Abstract

Background

Land plant organellar genomes have significant impact on metabolism and adaptation, and as such, accurate assembly and annotation of plant organellar genomes is an important tool in understanding the evolutionary history and interactions between these genomes. Intracellular DNA transfer is ongoing between the nuclear and organellar genomes, and can lead to significant genomic variation between, and within, species that impacts downstream analysis of genomes and transcriptomes.

Results

In order to facilitate further studies of cytonuclear interactions in Eucalyptus, we report an updated annotation of the E. grandis plastid genome, and the second sequenced and annotated mitochondrial genome of the Myrtales, that of E. grandis. The 478,813 bp mitochondrial genome shows the conserved protein coding regions and gene order rearrangements typical of land plants. There have been widespread insertions of organellar DNA into the E. grandis nuclear genome, which span 141 annotated nuclear genes. Further, we identify predicted editing sites to allow for the discrimination of RNA-sequencing reads between nuclear and organellar gene copies, finding that nuclear copies of organellar genes are not expressed in E. grandis.

Conclusions

The implications of organellar DNA transfer to the nucleus are often ignored, despite the insight they can give into the ongoing evolution of plant genomes, and the problems they can cause in many applications of genomics. Future comparisons of the transcription and regulation of organellar genes between Eucalyptus genotypes may provide insight to the cytonuclear interactions that impact economically important traits in this widely grown lignocellulosic crop species.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-019-5444-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Eucalyptus grandis, Organelle genome, Mitochondria, Chloroplast, Plastid

Background

Plastid and mitochondrial genomes are well studied aspects of land plant genomics, with 2484 plastid (1987 “chloroplast”, 506 “plastid”), and 167 mitochondrial genomes on NCBI for land plants as of June 2018, compared to the 141 nuclear genomes completed at the chromosome level [1]. A consequence of the endosymbiotic integration of plastids and mitochondria into plant cells is that the coding potential of their genomes is severely diminished compared to their ancestral genomes [2, 3]. The majority of organellar proteomes are encoded by the nuclear genome of plants, with ±97% of plastid, and ± 99% of mitochondrial targeted proteins encoded by the nucleus [4]. Retained protein-coding organellar genes are essential to the metabolic functions of plastids and mitochondria, and variation in organellar genomes impact fitness and metabolism in angiosperms [5–9].

In plants, intracellular DNA transfer results in nuclear plastidial DNAs (NUPTs) and nuclear mitochondrial DNAs (NUMTs), that are still present in the organellar genomes [4]. Phylogenetic analysis of Arabidopsis and rice organellar DNA insertions show that large, primary insertions of organellar DNA into the nuclear genomes of plants occur, and these insertions decay over time [10]. The rate and distribution of organellar inserts into the nuclear genome vary between plant species, as do the location and proximity to transposable elements, which rearrange and expand inserted regions [10]. These recent inter-genomic DNA transfers between the nuclear and organellar genomes can result in multiple copies of organellar genes in the nuclear genome, presenting interesting avenues of research into the evolutionary history of plants and the process of endosymbiosis, as ongoing gene transfer may lead to the loss of the organellar encoded copy [11].

Key requirements to understanding the impact of organellar genome variation and transcript expression are high-quality annotated genomes, and a catalogue of intracellular genome transfers in order to distinguish between RNA originating from the organellar and nuclear genomes. Since it was sequenced in 2014, the Eucalyptus genome has become an important, and highly utilized genome for a variety of biological, ecological, and biotechnological studies [12]. Here, we update the assembly and annotation of the E. grandis plastid genome (adding 14 genes) and assemble and annotate the mitochondrial genome of E. grandis. We identified recent organellar genome transfers, and potential editing sites that can be used to distinguish transcripts originating from the organellar and nuclear genomes.

Results

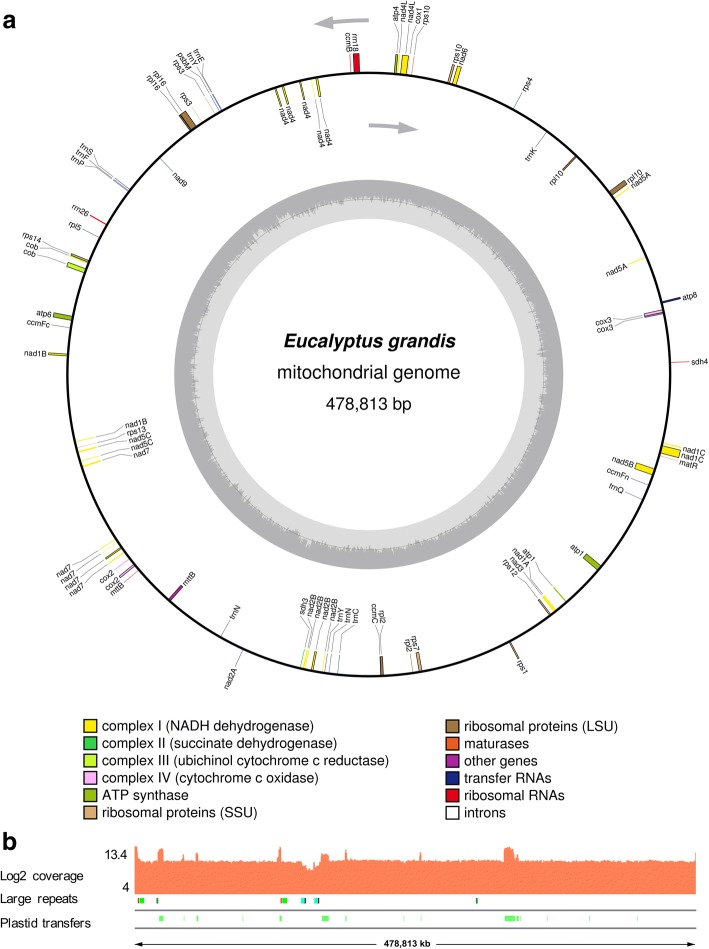

Genome structure and gene content of the E. grandis mitochondrial genome

We used mitochondrial genome scaffolds from the Joint Genome Institute assembly of the E. grandis nuclear genome to perform a reference-based assembly of the mitochondrial genome from Illumina whole genome sequencing (WGS) data. The assembled mitochondrial genome is a single scaffold of 478,813 bp, with average GC content of 44.8% (Fig. 1a and b, Table 1). The average coverage of the WGS reads across the mitochondrial genome is ~ 700, with regions of ten times the average coverage representing overlaps between the plastid and mitochondrial genomes (Fig. 1b) Repeat elements make up 2.47% of the E. grandis mitochondrial genome, consisting mainly of simple and low complexity repeats (Table 1, Additional file 1: Table S1). We identified 19 direct repeat regions larger than 100 bp in the E. grandis mitochondrial genome, the largest of which is 4210 bp long (Fig. 1b, Additional file 2). Additionally, we identified 11 inverted repeat regions longer than 100 bp in the E. grandis mitochondrial genome, the largest of which is 1352 bp (Fig. 1b, Additional file 2). Due to the fact that we could not assemble a circular mitochondrial genome for E. grandis from whole genome sequencing data, we considered that the genome may indeed be present as a linear molecule, or as sub-genomic molecules that arise via recombination of the repeat regions [13]. We did not find evidence of sub-genomic molecules from the depth of coverage across the mitochondrial genome assembly (Fig. 1b). We used SVDetect to determine if any structural variations exist by filtering the alignment file based on the distance and orientation of aligned reads, along with removing any reads whose mate mapped to the nuclear or plastid genomes [14]. The SVDetect defined breakpoints were cross-referenced with the large repeat regions, and the results suggest that most repeat regions are not mediating mitochondrial sub-genomic molecules, as 8 breakpoints are within 250 bp of a repeat region and are found to predominantly be supported by less than 100 read pairs, with three being supported by 309, 219, and 163 read pairs (Additional file 3). Of these, direct repeat 13 shows evidence of repeat mediated structural variation, supported by 219 read pairs (Additional file 4: Figure S1). Any other alternate conformations present in the E. grandis mitochondrial genome could not be identified using this data and could be further assessed using long-read sequencing in the future.

Fig. 1.

Mitochondrial genome of E. grandis. a. Genomic features are shown facing outward (positive strand) and inward (negative strand) of the E. grandis mitochondrial genome represented as a circular molecule. The colour key shows the functional class of the mitochondrial genes, and introns are shown in white. The GC content is represented in the innermost circle. The figure was generated in OGDraw [86]. b. Genome coverage of E. grandis WGS reads in log2 scale (Log coverage) across the mitochondrial genome. WGS reads were mapped with Bowtie 2 [77] and visualized in IGV [78]. The second track (Large repeats) shows mitochondrial repeat regions > 1000 bp in length, with pairs in matching colours, all repeat pairs are direct repeats, with the exception of the repeat pair shown in teal. The third track (Plastid transfers) shows plastid to mitochondrial DNA transfers longer than 100 bp, with e-value > 1 × 10− 5 in green

Table 1.

E. grandis organellar genome characteristics

| Metric | Mitochondria | Plastid |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 478,813 | 160,109 |

| GC content | 44.80% | 36.90% |

| WGS coverage | ~700x | ~3456x |

| WGS insert size | 475 bp | 475 bp |

| WGS read length | 100 bp | 100 bp |

| Total length of homologous regions in the nuclear genome | 1,256,558 bp | 751,886 bp |

| % of inter-organellar DNA transfers | 6% (28,123 bp) | NA |

| Protein coding genes | 39 | 84 (76 unique) |

| tRNA | 20 | 38 (20 unique) |

| rRNA | 4 (3 unique) | 8 (4 unique) |

| Coding genes with introns | 9 | 11 |

| tRNA with introns | 0 | 8 |

| # of predicted editing sites (PREP/PREPACT) | 470/505 | 49/53 |

| Editing sites/gene (PREP/PREPACT) | 12/13 | 0.6/0.7 |

| % of genome repeat elements | 2.47% | 3.05% |

A total of 39 protein coding genes were annotated in the genome, in addition to 20 annotated tRNA and 4 rRNA genes (Fig. 1a, Table 2). The vast majority of the E. grandis mitochondrial genome is non-coding, with ~ 13% comprising of protein coding regions, and ~ 6% of introns. The mitochondrial protein coding genes are all single copy genes, with no duplications present (Table 2). The E. grandis mitochondrial genome does not contain any sequences similar to the ribosomal protein subunit genes rps11, rps8, and rpl6, which have been lost in angiosperms [15, 16]. Short fragments of rps2 (141 nt) and rps19 (42 and 69 nt) were found, but no full-length copies of these genes were present. The gene content was similar to other sequenced land plant mitochondrial genomes [17], with no genes exclusively lost in E. grandis. Ten E. grandis mitochondrial genes contain introns, with three of these, nad1, nad2, and nad5, being trans-spliced (Fig. 1a, Table 2). There are 16 single copy tRNA genes in the E. grandis mitochondrial genome, with two copies each of tRNA-Asn, tRNA-Met, tRNA-Tyr and tRNA-fMet (Fig. 1a, Table 1, Table 2). The mitochondrial genome of E. grandis contains four rRNA genes, with two copies of 5S rRNA present (Fig. 1a, Tables 1, 2).

Table 2.

E. grandis mitochondrial genome gene content

| Complex I | nad1 (5*) | nad2 (5*) | nad3 | nad4 (4) | nad4L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nad5 (4*) | nad6 | nad7 (5) | nad9 | ||

| Complex III | cob | ||||

| Complex IV | cox1 | cox2 (2) | cox3 | ||

| Complex V | atp1 | atp4 | atp6 | atp8 | atp9 |

| Cytochrome C biogenesis | ccmB | ccmC | ccmFC (2) | ccmFN | |

| Ribosomal large subunit | rpl2 (2) | rpl5 | rpl10 | rpl16a | |

| Ribosomal small subunit | rps3 (2) | rps4 | rps7 | rps10 (2) | rps11 |

| rps12 | rps13 | rps14 | |||

| Intron maturase | matR | ||||

| Protein translocase | mttB | ||||

| Other | psbMpl | ||||

| rRNA genes | 26S rRNA | 18S rRNA | 5S rRNA (×2) | ||

| tRNA genes | tRNA-Asn (×2)pl | tRNA-Asppl | tRNA-Cys | tRNA-fMet (×2) | tRNA-Gln |

| tRNA-Glupl | tRNA-Gly | tRNA-Hispl | tRNA-Ile | tRNA-Lys | |

| tRNA-Met (×2)pl | tRNA-Phe | tRNA-Pro | tRNA-Ser | tRNA-Trppl | |

| tRNA-Tyr (×2)pl |

Genes with multiple exons are denoted with the number of exons shown in parenthesis, and trans-spliced genes are indicated with *. tRNAs underlying plastid transferred regions are indicated with pl. a Note that rpl16 is annotated as a pseudogene due to an internal stop codon, but this gene has an in-frame GUG present downstream from the ATG start codon, which may be used as a start codon as in other plant species

Recently, the first mitochondrial genome of the order Myrtales was released, that of Lagerstroemia indica (NC_035616.1). Compared to the E. grandis mitochondrial genome, the 333,948 bp long mitochondrial genome of L. indica is smaller, with a higher GC content at 46% compared to 44% in E. grandis. Of the annotated L. indica mitochondrial genes, one has been lost in E. grandis (rps19), while two are not present in L. indica (sdh3 and rps13). As is typical of land plant mitochondrial genomes [18], there has been massive re-arrangement of gene order between the two Myrtales families, with the largest block of collinear genes being sdh4-cox3-atp8 (Additional file 5: Figure S2). Further, rpl16 has gained an intron in L. indica, which is not present in E. grandis. Given the diverse nature of the Myrtales [19], and the frequent rearrangements and gene losses present in mitochondrial genomes [20] (Additional file 6: Figure S3), the differences between the two families are expected, and can be used in further phylogenetic analyses.

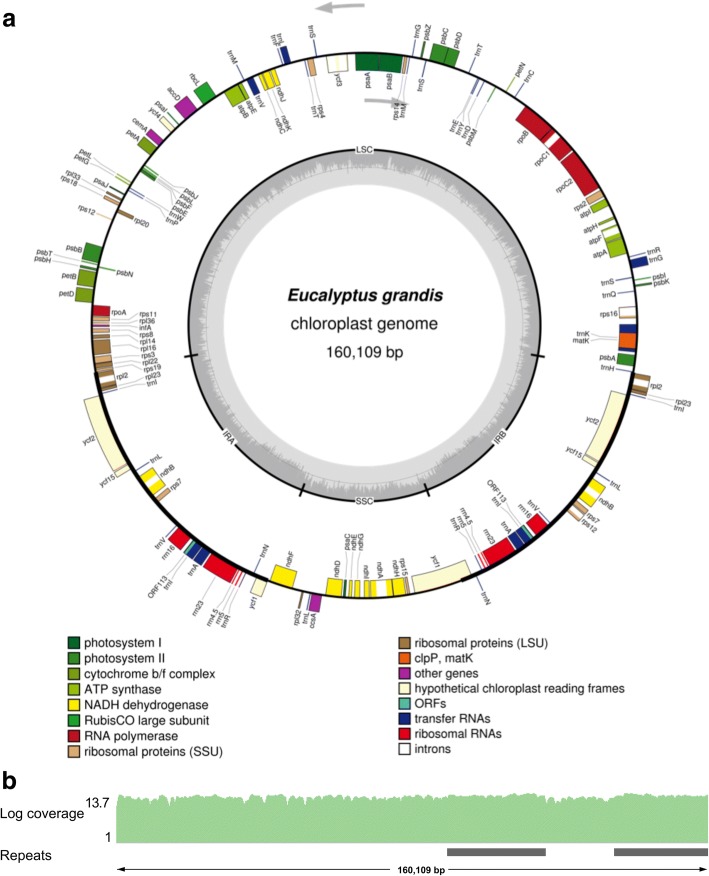

Genome structure and gene content of the E. grandis plastid genome

Although the plastid genome of E. grandis has been previously reported [21], some discrepancies in gene content exist when compared to other published Eucalyptus plastid genomes [22]. Eucalyptus plastid genomes typically contain 85 protein coding genes [22], and the available E. grandis plastid genome (NC_014570.1) contains 74 annotated protein coding genes [21, 23]. In the assembly reported here, the plastid genome of E. grandis was assembled using whole genome sequencing data (as above for the mitochondrial genome) and was subsequently annotated (Fig. 2a). The assembled plastid genome of E. grandis is 160,109 bp long, having the quadripartite structure of most land plant plastid genomes, with two large inverted repeat (IR) regions that are flanked by two single copy (SC) regions (small- SSC and large- LSC) (Fig. 2a). Coverage of the WGS reads aligned to the assembled plastid genome shows high coverage of 3500x across the length of the genome (Fig. 2b, Table 1). The high coverage of reads mapped give confidence in the downstream annotation and analysis of the assembled plastid genome.

Fig. 2.

Plastid genome of E. grandis. a. Genomic features are shown facing outward (positive strand) and inward (negative strand) of the circular E. grandis plastid genome. The colour key shows the functional class of the plastid genes, and introns are shown in white. The GC content is represented in the innermost circle with the inverted repeat (IR) and single copy (SC) regions indicated. The figure was generated in OGDraw [77]. b. Genome coverage of E. grandis WGS reads in log2 scale (Log coverage) across the plastid genome. WGS reads were mapped with Bowtie 2 [78] and visualized in IGV [79]. The position of the plastid inverted repeat regions are shown below (Repeats) in grey

The E. grandis plastid genome consists of 3.05% short repeat elements, the most abundant being simple and low complexity repeats (Table 1, Additional file 1: Table S1) The genome contains 90 genes, which includes six pseudogenes, for a total of 84 protein coding genes (Fig. 2a, Table 1). There are 37 annotated tRNA genes, representing 20 unique tRNAs. Introns are present in 8 of the annotated tRNA genes, namely tRNA-Lys, tRNA-Gly, tRNA-Leu, tRNA-Val, tRNA-Ile (2 copies), and tRNA-Ala (2 copies). The 8 rRNA genes in the plastid genome are found in the repeat regions, for a total of 4 unique rRNA genes. The intron structure of the plastid protein coding genes is highly conserved, with 11 genes containing at least two introns, of these, ndhB and rpl12 are present as duplicates in the IR region. Three of the intron containing genes contain three exons; ycf3, clpP, and rps12. Two exons of rps12 are present in the IR regions, and are trans-spliced to exon 1 found in the LSC region, as is common in land plants [24, 25]. The only difference in the coding regions of the previously published Eucalyptus plastid genomes (excluding the 2011 E. grandis plastid genome) is the annotation of psbL, which is annotated as a pseudogene, but has a predicted C to U editing site that creates a start codon (Additional file 7 - Sheet 2). The creation of a canonical start codon via C to U editing in the psbL gene has been well documented in other land plants [26, 27]. Thus, we include psbL as a bona fide gene in E. grandis plastid genome annotation.

Post-transcriptional editing in the organellar genomes of E. grandis

Land plant plastid and mitochondrial encoded transcripts are known to undergo extensive post-transcriptional C to U editing, which generally results in non-synonymous amino acid changes, and can create and abolish start and stop codons [28]. In order to identify potential transcript editing sites in the E. grandis plastid and mitochondrial genomes, we predicted editing events using two homology based predictive approaches, PREPACT and PREP-suite [29, 30]. In the E. grandis mitochondrial genome, we identified 505 and 470 predicted C to U editing sites for an average of ~ 13 and ~ 12 editing sites per gene with PREPACT and PREP-mt respectively (Table 1, Additional file 8: Figure S4a, Additional file 7 - Sheet 1). Three of the predicted edits create canonical AUG translational start sites in mitochondrial nad1A, nad4L, and rps10, which have been reported in other plant species [31–33]. Interestingly, mitochondrial rpl16 is annotated as a pseudogene due to an internal stop codon (TAG). In other plant species, this codon position is encoded as CAG and is post-transcriptionally edited to a stop codon (TAG), leading to a downstream non-canonical start codon (GTG) being used instead [32, 34]. This GTG is conserved in the mitochondrial genome of E. grandis, and it may be possible that rpl16 is not a pseudogene and is translated from the GTG codon.

Plastid protein coding gene transcripts are also post-transcriptionally edited by C to U, although the frequency of editing sites in plastid genomes are drastically lower in land plant plastids compared to mitochondria [35]. In the plastid genome of E. grandis, we report 49 predicted C to U editing sites as predicted by PREPACT, using Arabidopsis thaliana as reference protein databases, and 53 using PREP-cp (Table 1, Additional file 8: Figure S4b, Additional file 7 - Sheet 2) [29]. These editing sites exclude sites duplicated in the inverted repeat regions, keeping only the sites found in IRA, as it includes the full length of ycf1. These results are standard for the highly conserved plastid genomes of land plants [36, 37].

We found evidence of editing sites in the organellar genomes of E. grandis with 24 bulked polyA-selected, paired end transcriptome datasets from eight E. grandis tissues (Additional file 8: Figure S4a and b). Using REDItools to discriminate between potential variants at the DNA level and true RNA editing sites, we could confirm 377 of the predicted mitochondrial editing sites, and 32 of the predicted plastid editing sites (Additional file 8: Figure S4 c and d, Additional file 7) [38]. These include the predicted start codons of psbL, nad4L, and rps10. REDItools identified 52 mitochondrial and 6 plastid edits not predicted by either PREPACT or PREP-suite, (Additional file 8: Figure S4c and d), which may be bona fide editing sites, or may be due the relatively low cut-offs defined in the analysis (total coverage > 10 reads, at least 3 reads supporting the edit). Further, REDItools identified synonymous editing sites in codon position 1 of plastid and mitochondrial genes, 1 of which is found in the plastid genome, and 6 in the mitochondrial genome (Additional file 7). Due to the fact that the transcriptome data was prepared from polyA selected RNA, the editing sites identified should be confirmed using total RNA sequencing, as polyadenylated transcripts in organelles are destined for degradation, and do not accurately reflect organellar transcriptomes [39, 40].

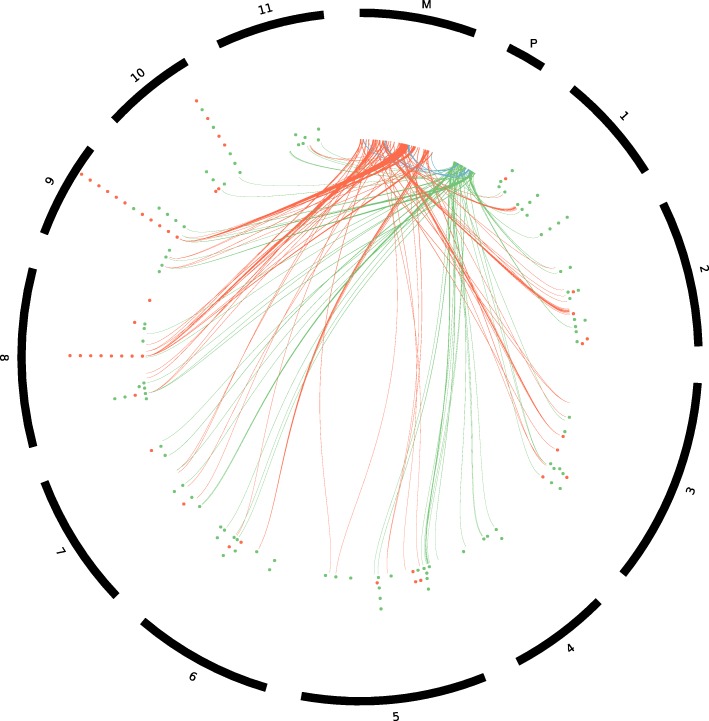

DNA transfer between organellar and nuclear genomes

In order to identify transferred DNA between the nuclear and organellar genomes of E. grandis, we used BLAST analysis to identify sequences of significant homology between the three genomes. After filtering the BLAST analysis results for sequences longer than 100 bp with e-values < 1 × 10− 3 and identity > 75%, we found a total of 751,886 bp of plastid origin and 1,256,558 bp of mitochondrial origin the nuclear genome (Fig. 3, Additional file 9: Table S2). The nuclear regions of organellar homology are distributed across all chromosomes of the nuclear genome (Fig. 3, Additional file 9: Table S2), with the largest proportion found on chromosome 5 for plastid DNA (88,691 bp), and chromosome 8 for mitochondrial DNA (193,727 bp). The mitochondrial genome of E. grandis consists of 6% (28,123 bp) chloroplast-like DNA sequences over 18 regions, with transfers ranging from 7281 bp to 152 bp in length. A single plastid gene, psbM, has been transferred and annotated in the E. grandis mitochondrial genome. We find that eight tRNA genes in the mitochondrial genome overlap with plastid transferred regions (indicated by pl in Table 2). BLAST analyses of the inter-organellar DNA transfers against all NCBI land plant organellar genomes show that inter-organellar DNA transfers are from the plastid to the mitochondria, and that no mitochondrial to plastid DNA transfer has taken place in E. grandis (Additional file 10: Table S3, Additional file 11).

Fig. 3.

DNA and gene transfer between nuclear and organellar genomes in E. grandis. The outer track shows the relevant chromosomes of E. grandis, the inner track shows complete coding regions of NUMTs and NUPTs in red and green respectively. The red (mitochondria) and green (plastid) dots indicate full length gene transfers from the organelles to the nuclear genome. The ribbons represent DNA transfers identified by BLAST analysis greater than 500 nt, with percentage identity greater than 75%. Red ribbons indicate mitochondrial to nuclear DNA transfer, green ribbons indicate plastid to nuclear DNA transfer, and blue ribbons represent plastid to mitochondrial DNA transfer. For clarity, the scale of the plastid and mitochondrial genome size has been increased by 100x

Transferred DNA between the nuclear and organellar genomes of land plants creates the potential for complete transcript transfer that could be expressed from the nuclear genome [4]. In order to identify full length organellar transcripts in the nuclear genome of E. grandis, we used BLAST to align predicted organellar genes to E. grandis nuclear genes (> 80% of nuclear or organellar transcript length), and the annotation of the E. grandis v2.0 genome (Fig. 3, Additional file 12). We find 101 nuclear genes that have been transferred from the plastid genome (32 annotated as A. thaliana chloroplast genes, and 69 from the BLAST analysis). Further, there are 40 nuclear genes of mitochondrial origin (1 annotated as A. thaliana mitochondrial gene and 39 from the BLAST analysis). When genes without annotations in this group are examined for potential homologs in other plant species using the PLAZA database [41], we find that most of these nuclear genes are in fact orphan genes, with no homologs in the nuclear or organellar genomes of other dicot plant species. There are two exceptions, Eucgr.J01097 and Eucgr.J02736, which are members of conserved gene families in plants. The first of these, Eucgr.J01097, is a homolog of a mitovirus RNA dependant polymerase [42], which occurs in the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes of 12 other dicot plant species (PLAZA family HOM03D004415) [34]. Eucgr.J02736 forms part of a gene family that is present in six dicot plant species (PLAZA family HOM03006657) [41]. This gene is likely of plastid origin, as it is also found in the plastid transferred gene set (Additional file 12). Mismatches and indels present in the nuclear copies of full length organellar genes will allow for the identification of mRNA-seq reads mapped to the genome that they are expressed from (Additional file 12).

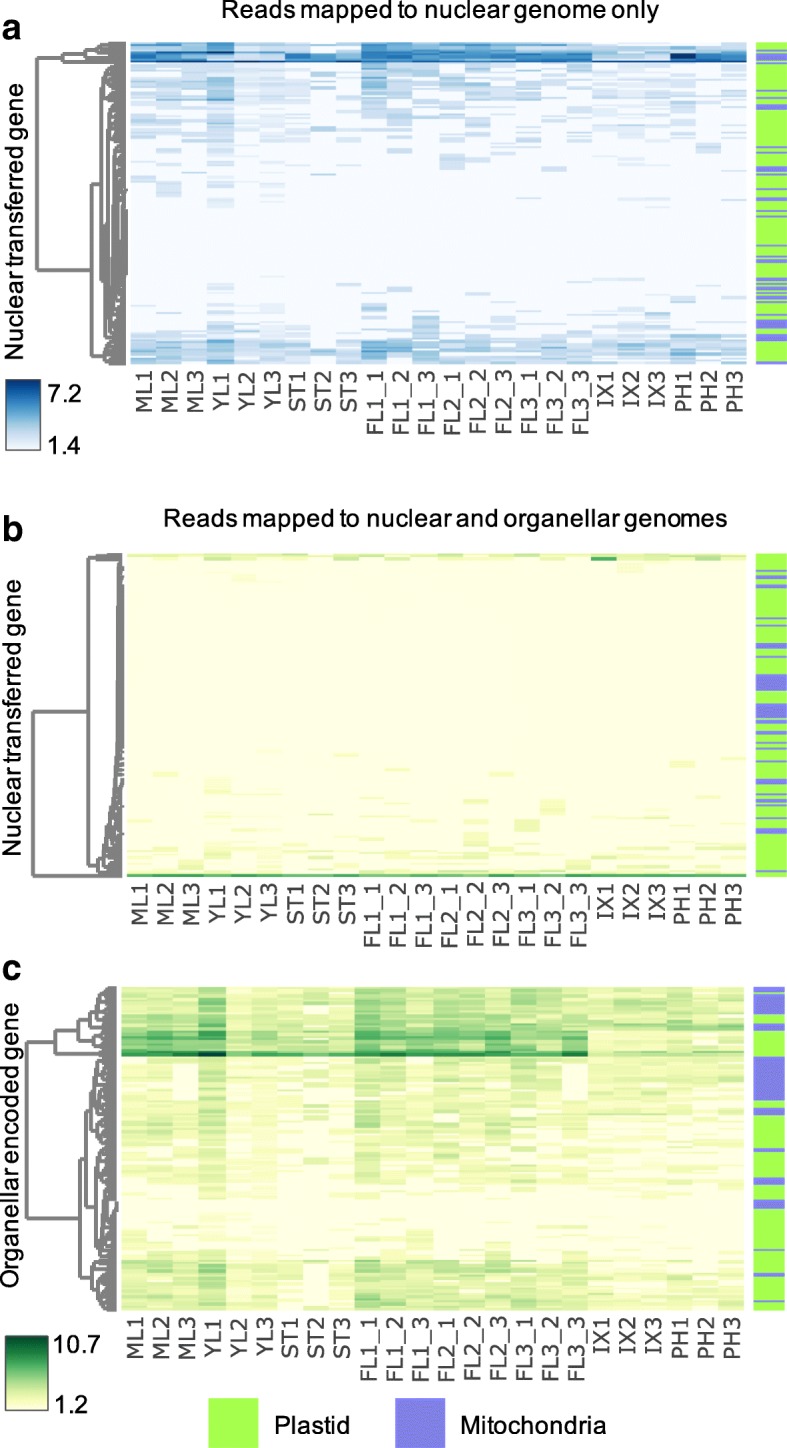

Transcription of NUMT and NUPT genes in E. grandis

In order to assess whether the E. grandis NUMTs and NUPTs identified above are functionally expressed, we aligned polyA-selected reads (from [43, 44]) to the nuclear genome, and compared read counts with the same reads aligned to the nuclear and organellar genomes (Fig. 4). To ensure that the reads aligned accurately to the organellar genomes, GSNAP was used with predicted organellar transcript editing sites defined as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [45]. Evidence from eight tissues specific datasets revealed that organellar transferred genes in the nuclear genome are not functionally expressed (Fig. 4). The reads aligning to the nuclear genome (Fig. 4a) were drastically reduced when mapped to all three genomes simultaneously (Fig. 4b), and instead, mapped preferentially to the organellar genomes (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Poly-A selected RNA read abundance of nuclear genes with homology or annotation suggesting organellar transfer (a. and b.), and organellar encoded genes (c.) aligned to the nuclear genome only (blue) and the nuclear and organellar genomes of E. grandis (green). a. Variance stabilizing transformation (VST) counts of 141 organellar transferred genes in the nuclear genome of polyA selected RNA sequencing data aligned to the nuclear genome of E. grandis only. b. VST counts of full-length transferred genes in the nuclear genome of polyA selected RNA sequencing data aligned to the nuclear and organellar genomes of E. grandis simultaneously. c. VST counts of organellar encoded genes of polyA selected RNA sequencing data aligned to the nuclear and organellar genomes of E. grandis simultaneously. Row dendrograms on the left-hand side of all three heat maps show clustering of genes based on expression variation between tissues. Tissue samples are shown at the bottom edge of each heatmap, three biological replicates per tissue. Tissues are abbreviated as follows: Mature leaf (ML), young leaf (YL), shoot tips (ST), flowers stage 1 (FL_1), flowers stage 2 (FL_2), flowers stage 3 (FL_3), immature xylem (IX), and phloem (PH). The range of VST count values per heatmap are represented from low (white) to high (blue) for the polyA selected RNA mapping to the nuclear genome only, and from low (yellow) to high (green) for the polyA selected RNA mapping to the nuclear and organellar genomes. The bar on the right of the heatmaps shows the organellar origin of each gene, either plastid (transferred or encoded- green) or mitochondrial (transferred or encoded- blue)

Of all the identified genes that are potentially transferred from the organellar genome to the nuclear genome, only one does not have decreased read counts when the polyA mRNA data is aligned to all three E. grandis genomes. This gene, Eucgr.E01203, was identified as a transferred gene due to its annotation as an A. thaliana chloroplast NADH-Ubiquinone/plastoquinone (complex I) protein gene (ndhB2). The parameters used in the BLAST analysis above did not identify this gene as an organellar transferred gene, as the CDS of this gene is truncated compared to the organellar ndhB2 gene (Eucgr.P00068), with a length of 228 versus 1533 nt. Read coverage across this gene in mature leaf tissue shows that the aligned reads do not span the annotated CDS, rather, they are found in the 5’ UTR (Additional file 13: Figure S5). The variance stabilizing transformation (VST) counts of Eucgr.E01203 are thus unlikely to represent functional gene expression.

Organellar encoded genes show that the polyA-selected mRNA reads aligned differentially across tissues in E. grandis. In general, the plastid and mitochondrial genes have low numbers of reads aligning across all tissues, with some genes having high numbers of reads aligning in leaf and flower tissues (Fig. 4c). Compared to the all nuclear encoded genes, we identified 28 organellar genes with significant polyA-selected read abundance variation between immature xylem and mature leaf tissues (Additional file 14: Table S4). All 28 of these organellar encoded genes have decreased polyadenylated transcripts in immature xylem as compared to mature leaf. Of these, only one is a mitochondrial encoded gene, Eucgr.M00039 (maturase R). The plastid differentially polyadenylated genes are predominantly photosystem genes (psaA, B, and J, and psbA, B, C, D, E, H, I, J, K, L, and T). The tissue specific nature of the read abundance variation in the photosystem genes specifically shows that these reads are not an artefact of transcripts “escaping” polyA selection based their GC content [46]. Further, we conclude that plastid encoded photosystem genes are differentially polyadenylated between tissues in E. grandis, and that organellar encoded genes are either not significantly polyadenylated or are lowly expressed in xylem.

Discussion

Organellar genomes are an important resource for many genomic and biotechnological applications [47], and as such, we aimed to provide a resource of high-quality sequences and annotations for the mitochondrial and plastid genomes of Eucalyptus grandis. The genus Eucalyptus consists of more than 700 species and their hybrids, many of which are economically and ecologically important [48, 49]. Additionally, E. grandis is an emerging model species for the study of xylogenesis [50]. The mitochondrial genome of E. grandis the second for the order Myrtales and should facilitate further studies in the phylogeny of this order [51, 52]. The size of the E. grandis mitochondrial genome, GC content, number of coding genes, and predicted RNA editing sites is well within the range of sequenced land plant mitochondrial genomes [53]. The mitochondrial genome of E. grandis shares many features with other published land plant mitochondrial genomes, specifically the loss of rps and rpl subunits [54]. The genome structure of the mitochondrial genome is potentially linear, or present as sub-genomic circles due to the presence of large repeat regions [20, 55]. We could identify one repeat mediated structural variant from the aligned paired-end reads, although any of the repeat regions could be involved in alternate conformations of the mitochondrial genome. As we could not confidently detect any other possible structural variants, mitochondrial DNA isolation from meristematic tissues or ovules [13, 55], and long-read sequencing methods may improve the assembly in future [56].

Organellar DNA is surprisingly mobile, and DNA transfers between organellar and nuclear genomes, and between species occur frequently [4], predominantly from the plastid and mitochondria to the nucleus [10], and from the nucleus and plastid to the mitochondria [9]. In many commercially important biomass crop species, large amounts of organellar DNA has been transferred to the nuclear genome. In Populus trichocarpa and Gossypium raimondii, near complete chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes respectively have been transferred to the nuclear genome [15, 57]. In E. grandis, we identified DNA transfers from the organelles to the nucleus, and from the plastid to the mitochondria (Fig. 3, Additional file 1: Table S1). Nuclear genes that align to the organellar genomes are gene fragments that have been annotated as complete genes due to the evidence of gene expression resulting from polyadenylated organellar transcripts. Using next-generation RNA-sequencing, we were able to show that the NUMT and NUPT genes, and nuclear genes which align to the organellar genomes are not functionally expressed from the nuclear genome of E. grandis (Fig. 4). Utilizing a method of SNP aware alignment, using predicted editing sites as SNPs, we show that reads in transferred regions preferentially align to the organellar genomes (Fig. 4). Further analysis showed that feature counts, especially when they are extremely low, do not accurately reflect transcript expression, but rather fragmented alignment of a few reads across the transcript (Additional file 13: Figure S5). This analysis allows for the confident alignment of mRNA reads to the three genomes of E. grandis for the quantification of organellar transcripts in future experiments.

The analysis of polyA-selected mRNA sequencing read alignment to the organellar genomes has value beyond identifying expressed NUMT and NUPT genes, as organellar genes are polyadenylated as a degradation signal [40, 58, 59]. We find that between mature leaf and immature xylem, the vast majority of differentially polyadenylated genes are photosystem genes from the chloroplast genome (Additional file 14: Table S4). Photosystem genes are either not expressed, or very lowly expressed in non-photosynthetic tissues such as xylem [60, 61]. Given RNA turnover requirements, and imprecise transcriptional termination, the highly expressed photosystem genes in chloroplasts may lead to the polyadenylation of those transcripts in mature leaf [40]. Additionally, mature leaf chloroplast transcriptomes are differentially regulated compared to those in young leaf [62], and transcript degradation may play a role in this process.

Conclusion

This work provides a platform for further investigation into the myrtaceae by providing a reference genome and annotations for the mitochondria of E. grandis. The organellar genomes can be used in the future to study the transcription of organellar genes, and the tissue specific mechanism of transcriptional regulation by polyadenylation [5, 7]. Further, the co-evolution of nuclear and organellar genomes have been shown to affect hybrid vigour and speciation [63–66], and this work will allow for such studies in Eucalyptus, genera in which hybrids are ecologically and industrially important.

Methods

Assembly and annotation of the E. grandis organellar genomes

Paired end, whole genome sequencing reads of a three-year-old E. grandis genotype TAG0014 from mature leaf tissue was used in the assembly of the E. grandis mitochondrial and plastid genomes (SRP132546). The reads were sequenced by the Beijing Genomics Institute using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. Contigs of mitochondrial origin, identified from the nuclear genome assembly project [12], were used as seed sequences for assembly using MITObim v1.6 using the -- quick flag, and kmer length of 41 [67]. The mitochondrial genome was assessed for circularity using the circules.py script available as a part of MITObim (https://github.com/chrishah/MITObim). SVDetect was used to determine if the WGS reads aligned to the mitochondrial genome assembly using Bowtie 2 showed evidence of alternative genome configurations [14, 68]. As they are mediated by large repeat regions, alternate configurations of the genome can be identified from discordant read pairs that mapped in the wrong orientation, or at a distance larger or smaller than half the insert size (< 250 bp, > 750 bp), which were identified using SAMtools v1.3.1 view flag ‘-F 1294’ [14, 69]. To avoid regions which may be artifacts of plastid and nuclear DNA transfer, we further removed all reads which were not uniquely mapped to the mitochondrial genome. The identified SVDetect breakpoints within 250 bp of a mitochondrial repeat region were identified using bedtools v2.27.1 closest [70].

The mitochondrial genome was manually annotated using a combination of homology-based predictions, namely Mitofy [71], MFannot [72], and Geneious v10.0.5 [73]. Similarly, the plastid genome was assembled using NOVOPlasty v1.1 with kmer length of 39 [74], with the previous E. grandis plastid genome as seed sequence (NC_014570.1). The plastid genome was manually annotated using DOGMA [75], CpGAVAS [76], Geneious v10.0.5 [73], and MFannot [72].

Transcript editing sites were identified using the PREPACT web server and PREP-suite (Mt and Cp) for both genomes [29, 30]. For PREPACT analysis of the mitochondrial genome, Arabidopsis thaliana, Nicotiana tabacum, and Vitis vinifera was used to identify conserved C to U edits using BLASTx prediction, with stop codons edited if possible and all other parameters kept at default. A predicted editing site was classified as being predicted by PREPACT if it occurred in at least two of the species used for prediction. For the PREPACT plastid genome editing site prediction, Arabidopsis thaliana was used as reference protein database for BLASTx prediction, with all other parameters kept at default. For PREP-suite analysis of the plastid and mitochondrial genomes, a prediction confidence cut-off of 0.5 was used to predict editing sites, with all other parameters at default. Low-complexity repeats were identified in both genomes using RepeatMasker [77], with reference set to Arabidopsis thaliana, and all other parameters as default. Large genomic repeats were identified with Unipro UGENE [78], with repeat identity set to > 95%, and repeat length > 100 nt. Both genomes were visualized with OrganellarGenomeDRAW [79], and WGS reads were aligned using Bowtie 2 [68] to visualize coverage using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV [80]).

Identification and analysis of NUMTs and NUPTs in the E. grandis nuclear genome

BLAST (BLAST 2.3.0+) hits of > 100 bp, e-value > 1 × 10− 5, and 75% identity were used in the analysis of NUPTs and NUMTs, and inter-organellar genome transfer [81]. Regions originating from the IR regions of the plastid genome were counted once, unless they spanned the SC flanking regions. Inter-organellar DNA transfers were assigned an organelle of origin using a custom BLAST database of all land plant organelles retrieved from GenBank in June 2017 [51]. Results of the DNA transfer analysis outlined above were visualized using Circos v0.69 [82] with transferred regions > 500 bp shown for clarity. In order to identify transferred protein coding genes between the nuclear and organellar genomes, BLAST analysis of full-length transcripts from the organellar genomes to the complete nuclear genome and vice versa was done. Transcripts are considered complete transfers if they covered > 80% of the transcript length in either the nuclear or organellar gene and had > 75% identity between transcripts. Nuclear genes that are annotated as organellar genes were identified based on their closest A. thaliana homolog from the E. grandis v2 nuclear genome annotation [12].

PolyA-selected mRNA sequencing alignment, quantification, and editing analysis

PolyA-selected, paired end mRNA sequencing data from eight E. grandis tissues (as described in [43, 44]) were aligned to all three E. grandis genomes using GSNAP with allowed mismatch set to 1 (gmap v2016-09-23 [45]). Predicted editing sites of the organellar transcripts identified in the annotation step were used as SNP files for GSNAP alignment in order not to bias the alignment towards the nuclear genome. The resulting sam alignment files were converted to bam format using SAMtools view and sorted by position with SAMtools sort (SAMtools v1.3.1 [69]). The sorted bam files were then used to generate raw feature counts using HTSeq-count v0.6.1 [82] with concatenated nuclear and organellar gtf annotation files. DESeq2 v1.8.2 [83], implemented in RStudio v1.0.136 [84], was used to generated variance stabilized transformed (VST) counts and identify differentially expressed genes between immature xylem, phloem, and mature leaf tissue samples. The results were visualized using ggplot2 v2.2.1 [85] in RStudio v1.0.136.

REDItools version 1.0.4 [38] was used to identify editing sites using the aligned polyA selected reads across 8 E. grandis tissues. We used the REDItoolDnaRna.py script to ensure that organellar genomic variants were not called as editing sites due to transferred DNA regions, using the Bowtie 2 [68] genomic DNA alignments to differentiate between DNA variants and RNA editing [38]. The settings used were as follows: predict C to U and G to A edits (for sense and antisense genes, respectively), editing sites must have > 10 reads aligned, with > 3 reads supporting the editing event, minimum per base quality > 25. We then filtered the identified editing sites based on the following parameters: No DNA variants in the site, sense orientation with organellar gene coding regions (C to U for sense genes, and G to A for antisense genes). All tissue samples were bulked, and edits were identified if they were found in any dataset and were in codon position 1 or 2 of in the sense strand of plastid and mitochondrial genes.

Additional files

Table S1. E. grandis mitochondrial and plastid genome short repeat elements overview (DOCX 13 kb)

Excel spreadsheet of the results of UniPro UGENE analysis of large (length > 100 bp, identity > 95%) repeats in the Eucalyptus grandis mitochondrial genome. (XLSX 10 kb)

Excel spreadsheet of the results of SVDetect analysis results showing breakpoints of structural variants in the E. grandis mitochondrial genome (Sheet 1), and breakpoints within 250 bp of mitochondrial genome large repeat regions (Sheet 2). (XLSX 14 kb)

Figure S1. Discordantly mapped read pairs flanking direct repeat 13 of the mitochondrial genome. The insert size of the reads is ~ 118,000 bp, compared to the expected 475. These reads suggest a repeat mediated structural variation, supported by SVDetect analysis. Read pair insert is shown by the red lines and the direct repeat is shown in the blue track. (PDF 51 kb)

Figure S2. Mitochondrial genome gene order comparison between Eucalyptus grandis and Lagerstroemia indica. The gene order for the E. grandis mitochondrial genome is shown at the right of the figure, and that of L. indica on the top. Genes that are not found in each genome are indicated with red text. Collinear genes are indicated by red boxes. (PDF 29 kb)

Figure S3. Multiple whole genome alignment of selected land plant mitochondrial genomes. Alignment was performed using the progressiveMauve algorithm in Mauve multiple alignment tool [87], with the coloured blocks representing Locally Collinear Blocks of sequences between genomes. The red lines indicate the length of the mitochondrial genomes, and the name of the organism is shown at the bottom of each genome. This figure shows the widespread genome rearrangements present in plant mitochondrial genomes. (PDF 286 kb)

Excel spreadsheet of the results of predicted editing sites in the E. grandis mitochondrial (Sheet 1) and plastid (Sheet 2) genomes using PREPACT, PREP-suite, and REDItools, labelled by position of the edit in the coding sequence. (XLSX 38 kb)

Figure S4. Number of predicted C to U editing sites in the mitochondrial and plastid genomes of E. grandis using PREPACT, PREP-suite, and REDITOOLS mRNA editing detection of polyA-selected reads. a. Number of editing sites (y-axis) in E. grandis mitochondrial genes (x-axis) as predicted by PREP-Mt (blue), PREPACT (orange), and evidence from bulked polyA-selected reads from three samples each of eight tissues in E. grandis using REDItools (DNA-RNA algorithm: minimum read depth = 10, minimum amount of reads per editing event = 3) shown in grey. b. Number of editing sites (y-axis) in E. grandis plastid genes (x-axis) as predicted by PREP-Cp (blue), PREPACT (orange), and evidence from polyA-selected reads using REDItools (grey). These figures show that bulked polyA selected reads are sufficient to detect the majority of predicted editing events in land plants, however the read depth lower than would be detected with total RNA sequencing. c. Number of predicted editing sites in common between PREP-Mt, PREPACT, and REDItools in the E. grandis mitochondrial genome. d. Number of predicted editing sites in common between PREP-Cp, PREPACT, and REDItools in the E. grandis plastid genome. (PDF 52 kb)

Table S2. Amount of E. grandis organellar DNA transfer to nuclear chromosomes (DOCX 13 kb)

Table S3. Inter-organellar DNA transfers in E. grandis show regions of high homology between E. grandis plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Additional BLAST analysis with land plant organellar genomes show that the transferred regions are all transferred from the plastid to the mitochondria (see Additional file 11). (DOCX 14 kb)

Excel spreadsheet of the origin of inter-organellar DNA transfers, showing the organellar genomes of sequenced land plants, and the results of BLAST analysis of E. grandis mitochondrial genome (TAG0014_chr_M) regions that have significant homology to the E. grandis plastid genome. Note that all mitochondrial genomes analysed have no significant matches to the transferred regions, suggesting that there is no transfer of DNA from the mitochondrial genome to the plastid genome. (XLSX 667 kb)

Excel spreadsheet of nuclear genes of organellar origin for mRNA-sequencing read mapping by homology using BLAST analysis (> 80% full length of gene matches with > 90% identity to organellar genome) or by annotation (annotation closest match is Arabidopsis thaliana organellar gene). (XLSX 13 kb)

Figure S5. Sashimi plot of polyA-selected mRNA reads mapped to Eucgr.E01203 in E. grandis mature leaf tissue. The plot shows the count of reads (0 to 105) aligned to the annotated gene regions of Eucgr.E01203. Reads were aligned using GSNAP and visualized in the Integrated Genome Viewer. Black lines show the annotated gene regions, and thicker black bars show the annotated protein coding regions. The plot shows that the read coverage of Eucgr.E01203 across the protein coding regions is lower than in the 5’ UTR, indicating that the VST counts generated for this gene do not represent functional gene expression. (PNG 14 kb)

Table S4. Differently expressed organellar encoded genes in E. grandis where negative log2 fold change values indicate increased polyA selected RNA read abundance in mature leaf compared to immature xylem. (DOCX 14 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Karen van der Merwe for generating the Circos diagram used in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Science and Technology (Strategic Grant for the Eucalyptus Genomics Platform) and National Research Foundation of South Africa (Bioinformatics and Functional Genomics Programme, Grants 86936 and 97911 to A.A.M.), Sappi South Africa, the Technology and Human Resources for Industry Programme (Grant 80118) through the Forest Molecular Genetics Programme at the University of Pretoria (to A.A.M.), and D.P. is supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa Scarce Skills grant.

Availability of data and materials

FastQ files of the whole genome sequencing of E. grandis TAG0014 mature leaf tissue are available at the Sequence Read Archive under the project accession PRJNA433608 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/study/?acc=PRJNA433608). Mitochondrial and plastid genome sequences and annotations have been submitted to the NCBI Genbank database and can be found under accession number NC_040010.1 for the mitochondria (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/browse/?report=5#!/organelles/NC_040010), and MG925369.1 for the plastid (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MG925369).

Abbreviations

- bp

Base pairs

- IR

Inverted repeat

- NUMT

Nuclear mitochondrial DNA

- NUPT

Nuclear plastidial DNA

- polyA

Polyadenylated

- SC

Single copy

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- UTR

Untranslated region

- VST

Variance stabilizing transformation

- WGS

Whole genome sequencing

Authors’ contributions

EM is the lead investigator and conceived of the study. DP performed the data analysis and wrote the article with EM. AAM is the lead investigator for the genome sequence and transcriptome analysis and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and commented on the article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Desre Pinard, Email: desre.pinard@fabi.up.ac.za.

Alexander A. Myburg, Email: zander.myburg@fabi.up.ac.za

Eshchar Mizrachi, Email: eshchar.mizrachi@fabi.up.ac.za.

References

- 1.Benson DA, Cavanaugh M, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Ostell J, Pruitt KD, et al. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D41–D47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiller JW. Plastid endosymbiosis, genome evolution and the origin of green plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gualberto JM, Mileshina D, Wallet C, Niazi AK, Weber-lot F, Dietrich A. The plant mitochondrial genome : dynamics and maintenance. BMC Genomics. 2014;100:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleine T, Maier UG, Leister D. DNA transfer from organelles to the nucleus: the idiosyncratic genetics of endosymbiosis. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:115–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joseph B, Corwin JA, Züst T, Li B, Iravani M, Schaepman-Strub G, et al. Hierarchical nuclear and cytoplasmic genetic architectures for plant growth and defence within Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:1929–1945. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.112615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bock D, Andrew RL, Rieseberg LH. On the adaptive value of cytoplasmic genomes in plants. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:4899–4911. doi: 10.1111/mec.12920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budar F, Roux F. The role of organelle genomes in plant adaptation. Plant Signal Behav. 2016;2324 February. doi:10.4161/psb.6.5.14524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Wright AF, Murphy MP, Turnbull DM. Do organellar genomes function as long-term redox damage sensors? Trends Genet. 2009;25:253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubo T, Newton KJ. Angiosperm mitochondrial genomes and mutations. Mitochondrion. 2008;8:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michalovova M, Vyskot B, Kejnovsky E. Analysis of plastid and mitochondrial DNA insertions in the nucleus (NUPTs and NUMTs) of six plant species: size, relative age and chromosomal localization. Heredity. 2013;111:314–320. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2013.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rockenbach K, Havird JC, Monroe JG, Triant DA, Taylor DR, Sloan DB. Positive selection in rapidly evolving plastid-nuclear enzyme complexes. Genetics. 2016;204:1507–1522. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.188268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myburg AA, Grattapaglia D, Tuskan GA, Hellsten U, Hayes RD, Grimwood J, et al. The genome of Eucalyptus grandis. Nature. 2014;510:356–362. doi: 10.1038/nature13308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sloan DB. One ring to rule them all? Genome sequencing provides new insights into the “master circle” model of plant mitochondrial DNA structure. New Phytol. 2013;200:978–985. doi: 10.1111/nph.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeitouni B, Boeva V, Janoueix-Lerosey I, Loeillet S, Legoix-Né P, Nicolas A, et al. SVDetect: a tool to identify genomic structural variations from paired-end and mate-pair sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1895–1896. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bi C, Paterson AH, Wang X, Xu Y, Wu D, Qu Y, et al. Analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the diploid cotton Gossypium raimondii by comparative genomics approaches. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:5040598. doi: 10.1155/2016/5040598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye N, Wang X, Li J, Bi C, Xu Y, Wu D, et al. Assembly and comparative analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequence of an economic plant Salix suchowensis. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3148. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sloan DB, Alverson AJ, Chuckalovcak JP, Wu M, McCauley DE, Palmer JD, et al. Rapid evolution of enormous, multichromosomal genomes in flowering plant mitochondria with exceptionally high mutation rates. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park S, Ruhlman TA, Sabir JSM, Mutwakil MHZ, Baeshen MN, Sabir MJ, et al. Complete sequences of organelle genomes from the medicinal plant Rhazya stricta (Apocynaceae) and contrasting patterns of mitochondrial genome evolution across asterids. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:405. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger BA, Kriebel R, Spalink D, Sytsma KJ. Divergence times, historical biogeography, and shifts in speciation rates of Myrtales. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2016;95:116–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gualberto JM, Newton KJ. Plant mitochondrial genomes: dynamics and mechanisms of mutation. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2017;68:225–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-112232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paiva JAP, Prat E, Vautrin S, Santos MD, San-Clemente H, Brommonschenkel S, et al. Advancing Eucalyptus genomics: identification and sequencing of lignin biosynthesis genes from deep-coverage BAC libraries. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:137–150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bayly MJ, Rigault P, Spokevicius A, Ladiges PY, Ades PK, Anderson C, et al. Molecular Phylogenetics and evolution chloroplast genome analysis of australian eucalypts – Eucalyptus, Corymbia, Angophora, Allosyncarpia and Stockwellia (Myrtaceae) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;69:704–716. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steane DA. Complete nucleotide sequence of the chloroplast genome from the Tasmanian blue gum, Eucalyptus globulus (Myrtaceae) DNA Res. 2005;12:215–220. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hildebrand M, Hallick RB. Trans-splicing in chloroplasts: the rps12 loci of Nicotiana tabacum. PNAS. 1988;85:372–376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmitz-Linneweber C, Williams-Carrier RE, Williams-Voelker PM, Kroeger TS, Vichas A, Barkan A. A pentatricopeptide repeat protein facilitates the trans-splicing of the maize chloroplast rps12 pre-mRNA. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2650–2663. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bock R, Hagemann R, Kossel H, Kudla J. Tissue- and stage-specific modulation of RNA editing of the psbF and psbL transcript from spinach plastids- a new regulatory mechanism? Mol Gen Genomics. 1993;240:238–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00277062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kudla J, Gabor L, Metzlaff M, Hagemann R, Kossel H. RNA editing in tobacco chloroplasts leads to the formation of a translatable psbL mRNA by a C to U substitution within the initiation codon. Embo. 1992;1:1099–1103. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichinose M, Sugita M. RNA editing and its molecular mechanism in plant organelles. Genes . 2016;8:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Lenz H, Knoop V. PREPACT 2.0: Predicting C-to-U and U-to-C RNA editing in organelle genome sequences with multiple references and curated RNA editing annotation. Bioinform Biol Insights. 2013;7:1–19. doi: 10.4137/BBI.S11059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mower JP. The PREP suite: Predictive RNA editors for plant mitochondrial genes, chloroplast genes and user-defined alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37 Web Server issue:W253–W259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park S, Grewe F, Zhu A, Ruhlman TA, Sabir J, Mower JP, et al. Dynamic evolution of Geranium mitochondrial genomes through multiple horizontal and intracellular gene transfers. New Phytol. 2015. 10.1111/nph.13467. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Picardi E, Horner DS, Chiara M, Schiavon R, Valle G, Pesole G. Large-scale detection and analysis of RNA editing in grape mtDNA by RNA deep-sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4755–4767. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackman SD, Warren RL, Gibb EA, Vandervalk BP, Mohamadi H, Chu J, et al. Organellar genomes of white spruce (Picea glauca): assembly and annotation. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;8:29–41. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bock H, Brennicke A, Schuster W. Rps3 and rpl16 genes do not overlap in Oenothera mitochondria: GTG as a potential translation initiation codon in plant mitochondria? Plant Mol Biol. 1994;24:811–818. doi: 10.1007/BF00029863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takenaka M, Zehrmann A, Verbitskiy D, Härtel B, Brennicke A. RNA editing in plants and its evolution. Annu Rev Genet. 2013;47:335–352. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freyer R, Kiefer-Meyer M-C, Kossel H. Occurrence of plastid RNA editing in all major lineages of land plants. PNAS. 1997;94:6285–6290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tseng C-C, Lee C-J, Chung Y-T, Sung T-Y, Hsieh M-H. Differential regulation of Arabidopsis plastid gene expression and RNA editing in non-photosynthetic tissues. Plant Mol Biol. 2013;82:375–392. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Picardi E, D’Erchia AM, Montalvo A, Pesole G. Using REDItools to detect RNA editing events in NGS datasets. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2015;49:12.12.1–12.1215. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1212s49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levy S, Schuster G. Polyadenylation and degradation of RNA in the mitochondria. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016;44:1475–1482. doi: 10.1042/BST20160126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lisitsky I, Schuster G. The Chloroplast: From Molecular Biology to Biotechnology. Dordrecht: Springer; 1999. Polyadenylation and Degradation of mRNA in the Chloroplast; pp. 85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Proost S, Van Bel M, Sterck L, Billiau K, Van Parys T, Van de Peer Y, et al. PLAZA: a comparative genomics resource to study gene and genome evolution in plants. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3718–3731. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.071506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong Y, Cole TE, Brasier CM, Buck KW. Evolutionary relationships among putative RNA-dependent RNA polymerases encoded by a mitochondrial virus-like RNA in the dutch elm disease fungus, Ophiostoma novo-ulmi, by other viruses and virus-like RNAs and by the Arabidopsis mitochondrial genome. Virology. 1998;246:158–169. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mizrachi E, Hefer CA, Ranik M, Joubert F, Myburg AA. De novo assembled expressed gene catalog of a fast-growing Eucalyptus tree produced by Illumina mRNA-Seq. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:681–693. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vining KJ, Romanel E, Jones RC, Klocko A, Alves-Ferreira M, Hefer CA, et al. The floral transcriptome of Eucalyptus grandis. New Phytol. 2015;206:1406–1422. doi: 10.1111/nph.13077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu TD, Reeder J, Lawrence M, Becker G, Brauer MJ. GMAP and GSNAP for genomic sequence alignment: enhancements to speed, accuracy, and functionality. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1418:283–334. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3578-9_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith DR. RNA-Seq data: a goldmine for organelle research. Brief Funct Genomics. 2013;12:454–456. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/els066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bock R. Engineering plastid genomes: methods, tools, and applications in basic research and biotechnology. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2015;66:211–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rozefelds AC. Eucalyptus phylogeny and history: a brief summary. TASFORESTS-HOBART. 1996;8:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Folk RA, Mandel JR, Freudenstein JV. Ancestral gene flow and parallel organellar genome capture result in extreme phylogenomic discord in a lineage of angiosperms. Syst Biol. 2017;66:320–337. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syw083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grattapaglia D, Vaillancourt RE, Shepherd M, Thumma BR, Foley W, Külheim C, et al. Progress in Myrtaceae genetics and genomics: Eucalyptus as the pivotal genus. Tree Genet Genomes. 2012;8:463–508. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benson DA, Cavanaugh M, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, et al. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D36–D42. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chase MW, Christenhusz MJM, Fay MF, Byng JW, Judd WS, Soltis DE, et al. An update of the angiosperm phylogeny group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot J Linn Soc. 2016;181:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu G, Cao D, Li S, Su A, Geng J, Grover CE, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of Gossypium hirsutum and evolutionary analysis of higher plant mitochondrial genomes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maier UG, Zauner S, Woehle C, Bolte K, Hempel F, Allen JF, et al. Massively convergent evolution for ribosomal protein gene content in plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5:2318–2329. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woloszynska M. Heteroplasmy and stoichiometric complexity of plant mitochondrial genomes—though this be madness, yet there’s method in't. J Exp Bot. 2009;3:657–671. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shearman JR, Sonthirod C, Naktang C, Pootakham W, Yoocha T, Sangsrakru D, et al. The two chromosomes of the mitochondrial genome of a sugarcane cultivar: assembly and recombination analysis using long PacBio reads. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31533. doi: 10.1038/srep31533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tuskan GA, Difazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & gray) Science. 2006;313:1596–1604. doi: 10.1126/science.1128691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuhn J, Tengler U, Binder S. Transcript lifetime is balanced between stabilizing stem-loop structures and degradation-promoting polyadenylation in plant mitochondria. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:731–742. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.731-742.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hayes R, Kudla JO, Gruissem W. Degrading chloroplast mRNA: the role of polyadenylation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:199–202. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valkov VT, Scotti N, Kahlau S, Maclean D, Grillo S, Gray JC, et al. Genome-wide analysis of plastid gene expression in potato leaf chloroplasts and tuber amyloplasts: Transcriptional and posttranscriptional control. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:2030–2044. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.140483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kahlau S, Bock R. Plastid transcriptomics and translatomics of tomato fruit development and chloroplast-to-chromoplast differentiation: chromoplast gene expression largely serves the production of a single protein. Plant Cell. 2008;20:856–874. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woo HR, Koo HJ, Kim J, Jeong H, Yang JO, Lee IH, et al. Programming of plant leaf senescence with temporal and inter-organellar coordination of transcriptome in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:452–467. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moison M, Roux F, Quadrado M, Duval R, Ekovich M, Lê D-H, et al. Cytoplasmic phylogeny and evidence of cyto-nuclear co-adaptation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2010;63:728–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dobler R, Rogell B, Budar F, Dowling DK. A meta-analysis of the strength and nature of cytoplasmic genetic effects. J Evol Biol. 2014;27:2021–2034. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soltani A, Kumar A, Mergoum M, Pirseyedi SM, Hegstad JB, Mazaheri M, et al. Novel nuclear-cytoplasmic interaction in wheat (Triticum aestivum) induces vigorous plants. Funct Integr Genomics. 2016;16:171–182. doi: 10.1007/s10142-016-0475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roux F, Mary-Huard T, Barillot E, Wenes E, Botran L, Durand S, et al. Cytonuclear interactions affect adaptive traits of the annual plant Arabidopsis thaliana in the field. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:3687–3692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520687113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hahn C, Bachmann L, Chevreux B. Reconstructing mitochondrial genomes directly from genomic next-generation sequencing reads - a baiting and iterative mapping approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Quinlan AR. BEDTools: the Swiss-Army tool for genome feature analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2014;47:11.12.1–11.1234. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1112s47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alverson AJ, Wei X, Rice DW, Stern DB, Barry K, Palmer JD. Insights into the evolution of mitochondrial genome size from complete sequences of Citrullus lanatus and Cucurbita pepo (Cucurbitaceae). Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27(6):1436–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Beck N, Lang BF. MFannot, organelle genome annotation webserver. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dierckxsens N, Mardulyn P, Smits G. NOVOPlasty: de novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;45(4):e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(17):3252–3255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu C, Shi L, Zhu Y, Chen H, Zhang J, Lin X, et al. CpGAVAS, an integrated web server for the annotation, visualization, analysis, and GenBank submission of completely sequenced chloroplast genome sequences. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:715. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Protsyuk IV, Grekhov GA, Tiunov AV, Fursov MY. Shared bioinformatics databases within the Unipro UGENE platform. J Integr Bioinform. 2015;12:257. doi: 10.2390/biecoll-jib-2015-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lohse M, Drechsel O, Kahlau S, Bock R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW—a suite of tools for generating physical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes and visualizing expression data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W575–W581. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative genomics viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq: Analysing high-throughput sequencing data with Python; 2010.

- 83.Love M, Anders S, Huber W. Differential analysis of count data–the DESeq2 package. Genome Biol. 2014; https://bioc.ism.ac.jp/packages/3.3/bioc/vignettes/DESeq2/inst/doc/DESeq2.pdf.

- 84.Team RS. RStudio: integrated development for R. Boston: RStudio, Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag New York; 2009. http://ggplot2.org.

- 86.Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2009;20(1):4.10.1-4.10.14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. E. grandis mitochondrial and plastid genome short repeat elements overview (DOCX 13 kb)

Excel spreadsheet of the results of UniPro UGENE analysis of large (length > 100 bp, identity > 95%) repeats in the Eucalyptus grandis mitochondrial genome. (XLSX 10 kb)

Excel spreadsheet of the results of SVDetect analysis results showing breakpoints of structural variants in the E. grandis mitochondrial genome (Sheet 1), and breakpoints within 250 bp of mitochondrial genome large repeat regions (Sheet 2). (XLSX 14 kb)

Figure S1. Discordantly mapped read pairs flanking direct repeat 13 of the mitochondrial genome. The insert size of the reads is ~ 118,000 bp, compared to the expected 475. These reads suggest a repeat mediated structural variation, supported by SVDetect analysis. Read pair insert is shown by the red lines and the direct repeat is shown in the blue track. (PDF 51 kb)

Figure S2. Mitochondrial genome gene order comparison between Eucalyptus grandis and Lagerstroemia indica. The gene order for the E. grandis mitochondrial genome is shown at the right of the figure, and that of L. indica on the top. Genes that are not found in each genome are indicated with red text. Collinear genes are indicated by red boxes. (PDF 29 kb)

Figure S3. Multiple whole genome alignment of selected land plant mitochondrial genomes. Alignment was performed using the progressiveMauve algorithm in Mauve multiple alignment tool [87], with the coloured blocks representing Locally Collinear Blocks of sequences between genomes. The red lines indicate the length of the mitochondrial genomes, and the name of the organism is shown at the bottom of each genome. This figure shows the widespread genome rearrangements present in plant mitochondrial genomes. (PDF 286 kb)

Excel spreadsheet of the results of predicted editing sites in the E. grandis mitochondrial (Sheet 1) and plastid (Sheet 2) genomes using PREPACT, PREP-suite, and REDItools, labelled by position of the edit in the coding sequence. (XLSX 38 kb)

Figure S4. Number of predicted C to U editing sites in the mitochondrial and plastid genomes of E. grandis using PREPACT, PREP-suite, and REDITOOLS mRNA editing detection of polyA-selected reads. a. Number of editing sites (y-axis) in E. grandis mitochondrial genes (x-axis) as predicted by PREP-Mt (blue), PREPACT (orange), and evidence from bulked polyA-selected reads from three samples each of eight tissues in E. grandis using REDItools (DNA-RNA algorithm: minimum read depth = 10, minimum amount of reads per editing event = 3) shown in grey. b. Number of editing sites (y-axis) in E. grandis plastid genes (x-axis) as predicted by PREP-Cp (blue), PREPACT (orange), and evidence from polyA-selected reads using REDItools (grey). These figures show that bulked polyA selected reads are sufficient to detect the majority of predicted editing events in land plants, however the read depth lower than would be detected with total RNA sequencing. c. Number of predicted editing sites in common between PREP-Mt, PREPACT, and REDItools in the E. grandis mitochondrial genome. d. Number of predicted editing sites in common between PREP-Cp, PREPACT, and REDItools in the E. grandis plastid genome. (PDF 52 kb)

Table S2. Amount of E. grandis organellar DNA transfer to nuclear chromosomes (DOCX 13 kb)

Table S3. Inter-organellar DNA transfers in E. grandis show regions of high homology between E. grandis plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Additional BLAST analysis with land plant organellar genomes show that the transferred regions are all transferred from the plastid to the mitochondria (see Additional file 11). (DOCX 14 kb)

Excel spreadsheet of the origin of inter-organellar DNA transfers, showing the organellar genomes of sequenced land plants, and the results of BLAST analysis of E. grandis mitochondrial genome (TAG0014_chr_M) regions that have significant homology to the E. grandis plastid genome. Note that all mitochondrial genomes analysed have no significant matches to the transferred regions, suggesting that there is no transfer of DNA from the mitochondrial genome to the plastid genome. (XLSX 667 kb)

Excel spreadsheet of nuclear genes of organellar origin for mRNA-sequencing read mapping by homology using BLAST analysis (> 80% full length of gene matches with > 90% identity to organellar genome) or by annotation (annotation closest match is Arabidopsis thaliana organellar gene). (XLSX 13 kb)

Figure S5. Sashimi plot of polyA-selected mRNA reads mapped to Eucgr.E01203 in E. grandis mature leaf tissue. The plot shows the count of reads (0 to 105) aligned to the annotated gene regions of Eucgr.E01203. Reads were aligned using GSNAP and visualized in the Integrated Genome Viewer. Black lines show the annotated gene regions, and thicker black bars show the annotated protein coding regions. The plot shows that the read coverage of Eucgr.E01203 across the protein coding regions is lower than in the 5’ UTR, indicating that the VST counts generated for this gene do not represent functional gene expression. (PNG 14 kb)

Table S4. Differently expressed organellar encoded genes in E. grandis where negative log2 fold change values indicate increased polyA selected RNA read abundance in mature leaf compared to immature xylem. (DOCX 14 kb)

Data Availability Statement

FastQ files of the whole genome sequencing of E. grandis TAG0014 mature leaf tissue are available at the Sequence Read Archive under the project accession PRJNA433608 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/study/?acc=PRJNA433608). Mitochondrial and plastid genome sequences and annotations have been submitted to the NCBI Genbank database and can be found under accession number NC_040010.1 for the mitochondria (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/browse/?report=5#!/organelles/NC_040010), and MG925369.1 for the plastid (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MG925369).