Abstract

Objective

Scalable nonpharmacologic treatment options are needed for chronic pain conditions. Migraine is an ideal condition to test smartphone-based mind-body interventions (MBIs) because it is a very prevalent, costly, disabling condition. Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) is a standardized, evidence-based MBI previously adapted for smartphone applications for other conditions. We sought to examine the usability of the RELAXaHEAD application (app), which has a headache diary and PMR capability.

Methods

Using the “Think Aloud” approach, we iteratively beta-tested RELAXaHEAD in people with migraine. Individual interviews were conducted, audio-recorded, and transcribed. Using Grounded Theory, we conducted thematic analysis. Participants also were asked Likert scale questions about satisfaction with the app and the PMR.

Results

Twelve subjects participated in the study. The mean duration of the interviews (SD, range) was 36 (11, 19–53) minutes. From the interviews, four main themes emerged. People were most interested in app utility/practicality, user interface, app functionality, and the potential utility of the PMR. Participants reported that the daily diary was easy to use (75%), was relevant for tracking headaches (75%), maintained their interest and attention (75%), and was easy to understand (83%). Ninety-two percent of the participants would be happy to use the app again. Participants reported that PMR maintained their interest and attention (75%) and improved their stress and low mood (75%).

Conclusions

The RELAXaHEAD app may be acceptable and useful to migraine participants. Future studies will examine the use of the RELAXaHEAD app to deliver PMR to people with migraine in a low-cost, scalable manner.

Keywords: Migraine, Progressive Muscle Relaxation, mHealth, Smartphone, Mind Body Intervention

Introduction

Research indicates that mind-body interventions (MBIs), including progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) and biofeedback, are effective treatments for a wide range of conditions. They can help manage chronic pain and reduce stress, insomnia, and depression [1]. Moreover, they are safe, and PMR has grade A evidence for migraine prevention [2,3]. However, access to evidence-based MBI administered by a therapist in an in-person setting is limited [4]. The proliferation of mHealth smartphone applications provides a potential solution to access to behavioral treatments. Many of these apps are available for help with self-management of chronic conditions including chronic pain conditions such as migraine and associated symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia. Thus, smartphone-based, electronically delivered MBIs developed for chronic pain conditions might be used as a scalable method for delivering evidence-based MBIs. However, the majority of mHealth apps are untested, and their effectiveness is unknown [5,6]. Many lack the input of patients and clinicians in their development [7]. In fact, in a systematic review of smartphone applications for chronic pain, 66% of the apps did not include health care professionals in the development of the app, and few had evidence-based features [8]. In a review of commercially available headache diary apps, only 18% of the apps were developed with scientific or clinical expertise [9].

Given its high prevalence and rates of disability, migraine is an ideal condition to test smartphone-based MBIs. Despite the availability of more than 100 headache apps, including some that purport to treat headache with MBI, limited data exist on the usability of smartphone applications with MBIs for migraine [10]. Research has already shown that patients prefer smartphone apps with electronic headache diaries to paper diaries and that smartphone headache diaries are a reliable method for data collection [11]. Yet most headache studies involving electronic diaries with MBIs were done without smartphone capability [10].

We developed the RELAXaHEAD app based on the app used in the Stress Management in Living with Epilepsy (SMILE) study [12]. The SMILE study accessed smartphone-based PMR in epilepsy patients. The RELAXaHEAD app has the same PMR as the SMILE study but also includes a daily headache diary. The electronic daily diary platform was co-developed with Irody, using their electronic diary platform and cloud-based technology [13]. Given the benefits (increased utilization, satisfaction, and usability) of engaging users in the design and development of health information technology systems, we sought to apply the usability testing guidelines [14] to assess the initial impressions of migraine patients as they navigate the app on their own. Thus, we sought to iteratively evaluate the usability of the Android smartphone application RELAXaHEAD.

Methods

Overview

This study is part of an optimization process for RELAXaHEAD, a smartphone e-diary and PMR-based intervention for migraine. We had participants with migraine interact with an operational app while observed by study research staff. We recorded their thoughts and observed their behavior in real time on a single occasion and summarized their experience and our observations.

This study was conducted at the NYU Langone Medical Center, a large urban medical center in New York City. The study had NYU Institutional Review Board approval. People who self-identified with migraine who were affiliated with the NYU Departments of Neurology and Emergency Medicine (either as patients or as staff) were invited to participate in the study. Convenience sampling was used until data saturation was reached.

Background on the App

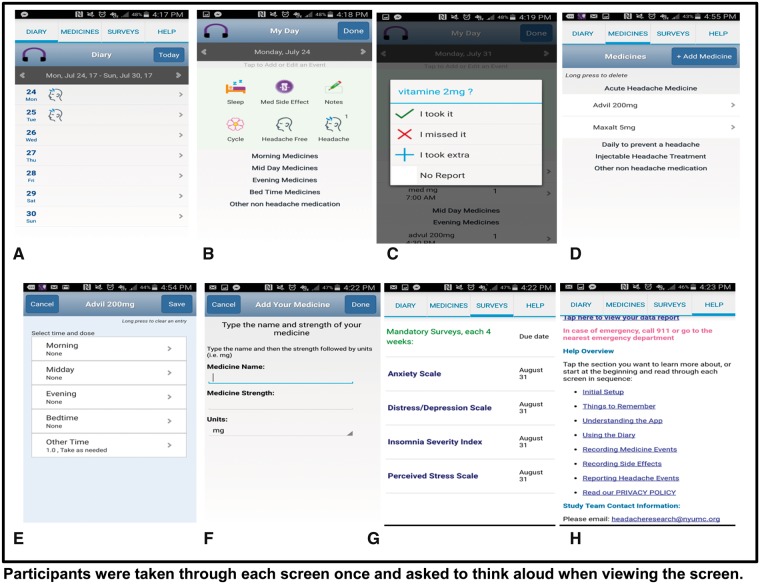

The RELAXaHEAD app consists of an electronic headache diary with the option to deliver PMR. When the app is opened, users indicate whether they have had a headache. If present, details regarding the headache are recorded including pain intensity and duration. Within the sleep icon, users respond to validated sleep questions, for example, time in bed, self-reported time asleep, and measures of sleep quality from the Consensus Sleep Diary. Users also input the medications taken and medication side effects. The RELAXaHEAD app allows the use of reminders and timely follow-up of noncompliant participants via real-time investigator data monitoring capabilities. Users can receive a patient report to share with their provider. There are two PMR audio files embedded in the RELAXaHEAD app. One is a short version (approximately five minutes), and the other is a longer version (approximately 15 minutes). Users are instructed that in the prior SMILE study [12], patients were instructed to do the PMR for 20 minutes a day. Our RELAXaHEAD app has backend analytics built-in to record the amount of time spent playing the PMR. Screenshots can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

RELAXaHEAD app screens show the diary tab (A) where users were asked to enter information about their headache, sleep, medication side effect, notes, menstrual cycle (B), and medicine report (C). The medication tab (D) includes both abortive and daily preventive migraine medications, including routes of administration (E), dosing, and timing (F). There is also the option of injections given by medical professionals, for example, nerve blocks, onabotuinum toxin. The app also gives users the option to track nonmigraine medications. Monthly surveys (G) can ne completed anytime but participants are prompted to complete them when they are due. The help tab (H) includes a link to a data report which can be viewed by the user and shared with a healthcare provider.

Think Aloud Methodology

Using usability testing methods, MTM (a board-certified neurologist-subspecialty trained and certified headache specialist) and AB (a research assistant trained by MTM in the conduct of headache research) conducted face-to-face interviews with audio-recordings to capture how the users carry out representative tasks; for example, entry of daily headache diary data, medications used, and sleep data. During the recordings, using a scripted protocol, they used the “Think Aloud” approach [15], whereby users’ comments were recorded and coded while they thought aloud and used RELAXaHEAD. The Think Aloud script used in the study can be found in the Supplementary Data. Observations could be made about any issues the end users confronted during the study. The audio was fully transcribed and coded. Interviews were conducted until data saturation was reached. General thematic analysis was used to analyze the content of the transcripts, allowing themes and subthemes to emerge iteratively from the transcripts. Contextual evaluation was accomplished as two authors (AJ and EO) individually created a list of codes for each transcript and then collaboratively compared and agreed upon codes across all reviewed studies. To ensure the trustworthiness of the findings, the third author (MTM)—who has expertise in headache medicine and mHealth—independently evaluated the transcripts and analysis and provided feedback to enhance the rigor of the overall approach.

Quantitative Analyses

At the end of the interview, the participants were asked Likert-scaled questions about satisfaction with the app and the PMR. Descriptive analyses were conducted in Excel.

Results

There were 12 participants who completed the Think Aloud protocol, all of whom were over 18 years of age and first-time users of the RELAXaHEAD application. Ten of the participants were willing to complete a survey about their demographics, headaches, and more (Appendix). The 11th participant was willing to share information about smartphone type and prior smartphone app use for headaches and behavioral treatment but not additional information.

The feedback provided during the interviews conducted between February and March 2017 allowed for multiple iterations of the app. The length of the interviews ranged from 19 to 53 minutes. The mean duration of the interviews (SD) was 36 (11) minutes. Table 1 shows participant demographics, headache characteristics, and prior health care and smartphone app utilization. The participants were predominantly female (80%). The mean age (range) was 37.5 ± 15.97 (20–74) years. Participants started experiencing headaches between the ages of nine and 34 years. Thirty percent of the participants reported doing behavioral therapy/MBI for migraine (20% Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and 10% PMR). Among the 11 participants who responded, 10 (91%) reported that they had never used a smartphone app for headaches, and nine (82%) reported never using a smartphone app for behavioral treatments like relaxation.

Table 1.

Participant demographics, headache characteristics, and prior health care and smartphone app utilization

| Participant Information | N = 10 |

|---|---|

| Gender, % female/% male | 80/20 |

| Age | |

| Current, mean ± SD [range], y | 37.5 ± 15.97 [20–74] |

| Started having headaches, mean ± SD [range], y | 19.7 ± 8.1 [9–34] |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White/Caucasian, No. (%) | 7 (70) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander, No. (%) | 1 (10) |

| Hispanic, No. (%) | 1 (10) |

| Black, No. (%) | 10 (10) |

| Headache characteristics | N = 10 |

| Average No. of headache d/mo, mean ± SD [range] | 7.6 ± 7.2 [1–22] |

| Average pain intensity (0–10 pain scale), mean ± SD [range] | 7.3 ± 1.4 [5–10] |

| Current pain intensity (0–10 pain scale), mean ± SD [range] | 3.3 ± 2.9 [0–8] |

| Headache health care utilization | N = 10 |

| Do you see a physician in an office for your headaches? | |

| No, No. (%) | 6 (60) |

| Yes, No. (%) | 4 (40) |

| Is the physician a neurologist? | |

| Neurologist, No. (%) | 3 (30) |

| Have you previously been to the emergency department for headaches? | |

| No visits to the ED, No. (%) | 7 (70) |

| 3 times, No. (%) | 1 (10) |

| 5 times, No. (%) | 1 (10) |

| >20 times, No. (%) | 1 (10) |

| Have you previously done any of the behavioral therapies for migraine | |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, No. (%) | 2 (20) |

| Biofeedback, No. (%) | 0 (0) |

| Progressive muscle relaxation, No. (%) | 1 (10) |

| Smartphone app usage | N = 12 |

| Own an iPhone, No. (%) | 9 (75) |

| Own an Android, No. (%) | 3 (25) |

| Age when first owned a smartphone | N = 10 |

| Range, y | 15–60 |

| Mean, y | 31.6 |

| SD, y | 14.8 |

| Have you ever used a smartphone app for your headaches? | N = 11 |

| No, No. (%) | 10 (91) |

| Yes, No. (%) | 1 (9) |

| Have you ever used a smartphone app for behavioral treatments like relaxation? | N = 11 |

| No, No. (%) | 9 (82) |

| Yes, No. (%) | 2 (18) |

There were 12 participants who completed the Think Aloud protocol. Ten of the participants were willing to complete a survey about their demographics, headaches, and more. The 11th participant was willing to share information about smartphone type and prior smartphone app use for headaches and behavioral treatment but not additional information.

ED = emergency department.

Participants were also asked to complete questions regarding their satisfaction with their experience using the app, daily diary, and the PMR. Of the 12 participants, 75% thought the daily diary was easy to use, 75% agreed that it was relevant to help track their headaches, 83% thought the information in the app was easy to understand, and 75% agreed that the app kept their interest and attention during the session. Ninety-two percent of the participants indicated that they would be happy to use the app again. Regarding the PMR, 75% agreed when asked whether it helped improve their stress and low mood, and 83% thought the PMR taught them skills to help handle future problems. The PMR kept the interest and attention of 75% of the participants.

The hierarchy of coding taxonomy, a description of each theme and supporting quotations, is shown in Table 2. Five themes emerged from the study: app aesthetic/appearance, app functionality, app utility/practicality, opinions of PMR, and other (personal reactions). As the “Think Aloud” interviews were conducted, users did not comment on certain factors of the application because they had already been modified. (The research team was constantly making adjustments to the application based on the feedback of the participants during the beta testing period, e.g., addition of other medication side effects.)

Table 2.

Themes and coding taxonomy

|

|

|

|

Help Tab’s Usefulness |

|

|

Ability to Use Diary |

|

| Medication Tracking |

|

|

| Notes Entry |

|

|

| Survey Tab |

|

|

| Side Effects Tracking |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discussion

This study examined the user experience with the RELAXaHEAD smartphone application. Although many mHealth apps already exist, there are few that are medically validated or developed with patient feedback in mind [5]. Thus, this study represents the initial steps in an effort to fill this void and create a smartphone tool with an MBI that is developed with headache specialist, psychologist, and patient input, and that can be further evaluated in trials to assess whether an app with the evidence-based PMR therapy can be successfully delivered to people with migraine. There was an overall consensus that the early version of the RELAXaHEAD app is acceptable to migraine participants; they perceive it as helpful in tracking migraine information and see the potential for the PMR in the app.

Migraine Diary

The diary feature of the app proved useful and easy to use for participants to input data. Our findings that many participants valued the mobile diary are consistent and in line with prior evidence that examined headache diaries in electronic formats. Studies have shown that mobile headache diaries are more efficient than paper headache diaries and are generally preferred by patients, with mobile diaries eliciting greater headache diary compliance. In our study, the majority of the participants agreed that the application has clear screen visibility, and the various icons were understandable. As stated earlier, the research team was constantly making adjustments to the application based on the feedback of the participants during the beta testing period. Therefore, participants toward the end of the interview period did not comment on certain factors of the application because they had already been modified. Of note, there were two suggestions not completely adapted in the iterative process. 1) Several participants suggested a food tab on the application, noting that they wanted to determine whether certain foods might be migraine triggers. We addressed this by adding a Notes section. However, we did not create a tab specifically for food triggers because, based on expert opinion, we did not think that would be most appropriate. 2) Four participants made a suggestion for the app to auto-calculate sleep duration, based on the start time and end time that they input. Our team considered this suggestion but did not implement the feature as we felt that time in bed is not necessarily the same as actual time asleep.

MBI-Progressive Muscle Relaxation

This study is one of the few that evaluates the mobile delivery of MBIs for headache. PMR was positively viewed by participants, with the top three descriptors for this section being interesting, useful, and helpful. In terms of the satisfaction questions, 75% stated that the PMR kept their interest, and 83% stated that they would be happy to do it again. This indicates that the smartphone-delivered PMR is a promising method for migraine patients.

Strengths

The authors felt that this study reached a level of data saturation with the 12 participants. The first evidence of this is being able to fit all the codes into five themes. On a more specific level, many of the participants’ comments fit into the same codes because their comments and opinions were closely related. Even if the study had more participants, the results would likely have been the same. Another strength of the study was the large age range among the participants, which allowed for greater variation.

Limitations

There are several limitations in the preliminary development and assessment of the RELAXaHEAD app, and they mainly focus on generalizability. 1) Only one subject had previously used an app for their headaches, and only two subjects had used an app for behavioral treatments like relaxation. Thus, since most subjects had never used a headache app before, it may be hard to distinguish whether subjects liked the concept of using an app for headache management vs liked the RELAXaHEAD app specifically. 2) There may have been some selection bias with the satisfaction data; subjects were unblinded and were comprised of clinical staff and patients. In addition, subjects were recruited from the same medical center.

Future Directions

We plan to study the acceptability and feasibility of using the RELAXaHEAD app in migraine patients. In this way, we will study compliance and engagement with the app and examine techniques to improve compliance. Using RELAXaHEAD, we seek to determine whether we might be able to offer a low-cost, easy-to-access, scalable MBI to people with migraine in various medical settings.

Conclusions

The RELAXaHEAD app may be acceptable and useful to people with migraine. Future studies will examine the use of the RELAXaHEAD app to deliver PMR to people with migraine in a low-cost, scalable manner.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the investigators in the Stress Management in Living with Epilepsy (SMILE) study and the Shor Foundation for Epilepsy Research for allowing the use of the PMR audio-recordings. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Devin Mann for his help in developing the methodology for the user testing of the RELAXaHEAD application. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Devin Mann and Dr. John Torous for their review of the manuscript.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data may be found online at http://painmedicine.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding sources: Dr. Mia Minen has a NIH K23 (AT009706-01) and is a recipient of the American Academy of Neurology-American Brain Foundation Practice Research Training Fellowship, which has supported her salary to conduct this research. In addition, this study was supported by a grant from the New York University Clinical Translational Science Institute (NYU CTSI) (UL1TR001445).

Disclosure and conflicts of interest: Dr. Mia Minen receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health, the American Academy of Neurology–American Brain Foundation, the NYU CTSI, the NYU Center for Healthcare Innovation Delivery Services, the International Headache Academy, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Dr. Minen was previously PI of an investigator initiated study with Curelator but that study is no longer taking place. There was no financial relationship that would have occurred if the study had taken place. Ms. Adama Jalloh and Ms. Emma Ortega have no disclosures. Dr. Scott Powers has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and from the Migraine Research Foundation. Dr. Richard B. Lipton receives research support from the NIH: 2PO1 AG003949 (Program Director), 5U10 NS077308 (PI), 1RO1 AG042595 (Investigator), RO1 NS082432 (Investigator), K23 NS09610 (Mentor), K23AG049466 (Mentor). He also receives support from the Migraine Research Foundation and the National Headache Foundation. He serves on the editorial board of Neurology and as senior advisor to Headache. He has reviewed for the National Institute on Aging and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; holds stock options in eNeura Therapeutics and Biohaven Holdings; and serves as consultant, advisory board member, or has received honoraria from: American Academy of Neurology, Alder, Allergan, American Headache Society, Amgen, Autonomic Technologies, Avanir, Biohaven, Biovision, Boston Scientific, Dr. Reddy’s, Electrocore, Eli Lilly, eNeura Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pernix, Pfizer, Supernus, Teva, Trigemina, Vector, Vedanta. He receives royalties from Wolff’s Headache (8th ed., Oxford Press University, 2009), Wiley, and Informa. Dr. Mary Ann Sevick has funding for her research from the NIH, the Aetna Foundation, and Merck.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the NYU Langone Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1. Blanaru M, Bloch B, Vadas L, et al. The effects of music relaxation and muscle relaxation tech- niques on sleep quality and emotional measures among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Mental Illness 2012;4(13):59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Campbell J, Penzien D, Wall E. Evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache: Behavioral and physical treatments. 2000. Available at: http://tools.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/gl0089.pdf (accessed April 21, 2018).

- 3. Kropp P, Meyer B, Dresler T, et al. Relaxation techniques and behavioural therapy for the treatment of migraine: Guidelines from the German migraine and headache society. Schmerz 2017;31(5):433–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andrasik F. Behavioral treatment of headaches: Extending the reach. Neurol Sci 2012;33(suppl 1):S127–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Portelli P, Eldred C.. A quality review of smartphone applications for the management of pain. Br J Pain 2016;10(3):135–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kropp P, Meyer B, Meyer W, Dresler T.. An update on behavioral treatments in migraine—current knowledge and future options. Expert Rev Neurother 2017;17(11):1059–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mosadeghi-Nik M, Askari MS, Fatehi F.. Mobile health (mHealth) for headache disorders: A review of the evidence base. J Telemed Telecare 2016;22(8):472–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wallace LS, Dhingra LK.. A systematic review of smartphone applications for chronic pain available for download in the united states. J Opioid Manag 2014;10(1):63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hundert A, Huguet A, McGrath P, Stinson J, Wheaton M.. Commercially available mobile phone headache diary apps: A systematic review. JMR Mhealth Uhealth 2014;2(3):e36.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Minen MT, Torous J, Raynowska J, et al. Electronic behavioral interventions for headache: A systematic review. J Headache Pain 2016;17:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giffin NJ, Ruggiero L, Lipton RB, et al. Premonitory symptoms in migraine: An electronic diary study. Neurology 2003;60(6):935–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haut SR, Lipton RB, Cornes S, et al. Behavioral interventions as a treatment for epilepsy: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Neurology 2018;90(11):e963–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irody. http://www.irody.com (accessed March 2018).

- 14. US Department of Health and Human Services. Usability guidelines. 2016. Available at: https://guidelines.usability.gov/ (accessed March 2017).

- 15. Daniels J, Fels S, Kushniruk A, Lim J, Ansermino JM.. A framework for evaluating usability of clinical monitoring technology. J Clin Monit Comput 2007;21(5):323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.