Abstract

Although facial affect recognition deficits are well documented in individuals with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), little research has examined the neural mechanisms underlying these impairments. Here, we use diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), specifically the scalars fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), and radial diffusivity (RD), to examine relationships between regional white-matter integrity and two facial affect sub-skills: perceptual affect recognition abilities (measured by an affect matching task) and verbal categorization of facial affect (measured by an affect labeling task). Our results showed that, within the TBI group, higher levels of white-matter integrity in tracts involved in affect recognition (inferior fronto-occipital, inferior longitudinal, and uncinate fasciculi) were associated with better performance on both tasks. Verbal categorization skills were specifically and positively correlated with integrity of the left uncinate fasciculus. Moreover, we observed a striking lateralization effect, with perceptual abilities having an almost exclusive relationship with integrity of right hemisphere tracts, while verbal abilities were associated with both left and right hemisphere integrity. The findings advance our understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms that underlie subcomponents of facial affect recognition and lead to different patterns of facial affect recognition impairment in adults with TBI.

Keywords: TBI, emotion recognition, emotion labeling, facial affect recognition, emotion matching, fractional anisotropy

Introduction

Diffuse axonal injury is the hallmark of moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), resulting in widespread disruption of white matter pathways that form connections both within and between different brain lobes (Adams, Doyle, Graham, Lawrence, & McLellan, 1984; Adams, Graham, & Jennett, 2001; Gaetz, 2004). Studies of individuals with TBI have revealed positive correlations between degree of white matter damage (measured using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)) and poorer performance across a range of cognitive tasks (Kennedy et al., 2009; Kinnunen et al., 2011; Kraus et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2009; Sharp et al., 2011), with a growing body of studies examining these relationships in the social domain (e.g., interpersonal communication, theory of mind) (Rigon, Voss, Turkstra, Mutlu, & Duff, 2016; Ryan, Catroppa, et al., 2017; Ryan, Genc, et al., 2017).

Social impairment has been widely reported in individuals with moderate-to-severe TBI and has been identified as a major predictor of overall outcome (Andrews, Rose, & Johnson, 1998; Duff, Mutlu, Byom, & Turkstra, 2012; Gomez-Hernandez, Max, Kosier, Paradiso, & Robinson, 1997; Milders, Fuchs, & Crawford, 2003; Morton and Wehman, 1995; Temkin, Corrigan, Dikmen, & Machamer, 2009; Ylvisaker, Turkstra, & Coelho, 2005). In particular, facial affect recognition ability (i.e., the ability to correctly identify what a person is feeling by looking at his or her face) has shown strong associations with negative social outcomes, such as deficits in social communication (Pettersen, 1991; Rigon, Turkstra, Mutlu, & Duff, In press; Watts and Douglas, 2006), lower levels of social integration (Knox and Douglas, 2009), and higher frequency of socially inappropriate behaviors (Pettersen, 1991). The ability to correctly recognize affect varies highly from individual to individual, and marked inter-individual differences have been reported within both healthy populations (Germine and Hooker, 2011; Kessels, Montagne, Hendriks, Perrett, & de Haan, 2014; Palermo, O’Connor, Davis, Irons, & McKone, 2013; Tamamiya and Hiraki, 2013) and also brain injury populations (Babbage et al., 2011; Rigon, Turkstra, Mutlu, & Duff, 2016a; Rosenberg, Dethier, Kessels, Westbrook, & McDonald, 2015). Indeed, individuals with TBI with similar initial injury severity levels (i.e., “mild”, “moderate”, “severe”) (Malec et al., 2007), can display large differences in affect recognition skills, as well as in overall social outcome (Rigon, Turkstra, Mutlu, & Duff, 2016b; Rosenberg, et al., 2015; Rosenberg, McDonald, Dethier, Kessels, & Westbrook, 2014). Such within-population variability can weaken the validity of standard classification systems, as well as negatively affect our ability to correctly detect and make accurate outcome predictions regarding social outcome following TBI. Thus, a deeper understanding of the factors driving individual differences within TBI populations is necessary to the development of more accurate diagnostic and prognostic tools.

The combination of neuroimaging and rigorous behavioral testing can explain part of the observed individual variability in affect recognition skills. For instance, by combining imaging techniques that capture brain structure and function (e.g., electroencephalography, functional and structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging) with facial affect recognition tasks that are sensitive to inter-individual differences, we can identify brain-behavior relationships that underlie facial affect processing deficits secondary to TBI. Following this approach, in a recent study by our group (Rigon, Voss, Turkstra, Mutlu, & Duff, 2017), individuals with TBI (mean age 50.92 years, mean chronicity 73.54 months) showed significantly lower resting state-functional connectivity (rs-FC) in comparison to healthy controls within regions that are part of the facial affect processing network (for a review of rs-FC, see Power, Schlaggar, & Petersen, 2014). Similarly, we found a significant positive association between performance on an affect labeling task in individuals with TBI and the strength of rs-FC within said network. Others have used event-related fMRI to examine brain activation in response to affect labeling, and reported a negative association between activation in secondary visual areas and number of affect labeling errors (Neumann, McDonald, West, Keiski, & Wang, 2015). These findings indicate that individual differences in affect recognition performance following TBI can be partly explained by alterations in neural functioning.

To date, only one study (Genova et al., 2015) examined the relationship between diffuse axonal injury and affect recognition in individuals with TBI. In this study, adults with moderate-severe TBI completed an affect matching task and an affect labeling task from the Facial Affect Identification Test (FEIT) (Kerr and Neale, 1993), and the authors correlated task scores with DTI measures of white matter integrity. These two tasks are designed to measure different aspects of facial-affect recognition: the affect matching task focused on perceptual aspects of affect recognition (i.e., the ability to detect facial configurations that are relevant to interpret affects and carry salient emotional information, such as a smile), and the affect labeling task required participants to link facial configurations to emotional labels (e.g., smile=happiness) (Hariri, Bookheimer, & Mazziotta, 2000; Palermo, et al., 2013). Thus, affect matching tasks primarily test perceptual recognition skills, while emotional labeling tasks test both perception and also semantic categorization. The resulting, data-supported theoretical model of the cognitive processes involved in facial affect recognition postulates that affect matching and labeling tasks tap into partially overlapping and partially separate processes; moreover, they represent two subsequent stages, with perceptual processes (emotion matching) preceding interpretative processes (semantic categorization or emotion labeling). Genova and colleagues did not report a relationship between affect labeling performance and DTI scalars, although they found a significant positive correlation between affect labeling accuracy and the integrity of the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus and the inferior longitudinal fasciculus. These two white matter tracts have been reported to be involved in affect recognition in other studies, and they connect occipital visual regions with limbic temporal and prefrontal areas, playing a role in facial recognition and processing of affective stimuli (Catani et al., 2003; Martino, Brogna, Robles, Vergani, & Duffau, 2010; Philippi, Mehta, Grabowski, Adolphs, & Rudrauf, 2009).

Genova and colleagues (2015) collected only 12 DTI directions, which reduces reliability and increases variability in the resulting images (Wang, Abdi, Bakhadirov, Diaz-Arrastia, & Devous, 2012), and their affect recognition tasks had a relatively small number of trials. In addition, static affect recognition tasks (i.e., from photographs) often suffer from ceiling effects, and while they can be useful for discriminating between typical and clinical samples, they are not designed to capture individual differences (Palermo, et al., 2013). Although Genova et al. (Genova, et al., 2015) did not report whether data collected on their sample was normally distributed, they did state that the small number of trials might have influenced their ability to definitively interpret the data. Their findings clearly indicate that specific patterns of diffuse axonal injury are associated with facial-affect recognition impairment.

In the current study, we aimed to expand on the findings of Genova and colleagues, and further examine the specific relationship between perceptual and verbal categorization and DTI scalars in a sample of individuals with TBI. In a previous study (Rigon, Voss, Turkstra, Mutlu & Duff, in press), adults with moderate-to-severe TBI and demographically matched healthy comparisons completed an affect matching and an affect labeling task. The tasks administered were adapted from Palermo and colleagues (2013), and specifically designed to highlight individual variability in different aspects of affect recognition performance, as well as to avoid ceiling effects (Palermo, et al., 2013). Results showed that while individuals with TBI significantly underperformed healthy comparison participants on both perceptual and interpretative tasks, they were significantly more likely to show impairment on interpretative tasks than on perceptual tasks, indicating that within TBI populations affect recognition deficits might strongly be driven by a breakdown in later stages within the facial affect processing pipeline.

Here, we expand on our prior results by examining the structural neural correlates of behavioural impairments, to further characterize the neural mechanisms of affect recognition deficits. We used diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) to examine white matter integrity and its relationship with performance on affect matching and affect labeling tasks. We hypothesized that DTI values corresponding to higher white matter integrity in tracts carrying visual information to temporal and prefrontal regions would be associated with higher accuracy on both tasks. We also aimed to differential neural correlates for perceptual vs. verbal-categorization tasks, for affect recognition in individuals with TBI vs. healthy comparison peers.

Methods

Participants

Thirty-three individuals with moderate-severe TBI and 24 healthy comparisons (HC) were tested for this study. Participants were recruited through the University of Iowa community and through the University of Iowa Brain Injury Registry (Rigon, Turkstra, et al., 2016a; Rigon, Voss, et al., 2016; Rigon, et al., 2017). All participants were part of a larger behavioral study (Rigon, Voss, Turkstra, Mutlu & Duff, in press). The original study included 38 individuals with TBI and 24 HCs; sample size difference between the current study and behavioral study is due to the fact that 5 participants with TBI were not MRI compatible, and thus were not enrolled for the imaging study. Inclusionary criteria for individuals with TBI were (1) history of moderate to severe TBI, (2) chronic post-injury phase (all participants were > 12 months post injury), (3) aphasia quotient higher than 93.8 on the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) (Malec, et al., 2007; Shewan and Kertesz, 1980). Language deficits were ruled out to ensure that participants were able to correctly understand instruction, and that poor performance on the tasks administered was not due to such deficits. For one participant in the TBI group, only half of the DTI directions were recorded due to a power outage during data acquisition, and their data were discarded. The groups were not significantly different for age (t(38.38)=1.03, p>.05), education t(53)=−.63, p>.05), or sex (X2(1, N=55)=1.08, p>.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of healthy comparison sample and individuals with traumatic brain injury

| N | AGE (Mean±SD) |

SEX (Females) |

EDUCATION (Mean±SD) |

CHRONICITY (Months, Mean±SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | 24 | 48.29±20.14 | 16 | 15.5±2.15 | N/A |

| TBI | 31 | 53.19±13.58 | 9 | 15.13±2.19 | 107.45(±122.64) |

| Group Differences (p) | N/A | .31 | .29 | .53 | N/A |

Note: HC=Healthy comparison participants, TBI=Traumatic brain injury, p-value, SD=Standard Deviation, N/A=Not Applicable.

Participants had sustained their TBI a minimum of 17 months and a maximum of 509 months before testing (Mean=107.45, SD=122.64). One participant had sustained two separate TBIs. Causes of injury were falls (17), motor vehicle accidents (11), assaults (2), and non-motor vehicle accidents (2).

TBI severity was assessed using the Mayo Classification System. (Malec, et al., 2007) Participants were considered moderate-severe if at least one of the following criteria was met: (1) Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)<13 (i.e., moderate or severe according to the GCS), (2) positive acute CT findings or lesions visible on a chronic MRI, (3) loss of consciousness (LOC)>30 minutes or post-traumatic amnesia (PTA)>24 hours, and (4) retrograde amnesia>24 hours. Injury-related information was collected using a combination of medical records and a semi-structured interview with participants. In the current sample, information on GCS was available for 18 participants, on LOC for 9 participants, information on retrograde or anterograde amnesia on 20 participants, and on CT or MRI findings for 28 participants.

Inclusionary criteria for HC were: 1) no self-reported history of head injury or loss of consciousness, 2) no history of neurological, psychiatric or learning disorders, and 3) aphasia quotient higher than 93.8 on the WAB.

Affect recognition tasks

Two affect recognition tasks (Matching and Labeling) were administered to both individuals with TBI and HCs. The tasks were specifically designed to avoid ceiling effects and measure inter-individual differences in facial affect recognition, even in healthy populations (Palermo, et al., 2013).

The matching task (Matching) used here is an odd-expression-out task, in which participants see three faces displaying an emotional expression. Two faces of different individuals showed the same expression, and a third shows a different expression. Each trial has three different actors. Participants are asked to indicate the face displaying a different affect from the other two. The target affect and distractor affects were always one of the six basic affects (anger, happiness, disgust, fear, sadness and surprise). For further information on the development, characteristics and psychometric properties of both the matching and the labeling task, see Palermo et al, 2013, as well as Rigon et al, in press, for information on how they were modified for the current study.

The version employed here consisted of 100 trials, each trial lasting a maximum of 10 seconds: participants saw all three faces simultaneously for 5 seconds (trial duration was lengthened to adapt the task for a TBI population while retaining a limited duration, to render the task as ecological as possible and avoid ceiling effects; for further information on the original task, see Palermo and colleagues, 2013). After 5 seconds, the stimuli disappeared, and participants were allowed 5 more seconds to make their choice by pressing the button (1, 2 or 3) corresponding to the face showing the different affect. Participants could select the correct answer whenever they preferred during the 10 seconds. Every twenty trials, participants were given the opportunity to take a break. We ensured that each participant was able to produce a motor response in the allotted time, and that individuals with TBI were not penalized by the duration of the task.

In the labeling task (Labeling) consist of 144 trials. Each trial lasted a total of 10 seconds, with a face presented in the center of the screen for 2 seconds, followed by an 8 seconds blank screen. In order to decrease the working memory demand, for the whole 10 seconds, labels of the six basic affects remained visible at the bottom of the screen, and participants were asked to select the one corresponding to the affect shown by the stimulus. Participants could select the correct answer any time in the 10 seconds available. As soon as participants selected their answer, the tasked moved to the next trial. Participants could not change their answer after making a decision.

The matching task was always administered before the labeling task. This was decided following the procedure adopted by the creators of the task (Palermo, et al., 2013).

Dependent variable for each task was number of correct trials. Statistical analysis of the affect recognition task was carried out using one-tailed t-tests to compare performance between the two groups (with the hypothesis that individuals with TBI would underperform HCs). Moreover, to examine the difference in patterns of impairment between the two tasks within the TBI group, we calculated normative scores for each task using the average of the HC group, and then determined which individuals with TBI were impaired on each affect recognition task by using impairment thresholds that corresponded to 2 standard deviations below the average of the HC group. Following this procedure, a McNemar’s test was used to determine whether nominal dichotomous variable (impaired vs. non-impaired) differed between the affect recognition tests.

Neuroimaging data acquisition

Neuroimaging data were collected at the University of Iowa Magnetic Resonance Facilities, on a 3T whole-body GE MR750W scanner with a 32-channel RF head receive coil. High-resolution T1-weighted brain images were acquired using a 3D Brain Volume (BRAVO) protocol with 256 interleaved coronal slices, inversion time (TI)=450ms, echo time (TE)=3.25 ms, repetition time (TR)=8.46 ms, field of view (FOV)=256mm2, voxel size=1mm3, and flip angle=12°.

DTI images were collected with 70 slices acquired in descending order, TE=74.5, TR= 15339 ms, voxel size=2mm3, FOV=256mm2, and flip angle=90°; one T2-weighted image (b-value=0 s/mm2) and one 30-direction diffusion-weighted echo planar imaging scan (b-value=1000 s/mm2) were collected. The final N for the DTI sample was 55 (TBI=31, HC=24).

Neuroimaging Data Analysis

DTI data preprocessing was carried out in FSL 5.0.4 with the FMRIB’s Diffusion Toolbox (FDT) to correct for eddy currents and fit diffusion tensors and using the Brain Extraction Tool for removal of non-brain structures (Behrens et al., 2003; Smith, 2002; Smith et al., 2004). The measures examined were Fractional Anisotropy (FA), Mean Diffusivity (MD), Radial Diffusivity (RD) and Axial Diffusivity (AD). FA is an indicator of compactness and orientation of white matter fibers, and it is based on water’s diffusion over one direction (Hulkower, Poliak, Rosenbaum, Zimmerman, & Lipton, 2013; Werring, Clark, Barker, Thompson, & Miller, 1999). Higher FA values correspond to higher unidirectionality, as well as the integrity of white matter pathways (Basser, 1995; Beaulieu, 2002; Sen and Basser, 2005). FA was chosen as the primary scalar value of interest, as previous work has been suggested that it may be a better marker of white matter abnormalities; MD is an inverse measure of membrane density, with higher values corresponding to lower integrity and higher diffusion of water molecules in all directions; AD is a measure linked with pathology and damage of white matter, with lower values indicating higher degrees of white matter damage; finally, RD has been associated with myelination, with higher RD values corresponding to higher degrees of demyelination (Cubon, Putukian, Boyer, & Dettwiler, 2011). All of these scalars have been previously employed in TBI research, as well as in the study of white matter integrity for other clinical and healthy populations (Alexander, Lee, Lazar, & Field, 2007; Kinnunen, et al., 2011; Racine et al., 2014).

All images were processed with a voxel-wise statistical analysis using Tract-Based Spatial Statistics: the nonlinear registration tool FNIRT was used to transform all subjects’ FA and MD data onto the FMRIB58_FA standard-space image and then to project each subject’s FA and MD data onto a mean skeleton (Andersson, Jenkinson, & Smith, 2007a, 2007b; Smith et al., 2006).

First, to determine between-group differences in white matter integrity a whole-brain comparison of FA, MD, AD and RD skeletons was computed using the nonparametric permutation tool randomise (Winkler, Ridgway, Webster, Smith, & Nichols, 2014). When between-group differences in scalar values were assessed, age was used as a covariate in order to account for the high-variability in age within both groups, considering the high correlations consistently reported between age and DTI scalars (Back et al., 2011; Salat et al., 2005). Results were visualized by applying a threshold of p<.05 to the resulting family-wise error corrected statistical maps. In order to identify white matter tracts where statistically significant clusters in local white matter integrity were located, the JHU-White Matter Atlas and the JHU ICBM-DTI-81 White-Matter Labels Atlas (Hua et al., 2008; Wakana et al., 2007) were overlapped with the resulting statistical images.

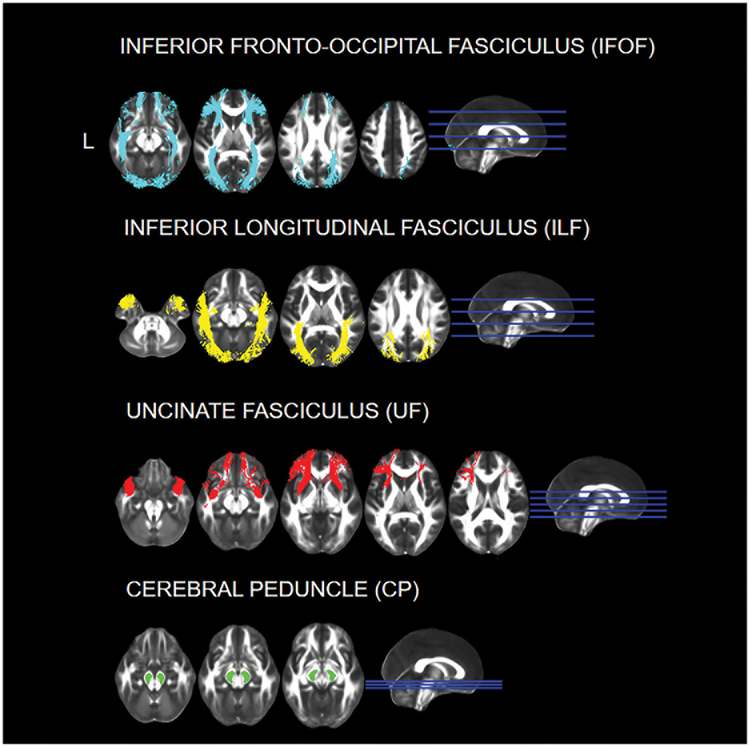

Next, we used an a priori approach to carry out a region of interest (ROI) specific analysis on all participants for the four scalar values. The ROIs were selected based on previous literature and include the bilateral inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF), the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF) and the uncinate fasciculus (UF) (Genova, et al., 2015; Philippi, et al., 2009). These white matter tracts are responsible for connecting the occipital, temporal and frontal lobe, and have been found to be involved in facial affect recognition in both lesion studies in individuals with a variety of etiologies and DTI studies on individuals with TBI. As a control ROI, we selected white matter tracts thought to be unrelated to affect recognition abilities (left and right cerebral peduncle, CP) (see Figure 1) (Genova, et al., 2015; Philippi, et al., 2009).

Figure 1. Regions of Interest for the DTI Analysis.

The ROIs were selected using the JHU ICBM-DTI-81 White-Matter Labels and White Matter tracts Atlases. Images are presented in neurological convention (L=L).

One tailed t-tests were carried out to test our hypothesis that scalar values would be lower (in the case of FA) and higher (in the case of AD, MD and RD) in the TBI group. Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison was applied, so that a group difference was considered significant if p<(.05/8)=.0063. Next, for the primary analysis of interest, we examined the differential association between white matter tracts and different aspects of affect recognition abilities by computing partial correlations between scalar values in each of the ROIs and performance on the Matching and Labeling tasks, accounting for age and sex. Similarly to previous studies, Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons (.05/8=.0063; all p-values <.0063 were considered significant). (Rigon, Voss, et al., 2016) Lastly, considering successful performance in the Matching task requires mainly perceptual skills, while successful performance in the Labeling requires both perceptual and verbal categorization skills, a final analysis was carried out within the TBI group to examine the partial correlation between Labeling and white matter scalar values in the ROIs by accounting for age, sex, and also Matching performance.

In addition, to further determine the differential neural correlates of affect labeling and affect matching within both the TBI and the HC group, we performed an exploratory analysis using the randomise tool. First, a nonparametric analysis was run for each group and each scalar value to examine the presence of an interaction, i.e. whether the linear relationship between Matching (or Labeling) and white matter integrity was significantly different between individuals with TBI and HCs, with age and sex as covariates. The choice of adding age as a covariate was due to the high correlation between age and performance on both tasks (for the DTI sample, in the TBI group the 2-tailed Pearson’s correlation between age and Matching score was r=−.53, p<.01, and the correlation with Labeling was r=−.54, p<.01; for the HC group, the correlation between age and Matching score was r=−.56, p<.01, and the correlation with Labeling was r=−.43, p<.05). Moreover, age has been found to be highly negatively associated with DTI scalar values (Bennett, Madden, Vaidya, Howard, & Howard, 2010; Grieve, Williams, Paul, Clark, & Gordon, 2007; McLaughlin et al., 2007). Similar considerations were made when adding sex as a covariate (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014). Next, we set as regressors Matching and Labeling scores (in separate analyses) and added age and sex as a covariate. These analyses were carried out both within the TBI and the HC group for all scalar values.

Results

Affect recognition tasks

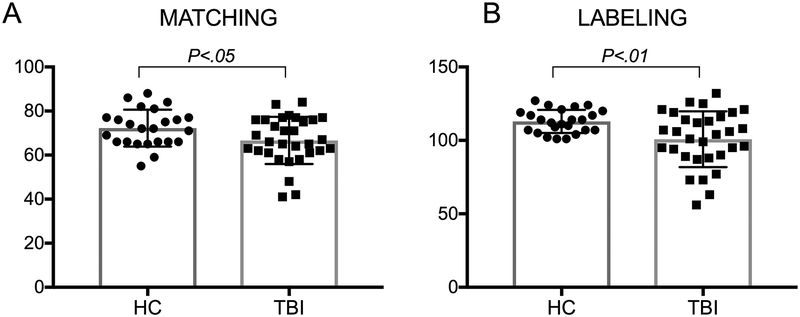

As predicted, and in line with the findings reported in the larger behavioral sample (Rigon, Voss, Turkstra, Mutlu & Duff, in press) two one-tailed t-tests showed that individuals with TBI underperformed HCs in both the labeling (t(42.02)=−3.22, p<.01; TBI Mean=100.81±18.98, HC Mean=112.91±7.84) and the matching (t(53)=−2.11, p<.05; TBI Mean=66.65±10.7, HC Mean=72.25±8.38) tasks (See Figure 2). This suggests that individuals with TBI underperformed HCs both on tests measuring perceptual and verbal categorization facial affect recognition skills.

Figure 2. Group comparison on the matching and labeling tasks.

Individuals with TBI underperformed HCs on both the perceptual and the verbal categorization facial affect recognition tasks.

The McNemar’s test (on paired nominal data) revealed that 43.8% of individuals with TBI were impaired in the labeling task, while only 9.4% in the matching task: individuals with TBI who showed impairment in the labeling task were significantly higher in number that those who were impaired at matching (p=.001).

ROI analysis - group comparison

One-tailed independent sample t-tests revealed that individuals with TBI had significantly lower FA (i.e., lower white matter integrity) than HCs in all white matter tracts of interest (all t(53)>3.09, all p<.006), with the exception of the left cerebral peduncle (t(53)=2.21, p>.006). For MD, no white matter tract was significantly different between groups (all t(53)<2.08, all p>.006), with the exception of the right UF, which showed higher levels of MD (i.e., lower white matter integrity) in individuals with TBI (t(49.74)=2.8, p<.006). For RD, the white matter tracts that were significantly different between groups after multiple comparison correction were the right IFOF (t(53)=2.66, p<.006) and the right (t(53)=3.17, p<.006) and left UF (t(53)=2.62, p<.006), with higher RD values in the TBI group (i.e., lower white matter integrity). The were no significant differences in AD between the two groups (all t(53)<2.08, all p>.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Group Comparison on DTI scalars

| HC (Mean±SD) |

TBI (Mean±SD) |

GROUP DIFFERENCE, p, Cohen’s d |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left IFOF | FA | .49±.02 | .47±.02 | .001, .87 |

| MD | .00075±.00003 | .00077±.00003 | .033, .53 | |

| RD | .00052±.00003 | .00055±.00004 | .008, .6 | |

| AD | .0012±.00004 | .0012±.00004 | .47, .02 | |

| Right IFOF | FA | .5±.02 | .49±.02 | <.001, .9 |

| MD | .00074±.00003 | .00075±.00003 | .032, .53 | |

| RD | .00051±.00003 | .00053±.00004 | .005, .69 | |

| AD | .0012±.00004 | .0012±.00003 | .39, .08 | |

| Left UF | FA | .46±.02 | .44±.03 | <.001, .96 |

| MD | .00075±.00003 | .00078±.00005 | .021, .58 | |

| RD | .00055±.00003 | .00058±.00005 | .006, .74 | |

| AD | .0012±.00003 | .0012±.00004 | .29, .15 | |

| Right UF | FA | .46±.02 | .44±.03 | <.001, 1.06 |

| MD | .00077±.00003 | .0008±.00005 | .004, .87 | |

| RD | .00057±.00003 | .0006±.00005 | <.001, .9 | |

| AD | .0012±.00003 | .0012±.00004 | .18, .26 | |

| Left ILF | FA | .48±.02 | .46±.03 | .002, .82 |

| MD | .00075±.00003 | .00077±.00004 | .07, .44 | |

| RD | .00053±.00003 | .00056±.00005 | .02, .7 | |

| AD | .0012±.00004 | .0012±.00004 | .47, .01 | |

| Right ILF | FA | .49±.02 | .47±.02 | .002, .86 |

| MD | .00073±.00003 | .00074±.00003 | .05, .48 | |

| RD | .00051±.00003 | .00053±.00004 | .008, .74 | |

| AD | .0012±.00004 | .0012±.00004 | .44, .03 | |

| Left CP | FA | .75±.02 | .73±.03 | .02, .61 |

| MD | .00066±.00004 | .00065±.00005 | .21, .23 | |

| RD | .0003±.00003 | .00031±.00004 | .23, .2 | |

| AD | .0014±.00008 | .0013±.00008 | .02, .57 | |

| Right CP | FA | .76±.02 | .74±.03 | .002, .86 |

| MD | .00065±.00004 | .00065±.00005 | .4, .07 | |

| RD | .00029±.00003 | .00031±.00004 | .04, .5 | |

| AD | .0014±.00008 | .0014±.00007 | .05, .44 |

Note: HC=Healthy comparison participants, TBI=Traumatic brain injury, p-value, SD=Standard Deviation, DTI=Diffusion tensor imaging, FA=Fractional anisotropy, MD=Mean diffusivity, RD=Radial diffusivity, AD=Axial diffusivity, IFOF= Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus, ILF=Inferior longitudinal fasciculus, UC=Uncinate fasciculus.

ROI analysis - correlations

FA.

Within the TBI group, when accounting for age and sex, we found a significant positive correlation between Matching and Labeling performance and FA values of the following ROIs: left (Matching: r=.51, p<.006; Labeling: r=.51, p<.006) and right IFOF (Matching: r=.53, p<.006; Labeling: r=.50, p<.006) and right ILF (Matching: r=.50, p<.006; Labeling: r=.48, p<.006). There was a significant correlation between FA in the left ILF and Labeling (r=.51, p<.006), but not Matching (r=.44, p>.006), as well as a significant correlation between FA in the left UF and Labeling (r=.6, p<.001), but not Matching (r=.43, p>.006). FA in the other ROIs (right UF and bilateral CP) were not significantly associated with either Matching nor Labeling (.12<r<.38, all p>.01). Within the HC group, there were no significant correlations between white matter FA in the selected ROIs and Matching or Labeling performance (.22<r<−.32, all p>.05) (See Tables 3 & 4). We used a Fisher’s R to Z transform to compare correlation coefficients between the TBI group and the HC group, focusing on those ROIs that were significantly correlated with performance within the TBI group. We found a significant group difference (with higher correlation for the TBI group) between Labeling and the left UF (Z=1.77, p<.05), Matching and the right IFOF (Z=2.92, p<.01), matching and the left UF (Z=2.62, p<.01), and matching and the right ILF (Z=2.24, p<.05).

Table 3.

Correlations between DTI scalar values and Matching and Labeling performance in the TBI group.

| Matching (r, p) |

Labeling (r, p) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Left IFOF | FA | .51, .002 | .54, .001 |

| MD | −.44, .008 | −.49, .004 | |

| RD | −.47, .005 | −.53 .002 | |

| AD | −.29, .06 | −.3, .06 | |

| Right IFOF | FA | .54, .001 | .5, .003 |

| MD | −.42, .01 | −.39, .02 | |

| RD | −.49, .004 | −.47 .005 | |

| AD | −.14, .23 | −.1, .31 | |

| Left UF | FA | .43, .001 | .6, <.001 |

| MD | −.32, .05 | −.52, .002 | |

| RD | −.36, .03 | −.57, .001 | |

| AD | −.19, .16 | −.37, .02 | |

| Right UF | FA | .33, .04 | .38, .02 |

| MD | −.3, .06 | −.38, .02 | |

| RD | −.33, .04 | −.4, .02 | |

| AD | −.18, .18 | −.29, .07 | |

| Left ILF | FA | .44, .009 | .51, .002 |

| MD | −.28, .07 | −.47, .005 | |

| RD | −.32, .05 | −.51, .002 | |

| AD | −.16, .12 | −.33, .04 | |

| Right ILF | FA | .5, .003 | .48, .004 |

| MD | −.28, .07 | −.36, .03 | |

| RD | −.37, .03 | −.44, .009 | |

| AD | −.04, .42 | −.12, .26 | |

| Left CP | FA | .26, .09 | .32, .05 |

| MD | −.08, .34 | −.03, .44 | |

| RD | −.08, .33 | −.2, .15 | |

| AD | .25, .1 | .19, .17 | |

| Right CP | FA | .12, .27 | .14, .23 |

| MD | .11, .29 | .01, .48 | |

| RD | .01, .47 | −.08, .34 | |

| AD | .21, .14 | .14, .24 | |

| AD | −.16, .12 | −.33, .04 |

Note: TBI=Traumatic brain injury, p-value, SD=Standard Deviation, DTI=Diffusion tensor imaging, FA=Fractional anisotropy, MD=Mean diffusivity, RD=Radial diffusivity, AD=Axial diffusivity, IFOF= Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus, ILF=Inferior longitudinal fasciculus, UC=Uncinate fasciculus.

Table 4.

Correlations between DTI scalar values and Matching and Labeling performance in the HC group.

| Matching (r, p) |

Labeling (r, p) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Left IFOF | FA | −.25, .12 | .18, .21 |

| MD | .3, .09 | −.27, .11 | |

| RD | .31, .08 | −.22, .16 | |

| AD | .22, .16 | −.33, .07 | |

| Right IFOF | FA | −.32 .07 | .13, .28 |

| MD | .3, .09 | −.34, .06 | |

| RD | .34, .06 | −.26, .13 | |

| AD | .19, .2 | −.45, .02 | |

| Left UF | FA | −.26, .13 | .13, .28 |

| MD | .26, .12 | −.34, .06 | |

| RD | .28, .11 | −.28, .1 | |

| AD | .21, .17 | −.43, .02 | |

| Right UF | FA | −.29, .09 | .03, .44 |

| MD | .32, .07 | −.32, .07 | |

| RD | .34, .06 | −.24, .14 | |

| AD | .24, .14 | −.43, .02 | |

| Left ILF | FA | −.21, .18 | .15, .25 |

| MD | .32, .07 | −.19, .2 | |

| RD | .31, .08 | −.17, .23 | |

| AD | .28, .11 | −.21, .17 | |

| Right ILF | FA | −.16, .25 | .22, .16 |

| MD | .29, .09 | −.33, .07 | |

| RD | .29, .1 | −.29, .1 | |

| AD | .27, .11 | −.38, .04 | |

| Left CP | FA | .01, .48 | −.19, .21 |

| MD | .36, .05 | .17, .23 | |

| RD | .25, .14 | .25, .13 | |

| AD | .32, .07 | .03, .44 | |

| Right CP | FA | .08, .36 | −.03, .45 |

| MD | .37, .05 | .1, .33 | |

| RD | .2, .19 | .13, .28 | |

| AD | .41, .03 | .03, .45 |

Note: HC=Healthy comparison participants, p-value, SD=Standard Deviation, DTI=Diffusion tensor imaging, FA=Fractional anisotropy, MD=Mean diffusivity, RD=Radial diffusivity, AD=Axial diffusivity, IFOF= Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus, ILF=Inferior longitudinal fasciculus, UC=Uncinate fasciculus.

MD.

Within the TBI group, there were no significant correlations between white matter MD in the selected ROIs and Matching or Labeling performance (.11>r>−.44, all p>.01), with the exception of significant negative correlations between Labeling and the left IFOF (r=−.5, p<.006), as well as Labeling and the left ILF (r=−.47, p<.006), and Labeling and the left UF (r=−.52, p<.006). Within the HC group, there were no significant correlations between white matter MD in the selected ROIs Matching or Labeling performance (.37>r>−.34, all p>.05). We again compared correlation coefficients between the TBI group and the HC group, focusing on those ROIs that were significantly correlated with performance within the TBI group. However, unlike FA, for MD there were no significant group differences in the strength of correlations.

AD & RD.

For AD, there were no significant correlations between any of the ROIs and Matching or Labeling within the TBI group (.25>r>−.37, all p>.01) or within the HC group (.32>r>−.45, all p>.01). In contrast, for RD, there was a significant negative correlation between Matching and Labeling and the left (Matching: r=−.47, p<.006; Labeling: r=−.53, p<.006) and right IFOF (Matching: r=−.49, p<.006; Labeling: r=−.47, p<.006). Moreover, there were significant negative correlations between Labeling and white matter RD in the left UF (r=−.57, p<.001). Within the HC group, there were no significant correlations between white matter RD in the selected ROIs and Matching or Labeling performance (.34>r>−.28, all p>.05). To follow-up the RD results, we compared correlation coefficients between the TBI group and the HC group, focusing on ROIs that were significantly correlated with performance within the TBI group. However, similar to MD, there were no significant group difference in the strength of correlations with the RD scalar.

To isolate the cognitive process represented by the verbal categorization of the facial features, within the TBI group we further examined whether Labeling was significantly associated with scalar values in any of the ROIs when controlling for Matching scores. The only ROI whose FA remained significantly associated with Labeling was the Left inferior UF (r=.47, p<.006). For MD, no correlation remained significant within the TBI group (all r>−.23, all p>.01), although there was a marginally significant correlation between Labeling and MD in the UF (r=−.46, p=.007). For AD, no correlation remained significant within the TBI group (all r>−.35, all p>.01). Finally, for RD, the only correlation remaining significant within the TBI group was the correlation between Labeling and the UF (r=−.49, p<.006).

In summary, we found that individuals with TBI showed significantly lower white matter integrity, in particular as measured by FA and RD, on several white matter tracts involved in emotion recognition. Moreover, we found several correlations between ROI white matter integrity measured by in particular by FA (but also by RD and MD) and performance on both the Matching and Labeling tasks, with a specific association between Labeling and the UF.

Exploratory analysis - group comparisons

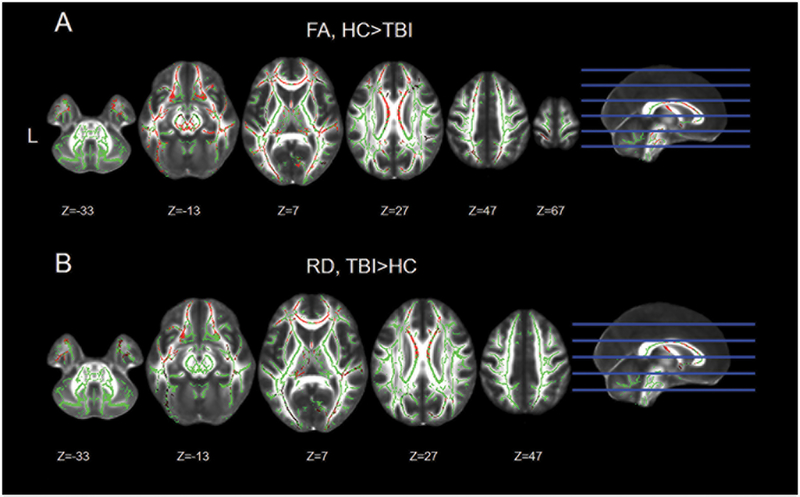

We next carried out an exploratory analysis to further investigate the presence of a relationship between affect recognition behavior and white matter microstructure outside of our preselected ROIs. First, nonparametric whole-brain analyses revealed that individuals with TBI showed significantly lower levels of FA in the frontal, temporal, occipital and parietal lobes. The white-matter tracts that displayed lower FA values within the TBI group included, but were not limited to, the corpus callosum, forceps major and minor, the bilateral IFOF, the bilateral UF, the bilateral superior and IFL, the cingulum and the thalamic radiation. Overall, participants with a history of TBI showed a widespread reduction in FA across the entire white-matter skeleton (Figure 3A, Table S1).

Figure 3. Group comparison for FA and RD.

Significant differences in fractional anisotropy (FA) and radial diffusivity (RD) between the TBI and HC group. The significant voxels (in red) are overlaid on the mean skeleton mask (in green). Images are presented in neurological convention (L=L).

For both MD and AD, there were no significant differences between individuals with TBI and HCs. However, similar to FA, participants with TBI showed widespread higher RD values compared to HCs. The white-matter tracts affected included the corpus callosum, forceps major and minor, the bilateral IFOF, the bilateral UF, the bilateral superior and ILF, the cingulum and the thalamic radiation (Figure 3B, Table S1).

Exploratory analysis – correlational

Interaction analyses.

The purpose of the interaction analysis was to determine the presence of a significant difference in the association between behavior (Matching and Labeling) and white matter integrity within the two groups. For Matching, there was a significant difference in the linear relationship between FA and affect recognition abilities between individuals with TBI and HCs (i.e., a significant interaction), with individuals with TBI showing stronger correlation between Matching performance and FA in several white matter tracts, including forceps major and minor, bilateral IFOF, bilateral ILF and superior longitudinal fasciculus, bilateral UF, thalamic radiation and the bilateral corticospinal tract (Figure S1A, Table S2). There was also a significant interaction for MD, with individuals with TBI showing a stronger linear relationship between Matching and small clusters in the right posterior cingulum, anterior thalamic radiation and IFOF (Figure S1B, Table S2). Similarly, individuals with TBI had a stronger relationship between Matching scores and RD in white matter tracts including forceps major and minor, bilateral IFOF, bilateral ILF and superior longitudinal fasciculus, bilateral UF, thalamic radiation and the bilateral corticospinal tract (Figure S1C, Table S2). There was no significant interaction for AD. For Labeling, there was no significant difference in the linear relationship between FA and affect recognition abilities between individuals with TBI and HCs (i.e., no significant interaction) for any of the scalar values.

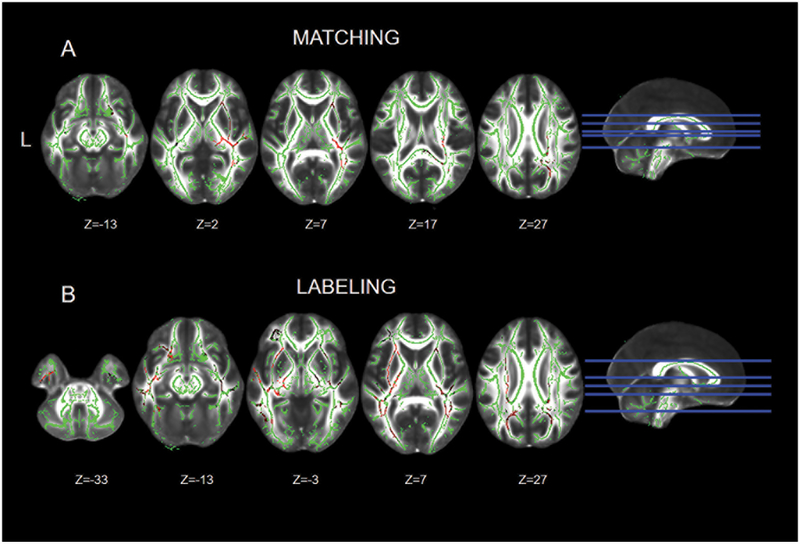

FA-within group analysis.

The purpose of this analysis was to examine the association between white matter integrity and behavior (Matching and Labeling performance) within each group. Within the TBI group, participants with higher Matching abilities had higher FA in several voxels belonging to regions of the right IFOF spanning from the frontal to the occipital lobe. Other clusters of voxels whose FA values positively correlated with Matching abilities included the right corona radiata, the right UF, small parts of the corticospinal tract and the left side of the splenium of the corpus callosum. There was also one cluster of voxels in the temporal part of the left IFOF showing a significant positive correlation with Matching performance (Figure 4A, table S3). Labeling performance significantly and positively correlated with FA values in the bilateral IFOF, the bilateral UF, the bilateral ILF, the bilateral cingulum, and small clusters in the bilateral thalamic radiations and corticospinal tracts (Figure 4B, table S3). Given the lateralized nature of the findings, we examined the number of voxels in each hemisphere for each FA correlational analysis. We found that for Matching 4,718 voxels out of 4881 (96.6%) were located in the right hemisphere, while only 3.3% were in the left hemisphere. For Labeling, on the other hand, 10,319 voxels were located in the left hemisphere (67.2%), while 32.8% were located in the right hemisphere. Within the HC group, after correcting for multiple comparisons there was no significant association between Matching or Labeling and FA.

Figure 4. Significant correlations between matching and labeling performance and FA within the TBI group.

Significant correlations between matching and labeling performance and FA (fractional anisotropy) within the TBI group. Significant voxels are in red (thresholded for t>.95) overlaid on the mean skeleton mask. Images are presented in neurological convention (L=L).

MD-within group analysis.

Within the TBI group, the exploratory analysis revealed no significant association between Matching performance and MD values. However, the same analysis using Labeling as the regressor of interest showing a significant negative correlation with MD values in several clusters located in the forceps minor and major, bilateral IFOF, the left superior longitudinal fasciculus, the bilateral UF, as well as the thalamic radiation (Figure S2, Table S3). Within the HC group, we found no significant association between Matching or Labeling and MD.

AD-within group analysis.

Both in the TBI and HC group there were no significant correlations between Matching and Labeling performance and AD values.

RD-within group analysis.

Within the TBI group, the exploratory analysis revealed a significant negative association between Matching performance and RD values in the left (as well as small clusters of the right) forceps minor, the left anterior cingulum, the left anterior thalamic radiation, and regions of the UF, as well as the right forceps major, and posterior parts of the right IFOF, and the right corticospinal tract (Figure S3, Table S3). However, the same analysis using Labeling as the regressor showed a significant negative correlation with RD values in several clusters, including forceps minor and major, bilateral IFOF, the bilateral superior and ILF, the bilateral UF, the bilateral corticospinal tracts, as well as the thalamic radiation (Figure S3, Table S3). Within the HC group, we found no significant association between Matching or Labeling and RD.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to further characterize the neural mechanisms leading to different patterns of facial affect recognition impairment in TBI, and to determine the white matter correlates of performance on two different types of facial affect recognition tasks: one perceptual (affect matching) and one involving verbal categorization (affect labeling). Our findings revealed a striking lateralization, with perceptual facial affect recognition skills significantly more related to right hemisphere integrity, and interpretative skills related to left hemisphere integrity. These results are partially in line with findings of the only similar study carried out on a TBI population (Genova, et al., 2015), although several novel results emerged.

Individuals with TBI had significantly lower fractional anisotropy (FA) and radial diffusivity (RD) than healthy comparison peers, in widespread regions of the brain and involving several white matter tracts, including tracts that support communication between occipital visual regions and fronto-temporal limbic regions, such as the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF), the uncinate fasciculus (UF), and the inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF). There were no significant group differences for the two other scalar values examined. The lack of a significant difference might be due to the relatively conservative nature of the non-parametric tool employed to test group differences, but it is also possible that mean diffusivity (MD) and axial diffusivity (AD) are not as sensitive as other DTI scalars at detecting microstructural white-matter abnormalities that result from TBI (Cubon, et al., 2011). Nonetheless, our FA and RD results mirror those of several other studies, and confirm the presence of widespread white matter abnormalities even in the chronic stage of TBI (Hulkower, et al., 2013; Kraus, et al., 2007).

We also observed significant correlations between DTI scalars and both perceptual and verbal categorization skills. As previously reported by Genova and colleagues (Genova, et al., 2015), in another sample of individuals with TBI, the white matter tracts involved were the IFOF and the ILF, although in our case the correlations extended to both matching and labeling. Noticeably, the UF also was involved, which was not reported by Genova et al. Perhaps the most interesting result was that while the correlation between FA and matching was mainly limited to right hemisphere regions, the correlation between FA and labeling was not similarly lateralized. This indicates that higher errors in verbal categorization might be associated with higher levels of damage in white matter structure within the left hemisphere, while the damage limited to the right hemisphere might result in problems detecting, but not verbally interpreting, facial affects. While reports of hemispheric asymmetry are common in the literature, in particular a dominance of the right hemisphere in emotion production and processing (Lindell, 2013), the same is also true of language, which is usually left-lateralized in right-handed individuals (Knecht et al., 2000). The higher and more widespread correlations between verbal categorization scores and left hemisphere structures are likely to reflect the stronger reliance of verbal categorization on language. It should be noted, however, that about 33% of voxels correlated with affect labeling task scores were located in the right hemisphere, revealing that labeling accuracy is not exclusively dependent on the left hemisphere but rather involves both the left and right hemispheres. By comparison, when only emotion perception was required, correlational analysis showed an almost exclusive involvement of the right hemisphere.

Findings from whole brain exploratory analyses were also supported by the ROI specific analysis. Although some of the white matter tracts of interest (e.g., IFOF, IFL) showed correlations with both matching and labeling performance, once matching was used as a covariate to determine which tracts showed a specific relationship with verbal categorization skills, the only significant tract was the left UF. The UF connects the temporal and the prefrontal region, and thus is the only ROI not implicated in carrying visual information to higher-level affective processing regions (Kier, Staib, Davis, & Bronen, 2004; Von Der Heide, Skipper, Klobusicky, & Olson, 2013).

Our results are consistent with a theoretical model that separates affect recognition into two stages: perception and verbal categorization; moreover, the results provide original evidence of differential white-matter correlates of these two stages following TBI, with accuracy on perceptual processes linked to integrity of mainly right-hemisphere white matter tracts connecting occipital and frontal regions, and accuracy on language-related semantic processes linked to integrity of left-hemisphere tracts connecting temporal and occipital areas (Palermo, et al., 2013).

Although these patterns of correlations were not fully replicated for the other scalars, FA might be more sensitive to detect the type of axonal damage that results from TBI. While FA is very sensitive to white matter neuropathology, it is also a fairly non-specific biomarker, and thus likely to capture a wider range of microstructural anomalies (Alexander, et al., 2007). As noted earlier, our results partially align with Genova and colleagues’ (2015) findings in highlighting the importance of the IFOF and the IFL in facial affect recognition after TBI. However, our additional findings (e.g., hemispheric lateralization and the role of the UF) are likely to be due to either the affect recognition tasks used in the current study, which were specifically selected to avoid ceiling effect and detect individual differences within a TBI sample; or the fact that a larger number of DTI directions were collected (Genova, et al., 2015; Palermo, et al., 2013). It is interesting that significant correlational findings were limited to the TBI group, while no correlations were found within the HC group. Indeed, the interaction analyses for the matching task revealed that for both FA and RD (and, to a lesser degree, MD), there was a significantly stronger association between behavioral performance and white matter structure within the TBI group. This might be due to methodological issues, and in particular to the fact that HC group variance was much lower than that of the TBI group, and that, coupled with the fact that factors that might explain such variance were added as covariates (age and sex in particular) might have led to null findings within the HC group.

Overall, our findings reveal that the use of neuroimaging and behavioral assessment tools that are designed to detect microstructural individual differences at the neurobiological level, as well as fine-grained individual differences at the behavioral level, can help uncover the mechanisms and neural underpinnings of different patterns of facial affect recognition impairment following TBI.

Conclusions

The results of our study provide neurobiological evidence that distinct neural systems underlie perception vs. verbal categorization of facial affect in adults with TBI. While perceptual accuracy relied on integrity of mainly right-hemisphere white-matter tracts connecting occipital and frontal regions, verbal categorization accuracy was associated with integrity of left-hemisphere tracts connecting temporal and occipital areas. This information furthers our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying facial affect recognition impairments in adults with TBI.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1 Interaction analyses: group differences in linear relationship between Matching and DTI scalars Significant group differences in the linear relationship between DTI scalars and matching performance for fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), and radial diffusivity (RD). Significant voxels are in red (thresholded for p<.05) overlaid on the mean skeleton mask. Images are presented in neurological convention (L=L).

Figure S2 Correlation between labeling performance and MD within the TBI group Correlation between labeling performance and MD (mean diffusivity) within the TBI group. Significant voxels are in red (thresholded for t>.95) overlaid on the mean skeleton mask. Images are presented in neurological convention (L=L).

Figure S3 Correlation between behavioral performance and RD within the TBI group Correlation between matching (A) and labeling (B) performance and RD (radial diffusivity) within the TBI group. Significant voxels are in red (thresholded for t>.95) overlaid on the mean skeleton mask. Images are presented in neurological convention (L=L).

Acknowledgments

The current work was supported by the by NICHD/NCMRR grant R01 HD071089, by an American Psychological Foundation Benton-Meier Fellowship, and by a pilot grant issued by the University of Iowa Magnetic Resonance Research Facility.

References

- Adams JH, Doyle D, Graham DI, Lawrence AE, & McLellan DR (1984). Diffuse axonal injury in head injuries caused by a fall. Lancet, 2(8417–8418), pp. 1420–1422. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6151042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JH, Graham DI, & Jennett B (2001). The structural basis of moderate disability after traumatic brain damage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 71(4), pp. 521–524. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11561038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander AL, Lee JE, Lazar M, & Field AS (2007). Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain. Neurotherapeutics, 4(3), pp. 316–329. doi:10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.011 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.011http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17599699 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17599699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JLR, Jenkinson M, & Smith S (2007a). Non-linear optimisation. FMRIB technical report TR07JA1. Retrieved Date from www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/analysis/techrep. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JLR, Jenkinson M, & Smith S (2007b). Non-linear registration, aka Spatial normalisation FMRIB technical report TR07JA2. Retrieved from www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/analysis/techrep

- Andrews TK, Rose FD, & Johnson DA (1998). Social and behavioural effects of traumatic brain injury in children. Brain Inj, 12(2), pp. 133–138. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9492960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbage DR, Yim J, Zupan B, Neumann D, Tomita MR, & Willer B (2011). Meta-analysis of facial affect recognition difficulties after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology, 25(3), pp. 277–285. doi:10.1037/a0021908 Retrieved from 10.1037/a0021908http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21463043 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21463043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SA, Kroenke CD, Sherman LS, Lawrence G, Gong X, Taber EN, … Montine TJ (2011). White matter lesions defined by diffusion tensor imaging in older adults. Ann Neurol, 70(3), pp. 465–476. doi:10.1002/ana.22484 Retrieved from 10.1002/ana.22484http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21905080 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21905080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser PJ (1995). Inferring microstructural features and the physiological state of tissues from diffusion-weighted images. NMR Biomed, 8(7–8), pp. 333–344. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8739270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu C (2002). The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system - a technical review. NMR Biomed, 15(7–8), pp. 435–455. doi:10.1002/nbm.782 Retrieved from 10.1002/nbm.782http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12489094 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12489094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Nunes RG, Clare S, … Smith SM (2003). Characterization and propagation of uncertainty in diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Magn Reson Med, 50(5), pp. 1077–1088. doi:10.1002/mrm.10609 Retrieved from 10.1002/mrm.10609http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14587019 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14587019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett IJ, Madden DJ, Vaidya CJ, Howard DV, & Howard JH Jr. (2010). Age-related differences in multiple measures of white matter integrity: A diffusion tensor imaging study of healthy aging. Hum Brain Mapp, 31(3), pp. 378–390. doi:10.1002/hbm.20872 Retrieved from 10.1002/hbm.20872http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19662658 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19662658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catani M, Piccirilli M, Cherubini A, Tarducci R, Sciarma T, Gobbi G, … Mecocci P (2003). Axonal injury within language network in primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol, 53(2), pp. 242–247. doi:10.1002/ana.10445 Retrieved from 10.1002/ana.10445http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12557292 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12557292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubon VA, Putukian M, Boyer C, & Dettwiler A (2011). A diffusion tensor imaging study on the white matter skeleton in individuals with sports-related concussion. J Neurotrauma, 28(2), pp. 189–201. doi:10.1089/neu.2010.1430 Retrieved from 10.1089/neu.2010.1430http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21083414 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21083414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff MC, Mutlu B, Byom L, & Turkstra LS (2012). Beyond utterances: distributed cognition as a framework for studying discourse in adults with acquired brain injury. Semin Speech Lang, 33(1), pp. 44–54. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1301162 Retrieved from 10.1055/s-0031-1301162http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22362323 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22362323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetz M (2004). The neurophysiology of brain injury. Clin Neurophysiol, 115(1), pp. 4–18. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14706464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genova HM, Rajagopalan V, Chiaravalloti N, Binder A, Deluca J, & Lengenfelder J (2015). Facial affect recognition linked to damage in specific white matter tracts in traumatic brain injury. Soc Neurosci, 10(1), pp. 27–34. doi:10.1080/17470919.2014.959618 Retrieved from 10.1080/17470919.2014.959618http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25223759 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25223759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germine LT, & Hooker CI (2011). Face emotion recognition is related to individual differences in psychosis-proneness. Psychol Med, 41(5), pp. 937–947. doi:10.1017/S0033291710001571 Retrieved from 10.1017/S0033291710001571http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20810004 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20810004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Hernandez R, Max JE, Kosier T, Paradiso S, & Robinson RG (1997). Social impairment and depression after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 78(12), pp. 1321–1326. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9421985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieve SM, Williams LM, Paul RH, Clark CR, & Gordon E (2007). Cognitive aging, executive function, and fractional anisotropy: a diffusion tensor MR imaging study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 28(2), pp. 226–235. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17296985 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Bookheimer SY, & Mazziotta JC (2000). Modulating emotional responses: effects of a neocortical network on the limbic system. [Clinical Trial [DOI] [PubMed]

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t

- Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Neuroreport, 11(1), pp. 43–48. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10683827 [Google Scholar]

- Hua K, Zhang J, Wakana S, Jiang H, Li X, Reich DS, … Mori S (2008). Tract probability maps in stereotaxic spaces: analyses of white matter anatomy and tract-specific quantification. Neuroimage, 39(1), pp. 336–347. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.053 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.053http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17931890 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17931890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulkower MB, Poliak DB, Rosenbaum SB, Zimmerman ME, & Lipton ML (2013). A decade of DTI in traumatic brain injury: 10 years and 100 articles later. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 34(11), pp. 2064–2074. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A3395 Retrieved from 10.3174/ajnr.A3395http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23306011 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23306011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingalhalikar M, Smith A, Parker D, Satterthwaite TD, Elliott MA, Ruparel K, … Verma R (2014). Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 111(2), pp. 823–828. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316909110 Retrieved from 10.1073/pnas.1316909110http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24297904 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24297904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MR, Wozniak JR, Muetzel RL, Mueller BA, Chiou HH, Pantekoek K, & Lim KO (2009). White matter and neurocognitive changes in adults with chronic traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 15(1), pp. 130–136. doi:10.1017/S1355617708090024 Retrieved from 10.1017/S1355617708090024http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19128536 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19128536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr SL, & Neale JM (1993). Emotion perception in schizophrenia: specific deficit or further evidence of generalized poor performance? J Abnorm Psychol, 102(2), pp. 312–318. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8315144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels RP, Montagne B, Hendriks AW, Perrett DI, & de Haan EH (2014). Assessment of perception of morphed facial expressions using the Emotion Recognition Task: normative data from healthy participants aged 8–75. J Neuropsychol, 8(1), pp. 75–93. doi:10.1111/jnp.12009 Retrieved from 10.1111/jnp.12009http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23409767 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23409767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kier EL, Staib LH, Davis LM, & Bronen RA (2004). MR imaging of the temporal stem: anatomic dissection tractography of the uncinate fasciculus, inferior occipitofrontal fasciculus, and Meyer’s loop of the optic radiation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 25(5), pp. 677–691. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15140705 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen KM, Greenwood R, Powell JH, Leech R, Hawkins PC, Bonnelle V, … Sharp DJ (2011). White matter damage and cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury. Brain, 134(Pt 2), pp. 449–463. doi:10.1093/brain/awq347 Retrieved from 10.1093/brain/awq347http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21193486 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21193486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht S, Deppe M, Drager B, Bobe L, Lohmann H, Ringelstein E, & Henningsen H (2000). Language lateralization in healthy right-handers. Brain, 123 (Pt 1), pp. 74–81. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10611122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox L, & Douglas J (2009). Long-term ability to interpret facial expression after traumatic brain injury and its relation to social integration. Brain Cogn, 69(2), pp. 442–449. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2008.09.009 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.09.009http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18951674 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18951674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus MF, Susmaras T, Caughlin BP, Walker CJ, Sweeney JA, & Little DM (2007). White matter integrity and cognition in chronic traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Brain, 130(Pt 10), pp. 2508–2519. doi:10.1093/brain/awm216 Retrieved from 10.1093/brain/awm216http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17872928 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17872928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Husain M, Gupta RK, Hasan KM, Haris M, Agarwal AK, … Narayana PA (2009). Serial changes in the white matter diffusion tensor imaging metrics in moderate traumatic brain injury and correlation with neuro-cognitive function. J Neurotrauma, 26(4), pp. 481–495. doi:10.1089/neu.2008.0461 Retrieved from 10.1089/neu.2008.0461http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19196176 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19196176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindell AK (2013). Continuities in emotion lateralization in human and non-human primates. Front Hum Neurosci, 7, p 464. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00464 Retrieved from 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00464http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23964230 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23964230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malec JF, Brown AW, Leibson CL, Flaada JT, Mandrekar JN, Diehl NN, & Perkins PK (2007). The mayo classification system for traumatic brain injury severity. J Neurotrauma, 24(9), pp. 1417–1424. doi:10.1089/neu.2006.0245 Retrieved from 10.1089/neu.2006.0245https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17892404 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17892404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino J, Brogna C, Robles SG, Vergani F, & Duffau H (2010). Anatomic dissection of the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus revisited in the lights of brain stimulation data. Cortex, 46(5), pp. 691–699. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2009.07.015 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.07.015http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19775684 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19775684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin NC, Paul RH, Grieve SM, Williams LM, Laidlaw D, DiCarlo M, … Gordon E (2007). Diffusion tensor imaging of the corpus callosum: a cross-sectional study across the lifespan. Int J Dev Neurosci, 25(4), pp. 215–221. doi:10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.03.008 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.03.008http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17524591 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17524591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milders M, Fuchs S, & Crawford JR (2003). Neuropsychological impairments and changes in emotional and social behaviour following severe traumatic brain injury. [Comparative Study [DOI] [PubMed]

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol, 25(2), pp. 157–172. doi:10.1076/jcen.25.2.157.13642 Retrieved from 10.1076/jcen.25.2.157.13642http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12754675 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12754675 [Google Scholar]

- Morton MV, & Wehman P (1995). Psychosocial and emotional sequelae of individuals with traumatic brain injury: a literature review and recommendations. Brain Inj, 9(1), pp. 81–92. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7874099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann D, McDonald BC, West J, Keiski MA, & Wang Y (2015). Neurobiological mechanisms associated with facial affect recognition deficits after traumatic brain injury. Brain Imaging Behav doi:10.1007/s11682-015-9415-3 Retrieved from 10.1007/s11682-015-9415-3http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26040980 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26040980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo R, O’Connor KB, Davis JM, Irons J, & McKone E (2013). New tests to measure individual differences in matching and labelling facial expressions of emotion, and their association with ability to recognise vocal emotions and facial identity. PLoS One, 8(6), p e68126. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068126 Retrieved from 10.1371/journal.pone.0068126http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23840821 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23840821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen L (1991). Sensitivity to emotional cues and social behavior in children and adolescents after head injury. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Percept Mot Skills, 73(3 Pt 2), pp. 1139–1150. doi:10.2466/pms.1991.73.3f.1139 Retrieved from 10.2466/pms.1991.73.3f.1139http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1805169 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1805169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippi CL, Mehta S, Grabowski T, Adolphs R, & Rudrauf D (2009). Damage to association fiber tracts impairs recognition of the facial expression of emotion. J Neurosci, 29(48), pp. 15089–15099. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0796-09.2009 Retrieved from 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0796-09.2009http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19955360 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19955360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Schlaggar BL, & Petersen SE (2014). Studying brain organization via spontaneous fMRI signal. Neuron, 84(4), pp. 681–696. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.007 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.007https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25459408 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25459408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine AM, Adluru N, Alexander AL, Christian BT, Okonkwo OC, Oh J, … Johnson SC (2014). Associations between white matter microstructure and amyloid burden in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: A multimodal imaging investigation. Neuroimage Clin, 4, pp. 604–614. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2014.02.001 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.02.001http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24936411 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24936411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigon A, Turkstra L, Mutlu B, & Duff M (2016a). The female advantage: sex as a possible protective factor against emotion recognition impairment following traumatic brain injury. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci, 16(5), pp. 866–875. doi:10.3758/s13415-016-0437-0 Retrieved from 10.3758/s13415-016-0437-0http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27245826 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27245826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigon A, Turkstra L, Mutlu B, & Duff M (2016b). The female advantage: sex as a possible protective factor against emotion recognition impairment following traumatic brain injury. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci doi:10.3758/s13415-016-0437-0 Retrieved from 10.3758/s13415-016-0437-0http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27245826 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27245826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigon A, Turkstra L, Mutlu B, & Duff M (In press). Facial-affect recognition deficit as a predictor of different aspects of social communication impairment in traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigon A, Voss MW, Turkstra LS, Mutlu B, & Duff MC (2016). Frontal and Temporal Structural Connectivity Is Associated with Social Communication Impairment Following Traumatic Brain Injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 22(7), pp. 705–716. doi:10.1017/S1355617716000539 Retrieved from 10.1017/S1355617716000539http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27405965 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27405965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigon A, Voss MW, Turkstra LS, Mutlu B, & Duff MC (2017). Relationship between individual differences in functional connectivity and facial-emotion recognition abilities in adults with traumatic brain injury. Neuroimage Clin, 13, pp. 370–377. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2016.12.010 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.12.010http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28123948 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28123948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg H, Dethier M, Kessels RP, Westbrook RF, & McDonald S (2015). Emotion perception after moderate-severe traumatic brain injury: The valence effect and the role of working memory, processing speed, and nonverbal reasoning. Neuropsychology, 29(4), pp. 509–521. doi:10.1037/neu0000171 Retrieved from 10.1037/neu0000171http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25643220 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25643220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg H, McDonald S, Dethier M, Kessels RP, & Westbrook RF (2014). Facial emotion recognition deficits following moderate-severe Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): re-examining the valence effect and the role of emotion intensity. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 20(10), pp. 994–1003. doi:10.1017/S1355617714000940 Retrieved from 10.1017/S1355617714000940http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25396693 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25396693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan NP, Catroppa C, Beare R, Silk TJ, Hearps SJ, Beauchamp MH, … Anderson VA (2017). Uncovering the Neuroanatomical Correlates of Cognitive, Affective, and Conative Theory of Mind in Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: A Neural Systems Perspective. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci doi:10.1093/scan/nsx066 Retrieved from 10.1093/scan/nsx066http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28505355 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28505355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan NP, Genc S, Beauchamp MH, Yeates KO, Hearps S, Catroppa C, … Silk TJ (2017). White matter microstructure predicts longitudinal social cognitive outcomes after paediatric traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychol Med, pp. 1–13. doi:10.1017/S0033291717002057 Retrieved from 10.1017/S0033291717002057http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28780927 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28780927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat DH, Tuch DS, Greve DN, van der Kouwe AJ, Hevelone ND, Zaleta AK, … Dale AM (2005). Age-related alterations in white matter microstructure measured by diffusion tensor imaging. Neurobiol Aging, 26(8), pp. 1215–1227. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.017 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.017http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15917106 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15917106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen PN, & Basser PJ (2005). A model for diffusion in white matter in the brain. Biophys J, 89(5), pp. 2927–2938. doi:10.1529/biophysj.105.063016 Retrieved from 10.1529/biophysj.105.063016http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16100258 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16100258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp DJ, Beckmann CF, Greenwood R, Kinnunen KM, Bonnelle V, De Boissezon X, … Leech R (2011). Default mode network functional and structural connectivity after traumatic brain injury. Brain, 134(Pt 8), pp. 2233–2247. doi:10.1093/brain/awr175 Retrieved from 10.1093/brain/awr175http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21841202 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21841202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shewan CM, & Kertesz A (1980). Reliability and validity characteristics of the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB). J Speech Hear Disord, 45(3), pp. 308–324. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7412225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM (2002). Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp, 17(3), pp. 143–155. doi:10.1002/hbm.10062 Retrieved from 10.1002/hbm.10062http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12391568 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12391568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, … Behrens TE (2006). Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage, 31(4), pp. 1487–1505. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16624579 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16624579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, … Matthews PM (2004). Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage, 23 Suppl 1, pp. S208–219. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15501092 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15501092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamiya Y, & Hiraki K (2013). Individual differences in the recognition of facial expressions: an event-related potentials study. PLoS One, 8(2), p e57325. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057325 Retrieved from 10.1371/journal.pone.0057325http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23451205 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23451205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temkin NR, Corrigan JD, Dikmen SS, & Machamer J (2009). Social functioning after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil, 24(6), pp. 460–467. doi:10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181c13413 Retrieved from 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181c13413https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19940679 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19940679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Der Heide RJ, Skipper LM, Klobusicky E, & Olson IR (2013). Dissecting the uncinate fasciculus: disorders, controversies and a hypothesis. Brain, 136(Pt 6), pp. 1692–1707. doi:10.1093/brain/awt094 Retrieved from 10.1093/brain/awt094http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23649697 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23649697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakana S, Caprihan A, Panzenboeck MM, Fallon JH, Perry M, Gollub RL, … Mori S (2007). Reproducibility of quantitative tractography methods applied to cerebral white matter. Neuroimage, 36(3), pp. 630–644. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.049 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.049http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17481925 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17481925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]