Abstract

Over the last two decades, it has become increasingly apparent that Wnt signaling plays a critical role in development and adult tissue homeostasis in multiple organs and in the pathogenesis of many diseases. In particular, a crucial role for Wnt signaling in bone development and bone tissue homeostasis has been well recognized. Numerous genome-wide association studies (GWASs) confirmed the importance of Wnt signaling in controlling bone mass. Moreover, ample evidence suggests that Wnt signaling is essential for kidney, intestine, and adipose tissue development and homeostasis. Recent emerging evidence demonstrates that Wnt signaling may play a fundamental role in the aging process of those organs. New discoveries show that bone is not only the major reservoir for calcium and phosphate storage, but also the largest organ with multiple functions, including mineral and energy metabolism. The interactions among bone, kidney, intestine, and adipose tissue are controlled and regulated by several endocrine signals, including FGF23, klotho, sclerostin (SOST), osteocalcin, vitamin D, and leptin. Since the aging process is characterized by structural and functional decline in almost all tissues and organs, understanding the Wnt signaling–related interactions among bone, kidney, intestine, and adipose tissue in aging may shed light on the pathogenesis of age-related diseases.

Keywords: Wnt/β-catenin signaling, bone, FGF23-klotho, sclerostin, aging

Graphical abstract

Wnt signaling plays a crucial role in the development and homeostasis of bone tissue, as well as kidney, intestine, and adipose tissue, and it may play a fundamental role in the aging process of those organs. This review discusses recent progress in understanding the role of Wnt signaling in aging bone and other organs and tissues, with an emphasis on the interaction between inter-organ regulation and aging bone.

Introduction

Wnt signaling is one of a handful of highly conserved signaling pathways that play crucial roles in multiple aspects of embryonic development and adult homeostasis throughout the animal kingdom.Wnt signaling is initiated by Wnt ligands (Wnts).Wnts are evolutionarily conserved secreted cysteine-rich glycoproteins, and there are 19 genes that encode Wnts in the mouse and human genomes. Wnts can activate several intracellular signaling pathways, including the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway and non-canonical Wnt pathways.The non-canonical Wnt pathways include the Wnt/planar cell polarity (PCP) and Wnt/Ca2+ pathways as well as the β-catenin-independent Wnt/LRP6 pathways, related to Wnt/stabilization of proteins (STOP) signaling and Wnt/target of rapamycin(TOR) signaling.1,2The canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling is evolutionarily highly conserved and is the best understood pathway. We will therefore focus on Wnt/β-catenin signaling in this review article.

The key element in the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway is the regulation of protein stability of β-catenin, which acts as a transcription co-factor.β-catenin has dual functions and is also involved in cell adhesion by forming a stable complex with the cell adhesion molecules of the cadherin family. In the absence of Wnt ligands, cytosolic β-catenin interacts with other components of the destruction complex, including Axin1, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), casein kinase-1 (CK1), protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), and the E3-ubiquitin ligase β-transducin repeat containing protein (β-TrCP).2 Axin1 is a central scaffold protein of the destruction complex and directly interacts with all other core components of the destruction complex, such as APC, GSK-3, CK1, and β-catenin. It has been reported that Axin1 is the rate-limiting factor of the β-catenin destruction complex.3 β-catenin is phosphorylated by two kinases of the destruction complex, GSK-3 and CK1.The destruction complex creates a β-TrCP recognition site on β-catenin. After phosphorylation and ubiquitination, β-catenin is degraded by the proteasome. When Wnt ligands bind to their coreceptors Frizzled (FZD) and low-density lipoprotein-receptor-related protein-5 or −6 (LRP5/6), the destruction complex is dissociated through phosphorylation of LRP5/6, which then binds Axin1. β-catenin, released from the destruction complex can enter the nucleus, where it binds to the transcription factors LEF/TCF and activates downstream target genes.4

Considering the pivotal role of Wnt signaling in embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis, it is not surprising that the signaling is tightly controlled. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is regulated at many levels by a number of conserved inhibitors and activators. Several extracellular Wnt inhibitors are able to directly bind to Wnt ligands, such as secreted Frizzed-related proteins (sFRPs),5 Wnt inhibitory factor (WIF),6 and klotho.7 Other Wnt inhibitors include proteins of the Dickkopf (DKK),8,9 and the sclerostin (SOST) family members.10 These Wnt antagonists block Wnt signaling through interaction with membrane-associated LRP5/6.11 Adenomatosis polyposis down-regulated 1 (APCDD1) is a membrane-bound glycoprotein that inhibits Wnt signaling by binding to both Wnt and LRP.12 Conversely, the Wnt activators Norrin and R-spondins (Rspo) enhance the signal strength of canonical Wnt signaling by binding to Wnt receptors13 or releasing a Wnt-inhibitory step.14 Recently, two highly homologous Wnt target genes, zinc and ring finger 3 (ZNRF3) and ring finger protein 43 (RNF43) were identified as potent negative-feedback regulators of Wnt signaling.15,16

Population aging is a public health problem throughout the developed world. By 2030, the population aged 65 and over is projected to be 72 million, accounting for approximately 20% of the United States population. Aging is characterized by progressive decline in tissue and organ function and increased risk of mortality, but its causes remain one of the central challenges of biology and medicine. Although there is no single mechanistic description of organ aging, due to the complex nature of the aging process, common hallmarks of aging have been proposed,17 including systemic inflammation, macromolecular damage leading to genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alteration, loss of proteostasis, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication. The aging process is characterized by structural and functional changes affecting almost all tissues and organs. A defined feature of the process of aging is the decline in regenerative capacity associated with reduced adult stem cell function. Despite the role of Wnt signaling, which has been intensively studied in the development and cancer, relatively few studies have looked at the function of Wnt signaling pathways during aging. Due to the critical roles that Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays in development and tissue homeostasis, mutations of the Wnt signaling pathway components could lead to severe diseases, such as many hereditary disorders, osteoporosis, diabetes and cancer.4 The dysregulation of Wnt signaling has also been implicated in fibrosis18, chronic kidney disease (CKD),19 and in age-related neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson disease20 and Alzheimer disease21.

A number of studies suggest that Wnt signaling has positive effects on health during aging, delaying the aged phenotype.22 However, Wnt signaling is augmented in a mouse model of accelerated aging,8 and inhibition of Wnt pathway signaling reverses the aging-associated impairment of skeletal muscle regeneration.23 These contradictory results indicate that the role of Wnt signaling in aging may change with age in different organs, as we explore further below. Since aging is a major risk factor for most late-onset diseases, such as osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, intervertebral disc degeneration, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer,17 a greater understanding of the relationship between aging and Wnt signaling would be valuable to prevent or delay aging-related diseases. In this review, we will discuss recent progress in understanding the role of Wnt signaling in aging bone and other organs and tissues, with an emphasis on the interaction between inter-organ regulation and aging bone.

Wnt signaling in aging bones

Genetic evidence from both humans and mice indicates that Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays crucial roles in controlling multiple aspects of bone development and homeostasis. The adult skeleton contains three major cell types: osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes. Osteoblasts are differentiated from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), whereas osteoclasts are derived from hematopoietic progenitor cells. Osteoblasts form bone, while osteoclasts resorb bone. Osteocytes, terminally differentiated osteoblasts, maintain bone and contribute to the regulation of osteoblasts and osteoclasts during bone modeling and remodeling.1

Wnt signaling has crucial roles in regulating osteoblast differentiation. Lack of β-catenin in mesenchymal progenitor cells inhibits osteoblast differentiation, suggesting that Wnt signaling is essential for early osteoblast specification. Wnt signaling is also involved in the regulation of bone homeostasis.24,25 Deletion of both Lrp5 and Lrp6 in mouse mesenchymal progenitors results in loss of osteoblasts.26 In human, loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in LRP5 cause osteoporosis pseudoglima syndrome (OPPG),27 a form of juvenile-onset osteoporosis. In contrast, gain-of-function autosomal-dominant mutations of LRP5 lead to high bone mass and enhanced bone strength.28–31 Loss-of-function mutations in LRP6 lead to coronary artery disease associated with osteoporosis, an autosomal-dominant familial disease.32 In addition, loss-of-function or loss-of-expression mutations in sclerostin (SOST), the secreted Wnt/β-catenin signaling antagonist, cause high bone mass in sclerosteosis and Van Buchem disease.33–35 Notably, the high bone mass mutations in LRP5 decrease the binding of SOST and dickkopf1 (DKK1), another WNT inhibitor.28,31,36–37 Furthermore, mice with a global deficiency of Lrp538 exhibit postnatal low bone mass, and Lrp6 haploinsufficiency further decreases bone mass in Lrp5-null mice.39 In contrast, mice with the gain-of-function mutations in Lrp5 in osteoblasts display a high bone mass phenotype.40,41 Mouse models with deletion of the Wnt antagonists Dkk1 and SOST show high bone mass. Both our Axin2 KO42 and Axin1 conditional KO mice (unpublished data) show a high bone mass phenotype. Thus, there is ample evidence showing that Wnt signaling plays crucial roles in postnatal bone formation.

Analysis of Lrp5 mutant mice revealed that these mice have reduced osteoblast numbers and activity without obvious changes in osteoclast formation.38,40,41 Surprisingly, activation or deletion of β-catenin in mature osteoblasts or Col2-expressing progenitor cells results in decreased or increased osteoclast numbers and bone resorption,43–46 failing to recapitulate the phenotypes of Lrp5 mutant mice. Thus, how LRP5 regulates bone mass is currently unclear.1,47

Osteocytes are terminally differentiated cells of the osteoblast lineage. They make up 90–95% of all bone cells within the matrix or on bone surfaces. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that osteocytes are master regulators of bone homeostasis by controlling osteoblast and osteoclast activity through sclerostin and receptor-activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL). Deletion of β-catenin in osteocytes increases osteoclast activity and bone resorption, without changes in bone formation45. However, it has been reported that constitutive activation of β-catenin in osteocytes increases both osteoblasts and osteoclasts, leading to increased bone mass.48 Also, osteocytes are the principal sensors for mechanical loading of bone. Several reports have revealed that Wnt signaling plays an essential role in osteocytes for sensing changes in mechanical loading. Deletion of a single allele of β-catenin in osteocytes has been shown to abrogate the anabolic response to mechanical loading.49 Deletion of sclerostin protects mice from mechanical unloading-induced bone loss.50 In Lrp5–/– mice, mechanoresponsiveness is dramatically reduced.51 Furthermore, osteocytes are the major source of the Wnt inhibitor sclerostin52 and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23).53

It has been reported that Wnt signaling is significantly downregulated in the bones of aged women.54 Recent GWASs of age-related osteoporosis suggest that LRP5, DKK1, SOST and other Wnt pathway components contribute to the development of osteoporosis.55 A GWAS of individuals of European descent has shown that nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms in LRP4 and SOST are associated with bone mineral density (BMD).56,57 Wnt16 and Wnt4 have been identified as BMD and fracture risk–associated genes.58,59 Mice with a deletion of Wnt16 in osteoblasts showed increased fracture susceptibility.60 Also, osteoblast-derived WNT16 has been revealed to inhibit osteoclast formation by inhibiting RANK signals.60 Furthermore, the transgenic mice expressing WNT4 in osteoblasts have been shown to promote bone formation and inhibit osteoclast formation and inflammation.61 Other Wnt signaling members, such as WNT10b, SFRP1, SFRP4 and CTNNB1 (encoding for β-catenin) have been identified as osteoporosis susceptibility candidate genes.62,63 Secreted frizzled related protein 4 (SFRP4) is a soluble Wnt antagonist that binds Wnt ligands and thus regulates both canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling. Deletion of Sfrp4 in mice increased amounts of the trabecular bone, but lead to thinning of cortical bone.64 The largest meta-analysis on lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD, including 17 GWASs and over 30,000 individuals of European and Asian ancestry, confirmed the association of LRP4, LRP5, SOST and MEF2C (myocyte enhancer factor 2C) with BMD.65 This convergence of multiple analyses of very large cohorts of human populations of different genetic backgrounds strongly suggests that Wnt signaling may indeed be the most dominant regulator of bone mass in humans. Importantly, an antibody targeting SOST has yielded encouraging results in clinical trials.66 Taken together, mounting evidence suggests that Wnt signaling plays crucial roles in aging bones.

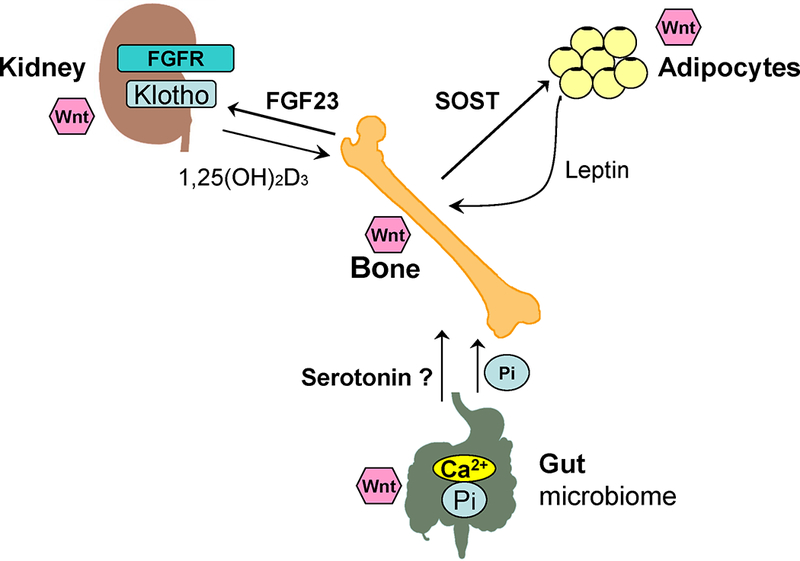

Bone plays important functions in the body, including structural support for the mechanical action of soft tissues, such as the contraction of muscles and the expansion of lungs; support and protection of soft tissues; harboring of bone marrow; and calcium and phosphate storage.67 Indeed, more than 99% of calcium in the body is stored in the bone as hydroxyapatite, which provides skeletal strength and is a source of calcium for the multiple calcium-mediated functions. Also, over 85% of the total body phosphate is stored in bone in both mineralized matrix and exchangeable pools.68 Bone is the major site for the long-term storage and short-term buffering of calcium and phosphate. Outside of the bone, the kidney and intestine are the two main organs that regulate calcium and phosphate homeostasis in the body.69 Importantly, new discoveries demonstrate that bone is also an endocrine organ. Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) is an endocrine hormone secreted by osteocytes and osteoblasts that regulates serum phosphate levels.69 Osteocalcin is another endocrine hormone produced by osteoblasts that plays a major role in energy homeostasis and glucose metabolism.70 Recently, sclerostin (SOST) produced by osteocytes and osteoblasts has emerged as an endocrine factor that regulates glucose and fat metabolism (Fig. 1).71

Figure 1.

Interactions among bone, kidney, intestine, and adipose tissue are controlled and regulated by endocrine signals. Wnt signaling may play a fundamental role in the aging of those organs as well. Bone is not only the major reservoir for calcium and phosphate storage, but also the largest organ with multiple functions, including mineral and energy metabolism. FGF23, klotho, SOST, osteocalcin, vitamin D, and leptin play crucial roles in coordinating and regulating the interactions among bone, kidney, intestine, and adipose tissue.

Wnt signaling in the aging kidney

Wnt signaling has an essential role in kidney development as well as homeostasis and injury repair. Wnt signaling is a crucial regulator of kidney morphogenesis. Kidney development is dependent upon the interaction of three main cell types: the ureteric epithelium, the metanephric mesenchyme, and the renal stroma. Wnt signaling plays essential roles in ureteric epithelia branch morphogenesis.72 Wnt signaling also plays a role in the induction of the condensed mesenchyme.73,74 It has been demonstrated that the tight control of β-catenin activity is essential for balancing self-renewal of the nephrogenic progenitors and induction of nephrogenesis.75,76 Several studies shown that Wnt signaling also plays essential roles in the renal stroma.77–79 Taken together, Wnt signaling is a central player in kidney development.

Although Wnt signaling has an essential role in kidney development, its activity is relatively low in adult kidney.80 However, Wnt signaling is upregulated in virtually every experimental animal model ranging from acute kidney injury (AKI) to various forms of chronic kidney disease (CKD), suggesting that Wnt signaling may have a crucial role in the subsequent repair or disease development after a wide variety of injuries in the adult kidney.81 Although adult mammalian kidney has been regarded as a static organ with limited cellular turnover and regenerative capacity,82 Wnt-responsive stem cells have been identified in adult kidney.83 It has been reported that Wnt signaling is increased in aged kidney.84 And Wnt signaling increases in the kidney in accelerated aging models.85 Patients with CKD have a common premature aging phenotype, including hypogonadism, skin atrophy, osteopenia, and cognitive impairment.86 Importantly, Wnt signaling is up-regulated in all animal models of CKD and human kidney disorders.87 This suggests that Wnt signaling may play an essential role in kidney aging that may be shared with CKD. As described above, bone not only functions as a frame for muscle attachment for the purpose of locomotion, it is also the major storage site for minerals in the body, such as calcium and phosphate. Recently, bone has been identified as an active endocrine organ that communicates with other organs involved in mineral and energy metabolism.88

Klotho is an antiaging gene encoding a single-pass transmembrane protein that forms a complex with multiple FGF receptors and functions as a co-receptor for FGF23. Klotho mutant mice display an extremely shortened life span with multiple disorders resembling human aging, including hypogonadism, growth retardation, osteoporosis, skin atrophy, vascular calcification, accelerated thymic involution, hearing loss, and auditory syndromes.89 In contrast, transgenic mice that overexpress klotho have a 20–30% increase in life span.90 Emerging evidence reveals that klotho deficiency is an early biomarker for CKD, and replacement of soluble klotho or forced overexpression of klotho protects the kidney from renal injuries.91 Klotho is expressed mainly in the kidney and parathyroid gland. Since the phenotype of mice with a kidney-specific ablation of klotho recapitulates the phenotype of global klotho KO mice, it suggests that the kidney is the principal contributor of klotho and klotho-induced antiaging traits.92

FGF23, along with FGF19 and FGF21, is a member of the FGF19 subfamily of endocrine FGFs. FGF23 is predominantly expressed and secreted from osteocytes and osteoblasts. The major target for FGF23 is the kidney, where FGF23 suppresses renal phosphate reabsorption by decreasing the expression and membrane insertion of the sodium-dependent phosphate co-transporters NPT2a and NPT2c, demonstrating that FGF23 is a long range endocrine hormone.93 In the kidney, excess FGF23 reduces circulating levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3, the active form of vitamin D) by inhibiting CYP27B1, the enzyme that converts 25-(OH)D3 to 1,25(OH)2D3, and stimulating CYP24A1, a mitochondrial enzyme responsible for inactivating 1,25(OH)2D3 through the C-24 oxidation pathway.94 Unexpectedly, Fgf23 KO mice develop multiple aging-like phenotypes that are almost identical with those observed in klotho-deficient mice.95 These observations strongly suggest that klotho and FGF23 may function in a common signal transduction pathway. Thus, the kidney-bone endocrine axis mediated by klotho and FGF23 has emerged as a primary mechanism for regulation of phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. The aging-like phenotype observed in klotho and Fgf23 KO mice may be caused by toxicity resulting from excess phosphate and/or vitamin D. Of note, a universal characteristic of patients with CKD is high serum phosphate levels. And patients with CKD have high serum FGF23 levels with decreased klotho expression in the kidney. While klotho has been reported to function as a secreted Wnt antagonist8 and it has been reported that loss of klotho contributes to CKD through increased Wnt signaling,96 it remains to be determined what the role of Wnt signaling is in regulating the klotho-FGF23 axis in the kidney-bone network (Fig. 1). Dysregulation of mineral metabolism exacerbates the severity and progression of renal failure. A deeper understanding of mineral metabolism is pivotal for the prevention and treatment of CKD.

Wnt signaling in aging intestine

During intestinal development, Wnt signaling plays a crucial role in endoderm specification and gut tube patterning, as well as in intestinal stem cell (ISC) maintenance and intestinal epithelial homeostasis.97 The intestinal epithelium is renewed every 3–5 days and is one of the fastest self-renewed tissues among all mammalian tissues.98 This rapid turnover is fueled by dedicated, mitotically active ISCs at the bottom of the intestinal crypts.99,100 After many years of searching, a landmark 2007 study identified LGR5 as a marker for these rapidly cycling ISCs at the base of each intestinal crypt.101 LGR5 is a receptor for R-spondins, noted earlier as Wnt-related ligands that enhance Wnt/β-catenin signaling.102 The LGR5+ ISCs continually generate the cells that differentiate into either the secretory lineage (Paneth, enteroendocrine, and goblet) or the absorptive lineage (enterocytes) cells of the intestinal epithelium.103 Wnt signaling is critical and required for this process.104 The relative balance of Wnt versus Notch pathway signaling in these LRG5+ ISCs determines the epithelial cell fate to become either secretory lineage (high Wnt/low Notch signaling) or absorptive lineage (low Wnt/high Notch signaling).105 Loss of Wnt signaling in these cells results in loss of secretory lineage epithelial cells and loss of epithelial and crypt structure.106 Disruption of the Wnt/Notch signaling balance in the ISC results in abnormal changes in stem cell fate ratios and loss of intestinal barrier function (leaky gut).107,108 Targeted loss of LGR5 results in loss of crypt ISCs and loss of intestinal epithelial renewal.109 Inhibiting Wnt signaling in adult mice with an inducible Wnt antagonist, DKK1, blocks proliferation within crypts and results in crypt loss.110,111 Targeted complete deletion of β-catenin in the intestinal crypt also results in loss of ISCs and intestinal barrier function, causing intestinal hyperpermeability (leaky gut).112 Paneth cells in the small intestinal crypts are major producers of WNT2B and WNT3A that promote ISC health.113 Wnt signaling from surrounding mesodermal fibroblasts and possibly immune cells also plays an essential role in establishing the small intestinal and colonic crypt niche.114 These results demonstrate that Wnt signaling is required not only to form crypts but also to maintain intestinal homeostasis, including barrier function, throughout adult life. Significantly, a key recent study has shown that aging results in loss of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the LGR5+ crypt ISCs in mice and humans.115 This loss of ISC Wnt signaling is also associated with loss of Notch signaling and loss of another key ISC stem cell marker, ASCL2 (also a Wnt signaling target gene).116 Importantly, culture of intestinal organoids from aged mice and aged humans ex vivo with additional WNT3 was able to restore the gene expression pattern to that of young ISCs.115 Other investigators have proposed loss of Wnt signaling is a key feature driving ISC aging. This has potential therapeutic implications for the aging intestine (and bone, see below) by restoring Wnt signaling. For example, the Wnt/β-catenin agonist lithium has been shown to promote repair of the intestinal epithelium and barrier function.117

Remarkably, most (>80%) sporadic colorectal cancer cases are the result of loss of both APC alleles.118 Since intestinal stem cells are dependent on Wnt activity, it is not surprising that components of the Wnt pathway are frequently mutated in colorectal carcinomas.118–121 Studies have shown that the LGR5+ ISCs are the source of abnormally proliferating cells in colon polyps and colon cancer.122 Stimulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in intestinal epithelium via the removal of the Wnt pathway antagonist APC results in abnormal proliferation and ectopic crypt development that leads to polyp formation and can become colon cancer.97, 123,124 Production of short chain fatty acids (SCFA), especially butyrate, by the intestinal microbiota is associated with reduced colon cancer risk in part through suppression of excessive Wnt/β-catenin signaling.125

Much recent interest in bone metabolism, especially in aging, has focused on the role of the intestinal tract, especially the role of dysregulated intestinal epithelial barrier function, resulting in hyperpermeability (leaky gut), and the intestinal microbiome.126 Leaky gut increases with aging in species from Drosophila to humans,127–129and can promote systemic inflammation via LPS and other microbial products.130 Several studies have shown significant effects of the microbiome on bone health, resulting in a new area of study termed osteomicrobiology.131 So called inflammaging (systemic inflammation characteristic of aging) has been thought to contribute to aging bone loss by stimulation of osteoclast activity while inhibiting osteoblasts.132,133 A key recent study showed that inflammaging in aging mice was the result of changes in the intestinal microbiome that result in leaky gut.134 When transplanted with microbiome from young mice, the leaky gut and systemic inflammation in old mice were prevented. In support of this model, ovariectomy is used to model age-related bone loss, and recent studies have shown that treatment of ovariectomized mice with probiotics can prevent bone loss, at least in part by preventing leaky gut and systemic inflammation.135,136 Probiotics are well established for ameliorating leaky gut and promoting intestinal barrier function.137 Significantly, many of these microbiome effects may all be related to ISC Wnt signaling (needed for a healthy gut barrier, see above) because recent studies also show that both probiotics and the microbiome regulate Wnt signaling in bone and ISCs.138,139 The intestinal microbiome has significant effects on Wnt signaling in the crypt ISCs. Reduced ISC Wnt/β-catenin activity and decreased Wnt5a and Wnt11 expression were observed in mice lacking commensal bacteria.140 Several studies have also shown a clear link between Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling by the microbiome and ISC Wnt signaling.141 Thus, an abnormal microbiome may disrupt ISC Wnt signaling required to maintain normal intestinal crypt cell fate and barrier function and may be a critical cause of inflammaging resulting in aging-associated bone loss, as seen in the ovarectomized mouse model.142,143

As we have mentioned above, although genetic evidence has shown that LRP5 has crucial roles in regulating bone mass, the mechanisms by which LRP5 controls bone formation remain unclear. Unexpectedly, based on mouse genetic studies, a model was developed in which LRP5 regulates bone mass by suppressing serotonin synthesis in the duodenum.40 It was suggested that intestinally derived circulating serotonin plays critical roles in controlling bone formation and bone mass. However, contradictory results have been reported.26,41 These studies favor a model in which LRP5 functions occur within osteoblast lineage cells, mostly in osteocytes. There has been a public debate about these discrepancies.144,145 Therefore, the mechanisms through which LRP5 regulates bone mass need to be further investigated. Of note, the intestinal tract is also one of the principal organs that control the dietary balance of calcium and phosphate so important for bone health.

Wnt signaling in aging adipose tissue

Adipose tissue is a loose connective tissue consisting mainly of adipocytes. Mammals have two different types of adipose tissue: white adipose tissue (WAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT). The primary purpose for white adipose tissue is to store lipids and release fatty acids when fuel is required. Brown adipose tissue has a metabolic and thermogenic role and is more prominent in neonates and infants. Wnt signaling suppresses adipogenesis by blocking induction of PPARγ and CEBPα, the master regulators of adipogenesis. Conversely, disruption of extracellular or intracellular Wnt signaling with recombinant sFRP1/2 or through constitutive expression of Axin lead to spontaneous adipocyte differentiation.146,147 LRP5 has been reported to inhibit adipogenesis and enhance osteoblastogenesis.148–150 Bone marrow adipose tissue (BMAT) has emerged as a unique adipose depot that has been recently recognized as an important endocrine tissue. This fat depot makes up 50–70% of the marrow space in healthy adult humans. BMAT accumulates with aging and in diverse clinical conditions such as osteoporosis, diabetes, anorexia nervosa and obesity.151,152 Interestingly, it has been recently demonstrated that BMAT differentiation is modulated by sclerostin, which inhibits Wnt signaling in pre-adipocytes and promotes BMAT formation.153

Wnt signaling plays critical role in regulating mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) fate. Activation of Wnt signaling stimulates myogenesis and inhibits adipogenesis.154–157 It has been reported that Wnt signaling promotes the differentiation of adipose progenitor cells into fibroblastic cells rather than adipocytes.116 Leptin is synthesized by mature adipocytes in response to changes in body fat mass and nutritional status. Leptin regulates bone mass through the central nervous system (Fig. 1).158 Interestingly, leptin increases osteoblast secretion of FGF23, with a consequent reduction in phosphate resorption.159

As described above, sclerostin has emerged as an endocrine factor that regulates glucose and fat metabolism.71 Outside of the skeleton, sclerostin is present in the serum, supporting a circulating endocrine role.160,161 Circulating sclerostin increases progressively with age and the higher serum sclerostin levels found in elderly post-menopasual women are associated with a greater risk of hip fractures.162–164 More recently, circulating sclerostin has been reported to be associated with glucose and adipose tissue metabolism.71,165–167 Sclerostin KO mice have reduced adipogenesis, increased insulin sensitivity, and are similar to the mice treated with a sclerostin antibody. These mice are resistant to obesogenic diet-induced disturbances in metabolism. Those effects are due to the action of sclerostin on white adipose tissue.71,149 Since adipocytes do not produce sclerostin, these findings suggest an endocrine function for sclerostin that facilitates communication between the bone and adipose tissue. Taken together, these results support the existence of a novel endocrine regulatory loop through which sclerostin, produced by bone cells, contributes to the regulation of glucose and adipose tissue metabolism while affecting the skeleton.

Conclusions

As one of a handful of highly conserved signaling pathways, Wnt is expressed repeatedly during development to regulate many cellular processes. Indeed, Wnt signaling plays essential roles during bone, kidney, intestine, and adipose tissue development and homeostasis. Emerging evidence suggests that Wnt signaling may play a fundamental role in the aging process of those organs as well.168 Bone is not only the major reservoir for calcium and phosphate, but also the largest organ serving multiple physiologic functions, including mineral and energy metabolism. The interaction among bone, kidney, intestine, and adipose tissue may be controlled and regulated by many endocrine signals among these organs, such as FGF23, klotho, SOST, osteocalcin, vitamin D, and leptin (Fig. 1). Since the aging process is characterized by structural and functional decline in almost all tissues and organs, understanding the role of Wnt signaling in the interactions among bone, kidney, intestine, adipose tissue, and other organs in aging may shed light on the pathogenesis of age-related diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AR054465 and R01 AR070222 to DC.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The author declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Baron R, & Kneissel M. 2013. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat. Med 19:179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nusse R, & Clevers H. 2017. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell 169:985–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee E, Salic A, Kruger R, et al. 2003. The roles of APC and Axin derived from experimental and theoretical analysis of the Wnt pathway. PLoS Biol 1:e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, & He X. 2009. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev. Cell 17:9–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leyns L, Bouwmeester T, Kim S, et al. 1997. Frzb-1 is a secreted antagonist of Wnt signaling expressed in the Spemann organizer. Cell 88:747–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsieh JC, Rattner A, Smallwood PM, et al. 1999. Biochemical characterization of Wnt frizzled interactions using a soluble, biologically active vertebrate Wnt protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:3546–3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glinka A, Wu W, Delius H, et al. 1998. Dickkopf-1 is a member of a new family of secreted proteins and functions in head induction. Nature 391:357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu H, Fergusson MM, Castilho RM, et al. 2007. Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging. Science 317:803–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao J, Wang J, Liu B, et al. 2001. Low-density lipoprotein receptorrelated protein-5 binds to Axin and regulates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Mol. Cell 7:801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semenov M, Tamai K, & He X. 2005. SOST is a ligand for LRP5/LRP6 and a Wnt signaling inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem 280:26770–26775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruciat CM, & Niehrs C. 2013. Secreted and transmembrane wnt inhibitors and activators. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 5:a015081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimomura Y, Agalliu D, Vonica A, et al. 2010. APCDD1 is a novel Wnt inhibitor mutated in hereditary hypotrichosis simplex. Nature 464:1043–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Q, Wang Y, Dabdoub A, et al. 2004. Vascular development in the retina and inner ear: control by Norrin and Frizzled-4, a high-affinity ligand-receptor pair. Cell 116:883–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kazanskaya O, Glinka A, del Barco Barrantes I, et al. 2004. R-Spondin2 is a secreted activator of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and is required for Xenopus myogenesis. Dev. Cell 7:525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hao HX, Xie Y, Zhang Y, et al. 2012. ZNRF3 promotes Wnt receptor turnover in an R-spondin-sensitive manner. Nature 485:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koo BK, Spit M, Jordens I, et al. 2012. Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature 488:665–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Otın C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, et al. 2013. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153:1194–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheon SS, Nadesan P, Poon R, et al. 2004. Growth factors regulate β-catenin-mediated TCF-dependent transcriptional activation in fibroblastsduring the proliferative phase of wound healing. Exp. Cell Res 293:267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Surendran K, Simon TC. 2003. CNP gene expression is activated by Wnt signalingand correlates with Wnt4 expression during renal injury. Am. J. Physiol. RenalPhysiol 284: F653–F662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berwick DC, Harvey K. 2014. The regulation and deregulation of Wnt signalingby PARK genes in health and disease. J. Mol. Cell Biol 6: 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riise J, Plath N, Pakkenberg B, et al. 2015. Aberrant Wnt signalingpathway in medial temporal lobe structures of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural Transm 122: 1303–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye X, Zerlanko B, Kennedy A, et al. 2007. Downregulation of Wnt signaling is a trigger for formation of facultative heterochromatin and onset of cell senescence in primary human cells. Mol. Cell 27:183–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brack AS, Conboy MJ, Roy S, et al. 2007. Increased Wnt signaling during aging alters muscle stem cell fate and increases fibrosis. Science 317:807–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu H et al. 2005. Sequential roles of Hedgehog and Wnt signaling in osteoblast development. Development 132:49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodda SJ & McMahon AP. 2006. Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development 133:3231–3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joeng KS, Schumacher CA, Zylstra-Diegel CR, et al. 2011. Lrp5 and Lrp6 redundantly control skeletal development in the mouse embryo. Dev. Biol 359:222–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gong Y, Slee RB, Fukai N, et al. 2001. LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell 107:513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyden LM, Mao J, Belsky J, et al. 2002. High bone density due to a mutation in LDL-receptor-related protein 5. N. Engl. J. Med 346:1513–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Little RD, Carulli JP, Del Mastro RG, et al. 2002. A mutation in the LDL receptor-related protein 5 gene results in the autosomal dominant high-bone-mass trait. Am. J. Hum. Genet 70:11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Wesenbeeck L, Cleiren E, Gram J, et al. 2003. Six novel missense mutations in the LDL Receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) gene in different conditions with increased bone density. Am. J. Hum. Genet 72:763–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellies DL, Viviano B, McCarthy J, et al. 2006. Bone density ligand, Sclerostin, directly interacts with LRP5 but not LRP5G171V to modulate Wnt activity. J. Bone Miner. Res 21:1738–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mani A, Radhakrishnan J, Wang H, et al. 2007. LRP6 mutation in a family with early coronary disease and metabolic risk factors. Science 315:1278–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balemans W, Ebeling M, Patel N, et al. 2001. Increased bone density in sclerosteosis is due to the deficiency of a novel secreted protein (SOST). Hum. Mol. Genet 10:537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balemans W, Patel N, Ebeling M, et al. 2002. Identification of a 52 kb deletion downstream of the SOST gene in patients with van Buchem disease. J. Med. Genet 39:91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brunkow ME, Gardner JC, Van Ness J, et al. 2001. Bone dysplasia sclerosteosis results from loss of the SOST gene product, a novel cystine knotcontaining protein. Am. J. Hum. Genet 68:577–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balemans W, Piters E, Cleiren E, et al. 2008. The binding between sclerostin and LRP5 is altered by DKK1 and by high-bone mass LRP5 mutations. Calcif. Tissue Int 82:445–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ai M, Holmen SL, Van Hul W, et al. 2005. Reduced affinity to and inhibition by DKK1 form a common mechanism by which high bone mass-associated missense mutations in LRP5 affect canonical Wnt signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol 25:4946–4955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kato M, Patel MS, Levasseur R, et al. 2002. Cbfa1-independent decrease in osteoblast proliferation, osteopenia, and persistent embryonic eye vascularization in mice deficient in Lrp5, a Wnt coreceptor. J. Cell Biol 157:303–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmen SL, Giambernardi TA, Zylstra CR, et al. 2004. Decreased BMD and limb deformities in mice carrying mutations in both Lrp5 and Lrp6. J. Bone Miner. Res 19:2033–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yadav VK, Ryu JH, Suda N, et al. 2008. Lrp5 controls bone formation by inhibiting serotonin synthesis in the duodenum. Cell 135:825–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cui Y, Niziolek PJ, MacDonald BT, et al. 2011. Lrp5 functions in bone to regulate bone mass. Nat. Med 17: 684–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan Y, Tang D, Chen M, et al. 2009. Axin2 controls bone remodeling through the {beta}-catenin-BMP signaling pathway in adult mice. J. Cell Sci 122:3566–3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glass DA II, Bialek P, Ahn JD, et al. 2005. Canonical Wnt signaling in differentiated osteoblasts controls osteoclast differentiation. Dev. Cell 8:751–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holmen SL, Robertson SA, Zylstra CR, et al. 2005. Wntindependent activation of beta-catenin mediated by a Dkk1-Fz5 fusion protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 328:533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kramer I, Halleux C, Keller H, et al. 2010. Osteocyte Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is required for normal bone homeostasis. Mol. Cell Biol 30:3071–3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang B, Jin H, Zhu M, et al. 2014. Chondrocyte β-catenin signaling regulates postnatal bone remodeling through modulation of osteoclast formation in a murine model. Arthritis Rheumatol 66:107–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Long F 2012. Building strong bones: molecular regulation of the osteoblast lineage. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 13:27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tu X, Delgado-Calle J, Condon KW, et al. 2015. Osteocytes mediate the anabolic actions of canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E478–E486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Javaheri B, Stern AR, Lara N, et al. 2014. Deletion of a single beta-catenin allele in osteocytes abolishes the bone anabolic response to loading. J Bone Miner Res 29:705–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin C, Jiang X, Dai Z, et al. 2009. Sclerostin mediates bone response to mechanical unloading through antagonizing Wnt/bcatenin signaling. J Bone Miner Res 24:1651–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sawakami K, Robling AG, Ai M, et al. 2006. The Wnt co-receptor LRP5 is essential for skeletal mechanotransduction but not for the anabolic bone response to parathyroid hormone treatment. J Biol Chem 281:23698–23711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poole KE, van Bezooijen RL, Loveridge N, et al. 2005. Sclerostin is a delayed secreted product of osteocytes that inhibits bone formation. FASEB J 19:1842–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riminucci M, Collins MT, Fedarko NS, et al. 2003. FGF-23 in fibrous dysplasia of bone and its relationship to renal phosphate wasting. J. Clin. Invest 112:683–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farr JN, Roforth MM, Fujita K, et al. 2015. Effects of age and estrogen on skeletal gene expression in humans as assessed by RNA sequencing. PLoS One 10:e0138347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karasik D, Rivadeneira F, & Johnson ML. 2016. The genetics of bone mass and susceptibility to bone diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 118:496–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rivadeneira F, Styrkarsdottir U, Estrada K, et al. 2009. Twenty bone-mineral-density loci identified by large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet 41:1199–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Styrkarsdottir U, Halldorsson BV, Gretarsdottir S, et al. 2008. Multiple genetic loci for bone mineral density and fractures. N. Engl. J. Med 358:2355–2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wehmeyer C, Frank S, Beckmann D, et al. 2016. Sclerostininhibition promotes TNF-dependent inflammatory joint destruction. Sci. Transl. Med 8:330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu B & Wang CY. 2016. Osteoporosis: the result of an aged bonemicroenvironment. Trends Mol. Med 22:641–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.overare-Skrtic S, Henning P, Liu X et al. 2014. Osteoblastderived WNT16 represses osteoclastogenesis and prevents cortical bone fragility fractures. Nat Med 20:1279–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu B, Chang J, Liu Y et al. 2014. Wnt4 signaling prevents skeletal aging and inflammation by inhibiting nuclear factor-kappaB. Nat Med 20:1009–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sims AM, Shephard N, Carter K, et al. 2008. Genetic analyses in a sample of individuals with high or low BMD shows association with multiple Wnt pathway genes. J. Bone Miner. Res 23:499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yerges LM, Klei L, Cauley JA, et al. 2009. High-density association study of 383 candidate genes for volumetric BMD at the femoral neck and lumbar spine among older men. J. Bone Miner. Res 24:2039–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simsek Kiper PO, Saito H, Gori F, Unger et al. 2016. Cortical-bone fragility–insights from sFRP4 deficiency in Pyle’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine 374:2553–2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Estrada K, Styrkarsdottir U, Evangelou E, et al. 2012. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 56 bone mineral density loci and reveals 14 loci associated with risk of fracture. Nat. Genet 44:491–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Adachi JD, et al. 2016. Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med 375:1532–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Robling AG, Castillo AB, & Turner CH. 2006. Biomechanical and molecular regulation of bone remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 8:455–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martin A, David V, & Quarles LD. 2012. Regulation and function of the FGF23/ klotho endocrine pathways. Physiol. Rev 92:131–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Razzaque MS 2009. The FGF23-klotho axis: Endocrine regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 5: 611–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.DiGirolamo DJ, Clemens TL, & Kousteni S. 2012. The skeleton as an endocrine organ. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 8: 674–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim SP, Frey JL, Li Z, et al. 2017. Sclerostin influences body composition by regulating catabolic and anabolic metabolism in adipocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114:E11238–E11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bridgewater D, Cox B, Cain J, et al. 2008. Canonical WNT/beta-catenin signaling is required for ureteric branching. Dev. Biol 317:83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carroll TJ, Park JS, Hayashi S, et al. 2005. Wnt9b plays a central role in the regulation of mesenchymal to epithelial transitions underlying organogenesis of the mammalian urogenital system. Dev. Cell 9:283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Park JS, Valerius MT, & McMahon AP. 2007. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates nephron induction during mouse kidney development. Development 134:2533–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karner CM, Das A, Ma Z, et al. 2011. Canonical Wnt9b signaling balances progenitor cell expansion and differentiation during kidney development. Development 138:1247–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Park JS, Ma W, O’Brien LL, et al. 2012. Six2 and Wnt regulate self-renewal and commitment of nephron progenitors through shared gene regulatory networks. Dev. Cell 23:637–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boivin FJ, Sarin S, Lim J, et al. 2015. Stromally expressed beta-catenin modulates Wnt9b signaling in the ureteric epithelium. PLoS ONE 10:e0120347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu J, Carroll TJ, Rajagopal J, et al. 2009. A Wnt7b-dependent pathway regulates the orientation of epithelial cell division and establishes the cortico-medullary axis of the mammalian kidney. Development 136:161–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Levinson RS, Batourina E, Choi C, et al. 2005. Foxd1-dependent signals control cellularity in the renal capsule, a structure required for normal renal development. Development 132:529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Halt K, & Vainio S. 2014. Coordination of kidney organogenesis by Wnt signaling. Pediatr. Nephrol 29:737–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhou L & Liu Y. 2015. Wnt/β-catenin signalling and podocyte dysfunction in proteinuric kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol 11:535–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Little MH 2006. Regrow or repair: potential regenerative therapies for the kidney. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 17:2390–2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rinkevich Y, Montoro DT, Contreras-Trujillo H, et al. 2014. In vivo clonal analysis reveals lineage-restricted progenitor characteristics in mammalian kidney development, maintenance, and regeneration. Cell Rep 7:1270–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Naito AT, Sumida T, Nomura S, et al. 2012. Complement C1q activates canonical Wnt signaling and promotes aging-related phenotypes. Cell 149:1298–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bian A, Neyra JA, Zhan M, et al. 2015. Klotho, stem cells, and aging. Clin. Interv. Aging 10: 1233–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kooman JP, Kotanko P, Schols AM, et al. 2014. Chronic kidney disease and premature ageing. Nat. Rev. Nephrol 10:732–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gewin LS 2018. Renal tubule repair: is Wnt/β-catenin a friend or foe? Genes (Basel). 9:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Oldknow KJ, MacRae VE, & Farquharson C. 2015. Endocrine role of bone: recent and emerging perspectives beyond osteocalcin. J. Endocrinol 225:R1–R19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kuro-o M 2009. Klotho and aging. Biochim Biophys Acta 1790:1049–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, et al. 2005. Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science 309:1829–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Haruna Y, Kashihara N, Satoh M, et al. 2007. Amelioration of progressive renal injury by genetic manipulation of klotho gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:2331–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lindberg K, Amin R, Moe OW, et al. 2014. The kidney is the principal organ mediating klotho effects. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 25:2169–2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gattineni J, Bates C, Twombley K, et al. 2009. FGF23 decreases renal NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c expression and induces hypophosphatemia in vivo predominantly via FGF receptor 1. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol 297:F282eF291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hu MC, Shiizaki K, Kuro-o M, et al. 2013. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and klotho: physiology and pathophysiology of an endocrine network of mineral metabolism. Ann. Rev. Physiol 75:503–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shimada T, Kakitani M, Yamazaki Y, et al. 2004. Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J. Clin. Invest 113:561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhou L, Li Y, Zhou D, et al. 2013. Loss of Klotho contributes to kidney injury by derepression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 24:771–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nusse RH & Clevers. 2017. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell 169(6):985–999.Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Barker N 2014. Adult intestinal stem cells: critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 15(1):19–33. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cheng H, & Leblond CP. 1974. Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine. V. Unitarian theory of the origin of the four epithelial cell types. Am. J. Anat 141:537–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Clevers H, Loh KM, & Nusse R. 2014. Stem cell signaling. An integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science 346(6205):1248012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, et al. 2007. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449(7165):1003–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.de Lau W, Barker N, Low TY, et al. 2011. Lgr5 homologues associate with Wnt receptors and mediate R-spondin signalling. Nature 476(7360):293–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.van der Flier LG, & Clevers H. 2009. Stem cells, self-renewal, and differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. Ann. Rev. Physiol 71:241–60. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Farin HF, Jordens I, Mosa MH, et al. 2016. Visualization of a short-range Wnt gradient in the intestinal stem-cell niche. Nature 530(7590):340–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.van der Flier LG, & Clevers H. 2009. Stem cells, self-renewal, and differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. Ann. Rev. Physiol 71:241–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fevr T, Robine S, Louvard D, et al. 2007. Wnt/beta-catenin is essential for intestinal homeostasis and maintenance of intestinal stem cells. Mol. Cell Biol 27(21):7551–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Forsyth CB, Shaikh M, Bishehsari F, et al. 2017. Alcohol Feeding in Mice Promotes Colonic Hyperpermeability and Changes in Colonic Organoid Stem Cell Fate. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res 41(12):2100–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dahan S, Rabinowitz KM, Martin AP, et al. 2011. Notch-1 signaling regulates intestinal epithelial barrier function, through interaction with CD4+ T cells, in mice and humans. Gastroenterology 140(2):550–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Barker N 2014. Adult intestinal stem cells: critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 15(1):19–33. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pinto D, Gregorieff A, Begthel H, et al. 2003. Canonical Wnt signals are essential for homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium. Genes Dev.17:1709–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kuhnert F, Davis CR, Wang HT, et al. 2004. Essential requirement for Wnt signaling in proliferation of adult small intestine and colon revealed by adenoviral expression of Dickkopf-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:266–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fevr T, Robine S, Louvard D, et al. 2007. Wnt/beta-catenin is essential for intestinal homeostasis and maintenance of intestinal stem cells. Mol. Cell Biol 27(21):7551–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Clevers H 2013. The intestinal crypt, a prototype stem cell compartment. Cell 154(2):274–84. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Koch S 2017. Extrinsic control of Wnt signaling in the intestine. Differentiation 97:1–8. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nalapareddy K, Nattamai KJ, Kumar RS, et al. 2017. Canonical Wnt signaling ameliorates aging of intestinal stem cells. Cell Rep. 18(11):2608–2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Schuijers J, Junker JP, Mokry M, et al. 2015. Ascl2 acts as an R-spondin/Wnt-responsive switch to control stemness in intestinal crypts. Cell Stem Cell 16(2):158–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Raup-Konsavage WM, Cooper TK, Yochum GS. (2016) A Role for MYC in Lithium-Stimulated Repair of the Colonic Epithelium After DSS-Induced Damage in Mice. Dig Dis Sci. 61(2):410–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, et al. 2007. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science 318:1108–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lammi L, Arte S, Somer M, et al. 2004. Mutations in AXIN2 cause familial tooth agenesis and predispose to colorectal cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet 74:1043–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH, et al. 2009. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature 457:608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fumagalli A, J. Drost, S.J. Suijkerbuijk, et al. 2017. Genetic dissection of colorectal cancer progression by orthotopic transplantation of engineered cancer organoids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114:E2357–E2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH, et al. 2009. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature 457(7229):608–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sansom OJ, Reed KR, Hayes AJ, et al. 2004. Loss of Apc in vivo immediately perturbs Wnt signaling, differentiation, and migration. Genes Dev. 18:1385–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Andreu P, Colnot S, & Godard C, et al. 2005. Crypt-restricted proliferation and commitment to the Paneth cell lineage following Apc loss in the mouse intestine. Development 132:1443–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zeng H, Lazarova DL, & Bordonaro M. 2014. Mechanisms linking dietary fiber, gut microbiota and colon cancer prevention. World J. Gastrointest Oncol 6(2):41–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hsu E, & Pacifici R. 2018. From osteoimmunology to osteomicrobiology: how the microbiota and the immune system regulate bone. Calcif. Tissue Int 102(5):512–521. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tran L, & Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. 2013. Age-associated remodeling of the intestinal epithelial barrier. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 68(9):1045–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Scott KA, Ida M, Peterson VL, et al. 2017. Revisiting Metchnikoff age-related alterations in microbiota-gut-brain axis in the mouse. Brain Behav Immun 65:20–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Rera M, Clark RI, & Walker DW. 2012. Intestinal barrier dysfunction links metabolic and inflammatory markers of aging to death in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109(52):21528–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bischoff SC, Barbara G, & Buurman W, et al. 2014. Intestinal permeability—a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 14:189 Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Jones RM, Mulle JG, & Pacifici R. 2017. Osteomicrobiology: The influence of gut microbiota on bone in health and disease. Bone pii: S8756–3282(17) 30148–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Jones D, Glimcher LH, & Aliprantis AO. 2011. Osteoimmunology at the nexus of arthritis, osteoporosis, cancer, and infection. J. Clin. Invest 121(7):2534–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Abdelmagid SM, Barbe MF, & Safadi FF. 2015. Role of inflammation in the aging bones. Life Sci 123:25–34. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Thevaranjan N, Puchta A, Schulz C, et al. 2018. Age-Associated Microbial Dysbiosis Promotes Intestinal Permeability, Systemic Inflammation, and Macrophage Dysfunction. Cell Host Microbe 23(4):570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Li JY, Chassaing B, Tyagi AM, et al. 2016. Sex steroid deficiency-associated bone loss is microbiota dependent and prevented by probiotics. J. Clin. Invest 126(6):2049–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Britton RA, Irwin R, Quach D, et al. 2014. Probiotic L. reuteri treatment prevents bone loss in a menopausal ovariectomized mouse model. J. Cell Physiol 229(11):1822–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Mennigen R, & Bruewer M. 2009. Effect of probiotics on intestinal barrier function. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1165:183–189. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Pierzchalska M, Panek M, Czyrnek M, et al. 2017. Probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus bacteria or synthetic TLR2 agonist boost the growth of chicken embryo intestinal organoids in cultures comprising epithelial cells and myofibroblasts. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis 53:7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Zhang J, Motyl KJ, Irwin R, et al. 2015. Loss of Bone and Wnt10b Expression in Male Type 1 Diabetic Mice Is Blocked by the Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri. Endocrinology 156(9):3169–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Neumann PA, Koch S, Hilgarth RS, et al. 2014. Gut commensal bacteria and regional Wnt gene expression in the proximal versus distal colon. Am. J. Pathol 184(3):592–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Hou Q, Ye L, Huang L, et al. 2017. The Research Progress on Intestinal Stem Cells and Its Relationship with Intestinal Microbiota. Front. Immunol 8:599 Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Rios-Arce ND, Collins FL, Schepper JD, et al. 2017. Epithelial Barrier Function in Gut-Bone Signaling. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 1033:151–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Hsu E, & Pacifici R. 2017. From Osteoimmunology to osteomicrobiology: How the microbiota and the immune system regulate bone. Calcif. Tissue Int 102(5):512–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kode A, Obri A, Paone R, et al. 2014. Lrp5 regulation of bone mass and serotonin synthesis in the gut. Nat Med 20: 1228–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Cui Y, Niziolek PJ, MacDonald BT, et al. 2014. Reply to Lrp5 regulation of bone mass and gut serotonin synthesis. Nat Med 20: 1229–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Ross SE, Hemati N, Longo KA, et al. 2000. Inhibition of adipogenesis by Wnt signaling. Science 289:950–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Bennett CN, Ross SE, Longo KA, et al. 2002. Regulation of Wnt signaling during adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem 277:30998–31004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Palsgaard JB Emanuelli J. Winnay N, et al. 2012. Cross-talk between insulin and Wnt signaling in preadipocytes: role of Wnt co-receptor low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-5 (LRP5). J. Biol. Chem 287:12016–12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Loh NY, Neville MJ, Marinou K, et al. 2015. LRP5 regulates human body fat distribution by modulating adipose progenitor biology in a dose- and depot-specific fashion. Cell metabolism 21:262–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Qiu W, Andersen TE, Bollerslev J, et al. 2007. Patients with high bone mass phenotype exhibit enhanced osteoblast differentiation and inhibition of adipogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Bone Miner Res 22:1720–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Hardouin P, Rharass T, & Lucas S. 2016. Bone marrow adipose tissue: To be or not to Be a typical adipose tissue? Frontiers in Endocrinology 7: 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Ambrosi TH, Schulz TJ. 2017. The emerging role of bone marrow adipose tissue in bone health and dysfunction. J Mol Med (Berlin, Germany). 95:1291–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Fairfield H, Falank C, Harris E, et al. 2018. The skeletal cell-derived molecule sclerostin drives bone marrow adipogenesis. J Cell Physiol 233:1156–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Kang S, Bennett CN, Gerin I, et al. 2007. Wnt signaling stimulates osteoblastogenesis of mesenchymal precursors by suppressing CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J. Biol. Chem 282:14515–14524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Koza RA, Nikonova L, Hogan J, et al. 2006. Changes in gene expression foreshadow diet-induced obesity in genetically identical mice. PLoS Genet 2:e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Arango NA, Szotek PP, Manganaro TF, et al. 2005. Conditional deletion of beta-catenin in the mesenchyme of the developing mouse uterus results in a switch to adipogenesis in the myometrium. Dev. Biol 288:276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Wang T, Li J, Zhou G, et al. 2017. Specific deletion of β-catenin in Col2-expressing cells leads to defects in epiphyseal bone. Int. J. Biol. Sci 13:1540–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Confavreux C 2011. Bone: from a reservoir of minerals to a regulator of energy metabolism. Kidney Int. Supplement 121:S14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Tsuji K, Maeda T, Kawane T, et al. 2010. Leptin stimulates fibroblast growth factor 23 expression in bone and suppresses renal 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) synthesis in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice. J. Bone Miner. Res 25:1711–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Fairfield H, Rosen CJ, Reagan MR. 2017. Connecting Bone and Fat: The Potential Role for Sclerostin. Curr Mol Biol Rep 3:114–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Drake MT, Khosla S. 2017. Hormonal and systemic regulation of sclerostin. Bone 96:8–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Mirza FS, Padhi ID, Raisz LG, et al. 2010. Serum sclerostin levels negatively correlate with parathyroid hormone levels and free estrogen index in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:1991–1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Arasu A, Cawthon PM, Lui LY, et al. 2012. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research G. Serum sclerostin and risk of hip fracture in older Caucasian women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:2027–2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Ardawi MS, A.A. Rouzi, S.A. Al-Sibiani, et al. 2012. High serum sclerostin predicts the occurrence of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women: the Center of Excellence for Osteoporosis Research Study. J Bone Miner Res 27:2592–2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.García-Martín A, Rozas-Moreno P, Reyes-García R, et al. 2012. Circulating Levels of Sclerostin Are Increased in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Gennari L, Merlotti D, Valenti R, et al. 2012. Circulating sclerostin levels and bone turnover in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:1737–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Gaudio A, Privitera F, Battaglia K, et al. 2012. Sclerostin levels associated with inhibition of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and reduced bone turnover in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:3744–3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.García-Velázquez L, & Arias C. 2017. The emerging role of Wnt signaling dysregulation in the understanding and modification of age-associated diseases. Ageing Res. Rev 37:135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]