Abstract

Summary: Objective and systematic methods to search, review, and synthesize published studies are a fundamental aspect of carcinogen hazard classification. Systematic review is a historical strength of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monographs Program and the United States National Toxicology Program (NTP) Office of the Report on Carcinogens (RoC). Both organizations are tasked with evaluating peer-reviewed, published evidence to determine whether specific substances, exposure scenarios, or mixtures pose a cancer hazard to humans. This evidence synthesis is based on objective, transparent, published methods that call for extracting and interpreting data in a systematic manner from multiple domains, including a) human exposure, b) epidemiological evidence, c) evidence from experimental animals, and d) mechanistic evidence. The process involves multiple collaborators and requires an extensive literature search, review, and synthesis of the evidence. Several online tools have been implemented to facilitate these collaborative systematic review processes. Specifically, Health Assessment Workplace Collaborative (HAWC) and Table Builder are custom solutions designed to record and share the results of the systematic literature search, data extraction, and analyses. In addition, a content management system for web-based project management and document submission has been adopted to enable access to submitted drafts simultaneously by multiple co-authors and to facilitate their peer review and revision. These advancements in cancer hazard classification have applicability in multiple systematic review efforts. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP4224

Introduction

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monographs Programme and the United States National Toxicology Program (NTP) Office of the Report on Carcinogens (RoC) conduct cancer hazard assessments that use transparent and objective methods to inform public health actions to limit human exposure to carcinogens. These and other systematic reviews use structured and reproducible methods to support evidence-based decision-making in medicine and public health (IOM, 2011). This process involves multiple collaborators and requires problem formulation and comprehensive literature searches, followed by structured evidence evaluation and synthesis. For both programs, systematic review is a historical strength, and evidence synthesis requires interpreting and integrating data in multiple domains, including a) human exposure, b) epidemiological evidence, c) evidence from experimental animal studies, and d) other relevant data (e.g., metabolism) and mechanistic evidence on key characteristics of carcinogens (e.g., is genotoxic, modulates receptor-mediated effects) (Smith et al. 2016).

The IARC Monographs follow rigorous guidelines for the selection, review, synthesis, and presentation of evidence, published as the Preamble to each IARC Monograph volume since Volume 3 (IARC 1973). Agents are selected for evaluation based on a suspicion of carcinogenicity and evidence of human exposure, following consideration of public nominations by an independent advisory group (Straif et al., 2014). The scientific review and evaluation is conducted according to a specified schedule (IARC 2018). Evaluations are announced a year in advance along with a call for data, a call for experts, and an opportunity to request observer status. Participants and a summary of their disclosed interests are announced two months in advance of the in-person meeting, at which all premeeting materials undergo rigorous peer review, and consensus evaluations are reached. A working group of subject-matter experts, carefully screened to eliminate conflict of interest, undertake the consensus evaluations, following clear timelines and prespecified criteria for evidence inclusion, summary, integration, and evaluation.

The RoC is a congressionally mandated, science-based, public health report that identifies agents, substances, mixtures, or exposure scenarios (collectively called “substances”) in the environment that pose a hazard to people residing in the United States. Substances are evaluated using established listing criteria and a four-part multistep process with opportunity for public comment, scientific input, and peer review (NTP 2018). For each substance under review for the RoC, the Office of the RoC prepares a monograph using a published protocol that specifies how peer-reviewed, published evidence is identified and evaluated in order to determine whether a substance poses a cancer hazard to humans (NTP 2015a). Each monograph is peer reviewed by a panel of experts in public forum.

Like any high-quality systematic review, the protocols described for the NTP RoC and the IARC Monographs are labor-intensive. The protocols describe a process of scientific peer review and consensus that requires time, resources, and an interdisciplinary team of experts to search, extract, organize, and critically evaluate a large number of scientific publications. Further, in our experience we have found that standardizing protocols for literature searches and data extraction can enhance objectivity as well as uniformity across assessments.

In this brief communication, we describe several web-based collaborative tools that have recently been developed and have been integrated into the systematic review process of the IARC monographs and the RoC. These software tools are in accordance with input from external advisory groups (Straif et al. 2014) and are also in line with recommendations from the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) and the National Research Council (NRC) (NRC 2011; NRC 2014; NAS 2017). These new tools have enabled literature-search strategies to be stored, and the search terms, the numbers of studies identified, and the reasons for any exclusions to be recorded. Further, data extraction procedures have been modernized to ensure that the identified studies are reviewed, analyzed, evaluated, and reported in an objective and consistent manner. Descriptive statistics are automatically calculated for animal bioassay results. The evaluation of study strengths and weaknesses is formalized and structured datasets can be generated to facilitate further statistical analyses (e.g., meta-analyses). Moreover, a customized content management system has streamlined the workflow and enhanced collaboration within the multidisciplinary expert review team.

By focusing on the fundamental scientific principles in guided expert-based systematic review, the effort has taken advantage of collaborative opportunities in the two programs, thereby conserving resources. By developing open-source and flexible solutions, custom refinements were possible to address the different needs of the two programs. This focus and development methodology also ensure broad applicability in multiple systematic review communities, including providing a platform for piloting new methodological advances.

Here, we describe key features of the online tools that have resulted from our collaboration in advancing systematic review methods, focusing on Health Assessment Workplace Collaborative (HAWC) (for literature searches) and Table Builder (for data tabulation and analysis). In addition, we describe a content management system for web-based project management and document submission that was designed to facilitate the evidence evaluation and peer review process.

Software Systems

HAWC

HAWC is a publicly accessible online, collaborative workspace that was designed to facilitate all aspects of environmental human health assessments (https://hawcproject.org). The HAWC web-based application is a content management system in which users create public or private assessments with a tiered permission system. HAWC is developed using the Python-based Django web framework and a relational PostgreSQL database. The source code is open-source and publicly available for reuse (Shapiro et al. 2018); to date, at least four custom deployments of the HAWC software are known, including the public site mentioned above. HAWC is free and open to the public; training videos exist on the website.

HAWC is designed as a series of modules that can be used independently, or in concert, to accomplish all steps of a common workflow in evaluating the data on hazards and dose–response of chemicals in studies in humans, experimental animals, and the mechanistic information. One module of this software that is now routinely used by both IARC and NTP is the literature-search strategy and review component. HAWC allows a team to electronically store, evaluate, share, and present multiple literature searches and record the review and triage of the publications identified. References can be added in HAWC via searches in PubMed using MeSH tags (Figure 1), imported using PubMed identification numbers (i.e., PMID), or input manually from sources other than PubMed. In addition, an entire reference database can be imported from common reference management software systems (e.g., Endnote or Reference Manager). Literature tags for the triage of publications are fully customizable for each assessment and are hierarchical (i.e., child tags can be created under parent tags), resulting in tabular formats or visualizations. One or more tags can be manually applied to each reference in HAWC. Exports of the triaged reference lists and details of the total count with the various tags can be created. Examples of the utility of this system have been published previously in peer-reviewed literature (Smith et al. 2016; Chappell et al. 2016; Guyton et al. 2018). Once the key literature has been identified, data can be extracted and reviewed systematically for human health assessments. A common workflow used by other users of the HAWC software is to conduct literature screening using other software systems such as SWIFT (Howard et al. 2016) or DistillerSR (Evidence Partners), and then importing results into HAWC. Data can be extracted directly into HAWC or other software tools; however, the workflows of the IARC Monographs and NTP RoC use a separate tool, Table Builder, specifically designed for data extraction during systematic review, further described below.

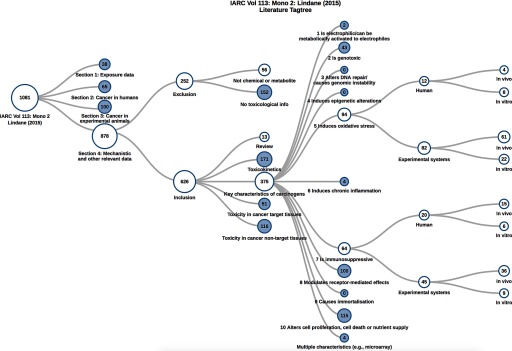

Figure 1.

Literature tagging using HAWC. User-defined tags, organized in a hierarchical structure, can be created for each assessment and manually applied to literature identified from searches in HAWC via PubMed or imported from other software platforms. Here, we present a representative image generated by HAWC showing the results of a literature search per the key characteristics of carcinogens (Smith et al., 2016) and other topics relevant to mechanistic data evaluation for lindane (Group 1; IARC 2017b). The far-left node in the figure indicates that a total of 1,081 references were identified from literature searches (also recorded in HAWC). Of these references, 878 relevant references were identified for Section 4 of the IARC monograph, and of those, 626 were included and 252 were excluded. Of note, more than one exclusion criteria may apply to each excluded study, and more than one category may apply to included studies (e.g., if more than one key characteristic, endpoint, species, etc., was evaluated). The visualizations are interactive; tags can be expanded, and child-tags are revealed with the count of references in each tag; other tags may be left unexpanded. Expanded and unexpanded tags are represented by unshaded and shaded circles, respectively.

To date, HAWC has over 950 users and over 550 assessments. Some HAWC-enabled assessments include literature reviews and are available for public access. Publicly available assessments in HAWC include a NAS report evaluating low-dose toxicity from endocrine active chemicals (NAS 2017, https://hawcproject.org/assessment/351/), a literature review of epigenetics data on genotoxic agents (Chappell et al. 2016, https://hawcproject.org/assessment/185/), and an NTP research report on Bisphenol A analogs (Pelch et al. 2017, https://hawcproject.org/assessment/46/). HAWC has been used for developing all IARC Monographs since 2014, beginning with Volume 112 (IARC 2017a). The RoC has used HAWC for 16 evaluations or scoping activities to date. HAWC is also used routinely by Texas Commission on Environmental Quality for conducting and documenting the literature searches, compiling references from PubMed and other sources, tagging literature for inclusion or exclusion, and analysis of the available evidence (Schaefer and Myers 2017).

Table Builder

The Table Builder is a web-based content management system that was designed to capture extracted data from the published literature and facilitate qualitative and quantitative analyses (e.g., meta-analyses, statistical testing) for human health assessments of potential carcinogens. From the same codebase and fundamental data fields, it has also been customized to meet the different needs of the NTP and IARC. This customization allows for standardization of key fields of extracted data from pertinent studies and enables the flexibility to incorporate and explore further innovations that have not yet been widely implemented. The Table Builder software was designed using the Meteor Javascript web framework and uses a document-based MongoDB database. The software is open-source, with source code available for reuse (Shapiro and Addington 2018). A test web-application is available at https://table-builder.com/; login details are on the home page, and the database is reset weekly. The test web application will be available for at least two years post publication of this article.

As with HAWC, this web-based tool has tiered access and assessment-level permissions for multiple collaborators. It is designed for use by collaborative expert teams to tabulate and analyze data. Data tables, reports, and figures can be exported from Table Builder for inclusion into final public reports. The Table Builder software contains a set of fixed fields and a standardized vocabulary for data extraction (including drop-down menus) (Figure 2A, 2B). This promotes consistency in reporting of data and in use of terminology within and across assessments. Data extraction templates currently exist for four data types: a) details relevant to human exposure to the substance, b) epidemiological evidence, c) animal bioassay evidence, and d) genotoxicity data. All data entered into the tool are associated with a reference in the database, which ensures easy mapping to the corpus of literature. This software allows teams of users to extract characteristics of studies and results, comment on elements of study strengths and limitations, and list potential covariates and confounders in epidemiological studies. The software is reactive; i.e., whenever a user changes any data in the system, it is updated for all other users of the system in real-time (a feature we have found to be indispensable during collaborative IARC Monograph meetings). Further, the software provides data curation and management functions to members with privileged accounts, with simple checks for completion of quality assurance and quality control.

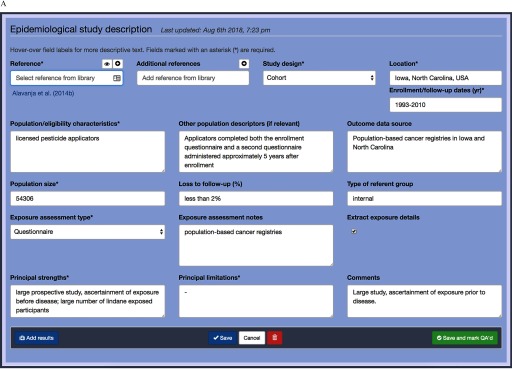

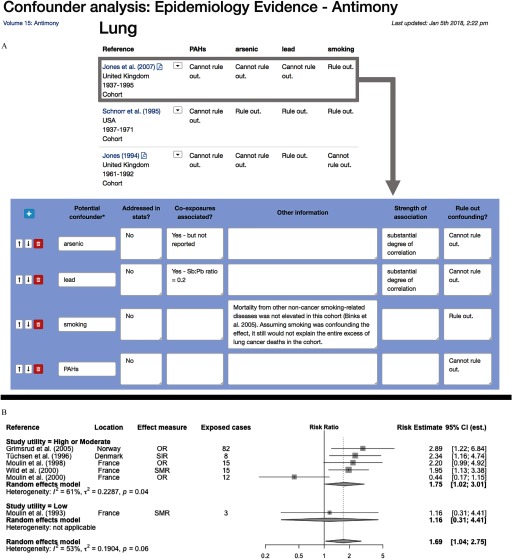

Figure 2.

Data extraction and summary tables in Table Builder. (A) Data extraction form for the Table Builder software; epidemiological study description as shown for the IARC Monographs including population, exposure characteristics, and strengths and limitations of study. (B) Results view of the same study; a single study can have multiple sets of results, generally defined by organ sites, with potential confounders. (C) The tabular web-view of the data after data entry in the prior panels; this view parallels the Microsoft® Word output reports generated which are subsequently used in final monographs. Users can edit content in rows; rows are locked after quality assessment/quality control (QA/QC) to prevent further changes.

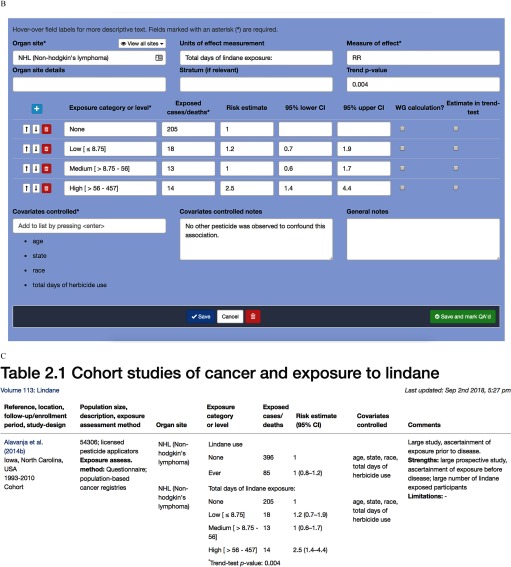

In addition, data analysis can be conducted via the web interface. For animal bioassay evidence, descriptive statistics are performed from within the software (dose–response trends using the Cochrane-Armitage test for linear trend, and Fisher’s exact pairwise significance test). For epidemiological data, forest plots can be created and filtered by cancer site, facilitating the interpretation and synthesis of data for report writing, especially when the number of extracted elements is large. The NTP RoC has implemented an additional module that allows users to evaluate the impact of potential confounding variables at the individual study level and across studies (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Confounder analysis and forest plot/meta-analysis from data captured in Table Builder. (A) The summary table allows users to identify and view potential confounders in a matrix format and evaluate whether handling of these potential confounders can explain the findings within and across studies. This example displays studies examining the association between exposure to antimony and lung cancer mortality. Below the summary table, pertinent information on potential confounders within each study are extracted and evaluated. (B) A stratified forest plot and random effects meta-analysis from data captured in table builder and generated from table builder exports using R software. Exports can be used in other software packages such as Excel, SAS, or Stata for customized analyses and reformatting.

A number of different output formats are available in addition to the html format, including Microsoft® Word tables (formatted for the structured reports of RoC or IARC) (Figure 2C). The data in Table Builder can also be downloaded into Microsoft® Excel files and imported into statistical software to produce visualizations, including forest plots and, if warranted, to conduct a meta-analysis (NTP 2016a, IARC 2017b). The “meta” software package in R (R Core Team) (Schwarzer 2007) is being used within the software to generate customizable forest plots and meta-analyses that can be stratified by the variables that are captured in Table Builder (Figure 3B). To date, many tables in IARC Monographs (IARC 2018) were generated using Table Builder with minor modifications starting in Monograph 112, as well as for RoC monographs (NTP 2018) starting with the 14th edition of the RoC.

Content Management System for Project Management and Document Submission

The use of a content management system can be an effective means for managing the editorial processes of document submission, peer review, and version control of multiple revisions to draft manuscripts. Various content management systems are commercially available and currently used by scientific journal editors and publishers [e.g., Drupal™ (Drupal Association), RSuite® (Orbis Technologies), SharePoint® (Microsoft Corp.), WordPress (WordPress Foundation, https://wordpressfoundation.org/trademark-policy/)]. Custom solutions, such as those developed internally at IARC (IARC 2017c), can also be tailored to project or program needs for managing collaborative projects that involve a large number of contributors.

Essential requirements of such a system include the ability to centralize submissions in one place and to handle the assignment and management of authors and reviewers to particular drafts, such as the various sections of a monograph volume. Such systems can be used by multiple contributors, with tiered access and assignment- or assessment-level permissions. For instance, authors log in to the system, and for their assigned section of the project, upload text, figures, or other supporting documents. On the other hand, project managers are able to assign authors and reviewers to specific sections. Basic management tools allow project-level analyses, such as progress reports by chapter or by author. Additionally, automatic email notifications (e.g., reminders when assigned submission deadlines are passed) can be generated and sent in the system.

Other key features are a table of contents to visualize the entire publication, an online space dedicated to discussions surrounding each draft assignment (effectively replacing email), and stamps indicating date, time, and author to maintain version control. Version control is an essential component, such that when a new version of any document is submitted, previous versions are saved and available for consultation. They can also be restored if needed. Flexibility is another key feature for management of a project (i.e., monograph volume), so that restructuring or reassignment based on editorial decisions can be handled with ease.

IARC has developed an in-house project management system (IARC 2017c) that responds to these project management needs and provides a single portal for users to access other online tools, such as HAWC and Table Builder. To date, the system has been successfully used for 19 volumes of the IARC Monographs (since Volume 103), 2 volumes of the IARC Handbooks, and several other IARC publications. The review comments and draft manuscripts remain confidential to protect the integrity of the deliberative process.

Conclusion

The importance of systematic review, transparency, and public access to the information on which the decisions on hazards and risks of environmental chemicals are made is now widely appreciated (IOM 2011; NTP 2015a, 2015b; Smith et al. 2016). The software tools designed to facilitate systematic review, as discussed here, are in line with published frameworks and recommendations of various expert advisory groups (NRC 2011; Straif et al. 2014; Woodruff and Sutton 2014; Vandenberg et al. 2016); they have been implemented in multiple case studies (Chappell et al. 2016; Guyton et al. 2018; Molander et al. 2016; NAS 2017; Smith et al. 2016) and are now used routinely by state (Schaefer and Myers 2017), federal (NTP 2015c; NTP 2016a, 2016b, 2016c; U.S. EPA 2017), and international agencies (IARC 2017c). Standardization of the literature search and screening, data analysis, and peer review is an important aspect of human health assessments that can be facilitated and improved through web-based tools. Interoperable web-based tools such as HAWC and Table Builder can thus address the needs for more timely assessments that are quality-controlled and well documented. Together with content management systems, we have found these tools to be collaborative and easy to use, thereby ensuring a transparent workflow. Therefore, we believe these software tools have become indispensable to the review of potential carcinogens.

Acknowledgments

The IARC Monographs Programme is funded by the United States NCI and NIEHS (5U01CA033193) and the European Union (VS/2017/0287). Development of HAWC was supported, in part, by a cooperative agreement with U.S. EPA STAR RD83516602; further development was supported by the NTP. Development of Table Builder was supported by the IARC Monographs Programme and the NTP.

A.S. was the lead developer of HAWC and Table Builder; J.A. was a codeveloper of HAWC and Table Builder. S.A. developed IARC’s content management system. Software concept and design was led by the following: HAWC, A.S., I.R. and K.G.; Table Builder, A.S., N.G., R.L., P.S., G.J., S.M., D.L., and K.G.; IARC's content management system: S.A., N.G., D.L.

Footnotes

Current affiliation: Infinia ML, Durham, North Carolina, USA

Current affiliation: World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Current affiliation: School of Community Health Sciences, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada, USA

I.R.’s laboratory receives funding from National Institutes of Health, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, European Petroleum Refiners Association, and the Foundation for Chemistry Research and Initiatives. A.S. currently works at Infinia ML; however, work conducted at the current position is independent and unrelated to work in this publication.

All other authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

Note to readers with disabilities: EHP strives to ensure that all journal content is accessible to all readers. However, some figures and Supplemental Material published in EHP articles may not conform to 508 standards due to the complexity of the information being presented. If you need assistance accessing journal content, please contact ehponline@niehs.nih.gov. Our staff will work with you to assess and meet your accessibility needs within 3 working days.

References

- Chappell G, Pogribny IP, Guyton KZ, Rusyn I. 2016. Epigenetic alterations induced by genotoxic occupational and environmental human chemical carcinogens: a systematic literature review. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res 768:27–45, PMID: 27234561, 10.1016/j.mrrev.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyton KZ, Rusyn I, Chiu WA, Corpet DE, van den Berg M, Ross MK, et al. 2018. Application of the key characteristics of carcinogens in cancer hazard identification. Carcinogenesis 39(4):614–622, PMID: 29562322, 10.1093/carcin/bgy031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard BE, Phillips J, Miller K, Tandon A, Mav D, Shah MR, et al. 2016. SWIFT-Review: a text-mining workbench for systematic review. Syst Rev 23(87):5, PMID: 27216467, 10.1186/s13643-016-0263-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer). 1973. “Certain Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Heterocyclic Compounds.” IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risk Hum 3; Lyon, France: http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol1-42/mono3.pdf [accessed 11 October 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- IARC. 2017a. “Some Organophosphate Insecticides and Herbicides.” IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risk Hum 112; Lyon, France: http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol112/mono112.pdf [accessed 11 October 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- IARC. 2017b. “DDT, Lindane, and 2,4-D.” IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risk Hum 113; Lyon, France: http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol113/mono113.pdf [accessed 11 October, 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- IARC. 2017c. “Instructions to Authors for the Preparation of Drafts for IARC Monographs.” http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Preamble/previous/Instructions_to_Authors.pdf [accessed 11 October 2018].

- IARC. 2018. IARC Monograph Meetings Homepage. https://monographs.iarc.fr/iarc-monographs-meetings/ [accessed 12 September 2018].

- IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. “Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews.” Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, PMID: 24983062, 10.17226/13059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molander L, Hanberg A, Rudén C, Ågerstrand M, Beronius A. 2016. Combining web-based tools for transparent evaluation of data for risk assessment: developmental effects of bisphenol A on the mammary gland as a case study: combining tools for evaluation of data for risk assessment. J Appl Toxicol, PMID: 27488142, 10.1002/jat.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAS (National Academies of Sciences). 2017. Application of Systematic Review Methods in an Overall Strategy for Evaluating Low-Dose Toxicity from Endocrine Active Chemicals. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, PMID: 28896009, 10.17226/24758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC (National Research Council). 2011. “Review of the Environmental Protection Agency's Draft IRIS Assessment of Formaldehyde.” Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, PMID: 25032397, 10.17226/13142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC. 2014. “Review of EPA's Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Process.” Washington, DC: National Academies Press, PMID: 25101400, 10.17226/18764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NTP (National Toxicology Program). 2015a. Handbook for Preparing Report on Carcinogens Monographs. https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/pubhealth/roc/handbook/index.html [accessed 11 October 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- NTP. 2015b. Handbook for Conducting a Literature-Based Health Assessment Using OHAT Approach for Systematic Review and Evidence Integration. https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/ohat/pubs/handbookjan2015_508.pdf [accessed 11 October 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- NTP. 2015c. “Monograph on Identifying Research Needs for Assessing Safe Use of High Intakes of Folic Acid.” Research Triangle Park, NC: National Toxicology Program; https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/ohat/folicacid/final_monograph_508.pdf [accessed 11 October 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- NTP. 2016a. “Report on Carcinogens: Monograph on Cobalt and Cobalt Compounds that Release Cobalt Ions In Vivo.” https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/roc/monographs/cobalt_final_508.pdf [accessed 11 October 2018]. [PubMed]

- NTP. 2016b. “NTP Research Report: Systematic Literature Review on the Effects of Fluoride on Learning and Memory in Animal Studies.” Research Triangle Park, NC: National Toxicology Program; https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/results/pubs/rr/reports/01fluoride_508.pdf [accessed 11 October 2018]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NTP. 2016c. “NTP Monograph: Immunotoxicity Associated with Exposure to Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS).” Research Triangle Park, NC: National Toxicology Program; http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/ohat/pfoa_pfos/pfoa_pfosmonograph_508.pdf [accessed 11 October 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- NTP. 2018. Report on Carcinogens Process and Listing Criteria. https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/pubhealth/roc/process/ [accessed 10 September 2018].

- Pelch KE, Wignall JA, Goldstone AE, Ross PK, Blain RB, Shapiro AJ, et al. 2017. NTP Research Report on Biological Activity of Bisphenol A (BPA) Structural Analogues and Functional Alternatives. Research Triangle Park, NC: National Toxicology Program; (4): 1–78. https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/results/pubs/rr/reports/rr04_508.pdf [accessed 11 October 2018]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer HR, Myers JL. 2017. Guidelines for performing systematic reviews in the development of toxicity factors. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 91:124–141, PMID: 29080853, 10.1016/j.yrtph.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer G. 2007. meta: An R package for meta-analysis. R News 7(3):p 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro AJ, Addington A, Thacker S, Comeaux J. 2018. Health Assessment Workspace Collaborative (HAWC) Source Code. Zenodo; 10.5281/zenodo.1414621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro AJ, Addington A. 2018. Table Builder Source Code. Zenodo, 10.5281/zenodo.1414623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MT, Guyton KZ, Gibbons CF, Fritz JM, Portier CJ, Rusyn I, et al. 2016. Key Characteristics of Carcinogens as a Basis for Organizing Data on Mechanisms of Carcinogenesis. Environ Health Perspect 124(6):713–721, PMID: 26600562, 10.1289/ehp.1509912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straif K, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y, Lauby-Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, et al. 2014. Future priorities for the IARC Monographs. Lancet Oncol 15(7):683–684, 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70168-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). 2017. “IRIS Today – An update on progress. Presentation given at the EPA Science Advisory Board Chemical Assessment Advisory Committee.” https://yosemite.epa.gov/sab/sabproduct.nsf/a84bfee16cc358ad85256ccd006b0b4b/b993d2c54053cd9a8525817d005fd1e2 [accessed 11 October 2018].

- Vandenberg LN, Ågerstrand M, Beronius A, Beausoleil C, Bergman A, Bero LA, et al. 2016. A proposed framework for the systematic review and integrated assessment (SYRINA) of endocrine disrupting chemicals. Environ Health Perspect 15(1):74, PMID: 27412149, 10.1186/s12940-016-0156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff TJ, Sutton P. 2014. The Navigation Guide systematic review methodology: a rigorous and transparent method for translating environmental health science into better health outcomes. Environ Health Perspect 122(10):1007–1014, PMID: 24968373, 10.1289/ehp.1307175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]