SUMMARY

The epithelial-specific splicing regulators Esrp1 and Esrp2 are required for mammalian development, including establishment of epidermal barrier functions. However, the mechanisms by which Esrp ablation causes defects in epithelial barriers remain undefined. We determined that the ablation of Esrp1 and Esrp2 impairs epithelial tight junction (TJ) integrity through loss of the epithelial isoform of Rho GTP exchange factor Arhgef11. Arhgef11 is required for the maintenance of TJs via RhoA activation and myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation. Ablation or depletion of Esrp1/2 or Arhgef11 inhibits MLC phosphorylation and only the epithelial Arhgef11 isoform rescues MLC phosphorylation in Arhgef11 KO epithelial cells. Mesenchymal Arhgef11 transcripts contain a C-terminal exon that binds to PAK4 and inhibits RhoA activation byArhgef11. Deletion of the mesenchymal-specific Arhgef11 exon in Esrp1/2 KO epithelial cells using CRISPR/Cas9 restored TJ function, illustrating how splicing alterations can be mechanistically linked to disease phenotypes that result from impaired functions of splicing regulators.

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Lee et al. identify defects in epithelial tight junctions when the splicing regulators Esrp1 and Esrp2 are ablated in mouse epidermis. A splicing switch in Arhgef11 transcripts partially underlies these defects through inhibition of the mesenchymal isoform of Arhgef11 by Pak4 and a consequent loss of RhoA activation.

INTRODUCTION

Alternative splicing (AS) is a highly regulated process of gene expression that results in the production of multiple protein isoforms from a single gene. Nearly all human (>90%) pre-mRNA transcripts undergo AS, with an average of 7–8 AS events per multi-exon gene (Pan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008). While recent studies strongly suggest that a large number of AS events lead to alternative protein isoforms, for the vast majority of alternatively spliced transcripts, the functional consequences of AS at the level of protein function remain unknown (Blencowe, 2017). Dysregulation of AS has been shown to lead to numerous human diseases, and thus a better understanding of how inappropriate expression of specific protein isoforms can be associated with specific disease phenotypes is needed (Cieply and Carstens, 2015; Shkreta and Chabot, 2015). However, associating global changes in splicing with the functions of specific cell types or with relevant disease phenotypes remains a major challenge because defining the biological function of even a single AS event can require years of detailed study (Blencowe, 2017). Recent studies have demonstrated that a major impact of AS at the protein level is to alter protein-protein interactions. Alternatively spliced exons encode protein regions that are highly enriched for regions of protein disorder and post-translational modifications, both of which are associated with protein-protein interactions (Buljan et al., 2012; Ellis et al., 2012). Alternative exons with cell- or tissue-specific splicing differences are even more highly enriched for these features, indicating that a major function of tissue-specific AS is to “rewire” protein-protein interaction networks in different cell types to globally affect differential cell functions and properties. A recent large-scale study that examined protein-protein interactions for a panel of alternative isoform pairs confirmed these observations and revealed that AS produces isoforms with vastly different interaction profiles, such that different isoforms often behave as if they arise from completely different genes (Yang et al., 2016a). Therefore, alternatively spliced protein isoforms tend to behave like distinct genes in interactome networks rather than minor variants. A first step toward resolving the functional consequences of AS can begin with the identification of isoform-specific protein interactions, followed by a more detailed analysis of how these altered protein interactions mechanistically affect complexes and pathways that are important for specific cell operations.

AS is largely regulated by RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that function as splicing factors, including a growing list of these factors with cell- or tissue-specific expression (Chen and Manley, 2009). The epithelial splicing regulatory proteins 1 (ESRP1) and 2 (ESRP2) are exquisitely epithelial cell type-specific splicing factors that regulate a large network of alternatively spliced genes involved in cell-cell adhesion, motility, cytoskeletal dynamics, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Dittmar et al., 2012; Warzecha et al., 2009, 2010; Yang et al., 2016b). We previously generated mice with germline and/or conditional knockout alleles for Esrp1 and Esrp2 and showed that they are essential for mammalian development, with important roles in the formation of multiple organs or structures (Bebee et al., 2015). More recently, we also showed that mutations in ESRP1 lead to human hereditary sensorineural hearing loss through structural alterations of the inner ear that mirror those seen in Esrp1 knockout (KO) mouse ears during development (Rohacek et al., 2017). In addition, conditional ablation of Esrp1 and Esrp2 in the epidermis demonstrated that loss of Esrp1 and Esrp2 in the epidermis was postnatal lethal due to excessive water loss and dehydration (Bebee et al., 2015).

The epidermal cells of the skin constitute one of the most important populations of epithelial cells in mammals because the skin provides an essential barrier that acts as the first line of defense protecting the human body against outside environmental and microbial threats. Furthermore, through the formation of the epidermal permeability barrier (EPB), the epidermis limits the flow of water, ions, and other small molecules across epithelial cell layers and prevents water loss and dehydration (Kirschner and Brandner, 2012). Thus, maintenance of the EPB is crucial for survival, and defects in EPB are associated with a number of skin diseases, including inflammatory skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis (Kubo et al., 2012). It is therefore of great relevance to understand the basis of defects in EPB formation and function to identify new therapeutic strategies. Our discovery of a defect in the EPB in Esrp-ablated skin suggested that splicing switches in key Esrp splicing targets underlie this abnormality. The identification of some of these events holds the potential for identifying genes and splice isoform-dependent pathways that are essential for barrier functions in the epidermis, as well as in other epithelial cells that form important cell barriers in other organs such as the gastrointestinal tract and lungs.

The epithelial cells that comprise the epidermis consist of several stratified layers of keratinocytes. The basal layer, or stratum basale, contains epithelial cells abutting the basement membrane and dermis. As these cells differentiate and migrate upward, they give rise to the stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and finally the stratum corneum, which consists of dead corneocytes and lipids that constitute the outermost layer of the skin barrier (Kirschner and Brandner, 2012). Previous studies demonstrated that tight junctions (TJs), located at the stratum granulosum of skin, play an essential role in the maintenance of the EPB to prevent water loss (Furuse et al., 2002; Tunggal et al., 2005). Our previous identification of genes with AS changes in Esrp1;Esrp2 double KO (DKO) epidermis revealed enrichment for transcripts encoding Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) category “Tight Junction,” and we also observed numerous Esrp regulated targets that are associated with and/or involved in the functions of TJs, suggesting that these structures were disrupted in Esrp ablated epidermis. Here, we characterize TJ defects in Esrp ablated epithelial cells in vivo and in vitro and describe a molecular mechanism through which a splicing switch in Arhgef11 transcripts partially underlies these defects.

RESULTS

Esrp1 and Esrp2 Are Required for Structural TJ Integrity In Vivo and In Vitro

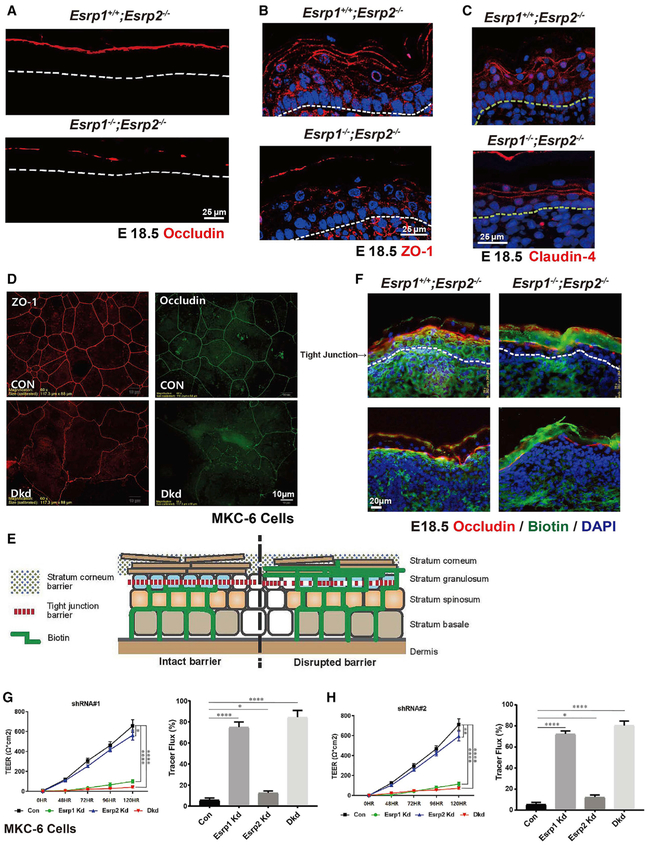

Our previous observation of dry skin and lethal water loss in newborn pups after conditional Esrp1;Esrp2 ablation in the epidermis prompted further inquiry into the etiology of this barrier defect. TJs are composed of two groups of proteins. Adaptor proteins (e.g., ZO-1) connect the cytoskeleton to the junctional membrane and provide protein-protein interaction through scaffolding function. The transmembrane proteins (Occludin and Claudins) link these adaptor proteins and mediate cell-cell adhesion (Zihni et al., 2016). We performed immunofluorescence for TJ proteins in Esrp1+/+;Esrp2−/− controls and Esrp DKO (Esrp1−/−;Esrp2−/−) littermates at embryonic day (E)18.5. Occludin specifically stains at the granular cell layer where the TJs are located. We noted the expected pattern of continuous linear staining for Occludin in control embryos, whereas in DKO epidermis we noted discontinuous staining, suggesting areas of disrupted TJs (Figure 1A). ZO-1 and Claudin-4 staining was observed throughout the epidermal layers, as noted in previous studies (Furuse et al., 2002), and while staining for ZO-1 appeared slightly discontinuous, these stains primarily showed a reduced thickness of the hypoplastic epidermis, as originally observed on H&E staining (Bebee et al., 2015) (Figures 1B and 1C). Of note, we used Esrp1+/+;Esrp2−/− embryos as controls from the same litters as Esrp1−/−;Esrp2−/− embryos because Esrp1 and Esrp2 are both highly expressed in the epidermis and Esrp2−/− mice have no observable phenotypes (Bebee et al., 2015). Moreover, epidermis from Esrp2−/− mice displays no histologic abnormalities or defects in Occludin staining in Esrp2−/− epidermis compared to wild-type epidermis (Figures S1A and S1B). Next, to examine whether Esrp1 is required for TJ structural formation in vitro, we examined ZO-1 and Occludin immunofluorescence following calcium-induced TJ assembly in cells, which followed short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated Esrp1 and Esrp2 depletion (double knockdown [DKD]) compared to non-targeting shRNA controls (Con) in the mouse MKC-6 keratinocyte cell line. Whereas control cells showed continuous staining along cell junctions, these TJ markers were disrupted following Esrp1 and Esrp2 depletion and showed increased diffuse localization throughout the cytoplasm (Figure 1D). These data demonstrate that the Esrps are essential for structural integrity at cell-cell junctions in vivo and in vitro.

Figure 1. Esrp Ablation in Mouse Epidermis or Depletion in Keratinocytes Disrupts Tight Junctions and the Permeability Barrier.

(A–C) Immunostaining for Occludin (A), ZO-1 (B), and Claudin-4 (C) in Esrp1−/−;Esrp2−/−DKO (double knockout) and control Esrp1+/+;Esrp2−/− epidermis showing disrupted Occludin continuity at the stratum granulosum (SG) layer. DAPI (blue).

(C) Claudin-4 staining showing reduced thickness of DKO epidermis compared to the control.

(D) Immunofluorescence localization of tight junction (TJ) markers in the mouse MKC-6 keratinocytes cell line 96 hr after a calcium shift. Analysis was done in cells transduced with a control non-targeting shRNA or shRNAs targeting Esrp1 and Esrp2.

(E) Schematic representing the paracellular biotin permeability assay.

(F) Control (Esrp1+/+;Esrp2−/−) or Esrp DKO (Esrp1−/−;Esrp2−/−) E18.5 mouse embryo skin injected intradermally with biotin was stained with streptavidin to follow the penetration of biotin (green) and counterstained with TJ marker Occludin (red) and DAPI (blue) to mark the TJs in the SG layer.

(G and H) Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was measured across confluent control, Esrp1, Esrp2, or Esrp1/2 shRNA knockdown MKC-6 keratinocyte cell monolayers stimulated with calcium for the indicated times suing Esrp1 shRNA#1 (G) and Esrp1 shRNA#2 (H). (G) and (H) used different Esrp1 shRNAs. Tracer flux of 4kDa FITC-dextran in control or Esrp depleted keratinocyte cells is indicated as percent tracer flux relative to a transwell with no cells.

Error bars indicate means ± SDs, n = 3. Statistical significance comparing each group with control was determined by t test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ****p < 0.0001.

Ablation or Depletion of the Esrps Results in Increased Permeability through TJs

The water loss phenotype and alterations in TJ markers in Esrp1−/−;Esrp2−/− pups suggested an “inside-out” permeability defect similar to other mouse models associated with defective TJs (Furuse et al., 2002; Gladden et al., 2010; Tunggal et al., 2005). To further establish that the water loss in Esrp1−/−;Esrp2−/− DKO epidermis was due to a defect in the TJ-based permeability, we used previously described assays for TJ functional integrity (Schmitz et al., 2015). In normal mouse skin, sulfo-N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)-biotin injected into the dermis will diffuse into the epidermis, but will be halted at the TJs located at the stratum granulosum (marked with Occludin staining) and prevented from leaking into the stratum corneum (Figure 1E). In control E18.5 embryos after labeling biotin with streptavidin, we noted the expected restriction of diffusion across TJs labeled with Occludin. In Esrp1−/−;Esrp2−/− DKO epidermis, we observed that biotin was able to diffuse across the granular cell layer into the stratum corneum, indicating a permeability defect at the level of epidermal TJs (Schmitz et al., 2015) Figure 1F). The stratum corneum comprises another component of the epidermal barrier that is commonly associated with an “outside-in” barrier function to protect against pathogens and chemical insults. The toluidine blue penetration assay is commonly used to identify outside-in permeability defects that are presumed to arise from defects in the function of the stratum corneum (Schmitz et al., 2015). We did not observe differences in toluidine penetration between control and Esrp1−/−;Esrp2−/− DKO embryos, suggesting that the stratum corneum in Esrp-ablated skin was intact in forming the outside-in barrier, similar to previous observations in E-cadherin KO skin that also showed defective TJs (Tunggal et al., 2005) (Figure S1C).

In cultured monolayer cells in vitro transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran flux assays are commonly used to assess TJ functions to restrict paracellular passage of water, ions, and other small molecules after calcium-induced TJ assembly (Yuki et al., 2007). We measured TEER across confluent cell cultures after control, Esrp1-, Esrp2-, or Esrp1/2-specific shRNA knockdown using mouse MKC-6 keratinocyte cell monolayers that had been stimulated with calcium. Control keratinocytes developed a progressive increase in electrical resistance after calcium stimulation. Whereas Esrp2 knockdown (KD) cells showed a negligible decrease in TEER, KD of either Esrp1 alone or of Esrp1 and Esrp2 caused a profound reduction in TEER across the time course using two different shRNAs against Esrp1 (Figures 1G and 1H). Similarly, depletion of Esrp1 or Esrp1 and Esrp2 led to an appreciable increase in flux of 4-kDa FITC-dextran across cell monolayers, further indicating defects in monolayer paracellular permeability and barrier function (Figures 1G and 1H).

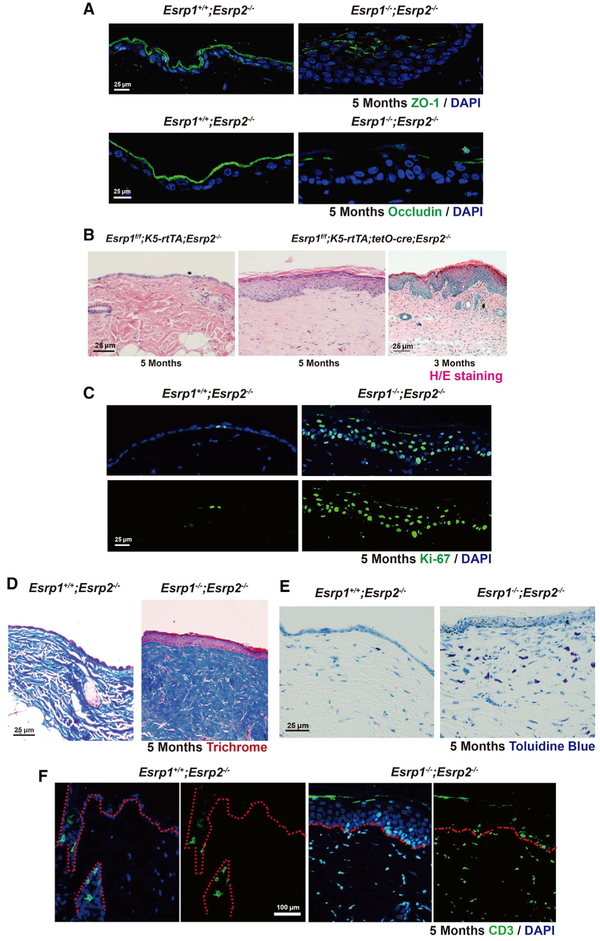

Inducible Ablation of the Esrps Postnatally Is Associated with Altered TJs, Inflammation, and Hair Loss

To identify possible defects in epidermal barrier function in adult skin, we used Esrp1f/f; K5-rtTA;Esrp2−/−;tetO-Cre mice to induce Esrp ablation postnatally. We induced Esrp ablation by providing doxycycline chow to nursing mothers and subsequently maintained weaned mice with doxycycline chow to maintain Esrp ablation. Initially, Esrp1f/f; K5-rtTA;Esrp2−/−mice without tetO-Cre were used as controls. Adult Esrp DKO mice showed variable degrees of hair loss starting at 2 months, as well as variable degrees of inflammatory skin lesions on the back skin (Figure S2A) and weight loss (data not shown). TJ marker ZO-1 and Occludin staining revealed that inducible Esrp DKO (Esrp1f/f; K5-rtTA;tetO-Cre;Esrp2−/−) mice consistently also have altered TJ morphology (Figure 2A). Common inflammatory skin disorders, such as and psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, have been associated with the epidermal TJ defects and characterized by epidermal hyperplasia, hyperproliferation in epidermal keratinocytes, and pronounced infiltration of inflammatory cells (De Benedetto et al., 2011; Kirschner and Brandner, 2012). To further explore postnatal Esrp function in epidermal barrier function, we histologically examined Esrp1f/f; K5-rtTA; tetO-Cre;Esrp2−/− DKO skin. These mice showed epidermal hyperplasia and altered morphology of the underlying dermis that resembled fibrosis histologically when analyzed at 3 or 5 months of age (Figure 2B). We noted that Ki-67+ cells were increased in epidermal keratinocytes from DKO epidermis compared to controls, indicating increased keratinocyte proliferation (Figure 2C). We did not observe any overt differences in cleaved caspase-3+ cells in the DKO epidermis compared to controls, indicating no significant apoptosis in DKO skin (data not shown). Masson’s trichrome staining revealed altered patterns of collagen deposition in the dermis that was also consistent with fibrosis and scarring as commonly observed with defects in the epidermal barrier and inflammation in other mouse models (Augustin et al., 2013; Sevilla et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2010) (Figure 2D). To further control for Cre toxicity, leakiness, and doxycycline effects, we also examined the epidermis in Esrp1f/f;K5-rtTA;tetO-Cre;Esrp2− mice that were not given doxycycline and Esrp1f/+; K5-rtTA; tetO-Cre;Esrp2−/− mice that were given doxycycline; neither displayed visual or histologic abnormalities of the skin or hair, indicating that the defects observed were due to Esrp ablation (Figures S2B and S2C).

Figure 2. Postnatal Induction of Esrp Ablation in the Epidermis Leads to Disrupted TJ, Epidermal Thickening, Inflammation, and Scarring.

(A) Control (Esrp1f/f; K5-rtTA;Esrp2−/−) or Esrp DKO (Esrp1f/f; K5-rtTA;tetO-Cre;Esrp2−/−) 5-month-old skin immunostained for ZO-1 and Occludin (green).

(B) Longitudinal paraffin section from mice back skin of control and Esrp1f/f; K5-rtTA;tetO-Cre;Esrp2−/− mice. H&E stain reveals that Esrp ablation causes hyperthickening of the epidermis.

(C) Ki-67 proliferation assay. Ki-67+cells (green) and DAPI (blue).

(D) Masson’s trichrome stain indicates a high amount of collagen deposition and fibrosis in Esrp DKO epidermis.

(E) Toluidine blue stain shows an increased number of mast cells (dark blue) in Esrp DKO dermis compared to control.

(F) Immunofluorescence of cytokine marker CD3 (green) showed increased CD3+in the Esrp DKO dermis.

Disrupted TJ barriers have been associated with antigen penetration into the dermis, causing immune system activation and inflammation (Kubo et al., 2012). Antigen exposure activates immune cells such as mast cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and T cells (Pasparakis et al., 2014). We observed increased populations of activated mast cells in Esrp DKO dermis based on toluidine staining (Figure 2E). There was also a notable increase in CD3+ cells in the Esrp DKO dermis as well as epidermis (Figure 2F), indicating that the epidermal barrier defect associated with Esrp ablation leads to T cell infiltration. We did not observe differences in macrophage numbers in DKO skin based on F4/80 staining (data not shown). Thus, although Esrp ablation following epidermal differentiation is not lethal, it is associated with altered TJ function and progressive inflammation and scarring.

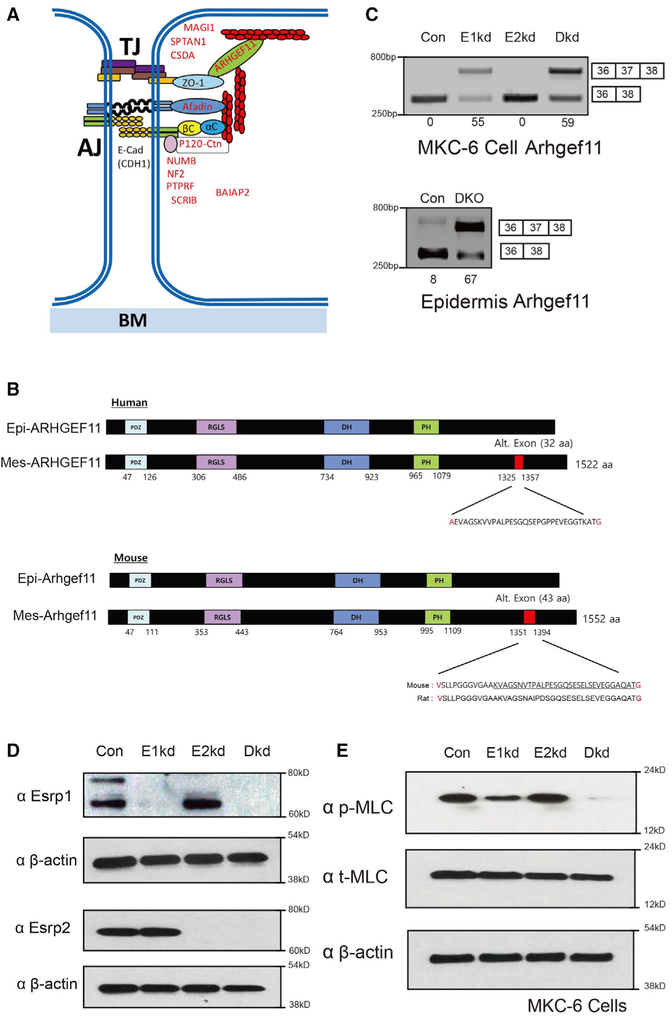

Depletion of Esrps Is Associated with a Reduction in Myosin Light Chain Phosphorylation

Our previous studies identified large-scale changes in AS of Esrp target transcripts that are enriched for functions associated with epithelial development, including TJs. We further noted a number of Esrp-regulated targets that encode proteins that are either associated with components of epithelial TJs or involved in their regulation based on published data (Bebee et al., 2015) (Figure 3A). Arhgef11 was among the Esrp-regulated targets involving exon 37, which is included in mesenchymal cells but skipped in epithelial cells (Itoh et al., 2017; Shapiro et al., 2011). Esrp depletion in MKC-6 cells or ablation in the epidermis induces a switch from the epithelial to the mesenchymal Arhgef11 isoform (Bebee et al., 2015; Rohacek et al., 2017) (Figures 3B–3D). ARHGEF11 is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for RhoA that localizes to the TJ via a direct interaction with the TJ-associated scaffold protein ZO-1 (also known as TJ protein 1 [TJP1]) (Itoh et al., 2012). TJs associate with the actomyosin cytoskeletal structure referred to as the perijunctional actomyosin ring (PJAR), which encircles epithelial cells in a belt-like manner and plays an essential role in maintaining permeability barriers in epithelial cells through the maintenance of adherens junctions and TJs (Ivanov, 2008; Turner, 2000). Through its association with ZO-1, ARHGEF11 induces myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation to promote the assembly of TJs and the PJAR (Itoh, 2013). This activity is most likely due to localized RhoA activation as guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound RhoA activates the phosphorylation of MLC, which induces actin filaments to form a functional contractile actomyosin ring that is required for epithelial cell TJ integrity (Nusrat et al., 1995). Consistent with an important role of ARHGEF11 in epithelial barrier and TJ function, a substantial reduction in TEER was observed following a calcium shift, when it was depleted in an epithelial cell line (Itoh et al., 2012). We hypothesized that a switch in Arhgef11 splicing may contribute to the epithelial barrier defect by altering RhoA activation and MLC phosphorylation. We noted that Esrp1 depletion in the MKC-6 keratinocyte cell line induces a reduction in MLC phosphorylation, and the combined depletion of Esrp1 and Esrp2 nearly abolished MLC phosphorylation, whereas Esrp2 depletion alone showed no apparent effect, correlating with the degree to which each depletion induced a splicing switch in Arhgef11 (Figure 3E). These data indicated that the defects in TJ function at epithelial cell barriers of Esrp depleted cells are associated with reduced MLC phosphorylation and suggested that differential functions of Arhgef11 may underlie this defect.

Figure 3. Depletion of Esrp1 and Combined Depletion of Esrp1 and Esrp2 Leads to Progressive Reduction in Phosphorylation of Myosin Light Chain in Keratinocytes.

(A) Schematic of proteins encoded by alternative splicing targets of Esrps that are associated with tight junctions and/or adherens junctions.

(B) Schematic of human and mouse Arhgef11 epithelial and mesenchymal protein isoforms resulting from inclusion of or skipping exon 37. The amino acid positions are indicated along with the sequence encoded by the alternative exon. The mouse and rat amino acid sequences are underlined to indicate the similar 32 amino acids in human and rodent isoforms, in which the additional upstream 11 amino acids result from the use of an upstream 3′ splice site in the mouse sequence compared to the human gene. Amino acids in red indicate those that differ, depending on whether the exon is spliced or skipped.

(C) RT-PCR analysis of Arhgef11 exon 37 splicing in control Kd, Esrp1 Kd, Esrp2 Kd, and combined Esrp1;Esrp2 Kd cells. Values for exon 37 percentage spliced in (PSI) are indicated beneath each lane. Also seen is RT-PCR showing increased exon splicing in Esrp1−/−;Esrp2−/−epidermis compared to control wild-type epidermis.

(D) Western blot validation of knockdown efficiency.

(E) Reduced phosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC) in MKC-6 cells depleted for Esrp1, and combined Esrp1;Esrp2 ablation compared to control or Esrp2 depleted cells by immunoblotting.

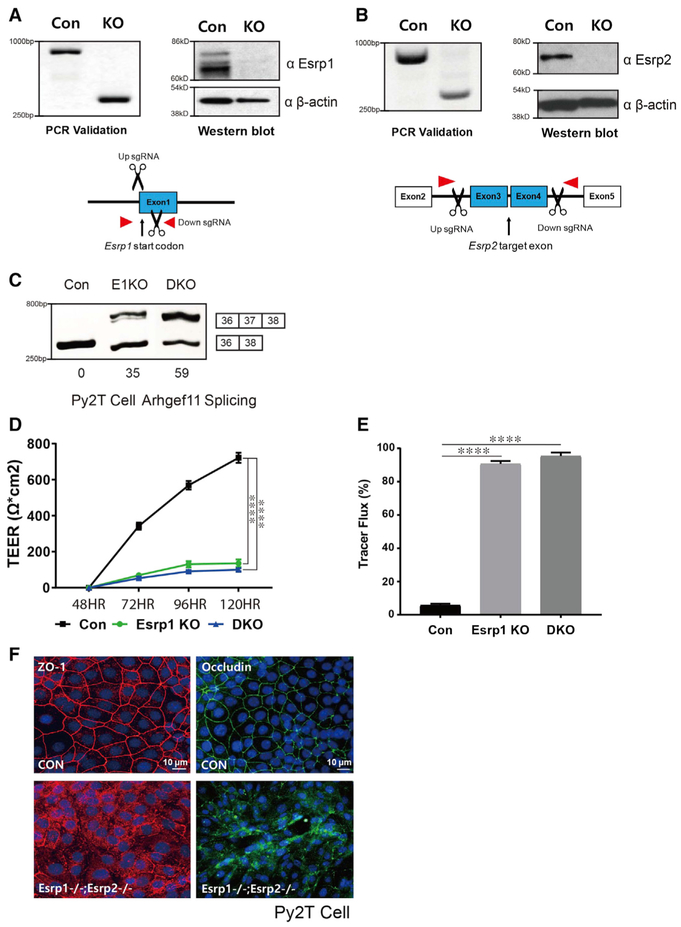

Epithelial Arhgef11 Isoforms Are More Effective in MLC Phosphorylation and Restoration of Epithelial Cell Barriers through More Efficient Activation of RhoA

To further investigate the TJ defects in epithelial cells, we used CRISPR/Cas9 technology to induce complete gene ablations. Due to the technical shortcomings of mouse keratinocytes, we were unable to achieve effective KO in the MKC-6 or other mouse keratinocytes. We therefore used the Py2T mammary epithelial cell line that was amenable to CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene ablation and that is a viable model system to further investigate the role of Esrps specifically in functions of epithelial TJs (Waldmeier et al., 2012). To carry out a more detailed analysis of the role of Esrps and Arhgef11 in TJ function, we generated Py2T Esrp1 KO cells, double Esrp1 and Esrp2 KO (DKO) cells, and cells with KO of Arhgef11. We isolated clones in which we confirmed complete KO of Esrp1, Esrp2, and Arhgef11 both by PCR and western immunoblotting (Figures 4A, 4B, and 5A). Similar to our analyses in MKC-6 keratinocytes, we noted that ablation of Esrp1 alone as well as of Esrp1 and Esrp2 impaired barrier function as measured by both TEER and FITC-dextran tracer flux assays (Figures 4D and 4E). These differences in TEER and dextran flux were not due to differences in cell proliferation or density, as we noted no apparent differences in cell numbers between control and Esrp1;Esrp2 DKO cells once cells reached confluence at 48 hr in the presence of calcium (Figure S3). Immunofluorescence for Occludin and ZO-1 demonstrated disrupted staining of these TJ markers in Esrp1;Esrp2 DKO cells and relocalization to the cytoplasm as observed in MKC-6 cells after Esrp depletion (Figure 4F). In addition, we confirmed that ablation of Esrp1 or Esrp1 and Esrp2 induced splicing of mesenchymal exon 37 (Figure 4C). Arhgef11 ablation also impaired TEER, which is consistent with the previous report using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and increased FITC-dextran tracer flux (Itoh et al., 2012) (Figures 5B and 5C). Ablation of Arhgef11 largely abolished MLC phosphorylation, as also previously shown following siRNA-mediated Arhgef11 depletion (Figure 5D). To explore whether MLC phosphorylation may be differentially affected by the epithelial versus mesenchymal Arhgef11 isoforms, we transfected cDNAs encoding FLAG-tagged proteins of each isoform to rescue Arhgef11 KO cells. We noted that the epithelial ARHGEF11isoform (Epi Rescue) restored MLC phosphorylation, whereas the mesenchymal isoform (Mes Rescue) did so only partially (Figure 5D). These findings suggested that the epithelial isoform was able to more efficiently activate RhoA via GTP loading. We therefore used the RhoA activation assay with the Rho GTP-binding domain (RBD) of Rhotekin fused with glutathione S-transferase (GST) (Reid et al., 1996). We used lysates from Py2T cells transfected with cDNAs for the epithelial or mesenchymal ARHGEF11 isoforms in GST pulldowns of RhoGTP and immunoblotted for RhoA. These experiments demonstrated that the epithelial isoform was more effective in RhoA activation than the mesenchymal isoform (Figure 5E). Similarly, we noted that the epithelial isoform was able to partially restore barrier function in TEER and FITC dextran assays, whereas the mesenchymal isoform was less efficient (Figures 5F and 5G). While these experiments were carried out using cDNAs for the human ARHGEF11 isoforms, we observed the same preferential rescue of TEER and tracer flux using cDNAs encoding the corresponding mouse Arhgef11 isoforms (Figure S4).

Figure 4. Generation of CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Esrp KO in Epithelial Cells.

(A and B) Schematics and validation using CRISPR/Cas9 to ablate Esrp1 (A) and Esrp2 (B) in Py2T cells at the level of genomic DNA and protein by western blot. For Esrp1, a Cas9 nickase strategy was used to target the Esrp1 start codon region, whereas standard Cas9 was used to delete exons in Esrp2 that would disrupt the reading frame.

(C) RT-PCR analysis of Arhgef11 exon 37 splicing in control, Esrp1−/− knockout (KO), Esrp1−/−; Esrp2−/− DKO Py2T cells. Values for exon 37 percentage spliced in (PSI) are indicated beneath each lane.

(D) TEER was measured across confluent control or KO epithelial cell monolayers that had been stimulated with calcium for the indicated times.

(E) FITC-dextran tracer flux of control, Esrp1 KO, or Esrp1/2 DKO epithelial cells. Error bars indicate means ± SDs, n = 3. Statistical significance comparing each group with control was determined by t test. ****p < 0.0001.

(F) Disrupted Occludin localization in Esrp1−/−;Esrp2−/− DKO Py2T epithelial cells after Ca2+ switch.

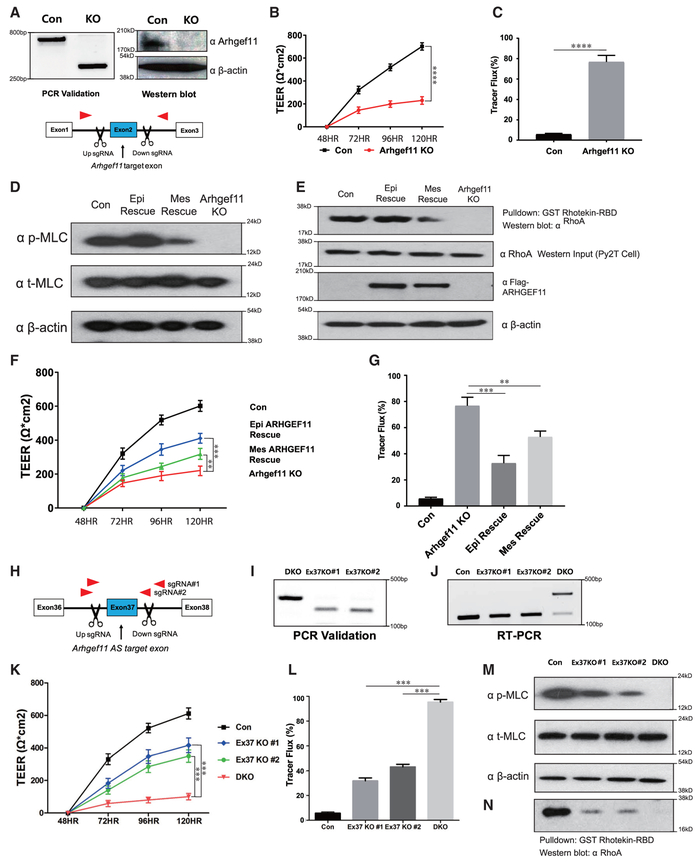

Figure 5. Epithelial ARHGEF11 Isoforms Preferentially Rescue MLC Phosphorylation and Tight Junction Function in Arhgef11 KO Epithelial Cells.

(A) Schematics and validation using CRISPR/Cas9 to ablate Arhgef11 in Py2T cells at the level of genomic DNA and protein by western blot.

(B and C) TEER (B) and FITC-dextran tracer flux (C) in control or Arhgef11 KO epithelial cell monolayers after calcium switch. Error bars indicate means ± SDs, n = 3. Statistical significance comparing each group with control was determined by t test. ****p < 0.0001.

(D) Immunoblot showing that transfection of a cDNA for the epithelial ARHGEF11 isoform rescue (Epi Rescue) restores phosphorylation of MLC in Arhgef11 KO Py2T cells, whereas a cDNA encoding the mesenchymal ARHGEF11 isoform (Mes Rescue) shows reduced recovery.

(E) RhoA activity assay (Rhotekin assay) showing a higher level of active RhoA GTP in KO cells rescued with the epithelial isoform compared to the mesenchymal isoform. Equal levels of total RhoA are indicated by western blot. Immunoblot showing equal Epi- and Mes-ARHGEF11 protein expression in transfected Py2T cells.

(F and G) TEER (F) and FITC-dextran flux (G) assay shows greater rescue with the epithelial ARHGEF11 isoform compared to the mesenchymal isoform. Error bars indicate means ± SDs, n = 3. Statistical significance comparing Epi and Mes Rescue with ARHGEF11KO was determined by t test. **p < 0.005; ***p < 0.001.

(H) Schematic of CRISPR/Cas9 strategy to ablate Arhgef11 alternative splicing (AS) exon37 in Esrp1;Esrp2 DKO Py2T cells using 2 different sgRNA pairs.

(I and J) Validation of exon 37 deletion in genomic DNA by PCR (I) and restoration of the epithelial pattern of Arhgef11 splicing by RT-PCR (J).

(K and L) TEER (K) and FITC-dextran flux (L) assays showing partial rescue of tight junction integrity with conversion of endogenous Arhgef11 from predominantly the mesenchymal-to-epithelial pattern in Esrp1;Esrp2 DKO cells. Error bars indicate means ± SDs, n = 3. Statistical significance comparing exon 37 deletion in DKO cells was determined by t test. ***p < 0.001.

(M) Deletion of Arhgef11 exon 37 partially rescues MLC phosphorylation in Esrp1;Esrp2 DKO Py2T cells.

(N) RhoA activity assays showing that deletion of Arhgef11 exon 37 partially restores RhoA activation in Esrp1;Esrp2 DKO cells.

Deletion of Arhgef11 Mesenchyme-Specific Exon 37 in Esrp1;Esrp2 DKO Epithelial Cells Rescues TJ Function and MLC Phosphorylation by Abrogating an Interaction with Inhibitory Pak4

To test more directly whether the isoform switch in Arhgef11 contributed to the barrier defect in Esrp ablated epithelial cells, we used CRISPR/Cas9 to delete exon 37 in Esrp1;Esrp2 DKO Py2T cells. We isolated 2 clones using 2 independent single guide RNA (sgRNA) pairs in which we confirmed exon 37 deletion by PCR and reversion of splicing toward the epithelial isoforms by RT-PCR (Figures 5H–5J). This switch in endogenous Arhgef11 splicing was able to partially restore barrier function in vitro to Esrp1;Esrp2 DKO cells using TEER and FITC-dextran assays (Figures 5K and 5L). In addition, we determined that deletion of exon 37 partially restored MLC phosphorylation and RhoA activation to Esrp ablated cells (Figures 5M and 5O). Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that the epithelial isoform of Arhgef11 is more effective than the mesenchymal isoform in maintaining epithelial cell barriers due to increased MLC phosphorylation in response to RhoA activation, and they strongly suggest that this isoform switch in Esrp depleted or ablated cells contributes to the loss of MLC phosphorylation altered barrier function. A direct interaction of ARHGEF11 with ZO-1 was previously shown to be mediated by a C-terminal region of ARHGEF11 in a region where the Esrp-regulated alternative exon is located, suggesting that differential binding to ZO-1 may account for their differential activities. However, in immunoprecipitations from 293T cells transiently transfected with FLAG-tagged cDNAs of both isoforms, we observed that both isoforms bound ZO-1 at apparent similar levels of efficiency (Figure 6A). We also generated both 293T and Py2T cells stably expressing either the epithelial or mesenchymal isoform of ARHGEF11 and similarly noted that both interacted with ZO-1 in pulldown assays (Figure S5). We noted that the alternative exon was not located within or near any canonical domains in ARHGEF11, including the Rho binding Dbl homology (DH) domain (see Figure 3B). We therefore explored protein interaction databases and the literature to identify candidate protein-protein interactions with Arhgef11 that may be isoform specific in the regulation of its activity. Our literature search uncovered an interaction of p21-activated kinase 4 (PAK4) with ARHGEF11 that was detected by co-immunoprecipitation, as well as a yeast 2-hybrid screen for proteins interacting with the C-terminal domain of ARHGEF1, which had been shown to have GEF inhibitory functions (Barac et al., 2004; Huttlin et al., 2015). A C-terminal region of ARHGEF11 (amino acids 1081–1523 in the reference mesenchymal isoform) was confirmed to be sufficient for PAK4 binding in 293T cells (Barac et al., 2004). This study demonstrated that PAK4 binding resulted in serine and threonine phosphorylation of ARHGEF11 and inhibited RhoA activation. Because this C-terminal domain included the Esrp-regulated exon, we tested whether there was a difference in binding to PAK4 by the epithelial and mesenchymal isoforms that may also account for decreased RhoA activation by the mesenchymal isoform. We transfected 293T cells with cDNAs for FLAG-tagged human epithelial and mesenchymal ARHGEF11 isoforms followed by anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation. We noted that the mesenchymal but not the epithelial isoform was able to efficiently immunoprecipitate (IP) endogenous PAK4 (Figures 6B, 6C, and S6). We also showed that there was preferential association of the epithelial isoform with RhoA using an antibody that recognizes both activated and unactivated forms of RhoA (Figure 6C). Reverse co-IP of endogenous PAK4 followed by immunoblotting for FLAG-tagged ARHGEF11 in transfected cells confirmed the preferential association of PAK4 with the mesenchymal isoform (Figure 6C). We also demonstrated that ectopic expression of the epithelial ARHGEF11 isoform in these cells was associated with higher levels of activated RhoA (Figures 6D and S6). To confirm the isoform-specific interaction of Arhgef11 with Pak4 in vivo, we used the mammalian protein-protein interaction trap (MAPPIT) assay. In this assay, protein bait-prey interacting pairs are able complement a signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-dependent reporter with a luciferase-based readout for positive protein-proteins interactions (Eyckerman et al., 2001). We used the previously established framework for scoring positive interactions by calculating the experimental-to-control ratio (ECR), as described previously and in Method Details (Venkatesan et al., 2009). Using this assay, we verified that PAK4 directly interacts with mesenchymal ARHGEF11 but not with epithelial ARHGEF11 in vivo (Figure 6E). These results indicate that PAK4 binding to the mesenchymal isoform of ARHGEF11 inhibits its ability to activate RhoA and induce MLC phosphorylation to maintain TJ integrity and function (Figure 6F).

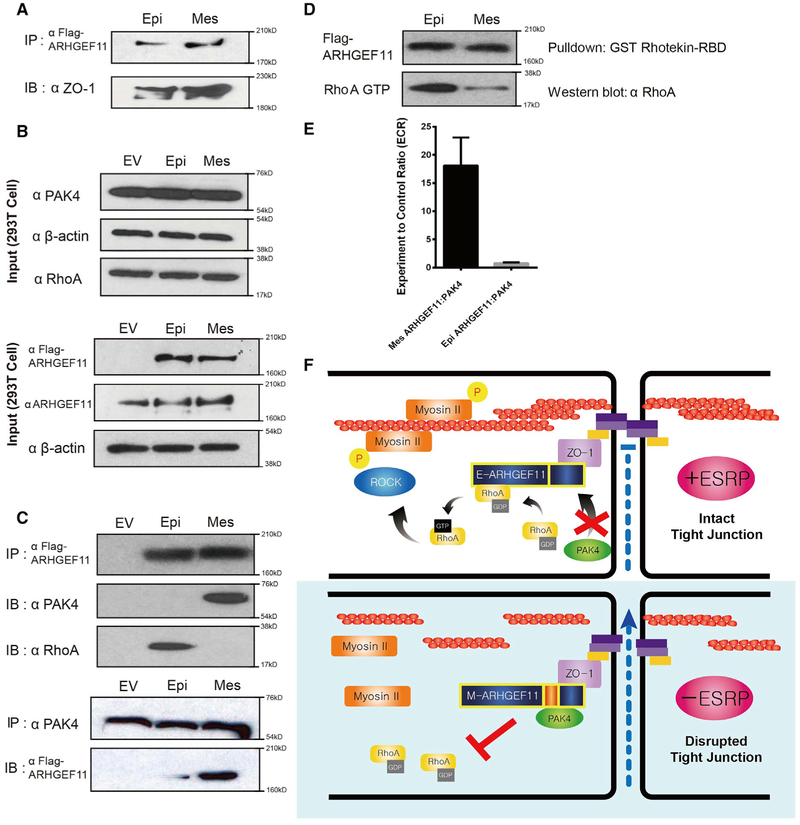

Figure 6. Differential Binding of the Mesenchymal Isoform of ARHGEF11 to Inhibitory PAK4 Leads to Reduced RhoA Activation Compared to the Epithelial Isoform.

(A) FLAG-Arhgef11 isoforms transfected in 293T cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoblotted for ZO-1, demonstrating equivalent ZO-1 binding.

(B) Western immunoblots showing levels of the indicated proteins in input samples.

(C) Transfected FLAG-Arhgef11 isoforms were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoblotted for p21-activated kinase 4 (PAK4) and RhoA. Immunoprecipitation of endogenous PAK4 confirms preferential binding to the mesenchymal ARHGEF11 isoform.

(D) RhoA activity assay reveals that Epi-Arhgef11 more efficiently activates RhoA than Mes-Arhgef11 when overexpressed in 293T cells.

(E) The mesenchymal but not the epithelial isoform of ARHGEF11 binds to PAK4 in the MAPPIT assay. The experimental-to-control ratio (ECR) is calculated from luciferase readings as outlined in Method Details. Error bar represents SD. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

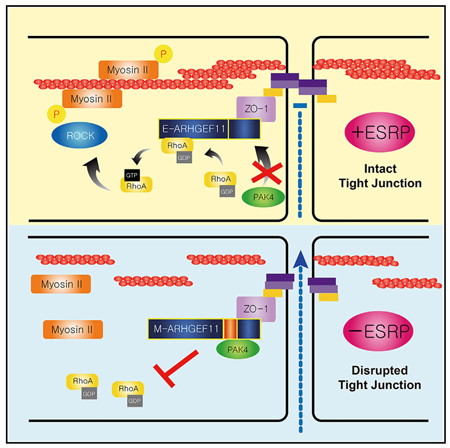

(F) Schematic of model by which the epithelial isoform of ARHGEF11 maintains the PJAR as a result of reduced binding to inhibitory PAK4.

DISCUSSION

In the past 10 years, technological advances have led to the identification of large-scale AS networks in different cell types and those that are controlled by specific splicing factors, including cell- or tissue-specific regulators. It has been shown that these networks regulate splicing in sets of genes that function in common or related pathways and processes that maintain important cellular phenotypes. The importance of cell type-specific splicing has been further demonstrated by the identification of pathologies that result when splicing factors, particularly those expressed in neurons and/or muscle such as Nova, Srrm4, Rbfox, and Mbnl, are ablated in mice (Gehman et al., 2011; Jensen et al., 2000; Kalsotra et al., 2008; Nakano et al., 2012). However, it remains a major challenge to determine which splicing changes observed in these tissues following splicing factor ablation give rise to these disease-related phenotypes. The functional characterization of different protein isoforms that result from AS holds promise both for identifying genes that are also associated with human disease and to further dissect molecular mechanisms that relate to the phenotypes observed when specific splicing factors are inactivated. The identification of isoform-specific protein-protein interactions and cellular assays related to specific phenotypes can be used to begin to interrogate gene functions at the exon level. While germline deletion of Esrp1 with or without Esrp2 was associated with defects in multiple organs and tissues, conditional deletion of Esrp1 and Esrp2 in the skin was associated with an epidermal barrier defect. In this study, we established that this phenotype is due at least in part to a disruption in the organization of TJs and in their ability to restrict the flow of ions and water across these cell-cell adhesion complexes. While germline ablation of Esrp1 and Esrp2 was associated with hypoplastic epidermis and lethality, the induction of gene ablation postnatally after the completion of embryonic skin development was not lethal, but it did lead to altered TJ morphology and inflammation. Similar chronic changes have been previously observed in other models of epidermal barrier defects (Yang et al., 2010).

The TEER and tracer flux assays provided a means to begin to interrogate Esrp regulated transcripts for their role in the maintenance of epithelial cell integrity. Previous studies identified Arhgef11 as an interacting partner with the TJ protein ZO-1 and noted that its depletion led to the disruption of TJs through abrogation of MLC phosphorylation. We therefore investigated whether this important role of Arhegf11 in epithelial cells was more robustly carried out by the epithelial isoform than the mesenchymal isoform that is induced by ablation of the Esrps. While both isoforms interacted with ZO-1, we determined that the mesenchymal but not the epithelial Arhgef11 isoform interacts with PAK4, which inhibits RhoA activation. Reduced RhoA activation observed in Esrp KO cells leads to a reduction in MLC phosphorylation, which reduces contraction of the PJAR and disrupts TJs. Consistent with this model, ectopic expression of the epithelial ARHGEF11 isoform was more efficiently able to restore TJ function in Arhgef11 KO cells than the mesenchymal isoform, as assessed by TEER and tracer flux assays. While the mesenchymal isoform was also able to partly restore TEER and inhibit tracer flux, we suspect that this was in part due to higher levels of expression than the endogenous protein, which likely was able to overcome inhibition by PAK4 by a titration effect (Figures 5F and 5G). When we converted endogenous Arhgef11 splicing back to exclusive production of epithelial isoforms in Esrp1;Esrp2 DKO cells, we observed a partial rescue of barrier function. However, this partial rescue also indicates that the altered splicing of Arhgef11 alone is not the only splicing change that accounts for the disruption of the TJs in the epidermis. Further assays of TJ function of other Esrp regulated targets will likely uncover additional genes that contribute to the maintenance of these important dynamic structures through the activity of epithelial-specific isoforms. Several of these targets, such as Nf2 and Arhgap17, have previously been shown to have important roles in the maintenance of epithelial barriers, and it is possible that these functions are preferentially carried out by epithelial isoforms (Gladden et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2016). We note that a recent study also described differential activities of the same isoforms of ARHGEF11, showing that the mesenchymal but not the epithelial isoform promoted cell migration and invasion in mesenchymal cells (Itoh et al., 2017). These findings are consistent with observations that TJs are disrupted during the EMT and our findings showing an important role for the epithelial ARHGEF11 isoform in TJ maintenance. We note, however, that this study presented a model wherein the epithelial but not the mesenchymal isoform interacted with ZO-1, in contrast to our findings. While we cannot definitively account for our different findings, we note that their study used cotransfection of cDNAs of ARHGEF11 cDNAs and a GFP fusion with a partial ZO-1 derived protein sequence. In our studies, we showed that both isoforms were able to co-IP endogenous ZO-1 (Figure 6A). Furthermore, we also showed that both isoforms were able to co-IP endogenous ZO-1 when stably expressed in both 293T cells and the mouse epithelial Py2T cell line (Figure S5).

Our study provides further evidence of the role AS plays in important cell functions via the regulation of differential protein-protein interactions and illustrates an example whereby the expression of an epithelial cell-specific protein isoform contributes to the important function of epithelial cell barriers. We also note that small GTPase effectors and regulators are among the enriched terms in Esrp-regulated genes as well as targets of other cell type-specific splicing factors. Previous studies have identified examples of other small GTPases and their regulators that have alternative isoforms with distinct and biologically important differential functions (Ellis et al., 2012; Hinman et al., 2014; Radisky et al., 2005; Singh et al., 2014). While our studies support previous work showing that Arhgef11 plays an important role in the maintenance of epithelial TJs, it bears mentioning that mice with germline KO of Arhgef11 were shown to be viable with phenotypes unrelated to epithelial barrier functions (Chang et al., 2015; Mikelis et al., 2013). While it is possible that subtle alterations in epithelial junctions may have been overlooked in these mice, we suspect that Arhgef11 ablation in early-stage embryos may lead to compensation by other Rho GTPase effectors. Consistent with this possibility, ablation of Arhgef11 together with its paralog Arhgef12 resulted in embryonic lethality (Mikelis et al., 2013). There are also several other Rho GTPase effectors such as Arhgef2 and Arhgef18 that have been linked to the regulation of TJ-based barriers that may also be co-opted to maintain epithelial barriers in response to germline loss of Arhgef11 functions (Itoh et al., 2014; Zihni et al., 2016). Consistent with the possibility that conditional deletion of Arhgef11 at a later developmental stage may be associated with more severe phenotypes, another group showed that depletion of Arhgef11 using siRNAs in neuroepithelial cells of chick embryos was associated with the loss of MLC phosphorylation and the failure of neural tube formation (Nishimura et al., 2012). Genetic compensation in response to germline KO of otherwise essential genes is a widespread phenomenon, and thus we suspect that conditional ablation of Arhgef11 in the epidermis may validate the function of Arhgef11 in barrier function in vivo (El-Brolosy and Stainier, 2017). In any event, our studies have identified a context in which we observe a clear isoform-specific difference of a protein involved in the regulation of TJs and provided a mechanism to account for these differences.

Our studies have identified Arhgef11 as an Esrp regulated gene that contributes to epithelial barrier function in the skin through the regulation of TJ integrity. However, further studies are needed to identify additional examples of epithelial cell type-specific protein isoforms that contribute to the barrier functions in these cells, as well as those in other epithelial cell layers such as the gastrointestinal system and the lung. In addition to uncovering further examples of genes with isoform-specific functions in epithelia, such investigations will begin to unravel the molecular mechanisms and protein interaction networks that are specifically relevant to the general maintenance of epithelial cell properties. There are also a host of other disease-relevant phenotypes in both Esrp1 KO and Esrp1;Esrp2 DKO mice that are likely due to the loss of a number of other epithelial specific isoforms that are regulated by the Esrps (Bebee et al., 2015,2016; Rohacek et al., 2017). It will be challenging to find in vitro and in vivo assays that can identify important AS events whose misregulation leads to these phenotypes. With the advances in CRISPR/Cas9 and related genome-editing technologies, it is now possible to begin the systematic generation of mice that only express 1 of 2 different splice variants to further extend our understanding of AS in a broad set of different cell types.

In conclusion, we have identified Arhgef11 as one of the Esrp1 splicing targets that underlies barrier defects in the epidermis, which result from the disruption of TJs. In addition to providing a detailed mechanistic dissection of the differences in Arhgef11 isoforms, these findings provide a further example whereby alterations in protein-protein interactions due to AS can have profound functional consequences at the level of essential cellular functions.

STAR★METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Russ P. Carstens (russcars@upenn.edu). Where indicated the requests will be fulfilled with simple Material Transfer Agreement (MTA).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice

Generation of Esrp1 KO (Esrp1−/−;Esrp2+/+), Esrp DKO (Esrp1−/−;Esrp2−/−), and mice with floxed Esrp1 alleles (Esrp1f/f and Esrp1f/f;Esrp2−/−) for conditional gene ablation were described previously (Bebee et al., 2015). Briefly, exons 7 to 9 were floxed and mice with germline Esrp1 KO were derived in crosses with Zp3-Cre transgenic females. Esrp2 KO alleles include a LacZ reporter in place of the entire Esrp2 coding sequences. To test postnatal Esrp function in epidermis, Esrp1f/f;Esrp2−/−; K5-rtTA; tetO-Cre mice were generated. Transgenic Keratin-5 rtTA (K5-rtTA) (Mucenski et al., 2003) mice, which express Cre under the Keratin 5 promoter in basal epidermal cells and epithelial cells of the hair follicle were obtained from Sarah Millar (University of Pennsylvania) and tetO-Cre strains (Diamond et al., 2000) were obtained from JAX. Mice carrying the K5-rtTA promotor were bred with mice carrying the tetO-Cre transgene and with mice carrying a loxP-flanked Esrp1 allele. Esrp1 deletion in epidermis was induced by Doxycycline (Bio-Serv) feeding after birth. Both male and female mice were included in the study and there were no apparent differences in the observed phenotypes between male and female mice. All experiments involving mice were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Cell lines

293T cells and Py2T were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS at 37°C and 5% CO2. Py2T cell are derived from a breast tumor of an MMTV-PyMT transgenic mouse. Mouse MCK-6 keratinocyte cells were maintained under low calcium and low serum (2% FBS) defined-KSFM media in collagen type-1 coated dishes.

METHOD DETAILS

Plasmids for transfections of cDNAs

pIBX and pIPX expression vectors, that contain IRES driven blasticidin and puromycin selection markers, respectively were previously described (Warzecha et al., 2009). To construct Arhgef11 (mouse) and ARHGEF11 (human) expression vector, initially Mouse Arhgef11 and human ARHGEF11 cDNA for mesenchymal isoforms were commercially purchased (see Key Resources Table). The PCR amplified coding sequence for Mes-Arhgef11 and Mes-ARHGEF11 was inserted into EcoRI and NotI digested vector. The cDNAs for the epithelial isoforms (Epi-Arhgef11 and Epi-ARHGEF11) were obtained by RT-PCR of the region where the exon is skipped from epithelial cells that were then inserted in NheI and NotI or BglII and NotI digested pIBX or pIPX ARHGEF11 or Arhgef11 expression vectors, respectively to replace the same regions that contained the mesenchymal exon. Arhgef11 KO Py2T cells were transiently transfected with pIBX based vectors using Lipofectamine 3000 and selected in 10 ug/ml blasticidin for 48 hours prior to assays. Transient transfections of pIPX based versions of ARHGEF11 isoforms in 293T cells (Figure 6) were carried out using Mirus 293T along with pIPX empty vector control and harvested after 48 hours. Stable transfections of 293T and Py2T with pIPX based ARHGEF11 cDNAs were carried out using Mirus 293T and Lipofectamine 3000, respectively and selected in puromycin for over 3 weeks. The pSg-Puro plasmid was created for transfection of sgRNAs with a vector containing a puromycin selection cassette. It was generated by removal of the Cas9 coding sequence from px300 with AgeI and EcoRI and replacing it with a coding sequence for a puromycin selection cassette. Lentiviral production and transduction were performed as previously described (Warzecha et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2016b).

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| ZO-1 | Invitrogen | Cat#40-2200; RRID: AB_2533456 |

| Claudin-1 | Invitrogen | Cat#71-7800; RRID: AB_2533997 |

| PAK4 | Cell Signaling | Cat#3242S; RRID: AB_2158622 |

| phospho-MLC2 | Cell Signaling | Cat#3675S; RRID: AB_2250969 |

| MLC2 | Cell Signaling | Cat#3672S; RRID: AB_10692513 |

| FLAG-M2 | Sigma | Cat#F1804; RRID: AB_262044 |

| β-actin | Sigma | Cat#A2228; RRID: AB_746697 |

| Occludin | Life technologies | Cat#331-500; RRID: AB_2533101 |

| Rabbit IgG Alexa 488 | Life technologies | Cat#A24922; RRID: N/A |

| Mouse IgG Alexa 594 | Life technologies | Cat#A24921; RRID: AB_2536036 |

| Streptavidin, Alexa 488 | Life technologies | Cat#S32354; RRID: N/A |

| PDZ-RhoGEF(ARHGEF11) | BethylLaboratorues | Cat#A301-952A; RRID: AB_1548009 |

| RhoA | Cytoskeleton | Cat#ARH04; RRID: N/A |

| Esrp1 | (Warzecha et al., 2010) | N/A |

| Esrp2 | This paper | N/A |

| CD3 | Abcam | Cat#5690; RRID: AB_305055 |

| F4/80 | Abcam | Cat#6640; RRID: AB_1140040 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| EZ-Link sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin | Thermo Scientific | Cat#21327 |

| Lipofectamine 3000 | Invitrogen | Cat#11668019 |

| Bovine Serum Albumin | Cell Signaling | Cat#9998S |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Biolab | Cat#M0202S |

| 3X FLAG peptide | Sigma | Cat#F3290 |

| Protein A Agarose | Invitrogen | Cat#15918-014 |

| Random hexamers | Thermo | SO142 |

| M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase | Promega | M170A |

| Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI | Invitrogen | Cat#P36935 |

| Anti-FLAG Affinity Gel | Sigma | Cat#A2220 |

| TransIT-293 | Mirus | Cat#MIR2700 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Rho Activation Assay Biochem Kit | Cytoskeleton | Cat#BK036 |

| Millicell® ERS-2 Voltohmmeter | Millipore | Cat#MERS0002 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| MKC-6 | (Troy and Turksen, 1999) | N/A |

| 293T | ATCC | CRL-3216 |

| Py2T | Gerhard Christofori (Waldmeier et al., 2012) | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Mice Strains | ||

| Esrp1−/−;Esrp2−/− | (Bebee et al., 2015) | N/A |

| Esrp1−/−;Esrp2+/+ | (Bebee et al., 2015) | N/A |

| Esrp1f/f;Esrp2−/−;K5-rtTA;tetO-Cre | This paper | N/A |

| Tg(tetO-cre)1Jaw/J (tetO-Cre) | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX stock #006224 |

| Keratin 5-rtTA (K5-rtTA) | Sarah Millar (Penn) | (Diamond et al., 2000) |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for amplification of hEpi-ARHGEF11 cDNA for recombinant protein expression Forward: | This paper | N/A |

| GGGAATTCGCCACCATGAGTGTAAGGTTACCCCA | ||

| Primers for amplification of hEpi-ARHGEF11 cDNA for recombinant protein expression Reverse: | This paper | N/A |

| GGGCGGCCGCTGGTCCTGGTGACGCGGCTG | ||

| Primers for amplification of mEpi-Arhgef11 cDNA for recombinant protein expression Forward: | This paper | N/A |

| GGGAATTCGCCACCATGAGTGTAAGGTTACCCCA | ||

| Primers for amplification of mEpi-Arhgef11 cDNA for recombinant protein expression Reverse: | This paper | N/A |

| GGGCGGCCGCTGGTCCTGGTGACGCGGCTG | ||

| Arhgef11 and ARHGEF11 RT-PCR Forward: | This paper | N/A |

| TCAAGCTCAGAACCAGCAGGAAGT | ||

| Arhgef11 and ARHGEF11 RT-PCR Reverse: | This paper | N/A |

| TGCTCGATGGTGTGGAAGATCACA | ||

| Single-guide RNA Sequences, see Table S1 | This paper | N/A |

| PCR primer sequences used to confirm CRISPR/Cas9 mediated KO, see Table S2 | This paper | N/A |

| shRNA sequences used for Esrp1 or Esrp2 knock down experiments, see Table S3 | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| psPAX2 | Addgene | Addgene#12260 |

| pCMV-VSV-G | Addgene | Addgene#8454 |

| Plasmid: pSg-Puro | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: pLKO.1-puro | Sigma | #SHC001 |

| Plasmid: pIBX-Epi-Arhgef11 | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: pIBX-Mes-Arhgef11 | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: pIPX-Epi-ARHGEF11 | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: pIPX Mes-ARHGEF11 | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: pIBX-Epi-ARHGEF11 | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: pIBX-Mes-ARHGEF11 | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: pIBX-Cas9 | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: PX330 | Addgene | Addgene#42230 |

| ARHGEF11 cDNA | Dharmacon | BC057394 |

| Arhgef11 cDNA | Dharmacon | BC079565 |

| Plasmid: pMG1-SVT | (Eyckerman et al., 2001) | N/A |

| Plasmid: pSEL+2L-hMal | (Eyckerman et al., 2001) | N/A |

| Plasmid: pMG1-GW | (Eyckerman et al., 2001) | N/A |

| Plasmid: pSEL+2L-GW | (Eyckerman et al., 2001) | N/A |

| Plasmid: pXP2d2-rPAP1-luci | (Eyckerman et al., 2001) | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Prizm | Graphpad | N/A |

| ImageQuant TL, version 7.0 | GE Healthcare | N/A |

Plasmids for Lentiviral transduction of shRNAs

Vectors for KD of Esrp1 and Esrp2 were constructed by digesting pLKO.1-puro with AgeI and EcoR1 and cloning in annealed oligo pairs in Table S3. After 20 hours incubation, the media was replaced with fresh DMEM with 10% FBS, and virus was harvested after an additional 24 hours. Target cells were transduced with a 50/50 mixture of viral supernatant and DMEM with 10% FBS. Cells were drug selected using 2 μg/ml puromycin for 96 to 120 hours. RNA or protein was harvested 7 to 8 days after viral infection.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated KO

-Cas9 stable cell Generation

To generate py2T cells with KO of Esrp1, Esrp2, and Arhgef11 we purchased the PX330 vector from Addgene (#42230). PX330 was digested with AgeI and EcoRI to obtain the coding sequences for human codon-optimized SpCas9 (hSpCsn1). This fragment was inserted into the pIBX vector and we named it pIBX-Cas9. We transfected the pIBX-Cas9 vector into Py2T cells using Lipofectamine 3000 according the manufacturers’ protocols. 48 hours post-transfection, the cells were selected using 10ug/ml Blasticidin. A population of Py2T cells that stably express Cas9 was obtained by maintaining Blasticidin selection for 20 days. Single cell clones were obtained by serial dilution. Protein lysates from several clones were harvested in RIPA buffer and the expression of Cas9 protein was confirmed by Western.

-Esrp1 KO

Py2T cells were transiently transfected Lipofectamine 3000 in 24well plate. Cells were transfected with a total of 1mg of total DNA: 250ng of pX335 with guide 8A, 250ng of pX335 with guide 16A, 250ng pIPX-mCherry. After 24hrs, transfected cells were enriched by the addition of medium containing puromycin at 5 μg/mL for 72hrs. Cells were allowed to recover for overnight in medium with selection antibiotic. Clonal cells were isolated in 96-well plate format. Genomic DNA was amplified from clonal lines using primers flanking the nickase targeted site. The PCR products were cloned in a blunt vector, and after transformation colonies were submitted for sequencing to identify indels or the knock-in of the FLAG tag at the Esrp1 locus, to generate a FLAG Esrp1 fusion.

-Esrp 1/2 DKO

Esrp1 KO Py2T cells were transiently transfected with 400ng pX330 without guide sequence (for expression of Cas9) and 300ng with pSg-Puro vectors containing guide sequences targeting introns 1 and 3 for removal of exons 2 and 3. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 in 24well plates. After 24hrs, transfected cells were selected by the addition of medium containing puromycin at 10 ng/mL for 72hrs. Cells were allowed to recover overnight in medium without selection. Clonal cells were isolated in 96-well format. Genomic DNA was amplified from clonal lines using primers flanking the targeted exon. The PCR products were confirmed by sequencing.

-Arhgef11 KO

We obtained pSg-Puro vectors with guide RNAs targeting the introns flanking Arhgef11 exon 2 (which is the first non-multiple of three constitutive exon). Upon transfection of a pair of sgRNA plasmids in the Py2T Cas9 clone we isolated clones following puromycin selection where Arhgef11 exon 2 was deleted. The KO of Arhgef11 was then confirmed by PCR and Westernblot. For deletion of Arhgef11 exon 37 we designed two pairs of sgRNAs in the introns flanking this exon and isolated clones in which exon 37 deletion was confirmed for each pair of sgRNAs.

Isolation of RNA, Reverse Transcription, and RT-PCR

RNA for RT-PCR experiment was isolated from PY2T and MKC-6 cells via TriZol (Invitrogen) and Zymo-Spin IIC columns (Zymo Research). RNA isolation of E18.5 embryo epidermis was described previously (Bebee et al., 2015). Reverse transcription and RT-PCR was performed as described previously (Bebee et al., 2015; Warzecha et al., 2009).

Immunofluorescence

Frozen sections of the mice epidermis were fixed for 10 minutes in acetone at −20°C. Paraffin section deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated using graded ethanol. Cultured cells were fixed in cold methanol 5 minutes and then in acetone 15 s at 4°C. Antigen retrieval was performed using unmasking solution (Vector Laboratories) or 0.5% Triton X-100 in humidified chamber. Samples were blocked with 0.5%nonfat dry milk and 10% horse serum in PBST 1hour at RT. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing three times with PBST, Alexa 488 or Alexa 594labeled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were applied for 30 minutes at RT, followed by another wash and mounted with Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen).Images were taken using an Olympus BX43.

Immunoblot

Total cell lysates were harvested in RIPA buffer and immunoblotting was performed as described previously (Bebee et al., 2015).Briefly, Total proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking for 1 hour with 5% Non-fat dry milk powder or 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris buffered saline-tween 20 (TBST), membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies. Subsequently, membranes were washed in TBST and incubated for 1 hour with the appropriate secondary antibodies. After washing thrice for 10 minutes with TBST, proteins were visualized by chemiluminescent detection (Thermo Scientific).

Co-IP

Total cell lysates were prepared as described in NP-40 buffer (1% NP-40, 150mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 50mM Tris-HCl, pH8.0). For the FLAG IP, proteins were incubated with anti-FLAG affinity gel (Sigma) for 1hour at 4°C with rotating. Beads were washed 4 times with wash buffer, and then resuspended in protein loading buffer. For the PAK4 IP, lysates were pre-cleared with Protein A Agarose (Invitrogen) for 1 hour at 4°C and then incubated with 10 μg of anti-PAK4 antibody (Cell Signaling), overnight at 4°C. Antigen-Antibody bound Protein A Agarose pellets were washed 4 times with wash buffer, and then resuspended in protein loading buffer. The released proteins were fractionated by Bis-Tris 4%–20% SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen), and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Immunoblotting was performed as described above using antibodies RhoA, PAK4, Flag, or β-actin antibody as described above.

Rho Activation assay

All the materials were from the Rho Activation Assay Biochem Kit (Cytoskeleton, Cat#BK036) and we followed the methods using the manufacturers’ protocols. Briefly, Cell lysates were harvested in lysis buffer. Proteins incubated with 50μg of Rhotekin-RBD beads at 4°C on rotator for 1hour. Beads were subsequently washed with wash buffer. Pull-down and immunoblotting step are described above.

Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) assay and FITC-dextran flux assay

MKC-6 Keratinocytes or Py2T epithelial cells were grown on polycarbonate Transwell filters (Corning) in low glucose and calcium free media. After fully confluent, a calcium shift was begun with addition of media containing 1.5Mm CaCl2. Before measurement, electrodes were equilibrated and sterilized with 70% ethanol and PBS. TEER was measured with a Millicell® ERS-2 Voltohmmeter (Millipore). To obtain the monolayer resistance, the empty transwell (blank) value was subtracted from the each resistance of the samples. Values were expressed in Ω *cm2and measurement was performed every 24hours after calcium switch at indicated times. Mean results are calculated from three independent experiment. After final TEER measurement, each upper chamber was washed with PBS and moved to new 12 wells plate for the following FITC-dextran flux assay. 0.5mg/ml FITC-dextran (4kDa) (Sigma-Aldrich) was applied to the cell monolayers and plates were incubated for 120-150mins at 37°C. After incubation, the PBS containing penetrated FITC-dextran from the transwells was collected and fluorescence intensity was measured using a Typhoon FLA 9500. The amount of FITC-dextran was quantified and calculated using a ImageQuant TL, version 7.0

Biotin injection assay

To test the TJ barrier permeability in mice, 10 mg/ml EZ-Link sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (Pierce Chemical) in PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2was intradermally injected underneath the dermis of the E18.5 mice back skin. After 30 minutes of incubation at 37°C, mice back skin was isolated, embedded in Tissue-Tek, and frozen. 4% Paraformaldehyde fixed section was immunostained with TJ marker, anti-Occludin antibody. After washing step, Alexa 594labeled secondary antibodies (Life technologies)for TJ marker and Alexa 488 Streptavidin (Life technologies)for biotin labeling were applied for 30 minutes at RT. Followed by another washing and mounted with Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen).Image were taken using an Olympus BX43.

MAPPIT assay

The plasmids pMG1-SVT, pSEL+2L-hMal, pMG1-GW, pSEL+2L-GW and pXP2d2-rPAP1-luci were obtained from Jan Tavernier. The cDNA for ARHGEF11 Mesenchymal and Epithelial isoforms were obtained as previously described, and were subcloned in pMG1 (prey) and pSEL+2L (bait) using EcoRI/NotI and XhoI/NotI respectively. The cDNA for PAK4 (HsCD00376906) was obtained from the PlasmID Repository at Harvard Medical School. PAK4 was cloned using Gateway Recombination LR Cloning (Thermo Fisher Scientific) into the pMG1-GW (prey) and pSEL+2L-GW (bait). All plasmids were verified by Sanger Sequencing. The SV40 large T-antigen was obtained from Addgene (#1780) and following PCR amplification of amino acids 261-708, was cloned into bait and prey vectors using Gateway recombination. MAPPIT transfections and assay were performed as previously described (Venkatesan et al., 2009). Briefly, HEK293T cells were seeded in 96-well plate at a density of 12000 cells/well. Prior to plating wells were treated with 20mg/mL collagen to aid adherence of HEK293T. Cells were transfected 24hrs after seeding with 45ng of bait containing vector, 45ng of prey containing vector and 10ng of luciferase reporter plasmid, in two sets of triplicates, using TransIT-293 (Mirus). On the following day, cells were stimulated with 5ng/mL human Erythropoietin (Cell Signaling Technology, 6980SC) in triplicate. Luciferase readings were collected 24hrs after hEpo stimulation, by lysing the cells Britelite Plus (Perkin Elmer) and measurements were recorded using DTX Multimode plate reader. Interactions of ARHGEF11 Mesenchymal and Epithelial and PAK4 were tested with each cDNA cloned in prey and bait plasmid. Positive protein protein-protein interactions were identified as previously described (Venkatesan et al., 2009), by identifying Experiment to Control Ratio (ECR) > 10 in any orientation. ECR for the MAPPIT was calculated as the fold-induction value with bait and prey, divided by the fold-induction value with bait and irrelevant prey, or prey and irrelevant bait. The irrelevant interacting protein tested was SV40 large T-antigen. Fold induction was calculated as the ratio of luciferase reading of bait:prey interaction in the presence of hEpo with luciferase reading of bait:prey interaction in the absence of hEpo.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses of the data were performed in Graphpad Prism. Error bars represent ± SD of experiments performed in at least one biological triplicate. Statistical significance was calculated by t test and denoted as follows: * = p < 0.01, p < 0.005; **, p < 0.001; ***, p < 0.0001; ****. Results of statistical analysis are presented in Figure Legends 1, 4, and 5 where the value for n in each case is provided.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Ablation of Esrp1 and Esrp2 in mouse epidermis leads to tight junction defects

A switch in splicing of exon 37 in Arhgef11 transcripts produces isoforms that bind Pak4

Inhibition of Arhgef11 by Pak4 causes a reduction in RhoA activation at tight junctions

Restoration of epithelial Arhgef11 isoforms partially rescues tight junction defects

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Skin Biology and Diseases Resource-based Center (SBDRC) at the University of Pennsylvania assisted in consultation and tissue processing. We thank Dr. Stephen Prouty for technical expertise in skin and tissue histology, Dr. Sarah Millar’s lab for mouse and technical and experimental guidance, and Dr. John Seykora for phenotype analysis and consultation. This work was funded by NIH grants RO1AR066741, R56AR066741, and P30AR057217 (to R.P.C.).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes six figures and three tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.097.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Augustin I, Gross J, Baumann D, Korn C, Kerr G, Grigoryan T, Mauch C, Birchmeier W, and Boutros M (2013). Loss of epidermal Evi/Wls results in a phenotype resembling psoriasiform dermatitis. J. Exp. Med 210, 1761–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barac A, Basile J, Vázquez-Prado J, Gao Y, Zheng Y, and Gutkind JS (2004). Direct interaction of p21-activated kinase 4 with PDZ-RhoGEF, a G protein-linked Rho guanine exchange factor. J. Biol. Chem 279, 6182–6189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebee TW, Park JW, Sheridan KI, Warzecha CC, Cieply BW, Rohacek AM, Xing Y, and Carstens RP (2015). The splicing regulators Esrp1 and Esrp2 direct an epithelial splicing program essential for mammalian development. eLife 4, e08954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebee TW, Sims-Lucas S, Park JW, Bushnell D, Cieply B, Xing Y, Bates CM, and Carstens RP (2016). Ablation of the epithelial-specific splicing factor Esrp1 results in ureteric branching defects and reduced nephron number. Dev. Dyn 245, 991–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe BJ (2017). The relationship between alternative splicing and proteomic complexity. Trends Biochem. Sci 42, 407–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buljan M, Chalancon G, Eustermann S, Wagner GP, Fuxreiter M, Bateman A, and Babu MM (2012). Tissue-specific splicing of disordered segments that embed binding motifs rewires protein interaction networks. Mol. Cell 46, 871–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YJ, Pownall S, Jensen TE, Mouaaz S, Foltz W, Zhou L, Liadis N, Woo M, Hao Z, Dutt P, et al. (2015). The Rho-guanine nucleotide exchange factor PDZ-RhoGEF governs susceptibility to diet-induced obesity and type 2 diabetes. eLife 4, e06011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, and Manley JL (2009). Mechanisms of alternative splicing regulation: insights from molecular and genomics approaches. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 741–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieply B, and Carstens RP (2015). Functional roles of alternative splicing factors in human disease. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 6, 311–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Benedetto A, Rafaels NM, McGirt LY, Ivanov AI, Georas SN, Cheadle C, Berger AE, Zhang K, Vidyasagar S, Yoshida T, et al. (2011). Tight junction defects in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 127, 773–786.e1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond I, Owolabi T, Marco M, Lam C, and Glick A (2000). Conditional gene expression in the epidermis of transgenic mice using the tetracycline-regulated transactivators tTA and rTA linked to the keratin 5 promoter. J. Invest. Dermatol 115, 788–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar KA, Jiang P, Park JW, Amirikian K, Wan J, Shen S, Xing Y, and Carstens RP (2012). Genome-wide determination of a broad ESRP-regulated posttranscriptional network by high-throughput sequencing. Mol. Cell. Biol 32, 1468–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Brolosy MA, and Stainier DYR (2017). Genetic compensation: a phenomenon in search of mechanisms. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JD, Barrios-Rodiles M, Colak R, Irimia M, Kim T, Calarco JA, Wang X, Pan Q, O’Hanlon D, Kim PM, et al. (2012). Tissue-specific alternative splicing remodels protein-protein interaction networks. Mol. Cell 46, 884–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyckerman S, Verhee A, der Heyden JV, Lemmens I, Ostade XV, Vandekerckhove J, and Tavernier J (2001). Design and application of a cytokine-receptor-based interaction trap. Nat. Cell Biol 3, 1114–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Hata M, Furuse K, Yoshida Y, Haratake A, Sugitani Y, Noda T, Kubo A, and Tsukita S (2002). Claudin-based tight junctions are crucial for the mammalian epidermal barrier: a lesson from claudin-1-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol 156, 1099–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehman LT, Stoilov P, Maguire J, Damianov A, Lin CH, Shiue L, Ares M Jr., Mody I, and Black DL (2011). The splicing regulator Rbfox1 (A2BP1) controls neuronal excitation in the mammalian brain. Nat. Genet 43, 706–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladden AB, Hebert AM, Schneeberger EE, and McClatchey AI (2010). The NF2 tumor suppressor, Merlin, regulates epidermal development through the establishment of a junctional polarity complex. Dev. Cell 19, 727–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinman MN, Sharma A, Luo G, and Lou H (2014). Neurofibromatosis type 1 alternative splicing is a key regulator of Ras signaling in neurons. Mol. Cell. Biol 34, 2188–2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttlin EL, Ting L, Bruckner RJ, Gebreab F, Gygi MP, Szpyt J, Tam S, Zarraga G, Colby G, Baltier K, et al. (2015). The BioPlex network: a systematic exploration of the human interactome. Cell 162, 425–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh M (2013). ARHGEF11, a regulator of junction-associated actomyosin in epithelial cells. Tissue Barriers 1, e24221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh M, Tsukita S, Yamazaki Y, and Sugimoto H (2012). Rho GTP exchange factor ARHGEF11 regulates the integrity of epithelial junctions by connecting ZO-1 and RhoA-myosin II signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 9905–9910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K, Ossipova O, and Sokol SY (2014). GEF-H1 functions in apical constriction and cell intercalations and is essential for vertebrate neural tube closure. J. Cell Sci 127, 2542–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh M, Radisky DC, Hashiguchi M, and Sugimoto H (2017). The exon 38-containing ARHGEF11 splice isoform is differentially expressed and is required for migration and growth in invasive breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 8, 92157–92170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov AI (2008). Actin motors that drive formation and disassembly of epithelial apical junctions. Front. Biosci 13, 6662–6681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KB, Dredge BK, Stefani G, Zhong R, Buckanovich RJ, Okano HJ, Yang YY, and Darnell RB (2000). Nova-1 regulates neuron-specific alternative splicing and is essential for neuronal viability. Neuron 25, 359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsotra A, Xiao X, Ward AJ, Castle JC, Johnson JM, Burge CB, and Cooper TA (2008). A postnatal switch of CELF and MBNL proteins reprograms alternative splicing in the developing heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 20333–20338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner N, and Brandner JM (2012). Barriers and more: functions of tight junction proteins in the skin. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci 1257, 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo A, Nagao K, and Amagai M (2012). Epidermal barrier dysfunction and cutaneous sensitization in atopic diseases. J. Clin. Invest 122, 440–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Kim H, Kim K, Lee H, Lee S, and Lee D (2016). Arhgap17, a RhoGTPase activating protein, regulates mucosal and epithelial barrier function in the mouse colon. Sci. Rep 6, 26923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikelis CM, Palmby TR, Simaan M, Li W, Szabo R, Lyons R, Martin D, Yagi H, Fukuhara S, Chikumi H, et al. (2013). PDZ-RhoGEF and LARG are essential for embryonic development and provide a link between thrombin and LPA receptors and Rho activation. J. Biol. Chem 288, 12232–12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucenski ML, Wert SE, Nation JM, Loudy DE, Huelsken J, Birchmeier W, Morrisey EE, and Whitsett JA (2003). beta-Catenin is required for specification of proximal/distal cell fate during lung morphogenesis. J. Biol. Chem 278, 40231–0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Jahan I, Bonde G, Sun X, Hildebrand MS, Engelhardt JF, Smith RJ, Cornell RA, Fritzsch B, and Bánfi B (2012). A mutation in the Srrm4 gene causes alternative splicing defects and deafness in the Bronx waltzer mouse. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Honda H, and Takeichi M (2012). Planar cell polarity links axes of spatial dynamics in neural-tube closure. Cell 149, 1084–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusrat A, Giry M, Turner JR, Colgan SP, Parkos CA, Carnes D, Lemichez E, Boquet P, and Madara JL (1995). Rho protein regulates tight junctions and perijunctional actin organization in polarized epithelia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 10629–10633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, and Blencowe BJ (2008). Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat. Genet 40, 1413–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasparakis M, Haase I, and Nestle FO (2014). Mechanisms regulating skin immunity and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol 14, 289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radisky DC, Levy DD, Littlepage LE, Liu H, Nelson CM, Fata JE, Leake D, Godden EL, Albertson DG, Nieto MA, et al. (2005). Rac1b and reactive oxygen species mediate MMP-3-induced EMT and genomic instability. Nature 436, 123–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid T, Furuyashiki T, Ishizaki T, Watanabe G, Watanabe N, Fujisawa K, Morii N, Madaule P, and Narumiya S (1996). Rhotekin, a new putative target for Rho bearing homology to a serine/threonine kinase, PKN, and rhophilin in the rho-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem 271, 13556–13560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohacek AM, Bebee TW, Tilton RK, Radens CM, McDermott-Roe C, Peart N, Kaur M, Zaykaner M, Cieply B, Musunuru K, et al. (2017). ESRP1 mutations cause hearing loss due to defects in alternative splicing that disrupt cochlear development. Dev. Cell 43, 318–331.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz A, Lazi’ć E, Koumaki D, Kuonen F, Verykiou S, and Rübsam M (2015). Assessing the in vivo epidermal barrier in mice: dye penetration assays. J. Invest. Dermatol 135, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]