Abstract

Objectives: The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) on haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function and determine its mechanism of action.

Materials and methods: HSC were exposed to PGE2 for 2 h and effects on their homing, engraftment and self‐renewal evaluated in vivo. Effects of PGE2 on HSC cell cycle, CXCR4 expression and migration to SDF‐1α were analysed in vitro. Apoptosis was evaluated by examination of survivin expression and active caspase‐3 levels.

Results: Equivalent haematopoietic reconstitution was demonstrated using 4‐fold fewer PGE2‐treated cells compared to controls. Multilineage reconstitution was stable on secondary transplantation, indicating that PGE2 affects long‐term repopulating HSC (LT‐HSC) and that enhanced chimaerism of PGE2‐pulsed cells results from their initial treatment. PGE2 increased CXCR4 expression on mouse and human HSC, increased their migration to SDF‐1αin vitro and enhanced in vivo marrow homing 2‐fold, which was blocked by a CXCR4 receptor antagonist. PGE2 pulse exposure reduced apoptosis of mouse and human HSC, with increase in endogenous caspase inhibitor survivin, and concomitant decrease in active caspase‐3. Two‐fold more HSC entered the cell cycle and proliferated within 24 h after PGE2 pulse exposure.

Conclusions: These studies demonstrate that short‐term PGE2 exposure enhances HSC function and supports the concept of utility of PGE2 as an ex vivo strategy to improve function of haematopoietic grafts, particularly those where HSC numbers are limited.

Introduction

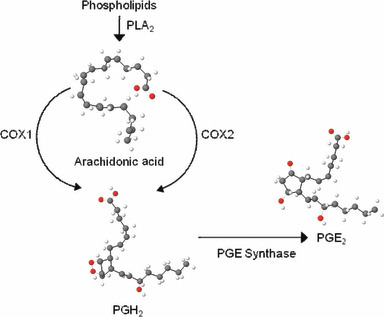

Prostaglandins (PGs) are extremely active short‐lived lipids that act locally in a paracrine or autocrine fashion. There are no organs, tissues or cells in the body that are not affected by these bioactive lipids, either directly or through accessory mechanisms. All nucleated cells synthesize PGs by cleavage of the essential fatty acid, arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids by phospholipase A2, oxidation of free arachidonic acid by two cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX1 and COX2) and subsequent isomerization to an intermediate form, and synthesis of various mature PGs by specific synthases (2, 3). A schematic outline of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) biosynthesis is shown in Fig. 1. PGE2 is the predominant metabolite of arachidonic acid and is the most abundant eicosanoid (4, 5). PGE2 has been implicated in regulation of numerous physiological systems, and is the primary mediator of symptoms of fever (6) and inflammation (4, 7), a regulator of atherosclerosis, blood pressure and strokes (7), and is involved in neoplastic transformation and cancer cell effects on host responses (4, 8). Effects of PGE2 are mediated through four highly conserved G‐protein‐coupled receptors (EP1‐4) with overlapping as well as distinct signalling pathways (9, 10) that can lead to seemingly opposing effects. EP receptor levels vary among tissues, and signalling pathways downstream of the same receptors can vary depending upon cell lineage.

Figure 1.

Outline of prostaglandin E 2 (PGE 2 ) biosynthesis from membrane phospholipids. COX, cyclooxygenase; PLA2, phospholipase A2.

Previously we have shown that PGE2 regulates haematopoiesis, affecting both haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) and progenitor cell (HPC) functions. PGE2 inhibits myelopoiesis in vitro and in vivo (11, 12, 13), and participates in a negative feedback loop regulating myeloid progenitor cell expansion (12, 14, 15). In contrast to its effects on myelopoiesis, PGE2 promotes erythroid and multipotential colony formation in vitro (16, 17). Early studies showed that short‐term ex vivo treatment of bone marrow cells with PGE2 could enhance progenitor cell proliferation (18, 19); however, in vivo dosing led to little or no effect (20). We later showed that pulse exposure of mouse or human bone marrow cells to PGE2 stimulated proliferation, cycling and differentiation of quiescent cells leading to an increase in cycling HPC, suggesting that PGE2 enhances HSC function (21, 22, 23). These studies also clearly defined that dose, timing and length of exposure of haematopoietic cells to PGE2 were critical factors defining stimulatory versus inhibitory effects on haematopoiesis. However, while these studies were the first to clearly implicate PGE2 in positive regulation of haematopoiesis, stem cell function cannot be defined solely based on clonogenic assays. Elucidation of the effects of PGE2 on HSC function requires demonstration that transplanted cells can repopulate haematopoiesis in myeloablated hosts (24). Recently, effects of PGE2 on haematopoietic stem cell function have been revisited and studies in zebrafish and mice (25, 26) validate the stimulatory effects of PGE2 on HSC function that were suggested in earlier in vitro studies. In addition, we have defined mechanisms of action of PGE2 on HSC function, particularly on HSC homing and self‐renewal, which suggest that short‐term exposure of haematopoietic grafts to PGE2 can be utilized for therapeutic benefit in HSC transplantation (25). In this study, we describe pre‐clinical findings supporting the therapeutic ex vivo utility of PGE2 as a facilitator of HSC engraftment.

Materials and methods

Mouse and human cord blood

C57Bl/6 (CD45.2) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). B6.SJL‐PtrcAPep3B/BoyJ (BOYJ) (CD45.1), C57Bl/6 X BOYJ‐F1 (CD45.1/CD45.2) and NOD.Cg‐Prkdcscid IL2rgtm1Wjl/Sz (NSG) mice were bred in‐house. Human umbilical cord blood (UCB) was obtained from Wishard Hospital, Indianapolis, IN, with IRB approval.

Flow cytometry

For detection of SKL cells, streptavidin conjugated with PE‐Cy7 [to stain for biotinylated MACS lineage antibodies (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA, USA)], c‐kit‐APC, Sca‐1‐PE or APC‐Cy7, CD45.1‐PE, CD45.2‐FITC and CD34‐PE were used (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). For SLAM SKL, we used Sca‐1‐PE‐Cy7, c‐kit‐FITC, CD150‐APC (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), CD48‐biotin (eBiosciences) and streptavidin‐PE. UCB CD34+ cells were detected using anti‐human‐CD34‐APC. For multi‐lineage analysis, APC‐Cy7‐Mac‐1, PE‐Cy7‐B‐220 and APC‐CD3 were used (BD Biosciences).

PGE2 pulse exposure

Cells were incubated with 16,16‐dimethyl prostaglandin E2 (dmPGE2) (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) (reconstituted in 100% ethanol) diluted in media, on ice, for 2 h. After incubation, cells were washed twice before use. Vehicle‐treated cells were pulsed with equivalent concentration of ethanol.

Limiting dilution competitive and non‐competitive transplantation

Whole bone marrow cells (CD45.2) were treated with 1 μm dmPGE2 or 0.001% EtOH, washed, admixed with 2 × 105 congenic CD45.1 competitor marrow cells at various ratios, and transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1/CD45.2 mice. Peripheral blood CD45.1 and CD45.2 cells were determined monthly by FACS. HSC frequency was quantified by Poisson statistics using L‐CALC software (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver BC, Canada). Competitive repopulating units (CRU) were calculated as described by Harrison (24). For secondary transplantation, 2 × 106 WBM from previously transplanted CD45.1/CD45.2 mice at 20 weeks post‐transplant were injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1/CD45.2 mice in a non‐competitive fashion.

HSPC homing

For competitive homing studies, SKL cells from CD45.2 and CD45.1 mice were FACS sorted, treated with dmPGE2 or vehicle and 3 × 104 CD45.1 (vehicle or dmPGE2 treated) plus 3 × 104 CD45.2 (dmPGE2 or vehicle treated) SKL cells transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1/CD45.2 mice. Homed CD45.1 and CD45.2 SKL cells in bone marrow were determined after 16 h. To evaluate the role of CXCR4 in homing, Linneg CD45.2 cells were treated with vehicle or 1 μm dmPGE2 plus 10 μm AMD3100 (AnorMed Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada), and 2 × 106 treated cells injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1 mice and homed SKL cells analysed 16 h post‐transplant. Homing of human CD34+ cells was evaluated in NSG mice. UCB mononuclear cells were pulsed with dmPGE2 or vehicle and 4 × 107 cells transplanted into each of five sublethally irradiated (250 cGy) NSG mice. Homed CD34+ cells were analysed 16 h post‐transplantation.

Analysis of CXCR4 expression and apoptosis

Mouse SKL cells or CD34+ UCB cells were pulsed with dmPGE2 or vehicle, washed and cultured in RPMI‐1640/10% HI‐FBS at 37 °C for 24 h. CXCR4 expression was analysed using CXCR4‐PE. Apoptotic levels were measured with FITC‐annexin‐V or FITC‐anti‐active caspase‐3 after culture in RPMI‐1640/2% HI‐FBS at 37 °C for 24 h. For survivin and active caspase‐3 detection, cells were permeabilized and fixed using the CytoFix/CytoPerm kit (BD Biosciences) and stained with anti‐active caspase‐3‐FITC Flow Kit (BD Biosciences) or survivin‐PE (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Survivin and active caspase‐3

Mouse SKL cells or CD34+ UCB cells were pulsed with dmPGE2 or vehicle, washed and cultured in RPMI‐1640/10% HI‐FBS at 37 °C for 24 h. CXCR4, survivin and/or active caspase‐3 were analysed by FACS.

Migration assays

Chemotaxis to SDF‐1αin vitro was determined as described previously (27). Briefly, dmPGE2‐ and vehicle‐treated Lineageneg bone marrow cells, UCB CD34+ cells or peripheral blood CD34+ cells mobilized by G‐CSF were cultured in RPMI/10% HI‐FBS overnight, washed, 2 × 105 cells added to the top chamber of transwells, with or without rmSDF‐1α (R&D Systems) in the bottom chamber, and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Cells migrating to the bottom chamber were enumerated by FACS. Per cent migration was calculated by dividing total cells migrated to lower well, by cell input, multiplied by 100.

Cell cycle analysis

Lineageneg cells were treated with dmPGE2 or vehicle and cultured with rmSCF (50 ng/ml) (R&D Systems), rhFlt‐3 and rhTPO (100 ng/ml each) (Immunex, Seattle, WA, USA) for 20 h. Cells were stained for SLAM SKL, fixed, permeabilized and stained with Hoechst‐33342 followed by Pyronin‐Y. Proportion of SLAM SKL cells in G0, G1, S and G2/M phase was determined by FACS.

Statistical analysis

All pooled values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined using paired or unpaired two‐tailed t‐test functions with Microsoft Excel as appropriate.

Results

PGE2 increased long‐term stem cell engraftment

Competitive repopulation transplantation models in mice allow for quantification of the ability of HSC to repopulate haematopoiesis. When congenic CD45.1 and CD45.2 mouse marrow cells were pulsed with vehicle or PGE2 and transplanted in a limiting‐dilution fashion, into CD45.1/CD45.2 hybrid mice, a model that permits head‐to‐head comparison of HSC populations; significantly enhanced HSC engraftment was observed for PGE2 ‐pulsed bone marrow, compared to controls (Table 1). At 5 months post‐transplantation, analysis of peripheral blood chimaerism showed significantly higher levels of white blood cells derived from PGE2‐treated marrow cells. Analysis of HSC frequency by Poisson statistics or by calculation of competitive repopulating units (CRU), indicated an ∼4‐fold increase in HSC frequency, strongly suggesting a direct effect on HSC. These results agree with similar studies performed in a conventional congenic transplant model (26). Myeloid cells, B and T lymphocytes were reconstituted with no obvious bias in lineage reconstitution. To validate self‐renewal capacity of ex vivo PGE2‐treated repopulating cells, marrow from primary transplantation recipients was harvested and transplanted into secondary recipients without any further ex vivo manipulation. Analysis of chimaerism at 24 weeks after secondary transplantation also showed significantly increased contribution to chimaerism from PGE2‐treated cells from primary recipients (Table 1). That enhanced chimaerism resulting from PGE2 exposure in primary donors was maintained in secondary transplants without additional treatment, indicated that the effect of PGE2 pulse exposure was stable and manifest in long‐term repopulating stem cells (LT‐HSC). On further serial transplantation, persistent enhanced chimaerism resulting from PGE2 pulse exposure prior to transplantation into primary donors, was observed. Transplantation of human haematopoietic cells in immunodeficient mice offers a model system to evaluate human HSC function in vivo (28). In a similar fashion to that shown using mouse bone marrow cells, short‐term ex vivo pulse exposure to PGE2 enhanced engraftment of human UCB HSC in NOD/SCID‐IL2‐γ‐receptor null (NSG) mice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Transient exposure of haematopoietic cells to PGE2 enhances HSC engraftment

| Group | Time of exposure (h)a | Fold increase HSC frequencyb | Fold increase CRUc | % PB chimaerism congenic miced | % PB chimaerism NSGe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | |||||

| Vehicle | 2 | – | – | 13.3 ± 1.4 | 5.1 ± 0.13 | 2.3 |

| 1 μm dmPGE2 | 2 | 4.12 | 3.4 | 40.7 ± 5.0* | 34.2 ± 0.51* | 11.0 |

a Whole mouse bone marrow cells or human umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells were treated on ice with 0.001% ethanol or 1 μm dmPGE2 for 2 h and washed twice in ice‐cold PBS before transplant.

b HSC cell frequency was calculated by Poisson statistics at 20 weeks post‐transplant (P0 vehicle = 89 586; P0 PGE2 = 21 753) using L‐CALC software (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada).

c CRU were calculated based on PB chimaerism at 20 weeks in primary transplants according to the method of Harrison (24).

d Chimaerism in PB is shown at 20 weeks in primary transplant and 24 weeks in secondary transplant (mean ± SEM). Data are for 10 mice in two experiments, each assayed individually.

e Chimaerism in PB of NSG (NOD.Cg‐Prkdcscid IL2rgtm1 Wjl/Sz) mice at 8 weeks post‐transplant with vehicle‐ or PGE2‐pulsed umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells.

*P < 0.05.

PGE2 increased HSC homing efficiency

Effects on cell division, homing or proliferation can positively or negatively affect HSC function. As we have previously shown that PGE2 can have dual effects on haematopoiesis, we sought to define its mechanism of action to better understand the potential clinical utility of transient ex vivo PGE2 exposure. Successful haematopoietic reconstitution requires that administered haematopoietic cells traffic/home to bone marrow niches where they can engraft, self‐renew and differentiate. We therefore evaluated effects of PGE2 exposure on these HSC functions.

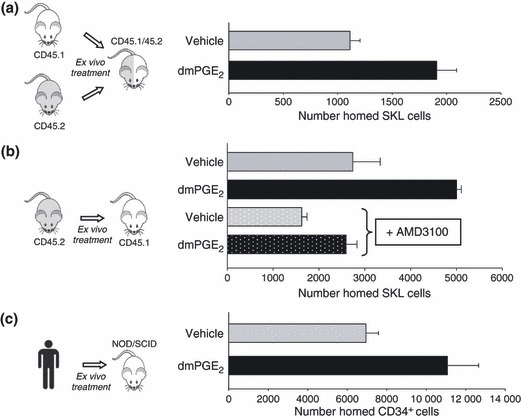

To evaluate homing efficiency of HSC and determine whether the effect of PGE2 pulse exposure results from direct PGE2 effect, or is mediated through accessory cells, we FACS sorted congenic mouse Lineageneg Sca‐1+, c‐kit+ (SKL) cells, enriched for LT‐HSC, treated them ex vivo and directly compared homing efficiency of PGE2‐treated and vehicle‐treated SKL cells head‐to‐head in CD45 hybrid mice. Pulse exposure of purified SKL cells to PGE2 increased their homing efficiency 2‐fold compared to controls (Fig. 2a). In traditional homing assays, increased homing of more differentiated Lineageneg, c‐kit+ HPC and Lineageneg cells was not observed, suggesting that the enhanced homing effect of PGE2 is specific to HSC.

Figure 2.

PGE 2 pulse exposure enhances homing of mouse and human HSC. (a) SKL cells were isolated from congenic mice by FACS sorting and treated with vehicle or 1 μm 16, 16‐dimethyl PGE2 (dmPGE2) on ice for 2 h. After incubation, cells were washed and 3 × 104 vehicle‐ or dmPGE2‐treated CD45.1 and 3 × 104 vehicle‐ or dmPGE2‐treated CD45.2 cells injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1/CD45.2 hybrid mice. Number of homed CD45.1 and CD45.2 SKL cells was quantified in bone marrow at 16 h post‐transplantation. Data (mean ± SEM) from 10 mice with treatment groups of five mice, switched to rule out bias. (b) Bone marrow cells from CD45.2 mice were treated with vehicle or dmPGE2, washed, incubated in the presence or absence of 10 μm AMD3100 for 30 min and transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1 mice. Number of homed CD45.2 SKL cells was quantified in bone marrow at 16 h post‐transplantation. Data (mean ± SEM) from three mice per group each assayed individually. (c) Umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells were isolated, treated with vehicle or dmPGE2 and injected into sublethally irradiated NSG mice. Bone marrow was analysed after 16 h for number of homed human CD45+, CD34+ cells. Data (mean ± SEM) from five mice per group each assayed individually.

The CXCR4 and SDF‐1α axis is a critical component of HSC marrow homing (29), and overexpression of CXCR4 in HSC enhances their in vivo homing and engraftment (30, 31, 32). To determine whether up‐regulated CXCR4 would mediate PGE2‐enhanced HSC marrow homing, marrow cells were treated ex vivo with selective CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 (33) after PGE2 pulse exposure and prior to transplantation (Fig. 2b). As expected, PGE2 pulse exposure increased SKL cell homing. Incubation of vehicle or PGE2‐pulsed cells with AMD3100 reduced SKL cell homing and abrogated PGE2 ‐improved homing efficiency. Reduction in HSC homing by AMD3100 is consistent with previous reports (34, 35). To verify the enhancing effect of PGE2 on human cells, CD34+ cells were isolated from cord blood, pulsed with PGE2 or vehicle and their homing capacity analysed in NSG mice, a validated model for human HSC homing (36). PGE2 pulse exposure significantly enhanced homing efficiency of human UCB CD34+ cells in NSG mice (Fig. 2c).

PGE2 increased HSC CXCR4 and migration to SDF‐1α

As PGE2 enhancement of HSC homing was blocked by CXCR4 antagonism and PGE2 has been reported to up‐regulate CXCR4 on CD34+ cells (37) and endothelial cells (38), and increase monocyte chemotaxis to SDF‐1α (39), we evaluated whether improved homing would result from HSC up‐regulation of SDF‐1α/CXCR4 signalling and function. Pulse exposure to PGE2 increased CXCR4 expression on mouse SKL cells and human UCB CD34+ cells (Table 2). HSC selectively migrate to SDF‐1αin vitro (40), a process that reflects their in vivo homing capacity. Vehicle‐ and PGE2‐treated mouse SKL cells and CD34+ cells from human UCB and G‐CSF mobilized peripheral blood all demonstrated significant migration to 100 ng/ml SDF‐1α; however, in all cases, chemotaxis of PGE2‐treated cells was significantly higher (Table 2), indicating that up‐regulation of HSC CXCR4 coincided with enhanced migratory function. The enhancing effect of PGE2 on chemotaxis to SDF‐1α was blocked by AMD3100, indicating that the observed effect was mediated through the CXCR4 receptor.

Table 2.

PGE2 enhances mouse and human HSC CXCR4 expression and migration to SDF‐1α

| SKL cells | UCB CD34+ cellsa | MPB CD34+ cellsa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | dmPGE2 b | Vehicle | dmPGE2 b | Vehicle | dmPGE2 b | |

| % increase CXCR4c | 6.99 ± 2.5 | 26.82 ± 4.4* | 6.88 | 17.31 | – | – |

| % migration to SDF‐1d | 46.8 ± 4.8 | 67.1 ± 5.7* | 27.7 ± 1.2 | 55.6 ± 3.3* | 23.2 ± 1.1 | 41.4 ± 1.8* |

a CD34+ cells were isolated from umbilical cord blood or apheresis products of normal donors mobilized with G‐CSF for allogeneic transplantation.

b Mouse SKL cells or human CD34+ cells were treated on ice with 0.001% ethanol or 1 μm dmPGE2 for 2 h, washed, and resuspended in media with 10% HI‐FCS and cultured at 37 °C for 16 h.

c Cells were pulsed with dmPGE2 and cultured as described above. CXCR4 expression was analysed by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as percentage change in mean fluorescence intensity of CXCR4 expression resulting from treatment with vehicle or dmPGE2.

d Cells were pulsed with dmPGE2 and cultured as described above. After incubation, cells were washed, resuspended in RPMI/0.5% BSA and allowed to migrate to 100 ng/ml recombinant mouse or human SDF‐1α for 4 h. Total cell migration was quantified by flow cytometry. Data (mean ± SEM) are from three experiments.

*P < 0.05.

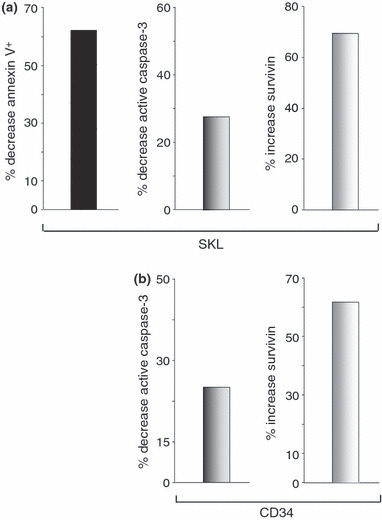

PGE2 decreased apoptosis

Apoptosis is an important regulatory process in normal and malignant haematopoiesis and signalling downstream of PGE2 receptors has been implicated in anti‐apoptotic effects (41, 42, 43). This suggests that enhancement of HSC function by PGE2 could result from enhanced HSC survival. Under reduced serum conditions, pulse exposure to PGE2 reduced annexin‐V and active caspase‐3 in SKL cells, markers of apoptosis in mouse and human HSC (Fig. 3a,b). Furthermore, intracellular levels of the endogenous caspase‐3 inhibitor survivin, were significantly higher in both SKL and CD34+ cells, consistent with our previous findings that survivin regulated apoptosis and proliferation in HSC (44, 45), and studies by others that PGE2 can increase survivin levels in cancer cells (46, 47). QRT‐PCR analysis of treated SKL cells and UCB CD34+ cells showed similarly elevated levels of survivin mRNA.

Figure 3.

PGE 2 decreases apoptosis and increases level of intracellular survivin. (a) Lineage‐depleted mouse bone marrow cells were treated with dmPGE2 or vehicle for 2 h, washed and cultured in 2% HI‐FBS without growth factors for 24 h at 37 °C. After culture, cells were stained for SKL. Apoptosis was measured with FITC‐annexin‐V (left panel). Replicate cells were permeabilized and stained with anti‐active caspase‐3‐FITC (middle panel) or anti‐survivin‐PE (right panel). Data expressed as fold‐change induced by dmPGE2 pulse exposure compared to vehicle‐treated cells. (b) Fold‐change in active caspase‐3 (left panel) and intracellular survivin (right panel) in permeabilized PGE2‐treated UCB CD34+ cells relative to vehicle‐treated cells after culture in 2% HI‐FBS without growth factors for 24 h at 37 °C.

PGE2 increased entry of HSC into the cell cycle

We have previously shown that survivin regulates entry of HSC into the cell cycle and their progression through it (44, 45). Furthermore, β‐catenin, which is implicated in HSC proliferation/self‐renewal, lies downstream of EP receptor pathways (48). Ability of PGE2 to modulate these cell cycle regulators suggests that increase in HSC self‐renewal and proliferation might contribute to enhanced engraftment observed using PGE2‐pulsed cells. PGE2 pulse exposure significantly increased the proportion of primitive LT‐HSC, defined as SLAM (CD150+, CD48−) SKL cells, in the cell cycle (G1 + S/G2M) compared to controls (Fig. 4). No significant effect on rate of cell cycle completion by HPC or more differentiated cells, was observed (data not shown), strongly suggesting that effects of PGE2 on cell cycle rate were selective.

Figure 4.

PGE 2 increases cell cycle of SLAM SKL cells. Lineage‐depleted mouse bone marrow cells were treated with dmPGE2 or vehicle for 2 h, washed and cultured with 50 ng/ml rmSCF and 100 ng/ml each of rhFlt3 and rhTpo for 20 h. Cells were stained for SLAM (CD150+, CD48−) SKL, Hoechst‐33342 and pyronin‐Y and proportion of SLAM SKL cells in G0, G1, S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle determined by flow cytometry. Data (mean ± SEM) from nine mice each assayed individually. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

In vivo analysis of effects of short‐term pulse exposure to PGE2 clearly demonstrated that it has direct and stable effects on HSC function. Enhancement of HSC frequency and engraftment by PGE2 treatment results from effects on HSC homing and cell cycle activity involving up‐regulation of CXCR4 and survivin, with increased chemotactic response to SDF‐1α and reduced apoptosis. Ability to facilitate homing, survival and proliferation of HSC by short‐term ex vivo PGE2 exposure offers an exciting clinical translation strategy to improve haematopoietic transplantation, specially in transplant settings characterized by low HSC numbers, such as with umbilical cord blood cells and some mobilized peripheral blood stem cell products. Our experimental pre‐clinical limiting dilution transplantation studies show that equivalent engraftment is achieved with 4‐fold fewer PGE2‐treated cells compared to untreated cells. Homing and migration studies utilizing UCB CD34+ cells also clearly support potential translation of short‐term PGE2 exposure to human haematopoietic grafts.

While ex vivo utility of PGE2 is clear, it will be interesting to determine whether enhanced HSC engraftment/recovery could also be achieved by administering PGE2 in vivo or if PGE2 used in vivo could further facilitate engraftment of HSC exposed to PGE2 ex vivo. In COX2 knockout mice, haematopoietic recovery from chemotherapy is delayed (49) suggesting that PGE2 production is critical for HSC expansion. However, it must be kept in mind that while short‐term exposure to PGE2 can enhance HSC function, prolonged administration inhibits myelopoiesis (11, 50), which is supported by inhibition of prostaglandin biosynthesis in vivo leading to expansion of myelopoiesis (51), at least in mice. Nevertheless, combination of transient ex vivo PGE2 exposure with selective modulation of in vivo PGE2 biosynthesis may result in significant further improvements in HSC function.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH grants HL069669, HL079654 and HL096305 (to LMP). JH is supported by training grant DK07519. Flow cytometry was performed in the Flow Cytometry Resource Facility of the Indiana University Simon Cancer Center (NCI P30 CA082709).

References

- 1. Miller SB (2006) Prostaglandins in health and disease: an overview. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 36, 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murakami M, Kudo I (2004) Recent advances in molecular biology and physiology of the prostaglandin E2‐biosynthetic pathway. Prog. Lipid Res. 43, 3–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park JY, Pillinger MH, Abramson SB (2006) Prostaglandin E2 synthesis and secretion: the role of PGE2 synthases. Clin. Immunol. 119, 229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murakami M, Kudo I (2006) Prostaglandin E synthase: a novel drug target for inflammation and cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 12, 943–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Serhan CN, Levy B (2003) Novel pathways and endogenous mediators in anti‐inflammation and resolution. Chem. Immunol. Allergy 83, 115–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lazarus M (2006) The differential role of prostaglandin E2 receptors EP3 and EP4 in regulation of fever. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 50, 451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Samuelsson B, Morgenstern R, Jakobsson PJ (2007) Membrane prostaglandin E synthase‐1: a novel therapeutic target. Pharmacol. Rev. 59, 207–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hull MA, Ko SC, Hawcroft G (2004) Prostaglandin EP receptors: targets for treatment and prevention of colorectal cancer? Mol. Cancer Ther. 3, 1031–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Breyer RM, Bagdassarian CK, Myers SA, Breyer MD (2001) Prostanoid receptors: subtypes and signaling. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 41, 661–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S (2007) Prostaglandin E receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 11613–11617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gentile P, Byer D, Pelus LM (1983) In vivo modulation of murine myelopoiesis following intravenous administration of prostaglandin E2. Blood 62, 1100–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pelus LM, Broxmeyer HE, Kurland JI, Moore MA (1979) Regulation of macrophage and granulocyte proliferation. Specificities of prostaglandin E and lactoferrin. J. Exp. Med. 150, 277–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pelus LM, Broxmeyer HE, Moore MA (1981) Regulation of human myelopoiesis by prostaglandin E and lactoferrin. Cell Tissue Kinet. 14, 515–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kurland JI, Broxmeyer HE, Pelus LM, Bockman RS, Moore MA (1978) Role for monocyte‐macrophage‐derived colony‐stimulating factor and prostaglandin E in the positive and negative feedback control of myeloid stem cell proliferation. Blood 52, 388–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kurland JI, Pelus LM, Ralph P, Bockman RS, Moore MA (1979) Induction of prostaglandin E synthesis in normal and neoplastic macrophages: role for colony‐stimulating factor(s) distinct from effects on myeloid progenitor cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76, 2326–2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lu L, Pelus LM, Broxmeyer HE (1984) Modulation of the expression of HLA‐DR (Ia) antigens and the proliferation of human erythroid (BFU‐E) and multipotential (CFU‐GEMM) progenitor cells by prostaglandin E. Exp. Hematol. 12, 741–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lu L, Pelus LM, Piacibello W, Moore MA, Hu W, Broxmeyer HE (1987) Prostaglandin E acts at two levels to enhance colony formation in vitro by erythroid (BFU‐E) progenitor cells. Exp. Hematol. 15, 765–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Feher I, Gidali J (1974) Prostaglandin E2 as stimulator of haemopoietic stem cell proliferation. Nature 247, 550–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Verma DS, Spitzer G, Zander AR, McCredie KB, Dicke KA (1981) Prostaglandin E1‐mediated augmentation of human granulocyte‐macrophage progenitor cell growth in vitro. Leuk. Res. 5, 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gidali J, Feher I (1977) The effect of E type prostaglandins on the proliferation of haemopoietic stem cells in vivo. Cell Tissue Kinet. 10, 365–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pelus LM (1982) Association between colony forming units‐granulocyte macrophage expression of Ia‐like (HLA‐DR) antigen and control of granulocyte and macrophage production. A new role for prostaglandin E. J. Clin. Invest. 70, 568–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pelus LM (1982) CFU‐GM expression of Ia‐like, HLA‐DR, antigen: an association with the humoral control of human granulocyte and macrophage production. Exp. Hematol. 10, 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pelus LM (1989) Modulation of myelopoiesis by prostaglandin E2: demonstration of a novel mechanism of action in vivo. Immunol. Res. 8, 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harrison DE (1980) Competitive repopulation: a new assay for long‐term stem cell functional capacity. Blood 55, 77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoggatt J, Singh P, Sampath J, Pelus LM (2009) Prostaglandin E2 enhances hematopoietic stem cell homing, survival, and proliferation. Blood 113, 5444–5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. North TE, Goessling W, Walkley CR, Lengerke C, Kopani KR, Lord AM et al. (2007) Prostaglandin E2 regulates vertebrate haematopoietic stem cell homeostasis. Nature 447, 1007–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fukuda S, Pelus LM (2006) Internal tandem duplication of Flt3 modulates chemotaxis and survival of hematopoietic cells by SDF1alpha but negatively regulates marrow homing in vivo. Exp. Hematol. 34, 1041–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dick JE, Bhatia M, Gan O, Kapp U, Wang JC (1997) Assay of human stem cells by repopulation of NOD/SCID mice. Stem Cells 15(Suppl. 1), 199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peled A, Petit I, Kollet O, Magid M, Ponomaryov T, Byk T et al. (1999) Dependence of human stem cell engraftment and repopulation of NOD/SCID mice on CXCR4. Science 283, 845–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brenner S, Whiting‐Theobald N, Kawai T, Linton GF, Rudikoff AG, Choi U et al. (2004) CXCR4‐transgene expression significantly improves marrow engraftment of cultured hematopoietic stem cells. Stem Cells 22, 1128–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kahn J, Byk T, Jansson‐Sjostrand L, Petit I, Shivtiel S, Nagler A et al. (2004) Overexpression of CXCR4 on human CD34+ progenitors increases their proliferation, migration, and NOD/SCID repopulation. Blood 103, 2942–2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kollet O, Spiegel A, Peled A, Petit I, Byk T, Hershkoviz R et al. (2001) Rapid and efficient homing of human CD34(+)CD38(‐/low)CXCR4(+) stem and progenitor cells to the bone marrow and spleen of NOD/SCID and NOD/SCID/B2m(null) mice. Blood 97, 3283–3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hatse S, Princen K, Bridger G, De CE, Schols D (2002) Chemokine receptor inhibition by AMD3100 is strictly confined to CXCR4. FEBS Lett. 527, 255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Christopherson KW, Hangoc G, Mantel CR, Broxmeyer HE (2004) Modulation of hematopoietic stem cell homing and engraftment by CD26. Science 305, 1000–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fukuda S, Bian H, King AG, Pelus LM (2007) The chemokine GRObeta mobilizes early hematopoietic stem cells characterized by enhanced homing and engraftment. Blood 110, 860–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jetmore A, Plett PA, Tong X, Wolber FM, Breese R, Abonour R et al. (2002) Homing efficiency, cell cycle kinetics, and survival of quiescent and cycling human CD34(+) cells transplanted into conditioned NOD/SCID recipients. Blood 99, 1585–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goichberg P, Kalinkovich A, Borodovsky N, Tesio M, Petit I, Nagler A et al. (2006) cAMP‐induced PKCzeta activation increases functional CXCR4 expression on human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors. Blood 107, 870–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Salcedo R, Zhang X, Young HA, Michael N, Wasserman K, Ma WH et al. (2003) Angiogenic effects of prostaglandin E2 are mediated by up‐regulation of CXCR4 on human microvascular endothelial cells. Blood 102, 1966–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Panzer U, Uguccioni M (2004) Prostaglandin E2 modulates the functional responsiveness of human monocytes to chemokines. Eur. J. Immunol. 34, 3682–3689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim CH, Broxmeyer HE (1998) In vitro behavior of hematopoietic progenitor cells under the influence of chemoattractants: stromal cell‐derived factor‐1, steel factor, and the bone marrow environment. Blood 91, 100–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fernandez‐Martinez A, Molla B, Mayoral R, Bosca L, Casado M, Martin‐Sanz P (2006) Cyclo‐oxygenase 2 expression impairs serum‐withdrawal‐induced apoptosis in liver cells. Biochem. J. 398, 371–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. George RJ, Sturmoski MA, Anant S, Houchen CW (2007) EP4 mediates PGE2 dependent cell survival through the PI3 kinase/AKT pathway. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 83, 112–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Negrotto S, Pacienza N, D’Atri LP, Pozner RG, Malaver E, Torres O et al. (2006) Activation of cyclic AMP pathway prevents CD34(+) cell apoptosis. Exp. Hematol. 34, 1420–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fukuda S, Pelus LM (2001) Regulation of the inhibitor‐of‐apoptosis family member survivin in normal cord blood and bone marrow CD34(+) cells by hematopoietic growth factors: implication of survivin expression in normal hematopoiesis. Blood 98, 2091–2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fukuda S, Foster RG, Porter SB, Pelus LM (2002) The antiapoptosis protein survivin is associated with cell cycle entry of normal cord blood CD34(+) cells and modulates cell cycle and proliferation of mouse hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood 100, 2463–2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Baratelli F, Krysan K, Heuze‐Vourc’h N, Zhu L, Escuadro B, Sharma S et al. (2005) PGE2 confers survivin‐dependent apoptosis resistance in human monocyte‐derived dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 78, 555–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Krysan K, Merchant FH, Zhu L, Dohadwala M, Luo J, Lin Y et al. (2004) COX‐2‐dependent stabilization of survivin in non‐small cell lung cancer. FASEB J. 18, 206–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Regan JW (2003) EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptor signaling. Life Sci. 74, 143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lorenz M, Slaughter HS, Wescott DM, Carter SI, Schnyder B, Dinchuk JE et al. (1999) Cyclooxygenase‐2 is essential for normal recovery from 5‐fluorouracil‐induced myelotoxicity in mice. Exp. Hematol. 27, 1494–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pelus LM, Gentile PS (1988) In vivo modulation of myelopoiesis by prostaglandin E2. III. Induction of suppressor cells in marrow and spleen capable of mediating inhibition of CFU‐GM proliferation. Blood 71, 1633–1640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pelus LM (1989) Blockade of prostaglandin biosynthesis in intact mice dramatically augments the expansion of committed myeloid progenitor cells (colony‐forming units‐granulocyte, macrophage) after acute administration of recombinant human IL‐1 alpha. J. Immunol. 143, 4171–4179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]