Abstract

The interconnections of spirituality, spiritual care (SC), and patient-centered care (PCC) have implications for advanced practice nurses (APNs) and specialty care nurses (SNs) in their everyday practice. Spirituality has been identified as an inner resource for health, promoting hope, coping, and resilience during illness concerns; encouraging health promotion and maintenance; and improving patient outcomes. SC supports this inner resource and is provided by others. Systems can help facilitate SC by supporting the inter-personal relationships as well as transdisciplinary collaborations of PCC models. SC and PCC occur within inter-personal relationships and specific healthcare environments or systems when implementing them within a spirituality framework. This article provides a brief review on conceptual definitions of spirituality, SC, and PCC models and their relationship to each other within the inter-personal connections. Exploration of implementing such care in practice is presented. Search parameters for this review included manuscripts which provided conceptual as well as quantitative and qualitative research between 1990 and 2018, in English only, with keywords of spirituality, SC, PCC, nurse, nurse practitioner, APNs, and systems. Databases searched included CINHAL, Medline, PubMed, ALTA Religion, Psych-INFO, and Ovid. Articles included in this review were based on research of the above concepts as well as operationalizing the concepts into practice.

Keywords: Advanced practice nurses, nurse, patient-centered care, spiritual care, spirituality, systems

Introduction

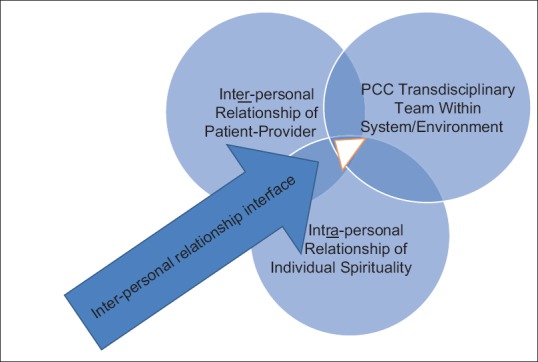

Spirituality and spiritual care (SC) have significant implications for advanced practice nurses (APNs), such as nurse practitioners, and specialty care nurses (SNs) within patient-centered care (PCC) models. Individual spirituality and the provision of SC have been documented in the literature to promote relationship development which supports health and wellness. Understanding how spirituality, SC, and PCC promote connectedness and relationships within self, between others and the environment, and within systems can provide APNs and SNs with a conceptual framework to base their nursing practice on which incorporates SC. This manuscript will provide a review of the three concepts and discuss how integration into practice might occur if barriers were removed. Summary tables outlining the concepts in the areas of relationships, interventions, and outcomes were developed based on this literature review [Tables 1-3]. A conceptual model was then developed from the literature to indicate the interconnections of the three concepts and their intersection [Figure 1]. Search parameters for this review included manuscripts which provided conceptual as well as quantitative and qualitative research between 1990 and 2018, in English only, with keywords of spirituality, SC, PCC, nurse practitioner, nurse, APNs, and systems. Databases searched included CINHAL, Medline, PubMed, ALTA Religion database, Psych-INFO, and Ovid. Studies included in this review were based on research of the above concepts as well as those providing information on operationalizing the concepts into practice.

Table 1.

Summary and comparison of relationships based on the research

| Relationships | Spirituality | Spiritual care | Patient-centered care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-personal (relationship to self; existential components) | X | X | |

| Intra-personal (relationship to others and the external world including environment, systems, and practice settings) | X | X | X |

| Transcendence/god/supreme being (relationship to) | X | ||

| Transdisciplinary (collaborative practice setting; reciprocal and empowering relationships) | X |

X indicates which concept the relationship is found

Table 3.

Summary of outcomes of spirituality, spiritual care, and patient-centered care based on the research

| Outcomes |

|---|

| Individual spirituality |

| Elevating consciousness |

| Promoting healing and growth of mind-body-spirit and relationships |

| Feeling of liberation |

| Development of inner strength (resiliency) |

| Increased hope and coping |

| Development of meaning and purpose in life |

| Spiritual care |

| Increased adherence of patient to a plan of care |

| Increased adherence of patient to a healthy lifestyle |

| Improved patient's hope and coping skills |

| Improved patient QOL and SWB* |

| Patient-centered care |

| Improved patient care |

| Increased patient satisfaction with care |

| Increased patient empowerment |

| Improved patient and health systems outcomes |

| Improved patient coping |

| Improved patient resiliency |

| Collaborative decision making which promotes a holistic approach to care |

*QOL: Quality of life, SWB: Spiritual well-being

Figure 1.

Model of inter-connectedness of spirituality, spiritual care, and patient centered care based on the literature

During periods of chaos in health, patients draw support from their individual spirituality which develops from interactions with self, the external environment and others, and the Transcendent/God/Supreme Being.[1] Individual spirituality is supported by SC received from others in an inter-personal relationship usually within specific health-care systems. Advanced practice and SNs interacting with patients in chaos also rely on their own internal spiritual development to provide SC.[1] Primary care APNs and SNs often find themselves repeatedly interacting with patients while building inter-personal and trans-disciplinary relationships over time. Patients often share spiritual concerns within this patient encounter because of this trusting relationship, providing an opportunity for APNs and SNs to contribute to PCC through SC within systems.[2,3] The ability to be more sensitive to others’ SC needs often increases when spiritual self-awareness develops within the APN and SN, promoting a holistic and mutual approach to patient care.[4]

Holistic patient care is mandated by APN and SN standards, practice guidelines, policies, and accrediting bodies.[5,6,7,8] Incorporating whole-person care within practice is further supported by the development of PCC within healthcare systems.[9] The literature lacks discussion on the importance of the provision of SC by APNs and SNs within a PCC model, and how spirituality, SC, and PCC are interconnected which is summarized in Table 1. This review will provide conceptual definitions for spirituality, SC, and PCC followed by a brief review on integrating SC into practice within a PCC model.

Conceptual Definitions

Spirituality

Spirituality has often been designated as one dimension of a multi-dimensional being, connecting one to the universe as well as a universal phenomenon based on our unique individual human relationships and experiences.[1,10,11,12,13] Spirituality includes relationship to self; relationship to the external environment such as nature and others; and a relationship with the Transcendent/God/Supreme Being.[1] These relationships promote the existential components of spirituality, i.e., finding meaning and purpose in life, in health, and in illness. Inner spiritual resources are developed by building on self-knowledge through the work of relationships and environmental interactions.[14] Spirituality then acts as an inner resource for health or in the provision of SC.

Formation of individual spirituality not only involves the development of spiritual self-awareness but also of connections to the external environment such as nature and others. These connections can be used to maintain or promote health and provide support in times of crisis or life-changing events by developing hope and increasing coping skills for example.[14,15,16,17,18] APNs or SNs with spiritual self-awareness not only have a heightened sense of others in spiritual distress but are more likely to initiate SC, due to increased comfort in approaching the other in need.[4,9,19,20]

Spiritual self-awareness is gained through life experiences, education, and reflective practices which help to promote existential and spiritual well-being while elevating one's consciousness to a higher level.[1,21,22,23] This transcending to a higher level of consciousness occurs through self-connections and pattern recognition, allowing one to become more sensitive to others’ SC needs.[23,24,25,26,27] An outcome of self-connection within the spirituality framework can lead to healing, growth, liberation, strength, coping, hope, and purpose and meaning in life to name a few.[25,28]

Spirituality is different from religiosity although they are not mutually exclusive. Most individuals have found spirituality important in health, illness, and chronic or life-limiting diseases.[19,27,29] Definitions and concepts of the two have been evolving in the spirituality literature over the past two decades.[13] Many describe spirituality as the individual journey to develop an intra-personal relationship and increase self-knowledge through interacting with the environment and others. In contrast, religiosity is the communal journey which includes mutual sacred space, text, values, and beliefs.[11,22,30,31] Patients might use religious ritual to express their spirituality or practice their spirituality within a specific faith. Both religion and spirituality value patients’ beliefs which are consistent with SC and PCC.[2,3]

Spiritual care

SC is the provision of specific interventions to support another's spirituality.[1] It involves ‘doing with’ or companioning and walking alongside patients rather than ‘doing to’ the patient. Development of a mutually agreed on plan of care within the inter-personal relationship is important in the provision of SC interventions within PCC, as it promotes the patient's ability to adhere to health-promoting lifestyles.[2]

Palliative care and oncology nurses have identified the development of the inter-personal relationship with patients as the most important aspect of being able to provide SC interventions.[32,33] They also identified subcategories to help facilitate such care which included: respect for patient individuality including values and beliefs; connecting and presence; finding meaning and purpose in life; appropriate touch; excellent communication skills; divine-related SC (religion); reciprocal nurse-patient relationship; environmental support conductive to privacy and SC; and referral. Strategies to provide adequate SC included seeking out education on such care and development of spiritual self-awareness.[32] The need for spiritual self-awareness and education was also supported in the physician and psychology literature, where lack of skills in SC interventions was noted as a deterrent to exploring patients’ spiritual needs.[34,35]

The work of relationships helps APNs, SNs, and patients find individual meaning, purpose, and fulfilment in life, and increases coping when challenges in life and illness are present.[9,12,19,20,36] APNs and SNs interventions for SC include respect for others; possessing a nonjudgmental attitude; encouraging meaningful engagement within inter-personal relationships and environments, i.e., facilitating reconciliation or forgiveness; loving and compassionate care; use of appropriate touch; being fully present and mindful; and developing or implementing sacred space within the patient's environment.[33] Patient outcomes of SC often include improved compliance with a developed plan of care; improved coping; increased hope and quality of life; and improved spiritual well-being.[10]

Patient-centered care

PCC entails empowering patients to mutually develop their plans of care with their health care providers. Such care puts the patient at the center of the decision-making process and in a relationship with APNs and SNs.[3] The provision of SC within a supportive and mutual environment fits well within the PCC model. Patients desire a strong provider-patient relationship to facilitate discussions on spiritual and religious needs, which is especially important as disease processes worsen.[36] PCC includes patient preferences and beliefs when making clinical decisions or developing plans of care.[3]

Because of the nature of APN and SN practice, inter-personal relationships develop due to repeated encounters over time within specific environments. This inter-personal relationship within a PCC environment allows for mutual goal setting between providers and patient.[3] It also contributes to a deeper understanding of the patient's spiritual concerns based on patient values and beliefs.[9] As in SC, PCC supports a trusting inter-personal relationship while supporting transdisciplinary collaboration, patient empowerment, and mutual goal setting[9,37] [Table 1].

Specific PCC interventions identified in the literature as important within a PCC model include good communication; provider-patient inter-personal relationship and transdisciplinary partnerships; health promotion; effective case management; and efficient use of resources.[38] Others have added teamwork and decentralized patient care, with whole person goals for those with serious illness and late-life supportive care needs.[39,40] These dynamic inter-personal relationships and transdisciplinary collaborations facilitate improved patient coping and health outcomes; improved resiliency; and collaborative decision making, which promotes a holistic approach to meet patient needs.[5,6,7,8,9,16] Table 2 is a summary of SC and PCC interventions and skills needed based on the literature.

Table 2.

Summary of interventions and skills based on the research

| Interventions and skills |

|---|

| Spiritual care |

| Respecting patient individuality |

| Reciprocal relationship |

| Connecting with love and compassion |

| Facilitate finding meaning and purpose in life |

| Use of appropriate touch |

| Being fully present |

| Good communication and listening skills |

| Divine-related spiritual care (religion) |

| Environment conducive to spiritual care |

| Referral |

| Patient-centered care |

| Respecting and empowering patients |

| Strong inter-personal relationship with patient |

| Mutual care-planning and goal setting |

| Good communication skills |

| Development of transdisciplinary partnerships |

| Health promotion education |

| Effective case management |

| Efficient use of resources |

| Teamwork |

| Decentralized patient care |

PCC recognizes the need to be respectful of and empower patients.[41] Before implementing PCC, organizations or systems need to have an organizational vision, commitment, culture, and climate that respect and empower patients’ choice. It is also essential to have organizational attitudes and behaviors present that support PCC. Outcomes of PCC include improved quality of care, improved patient satisfaction, and better health outcomes with transdisciplinary collaborations and relationships.[41] Table 3 is a summary of the comparison of outcomes of spirituality, SC, and PCC based on this present research.

Models for PCC have visualized spirituality from the perspective of a system's culture which can affect those working within that system or organization.[11] Just like spirituality, organizations have been concerned with meaning, purpose, and values. Approaching clinical care from an interrelated perspective of finance, service, and quality can decrease barriers to the provision of SC interventions by practitioners.[11] Supporting the development of self-knowledge and inter-personal relationships in work environments can promote a culture of spiritual elements which provide meaningful and purposeful work for health care providers.[2]

Integrating concepts into education and practice

The literature has outlined some of the concepts and characteristics found in spirituality, SC and PCC [Figure 1]. Understanding where the interface occurs between the three within the inter-personal relationship is important across disciplines and within various clinical environments/organizational settings [Table 1]. Patients have indicated a greater desire for SC interventions and prefer SC interventions over SC assessments as indicated in the literature.[42,43] In spite of this, SC interventions have not generally been the focus of educational content in nursing curriculum or care which presents as a barrier to SC in practice.[2,13] Spiritual assessments and referrals have been the main objectives in education and practice.[13] This approach of assess and refer does not always meet the immediate SC needs of patients. The opportunity to provide SC care that is needed in-the-moment might be lost if waiting for others to respond to referrals.[13]

Most APNs and SNs want to provide SC within a supportive environment but often face barriers. These barriers include lack of SC education and skills as mentioned earlier, lack of time, and lack of support by systems or work environments.[19,32,44] Lack of spiritual self-awareness and lack of education on SC often impede the provider's comfort and skills in providing SC interventions.[44] Self-awakening of the provider's inner spirituality through their experiences and specific education can lead to increased ability to identify SC needs in others and increased comfort in initiating SC interventions.[45] Spiritual self-awareness and education thus help to increase knowledge, raising one to higher levels of consciousness, and increasing comfort in providing SC interventions.[46,47]

Reflective practice can help promote spiritual self-awareness.[21] Prioritizing self-care of the provider and pursuing experiences that connect one to the environment (nature, music, and others) also supports the individual spiritual development of APNs, SNs, and patients.[47] Changes in nursing curricula to promote spiritual self-awareness can occur through such activities as journaling or adoption of some form of meditative or reflective practice. In addition, simulations can be developed which employ standardized patients requiring SC. Such simulations would provide a safe environment to learn to recognize patients SC needs and develop skills to provide such care.[48]

The research supports patients’ desire for SC, especially with illness, chronic or life-limiting disease. Research has also identified barriers for providers to give SC. Systems that have not always been supportive of such care for both the patient and provider can hinder the provision of SC. This has the potential to alter patient and health systems outcomes negatively and decrease meaningful work for providers. Education on spiritual self-awareness and caregiving within PCC supportive systems will assist in meeting patients’ needs in the spiritual domain.

Discussion

The literature provided inter-related concepts on spirituality, SC, and PCC for APN and SN practice. These are summarized in Tables 1-3. Spiritual self-awareness is important in forming the basis of one's own spirituality to use as an inner resource for health and to provide SC. This self-connection allows movement to higher levels of consciousness and knowledge within an intra-personal relationship.[46]

Within the inter-personal relationship, interacting with the environment outside of self assists in cultivating and increasing self-awareness and knowledge. In practice, patients, APNs, and SNs will be in varying stages of developing this self-awareness and self-knowledge, which will require practitioner skill in navigating the SC needs of patients within systems. This skill is often gained through experience and education as discussed in the literature.[21] Curriculum and continuing educations for APNs and SNs for spiritual caregiving need to be addressed since lack of education and skill, and lack of comfort with spiritual caregiving have been identified as major barriers to providing such care.

A system in which care is provided is the environment in which SC and PCC transpire with transdisciplinary and collaborative relationships occurring. These systems can support the provision of SC by acknowledging the time needed in the encounter for such care, and encouraging SC skill development of health care providers through education and reflection. Within this model, healthcare systems influence how SC is supported and provided by individual practitioners and transdisciplinary teams. Further exploration is needed on how to utilize the inter-personal relationships of spirituality, SC, and PCC by practitioners as well as systems which can improve healthcare systems functioning and patient outcomes.

Conclusion

APNs and SNs provide holistic care within the patient-nurse inter-personal relationship within a larger system. Organizational support is needed to develop environments which support the provision of SC to patients as well as developing environments that sustain meaningful work for providers. This support will also encourage transdisciplinary collaborations, with potential to improve patient and healthcare outcomes. Holistic care has been mandated by professional and accrediting bodies. Lack of SC and thus lack of providing holistic care can lend itself to potential ethical concerns.[16] Putting patients at the center of care within a PCC model provides a system supportive of spirituality and SC interventions. Including content on spirituality and SC within education programs will better prepare APNs and SNs in providing holistic care and help to shape the systems in which such care is provided.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Reed PG. An emerging paradigm for the investigation of spirituality in nursing. Res Nurs Health. 1992;15:349–57. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincensi B, Solberg M. Assessing the frequency nurse practitioners incorporate spiritual care into patient-centered care. J Nurs Pract. 2017;13:368–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. 2010. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 07]. Available from: http://www.books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id¼12956 .

- 4.Olson M, Sandor M, Sierpina V, Vanderpool H, Dayao P. Mind, body and spirit: Family physicians’ beliefs, attitudes and practices regarding the integration of patient spirituality into medical care. J Relig Health. 2006;45:234–47. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Associat ion of Col leges of Nursing. Adult-Gerontology Acute Care and Primary NP Competencies. 2016. [Last retrieved on 2018 Mar 07]. Available from: http://www.c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.nonpf.org/resource/resmgr/competencies/NP_Adult_Geri_competencies_4.pdf .

- 6.Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. Competencies for the Hospice and Palliative Advanced Practice Nurse. 2014. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 07]. Available from: https://www.hpna.org/FileMaintenance_View.aspx?ID=1991 .

- 7.National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculty. Nurse Practitioner core Competencies Content. 2017. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 07]. Available from: http://www.c.ymcdn.com/sites/nonpf.site-ym.com/resource/resmgr/Competencies/NPCoreCompsContentFinalNov20.pdf .

- 8.Oncology Nursing Society. Oncology Nurse Practitioners Competencies. 2007. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.ons.org/sites/default/files/npcompentencies.pdf .

- 9.Pulchaski C. Integrating spirituality into patient care: An essential element of person-centered care. Polish Arch Intern Med. 2013;123:491–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramezani M, Ahmadi F, Mohammadi E, Kazemnejad A. Spiritual care in nursing: A concept analysis. Int Nurs Rev. 2014;61:211–9. doi: 10.1111/inr.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wattis J, Curran S, Rogers M, editors. Spiritually Competent Practice in Health Care. London, UK: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2017. What does spirituality mean for patients, practitioners and health care organizations? [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weathers E, McCarthy G, Coffey A. Concept analysis of spirituality: An evolutionary approach. Nurs Forum. 2016;51:79–96. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vincensi B. Spiritual Care in Advanced Practice Nursing (2011). Dissertations. Paper 201. 2011. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 22]. Available from: http://www.ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/201 .

- 14.Fisher J. The four domains model: Connecting spirituality, health and well-being. Religions. 2011;2:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray J. Measuring spirituality: Conceptual and methodological considerations. J Theory Construct Test. 2011;10:58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pesut B. Fundamental or foundational obligation? Problematizing the ethical call to spiritual care in nursing. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2006;29:125–33. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200604000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selman LE, Brighton LJ, Sinclair S, Karvinen I, Egan R, Speck P, et al. Patients’ and caregivers’ needs, experiences, preferences and research priorities in spiritual care: A focus group study across nine countries. Palliat Med. 2018;32:216–30. doi: 10.1177/0269216317734954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torskenæs KB, Baldacchino DR, Kalfoss M, Baldacchino T, Borg J, Falzon M, et al. Nurses’ and caregivers’ definition of spirituality from the Christian perspective: A comparative study between Malta and Norway. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23:39–53. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein-Peterson ZD, Sullivan AJ, Enzinger AC, Trevino KM, Zollfrank AA, Balboni MJ, et al. Examining forms of spiritual care provided in the advanced cancer setting. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32:750–7. doi: 10.1177/1049909114540318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puchalski CM, Vitillo R, Hull SK, Reller N. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:642–56. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.9427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burkhart L, Hogan N. An experiential theory of spiritual care in nursing practice. Qual Health Res. 2008;18:928–38. doi: 10.1177/1049732308318027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burkhart L, Solari-Twadell P. Spirituality and religiousness: Differentiating the diagnoses through a review of the nursing literature. Nurs Diagn. 2001;12:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman M. Health as Expanding Consciousness. 2nd ed. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedemann ML, Mouch J, Racey T. Nursing the spirit: The framework of systemic organization. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39:325–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McEwan W. Spirituality in nursing: What are the issues? Orthop Nurs. 2004;23:321–6. doi: 10.1097/00006416-200409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuck I. Development of a spirituality intervention to promote healing. J Theory Construct Test. 2004;8:67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyler ID, Raynor JE., Jr Spirituality in the natural sciences and nursing: An interdisciplinary perspective. ABNF J. 2006;17:63–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newlin K, Knafl K, Melkus GD. African-American spirituality: A concept analysis. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2002;25:57–70. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200212000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith D. Rehabilitation counselor willingness to integrate spirituality into client counseling sessions. J Rehabil. 2006;72:4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reinert KG, Koenig HG. Re-examining definitions of spirituality in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:2622–34. doi: 10.1111/jan.12152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlehofer M, Omoto A, Adelman J. How do “Religion” and “Spirituality” differ? Lay definitions among older adults. J Sci Study Religion. 2008;47:411–25. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keall R, Clayton JM, Butow P. How do Australian palliative care nurses address existential and spiritual concerns? Facilitators, barriers and strategies. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:3197–205. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker H, Waterworth S. New Zealand palliative care nurses experiences of providing spiritual care to patients with life-limiting illness. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2017;23:18–26. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2017.23.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Amobi A, Phelps AC, Gorman DP, Zollfrank A, et al. Why is spiritual care infrequent at the end of life? Spiritual care perceptions among patients, nurses, and physicians and the role of training. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:461–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elkonin D, Brown O, Naicker S. Religion, spirituality and therapy: Implications for training. J Relig Health. 2014;53:119–34. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Best M, Butow P, Olver I. Do patients want doctors to talk about spirituality? A systematic literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1320–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haley JM. Classroom to clinic: Incorporating adolescent spiritual/faith assessment into nurse practitioner education & practice. J Christ Nurs. 2014;31:258–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Constand MK, MacDermid JC, Dal Bello-Haas V, Law M. Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:271. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, Dirmaier J. An integrative model of patient-centeredness – A systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107828. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schellinger SE, Anderson EW, Frazer MS, Cain CL. Patient self-defined goals: Essentials of person-centered care for serious illness. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35:159–65. doi: 10.1177/1049909117699600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morgan S, Yoder LH. A concept analysis of person-centered care. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30:6–15. doi: 10.1177/0898010111412189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abu-El-Noor MK, Abu-El-Noor NI. Importance of spiritual care for cardiac patients admitted to coronary care units in the Gaza strip: Patients’ perception. J Holist Nurs. 2014;32:104–15. doi: 10.1177/0898010113503905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsimtsiou Z, Kirana PS, Hatzichristou D. Determinants of patients’ attitudes toward patient-centered care: A cross-sectional study in Greece. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97:391–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vermandere M, De Lepeleire J, Smeets L, Hannes K, Van Mechelen W, Warmenhoven F, et al. Spirituality in general practice: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e749–60. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X606663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paal P, Helo Y, Frick E. Spiritual care training provided to healthcare professionals: A Systematic review. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2015;69:19–30. doi: 10.1177/1542305015572955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newman M. Transcending Presence: The Difference that Nursing Makes. 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: E.A. Davis, Co; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dossey B, Keegan L. Holistic Nursing: A Handbook for Practice. 7th ed. Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Desmond MB, Burkhart L, Horsley T, Gerc S, Bretschneider A. Development and psychometric evaluation of spiritual care simulation and companion performance checklist for a Veteran using a standardized patient. Clin Sim Nurs. 2018;14:29–44. [Google Scholar]