Abstract

Objectives:

Use the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to describe the context in which a gestational weight gain (GWG) intervention, embedded within Parents as Teachers (PAT), will be implemented at PAT sites nationwide.

Methods:

Ten site leaders and six parent educators from ten PAT sites in eight states participated in semi-structured interviews and a survey. Audio-recordings and systematic notes were used in a deductive analysis. Scales were descriptively analyzed.

Results:

Surveys demonstrated positive perspectives of PAT+GWG. In interviews, participants described PAT+GWG filling a need for prenatal health education and confidence delivering this content, valued integration of PAT+GWG within the PAT curriculum, and recommended materials to meet their clients’ needs.

Conclusions:

Contextual information can help maximize PAT+GWG’s impact.

Keywords: Implementation, Lifestyle change, Gestational weight gain

Obesity and diabetes are major public health problems worldwide, and are related to serious medical complications for women and their offspring. Among women who gave birth in 2014, 50% were overweight or obese before becoming pregnant, heightening the risk for poor immediate and long-term health outcomes.1 Recognizing the medical significance of obesity management during pregnancy on maternal and child outcomes, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) revised its gestational weight gain (GWG) guidelines to provide optimal GWG ranges based on a woman’s pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI).2 However, women with overweight or obesity are more likely to gain more weight than is recommended during pregnancy compared to women who start their pregnancy at a healthy weight,3 putting them at increased risk for maternal and child morbidity and mortality including miscarriage, congenital malformations, gestational diabetes mellitus, macrosomia, preeclampsia, preterm birth, stillbirth, cesarean delivery, and neonatal death.4–15 Women who gain excess weight in pregnancy retain more post-partum weight, affecting their own health (eg, their future risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes); this increases the risks related to obesity in future pregnancies.16,17 This recurring cycle of maternal and offspring obesity and metabolic disease is a significant public health 18 and national economic concern as the health care costs of managing these conditions are rapidly escalating.19

Data from several recent studies and conclusions from review articles 20–33 underscore the importance of dietary modification and encouraging an increase in physical activity for encouraging appropriate GWG among women with overweight and obesity. Several core elements have been identified to help achieve appropriate GWG in pregnant women including diet and physical activity, behavioral approaches (eg goal setting, self-monitoring), skill development (eg portion size, label reading), psychosocial support (eg social support) and structured contact (eg dose, contact intensity).34–41 A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce GWG by Yeo et al. found a reduction in GWG of 1.8 pounds among interventions delivered by non-clinical providers.42 However, gaps exist in translating research to practice and in reaching high-risk women.

To address these gaps,43 we partnered with Parents as Teachers (PAT), a national home visiting, community based organization. Together, we developed a lifestyle intervention (PAT+GWG) focused on promoting appropriate GWG.44 PAT provides parent-child education and services free-of-charge to high-risk families, through up to 25 home visits per year that begin prenatally and continue until the child enters kindergarten.45 Of the parents PAT serves 51% are high needs defined by factors such as: low educational attainment, low income, parent or child with disabilities/chronic health condition, recent immigrant family, parent with mental illness, or un-stable housing,45 and, in 2015, served 20,889 pregnant women.45 The reach of PAT is quite large and diverse as it serves more than 195,000 children in 50 states across the United States as well as more than 100 Tribal organizations, schools and communities. PAT also serves families in five other countries and one U.S. territory.46 PAT+GWG was embedded within the existing prenatal home visits offered by PAT (without additional visits). In an efficacy test, PAT+GWG significantly reduced excessive GWG of low-income Black women with overweight and obesity.43,44 In the controlled setting of this efficacy trial, the parent educators were hired, trained, and supervised by the research team. To our knowledge, only one other study has attempted to integrate an intervention to promote appropriate GWG into PAT, but included only a small sample.47 Implementation of PAT+GWG across PAT’s national network provides an opportunity to reach and benefit thousands of women and their offspring.

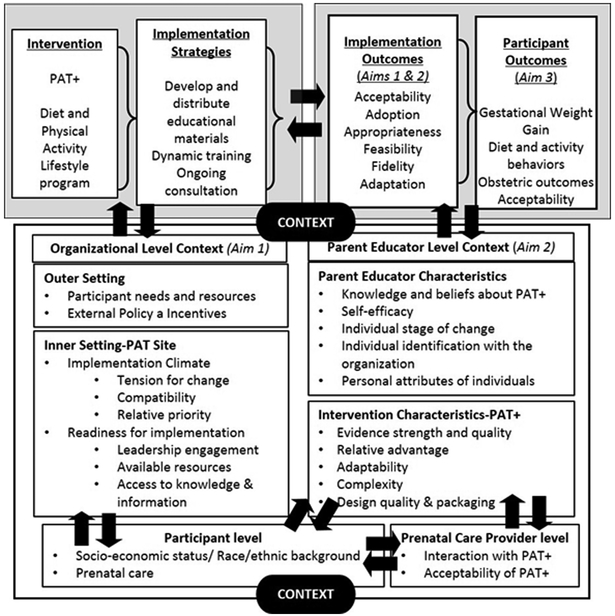

Dissemination and implementation science provides a useful guide for understanding (Figure 1) the successful translation of the evidence-based PAT+GWG program to practice, such that it can reach families across the country.48 This encourages consideration of the ultimate outcome (ie, participant outcomes as GWG and obstetric outcomes), but recognizes that important implementation outcomes (eg, acceptability, adoption, fidelity) must be achieved at the organizational level for families to receive PAT+GWG,49 and describes how implementation strategies (eg, ongoing consultation) can help this occur.50 Dissemination and implementation science goes further to explain the importance of context and the many levels of context that can be important (eg, the PAT site level, the parent educator level).49,51

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model for PAT+GWG Intervention and Implementation.

Formative work in real-world settings can help prevent difficulties with implementation, once an intervention is deployed within an organization, and can help determine how PAT site leaders and parent educators feel about delivering PAT. One model from dissemination and implementation science that can be useful in guiding collection of appropriate contextual factors that might impact implementation is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).51,52 CFIR was selected, as this model offers a menu of constructs that can guide preparation for implementation through a systematic assessment of the implementation context, such as potential barriers and facilitators. These constructs are drawn from a wide ranging evidence base,53,54 and have been associated with effective implementation.51,52 Using a determinate framework such as CFIR to guide formative research is beneficial, as it can help identify factors (eg, barriers and facilitators) that might impact implementation success.55 Therefore, the purpose of the current paper is to describe the context for implementation, as guided by the CFIR, for PAT+GWG at PAT sites across the United States to identify factors (eg, barriers and facilitators) that might impact implementation success of this type of intervention within a national organization.

METHODS

Participants

We recruited PAT sites from a list of 46 sites offering prenatal programs provided by PAT National Center; there were no additional inclusion criteria. Initial contact was made with the site leader (the individuals in this position had a variety of titles - eg, managers, supervisors – across PAT sites, so we refer to them collectively as site leaders). If s/he agreed to participate, he/she was interviewed. After the interview, the site leader provided the names of several parent educators from his/her PAT site, who were recruited to participate. We conducted data collection with site leaders and parent educators to get perspectives within both levels of each organization. The study protocol was approved by the Human Research Protection Office at BLINDED. All participants provided verbal consent before beginning the interview, and were compensated with a $20 gift card for their time.

Description of PAT+GWT

The PAT+GWG intervention is guided by the PAT strength-based, solution-focused model and a socio-ecologic approach which recognizes the protective and interactive influences on pregnant women across multiple levels.56,57. Objectives include skill building and strategies to address: reduction of high-sugar beverages, substituting healthy for unhealthy foods, portion control, regular eating patterns, and breastfeeding barriers and strategies. Physical activity goals encourage a total of 150 minutes (2.5 hours) of moderate-intensity exercise (eg, brisk walking) and/or lifestyle activity per week.

Interview data collection and analysis

Two trained members of the research team (RGT, CS) conducted interviews by phone, between August 2016 and September 2016, using a semi-structured interview guide (example questions and responses are provided in Table 1). The interview guide was developed using the “Interview Guide Tool” of the CFIR website and then adapted to fit PAT and the PAT+GWG intervention.51,52

Table 1.

Summary of Data Collection Guided by Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)

| Contextual Factor | Definition | Sample Item | Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Characteristics – PAT+GWG | |||

| Evidence Strength & Quality | Perceptions of the quality and validity of evidence supporting belief PAT+GWG will have desired outcomes | Should be effective, based on current scientific knowledge. | Rogers, 200353a alpha=0.93 range: 1-5 2 items |

| Relative Advantage | Parent educators’ perception of the advantage of implementing PAT+GWG versus usual care | In general, the PAT+GWG curriculum would be more effective in helping women gain a healthy amount of weight during pregnancy than our current curriculum. | Rogers, 200353a alpha=0.92 range: 1-5 4 items Panzano, 201259b alpha=0.95 range: 1-7 6 items Interview |

| Adaptability | Degree to which PAT+GWG can be adapted, tailored, refined, or reinvented to meet local need | What kinds of changes or alterations do you think you will need to make to PAT+GWG so it will work effectively at your site? | Interview |

| Complexity | Perceived difficulty of implementation, reflected by duration, scope, radicalness, disruptiveness, centrality, and intricacy and number of steps required to implement | The PAT+GWG curriculum would be difficult to teach. | Rogers, 200353a alpha=0.87 range: 1-5 3 items Pankratz, 200258c alpha=0.76 range: 1-5 4 items Panzano, 201259b alpha=0.94 range: 1-7 10 items Interview |

| Design Quality & Packaging | Perceived excellence in how PAT+GWG is bundled, presented, and assembled | What supports, such as online resources, marketing materials, or a toolkit, would help you implement and use PAT+GWG? | Interview |

| Outer Setting | |||

| Participant needs and resources | Extent to which client needs, and barriers and facilitators to meet those needs, are accurately known and prioritized by the organization | PAT+GWG will improve the overall quality of life for clients who receive it. | Interview |

| External policy and incentives | External strategies to spread interventions, including policy and regulations, external mandates, recommendations and guidelines | Do you anticipate any funding changes in the next few years? | Interview |

| Inner Setting – PAT Site | |||

| Implementation Climate | Absorptive capacity for change, shared receptivity of involved individuals to PAT+GWG, and the extent to which use of PAT+GWG will be rewarded, supported, and expected within the PAT site | Staff members involved in implementing PAT+GWG are appreciated for their efforts. | Panzano, 201259b alpha=0.89 range: 1-7 11 items Interview |

| Tension for Change | Degree to which stakeholders perceive the current situation as needing change. | Is there a strong need for PAT+GWG? | Interview |

| Compatibility | The degree of tangible fit between meaning and values attached to PAT+GWG, how those align with norms, values, and perceived risks and needs, and how PAT+GWG fits with existing workflows and systems | I think that using PAT+GWG fits well with the way I like to work | Pankratz, 200258c alpha=0.62 range: 1-5 8 items Panzano, 201259b alpha=0.79 range: 1-77 4 items Interview |

| Relative Priority | Individuals’ shared perception of the importance of the implementation within PAT. | I don’t know why promoting healthy GWG is so important for PAT to address | Steckler, 199260d alpha=0.54 range: 1-4 4 items Interview |

| Readiness for Implementation | Tangible and immediate indicators of organizational commitment to its decision to implement an intervention | People who work here are determined to implement this change. | Panzano, 201259b alpha=0.91 range: 1-7 4 items |

| Leadership Engagement | Commitment, involvement, and accountability of leaders and managers with the implementation. | Arose out of interviews | Interview |

| Available Resources | Level of resources dedicated for implementation and on-going operations, including money, training, and time. | What resources are you counting on to implement and administer PAT+GWG? | Interview |

| Access to Knowledge & Information | Ease of access to digestible information and knowledge about PAT+GWG and how to incorporate it into work tasks. | I am aware of curricula which address healthy GWG. | Steckler, 199260d alpha=0.83 range: 1-4 4 items |

| Characteristics of Individuals (PAT site leaders and parent educators) | |||

| Knowledge & Beliefs about PAT+GWG | Individual’s attitudes toward and value placed on PAT+GWG and familiarity with facts, truths, and principles related to PAT+GWG | If you received training in a therapy or intervention that was new to you, how likely would you be to adopt it if: it “made sense” to you? | Aarons, 200461e alpha=0.85 range: 1-5 4 items Interview |

| Self-efficacy | Individual’s belief in his/her own capabilities to execute courses of action to achieve implementation goals | I am confident that I can implement PAT+GWG as prescribed at this PAT site. | Interview |

| Individual Stage of Change | Characterization of the phase an individual is in, as s/he progresses toward skilled, enthusiastic, and sustained use of PAT+GWG | I would like to explore the possibility of improving GWG in my PAT site. | Steckler, 199260d alpha=0.88 range: 1-4 4 items |

| Individual Identification with Organization | How individuals perceive PAT, and their relationship and degree of commitment with that PAT. | If you received training in PAT+GWG, how likely would you be to adopt it if it was required by your supervisor? | Aarons, 200461e alpha=0.98 range: 1-5 3 items Interview |

| Personal Attributes of Individuals (Openness) | Extent to which the individual is generally open to trying new interventions | I like to use new types of therapy/ interventions to help my clients | Aarons, 200461e alpha=0.89 range: 1-5 4 items |

| Personal Attributes of Individuals (Divergence) | Extent to which the provider perceives research-based interventions as not clinically useful and less important than clinical experience | Experience working in the field is more important than using manualized therapy/ interventions. | Aarons, 200461e alpha=0.53 range: 1-5 4 items |

Strongly disagree (1) to Strongly agree (5);

Strongly disagree (1) to Strongly agree (7);

Strongly disagree (1) to Strongly agree (5);

Not at all (1) to Very true (4);

Not at all (1) to To a very great extent (5)

Interviews were audio-recorded and systematic notes were taken. Notes were managed using Nvivo10. Deductive analysis, beginning with the interview guide and the CFIR was conducted using the Nvivo analysis template downloaded from the CFIR website.51,52 While CFIR is not a theory, the deductive analysis was guided by this framework. Themes articulated by study participants were summarized.

Survey data collection and analysis

After their interview, participants were sent a link to complete an online survey assessing several CFIR constructs. Definitions, sample items, number of items, and the possible range of the scale for each construct are available in Table 1. From the Intervention Characteristics domain, the constructs assessed were: Evidence Strength & Quality,53 Relative Advantage,53,58,59 and Complexity;53,58,59 and from the Inner setting domain Implementation Climate,59 Compatibility,58,59 Relative Priority,60 Readiness for Implementation,59 and Access to Knowledge & Information,60 were measured. Knowledge & Beliefs about the Intervention,61 Individual Stage of Change,60 Individual Identification with Organization,61 and Personal Attributes of Individuals (Openness and Divergence)61 were measured from the Characteristics of Individuals domain. Outer setting and Process domains were not assessed in the online survey.

Scales were analyzed as continuous variables; due to the small sample size, analyses were limited to description of the scales (ie, means and standard deviations). Internal consistency of the scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. Though there were no significant differences between scale scores between PAT site leaders and parent educators, using 2-tailed independent samples t-tests, for descriptive purposes, the scales are presented for the total sample and each group separately.

RESULTS

From the ten PAT sites recruited to the study, ten site leaders and six parent educators participated in qualitative interviews (total N=16); 13 of these (8 site leaders, 5 parent educators) completed the survey. These sites were spread across eight states. All participants had at least a bachelor’s degree. Site leaders had been with PAT for between 2 and 23 years, and parent educators had been with PAT for 1 year to 7 years. All of the parent educators were employed with the site full time.

Survey and interview results are summarized within the context of the CFIR in Table 2. Cronbach’s alphas for six scales were greater than .9, six were greater than 0.8, two were greater than 0.7, and the remaining 3 were less than 0.7. The survey data demonstrate positive perspectives of PAT+GWG for all metrics, with mean scores for participants in the positive end of the possible range for each scale. For example, the ‘implementation climate’ scale, based on the measure used by Panzano et al.59, had a mean of 5.75 and a standard deviation (SD) of 0.87. On an example item from this scale ‘Staff members involved in implementing PAT+ will be appreciated for their efforts,’ two responded ‘neither agree nor disagree’, but the other ten respondents either agreed or strongly agree; this indicates PAT staff fell the climate into which PAT+GWG will be implemented will be positive, supporting the intervention. Also in the inner setting, compatibility had a mean of 6.08 (SD=0.87), and relative priority had a mean 1.15 (SD=0.29). From the intervention characteristics domain, complexity had a mean of 2.38 (SD=0.77) .

Table 2.

Description of the Context for Implementation Guided by Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)

| Contextual Factor | Measure | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Characteristics – PAT+GWG | Group | n | Mean (SD) | |

| Evidence Strength & Quality | Rodgers 200353a | Total | 13 | 2.77 (0.70) |

| PE | 5 | 2.80 (0.76) | ||

| SL | 8 | 2.75 (0.71) | ||

| Relative Advantage | Rodgers 200353a | Total | 13 | 3.73 (0.63) |

| PE | 5 | 3.90 (0.74) | ||

| SL | 8 | 3.63 (0.58) | ||

| Panzano 201259b | Total | 9 | 6.04 (0.98) | |

| PE | 5 | 5.80 (1.17) | ||

| SL | 4 | 6.33 (0.72) | ||

| Interview | • Current healthy weight info for pregnant women would be enhancement, look for outside resources or refer | |||

| Adaptability | Interview | • Would need training | ||

| • Flexibility to make PAT+GWG relevant | ||||

| • Some educators felt overwhelmed and concerned PAT+GWG might add too much | ||||

| Complexity | Rodgers 200353a | Total | 13 | 2.38 (0.77) |

| PE | 5 | 2.53 (0.80) | ||

| SL | 8 | 2.29 (0.79) | ||

| Pankratz 200258c | Total | 13 | 2.63 (0.86) | |

| PE | 5 | 2.60 (0.98) | ||

| SL | 8 | 2.66 (0.84) | ||

| Panzano 201259b | Total | 6 | 5.28 (1.19) | |

| PE | 3 | 4.70 (1.54) | ||

| SL | 3 | 5.87 (0.40) | ||

| Interview | • Concern about time required for data collection (visit documentation) | |||

| • Two educators mentioned that non-high needs families might not qualify for that many prenatal visits. | ||||

| • Concern if mother has other kids, does not engage in visit, or does not think her weight is an issue | ||||

| Design Quality & Packaging | Interview | • Preferred online, checklist format for documentation | ||

| • Training could be virtual (with video) so travel would not be necessary | ||||

| Outer Setting | ||||

| Participant needs and resources | Interview | • Weight/nutrition issues for some PAT clients; many want this info, but concern some may be uncomfortable. | ||

| • Need low-literacy and Spanish materials | ||||

| External policy and incentives | Interview | • Funders would be supportive | ||

| • Concern funding may not be renewed | ||||

| • One site leader mentioned tension with physicians not wanting educators to discuss health | ||||

| Inner Setting – PAT Site | ||||

| Implementation Climate | Panzano 201259b | Total | 7 | 5.75 (0.87) |

| PE | 3 | 5.30 (1.09) | ||

| SL | 4 | 6.09 (0.61) | ||

| Interview | • One site leader expressed concern about possible changes in funding, might change visit structure, add stress, and make implementation difficult | |||

| Tension for Change | Interview | • Parent educators have limited resources in general, and specifically on healthy weight, for prenatal families | ||

| Compatibility | Pankratz 200258c | Total | 13 | 3.35 (0.49) |

| PE | 5 | 3.13 (0.57) | ||

| SL | 8 | 3.48 (0.41) | ||

| Panzano 201259b | Total | 9 | 6.08 (0.87) | |

| PE | 5 | 6.00 (1.09) | ||

| SL | 4 | 6.19 (0.63) | ||

| Interview | • Appealing that PAT+GWG fits within visit structure and within normal visit (eg, Family Wellbeing), but non-high needs families might be eligible for fewer visits | |||

| Relative Priority | Steckler 199260d | Total | 12 | 1.15 (0.29) |

| PE | 5 | 1.30 (0.41) | ||

| SL | 7 | 1.04 (0.09) | ||

| Interview | • Important issue for families and fits with family wellbeing | |||

| • Two educators concerned healthy weight might not be most important issue | ||||

| Readiness for Implementation | Panzano 201259b | Total | 7 | 5.89 (0.89) |

| PE | 3 | 5.25 (1.00) | ||

| SL | 4 | 6.38 (0.43) | ||

| Leadership Engagement | Interview | • Site leaders and parent educators felt it would be implemented if supervisors decided to do so. | ||

| • Site leaders would remind parent educators to complete paperwork | ||||

| Available Resources | Interview | • Participants requested: training, recruitment materials (eg, flyers and pamphlets), education materials and incentives for families, ways to incorporate dads and other children, and materials in Spanish. | ||

| Access to Knowledge & Information | Steckler 199260d | Total | 13 | 2.54 (0.82) |

| PE | 5 | 2.45 (0.67) | ||

| SL | 8 | 2.59 (0.94) | ||

| Characteristics of Individuals (PAT site leaders and parent educators) | ||||

| Knowledge & Beliefs about PAT+GWG | Aarons 200461e | Total | 12 | 4.02 (0.79) |

| PE | 5 | 3.70 (1.14) | ||

| SL | 7 | 4.25 (0.38) | ||

| Interview | • Participants believe healthy weight gain is important for their clients, but worry some educators and some families may not share belief | |||

| Self-efficacy | Interview | • Confidence in delivering PAT+GWG; many already deliver health information | ||

| Individual Stage of Change | Steckler 199260d | Total | 13 | 3.33 (0.73) |

| PE | 5 | 3.10 (1.08) | ||

| SL | 8 | 3.47 (0.43) | ||

| Individual Identification with Organization | Aarons 200461e | Total | 13 | 4.36 (1.01) |

| PE | 5 | 3.73 (1.42) | ||

| SL | 8 | 4.75 (0.39) | ||

| Interview | • One parent educator described not personally being excited to deliver PAT+GWG, but thought it would benefit the site. | |||

| Personal Attributes of Individuals (Openness) | Aarons 200461e | Total | 12 | 3.92 (0.60) |

| PE | 5 | 3.80 (0.93) | ||

| SL | 7 | 4.00 (0.25) | ||

| Personal Attributes of Individuals (Divergence) | Aarons 200461e | Total | 12 | 1.98 (0.58) |

| PE | 5 | 2.00 (0.66) | ||

| SL | 7 | 1.96 (0.57) | ||

Strongly disagree (1) to Strongly agree (5);

Strongly disagree (1) to Strongly agree (7);

Strongly disagree (1) to Strongly agree (5);

Not at all (1) to Very true (4);

Not at all (1) to To a very great extent (5)

As shown in Table 2, in the interview findings, participants expressed the importance of PAT+GWG to fill a need for health education in the prenatal period. Currently, parent educators described searching outside PAT, for example to March of Dimes, to find information to add or referring women to other programs to fill this gap. PAT site leaders and parent educators reported they were confident they could deliver this information and that it is information families want to learn. Additionally, the integration of PAT+GWG within the PAT curriculum, and the potential to add health content within existing parts of the visit (ie, family wellbeing) was particularly important. This is important as there was some concern expressed among educators about being overwhelmed, so adding content outside of the existing visit structure would be a challenge. Usual care PAT offers parent educators the flexibility to tailor the program to the families they serve, so it was also necessary to those interviewed that PAT+GWG was also designed with this flexibility.

Participants had useful suggestions to inform PAT+GWG implementation including providing additional training specific to using PAT+GWG, with a preference for training delivered virtually, to avoid travel (Table 2). One particular issue for training was the concern that some educators and some clients might not be interested in this type of information such that all or parts of PAT+GWG may not be implemented with fidelity, so it is important that training address this barrier. Participants were also concerned about implementing PAT+GWG for families with multiple children, and suggested the program be able to accommodate these families so that other children in the home might be able to participate along with the pregnant mother (eg, incorporating activities appropriate for a pregnant mother and other young children). In the efficacy trial for PAT+GWG, all women qualified as high needs, and were thus able to receive ten prenatal home visits. However, some participants were concerned that if PAT+GWG is implemented throughout PAT, it may be more difficult to achieve ten home visits for families not considered high needs.45 Though not related to the PAT+GWG intervention directly, the issue that most concerned participants was the documentation that would be required as part of a research study. Parent educators have large documentation requirements through several different online systems (different sites described different systems). For sustainability, PAT+GWG documentation could be incorporated into PAT’s existing, electronic documentation systems. Finally, participants requested PAT+GWG promotional materials to recruit families such as flyers as well as education materials to meet the needs of their clients (eg, highly visual, low literacy, available in Spanish).

DISCUSSION

We found support for PAT+GWG among PAT site leaders and parent educators, who felt this curriculum would fill an important need in their work with prenatal clients. The CFIR model provided a useful structure in which to place the participants’ perspectives related to PAT+GWG, the inner and outer intervention setting, and the characteristics of those who will deliver PAT+GWG. Despite their self-efficacy to deliver PAT+GWG, participants also emphasized the importance of training, particularly in terms of addressing barriers among parent educators and clients that may have less interest in healthy weight; this was a part of the parent educator training for the efficacy trial. This is reflected in the quantitative scales, which found that participants rated PAT+GWG’s complexity higher and relative priority lower than have been seen with other interventions using these measures.60,62,63 While participants voiced some concerns, such as with visit tracking, they also provided feasible suggestions for how to address these issues.

These findings are particularly important given the barriers clinical providers (eg obstetricians) face providing specific and actionable information related to healthy weight gain.64–66 There is often limited time during visits for providers to offer women detailed dietary or physical activity recommendations and strategies for behavior change.64,66 Despite pregnant women reporting that weight and weight gain during pregnancy are important to them, there is evidence that they are not satisfied with the information provided by their clinical provider, in part related to time constraints.67–69 There are also challenges to implement such programs in health departments.70 The ability of a community-based provider, who works with a woman in her home environment and with whom she has a strong, long-term relationship, provides an additional channel for such intervention. Providers may feel more comfortable with community-based providers delivering this information if they are appropriately trained.

An important feature of PAT+GWG is its integration into an existing community-based organization that serves families across the United States through reimbursable home visits. Though low risk families may not qualify for as many visits, they may be able to succeed with fewer visits. High needs families, who have higher weight gain during pregnancy,71–73 qualify for more home visits.45,74 This structure is important as it allows for sustainable translation of the evidence-based PAT+GWG intervention into practice.75–79 The interview and survey findings indicate important perspectives related to the intervention (eg, PAT+GWG fills a gap in healthy weight curricula for pregnant clients) and inner setting (eg, PAT+GWG fits within the visit structure) that facilitate this implementation. For example, the measures of implementation climate, both in the inner setting domain of the CFIR, had higher scores than those seen elsewhere in studies that have used these measures.59,62 This enhances potential impact and addresses major barriers to reach and maintenance, which often plague interventions developed within academic constraints.80–83 Future studies should look at how these perspectives compare with those of pregnant women who might be participants in PAT+GWG.

This study has limitations worth discussing. The sample size was small, including only ten PAT site leaders and six parent educators. The small sample size does limit the survey results to descriptive, but these are informative in demonstrating the perspectives of this sample about PAT+GWG, as the measures were drawn from existing surveys. Though the sample size was small, participants were diverse in their location, representing ten sites in eight states, suggesting some generalizability. The current study included only PAT staff; future investigations could investigate the perspectives of pregnant women as well as clinical providers.

Conclusion

Overall, these findings indicate that a community-based home visiting organization can be an important channel to disseminate PAT+GWG, an evidence-based intervention to promote appropriate GWG. Important considerations, voiced by PAT site leaders and parent educators, such as adequate training and materials in Spanish, should be incorporated into PAT+GWG to enhance the likelihood of successful implementation. Integration into PAT allows PAT+GWG to have high reach and sustainability, for maximum impact. These factors are of practical importance to those aiming to embed evidence-based interventions into practice settings to achieve national reach.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH BEHAVIOR

This investigation is useful both in understanding the implementation of an evidence-based intervention to promote healthy GWG as well as the usefulness of frameworks from implementation science, such as the CFIR, in helping to explore these factors in advance of program implementation on a large scale.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the substantive contributions of The Parents as Teachers National Center. This project was supported by Washington University’s Institute for Public Health’s Center for Dissemination and Implementation Pilot Program. This study was also supported in part by The NIDDK Center for Diabetes Translation Research (P30DK092950). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH. The funding sources had no involvement in the conduct of the research and preparation of the article.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Approval Statement

This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University in St. Louis (IRB# 201606107).

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Contributor Information

Rachel G. Tabak, The Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, 1 Brookings Dr, St. Louis, MO, 63130, USA, phone: 314-935-0153, Fax: 314-935-0150, rtabak@wustl.edu.

Cynthia D. Schwarz, The Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, 1 Brookings Dr, St. Louis, MO, 63130, USA, phone: 314-935-3063, Fax: 314-935-0150, cschwarz@wustl.edu.

Ebony Carter, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Washington University in St. Louis, 660 S. Euclid Ave., CB8064, St. Louis, MO, 63110, USA, phone: 314-362-8280, Fax: 314-935-0150, ebcarter@wustl.edu.

Debra Haire-Joshu, The Brown School and The School of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis, 1 Brookings Dr, St. Louis, MO, 63130, USA, phone: 314-935-3963, Fax: 314-935-0150, djoshu@wustl.edu.

References

- 1.Branum AM, Kirmeyer SE, Gregory EC. Prepregnancy Body Mass Index by Maternal Characteristics and State: Data From the Birth Certificate, 2014. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. August 2016;65(6):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasmussen KM, Catalano PM, Yaktine AL. New guidelines for weight gain during pregnancy: what obstetrician/gynecologists should know. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. December 2009;21(6):521–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Restall A, Taylor RS, Thompson JM, et al. Risk factors for excessive gestational weight gain in a healthy, nulliparous cohort. J Obes. 2014;2014:148391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietz PM, Callaghan WM, Cogswell ME, Morrow B, Ferre C, Schieve LA. Combined effects of prepregnancy body mass index and weight gain during pregnancy on the risk of preterm delivery. Epidemiology. March 2006;17(2):170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty DA, Magann EF, Francis J, Morrison JC, Newnham JP. Pre-pregnancy body mass index and pregnancy outcomes. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. December 2006;95(3):242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lashen H, Fear K, Sturdee DW. Obesity is associated with increased risk of first trimester and recurrent miscarriage: matched case-control study. Hum. Reprod July 2004;19(7):1644–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodnar LM, Catov JM, Klebanoff MA, Ness RB, Roberts JM. Prepregnancy body mass index and the occurrence of severe hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Epidemiology. March 2007;18(2):234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludwig DS, Currie J. The association between pregnancy weight gain and birthweight: a within-family comparison. Lancet. September 18 2010;376(9745):984–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu SY, Kim SY, Lau J, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of stillbirth: a metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. September 2007;197(3):223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmussen SA, Chu SY, Kim SY, Schmid CH, Lau J. Maternal obesity and risk of neural tube defects: a metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. June 2008;198(6):611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Chaar D, Finkelstein SA, Tu X, et al. The impact of increasing obesity class on obstetrical outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. March 2013;35(3):224–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rankin J, Tennant PW, Stothard KJ, Bythell M, Summerbell CD, Bell R. Maternal body mass index and congenital anomaly risk: a cohort study. Int J Obes (Lond). September 2010;34(9):1371–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott-Pillai R, Spence D, Cardwell CR, Hunter A, Holmes VA. The impact of body mass index on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a retrospective study in a UK obstetric population, 2004–2011. BJOG. July 2013;120(8):932–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network Writing G. Association between stillbirth and risk factors known at pregnancy confirmation. JAMA. December 14 2011;306(22):2469–2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunner S, Stecher L, Ziebarth S, et al. Excessive gestational weight gain prior to glucose screening and the risk of gestational diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetologia. October 2015;58(10):2229–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein RF, Abell SK, Ranasinha S, et al. Association of Gestational Weight Gain With Maternal and Infant Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. June 06 2017;317(21):2207–2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muscati SK, Gray-Donald K, Koski KG. Timing of weight gain during pregnancy: promoting fetal growth and minimizing maternal weight retention. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. June 1996;20(6):526–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelstein EA, Brown DS, Wrage LA, Allaire BT, Hoerger TJ. Individual and aggregate years-of-life-lost associated with overweight and obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). February 2010;18(2):333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finkelstein EA, Strombotne KL. The economics of obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. May 2010;91(5):1520S–1524S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skouteris H, Hartley-Clark L, McCabe M, et al. Preventing excessive gestational weight gain: a systematic review of interventions. Obes Rev. November 2010;11(11):757–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Streuling I, Beyerlein A, Rosenfeld E, Hofmann H, Schulz T, von Kries R. Physical activity and gestational weight gain: a meta-analysis of intervention trials. BJOG. February 2011;118(3):278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Streuling I, Beyerlein A, von Kries R. Can gestational weight gain be modified by increasing physical activity and diet counseling? A meta-analysis of interventional trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. October 2010;92(4):678–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker LO. Managing excessive weight gain during pregnancy and the postpartum period. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. Sep-Oct 2007;36(5):490–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claesson IM, Sydsjo G, Brynhildsen J, et al. Weight after childbirth: a 2-year follow-up of obese women in a weight-gain restriction program. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. January 2011;90(1):103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaikh H, Robinson S, Teoh TG. Management of maternal obesity prior to and during pregnancy. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. April 2010;15(2):77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dodd JM, Crowther CA, Robinson JS. Dietary and lifestyle interventions to limit weight gain during pregnancy for obese or overweight women: a systematic review. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2008;87(7):702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ronnberg AK, Nilsson K. Interventions during pregnancy to reduce excessive gestational weight gain: a systematic review assessing current clinical evidence using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system. BJOG. October 2010;117(11):1327–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claesson IM, Josefsson A, Sydsjo G. Weight six years after childbirth: a follow-up of obese women in a weight-gain restriction programmme. Midwifery. May 2014;30(5):506–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oteng-Ntim E, Varma R, Croker H, Poston L, Doyle P. Lifestyle interventions for overweight and obese pregnant women to improve pregnancy outcome: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2012;10:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quinlivan JA, Julania S, Lam L. Antenatal dietary interventions in obese pregnant women to restrict gestational weight gain to Institute of Medicine recommendations: a meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. December 2011;118(6):1395–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thangaratinam S, Rogozinska E, Jolly K, et al. Interventions to reduce or prevent obesity in pregnant women: a systematic review. Health Technol. Assess. July 2012;16(31):iii–iv, 1–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thangaratinam S, Rogozinska E, Jolly K, et al. Effects of interventions in pregnancy on maternal weight and obstetric outcomes: meta-analysis of randomised evidence. BMJ. 2012;344:e2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muktabhant B, Lawrie TA, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M. Diet or exercise, or both, for preventing excessive weight gain in pregnancy. The Cochrane Library. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butryn ML, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Consistent self-monitoring of weight: a key component of successful weight loss maintenance. Obesity (Silver Spring). December 2007;15(12):3091–3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Catenacci VA, Ogden LG, Stuht J, et al. Physical activity patterns in the National Weight Control Registry. Obesity (Silver Spring). January 2008;16(1):153–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care. September 2006;29(9):2102–2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackson L Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into practice: a review of community interventions. Diabetes Educ. Mar-Apr 2009;35(2):309–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raeburn JM, Atkinson JM. A low-cost community approach to weight control: initial results from an evaluated trial. Prev. Med. July 1986;15(4):391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodearmel SJ, Wyatt HR, Barry MJ, et al. A family-based approach to preventing excessive weight gain. Obesity (Silver Spring). August 2006;14(8):1392–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soltani H, Arden M, Duxbury A, Fair F. An Analysis of Behaviour Change Techniques Used in a Sample of Gestational Weight Management Trials. Journal of pregnancy. 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardner B, Wardle J, Poston L, Croker H. Changing diet and physical activity to reduce gestational weight gain: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. July 2011;12(7):e602–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeo S, Walker JS, Caughey MC, Ferraro AM, Asafu-Adjei JK. What characteristics of nutrition and physical activity interventions are key to effectively reducing weight gain in obese or overweight pregnant women? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. April 2017;18(4):385–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clifton RG, Evans M, Cahill AG, et al. Design of lifestyle intervention trials to prevent excessive gestational weight gain in women with overweight or obesity. Obesity. 2016;24(2):305–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cahill AG, Haire-Joshu D, Cade WT, et al. Weight Control Program and Gestational Weight Gain in Disadvantaged Women with Overweight or Obesity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). March 2018;26(3):485–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parents as Teachers National Center. PAT Quality Assurance Guidelines. 2016; http://www.parentsasteachers.org/images/stories/QA_guidelines_May_2016.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- 46.Parents as Teachers National Center. ABOUT PARENTS AS TEACHERS. 2018; https://parentsasteachers.org/about/. Accessed May 9, 2018.

- 47.Thomson JL, Tussing-Humphreys LM, Goodman MH, Olender SE. Gestational Weight Gain: Results from the Delta Healthy Sprouts Comparative Impact Trial. J Pregnancy. 2016;2016:5703607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brownson R, Colditz G, Proctor E. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. 2nd Edition ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. (In press). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm. Policy Ment. Health. January 2009;36(1):24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.CFIR Research Team. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). http://cfirguide.org/. Accessed June 27, 2017.

- 53.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. Fifth ed New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nilsen P Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practce. 3rd ed San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sallis JF, Owen N. Ecological models. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education. Second ed San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1997:403–424. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pankratz M, Hallfors D, Cho H. Measuring perceptions of innovation adoption: the diffusion of a federal drug prevention policy. Health Educ. Res. June 2002;17(3):315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Panzano PC, Sweeney HA, Seffrin B, Massatti R, Knudsen KJ. The assimilation of evidence-based healthcare innovations: a management-based perspective. The journal of behavioral health services & research. 2012;39(4):397–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steckler A, Goodman RM, McLeroy KR, Davis S, Koch G. Measuring the diffusion of innovative health promotion programs. Am. J. Health Promot. Jan-Feb 1992;6(3):214–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aarons GA. Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Ment Health Serv Res. June 2004;6(2):61–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sams LD, Rozier RG, Wilder RS, Quinonez RB. Adoption and implementation of policies to support preventive dentistry initiatives for physicians: a national survey of Medicaid programs. Am. J. Public Health. August 2013;103(8):e83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Henderson JL, MacKay S, Peterson-Badali M. Closing the research-practice gap: factors affecting adoption and implementation of a children’s mental health program. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. February 2006;35(1):2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whitaker KM, Wilcox S, Liu J, Blair SN, Pate RR. Patient and Provider Perceptions of Weight Gain, Physical Activity, and Nutrition Counseling during Pregnancy: A Qualitative Study. Womens Health Issues. Jan-Feb 2016;26(1):116–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Duthie EA, Drew EM, Flynn KE. Patient-provider communication about gestational weight gain among nulliparous women: a qualitative study of the views of obstetricians and first-time pregnant women. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. December 11 2013;13:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stengel MR, Kraschnewski JL, Hwang SW, Kjerulff KH, Chuang CH. “What my doctor didn’t tell me”: examining health care provider advice to overweight and obese pregnant women on gestational weight gain and physical activity. Womens Health Issues. Nov-Dec 2012;22(6):e535–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hebert ET, Caughy MO, Shuval K. Primary care providers’ perceptions of physical activity counselling in a clinical setting: a systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. July 2012;46(9):625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang ML, Arroyo J, Druker S, Sankey HZ, Rosal MC. Knowledge, Attitudes and Provider Advice by Pre-Pregnancy Weight Status: A Qualitative Study of Pregnant Latinas With Excessive Gestational Weight Gain. Women Health. 2015;55(7):805–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nikolopoulos H, Mayan M, MacIsaac J, Miller T, Bell RC. Women’s perceptions of discussions about gestational weight gain with health care providers during pregnancy and postpartum: a qualitative study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. March 24 2017;17(1):97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yeo S, Samuel-Hodge CD, Smith R, Leeman J, Ferraro AM, Asafu-Adjei JK. Challenges of Integrating an Evidence-based Intervention in Health Departments to Prevent Excessive Gestational Weight Gain among Low-income Women. Public Health Nurs. May 2016;33(3):224–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Campbell EE, Dworatzek PD, Penava D, et al. Factors that influence excessive gestational weight gain: moving beyond assessment and counselling. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet. November 2016;29(21):3527–3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huynh M, Borrell LN, Chambers EC. Maternal education and excessive gestational weight gain in New York city, 1999–2001: the effect of race/ethnicity and neighborhood socioeconomic status. Matern Child Health J. January 2014;18(1):138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O’Brien EC, Alberdi G, McAuliffe FM. The influence of socioeconomic status on gestational weight gain: a systematic review. Journal of public health (Oxford, England). April 07 2017:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zigler E, Pfannenstiel JC, Seitz V. The Parents as Teachers program and school success: a replication and extension. J Prim Prev. March 2008;29(2):103–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stirman SW, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implementation Science. 2012;7(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Campbell B Applying knowledge to generate action: A community-based knowledge translation framework. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2010;30(1):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Colditz GA, Emmons KM, Vishwanath K, Kerner JF. Translating science to practice: community and academic perspectives. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. Mar-Apr 2008;14(2):144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. January 9 2008;299(2):211–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Emmons KM, Viswanath K, Colditz GA. The role of transdisciplinary collaboration in translating and disseminating health research: lessons learned and exemplars of success. Am. J. Prev. Med. August 2008;35(2 Suppl):S204–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dzewaltowski DA, Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Estabrooks PA, Brock E. RE-AIM: evidence-based standards and a Web resource to improve translation of research into practice. Ann. Behav. Med. October 2004;28(2):75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gholami J, Majdzadeh R, Nedjat S, Maleki K, Ashoorkhani M, Yazdizadeh B. How should we assess knowledge translation in research organizations; designing a knowledge translation self-assessment tool for research institutes (SATORI). Health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am. J. Public Health. August 2003;93(8):1261–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]