Key Points

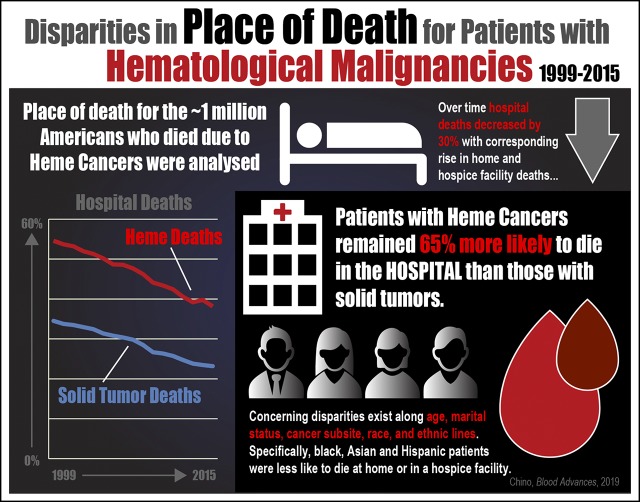

Despite overall improvements, patients with HMs in the United States remain more likely to die in the hospital than at home.

Concerning place of death disparities exist along age, marital status, cancer subsite, race, and ethnic lines.

Abstract

Patients with hematologic malignancies (HMs) often receive aggressive end-of-life care and less frequently use hospice. Comprehensive longitudinal reporting on place of death, a key quality indicator, is lacking. Deidentified death certificate data were obtained via the National Center for Health Statistics for all HM deaths from 1999 to 2015. Multivariate regression analysis (MVA) was used to test for disparities in place of death associated with sociodemographic variables. During the study period, there were 951 435 HM deaths. Hospital deaths decreased from 54.6% in 1999 to 38.2% in 2015, whereas home (25.9% to 32.7%) and hospice facility deaths (0% to 12.1%) increased (all P < .001). On MVA of all cancers, HM patients had the lowest odds of home or hospice facility death (odds ratio [OR], 0.55; 95% confidence interval, 0.54-0.55). Older age (40-64 years: OR, 1.34; ≥65 years: OR, 1.89), being married (OR, 1.62), and having myeloma (OR, 1.34) were associated with home or hospice facility death, whereas being black or African American (OR, 0.68), Asian (OR, 0.58), or Hispanic (OR, 0.84) or having chronic leukemia (OR, 0.83) had decreased odds of dying at home or hospice (all P < .001). In conclusion, despite hospital deaths decreasing over time, patients with HMs remained more likely to die in the hospital than at home.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

More than 50 000 people die annually from hematological malignancies (HMs) in the United States.1 Surveys suggest that only 1% of patients with cancer prefer an in-hospital death2; most want to die at home.3 However, patients with HMs more frequently receive aggressive end-of-life care,4 and home hospice is seldom used.5 They are up to 4 times more likely to die in the hospital than those with solid tumors6 and, if referred to hospice, are more often enrolled in the last 24 hours of life.7

However, more comprehensive modern evaluation of place of death in the United States is limited, because prior research was based on Medicare data8 (therefore, only patients age ≥65 years) or institutional reporting.9 We therefore sought to evaluate changes in place of death for the HM population over time, using a more inclusive data set, and to describe any associated health care disparities.

Methods

Deidentified death certificate data were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics. The National Center for Health Statistics is part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and provides national statistical information to help guide policies to improve health in the United States. We included all deaths resulting from HMs from 1999 to 2015. Place and year of death were documented along with sociodemographic information including age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, and education. HM deaths were compared with those resulting from solid tumors and then with one another based on subtype (acute leukemia, chronic leukemia, aggressive lymphoma, nonaggressive lymphoma, myeloma).

Using data from all years with full place-of-death reporting (2003-2015), multivariate logistic regression was used to test for disparities in place of death. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 21; Armonk, NY). All comparisons were 2 tailed. The Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board provided a waiver (Pro00045337) for this study.

Results

There were 951 435 deaths resulting from HMs in the study period. A majority of those who died were male (54.9%), white (88.0%), and non-Hispanic (93.9%); 9.6% were black or African American, 2.1% were Asian, and 0.4% were American Indian. Most were age ≥65 years at time of death (73.9%), with median age of 72 years (interquartile range, 63-81 years). Acute leukemia caused the most deaths (21.7%), followed by myeloma (20.0%) and chronic leukemia (10.5%).

Between 1999 and 2015, hospital (54.6% to 38.2%) and nursing facility deaths (13.1% to 11.9%) both decreased, whereas home (25.9% to 32.7%) and hospice facility deaths (0% to 12.1%) increased (all P < .001). Comparing states with the highest and lowest rates, New York had the highest rate of hospital death (61.6%), almost twice the lowest rate in Utah (32.5%). Utah had the highest home death rate (50.0%), almost 3 times the rate in South Dakota (17.5%). Florida had the highest hospice facility death rate (20.2%); it was >20 times the lowest rate in Utah (≤0.2%). Eleven states (Maryland, Idaho, Colorado, Hawaii, Alaska, Massachusetts, Virginia, North Dakota, West Virginia, Utah, Alabama) had aggregate hospice facility utilization of <2% since 2003, the first available year for this data element in the data set.

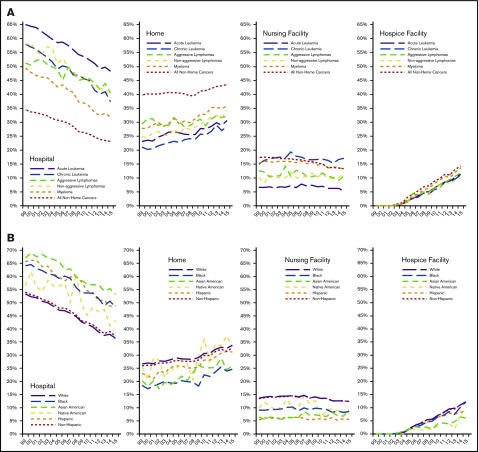

There was also significant variation in place of death by cancer subtype (Figure 1A) and race (Figure 1B). There was an overall downtrend in hospital death for each category. Patients with acute leukemia and Asian race had the highest rates of hospital death. Black or African American patients and those with chronic leukemia were the least likely to die at home. Compared with solid tumor deaths, HM deaths were more likely to occur in the hospital and less likely to occur at home. By 2015, patients with HMs were still 65% more likely to die in the hospital (HMs, 38.2% vs non-HMs, 23.2%) and 25% less likely to die at home (32.7% vs 43.6%; both P < .001).

Figure 1.

Trends in place of death resulting from HMs (1999-2015). Location by primary site (A) and by race and ethnicity (B).

Place of death either at home or in a hospice facility was examined; all assessed categories were associated on univariate analysis (P < .05) and included in the final model. On multivariate analysis of all cancers, HM diagnosis had the strongest negative association with home/hospice facility death (odds ratio [OR], 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-.055; Table 1). On multivariate analysis limited to HMs, older age (age 40-64 years: OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.28-1.39; age ≥65 years: OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.81-1.97), being married (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.57-1.66), and having myeloma (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.31-1.36) were associated with home/hospice facility death. Black or African American (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.66-0.70) and Asian patients (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.55-0.60), those of Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.82-0.86), and those with a diagnosis of chronic leukemia (OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.81-0.85) had decreased odds of dying at home or hospice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate and multivariate analysis–modeled results: death resulting from HMs at home or in hospice facility (vs death in another location)

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| All cancers (HMs and solid tumors) | ||||

| Year of death (continuous variable) | 1.058 (1.058-1.058) | <.001 | 1.047 (1.046-1.047) | <.001 |

| Age, y | ||||

| Age (continuous variable) | 0.997 (0.0997-0.998) | <.001 | — | <.001 |

| 0-39 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| 40-64 | 1.366 (1.351-1.381) | <.001 | 1.095 (1.077-1.112) | <.001 |

| ≥65 | 1.295 (1.281-1.309) | <.001 | 1.050 (1.034-1.067) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female (reference) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Male | 1.030 (1.027-1.033) | <.001 | 0.930 (0.926-0.934) | <.001 |

| Marital status* | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| Single (reference) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Married | 2.027 (2.058-2.082) | <.001 | 1.997 (1.982-2.013) | <.001 |

| Divorced/separated | 1.361 (1.352-1.370) | <.001 | 1.284 (1.273-1.296) | <.001 |

| Widowed | 1.411 (1.403-1.419) | <.001 | 1.388 (1.376-1.400) | <.001 |

| Education level† | <.001 | |||

| Some high school or less (reference) | 1.000 | <.001 | 1.000 | |

| High school graduate (≥4 y) | 1.047 (1.042-1.052) | <.001 | 0.976 (0.970-0.981) | <.001 |

| Some college/associates degree | 1.174 (1.167-1.181) | <.001 | 1.068 (1.061-1.076) | <.001 |

| College graduate (≥4 y) | 1.163 (1.155-1.171) | <.001 | 1.055 (1.047-1.063) | <.001 |

| Advanced degree | 1.206 (1.196-1.216) | <.001 | 1.092 (1.082-1.102) | <.001 |

| Race | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| White (reference) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Black or African American | 0.669 (0.666-0.672) | <.001 | 0.693 (0.731-0.757) | <.001 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0.776 (0.768-0.783) | <.001 | 0.636 (0.629-0.644) | <.001 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.888 (0.869-0.906) | <.001 | 0.859 (0.836-0.883) | <.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic (reference) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Hispanic | 1.089 (1.082-1.096) | <.001 | 0.954 (0.946-0.962) | <.001 |

| Primary cancer diagnosis | ||||

| Solid tumor (reference) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HM | 0.570 (0.567-0.573) | <.001 | 0.547 (0.543-0.551) | <.001 |

| HMs only | ||||

| Year of death (continuous variable) | 1.058 (1.058-1.058) | <.001 | 1.053 (1.051-1.055) | <.001 |

| Age, y | ||||

| Age (continuous variable) | 0.997 (0.0997-0.998) | <.001 | — | <.001 |

| 0-39 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| 40-64 | 1.366 (1.351-1.381) | <.001 | 1.335 (1.281-1.390) | <.001 |

| ≥65 | 1.295 (1.281-1.309) | <.001 | 1.888 (1.814-1.965) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female (reference) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Male | 1.030 (1.027-1.033) | <.001 | 0.990 (0.977-1.003) | .133 |

| Marital status* | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| Single (reference) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Married | 2.027 (2.058-2.082) | <.001 | 1.612 (1.570-1.655) | <.001 |

| Divorced/separated | 1.361 (1.352-1.370) | <.001 | 1.241 (1.204-1.280) | <.001 |

| Widowed | 1.411 (1.403-1.419) | <.001 | 1.417 (1.377-1.458) | <.001 |

| Education level† | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| Some high school or less (reference) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| High school graduate (≥4 y) | 1.047 (1.042-1.052) | <.001 | 0.969 (0.952-0.986) | <.001 |

| Some college/associates degree | 1.174 (1.167-1.181) | <.001 | 1.030 (1.010-1.051) | .004 |

| College graduate (≥4 y) | 1.163 (1.155-1.171) | <.001 | 0.984 (0.963-1.007) | .174 |

| Advanced degree | 1.206 (1.196-1.216) | <.001 | 1.000 (0.974-1.026) | .991 |

| Race | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| White (reference) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Black or African American | 0.669 (0.666-0.672) | <.001 | 0.680 (0.664-0.695) | <.001 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0.776 (0.768-0.783) | <.001 | 0.575 (0.552-0.599) | <.001 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.888 (0.869-0.906) | <.001 | 0.884 (0.804-0.972) | .011 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic (reference) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Hispanic | 1.089 (1.082-1.096) | <.001 | 0.843 (0.824-0.864) | <.001 |

| Primary cancer diagnosis‡ | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| Acute leukemia (reference) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Chronic leukemia | 0.887 (0.870-0.904) | <.001 | 0.829 (0.810-0.849) | <.001 |

| Aggressive lymphoma | 1.244 (1.209-1.279) | <.001 | 1.141 (1.103-1.180) | <.001 |

| Nonaggressive lymphoma | 1.077 (1.044-1.110) | <.001 | 1.181 (1.136-1.227) | <.001 |

| Myeloma | 1.325 (1.305-1.344) | <.001 | 1.338 (1.313-1.364) | <.001 |

| Other leukemia/lymphoma | 1.155 (1.140-1.169) | <.001 | 1.133 (1.115-1.152) | <.001 |

Martial status is unknown in 0.7% of the 2003-2015 data file.

Education level is unknown in 38.5% of the 2003-2015 data file.

Acute leukemia includes acute myeloid and acute lymphocytic leukemias; chronic leukemia includes chronic myeloid and chronic lymphocytic leukemias; aggressive lymphoma includes diffuse large B-cell and Burkitt’s lymphomas; nonaggressive lymphoma includes Hodgkin disease and follicular lymphoma; and myeloma includes multiple myeloma, plasma cell leukemia, and plasmacytoma.

Discussion

In this study of all hematological cancer deaths over the past 17 years in the United States, hospital deaths decreased by 30%, with a corresponding rise in home and hospice facility deaths. Despite this overall trend, patients with HMs remained more likely to die in the hospital than patients with solid tumors.

Hospital death has been associated with worse outcomes, with unmet symptom needs for patients10 and prolonged grief disorder for caregivers.11 Appropriate hospice referral and clinician-led shared decision making for end-of-life care can improve goal attainment12 and reduce hospital deaths.13 Unfortunately, patients with HMs have lower palliative care utilization, and surveys show that hematological oncologists may harbor more philosophical resistance to making referrals.14 They may also be less comfortable having goals-of-care discussions,15 especially with those with chronic/indolent lymphomas.16 Additionally, patients themselves may have unrealistic treatment expectations16 and prefer aggressive care, with 28% stating a preference to die in the hospital.17

Obstacles to palliative care and hospice enrollment may stretch beyond patient and physician perceptions and resistance. Patients with HMs can have uncertain disease trajectories, making it difficult to appropriately identify when to transition away from active treatment.16 There is also evidence that patients with HMs have higher symptom burden,18 which sometimes warrants blood products for palliation; a recent study showed that the rate of transfusion dependence at death or hospice enrollment was 20%.19 Financial constraints driving transfusion exclusion in hospice policies may ironically end up driving up overall health care costs, as patients ultimately end up requiring more costly hospitalizations at the end of life.

Despite these barriers, there have been reports of increased rates of hospice admission and home deaths,20 consistent with our study findings. This overall positive trend may reflect the national shift toward considering palliative care vital to the cancer care continuum. Proliferation of the hospice industry has improved access, although there is still geographic variability,21 which may partially explain the significant state-to-state variation seen in this study. Given the stark regional disparities in place of death, however, there are also likely important social and demographic differences at play. Utah, for example, has the highest rate of home death and the lowest rate of hospice facility death; this may reflect both a population with strong family units (and thus the capacity to care for loved ones at home) and potential religious objection to care in a hospice facility, which may be associated with “giving up.” Alternatively, Florida, with >1 in 5 patients dying in a hospice facility, may reflect the coexistence of an aging retirement population and readily available care facilities.

Our study highlights important racial disparities in end-of-life care, with nonwhite and Hispanic patients much less likely to die at home or in a hospice facility. Although there were important decreases in hospital death rates across all races over time, the utilization gap remained grossly stable. This means that the relative disparity between, for example, white and black or African American patients actually grew with time. These findings are consistent with prior research showing that these populations are at risk for health care disparities,22,23 either because of a desire for more aggressive end-of-life care, distrust of the health care system, or decreased referral by providers to palliative care services.

Likewise, significant variation based on cancer subtype identifies patients for whom palliative care services may not be optimally deployed. Whereas patients with myeloma have high hospice enrollment and limited late enrollment,24 patients with acute leukemia are at high risk for aggressive care and hospital death.8,9 This may be due to initial presentation for patients with acute leukemia, where both diagnosis and death may occur in the same hospitalization, or to the increased risks for bleeding and infection that come with standard induction chemotherapy regimens, which may require prolonged hospital stays. Patients with chronic leukemia may have the lowest rate of home death because, as an older population, they require more significant care needs and thus disproportionately die in nursing facilities.

Our study has several limitations. Inaccuracy of death certificates may have led to potential discrepancies, although an expert panel found high fidelity in a retrospective review.25 Access to and utilization of hospice care vary widely by income, insurance, and county-level resources, data on which were not available for this analysis. Finally, this place-of-death study may not accurately reflect the intensity of end-of-life care, because patient death on a palliative care service in a hospital would still be coded as “hospital death” in this study.

In conclusion, despite overall improvements, patients with HMs in the United States remain more likely to die in the hospital than at home. Concerning disparities exist along age, marital status, cancer subsite, race, and ethnic lines. Continued efforts are needed to improve the provision of quality end-of-life care in hematology.

Footnotes

Presented as a poster discussion in Patient and Survivor Care at the 2018 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, 4 June 2018.

Authorship

Contribution: F.C. designed research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; A.H.K. designed research and wrote the paper; and J.C. and T.W.L. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.W.L. notes funding from American Cancer Society, Cambia Foundation, Seattle Genetics, and AstraZenca and consultancies/advisory boards at AbbVie, Agios, Amgen, CareVive, Celgene, Helsinn, Heron, Medtronic, Otsuka, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, and Welvie. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Fumiko Chino, Duke University Medical Center, DUMC 3085, Durham, NC 27710; e-mail: fumiko.chino@duke.edu.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures, 2018. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2018/cancer-facts-and-figures-2018.pdf. Accessed 18 March 2018.

- 2.Macmillan Cancer Support. No regrets: How talking more openly about death could help people die well. https://www.macmillan.org.uk/documents/aboutus/health_professionals/endoflife/no-regrets-talking-about-death-report.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2018.

- 3.Gomes B, Higginson IJ, Calanzani N, et al. ; PRISMA. Preferences for place of death if faced with advanced cancer: a population survey in England, Flanders, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(8):2006-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(23):3860-3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreno-Alonso D, Porta-Sales J, Monforte-Royo C, Trelis-Navarro J, Sureda-Balarí A, Fernández De Sevilla-Ribosa A. Palliative care in patients with haematological neoplasms: An integrative systematic review. Palliat Med. 2018;32(1):79-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruera E, Russell N, Sweeney C, Fisch M, Palmer JL. Place of death and its predictors for local patients registered at a comprehensive cancer center. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(8):2127-2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeBlanc TW, Abernethy AP, Casarett DJ. What is different about patients with hematologic malignancies? A retrospective cohort study of cancer patients referred to a hospice research network. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(3):505-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang R, Zeidan AM, Halene S, et al. Health care use by older adults with acute myeloid leukemia at the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3417-3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Jawahri AR, Abel GA, Steensma DP, et al. Health care utilization and end-of-life care for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2015;121(16):2840-2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291(1):88-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, Matulonis UA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(29):4457-4464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1203-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein RA, Sharpe L, Bell ML, Boyle FM, Dunn SM, Clarke SJ. Randomized controlled trial of a structured intervention to facilitate end-of-life decision making in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(27):3403-3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeBlanc TW, O’Donnell JD, Crowley-Matoka M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among hematologic malignancy specialists: a mixed-methods study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):e230-e238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hui D, Bansal S, Park M, et al. Differences in attitudes and beliefs toward end-of-life care between hematologic and solid tumor oncology specialists. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(7):1440-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Condron NB, et al. Barriers to quality end-of-life care for patients with blood cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(26):3126-3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howell DA, Wang HI, Roman E, et al. Preferred and actual place of death in haematological malignancy. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(2):150-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochman MJ, Yu Y, Wolf SP, et al. : Comparing the palliative care needs of patients with hematologic and solid malignancies. J Pain Symptom Manage. 55(1):82-88.e1, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeBlanc TW, Egan PC, Olszewski AJ. Transfusion dependence, use of hospice services, and quality of end-of-life care in leukemia. Blood. 2018;132(7):717-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howell DA, Wang HI, Smith AG, Howard MR, Patmore RD, Roman E. Place of death in haematological malignancy: variations by disease sub-type and time from diagnosis to death. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson MD, Bradley EH, Du Q, Morrison RS. Geographic access to hospice in the United States. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(11):1331-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhatt VR, Shostrom V, Gundabolu K, Armitage JO. Utilization of initial chemotherapy for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia in the United States. Blood Adv. 2018;2(11):1277-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Earle CC, LaCasce AS, Abel GA. Hospice use among patients with lymphoma: impact of disease aggressiveness and curability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108(1):djv280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odejide OO, Li L, Cronin AM, et al. Meaningful changes in end-of-life care among patients with myeloma. Haematologica. 2018;103(8):1380-1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner EL, Metcalfe C, Donovan JL, et al. Contemporary accuracy of death certificates for coding prostate cancer as a cause of death: Is reliance on death certification good enough? A comparison with blinded review by an independent cause of death evaluation committee. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(1):90-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]