Abstract

Background and objectives

Research provides skills for lifelong learning and promotes patient care. In Saudi Arabia, until recently, research training has not been integrated effectively in postgraduate medical education. The aim of this study was to investigate the factors involved in research training, productivity, challenges, and attitude among trainees in pediatric residency programs across Saudi Arabia.

Materials and methods

This is a cross-sectional, multicenter study using a questionnaire designed to assess several aspects of research training among trainees of the national pediatric residency program in Saudi Arabia from September to December 2013.

Results

Eighty-three residents from seven training centers participated (response rate of 65.5%). Ninety percent of participants agreed that research training must be mandated in each residency program. The majority of participants (85.5–89.2%) agree that research is beneficial because it improves patient care, enhances the pursuit of academic careers, and improves fellowship acceptance rates and success. More than half (51.8%) of participants believe that research training will interfere with their efforts to become a medical expert in their fields. The survey indicated low research involvement by trainees, with 86.7% of participants having never published scientific manuscripts. The majority of participants (73.5%) reported a lack of regular, structured research activity in their training curriculum. The main challenge in research training was the lack of protected time (according to 86.7% of respondents). The majority of participants (85.6%) agreed that training in research methodologies represents their top educational need.

Conclusion

This study represents a “needs assessment” phase in the development of a research training curriculum for the Saudi pediatric residency program. The majority of participating residents have a positive attitude toward research. Research productivity and training were found to be low. A dedicated research curriculum within the residency program represents an effective and evidence-based solution.

Keywords: Research, Curriculum, Pediatrics, Training, Needs assessment

1. Introduction

Research activity represents an important aspect of residency training by enhancing learning, critical thinking, patient care, and satisfaction with the training program [1], [2], [3], [4]. Experts suggest that properly mentored participation in research, over and above clinical training, has merit during general pediatric residency training [5]. Research competencies have been recognized as one of the key competencies (scholar) in post-graduate medical education [6], [7], [8], [9]. Conducting research during the residency program is a challenge for many reasons related to the trainees themselves, their institutions, and the overall training curriculum [10], [11], [12].

In Saudi Arabia, despite advances in tertiary care and medical education, research activity and training do not meet expectations [13]. In addition, until the time of this study, research training was not sufficiently incorporated into the curricula of medical schools or residency programs. A literature review shows that little is known regarding the research knowledge, attitudes, and practices among trainees of residency programs in Saudi Arabia.

1.1. Aim of the study

The aims of this study were to assess the aspects related to “research” among trainees in “pediatric residency programs” across Saudi Arabia. The aspects investigated, but they are not limited to baseline knowledge and attitudes toward clinical research. In addition, barriers preventing residents from engaging in research were also investigated. Finally, a needs assessment for research curriculum development is presented.

2. Materials and methods

This is a cross-sectional study using a multi-item questionnaire. The study was commenced after obtaining ethical approval from the institutional research advisory committee. The questionnaire consisted of 35 items in five parts: the first part captured demographic data (age, gender, training center and level of training), the second part assessed the attitude of the residents toward research, the third part addressed the challenges in conducting research during residency, the fourth part evaluated the productivity of trainees in research, and the last part assessed the requirements for implementing a proposed research curriculum. The collected questionnaires were entered into a computerized database and analyzed for descriptive outcomes. We targeted seven accredited pediatric residency training centers, which were distributed across the country (four in Riyadh city, one in Dammam city, one in Buraidah city, and one in Abha city) and of different institutional backgrounds (one tertiary, two military, and four Ministry of Health). Hard copies of the questionnaire were distributed and collected by chief residents in each center. The anonymity of participants was maintained to avoid any bias.

3. Results

A total of 83 residents completed the questionnaire with a response rate of 65.5%. The data were obtained from seven pediatric residency training centers across Saudi Arabia. All of these centers are accredited by the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS). Males predominated this population (62.7% male compared to 37.3% female). There was a balanced representation from all different levels of training (R1: 20.5%, R2: 34.9%, R3: 22.9%, and R4: 21.7%) (see Table 1: participants characteristics).

Table 1.

Participants characteristics (training center, gender, and level of training).

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Center | King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre (Riyadh) | 15 | 18.1 |

| Maternity & Children Hospital (Dammam) | 7 | 8.4 | |

| King Saud Medical City (Riyadh) | 10 | 12 | |

| Maternity & Children Hospital (Buraidah) | 6 | 7.2 | |

| Security Forces Hospital (Riyadh) | 10 | 12 | |

| Assir Central Hospital (Abha) | 20 | 24.1 | |

| King Abdulaziz Medical City (Riyadh) | 15 | 18.1 | |

| Gender | Male | 52 | 62.7 |

| Female | 31 | 37.3 | |

| Level of training | First year (R1) | 17 | 20.5 |

| Second year (R2) | 29 | 34.9 | |

| Third year (R3) | 19 | 22.9 | |

| Fourth year (R4) | 18 | 21.7 | |

Ninety percent of participants agreed that research training must be mandated in each residency program. The majority of participants (85.5–89.2%) agreed that research is beneficial because it leads to better patient care, enhances the pursuit of an academic career, and improves fellowship acceptance and success. More than half (51.8%) of trainees believe that research training will interfere with their efforts to become a medical expert in their fields (see Table 2). The main barrier to research training was the lack of protected time according to the majority (88%) of respondents. Other challenges were a lack of research skills and knowledge, a lack of mentorship, a lack of research ideas and a lack of research questions (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Trainees' attitudes toward research.

| Aspects related to trainees' attitudes toward research | Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Disagree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research training should be mandated in any residency training program | 90.4 | 6 | 3.6 |

| Research practice improves patient care | 88 | 9.6 | 2.4 |

| Research practice enhances academic career | 85.5 | 12 | 2.4 |

| Research practice facilitates fellowship acceptance | 89.2 | 3.6 | 7.2 |

| Research training will compromise medical expert competency | 51.8 | 24.1 | 24.1 |

Table 3.

Challenges in pediatric resident's research training.

| Challenges in residents research training | Agree (%) | Disagree (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of protected time | 88 | 12 |

| Lack of research skills and knowledge | 74.4 | 25.6 |

| Lack of mentorship | 61.5 | 38.5 |

| Lack of interest | 34.9 | 65.1 |

| Lack of research ideas | 56.7 | 43.3 |

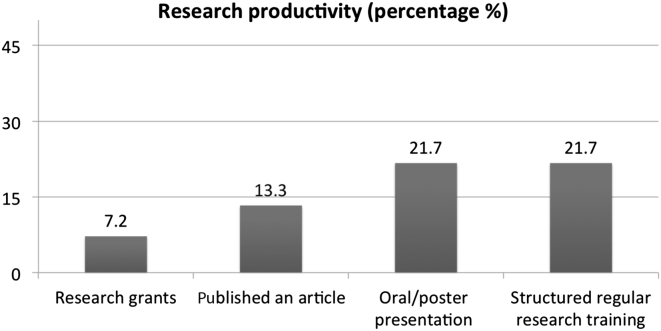

Participants had low levels of research involvement, and 86.7% had never had a scientific publication, 92.8% had never applied for or received a research grant, and 78.3% had never presented an oral or poster research study in a conference. The majority (78.3%) of residents indicated that regular structured activity in their residency program was needed to enhance research training (see Fig. 1). Multivariate analysis did not show any significant impact of the participants' characteristics (gender, training level, and training center) on these results.

Figure 1.

Research productivity during residency training.

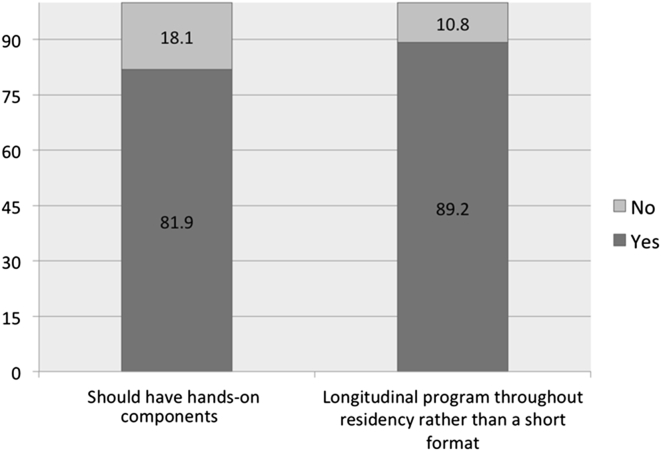

In relation to any proposed research curriculum, the majority (81.9%–89.2%) of participating residents preferred a curriculum with hands-on practice, which also follows a longitudinal format throughout the training program period as opposed to short-term activities (see Fig. 2). The top priority in terms of content to include in the proposed research curriculum was research methodology, followed by literature review and critical appraisal skills, scientific writing skills, biostatistics, research ethics, and epidemiology, all ranked from the highest to lowest priority.

Figure 2.

Suggested research curriculum for the pediatric residency program.

4. Discussion

This study represents a “needs assessment” step in order to support the development of a “research curriculum” for the pediatric residency program in Saudi Arabia. Our results are consistent with those of other investigations in relation to the residents' attitudes toward research training [14], [15], [16]. The majority of the surveyed residents agree that research is beneficial for a variety of aspects. We also found a low level of research involvement among the trainees for several reasons, specifically, a lack of structured regular research activities and a lack of protected time.

Despite these barriers, residents can and do perform research and publish their findings [17]. A survey of residents who presented at the 2002 American College of Physicians (ACP) Annual Session revealed that 44% of residents thought that the absence of a research curriculum was a barrier to completing a research project [18]. Introducing a specific research curriculum has been shown to have positive outcomes, such as increased resident participation in research proposal submissions, conference presentations, manuscript publication, the receipt of research grants, and improved research skills [11], [19], [20], [21]. Such positive impacts were reported upon implementing a resident research curriculum for pediatric residents at the University of Alberta [11]. Compared with the year preceding curriculum implementation, there was an increase in the proportion of residents who had at least one conference presentation, manuscript publication, and an internal or external research grant 2 years after the curriculum initiation. In a systematic review of published resident research curricula, Herbert and colleagues concluded that a lack of detailed developmental information and meaningful evaluation methods were barriers to effective implementation [22]. Positive factors included protected research time, a formal research program including access to biostatisticians and seminars addressing research methodology, exposure to and guidance from mentors, an environment supportive of research and adequate funding to support conference attendance [23]. Based on the available evidence, many pediatric health organizations are promoting research education and recommending support at all levels of pediatric training, from premedical to continuing medical education. They are also recommending to increase support and mentorship for research activities [21].

Some limitations were encountered in this study. In spite of many efforts to increase the response rate of the targeted participants, the achieved rate only slightly exceeded 65%. The use of electronic or web-based survey methods represents an alternative approach, which may improve the response rate. Some survey items might have been subject to recall bias (e.g., research productivity and educational activities), which might be better addressed by reviewing records from the residents' research day and/or an institutional research registry.

Additionally, voluntary response bias cannot be completely excluded, as those interested in research will have higher response rates compared to those who are uninterested. The questionnaire wording was cautiously selected to avoid any source of response bias.

The involvement of faculty members (including program directors) is crucial for ensuring that all stakeholders are considered in the “needs assessment” phase, which will ensure optimum success to any proposed “research curriculum”. This aspect was not addressed in our study.

It is important to mention that the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS) has recently (October 2014) introduced a new curriculum for the pediatric residency program that includes two full blocks dedicated to research training; however, these blocks were not clearly defined. A research curriculum with a full description of learning objectives, teaching methods, and assessment criteria is required. Further studies are needed to address the “needs assessment” input from other stakeholders, namely, faculty members and training directors. The results of the present study can be utilized to facilitate the development and implementation of a research curriculum for the pediatric residency program in Saudi Arabia. Future research will be required to evaluate the impact of such a curriculum and to provide a feedback mechanism for the improvement of curriculum planning and implementation.

5. Conclusion

Our study found a very positive attitude toward research among trainees in the Saudi Pediatric residency program; however, very few trainees have participated in research projects. The lack of protected time and a structured research curriculum were the main barriers limiting residents' involvement in research. Our study supports the integration of a longitudinal hands-on “research curriculum” into the residency program to enhance trainees' scholastic competencies.

Conflict of interest

Authors disclose that there are no conflicts of interests to be disclosed.

Methodology: ethical clearance

The study was commenced after obtaining an ethical approval from the institutional research advisory committee (King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre, RAC # 2131 153).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. Mohamed Shoukri, principal scientist at the King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre (KFSHC&RC), for his assistance in performing the statistical analysis. The authors also would like to thank the trainees of the Saudi pediatric residency program for their participation in this study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre (General Organization), Saudi Arabia.

References

- 1.Abramson M. Improving resident education: what does resident research really have to offer? Trans Sect Otolaryngol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1977;84(6):984–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillman B.J., Fajardo L.L., Witzke D.B., Cardenas D., Irion M., Fulginiti J.V. Factors influencing radiologists to choose research careers. Invest Radiol. 1989;24(11):842–848. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198911000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg L.E. Young physician-scientists: internal medicine's challenge. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(10):831–832. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-10-200011210-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Souba W.W., Tanabe K.K., Gadd M.A., Smith B.L., Bushman M.S. Attitudes and opinions toward surgical research. A survey of surgical residents and their chairpersons. Ann Surg. 1996;223(4):377–383. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199604000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stockman J.A., 3rd Research during residency training: good for all? J Pediatr. 2003;143(5):549–550. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Learning objectives for medical student education–guidelines for medical schools: report I of the Medical School Objectives Project. Acad Med. 1999;74(1):13–18. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199901000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood E., Kronick J.B., Association of Medical School Pediatric Department Chairs, Inc A pediatric residency research curriculum. J Pediatr. 2008;153(2):153–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.02.026. 154e1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albanese M.A., Mejicano G., Mullan P., Kokotailo P., Gruppen L. Defining characteristics of educational competencies. Med Educ. 2008;42(3):248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank J.R., Danoff D. The CanMEDS initiative: implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med Teach. 2007;29(7):642–647. doi: 10.1080/01421590701746983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ullrich N., Botelho C.A., Hibberd P., Bernstein H.H. Research during pediatric residency: predictors and resident-determined influences. Acad Med. 2003;78(12):1253–1258. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200312000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth D.E., Chan M.K., Vohra S. Initial successes and challenges in the development of a pediatric resident research curriculum. J Pediatr. 2006;149(2):149–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill S., Levin A., Djurdjev O., Yoshida E.M. Obstacles to residents' conducting research and predictors of publication. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):477. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alghanim S.A., Alhamali R.M. Research productivity among faculty members at medical and health schools in Saudi Arabia. Prevalence, obstacles, and associated factors. Saudi Med J. 2011;32(12):1297–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitwalli H.A., Al Ghamdi K.M., Moussa N.A. Perceptions, attitudes, and practices towards research among resident physicians in training in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2014;20(2):99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aljadi S.H., Alrowayeh H.N., Alotaibi N.M., Taaqi M.M., Alquraini H., Alshatti T.A. Research amongst physical therapists in the state of Kuwait: participation, perception, attitude and barriers. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22:561–566. doi: 10.1159/000354052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mason A.D., Biehler J.L., Linares M.Y., Greenberg B. Perceptions of pediatric emergency medicine fellows and program directors about research education. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(10):1061–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brouhard B.H., Doyle W., Aceves J., McHugh M.J. Research in pediatric residency programs. Pediatrics. 1996;97(1):71–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivera J.A., Levine R.B., Wright S.M. Completing a scholarly project during residency training. Perspectives of residents who have been successful. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(4):366–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohlwes R.J., Shunk R.L., Avins A., Garber J., Bent S., Shlipak M.G. The PRIME curriculum. Clinical research training during residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):506–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraker L.D., Orsay E.M., Sloan E.P., Bunney E.B., Holden J.A., Hart R.G. A novel curriculum for teaching research methodology. J Emerg Med. 1996;14(4):503–508. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(96)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanna B., Deng C., Erickson S.N., Valerio J.A., Dimitrov V., Soni A. The research rotation: competency-based structured and novel approach to research training of internal medicine residents. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:52. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hebert R.S., Levine R.B., Smith C.G., Wright S.M. A systematic review of resident research curricula. Acad Med. 2003;78(1):61–68. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vinci R.J., Bauchner H., Finkelstein J., Newby P.K., Muret-Wagstaff S., Lovejoy F.H., Jr. Research during pediatric residency training: outcome of a senior resident block rotation. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1126–1134. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]