Abstract

Lead (Pb) is a well-known toxicant, especially for the developing nervous system, albeit the mechanism is largely unknown. In this study, we use time series RNA-seq to conduct a genome-wide survey of the transcriptome response of human embryonic stem cell-derived neural progenitor cells to lead treatment. Using a dynamic time warping algorithm coupled with statistical tests, we find that lead can either accelerate or decelerate the expression of specific genes during the time series. We further show that lead disrupts a neuron- and brain-specific splicing factor NOVA1 regulated splicing network. Using lead induced transcriptome change signatures, we predict several known and novel disease risks under lead exposure. The findings in this study will allow a better understanding of the mechanism of lead toxicity, facilitate the development of diagnostic biomarkers and treatment for lead exposure, and comprise a highly valuable resource for environmental toxicology. Our study also demonstrates that a human (embryonic stem) cell-derived system can be used for studying the mechanism of toxicants, which can be useful for drug or compound toxicity screens and safety assessment.

Keywords: lead (Pb) exposure, transcriptome response, time series, RNA-seq, dynamic time warping, disease risk prediction

Lead is well known as one of the most ubiquitous and persistent toxicants present in the environment. Excessive exposure to lead can cause several serious health problems such as liver damage (Degawa etal., 1995), visual dysfunction (Otto and Fox, 1992), hypertension (Zhang etal., 2012), cognitive function disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Nigg etal., 2010). However, lead is still widely used in industry and manufacturing due to its physical and chemical properties (Abadin etal., 2007). Lead can enter drinking water when service pipes that contain lead corrode, especially where the water has high acidity or low mineral content (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). For example, in 2015 the U.S. city of Flint, Michigan had a series of problems that culminated with lead contamination from aging pipes and caused thousands of residents to experience a range of serious health problems (Detroit Free Press [October 8, 2015]). Understanding the molecular mechanisms of how lead affects the human transcriptome is important for understanding how lead can cause human disease. Previous studies suggest lead exposure leads to several gene expression changes such as increased expression of beta-amyloid precursor protein (APP) and the APP cleaving enzyme beta-secretase 1 (Wu etal., 2008), altered expression of DNA methyltransferases and methyl cytosine-binding proteins (Schneider etal., 2013), decreased expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (Neal etal., 2011) as well as disrupted normal expression patterns for several neural markers (Sanchez-Martin etal., 2013). These findings shed light on a handful of direct or indirect molecular targets of lead, but the comprehensive temporal transcriptomic response to lead exposure remains largely unstudied.

When compared with other cell types, neural cells are the most sensitive and primary targets of lead (Cory-Slechta, 1996; Flora etal., 2012). For example, lead can disrupt neurotransmitter release at sites involved in calcium-regulated secretion (Suszkiw, 2004). Lead exposure is highly associated with cognitive defects in children (Lidsky and Schneider, 2003). Neural cells or their progenitors have enabled researchers to establish model systems for probing developmental neurotoxicity of lead in vitro (Senut etal., 2014). Thus we chose human neural progenitor cells (NPCs) for investigating the response of lead.

Here, we use time series RNA-seq to conduct a genome-wide survey of the temporal transcriptome response of human embryonic stem (ES) cell-derived NPCs exposed to lead. We identify genes that show different dynamic patterns over time as compared with untreated controls in response to lead treatment and characterize their temporal expression profiles. Using a dynamic time warping (DTW) algorithm (Giorgino, 2009) coupled with a one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test, we identify lead induced “gear-shift” genes defined by the exhibition of accelerated or decelerated expression changes across the time series compared with untreated controls.

NOVA1 is a neural-specific splicing factor (SF) and is vitally important for neural development through its regulation of hundreds of distinct alternative splicing events. Using exon splice junction read counts, we identify lead induced alternative splicing changes and further show that lead disrupts NOVA1 regulated splicing network.

Traditionally, the potential toxicity of environmental chemicals have been tested through animal models, which suffer from high cost and difficulties in extrapolating findings to humans. Moreover, the potential toxicity does not necessarily result in obvious phenotype changes but rather in minor changes relating to cell activities or communication. We hypothesize that, by using lead induced transcriptome change signatures, we can predict lead induced disease risk. By comparing the human disease associated gene database (DisGeNET) (Bauer-Mehren etal., 2010) with lead induced gene expression changes, we predict that lead will potentially increase the risk of several diseases such as cognitive impairment, cancer, developmental impairment, and hormonal-immune system disease. The majority of these predictions are directly or indirectly supported by epidemiological case-control studies. In addition, we linked lead exposure with several novel disease risks such as Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) using genes containing lead induced aberrantly spliced exons; though further studies are needed to confirm these associations.

Taken together, these results present a comprehensive temporal lead induced transcriptome response map; a highly valuable resource for understanding the mechanism of lead toxicity expediting the development of biomarkers of and treatments for lead exposure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Derivation of NPCs

NPCs were derived with a modified protocol from a previously reported protocol (Chambers etal., 2009). Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) were split using 0.5 mM EDTA in 1X PBS and cultured in E8 medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) minus TGF-β1 and supplemented with SB431542 (TGF-β receptor inhibitor, 10 μM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The medium was then switched to E6 medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with SB431542 (10 μM) 2 days after split for 7 days. Media was changed daily. The neural rosettes were then mechanically dissociated from the culture dish and cultured as floating aggregates in neural expansion medium (E6 medium without insulin or transferrin supplemented with N2, B27 and FGF2 [5 ng/ml]) for 4 days. Aggregates were then dissociated with Accutase (Life Technologies) and plated onto Matrigel coated plates in neural expansion medium. Cells were cultured for an additional 22 days, passaged when confluent. After culture, the cells were cryopreserved at 1.2 × 107 cells per vial.

Lead treatment

We used lead acetate to treat NPCs at 2 different concentrations, 3 and 30 μM. In children, encephalopathy has been associated with blood lead (PbB) levels (invivo) as low as 70 μg/dl (3.36 μM) (Abadin etal., 2007). Children are more sensitive to neurological issues associated with lead exposure. In this study, we chose 3 μM as the low concentration lead because the concentration of 3uM of lead acetate is close to the PbB levels invivo that can cause encephalopathy. Due to differences in biokinetics and bioavailability of chemicals invitro and invivo, in most cases the cytotoxic concentrations are much higher invitro (Gülden and Seibert, 2006). We reasoned that 3 μM might be too low to observe much of an effect in an invitro study and thus used 30 μM as the high concentration. A study investigating lead toxicity in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) invitro did not observe toxicity until the lead concentration was above 500 μM (de la Fuente etal., 2002). Although the cell type used in our study is different from theirs and our lead exposure time (26 days) is much longer than theirs (48 h), the high concentration of lead (30 μM) used in our study is far below their level. In fact, lead-30 μM or higher is the most widely used concentration for investigating the mechanism of lead toxicity invitro (Lee etal., 2009; Robinson etal., 2015; Zheng etal., 1999).

NPCs were thawed and expanded in neural expansion medium for 5 days before they were harvested by Accutase treatment. Roughly 1 × 105 cells were then seeded into one well of a 48-well plate in neural expansion medium. Lead treatment started on the same day (day 0). Media was changed every 2 days. Samples were collected at indicated time points by lysing cells directly on the plate with 350 µl RLT buffer. No apparent apoptosis was observed for the cells under lead-30 μM treatment. Cells were dividing throughout the 26 days as seen in the time-lapse movies. Time-lapse movies (from day 2 to 26) are available at (http://www.morgridge.net/upload/files/peng/Lead_Treatment/CellMovies.zip).

RNA sequencing and data processing

Cells were lysed in 350 µl of the Qiagen Buffer RLT (79216). Total RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNeasy 96 Kit (74181) and quantified with the ThermoFisher Scientific Quant-It RNA Assay Kit (Q33140) and the Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA 6000 Pico Kit (5067-1513). cDNA libraries were prepared with 100 ng of input total RNA and indexed with the Illumina TruSeq RNA Prep Kit v2 (RS-122-2001 and RS-122-2002). Indexed cDNA libraries were pooled and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2500 with single end 51 bp reads. FASTQ files were generated by CASAVA (v1.8.2). Reads were mapped to the human transcriptome (RefGene v1.1.17) using Bowtie 0.12.8 (Langmead etal., 2009) allowing up to 2-mismatches and a maximum of 200 multiple hits. The gene expected read counts and transcripts per millions (TPMs) were estimated by RSEM (v1.2.3) (Li and Dewey, 2011).

Support vector regression to model cell growth days

Support vector regression (SVR) is a machine learning algorithm to solve nonlinear regression problems. Given a training dataset where xi is an input vector (eg, features), yi is the observed value (eg, days), SVR mapped x into a higher-dimension feature space F via a nonlinear mapping , then alinear regression is performed in this space. Briefly, SVR approximate a function using the equation

The coefficients w and b are estimated by minimizing the function

where is the empirical error, which is measured by

and ½ and C are regularization term and constant value, respectively.

The estimation of w and b are obtained by the function

subject to

The optimization problem can be transformed into a quadratic programming problem via the introduction of Lagrange multipliers:

where K is the kernel function . The RBF (radial basis function) kernel is used in this study:

Root mean square errors (RMSEs) and Pearson correlation coefficient (R) were used to assess the prediction performance.

where n is the number of days. and are predicted and experimentally observed days, respectively.

To reduce the feature dimensions, we performed principal component analysis (PCA) on TPMs for all the samples and used principal components (PCs) as features to do SVR training and prediction (Li etal., 2008). The untreated controls were used as the training dataset. We applied a forward feature selection procedure to select the best PCs by adding one PC each time (starting from the first component, then the second component, and so on) to the model and then assessed the prediction performance via Leave-One-Out Cross Validation on the untreated controls. We chose the top 5 PCs as the final features as they showed the best RMSE and R. SVR is implemented in the R package (“e1071”) (Dimitriadou etal., 2011).

Differentially expressed genes

We used the EBSeq package (Leng etal., 2013) to assess the probability of a gene being differentially expressed between any 2 given conditions. We required that differentially expressed genes (DEGs) should have FDR < 5% via EBSeq and >1.5-fold change of median-by-ratio normalized read counts.

Gene ontology and pathway analysis

The gene ontology (GO) and pathway analysis were performed using DAVID (Huang da etal., 2009). We required p > .05 (Bonferroni adjusted) for significantly enriched GO terms (Biological Process Level 3) or pathways (KEGG) (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000).

Defining lead-30 μM induced gene expression change patterns

In this study, we investigated how treatment with lead-30 μM altered gene expression patterns over a time course of 26 daily samplings compared with untreated controls over the same time course. For each gene at each time point, we assigned 1 of 3 comparative expression classifications based on a differential expression analysis between the treated and untreated samples at the same day: Up (significantly upregulated in the treated sample versus the control), Down (significantly downregulated), or EE (equivalently expressed). Hence, each gene was assigned one of 326 possible classification vectors (3 = number of classifications, 26 = number of time points). We reduced the dimensional space by assigning to each gene an ordered pair defining its preponderant differential expression pattern over the time course: (Up-Up, Down-Down, EE-Up, EE-Down, Up-EE, Down-EE, Up-Down and Down-Up). As shown in Supplementary Figure 1, genes with ≥20 time points significantly all upregulated or all downregulated, were labeled Up-Up or Down-Down respectively. For any other gene with at least one Up or Down time point, we applied a bootstrapping test (1000 times) to gauge whether Up days or Down days were statistically enriched in time points either earlier or later than otherwise classified days.

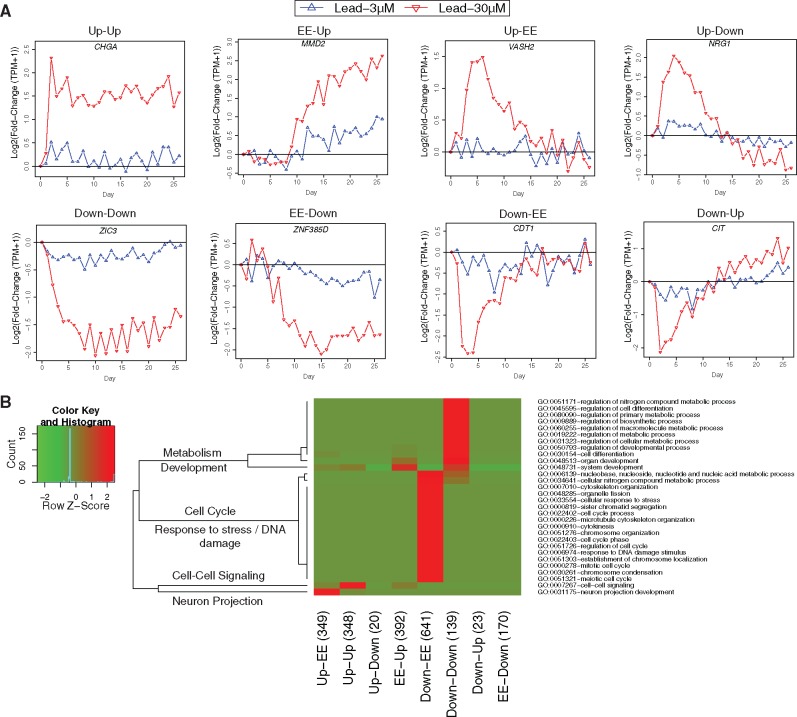

For example, given a gene with M Up time points, we would randomly select M distinct integers from 1 through 26. If the mean of our observed set is less than the mean of our random set, we increment an “earlier count”: E; if it is greater, we increment a “later count”: L. This process is repeated 1000 times. We then calculate the p-value for “earlier” enrichment of Up time points as E/1000; and similarly, the p-value for “later” enrichment of Up time points is L/1000. The same calculations are then performed for Down time points. Then, using a p-value of .01 as a threshold, each gene is assigned an Early-Late classification ordered pair. For genes combining EE days with only Up days or only Down days, we use the terms EE-Up and EE-Down to signify that Up (or Down) time points are enriched late with respect to the overall time course; similarly, Up-EE and Down-EE signify early enrichment. For genes with both Up and Down days, we use the terms Up-Down and Down-Up to signify a swing from one class of differential expression to the other. Examples of each category are shown in Figure 4A.

Figure 4.

Grouping lead-30 μM induced gene expression changes into 8 categories defined as Up-Up, Down-Down, EE-Up, EE-Down, Up-EE, Down-EE, Up-Down, and Down-Up. A, Examples of each category. The x-axis is the day point and the y-axis is the log2 transformed fold change (TPM +1) (lead treated NPCs and untreated control at the same day point). B, Enriched GO terms for each category. The GO terms showed in the figure are the union of all the significantly enriched terms (Bonferroni adjusted p-value < .001) in each category. The row scaling Z-Score is calculated based on log10 of Bonferroni adjusted p-value.

Detection of lead induced “gear-shift” genes

To detect lead-30 μM induced “gear-shift” genes, we firstly required that genes should be expressed and have sufficient variation in the untreated controls across the time series. Hence we filtered out genes from downstream analysis with average TPMs ≤1.35 (30% quantile) or coefficient of variation ≤ 0.19 (30% quantile) in the untreated controls across the time series. We further required that the gene expression patterns in lead-30 μM and untreated control should be highly rank correlated (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient [Rho] > 0.8) between the time series. For the genes which passed these criteria, a DTW algorithm is performed on them to measure the similarity between 2 temporal gene expression patterns. DTW was performed using the R package (“dtw”) (Giorgino, 2009). For the aligned days between lead-30 μM and untreated control NPCs, we calculated the statistical significance of lead-30 μM induced acceleration and deceleration via a 1-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test on aligned days respectively.

Using RNA-seq to detect alternative splicing changes

The exon splice junction read counts (upstream junction [UJC], downstream junction [DJC], and skipping junction [SJC]) were obtained by mapping RNA-seq reads to human genes (RefGene v1.1.17) via TopHat (Trapnell etal., 2009). We required that splice junction reads should have at least 8 bp on each side of the splice junction and uniquely mapped. These junction read coordinates in the transcripts were further transferred to genomic coordinates (hg19). The junction reads, which only contained unique genomic coordinates, were kept for downstream analysis. We calculated the exon inclusion level (Ψ) in any given sample using these uniquely mapped junction read counts as follows:

Given an exon, the probability of a significant splicing change (|ΔΨ| > 10%) between any 2 samples was calculated by these junction counts via a multivariate Bayesian based approach (Shen etal., 2012).

Real time qPCR validation for gene expression change

The qPCR was performed by the TaqMan Universal Master Mix II, no UNG (ThermoFisher Scientific, Madison, WI) on a Viia7 real time PCR machine (Life Technologies). GAPDH with a VIC-MGB_PL dye was multiplexed with the reactions as a loading control that was used to normalize gene expression levels.

Real time qPCR validation for splicing change

We randomly picked 7 exons with a large dynamic range of FDRs (0–0.22) to perform qPCR validation. For each cassette alternative splicing event, we designed 2 sets of primers. One primer set amplifies the constant region (constitutive exons are based on UCSC known gene annotation) and another one amplifies the isoform-specific region (target exon plus upstream or downstream exon). The relative quantity of each region in the cDNA was measured by quantitative real-time PCR with the Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Life Technologies) on a Viia7 real time PCR machine (Life Technologies). For each exon, ΔCT is calculated by the CTdifferences of the isoform specific product and constant product (CT,Isoform – CT,Constant), CT denoting the threshold cycle. We used the following formulae to calculate the fold change:

Data access

The RNA-seq raw data (fastq files) and the processed data (TPMs and expected counts) have been submitted to GEO with accession number GSE84712.

RESULTS

Transcriptional Profile of NPCs Exposed to Lead

NPCs were derived from hESCs with a modified protocol from a previously reported protocol (Chambers etal., 2009) (Methods). We used lead acetate to treat NPCs at 2 different concentrations, 3 and 30 μM (see “Materials and Methods” section). Cells were harvested prior to treatment (day 0) and daily, from day 1 to 26, after lead exposure. For each time and lead concentration, RNA was extracted from each sample and sequenced at an average depth of 17 million single end 51 bp reads (see “Materials and Methods” section). A separate reference sample consisting of untreated NPCs at each time was also prepared and sequenced. The gene expression values were estimated via RSEM producing measures of TPM (Li and Dewey, 2011).

To assess the temporal cellular response to lead treatment, we performed a PCA. As shown in Figure 1A (PC1 vs PC2) and Figure 1B (PC2 vs PC3), the overall gene expression patterns are dominated by 2 factors: time and lead concentration. The transcriptome of the control NPCs changed over time in our culture conditions. Since time and lead concentration dominate global gene expression patterns (Figure 1), we hypothesized that one of the potential effects of lead is to accelerate or decelerate the pace of differentiation of NPCs. If so, then we can use a machine learning model to predict the “transcriptomic day” for each sample, and use the deviation between the predicted and the observed days to quantify the extent of cellular response to different concentrations of lead treatment. To this end, we developed a machine learning regression model, SVR (Smola and Vapnik, 1997), to model the dependent variable (day) as the function of the top 5 PCA components of gene expression profiles (TPMs) (see “Materials and Methods” section). The agreement of prediction and observation was evaluated by comparing the predicted days versus the observed days through RMSE and Pearson correlation coefficient (R). As shown in Figure 2A, if both the training and the prediction were performed on untreated NPCs, the agreement between observation and prediction is very high as expected (RMSE = 1.04, R = 0.99). Then we applied this model (trained by untreated control) to predict the expected days of lead-3 μM treated NPCs. As shown in Figure 2B, the agreement is still very high (RMSE = 1.74, R = 0.98), suggesting that the impact of the low concentration lead (3 μM) treatment on the pace of differentiation is minimal. We next applied the same model (trained by untreated control) to predict the expected days of lead-30 μM treated NPCs. As shown in Figure 2C, the discrepancy between the predicted days and the observed days increases dramatically (RMSE = 4.79, R = 0.87), indicating that lead-30 μM substantially distorted the normal NPC temporal gene expression patterns.

Figure 1.

PCA of NPCs gene expression data (measured in TPMs). Each dot represents a sample. Black dots represent control cells, blue dots represent cells exposed to 3 μM of lead, and red represents cells exposed to 30 μM of lead. The dot size is proportional to time points (0–26 days). A, PC1 versus PC2. (B) PC2 versus PC3.

Figure 2.

Modeling cellular days by SVR. The untreated NPCs are used as training datasets. The model predicts the expected cellular days in control (A), lead-3 μM (B) and lead-30 μM (C) treated NPCs. The prediction performance is evaluated by comparing the observed day versus predicted day via RMSE and Pearson correlation coefficients (R).

To further analyze what genes are perturbed during lead treatment, we identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between lead treated NPCs and untreated controls at each time point (see “Materials and Methods” section). For each day point, approximately 1000–1200 genes are upregulated and approximately 600–1200 genes are downregulated in lead-30 μM treated NPCs (Figure 3). Among the DEGs, we picked 5 genes (3 upregulated and 2 downregulated by lead-30 μM) from day 24 to perform qPCR validation, as they covered a large dynamic range of log2 transformed fold changes “log2 ((TPMlead-30μM +1)/(TPM control+1))” which were estimated by RNA-seq (Supplementary Figure 2). As shown in Suplementary Figure 2, the gene expression levels estimated by qPCR are highly rank correlated with these estimated by RNA-seq (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient Rho = 1), suggesting RNA-seq can accurately estimate the gene expression levels.

Figure 3.

The number of DEGs between lead treated NPCs and controls at each day point.

In contrast, a very limited number of genes (approximately 200 or less) are either up or down regulated at each time point in low dose (lead-3 μM) treated NPCs (Figure 3). This suggests that lead-30 μM elicits a greater extent of transcriptional changes and triggers a more complicated NPC transcriptome response.

Different Lead Induced Gene Expression Change Patterns Are Associated With Distinct Functions

In this study, we investigated how lead-30 μM altered gene expression patterns over a time course of 26 days compared with untreated controls over the same time course. For each gene at each time point, we assigned 1 of 3 comparative expression classifications based on a differential expression analysis between the treated and untreated samples at the same day: Up (significantly upregulated in the treated sample vs the control), Down (significantly downregulated), or EE (equivalently expressed). Hence, each gene was assigned one of 326 possible classification vectors (3 = number of classifications, 26 = number of time points). We reduced the dimensional space by assigning to each gene an ordered pair defining its preponderant differential expression pattern over the time course: (Up-Up, Down-Down, EE-Up, EE-Down, Up-EE, Down-EE, Up-Down, and Down-Up). As shown in Supplementary Figure 1, genes with ≥20 time points significantly all upregulated or all downregulated were labeled Up-Up or Down-Down, respectively. For any other gene with at least one Up or Down time point, we applied a bootstrapping test (1000 times) to gauge whether Up days or Down days were statistically enriched in time points either earlier or later than otherwise classified days. A detailed definition of each category can be found in “Materials and Methods” section. Examples of each category are shown in Figure 4A.

To examine the functional relevance associated with each category, we calculated significantly enriched GO terms (p < .05, Bonferroni adjusted, Biological Process Level 3, green in Supplementary Table 1) based on the DAVID database (Huang da etal., 2009). To further visualize the top enriched GO terms in each category, we used a more stringent p-value cutoff (p < .001, Bonferroni adjusted, red in Supplementary Table S1) and made a union of all enriched GO terms as shown in Figure 4B. Interestingly, different differential expression categories are enriched in distinct GO terms (Supplementary Table 1). The genes, which are upregulated for both early and late time points (Up-Up), are strongly enriched in cell-cell signaling functions indicating a long lasting response of cells to the microenvironment change. By contrast, the upregulated genes, which are only enriched in late time points (EE-Up), are strongly enriched in development terms. The genes with Down-Down patterns are associated with metabolism and development terms indicating that lead represses or perturbs normal metabolic and development processes. The downregulated genes, which are only enriched in early time points (Down-EE), are associated with broad functions including cell cycle and response to stress and DNA damage. Hence, each lead-30 μM induced gene expression change pattern has a distinct functional relevance.

Lead Induced “Gear-Shift” Genes

The SVR prediction model suggests that one of the effects of high concentration lead (30 μM) is that it significantly distorts or disrupts the normal NPC cellular temporal transcriptome dynamical path (Figure 2C). We hypothesize that in addition to lead-30 μM induced complicated perturbations on temporal gene expressions, lead-30 μM could also alter a fraction of genes via either accelerating or decelerating their expression changes across the time series (lead induced “gear-shift” genes). For example, a gene in untreated NPCs could change dramatically in the first 10 days and then be steadily expressed. But exposed to 30 μM of lead, the same gene could require <10 days (accelerated) or >10 days (decelerated) to complete this dynamic change. We used a DTW algorithm (Giorgino, 2009) coupled with a 1-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test to detect lead-30 μM induced significantly accelerated or decelerated genes (see “Materials and Methods” section). A total of 1041 and 478 genes are significantly accelerated and decelerated in lead-30 μM treated NPCs (p < .05, Bonferroni adjusted), when compared with untreated control samples (Supplementary Table 2). Figure 5A is an example of lead-30 μM induced accelerated gene (BAZ1A) and Figure 5B is the corresponding aligned days via DTW. For example, the expression level for gene BAZ1A in theuntreated controls begins decreasing substantially at day5reaching approximately 10 TPM by day 12. However, in lead-30 μM treated NPCs, the expression level for BAZ1A begins decreasing substantially at day 3 and reaches 10 TPM by day 6 (Figure 5A). Figure 5C is an example of a lead-30 μM induced decelerated gene (C4B) and Figure 5D is the corresponding aligned days via DTW. The C4B gene does not show a difference for the first 10 days between lead-30 μM treated NPCs and control. But after day 10, the same dynamic change in gene C4B takes more time in the lead-30 μM treated NPCs than in the untreated controls.

Figure 5.

Examples of lead-30 μM induced “gear-shift” genes. A, BAZ1A is a lead-30 μM induced accelerated gene. B, DTW of BAZ1A. C, C4B is a lead-30 μM induced decelerated gene. D, DTW of C4B.

The lead-30 μM induced accelerated genes are significantly enriched in cell cycle, neurotransmitter transport, and organelle fission GO terms while the decelerated genes are enriched in positive regulation of biological, metabolic and immune system processes (p < .05, Bonferroni adjusted, Biological Process Level 3) (Supplementary Table 2). We further performed pathway analysis on lead-30 μM induced “gear-shift” genes (see “Materials and Methods” section). Interestingly, the lead-30 μM induced accelerated genes are significantly enriched in ribosome pathway (hsa03010:Ribosome, P = 1.77E-13, Bonferroni adjusted) (Supplementary Table 3). There is no significantly enriched pathway for lead-30 μM induced decelerated genes with p < .05 (Bonferroni adjusted) (Supplementary Table 3).

Lead Induced Alternative Splicing Changes

Alternative splicing is a crucial mechanism for expanding transcriptomic and proteomic diversity. The coordinated changes in splicing contribute an additional layer of gene regulation at the posttranscriptional level, and aberrant splicing can cause a wide range of human diseases (Chen and Manley, 2009). To examine whether lead will also induce global alternative splicing perturbations, we identified changes in splicing between lead-30 μM treated NPCs and untreated controls in the time series. Briefly, for each cassette exon in any given sample, we estimated its exon inclusion level (Ψ) by using reads uniquely mapped to its UJC, DJC, and SJC. The probability of a significant splicing change (|ΔΨ| > 10%) between lead-30 μM and control in the same day is inferred by these junction counts via a Bayesian based model (Shen etal., 2012). The illustration of this procedure and an example are shown in Figures 6A–C. We thereby identified 374 cassette exons predicted to undergo significant splicing changes in lead-30 μM versus control in any of the day-by-day comparisons (FDR < 0.25) (Supplementary Table 4). To further confirm these lead-30 μM induced splicing changes, we randomly picked 7 exons with a large dynamic range of FDRs (0–0.22) to perform qPCR validation (Supplementary Table S4) (see “Materials and Methods” section). Of the 7 exons, the minimal qPCR fold change in the predicted direction is 1.5, suggesting that many of the 374 predicted cassette exons are likely to have significant splicing changes between lead-30 μM and control. Furthermore, the ΔΨ predicted by RNA-seq and the fold changes estimated by qPCR are highly correlated (Rho = 0.71, Spearman’s rank correlation) (Figure 6D). The genes containing lead-30 μM induced aberrantly spliced exons are significantly enriched in the GO term “cytoskeleton organization” (p = .02, Bonferroni adjusted, Biological Process Level 3).

Figure 6.

Lead-30 μM induced cassette exon alternative splicing change. A, Illustration of RNA-seq detection of lead-30 μM induced splicing change. The exon inclusion level (Ψ) in a gene is estimated by the UJC read counts, the DJC read counts, and SJC read counts. The probability of a significant splicing change (|ΔΨ| > 10%) between lead-30 μM and control in the same day is inferred by exon inclusion junction counts, and SJC in these 2 conditions. B, UCSC genome browser view of a lead-30 μM induced splicing change example (UBE2V1). The target exon is highlighted by rectangle. C, Real time qPCR validation of the splicing change (UBE2V1). D, The RNA-seq estimated exon inclusion level change (ΔΨ) between lead-30 μM and control is positively correlated with qPCR validations with Spearman rank correlation (Rho = 0.71). E, The neuronal specific SF (NOVA1) is up regulated in lead-30 μM if compared with controls. F, The lead-30 μM induced splicing change exons are significantly enriched in NOVA1 regulated exons.

Exon usage and splice site recognition are tightly regulated by a large number of SFs and auxiliary RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) in a very complicated manner (Chen and Manley, 2009). For example, a SF can enhance, repress or have no impact on an exon splicing, depending on the context, such as binding positions or the existence of other auxiliary RBPs (Saltzman etal., 2011; Wang and Burge, 2008; Witten and Ule, 2011). Meanwhile, an exon can be regulated by several of these context dependent SFs at the same time. Hence, it is a challenge to pinpoint the exact mechanism of these lead induced aberrantly spliced exons. Despite this, we sought to examine any splicing master regulators (eg, SFs), in which they are substantially differentially expressed under lead exposure and could possibly contribute to these aberrant splicing events. To this end, we collected 60 RBP genes, which have prior evidence for regulation of alternative splicing (Chen and Manley, 2009; De la Grange etal., 2010), and then compared their expression levels in lead-30 μM treated NPCs with controls. For each RBP gene, we calculated the total DEG day points in the time series (FDR < 5% via EBSeq and > 1.5 fold-change, median-by-ratio normalized read counts). If we rank them based on total DEG days, the top 3 RBP genes are ELAVL2 (24 days), CELF4 (24 days), and NOVA1 (23 days). ELAVL2 and CELF4 belong to the ELAV-like RBP family, in which the binding is involved in broad functions such as regulation of mRNA splicing, RNA editing, RNA stability and RNA translation. Interestingly, NOVA1 is a well-known neuron and brain-specific SF vitally important for neuronal development via regulating hundreds of alternative splicing events (Irimia etal., 2011; Jensen etal., 2000). As shown in Figure 6E, NOVA1 is significantly upregulated in lead-30 μM if compared with the control in our time series. To test the potential link between the lead induced NOVA1 gene expression alteration and the lead induced splicing changes, we investigated whether the aberrantly spliced exons were significantly enriched in NOVA1 targets. We collected 326 high confidence mouse NOVA1 regulated exons from prior work that were determined by mapping NOVA1 protein binding footprints via UV-crosslinking and immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing (HITS-CLIP) (Zhang and Darnell, 2011). After transfer to human (hg19) coordinates via liftOver (Kent etal., 2002), we identified 315 NOVA1 regulated exons in human genes. Interestingly, among our identified 374 lead-30 μM induced aberrant splicing exons, 25 of them (6.68%) overlapped with the NOVA1 regulated exon list. We also generated a list of background cassette exons, which do not show a significant lead-30 μM response (see “Materials and Methods” section). Among 23 399 background exons, only 138 of them (0.59%) overlapped with NOVA1 targets. These results suggest that lead-30 μM induced aberrant splicing exons are significantly enriched in NOVA1 targets (p < 2.2e-16, Fisher's Exact Test; Figure 6F).

Transcriptome Change Signatures Predict Disease Risk

We hypothesize that the lead-30 μM induced transcriptome changes can be used to predict lead exposure associated disease risk. To investigate this, we collected the human disease-associated genes from DisGeNET (v2.1) (Bauer-Mehren etal., 2010). Only high confidence gene-disease associations (“Curated-v2.1”: UniProt and Comparative Toxicogenomics Database) were used, and associations based on “text mining MEDLINE” were excluded. To ensure each disease type has sufficient genes, we further removed disease types with <50 disease-associated genes, and thus we only focused on 84 disease types.

For lead-30 μM induced gene expression changes, we focused on the 487 genes, which were either significantly upregulated or downregulated for a long period of time (≥20-day points) in lead-30 μM treated NPCs, when compared with untreated control samples. We also generated a set of background genes with no significant changes between lead-30 μM and control at all day points but have at least a minimal gene expression level (Ave. TPM > 1 in control samples across time points). For each disease type, we calculated whether the lead-30 μM most affected genes are significantly enriched in disease-associated genes by a one-sided Fisher’s exact test. As shown in Figure 7A, the lead-30 μM affected genes are significantly enriched in eleven disease types (p < .01) which can be grouped into 4 categories: cognitive impairment (autism, schizophrenia, seizures, substance-related disorders, amphetamine-related disorders), cancer (prostatic neoplasms, colorectal neoplasms, melanoma, carcinoma hepatocellular), developmental impairment (craniofacial abnormalities), and hormonal-immune system disease (endometriosis).

Figure 7.

Lead-30 μM induced transcriptional and post-transcriptional changes enriched in disease-associated genes. A, Lead-30 μM induced gene expression changes enriched in disease genes. B, Lead-30 μM induced alternative splicing changes enriched in disease genes.

In addition to gene expression changes, we also detected 374 cassette exons (Supplementary Table 4) which undergo lead-30 μM induced splicing changes. Although direct epidemiological evidence of disease associated alternatively spliced exons is very limited, we investigated whether the genes containing these lead induced splicing change exons are more likely enriched in specific disease types. Similar to disease gene enrichment analysis, we also generated a background gene list with the additional requirement of no splicing changes between lead-30 μM treated NPCs and controls (Methods). As shown in Figure 7B, the lead-30 μM induced splicing change genes are enriched in 6 disease types (p < .01): autism, schizophrenia, status epilepticus, nerve degeneration, carcinoma adenoid cystic, and PCOS. Strikingly, autism and schizophrenia diseases appear in both transcriptional (gene expression) and posttranscriptional (alternative splicing) predictions.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we hypothesized that lead induced transcriptome change signatures for cells in vitro can be used to predict lead exposure associated disease risk. By comparison of lead induced gene expression changes with the human disease gene database DisGeNET (v2.1) (Bauer-Mehren etal., 2010), we find strong associations between lead exposure and several disease types which can be grouped into 4 categories: cognitive impairment, cancer, developmental impairment, and hormonal-immune system disease. Overall, our predictions are consistent with previous epidemiological findings. For example, numerous studies show that excessive exposure to lead is associated with risk of cognitive deficits (eg, autism; Landrigan, 2010; Lidsky and Schneider, 2005; schizophrenia; Opler etal., 2004), and developmental impairment; Saleh etal., 2009). Epidemiological studies also make a connection between lead exposure and the risk of several types of cancers (Fu and Boffetta, 1995) such as prostate cancer (Siddiqui etal., 2002). Interestingly, lead-30 μM affected genes are also enriched in endometriosis disease. Although there is no direct epidemiological evidence to demonstrate this association, a study suggests a potential link between heavy metal (cadmium) exposure and endometriosis (Jackson etal., 2008).

In our study, the disease risk prediction is based on 487 genes which were either significantly upregulated or downregulated for a long period of time (≥20-day points) in lead-30 μM treated NPCs, when compared with untreated control samples. We further investigated whether we can use low concentration lead (3 μM) induced transcriptome change signatures to predict disease risk. Due to a very limited number of genes being either up or down regulated at each time point in low dose (lead-3 μM) treated NPCs (Figure 3), if we apply the same criteria as lead-30 μM (≥20 day points, upregulated or downregulated) to select genes to fit disease models, only 6 genes can be selected. Therefore, we relaxed the criteria for lead-3 μM by selecting genes with ≥5-day points that are either upregulated or downregulated when compared with untreated control samples. Using the relaxed criteria, we selected 209 genes to perform disease gene enrichment analysis. As shown in Supplementary Figure 3, autism is the only predicted disease at the p < .001 significance level in lead-3 μM. Autism is also the top predicted disease in lead-30 μM with a more significant p-value, but lead-30 μM predicts more diseases (eg, several cancer types) at the p< .001 significance level (Figure 7A). Several cancer types are enriched in low concentration lead (3 μM) at the p < .01 significance level. These results suggest that the overall disease risk predictions between lead-3 and -30 μM are similar, but lead-30 μM increases the statistical significance indicating higher disease risk prediction sensitivity. In addition, the disease enrichment results are in alignment with epidemiological studies.

We also found genes containing lead induced aberrantly spliced exons are enriched in 6 disease types (p < .01): autism, schizophrenia, status epilepticus, nerve degeneration, carcinoma adenoid cystic and PCOS. Autism and schizophrenia diseases are significantly enriched in both lead induced transcriptional changes (gene expression changes) and posttranscriptional changes (alternative splicing) suggesting strong links with lead exposure. Interestingly, the genes containing lead induced aberrantly spliced exons are enriched in PCOS, which is the most common cause of female infertility. Although studies show obesity (Gambineri etal., 2002) and several genetic factors (Shi etal., 2012) might increase the risk of PCOS the exact cause of PCOS is still largely unknown. However, studies suggest that PCOS is tightly related to abnormal alternative spliced transcripts (Brazert etal., 2014; McAllister etal., 2014). Our study indicates a potential novel risk factor for PCOS: lead exposure. Nevertheless, this association needs to be further investigated.

Lead is widely used in industry and has a significant impact on human health. Although the exposure of lead has been linked with several diseases, the molecular mechanism of lead toxicity is largely unknown. Using a DTW algorithm (Giorgino, 2009) coupled with a one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test, we detected 1041 and 478 lead-30 μM induced accelerated and decelerated genes respectively. These genes altered the speed of normal NPC transcriptome dynamic change over time. Perturbation of gene expression can potentially remodel the pathways and further result in disease risks (Cohen etal., 2007). Interestingly, the lead-30 μM induced accelerated genes are significantly enriched in ribosome pathway (hsa03010: Ribosome, P = 1.77E-13, Bonferroni adjusted) (Supplementary Table 3). Although it is well known that ribosomal proteins (RPs) are essential for protein synthesis, RPs can also play an important role in extraribosomal functions that are independent of protein biosynthesis including but not limited to DNA replication, transcription, cell growth and proliferation, cancer, aging, and regulation of development (Bhavsar etal., 2010; Mao-De and Jing, 2007; Zhou etal., 2015). In addition, RPs can play a role as caretakers in response to cellular stress and genomic instability (Kim etal., 2014). Ribosomal biogenesis is also associated with tumor surveillance and cancer development (Liu etal., 2016).

In addition to lead induced gene expression changes, we also detected 374 lead induced alternative splicing changes by using RNA-seq reads mapped to exon-exon splice junctions. The advantage of using exon-exon splice junction read counts (exon upstream, downstream, and skipping junction read counts) to infer the probability of splicing change in 2 conditions is that it minimizes the chance that the splicing change detected is due to a gene expression change. Thus, using exon-exon splice junction read counts can significantly increase the specificity. However, this approach requires that the exon-exon splice junction region needs to have sufficient read counts to get a significant p-value. Therefore, it requires very deep sequencing read depth and that genes in both conditions be highly expressed. These limitations decrease the sensitivity of this approach. In this study, we sequenced approximately 17million reads per sample, which is far below a study using a similar approach to detect splicing changes (>50–100 M reads per sample) (Dittmar etal., 2012). Thus, the number of lead-30 μM induced splicing changes is likely underestimated in our study. Even with the relatively shallow sequencing, we still discover 374 alternative splicing events. Alternative splicing is a mechanism for generating a variety of protein products from one gene. Aberrant splicing is associated with many human diseases (Dredge etal., 2001). The lead induced aberrantly spliced exons found in this study add an important post-transcriptional layer to the changes in gene expression that underline how lead impacts the human transcriptome. GO analysis shows that the genes containing lead-30 μM induced aberrantly spliced exons are significantly enriched in the GO term “cytoskeleton organization” (p = .02, Bonferroni adjusted), suggesting that lead could potentially impact cellular assembly, arrangement of constituent parts, or disassembly of cytoskeletal structures via disrupting normal alternative splicing at posttranscriptional level.

Interestingly, these aberrantly spliced exons are significantly enriched in NOVA1 targets (p < 2.2e-16, one-sided Fisher’s Exact Test; Figure 6F). NOVA1 is a neural-specific (or enriched) SF, and its expression is restricted to (or enriched in) specific regions of the central nervous system, primarily the hindbrain and ventral spinal cord (Dredge etal., 2001). The ectopic NOVA1 expression is associated with paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus ataxia disease which is a neurological disorder characterized by deficits in inhibitory motor control in the eyes, limbs, and trunk (Darnell and Posner, 2003; Dredge etal., 2005). Lead induced upregulation of NOVA1 expression as well as the enrichment of NOVA1 targets in aberrantly spliced exons highlight a neural disease risk under lead exposure via potential disruption of the NOVA1 regulated splicing network.

A study treated human PBMCs with different concentrations of lead acetate (from 0.08 to 50 μM) to investigate how lead affects cytokine expression (Gillis etal., 2012). They identified 22 genes that were persistently elevated by lead. 10 and 11 out of these 22 genes can also be detected in our lead-3 and -30 μM treated NPCs, respectively, by requiring that at least one day point exhibits upregulation and no day points exhibit downregulation. Interestingly, in their study, the metallothionein genes had the highest fold changes in response to lead. The genes in the MT gene family have the capacity to protect against metal toxicity by binding heavy metals via their cysteine residues (Karin and Richards, 1984). If we sorted our low concentration lead (3 μM) induced gene expression changes by the total number of day points that are upregulated, all of the top 3 genes (MT1X, MT2A, and MT1E) belong to the MT gene family. In fact, the genes (MT1X, MT2A, and MT1E) are up regulated at almost all time points (24- to 26-day points) in both the lead-3 and -30 μM treated NPCs.

A study exposed rats to lead acetate from birth to weaning to examine lead induced gene expression changes of 3 neuronotypic and gliotypic markers: growth-associated protein (GAP-43), myelin basic protein (MBP), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in the cerebellum on postnatal days (PND) 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, and 50 (Zawia and Harry, 1996). On PND 9, they observed a significant stimulation of GAP-43 expression in rat samples with lead exposure if compared with untreated controls. In our invitro experiment, lead-30 μM significantly upregulated GAP-43 in 9-day points (days 3, 4, 5, 6, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22) if compared with untreated controls, and none of the day points showed significant downregulation of GAP-43 in lead-30 μM samples. Their invivo study also observed an early upregulation of MBP gene expression, but the expression levels for both MBP and GFAP were decreased between PND 20 and 50, in lead-exposed rats (Zawia and Harry, 1996). In our invitro experiment, lead-30 μM significantly upregulated the MBP gene in day point 1 and downregulated GFAP gene in 16-day points (days 5–15, 17–19, 21, and 25), which is in agreement with the rat data. No other day points showed significant differential expression for MBP or GFAP genes. For our low concentration lead (3 μM), none of these 3 genes (GAP-43, MBP, and GFAP) were found to be significantly differentially expressed at any of the day points.

Another study used Affymetrix microarrays to systemically investigate the effects of different levels of lead exposure (250 and 750 ppm lead acetate) by feeding Pb-containing food (RMH 1000 chow with or without added Pb acetate) during perinatal (gestation/lactation) and postnatal (through PND 45) periods on the hippocampal transcriptome in male and female rats (Schneider etal., 2012). They identified 395 genes in response to lead exposure either in male or in female rats. To compare them with our invitro experiment, we matched these rat gene symbols to our human gene symbols, and also removed genes with inconsistent changes in their samples (eg, upregulated in one sample but downregulated in another sample). This resulted in a set of 284 genes in response to lead exposure invivo. A comparison of these 284 genes invivo and our invitro response to lead is shown in Supplementary Figure 4A. For these 284 genes, if we require that at least one day point in our invitro experiment show the same change direction with invivo but no opposite change directions at any day point (eg, upregulated in any of the 26-day points but no downregulated day point), then we observe 13 and 56 consistently changed genes between their invivo samples and our invitro samples for lead-3 μM and lead-30 μM, respectively (as shown in Supplementary Figs. 4B and C). Due to differences in biokinetics and bioavailability of chemicals invitro and invivo and to variations between experimental conditions (eg, different species and cell types), the modest percentage of overlap between genes response to lead exposure invivo and invitro is expected. In fact, even carefully controlling other factors, the outcomes of lead exposure invivo are different in males and females (Schneider etal., 2012). Nevertheless, the lead induced consistently changed genes (Supplementary Figs. 4B and C) suggest that certain genes are robustly responding to lead exposure regardless of different conditions, such as different species, cell types, or whether the experiments are performed invivo or invitro.

There are another 2 studies that have shown that lead can also reprogram genes during the aging process by comparing aging mice with early life exposure to lead versus infant controls (Alashwal etal., 2012; Dosunmu etal., 2012). The results indicate that early life exposure to lead not only affects development, it may also affect the normal aging process in later life.

Although the invitro model is cost effective, its culture condition is simple and artificial compared with the complex invivo environment, in which the regulatory environment might be quite different. For complex tissues, such as the brain, such factors could even vary region by region. Furthermore, an invitro model cannot model other factors, such as sex bias, in response to lead exposure. In fact, a previous study has shown that the outcomes from lead exposures are different in males and females (Schneider etal., 2012). Our disease risk prediction based on our invitro model does not take into consideration sex-specific effects and unique sex-specific risk factors. In addition, due to differences in biokinetics and bioavailability of chemicals invitro and invivo (Gülden and Seibert, 2006), it is very hard to draw a conclusion about how the concentration range of lead exposure in humans compares to lead concentrations used in an invitro experiment. In fact, the cause of any disease is very complicated, and it is the outcome of aggregation of different risk factors. Our disease gene enrichment analysis only gives qualitative but not quantitative disease risk predictions. For example, based on our prediction, lead exposure could significantly increase the risk of several diseases (eg, autism, cancer). Our disease gene enrichment analysis provides correlations between lead induced transcriptome changes and disease associated genes. In vivo studies face similar challenges in predicting disease risk owing to differences in species’ responses to lead. Our invitro studies are meant to complement other invitro studies, invivo studies, and epidemiological studies.

The lead induced transcriptome changes, splicing alterations, and the predicted disease risk associations in this study give insight on the molecular mechanisms of lead toxicity, and can lead to a better understanding and potentially treatment of lead associated diseases. However, we acknowledge that our analysis is limited to the transcriptome level. Profiling lead induced other types of changes, such as proteomics, epigenetic and microRNA changes would aid in understanding of the effects of lead toxicity.

Our study also suggests that a human (ES) cell-derived system can be useful for drug or compound toxicity screens and safety assessment.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Toxicological Sciences online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Erin Syth for editorial assistance, as well as Jessica Antosiewicz-Bourget, Danny Mamott, Angela Elwell and Bao Kim Nguyen for technical assistance.

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5U01HL099773-02 to J.A.T.) and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UH3TR000506 to J.A.T.).

REFERENCES

- Abadin H., Ashizawa A., Stevens Y.-W., Llados F., Diamond G., Sage G., Citra M., Quinones A., Bosch S. J., Swarts S. G. (2007). Toxicological profile for lead. Atlanta (GA): Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. URL: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp13.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alashwal H., Dosunmu R., Zawia N. H. (2012). Integration of genome-wide expression and methylation data: Relevance to aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotoxicology 33, 1450–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer-Mehren A., Rautschka M., Sanz F., Furlong L. I. (2010). DisGeNET: A Cytoscape plugin to visualize, integrate, search and analyze gene–disease networks. Bioinformatics 26, 2924–2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar R. B., Makley L. N., Tsonis P. A. (2010). The other lives of ribosomal proteins. Hum. Genomics 4, 1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazert M., Antoni D., Gozdzicka-Józefiak A., Leszek P. (2014). Expression of insulin-like growth factor i isoforms in women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 102, e263–e264. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers S. M., Fasano C. A., Papapetrou E. P., Tomishima M., Sadelain M., Studer L. (2009). Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 275–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Manley J. L. (2009). Mechanisms of alternative splicing regulation: Insights from molecular and genomics approaches. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 741–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., Van Marter L. J., Sun Y., Allred E., Leviton A., Kohane I. S. (2007). Perturbation of gene expression of the chromatin remodeling pathway in premature newborns at risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Genome Biol. 8, R210.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory-Slechta D. A. (1996). Legacy of lead exposure: Consequences for the central nervous system. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 114, 224–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell R. B., Posner J. B. (2003). Paraneoplastic syndromes involving the nervous system. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 1543–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente H., Portales-Perez D., Baranda L., Diaz-Barriga F., Saavedra-Alanis V., Layseca E., Gonzalez A.R. (2002). Effect of arsenic, cadmium and lead on the induction of apoptosis of normal human mononuclear cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 129, 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Grange P., Gratadou L., Delord M., Dutertre M., Auboeuf D. (2010). Splicing factor and exon profiling across human tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 2825–2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degawa M., Arai H., Kubota M., Hashimoto Y. (1995). Ionic lead, but not other ionic metals (Ni2+, Co2+ and Cd2+), suppresses 2-methoxy-4-aminoazobenzene-mediated cytochrome P450IA2 (CYP1A2) induction in rat liver. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 18, 1215–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadou E., Hornik K., Leisch F., Meyer D., Weingessel A. (2011). e1071: Misc Functions of the Department of Statistics (e1071), TU Wien. R package version 1.5-27. In (doi).

- Dittmar K. A., Jiang P., Park J. W., Amirikian K., Wan J., Shen S., Xing Y., Carstens R. P. (2012). Genome-wide determination of a broad ESRP-regulated posttranscriptional network by high-throughput sequencing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 1468–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosunmu R., Alashwal H., Zawia N. H. (2012). Genome-wide expression and methylation profiling in the aged rodent brain due to early-life Pb exposure and its relevance to aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 133, 435–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dredge B. K., Polydorides A. D., Darnell R. B. (2001). The splice of life: Alternative splicing and neurological disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dredge B. K., Stefani G., Engelhard C. C., Darnell R. B. (2005). Nova autoregulation reveals dual functions in neuronal splicing. EMBO J. 24, 1608–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora G., Gupta D., Tiwari A. (2012). Toxicity of lead: A review with recent updates. Interdisciplinary toxicol 52, 47–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H., Boffetta P. (1995). Cancer and occupational exposure to inorganic lead compounds: A meta-analysis of published data. Occup. Environ. Med. 52, 73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambineri A., Pelusi C., Vicennati V., Pagotto U., Pasquali R. (2002). Obesity and the polycystic ovary syndrome. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 26, 883–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis B. S., Arbieva Z., Gavin I. M. (2012). Analysis of lead toxicity in human cells. BMC Genomics 13, 344.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgino T. (2009). Computing and visualizing dynamic time warping alignments in R: The dtw package. J. Stat. Softw. 31, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gülden M., Seibert H. (2006). In vitro–invivo extrapolation of toxic potencies for hazard and risk assessment—Problems and new developments. Altex 23, e225. [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W., Sherman B. T., Lempicki R. A. (2009). Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irimia M., Denuc A., Burguera D., Somorjai I., Martin-Duran J. M., Genikhovich G., Jimenez-Delgado S., Technau U., Roy S. W., Marfany G., et al. (2011). Stepwise assembly of the Nova-regulated alternative splicing network in the vertebrate brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 5319–5324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L., Zullo M., Goldberg J. (2008). The association between heavy metals, endometriosis and uterine myomas among premenopausal women: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Hum. Reprod. 23, 679–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen K. B., Dredge B. K., Stefani G., Zhong R., Buckanovich R. J., Okano H. J., Yang Y. Y., Darnell R. B. (2000). Nova-1 regulates neuron-specific alternative splicing and is essential for neuronal viability. Neuron 25, 359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Goto S. (2000). KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M., Richards R. I. (1984). The human metallothionein gene family: Structure and expression. Environ. Health Perspect. 54, 111–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent W. J., Sugnet C. W., Furey T. S., Roskin K. M., Pringle T. H., Zahler A. M., Haussler D. (2002). The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12, 996–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. H., Leslie P., Zhang Y. (2014). Ribosomal proteins as unrevealed caretakers for cellular stress and genomic instability. Oncotarget 5, 860–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan P. J. (2010). What causes autism? Exploring the environmental contribution. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 22, 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., Salzberg S. L. (2009). Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10, R25.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. H., Lee S. K., Kim H. S., Cho E. J., Joo H. K., Lee E. J., Lee J. Y., Park M. S., Chang S. J., Cho C.-H. (2009). Overexpression of Ref-1 inhibits lead-induced endothelial cell death via the upregulation of catalase. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 13, 431–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng N., Dawson J. A., Thomson J. A., Ruotti V., Rissman A. I., Smits B. M., Haag J. D., Gould M. N., Stewart R. M., Kendziorski C. (2013). EBSeq: An empirical Bayes hierarchical model for inference in RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics 29, 1035–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Dewey C. N. (2011). RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 323.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. Z., Bu H. L., Yang M. Q., Zeng X. Q., Yang J. Y. (2008). Selecting subsets of newly extracted features from PCA and PLS in microarray data analysis. BMC Genomics 9(Suppl 2), S24.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidsky T. I., Schneider J. S. (2003). Lead neurotoxicity in children: Basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Brain 126, 5–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidsky T. I., Schneider J. S. (2005). Autism and autistic symptoms associated with childhood lead poisoning. J. Appl. Res. 5, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Deisenroth C., Zhang Y. (2016). RP–MDM2–p53 pathway: Linking ribosomal biogenesis and tumor surveillance. Trends Cancer 2, 191–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao-De L., Jing X. (2007). Ribosomal proteins and colorectal cancer. Curr. Genomics 8, 43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister J. M., Modi B., Miller B. A., Biegler J., Bruggeman R., Legro R. S., Strauss J. F. (2014). Overexpression of a DENND1A isoform produces a polycystic ovary syndrome theca phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, E1519–E1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal A. P., Worley P. F., Guilarte T. R. (2011). Lead exposure during synaptogenesis alters NMDA receptor targeting via NMDA receptor inhibition. Neurotoxicology 32, 281–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg J. T., Nikolas M., Mark Knottnerus G., Cavanagh K., Friderici K. (2010). Confirmation and extension of association of blood lead with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and ADHD symptom domains at population‐typical exposure levels. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 51, 58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opler M. G., Brown A. S., Graziano J., Desai M., Zheng W., Schaefer C., Factor-Litvak P., Susser E. S. (2004). Prenatal lead exposure, delta-aminolevulinic acid, and schizophrenia. Environ. Health Perspect. 112, 548.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto D., Fox D. (1992). Auditory and visual dysfunction following lead exposure. Neurotoxicology 14, 191–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S. R., Lee A., Bishop G. M., Czerwinska H., Dringen R. (2015). Inhibition of astrocytic glutamine synthetase by lead is associated with a slowed clearance of hydrogen peroxide by the glutathione system. Front Integr. Neurosci. 9, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh H. A., El‐Aziz G. A., El‐Fark M. M., El‐Gohary M. (2009). Effect of maternal lead exposure on craniofacial ossification in rat fetuses and the role of antioxidant therapy. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 38, 392–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman A. L., Pan Q., Blencowe B. J. (2011). Regulation of alternative splicing by the core spliceosomal machinery. Genes Dev. 25, 373–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Martin F. J., Fan Y., Lindquist D. M., Xia Y., Puga A. (2013). Lead induces similar gene expression changes in brains of gestationally exposed adult mice and in neurons differentiated from mouse embryonic stem cells. PloS One 8, e80558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J., Kidd S., Anderson D. (2013). Influence of developmental lead exposure on expression of DNA methyltransferases and methyl cytosine-binding proteins in hippocampus. Toxicol. Lett. 217, 75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J. S., Anderson D. W., Talsania K., Mettil W., Vadigepalli R. (2012). Effects of developmental lead exposure on the hippocampal transcriptome: Influences of sex, developmental period, and lead exposure level. Toxicol. Sci. 129, 108-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senut M. C., Sen A., Cingolani P., Shaik A., Land S. J., Ruden D. M. (2014). Lead exposure disrupts global DNA methylation in human embryonic stem cells and alters their neuronal differentiation. Toxicol. Sci. 139, 142–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S., Park J. W., Huang J., Dittmar K. A., Lu Z. X., Zhou Q., Carstens R. P., Xing Y. (2012). MATS: A Bayesian framework for flexible detection of differential alternative splicing from RNA-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e61.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Zhao H., Shi Y., Cao Y., Yang D., Li Z., Zhang B., Liang X., Li T., Chen J. (2012). Genome-wide association study identifies eight new risk loci for polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat. Genet. 44, 1020–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui M., Srivastava S., Mehrotra P. (2002). Environmental exposure to lead as a risk for prostate cancer. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 15, 298–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smola A., Vapnik V. (1997). Support vector regression machines. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 9, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Suszkiw J. B. (2004). Presynaptic disruption of transmitter release by lead. Neurotoxicology 25, 599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Pachter L., Salzberg S. L. (2009). TopHat: Discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 25, 1105–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Burge C. B. (2008). Splicing regulation: From a parts list of regulatory elements to an integrated splicing code. Rna 14, 802–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten J. T., Ule J. (2011). Understanding splicing regulation through RNA splicing maps. Trends Genet. 27, 89–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Basha M. R., Brock B., Cox D. P., Cardozo-Pelaez F., McPherson C. A., Harry J., Rice D. C., Maloney B., Chen D. (2008). Alzheimer's disease (AD)-like pathology in aged monkeys after infantile exposure to environmental metal lead (Pb): Evidence for a developmental origin and environmental link for AD. J. Neurosci. 28, 3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawia N. H., Harry G. J. (1996). Developmental exposure to lead interferes with glial and neuronal differential gene expression in the rat cerebellum. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 138, 43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A., Hu H., Sanchez B. N., Ettinger A. S., Park S. K., Cantonwine D., Schnaas L., Wright R. O., Lamadrid-Figueroa H., Tellez-Rojo M. M. (2012). Association between prenatal lead exposure and blood pressure in children. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 445–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Darnell R. B. (2011). Mapping invivo protein-RNA interactions at single-nucleotide resolution from HITS-CLIP data. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 607–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W., Blaner W. S., Zhao Q. (1999). Inhibition by lead of production and secretion of transthyretin in the choroid plexus: Its relation to thyroxine transport at blood–CSF barrier. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 155, 24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Liao W.-J., Liao J.-M., Liao P., Lu H. (2015). Ribosomal proteins: Functions beyond the ribosome. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.