Abstract

Background: Profiling the microbiome of low-biomass samples is challenging for metagenomics since these samples often contain DNA from other sources, such as the host or the environment. The usual approach is sequencing specific hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene, which fails to assign taxonomy to genus and species level. Here, we aim to assess long-amplicon PCR-based approaches for assigning taxonomy at the genus and species level. We use Nanopore sequencing with two different markers: full-length 16S rRNA (~1,500 bp) and the whole rrn operon (16S rRNA–ITS–23S rRNA; 4,500 bp).

Methods: We sequenced a clinical isolate of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, two mock communities (HM-783D, Bei Resources; D6306, ZymoBIOMICS™) and two pools of low-biomass samples (dog skin from either the chin or dorsal back), using the MinION™ sequencer 1D PCR barcoding kit. Sequences were pre-processed, and data were analyzed using the WIMP workflow on EPI2ME or Minimap2 software with rrn database.

Results: The full-length 16S rRNA and the rrn operon were used to retrieve the microbiota composition at the genus and species level from the bacterial isolate, mock communities and complex skin samples. For the Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolate, when using EPI2ME, the amplicons were assigned to the correct bacterial species in ~98% of the cases with the rrn operon marker, and in ~68% of the cases with the 16S rRNA gene. In both skin microbiota samples, we detected many species with an environmental origin. In chin, we found different Pseudomonas species in high abundance, whereas in dorsal skin there were more taxa with lower abundances.

Conclusions: Both full-length 16S rRNA and the rrn operon retrieved the microbiota composition of simple and complex microbial communities, even from the low-biomass samples such as dog skin. For an increased resolution at the species level, using the rrn operon would be the best choice.

Keywords: microbiome, microbiota, 16S, rrn operon, nanopore, canine, low-biomass, skin, dog

Introduction

The microbiota profile of low-biomass samples such as skin is challenging for metagenomics. These samples are prone to containing DNA contamination from the host or exogenous sources, which can overcome the DNA of interest 1, 2. Thus, the usual approach is amplifying and sequencing certain genetic markers that are ubiquitously found within the studied kingdom rather than performing metagenomics. Ribosomal marker genes are a common choice: 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA genes to taxonomically classify bacteria 3, 4; and ITS1 and ITS2 regions for fungi 5, 6.

Until now, most studies of microbiota rely on second-generation sequencing (massive parallel sequencing), and target a short fragment of the 16S rRNA gene, which presents nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) that are used to infer taxonomy 7, 8. The most common choices for host-associated microbiota are V4 or V1-V2 regions, which present different taxonomic coverage and resolution depending on the taxa 9. V4 region represents better the whole bacterial diversity, although it fails to amplify Cutibacterium acnes (formerly known as Propionibacterium acnes), a ubiquitous skin commensal in humans. So, when performing a skin microbiota study, the preferred choice is V1-V2 regions, although they lack sensitivity for the Bifidobacterium genus and poorly amplify the Verrucomicrobia phylum 10.

Apart from the biases derived from the primer choice, short fragment strategies usually fail to assign taxonomy reliably at the genus and species level. This taxonomic resolution is particularly useful when associating microbiota to clinics such as in characterizing disease status or when developing microbiota-based products, such as pre- or pro-biotics 11. For example, in human atopic dermatitis (AD) the signature for AD-prone skin when compared to healthy skin was enriched for Streptococcus and Gemella, but depleted in Dermacoccus. Moreover, nine different bacterial species were identified to have significant AD-associated microbiome differences 12. In canine atopic dermatitis, Staphylococcus pseudintermedius has been classically associated with the disease. Microbiota studies of canine atopic dermatitis presented an overrepresentation of Staphylococcus genus 13, 14, but the species was confirmed when complementing the studies using directed qPCRs for the species of interest 13 or using a Staphylococcus-specific database and V1-V3 region amplification 14.

With the launching of third-generation single-molecule technology sequencers, these short-length associated issues can be overcome by sequencing the full-length of the 16S rRNA gene (1,500 bp) or even the whole rrn operon (4,500 bp), which includes the 16S rRNA gene, ITS region, and 23S rRNA gene. The Oxford Nanopore Technologies MinION TM sequencer is a single-molecule sequencer that is portable, affordable with a small budget and offers long-read output. Its main limitation is the high error rate.

Several studies assessing the full-length 16S rRNA gene have already been performed using Nanopore sequencing to: i) characterize artificial and already characterized bacterial communities (mock community) 15– 17; ii) characterize complex microbiota samples, from the mouse gut 18, wastewater 19, microalgae 20 and dog skin 21; and iii) characterize the pathogenic agent in a clinical sample 22– 24. On the other hand, only two studies have been performed using the whole rrn operon to characterize mock communities 25 and complex natural communities 26.

Here we aim to assess the potential of Nanopore sequencing using both the full-length 16S rRNA (1,500bp) and the whole rrn operon (4,500bp) in: i) a clinical isolate of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, ii) two bacterial mock communities; and iii) two complex skin microbiota samples.

Methods

Samples and DNA extraction

We used two DNA mock communities as simple, well-defined microbiota samples:

-

-

HM-783D, kindly donated by BEI resources, containing genomic DNA from 20 bacterial strains with staggered ribosomal RNA operon counts (between 1,000 and 1,000,000 copies per organism per μl).

-

-

ZymoBIOMICS™ Microbial Community DNA standard that contained a mixture of genomic DNA extracted from pure cultures of eight bacterial strains.

We also sequenced a pure bacterial isolate of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius obtained from the ear of a dog affected with otitis.

As a complex microbial community, we used two DNA sample pools from the skin microbiota of healthy dogs targeting two different skin sites: i) dorsal back (DNA from two dorsal samples from Beagle dogs); and ii) chin (DNA from five chin samples from Golden Retriever/Labrador crossed dogs). Skin microbiota samples were collected using Sterile Catch-All™ Sample Collection Swabs (Epicentre Biotechnologies) soaked in sterile SCF-1 solution (50 mM Tris buffer (pH 8), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.5% Tween-20). DNA was extracted from the swabs using the PowerSoil™ DNA isolation kit (MO BIO) and blank samples were processed simultaneously (for further details on sample collection and DNA extraction see 27).

PCR amplification of ribosomal markers

There were two ribosomal markers evaluated in this study: full-length 16S rRNA gene (~1,500 bp) and the whole rrn operon (~4,500 bp). Before sequencing, bacterial DNA was amplified using nested PCR, with a first PCR to add the specific primer sets ( Table 1) tagged with the Oxford Nanopore universal tag and a second PCR to add the barcodes from the barcoding kit (EXP-PBC001). Each PCR reaction included a no-template control sample to assess possible reagent contamination.

Table 1. Primer sequences for full-length 16S rRNA gene and rrn operon amplification.

For the first PCR, we targeted the full 16S rRNA gene using 16S-27F and 16S-1492R primer set and the whole rrn operon (16S rRNA gene–ITS–23S rRNA gene) using 16S-27F and 23S-2241R primer set ( Table 1).

PCR mixture for full-length 16S rRNA gene (25 μl total volume) contained 5 ng of DNA template, 5 μl of 5X Phusion® High Fidelity Buffer, 2.5 μl of dNTPs (2 mM), 1 μl of 16S-27F (0.4 μM), 2 μl of 16S-1492R (0.8 μM) and 0.25 μl of Phusion® Hot Start II Taq Polymerase (0.5 U) (Thermo Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania). The PCR thermal profile consisted of an initial denaturation of 30 s at 98°C, followed by 25 cycles of 15 s at 98°C, 15 s at 51°C, 45 s at 72°C, and a final step of 7 min at 72°C.

PCR mixture for the rrn whole operon (50 μl total volume) contained 5 ng of DNA template, 10 μl 5X Phusion® High Fidelity Buffer, 5 μl dNTPs (2 mM), 5 μl each primer (1 μM) and 0.5 μl Phusion® Hot Start II Taq Polymerase (1 U). The PCR thermal profile consisted of an initial denaturation of 30 s at 98°C, followed by 25 cycles of 7 s at 98°C, 30 s at 59°C, 150 s at 72°C, and a final step of 10 min at 72°C.

The amplicons were cleaned-up with the AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) using a 0.5X and 0.45X ratio for the 16S rRNA gene and the whole rrn operon, respectively. Then they were quantified using Qubit™ fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and volume was adjusted to begin the second round of PCR with 0.5 nM of the first PCR product or the whole volume when not reaching the required concentration (mostly for samples that amplified the rrn operon).

PCR mixture for the barcoding PCR (100 μl total volume) contained 0.5 nM of first PCR product, 20 μl 5X Phusion® High Fidelity Buffer, 10 μl dNTPs (2 mM), and 1 μl Phusion® Hot Start II Taq Polymerase (2 U). Each PCR tube contained the DNA, the PCR mixture and 2 μl of the specific barcode. The PCR thermal profile consisted of an initial denaturation of 30 s at 98°C, followed by 15 cycles of 7 s at 98°C, 15 s at 62°C, 45 s (for the 16S rRNA gene) or 150 s (for rrn operon) at 72°C, and a final step of 10 min at 72°C.

Again, the amplicons were cleaned-up with the AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) using a 0.5X and 0.45X ratio for the 16S rRNA gene and the whole rrn operon, respectively. For each sample, quality and quantity were assessed using Nanodrop and Qubit™ fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), respectively.

In most cases, the different barcoded samples were pooled in equimolar ratio to obtain a final pool (1000–1500 ng in 45 μl) to do the sequencing library.

Nanopore sequencing library preparation

The Ligation Sequencing Kit 1D (SQK-LSK108; Oxford Nanopore Technologies) was used to prepare the amplicon library to load into the MinION TM (Oxford Nanopore Technologies), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Input DNA samples were composed of 1–1.5 μg of the barcoded DNA pool in a volume of 45 μl and 5 μl of DNA CS (DNA from lambda phage, used as a positive control in the sequencing). The DNA was processed for end repair and dA-tailing using the NEBNext End Repair/dA-tailing Module (New England Biolabs). A purification step using 1X Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) was performed.

For the adapter ligation step, a total of 0.2 pmol of the end-prepped DNA were added in a mix containing 50 μl of Blunt/TA ligase master mix (New England Biolabs) and 20 μl of adapter mix and then incubated at room temperature for 10 min. We performed a purification step using Adapter Bead Binding buffer (provided in the SQK-LSK108 kit) and 0.5X Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) to finally obtain the DNA library.

We prepared the pre-sequencing mix (14 μl of DNA library) to be loaded by mixing it with Library Loading beads (25.5 μl) and Running Buffer with fuel mix (35.5 μl). We used two SpotON Flow Cells Mk I (R9.4.1) (FLO-MIN106). After the quality control, we primed the flowcell with a mixture of Running Buffer with fuel mix (RBF from SQK-LSK108) and Nuclease-free water (575 μl + 625 μl). Immediately after priming, the nanopore sequencing library was loaded in a dropwise fashion using the SpotON port.

Once the library was loaded, we initiated a standard 48 h sequencing protocol using the MinKNOW™ software v1.15.

Data analysis workflow

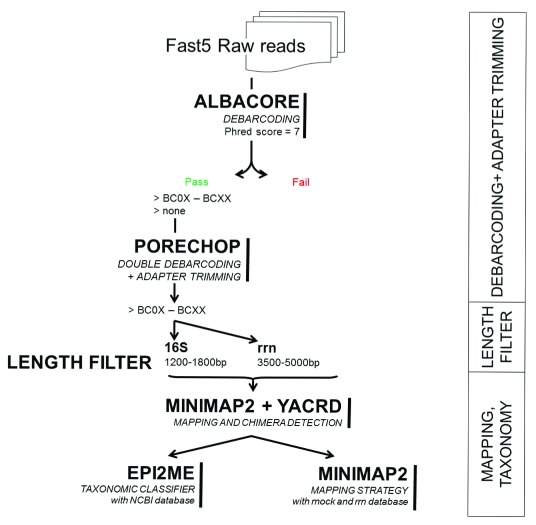

The samples were run using the MinKNOW software. After the run, fast5 files were base-called and de-multiplexed using Albacore v2.3.1. A second de-multiplexing round was performed with Porechop v0.2.3 30, where only the barcodes that agreed with Albacore were kept. Porechop was also used to trim the barcodes and the adapters from the sequences ( Figure 1).

Figure 1. Bioinformatics analysis workflow from raw reads to final data.

Moreover, we removed 45 extra base pairs from each end that correspond to the length of the universal tags and custom primers. After the trimming, reads were selected by size: 1,200 bp to 1,800 bp for 16S rRNA gene; and 3,500 to 5,000 bp for the rrn operon. We mapped the sequences obtained to the rrn database using Minimap2 v2.9 31. Afterwards chimeras were detected and removed using yacrd v0.3 32.

To assign taxonomy to the trimmed and filtered reads we used to strategies: 1) a mapping-based strategy using Minimap2 31; or 2) a taxonomic classifier using What’s in my Pot (WIMP) 33, a workflow from EPI2ME in the Oxford Nanopore Technologies cloud (based on Centrifuge software 34).

For the mapping-based strategy, we performed Minimap2 again with the non-chimeric sequences. We applied extra filtering steps to retain the final results: we kept only those reads that aligned to the reference with a block larger than 1,000 bp (for 16S rRNA gene) and 3,000 bp (for the whole rrn operon). For reads that hit two or more references, only the alignments with the highest Smith-Waterman alignment score were kept. After filtering, the multimapping was mostly present in cases with entries that belonged to the same taxonomy.

The reference databases used in this study were:

-

-

Mock database: a collection of the complete genomes that were included in each mock community, as described by the manufacturer. The HM-783D database was retrieved from NCBI using the reference accession numbers, while Zymobiomics mock community has already its database online on the Amazon AWS server.

-

-

rrn database: sequences from the whole operon retrieved from Genbank 25.

For the taxonomic classification using the WIMP workflow, which uses the NCBI database, only those hits with a classification score >300 were kept 34.

An earlier version of this article can be found on bioRxiv (doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/450734)

Results

Quality filtering results

After Albacore basecalling and Porechop processing, we lost around 5% of the initial reads (3-13%). After length trimming step, we lost more sequences ( Table 2). In general, the samples amplified using 16S rRNA marker gene recovered a higher percentage of reads after the quality control when compared to the rrn operon: 74–95% vs. 32–80%. Particularly for rrn operon, the largest percentage of reads was lost during the length trimming step: some of the reads included in that barcode presented the length of the 16S rRNA gene.

Table 2. Samples included in the study and quality control results.

| Sample | Barcode | Marker | Run | Sample

type |

Albacore

pass |

Porechop

reads |

Length

trimming |

% seq 1st QC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chin_16S_1 | BC04 | 16S rRNA | FC1_1 | Complex | 111230 | 107840 | 97712 | 88% |

| Chin_16S_2 | BC05 | 16S rRNA | FC1_1 | Complex | 104994 | 101932 | 92297 | 88% |

| HM_16S | BC06 | 16S rRNA | FC1_1 | Mock | 121319 | 116946 | 100103 | 83% |

| Chin_rrn_1 | BC07 | rrn | FC1_1 | Complex | 80947 | 76538 | 38285 | 47% |

| Chin_rrn_2 | BC08 | rrn | FC1_1 | Complex | 109863 | 106033 | 55369 | 50% |

| HM_rrn | BC09 | rrn | FC1_1 | Mock | 59335 | 53057 | 18933 | 32% |

| Skin_16S_1 | BC06 | 16S rRNA | FC1_2 | Complex | 35644 | 34102 | 27687 | 78% |

| Skin_rrn_1 | BC09 | rrn | FC1_2 | Complex | 18123 | 15842 | 7545 | 42% |

| Skin_16S_2 | BC11 | 16S rRNA | FC1_2 | Complex | 21522 | 20456 | 17275 | 80% |

| Skin_rrn_2 | BC12 | rrn | FC1_2 | Complex | 17473 | 16448 | 8004 | 46% |

| Z1_16S | BC04 | 16S rRNA | FC2 | Mock | 95635 | 88820 | 70780 | 74% |

| Z2_16S | BC05 | 16S rRNA | FC2 | Mock | 63736 | 61783 | 49113 | 77% |

| Staph_16S | BC06 | 16S rRNA | FC2 | Isolate | 32782 | 32072 | 31147 | 95% |

| Z1_rrn | BC07 | rrn | FC2 | Mock | 65571 | 62415 | 31694 | 48% |

| Z2_rrn | BC08 | rrn | FC2 | Mock | 96000 | 93323 | 49369 | 51% |

| Staph_rrn | BC09 | rrn | FC2 | Isolate | 18839 | 17253 | 15153 | 80% |

Z1 and Z2 are replicates of ZymoBIOMICS™ Microbial Community DNA. HM, HM-783D mock community (BEI resources); Chin, microbiota from a pool of canine chin samples; Skin, microbiota from a pool of dorsal skin samples.

After this first quality control, we performed an alignment with the mock and the rrn databases and checked for chimeras. Chimeras detected were dependent on the database used for the alignment. As a positive control, we used mock samples with their mock database. Chimera ratio was higher for 16S rRNA gene amplicons (around ~40%) than for rrn operon (~10%), suggesting that PCR conditions for the 16S rRNA gene need to be adjusted or the PCR cycles reduced.

To conclude, the final useful sequences when amplifying for either amplicon were ~40%. In 16S rRNA gene, sequences were lost in the chimera checking step. In the rrn operon, sequences were lost in the length trimming step, probably due to the underrepresentation of the amplicon in the flowcell, since we ran them together with full-length 16S rRNA amplicons in the same flow-cell.

Mock community analyses

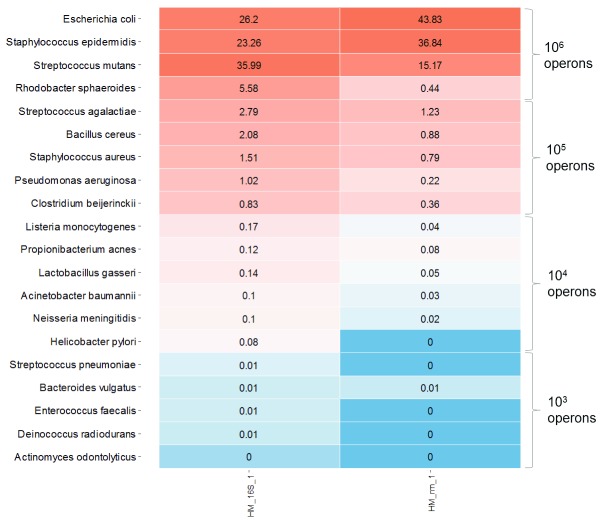

Microbial Mock Community HM-783D contained genomic DNA from 20 bacterial strains with staggered ribosomal RNA operon counts (from 1,000 to 1,000,000 copies per organism per µl). The bacterial composition detected should be proportional to the operon counts. This mock community would allow us determining if our approach reliably represents the actual bacterial composition of the community, especially considering low-abundant species.

We analyzed HM-783D mock community against its own database, which contains only the 20 representative species. On the one hand, using 16S rRNA gene we were able to detect all the bacterial species present in the mock community, even the low-abundant ones. On the other hand, using the rrn operon we were able to detect only the most abundant species (at least 10 4 operon copies) ( Figure 2). This could be due to the lower sequencing depth obtained with rrn when compared with 16S rRNA, and probably due to the underrepresentation of the rrn amplicon in the flowcell when running together with the full-length 16S rRNA amplicons in the same flow-cell, as detailed above. Moreover, the relative abundances of rrn operon sequences were more biased than those obtained from 16S rRNA gene sequencing, when compared to those expected, which confirmed that the primers for rrn need to be improved for universality.

Figure 2. Heat map representing the HM-783D mock community when mapped to its mock database.

The darkest blue represents the bacteria that were not detected (<10 4 copies with rrn operon), whereas the darkest red represents the most abundant bacteria.

Zymobiomics mock community presents the same amount of genomic DNA from 8 different bacterial species; the expected 16S rRNA gene content for each representative is also known, so we are able to determine if our approach represents the actual bacterial composition of the community reliably.

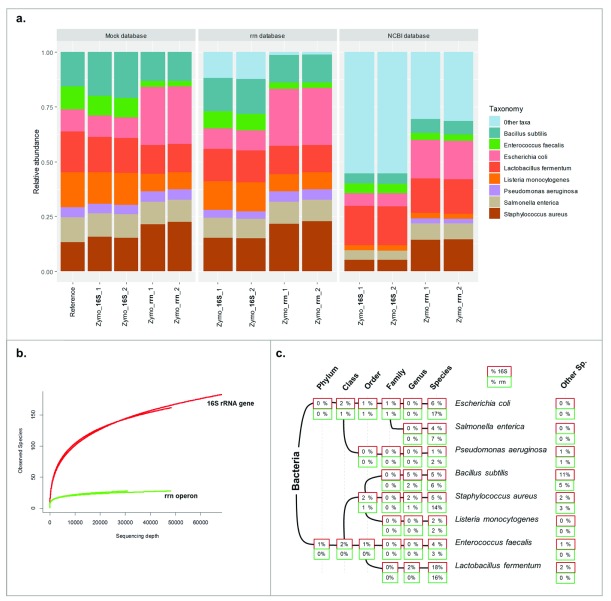

Both 16S rRNA gene and rrn operon sequencing were able to detect 8 out of 8 bacterial species for the Zymobiomics mock community, using Minimap2 and WIMP. The “Other taxa” group in Figure 3A can indicate: i) not expected taxa (wrongly-assigned species, or previous contamination); or ii) higher taxonomic rank taxa (sequences not assigned to species level).

Figure 3. Zymobiomics mock community taxonomic analysis and diversity.

( A) Bar plots representing the relative abundance of the Zymobiomics mock community. “REF” bar represents the theoretical composition of the mock community regarding the 16S rRNA gene content of each bacterium. ( B) Alpha diversity rarefaction plot using the rrn database at the species level. ( C) WIMP output represented in a taxonomic tree and percentage of reads in each taxonomic rank.

Using the mock community database (that contains only the 8 members of that community), we aimed to assess the biases regarding the actual abundance profile. 16S rRNA gene better represented the bacterial composition of the mock community, when considering the abundances. The rrn operon amplification over-represented Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus and under-represented Enterococcus faecalis.

The rrn database 25 contains 22,351 different bacterial species, including representatives of the species in the mock community. When using the rrn database, we found that the rrn operon was a better marker than 16S rRNA: more than 98% of the sequences mapped to the corresponding species, and only <2% of the total sequences mapped to a wrong species with the rrn operon, whereas ~15% of the sequences were given the wrong taxonomy with 16S rRNA. We performed alpha diversity analyses using the same rrn database. The rrn operon hit 26 different species, whereas 16S rRNA over-estimated the actual diversity, with hits to 202 different species ( Figure 3B). However, when considering abundances, the diversity values are more similar, with Shannon indices of 1.95 and 2.51, when using rrn operon and 16S rRNA, respectively (at 30,000 sequences/sample).

Using WIMP, we confirmed again the higher resolution power of rrn operon: ~70% of the sequences were assigned to the correct species compared to ~45% for the 16S rRNA gene. Among all the bacterial species included in the mock community, Bacillus subtilis presented the most trouble for the correct taxonomic classification. The theoretically expected abundance for B. subtilis is 17% using the 16S rRNA gene. When using WIMP, only 5% of the total sequences were correctly classified at the species level, another 5% was classified correctly at the genus level, and another 10% was incorrectly classified as other Bacillus species ( Figure 3C).

Apart from the mock communities, we also sequenced an isolate of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius obtained from canine otitis. When using WIMP approach with rrn operon, 97.5% of the sequences were correctly assigned to the S. pseudintermedius. However, with the 16S rRNA gene, 68% of the sequences were correctly assigned at the species level and 13% at the genus ( Table 3). The wrong assigned species for rrn operon was ~2.5%, compared to ~20% for the 16S rRNA gene. On the other hand, through mapping the sequences to rrn database using Minimap2, we obtained no hit to S. pseudintermedius, since there is no representative in the rrn database. Instead, they were hitting mostly to Staphylococcus schleiferi, which is a closely related species; there were also few hits to Staphylococcus hyicus and Staphylococcus agnetis. These results highlight the need of comprehensive databases that include representatives of all the microorganisms relevant to a microbiome to correctly assign taxonomy.

Complex microbial community analyses

After the first analyses with the mock communities, we were able to detect that the taxonomic resolution was higher when using rrn operon; however, the abundance profile was more reliable using 16S rRNA marker gene. If a bacterial species is not present in the database, the mapping strategy will give us the closest sequence resulting to an inaccurate taxonomic profile, such as we have seen for the Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolate.

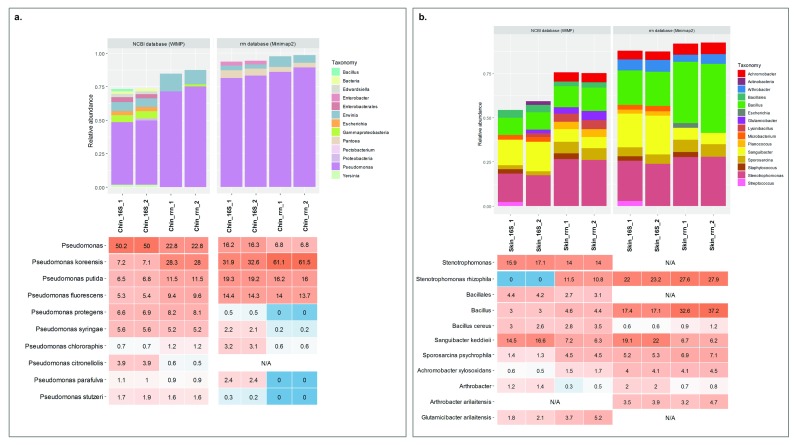

Here, we aimed to taxonomically profile two complex and uncharacterized microbial communities from dog skin (chin and dorsal) using the two different markers and comparing the mapping strategy (Minimap2 and rrn database) with the WIMP workflow (NCBI database).

For chin samples of healthy dogs, we found a high abundance of Pseudomonas species followed by other genus with lower abundances such as Erwinia and Pantoea. Focusing on Pseudomonas, at the species level we were able to detect that the most abundant species was Pseudomonas koreensis, followed by Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas fluorescens ( Figure 4A and Supplementary Table 1). On the other hand, dorsal skin samples were dominated by bacteria from the genera Stenotrophomonas, Sanguibacter, and Bacillus. We reached species level for Stenotrophomonas rhizophila and Sanguibacter keddieii. It should be noted that Glutamicibacter arilaitensis is the same species as Arthrobacter arilaitensis, but is the up-to-date nomenclature 35 ( Figure 4B and Supplementary Table 1). For both skin sample replicates, the results of the most abundant species converged and allowed for characterizing this complex low-biomass microbial community at the species level.

Figure 4. Microbiota composition of complex communities: skin samples of healthy dogs.

( A) Chin samples: upper part of the graphic, bar plot of the composition at the genus level using WIMP (left) and Minimap2 (right); lower part, heat map of the Pseudomonas species within the community (scaled at 100%). ( B) Dorsal skin samples: upper part of the graphic, bar plot of the composition at the genus level using WIMP (left) and Minimap2 (right); lower part, heat map of the ten most abundant taxa within the community. N/A, taxon was not present in the database.

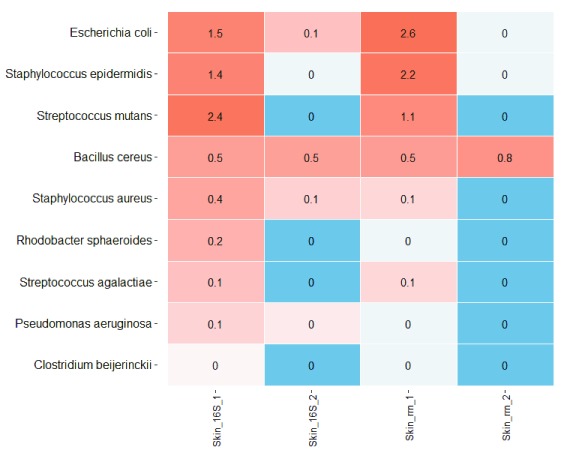

Finally, analyzing the dorsal skin samples, we also detected the presence of contamination from the previous nanopore run. We sequenced dorsal skin samples twice: one with a barcode previously used for sequencing the HM-783D mock community and another one with a new barcode ( Table 2). We were able to detect mock community representatives within the re-used barcode ( Figure 5). Some of them were found only in the sample that was using the re-used barcode (Sample_1); others were also present in the skin sample, such as Bacillus cereus or Staphylococcus aureus. In total, this contamination from the previous run was representing ~6% of the sample composition.

Table 3. Taxonomy assignments of S. pseudintermedius isolate using WIMP workflow with NCBI database and Minimap2 with rrn database.

| WIMP (NCBI database) | Minimap2 ( rrn database) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomy | 16S rRNA | rrn operon | 16S rRNA | rrn operon |

| Staphylococcus pseudintermedius | 65.9% | 74.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Staphylococcus pseudintermedius HKU10-03 | 2.2% | 22.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Staphylococcus | 13.1% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Staphylococcus schleiferi | 2.2% | 0.3% | 94.9% | 82.2% |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 3.2% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Staphylococcus lutrae | 2.7% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Staphylococcus hyicus | 0.3% | 0.1% | 3.3% | 8.2% |

| Staphylococcus agnetis | 0.2% | 0.0% | 1.6% | 9.6% |

| Other Staphylococcus | 3.7% | 1.4% | 0.2% | 0.0% |

| Other species | 6.5% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

Figure 5. Heat map representing the HM-783D mock community contamination.

Samples Skin_1 are the ones re-using the HM-783D barcode from the previous run within the same flowcell. Samples Skin_2 are using a new barcode (not used in a prior run of the same flowcell). Values within the heat map are relative abundances in percentages. The darkest blue represents the bacteria that were not detected and the darkest red the most abundant bacterial contaminants.

Discussion

Full-length 16S rRNA and the rrn operon revealed the microbiota composition of the bacterial isolate, the mock communities and the complex skin samples, even at the genus and species level. Although Nanopore sequencing has a high error rate (average accuracy for the S. pseudintermedius isolate: 89%), we compensated this low accuracy with longer fragments to assess the taxonomy of several bacterial communities. In general, the longer the marker, the higher the taxonomical resolution both when using mapping software, such as Minimap2, or taxonomy classifiers such as WIMP in EPI2ME cloud.

When using EPI2ME (WIMP with NCBI database), the amplicons from the S. pseudintermedius isolate were assigned to the correct bacterial species in ~98% and ~68% of the cases, using rrn operon and 16S rRNA operon, respectively. In a previous study, Moon and collaborators used the full-length 16S rRNA gene for characterizing an isolate of Campylobacter fetus and the marker assigned the species correctly for ~89% of the sequences using EPI2ME 23. The ratio of success on the correct assignment at species level depends on the species itself and its degree of sequence similarity in the selected marker gene. Within the Staphylococcus genus, the 16S rRNA gene presents the highest similarity (around ~97%) when compared to other genetic markers 36. On the other hand, we observed that using the mapping strategy (through Minimap2) could lead to a wrong assigned species if the interrogated bacterium has not any representative on the chosen database. This strategy provides faster results than EPI2ME, but it needs an accurate comprehensive and representative database.

Analyses of the mock communities allowed us to detect whether our approach represented the actual bacterial composition reliably. Moreover, with the HM-783D staggered mock community –with some low abundant species– we were able to detect the sensitivity of both approaches. When using the 16S rRNA marker gene, we were able to detect all bacterial members of both mock communities. However, when using the rrn operon, some of the low-abundant species were not detected. The likely reason is that we obtained a lower number of reads for this marker, up to one magnitude. Mock communities also allowed us to detect the potential biases of our primer sets for both markers, since some of the species detected were over- and under-represented. Actinomyces odontolyticus and Rhodobacter sphaeroides seem to not amplify properly, neither with 16S rRNA gene, nor the rrn operon. Previous studies also detected the same pattern for these specific bacteria even when using or comparing different primer sets 16, 21. Overall, the 16S rRNA primer set seemed less biased than rrn operon. When using the rrn operon, E. coli and S. aureus were overrepresented, whereas others were underrepresented, suggesting that the primers should be improved for universality.

Focusing on the dog chin samples, we could detect that it was mostly Pseudomonas species that colonized: P. koreensis, P. putida, and P. fluorecens were the main representatives. Recently, Meason-Smith and collaborators found Pseudomonas species associated with malodor in bloodhound dogs 37. However, these were not the main bacteria found within the skin site tested, but were in low abundance, differing from what we have found here. On the other hand, Riggio and collaborators detected Pseudomonas as one of the main genera in canine oral microbiota in the normal, gingivitis and periodontitis groups 38. However, the Pseudomonas species were not the same ones that we have detected here. It should be noted that we had characterized these chin samples (and others) with 16S V1-V2 amplicons in a previous study 27, where we found some mutual exclusion patterns for Pseudomonadaceae family. This taxon showed an apparent “invasive pattern”, which could be mainly explained for the recent contact of the dog with an environmental source that contained larger bacterial loads before sampling 27. Thus, our main hypothesis is that the Pseudomonas species detected on dog chin came from the environment, since they have been previously isolated from environments such as soil or water sources 39, 40.

The most abundant species in dog dorsal skin samples were Stenotrophomonas rhizophila, Bacillus cereus, Sanguibacter keddieii, Sporosarcina psychrophila, Achromobacter xylosidans and Glutamicibacter arilaitensis. None of these specific bacterial species had previously been associated with healthy skin microbiota in human or dogs. Some of them have an environmental origin, such as Stenotrophomonas rhizophila, which is mainly associated with plants 41; or Sporosarcina psychrophila, which is widely distributed in terrestrial and aquatic environments 42. The Bacillus cereus main reservoir is also the soil, although it can be a commensal of root plants and guts of insects, and can also be a pathogen for insects and mammals 43. Overall, environmental-associated bacteria have already been associated with dog skin microbiota and are to be expected, since dogs constantly interact with the environment 27.

Regarding Stenotrophomonas in human microbiota studies, Flores et al. found that this genus was enriched in atopic dermatitis patients that were responders to emollient treatment 44. However, previous studies on this skin disease found Stenotrophomonas maltophila associated to the disease rather than Stenotrophomonas rhizophila 45. Achromobacter xylosoxidans has been mainly associated with different kind of infections, as well as skin and soft tissue infections in humans 46. However, both dogs included in this pool were healthy and with representatives of both genus/species, a fact that reinforces the need to study the healthy skin microbiome before associating some species at the taxonomic level to disease. The other abundant bacteria detected on dog skin have been isolated in very different scenarios: Sanguibacter keddieii from cow milk and blood 47, 48; and Glutamicibacter arilaitensis (formerly Arthrobacter arilaitensis) is commonly isolated in cheese surfaces 35, 49.

Finally, some of the technical parameters used should be improved for better performance in future studies. In most cases we did not obtain enough DNA mass to begin with the indicated number of molecules for rrn operon amplicons. Thus, the flowcell contained an underrepresentation of rrn operon amplicons when compared to the full-length 16S rRNA gene. Moreover, in barcodes that contained rrn operon amplicons, a great percentage of reads were lost due to an inaccurate sequence size (~1,500 bp). One possible solution could be running each marker gene in different runs, so multiplexing samples with the same size amplicon to avoid underrepresentation of the larger one. When assessing chimera in mock samples using the specific mock database, we detected that the 16S rRNA gene formed a higher percentage of chimeras than rrn operon. Some options to improve that fact would include lowering PCR cycles performed. Better adjusting the laboratory practices would allow an increased DNA yield that meets the first quality control steps.

To conclude, both full-length 16S rRNA and the rrn operon retrieved the microbiota composition from simple and complex microbial communities, even from the low-biomass samples such as dog skin. Taxonomy assignment down to species level was obtained, although it was not always feasible due to: i) sequencing errors; ii) high similarity of the marker chosen within some genera; and iii) an incomplete database. For an increased resolution at the species level, the rrn operon would be the best choice. Further studies should be aiming to obtain reads with higher accuracy. Some options would include using the 1D 2 kit of Oxford Nanopore Technologies, the new basecallers or the new flow cells with R10 pores. Finally, studies comparing marker-based strategies with metagenomics will determine the most accurate marker for microbiota studies in low-biomass samples.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive, under the Bioproject accession number PRJNA495486: https://identifiers.org/bioproject/PRJNA495486.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by two grants awarded by Generalitat de Catalunya (Industrial Doctorate program, 2013 DI 011 and 2017 DI 037).

[version 1; referees: 2 approved

Supplementary material

Supplementary Table 1. Taxa found on skin microbiota of healthy dogs.List of all the taxa and their relative abundances found on dog skin microbiota samples (chin and dorsal skin). Results for both marker genes tested and for both approaches (Minimap2 + rrn database and WIMP with NCBI database).

References

- 1. Salter SJ, Cox MJ, Turek EM, et al. : Reagent and laboratory contamination can critically impact sequence-based microbiome analyses. BMC Biol. 2014;12(1):87. 10.1186/s12915-014-0087-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kong HH, Andersson B, Clavel T, et al. : Performing Skin Microbiome Research: A Method to the Madness. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(3):561–568. 10.1016/j.jid.2016.10.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ludwig W, Schleifer KH: Bacterial phylogeny based on 16S and 23S rRNA sequence analysis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;15(2–3):155–173. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00132.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yarza P, Ludwig W, Euzéby J, et al. : Update of the All-Species Living Tree Project based on 16S and 23S rRNA sequence analyses. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2010;33(6):291–299. 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iwen PC, Hinrichs SH, Ruppy ME: Utilization of the internal transcribed spacer regions as molecular targets to detect and identify human fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2002;40(1):87–109. 10.1080/714031073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hibbett DS, Ohman A, Glotzer D, et al. : Progress in molecular and morphological taxon discovery in Fungi and options for formal classification of environmental sequences. Fungal Biol Rev. 2011;25(1):38–47. 10.1016/j.fbr.2011.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clarridge JE, 3rd: Impact of 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis for identification of bacteria on clinical microbiology and infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(4):840–862. 10.1128/CMR.17.4.840-862.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Janda JM, Abbott SL: 16S rRNA gene sequencing for bacterial identification in the diagnostic laboratory: pluses, perils, and pitfalls. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(9):2761–2764. 10.1128/JCM.01228-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Walters WA, Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, et al. : PrimerProspector: de novo design and taxonomic analysis of barcoded polymerase chain reaction primers. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(8):1159–1161. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuczynski J, Lauber CL, Walters WA, et al. : Experimental and analytical tools for studying the human microbiome. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(1):47–58. 10.1038/nrg3129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grice EA: The skin microbiome: potential for novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to cutaneous disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014;33(2):98–103. 10.12788/j.sder.0087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chng KR, Tay AS, Li C, et al. : Whole metagenome profiling reveals skin microbiome-dependent susceptibility to atopic dermatitis flare. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1(9):16106. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pierezan F, Olivry T, Paps JS, et al. : The skin microbiome in allergen-induced canine atopic dermatitis. Vet dermatol. 2016;27(5):332–e82. 10.1111/vde.12366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bradley CW, Morris DO, Rankin SC, et al. : Longitudinal Evaluation of the Skin Microbiome and Association with Microenvironment and Treatment in Canine Atopic Dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(6):1182–90. 10.1016/j.jid.2016.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li C, Chng KR, Boey EJ, et al. : INC-Seq: accurate single molecule reads using nanopore sequencing. GigaScience. 2016;5(1):34. 10.1186/s13742-016-0140-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Benítez-Páez A, Portune KJ, Sanz Y: Species-level resolution of 16S rRNA gene amplicons sequenced through the MinION TM portable nanopore sequencer. GigaScience. 2016;5:4. 10.1186/s13742-016-0111-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown BL, Watson M, Minot SS, et al. : MinION TM nanopore sequencing of environmental metagenomes: a synthetic approach. GigaScience. 2017;6(3):1–10. 10.1093/gigascience/gix007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shin J, Lee S, Go MJ, et al. : Analysis of the mouse gut microbiome using full-length 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29681. 10.1038/srep29681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ma X, Stachler E, Bibby K: Evaluation of Oxford Nanopore MinION Sequencing for 16S rRNA Microbiome Characterization. bioRxiv. 2017. 10.1101/099960 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shin H, Lee E, Shin J, et al. : Elucidation of the bacterial communities associated with the harmful microalgae Alexandrium tamarense and Cochlodinium polykrikoides using nanopore sequencing. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5323. 10.1038/s41598-018-23634-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cusco A, Vines J, D’Andreano S, et al. : Using MinION to characterize dog skin microbiota through full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing approach. bioRxiv. 2017. 10.1101/167015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mitsuhashi S, Kryukov K, Nakagawa S, et al. : A portable system for rapid bacterial composition analysis using a nanopore-based sequencer and laptop computer. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5657. 10.1038/s41598-017-05772-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moon J, Kim N, Lee HS, et al. : Campylobacter fetus meningitis confirmed by a 16S rRNA gene analysis using the MinION nanopore sequencer, South Korea, 2016. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2017;6(11):e94. 10.1038/emi.2017.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moon J, Jang Y, Kim N, et al. : Diagnosis of Haemophilus influenzae Pneumonia by Nanopore 16S Amplicon Sequencing of Sputum. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(10):1944–1946. 10.3201/eid2410.180234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Benítez-Páez A, Sanz Y: Multi-locus and long amplicon sequencing approach to study microbial diversity at species level using the MinION ™ portable nanopore sequencer. GigaScience. 2017;6(7):1–12. 10.1093/gigascience/gix043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kerkhof LJ, Dillon KP, Häggblom MM, et al. : Profiling bacterial communities by MinION sequencing of ribosomal operons. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):116. 10.1186/s40168-017-0336-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cuscó A, Belanger JM, Gershony L, et al. : Individual signatures and environmental factors shape skin microbiota in healthy dogs. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):139. 10.1186/s40168-017-0355-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zeng YH, Koblížek M, Li YX, et al. : Long PCR-RFLP of 16S-ITS-23S rRNA genes: a high-resolution molecular tool for bacterial genotyping. J Appl Microbiol. 2013;114(2):433–447. 10.1111/jam.12057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T, et al. : Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(1):e1. 10.1093/nar/gks808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wick R: Porechop. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li H: Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(18):3094–3100. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marijon P: yacrd: Yet Another Chimeric Read Detector for long reads. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 33. Juul S, Izquierdo F, Hurst A, et al. : What's in my pot? Real-time species identification on the MinION. bioRxiv. 2015. 10.1101/030742 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim D, Song L, Breitwieser FP, et al. : Centrifuge: rapid and sensitive classification of metagenomic sequences. Genome Res. 2016;26(12):1721–1729. 10.1101/gr.210641.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Busse HJ: Review of the taxonomy of the genus Arthrobacter, emendation of the genus Arthrobacter sensu lato, proposal to reclassify selected species of the genus Arthrobacter in the novel genera Glutamicibacter gen. nov., Paeniglutamicibacter gen. nov., Pseudoglutamicibacter gen. nov., Paenarthrobacter gen. nov. and Pseudarthrobacter gen. nov., and emended description of Arthrobacter roseus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66(1):9–37. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ghebremedhin B, Layer F, König W, et al. : Genetic classification and distinguishing of Staphylococcus species based on different partial gap, 16S rRNA, hsp60, rpoB, sodA, and tuf gene sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(3):1019–1025. 10.1128/JCM.02058-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meason-Smith C, Older CE, Ocana R, et al. : Novel association of Psychrobacter and Pseudomonas with malodour in bloodhound dogs, and the effects of a topical product composed of essential oils and plant-derived essential fatty acids in a randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled study. Vet Dermatol. 2018. 10.1111/vde.12689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Riggio MP, Lennon A, Taylor DJ, et al. : Molecular identification of bacteria associated with canine periodontal disease. Vet Microbiol. 2011;150(3–4):394–400. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Peix A, Ramírez-Bahena MH, Velázquez E: Historical evolution and current status of the taxonomy of genus Pseudomonas. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9(6):1132–1147. 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mehri I, Turki Y, Chair M, et al. : Genetic and functional heterogeneities among fluorescent Pseudomonas isolated from environmental samples. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2011;57(2):101–14. 10.2323/jgam.57.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wolf A, Fritze A, Hagemann M, et al. : Stenotrophomonas rhizophila sp. nov., a novel plant-associated bacterium with antifungal properties. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52(Pt 6):1937–1944. 10.1099/00207713-52-6-1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yan W, Xiao X, Zhang Y: Complete genome sequence of the Sporosarcina psychrophila DSM 6497, a psychrophilic Bacillus strain that mediates the calcium carbonate precipitation. J Biotechnol. 2016;226:14–15. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ceuppens S, Boon N, Uyttendaele M: Diversity of Bacillus cereus group strains is reflected in their broad range of pathogenicity and diverse ecological lifestyles. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2013;84(3):433–450. 10.1111/1574-6941.12110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Seite S, Flores GE, Henley JB, et al. : Microbiome of affected and unaffected skin of patients with atopic dermatitis before and after emollient treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(11):1365–1372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dekio I, Sakamoto M, Hayashi H, et al. : Characterization of skin microbiota in patients with atopic dermatitis and in normal subjects using 16S rRNA gene-based comprehensive analysis. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56(Pt 12):1675–1683. 10.1099/jmm.0.47268-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tena D, Martínez NM, Losa C, et al. : Skin and soft tissue infection caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: report of 14 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46(2):130–135. 10.3109/00365548.2013.857043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fernández-Garayzábal JF, Dominguez L, Pascual C, et al. : Phenotypic and phylogenetic characterization of some unknown coryneform bacteria isolated from bovine blood and milk: description of Sanguibacter gen.nov. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1995;20(2):69–75. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1995.tb01289.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ivanova N, Sikorski J, Sims D, et al. : Complete genome sequence of Sanguibacter keddieii type strain (ST-74). Stand Genomic Sci. 2009;1(2):110–118. 10.4056/sigs.16197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Irlinger F, Bimet F, Delettre J, et al. : Arthrobacter bergerei sp. nov. and Arthrobacter arilaitensis sp. nov., novel coryneform species isolated from the surfaces of cheeses. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55(Pt 1):457–462. 10.1099/ijs.0.63125-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]