Abstract

The vulnerability and instability of low-income mothers situated in a context with a weak public safety net make informal social support one of few options many low-income mothers have to meet basic needs. This systematic review examines (a) social support as an empirical construct, (b) the restricted availability of one important aspect of social support—informal perceived support, hereafter informal support—among low-income mothers, (c) the role of informal support in maternal, economic, parenting, and child outcomes, (d) the aspects of informal support that influence its effects, and (e) directions for future research. Traditional systematic review methods resulted in an appraisal of 65 articles published between January 1996 and May 2017. Findings indicated that informal support is least available among mothers most in need. Informal support provides some protection from psychological distress, economic hardship, poor parenting practices, and poor child outcomes. To promote informal support and its benefits among low-income families, future research can advance knowledge by defining the quintessential characteristics of informal support, identifying instruments to capture these characteristics, and providing the circumstances in which support can be most beneficial to maternal and child well-being. Consistent measurement and increased understanding of informal support and its nuances can inform intervention design and delivery to strengthen vulnerable mothers’ informal support perceptions thereby improving individual and family outcomes.

Keywords: informal support, low-income mothers, social support, safety net, poverty

More than one in ten US families lives in poverty, including 30% of single-mother families and 20% of children (Proctor, Semega, & Kollar, 2016). Living or growing up in poverty strongly predicts greater barriers and instability across several interrelated life domains, including higher incidence of school dropout, unemployment, out-of-wedlock birth, harsh parenting strategies, parenting stress, and poor physical and mental health compared to those above the poverty line. Children living in poverty experience a high incidence of educational, behavioral, and emotional problems, and, similar to their mothers, poor physical and mental health outcomes (for review see Edin & Kissane, 2010).

Compared to other industrialized nations, US families benefit less from the public safety net, or the available government cash or in-kind assistance (IOM, 2013). The Personal Responsibility Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act in 1996, more commonly known as welfare reform, replaced the formal cash safety net with a work-based system increasing poor families’ reliance on informal supports. Welfare redistribution spending across all government programs has decreased post welfare reform among the poorest families (Moffitt, 2015). Just before welfare reform in 1995, almost 80% of poor families with children received cash assistance compared to 27% of such families in 2010 (Trisi & Pavetti, 2012). Families in poverty do not receive benefits for a variety of reasons including hassle, stigma, lack of information or misinformation, unlawful termination, or benefit exhaustion (i.e., exceeding the time limits of benefits; Edin & Shaefer, 2015). The number of extremely vulnerable families “disconnected” from employment and cash welfare grew from 12% of low-income single mothers in 2004 to 20% in 2008 (Loprest & Nichols, 2011). Recent ethnographic work indicates that disconnected families act in desperate ways (e.g., selling plasma, working in the underground economy, doubling up with violent partners) that may subject their children to unsafe conditions (Auyero, 2015).

Much of poor families’ vulnerability stems from the structure of the economy including limited (a) living-wage jobs, (b) stable jobs, (c) educational access, (d) affordable healthcare, and (e) affordable housing (Auyero, 2015). Although poor mothers have long-relied on family and friends to supplement cash wages or welfare (e.g., Edin & Lein, 1997), the vulnerability of low-income mothers situated with a weak public safety net make informal social support one of few options many families have to meet basic needs. The potential that a mother’s network and community cannot compensate for unmet needs is a critical concern given the shift to time-limited programs and few available benefits.

Social relationships are undeniably important for human functioning and well-being. From sociologist Durkheim’s (1951) examination of suicide to community psychologist Cowen’s (1994) work on attachment and social competencies to criminologists Laub et al.’s (1998) examination of recidivism, extensive evidence indicates that interacting well with others matters for physical, psychological, emotional, and economic well-being. With its importance, scholars have long debated the measurement of social relationships and social support (e.g., Barrera, 1986; House, 1981; Sarason, Sarason, & Pierce, 1990). Rather than common definition and measurement, the concept often considers individual, family, or community resources and their influence on the functioning and well-being of individuals and societies (Brownell & Shumaker, 1984). Social support’s ever-broadening concepts in the literature, such as social networks, social bonds, social capital, tangible support, informal support, or private safety nets, all share the idea of connection to others, yet also illustrate Barrera’s (2000) call for studies to clarify measured concepts.

Informal support has been defined as the “functional content of relationships” (House & Kahn, 1985, p. 85). In this way, informal support captures the practicality dimension of social support’s broader concept as opposed to measuring community relationships or civic group participation that are arguably less fundamental to the survival of low-income families. Specifically, informal support measures available support (e.g., practical, childcare, financial, housing, emotional) that mothers can turn to meet their basic needs. For example, common illustrations of practical support include someone to provide a ride or someone to provide small favors. Emotional support commonly includes someone that will listen to their problems when they feel low. Put simply, informal support captures whether or not mothers have others that can help them out to meet a basic need, or needs, should the need arise.

Informal support can be received or perceived. In terms of received support, individuals often do not receive support without facing hardships and a need to call upon social relationships. This increased level of need compared to those not receiving support may create a negative relationship between support receipt and well-being (Cutrona, 1986). Received support can present endogeneity, or measurement error in capturing informal support among low-income families. For example, in order for a mother to receive money from a friend, the mother must be in a position to need the money in the first place. To avoid this precondition of need, perceived support measures support availability without requiring support activation. Measuring perceived support, however, introduces the potential to measure self-esteem or personality characteristics rather than actual support availability (Dunkel-Shetter & Bennett, 1990; Sarason et al., 1990). A mother’s perception of access to money, for example, may not equate to actual access. Yet, studies suggest that the relationship between perceived support and well-being persists net of personality characteristics (Turner & Turner, 1999). Because of perceived support’s stronger relationship to well-being, social support research generally examines perceptions rather than receipt (Harknett, 2006; Turner & Turner, 1999; Wethington & Kessler, 1986).

This systematic review delineates low-income mothers’ access to informal support and informal support’s role in maternal and child well-being in the era of a weak public safety net. Specifically, the review examines (a) social support as an empirical construct, (b) the restricted availability of one important aspect of social support—informal perceived support, hereafter informal support—among low-income mothers post welfare reform, or after 1995, (c) the role of informal support in maternal health and well-being, economic, parenting, and child outcomes, (d) the aspects of informal support that influence its effects, and (e) directions for future research. Findings can inform targeted interventions to buoy low-income mothers’ informal support networks when needed, and policies to bolster the public safety net when critical components of informal support are not available.

Method

The SCIE Systematic Research Reviews: Guidelines (SCIE, 2010) provided a general framework to search, identify, and evaluate studies for the systematic review. The framework outlines the importance of inclusion and exclusion criteria, search strategies, study selection, and study quality.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To consider informal support available post welfare reform, the search included quantitative articles published in peer-reviewed journals in English that met the following four criteria: (1) examined at least one aspect of perceived informal instrumental or emotional support, (2) focused on low-income mothers (e.g., at least one-half of sample was low-income mothers with minor children), (3) used data collected in 1996 or later, and (4) occurred in the United States. Inclusion criteria did not consider predictors or outcomes of support; all studies that met the above criteria were included. Although qualitative methods could provide great insight into the functionality of informal support for low-income mothers and their families, qualitative studies identified in preliminary searches generally considered network operation (i.e., received support) and did not provide explicit criteria for measuring social support (e.g., Raudenbush, 2016), an important criterion for inclusion in this study. Therefore, the review did not include qualitative studies. The review also excluded studies that measured informal support (a) as a single item on a multidimensional instrument (e.g., 21-item, Parent Risk Questionnaire), (b) as a combination of perceived and received supports, or (c) through unpublished items in which inclusion criteria could not be assessed.

Search Strategies

To capture informal support, keywords were developed for each criterion based on librarian expertise and common keywords in pre-identified articles. Pre-identified articles’ references were selected (a) based on their focus on informal support and (b) to represent a variety of data sources (pre-identified articles noted with + in the references). The following terms were used to capture informal support: informal support OR social support OR emotional support OR kin networks OR perceived support OR instrumental support OR private safety net OR informal safety net OR expressive support. The following terms were used to encompass low-income mothers: poverty OR single-mother families OR low-income families OR disadvantaged mothers OR single mothers OR fragile families. The search included an electronic search of nine databases including Social Science Citation Index (SSCI, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-SSH), PsycINFO, Sociological Collection, Sociological Abstracts, Social Service Abstracts, Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts, MEDLINE, Sociology Database, and Social Science Database. In addition to the electronic search, recent articles from key prestigious journals that publish in the subject area (i.e., American Sociological Review, Journal of Marriage and the Family, Family Relations, Child Development) were also searched as were the references of articles initially included in the review.

Article Selection

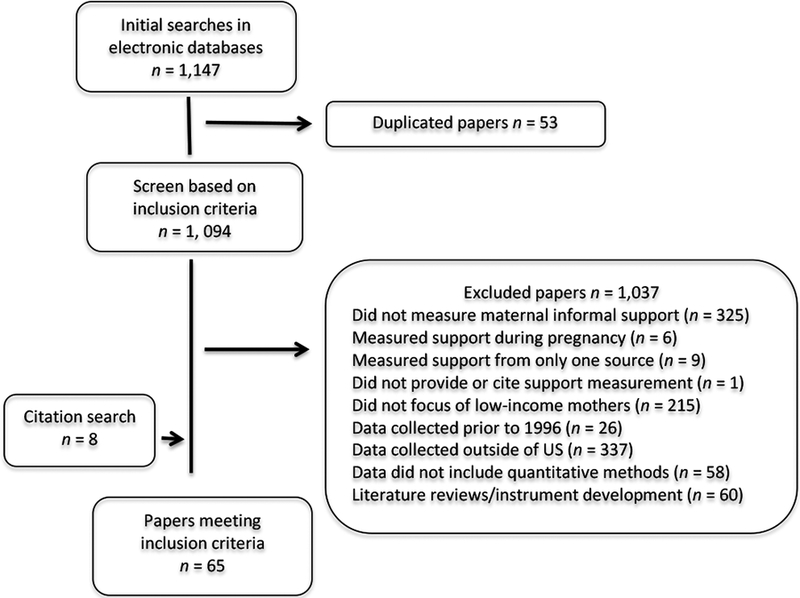

The search included peer-reviewed articles published between January, 1996 and May, 2017. Figure 1 outlines the article selection process. The electronic search resulted in 1,147 records. Searches were imported into a web-based bibliography and database manager system to de-duplicate the articles and sort them for inclusion, exclusion, and reason for exclusion, when applicable. After the removal of duplicate articles, the process yielded 1,094 records. Based on a review of the abstract, or articles when necessary, articles were excluded that did not fit study criteria. The selection resulted in 57 articles examining informal support. Through a reference search of identified articles, additional articles (n = 8) were identified meeting study criteria yielding a total of 65 articles. Articles most often examined informal support primarily as independent variables (n = 37) with fewer examining support primarily as moderating/mediating (n =18) or dependent (n = 9) variables.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Article Selection Process

Quality Rating

To rate the quality of the research in each article, the study utilized the SCIE Systematic Research Review Guidelines. From São José, Barros, Samitca, and Teixeira’s (2016) seven-item appraisal tool, each study was evaluated using a three-point scale (i.e., 0, 0.5, 1) to rate the explicitness, or clarity, in six areas: research aims, sampling strategy, sample composition, data collection tools, data analysis tools, and discussion of the quality of analysis/findings. The seventh item, also rated on the three-point scale, considered the relevance of the article to the review’s questions. Possible scores ranged from 0 to 7 in which studies scoring a 7 were of the highest quality. One study scored in the medium range and the remainder scored in the high-quality range (6–7) indicating explicit explanations in all areas and relevance to study questions (see Table 1). The high quality of the included articles reflected the quality of the searched databases and the inclusion criterion of the measurement of informal support. For example, one study of lower quality was excluded because it did not state or reference the utilized measure of informal support. In addition, the vast majority of included studies (n = 60) used data collected with federal funding for which topical and methodological experts provided a rigorous review of study protocol. Of the 65 articles in the synthesis, 27 used the Fragile Families and Child Well-Being Study (FFCWBS), a federally-funded longitudinal research study of a birth cohort of children born to predominantly unmarried mothers. A large minority of studies utilized multiple waves of data (n = 27), and most of these studies (n = 20) employed data analytic techniques (e.g., fixed, random, or mixed effect modeling or controlling for social support at earlier waves) to address potential causation issues (e.g., does low informal support cause depression or does depression cause low informal support?) to maximize the probability that relationships were in the hypothesized directions.

Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies of Informal Support Among Low-income Mothers Classified by Dependent Variable1

| Author | Data Study & Sample | Valid N/Analytic Techniques & Role of Support | Operationalization of Informal Support | Additional Key Variables2 | Findings Related to Informal Support | Quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Informal Support | ||||||

| Harknett and Hartnett (2011) | FFCWBS BA, Y1, Y3, & Y5 | n = 4,618 mothers pooled longitudinally & 12,140 person- waves of data/Random effects models with support as DV | Instrumental support: sum of 3 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan; Emotional support: someone to share confidence with | IVs: poverty level, physical and mental health problems, and childrearing burden | Poverty, poor physical health, and poor mental health related to lower levels of instrument support, and, to a lesser extent, lower levels of emotional support. | 7 |

| Harknett and Knab (2007) | FFCWBS BA, Y1, & Y3 | n = 12,259 person-waves of data; Logistic regression with support as DV | Dichotomous indicator based on whether mothers had access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan | IV: whether the mother or the father had a previous childbearing partner | Most mothers had access to $200 (88%), a place to live (88%), or child care (91%). 80% perceived access to all 3 types of support. Multipartnered fertility related to weaker safety nets. | 7 |

| Meadows (2009) | FFCWBS Y1, Y3, & Y5 | n = 2,953–3,972/logistic regression with support as an IV & a DV | Dichotomous indicator based on whether mothers had access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan | DV: depression Other variables: received support | At Y1, a partner, higher education, more income, higher future support availability, and having higher levels of received support in past year related to increased Y3 support. | 7 |

| Osborne, Berger, and Magnuson (2012) | FFCWBS Baseline, Y1, Y3, & Y5 | n = 3,399/HLM models with support as DV | Sum of 3 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan | IV: family structure | Mothers in stable relationships with the focal child’s father between Y1 & Y5 surveys perceived more informal support at both Y1 & Y5 surveys compared with mothers consistently single or experiencing transitions. Transitioning to single-mother family related to less support. | 7 |

| Radey (2015) | WCF Baseline | n = 2,219; OLS regression with support as DV | Summed index of 4-item, 3-point scale of access to someone to: (a) listen to your problems when you’re feeling low, (b) take care of your children, (c) help with small favors, and (d) loan you money in an emergency. | IV: Excess network burden | Mothers averaged 5.37 on the 8-point support scale. Less than one fourth of mothers had enough people to count on in all realms. 76% of mothers lacked support in all four domains. Excess network burden related to less support. | 7 |

| Radey and Brewster (2013) | FFCWBS Baseline, Yl, Y3, & Y5; unmarried mothers at BA | n = 3,065 & 10,650 person- year observations/HLM models with support as DV | Dichotomous indicator based on whether mothers had access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan | IV: Passage of time from the child’s birth to age 5 | 82% of mothers reported a complete safety net. 40% of mothers lost or gained at least one safety-net component in their child’s first 5 years. Of mothers with unstable support, only 13% gained and kept a net. Support decreased as children aged and the most vulnerable mothers were left without support. | 7 |

| Su and Dunifon (2016) | FFCWBS Yl, Y3, Y5 & Y9, employed mothers | n = 2,716 & 6,839 person- waves of data/OLS regression, propensity- weighted regression, within-person fixed effects, & residualized change models with support as DV | Sum of 3 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan | IV: Non-standard work schedules | Nonstandard schedules were associated with weaker support, particularly for Blacks and less- educated mothers. Changing from a standard to a nonstandard schedule was associated with small improvements in support. | 7 |

| Turney and Harknett (2010) | FFCWBS Yl, & Y3 | n = 3,871 −4,211/Poisson regression models with support as a DV | (1) Sum of 6 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, (c) $200 loan, (d) $1,000 loan, (e) a cosigner for $1,000 loan, (f) a cosigner for a $5,000 loan in an emergency (2) Sum of a-c; (3) Sum of d-f | Neighborhood disadvantage; residential stability | 83–88% of mothers had small amounts of monetary, housing, and child care support available. Less than 50% of mothers had someone to loan them $1,000, and only 40% had someone to cosign a $5,000 loan. On average, mothers had 4 of 6 supports. Living in a disadvantaged neighborhood and residential instability were associated with less support. Support networks existed in disadvantaged neighborhoods, but lacked the means to provide large monetary assistance. | 7 |

| Turney and Kao (2009) | ECLS-K and 2nd follow-up (1st grade) | n = 12,580/OLS regression with support as DV | Sum of 6-item on 3-point scale: access to someone to watch child to run errand; a ride to get (child) to doctor; if (child) is sick, friends or family will check on; someone to talk things over with if (child) is having school problems; someone to loan money in an emergency; someone to talk about troubles or get advice | Race, Immigrant Status, and Ethnicity | Support was inversely related to need such that immigrants, single parents, those unemployed, those with less education, those in larger households, those with depressive symptoms, and those with more residential moves perceived less support. | 7 |

| Turney, Schnittker, and Wildeman (2012) | FFCWBS Baseline, Y1, Y3, & Y5 | n = 4,132/OLS regression with lagged DV with support as DV | Sum of 3 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan Sum of 3 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) $1,000 loan, (b) cosigner for $1,000 bank loan, and (c) cosigner for $5,000 bank loan. | IV: whether or not mother shared children with a recently incarcerated man | Mothers averaged 4 of the 6 types of support, most commonly non- financial support. Less than half reported access to large financial support. Mothers who shared children with recently, but not currently, incarcerated men reported less non- financial support and less large financial support. | 7 |

| B. Maternal Health & Wellbeing | ||||||

| Ajrouch, Reisine, Lim, Sohn, & Ismail (2010a) | Mothers of low- income children living in Detroit, MI | n = 969/OLS with suppo as mediator | (1) Instrumental support: summed index of support whether they had someone they could count on: (a) if they needed someone to run errands, (b) lend rt money, (c) watch the child/children (d) lend a car or give a ride; (2) Emotional support: whether they had someone they could count on to give encouragement | DV: psychological distress; Other IVs: perceived discrimination | Instrumental support exerted a buffering effect to mitigate the negative influence of moderate levels of perceived discrimination on psychological distress. Emotional support was associated with less psychological distress. | 7 |

| Ajrouch, Reisine, Lim, Sohn, and Ismail (2010b) | Mothers of low- income children living in Detroit, MI | n = 736/OLS with support as mediator | (1) Instrumental support: summed index of support whether they had someone they could count on: (a) if they needed someone to run errands, (b) lend money, (c) watch the child/children (d) lend a car or give a ride; (2) (2) Emotional support: whether they had someone they could count on to give encouragement | DV: psychological distress; Other IVs: food insufficiency, neighborhood disorganization | Instrumental support provided some protection from everyday stress, yet did little for those under acute stress (e.g., high food insecurity; high neighborhood problems). | 7 |

| Beilin, Osteen, Kub, Bollinger, Tsoukleris, Chaikind, and Butz (2015) | Caregivers—mostly mothers—of inner-city children with asthma aged 3 to 10 years | n = 300/Latent growth curve modeling with support as mediator | Summed index of emotional/informational support subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study. The eight-item 5-point Likert scale asks respondents to reflect on support availability in several situations (e.g., “to listen to you when you need to talk”; “to turn to for suggestions about how to deal with a personal problem’). | DV: Quality of life (QOL); Other IVs: life stress | Although the bivariate association was significant in the latent growth curve model, support was not directly related to caregiver QOL. Informal support did not mediate relationships between asthma burden, life stress, and QOL. However, more than one- third of respondents had the highest possible support score, and 70% of caregivers scored 75% or higher. | 7 |

| Burdette, Hill, and Hale (2011) | WCF Study baseline and Y3 | n = 2045–2313/OLS regression with support as mediator | Emotional: how many people respondents could count on to listen to their problems when they were feeling low | DV: psychological distress; Other IVs: household disrepair | Although support related to better mental health, it did not mediate or explain the association between disrepair and distress. | 7 |

| Crocker and Padilla (2016) | FFCWBS Y3 | n = 2,858/Logistic regression with support as IV | Sum of 4 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) $200 loan, (b) $1000 loan, (c) a cosigner for $1,000 bank loan, and (d) cosigner for $5,000 bank loan | DV: life satisfaction | Support was positively related life satisfaction. Relationship was a gradient such that mothers with the most assets had the highest odds of life satisfaction. | 7 |

| Dauner, Wilmot, and Schultz (2015) | FFCWBS Y5 & Y9 | n = 3,284/Logistic regression with support as IV | Sum of 6 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, (c) trust someone to look after child if away, (d) $200, (e) consigner for $1,000 bank loan, and (f) someone to share confidence with. Instrumental support: 6-item | DV: self-rated health | Net of socioeconomic, demographic, and behavioral variables, mothers with informal support had higher odds of reporting favorable health (excellent, very good, or good vs. fair or poor). | 7 |

| Israel, Farquhar, Schulz, James, and Parker (2002) | Survey through East Side Village Health Worker Partnership in Detroit, MI. Black women aged 18 and older living in area with minor children in care | n = 679/OLS regression with support as IV | scale, measured access to tangible support including transportation, money, and child care Emotional support: 3-item scale measured access to others for advice or share private worries. Caregivers categorized into high, medium, and low based on distribution for each support type. | DV: Self-rated health; depression Other IVs: chronic stress | Instrumental and emotional support both related to better health. When both were included in the model, instrumental support, and not emotional support, remained as a significant predictor of health outcomes. | 7 |

| Kingston (2013) | Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods longitudinal study Wave 3 | n = 1,957/HLM procedures with support as a mediator | Sum of the Provision of Social Relations Scale (Turner et al., 1983): 13-items using 3-point scale for items such as: “People in my family help me find solutions to my problems” and “I feel very close to some of my friends. “ | DV: depression; IV: economic adversity, neighborhood violence | Support related to fewer depressive symptoms. The effects of informal support were strongest in high-SES neighborhoods and weakest in low- SES neighborhoods. | 7 |

| Manuel, Martinson, Bledsoe- Mansori, and Bellamy (2012) | FFCWBS Baseline, Yl, Y3, & Y5 | n = 3675/GEE with time- lagged effects with support as IV | Sum of 3 dichotomous indicators in an emergency: access to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan | DV: maternal depression symptoms; Other IVs: stress | Support related to lower levels of depression and offset negative effects of stress, but only to a certain degree. No significant support interactions between hardship, stress, or health reached significance. | 7 |

| Meadows (2009) | FFCWBS Yl, Y3, & Y5 | n = 2,953–3,972/logistic regression with support as an IV & a DV | Dichotomous indicator based on whether mothers had access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan | DV: depression Other variables: received support | Support decreased odds of experiencing a future major depressive episode. | 7 |

| Omelas and Perreira (2011) | Latino Adolescent Migration, Health, and Adaptation Project of first- generation Latino youth and their parents, mostly mothers, in NC | n = 246/Logistic regression with support as an IV | Summed scale of 4-point Likert, 12-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL-12) regarding availability of several supports, such as practical help, advice, and companionship | DV: depression; IV: characteristics of migration | Support negatively related to depression. | 6 |

| Orthner, Jones- Sanpei, and Williamson (2004) | low-income subsample of parents living with their minor children from an annual random, telephone sample of NC households | n = 373/Logistic regression with support as an IV | Separate dichotomous measures as to whether parents could (a) turn to friends when a problem occurs that their household cannot handle or (b) talk to others for help | DV: confidence in solving everyday problems, meeting needs, and getting children into activities Other IVs: family assets | Support increased odds that parents had confidence in their ability to solve problems and meet various needs. | 6 |

| Paxson, Fussell, Rhodes, and Waters (2012) | Opening Doors Study in New Orleans; low- income, community college mothers | n = 532; Multinomial regression with support as IV | Average scale of 4-point Likert, 8-item social support subscale from the Social Provisions Scale (Cutrona & Russell, 1987; e.g., “I have a trustworthy person I can turn to if I have problems.”) | DV: psychological distress, posttraumatic stress symptoms | Support related to less psychological distress at second follow-up. | 6.5 |

| Reid and Taylor (2015) | FFCWBS Baseline & Yl | n = 4150/SEM procedures with support as IV and mediator | Sum of 5 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan, (d) $1,000 loan, and (e) cosigner for $1,000 loan | DV: postpartum depression; Other IVs: stress exposure | Support negatively related to depression. Stress negatively related to support. Support did not mediate the relationship between stress and depression. | 7 |

| Sampson, Villarreal, and Padilla (2015) | FFCWBS Baseline & Yl, mothers with romantically involved with child’s father Yl | n = 2,412/OLS regression with support as IV | Sum of 3 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan & dichotomous indicator of access to all three supports | DV: maternal stress | Support was related to lower depression. Support did not influence maternal stress. | 7 |

| Schulz, Israel, Zenk, Parker, Lichtenstein, Shellman- Weir, & Klem (2006) | Random sample survey conducted in 1996 in a geographically defined area on Detroit’s Eastside of Black caregivers, primarily mothers | n = 679/SEM procedures with support as a mediator | 6-item, 4-point Likert summed scale based on access to (a) assistance to care for them if sick, (b) help around the house, (c) watch children for a few hours, (d) move furniture, (e) give monetary assistance, and (f) provide transportation | DV: depression symptoms; IVs: income, years of residence, financial stress, police stress, safety stress | Length of residence positively related to informal support. Informal support partially mediated the relationship between household income and symptoms of depression. | 7 |

| Surkan, Peterson, Hughes, and Gottlieb (2006) | Mothers selected from health center obstetrical and pediatric patient lists inNE US city | n = 415/OLS regressions with support as IV | 20-item, 5-point scale Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (Sherboume & Stewart, 1991) including having someone to give advice, confide in, and listen to you; Having 2+ friends or family members available | DV: Depression; Other IVs: sociodemographic characteristics | Informal support related to fewer depression symptoms and acted like a gradient such that as support increased, depression symptoms decreased. | 6.5 |

| Turner (2006) | Data from telephone interviews with unmarried women age 18–39 living with dependent, minor children in rural areas of NE | n = 508/OLS regression with support as an IV | Mean scores of 9-item, 4-point Likert scale of a modified version of the Provisions of Social Relations Scale (Turner, 1983) including attachment, social integration, reassurance of worth, reliable alliance, and guidance for (a) family and (b) friends. | DV: depression; Other IVs: stress; marital status | Although both friend and family support directly related to depressive symptoms, support from neither source buffered the negative effects of stress. Divorced mothers also benefited less from emotional support from family members than did never- married mothers. | 7 |

| Wilmot and Dauner (2016) | FFCWBS Y5 & Y9 | n = 3474/Logistic regression with support as IV | Sum of 6 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) place to stay, (b) child care, (c) $200 loan, (d) $1,000 loan, (e) cosigner for $1,000 bank loan, and (f) cosigner for $5,000 bank loan | DV: depression; Other IVs: neighborhood characteristics | Support related to lower odds of depression net of extensive controls including prior depression and prior self-rated health. | 7 |

| C. Economic Wellbeing | ||||||

| Ciabattari (2007) | FFCWBS Y1; unmarried mothers who had been employed since giving birth | n = 1,676/OLS, Multinomial regression with support as IV | Sum of 4 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, (c) $200 loan, and (d) consigner for $1,000 loan | DV: work-family fit, employment status; Other IVs: family structure, income | Support was negatively related to work-family conflict, but did not significantly influence employment status. | 7 |

| Fertig and Reingold (2008) | FFCWBS Y1 & Y3; mothers at or below 50% of poverty level or homeless | n =1,262; Multinomial logistic regression with support as IV | 3 separate dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to live, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan | DV: homelessness or doubling up | Support was related to less doubling up and less homelessness. | 7 |

| Hanson and Olson (2012) | Rural Low- Income Families Project; families under 200% of poverty level with at least one child under age of 13 | n = 225/Multinomial regression with support as mediator | Parenting Support Ladder. Respondents ranked themselves on six-point scale on 5 indicators: someone to talk to, to offer advice or moral support, to help in an emergency, and to relax with, professionals to talk with, and overall satisfaction with parenting. Parents in the highest quartile of support were distinguished from those in the lower quartiles. | DV: food security Other IVs: human capital, financial resources, expenses | Mothers with no food insecurity had higher levels of support than mothers with persistent or discontinuous food insecurity. | 6.5 |

| Henly, Danziger, and Offer (2005) | Women’s Employment Survey Waves 1 & 3; single TANF mothers at Wave 1 | n = 632/OLS regression, OLS regression lagged model, change analysis, SEM procedures with support as IV | Time 1: Summed index based on 6 dichotomous indicators of access to someone: (a) to buy child’s shoes, (b) lend money, (c) to watch child, (d) give a ride, (e) to check on us when my child is sick, (f) to talk to when have troubles. Time 2: Average scale score from 7-item, 5-point Likert score on subscale from Social Relationships Scale (O’Brien et al., 1993). Items include access to someone: (a) if you were upset, nervous, depressed; (b) to talk about personal problem; (c) to help take care of you if you were confined to bed; (d) to barrow $10, ride to doctor; (e) to barrow several hundred dollars for medical emergency; (f) to get information or guidance; (g) for advice. | DV: material wellbeing; Other IVs: economic status, coping strategies, economic status variables | Mothers with the most need reported the least access to support. Support related to less perceived and actual economic hardship and decreased odds of engaging in extra-network coping activities, such as selling blood or plasma. The advantage did not extend to earnings or job quality. | 7 |

| King (2016) | FFCWBS Y3 & Y5 & in-home assessments | n = 2481/Difference-in- difference approach with support as a mediator | Sum of 4 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, (c) $200 loan and (d) consigner for $1,000 loan | DV: housing instability; IVs: food insecurity, material hardship, maternal depression | Support partially mediated the relationship between food insecurity and housing insecurity accounting for 5% of the mediation. | 6.5 |

| Staggs, Long, Mason, Krishnan, and Riger (2007) | The Illinois Families Study, a 4-year statewide study of families who received welfare in the Fall, 1998 | n = 1,315; OLS regression with support as IV and mediator | Summed index of 4-item, 3-point scale of access to someone to: (a) listen to your problems when you’re feeling low, (b) take care of your children, (c) help with small favors, and (d) loan you money in an emergency. | DV: employment stability; Other IVs: IPV | Support related to more stable future employment. Current employment stability did not predict future support. Support did not predict future IPV, and support did not mediate the relationship between IPV and employment stability. | 6.5 |

| Usdansky and Wolf (2008) | FFCWBS Baseline, Yl & Y3, mothers who used nonparental child care at Y3 | n = 1309/Logistic regression with support as IV | Sum of 6 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) place to stay, (b) child care, (c) $200 loan, (d) $1,000 loan, (e) cosigner for $1,000 bank loan, and (f) cosigner for $5,000 bank loan | DV: Child care disruption; missed work due to child care | Support related to less child care disruption and less days of missed work due to child care. | 7 |

| Wu and Eamon (2010) | Survey of Income and Program Participation (1996, 2001), householders (mostly mothers) with children living at 185% of poverty or less | n = 3649/Logistic regression with support as an IV | Dichotomous indicator based on whether householders expected to receive all or most of the help needed with problems (e.g., sickness, moving) from family or friends living nearby. | DV: need for public benefits; IVs: public benefit receipt; informal support receipt | Support related to lower perceptions of income-based need for public benefits. | 6.5 |

| D. Parenting Stress & Outcomes | ||||||

| Cardoso, Padilla, and Sampson (2010) | FFCWBS Baseline and Y1 | n = 2998/OLS regression with support as IV | Sum of 3 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan | DV: Parenting stress; Other IVs: Race and Ethnicity | Support was negatively associated with parenting stress. | 7 |

| Green, Furrer, and McAllister (2007) | National evaluation of the Early Head Start program; urban, African American, low- income parents of children 14–36 months | n = 152/Path models with support as IV | Summed scale of the Social Provisions Scale (Cutrona & Russell, 1987) consisting of 22, 4-point Likert response items, including tangible support, emotional support, advice or appraisal support, and esteem support. | DV: parent-child activities; Other IVs: parent anxiety; parent avoidance, parent ambivalence | Support related to less parental anxiety about relationships, and in turn, parents with less relationship anxiety and ambivalence showed greater increases over time in their level of engagement with their children. | 6.5 |

| Hill, Burdette, Regnerus, and Angel (2008) | WCF Study baseline and Y3 | n = 2344/OLS regression with support as a mediator | Summed scale of 4-item, 3-point scale of access to someone to: (a) listen to your problems when you’re feeling low, (b) take care of your children, (c) help with small favors, and (d) loan you money in an emergency. | DV: Attitudes towards parenting IVs: religious involvement, self esteem, psychological distress | Support did not mediate the association between religious attendance and parental satisfaction or perceived demands. To a small extent, support mediated the association between religious attendance and parental distress. | 7 |

| Jones, Forehand, O’Connell, Armistead, and Brody, (2006) | A community sample of singlemother, low- income Black families with a child 7–15 years in Southeast US. | n = 248; OLS regression with support as a mediator | Summed scale of 5-item, 6-point scale of access to friends/neighbors to: (a) watch your home for a few days? (b) watch your children for a few hours while you are away suddenly? (c) help if you cannot do something yourself? (d) get together for a party? Are most of your contacts with your neighbors ? (rated very positive to very negative). | DV: Maternal monitoring; IVs: Neighborhood risk | Support related to higher levels of maternal monitoring. Perceptions of dangerous neighborhoods heightened the positive relationship between higher levels of support and maternal monitoring. | 7 |

| Jackson, Gyamfi, Brooks-Gunn, and Blake (1998) | Black, single mothers of preschoolers and former or current welfare recipients recruited through the public employment office in New York City | n = 188/OLS regressions with interactions with support as IV | Summed scale of 4-item, 6-point scale of access to someone to (a) watch my child(ren) if I need to run an errand, (b) provide a ride to get my child to the doctor, (c) provide cash for me to buy my child shoes, (d) to cope with at the end of a long day | DV: spanking; Other IVs: Maternal depression, stress, employment, and child behavior | Support related to increased frequency of spanking, especially among mothers with high depression or stress. | 7 |

| Kang (2013) | FFCWBS BA, Yl, Y3, & Y5 | n = 2910/SEM and probit regressions with support as IV | Sum of 4 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, (c) $200 loan and (d) consigner for $1,000 loan | DV: child neglect; Other IVs: material hardship and personal control | Support had an indirect effect on neglectful parenting by reducing material hardship and increasing personal control. | 7 |

| Kenigsberg, Winston, Gibson, and Brady (2016) | Black sample of primarily mothers from low-income elementary school in MW US | n = 46/OLS regression with support as IV | Sum of Social Provisions Checklist (Davis et al., 1998): 6, 5-item perceived support subscales: (a) Attachment (e.g., emotional closeness); (b) Reassurance of worth (e.g., appreciation of abilities); (c) Guidance (e.g., trustworthy advice); (d) Reliable alliance (e.g., reliable help); (e) Social integration; (e.g., feeling of being included); (f) Opportunity to nurture (e.g., feeling of being needed) | DV: children’s perception of support from caregiver, conflict with caregiver; Other IVs: Stressful life events, affective symptoms | Support was associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and children’s report of greater caregiver instrumental support and emotional support to a lesser degree. | 7 |

| Kimbro and Schachter (2011) | FFCWBS BA, Yl, Y3, & Y5 | n =3,448/Fixed effects logistic regression with support as IV | Dichotomous indicator based on whether mothers had access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan | DV: maternal fear of child playing outside; Other IVs: neighborhood, mental health | Support related to less maternal fear of letting child go outside to play due to violence. | 6.5 |

| Kotchick, Dorsey, and Heller (2005) | Low-income, urban Black single mothers recruited from Family Health project in New Orleans | n = 123/SEM procedures with support as a mediator | Sum of 6-item, 4-point Likert scale of support from friends; Sum of 5-item, 4-point Likert scale of support from family (e.g., ease of getting help from a neighbor with something that you can’t do yourself; are your contacts with neighbors scale: positive to negative) | DV: engagement in positive parenting; IVs: neighborhood stress, maternal stress | Support moderated the relationships among high neighborhood stress, high psychological distress, and less engagement in positive parenting practices raising the vulnerability of mothers with little support. | 6.5 |

| Lee (2009) | FFCWBS Yl & Y3 & in-home assessments; mothers 19 years or younger and adult mothers 26 years or older at Baseline | n = 1387–1,813/Negative binomial regression with support as IV | Sum of 4 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, (c) $200 loan, and (d) consigner for $1,000 loan | DV: harsh parenting; Other IVs: human capital, cultural capital | Support related to increased physical aggression in parenting and spanking. | 7 |

| Prelow, Weaver, Bowman, and Swenson (2010) | WCF Baseline and Y3; Latina caregivers of young adolescents | n = 535/SEM procedures with support as a mediator | Summed index of 4-item, 3-point scale of access to someone to: (a) listen to your problems when you’re feeling low, (b) take care of your children, (c) help with small favors, and (d) loan you money in an emergency. | DV: parenting behaviors; IVs: financial strain, neighborhood & housing problems, psychological distress | Support mediated the impact of ecological risk on the quality of mothers’ parenting behaviors by decreasing mothers’ psychological distress. | 7 |

| Raikes and Thompson (2005) | Mothers of toddlers enrolled in Early Head Start in a midsized city in the Midwest. | n = 65/OLS regression with support as a mediator | Summed 5-item subscale of the Dunst Family Resource Scale (Dunst & Leet, 1987; e.g., having someone to talk to, having babysitting and childcare for children); average of T1 and T2 scores | DV: Parenting stress; IVs: Self- efficacy | Support was not related to lower parenting stress levels. Support did not moderate the effect of income on parenting stress. | 6.5 |

| Shanahan, Runyan, Martin, and Kotch (2017) | subset from the Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect database; mothers of children at-risk | n = 505/Logistic regression with support as a mediator | Functional Social Support Questionnaire: 5-item, 10-point Likert summed scale containing confidant support, affective support, and instrumental support (e.g., people care what happens to me) | DV: physical neglect IVs: depression, history of maltreatment, neighborhood quality | Support did not moderate the relationships between the predictors (depression, neighborhood quality, caregiver history of maltreatment) and physical neglect. | 6 |

| Taraban et al. (2017) | for maltreatment and controls Early Steps Study, randomized intervention trial of families with 2-year olds recruited from WIC centers in 3 US cities & 1 | n = 131/OLS regression with support as a mediator | Mean score of 8-item, 4-point Likert subscale from the General Life Satisfaction Questionnaire including availability and satisfaction with social support in 3 areas: intimate relationships, friendships, and neighborhood | DV: Parenting; IVs: Depression, marital quality | Support moderated the negative relationship between depression symptoms and positive parenting behavior only among mothers not married or cohabiting. | 5.5 |

| Woody and Woody (2007) | year follow up Black mothers between 19 & 26 years who were parenting at a child 4 years of age or older recruited from the public welfare office or Head Start center | n = 135/OLS regression with support as an IV | Mean score of 45-item, Likert- scale Social Support Behaviors Scale (Vaux, Riedel, & Stewart, 1987) that measures available advice/guidance, emotional support, financial assistance, practical assistance, and socializing from family and friends. | DV: Parenting effectiveness | Support related to increased parenting effectiveness. | 6.5 |

| E. Child Outcomes | ||||||

| Choi and Pyun (2014) | FFCWBS BA, Yl, Y3, in-home Y3 & Y5; low- income unmarried mothers | n = 679/SEM procedures with support as IV | Sum of 4 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, (c) $200 loan, and (d) consigner for $1,000 loan | DV: child behavior, child cognitive development; Other IVs: maternal hardship, parenting | Support was directly and indirectly associated with cognitive development and behavior problems of children transmitted through maternal economic hardship, parenting, and parenting stress. | 7 |

| Ghazarian and Roche (2010) | WCF study Baseline & Y3; Latina and African American mothers of youth ages 10–11 at Baseline | n = 432/SEM procedures with support as IV & mediator | Summed index of 4-item, 3-point scale of access to someone to: (a) listen to your problems when you’re feeling low, (b) take care of your children, (c) help with small favors, and (d) loan you money in an emergency. | DV: adolescent delinquency; Other IVs: Maternal depression, engagement | Support related to increased engaged parenting and, consequently, lower levels of delinquent behavior. | 7 |

| Jackson (1998) | Black, singlemothers of preschoolers and former or current welfare recipients recruited through the public employment office in New York City | n = 188/OLS regressions with interactions with support as IV | Summed scale of 4-item, 6-point scale of access to someone to (a) watch my child(ren) if I need to run an errand, (b) provide a ride to get my child to the doctor, (c) provide cash for me to buy my child shoes, (d) to cope with at the end of a long day | DVs: Maternal depression, parent stress, and child behavior; Other IVs: child contact with father, maternal satisfaction with child’s father | Support related to fewer depression symptoms. Symptoms of depression, in turn, predicted greater parental stress, which predicted reports of more child behavior problems. | 7 |

| Jackson, Brooks-Gunn, Huang, and Glassman (2000) | Employed, Black, single mothers of preschoolers and former or current welfare recipients recruited through the public employment office in New York City | n = 93/Path analysis with support as IV | Summed scale of 4-item, 6-point scale of access to someone to (a) watch my child(ren) if I need to run an errand, (b) provide a ride to get my child to the doctor, (c) provide cash for me to buy my child shoes, (d) to cope with at the end of a long day | DVs: Maternal depression, parenting behavior, and child behavior; Other IVs: perceptions of financial strain | Support related to less financial strain. Financial strain, in turn, related to higher depressive symptoms, which were directly and negatively implicated in parenting quality. Parenting quality related to children’s behavior problems and preschool ability. | 7 |

| Jackson, Preston, and Thomas (2013) | Black, single mothers of preschoolers and former or current welfare recipients recruited through the Pittsburgh welfare office | n = 99/SEM procedures with support as IV | Summed scale of 4-item, 6-point scale of access to someone to (a) watch my child(ren) if I need to run an errand, (b) provide a ride to get my child to the doctor, (c) provide cash for me to buy my child shoes, (d) to cope with at the end of a long day | DV: child behavior problems | Support was associated with more adequate parenting at T1 (age 3) and through parenting to child behavior problems at T2 (age 5). | 7 |

| Jung, Fuller, & Galindo (2012) | ECLS-B Baseline and 3-year follow-up | n = 4,400 mother- father pairs/OLS & logistic regressions with support as a mediator | Dichotomous indicator: whether mother has kin member or friend available to lend support in the event of a family emergency | DV: Child’s early learning IV: Nativity, family functioning | Support not significantly related to maternal social-emotional functioning or maternal reading practices. | 6.5 |

| Lee, Lee, and August (2011) | Caregivers of child at risk of behavior problems in school districts in rural MN | n = 290/HLM procedures with support as a mediator | Sum of 40-item 4-point, Likert scale, Interpersonal Support Evaluation List including appraisal, tangible, self-esteem, and belonging domains | DV: externalizing behaviors IVs: income, depression, parenting practices | Support mediated the relationship between lower family income and both less positive parenting and children’s externalizing behaviors. | 6.5 |

| Leininger, Ryan, and Kalil (2009) | National evaluation data of single-mother welfare recipients with young children in 3 US cities Baseline, Yl, & Y5 | n = 1280/logistic regression with time-lagged effects with support as IV | Quartile score based on 10-point, 5-item scale: (a) if mothers could ask someone for cash for to buy child’s shoes, (b) to watch child if need to run errands, (c) to give a ride to get child to doctor, (d) to check on us when my child is sick, (e) to talk to when have troubles | DV: whether or not child experienced an accident, injury, or poisoning that required ER visit or clinic between Yl and Y5 | Mothers with the least amount of informal support had increased odds of their child experiencing an injury compared to other mothers. | 7 |

| Mistry, Lowe, Benner, and Chien (2008) | Mixed-methods approach from the New Hope project; low- income mothers had dependent between 1–10 years at Baseline | n = 516/SEM procedures with support as IV | Sum of 4-point Likert, 4-item scale if she could rely on (a) family, (b) friends, or (c) neighbors to help out if they were in a jam and (d) if any adults could help them out financially in a pinch | DV: economic hardship, children’s behavior; Other IVs: maternal economic stress, psychological wellbeing, parent practices | Support negatively related to economic pressures, indirectly relating to positive children’s behavior through maternal psychological wellbeing and parenting practices. | 7 |

| Padilla, Hamilton, and Hummer (2009) | FFCWBS Baseline & Y5 | n = 2,819/Logistic regression with support as IV | Access to $1,000 loan | DV: child chronic health condition or asthma | Support not related to prevalence of child chronic health conditions or asthma. | 6.5 |

| Reynolds and Crea (2014) | Parents of 11–14 year-old, urban youth attending summer camp in Boston. | n = 781/SEM procedures with support as a mediator | Summed 4-item 5-point Likert scale items based on if parents perceived a strong support network, support from family and relatives, support from church or place of worship and support, and support from neighbors | DV: Adolescent behaviors; IVs: Household stress, mental health | Support related to prosocial activities in adolescents and less poor mental health outcomes for parents. Support related to reduced parent depression and anxiety, which in turn decreased youth vulnerability. Support was not directly related to youth vulnerability. | 7 |

| Ryan, Kalil, and Leininger (2009) | FFCWBS Yl, Y3, & Y5, unmarried mothers; National evaluation data of single-mother welfare recipients with young children | n = 1,162 and 1,308/OLS regression and residualized change models with support as IV | Summed index categorized as low, medium, high based on whether mothers had: access to a place to stay, child care, $200, $1,000, cosigner for $1,000 loan, and cosigner for $5,000 loan in an emergency; Summed 10- point, 5-item scale: (a) if mothers could ask someone for cash for to buy child’s shoes, (b) to watch child if need to run errands, (c) to give a ride to get child to doctor, (d) to check on us when my child is sick, (e) to talk to when have troubles | DV: children’s socioemotional well-being | Support related to a decrease in children’s internalizing symptoms and an increase in pro-social behavior. | 7 |

| Turney (2012) | FFCWBS Baseline, Yl, Y3, Y3 in-home, Y5, & Y9 | n =2655/OLS regression and propensity score matching with support as IV | Instrumental support: Sum of 3 dichotomous indicators: access in an emergency to (a) a place to stay, (b) child care, and (c) $200 loan; Emotional support: presence of a confidante; # of close friends | DV: Child behaviors; Other IVs: depression | Support related to less depression, but did little to attenuate the relationship between depression and poor child behaviors. | 7 |

| Turney (2013) | FFCWBS Baseline, Yl, Y3, Y5, & Y9 | n = 4342/Pooled ordered logistic and fixed effect regressions with support as IV | Instrumental support: Sum of 6 dichotomous indicators categorized into low, medium, and high support: access in an emergency (a) to a place to stay, (b) child care, (c) $200 loan, (d) $1,000 loan, (e) cosigner for $1,000 bank loan, and (f) cosigner for $5,000 bank loan in an emergency; Emotional support: presence of a confidante; # of close friends | DV: child’s general health; overweight/obese; asthma, # of ER visits | Support positively related to overall child health with extensive controls, a lagged indicator of children’s health, and in fixed-effect models. The relationships between support and asthma, overweight/obese, and number of emergency room visits were not significant after controls. | 7 |

Acronyms:

BA: Baseline

DV: Dependent variable

ER: Emergency Room

ECLS-B: Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Birth Cohort

ECLS-K: Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Kindergarten Cohort

FFCWBS: Fragile Families and Child Well Being Study

GEE: Generalized Estimating Equations

HLM: Hierarchical Linear Modeling

IV: Independent variable

OLS: Ordinary Least Squares

SEM: Structural Equation Modeling

WCF: Welfare, Children, Families: A Three City Study

Y1, Y3, Y5, Y9: Year

Most models included an extensive number of control variables. Rather than an exhaustive list, stated variables are central to the article’s focus.

Results

Table 1 provides an overview of each analyzed study including the sample, analytic techniques, operationalization of informal support, additional key study variables, and study findings related to informal support. The table is organized by studies’ dependent variables. To conserve space, when study authors included multiple mediating or dependent variables, the study is classified according to the most distal outcome. For example, Choi and Pyun’s (2014) study examined support’s role in maternal hardship, parenting, parenting stress, child cognitive development, and child behavior. The article was classified under Child Outcomes. One study (i.e., Meadows, 2009) analyzed social support as both a dependent variable and an independent variable; it was the only article classified twice.

Various Measurements of Informal Support

Included studies used a variety of instruments, indexes, and items to measure instrumental and emotional informal support (See Table 1, Column Operationalization of Informal Support). Although studies generally conceptualized support similarly (e.g., mothers’ ability to turn to others for support), nomenclature included social support, social capital, perceived support, instrumental support, private safety nets, and maternal resources. Operationalization differed both within and across datasets depending on study focus and available items in each study wave. For example, of studies using the FFCWBS (n = 27), study authors created a dichotomous item indicating whether or not mothers had access to child care, housing, and a place to live (n = 4), examined multiple, dichotomous indicators separately (n = 1), created single indexes with 3–6 support indicators (n = 18), used multiple indices often differentiating between small and large financial support (n = 3), or used a single indicator of financial access (n = 1). The majority of included studies measured instrumental support only (n = 28) or a combination of instrumental and emotional support (n = 24); the remainder did not specify support type (e.g., general availability of support from intimate relationships, friends, and neighborhood; n = 2) or examined emotional support only (n = 1).

The range of informal support measures suggests the ambiguous nature of support. The development and evolution of the FFCWBS highlights the ambiguity of the construct. At Baseline, study investigators created three dichotomous support indicators (i.e., someone in your family to provide you with the following in an emergency: $200, child care, and a place to live). The wording changed at Wave 2 to ask if mothers had someone, not necessarily in the family. Later-wave surveys included additional items regarding access to $1,000, bank cosigners for $1,000 and $5,000 loans, and emotional support (i.e., special person that you feel very close with). The Welfare, Children, Families Study, another common data source among the included studies, used a measure constructed just prior to baseline data collection that distinguished if mothers had enough people, too few people, or no one in four areas including money, child care, small favors, and a listening ear (Orthner & Neenan, 1996). These examples highlight the included studies’ commonalities and differences: although the 65 studies operationalized support in 39 ways, measures contained overlapping items and concepts.

Restricted Availability of Informal Support

The consideration of which factors promote informal support availability is a relatively new phenomenon. Ten studies, all published from 2007 through 2016, examined support as an outcome (See Table 1, A. Informal Support). Although exact proportions of availability and amounts of informal support depended upon the measure and the sample, low-income mothers could not universally turn to others for support. In the FFCWBS, approximately 75–90% of primarily unmarried mothers reported access to at least one separate indicator of $200, childcare, and a place to live, and approximately 80% reported access to all three supports (Harknett & Hartnett, 2011; Harknett & Knab, 2007; Radey & Brewster, 2013; Turney & Harknett, 2010). However, in the Welfare, Children, Families Study, when asked to specify whether they had enough, too little, or no support in each of four realms (i.e., practical, child care, financial, and emotional), less than one fourth of inner-city, low-income mothers perceived enough support in all areas. Mothers’ lack of access to greater amounts of financial support (e.g., $1,000, people to cosign loans of $1,000 and $5,000) or their ability to turn to relatively few people may contribute to these differences (Turney & Harknett, 2010; Turney, Schnittker, & Wildeman, 2012).

Studies also provide strong evidence that mothers most in need of support perceived the least amount of access. Single motherhood, immigrant status, poverty, less education, poor physical health, poor mental health, and residential instability related to lower levels of informal support (Harknett & Hartnett, 2011; Henly, Danziger, & Offer, 2005; Meadows, 2009; Turney & Kao, 2009). Vulnerability also predicted unstable support such that the most disadvantaged mothers (e.g., those on public assistance, those in unstable partnerships) experienced a steeper decline in support availability as their children aged than their more advantaged peers (Osborne, Berger, & Magnuson, 2012; Radey & Brewster, 2013).

More limited evidence indicates that conditions typically associated with disadvantage relate to less support. For example, living in a disadvantaged neighborhood (Turney & Harknett, 2010), perceiving social network demands (Radey, 2015), or relying on one’s network recently (Meadows, 2009) related to lower levels of support. In terms of network characteristics, mothers who shared children with recently incarcerated men (Turney et al., 2012) and those with multi-partnered fertility perceived less available support (Harknett & Knab, 2007).

Role of Informal Support in Maternal, Parenting, and Child Outcomes

Fifty-five of the 65 included articles examined the influence of informal support on various maternal health and well-being, economic, parenting, and child outcomes.

Maternal health and well-being outcomes.

Articles most frequently examined maternal psychological well-being characteristics, including depression, stress, anxiety, or psychological distress. Consistently, informal support was positively associated with maternal psychosocial well-being. For example, net of sociodemographic and stress characteristics, for each increase in instrumental support on a 4-point scale, mothers experienced 7% lower odds of depression (Manuel, Martinsom, Bledsoe-Mansori, & Bellamy, 2012). Support was also positively related to maternal personal control (Kang, 2013), confidence (Orthner, JonesSanpei, & Williamson, 2004) and perceived physical health (Dauner, Wilmot, & Schultz, 2015; Israel, Farquhar, Schulz, James, & Parker, 2002).

In instances when informal support was not significantly related to maternal well-being (n = 4), studies measured more global outcomes (e.g., quality of life, maternal functioning) or the support measure captured little variation. For example, in a study of support and quality of life, Bellin et al. (2015) found that although the bivariate relationship between support and quality of life was significant, the relationship in the latent growth curve model was not. In terms of measurement, one-third of caregivers in Bellin et al.’s sample scored the highest possible score on informal support indicating potential ceiling effects such that the measure may not have detected important support differences among high-scoring mothers (e.g., Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988).

Economic well-being.

Nine articles primarily examined informal support’s role in family economic well-being. Without exception, informal support was negatively associated with economic hardship, material hardship (Henly et al., 2005; Jackson, Brooks-Gunn, Huang, Glassman, 2000; Kang, 2013), and need for public assistance (Wu & Eamon, 2010). For example, among a sample of mothers currently and formerly receiving welfare, Henly et al. (2005) found that net of human capital and mental health characteristics, mothers with higher levels of support experienced less economic (e.g., money) and material (e.g., housing, utility) hardship and were less likely to report desperate coping activities (e.g., selling plasma) than mothers with less support. Evidence suggests that informal support’s protective capacity on economic and material hardship does not extend to employment status, job quality, or earnings (Ciabattari, 2007; Henly et al., 2005).

Parenting stress and practices.

A significant minority of studies considered the role of informal supportin parenting stress or practices (n = 20). With few exceptions of no significant effects (Jung, Fuller, & Galindo, 2012 with reading practices; Raikes, & Thompson, 2005 with parenting stress), informal support related to positive parenting, including decreased parental stress and increased parental engagement. For example, Woody and Woody (2007) found that informal support promoted parenting effectiveness according to the Parent Success Indicator for Parents, a self-report instrument including six domains, such as communication, use of time, satisfaction, and frustration.

Commonly, studies (n = 14) examined informal support as a mediator or moderator between maternal or environmental characteristics and parenting outcomes. For example, Green, Furrer, and McAllister (2007) found that mothers with more support perceived less anxiety about their relationships, and, thereby, expressed higher levels of parental engagement. In a sample of low-income, Latina mothers of young adolescents, informal support mediated relationships among ecological risk, psychological distress, and parenting practices such that ecological risk was positively related to maternal psychological distress and informal support was negatively related to maternal psychological distress thereby contributing to higher levels of engaged parenting (Prelow, Weaver, Bowman, & Swenson, 2010).

The exception of informal support’s positive influence on parenting relates to aggressive parenting and spanking (Jackson, Gyamfi, Brooks-Gunn, & Blake, 1998; Lee, 2009). Informal support was related to harsh parenting and spanking among young mothers of toddlers (i.e., mothers less than 22 years old; Lee, 2009). In a sample of urban, low-income Black mothers, Jackson et al. (1998) found that the availability of instrumental support increased spanking frequency, particularly for mothers with high levels of depression and stress. The authors suggested that available instrumental support in low-income networks may come at a psychological cost and the psychological cost may lead mothers to spank their children. Alternatively, the authors suggested that increased spanking may result from low-income mothers’ desire to follow network members’ endorsement of physical discipline (Jackson et al., 1998).

Child outcomes.

Almost 20% of included studies examined the role of informal support in children’s well-being, including cognitive, behavioral, and health outcomes (n = 11).

Child cognitive and behavioral outcomes.

Evidence suggests that informal support promotes cognitive and behavioral outcomes directly (Choi & Pyun, 2014; Ryan et al., 2009) and indirectly through maternal well-being, economic well-being, and parenting behaviors (Choi & Pyun, 2014; Jackson, Preston, & Thomas, 2013; Mistry, Lowe, Benner, & Chien, 2008). Examining direct effects only, Ryan, Kalil, and Leininger (2009) found that informal support was positively associated with prosocial child behavior and negatively associated with child behavior problems. Using structural equation modeling, Choi and Pyun (2014) found that support directly and indirectly related to increased cognitive development and decreased behavior problems of children through lower levels of maternal hardship, lower levels of parenting stress, and healthier parenting interactions. Similarly, Mistry et al.’s (2008) examination of low-income mothers enrolled in New Hope, a welfare-to-work evaluation program, suggested informal support’s promotion of children’s positive behavior indirectly through maternal psychological well-being and parenting practices.

Child health.

From the three studies that examined various components of child health, findings were inconclusive (Leininger, Ryan, & Kalil 2009; Padilla, Hamilton, & Hummer, 2009; Turney, 2013). In the most comprehensive examination of child health outcomes, Turney (2013) found that while informal support was positively associated with children’s overall health net of maternal and child characteristics, individual-level characteristics (e.g., economic status) explained the relationship between informal support and specific indicators of health including child asthma, obesity, and number of emergency room visits. Similarly, Padilla et al. (2009) found that informal support did not relate to the prevalence of child chronic health conditions or asthma. However, using longitudinal data from a sample of mothers receiving welfare, Leininger et al. (2009) found that mothers with little to no informal support had increased odds of their child experiencing an accident, injury, or poisoning that required an emergency room visit.

Aspects of Informal Support that Influence its Effects

Size of informal support’s contribution.

Although the majority of included studies indicate that informal support positively relates to maternal, economic, parenting, and child outcomes, the size of its role in well-being is relatively small and may do little to compensate for the vulnerable environmental conditions of low-income families. Several studies (n = 6) explicitly stated that although informal support contributed to positive outcomes, its contribution was small or did not attenuate the relationships between other modeled variables and maternal, economic, or child outcomes (King, 2016; Manuel et al., 2012; Reid & Taylor, 2015; Shanahan, Runyan, Martin, & Kotch, 2017; Turner, 2006; Turney, 2012). For example, although informal support was consistently related to lower levels of maternal depression, it did little to offset the negative effects of stress (Manuel at al., 2012; Reid & Taylor, 2015; Turner, 2006). Similarly, although informal support mediated the relationship between food insecurity and housing insecurity, it only accounted for 5% of the mediation (King, 2016).

Type of informal support.

Per inclusion criteria, studies examined instrumental or emotional support. Only seven studies included separate measures of emotional and instrumental support. Results suggest that neither support type is uniformly superior. Three studies found the role of instrumental support was more strongly related to outcomes than emotional support (Ajrouch et al., 2010b; Israel at al., 2002; Turney, 2012). For example, after the inclusion of extensive controls, instrumental support—not emotional support—related to depression (Israel et al., 2002; Turney, 2012) and self-reported health (Israel et al., 2002). Others found that emotional and instrumental support related similarly to depression (Jackson, 1998) and children’s health (Turney, 2013). Alternatively, Ajrouch, Reisine, Lim, Sohn, and Ismail (2010a) found that emotional support—not instrumental support—related to lower levels of psychological distress.

Amount of informal support.

Amount of informal support may also influence its relationship to outcomes. Most included studies did not consider if mothers benefited from having a threshold of support (e.g., a safety net) or if informal support acted as a gradient such that mothers benefited incrementally with each increase of support. Of the studies that considered the nature of informal support’s relationship to outcomes (n = 5), two found gradient relationships, one found a threshold relationship, and two found that the type of relationship depended on the outcome. For example, Crocker and Padilla (2016) examined mothers’ access to monetary assets and found a gradient relationship such that mothers with 1–2 assets and those with 3–4 assets had 1.6 and 2.8 higher odds, respectively, of life satisfaction compared to mothers without any assets. However, when considering mothers’ quintiles on a 50-point social support scale and examining child’s risk of experiencing an injury or poisoning requiring an emergency room visit, Leininger et al. (2009) found that at a certain threshold of maternal informal support children were protected from injury: only mothers in the lowest quintile experienced increased odds of an emergency room visit. The importance of informal support’s presence (e.g., a safety net) or volume may depend on the outcome. Israel et al. (2002) found that informal support acted as a gradient for maternal depression and a threshold for maternal general health.

Influence of Family Need on Support

Informal support’s positive relationships to maternal and child well-being raises the question as to whether it operates similarly across low-income mothers regardless of depth of need or if level of disadvantage interacts with informal support. Although reviewed studies all focused on low-income mothers, several studies (n = 15) considered the possibility that informal support interacted with disadvantage (e.g., education, poverty, income, family status) to influence maternal, parenting, and child outcomes. Regardless of examined outcome, studies found mixed results with support more beneficial for those with greater disadvantage (n = 5), less beneficial for those with greater disadvantage (n = 3), or no moderating effects (n = 7).

Studies finding support particularly helpful to disadvantaged mothers examined depression (Ajrouch et al., 2010a; Turner, 2006) and parenting practices (Kotchick, Dorsey, & Heller, 2005; Jones et al., 2006; Taraban et al., 2017). Among a community sample of low-income, African American single mothers, low levels of informal support accentuated the relationships among neighborhood stress, maternal psychological distress, and engagement in positive parenting practices such that informal support was particularly important among mothers facing environmental stressors (Kotchick et al., 2005). Likewise, among a WIC-eligible sample of mothers of young children, the role of informal support depended upon marital status. Informal support moderated the negative relationship between depression and positive parenting among single mothers only, not those cohabiting or married (Taraban et al., 2017).

However, others (Ajrouch et al., 2016b; Jackson et al., 1998; Kingston, 2013) found that informal support was least helpful under conditions of high stress and depression (Jackson et al., 1998), food insecurity (Ajrouch et al., 2016b) and neighborhood problems (Ajrouch et al., 2016b; Kingston, 2013). Ajrouch et al. (2010b) found that although informal support provided protection from everyday stress, it did little for mothers under acute stress including those with high food insecurity or high neighborhood problems. Similarly, Kingston (2013) found that informal support had stronger effects in high socioeconomic status neighborhoods than in low socioeconomic neighborhoods. Examining parenting behavior, Jackson et al. (1998) found that high levels of stress and depression exacerbated informal support’s positive relationship to spanking.

Studies that found level of disadvantage did not change informal support’s influence also examined a range of outcomes. Studies examined depression (Manual et al., 2012; Reid & Taylor, 2015), stress (Raikes & Thompson, 2005; Sampson, Villarreal, & Padilla, 2015), life satisfaction (Bellin et al., 2015), residential stability (Turney & Harknett, 2010), and parenting (Kimbro & Schachter, 2011). Inconsistent findings about level of disadvantage as a moderator of informal support’s influence on outcomes indicate the potential importance of considering aspects of support and need.

Discussion

The systematic review examined the role of informal support in the lives of low-income mothers in the post-welfare reform era. Included studies were almost universally of high quality (SCIE, 2010) and, typically, employed nationally-funded secondary datasets. To consider potential causation issues, 27 of the 55 studies examining informal support as a predictor utilized multiple waves of data and a majority of these studies (n = 20) employed specific data analytic techniques (e.g., fixed, random, or mixed effect modeling; controls for social support at earlier waves) to consider potential endogeneity. The review strongly suggests that informal support is the least available among low-income mothers who are in the most need, including those who are single, immigrants, in deep poverty, or in poor physical or mental health. The positive relationship between vulnerability and social support is particularly troubling in the context of a weak, post-welfare reform public safety net.