Abstract

We extracted 15 pterosin derivatives from Pteridium aquilinum that inhibited β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) and cholinesterases involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). (2R)-Pterosin B inhibited BACE1, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) with an IC50 of 29.6, 16.2 and 48.1 µM, respectively. The Ki values and binding energies (kcal/mol) between pterosins and BACE1, AChE, and BChE corresponded to the respective IC50 values. (2R)-Pterosin B was a noncompetitive inhibitor against human BACE1 and BChE as well as a mixed-type inhibitor against AChE, binding to the active sites of the corresponding enzymes. Molecular docking simulation of mixed-type and noncompetitive inhibitors for BACE1, AChE, and BChE indicated novel binding site-directed inhibition of the enzymes by pterosins and the structure−activity relationship. (2R)-Pterosin B exhibited a strong BBB permeability with an effective permeability (Pe) of 60.3×10−6 cm/s on PAMPA-BBB. (2R)-Pterosin B and (2R,3 R)-pteroside C significantly decreased the secretion of Aβ peptides from neuroblastoma cells that overexpressed human β-amyloid precursor protein at 500 μM. Conclusively, our study suggested that several pterosins are potential scaffolds for multitarget-directed ligands (MTDLs) for AD therapeutics.

Subject terms: Alzheimer's disease, Alzheimer's disease, Biologics

Alzheimer’s disease: Promising therapeutic compounds found in plants

Compounds extracted from bracken fern block the activity of three enzymes associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Because AD is a complex and multifactorial disease, a multitarget-directed approach is an attractive strategy for the development of disease-modifying therapeutics. A study led by Gil Hong Park, Korea University, Seoul, and Nam Sook Kang, Chungnam National University, Daejon, revealed that pterosin derivatives could reduce the activity of β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase in a concentration-dependent manner. Furthermore, the fern-extracted compounds did not cause cellular toxicity and were able to cross the blood–brain barrier, which is impermeable to most drugs, to reach the brain. Future studies will determine whether they can be developed into drugs to simultaneously engage various AD targets in animal models of the disease.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an age-related neurodegenerative disorder with characteristic clinical and pathological features, which are associated with the loss of neurons in certain brain areas, leading to memory impairment, cognitive dysfunction, behavioral disturbances, deficits in activities of daily living, and eventually death1,2. The symptoms of AD include dementia, apraxia, aphasia, depression, a short attention span, visuospatial navigation deficits, anxiety, and delusions. AD affects up to 5% of individuals aged above 65 years and increases to 20% in those above 80 years of age. Approximately 46.8 million individuals suffer from AD worldwide, accounting for an estimated annual societal economic cost of $818 billion in 2015, which is expected to increase to $1 trillion in 2018 and $2 trillion in 20303.

Reflecting the multifactorial and complex etiology of AD, the histopathological hallmarks, such as amyloid β-protein (Aβ) deposits4; dysfunctional signaling of acetylcholine (ACh) in certain areas of the brain5; τ protein neurofibrillary tangles6; metabolic pathways, such as those involving cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB)7; oxidative stress8; and inflammation9, appear to play significant roles. The two most common hypotheses include amyloid and cholinergic hypotheses.

The amyloid hypothesis suggests that the accumulation and oligomerization of Aβ peptide in the brain plays a critical role in AD pathogenesis10. It has been clearly established that the overproduction of Aβ by the aspartic protease BACE1 and subsequent oligomerization result in toxic amyloid oligomers inducing neurodegeneration. BACE1 cleaves β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) and forms approximately 90% of the Aβ peptides11,12. Endogenous BACE1 activity is increased in the brain of patients with sporadic AD13. In addition, emerging evidence shows significant elevation of BACE1 in the presence of other AD risk factors, such as traumatic brain injury, stroke, and cardiovascular events, which suggests that BACE1 is a stress-response protein and its activities increase during AD risk factor-related events14. However, all previously discovered natural and synthetic BACE1 inhibitors have failed clinical trials as therapeutic candidates for AD mainly due to adverse effects, such as ocular toxicity15 and poor BBB penetration with low brain:plasma concentration ratios16. Currently, no BACE1 inhibitors have been approved for the clinical treatment of AD.

The cholinergic hypothesis proposes a massive loss of cholinergic neurons as a downstream phenotypic consequence in the pathogenesis of AD1. A decreased level of ACh, a neurotransmitter, in the brain plays a critical role in the progression of AD. ACh plays an important role in the cognitive mechanism and is hydrolyzed by AChE and BChE, leading to the loss of cognitive functions. With the progression of AD, the activity of AChE decreases, while that of BChE increases to compensate for the loss of AChE in an attempt to modulate ACh levels in cholinergic neurons and augment learning17,18. Both enzymes are therapeutic targets to combat cognitive deficits at different stages of AD with AChE in the early stage and BChE in the later stages19. In particular, AChE inhibitors, such as E2020 (donepezil), have become the drug of choice in the clinical management of AD. However, E2020 lacks BACE1-inhibitory activity and fails to provide pathogenetic treatment along with various adverse side effects20.

After several decades of research efforts, the treatment of AD continues to face a significant unmet need, with therapies based largely on the cholinesterase inhibitors rivastigmine, E2020, and galantamine, with the only exception an NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartate) receptor antagonist, memantine21. However, these drugs only relieve AD symptoms for a short period of time without reversing disease progression. In recent years, the need for disease-modifying drugs for AD has been addressed via new approaches to design structures with different targets involved in the pathogenesis of AD, including multitarget-directed ligands (MTDLs), in line with the multifactorial and complex etiology of AD to produce the desired therapeutic efficacy22,23. Thus, MTDLs, such as dual- and multiacting anti-AD agents, represent a promising strategy for the treatment of AD, engaging different targets simultaneously as a hybrid.

Ferns belong to the botanical group Pteridophyta. Several ferns have been used in ethnopharmacy to treat various illnesses24. Alkaloids present in Huperzia serrata, particularly huperzine A, B, and R and 8-β phlegmariurine B, have been used for AD therapy as cholinesterase inhibitors25. Pteridium aquilinum (P. aquilinum) is distributed globally and has been widely consumed traditionally as foods in Korea and Japan. Pterosins, the major components of P. aquilinum, have been reported to be nontoxic to humans, although some of its components, such as the unstable glucoside ptaquiloside, are carcinogenic26,27. Recently, pterosin B was shown to prevent chondrocyte hypertrophy and osteoarthritis in mice at least in part via CREB activation28. In addition, pterosin derivatives, particularly pterosin A, showed pharmacological properties relevant to the prevention and treatment of diabetes and obesity in mice29,30. However, the anti-AD activity of pterosins has not been reported to date.

The present study was performed to characterize the anti-AD potential of pterosin derivatives by investigating their activities in vitro to inhibit BACE1, AChE and BChE as well as BBB permeability. In addition, the structure−activity relationship (SAR) was analyzed using molecular docking simulations to determine the molecular interactions between pterosins and the active sites of BACE1, AChE and BChE.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

BACE1 (human recombinant β-secretase) (EC 3.1.1.8) and the BACE1 FRET (fluorescence resonance energy transfer) assay kit Red were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (P2985; Waltham, MA, USA). Electric eel AChE (EC3.1.1.7), horse serum BChE (EC 3.1.1.8), acetyl thiocholine iodide, butyryl thiocholine chloride, 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), quercetin, berberine, and the MTT assay kit were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). For the cell culture experiment, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), Opti-MEM, fetal bovine serum (FBS), and penicillin/streptomycin were obtained from Capricorn Scientific (Ebsdorfergrund, Germany). β-secretase inhibitor III (β-SI) was purchased from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). The protease inhibitor mixture (a mixture of AEBSF, pepstatin A, E-64, bestain, leupeptin, and aprotinin) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for Aβ40 and Aβ42 were obtained from IBL (Kunma, Japan). All chemicals and solvents used were reagent grade, purchased from commercial sources, and used as received.

Plant material

P. aquilinum was collected from the mountainous regions of Gapyeong-gun, Gyeonggido, Korea, and authenticated by Prof. Ki-Joong Kim (Korea University, Seoul). A voucher specimen was deposited in the laboratory of Prof. Gil Hong Park.

Extraction, fractionation, and identification of pterosin derivatives from P. aquilinum

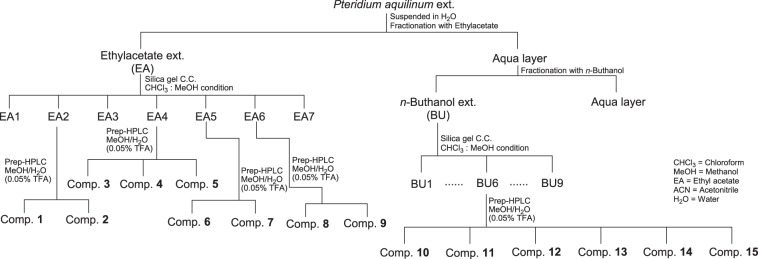

Pterosin derivatives were isolated from P. aquilinum using hot water followed by various chromatographic methods (Fig. 1). The hot water extract obtained by refluxing 250 g of the whole plants of P. aquilinum in 1.5 L H2O for 24 h in a steamer (OSK-2002, Red Ginseng Doctor, Well sosanaTM, Daewoong Pharmaceutical, Seoul, Korea) was initially partitioned with an equal volume of EtOAc and subsequently with n-BuOH. The repeated column chromatographic separation of the EtOAc-soluble fraction and the n-BuOH-soluble fraction resulted in the isolation of 15 pterosin derivatives with purities greater than 97%. The structures of the isolated compounds were identified via analysis of the spectral data, including MS, 1D- and 2D-NMR, as well as comparison of their data with the published values, including heteronuclear single quantum correlation and heteronuclear multiple bond correlation. The pterosin compounds were dissolved in Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) for use in the experiment.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart to illustrate the process to isolate and purify pterosin derivatives from Pteridium aquilinum

In vitro BACE1 enzyme assay

The BACE1 FRET assay was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions with slight modifications as previously described31. The assay was performed in a 381-well black plate using a multi-pipette. Readings were obtained two times, the first time at 0 min and the second time after 60 min incubation at room temperature (26 °C) and stopping the reaction with BACE1 stop buffer, using a spectrofluorometer (Gemini EM; Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) at 545 nm (excitation) and 590 nm (emission). Quercetin was used as the positive control. % Inhibition calculation: [1 – (60 min value - 0 min value/control)] × 100.

In vitro cholinesterase enzyme assay

The inhibitory activities of pterosin derivatives against cholinesterases were measured using the method developed by Ellman et al.32. The reaction mixture contained 140 μL of sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), 20 μL of test sample solution (final concentration of the compound 100 μM), and 20 μL of AChE or BChE solution, mixed and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. All test samples and the positive control (berberine) were diluted or dissolved in 10% analytical grade ethanol. The reactions were initiated following the addition of 10 μL of DTNB and 10 μL of acetyl thiocholine iodide for the AChE assay or butyryl thiocholine chloride for the BChE assay in 96-well microplates, which were incubated for 15 min. The hydrolysis of acetyl thiocholine iodide or butyryl thiocholine chloride was monitored by tracking the formation of yellow 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoate anion resulting from the reaction between DTNB and thiocholine released by the enzyme, using a microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 412 nm. The percent inhibition was calculated as (1−S/E) × 100, where S and E represent the enzyme activities with and without the test sample, respectively.

Kinetic parameters of BACE1, AChE and BChE inhibition by pterosin derivatives and the inhibition mechanism

To determine the Ki and the mode of enzymatic inhibition of the most active compounds against BACE1, AChE, and BChE, Dixon and Lineweaver−Burk plots were employed. The Ki was determined by interpretation of the Dixon plot, with the value of the x-axis intercept taken as −Ki. The Dixon plot is a graphical method [plot of 1/enzyme velocity (1/V) against inhibitor concentration (I)] for the determination of Ki and the type of enzyme inhibition for the enzyme–inhibitor complex. Dixon plots for enzyme inhibition by pterosins were tested in the presence of different substrate concentrations: 150, 250, and 750 nM for BACE1, 100, 300, and 600 µM for AChE, and 200, 400, and 800 µM for BChE. Lineweaver−Burk plots were analyzed in the presence of different inhibitor concentrations: 0–125 µM for BACE1, 0–100 µM for AChE, and 0–150 µM for BChE.

Molecular docking

Docking studies were performed on BACE1, AChE, and BChE to understand the inhibition profile of the pterosin derivatives. The X-ray crystal structures of human BACE1 complexed with 2-amino-3-{(1r)-1-cyclohexyl-2-[(cyclohexylcarbonyl)amino]ethyl}-6-phenoxyquinazolin-3-ium (QUD) (PDB code: 2WJO)33, human AChE complexed with E2020 (PDB code: 4EY7)34 and human BChE complexed with N-{[(3R)-1-(2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-2-yl)piperidin-3-yl]methyl}-N-(2-methoxyethyl)naphthalene-2-carboxamide (3F9) (PDB code: 4TPK)35 were retrieved from the RCSB Protein Databank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/). Discovery Studio 2017 R2 (BIOVIA, San Diego: Dassault Systèmes) was used to create 3D structures of the docked ligands and for energy minimization. Docking studies were carried out using AutoDock 4.2.6 software36. Protein structures were held rigid, whereas ligands were treated as fully flexible during docking. Prior to docking, the protein and ligand structures were processed with AutoDock Tools (ADT) 1.5.637. The cocrystallized ligands and water molecules were removed from the original PDBs. Polar hydrogen atoms were merged, and Kollman and Gasteiger charges were assigned to the protein structures. Gasteiger charges were added by default to the ligands for docking calculations. The number of rotatable bonds was set, and all torsions were allowed to rotate. For each enzyme, the AutoGrid program was employed to create a grid box of size 60 × 60 × 60 Å3 with 0.375 Å spacing. The center of the grid was defined according to a recent study, which reported different sites for catalytic, mixed-type and noncompetitive BACE1, AChE, and BChE inhibitors38. Lamarckian genetic algorithm was used for the conformational search39. The docking protocol consisted of 100 runs, 25×105 energy evaluations and 27,000 iterations. Other docking parameters were set to the default values. Docked poses were selected on the basis of scoring functions and protein−ligand interactions. Binding interaction figures were generated using Discovery Studio 2017 R2.

PAMPA-BBB procedure

PAMPA (parallel artificial membrane permeation assay) was used as a high-throughput assay to predict BBB permeation40. Porcine polar brain lipid (PBL) was used as an artificial membrane to predict BBB permeation. Initially, the test compound was dissolved in DMSO at 5 mg/mL. This compound stock solution (10 µL) was diluted 200-fold in a universal buffer at pH 7.4 and mixed with a multi 8-channel pipette to obtain the secondary stock solution (final concentration 25 µg/mL). The secondary stock solution (200 µL) was placed in the donor wells. The filter membrane was coated with PBL in dodecane (4 mL volume of 20 mg/mL PBL in dodecane), and 5 µL of BBB-1 lipid solution was spread on PBL by pipette. The acceptor well was filled with 200 mL of Acceptor Sink Buffer. The acceptor filter plate was cautiously positioned on the donor plate to assemble a “sandwich” (comprising an aqueous acceptor, artificial lipid membrane and aqueous donor with test compound on the top, middle and bottom, respectively). The test compound diffuses from the donor well to the acceptor well through the lipid membrane. After 4 h of incubation at pH 7.4 and 25 °C, the concentration of the compound in the acceptor, donor, reference and blank wells was estimated with a UV plate reader, Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). The effective permeability (Pe) of the compounds was calculated using Pion PAMPA Explorer software. Samples were analyzed in quadruplets, and the average of the four runs was reported. To monitor the consistency of the analysis set, quality control standards were run with each sample set. Verapamil was employed as a high permeability standard (Pe = 16 × 10−6 cm/s).

Cell culture and treatment

Mouse neuroblastoma N2a cells stably overexpressing the human APP Swedish mutation (APPswe) were kindly provided by Dr. Takeshi Iwatsubo (The University of Tokyo). The cells were cultured in 45% DMEM, 55% opti-MEM, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% glutamine and 0.09% hygromycin B (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. To analyze the effect of (2R)-pterosin B or (2R,3R)-pteroside C on APP metabolites, APPswe-containing neuroblastoma cells were cultured up to confluency in DMEM that contained 10 mM butyric acid to drive protein expression in the presence of 12, 60, 250, and 500 μM of (2R)-pterosin B or (2R,3R)-pteroside C for 24 h. β-SI (10 µM) was used as a positive control. The negative control included cells cultured in the absence of test compounds. Cells were lysed in immunoprecipitation buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA), 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with the protease inhibitor mixture. Conditioned medium was collected in 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and subjected to ELISA for the 40-residue peptide Aβ (1–40) (Aβ40) or the 42-residue Aβ (1–42) (Aβ42).

Aβ ELISA

Aβ40 and Aβ42 ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The assay was conducted in a microplate coated with anti-human Aβ35-40 mouse IgG (1A10) or anti-human Aβ38-42 mouse IgG (44A3), respectively. The microplate was added with 100 μL conditioned media, incubated overnight at 4 °C, and then washed with washing buffer. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-human Aβ11-28 mouse IgG (82E1) was added into each well, incubated at 4 °C for 1 h, and washed with washing buffer. 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine as a chromogenic substrate was added to each well and incubated for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μL stop solution, and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a model 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

Cytotoxicity was assessed using the MTT assay41. Briefly, the cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 1×105 cells per well in 100 µL of corresponding media and incubated at 37 °C in an incubator under 5% CO2 tension for 24 h. The culture media were then replaced with 100 µL of fresh serum-free media in the presence of varied concentrations of pterosin derivatives, and cells were incubated for an additional 24 h. The control was treated with an equal amount of DMSO present in the assay for a 5 mM concentration. Then, 100 µL of MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)) was added to each culture. To measure the proportion of surviving cells, the media were replaced with 100 µL of DMSO 2 h after the administration of MTT solution. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a spectrophotometric plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate or quadruple experiments. Statistical evaluation was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism 5.01 (Graph Pad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Isolation and characterization of pterosin derivatives from P. aquilinum

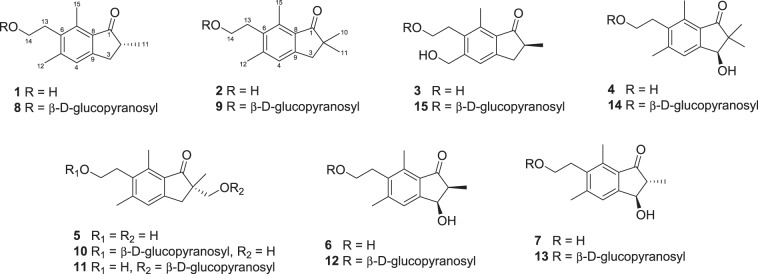

Pterosin derivatives were isolated from the whole plants of P. aquilinum. For the investigation of the phytochemical constituents from the bracken fern, a water extract was successively partitioned with ethyl acetate (EtOAc) and n-butanol (n-BuOH) (Fig. 1). Repeated column chromatography of the EtOAc-soluble fraction resulted in the isolation of nine derivatives, including (2R)-pterosin B (1), pterosin Z (2), (2S)-pterosin P (3), (3R)-pterosin D (4), (2S)-pterosin A (5), (2S,3R)-pterosin C (6), (2R,3R)-pterosin C (7), (2R)-pteroside B (8), and pteroside Z (9), with purities greater than 97% (Fig. 2). The repeated column chromatographic separation of the n-BuOH-soluble fraction resulted in the isolation of six derivatives, including (2S)-pteroside A (10), (2S)-pteroside A2 (11), (2S,3R)-pteroside C (12), (2R,3R)-pteroside C (13), (3S)-pteroside D (14), and (2S)-pteroside P (15), with purities greater than 97%. The structures of the compounds were identified by the analysis of spectral data, including MS, 1D- and 2D-NMR (Supplementary Information 1).

Fig. 2.

Structures of pterosin compounds 1–15xxx

Inhibitory activity of pterosin derivatives against BACE1, AChE, and BChE

To evaluate the anti-AD potential, the inhibitory activity of each pterosin compound against BACE1 and cholinesterases was evaluated by respective in vitro inhibition assays (Table 1). All tested pterosin derivatives showed concentration-dependent inhibitory activities against BACE1 with a range of IC50 values (half-maximum inhibitory concentration) of 9.74–94.4 μM, with the exception of (2S)-pterosin A and (2S)-pteroside P that were inactive at the concentrations tested, compared with the IC50 of quercetin used as the positive control, which was 18.8 μM. The inhibitory potency of the strongest inhibitors was in the order of (2R,3R)-pteroside C, (3S)-pteroside D, (2R)-pteroside B, (2S,3R)-pterosin C, (2R,3R)-pterosin C, (2S,3R)-pteroside C, and (2R)-pterosin B with IC50 values of 9.74, 10.7, 18.0, 23.1, 26.2, 28.9, and 29.6 μM, respectively. We subsequently tested the inhibitory potentials of the pterosin derivatives against AChE. All the tested compounds showed significant AChE-inhibitory activities, with IC50 values in the range of 2.55–110 μM, compared with the IC50 against AChE of berberine used as the positive control, which was 0.39 μM. The pterosin compounds that displayed the strongest inhibitory activity against AChE were (2R)-pteroside B, (2R,3R)-pteroside C, (2S,3R)-pteroside C, (2S,3R)-pterosin C, and (2R)-pterosin B with IC50 values of 2.55, 3.77, 9.17, 12.8, and 16.2 μM, respectively. Finally, we tested the inhibitory capacities of the pterosin derivatives against BChE. All the pterosin compounds tested showed inhibitory activity against BChE, with IC50 values that ranged from 5.29 to 119 μM, with the exception of (3R)-pterosin D that was inactive at the concentrations tested, compared with the IC50 of berberine against BChE, which was 3.32 μM. The pterosin compounds that displayed the strongest inhibitory activity against BChE were (2R,3R)-pteroside C and pteroside Z with IC50 values of 5.29 and 5.31 μM, respectively.

Table 1.

IC50 of pterosin derivatives against BACE1, AChE, and BChE

| Compounds | IC50 (µM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BACE1 | AChE | BChE | |

| (2S)-Pterosin A | >125 | 56.7 ± 2.6 | 67.3 ± 3.3 |

| (2R)-Pterosin B | 29.6 ± 3.5 | 16.2 ± 1.0 | 48.1 ± 0.59 |

| (2S,3R)-Pterosin C | 23.1 ± 2.9 | 12.8 ± 0.79 | 44.3 ± 1.0 |

| (2R,3R)-Pterosin C | 26.2 ± 6.3 | 23.2 ± 4.6 | 20.3 ± 0.88 |

| (3R)-Pterosin D | 92.5 ± 7.0 | 68.7 ± 3.7 | >125 |

| (2S)-Pterosin P | 67.1 ± 7.7 | 17.8 ± 0.62 | 55.9 ± 5.6 |

| Pterosin Z | 80.0 ± 5.9 | 46.5 ± 3.4 | 80.1 ± 6.8 |

| (2S)-Pteroside A | 84.6 ± 6.0 | 110 ± 3.0 | 19.4 ± 0.22 |

| (2S)-Pteroside A2 | 94.4 ± 4.5 | 39.3 ± 1.9 | 119 ± 2.5 |

| (2R)-Pteroside B | 18.0 ± 2.8 | 2.55 ± 0.23 | 62.0 ± 0.71 |

| (2S,3R)-Pteroside C | 28.9 ± 2.2 | 9.17 ± 0.82 | 13.0 ± 0.14 |

| (2R,3R)-Pteroside C | 9.74 ± 1.9 | 3.77 ± 0.38 | 5.29 ± 0.82 |

| (3S)-Pteroside D | 10.7 ± 1.5 | 27.4 ± 1.2 | 19.3 ± 0.17 |

| (2 )-Pteroside P | >125 | 57.5 ± 3.2 | 33.2 ± 3.0 |

| Pteroside Z | 53.3 ± 1.2 | 24.1 ± 1.1 | 5.31 ± 0.19 |

| Quercetina | 18.8 ± 1.0 | ||

| Berberineb | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 3.32 ± 0.12 | |

IC50 values (µM) are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of three experiments

BACE1 β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1, AChE acetylcholinesterase, BChE butyrylcholinesterase

aQuercetin and bberberine were used as positive controls for the BACE1, AChE, and BChE assays, respectively

Collectively, most of the pterosin derivatives tested exhibited significant inhibitory activities against BACE1, AChE, and BChE simultaneously. The presence of the additional 2-hydroxymethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-3,4,5-triol group as in pteroside derivatives significantly increased the inhibitory activities against the enzymes. Moreover, the presence of the additional hydroxymethyl group at position-2 of the indanone ring of (2R)-pterosin B as in (2S)-pterosin A or the methyl group as in (3R)-pterosin D and pterosin Z decreased the inhibitory activities against the enzymes. In particular, the presence of the hydroxymethyl group at position-5 of the indanone ring as in (2S)-pterosin P decreased the inhibitory activity against BACE1.

Kinetic parameters of enzyme inhibition by pterosin derivatives

In an attempt to explain the mode of enzymatic inhibition of pterosin derivatives, we performed a kinetic analysis of BACE1 and cholinesterases for representative inhibitors (Table 2, Supplementary Information 2). A low Ki (inhibition constant) indicates tighter enzyme binding and a more effective inhibitor. Overall, the Ki values of the compounds correlated with the respective IC50 values. BACE1 inhibition by the compounds (2R,3R)-pteroside C, (3S)-pteroside D, and (2R,3R)-pterosin C was mixed-type with Ki values of 12.6, 16.5, and 27.6 µM, respectively, while inhibition by (2R)-pteroside B, (2S,3R)-pterosin C, and (2R)-pterosin B was noncompetitive with Ki values of 23.1, 33.8, and 38.3 µM, respectively. AChE inhibition by (2R)-pteroside B, (2R,3R)-pteroside C, (2R)-pterosin B, (2S,3R)-pterosin C, and (3S)-pteroside D was mixed-type with Ki values of 4.89, 8.13, 12.1, 16.3, and 23.1 µM, respectively, while (2R,3R)-pterosin C was a noncompetitive type inhibitor with a Ki value of 29.6 µM. BChE inhibition by (2R,3R)-pterosin C, (2R,3R)-pteroside C, (3S)-pteroside D, and (2R)-pteroside B was mixed-type with Ki values of 4.77, 9.62, 19.7, and 22.6 µM, respectively, while (2S,3R)-pterosin C and (2R)-pterosin B were noncompetitive inhibitors with Ki values of 29.9 and 53.5 µM, respectively. Thus, these results suggested that specific pterosin derivatives might be effective BACE1, AChE, and BChE inhibitors.

Table 2.

Enzyme kinetics of pterosin derivatives based on Dixon plot and Lineweaver−Burk plot

| Compounds | Ki and inhibition type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BACE1 | AChE | BChE | ||||

| Ki (µM)a | Inhibition typeb | Ki (µM)a | Inhibition typeb | Ki (µM)a | Inhibition typeb | |

| (2R)-Pterosin B | 38.3 | Noncompetitive | 12.1 | Mixed-type | 53.5 | Noncompetitive |

| (2S,3R)-Pterosin C | 33.8 | Noncompetitive | 16.3 | Mixed-type | 29.9 | Noncompetitive |

| (2R,3R)-Pterosin C | 27.6 | Mixed-type | 29.6 | Noncompetitive | 4.77 | Mixed-type |

| (2R)-Pteroside B | 23.1 | Noncompetitive | 4.89 | Mixed-type | 22.6 | Mixed-type |

| (2R,3R)-Pteroside C | 12.6 | Mixed-type | 8.13 | Mixed-type | 9.62 | Mixed-type |

| (3S)-Pteroside D | 16.5 | Mixed-type | 23.1 | Mixed-type | 19.7 | Mixed-type |

BACE1 β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1, AChE acetylcholinesterase, BChE butyrylcholinesterase

aDetermined by Dixon plot

bDetermined by Dixon and Lineweaver−Burk plots (Supplementary Information 2)

Molecular docking simulations for BACE1, AChE, and BChE

Several crystal structures are available for BACE1 and cholinesterases. We selected human PDBs based on wild-type structures, cocrystallized ligands and resolutions of the structures. X-ray crystal structures of BACE1 complexed with QUD (PDB code: 2WJO, resolution: 2.5 Å)33, AChE complexed with E2020 (PDB code: 4EY7, resolution: 2.35 Å)34, and BChE complexed with 3F9 (PDB code: 4TPK, resolution: 2.70 Å)35 were selected for docking. Initially, QUD, E2020, and 3F9 were extracted from crystal structures and redocked into the active sites of BACE1, AChE, and BChE, respectively. Subsequently, (2R,3R)-pteroside C, (3S)-pteroside D, (2R,3R)-pterosin C, (2R)-pteroside B, (2S,3R)-pterosin C and (2R)-pterosin B with the known mechanism of inhibition against BACE1, AChE and BChE were docked to determine their SAR. The docking results are summarized in Table 3. The SAR of the selected mixed-type and noncompetitive BACE1, AChE, and BChE inhibitors enabled the evaluation of novel binding site-directed inhibition of the enzymes by pterosins.

Table 3.

Docking affinity scores and possible H-bond formation to the corresponding active sites of BACE1, AChE, and BChE by pterosin derivatives along with reported inhibitors

| Compounds | Target enzymes | B.E. (kcal/mol)a | H-bonds interacting residues | Hydrophobic interacting residues | Other interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QUDb | BACE1 | –7.59 | Asp32, Asp228, Gly230 | Leu30, Tyr71, Phe108, Val332 | |

| E2020b | AChE | –10.28 | Phe295 | Trp86, Trp286, Tyr337, Phe338, Tyr341 | Trp286, Tyr341 (π-sigma) |

| 3F9b | BChE | –8.49 | Ile69, Gly116, Trp231, Leu286, Ala328, Phe329, Tyr332 | Asp70 (π-anion) | |

| (2R,3R)-Pteroside C | BACE1 | –7.27 | Ser36, Asn37, Asp228, Thr231 | Ala39, Val69, Trp76, Ile118, Arg128 | Val69 (π-sigma) |

| AChE | –7.49 | Trp86, Asn87, Tyr124 | Tyr72, Tyr124, Trp286, Tyr337, Phe338 | ||

| BChE | –7.23 | Gly78, Ser287, Tyr440 | Trp82, Phe329, Tyr332, Trp430, His438 | ||

| (3S)-Pteroside D | BACE1 | –6.93 | Ser36, Asn37, Ile126, Asp228 | Val69, Tyr71, Trp76, Arg128 | |

| AChE | –4.91 | Tyr72, Asp74 | Tyr72, Tyr124, Trp286, Phe297, Phe338, Tyr341 | Trp286 (π-sigma) | |

| BChE | –6.59 | Trp82, Ser287 | Ala328, Phe329, Tyr332, Trp430, Met437, His438 | ||

| (2R,3R)-Pterosin C | BACE1 | –4.84 | Ser36, Asn37 | Ala39, Val69, Trp76, Ile118, Arg128 | Val69 (π-sigma) |

| AChE | –5.01 | Tyr72, Ser293 | Tyr72, Trp286, Phe297, Tyr341 | ||

| BChE | –6.52 | Gly78, Gly117, Tyr440 | Trp82, Phe329, Tyr332, Trp430, His438 | ||

| (2R)-Pteroside B | BACE1 | –6.16 | Asn37, Trp76, Ile126 | Val69, Tyr71, Phe108 | |

| AChE | –7.90 | Trp86, Asn87, Tyr124 | Tyr72, Tyr124, Trp286, Tyr337, Phe338, Tyr341 | ||

| BChE | –4.38 | Ser287 | Trp82, Phe329, Tyr332, Trp430, His438 | ||

| (2S,3R)-Pterosin C | BACE1 | –5.07 | Lys107 | Val69, Tyr76, Lys107, Phe108 | |

| AChE | –6.03 | Tyr124, Phe295 | Tyr72, Tyr124, Trp286, Tyr337, Phe338, Tyr341 | ||

| BChE | –5.40 | Gly283, Asn397 | Leu286, Val288, Phe357 | ||

| (2R)-Pterosin B | BACE1 | –4.64 | Val69, Tyr76, Phe108 | ||

| AChE | –5.76 | Tyr124 | Tyr124, Trp286, Tyr337, Phe338, Tyr341 | ||

| BChE | –5.06 | Gly283 | Leu286, Val288, Phe357 |

B.E. binding energy, BACE1 β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1, AChE acetylcholinesterase, BChE butyrylcholinesterase

aEstimated the binding free energy of the ligand receptor complex

bPositive control ligands

Our docking mode of E2020 was consistent with the experimentally determined binding mode previously reported with recombinant human AChE (rhAChE) (Supplementary Information 3)34. The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the crystal and docked conformations of E2020 was 0.54 Å, which suggested the reliability of our docking setup in reproducing the experimental binding mode. In addition, the docked mode of E2020 led to a similar interaction as that of rhAChE-E2020. In our study, water molecules were removed from the crystal structure during docking; therefore, water-mediated interactions were not analyzed in the present study. Similarly, the docked modes of QUD and 3F9 were consistent with the available experimental data for BACE1 33 and BChE35, respectively (Supplementary Information 3). The RMSDs between the crystal and docked conformations of QUD and 3F9 were 0.46 and 0.60 Å, respectively. Further, the binding sites of pterosin inhibitors were in agreement with a previous docking study that involved BACE1, AChE, and BChE38. However, the study used Tetronarce californica AChE (PDB code: 1ACJ), which contains slightly different residue numbers than human AChE due to variations in their sequences.

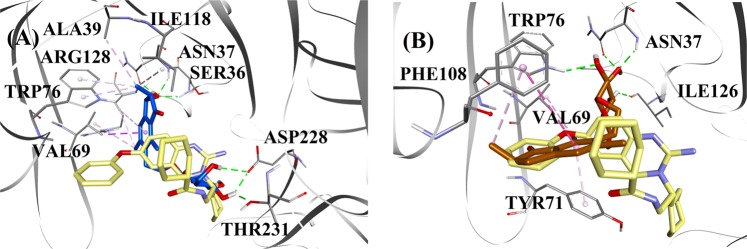

BACE1 docking

Based on the inhibition type and activity, (2R,3R)-pteroside C and (2R)-pteroside B were selected to demonstrate the docked modes of mixed-type and noncompetitive BACE1 inhibitors, respectively. Figure 3a, b displays the docking models of (2R,3R)-pteroside C and (2R)-pteroside B, respectively. The interactions of the docked compounds inside the active site of BACE1 are shown in Fig. 4.

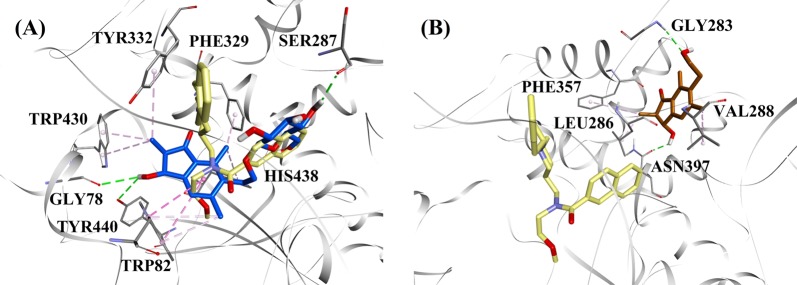

Fig. 3. Molecular docking models for the mixed-type and the noncompetitive BACE1 inhibitors.

Molecular docking models for a the mixed-type BACE1 inhibitor (2R,3R)-pteroside C (blue color) and b the noncompetitive BACE1 inhibitor (2R)-pteroside B (brown color). Docked poses are superimposed on the X-ray crystal structure of QUD (yellow color) (PDB code: 2WJO). BACE1, active site residues and compounds are shown by ribbon, line and stick models, respectively. Colors of the dotted lines explain the types of various interactions: hydrogen bonding interactions (green), hydrophobic interactions (pink) and π-sigma interactions (purple). BACE1 β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1

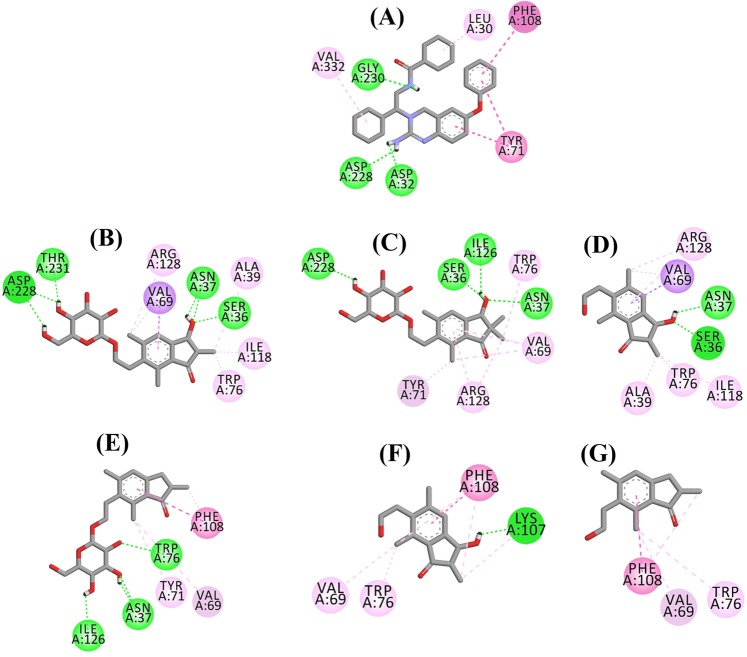

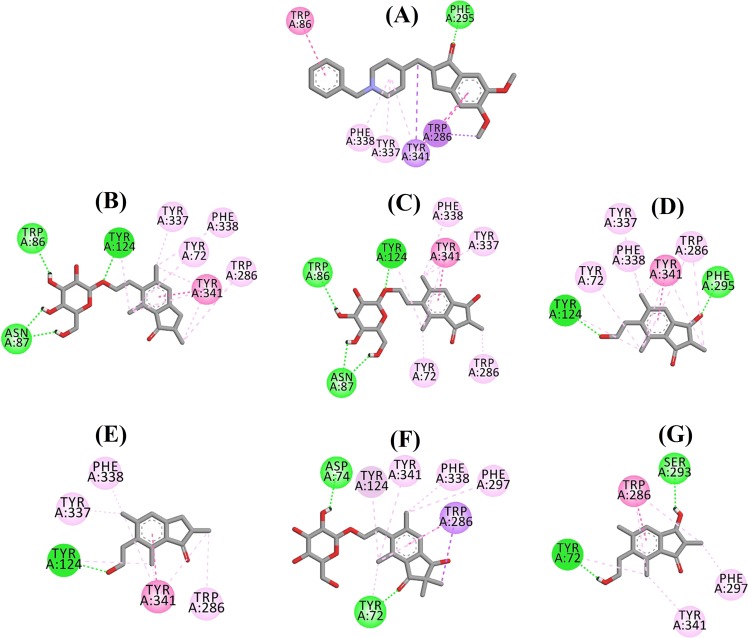

Fig. 4. Ligand interaction diagram of BACE1 inhibitors in the active site.

Ligand interaction diagram of a QUD, b (2R,3R)-pteroside C, c (3S)-pteroside D, d (2R,3R)-pterosin C, e (2R)-pteroside B, f (2S,3R)-pterosin C, and g (2R)-pterosin B in the active site of BACE1. Colors of the dotted lines explain the types of various interactions: hydrogen bonding interactions (green), hydrophobic interactions (pink) and π-sigma interactions (purple). BACE1 β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1

The docked pose of QUD exhibited a binding energy (B.E.) of −7.59 kcal/mol. As shown in Fig. 4a, the NH2 group on the quinazoline ring of the ligand showed two hydrogen bonds with the CO groups of Asp32 and Asp228 at distances of 1.86 and 2.17 Å, respectively. A third hydrogen bond was observed between the other NH group of the ligand and the CO group of Gly230 at a distance of 2.16 Å. Leu30, Tyr71, Phe108, and Val332 mediated the hydrophobic interactions. Figure 4b−d displays the docked poses of (2R,3R)-pteroside C, (3S)-pteroside D and (2R,3R)-pterosin C (mixed-type BACE1 inhibitors), respectively. They were positioned in the binding pocket lined by Ser36, Asn37, Ala39, Val69, Tyr71, Trp76, Ile118, Ile126, Arg128, Asp228, and Thr231. As per their activity levels, (2R,3R)-pteroside C (IC50 = 9.74 µM), (3S)-pteroside D (IC50 = 10.7 µM) and (2R,3R)-pterosin C (IC50 = 26.2 µM) exhibited a B.E. of −7.27, −6.93, and −4.84 kcal/mol, respectively. (2R,3R)-Pteroside C exhibited a higher potency than (2R,3R)-pterosin C due to the existence of an additional 2-hydroxymethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-3,4,5-triol group, which formed three hydrogen bonds (Fig. 4b). The OH group of hydroxymethyl and the 3-OH group of the tetrahydro-pyran-triol ring showed two hydrogen bonds with the CO group of Asp228 at distances of 2.63 and 2.12 Å, respectively. Additionally, the 3-OH group demonstrated a hydrogen bond with Thr231 at a distance of 1.89 Å. In the case of (3S)-pteroside D (Fig. 4c), the presence of the 2,2-dimethyl group at the indanone ring slightly altered the binding interactions compared with (2R,3R)-pteroside C. The 3-OH group of the tetrahydro-pyran-triol ring showed only a single hydrogen bond with Asp228 at a distance of 1.93 Å. However, the 3-OH group of the indanone ring exhibited an additional hydrogen bond with Ile126 at a distance of 2.34 Å. These interactions slightly lowered the activity of (3S)-pteroside D compared with (2R,3R)-pteroside C. The docking interactions of (2R,3R)-pterosin C displayed in Fig. 4d show the 3-OH group of the indanone ring bound to Ser36 and Asn37 via two hydrogen bonds at distances of 1.83 and 2.07 Å, respectively. Ala39, Val69, Trp76, Ile118, and Arg128 were involved in hydrophobic interactions, while Val69 displayed a π-sigma interaction.

The docked poses of (2R)-pteroside B, (2S,3R)-pterosin C, and (2R)-pterosin B (noncompetitive BACE1 inhibitors) are shown in Fig. 4e−g, respectively. They were docked into the cavity enclosed by Asn37, Val69, Tyr71, Trp76, Lys107, Phe108, and Ile126. In accordance with their activity values, (2R)-pteroside B (IC50 = 18.0 µM), (2S,3R)-pterosin C (IC50 = 23.1 µM), and (2R)-pterosin B (IC50 = 29.6 µM) exhibited a B.E. of −6.16, −5.07, and −4.64 kcal/mol, respectively. As displayed in Fig. 4e, (2R)-pteroside B demonstrated higher activity than (2S,3R)-pterosin C and (2R)-pterosin B due to the presence of an additional 2-hydroxymethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-3,4,5-triol group, which showed four hydrogen bond interactions. Two hydrogen bonds were observed between the 4-OH group of the tetrahydro-pyran-triol ring and the NH and CO groups of Asn37 at distances of 2.48 and 2.19 Å, respectively. Further, the 3- and 5-OH groups showed two additional hydrogen bonds with Ile126 and Trp76 at distances of 2.19 and 2.46 Å, respectively. (2S,3R)-Pterosin C showed slightly better activity than (2R)-pterosin B due to the presence of an additional OH group at position-3 of the indanone ring, which formed a hydrogen bond with Lys107 at a distance of 2.12 Å (Fig. 4f). The other interactions were similar to those of (2R)-pterosin B. As displayed in Fig. 4g, (2R)-pterosin B showed hydrophobic interactions with Val69, Tyr76, and Phe108.

AChE docking

(2R)-Pteroside B and (2R,3R)-pterosin C were selected as representatives to demonstrate the docked modes of mixed-type and noncompetitive AChE inhibitors, respectively, due to their activities and type of AChE inhibition. Figure 5a, b illustrates the docking models of (2R)-pteroside B and (2R,3R)-pterosin C, respectively. The interactions of the docked compounds inside the active site of AChE are displayed in Fig. 6.

Fig. 5. Molecular docking models for the mixed-type and the noncompetitive AChE inhibitors.

Molecular docking models for a the mixed-type AChE inhibitor (2R)-pteroside B (blue color) and b the noncompetitive AChE inhibitor (2R,3R)-pterosin C (brown color). Docked poses are superimposed on the X-ray crystal structure of E2020 (yellow color) (PDB code: 4EY7). AChE, active site residues and compounds are shown by ribbon, line and stick models, respectively. Colors of the dotted lines explain the types of various interactions: hydrogen bonding interactions (green) and hydrophobic interactions (pink). AChE acetylcholinesterase

Fig. 6. Ligand interaction diagram of AChE inhibitors in the active site.

Ligand interaction diagram of a E2020, b (2R)-pteroside B, c (2R,3R)-pteroside C, d (2S,3R)-pterosin C, e (2R)-pterosin B, f (3S)-pteroside D and g (2R,3R)-pterosin C in the active site of AChE. Colors of the dotted lines explain the types of various interactions: hydrogen bonding interactions (green), hydrophobic interactions (pink) and π-sigma interactions (purple). AChE acetylcholinesterase

The docked pose of E2020 demonstrated a B.E. of −10.28 kcal/mol. As illustrated in Fig. 6a, the CO group of the indanone ring formed a hydrogen bond with the NH group of Phe295 at a distance of 1.70 Å. Trp286 and Tyr341 were involved in π-sigma interactions, whereas Trp86, Trp286, Tyr337, Phe338, and Tyr341 mediated hydrophobic interactions. Figure 6b−f demonstrates the docked poses of (2R)-pteroside B, (2R,3R)-pteroside C, (2S,3R)-pterosin C, (2R)-pterosin B and (3S)-pteroside D (mixed-type AChE inhibitors), respectively. They were accommodated in the active site surrounded by Tyr72, Asp74, Trp86, Asn87, Tyr124, Trp286, Phe295, Phe297, Tyr337, Phe338, and Tyr341. Consistent with their activity values, (2R)-pteroside B (IC50 = 2.55 µM), (2R,3R)-pteroside C (IC50 = 3.77 µM), (2S,3R)-pterosin C (IC50 = 12.8 µM), (2R)-pterosin B (IC50 = 16.2 µM) and (3S)-pteroside D (IC50 = 27.4 µM) exhibited a B.E. of −7.90, −7.49, −6.03, −5.76, and −4.91 kcal/mol, respectively. (2R)-Pteroside B demonstrated a higher potency than (2S,3R)-pterosin C and (2R)-pterosin B due to the presence of an additional 2-hydroxymethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-3,4,5-triol group, which established three hydrogen bond interactions (Fig. 6b). The OH group of hydroxymethyl and the 3-OH group of the tetrahydro-pyran-triol ring displayed hydrogen bonds with the CO group of Asn87 at distances of 2.23 and 2.28 Å, respectively. Further, the 4-OH group formed a hydrogen bond with the CO group of Trp86 at a distance of 2.13 Å. In the case of (2R,3R)-pteroside C (Fig. 6c), the methyl group at position-2 of the indanone ring did not show a hydrophobic interaction with Tyr341 and thus exhibited comparatively lower activity than (2R)-pteroside B. However, Tyr341 maintained the hydrophobic interaction with the other part of the indanone ring as shown in that of (2R)-pteroside B. The higher activity of (2S,3R)-pterosin C than (2R)-pterosin B was attributed to the existence of an additional OH group at position-3 of the indanone ring, which formed a hydrogen bond with Phe295 at a distance of 1.82 Å (Fig. 6d). The remaining interactions were comparable to (2R)-pterosin B interactions. As shown in Fig. 6e, the OH group of the hydroxyethyl group at position-6 of the indanone ring formed a hydrogen bond with Tyr124 at a distance of 2.48 Å. Tyr124, Trp286, Tyr337, Phe338, and Tyr341 contributed to the hydrophobic interactions. Compared with (2R)-pteroside B and (2R,3R)-pteroside C, (3S)-pteroside D exhibited dissimilar binding interactions due to the presence of the 2,2-dimethyl group at the indanone ring (Fig. 6f). The 2,2-dimethyl group significantly contributed to the distinct docked pose of (3S)-pteroside D. The 5-OH group of the tetrahydro-pyran-triol ring formed a hydrogen bond with Asp74 at a distance of 1.96 Å. The CO group of the indanone ring showed a hydrogen bond with Tyr72 at a distance of 2.97 Å. These interactions accounted for the low activity of (3S)-pteroside D.

The docked pose of (2R,3R)-pterosin C (noncompetitive AChE inhibitor) is displayed in Fig. 6g. (2R,3R)-Pterosin C (IC50 = 23.2 µM) demonstrated a B.E. of −5.01 kcal/mol. The binding pocket of (2R,3R)-pterosin C comprised Tyr72, Trp286, Ser293, Phe297, and Tyr341, with two hydrogen bond interactions. One of the hydrogen bonds was formed between the 3-OH group of the indanone ring and the CO group of Ser293 at a distance of 2.03 Å. The second hydrogen bond was observed between the OH group of the hydroxyethyl group present at position-6 of the indanone ring and Tyr72 at a distance of 1.94 Å. Residues such as Tyr72, Trp286, Phe297, and Tyr341 participated in hydrophobic interactions.

BChE docking

Considering the activity levels and type of BChE inhibition, (2R,3R)-pteroside C and (2S,3R)-pterosin C were selected to demonstrate the docked modes of mixed-type and noncompetitive BChE inhibitors, respectively. Figure 7a, b illustrates the docking models of (2R,3R)-pteroside C and (2S,3R)-pterosin C, respectively. The interactions of the docked compounds inside the BChE active site are presented in Fig. 8.

Fig. 7. Molecular docking models for the mixed-type and the noncompetitive BChE inhibitors.

Molecular docking models for a the mixed-type BChE inhibitor (2R,3R)-pteroside C (blue color) and b the noncompetitive BChE inhibitor (2S,3R)-pterosin C (brown color). Docked poses are superimposed on the X-ray crystal structure of 3F9 (yellow color) (PDB code: 4TPK). BChE, active site residues and compounds are shown by ribbon, line and stick models, respectively. Colors of the dotted lines explain the types of various interactions: hydrogen bonding interactions (green) and hydrophobic interactions (pink). BChE butyrylcholinesterase

Fig. 8. Ligand interaction diagram of BChE inhibitors in the active site.

Ligand interaction diagram of a 3F9, b (2R,3R)-pteroside C, c (3S)-pteroside D, d (2R,3R)-pterosin C, e (2R)-pteroside B, f (2S,3R)-pterosin C and g (2R)-pterosin B in the active site of BChE. Colors of the dotted lines explain the types of various interactions: hydrogen bonding interactions (green), hydrophobic interactions (pink) and π-anion interactions (golden). BChE butyrylcholinesterase

The docked pose of 3F9 showed a B.E. of −8.49 kcal/mol. As displayed in Fig. 8a, hydrophobic interactions were mainly responsible for the ligand binding. Ile69, Gly116, Trp231, Leu286, Ala328, Phe329, and Tyr332 accounted for the hydrophobic interactions, while Asp70 demonstrated a π-anion interaction. Figure 8b−e illustrates the docked poses of (2R,3R)-pteroside C, (3S)-pteroside D, (2R,3R)-pterosin C and (2R)-pteroside B (mixed-type BChE inhibitors), respectively. Their binding pocket was composed of Gly78, Trp82, Gly117, Ser287, Ala328, Phe329, Tyr332, Trp430, Met437, His438, and Tyr440. In accordance with their activity levels, (2R,3R)-pteroside C (IC50 = 5.29 µM), (3S)-pteroside D (IC50 = 19.3 µM), (2R,3R)-pterosin C (IC50 = 20.3 µM) and (2R)-pteroside B (IC50 = 62.0 µM) demonstrated a B.E. of −7.23, −6.59, −6.52, and −4.38 kcal/mol, respectively. As shown in Fig. 8b, the 3-OH group of the indanone ring of (2R,3R)-pteroside C showed two hydrogen bonds with Gly78 and Tyr440 at distances of 2.87 and 2.89 Å, respectively. In the case of (3S)-pteroside D, the 2,2-dimethyl group at the indanone ring affected the binding interactions of the 3-OH group (Fig. 8c). The 3-OH group formed only one hydrogen bond with Trp82 at a distance of 2.94 Å, which resulted in a comparatively lower activity of (3S)-pteroside D than (2R,3R)-pteroside C. As shown in Fig. 8d, (2R,3R)-pterosin C failed to produce a hydrogen bond with Ser287 due to the absence of a 2-hydroxymethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-3,4,5-triol group. Consequently, it yielded a lower activity than (2R,3R)-pteroside C. The lack of the OH group at position-3 of the indanone ring was found to be responsible for the very low activity of (2R)-pteroside B (Fig. 8e), which failed to form hydrogen bonds with Gly78 and Tyr440 similar to (2R,3R)-pteroside C.

The docked poses of (2S,3R)-pterosin C and (2R)-pterosin B (noncompetitive BChE inhibitors) are shown in Fig. 8f, g, respectively. These docked poses were contained in the cavity enclosed by Gly283, Leu286, Val288, Phe357, and Asn397. As per their activity levels, (2S,3R)-pterosin C (IC50 = 44.3 µM) and (2R)-pterosin B (IC50 = 48.1 µM) exhibited a B.E. of −5.40 and −5.06 kcal/mol, respectively. (2S,3 R)-Pterosin C was more potent than (2R)-pterosin B because of the presence of an additional OH group at position-3 of the indanone ring, which formed a hydrogen bond with the CO group of Asn397 at a distance of 2.05 Å (Fig. 8f). Other interactions were found to be similar to (2R)-pterosin B. As shown in Fig. 8g, the OH group in the hydroxyethyl group at position-6 of the indanone ring formed a hydrogen bond with Gly283 at a distance of 2.40 Å. The residues Leu286, Val288, and Phe357 participated in hydrophobic interactions.

Mixed-type inhibitors bind to both the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex, which indicates that these compounds may bind to the catalytic site of each corresponding enzyme. Noncompetitive inhibitors bind to the allosteric site of the free enzyme or enzyme-substrate complex. A recent study suggested that competitive, mixed-type and noncompetitive inhibitors occupy different sites in the binding pockets of BACE1, AChE, and BChE38. During docking for the evaluation of the inhibitory mechanism of pterosin derivatives, the binding sites of the compounds were defined according to their type of inhibition. The docking results indicated that the binding sites of mixed-type and noncompetitive inhibitors for BACE1, AChE, and BChE partially overlap each other at each corresponding active site and were consistent with a previous report38.

BBB permeability

PAMPA-BBB, an in vitro artificial membrane permeability assay for the BBB, is one of the most reliable physicochemical screening tools in the early stage discovery of CNS-targeted drugs40. The PAMPA-BBB system models the transcellular passive diffusion of chemicals across the BBB and measures strictly passive transport mechanisms via an artificial lipid membrane on effective permeability (Pe, cm/s). On the basis of the pattern established for BBB permeation prediction, compounds were classified into (i) “CNS+” (high BBB permeation predicted); Pe (10−6 cm/s) > 4.00, (ii) “CNS−” (low BBB permeation predicted); Pe (10−6 cm/s) < 2.00, and (iii) “CNS+/−” (BBB permeation uncertain); Pe (10−6 cm/s) from 4.00 to 2.00. Accordingly, (2R)-pterosin B, (2S)-pterosin P, and (2S)-pterosin A exhibited high BBB permeation with Pe values of 60.3 × 10−6 cm/s, 7.92 × 10−6 cm/s, and 6.26 × 10−6 cm/s, respectively (Table 4, Supplementary Information 4). The Pe value of (2R)-pterosin B was 1.7-fold higher than that of the CNS drug verapamil (Pe = 34.6 × 10−6 cm/s), which was used for the positive control. (2S,3R)-Pterosin C and (2R,3R)-pterosin C showed uncertain BBB permeation with Pe values of 2.34 and 1.98, respectively. (2R,3R)-Pteroside C, (3S)-pteroside D, and (2R)-pteroside B, which showed the most potent BACE1- and cholinesterase-inhibitory activities among the pterosin derivatives tested, exhibited a very low BBB permeability. The existence of the 2-hydroxymethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-3,4,5-triol group as in pteroside derivatives resulted in a remarkable decrease in the BBB permeability. Compared with (2R)-pterosin B, the additional presence of the OH group at position-3 of the indanone ring as in pterosin C, the hydroxymethyl group at position-2 of the indanone ring as in (2S)-pterosin A or the hydroxymethyl group at position-5 of the indanone ring as in (2S)-pterosin P also significantly reduced the BBB permeability. Considering an exceptionally high BBB permeability and the significant inhibition of BACE1, AChE, and BChE, (2R)-pterosin B may have the potential to exhibit a strong anti-AD activity.

Table 4.

PAMPA-BBB permeability of pterosin derivatives

| Compounds | PAMPA-BBB permeability Pe (10−6 cm/s) |

|---|---|

| (2S)-Pterosin A | 6.26 ± 0.24 |

| (2R)-Pterosin B | 60.3 ± 9.8 |

| (2S,3 R)-Pterosin C | 2.34 ± 0.81 |

| (2R,3 R)-Pterosin C | 1.98 ± 0.17 |

| (2S)-Pterosin P | 7.92 ± 0.36 |

| (2S)-Pteroside A2 | 0.54 ± 0.51 |

| (2R)-Pteroside B | 0.48 ± 0.29 |

| (2S,3R)-Pteroside C | 0.29 ± 0.34 |

| (2R,3R)-Pteroside C | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| (3S)-Pteroside D | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Pteroside Z | 0.61 ± 0.17 |

| Verapamila | 34.6 ± 3.9 |

PAMPA-BBB permeability Pe (10−6 cm/s) is expressed as the mean ± SD of quadruple experiments (Supplementary Information 4)

“CNS+” (high BBB permeation predicted); Pe > 4.0, “CNS+/−” (BBB permeation uncertain); Pe from 4.0 to 2.0, “CNS−” (low BBB permeation predicted); Pe < 2.040

PAMPA parallel artificial membrane permeation assay

aVerapamil was used as positive control

Effects of (2R)-pterosin B and (2R,3R)-pteroside C on the secretion of Aβ peptides by neuronal cells

To investigate the function of (2R)-pterosin B and (2R,3R)-pteroside C in decreasing the excretion of Aβ from neuronal cells, we used a murine neuroblastoma cell line that stably overexpresses human APPswe. The cell line is a cellular model of AD characterized by the excessive secretion of Aβ40 and Aβ42. Toxic amyloid oligomers are formed from the two isoforms of Aβ peptide with different lengths. Aβ40 is the most abundant Aβ isoform in the brain41, while Aβ42 significantly increases with certain forms of AD42. Sandwich ELISA of Aβ40 showed that (2R)-pterosin B significantly reduced the amount of Aβ40 peptide secreted from the neuroblastoma cells into media up to 50% at 500 μM (P < 0.01) (Fig. 9a). Similarly, the secretion of Aβ42 peptide by the neuroblastoma cells significantly decreased in the presence of 500 µM of (2R,3R)-pteroside C (P < 0.05) (Fig. 9b). In conclusion, (2R)-pterosin B and (2R,3R)-pteroside C significantly decreased the secretion of Aβ peptides from neuroblastoma cells at a concentration of 500 μM.

Fig. 9. The effects of (2R)-pterosin B and (2R,3R)-pteroside C on the cellular secretion of Aβ peptides.

a Effect of (2R)-pterosin B on the secretion of Aβ peptides. APPswe-secreting neuroblastoma cells were treated with 12, 60, 250, or 500 µM of (2R)-pterosin B for 24 h, and conditioned media were collected in the presence of protease inhibitor. β-SI (10 µM) was used as positive control. Negative control included cells cultured in the absence of test compounds. Quantitative analysis of secreted Aβ40 and Aβ42 in the conditioned media was performed using sandwich ELISA. The means ± SD from three independent experiments are shown. The secreted Aβ40 peptides significantly decreased in the presence of 500 µM (2R)-pterosin B. CON negative control, β-SI β-secretase inhibitor III, Aβ β-amyloid. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. b Effect of (2R,3R)-pteroside C on the secretion of Aβ peptides. APPswe-secreting neuroblastoma cells were treated with 12, 60, 125, 250, or 500 µM of (2R,3R)-pteroside C for 24 h, and conditioned media were collected in the presence of protease inhibitor. β-SI (10 µM) was used as positive control. Negative control included cells cultured in the absence of test compounds. Quantitative analysis of secreted Aβ40 and Aβ42 in the conditioned media was performed using sandwich ELISA. The means ± SD from three independent experiments are shown. The secreted Aβ42 peptide significantly decreased in the presence of 500 µM (2R,3R)-pteroside C. CON negative control, β-SI β-secretase inhibitor III, Aβ β-amyloid. *P < 0.05

Cytotoxicity of pterosin derivatives based on MTT assay43

Overall, pterosin derivatives displayed negligible cytotoxicity against various normal and cancer cell lines, such as SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma, C6 rat glial cells, NIH3T3 mouse embryo fibroblasts and B16F10 mouse melanoma with LD50 values above 0.5 mM (Supplementary Information 5). In particular, (2R)-pterosin B, (3R)-pterosin D, (2S)-pterosin P, (2S)-pteroside A, (2R)-pteroside B, and (2R,3R)-pteroside C showed no cytotoxicity against the cell lines tested with LD50 values above 5 mM. Intriguingly, several pterosins showed relative antiproliferative effects against SH-SY5Y neuronal cells compared with C6 glial cells of mesenchymal origin. The present results were consistent with a previous report that suggested pterosin derivatives are nontoxic to humans26.

Discussion

The current study is the first investigation to evaluate pterosin derivatives as a series of novel scaffolds to provide MTDLs, which displayed significant inhibitory activities against BACE1, AChE, and BChE simultaneously in a dose-dependent manner. The molecular structures of the enzyme/inhibitor complexes were further predicted to simulate binding between the pterosin derivatives and BACE1, AChE, and BChE. These predictions facilitated the evaluation of binding site-directed inhibition of the enzymes. Furthermore, the docking results explained the SAR of selected mixed-type and noncompetitive BACE1, AChE, and BChE inhibitors. Both the in vitro evaluation and molecular docking data clearly indicated that specific pterosin compounds are potential lead compounds for the development of novel MTDLs for AD therapeutics via the Aβ and cholinesterase pathways.

In particular, (2R)-pterosin B exhibited the highest BBB permeation among commercially available drugs currently used for CNS diseases based on Pe representing effective BBB permeability in vitro40. Therapeutic candidates for CNS diseases, including AD, must be able to permeate the BBB. Only compounds with a molecular weight smaller than 400–700 Da and lipophilicity have been shown to cross the BBB44. Compared with (2R)-pterosin B, the additional 2-hydroxymethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-3,4,5-triol group as in pteroside derivatives, the presence of the 3-OH group as in pterosin C or the hydroxymethyl group at position-2 or 5 of the indanone ring as in (2S)-pterosin A or (2S)-pterosin P remarkably decreased the effective BBB permeability.

The present experiment used quercetin and berberine as positive controls for the BACE1 and cholinesterase assays, respectively. The flavonoid quercetin is a BACE1 inhibitor that exhibits novel pharmacophore features for AD45, as well as an inhibitor for AChE (IC50 = 19.8 µM)46 with a negligible influence on BChE activity47; moreover, it effectively ameliorated AD pathology and tauopathy and protected cognitive and emotional functions in aged (21–24 months old) triple transgenic mouse models of AD (3xTg-AD) treated with 25 mg/kg via i.p. injection every 48 h for 3 months48. Quercetin was reported to exhibit effective BBB permeability, with a log Pe of approximately −7 based on PAMPA-BBB49. Moreover, (2R)-pterosin B displayed BBB permeability with a log Pe of −4.22, which represented an approximately 600-fold higher Pe than that of quercetin. Considering that (2R)-pterosin B displayed a potency to inhibit BACE1 and AChE (IC50 = 29.6 and 16.2 µM, respectively) comparable to quercetin (IC50 = 18.8 µM and 19.8 µM, respectively) and a significant BChE-inhibitory activity (IC50 = 48.1 µM) that quercetin lacks along with an exceptionally high BBB permeability, (2R)-pterosin B was suggested to have a potential to ameliorate AD symptoms. Berberine exhibits a potent anticholinesterase activity50 and the ability to increase the cell viability in the hippocampus and peripheral neurons by enhancing remyelination of neuronal cells51, as well as increases the synthesis of interleukin-Iβ and inducible nitric oxide synthase in a rat model of AD52. Berberine demonstrated procognitive and antiamnestic properties in dementia animal models treated with 5 mg/kg via i.p. injection53 and efficient neuroprotection by reducing the permeability of leukocytes to the injury site in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury54. The log BB of berberine, a pharmacokinetic descriptor of the brain, was reported to be −0.3553, which corresponds to a log Pe of −5.8 according to the correlation between the experimental log BB value and the effective permeability, Pe, determined by PAMPA-BBB, log BB = 0.612 × log Pe + 3.206, R2 = 0.72349. (2R)-Pterosin B exhibited a log Pe of −4.22, which represented an approximately 37-fold higher Pe than that of berberine along with the BACE1-inhibitory activity that berberine lacks55, although the AChE- and BChE-inhibitory activities of (2R)-pterosin B (IC50 against AChE = 16.2 µM, BChE = 48.1 µM, respectively) were lower than those of berberine (IC50 against AChE = 0.39 µM, BChE = 3.32 µM, respectively) approximately 40-fold and 15-fold, respectively.

The main disadvantage of MTDLs as hybrid molecules is their high molecular weight, which conforms to Lipinski’s rule of five56. Thus, the development of merged ligands with a small molar mass similar to a single compound is more difficult and tedious16,22,23. Despite the obstacles, several successful drug scaffolds that contain merged ligands addressing cholinesterases and Aβ oligomerization simultaneously have recently been reported. Bis-tacrines bearing a peptide moiety that specifically prevents surface sites of human AChE from Aβ binding were developed as MTDLs to combat AD57. Accordingly, the hybrid compounds bind the catalytic and peripheral sites of human AChE and act as potent inhibitors of both the catalytic and noncatalytic functions of AChE, interfering with the Aβ self-oligomerization process via its peripheral anionic site58,59. Further, the inhibition of both human BChE and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) as dual cholinesterase-FAAH inhibitors that target both cholinergic and endocannabinoid signaling resulted in improved neuronal transmission by ACh and a simultaneous reduction of neuroinflammation60. (2R)-Pterosin B exhibited significant inhibitory activities against BACE1, AChE, and BChE along with a remarkably high in vitro BBB permeability, which suggests the potential as a scaffold for MTDLs to suppress Aβ production and simultaneously enhance cholinesterase-mediated cognitive functions. Intriguingly, (2R)-pterosin B was demonstrated to activate CREB signaling to protect cartilage against osteoarthritic change28. Moreover, the metabolic pathways involving cyclic nucleotides, including cAMP and cGMP, play an important role in the pathogenesis of AD via CREB activation, which has been regarded as a molecular switch required for learning, memory and neuronal survival7,61–63. The role of (2R)-pterosin B in the activation of CREB signaling and its effects on cognitive functions and neuroprotection in the brain merit evaluation.

Importantly, the present cytotoxicity test based on the MTT assay supported prior observations that pterosin derivatives were nontoxic to humans and not carcinogenic26, although some are cytotoxic to cancer cells, such as HeLa cells64. Further, previous animal experiments demonstrated the biosafety of pterosin derivatives. A mouse model of osteoarthritis was injected with a large amount of pterosin B (15 μL of 900 μM pterosin B) into the intra-articular space of the knee joint three times per week for an extended period of 8–13 weeks, without adverse effects, while ameliorating osteoarthritis28. Further, pterosin A, administered orally in large amounts of 100 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks, displayed no significant adverse effects, while effectively improving glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in various mouse models of diabetes29,30. Additionally, the diabetes animal experiment demonstrated the good oral bioavailability of pterosin A. In our MTT-based cytotoxic test, (2R)-pterosin B exhibited biosafety comparable to (2S)-pterosin A (Supporting Information 5). Intriguingly, diabetes and insulin resistance have emerged as significant risk factors aggravating AD65. In this context, the antidiabetes potential of pterosin-based anti-AD agents is worth investigation.

Considerable genetic and molecular evidence supports that BACE1 is the rate-limiting enzyme in the production of Aβ and the crucial pathogenetic events that lead to AD66. Moreover, several AChE and BChE inhibitors, such as E2020, were approved for the treatment of mild to moderate AD, and the use of these drugs is beneficial in the treatment of AD symptoms19–21. Although the in vitro inhibitory capacities of (2R)-pterosin B against BACE1 (Ki = 38.3 µM), AChE (IC50 = 16.2 µM) and BChE (IC50 = 48.1 µM) are substantially lower than those of a BACE1 inhibitor, AZD3293 (Ki = 0.4 nM) in a clinical study67 or the AChE inhibitor E2020 (IC50 = 6.7 nM) approved for clinical use that share some structural features with (2R)-pterosin B68, we suggest the possibility that pterosin may be administered up to dosages to reach effective concentrations to inhibit BACE1, AChE, and BChE in the brain of AD patients because of its biosafety and significantly high BBB permeability.

In conclusion, the currently available therapies for AD are only symptomatic. The MTDL approach is a very promising strategy for the treatment of AD due to its multifactorial etiology22,23. The structures of several pterosins suggest a potential biological and therapeutic role as a scaffold to provide new MTDLs for AD. Further, our results suggested that the molecular features of enzyme binding and BBB permeability of pterosins facilitate the structural modifications for the design of compounds with improved enzyme-inhibitory activities and BBB permeability for consideration as novel therapeutics for AD.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The present research was supported by the KUMC (Korea University Medical Center) Research and Business Foundation (Project number: Q1611891). We appreciate Prof. Ki-Joong Kim (Korea University, Seoul) for authenticating the P. aquilinum used for the present experiment.

Authors’ contributions

The manuscript was written via the contributions of all authors, and all authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Code availability

Human BACE1, 2WJO; Human AChE, 4EY7; Human BChE, 4TPK; Tetronarce californica AChE, 1ACJ.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Susoma Jannat, Anand Balupuri

Contributor Information

Nam Sook Kang, Phone: +82-10-7292-5756, Email: nskang@cnu.ac.kr.

Gil Hong Park, Phone: +82-10-5472-4854, Email: ghpark@korea.ac.kr.

Supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s12276-019-0205-7.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:131–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older person. Neurology. 2007;69:2197–2204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2015. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf.

- 4.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giacobini E. Cholinergic function and Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2003;18:S1–S5. doi: 10.1002/gps.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buée L, Bussière T, Buée-Scherrer V, Delacourte A, Hof PR. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res. Rev. 2000;33:95–130. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(00)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Y, Li Z, Huang YY, Wu D, Luo HB. Novel phosphodiesterase inhibitors for cognitive improvement in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:5467–5483. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Praticò D. Evidence of oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease brain and antioxidant therapy. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2008;1147:70–78. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Mechanisms of disease: Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vassar R, et al. β-Secretase cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science. 1999;286:735–741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan R, et al. Membrane-anchored aspartyl protease with Alzheimer’s disease β-secretase activity. Nature. 1999;402:533–537. doi: 10.1038/990107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang LB, et al. Elevated β-secretase expression and enzymatic activity detected in sporadic Alzheimer disease. Nat. Med. 2003;9:3–4. doi: 10.1038/nm0103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker KR, Kang EL, Whalen MJ, Shen Y, Tesco G. Depletion of GGA1 and GGA3 mediates post injury elevation of BACE1. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:10423–10437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5491-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai J, et al. β‐Secretase (BACE1) inhibition causes retinal pathology by vascular dysregulation and accumulation of age pigment. EMBO Mol. Med. 2012;4:980–991. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201101084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butini S, et al. The structural evolution of beta-secretase inhibitors: A focus on the development of small-molecule inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2013;13:1787–1807. doi: 10.2174/15680266113139990137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darvesh S, Hopkins DA, Geula C. Neurobiology of butyrylcholinesterase. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;4:131–138. doi: 10.1038/nrn1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greig NH, et al. Selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibition elevates brain acetylcholine, augments learning and lowers Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide in rodent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17213–17218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508575102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tricco AC, et al. Efficacy of cognitive enhancers for Alzheimer’s disease: protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2012;1:31–36. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gauthier S, et al. Strategies for continued successful treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: switching cholinesterase inhibitors. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2003;19:707–714. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greig SL. Memantine ER/Donepezil: a review in Alzheimer’s disease. Cns. Drugs. 2015;29:963–970. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morphy R, Rankovic Z. Designed multiple ligands. An emerging drug discovery paradigm. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:6523–6543. doi: 10.1021/jm058225d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cavalli A, et al. Multi-target-directed ligands to combat neurodegenerative diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:347–372. doi: 10.1021/jm7009364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho, R., Teai, T., Bianchini, J.-P., Lafont, R. & Raharivelomanana, P. Ferns: from traditional uses to pharmaceutical development, chemical identification of active principles. In Working with Ferns: Issues and Applications (eds Fernández, H. et al.) 321–346 (Springer, New York, 2010).

- 25.Zhang HY, et al. Potential therapeutic targets of huperzine A for Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2008;175:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potter DM, Baird MS. Carcinogenic effects of ptaquiloside in bracken fern and related compounds. Br. J. Cancer. 2000;83:914–920. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirono I, et al. Separation of carcinogenic fraction of bracken fern. Cancer Lett. 1984;21:239–246. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(84)90001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yahara Y, et al. Pterosin B prevents chondrocyte hypertrophy and osteoarthritis in mice by inhibiting Sik3. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10959–10969. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu FL, Liu SH, Uang BJ. The therapeutic effect of pterosin A, a small-molecular-weight natural product, on diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:628–638. doi: 10.2337/db12-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu, F.-L., Liu, S.-H. & Uang, B.-J. Use of pterosin compounds for treating diabetes and obesity. US Patent 8, 633, 252B2 (2014)..

- 31.Stauffer SR, Hartwig JF. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) as a high-throughput assay for coupling reactions. Arylation of amines as a case study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6977–6985. doi: 10.1021/ja034161p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres VJ, Featherstone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholls A, et al. Molecular shape and medicinal chemistry: a perspective. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:3862–3886. doi: 10.1021/jm900818s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheung J, et al. Structures of human acetylcholinesterase in complex with pharmacologically important ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:10282–10286. doi: 10.1021/jm300871x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brus B, et al. Discovery, biological evaluation, and crystal structure of a novel nanomolar selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:8167–8179. doi: 10.1021/jm501195e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris GM, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanner MF. Python: a programming language for software integration and development. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 1999;17:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhakta HK, et al. Kinetics and molecular docking studies of loganin, morroniside and 7-O-galloyl-D-sedoheptulose derived from Corni fructus as cholinesterase and β-secretase 1 inhibitors. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2016;39:794–805. doi: 10.1007/s12272-016-0745-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris GM, et al. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19981115)19:14<1639::AID-JCC10>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di L, Kerns EH, Fan K, McConnell OJ, Carter GT. High throughput artificial membrane permeability assay for blood-brain barrier. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2003;38:223–232. doi: 10.1016/S0223-5234(03)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mori H, Takio K, Ogawara M, Selkoe DJ. Mass spectrometry of purified amyloid beta protein in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:17082–17086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naslund J, et al. Relative abundance of Alzheimer A beta amyloid peptide variants in Alzheimer disease and normal aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:8378–8382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crivori P, Cruciani G, Carrupt P, Testa B. Predicting blood−brain barrier permeation from three-dimensional molecular structure. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:2204–2216. doi: 10.1021/jm990968+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimmyo Y, Kihara T, Akaike A, Niidome T, Sugimoto H. Flavonols and flavones as BACE-1 inhibitors: structure–activity relationship in cell-free, cell-based and in silico studies reveal novel pharmacophore features. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1780:819–825. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jung M, Park M. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition by flavonoids from Agrimonia pilosa. Molecules. 2007;12:2130–2139. doi: 10.3390/12092130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Orhan I, Kartal M, Tosun F, S¸ener B. Screening of various phenolic acids and flavonoid derivatives for their anticholinesterase potential. Z. Naturforsch. 2007;62c:829–832. doi: 10.1515/znc-2007-11-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sabogal-Guáqueta AM, et al. The flavonoid quercetin ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease pathology and protects cognitive and emotional function in aged triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease model mice. Neuropharmacology. 2015;93:134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Könczöl Aacute, et al. Applicability of a blood–brain barrier specific artificial membrane permeability assay at the early stage of natural product-based CNS drug discovery. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:655–663. doi: 10.1021/np300882f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kukula-Koch W, Mroczek T. Application of hydrostatic CCC-TLC-HPLC-ESI-TOF-MS for the bioguided fractionation of anticholinesterase alkaloids from Argemone mexicana L. roots. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2005;407:2581–2589. doi: 10.1007/s00216-015-8468-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han AM, Heo H, Kwon YK. Berberine promotes axonal regeneration in injured nerves of the peripheral nervous system. J. Med. Food. 2012;15:413–417. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2011.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu F, Qian C. Berberine chloride can ameliorate the spatial memory impairment and increase the expression of interleukin-1 β and inducible nitric oxide synthase in the rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Bmc Neurosci. 2006;7:78–87. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kukula-Koch W, Kruk-Słomka M, Stępnik K, Szalak R, Biała G. The evaluation of pro-cognitive and antiamnestic properties of berberine and magnoflorine isolated from barberry species by centrifugal partition chromatography (CPC), in relation to QSAR modelling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:2511. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen CC, et al. Berberine protects against neuronal damage via suppression of glia-mediated inflammation in traumatic brain injury. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e115694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jung HA, et al. Anti-Alzheimer and antioxidant activities of Coptidis rhizoma alkaloids. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009;32:1433–1438. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lipinski CA. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004;1:337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]