Abstract

Background

Stable angina pectoris is a chronic medical condition with significant impact on mortality and quality of life; it can be macrovascular or microvascular in origin. Ranolazine is a second‐line anti‐anginal drug approved for use in people with stable angina. However, the effects of ranolazine for people with angina are considered to be modest, with uncertain clinical relevance.

Objectives

To assess the effects of ranolazine on cardiovascular and non‐cardiovascular mortality, all‐cause mortality, quality of life, acute myocardial infarction incidence, angina episodes frequency and adverse events incidence in stable angina patients, used either as monotherapy or as add‐on therapy, and compared to placebo or any other anti‐anginal agent.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and the Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science in February 2016, as well as regional databases and trials registers. We also screened reference lists.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which directly compared the effects of ranolazine versus placebo or other anti‐anginals in people with stable angina pectoris were eligible for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected studies, extracted data and assessed risk of bias. Estimates of treatment effects were calculated using risk ratios (RR), mean differences (MD) and standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using a fixed‐effect model. Where we found statistically significant heterogeneity (Chi² P < 0.10), we used a random‐effects model for pooling estimates. Meta‐analysis was not performed where we found considerable heterogeneity (I² ≥ 75%). We used GRADE criteria to assess evidence quality and the GRADE profiler (GRADEpro GDT) to import data from Review Manager 5.3 to create 'Summary of findings' tables.

Main results

We included 17 RCTs (9975 participants, mean age 63.3 years). We found very limited (or no) data to inform most planned comparisons. Summary data were used to inform comparison of ranolazine versus placebo. Overall, risk of bias was assessed as unclear.

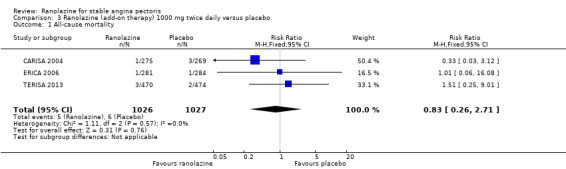

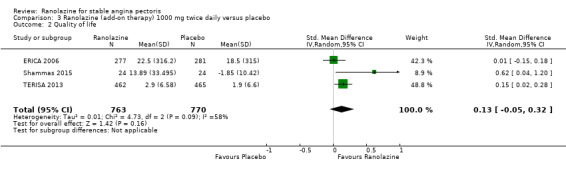

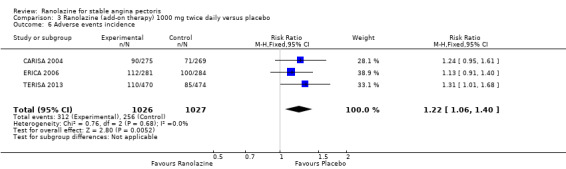

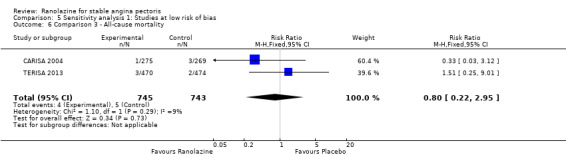

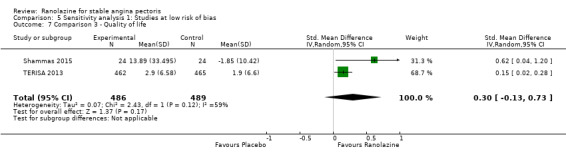

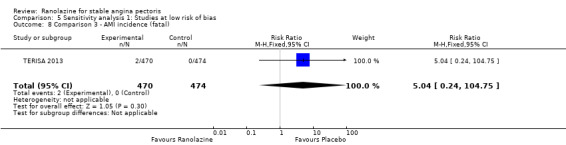

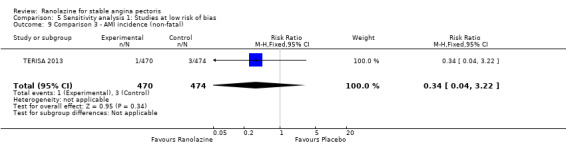

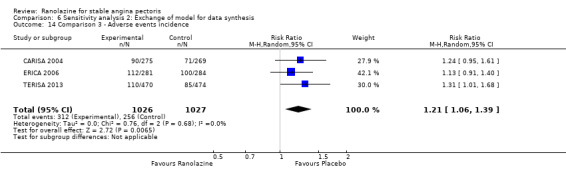

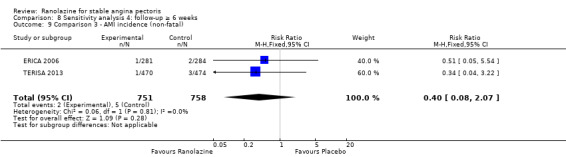

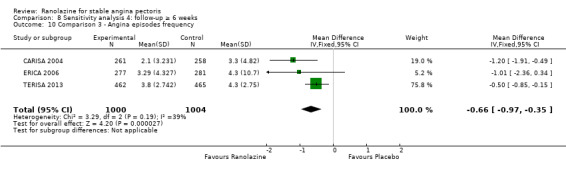

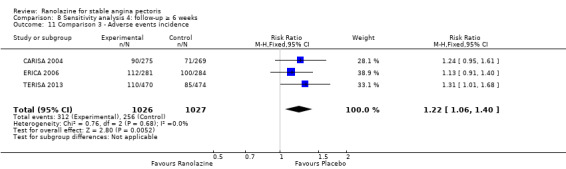

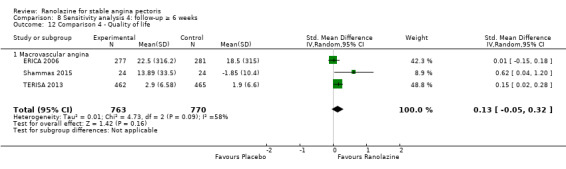

For add‐on ranolazine compared to placebo, no data were available to estimate cardiovascular and non‐cardiovascular mortality. We found uncertainty about the effect of ranolazine on: all‐cause mortality (1000 mg twice daily, RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.26 to 2.71; 3 studies, 2053 participants; low quality evidence); quality of life (any dose, SMD 0.25, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.52; 4 studies, 1563 participants; I² = 73%; moderate quality evidence); and incidence of non‐fatal acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (1000mg twice daily, RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.08 to 2.07; 2 studies, 1509 participants; low quality evidence). Add‐on ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily reduced the fervour of angina episodes (MD ‐0.66, 95% CI ‐0.97 to ‐0.35; 3 studies, 2004 participants; I² = 39%; moderate quality evidence) but increased the risk of non‐serious adverse events (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.40; 3 studies, 2053 participants; moderate quality evidence).

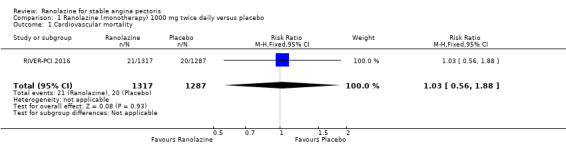

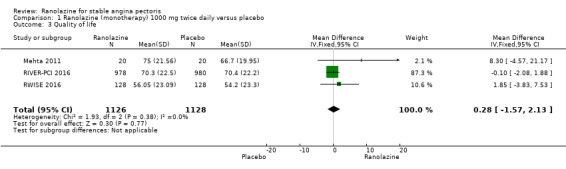

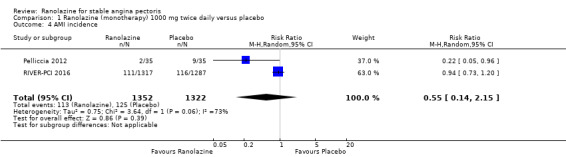

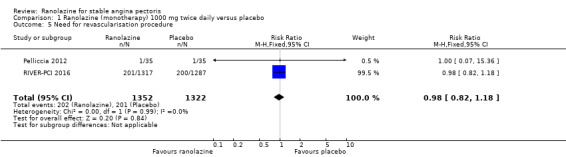

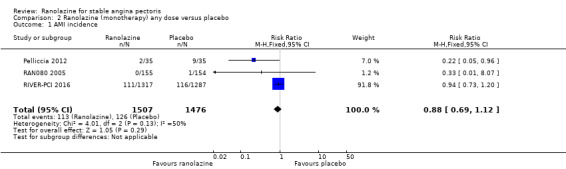

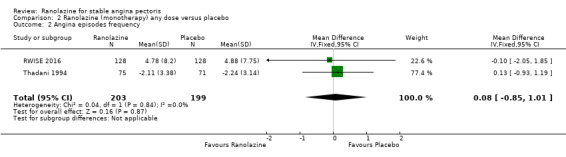

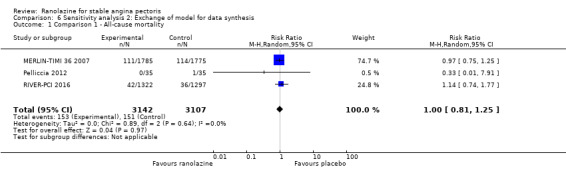

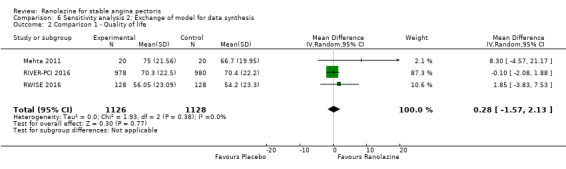

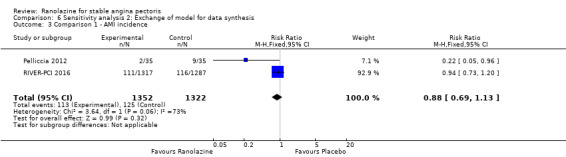

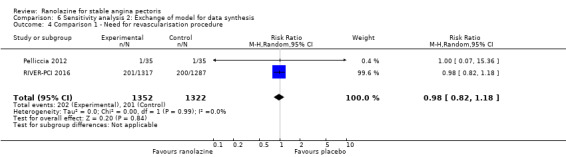

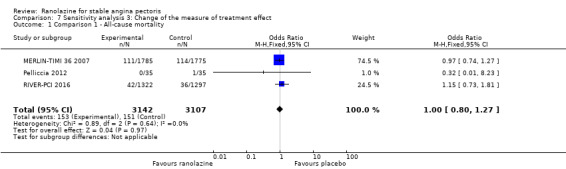

For ranolazine as monotherapy compared to placebo, we found uncertain effect on cardiovascular mortality (1000 mg twice daily, RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.88; 1 study, 2604 participants; low quality evidence). No data were available to estimate non‐cardiovascular mortality. We also found an uncertain effect on all‐cause mortality for ranolazine (1000 mg twice daily, RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.25; 3 studies, 6249 participants; low quality evidence), quality of life (1000 mg twice daily, MD 0.28, 95% CI ‐1.57 to 2.13; 3 studies, 2254 participants; moderate quality evidence), non‐fatal AMI incidence (any dose, RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.12; 3 studies, 2983 participants; I² = 50%; low quality evidence), and frequency of angina episodes (any dose, MD 0.08, 95% CI ‐0.85 to 1.01; 2 studies, 402 participants; low quality evidence). We found an increased risk for non‐serious adverse events associated with ranolazine (any dose, RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.12 to 2.00; 3 studies, 947 participants; very low quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

We found very low quality evidence showing that people with stable angina who received ranolazine as monotherapy had increased risk of presenting non‐serious adverse events compared to those given placebo. We found low quality evidence indicating that people with stable angina who received ranolazine showed uncertain effect on the risk of cardiovascular death (for ranolazine given as monotherapy), all‐cause death and non‐fatal AMI, and the frequency of angina episodes (for ranolazine given as monotherapy) compared to those given placebo. Moderate quality evidence indicated that people with stable angina who received ranolazine showed uncertain effect on quality of life compared with people who received placebo. Moderate quality evidence also indicated that people with stable angina who received ranolazine as add‐on therapy had fewer angina episodes but increased risk of presenting non‐serious adverse events compared to those given placebo.

Plain language summary

Ranolazine for people with stable angina pectoris

Review question

We wanted to find out if ranolazine (a drug to prevent angina) was more effective than a fake drug (placebo) or other drugs to treat stable angina.

Background

Angina pectoris is sudden chest pain caused when the heart does not get enough oxygen or from other stresses. People with stable angina have a predictable pattern of when they experience angina symptoms. Angina is made worse by physical effort and relieved by rest or some medications. Ranolazine is a relatively new drug for people with angina pectoris who are already taking other drugs to treat angina.

Search date

The evidence is current to February 2016.

Study funding sources

Most studies were either fully (9/17) or partly (3/17) funded by drug companies, two received no external funding, and three did not declare sources of funding.

Study characteristics

We included 17 studies that involved a total of 9975 adult participants and lasted between 1 and 92 weeks.

Key results

We only compared ranolazine and placebo because there were few data for other comparisons. The evidence was uncertain about the effect of ranolazine 1000 mg given alone twice daily to people with stable angina pectoris on the chance of dying from heart‐related causes. There was no evidence about whether ranolazine changed the risk of dying from causes that were not heart‐related.

Although the evidence was uncertain about the effect of ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily on the chance of dying from any cause, quality of life, the possibility of heart attack or the frequency of angina attacks (for ranolazine taken alone), ranolazine did modestly reduce the numbers of angina attacks per week when given with other anti‐angina drugs. Ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily increased the risk for experiencing dizziness, nausea and constipation from taking the drug (mild adverse events).

Quality of evidence

Overall, evidence quality was assessed as very low for the chance of mild adverse events (for people who took ranolazine alone). Evidence was also low for estimating the chance of death from heart‐related (when ranolazine is taken alone) or any causes, having a heart attack, and how often angina attacks occur (when ranolazine is taken alone). We found moderate quality evidence about quality of life, frequency of angina attacks and the chance of experiencing mild adverse events (for people who took ranolazine together with other anti‐angina drugs),

Low evidence quality related to problems and reporting of study methods and too few data to calculate precise estimates.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Ranolazine (add‐on therapy) versus placebo for stable angina pectoris.

| Ranolazine (add‐on therapy) versus placebo for stable angina pectoris* | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with stable angina pectoris Settings: not specified Intervention: ranolazine (add‐on therapy) Comparison: placebo (add‐on therapy) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks** (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Ranolazine | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were available for this outcome |

| Non‐cardiovascular mortality ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were available for this outcome |

| All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: 42 to 84 days | 6 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (2 to 16) | RR 0.83 (0.26 to 2.71) | 2053 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low¹ ² | Ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily |

| Quality of life Scale: 0 to 100. Follow‐up: 28 to 56 days | Mean quality of life in control group participants was 44.3 points | Mean quality of life in intervention group participants was 0.25 standard deviations higher (0.01 lower to 0.52 higher) | 1563 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate³ | Ranolazine any dose (SMD 0.25, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.52) |

|

| AMI incidence Follow‐up: 42 to 56 days | 7 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (1 to 14) | RR 0.40 (0.08 to 2.07) | 1509 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low⁴ | Ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily |

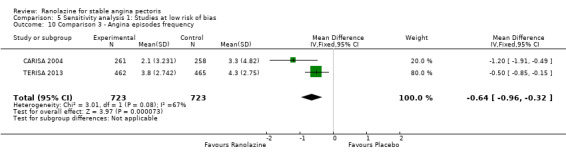

| Angina episodes frequency Follow‐up: 42 to 84 days | Mean angina episode frequency in control group participants was 4.1 episodes per week | Mean angina episodes frequency in intervention group participants was 0.66 lower (0.97 to 0.35 lower) | 2004 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate¹ | Ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily (MD ‐0.66, 95% CI ‐0.97 to ‐0.35) |

|

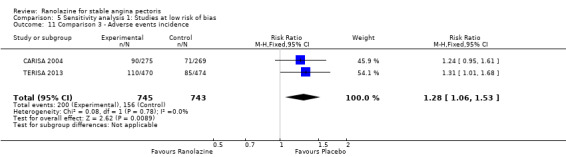

| Adverse events incidence Follow‐up: 42 to 84 days | 241 per 1000 | 294 per 1000 (256 to 337) | RR 1.22 (1.06 to 1.4) | 2123 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate⁵ | Ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily |

| *Add‐on therapy: refers to the addition of ranolazine to an antianginal regimen already in course. The results reported correspond to the comparisons (data and analyses) 3 and 4 of the review (involving ranolazine given at 1000mg twice daily or any dosage); this is specified in the Comments column. **The assumed risk is based on the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹ Quality of evidence was downgraded one level due to unclear risk of bias regarding blinding of outcome assessment and incomplete outcome data ² Quality of evidence was downgraded one level due to insufficient number of events (less than 300), and the 95% confidence interval around the pooled effect includes both 1) no effect and 2) appreciable benefit/harm ³ Quality of evidence was downgraded one level due to substantial heterogeneity ⁴ Quality of evidence was downgraded two levels due to insufficient number of events (less than 300), and the 95% confidence interval around the pooled effect includes both 1) no effect and 2) appreciable benefit/harm ⁵ Quality of evidence was downgraded one level due to unclear risk of bias regarding blinding of outcome assessment and selective reporting

Summary of findings 2. Ranolazine (monotherapy) versus placebo for stable angina pectoris.

| Ranolazine (monotherapy) versus placebo for stable angina pectoris* | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with stable angina pectoris Settings: not specified Intervention: ranolazine (monotherapy) Comparison: placebo (monotherapy) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks** (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Ranolazine | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality Follow‐up: mean 643 days | 16 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (9 to 29) | RR 1.03 (0.56 to 1.88) | 2604 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low¹ ² | Ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily |

| Non‐cardiovascular mortality ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data were available for this outcome |

| All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: 37 to 643 days | 49 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (39 to 61) | RR 1.00 (0.81 to 1.25) | 6249 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low² ³ | Ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily |

| Quality of life Scale: 0 to 100 Follow‐up: 14 to 643 days | Mean quality of life in control group participants was 68.6 points | Mean quality of life in intervention group participants was 0.28 higher (1.57 lower to 2.13 higher) | 2256 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate⁴ | Ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily (MD 0.28. 95% CI ‐1.57 to 2.13) |

|

| AMI incidence Follow‐up: 7 to 643 days | 85 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (59 to 96) | RR 0.88 (0.69 to 1.12) | 2983 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Ranolazine any dose |

| Angina episodes frequency Follow‐up: 14 to 28 days | Mean angina episode frequency in control group participants was 2.08 episodes per week | Mean angina episode frequency in intervention group participants was 0.08 higher (0.85 lower to 1.01 higher) | 402 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low³ ⁵ | Ranolazine any dose (MD 0.08, 95% CI ‐0.85 to 1.01) |

|

| Adverse events incidence Follow‐up: 7 to 14 days | 131 per 1000 | 197 per 1000 (147 to 262) | RR 1.50 (1.12 to 2) | 947 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low³ ⁵ ⁶ | Ranolazine any dose |

| *Monotherapy: refers to the administration of ranolazine as the only antianginal drug. The results reported correspond to the comparisons (data and analyses) 1 and 2 of the review (involving ranolazine given at 1000mg twice daily or any dosage); this is specified in the Comments column. **The assumed risk is based on the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹ Quality of evidence was downgraded one level due to unclear risk of bias regarding allocation concealment and high risk of bias regarding selective reporting ² Quality of evidence was downgraded one level due to insufficient numbers of events (< 300), and the 95% CI around the pooled effect includes both 1) no effect and 2) appreciable benefit/harm ³ Quality of evidence was downgraded one level because a group of participants (not quantified) in one or more included studies received ranolazine in addition to usual anti‐anginals (i.e. not as monotherapy) ⁴ Quality of evidence was downgraded one level because the 95% CI around the pooled effect included both 1) no effect and 2) appreciable benefit/harm ⁵ Quality of evidence was downgraded one level due to unclear risk of bias for most criteria ⁶ Quality of evidence was downgraded one level due to insufficient numbers of events (< 300)

Background

Description of the condition

Stable angina pectoris is a chronic medical condition which is generally regarded as the main symptomatic manifestation of coronary artery disease (CAD) (NICE 2011). It has been estimated that stable angina affects 58% of people with CAD (Ohman 2016), with an annual mortality rate ranging between 1.2% and 2.4% (ESC 2013). Apart from its associated risk of cardiovascular death and recurrent myocardial infarction, stable angina pectoris has a significant impact on functional capacity and quality of life (Scirica 2009). Mortality is higher among people with angina than those with no history of CAD at baseline (O'Toole 2008). Factors associated with a poorer prognosis include more severe symptoms, male sex, abnormal resting electrocardiogram (ECG) and previous myocardial infarction (O'Toole 2008).

A universal definition for stable angina has not been agreed internationally, but it is usually recognised clinically by its character, location and relationship to provocative stimuli (NICE 2010). Angina pain is identified by: constricting discomfort in the chest or neck, shoulders, jaw or arms; precipitated by physical exertion; and relieved by rest or nitrates within about 5 to 10 minutes. Typical angina is defined by the presence of all of these features (NICE 2010). The underlying cause is of angina pectoris is usually macrovascular CAD, but may be microvascular in some people (ESC 2013). Importantly, other (non CAD) cardiac conditions may be responsible for typical anginal pain, including aortic valve disease and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (NICE 2010). Macrovascular CAD refers to dysfunction of the coronary arteries and their main branches, as opposed to microvascular CAD in which dysfunction involves the small coronary arterioles (< 500 μm) (Jones 2012).

Diagnosis of stable angina due to CAD can be established based solely on clinical assessment or with the aid of additional diagnostic testing (NICE 2010). Basic tests usually involve biochemical tests, resting ECG, echocardiography, etc. Non‐invasive diagnostic tests include exercise ECG, stress imaging testing and coronary computed‐tomography angiography (CTA). The only invasive test is invasive coronary angiography (ESC 2013). The choice of diagnostic test (functional or structural, invasive or non‐invasive) is guided by the estimated likelihood of CAD (from clinical assessment) and consideration of coronary revascularisation (NICE 2010). Although current NICE guidelines do not recommend exercise ECG to evaluate people with suspected stable angina, it remains a useful option because of its simplicity and widespread availability (ESC 2013). Furthermore, according to American (ACC/AHA 2012) and European (SIGN 2007; ESC 2013) guidelines, exercise ECG is recommended as an option to impose stress during imaging for people with intermediate pre‐test probability of CAD. Some people with stable angina have microvascular coronary disorders, which can be detected on normal coronary angiography only (Di Fiore 2013). Since evaluation of a person with stable angina does not always include coronary angiography (either invasive or non‐invasive), people with microvascular coronary dysfunction would remain unidentified using this approach.

Description of the intervention

Management options for people with stable angina include lifestyle modifications, pharmacological therapy, and revascularisation interventions. Treatment is aimed at improving prognosis (by preventing myocardial infarction and death) and minimising or abolishing symptoms. All management options have potential to meet both treatment aims (ESC 2013). However, the main aim of anti‐anginal drug treatment is to prevent episodes of angina; the secondary aim is to prevent cardiovascular events such as heart attack and stroke (NICE 2011). Anti‐anginal drugs are classified as first‐line (adrenergic beta antagonists, calcium channel blockers) or second‐line (long‐acting nitrates, ivabradine, nicorandil, ranolazine, trimetazidine) (Tarkin 2012). Anti‐angina treatment is recommended to begin using one of the first‐line drugs as monotherapy. If symptoms are not controlled satisfactorily, a combination of two first‐line drugs is recommended. Second‐line drugs are recommended as add‐on therapy when a combination of two first‐line drugs cannot be accomplished, or as monotherapy when none of the first‐line drugs can be used (ESC 2013; NICE 2011). Adding a third anti‐angina drug can be considered only when revascularisation is not an option or as a temporary measure while the patient awaits revascularisation (NICE 2011). However, since ranolazine is the only second‐line drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Hawwa 2013), American guidelines (ACC/AHA 2012) recommend use of ranolazine in a similar way to second‐line drugs in European guidelines (ESC 2013).

Ranolazine was approved by the US FDA in 2007 for use in a maximum dose (extended release) of 1000 mg twice daily (FDA 2016), and by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2008 for use in a maximum dose (prolonged release) of 750 mg twice daily (EMA 2008). The immediate release presentation shows peak plasma concentrations within one hour, with an estimated half‐life of 1.4 hours to 1.9 hours (Jerling 2006); for the extended release presentation, values are 2 hours to 6 hours and 7 hours, respectively (Cattaneo 2015; Jerling 2006). The ranolazine extended release preparation reduces the frequency of angina episodes, improves exercise performance, and delays the development of exercise‐induced angina and ST‐segment depression (ACC/AHA 2012). Although these effects are considered to be dose‐related (Chaitman 2011), they have been observed to be modest (EMA 2008) and of uncertain clinical significance (NICE 2011). Furthermore, there is no evidence about the effects of ranolazine on long‐term outcomes in people with stable angina, or for the addition of ranolazine to a calcium channel blocker (NICE 2011). Conversely, an advantage of ranolazine is that it does not cause significant haemodynamic changes, with an average of less than 2 beats per minute reduction in heart rate and less than 3 mm Hg decrease in systolic blood pressure (ACC/AHA 2012). However, ranolazine is associated with a dose‐dependant increase in QT‐interval, with a mean increase of 6 ms at the maximum recommended dosing (ACC/AHA 2012). More recently, an anti‐arrhythmic (antifibrillatory) effect of ranolazine has been proposed, but current evidence is based on small, non‐controlled trials (Hawwa 2013). Contra‐indications to ranolazine are prolonged QT‐interval and co‐administration with other QT‐prolonging drugs, previous history of ventricular tachycardia and moderate to severe kidney impairment or severe liver failure (Tarkin 2012). The most common adverse events related to use of ranolazine are headache (5.5%), dizziness (1% to 6%), constipation (5%) and nausea (≤ 4%; dose related). Although there is concern about QT prolongation on ECG, its prevalence has been estimated to be less than 1% (Ranexa PI 2013).

How the intervention might work

Ranolazine is a selective inhibitor of the late sodium current (INaL) in cardiomyocytes, which is thought to be an important contributor to the pathogenesis of angina through calcium overload and increase in oxygen consumption in the cardiomyocytes (Codolosa 2014). Although most studies have focused on its role in macrovascular angina, some findings suggest that ranolazine also has anti‐inflammatory or antioxidant effects which may improve glycometabolic homeostasis, which are more important in microvascular angina (Cattaneo 2015).

Early studies on the effects of ranolazine in people with stable angina have been undertaken using the drug's immediate release formulation. However, given that its action was deemed significant only in the peak measurements, an extended release formulation was developed, which was approved for use in people with stable angina (Keating 2008). Overall, ranolazine has been shown to improve exercise tolerance test (ETT) parameters and angina frequency in people with stable angina without substantial haemodynamic effect (Savarese 2013). However, ranolazine has also been related to prolongation of the QTc interval, although not pro‐arrhythmic at therapeutic doses (Thadani 2012). Moreover, ranolazine has been shown to have anti‐arrhythmic effects by reducing atrial and ventricular arrhythmias (Hawwa 2013).

A number of subgroup analyses have been performed for ranolazine in people with stable angina. The effects of ranolazine on ETT parameters have been found to be greater among women. However, the effects of ranolazine on decreased angina frequency and nitroglycerin consumption were comparable among the gender groups (Wenger 2007). Differences among age groups have been evaluated. Although ranolazine efficacy is similar among people aged 70 years or older and patients younger than 70 years, its safety profile was better in the younger age group (Rich 2007). Differences between diabetic and non‐diabetic patients have also been sought. Although ranolazine has not been found to have a different effect for people with diabetes regarding ETT parameters, angina frequency and nitroglycerin consumption, it was related to a significant reduction in HbA1c levels (Patel 2008).

Why it is important to do this review

Although ranolazine reduces angina episodes and improves ETT parameters, its impact on the long‐term prognosis in people with stable angina remains unclear. Moreover, the clinical significance of those effects is a matter of debate (NICE 2011). Even though the main indication for ranolazine in people with stable angina is as add‐on therapy, the evidence regarding its use in combination with some first‐line drugs is lacking (NICE 2011). More evidence is needed on the use of ranolazine as monotherapy, given that it may provide an option for people who cannot use any of the first‐line drugs (ESC 2013; NICE 2011) or recommended as a first‐line drug given its apparently better side effects profile compared with classical anti‐anginal agents (ACC/AHA 2012). In view of these gaps in the knowledge of the role of ranolazine for the management of people with stable angina, a systematic analysis of relevant, high quality, and up‐to‐date evidence was needed.

Objectives

To assess the effects of ranolazine on cardiovascular and non‐cardiovascular mortality, all‐cause mortality, quality of life, acute myocardial infarction incidence, angina episodes frequency and adverse events incidence in stable angina patients, used either as monotherapy or as add‐on therapy, and compared to placebo or any other anti‐anginal agent.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised, controlled, parallel‐group and cross‐over trials, with double blinding (of participants and trial personnel) that assessed the effects of ranolazine in the management of stable angina pectoris, irrespective of the number of groups and the length of follow‐up. However, for safety outcomes, we also included trials regardless of blinding so long as other criteria were met. We included studies reported as full‐text, those published only as abstracts, and unpublished data.

Types of participants

We included adults (aged 18 years or over) diagnosed with stable angina pectoris, irrespective of gender, country of enrolment, setting, previous treatment status, comorbidities and symptom severity. The diagnosis of stable angina pectoris could be established based on clinical history, myocardial ischaemia demonstrated by functional tests or significant obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) demonstrated by angiography. We considered studies which included a subset of relevant participants if results were reported separately for people with stable angina.

Types of interventions

We included trials comparing ranolazine (given orally for at least one week as either monotherapy or add‐on therapy, irrespective of dose, presentation (immediate or extended release) and daily frequency) with placebo or other anti‐anginal agent. We included the following co‐interventions provided they were not part of the randomised treatment: other anti‐anginal agents (long‐acting nitrates, adrenergic beta antagonists and/or calcium channel blockers), statins, antiplatelet agents, antihypertensive agents and surgical interventions for CAD. We included trials that applied the following designs.

Monotherapy

Ranolazine versus placebo.

Ranolazine versus first‐line anti‐anginal drugs, grouped by class: 1) adrenergic beta antagonists and 2) calcium channel blockers.

Ranolazine versus other second‐line anti‐anginal drugs, grouped as: 1) long‐acting nitrates, 2) ivabradine, 3) nicorandil and 4) trimetazidine.

Add‐on therapy

Ranolazine added to first‐line anti‐anginal drugs (grouped by class as for monotherapy) versus placebo added to first‐line anti‐anginal drugs (grouped by class).

Ranolazine added to other second‐line anti‐anginal drugs (grouped as for monotherapy) versus placebo added to other second‐line anti‐anginal drug (grouped).

Ranolazine added to first‐line anti‐anginal drugs (grouped as for monotherapy) versus other second‐line anti‐anginal drugs (grouped as mentioned before) added to first‐line anti‐anginal drugs (grouped).

Ranolazine added to other second‐line anti‐anginal drugs (grouped as for monotherapy) versus first‐line anti‐anginal drugs (grouped) added to other second‐line anti‐anginal drugs (grouped).

Types of outcome measures

We considered effectiveness and safety outcome measures, and only measures taken at the longest follow‐up within each study. For the outcomes considered, we included only results measured with a follow‐up of at least one week. Studies were included irrespective of whether or not they assessed the outcomes listed below.

Primary outcomes

Effectiveness

Cardiovascular mortality, expressed as a proportion of the total study population.

Safety

Non‐cardiovascular mortality, expressed as a proportion of the total study population.

Secondary outcomes

Effectiveness

All‐cause mortality, expressed as a proportion of the total study population.

Quality of life, measured using general scales: Medical Outcomes Study Short Form‐36 (SF‐36), World Health Organization Quality of Life tool (WHOQOL), Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ) and Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) (Silva 2011); or specific scales: Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ), MacNew Heart Disease Health‐Related QoL Questionnaire, Ferrans and Powers QoL Index and Speak from the Heart Chronic Angina Checklist (Young 2013); all were expressed as mean differences (MDs).

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) incidence (fatal and non‐fatal), defined as the proportion of participants who experienced one or more AMI episodes, expressed separately for fatal and non‐fatal AMI.

Need for revascularisation procedure, expressed as a proportion of the total study population.

Angina episodes frequency, measured as a weekly average, expressed as MDs.

Costs of health care. We considered any information regarding costs of study interventions and related medical care (hospitalisations, additional interventions and outpatient health care).

Time to 1‐mm ST‐segment depression on exercise electrocardiogram (ECG) at peak, measured in seconds, expressed as MDs.

Safety

Adverse events incidence, defined as the proportion of participants who experienced one or more serious (non‐cardiac life‐threatening) or non‐serious events, expressed as a whole but separately for each category. Serious adverse events were defined as those that threaten life, require or prolong hospitalisation, result in permanent disability, or cause birth defects (Cochrane Glossary).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 2016, searched 9 February 2016);

MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations and MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 9 February 2016);

Embase (Ovid, 1980 to 2016 week 6, searched 9 February 2016); and

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science (CPCI‐S Web of Science, 1990 to 9 February 2016).

The detailed MEDLINE search strategy is presented in Appendix 1. We adapted the MEDLINE search strategy for other databases (Appendix 1). The Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials, sensitivity‐maximising version, was applied to MEDLINE and adapted for Embase and CPCI‐S (Lefebvre 2011). We searched these databases from dates of inception to 9 February 2016 and did not apply language restrictions.

Searching other resources

In an effort to identify further ongoing, unpublished and published trials (Van Enst 2012) we also searched the following resources (Higgins 2011):

-

National and regional databases:

African Index Medicus (AIM, Africa) (http://indexmedicus.afro.who.int/) (1966 to 24 April 2016);

Informit Health Collection (Australasia) (http://www.informit.com.au/health.html) (1846 to 24 April 2016);

VIP Information/Chinese Scientific Journals Database (CSJD‐VIP, China) (http://www.cqvip.com/) (from inception to 24 April 2016);

Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region (IMEMR, Eastern Mediterranean); (http://www.emro.who.int/information‐resources/imemr‐database/) (1966 to 24 April 2016);

IndMED (India) (http://indmed.nic.in/indmed.html) (1980 to 24 April 2016);

KoreaMed (Korea) (http://www.koreamed.org/SearchBasic.php) (1959 to 24 April 2016);

LILACS (Latin America and the Caribbean) (http://lilacs.bvsalud.org/es/) (1980 to 24 April 2016);

Index Medicus for South‐East Asia Region (IMSEAR, DSpace, South‐East Asia) (http://imsear.hellis.org/) (1871 to 24 April 2016); and

Western Pacific Region Index Medicus (WPRIM, Western Pacific) (http://www.wprim.org/) (1950 to 24 April 2016).

-

Grey literature databases:

OpenGrey (Europe, formerly OpenSIGLE (Stock 2011)) (http://www.opengrey.eu/) (1973 to 24 April 2016); and

National Technical Information Service (NTIS, U.S.) (http://www.ntis.gov/) (1851 to 24 April 2016).

-

Prospective trial registers search portals:

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (http://www.who.int/ictrp/en/) (1 January 1990 to 24 April 2016);

MetaRegister of Current Controlled Trials (mRCT) (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/mrct/) (6 April 2000 to 24 April 2016); and

ClinicalTrials.gov (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) (3 November 1999 to 24 April 2016).

-

Conference abstracts:

American Heart Association Scientific Sessions from 2009 to February 2016 (http://my.americanheart.org/professional/Sessions/ScientificSessions/Archive/Archive‐Scientific‐Sessions_UCM_316935_SubHomePage.jsp); and

European Society of Cardiology Congresses from 2007 to February 2016 (http://www.escardio.org/congresses/past_congresses/Pages/Past‐Congresses.aspx).

-

Other reviews: checking studies included in other relevant reviews retrieved from searches of:

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) through the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/) (1975 to 24 April 2016);

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) through the CRD (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/) (1975 to 24 April 2016); and

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA Database) through the CRD (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/) (1975 to 24 April 2016).

Approval documents from the US Food and Drrug Administration (FDA) (http://www.fda.gov/) and the European Medcines Agency (EMA) (http://www.ema.europa.eu/), checked on 24 April 2016.

Checking reference lists of included studies and other relevant papers identified through the search process.

The website of Gilead Sciences (http://www.gilead.com/), the company which discovered, developed and commercialised ranolazine, checked on 24 April 2016.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

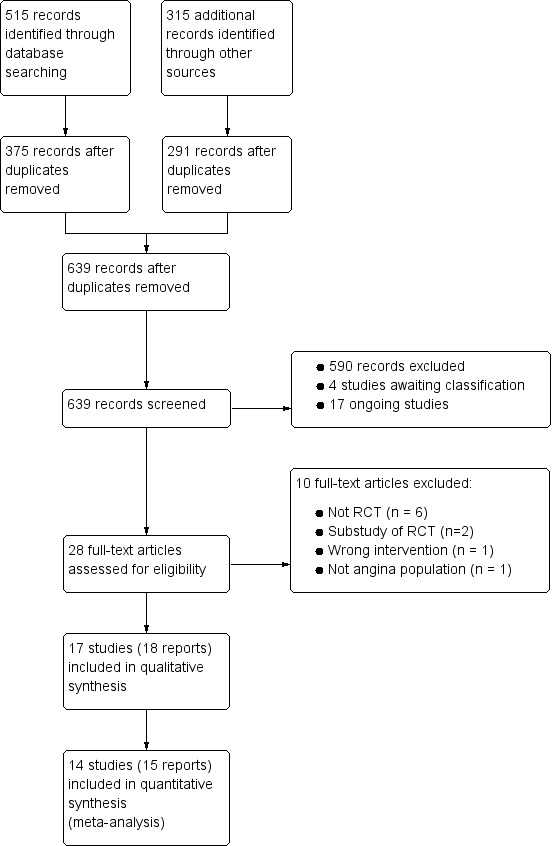

Two review authors (LV, JM) independently screened titles and abstracts for inclusion identified from searches, and coded them as 'retrieve' (eligible or potentially eligible/unclear) or 'do not retrieve'. Disagreements were resolved by arbitration involving a third review author (JB). We retrieved full‐text study reports and publications; two review authors (LV, JM) then independently screened the studies for inclusion, and recorded reasons for exclusion of ineligible studies. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, or if required, the participation of a third review author (JB or CS). We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in this Cochrane review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) and Characteristics of excluded studies table.

1.

Study flow diagram

†Two included articles report data from the RIVER‐PCI trial

Data extraction and management

We used a data collection form for study characteristics and outcome data which had been piloted on one study included in the review. Four review authors (JB, LV, JM, DR) were involved in both processes so that two review authors independently analysed each included study. We resolved disagreements by consensus or by involving a fifth review author (CS). One review author (JB) entered data into RevMan 2014. We double‐checked that study characteristics and outcome data were entered correctly by comparing the data presented in the systematic review with the study reports. We extracted the following study characteristics:

Methods: date of study, study design, method of randomisation, method of concealment of allocation, blinding, power calculation, duration of follow‐up, number of patients randomised, exclusions post‐randomisation, withdrawals (and reasons).

Participants: N, countries of enrolment, setting/location, mean age/age range, gender (male %), severity of condition, diagnostic criteria, comorbidities, inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Interventions: intervention (including type of formulation), comparison, concomitant medications, excluded medications and duration of treatment.

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes (efficacy and safety) specified and collected, and time points reported. For each outcome: outcome definition, method of measurement and unit of measurement. Results: number of patients analysed (according to type of analysis) and main results.

Notes: source of funding and notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (JB, LV) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third review author (CS). We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains:

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias).

Other bias: source of funding.

We graded each potential source of bias as high, low or unclear and provided a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgment in 'Risk of bias' tables. We took into account the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) regarding 'Risk of bias' assessment of cross‐over studies. We summarised the risk of bias judgements across different studies for each domain. We did not obtain information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with trial authors. We performed an additional handsearch to identify published study protocols to check for selective reporting bias. When considering treatment effects, we took into account the risk of bias for the studies that contributed to that outcome.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted this Cochrane Review according to the published protocol and reported deviations in Differences between protocol and review.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and continuous data as mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs. We used standardised mean differences (SMD) for quality of life meta‐analyses if included data were measured using different tools. We entered data presented as a scale with a consistent direction of effect (with higher scores indicating better quality of life). We did not use skewed data for the quantitative analysis.

Unit of analysis issues

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with either parallel‐group or cross‐over designs. Cross‐over studies were suitable for this Cochrane review because stable angina pectoris is a relatively stable chronic manifestation of disease and the interventions we assessed have only a temporal effect. We took into account the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) regarding statistical analysis of cross‐over studies.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted trial authors to obtain missing numerical outcome data where possible. Where this was not possible, we performed analyses only with the available data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We statistically assessed the presence of heterogeneity among study results by means of the Chi² test with a P value < 0.10 as cut‐off point. We further assessed the degree of heterogeneity by using the I² statistic (McNamara 2015), considering the following thresholds for interpretation: 0% to 40%: not important heterogeneity; 30% to 60%: moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: substantial heterogeneity; and 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity (in which case meta‐analyses were not performed) (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to perform statistical tests for funnel plot asymmetry only for those meta‐analyses which included 10 or more studies (Sterne 2011). Since none of the meta‐analyses performed met this criterion, we used only visual inspection of funnel plots to assess for publication bias.

Data synthesis

We used Review Manager software, version 5.3 (RevMan 2014) for data synthesis and analysis. We undertook meta‐analyses only where this was meaningful, that is, if the treatments, participants and underlying clinical question were sufficiently similar for pooling to make sense. We used fixed‐effect meta‐analyses to calculate effect estimates if there was no statistically significant heterogeneity (Chi² P < 0.10). For results with statistically significant but not considerable heterogeneity (I² ≥ 75%), we used random‐effects meta‐analyses to calculate effect estimates.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out subgroup analyses based on the following variables:

age;

gender;

previous AMI status;

patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); and

number of revascularisation procedures.

Subgroup analyses for these variables could be carried out because we found insufficient data. However, we decided to add another variable: type of stable angina diagnosis (macrovascular versus microvascular). This subgroup analysis was performed for incidence of non‐serious adverse events for ranolazine given as monotherapy compared to placebo, and for quality of life for add‐on ranolazine compared to placebo.

Sensitivity analysis

We undertook sensitivity analyses to explore the effects of decisions we made throughout the review process, including:

Restriction to trials with low risk of bias (those which had at least three domains graded as low risk of bias).

Exchanging the statistical approach for data synthesis (random‐effects versus fixed‐effect models).

Changing the measures of treatment effects for dichotomous (RRs to ORs) and continuous data (SMDs to MDs and vice versa).

Changing the method of dealing with missing data (ignoring versus imputing with replacement values for poor outcomes). This sensitivity analysis was not performed because we decided not to impute any missing data; however, we calculated some data included in the quantitative synthesis from the available information published in reports of the included studies.

Those relevant issues identified during the analyses of studies: we decided to pool the available data irrespective of the duration of follow‐up and perform an additional sensitivity analysis based on this variable (< 6 weeks versus ≥ 6 weeks).

Summary of Findings table and quality of evidence (GRADE)

We created 'Summary of findings' tables for the following outcomes: cardiovascular mortality, non‐cardiovascular mortality, all‐cause mortality, quality of life, AMI incidence, angina episodes frequency and adverse events incidence. We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence as it relates to the studies which contributed data to the meta‐analyses for the prespecified outcomes. We used the methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT 2015). We provided justifications for all decisions to downgrade the quality of evidence in footnotes and included comments to aid readers' understanding of the review where necessary.

Reaching conclusions

We based our conclusions only on findings from the quantitative or narrative synthesis of included studies for this Cochrane review. The Implications for research sections suggests priorities for future research and outlines remaining uncertainties in the area.

Results

Description of studies

See the Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification tables for detailed descriptions.

Results of the search

We identified 515 records through searching electronic databases and 315 additional records from other sources. After removing duplicates, 639 records remained for screening of titles and abstracts. We deemed 611 to be irrelevant and the remaining 28 records were obtained in full‐text for eligibility assessment. We excluded 10 reports. We included 17 RCTs (18 records) in the qualitative analysis; of these, 14 studies (15 reports) were also included in the quantitative synthesis (CARISA 2004; ERICA 2006; MARISA 2004; Mehta 2011; MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; Pelliccia 2012; Pepine 1999; RAN080 2005; RIVER‐PCI 2016; RWISE 2016; Shammas 2015; TERISA 2013; Thadani 1994; Villano 2013) (see Figure 1).

The MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007 trial included patients with non ST‐elevation acute coronary syndrome; a subgroup of those patients had also a history of stable angina, and the results regarding these patients were reported in the sub study included in this review. The RIVER‐PCI 2016 trial considered three sub studies in its protocol, all of which were of interest for this review; however, only the results of two have been published in separate reports included in this review.

Included studies

We included 17 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that enrolled a total of 9975 participants. Two RCTs (MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; RIVER‐PCI 2016) provided data for 61.8% of participants.

Of the 17 RCTs, 11 were parallel‐group and six were cross‐over design studies. Most studies were performed in high‐income regions such as North America, Europe and Australia; five studies included participants from Asia, Russia, Israel, India (CARISA 2004; MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; RIVER‐PCI 2016; Sandhiya 2015; TERISA 2013) and Africa (MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007). All but three studies included mostly female participants; Mehta 2011, RWISE 2016 and Villano 2013 reported percentages of male participants as 0%, 4% and 19.6%, respectively. Most participants' ages ranged from 60 years to 80 years. Although all studies included people with angina, some considered additional inclusion criteria that enabled discrimination between people with macrovascular angina (Babalis 2015; CARISA 2004; ERICA 2006; MARISA 2004; RAN080 2005; Sandhiya 2015; Shammas 2015; TERISA 2013) and microvascular angina (Mehta 2011; RWISE 2016; Tagliamonte 2015; Villano 2013). Notably, three of four studies that included people with microvascular angina were also those that included mostly female participants. Only four studies enrolled participants with comorbidities such as acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007), incomplete revascularisation post‐percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (RIVER‐PCI 2016) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Sandhiya 2015; TERISA 2013). Intervention durations ranged from 1 to 92 weeks.

Ranolazine was used as both extended and immediate release formulations; however, the formulation was not specified in nine studies (Babalis 2015; Mehta 2011; Pelliccia 2012; RIVER‐PCI 2016; Sandhiya 2015; Shammas 2015; Tagliamonte 2015; Thadani 1994; Villano 2013). Ranolazine was administered as add‐on therapy in seven studies. Co‐medications included adrenergic beta antagonists (Shammas 2015), calcium channel blockers (ERICA 2006) or both (Babalis 2015; CARISA 2004; Pepine 1999; TERISA 2013; Villano 2013). However, several other studies (Mehta 2011; MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; Pelliccia 2012; RAN080 2005; RIVER‐PCI 2016; RWISE 2016) permitted concomitant anti‐angina medications to be administered to some participants.

Most studies compared ranolazine only with placebo; other comparators included atenolol (RAN080 2005), ivabradine (Villano 2013) and trimetazidine (Sandhiya 2015).

Seven included studies evaluated mainly parameters related to exercise electrocardiogram (ECG) (Babalis 2015; CARISA 2004; MARISA 2004; MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; Pepine 1999; RAN080 2005; Thadani 1994), which were added (time to 1‐mm ST‐segment depression at peak) to the review outcomes. Three studies reported data relevant only for a secondary safety outcome (incidence of adverse events) (Babalis 2015; MARISA 2004; Pepine 1999). Only one study reported data for the primary outcomes of this review and collected data on the costs of health care (a secondary outcome). However, results are not yet published (RIVER‐PCI 2016).

Most included studies (n = 12) reported commercial sources of funding including: CV Therapeutics (CARISA 2004; ERICA 2006; MARISA 2004; MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; RAN080 2005; RWISE 2016); Syntex Research (Pepine 1999; Thadani 1994); Gilead Sciences (RIVER‐PCI 2016; Shammas 2015; TERISA 2013); and other (Mehta 2011). Two studies reported no external sources of funding (Sandhiya 2015; Pelliccia 2012) and three did not state sources of funding (Babalis 2015; Tagliamonte 2015; Villano 2013).

Excluded studies

We excluded 10 studies after retrieving and assessing full‐text reports. Six studies were excluded because their design did not correspond to a RCT. Four of these studies were economic analyses for which the health economics data provided did not come from studies conducted alongside a RCT (Coleman 2015; Hidalgo‐Vega 2014; Kohn 2014; Lucioni 2009). Another of these studies was a safety study on ranolazine without comparator (ROLE 2007). The remaing study was a one‐group cross‐over trial and it did not state if the treatment order was randomised (Jain 1990). Two studies were excluded because of corresponding to substudies of already included studies (Arnold 2014, Rich 2007). One study was excluded because the duration of the intervention was shorter than the 1‐week period established as a minimum for inclusion (Cocco 1992). Another study was excluded because its population did not match inclusion criteria for participants (Rehberger‐Likozar 2015).

Studies awaiting classification

Four studies await classification (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). Available data were insufficient to determine if these studies met the inclusion criteria for this review. In three studies, population characteristics were not described in sufficient detail to determine if they were restricted to people with stable angina (NCT01304095; Tagarakis 2013; Tian 2012). The fourth study (Wang 2012) did not provide information about randomisation and blinding. The full‐text reports for three studies (Tagarakis 2013; Tian 2012; Wang 2012) could not be obtained.

Ongoing studies

We identified 17 ongoing trials which met the review eligibility criteria (Characteristics of ongoing studies). Of those, 15 studies are parallel‐group designs and two are cross‐over studies (NCT01754259, NCT01495520). Most studies are being performed in high‐income regions, such as North America and Europe, two studies in Asia (India) (CTRI/2014/01/004332; Gupta 2014); and six did not state locations (Calcagno 2014; Calcagno 2015; NCT02147067; NCT02252406; NCT02423265; Šebeštjen 2014). All but one study includes a mixed population regarding gender; Šebeštjen 2014 includes only males. Seven studies restricted the population to people with macrovascular angina (EUCTR 2011‐001278‐24; EUCTR 2012‐001584‐77; NCT01495520; NCT01754259; NCT01948310; NCT02252406; NCT02423265) and two restricted participants to people with microvascular angina (NCT02052011; NCT02147067). Some studies consider comorbidities or important antecedents such as PCI‐stent implantation (Calcagno 2014; Calcagno 2015; NCT02423265), sustained STEMI (CTRI/2014/01/004332), diabetes mellitus (Gupta 2014; NCT01754259), metabolic syndrome (NCT02252406) and other cardiac conditions (NCT01558830). Intervention durations range from 4 weeks to 12 months.

The evaluation of ranolazine as add‐on therapy is explicitly stated in two studies (Gupta 2014; NCT02423265); the remainder provide insufficient information to determine how ranolazine is being administered. Ranolazine doses range from 375 mg twice daily to 1000 mg twice daily. The comparator for most studies is placebo or no treatment, with only three studies comparing ranolazine with other second‐line anti‐angina treatments such as ivabradine (Calcagno 2015) and trimetazidine (CTRI/2014/01/004332; Šebeštjen 2014).

Five studies assess quality of life (NCT02052011; NCT02147067; NCT02147834; NCT02265796; NCT02423265); two assess frequency of angina episodes (EUCTR 2011‐001278‐24; Gupta 2014); two assess need for revascularisation procedure (NCT02147834; NCT02265796); five assess exercise ECG parameters (Calcagno 2014; Calcagno 2015; EUCTR 2011‐001278‐24; NCT02147067; NCT02423265). Eight studies do not assess any of the effectiveness outcomes of this review (CTRI/2014/01/004332; EUCTR 2012‐001584‐77; NCT01495520; NCT01558830; NCT01754259; NCT01948310; NCT02252406; Šebeštjen 2014). Eight studies state commercial sources of funding (at least partially) from pharmaceutical companies such as Gilead Sciences (NCT01558830; NCT01948310; NCT02052011; NCT02147067; NCT02147834; NCT02265796) and Menarini International Operations (EUCTR 2011‐001278‐24; EUCTR 2012‐001584‐77).

Risk of bias in included studies

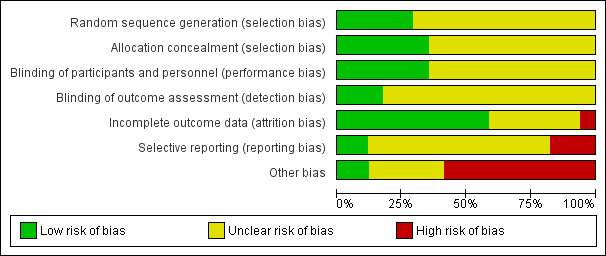

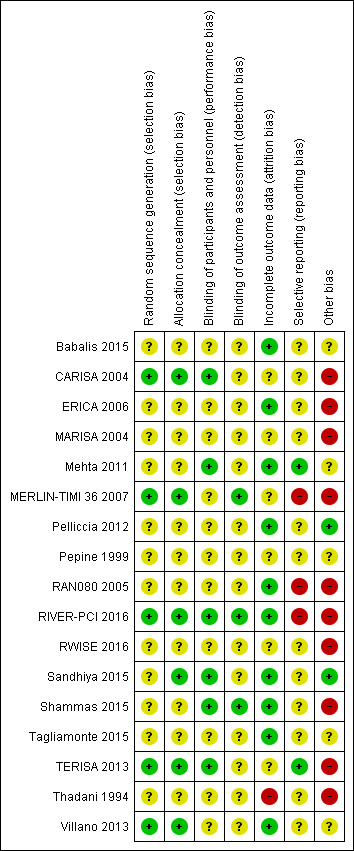

Risk of bias is illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Also see Characteristics of included studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Other bias criteria: we considered the source of funding in this section, we scored high risk of bias if the source of funding was solely from private organisations, unclear risk of bias if it was mixed (private and public) and low risk of bias if it was solely not external or from public organisations.

Allocation

All included studies randomly assigned participants to treatment groups using either computer‐generated sequences (CARISA 2004; MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; RIVER‐PCI 2016; TERISA 2013; Villano 2013) or other methods that were described with insufficient detail to enable assessment (Babalis 2015; ERICA 2006; MARISA 2004; Mehta 2011; Pelliccia 2012; Pepine 1999; RAN080 2005; RWISE 2016; Sandhiya 2015; Shammas 2015; Tagliamonte 2015; Thadani 1994).

Adequate concealment of allocation methods were described in four studies (CARISA 2004; Sandhiya 2015; TERISA 2013; Villano 2013). Two additional studies (MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; RIVER‐PCI 2016) did not describe in detail their method for allocation concealment, but it was considered to be adequate given the use of a centralised randomization system. One study stated that investigators had been blinded to treatment allocation (Shammas 2015); this was not considered to be sufficiently detailed to inform assessment.

Blinding

Most studies reported using a double‐blind design for the treatment phase. However, only one study explicitly indicated who were blinded (Shammas 2015). This was established from information provided in five other studies (CARISA 2004; Mehta 2011; RIVER‐PCI 2016; Sandhiya 2015; TERISA 2013). Blinding was not stated in two study reports (Babalis 2015; Villano 2013).

Blinding of outcome assessment was reported in seven studies (CARISA 2004; MARISA 2004; Mehta 2011; MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; RIVER‐PCI 2016; Shammas 2015; Villano 2013). However, for outcomes considered in this review, only three studies reported blinding measures for outcome assessment (MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; RIVER‐PCI 2016; Shammas 2015).

Incomplete outcome data

Six studies did not report any withdrawals or exclusions of participants, but of these, only three explicitly stated that no participants withdrew or were excluded (Babalis 2015; Mehta 2011; Tagliamonte 2015). Five studies did not describe reasons for exclusions or withdrawal in sufficient detail to inform assessment (CARISA 2004; MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; Pepine 1999; RWISE 2016; TERISA 2013). One study did not report the allocated groups of excluded or withdrawn participants (MARISA 2004). The five studies in which numbers, reasons and allocated group of participants who withdrew or were excluded were reported, inconsistencies in data were identified for one or two participants in three studies (ERICA 2006; RAN080 2005; Shammas 2015). The number of exclusions and withdrawals approached 10% of the total study population in one study (Thadani 1994).

The type of analysis was not stated in eight studies (Babalis 2015; ERICA 2006; RWISE 2016; Sandhiya 2015; Shammas 2015; Tagliamonte 2015; TERISA 2013; Villano 2013). Seven studies reported performing intention‐to‐treat analyses (CARISA 2004; MARISA 2004, Mehta 2011; MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; Pelliccia 2012; RAN080 2005; RIVER‐PCI 2016); two studies reported performing intention‐to‐treat and per‐protocol analyses (Pepine 1999; Thadani 1994). Pepine 1999 and Thadani 1994 reported results from intention‐to‐treat analyses, and stated that no significant differences were found among intention‐to‐treat and per‐protocol analyses.

Selective reporting

We assessed selective reporting by cross‐checking study outcomes with published protocols. We found protocols for only five included studies (Mehta 2011; MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; RIVER‐PCI 2016; RWISE 2016; TERISA 2013). The protocol for the MERLIN‐TIMI 36 trial (Morrow 2006) did not consider the sub study (MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007) we included in this review (post‐hoc analyses), and thus was considered to be at high risk of bias. Of note, the report of this sub study met our pre‐specified inclusion criteria, and it takes part of only one of our analyses (Analysis 1.2), whose result do not change if the MERLIN TIMI 36 sub study is not considered.

1.2. Analysis.

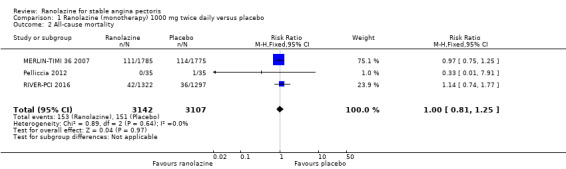

Comparison 1 Ranolazine (monotherapy) 1000 mg twice daily versus placebo, Outcome 2 All‐cause mortality.

We used information presented in studies' Methods sections as a proxy for protocols. We found that three studies did not report data for some outcomes (Babalis 2015; MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; RIVER‐PCI 2016) and four studies reported data for additional outcomes (CARISA 2004; MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; RAN080 2005; RIVER‐PCI 2016). Selective reporting affected outcomes considered in this review in three studies (CARISA 2004; RAN080 2005; RIVER‐PCI 2016).

Other potential sources of bias

We considered the source of funding and conflicts of interest as potential sources of bias. Most studies reported funding from commercial pharmaceutical companies. Sources of funding were reported to be partially supported by commercial pharmaceutical companies in three studies, no conflicts of interest were reported in two of these (Mehta 2011, Pepine 1999) and conflicts of interest were reported for some of the authors in the other one (RWISE 2016). Three studies (Babalis 2015; Tagliamonte 2015; Villano 2013) reported neither funding source nor authors' conflicts of interest. Two studies reported no external source of funding and absence of conflicts of interest (Pelliccia 2012; Sandhiya 2015).

Effects of interventions

Table 1 presents ranolazine compared to placebo (add‐on therapy) and Table 2 presents ranolazine compared to placebo (monotherapy).

Primary outcomes

Cardiovascular mortality

Only RIVER‐PCI 2016 reported data on cardiovascular mortality for ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily administered as monotherapy compared to placebo. We observed uncertain effect on cardiovascular mortality from the 20/1287 cardiovascular deaths in the placebo group and 21/1317 cardiovascular deaths in the ranolazine group (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.88; low quality evidence) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ranolazine (monotherapy) 1000 mg twice daily versus placebo, Outcome 1 Cardiovascular mortality.

Non‐cardiovascular mortality

None of the included studies reported non‐cardiovascular mortality.

Secondary outcomes

Effectiveness

The main results are summarised in analyses for ranolazine as monotherapy compared to placebo (Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.4; Analysis 1.5; Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2) and as add‐on therapy compared to placebo (Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.4; Analysis 3.5; Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ranolazine (monotherapy) 1000 mg twice daily versus placebo, Outcome 3 Quality of life.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ranolazine (monotherapy) 1000 mg twice daily versus placebo, Outcome 4 AMI incidence.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ranolazine (monotherapy) 1000 mg twice daily versus placebo, Outcome 5 Need for revascularisation procedure.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Ranolazine (monotherapy) any dose versus placebo, Outcome 1 AMI incidence.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Ranolazine (monotherapy) any dose versus placebo, Outcome 2 Angina episodes frequency.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Ranolazine (add‐on therapy) 1000 mg twice daily versus placebo, Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Ranolazine (add‐on therapy) 1000 mg twice daily versus placebo, Outcome 2 Quality of life.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Ranolazine (add‐on therapy) 1000 mg twice daily versus placebo, Outcome 3 AMI incidence (fatal).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Ranolazine (add‐on therapy) 1000 mg twice daily versus placebo, Outcome 4 AMI incidence (non‐fatal).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Ranolazine (add‐on therapy) 1000 mg twice daily versus placebo, Outcome 5 Angina episodes frequency.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ranolazine (add‐on therapy) any dose versus placebo, Outcome 1 Quality of life.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ranolazine (add‐on therapy) any dose versus placebo, Outcome 2 Time to 1‐mm ST‐segment depression.

Data were reported for ranolazine as monotherapy compared to placebo for quality of life (Tagliamonte 2015) and frequency of angina episodes (RAN080 2005; Thadani 1994). These data could not be pooled in a meta‐analysis due to incompleteness.

Ranolazine was compared to other first‐ (RAN080 2005, atenolol 100 mg once daily) and second‐line anti‐anginals (Sandhiya 2015; Villano 2013; trimetazidine 35 mg twice daily and ivabradine 5 mg twice daily respectively), either as monotherapy (RAN080 2005; Sandhiya 2015) or add‐on therapy (Villano 2013). Data could not be meta‐analysed because, for any outcome, only one trial provided data. Study authors were contacted to obtain missing data. Additional data were provided by Dr Noel Bairey Merz (Mehta 2011) and Dr Nicolas W Shammas (Shammas 2015) and included in the quantitative synthesis.

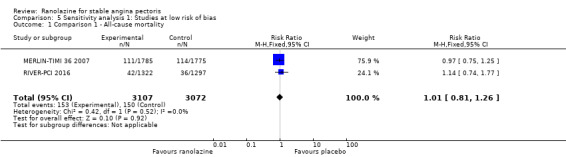

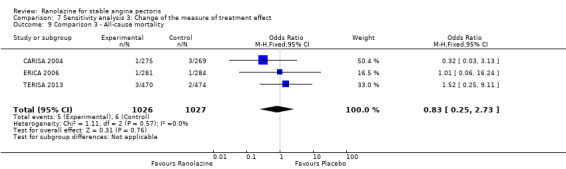

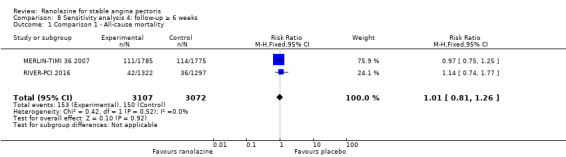

All‐cause mortality

Three studies reported all‐cause mortality for ranolazine 1000 mg monotherapy administered twice daily compared to placebo (MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007; Pelliccia 2012; RIVER‐PCI 2016). Low quality evidence showed that intervention and placebo group participants were at similar risk of death from all causes (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.25; 3 studies, 6249 participants; Analysis 1.2). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.64, I² = 0%).

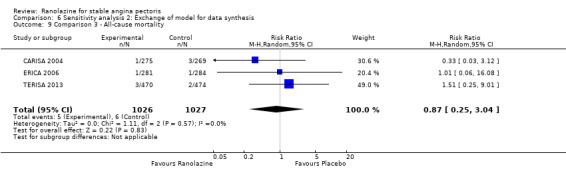

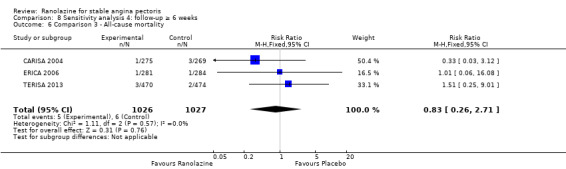

Three studies reported all‐cause mortality for ranolazine 1000 mg as add‐on therapy administered twice daily (co‐medications: adrenergic beta antagonists and calcium channel blockers) compared to placebo (CARISA 2004; ERICA 2006; TERISA 2013). Low quality evidence showed that intervention and placebo group participants were at similar risk of death from all causes (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.26 to 2.71; 3 studies, 2053 participants; Analysis 3.1). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.57, I² = 0%).

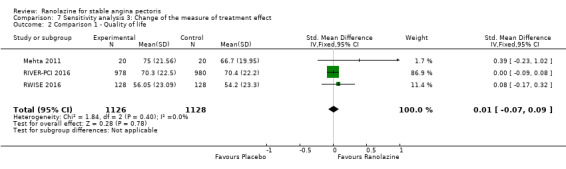

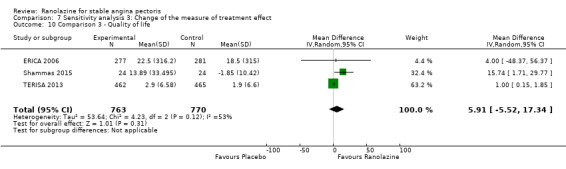

Quality of life

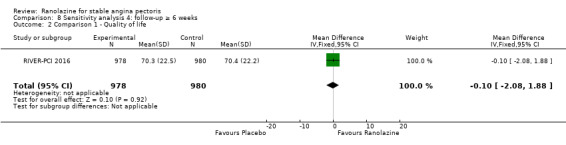

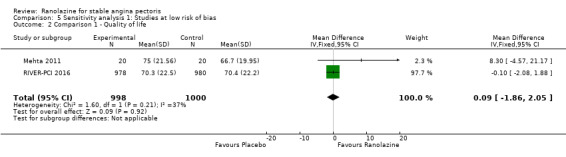

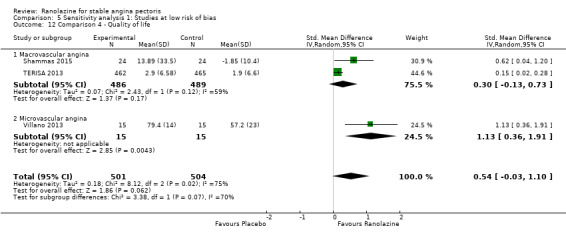

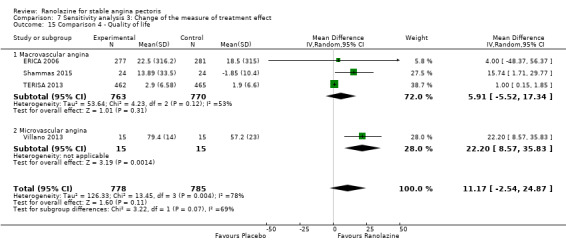

Three studies evaluated quality of life for ranolazine 1000 mg monotherapy administered twice daily compared to placebo (Mehta 2011; RIVER‐PCI 2016, RWISE 2016). Moderate quality evidence showed that quality of life did not differ between intervention and placebo group participants (MD 0.28, 95% CI ‐1.57 to 2.13; 3 studies, 2254 participants; Analysis 1.3). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.38, I² = 0%). Data were assessed using the quality of life dimension of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) in the three trials. The score for this dimension ranged between 0 and 100, with a higher score indicating a better quality of life.

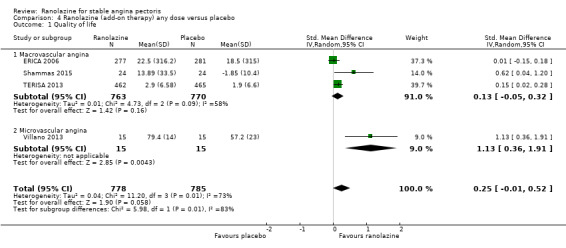

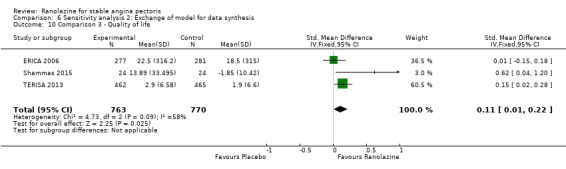

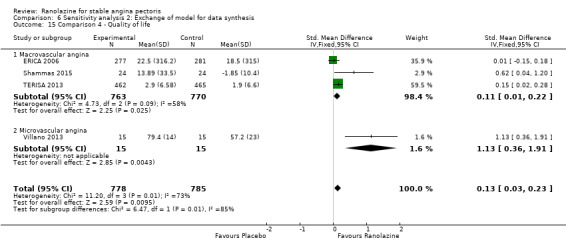

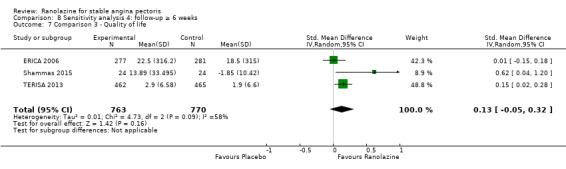

Three studies evaluated quality of life for ranolazine 1000 mg as add‐on therapy administered twice daily (co‐medications: adrenergic beta antagonists and calcium channel blockers) compared to placebo (ERICA 2006; Shammas 2015; TERISA 2013). Moderate quality evidence showed that quality of life did not differ between intervention and control group participants (SMD 0.13, 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.32; 3 studies, 1533 participants; Analysis 3.2). Since there was statistically significant, but not considerable, heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.09, I² = 58%) we used a random‐effects model to calculate the pooled estimate. We observed that studies differed in risk of selection and detection bias and population size (fewer than 30 participants versus more than 400 participants), which may explain heterogeneity. Pooled data were reported for quality of life assessed using different scales: the angina frequency and quality of life dimensions of the SAQ, and the physical component of SF‐36. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better quality of life.

One additional study evaluated quality of life for ranolazine given as add‐on therapy (to adrenergic beta antagonists and calcium channel blockers) compared to placebo (Villano 2013), making a total of four trials for the ranolazine any dose (375mg twice daily and 1000mg twice daily) comparison. Moderate quality evidence showed that quality of life did not differ between intervention and placebo group participants (ranolazine any dose, SMD 0.25, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.52; 4 studies, 1563 participants, Analysis 4.1). Since there was statistically significant, but not considerable, heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.01, I² = 73%) we used a random‐effects model to calculate the pooled estimate. We observed that trials in this analysis differed in risk of selection and detection bias and population size (fewer than 40 versus more than 400) and type of stable angina diagnosis (macrovascular angina versus microvascular angina), which may explain heterogeneity.

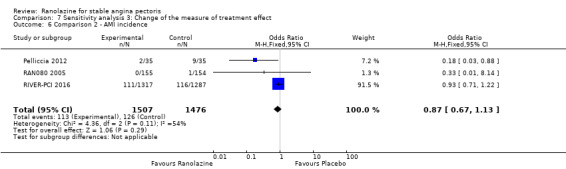

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) incidence

Fatal AMI incidence

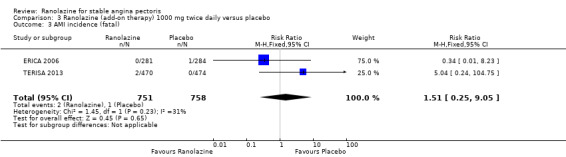

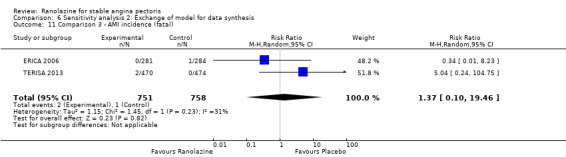

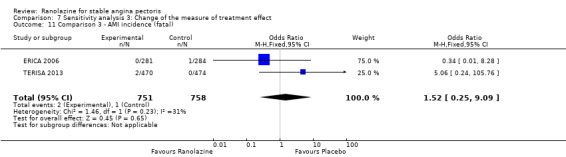

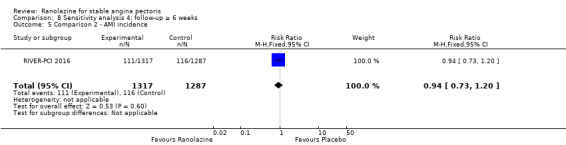

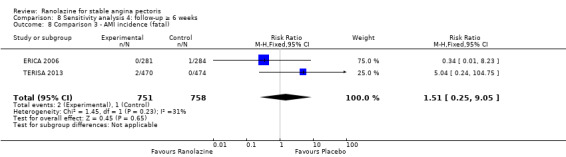

We found no data on fatal AMI for ranolazine given as monotherapy compared to placebo. Two studies reported data on fatal AMI events for ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily given as add‐on therapy compared to placebo (ERICA 2006; TERISA 2013). Low quality evidence showed uncertain effect for the risk of fatal AMI between intervention and placebo group participants (RR 1.51, 95% CI 0.25 to 9.05; 2 studies, 1509 participants; Analysis 3.3). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.23, I² = 31%).

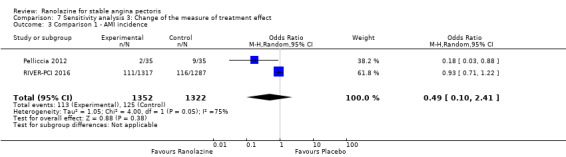

Non‐fatal AMI incidence

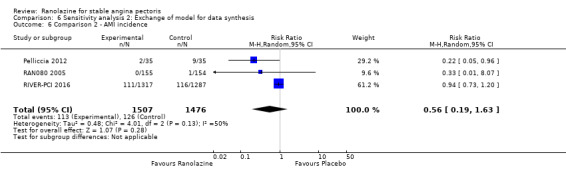

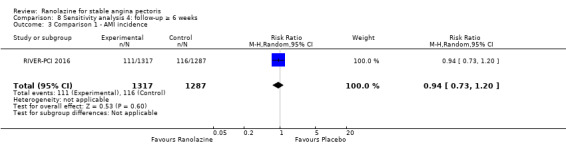

Two studies reported non‐fatal AMI incidence for ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily given as monotherapy compared to placebo (Pelliccia 2012; RIVER‐PCI 2016). Very low quality evidence showed that participants in both intervention and control groups were at similar risk of non‐fatal AMI (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.14 to 2.15; 2 studies, 2674 participants; Analysis 1.4). Since there was statistically significant, but not considerable, heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.06, I² = 73%) we used a random‐effects model to calculate the pooled estimate. We observed that studies in this analysis differed in risk of performance and detection bias and duration of follow‐up (30 days versus 643 days), which may explain heterogeneity.

One study reported non‐fatal AMI incidence for ranolazine given as monotherapy compared to placebo (RAN080 2005), making a total of three studies for ranolazine any dose (400 mg three times daily and 1000 mg twice daily) comparison. Low quality evidence showed that intervention and control group participants were at a similar risk of non‐fatal AMI (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.12; 2983 participants, Analysis 2.1). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.13, I² = 50%).

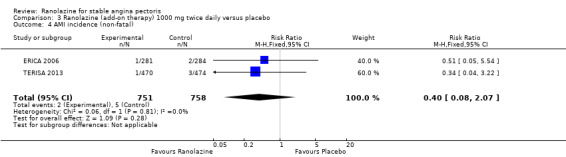

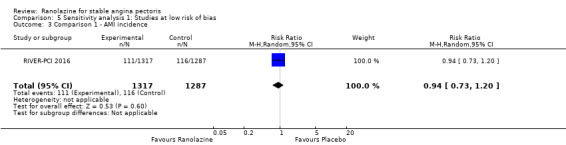

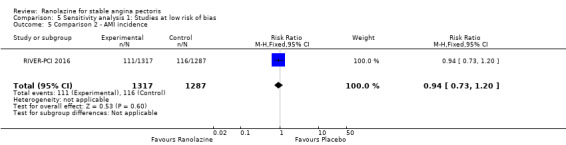

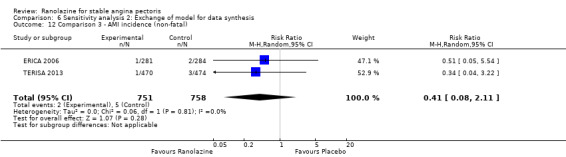

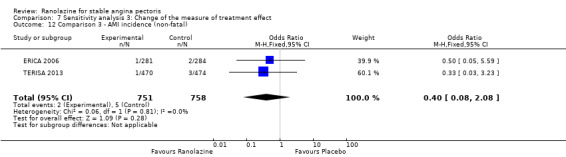

Two other studies reported non‐fatal AMI incidence for ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily given as add‐on therapy compared to placebo (ERICA 2006; TERISA 2013). Low quality evidence showed that participants in both groups were at a similar risk of suffering a non‐fatal AMI (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.08 to 2.07, 1509 participants, Analysis 3.4). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.81, I² = 0%).

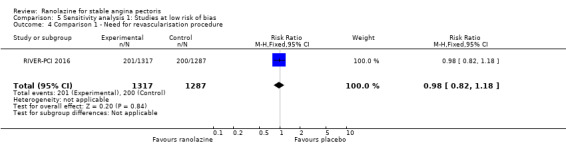

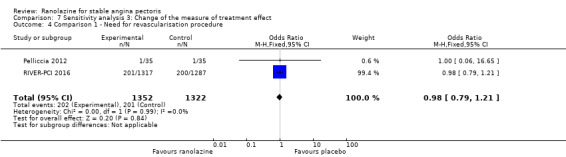

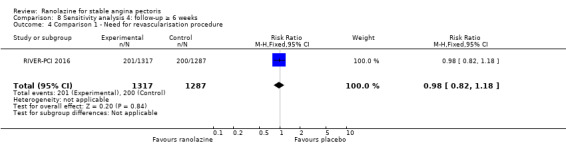

Need for revascularisation procedure

Two studies reported incidence of revascularisation procedures for ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily given as monotherapy compared to placebo (Pelliccia 2012; RIVER‐PCI 2016). Moderate quality evidence showed that ranolazine has no effect on the risk of undergoing a revascularisation procedure (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.18, 2674 participants, Analysis 1.5). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.99, I² = 0%).

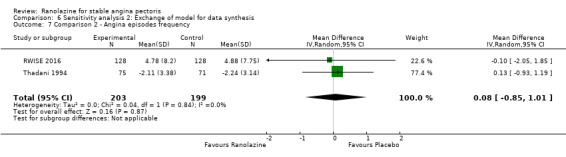

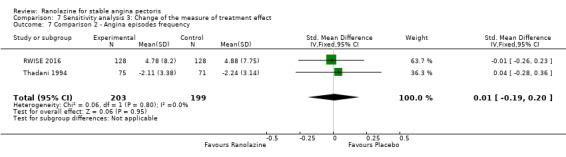

Angina episodes frequency

Two studies evaluated angina episodes frequency for ranolazine any dose (120 mg 3 times daily and 1000 mg twice daily) given as monotherapy compared to placebo (RWISE 2016; Thadani 1994). Low quality evidence showed that the average number of angina episodes per week did not differ in the participants in both groups (MD 0.08, 95% CI ‐0.85 to 1.01, 402 participants, Analysis 2.2). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.84, I² = 0%).

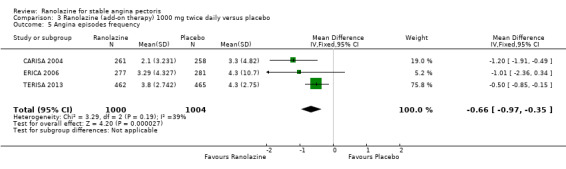

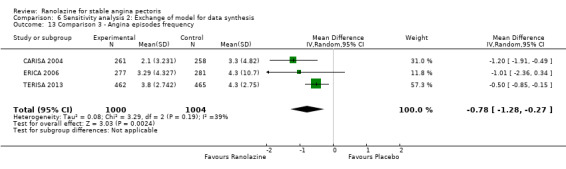

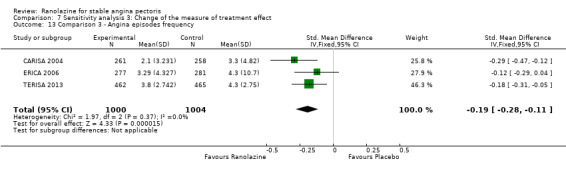

Three studies evaluated angina episodes frequency for ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily given as add‐on therapy (to adrenergic beta antagonists and calcium channel blockers) compared to placebo (CARISA 2004; ERICA 2006; TERISA 2013). Moderate quality evidence showed that the average number of angina episodes per week was lower in the participants who received ranolazine (MD ‐0.66, 95% CI ‐0.97 to ‐0.35, 2004 participants, Analysis 3.5). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.19, I² = 39%).

Costs of healthcare

None of the included trials reported data on costs and resource use of the management of stable angina participants. We found that only one trial (RIVER‐PCI 2016) reported a planned health economics sub‐study (Weisz 2013), but results have not yet been published.

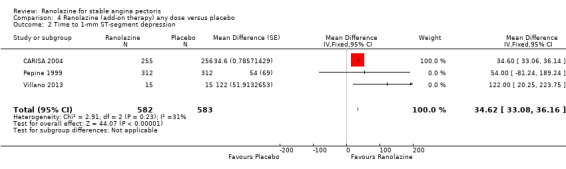

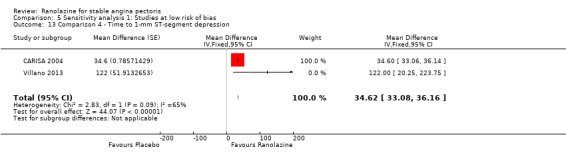

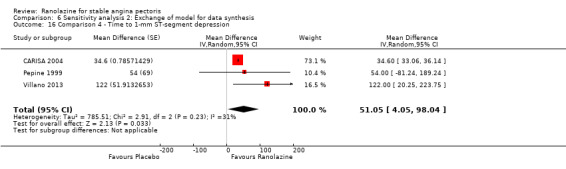

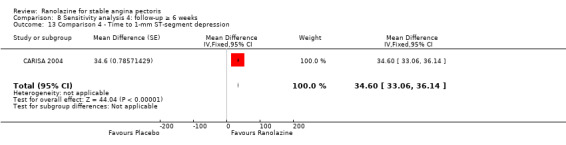

Time to 1‐mm ST‐segment depression

Three studies evaluated time to 1‐mm ST‐segment depression in exercise ECG at peak for ranolazine any dose (375 mg twice daily, 400 mg three times daily and 1000 mg twice daily) given as add‐on therapy compared to placebo (CARISA 2004; Pepine 1999; Villano 2013). Moderate quality evidence showed that the average time to 1‐mm ST‐segment depression in seconds was higher in participants who received ranolazine (MD 34.62, 95% CI 33.08 to 36.16, 1198 participants, Analysis 4.2). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.23, I² = 31%).

Data were also available for ranolazine given as monotherapy compared to placebo; however, pooled estimates showed substantial heterogeneity (I² = 90% to 99%) which precluded us from including those results in the quantitative synthesis. We observed that studies included in this analysis differed notably in design (parallel‐group versus cross‐over), duration of follow‐up (< 1 month versus ˜12 months), number of participants (< 200 versus > 3000), and baseline 1‐mm ST‐segment depression (< 260 s versus > 430 s).

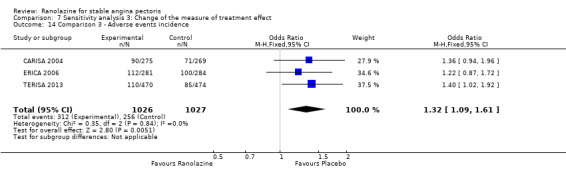

Safety

The main results are summarised in forest plots for ranolazine given as monotherapy compared to placebo (Analysis 1.6, Analysis 2.3) and as add‐on therapy compared to placebo (Analysis 3.6). Data from other trials are also reported for ranolazine given as monotherapy compared to placebo for adverse events incidence (Pepine 1999; Thadani 1994) which could not be pooled for meta‐analysis due to incompleteness. Similarly, data for ranolazine given as add‐on therapy compared to placebo for adverse events incidence (Shammas 2015, Villano 2013) could not be pooled for meta‐analysis due to incompleteness. Missing data have been requested from the study contact authors. Although no quantitative analysis could be performed for specific events, it was observed that the most frequently reported events were dizziness, nausea and constipation. 'Other' which included peripheral oedema, headache, asthenia, palpitations, dyspepsia, weakness and postural hypotension, was the most commonly re[ported category.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ranolazine (monotherapy) 1000 mg twice daily versus placebo, Outcome 6 Adverse events incidence.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Ranolazine (monotherapy) any dose versus placebo, Outcome 3 Adverse events incidence.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Ranolazine (add‐on therapy) 1000 mg twice daily versus placebo, Outcome 6 Adverse events incidence.

Adverse events incidence

Serious adverse events

We found insufficient data on serious adverse events to perform quantitative synthesis. Although the included studies reported types of serious adverse events inconsistently, we summarised data into three categories:

Cerebrovascular events: Two studies (RIVER‐PCI 2016; RWISE 2016) reported data for ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily given as monotherapy compared to placebo. RIVER‐PCI 2016 reported 22/1317 and 20/1287 events of stroke and 13/1317 and 3/1287 events of transitory ischaemic attack among participants who received ranolazine and placebo respectively. RWISE 2016 reported 2/128 and 0/128 events of pre‐syncope and 1/128 and 0/128 events of syncope among participants who received ranolazine and placebo respectively. Three other studies (ERICA 2006; Shammas 2015; TERISA 2013) reported data for ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily given as add‐on therapy compared to placebo. ERICA 2006 reported that there were no events of stroke in any treatment groups. Shammas 2015 reported 1/24 and 0/24 events of stroke among participants given ranolazine and placebo respectively. TERISA 2013 reported 1/470 and 4/474 events of stroke among participants given ranolazine and placebo respectively. Pooling data resulted in RR of 0.56 (95% CI 0.12 to 2.60, 3 studies, 1557 participants, Chi² P = 0.21, I² = 38%).

Heart failure: Only RIVER‐PCI 2016 reported data for ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily given as monotherapy compared to placebo. RIVER‐PCI 2016 reported heart failure events requiring hospitalisation (further classified as ischaemia and non‐ischemia‐related) in 38/1317 and 25/1287 of participants given ranolazine and placebo respectively.

Arrhythmias: None of the included studies reported arrhythmia‐related hospitalisations. However two trials reported symptomatic documented arrhythmias for ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily given as monotherapy (MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007) and as add‐on therapy (ERICA 2006) compared to placebo. MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007 (stable angina patients subgroup) reported 52/1785 and 52/1775 symptomatic documented arrhythmias among participants given ranolazine and placebo respectively. ERICA 2006 reported 8/281 and 10/284 arrhythmias (ventricular extrasystoles, sinus bradycardias, sinus tachycardias and atrioventricular blockages) among participants given ranolazine and placebo respectively. Of note, Shammas 2015 and MERLIN‐TIMI 36 2007 conducted separate recordings of arrhythmias over short periods of the total study duration, which we considered did not fit the purposes of this review.

Some other events were labelled as major or serious adverse events in some trials (RIVER‐PCI 2016; TERISA 2013) but these were not reported in sufficient detail to determine their suitability to meet the definition for this outcome.

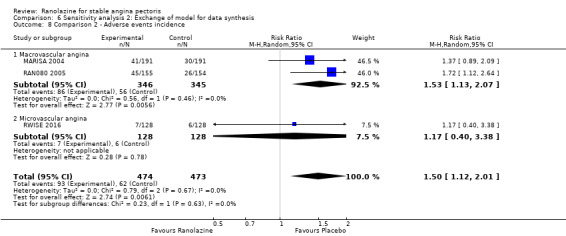

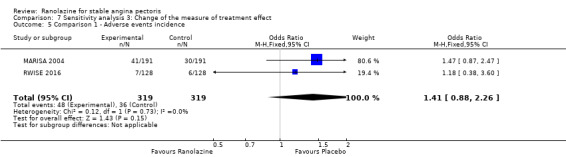

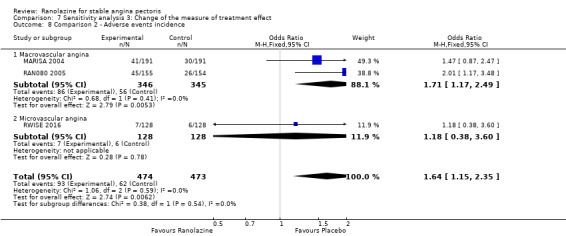

Non‐serious adverse events

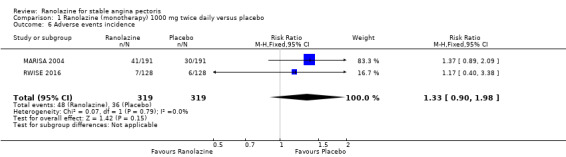

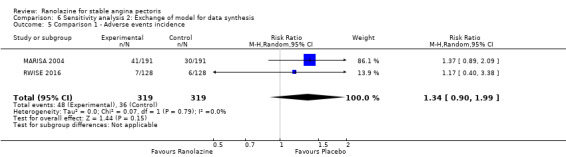

Two studies reported the incidence of non‐serious adverse events for ranolazine 1000 mg twice daily given as monotherapy compared to placebo (MARISA 2004; RWISE 2016). Very low quality evidence showed that participants in both groups were at similar risk of presenting non‐serious adverse events (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.98, 638 participants, Analysis 1.6). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.79, I² = 0%).

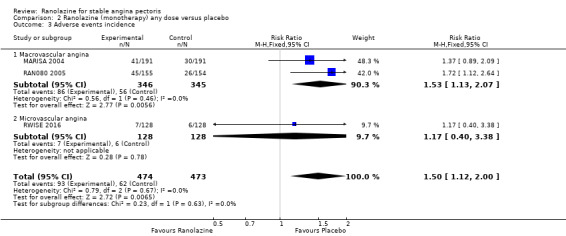

RAN080 2005 reported non‐fatal AMI incidence for ranolazine given as monotherapy compared to placebo. Very low quality evidence showed that the participants treated with ranolazine were at a higher risk of presenting non‐serious adverse events (RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.12 to 2.00, 947 participants, Analysis 2.3). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² P = 0.67, I² = 0%).