Abstract

Background:

Drug pre-exposure attenuates sensitivity to the interoceptive stimulus properties of additional subsequently administered drugs in drug-induced conditioned taste avoidance (CTA) and conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigms. Specifically, nicotine, commonly used in conjunction with other addictive substances, attenuates acquisition of ethanol and caffeine As and morphine-induced CPP.

Methods:

Because nicotine use is comorbid with a number of substance use disorders, we systematically examined the effects of nicotine pre-exposure on two different conditioning paradigms involving integration of the interoceptive stimulus properties of multiple commonly abused drugs, in male and female rats, designed to examine both the aversive and reinforcing properties of these drugs.

Results:

Nicotine dose-dependently interfered with acquisition of CTA to passively administered morphine, ethanol, and cocaine, but not lithium chloride, demonstrating that the effects of nicotine are not simply a matter of reduced orosensory processing or an inability to learn such associations. Moreover, nicotine-treated rats required higher doses of drug in order to develop CTA and did not show increased acceptance of the taste of self-administered ethanol compared with saline-treated rats.

Conclusions:

These data demonstrate that nicotine pre-exposure attenuates sensitivity to the stimulus effects of multiple drugs in two conditioning paradigms, in a manner which is consistent with a reduced ability to integrate the interoceptive properties of abused drugs. Through reducing these stimulus properties of drugs of abuse, concomitant nicotine use may result in a need to increase either the frequency or strength of doses during drug-taking, thus likely contributing to enhanced addiction liability in smokers.

Keywords: Nicotine, Interoception, Cocaine, Morphine, Ethanol, Sensitivity

1. Introduction

Many commonly abused drugs paradoxically increase the incentive salience of contextual stimuli (Berridge and Robinson, 1998; Flagel et al., 2009; Robinson et al., 2015; Uslaner et al., 2006) while simultaneously conditioning avoidance responses to paired orosensory stimuli (Imperio and Grigson, 2015; Jenney et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2009; Parker, 1995, 2003). This is in contrast to the effects of primarily emetic stimuli, such as lithium chloride (LiCl), which result in both conditioned place and taste avoidance (CPA and CTA, respectively; Parker, 2003; Tenk et al., 2005, 2006). Conversely, drug self-administration under some conditions can increase the acceptance of paired orosensory stimuli (Loney and Meyer, 2018), as defined by a relative reduction in rejection, suggestive of an increase in palatability. These positive and negative changes in hedonic stimulus value, (i.e.,, conditioned taste revaluation; CTR) are often used to assess sensitivity to drug reinforcement (Imperio and Grigson, 2015; Jenney et al., 2016), and can be used to infer changes in the interoceptive stimulus properties of a given drug. Both avoidance and appetitive CTR is dependent on the interoceptive stimulus properties of the unconditioned stimulus (US); exteroceptive stimuli (e.g., foot shock, acoustic startle) do not result in a revaluation of taste stimuli (Garcia and Koelling, 1966). Therefore, the qualitative stimulus properties of a drug US are important factors influencing their ability to induce CTR. For instance, the avoidance response conditioned by drugs such as cocaine and morphine is putatively dependent on reinforcing stimulus properties (Grigson and Freet, 2000). Yet, in the case of ethanol, the conditioned avoidance response is primarily due its aversive stimulus properties (Liu et al., 2009) while oral ethanol self-administration results in appetitive CTR likely due to its reinforcing pharmacological stimulus properties (Ackroff and Sclafani, 2003; Kiefer et al., 1994; Loney and Meyer, 2017).

Pre-exposure to drugs of abuse can attenuate the strength of CTR induced by subsequent drug exposure (Braveman, 1979; Serafine and Riley, 2010; Switzman et al., 1981). For example, both acute and chronic nicotine pre-exposure interferes with the acquisition of CTA to ethanol and caffeine-paired saccharin solutions (Bienkowski et al., 1998; Kunin et al., 2001; Kunin et al., 1999; Rinker et al., 2011) without affecting responding to the taste of saccharin itself. As such, nicotine pre-exposure could interfere with ethanol-CTA, for example, by decreasing its aversive, or increasing its reinforcing, interoceptive effects (Troisi et al., 2013). For instance, nicotine may reduce the impact of the aversive interoceptive effects of ethanol administration (e.g., hypothermic effects) and thus reduce the efficacy for ethanol to serve as a salient (Rinker et al., 2011). Conversely, nicotine may increase the reinforcing properties of ethanol and thus interfere with the acquisition of an avoidance response by favoring the acquisition of an appetitive response.

However, nicotine pre-exposure could impact the sensitivity to the interoceptive stimulus properties of these drugs in a quantitative manner, by reducing sensitivity to drug interoceptive cues, as if a lower dose were administered, thus diminishing their ability to induce either avoidance or appetitive CTR. For instance, pretreatment with nicotine dose-dependently interferes with drug discrimination (Perkins et al., 1996) and human smokers are less sensitive to the analgesic effects of opiates (Ackerman, 2012; Qiu et al., 2011; Steinmiller et al., 2012) and nicotine reduces the stimulus properties of cocaine in humans (Kouri et al., 2001). Likewise, chronic nicotine pre-exposure interferes with the acquisition of morphine-induced CPP (Zarrindast et al., 2003). As such, nicotine may reduce the sensitivity to these internal cues of drug administration thus reducing the efficacy of these drugs to induce CTR. As a result, any nicotine pre-exposure effects on CTR would likely manifest similarly across both avoidances, and appetitive CTR as the quantitative properties of the drug US would be most impacted.

The exact mechanisms through which US pre-exposure impacts subsequent conditioning are currently unknown. Furthermore, the generalization of the effect of nicotine to diminish ethanol-induced CTA to those induced by morphine, cocaine, and LiCl is unknown. Because nicotine use is comorbid with a number of other substance use disorders (Kohut, 2017; Smith et al., 2011; Tuesta et al., 2011) and can interfere with the interoceptive processing of commonly abused drugs (Rinker et al., 2011; Steinmiller et al., 2012; Troisi and Craig, 2015; Zarrindast et al., 2003), the goal of the present study was to systematically test the effect of nicotine in appetitive and avoidance CTR paradigms designed to test sensitivity to the reinforcing and aversive stimulus properties of a number of commonly abused drugs. First, we examined the effects of pre-exposure with two nicotine doses on avoidance CTR induced by administration of multiple drugs thought to rely on either the reinforcing properties (e.g., cocaine and morphine) or the aversive properties (e.g., ethanol and LiCl) of the drug to condition avoidance responses in male rats. Next, we assessed the effects of nicotine on ethanol induced CTA in female rats. Finally, we tested the effects of acute nicotine on the appetitive CTR that occurs following repeated ethanol exposure in male rats. Our hypothesis was that if nicotine pre-exposure impacts the qualitative (reinforcing or aversive) properties of a drug (e.g., ethanol) then we should see a dissociation between avoidance and appetitive CTR. In contrast, we found that nicotine interfered with both avoidance and appetitive CTR conditioned by all drugs of abuse tested, which indicates that the effects appear to be of a quantitative fashion as both qualities of CTR (avoidance and appetitive) were attenuated and nicotine-treated rats required higher doses of the drug in order to demonstrate revaluation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Housing

139 male (Experiments 1–3) and 44 female (Experiment 2) adult Long-Evans rats (Envigo, Haslett, Michigan) were individually housed in polycarbonate cages in a temperature and humidity-controlled vivarium on a reverse 12-hour light cycle. Rats were approximately 70 days old on arrival to the facility and were handled for three days prior to training and testing. Standard rodent chow (Harlan 2018) was available ad libitum. Rats were maintained on ~23.5-hour water deprivation throughout training and testing in order to facilitate fluid consumption during the access period. Prior to training and testing, group assignments were made in a weight-balanced fashion and rats in nicotine groups were given three injections of their assigned dose to familiarize the animals to the potentially aversive effects of the drug.

2.2. Stimuli

(−)-Nicotine hydrogen tartrate salt (Glentham Life Sciences) was dissolved in saline at concentrations of either 0.4 or 0.6 mg/ml (expressed as base), and the pH was adjusted to 7.2–7.4 with sodium hydroxide (Matta et al., 2007). Injections were administered subcutaneously 30 min (Experiments 1 and 2) or 15-min (Experiment 3) prior to testing. We shortened the delay for Experiment 3 because we were initially concerned with the time course of nicotine’s effects. Specifically, fluid access is spaced out across the entire 30 min period in the Davis rig, and therefore consumption is occurring for the majority of the 30 min and not front-loaded during the test period as is typically seen in home cage drinking (i.e., Experiment 1 and 2).

For CTA experiments (Experiments 1 and 2), five chemicals served as unconditioned stimuli: saline, a 16% (v/v) ethanol solution diluted with saline from an undenatured 200 proof stock solution (Decon Labs), 20 mg/ml cocaine HCl (NIDA drug supply program) dissolved in saline, 15 mg/ml morphine sulfate (Spectrum Chemicals) dissolved in saline, and 38 mM LiCl (Fisher) dissolved in reverse osmosis water. All unconditioned stimuli were injected intraperitoneal. Ethanol was injected at a dose of 1.3 g/kg, cocaine at a dose of 20 mg/kg, morphine at doses of 15 or 45 mg/kg, and LiCl at a dose of 0.5 mEq/kg. Doses were chosen to produce CTA reliably and to be consistent with previously published literature employing similar methodology (e.g., Geddes et al., 2008). We chose the relatively low dose (Nunnink et al., 2007) of LiCl because a previous report demonstrated that 0.3 mEq/kg LiCl was below the threshold for inducing a CTA (Rabin et al., 1987). Furthermore, because previous reports have demonstrated that nicotine interferes with an EtOH-induced CTA and we were interested in comparing the effects of nicotine pretreatment on EtOH- and LiCl-induced CTA, we chose 0.5 mEq/kg which in our hands reliably produces CTA and which is comparable to 1.3 g/kg EtOH. Saline injections were matched to LiCl injection volume. A 0.1 % saccharin (Sigma) solution, dissolved in tap water, served as the conditioned stimulus (CS+).

For the brief-access licking experiments (Experiment 3), ethanol, diluted with tap water, was presented at 6-concentrations: 1.25, 2.5, 5.0, 10, 20 and 40 % (v/v).

2.3. Experiments 1 and 2: Conditioned Taste Avoidance

Previous work has shown that nicotine pre-exposure reduces the impact of EtOH in CTA paradigms. Here we tested the effect of nicotine pretreatment on the efficacy of a number of commonly abused drugs to induce CTA in male and female rats. Experiment 1 examined the effect of nicotine pretreatment on CTA induced by EtOH, cocaine, morphine, and LiCl in male rats while Experiment 2 examined the effect of nicotine pretreatment on CTA induced by EtOH in female rats.

2.3.1. Training.

Rats were trained to consume tap water from a single bottle during a 30-min access period. Once intakes had stabilized, rats were administered their assigned drug injection (0.4 or 0.6 mg/kg nicotine or saline) 30-min prior to the water access period for three days to ensure fluid consumption restabilized following nicotine treatment.

2.3.2. Testing.

Rats continued to receive their daily water during the 30-min access period from a single bottle. On day 1, rats were injected with their assigned drug (nicotine or saline) 30 min prior to access to water for 30 min. On day 2, rats were again injected with their assigned drug, and then given 30-min access to a novel 0.1% saccharin solution (CS+) followed immediately by administration of the US (ethanol, morphine, cocaine, saline or LiCl). Nicotine was administered on each day of testing in an attempt to ensure that nicotine itself did not serve as a US and that it did not serve as an occasion setter predicting US administration Bevins and Palmatier (2004). This two-day pattern was repeated for a total of four CS+ and US pairings. Following conditioning, rats were given a choice between the CS+ and water in their home cage for 24h. Neither nicotine nor saline was administered during this preference test. Bottles were weighed prior to being placed on the home cage and weighed again immediately following consumption.

2.4. Experiment 3: Appetitive Brief-Access Licking Test

Repeated, brief self-administrations of EtOH result in appetitive CTR as evidenced by a substantial increase in licking generated by higher concentrations of EtOH following prior experience (Loney and Meyer, 2018). Here, we tested if the effects of nicotine in the pre-exposure paradigm were specific to avoidance CTR by examining the effect of nicotine pre-treatment on appetitive CTR induced by EtOH. Brief-access licking tests were conducted in an automated lickometer (Davis rig MS-180; DiLog Instruments) comprising a polycarbonate cage coupled to a computer-controlled table housing several fluid reservoirs. Access to each reservoir is occluded by an automated shutter, allowing for brief presentations of multiple concentrations of a solution presented in random order.

2.4.1. Training.

Rats were trained to consume water from the Davis rig as described previously (Loney and Meyer, 2018). Briefly, rats were adapted to the fluid presentation schedule in the Davis rig for 30-min sessions across 5-consecutive days. On the last three days of training, rats were injected subcutaneously with their assigned drug (0.4 mg/kg nicotine or saline) 15-min prior to their training session in order to familiarize the rats to the stress of injections and the effects of nicotine.

2.4.2. Testing.

During testing, rats were given serial, random presentations of ethanol concentrations or water for 10 s each, followed by a 1 s water rinse. Rats could freely lick for the 10-s access period and could initiate as many trials as possible during the 30-min session. Each trial was separated by a 10-s inter-trial interval before the presentation of the next trial. Licking must have been initiated on the current trial for a new trial to be presented.

Testing was conducted on three noncontiguous days within a week, and the rats were allowed to rehydrate overnight following each test day. The first three days served as the Baseline test. 72 hours later, the rats were reassessed in the Davis rig under identical conditions and these next three days served as the Reassessment test.

72 hours after the last Reassessment test, the rats were again tested in the Davis rig with the critical modification that drug assignments were switched such that nicotine-treated rats were now tested following saline injections and previously saline-treated rats were now administered nicotine. These next three days served as the Switch-test and were included to test if any effects of nicotine within this paradigm were the result of ongoing, acute administrations of nicotine. Two rats from the saline group were mistakenly excluded from the Switch-test. See Figure 1 for a timeline for each included experiment.

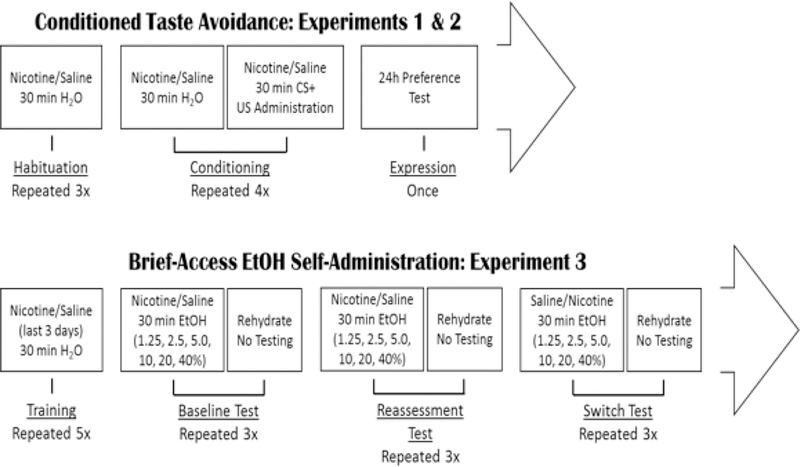

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrating the time course and experimental design of Experiments 1–3. In Experiments 1 (males) and 2 (females) a CTA design was employed in which animals were habituated to 30 min water access following nicotine or saline administration. Following habituation, animals were conditioned to the effects of their assigned drug US through pairing with 0.1% saccharin. Each conditioning day was followed by a non-conditioning day on which animals were given water to drink and no US. Nicotine was administered every day of testing 30 min prior to fluid access. For experiment 3, rats were habituated to the effects of nicotine for the last three days of training, following which they were given three non-contiguous days of brief-access to randomized concentration of EtOH 15 min after nicotine or saline injections. These three days served as the Baseline test representing the animals’ initial evaluation of the taste of EtOH. The following week, rats were again tested under identical parameters, this test served as the Reassessment test, representing the animals’ evaluation of the taste of EtOH following exposure in the Baseline test. On the third week, drug assignments were switched such that previously nicotine-treated rats now received saline and vice versa. This test served as the Switch test and was included to determine if nicotine was impacting expression of an already conditioned taste response or if the effects were most relevant during acquisition of conditioning.

2.5. Data Analyses

Mean intakes (Experiments 1 and 2), group sizes, and additional analyses are presented in supplementary tables1. For ease of comparison, consumption data were transformed and depicted as a relative intake score (i.e., the % of CS+ consumed by each rat relative to their respective unconditioned control group). These scores were analyzed in a three-factor mixed ANOVA with nicotine Dose (0.0, 0.4, and 0.6 mg/kg) and (ethanol, morphine, cocaine, saline and LiCl) as between-subjects’ factors and conditioning Day as within-subjects factor.

Sensitivity to CS+ intake suppression following conditioning with morphine was assessed by calculating the degree of change in saccharin intake on each subsequent conditioning day, relative to their day one intakes, prior to the occurrence of any conditioning. These data were compared in a three-factor ANOVA with morphine Dose and Nicotine treatment as a between-subjects’ factors and conditioning Day as the within-subjects factor.

Preference for the CS+ (g of CS+ consumed/fluid consumed) was analyzed with a two-factor ANOVA with nicotine Dose and US as a between-subjects’ factors.

Brief-access licking data were transformed into a lick score wherein the average licks to a given concentration of ethanol were divided by the average licks to water by the same rat. These transformations control for individual differences in the motivation to rehydrate and local lick rate. Lick scores were analyzed in a three-factor mixed ANOVA with nicotine Dose as between-subjects factor and Test (Pre vs. Post) and Concentration as within-subjects’ factors.

Curves were fit to the lick ratios, and the EC50 was calculated for both stimuli using a three-parameter logistical function:

Where a is equal to asymptotic licking, b is equal to the slope of the curve and c is the EC50 or the concentration at which one-half asymptotic licking was seen. Curve fitting was conducted with Systat 12.

Fisher’s post-hoc comparisons were conducted where appropriate.

ANOVAs were conducted in STATISTICA 12.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1

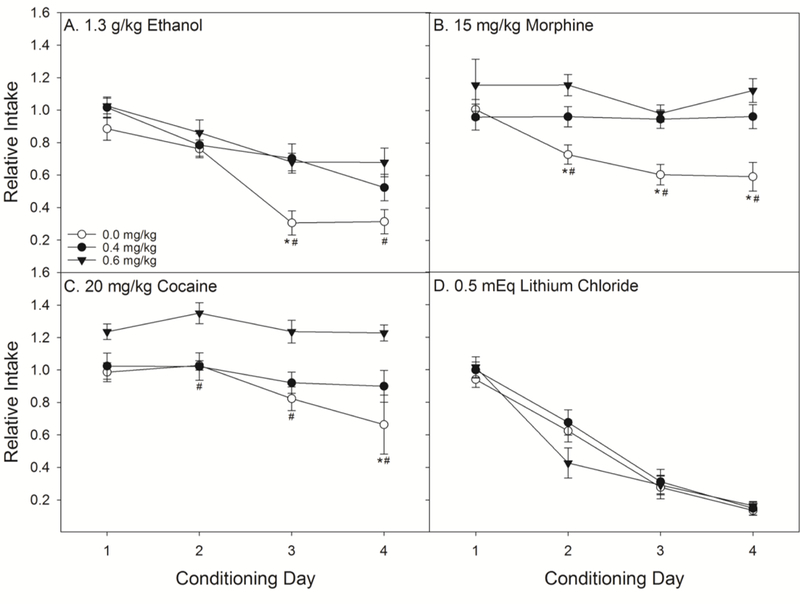

Nicotine pre-treatment resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in the strength of avoidance conditioned by ethanol, morphine, and cocaine with no effect on that conditioned by LiCl (Figs 2 and 3). The three-factor ANOVA on relative intake revealed a Dose x S x Day interaction (F(18, 231) =1.73, P < 0.05; Fig 2). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that, relative to saline, rats pre-treated with 0.4 mg/kg of nicotine were significantly more accepting of saccharin on day 3 of ethanol conditioning, days 2–4 of morphine conditioning, and day 4 of cocaine conditioning. Rats pre-treated with 0.6 mg/kg nicotine, relative to saline, drank significantly more saccharin on days 3 and 4 of ethanol, days 2–4 of morphine, and all days of cocaine conditioning. Rats pre-treated with either dose of nicotine did not suppress their intake to morphine or cocaine but did to ethanol and LiCl. Saline pre-treated rats did not differ from either dose of nicotine during conditioning with LiCl. Post hoc comparisons revealed no differences across days in the avoidance conditioned by 1.3 g/kg EtOH and that conditioned by 0.5 mEq/kg LiCl in saline pre-treated rats, indicating that these two doses were appropriately matched for intensity.

Figure 2.

Pre-treatment with nicotine dose-dependently interfered with the revaluation of taste stimuli paired with EtOH (n’s = 7–9 per dose), morphine (n’s = 8 per dose) and cocaine (n’s = 6–8 per dose), but not LiCl (n’s = 7–8 per dose). Nicotine limited acquisition of the avoidance of 0.1% saccharin that was paired with drugs of abuse across four conditioning days. There was no effect of either dose of nicotine (0.4 or 0.6 mg/kg) on the conditioning with LiCl. *’s indicate that rats in the saline-pre-treatment group were significantly less accepting of saccharin than rats pre-treated with 0.4 mg/kg nicotine. #’s indicate that saline pre-treated rats were less accepting of saccharin than rats receiving 0.6 mg/kg nicotine (Ps < 0.05).

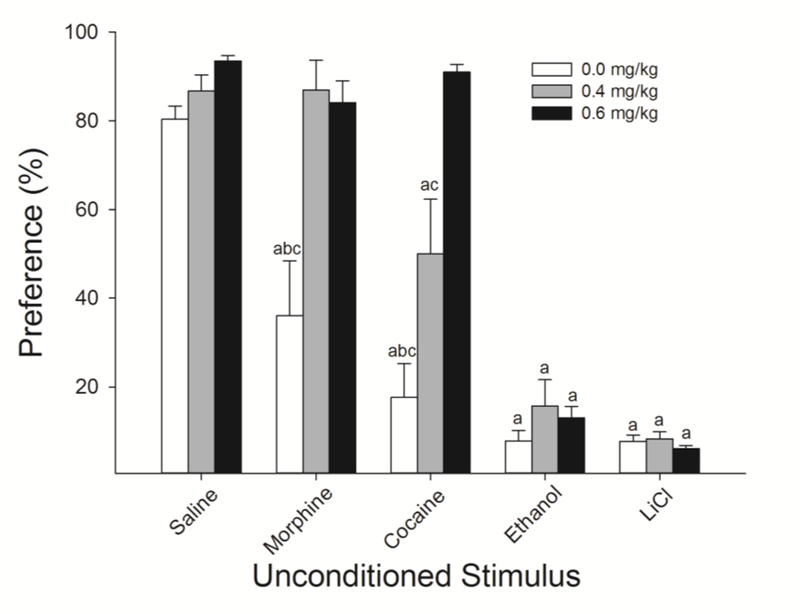

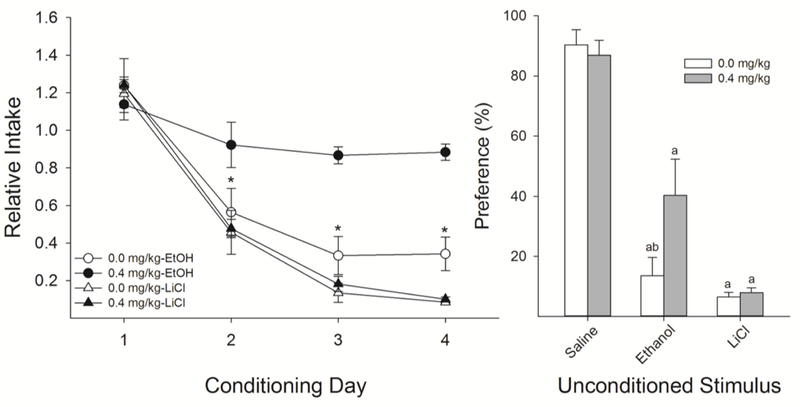

Figure 3.

Nicotine administered during acquisition of avoidance CTR dose-dependently interfered with the later expression of CTA induced by cocaine and morphine as assessed through a 24-h two-bottle preference test. Nicotine-treatment had no effect on the acceptance of 0.1% saccharin in unconditioned controls. Nicotine-treated rats were significantly more accepting of saccharin following conditioning with morphine (15 mg/kg) and cocaine (20 mg/kg). Despite the significant effects of nicotine on acquisition of EtOH-induced CTR (Fig 1), neither dose of nicotine resulted in a statistically significant increase in acceptance of saccharin following pairing with 1.3 g/kg EtOH. Again, there were no effects of nicotine on acceptance following LiCl conditioning. a’s indicate that preference was significantly lower than that group’s respective unconditioned control; b’s indicate significantly lower preference than 0.4, and c’s indicate significantly lower preference than 0.6 mg/kg nicotine (Ps < 0.05).

Analyses of the 24 h preference test revealed similar results as during acquisition. The two-factor ANOVA resulted in a Dose x US interaction (F(8,96) = 7.72, P < 0.0001; Fig 3). Post-hoc analyses revealed no effect of nicotine on the preference for saccharin in unconditioned controls. Both doses of nicotine blocked the decrease in preference observed following conditioning with morphine and a dose-dependent attenuation of the decrease in preference conditioned by cocaine. The slightly higher preference for saccharin in nicotine-, relative to saline-treated, rats following conditioning with ethanol failed to survive correction for multiple comparisons despite the clear differences in the acquisition data (Fig 2) suggesting that the slight decrease in acceptance across days was sufficient to impact preference when not motivated to consume saccharin. As in the acquisition data, there were no effects of nicotine on the preference for saccharin following pairing with LiCl.

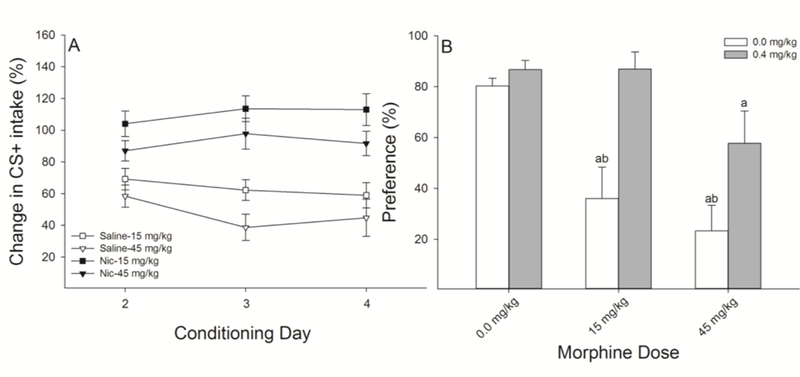

Because we found no difference in the expression of CTA induced by the dose of EtOH matched to LiCl in the two-bottle preference tests between saline and nicotine pre-treated rats we next compared the degree of CS+ suppression induced by 15 mg/kg of morphine to that induced by a substantially higher dose of morphine (45 mg/kg) as a function of nicotine pre-treatment. This dose of morphine was selected to induce comparable CTA in saline pre-treated rats to that induced by 0.5 mEq/kg LiCl. When comparing conditioning with 45 mg/kg of morphine and 0.5 mEq/kg LiCl we found no main effect of US (F(1,13) = 1.90, P = 0.19) indicating that the chosen drug doses were relatively comparable. We found that nicotine pre-treatment did not result in a total blockade of conditioning by morphine, but rather appeared to reduce the sensitivity while retaining a similar degree of dose-dependency, relative to saline (Fig 4A). The three-factor ANOVA revealed significant main effects of Nicotine (F(1,40) = 39.20, P < 0.0001) and morphine Dose (F(2,40) = 13.40, P< 0.0001) and a Nicotine by Dose interaction (F(2,40) = 6.13, P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Nicotine pre-treatment reduces the sensitivity to the revaluation effects of morphine. A.) Nicotine, relative to saline, reduced the level of acquisition of avoidance CTR induced by both doses of morphine (15 and 45 mg/kg; n’s = 6–8 per group) but did not completely block it. For clarity, because there were no effects of nicotine on saccharin intake in the unconditioned rats, these acquisition data are not depicted B.) 24-h two bottle preference tests revealed that nicotine, relative to saline, blocked, and reduced, the avoidance of saccharin conditioned by 15 and 45 mg/kg morphine, respectively. Together, these data demonstrate that nicotine preserves the dose-dependent effects of morphine administration, yet results in rats that are less sensitive to the effects of morphine, as assessed through avoidance CTR. a’s indicate that preference was significantly lower than that group’s respective unconditioned control; b’s indicate significantly lower preference than 0.4 mg/kg nicotine.

Analyses of the 24-h preference expression test revealed a similar pattern of results, with both saline- and nicotine-treated rats displaying a dose-dependent decrease in acceptance of saccharin following conditioning with morphine, albeit the overall level of avoidance being lower in nicotine-treated rats (Fig 4B). The two-factor ANOVA resulted in a Drug x Dose interaction (F(2,40) = 3.54, P < 0.05). Post-hoc analyses revealed that saline-treated rats were less accepting of saccharin following conditioning with 15 and 45 mg/kg morphine and nicotine-treated rats were less accepting following 45 mg/kg, all relative to their respective unconditioned controls. Nicotine-treated rats, relative to saline-treated rats, had a higher preference for saccharin following conditioning with both 15 and 45 mg/kg morphine. Importantly, nicotine pre-treatment did significantly attenuate acquisition of 45 mg/kg morphine, a dose relatively comparable in efficacy to 0.5 mEq/kg LiCl in saline pre-treated rats.

3.2. Experiment 2

Similar to male rats, pre-treatment with nicotine decreased the avoidance conditioned by ethanol but not LiCl (Fig 5). Analyzing relative intake, we again found a significant three-way interaction (F(3,66) = 5.70, P < 0.01; Fig 4). Post-hoc analyses revealed nicotine-treated, relative to saline-treated, rats were significantly more accepting of saccharin on conditioning days 2–4. There were no effects of nicotine on conditioning with LiCl.

Figure 5.

Similar to male rats, nicotine pre-treatment interferes with avoidance CTR induced by EtOH (n’s = 7 per group), but not LiCl (n’s = 6 per group). The effects of nicotine on acquisition of EtOH-induced CTR has thus far only been shown in male rats. A.) Female rats treated with 0.4 mg/kg nicotine, compared to saline, were more accepting of 0.1% saccharin during conditioning with 1.3 g/kg EtOH with no effects on conditioning with LiCl. B.) Acceptance of saccharin following conditioning with EtOH was higher in nicotine-treated female rats relative to saline-treated female rats. There was no effect on LiCl. a’s indicate that preference was significantly lower than that group’s respective unconditioned control; b’s indicate significantly lower preference than 0.4 mg/kg nicotine.

Analyses of the 24-h preference test supported these findings with a Drug x US interaction (F(2,38) = 3.31, P < 0.05; Fig 4B). Post-hoc analyses revealed that nicotine-treated female rats had a significantly higher preference for saccharin following conditioning with EtOH relative to saline-treated female rats. There were no differences in preference as a result of drug treatment for either LiCl-conditioned or saline-unconditioned female rats.

3.3. Experiment 3

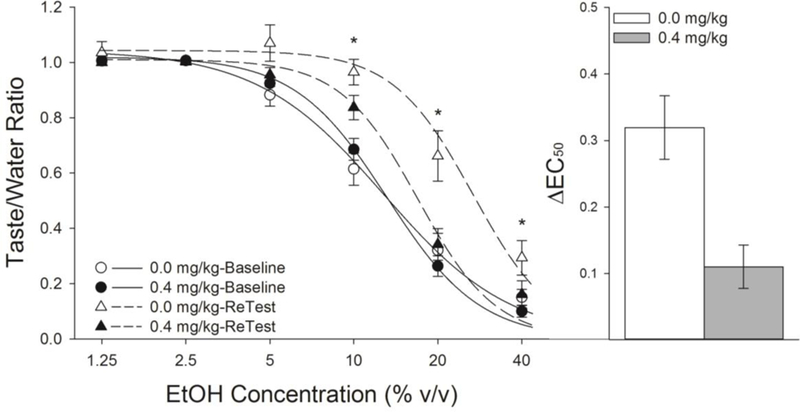

We next tested if the effects of nicotine in the pre-exposure paradigm were specific to avoidance CTR by examining the effect of nicotine pre-treatment on appetitive CTR induced by repeated brief self-administrations of EtOH. Similar to avoidance CTR (Experiments 1 and 2), nicotine attenuated appetitive CTR induced by EtOH self-administration. The three-factor ANOVA comparing the effects of nicotine on the initial Baseline assessment of the taste of EtOH and the Reassessment resulted in a significant Drug x Test x Concentration interaction (F(5,60) = 2.86, P < 0.05; Fig 6). Post-hoc analyses revealed no effects of nicotine on the initial (Baseline) assessments of the taste of EtOH. Following experience with EtOH (Reassessment test), saline-treated, relative to nicotine-treated, rats licked significantly more to 10, 20 and 40%, with a trend (P = 0.056) towards increased licking at 5%, EtOH. Comparisons of the ΔEC50, a measure of the lateral shift in the concentration-response function, revealed a significantly larger rightward shift (F(1,12) = 13.14, P < 0.01; Fig 6) in the acceptance of the taste of EtOH in saline-treated, compared to nicotine-treated, rats.

Figure 6.

Nicotine interfered with the appetitive CTR induced by repeated self-administration of brief-access EtOH (n’s = 7 per group). There were no differences in the acceptance of the taste of EtOH between nicotine- and saline-treated rats on their initial assessment (Baseline). Following experience with EtOH, saline-treated rats displayed an increased acceptance of the taste of EtOH upon reassessment (Retest), relative to nicotine-treated rats, despite an equal amount of experience with EtOH. Furthermore, the rightward lateral shift in the concentration response function in licking to EtOH was significantly greater in saline-treated rats, relative to nicotine-treated rats. *’s indicates significant group differences between 0.0 and 0.4 mg/kg nicotine during the Post-test ( Ps < 0.05).

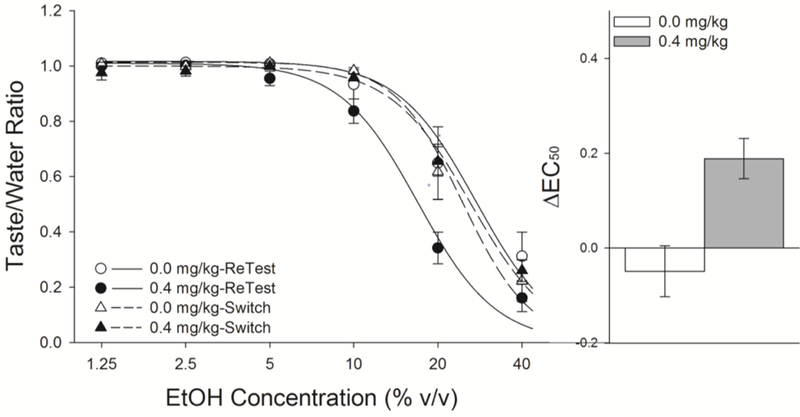

To determine if nicotine had any effect on expression of increased EtOH acceptance, we switched drug administrations and again exposed the rats to the taste of EtOH (Switch-test). Removal of nicotine resulted in the emergence of a significant rightward shift in the acceptance of the taste of EtOH, comparable to that seen in previously saline-treated rats while adding nicotine to rats familiarized with EtOH had no effect. This three-factor ANOVA resulted in a Drug x Test x Concentration interaction (F(5,50) = 6.2, P < 0.001). Post-hoc analyses revealed that the previous group differences were lost following exposure to EtOH in the absence of nicotine (Fig 7). Comparison of the ΔEC50 demonstrated that, with exposure to the taste of EtOH in the absence of nicotine, previously nicotine-treated rats now displayed a rightward lateral shift comparable to that seen following identical exposure in saline-treated rats while administering nicotine to rats previously conditioned with EtOH had no effect.

Figure 7.

Removal of nicotine treatment resulted in a comparable increase in acceptance of the taste of EtOH, following additional experience with EtOH, while addition of nicotine to familiarized rats had no appreciable effects. Formerly nicotine-treated rats that were given subsequent exposure to EtOH in the absence of nicotine increased acceptance of EtOH to match that of saline-treated rats (Fig 6). Administration of nicotine to EtOH-familiarized rats did not change their acceptance of the taste of EtOH indicating that nicotine is impacting acquisition of EtOH-induced CTR, not simply altering taste perception.

4. Discussion

The present studies reveal that nicotine pre-exposure attenuated CTA induced by EtOH, morphine, and cocaine in male (Figs 2 and 3) and EtOH in female rats (Fig 5). This phenomenon appears to be unique to drugs of abuse as nicotine had no effect on CTA induced by LiCl even at a relatively low dose (0.5 mEq/kg). These data complement existing findings that nicotine interferes with EtOH-induced CTA following acute pretreatment in adulthood and following chronic exposure in adolescence with later conditioning occurring in adulthood (Kunin et al., 1999; Rinker et al., 2011). Our results indicate that nicotine is not completely interfering with the ability to learn these associations, but rather interfering with the efficacy for a given drug dose to induce CTR in a quantitative manner. Specifically, rats pre-treated with nicotine, relative to saline, acquired morphine-induced CTA but required higher doses for their behavior to be impacted (Fig 4). Nicotine also interfered with appetitive CTR (EtOH self-administration; Fig 6) in a manner similar to avoidance CTR (CTA experiments; Fig 2). Furthermore, nicotine’s effects were specific to the acquisition of CTR because nicotine administered following CTR with EtOH (Fig 7) had no effect, demonstrating that expression of the learned response was not impacted by nicotine administration. Together, these data suggest that nicotine is likely not impacting the qualitative experience of drugs as assessed through CTR, but rather the quantitative experience.

With the present experiments we attempted to determine whether the nicotine pre-exposure paradigm interfered with drug-induced CTR by reducing sensitivity and thus impacting the quantitative aspects (i.e., influencing the degree to which a given US dose is capable of inducing CTR) or impacting the qualitative, motivational aspects of passive drug administration (i.e., influencing the relative balance of reinforcing or aversive US properties). Given our findings, we conclude that the effects of nicotine on CTR are likely quantitative in nature. For example, as the morphine dose was increased, both nicotine and saline groups showed a dose-dependent decrease in saccharin acceptance. However, rats that were administered nicotine, relative to saline, show a vertical shift in acceptance of saccharin following conditioning with morphine, indicative of a reduction in sensitivity. Moreover, we observed attenuation of appetitive CTR following repeated EtOH self-administration, indicating that nicotine pre-exposure did not solely impact aversive stimulus properties. Brief exposures to the taste of EtOH result in rapid, substantial increases in the palatability of EtOH (Loney and Meyer, 2018). Here, we show that nicotine pre-treatment significantly limits this increase in acceptance (Fig 6). If nicotine was increasing the reinforcing, or decreasing the aversive, properties of EtOH in a manner that impacted acquisition of CTR we should have observed a rightward shift in nicotine-treated rats during reassessment, relative to saline treatment. Rather, we found that acute nicotine administration reduced the increase in acceptance of the taste of EtOH, despite having no impact on the initial assessment of EtOH. These results further imply that nicotine was not necessarily impacting the quality of the experience of the drug but rather reducing its overall impact on CTR in both avoidance and appetitive paradigms. This is further supported by the finding that nicotine administration to rats already conditioned with EtOH (Switch Test; Fig 7) had no measurable impact on the evident rightward shift in acceptance of the taste of EtOH indicating that nicotine was the most impacting acquisition of conditioning and not expression.

The effect of nicotine to reduce the efficacy for EtOH to induce a CTA was also observed in female rats. Thus far, this phenomenon has only been reported in male rats. Again, there was no effect of nicotine on LiCl-induced CTA. Visual inspection of the data suggests that female rats receiving nicotine showed a greater reduction in acquisition and expression of EtOH-induced CTA, relative to male rats. Such a conclusion is in line with studies demonstrating increased sensitivity in female rats to the effects of intravenous nicotine (Chaudhri et al., 2005; Donny et al., 2000). Unfortunately, our study was not explicitly designed to examine potential sex differences in this effect of nicotine, but the present results call for future studies to sufficiently test for any potential sexual dimorphism with regards to this phenomenon.

There were no effects of either dose of nicotine on CTA induced by LiCl despite the consistent effects of nicotine across a wide range of drugs of abuse employed as. This finding was surprising given the low dose of LiCl (0.5 mEq/kg). We cannot entirely rule out that intensity differences between LiCl and the other tested drugs impacted the degree to which nicotine pre-treatment interfered with the acquisition of CTA. Yet, given that both 1.3 g/kg EtOH and 45 mg/kg morphine resulted in comparable CTAs relative to LiCl in saline pre-treated rats, and these doses of EtOH and morphine were impacted by nicotine pre-treatment while LiCl was not, such a conclusion seems unlikely. These results suggest that the attenuation induced by nicotine pretreatment is unique to commonly abused drugs. There are profound differences between CTA induced by drugs of abuse and LiCl. For example, LiCl produces changes in the innate oromotor and somatic responses generated by a taste conditioned stimulus (CS), while the responses conditioned by drugs of abuse generally do not affect these taste reactivity responses (Parker, 1995, 2003). These data provide further support that acquisition of CTA induced by drugs of abuse is qualitatively different from that induced by LiCl. Furthermore, this differentiation demonstrates that nicotine is not simply interfering with taste processes or the ability to learn CTR as rats were capable of acquiring and expressing functional CTAs when conditioned with LiCl and showed revaluation to a high dose of morphine. It is possible that this dissociation is driven by the common ability for these drugs of abuse to heighten dopaminergic activity (Hunt et al., 1985), a property not shared by LiCl, a compound with no known abuse potential in humans; LiCl appears to inhibit dopamine release (Fortin et al., 2016).

In summary, nicotine does not simply interfere with the ability to learn conditioned taste avoidance, or preference, given that conditioning with LiCl, the prototypical CTA US, was unaffected by pre-treatment with either dose of nicotine. Rather, the effects appear to be specific to drugs with known abuse potential in humans. Ultimately, the mechanisms of nicotine pre-exposure on CTR are beyond the scope of this parametric study, though there are a number of plausible mechanistic explanations for the observed phenomenon. For instance, nicotine could be reducing sensitivity to these stimulus properties of each of the tested drugs at their receptor subtypes critical for their ability to induce CTR (Tuesta et al., 2011) through either impacting the pharmacodynamics or kinetics of drug administration. Importantly, nicotine does not appear to impact the kinetics of morphine (McMillan and Tyndale, 2015) or cocaine (Kouri et al., 2001) and therefore increased metabolism is likely not responsible for the impact of nicotine on these two drugs; interactions between nicotine and ethanol kinetics are more equivocal (Hisaoka and Levy, 1985; Kouri et al., 2004; Schoedel and Tyndale, 2003; Yue et al., 2009). Altering any of these properties, even slightly, could significantly impact conditioning. Given the similarity of effects across multiple classes of drugs (morphine, cocaine, EtOH, and caffeine), similarity across both reinforcing and aversive drug qualities, and effects that were acute in nature, it seems more parsimonious that nicotine is acting more globally. For instance, because nicotine itself can increase brain dopamine levels, nicotine pre-treatment may be interfering with the efficacy of a given, subsequently presented, drug US to further increase dopamine release in a manner that may impact their ability to induce CTA, a mechanism that appears to be required for CTA induced by some drugs of abuse but not all (Hunt et al., 1985; Lin et al., 1994). It is important to note that blockade of dopaminergic receptors was shown to attenuate cocaine-induced CTA, for instance, but not block it as we have shown here with nicotine pre-treatment (Hunt et al., 1985) indicating that other mechanisms likely are also contributing to this effect of nicotine. Another potential mechanistic explanation is that the insular cortex (IC) may be disrupted by nicotine in these conditioning paradigms. Lesioning of the anterior IC, a structure heavily implicated in integration of interoceptive cues of stimuli, particularly drugs of abuse (Naqvi and Bechara, 2010) results in interference with the acquisition of CTA induced by drugs of abuse, but not LiCl, remarkably similar to the results observed here (Geddes et al., 2008; Mackey et al., 1986; Zito et al., 1988). Acquisition of LiCl-induced CTA is dependent on relatively more caudal areas of the IC (Schier et al., 2016; Schier et al., 2014). Nicotine administered to the anterior IC increases GABAergic tone and ultimately results in a depression of synaptic potentiation (Sato et al., 2017), primarily at layer 5-pyramidal neurons, the primary excitatory output of the IC. The present results could reasonably be due to the ability for nicotine to enhance long-term depression in the insular cortex. Silencing the insular cortex reduces the processing and integration of the interoceptive stimulus properties of many drugs of abuse (Geddes et al., 2008; Jaramillo et al., 2016; Li et al., 2013; Naqvi and Bechara, 2010; Paulus et al., 2013). It could be speculated that through decreasing activity of anterior IC neurons, nicotine may result in an inability for rats to update their behavior as a result of experiencing the interoceptive cues of drugs of abuse that serve to drive CTR. In support of such a conjecture, is the dependency of nicotine self-administration on the presence of externalized cues that are as equally necessary to maintain drug-taking behavior as the drug itself (Caggiula et al., 2001). Any unreliability in internal cues may further contribute to the ability for nicotine to potentiate the development of habitual drug taking that is resistant to reinforcer devaluation and omission (Clemens et al., 2014; Stringfield et al., 2018). Therefore, these data may reveal a more general tendency for nicotine to facilitate habitual, compulsive drug seeking/taking providing some rationale for the extreme comorbidity observed between nicotine use and illicit drug abuse.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Nicotine pre-treatment attenuated the avoidance induced by commonly abused drugs

Nicotine had no impact on avoidance induced by lithium chloride

Female rats appear to be more sensitive to these effects of nicotine

Nicotine reduced sensitivity to the CTR stimulus properties of these drugs

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Derek Daniels and Ann-Marie Torregrossa for the use of testing equipment. We also thank Ashton Earnhardt for her expert technical assistance.

Role of Funding Source

This work was funded by a grant from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA024112).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors Disclosures

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared.

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi: …

References

- Ackerman WE 3rd, 2012. The effect of cigarette smoking on hydrocodone efficacy in chronic pain patients. J. Ark. Med. Soc 109, 90–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackroff K, Sclafani A, 2003. Flavor preferences conditioned by intragastric ethanol with limited access training. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 75, 223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE, 1998. What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev 28, 309–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevins RA, Palmatier MI. Extending the role of associative learning processes in nicotine addiction. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev 2004. September;3 (3): 143-58. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski P, Piasecki J, Koros E, Stefanski R, Kostowski W, 1998. Studies on the role of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the discriminative and aversive stimulus properties of ethanol in the rat. Eur. J. Neuropsychopharmacol 8, 79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman NS, 1979. The role of blocking and compensatory conditioning in the treatment preexposure effect. Psychopharmacology 61, 177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA, Hoffman A, Perkins KA, Sved AF, 2001. Cue dependency of nicotine self-administration and smoking. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 70, 515–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Booth S, Gharib MA, Craven LA, Allen SS, Sved AF, erkins KA, 2005. Sex differences in the contribution of nicotine and nonpharmacological stimuli to nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology 180, 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens KJ, Castino MR, Cornish JL, Goodchild AK, Holmes NM, 2014. Behavioral and neural substrates of habit formation in rats intravenously self-administering nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 2584–2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Rowell PP, Gharib MA, Maldovan V, Booth S, Mielke MM, Hoffman A, McCallum S, 2000. Nicotine self-administration in rats: estrous cycle effects, sex differences and nicotinic receptor binding. Psychopharmacology 151, 392–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Akil H, Robinson TE, 2009. Individual differences in the attribution of incentive salience to reward-related cues: Implications for addiction. Neuropharmacology 56 Suppl 1, 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin SM, Chartoff EH, Roitman MF, 2016. The Aversive Agent Lithium Chloride Suppresses Phasic Dopamine Release Through Central GLP-1 Receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 41, 906–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J, Koelling RA, 1966. Relation of cue to consequence in avoidance learning. Science 185, 824–831. [Google Scholar]

- Geddes RI, Han L, Baldwin AE, Norgren R, Grigson PS, 2008. Gustatory insular cortex lesions disrupt drug-induced, but not lithium chloride-induced, suppression of conditioned stimulus intake. Behav. Neurosci 122, 1038–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigson PS, Freet CS, 2000. The suppressive effects of sucrose and cocaine, but not lithium chloride, are greater in Lewis than in Fischer rats: Evidence for the reward comparison hypothesis. Behav. Neurosci 114, 353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisaoka M, Levy G, 1985. Kinetics of drug action in disease states XI: effect of nicotine on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of phenobarbital and ethanol in rats. J. Pharm. Sci 74, 412–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt T, Switzman L, Amit Z, 1985. Involvement of dopamine in the aversive stimulus properties of cocaine in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 22, 945–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imperio CG, Grigson PS, 2015. Greater avoidance of a heroin-paired taste cue is associated with greater escalation of heroin self-administration in rats. Behav. Neurosci 129, 380–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo AA, Randall PA, Frisbee S, Besheer J, 2016. Modulation of sensitivity to alcohol by cortical and thalamic brain regions. Eur. J. Neurosci 44,2569–2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenney CB, Petko J, Ebersole B, Njatcha CV, Uzamere TO, Alexander DN, Grigson PS, Levenson R, 2016. Early avoidance of a heroin-paired taste-cue and subsequent addiction-like behavior in rats. Brain Res. Bull 123, 61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer SW, Bice PJ, Badia-Elder N, 1994. Alterations in taste reactivity to alcohol in rats given continuous alcohol access followed by abstinence. Alcohol. lin. Exp. es 18, 555–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohut SJ, 2017. Interactions between nicotine and drugs of abuse: a review of preclinical findings. Am J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 43, 155–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouri EM, Stull M, Lukas SE, 2001. Nicotine alters some of cocaine’s subjective effects in the absence of physiological or pharmacokinetic changes. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 69, 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouri EM, McCarthy EM, Faust AH, Lukas SE, 2004. Pretreatment with transdermal nicotine enhances some of ethanol’s acute effects in men. Drug Alcohol Depend 75, 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin D, Bloch RT, Smith BR, Amit Z, 2001. Caffeine, nicotine and mecamylamine share stimulus properties in the preexposure conditioned taste aversion procedure. Psychopharmacology 159, 70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin D, Smith BR, Amit Z, 1999. Nicotine and ethanol interaction on conditioned taste aversions induced by both drugs. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 62, 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CL, Zhu N, Meng XL, Li YH, Sui N, 2013. Effects of inactivating the agranular or granular insular cortex on the acquisition of the morphine-induced conditioned place Psychopharmacol 27, 837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HQ, Mcgregor IS, Atrens DM, Christie MJ, Jackson DM, 1994. Contrasting Effects of Dopaminergic Blockade on Mdma and D-Amphetamine Conditioned Taste-Aversions. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 47, 369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Showalter J, Grigson PS, 2009. Ethanol-induced conditioned taste avoidance: reward or aversion? Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 33, 522–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loney GC, Meyer PJ, 2018. Brief Exposures to the Taste of Ethanol (EtOH) and Quinine Promote Subsequent Acceptance of EtOH in a Paradigm that Minimizes Postingestive Consequences. Alcohol.Clin.Exp. Res 42, 589–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey WB, Keller J, van der Kooy D, 1986. Visceral cortex lesions block conditioned taste aversions induced by morphine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 24, 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matta SG, Balfour DJ, Benowitz NL, Boyd RT, Buccafusco JJ, Caggiula AR, Craig CR, Collins AC, Damaj MI, Donny EC, Gardiner PS, Grady SR, Heberlein U, Leonard SS, Levin ED, Lukas RJ, Markou A, Marks MJ, McCallum SE, Parameswaran N, Perkins KA, Picciotto MR, Quik M, Rose JE, Rothenfluh A, Schafer WR, Stolerman IP, Tyndale RF, Wehner JM, Zirger JM, 2007. Guidelines on nicotine dose selection for in vivo research. Psychopharmacology 190, 269–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DM, Tyndale RF, 2015. Nicotine increases codeine analgesia through the induction of brain CYP2D and central activation of codeine to morphine. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 1804–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi NH, Bechara A, 2010. The insula and drug addiction: an interoceptive view of pleasure, urges, and decision-making. Brain Struct. Funct 214,435–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnink M, Davenport RA, Ortega B, Houpt TA, 2007. D-Cycloserine enhances conditioned taste aversion learning in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 87, 321–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LA, 1995. Rewarding drugs produce taste avoidance, but not taste aversion. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 19, 143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LA, 2003. Taste avoidance and taste aversion: evidence for two different processes. Learn. Behav 31, 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus MP, Stewart JL, Haase L, 2013. Treatment approaches for interoceptive dysfunctions in drug addiction. Front. Psychiatry 4, 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, D’Amico D,Sanders M, Grobe JE, Wilson A, Stiller RL, 1996. Influence of training dose on nicotine discrimination in humans. Psychopharmacology 126, 132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu YM, Liu YT, Li ST., 2011. Tramadol requirements may need to be increased for the perioperative management of pain in smokers. Med. Hypotheses 77, 1071–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin BM, Hunt WA, Lee J, 1987. Taste-aversion learning produced by combined treatment with subthreshold radiation and lithium-chloride. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 27, 671–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinker JA, Hutchison MA, Chen SA, Thorsell A, Heilig M, Riley AL, 2011. Exposure to nicotine during periadolescence or early adulthood alters aversive and physiological effects induced by ethanol. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 99, 7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MJ, Anselme P, Suchomel K, Berridge KC, 2015. Amphetamine-induced sensitization and reward uncertainty similarly enhance incentive salience for conditioned cues. Behav. Neurosci 129, 502–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Kawano T, Yin DX, Kato T, Toyoda H, 2017. Nicotinic activity depresses synaptic potentiation in layer V pyramidal neurons of mouse insular cortex. Neuroscience 358,13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schier LA, Blonde GD, Spector AC, 2016. Bilateral lesions in a specific subregion of posterior insular cortex impair conditioned taste aversion expression in rats. J. Comp. Neurol 524, 54–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schier LA, Hashimoto K, Bales MB, Blonde GD, Spector AC, 2014. High-resolution lesion-mapping strategy links a hot spot in rat insular cortex with impaired expression of taste aversion learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 111, 1162–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoedel KA, Tyndale RF, 2003. Induction of nicotine-metabolizing CYP2B1 by ethanol and ethanol-metabolizing CYP2E1 by nicotine: summary and implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1619, 283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafine KM, Riley AL, 2010. Preexposure to cocaine attenuates aversions induced by both cocaine and fluoxetine: Implications for the basis of cocaine-induced conditioned taste aversions. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 95, 230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GW, Farrell M, Bunting B, Houston JE, Shevlin M, 2011. Patterns of polydrug use in Great Britain: findings from a national household population survey. Drug Alcohol Depend 113, 222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmiller CL, Diederichs C, Roehrs TA, Hyde-Nolan M, Roth T, Greenwald MK, 2012. Postsurgical patient-controlled opioid self-administration is greater in hospitalized abstinent smokers than nonsmokers. J. Opioid. Manag 8, 227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringfield SJ, Boettiger CA, Robinson DL, 2018. Nicotine-enhanced Pavlovian conditioned approach is resistant to omission of expected outcome. Behav. Brain. Res 343, 16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Switzman L, Fishman B, Amit Z, 1981. Pre-exposure effects of morphine, diazepam and delta 9-THC on the formation of conditioned taste aversions. Psychopharmacology 74, 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenk CM, Kavaliers M, Ossenkopp KP, 2005. Dose response effects of lithium chloride on conditioned place aversions and locomotor activity in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol 515, 117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenk CM, Kavaliers M, Ossenkopp KP, 2006. The effects of acute corticosterone on lithium chloride-induced conditioned place aversion and locomotor activity in rats. Life ci 79, 1069–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR 2nd, Craig EM, 2015Configurations of the interoceptive discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol and nicotine with two different exteroceptive contexts in rats: Extinction and recovery. Behav. Process 115, 169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR 2nd 2ndDooley TF 2nd Craig EM, 2013. The discriminative stimulus effects of a nicotine-ethanol compound in rats: Extinction with the parts differs from the whole. Behav. Neurosci 127, 899–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuesta LM, Fowler CD, Kenny PJ, 2011. Recent advances in understanding nicotinic receptor signaling mechanisms that regulate drug self-administration behavior. Biochem. Pharmacol 82, 984–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner JM, Acerbo MJ, Jones SA, Robinson TE, 2006. The attribution of incentive salience to a stimulus that signals an intravenous injection of cocaine. Behav. Brain Res 169, 320–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J, Khokhar J, Miksys S, Tyndale RF, 2009. Differential induction of ethanol-metabolizing CYP2E1 and nicotine-metabolizing CYP2B1/2 in rat liver by chronic nicotine treatment and voluntary ethanol intake. Eur. J. Pharmacol 609, 88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrindast MR, Faraji N, Rostami P, Sahraei H, Ghoshouni H, 2003. Cross-tolerance between morphine- and nicotine-induced conditioned place preference in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 74, 363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zito KA, Bechara A, Greenwood C, van der Kooy D, 1988. The dopamine innervation of the Visceral cortex mediates the aversive effects of opiates. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 30, 693–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.