits. A similar trend has been shown in the previous studies [4, 35, 36]. The translator helped us in easy communications with the Gujjar informants and even helped in collecting plant specimens from the wild. The female Gujjar informants were more comfortable in providing information to the female researcher as they are quite reticent. The tribal people of the region have a close relationship with nature and the vast experience of resource utilisation [37].

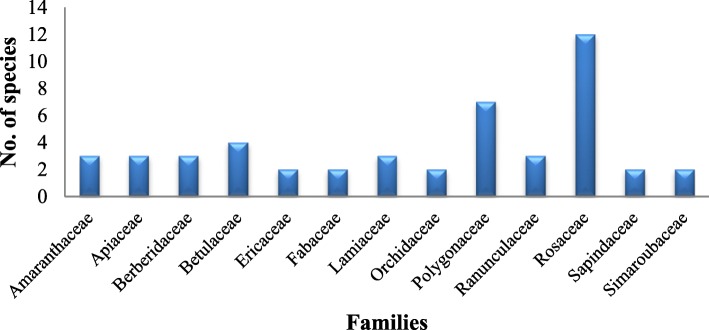

Floristic characteristics of the plants used

The study area is floristically rich, and the local inhabitants use a large number of plant species for variable uses. A total of 83 plant species belonging to 75 genera and 49 families were recorded in the study area (Table 1). The majority of plants belonged to Rosaceae (12 species), Polygonaceae (7 species), Betulaceae (4 species), Amaranthaceae (3 species), Apiaceae (3 species), Berberidaceae (3 species), Lamiaceae (3 species), and Ranunculaceae (3 species) [38–40] (Fig. 3). The genera represented by the highest number of species are Fragaria (3 species), Prunus (3 species), Rubus (2 species), Persicaria (2 species), Rhododendron (2 species), and Berberis (2 species).

Table 1.

Enumeration of plants used by the Gujjars of Churah subdivision of Chamba district

| Family | Scientific name | Local namea | Voucher no. | Used inb | Part(s) usedc | Mode of usage | Uses (no. of informants) | Total citations (∑U) | Use value (UV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adoxaceae | |||||||||

| Viburnum mullaha Buch.-Ham. ex D. Don | Tilhanj | PLP 17848 | Hum | Fr | Fruit is edible | Edible (73) | 73 | 0.54 | |

| Amaranthaceae | |||||||||

| Amaranthus paniculatus L. | Seul | PLP 17851 | Hum | Sd | Seeds are cracked and eaten and also used to prepare other recipes | Edible (115) | 115 | 0.85 | |

| Chenopodium album L. | Bathua | PLP 17990 | Hum | Lf | Used as very common vegetable | Edible (99) | 99 | 0.73 | |

| Dysphania botrys (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants | Bathu | PLP 17829 | Hum | Lf | Leaves are cooked and eaten | Edible (93) | 93 | 0.69 | |

| Apiaceae | |||||||||

| Angelica glauca Edgew. | Choru | PLP 17837 | Hum/Cat | Rt | Root powder is used to cure a cold/fever both in humans and cattle. The root is kept in almost all houses to avoid the entry of snake inside the house | Medicinal (67), household (89) | 156 | 1.16 | |

| Pleurospermum brunonis Benth. ex C.B. Clarke | Hewan | PLP 17905 | Hum | Lf, Wp | Crushed leaf juice mixed with mild hot mustard oil to prevent skin infection. The whole part is kept by local people to avoid the evil eye | Medicinal (19), household (89) | 108 | 0.80 | |

| Selinum vaginatum C.B. Clarke | Bhootkeshi | PLP 17911 | Hum | Wp | The whole plant is dried and is used as an incense | Household (71) | 71 | 0.53 | |

| Araceae | |||||||||

| Arisaema tortuosum (Wall.) Schott | Shaungal/ Leetu/Galgal | PLP 17862 | Hum | Tu | The tuber is cooked and eaten | Edible (90) | 90 | 0.67 | |

| Asparagaceae | |||||||||

| Asparagus adscendens Roxb. | Sansua | PLP 17917 | Hum | Rt | The outer layer of the roots is removed and immersed in mustard oil and applied on the scalp to control hair fall | Medicinal (56) | 56 | 0.41 | |

| Asteraceae | |||||||||

| Jurinea macrocephala DC. | Dhoop | PLP 17968 | Hum | Wp | The whole part is dried and used as incense | Household (103) | 103 | 0.76 | |

| Athyriaceae | |||||||||

| Diplazium maximum (D. Don) C. Chr. | Khasrod | PLP 17805 | Hum | Wp | A decoction of the whole plant is taken to cure body pain. Used as vegetable and pickle | Medicinal (43), Edible (121) | 164 | 1.21 | |

| Balsaminaceae | |||||||||

| Impatiens spp. | Nanteela | PLP 17923 | Cat | Lf | Used as fodder | Fodder (67) | 67 | 0.50 | |

| Berberidaceae | |||||||||

| Berberis aristata DC. | Timri/Kashmal/Kemru | PLP 17998 | Hum | Rt | Roots are boiled in water and the residue is used to cure an eye infection | Medicinal (63) | 63 | 0.47 | |

| Berberis lycium Royle | Kashmal/Kemru | PLP 17815 | Hum | Fr | Ripen fruits are eaten | Edible (99) | 99 | 0.73 | |

| Sinopodophyllum hexandrum (Royle) T.S.Ying | Khakdu | PLP 17928 | Cat | Fr | Fruits are ground and paste is kept inside the wheat flour dough and given to cattle to prevent bloating | Medicinal (61) | 61 | 0.45 | |

| Betulaceae | |||||||||

| Alnus nitida (Spach) Endl. | Koie | PLP 17864 | Cat | Lf | The leaves of the plant are given as fodder to animals | Fodder (89) | 89 | 0.66 | |

| Betula utilis D.Don | Bhojpatra | PLP 17901 | Hum | Lf, Bk | The decoction of leaves is used to cure the urinary infection, the bark is used in thatching roofs as a waterproof medium | Medicinal (12), household (98) | 110 | 0.81 | |

| Carpinus viminea Wall. ex Lindl. | Mandu | PLP 17833 | Cat | Lf, Bk | Leaves are used as fodder. The bark is used for making shoes | Fodder (69), household (6) | 75 | 0.56 | |

| Corylus jacquemontii Decne. | Jamun | PLP 17936 | Hum/Cat | Fr, Lf | Fruits are edible. Leaves are used as fodder | Edible (91), fodder (103) | 194 | 1.44 | |

| Boraginaceae | |||||||||

| Onosma hispida Wall. ex G. Don | Ratanjot | PLP 17980 | Hum | Rt | Dried roots are immersed in mustard oil and applied on hair scalp to control hair fall | Medicinal (59) | 59 | 0.44 | |

| Buxaceae | |||||||||

| Sarcococca saligna (D. Don) Müll. Arg. | Rethali | PLP 17942 | Hum | St | Used for making brooms | Household (76) | 76 | 0.56 | |

| Cannabaceae | |||||||||

| Cannabis sativa L. | Bhang | PLP 17840 | Hum | Sd | Roasted seeds are eaten as culinary by the local people | Edible (107) | 107 | 0.79 | |

| Caprifoliaceae | |||||||||

| Valeriana jatamansi Jones | Mushkbala, Shamak | PLP 17927 | Hum | Rt | Used as incense | Household (79) | 79 | 0.59 | |

| Caryophyllaceae | |||||||||

| Stellaria media (L.) Vill. | Khojua/ Koku | PLP 17922 | Hum | Ap | Aerial part is cooked and eaten as a vegetable | Edible (94) | 94 | 0.70 | |

| Commelinaceae | |||||||||

| Commelina benghalensis L. | Chura | PLP 17871 | Hum | Lf | Leaves are eaten as vegetable | Edible (110) | 110 | 0.81 | |

| Compositae | |||||||||

| Jurinea macrocephala DC. | Dhoop | PLP 17968 | Hum | Wp | The whole part is dried and used as incense | Household (103) | 103 | 0.76 | |

| Dennstaedtiaceae | |||||||||

| Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn | Nanoor | PLP 17931 | Hum | Ap | Used as fixer between soil and timber beam for roof thatching in the construction of houses. Very often given as fodder to buffaloes | Fodder (115), household (117) | 232 | 1.72 | |

| Elaeagnaceae | |||||||||

| Elaeagnus parvifolia Wall. ex Royle | Ghyeen | PLP 17881 | Hum | Fr | Fruits are edible | Edible (78) | 78 | 0.58 | |

| Ericaceae | |||||||||

| Rhododendron arboreum Sm. | Surang | PLP 18000 | Hum | Fl | Flower juice is used to make drink commonly called sherbat | Edible (90) | 90 | 0.67 | |

| Rhododendron campanulatum D.Don | Inga | PLP 17913 | Cat | Lf | A small quantity of leaves are fed to buffalos in case of a cough | Medicinal (62) | 62 | 0.46 | |

| Fabaceae | |||||||||

| Bauhinia variegata L. | Kachnar | PLP 17997 | Hum | Fl | The flowers are used to make pakoras (fried snack) and chutneys (sauce) | Edible (79) | 79 | 0.59 | |

| Desmodium elegans DC. | Pree | PLP 17994 | Cat | Lf | The leaves of the plant are given as fodder to animals | Fodder (71) | 71 | 0.53 | |

| Fagaceae | |||||||||

| Quercus semecarpifolia Sm. | Kharyu | PLP 17902 | Cat | Lf | The leaves are used as fodder | Fodder (95) | 95 | 0.70 | |

| Juglandaceae | |||||||||

| Juglans regia L. | Akhrot | PLP 17892 | Hum | Bk, Fr, Wd | The bark is used to clean teeth, fruit is edible, the wood used for various purposes | Edible (111), household (105) | 216 | 1.60 | |

| Lamiaceae | |||||||||

| Ajuga integrifolia Buch.-Ham. | Neelkanthi | PLP 17825 | Hum | Rt | Root paste is applied to the snake bite affected area | Medicinal (32) | 32 | 0.24 | |

| Clinopodium vulgare L. | Shyul | PLP 17817 | Hum | Sd | The seeds are cracked and used in various recipes | Edible (102) | 102 | 0.76 | |

| Lauraceae | |||||||||

| Neolitsea pallens (D. Don) Momiy. & H. Hara | Jhlunth | PLP 17855 | Cat | Lf | The leaves of the plant are given as fodder to animals | Fodder (78) | 78 | 0.58 | |

| Liliaceae | |||||||||

| Gagea lutea (L.) Ker Gawl. | Butti | PLP 17953 | Hum | Tu | The dried form of tubers occasionally used as spices | Edible (76) | 76 | 0.56 | |

| Malvaceae | |||||||||

| Malva neglecta Wallr. | Sochal | PLP 17977 | Hum | Lf | Cooked as vegetable | Edible (91) | 91 | 0.67 | |

| Melanthiaceae | |||||||||

| Trillium govanianum Wall. ex D.Don | Nag Chatri | PLP 17937 | Hum | Rt | Dried root powder along with buttermilk used to cure arthritis | Medicinal (33) | 33 | 0.24 | |

| Moraceae | |||||||||

| Ficus spp. | Dhura | PLP 17932 | Cat | Lf | The leaves of the plant are given as fodder to animals | Fodder (92) | 92 | 0.68 | |

| Morchellaceae | |||||||||

| Morchella esculenta (L. : Fr.) Pers. | Gucchi | PLP 17995 | Hum | Wp | The dried whole part is boiled in milk and given to a person suffering from cold and cough. The whole part is cooked and eaten | Edible (91), medicinal (26) | 117 | 0.87 | |

| Oleaceae | |||||||||

| Jasminum humile L. | Peeli chameli | PLP 17933 | Hum | Rt | Roots are used to cure ringworm | Medicinal (33) | 33 | 0.24 | |

| Orchidaceae | |||||||||

| Dactylorhiza hatagirea (D.Don) Soó | Salmpanja | PLP 17969 | Hum | Rt | The dried root powder is taken in a small amount (half tea spoon) with milk in case of weakness | Medicinal (60) | 60 | 0.44 | |

| Epipactis helleborine (L.) Crantz | Dhundali | PLP 17999 | Cat | Lf | The leaves are dried and burnt in front of animals suffering from evil eye | Household (58) | 58 | 0.43 | |

| Oxalidaceae | |||||||||

| Oxalis corniculata L. | Khati Amli | PLP 17812 | Hum | Rt | Root is used to treat dyspepsia | Medicinal (43) | 43 | 0.32 | |

| Papaveraceae | |||||||||

| Corydalis govaniana Wall. | Phul | PLP 17950 | Hum | Lf | Leaf used to cure joint pain | Medicinal (21) | 21 | 0.16 | |

| Phytolaccaceae | |||||||||

| Phytolacca acinosa Roxb. | Kafal | PLP 17944 | Hum/Cat | Lf, Fr | Leaves are used as vegetable and fruits are used to feed the poultry | Edible (97) | 97 | 0.72 | |

| Pinaceae | |||||||||

| Cedrus deodara (Roxb. ex D.Don) G.Don | Dyaar | PLP 17940 | Cat | Wd | Oil is applied on the feet of cattle to control maggots | Medicinal (45) | 45 | 0.33 | |

| Plantaginaceae | |||||||||

| Picrorhiza kurrooa Royle | Karu | PLP 17895 | Hum | Rt | Used to cure fever and jaundice | Medicinal (63) | 63 | 0.47 | |

| Polygonaceae | |||||||||

| Fagopyrum esculentum Moench | Helangala | PLP 17843 | Hum | Sd, Lf | The seeds are roasted and eaten as culinary and leaf eaten as a vegetable | Edible (88) | 88 | 0.65 | |

| Oxyria digyna (L.) Hill | Chukru | PLP 17909 | Hum | Lf | Leaves and young shoots are edible and used in chutney (sauce), pickles. Leaves are eaten to cure stomach disorders | Edible (87), medicinal (21) | 108 | 0.80 | |

| Persicaria amplexicaulis (D.Don) Ronse Decr. | Masloon | PLP 17813 | Hum | Rt | Root used in making tea | Edible (116) | 116 | 0.86 | |

| Polygonum aviculare L. | Nadi | PLP 17823 | Hum | Ap | Aerial part is cooked and eaten as a vegetable and is also used to cure pneumonia | Edible (104), medicinal (21) | 125 | 0.93 | |

| Persicaria hydropiper (L.) Delarbre | Ganeri | PLP 17882 | Hum | Lf | Leaves are cooked and eaten as a vegetable | Edible (83) | 83 | 0.61 | |

| Rheum australe D. Don | Chukri | PLP 17899 | Hum | Rt | It is used as tooth cleaning powder. An adequate amount of root powder is given to the buffalos to cure a cough | Household (89), medicinal (52) | 141 | 1.04 | |

| Rumex hastatus D. Don | Khatti butti | PLP 17836 | Hum/Cat | Lf, Wp | Fresh leaf juice is used to cure foot disease of the animal. The whole plant is wrapped around Arisaema tuber and boiled in water for 1–2 h to remove its bitterness. | Medicinal (31), household (116) | 147 | 1.09 | |

| Primulaceae | |||||||||

| Primula floribunda Wall. | Phool | PLP 17941 | Hum | Rt, Lf | Root and leaves are used to wash milk containers made up of mud or steel | Household (103) | 103 | 0.76 | |

| Ranunculaceae | |||||||||

| Aconitum heterophyllum Wall. ex Royle | Patish | PLP17906 | Hum | Rt | Used to cure a cough and fever | Medicinal (74) | 74 | 0.55 | |

| Caltha palustris L. | Butti | PLP 17951 | Cat | Lf | Leaf used to heal worm infected sores and wound | Medicinal (16) | 16 | 0.12 | |

| Ranunculus spp. | Phool | PLP 17934 | Cat | Ap | Fodder for goat and buffalos | Fodder (117) | 117 | 0.87 | |

| Rosaceae | |||||||||

| Cotoneaster spp. | Leo/Loon | PLP 17938 | Cat | Lf | Used as fodder | Fodder (83) | 83 | 0.61 | |

| Fragaria indica Andrews | Bada Mewa | PLP 17920 | Hum | Fr | Ripen fruits are eaten | Edible (79) | 79 | 0.59 | |

| Fragaria nubicola (Lindl. ex Hook.f.) Lacaita | Mewa | PLP 17946 | Hum | Fr | Ripen fruits are eaten | Edible (105) | 105 | 0.78 | |

| Fragaria vesca L. | Buti | PLP 17850 | Hum | Fr | Ripen fruits are eaten | Edible (110) | 110 | 0.81 | |

| Prunus armeniaca L. | Khumani | PLP 17939 | Hum | Fr | Ripen fruits are eaten | Edible (121) | 121 | 0.90 | |

| Prunus cornuta (Wall. ex Royle) Steud. | Jamu | PLP 17912 | Hum | Fr, Sd | Fruit is edible and seed crushed and taken internally to cure diabetes | Edible (97), medicinal (33) | 130 | 0.96 | |

| Prunus persica (L.) Batsch | Aaru | PLP 17947 | Hum | Fr | Ripen fruits are eaten | Edible (99) | 99 | 0.73 | |

| Rosa macrophylla Lindl. | Jungli gulab | PLP 17958 | Hum | Fl | Flowers are used by local healers to cure stomachache | Medicinal (17) | 17 | 0.13 | |

| Rubus niveus Thunb. | Aakhe/Karer | PLP 17965 | Hum | Fr | Ripen fruits are eaten | Edible (94) | 94 | 0.70 | |

| Sorbaria tomentosa (Lindl.) Rehder | Paddad | PLP 17926 | Cat | Lf | Leaves are used as vermicide in case of animals | Medicinal (43) | 43 | 0.32 | |

| Spiraea canescens D.Don. | Preud | PLP 17972 | Hum | St | The stems are used to make brooms and baskets (kirra) | Household (81) | 81 | 0.60 | |

| Rubus ellipticus Sm. | Aakhe/Karer | PLP 17863 | Hum | Fr | Ripen fruits are eaten | Edible (87) | 87 | 0.64 | |

| Rutaceae | |||||||||

| Boenninghausenia albiflora (Hook.) Rchb. ex Meisn. | Pisu mar butti | PLP 17809 | Hum | Lf | Leaves are used to kill bed bug | Household (78) | 78 | 0.58 | |

| Sapindaceae | |||||||||

| Acer caesium Wall. ex Brandis | Kajlu/ Jawandali | PLP 17900 | Cat | Lf | The leaves of the plant are given as fodder to animals | Fodder (99) | 99 | 0.73 | |

| Aesculus indica (Wall. ex Cambess.) Hook. | Goon | PLP 17858 | Cat | Lf | The leaves of the plant are given as fodder to animals | Fodder (56) | 56 | 0.41 | |

| Saxifragaceae | |||||||||

| Bergenia stracheyi (Hook.f. & Thomson) Engl. | Kapdolu | PLP 17952 | Hum | Rt | Used to cure kidney stone | Medicinal (49) | 49 | 0.36 | |

| Scrophulariaceae | |||||||||

| Verbascum thapsus L. | Jungli tambaku | PLP 17975 | Cat | Sd | Seeds are ground and mixed with wheat flour and given to cattle suffering from indigestion | Medicinal (31) | 31 | 0.23 | |

| Simaroubaceae | |||||||||

| Brucea javanica (L.) Merr | Hala | PLP 17854 | Hum | Fr | The fruit is used to make chutney (sauce) | Edible (111) | 111 | 0.82 | |

| Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle | Ramban | PLP 17996 | Cat | Lf | The leaves of the plant are given as fodder to animals | Fodder (45) | 45 | 0.33 | |

| Solanaceae | |||||||||

| Solanum nigrum L. | Makoi | PLP 17831 | Hum | Lf, Fr | The tender leaves are eaten to treat dysentery and fruits are edible | Edible (55), medicinal (49) | 104 | 0.77 | |

| Taxaceae | |||||||||

| Taxus wallichiana Zucc. | Nagdaun/Brahmi | PLP 17904 | Hum | Bk | The bark is very often used in flavouring tea | Edible (81) | 81 | 0.60 | |

| Thymelaeaceae | |||||||||

| Daphne papyracea Wall. ex G. Don | Nera | PLP 17954 | Cat | Lf | Leaves are given to cattle in case of cough and cold | Medicinal (55) | 55 | 0.41 | |

| Urticaceae | |||||||||

| Urtica dioica L. | Ain | PLP 17818 | Hum/Cat | Lf | The leaf paste is applied to injuries to reduce swelling. The leaves are cooked very often as a vegetable in anaemic condition. | Edible (113), medicinal (69) | 182 | 1.35 |

New or lesser known ethnobotanical uses are indicated in bold

aLocal name: in the local dialect; bUsed in: Cat cattle, Hum human

cPart(s) used: Ap aerial parts, Bk bark, Fl flower, Fr fruits, Lf leaf, Rt roots, Sd seeds, St stem, Tu tuber, Wp whole part, Wd wood

Fig. 3.

Dominant families in the study area

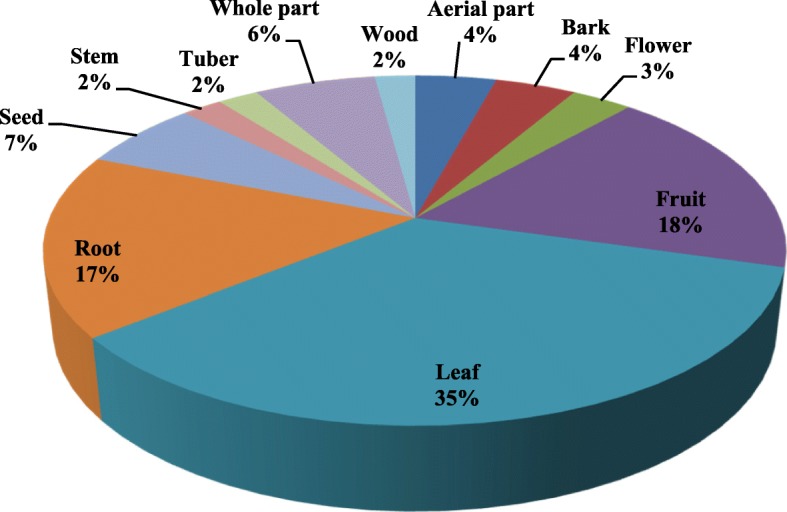

The most frequently used plant parts are leaves, fruits, roots, seeds, and whole part (Fig. 4). This result is similar to other investigations [41–48]. Easy availability of leaves with its higher metabolite content can be the reason for its preference [49, 50].

Fig. 4.

Representation of plant parts used for various categories

The use value of plants

Maximum plant species (32) were reported for ethnomedicinal uses followed by food (22 species), household uses (16 species), fruits (15 species), and fodder (14 species). Use value is an important tool for selecting the most valued plants of any region for its detailed pharmacological investigation [51]. Highest use value was reported for the plant species which had multiple uses in the area. On the basis of use value (UV), the most important plants in the study area were Pteridium aquilinum (1.72), Juglans regia (1.60), Corylus jacquemontii (1.44), Urtica dioica (1.4), Diplazium maximum (1.21), Angelica glauca (1.16), Rumex hastatus (1.09), and Rheum australe (1.04) (Table 1). More than one plant part is used for about 13% of the species. For example, the bark of Juglans regia is used in cleaning teeth, its fruit is edible, and the wood is used in various household purposes. Similarly, the fruits of Phytolacca acinosa are fed to poultry while its aerial parts are eaten as a vegetable. The fruits of Solanum nigrum are edible while the tender leaves are eaten to cure dysentery. The leaves of Betula utilis are used to cure the urinary infection, and the bark is used in thatching roofs as a waterproof medium.

Informant consensus factor

The highest informant consensus values were obtained for food and fruit plants (Fic = 0.99), followed by fodder plants and household uses (Fic = 0.98) while it was least for the plants used for ethnomedicine (Fic = 0.97) (Table 2). Ethnobotanical uses of wild plants reported during the present investigation were found in agreement to previous studies [52, 53]. This reveals that wild plants play an important role in the sustenance of the people of the region. The various forest products not only fulfil their essential household requirements but wild vegetables and fruits provide essential vitamins and minerals for a healthy life [54]. A higher number of plants used for ethnomedicine by the tribal people indicate their dependency on locally available plant resources for curing various human and cattle related ailments. The complex ailments are healed by the local healers. This also signifies the unavailability of appropriate health care facilities in these remote regions. Aconitum heterophyllum, Bergenia stracheyi, and Verbascum thapsus with similar ethnomedicinal uses have been mentioned in the previous studies [55]. Roots were mostly used for curing various ailments because of easy availability in the dried form throughout the year [56].

Table 2.

Use category and their factor informant consensus (Fic)

| Use category | Number of plant species | Use citations | F ic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food plants | 22 | 2127 | 0.99 |

| Fruit plants | 15 | 1410 | 0.99 |

| Fodder plants | 14 | 1179 | 0.98 |

| Household | 16 | 1358 | 0.98 |

| Ethnomedicinal plants | 32 | 1349 | 0.97 |

Fidelity level

The fidelity level varied from 8 to 100% in all the use categories (Table 3). Phytolacca acinosa (100%), Stellaria media (100%), and Urtica dioica (100%) were some of the species with high fidelity level used as food plants. The important species of wild fruits in the study area include Berberis lycium (100%), Prunus armeniaca (100%), and Rubus ellipticus (100%). Some of the important fodder plants with high fidelity values (100%) were Acer caesium, Aesculus indica, Ailanthus altissima, and Quercus semecarpifolia. Only a few plants with 100% fidelity were observed for ethnomedicine which were Aconitum heterophyllum, Angelica glauca, and Ajuga integrifolia while maximum plants in this category showed lower percentages of fidelity values varying from 10.91 to 47.12%. For the household use, least fidelity percentage was observed for Carpinus viminea (8%) while Angelica glauca and Boenninghausenia albiflora showed 100% fidelity values (Table 3). The fidelity level (Fl) helps in identifying the most preferred species for a particular use category. The high value of fidelity level (100%) indicates the same method of use for a specific plant [57]. Seventy-one plant species had 100% fidelity level. The ethnomedicinal plant use category had the maximum of 22 species with 100% fidelity level followed by food plant category with 18 species with 100% fidelity level.

Table 3.

Fidelity level (Fl%) of some important plant species for various use categories

| Use category | Important plants | Fl (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Food plants | Diplazium maximum | 73.78 |

| Morchella esculenta | 77.78 | |

| Polygonum aviculare | 83.2 | |

| Phytolacca acinosa | 100 | |

| Stellaria media | 100 | |

| Urtica dioica | 100 | |

| Fruit plants | Berberis lycium | 100 |

| Corylus jacquemontii | 46.91 | |

| Juglans regia | 51.39 | |

| Prunus armeniaca | 100 | |

| Prunus cornuta | 74.62 | |

| Rubus ellipticus | 100 | |

| Solanum nigrum | 52.88 | |

| Fodder plants | Acer caesium | 100 |

| Aesculus indica | 100 | |

| Ailanthus altissima | 100 | |

| Carpinus viminea | 92 | |

| Corylus jacquemontii | 53.09 | |

| Pteridium aquilinum | 49.57 | |

| Quercus semecarpifolia | 100 | |

| Ethnomedicinal plants | Aconitum heterophyllum | 100 |

| Angelica glauca | 100 | |

| Ajuga integrifolia | 100 | |

| Betula utilis | 10.91 | |

| Diplazium maximum | 26.22 | |

| Morchella esculenta | 22.22 | |

| Oxyria digyna | 19.44 | |

| Pleurospermum brunonis | 17.59 | |

| Polygonum aviculare | 16.80 | |

| Prunus cornuta | 25.38 | |

| Rheum australe | 36.88 | |

| Rumex hastatus | 21.09 | |

| Solanum nigrum | 47.12 | |

| Household (taboos, incense, basketry, brooms, etc.) | Angelica glauca | 100 |

| Betula utilis | 89.09 | |

| Boenninghausenia albiflora | 100 | |

| Carpinus viminea | 8.00 | |

| Juglans regia | 48.61 | |

| Pleurospermum brunonis | 82.41 | |

| Pteridium aquilinum | 50.43 | |

| Rheum australe | 63.12 | |

| Rumex hastatus | 78.91 |

Plants used for commercial purposes

With the onset of summer, the Gujjars start migrating to the higher altitudes with their cattle and stay in the temporary settlements called ‘Adhwari’s’. During this period, they uproot commercially important medicinal plants from the wild which they sell to local traders for financial gains [58]. The common medicinal plants harvested by them include Aconitum heterophyllum, Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Morchella esculenta, and Picrorhiza kurrooa (Table 4). Such indiscriminate exploitation of plant materials from nature can stress the natural population of these medicinal plants [59, 60]. Many of the plant species are categorised as threatened in the state that includes Aconitum heterophyllum, Angelica glauca, Berberis aristata, Betula utilis, Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Jurinea macrocephala, Sinopodophyllum hexandrum, and Taxus wallichiana (Table 5). Though these plant resources play an important role in the subsistence of the people, it may not be sustainable in the near future [61].

Table 4.

Plants used for commercial purposes and their local market value in Tissa

| Scientific name | Common name | Family | Part used | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aconitum heterophyllum | Patish | Ranunculaceae | Roots | 3500 रु/kg |

| Dactylorhiza hatagirea | Salampanja | Orchidaceae | Roots | 2000 रु/kg |

| Jurinea macrocephala | Dhoop | Leguminosae | Roots | 117 रु/kg |

| Morchella esculenta | Gucchi | Morchellaceae | Whole plant | 7500 रु/kg |

| Picrorhiza kurroa | Karu | Plantaginaceae | Rhizome | 500 रु/kg |

| Selinum vaginatum | Bhootkeshi | Apiaceae | Roots | 200 रु/kg |

| Valeriana jatamansi | Mushakbala | Caprifoliaceae | Roots | 220 रु/kg |

Table 5.

Comparison with the previous ethnobotanical studies

| Scientific name | Uses in the present study | Earlier use reports |

|---|---|---|

|

Acer caesium Wall. ex Brandis Sapindaceae |

Fodder | The wood is used for making agricultural implements, fuelwood, soil binder, fodder [72, 73] |

| Aconitum heterophyllum Wall. ex, Royle # Ranunculaceae | Medicinal | It is used to treat a cough, cold, fever, and abdominal pain [22, 53, 55] |

| Aesculus indica (Wall. ex Cambess.) Hook. Sapindaceae | Fodder | Fodder, treatment of joint pains, fruits are edible [59, 74, 53, 66] |

| Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle Simaroubaceae | Fodder | Fodder, reduce body swelling, bark juice mixed with milk to cure dysentery and diarrhoea [75–77] |

|

Ajuga integrifolia Buch.-Ham. Lamiaceae |

Medicinal | Roots are used to treat snakebite, malaria, jaundice, mouth ulcers [22, 78] |

|

Alnus nitida (Spach) Endl. Betulaceae |

Fodder | Medicinal, construction, furniture, fencing, roofing, fuel wood, fodder, utensils [78] |

|

Amaranthus paniculatus L. Amaranthaceae |

Edible | Eaten as a vegetable, the seed is edible [79, 55] |

|

Angelica glauca Edgew. # Apiaceae |

Medicinal, household | Snake repellent, root powder used to cure flatulence, dyspepsia, oedema, arthritis [80, 60, 23] |

|

Arisaema tortuosum (Wall.) Schott Araceae |

Edible | Tubers are boiled and eaten, aerial parts are eaten as vegetable [80, 60, 23] |

| * Asparagus adscendens Roxb. Asparagaceae |

Medicinal | Carminative and demulcent [64] |

|

Bauhinia variegata L. Fabaceae |

Edible | Young shoots, leaves, and flowers are eaten as vegetable, used to make pickle [36, 55] |

|

Berberis aristata DC. # Berberidaceae |

Medicinal | Piles, eye infections, fruits edible [81, 23, 82, 55, 66] |

|

Berberis lycium Royle Berberidaceae |

Edible | Whole plant part used to cure eye infections and diabetes, gum problems, kidney problems, fruits edible [23, 53, 66, 83] |

| Bergenia stracheyi (Hook.f. & Thomson) Engl. Saxifragaceae | Medicinal | A decoction of the rhizome is taken twice a day while a paste is applied topically on eyelids, used as fuel wood, diuretic [63, 69] |

| *Betula utilis D.Don # Betulaceae |

Medicinal, household | Bark, leaf, and resin are used in rheumatism, bone fracture, joint pain, swellings, asthma, blood purification, anti-cancerous, roof top and umbrella cover, fodder [84–86] |

| Boenninghausenia albiflora (Hook.) Rchb. ex Meisn., Rutaceae | Household | Antimicrobial, repel lice, fleas, and other insects [62, 87] |

| * Brucea javanica (L.) Merr Simaroubaceae |

Edible | Fodder, seed decoction taken orally for diarrhoea, malaria, and chronic diarrhoea [88, 89] |

| * Caltha palustris L. Ranunculaceae |

Medicinal | Diuretic, urinary infections, inflammation, used to clean the hands, gonorrhoea, kill maggots [68, 69] |

|

Cannabis sativa L. Cannabaceae |

Edible | Joint pains, analgesic, sedative, antispasmodic, roasted seeds are eaten [23, 64, 83, 55] |

| * Carpinus viminea Wall. ex Lindl. Betulaceae |

Fodder, household | Fodder, the wood is used for making agricultural implements, sports equipment, and construction of houses, used to heal bone fracture [90–92] |

| Cedrus deodara (Roxb. ex D.Don) G.Don Pinaceae | Medicinal | Bitter, stomachic, anthelmintic, febrifuge, wounds, and cuts [78, 93] |

|

Chenopodium album L. Amaranthaceae |

Edible | Used as vegetable, fodder, laxative, jaundice, and urinary diseases [94, 43, 82, 64, 81, 83] |

| * Clinopodium vulgare L. Lamiaceae |

Edible | Antibacterial, antitumour, leaves are edible [95] |

|

Commelina benghalensis L. Commelinaceae |

Edible | Used to cure epilepsy, vaginal infection, eaten as vegetable [43, 55, 96] |

|

Corydalis govaniana Wall. Papaveraceae |

Medicinal | Muscular pain, headache, leprosy, and rheumatism [97, 69, 68] |

|

Corylus jacquemontii Decne. Betulaceae |

Edible, fodder | Medicinal, nuts edible, leaves used as fodder [98, 99] |

|

Cotoneaster spp. Rosaceae |

Fodder | Fodder, walking sticks, baskets, fuel [100, 101] |

| Dactylorhiza hatagirea (D.Don) Soó # Orchidaceae | Medicinal | Given to person suffering from weakness [22] |

| *Daphne papyracea Wall. ex G. Don Thymelaeaceae | Medicinal | To cure bone disorders, intestinal complaints, ripen fruits edible, bark used for making paper [72, 101, 54, 102] |

|

Desmodium elegans DC. Fabaceae |

Fodder | Fodder, leaf paste applied on cuts and wounds to avoid infection to stimulate healing, the bark is used to clean teeth [103, 38] |

| Diplazium maximum (D. Don) C. Chr. Athyriaceae | Medicinal, edible | Muscular pain, young shoots are eaten as a vegetable [23, 36, 66, 102] |

| Dysphania botrys (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants Amaranthaceae | Edible | Popular flavouring for a soup of meat, cheese, and barley [104, 105] |

| Elaeagnus parvifolia Wall. ex Royle Elaeagnaceae | Edible | Fruits edible, medicinal [78, 54] |

| * Epipactis helleborine (L.) Crantz Orchidaceae |

Household | Used to treat insanity, gouts, headache, and stomach ache [106] |

|

Fagopyrum esculentum Moench Polygonaceae |

Edible | Stomach ulcer, tumour, jaundice, vegetable [63, 66] |

|

Ficus spp. Moraceae |

Fodder | Fodder, purgative, antiseptic [107, 78] |

|

Fragaria indica Andrews Rosaceae |

Edible | Fruits are edible [99] |

| Fragaria nubicola (Lindl. ex Hook.f.) Lacaita Rosaceae | Edible | Fruits are edible [82, 55] |

|

Fragaria vesca L. Rosaceae |

Edible | Fruits are edible [52] |

|

Gagea lutea (L.) Ker Gawl. Liliaceae |

Edible | Dried tubers used as spice [108] |

|

Impatiens spp. Balsaminaceae |

Fodder | Fodder, the colour obtained is used as nail paint [100, 78] |

|

Jasminum humile L. Oleaceae |

Medicinal | Powdered roots used as anthelmintic, diuretic, skin diseases, headache, mouth rash, ringworm [109, 77, 110] |

|

Juglans regia L. Juglandaceae |

Edible, household | Fruit edible, fuel, timber, fruit tonic taken for back pain [103, 94, 89, 53] |

|

Jurinea macrocephala DC. # Asteraceae |

Household | Roots are used during religious ceremonies for incense, root decoction is given once per day to treat cold and cough [111] |

|

Malva neglecta Wallr. Malvaceae |

Edible | A cough, cold, malaria, kidney disorders and cooked as a vegetable [23, 69, 112] |

| * Morchella esculenta (L.: Fr.) Pers. Morchellaceae | Edible, medicinal | Cooked and eaten, protect the stomach, nourish the lungs, and strengthen immunity [65, 66, 67] |

|

Neolitsea pallens (D. Don) Momiy. & H. Hara Lauraceae |

Fodder | Fodder, juice of fruits is used to treat scabies and eczema, seeds oil is used as an antidote [103, 44, 113] |

| * Onosma hispida Wall. ex G. Don Boraginaceae | Medicinal | Fever, pain relief, wounds, infectious diseases, hair colour [114, 115] |

| * Oxalis corniculata L. Oxalidaceae |

Medicinal | Blood purifier, appetiser, cure piles, diarrhoea, toothache, cough cure scorpion stings and skin diseases, aerial part is eaten as a vegetable [116–118, 55, 119, 43, 64, 120] |

|

Oxyria digyna (L.) Hill Polygonaceae |

Edible, medicinal | Used to make chutney, digestive and purgative [66] |

| * Persicaria amplexicaulis (D.Don) Ronse Decr., Polygonaceae | Edible | Used to treat skin diseases, jaundice, dysentery, leucorrhoea, fever, headache, indigestion, stomach pain, and blood purifier, effective in flu, fever, and joints [121–124, 53] |

| Persicaria hydropiper (L.) Delarbre Polygonaceae | Edible | Eaten as vegetable, dye plant [119, 52] |

|

Phytolacca acinosa Roxb. Phytolaccaceae |

Edible | Used to treat acne, eaten as a vegetable, root decoction is taken for cervical erosion, digestibility ulcer, liver ascites, constipation, diuresis [23, 94, 89] |

|

Picrorhiza kurrooa Royle # Plantaginaceae |

Medicinal | Fever, jaundice, improve appetite and skin infection [125, 22, 23] |

| * Pleurospermum brunonis Benth. ex C.B. Clarke Apiaceae |

Medicinal, household | Whole plant used to cure jaundice, fever, insect repellent, incense [62, 63] |

| * Polygonum aviculare L. Polygonaceae |

Edible, medicinal | Eaten as a vegetable, treat dysentery and diarrhoea [119, 43] |

| * Primula floribunda Wall. Primulaceae |

Household | Used to treat headache, rheumatism, flowers are believed to have supernatural power to ward off devils and people knowing witchcraft, flowers increase the beauty of hair of ladies [70, 71] |

|

Prunus armeniaca L. Rosaceae |

Edible | Heal constipation in cattle, fruits are edible [53, 66] |

| * Prunus cornuta (Wall. ex Royle) Steud. Rosaceae |

Edible, medicinal | Used to cure anaemia, fruits are edible [23, 66] |

|

Prunus persica (L.) Batsch Rosaceae |

Edible | Fruits are edible [66] |

|

Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn Dennstaedtiaceae |

Fodder, household | Tender fronds used as vegetables, green fronds as fodder, good soil binder, used to cure diabetes, abdominal oedema [126, 23] |

|

Quercus semecarpifolia Sm. Fagaceae |

Fodder | Fodder, timber, construction, furniture, fencing, roofing, fuel wood, medicinal [78, 127] |

|

Ranunculus spp. Ranunculaceae |

Fodder | Fodder plant, counter irritant swelling in testes, fever, stomach worms [78, 127] |

|

Rheum australe D. Don Polygonaceae |

Household, medicinal | Cleaning tooth, given to animals lost their appetite, asthma, fever, pneumonia, vegetable [22, 63] |

|

Rhododendron arboreum Sm. Ericaceae |

Edible | Used as local brew, used to make chutney [128, 66] |

| * Rhododendron campanulatum D.Don, Ericaceae | Medicinal | Leaves are mixed with tobacco and used as snuff to cure a cold [68] |

|

Rosa macrophylla Lindl. Rosaceae |

Medicinal | Used in cold and cough, flowers are edible, fruits are edible, stomach ache [23, 82] |

|

Rubus ellipticus Sm. Rosaceae |

Edible | Fruits are eaten to cure indigestion [23] |

|

Rubus niveus Thunb. Rosaceae |

Edible | Fruits are edible [94, 36] |

| * Rumex hastatus D. Don Polygonaceae |

Medicinal, household | Used to cure foot disease in cattle, used to cure jaundice, leaves eaten as a vegetable [23, 43, 82] |

| * Sarcococca saligna (D. Don) Müll. Arg. Buxaceae |

Household | Timber, fodder, fuel, and leaves in the ceiling of a roof of houses as a waterproof medium [129, 130] |

|

Selinum vaginatum C.B. Clarke Apiaceae |

Household | Used in making brew and incense making [62, 66] |

|

Sinopodophyllum hexandrum (Royle) T.S.Ying # Berberidaceae |

Medicinal | Cancer curing, bloating and appetite loss in cattle, fruit is edible [23, 53, 94, 52] |

| * Solanum nigrum L. Solanaceae |

Edible, medicinal | Vegetable, headache, fruits edible [119, 55, 53] |

|

Sorbaria tomentosa (Lindl.) Rehder Rosaceae |

Medicinal | The flowers are grinded in milk and the resulted paste is applied to burns and wounds, fruits smoked in the treatment of asthma [38, 39, 131] |

|

Spiraea canescens D.Don. Rosaceae |

Household | Basket making [69, 103] |

|

Stellaria media (L.) Vill. Caryophyllaceae |

Edible | Leaf paste applied to cure joint pains and swellings, seed powder is given to children with milk to cure skin infection and allergy and leaf paste is applied to heal wounds caused by burning or frost, eaten as a vegetable [132, 43, 133] |

|

Taxus wallichiana Zucc. # Taxaceae |

Edible | Refreshing tea, cancer curing, and thatching roofs [22, 23] |

| * Trillium govanianum Wall. ex D.Don Melanthiaceae |

Medicinal | Used to cure dysentery, reproductive disorder [125, 103, 23] |

|

Urtica dioca L. Urticaceae |

Edible, medicinal | Used to treat skin diseases, soup making, eaten as a vegetable [23, 82, 36] |

|

Valeriana jatamansi Jones Caprifoliaceae |

Household | Roots used to cure a stomachache, valerian root has been used for a century as a relaxing and sleep promoting plant [59, 23]. |

|

Verbascum thapsus L. Scrophulariaceae |

Medicinal | Indigestion in cattle [55] |

| Viburnum mullaha Buch.-Ham. ex D. Don Adoxaceae | Edible | Used to cure a cold and cough, fruits eaten [23, 53] |

*Plants with new or lesser known ethnobotanical uses reported in the present study

# Threatened wild plants of Himachal Pradesh, India [134]

Comparison with the previous ethnobotanical studies

The extensive literature review revealed the lesser known or new uses for 21 plant species from the study area (Table 5). Out of these, 13 plant species had ethnomedicinal uses, six household uses, and three edible uses. In the present study, leaf juice of Pleurospermum brunonis was used to cure skin infections while it was reported to cure jaundice and fever and used as an insect repellent in the previous studies [62, 63]. The root of Asparagus adscendens was used to control hair fall while previously it has been reported as carminative and demulcent [64]. The decoction of leaves of Betula utilis was used to treat a urinary infection while the dried root powder of Trillium govanianum was used to cure arthritis. Morchella esculenta besides eaten as a vegetable was also used to cure a cold and cough while in the previous reports it is known to protect the stomach, nourish the lungs, and strengthen immunity [65–67]. The root of Oxalis corniculata was used to treat dyspepsia, and aerial part of Polygonum aviculare was used to cure pneumonia. Seed powder of Prunus cornuta was administrated orally to cure diabetes while the same species was reported against anaemia [23]. The tender leaves of Solanum nigrum were reported to treat dysentery while it is known to cure a headache [55]. The animal ailments like a cough and a cold of buffalos were cured using leaves of Rhododendron campanulatum and Daphne papyracea. The worm-infected sores and wounds of cattle were healed using leaves of Caltha palustris while it has been reported to cure various other ailments like urinary infections and inflammation in the previous studies [68, 69]. A number of plants were used by people for household uses like leaves and roots of Primula floribunda for cleaning milk containers to remove the oiliness and odour of the utensils while it has been reported for its use to ward off devils and as a hair decorator by women [70, 71]. Very interesting information was provided by the Gujjars about the use of root of Persicaria amplexicaulis in tea making which they consume very often because of easy availability of the plant, good flavour, and a number of health benefits. Fruits of Brucea javanica were used in making chutney (sauce) while the cracked seeds of Clinopodium vulgare were used in various recipes. They make brooms from the stems of Sarcococca saligna and shoes from the bark of Carpinus viminea. The poor economic conditions of the Gujjars and remoteness of the area have made them adopt indigenous knowledge passed through their ancestry.

Conclusions

The Gujjars of Churah region constitute an important segment of the population in the region who have in-depth knowledge of diverse plant uses that can be linked back to their hereditary profession of pastoralism (Fig. 5). The infinite ethnobotanical knowledge of this tribe can also be related to their greater dependency on the wild plant resources for their sustenance because of poor living standards, illiteracy, and poverty. The younger generation is also actively involved in the seasonal activity of semi-nomadic pastoralism, and therefore, they had sound knowledge of the traditional knowledge though it was mostly concentrated in the older informants.

Fig. 5.

Glimpses of photographs clicked during the entire period of study

The present study revealed the in-depth ethnobotanical knowledge of the Gujjars. The local communities have accumulated this immense knowledge through experimentation and modifications since centuries. Knowledge and use of medicinal plants to cure various ailments is part of their life and culture that requires preservation of this indigenous knowledge. In the present scenario, it forms an essential component of sustainable development. But this traditional knowledge which is transferred from one generation to another through the words of mouth is eroding exigently. Thus, there is an urgent need for the documentation of this traditional knowledge and in-depth phytochemical investigations to evaluate potentially active compounds of the plant species to prove their efficacy.

It is essentially required to develop agro technological tools for plant species for which the same is lacking to ensure plantation in the forests/community lands available in the villages to check unsustainable harvesting of wild edibles. Value addition and product development of wild fruit plants can provide an alternate source of livelihood to the rural people. Thus, bioprospection and phytochemical profiling and evaluation of economically viable products can lead to the optimum harnessing of Himalayan bioresources in this region.

Additional file

Questionnaire for documentation of ethno-botanical related TKS in the IHR from local resource persons and traditional healers (DOCX 19 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Director, CSIR-IHBT, Palampur for providing facilities and encouragement. We are grateful to DST, Govt. of India for the financial assistance provided under a sponsored project entitled “Network programme on the convergence of traditional knowledge system for sustainable development in the Indian Himalayan Region” and Prof. S.C. Garkoti, JNU for his constant support and cooperation. We are highly grateful to the Gujjars of the Churah region for sharing valuable information without any hurdle and support of officials of various line departments is also duly acknowledged. We are grateful to the Editor and the Reviewers for their valuable suggestions which helped us in improving this manuscript.

Funding

Funds for the study were provided by DST, Govt. of India funded project GAP-0189.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors’ contributions

DR and AB carried out field surveys and data recording and prepared the manuscript. BL designed the study and edited the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Prior consent of the informants was taken while conducting these studies. This was done to adhere to the ethical standards of human participation in scientific research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Dipika Rana, Email: dipikahfri@gmail.com.

Anupam Bhatt, Email: anupam16ihbt@gmail.com.

Brij Lal, Email: brijihbt@yahoo.co.in.

References

- 1.Nath V, Khatri PK. Traditional knowledge on ethnomedicinal uses prevailing in tribal pockets of Chhindwara and Betul districts, Madhya Pradesh, India. Afr J Pharm and Pharmacol. 2010;4(9):662–670. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mishra S, Mishra MK. Ethno-botanical study of plants with edible underground parts of south Odisha, India. Int J Res Agri food sci. 2014;4(2):51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Britta OM, Tuyet HT, Duyet HN, Dung NNX. Food, feed or medicine: the multiple functions of edible wild plants in Vietnam. Econ Bot. 2003;57:103–117. doi: 10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0103:FFOMTM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Setalaphruk C, Price LL. Children’s traditional ecological knowledge of wild food resources: a case study in a rural village in Northeast Thailand. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundriyal M, Sundriyal RC. Wild edible plants of the Sikkim Himalaya: nutritive values of selected species. Econ Bot. 2001;55:377–390. doi: 10.1007/BF02866561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verma AK. Forest as the material basis of tribal society during colonial period” in Chittarajan Kumar Paty (ed) Forest Government And Tribe (New Delhi: concept publishing company). 2007; 113–122.

- 7.Singh A. Cultural significance and diversity of ethnic foods of North East India. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2006;6:79–94. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rashid A, Anand VK, Serwar J. Less known wild edible plants used by the Gujjar tribe of district Rajouri. J& K state Int J Bot. 2008;4(2):219–224. doi: 10.3923/ijb.2008.219.224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khoshoo TN. Conservation of biodiversity in biosphere. In: Khoshoo TN, Sharma M, editors. Indian geosphere biosphere programme some aspects. Allahabad, India: Nation Academy of Sciences; 1991. pp. 178–233. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma PK. Ethnobotanical studies of Gaddis- a tribal community in district Kangra, H.P. Ph.D Thesis submitted to Yaswant Singh Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tambs-Lyche H. Power, profit and poetry: traditional society in Kathiawar. Western India: Manohar Publishers, New Delhi; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahni B. Socio-religious dichotomy among the Gujjars of Himachal Pradesh. Int J Management & Soc Sci. 2016;4(2):2455–2267. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Negi TS. The scheduled tribes of Himachal Pradesh: a profile. Meerut: Raj Publishers; 1982. p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Census of India. 2011; Data retrieved from http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/population_enumeration.aspx

- 15.Crooke W. The tribes and castes of the North-Western India Vol.-II. Delhi: Cosmo Publication; 1974. p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farooquee NA, Saxena KG. Conservation and utilization of medicinal plants in high hills of the central Himalayas. Environ Conserv. 1996;23(1):75–80. doi: 10.1017/S0376892900038273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ssegawa P, Kasenene JM. Medicinal plant diversity and uses in the Sango bay area, southern Uganda. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113:521–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatia H, Sharma YP, Manhas RK, Kumar K. Ethnomedicinal plants used by the villagers of district Udhampur, J&K, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151(2):1005–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.FAO. The state of food insecurity in the world, Rome.2009.

- 20.Khoshbakht K, Hammer K. Savadkouh (Iran) - an evolutionary center for fruit trees and shrubs. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2005;53:641–651. doi: 10.1007/s10722-005-7467-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bunalema L, Obakiro S, Tabuti JRS, Waako P. Knowledge on plants used traditionally in the treatment of tuberculosis in Uganda. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151:999–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guleria V, Vasishth A. Ethnobotanical uses of wild medicinal plants by Guddi and Gujjar tribes of Himachal Pradesh. Ethnobotanical Leaflets. 2009;13:1158–1167. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rani S, Rana JC, Rana PK. Ethnomedicinal plants of Chamba district, Himachal Pradesh, India. J Med Res. 2013;7(42):3147–3157. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chowdhery HJ, Wadhwa BM. Flora of Himachal Pradesh: analysis. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh H, Sharma M. Flora of Chamba District, Himachal Pradesh. Dehra Dun: Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh; 2006. p. 881. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polunin O, Stainton A. Seventh impression. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2005. Flowers of the Himalaya. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips O, Gentry AH, Reynel C, Wilki P, Gavez-Durand CB. Quantitative ethnobotany and Amazonian conservation. Conserv Biol. 1994;8:225–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1994.08010225.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trotter R, Logan M. Informant consensus, a new approach for identifying potentially effective medicinal plants, in Plants in Indigenous Medicine and Diet, Bio-behavioural Approaches (ed. N.L. Etkin), Redgrave Publishers, Bedford Hills, New York. 1986; 91–112.

- 29.Heinrich M, Ankli A, Frei B, Weimann C, Sticher O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1863–1875. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gazzaneo LRS, Lucena RFP, Albuquerque UP. Knowledge and use of medicinal plants by local specialists in a region of Atlantic Forest in the state of Pernambuco (Northeastern Brazil) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2005;1:9. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma R, Manhas RK, Magotra R. Ethnoveterinary remedies of diseases among milk yielding animals in Kathua, Jammu and Kashmir, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;141(1):265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xavier TF, Kannan M, Lija L, Auxillia A, Rose AKF, Kumar SS. Ethnobotanical study of Kani tribes in Thoduhills of Kerala, South India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;152:78–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedman J, Yaniv Z, Dafni A, Palewitch D. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev desert, Israel. J Ethnopharmacol. 1986;16:275–287. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Musa MS, Abdelrasool FE, Elsheikh EA, Ahmed LAMN, Mahmoud ALE, Yagi SM. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Blue Nile State, South-eastern Sudan. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2011;5:4287–4297. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Łuczaj Ł. Archival data on wild food plants used in Poland in 1948. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2008;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uprety Y, Poudel RC, Shrestha KK, Rajbhandary S, Tiwari NN, Shrestha UB, Asselin H. Diversity of use and local knowledge of wild edible plant resources in Nepal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2012;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma PK, Chauhan NS, Lal B. Observations on the traditional phytotherapy among the inhabitants of Parvati valley in western Himalaya, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;92:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar S, Hamal IA. Wild edibles of Kishtwar high altitude national park in northwest Himalaya, Jammu, and Kashmir (India) Ethnobotanical Leaflets. 2009;13:195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dangwal LR, Rana CS, Sharma A. Ethno-medicinal plants from the transitional zone of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, district Chamoli, Uttarakhand (India) Indian J Nat Prod Resour. 2011;2(1):116–120. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh B, Bedi YS. Eating from raw wild plants in Himalaya: traditional knowledge documentary on Sheena tribe in Kashmir. Indian J Nat Prod Resour. 2017;8(3):269–275. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giday M, Asfaw Z, Woldu Z. Medicinal plants of the Meinit ethnic group of Ethiopia: an ethnobotanical study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124:513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ugulu I, Baslar S, Yorek N, Dogan Y. The investigation and quantitative ethnobotanical evaluation of medicinal plants used around Izmir province. J Med Plant Res. 2009;3:345–367. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abbasi AM, Khan MA, Shah MH, Shah MM, Pervez A, Ahmed M. Ethnobotanical appraisal and cultural values of medicinally important wild edible vegetables of Lesser Himalayas- Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:66. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhat JA, Kumar M, Bussmann RW. Ecological status and traditional knowledge of medicinal plants in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary of Garhwal Himalaya, India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ullah M, Khan MU, Mahmood A, Malik R, Hussain M, Wazir SM, Daud M, Khan ZK. An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous medicinal plants in Wana district south Waziristan agency, Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;150:918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sadeghi Z, Mahmood A. Ethno-gynaecological knowledge of medicinal plants used by Baluch tribes, southeast of Baluchistan, Iran, Brazilian. J Pharmacogn. 2014;24:706–715. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Araya S, Abera B, Giday M. Study of plants traditionally used in public and animal health management in Seharti Samre District, Southern Tigray, Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2015;11:22. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0015-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guler B, Manav E, Ugurlu E. Medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Bozuyuk (Bilecik–Turkey) J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;173:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghorbani A. Studies on pharmaceutical ethno botany in the region of Turkmen Sahra north of Iran (Part 1): general results. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weckerle CS, Huber FK, Yang YP, Sun WB. Plant knowledge of the Shuhi in the Hengduan Mountains, southwest China. Econ Bot. 2006;60:3–23. doi: 10.1663/0013-0001(2006)60[3:PKOTSI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sadeghi Z, Kuhestani K, Abdollahi V, Mahmood A. Ethnopharmacological studies of indigenous medicinal plants of Saravan region, Baluchistan, Iran. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;153:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li F, Zhuo J, Bo L, Jarvis D, Long C. Ethnobotanical study on wild plants used by Lhoba people in Milin Country, Tibet. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2015;11:23. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0009-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aryal KP, Poudel S, Chaudhary RP, Chattri N, Chaudhary P, Ning W, Kotru R. Diversity and use of wild and non cultivated edible plants in the Western Himalaya. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2018;14:10. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0211-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsering J, Gogoi BJ, Hui PK, Tam N, Tag H. Ethnobotanical appraisal on wild edible plants used by the Monpa community of Arunachal Pradesh. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2017;16(4):626–637. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thakur M, Asrani RK, Thakur S, Sharma PK, Patil RD, Lal B, Parkash O. Observations on traditional usage of ethnomedicinal plants in humans and animals of Kangra and Chamba districts of Himachal Pardesh in North-Western Himalaya, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;191:280–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh A, Nautiyal MC, Kunwar RP, Bussmann RW. Ethnomedicinal plants used by local inhabitants of Jakholi block, Rudraprayag district, western Himalaya, India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13:49. doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0178-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Srithi K, Balslev H, Wangpakapattanawong P, Srisanga P, Trisonthi C. Medicinal plant knowledge and its erosion among the Mien (Yao) in northern Thailand. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;123:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Balemie K, Kebebew F. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Derashe and Kucha Districts, South Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:53. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCabe S. Complementary herbal and alternative drugs in clinical practice. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2002;38:98–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2002.tb00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thakur KS, Kumar M, Bawa R, Bussmann RW. District Chamba of Himachal Pradesh. India: Evidence based Complement Altern Medicine; 2014. Ethnobotanical study of herbaceous flora along an altitudinal gradient in Bharmour forest division. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dorji Y. Women’s roles in wild yam, conservation, management and use in Bhutan. In: Khadka M, Verma R, editors. Gender and biodiversity management in the Greater Himalayas, ICIMOD 2012, p. 25-27.51. Aryal KP, Berg A, Ogle BM: Uncultivated plants and livelihood support: a case study from the Chepang people of Nepal. Ethnobotanical Research Applications. 2009;7:409–422.

- 62.Sharma PK, Chauhan NS, Lal B. Studies on plant associated indigenous knowledge among the Malanis of Kullu district, Himachal Pradesh Indian. J Tradit Knowl. 2005;4(4):403–408. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abbas Z, Khan SM, Abbasi AM, Pieroni A, Ullah Z, Iqbal M, Ahmad Z. Ethnobotany of the Balti community, Tormik valley, Karakorum range, Balistan, Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2016;12:38. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0114-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adnan M, Ullah I, Tariq A, Murad W, Azizullah A, Khan AL, Ali N. Ethnomedicine use in the war affected region of northwest Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kang Y, Luczaj L, Kang J, Wng F, Hou J, Guo Q. Wild food plants used by the Tibetans of Gongba valley (Zhouqu country, Gansu, China) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thakur D, Sharma A, SKr U. Why they eat, what they eat: patterns of wild edible plants consumption in a tribal area of Western Himalaya. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13:70. doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0198-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu D, Cheng H, Bussmann RW, Guo Z, Liu B, Long C. An ethnobotanical survey of edible fungi in Chuxiong City, Yunnan, China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2018;14:42. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0239-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kumar M, Paul Y, Anand VK. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the locals in Kishtwar, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Ethnobotanical Leaflets. 2009;13:1240–1256. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kumar PK, Singhal VK. Ethnobotany and ethnomedicinal use, chromosomal status and natural propagation of some plants of Lahaul-Spiti and adjoining hills. Journal of Botany. 2013; Hindawi Publishing Corporation.

- 70.Gupta A. Ethnobotanical studies on Gaddi tribe of Bharmour area of Himachal Pradesh. Ph.D. Thesis submitted in forestry to Dr. Yashwant Singh Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry, Nauni, Solan, Himachal Pradesh. 2011.

- 71.EMA (European Medicines Agency), “Assessment report on Primulaveris L. and/or Primulaelatior (L.) Hill, flos,” EMA/HMPC/136583/2012, 2012.

- 72.Awan MR, Iqbal Z, Shah SM, Jamal Z, Jan G, Afzal M, Majid A, Gul A. Studies on traditional knowledge of economically important plants of Kaghan valley, Mansehra district, Pakistan. J Med Plant Res. 2011;5(16):3958–3967. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nautiyal M, Tiwari JK, Rawat DS. Exploration of some important fodder plants of Joshimath area of Chamoli district of Garhwal, Uttarakhand. Current Botany. 2017;8:144–149. doi: 10.19071/cb.2017.v8.3265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singh T, Singh A, Dangwal LR. Impact of overgrazing and documentation of wild fodder plants used by Gujjar and Bakerwal tribes of district Rajouri (J&K), India. Journal of Applied and Natural Science. 2016;8(2):804–811. doi: 10.31018/jans.v8i2.876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kumar VSK. Prosopis cineraria and Ailanthus excelsa- fodder trees of Rajasthan. India International Tree Crops Journal. 1999;10:79–86. doi: 10.1080/01435698.1999.9752993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jagtap SD, Deokule SS, Bhosle SV. Some unique ethnomedicinal uses of plants used by the Korku tribe of Amravati district of Maharashtra, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Akhtar N, Rashid A, Murad W, Bergmeier E. Diversity and use of ethno-medicinal plants in the region of Swat, North Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:25. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ahmad H, Khan AM, Ghafoor S, Ali N. Ethnobotanical study of upper Siran. Journal of Herbs, Spices & Medicinal Plants. 2009;15:86–97. doi: 10.1080/10496470902787485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Martirosyan DM. Amaranth as a nutritional supplement for the modern diet. Amaranth Legacy, USA. 2001;14:2–4. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bisht AK, Bhatt A, Rawal RS, Dhar U. Prioritization and conservation of Himalayan medicinal plants: Angelica glauca Edgew. as a case study. Ethnobotany Research & Applications. 2006:11–23.

- 81.Mitra MP, Saumya D, Sanjita D, Kumar TM. Phyto-pharmacology of a Berberis aristata DC: a review. J Drug Delivery Ther. 2011;1:46–50. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Boesi A. Traditional knowledge of wild food plants in a few Tibetan communities. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10:75. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Aziz MA, Adnan M, Khan AH, Shahat AA, Al-Said MS, Ullah R. Traditional uses of medicinal plants practiced by the indigenous communities at Mohmand agency, FATA, Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2018;14:2. doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0204-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kala CP. The valley of flowers: myth and reality. Dehradun, India: International Book Distributor; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Phondani PC. A study on prioritization and categorization of specific ailments in different high altitude tribal and non-tribal communities and their traditional plant based treatments in Central Himalaya. Ph. D Thesis. Gharwal, Uttarakhand: H.N.B. Gharwal Central University, Srinagar; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sharma N. Conservation and utilization of medicinal and aromatic plants in Dhauladhar mountain range of Himachal Pradesh. Ph.D. Thesis. Dehradun, India: Forest Research Institute (Deemed University); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khulbe K, Sati SC. Antibacterial activity of Boenninghausenia albiflora Reichb. (Rutaceae) Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8(22):6346–6348. doi: 10.5897/AJB2009.000-9481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rana MS, Rana SB, Samant SS. Extraction, utilization pattern and prioritization of fuel resources for conservation in Manali Wildlife Sanctuary, Northwestern Himalaya. Journal of Mountain Science. 2012;9:580–588. doi: 10.1007/s11629-012-2066-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hong L, Guo Z, Huang K, Wei S, Bo L, Meng S, Long C. Ethnobotanical study on medicinal plants used by Maonan people in China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2015;11:32. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0019-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Samant SS, Singh M, Manohar L, Pant S. Diversity, distribution and prioritization of fodder species for conservation in Kullu District, Northwestern Himalaya, India. J Mt Sci. 2007;4(3):259–274. doi: 10.1007/s11629-007-0259-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Verma D, Singh G, Ram N. Carpinus viminea: a pioneer tree species of old landslide regions of Indian Himalaya. Curr Sci. 2009;97(9):1277–1278. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shah R, Pande PC, Tiwari L. Traditional veterinary herbal medicines of western part of Almora district, Uttarakhand Himalaya. Indian J Tradit Knowl 2008;7(2):355–359.