Abstract

We used provider (n = 112) data that staff at the agency disseminating the Family Check-Up (FCU; REACH Institute) collected to profile provider diversity in community settings and to examine whether provider profiles are related to implementation fidelity. Prior to FCU training, REACH Institute staff administered the FCU Provider Readiness Assessment (PRA), a provider self-report measure that assesses provider characteristics previously linked with provider uptake of evidence-based interventions. We conducted a latent class analysis using PRA subscale scores as latent class indicators. Results supported four profiles: experienced high readiness (ExHR), experienced low readiness (ExLR), moderate experience (ME), and novice. The ExHR class was higher than all other classes on: 1) personality variables (i.e., agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, extraversion); 2) evidence-based practice attitudes; 3) work-related enthusiasm and engagement; and 4) their own well-being. The ExHR class was also higher than ExLR and ME classes on clinical flexibility. The ME class was lowest of all classes on conscientiousness, supervision, clinical flexibility, work-related enthusiasm and engagement, and well-being. During the FCU certification process, FCU Consultants rated providers’ fidelity to the model. Twenty-three of the 112 providers that completed the PRA also participated in certification. We conducted follow-up regression analyses using fidelity data for these 23 providers to explore associations between probability of class membership and fidelity. The likelihood of being in the ExHR class was related to higher FCU fidelity, whereas the likelihood of being in the ExLR class was related to lower fidelity. We discuss how provider readiness assessment data can be used to guide the adaptation of provider selection, training, and consultation in community settings.

Keywords: Provider profiles, Implementation, Readiness, Adaptation, Competency drivers

Introduction

Family-centered interventions that promote positive parenting practices are effective in preventing child problem behavior (O’Connell, Boat, & Warner, 2009). When interventions scale up, however, effects may be attenuated due to declines in implementation quality (Kilbourne, Neumann, Pincus, Bauer, & Stall, 2007). Differences between providers in research versus community settings are one factor that may contribute to declines (Fixsen, Blase, Naoom, & Wallace, 2009). In studies, researchers select highly skilled providers but, in community practice, providers vary widely in skills and experiences (August et al., 2004). The uptake, effectiveness, and sustainability of an evidence-based intervention (EBI) depends on adaptation to accommodate variability in community settings, including provider variation (Chambers, Glasgow, & Stange, 2013). We used data that staff at the agency disseminating the Family Check-Up (FCU; Dishion & Stormshak, 2007) collected to profile provider diversity in community settings. We examine how implementation fidelity differs across profiles and discuss implications for implementation. We also discuss the FCU Implementation Framework and how it integrates ongoing assessment of factors that might impact implementation. Finally, we describe the FCU implementation support system, a digital data system that enables data-driven adaptations to implementation.

The Family Check-Up (FCU)

The FCU is a brief intervention that reduces child problem behaviors by improving parenting quality and family relations (Dishion & Stormshak, 2007). It is grounded in motivational interviewing and has three steps: an interview, an assessment with questionnaires and videotaped parent-child interactions, and a feedback session to review assessment results and identify intervention goals and follow-up services, including evidenced-based parenting support (Dishion, Stormshak, & Kavanagh, 2012). The FCU was tested in randomized controlled trials with diverse families. With young children, FCU increased positive parenting and decreased maternal depression; both leading to reductions in child disruptive behavior (Dishion et al., 2008; Shaw, Connell, Dishion, Wilson, & Gardner, 2009). The FCU increased children’s language development and inhibitory control (Chang, Shaw, Dishion, Gardner, & Wilson, 2014) and reduced emotional distress (Shaw et al., 2009). When tested in middle schools (Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003), FCU increased parental monitoring, which reduced adolescent drug use (Dishion, Nelson, & Kavanagh, 2003) and family conflict, leading to decreases in antisocial behavior (Van Ryzin & Dishion, 2012; Van Ryzin, Stormshak, & Dishion, 2012).

The program developer designed FCU to be embedded within diverse service sectors to promote scaling up and out into service systems at the local, state, or national level. Three FCU features facilitate its adoption in diverse settings: (1) an emphasis on tailoring to meet the needs of families and service systems, (2) a flexible framework to link to other EBIs, and (3) a focus on motivating family engagement. This paper focuses on FCU scale-up in community health agencies, where significant variation has necessitated adaptation of implementation strategies.

The Family Check-Up Implementation Framework

The Arizona State University REACH Institute (REACH) began dissemination in 2014 using the FCU Implementation Framework (FCU IF) to support quality implementation. The FCU IF integrates the stage-based Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment framework (EPIS; Aarons, Hurlburt, & Horwitz, 2011) and the determinants-based Implementation Drivers framework (Fixsen et al., 2009), which outlines phase-specific capacities for implementation readiness. The four EPIS phases are: Exploration, when a site considers changing services and explores alternatives; Preparation, when a site selects an EBI and prepares for delivery; Implementation, when a site begins using the EBI; and Sustainment, when the site has integrated the EBI into its system. The Implementation Drivers framework posits that three core implementation drivers (i.e., competency, organization, leadership) support sustainable implementation. Competency drivers include provider selection, training, and consultation. Organization drivers include facilitative administration (e.g., policies supporting implementation), systems-level interventions (e.g., leveraging economic support), data decision support systems, and any other infrastructure that supports implementation. Leadership includes technical and adaptive leadership needed to effectively manage change that follows implementation of an innovation.

According to EPIS, factors associated with the outer (e.g., system-level factors such as the sociopolitical context) and inner (e.g., provider characteristics) context influence implementation at each phase. The FCU IF incorporates assessment of inner context factors to identify implementation barriers and facilitators, which are aligned with implementation drivers. The REACH team that is disseminating the FCU uses these data to adapt implementation strategies to optimize driver-related capacities to implement the FCU. For example, in the preparation phase, they assess provider readiness and use these data to inform competency drivers. Specifically, data are used to identify providers likely to champion the FCU, individualize training and consultation to accommodate trainee characteristics, match trainees with FCU Consultants, and monitor implementation benchmarks (e.g., % providers certified).

The FCU Implementation Support System.

Initial and ongoing assessment of implementation is central to the FCU IF and enabled by FCU’s Implementation Support System (ISS) - a digital system that collects, stores and synthesizes data. During the preparation phase, the REACH team uses the ISS to collect data on provider readiness and training satisfaction; during the implementation phase they use the ISS to monitor fidelity, implementation barriers, and a site’s progress in regards to implementation benchmarks. For example, FCU Consultants, certified by the REACH team to train and supervise FCU providers, rate provider fidelity. Consultants enter ratings in the ISS to track what providers meet FCU certification criteria. REACH staff assess if benchmarks (i.e., % of providers certified) are being met and, if not, engage administrators to address barriers. Consultants also report on group consultation attendance, which the ISS translates into a participation index (i.e., proportion of providers trained that attended). If participation is poor, REACH staff discuss barriers to uptake with the site. The ISS is also used to collect qualitative data on implementation barriers. Illustratively, a consultant once commented that providers at a site were apprehensive about the professional consequences of failing to meet fidelity and certification criteria and perceived FCU’s fidelity measure as a “secretive test.” This prompted the consultant’s supervisor at REACH to advise the consultant to train providers on the FCU’s fidelity measure and encourage self-assessment of fidelity so they would not be so apprehensive.

Provider Readiness.

Several provider factors have been linked to readiness to implement EBIs. For example, studies suggest experience influences uptake; however, studies are mixed regarding whether more or less experience is associated with improved uptake (Beidas et al., 2013; Skriner et al, 2017). Our own research suggests that “less veteran” providers trained in relatively few other EBIs are more likely to adopt the FCU (Lewis et al., 2016). One of the most studied provider characteristics is attitudes towards EBIs. Some studies support positive links between attitudes and adoption (Nelsen & Steele, 2007), but others suggest no relationship (Skriner et al., 2017). Clinical flexibility and supervision may also influence implementation. Flexible providers may be more likely to adopt EBIs (Aarons, 2004) and be more skillful at adapting them, while maintaining fidelity (Forehand, Dorsey, Jones, Long, & McMahon, 2010); supervision promotes fidelity, thereby affecting program outcomes (Schoenwald, Sheidow, & Chapman, 2009). Personal and professional well-being can also influence implementation. Positive well-being has been linked to uptake (Hemmelgarn, Glisson, & James, 2006), and provider work exhaustion has been negatively associated with adoption (Aarons, Fettes, Flores, & Sommerfeld, 2009) and quality of care (Salyers et al., 2015). Personality characteristics, such as extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness, have also been linked to fidelity (Klimes-Dougan et al., 2009). The FCU Provider Readiness Assessment (PRA) is a self-report measure to assess provider characteristics previously linked to implementation readiness, including clinical experience and flexibility, attitudes about EBIs, supervisory support, personal and professional well-being, and personality characteristics.

Purpose of This Study

A cornerstone of the FCU IF is assessing contextual factors that impact implementation to inform implementation strategies. The PRA assesses one element of the “inner context,” provider characteristics, to inform selection, training, and consultation. This study uses PRA data from FCU-trained community providers to explore provider profiles and the relation between profiles and fidelity. We hypothesize that profiles varying in readiness will be represented in our data and that profiles reflecting high readiness will have higher fidelity ratings. Although this is an exploratory study with a limited number of providers, the results have implications for optimizing provider selection, training, and post-training consultation.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

One-hundred eighty-six providers participated in FCU trainings between 2014 and 2017. Providers were from sites that self-selected to implement the FCU and approached REACH for training (n=19). Seventeen sites were in the United States, representing 13 states, and 2 were international. During training registration, REACH staff e-mailed all providers (n=186) at each of the 19 sites an invitation to participate in this study, with a link to complete the PRA; 60% (n=112) agreed to participate. Prior to participating, providers gave REACH consent to use their data. Participants represented 19 sites and the number of participants per site ranged from 1 to 35 (Mdn = 3.0). Ethnicities included White (82%), Hispanic (7%), African-American (8%), and Other (3%); 12% did not report ethnicity. Eighty-four (75%) were female. Most participants had a master’s degree (76%); 16% had a bachelor’s degree or less; 8% had a doctorate. We only had fidelity data for 23 of the 112 providers that participated in fidelity monitoring or certification post training. The REACH data manger de-identified PRA data by linking provider and site to an identification number (ID), to which only she had access. IDs were used to link PRA data to other data (e.g., fidelity) and were stored in a password-protected file. REACH had only minimal information on providers that declined participating in this study; they were 81% female; 48% had a master’s degree; 36% had a bachelor’s degree or less; 14% had a doctorate. The Arizona State University Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Measures

Measures included an FCU-specific measure of fidelity and the PRA.

COACH.

COACH (Dishion, Knutson, Brauer, Gill, & Risso, 2010) is an observational measure of fidelity with five dimensions. The acronym “COACH” represents the initial letter of each of the five dimensions: Conceptually accurate and adherent, Observant and responsive to the family’s needs, Active in structuring session, Careful when teaching and providing feedback, and Hope and motivation generating. Because rigid adherence may indicate an absence of responsiveness to the client (Kakeeto, Lundmark, Hasson, & Thiele Schwarz, 2017), COACH assesses both adherence and competence with which the FCU is delivered. For example, providers should tailor the FCU to meet the needs of each family, which requires implementing core components without rigidly adhering to a manual. “Observant and responsive” assessed the skill with which the provider adapted intervention content and process to meet a family’s needs. Each COACH dimension was rated on a scale from 1 to 9. Scores in the 1–3 range indicate minimal skills and knowledge; 4–6 indicates process skills and conceptual understanding are acceptable; 7–9 indicates mastery of key process skills and concepts. A score of 4 on each domain is considered “threshold” fidelity. COACH scores are predictive of change in parenting practices and child outcomes (Smith et al., 2013).

In this study, a composite (mean) score across dimensions was computed; higher scores indicated better fidelity. Scores ranged from 2.0 to 6. 6 (M = 4.9, SD = 1.0; α = 0.90). During certification, the consultants reviewed providers’ videotaped sessions on REACH’s online video portal and uploaded COACH ratings to the ISS. They subsequently met with the provider for consultation. To maintain COACH reliability, once a month the consultants assessed fidelity of the same session. They uploaded ratings to the ISS for comparison to gold standard ratings and met as a team to discuss reliability. The gold standard was assessed by a team at REACH that included the program developer and FCU Implementation Director. Consultants were reliable if their ratings were within one point of the gold standard score.

Provider Readiness Assessment (PRA).

Education.

Providers reported their education using a single item. Responses were (1) a bachelor’s degree or less, (2) a master’s degree, or (3) a doctorate.

Years of experience.

Providers reported years of practice. The scale ranged from 0 = less than 1 year, recoded as 0.5 years, to 12 = 12 or more years, with all other response options in integer years; 17% reported 1 year or less; 18% reported 12 or more years of experience (Mdn = 5.0).

Number of EBIs using.

Providers reported the EBIs they were using, which we summed to equal a count (Mdn = 1.0).

Evidence-based practice attitudes.

We used the Evidence-Based Practice Attitudes Scale (Aarons 2004), with 15 items on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all; 4 = to a very great extent) and four subscales: appeal (i.e., willingness to adopt a new practice if it is intuitively appealing), requirements (i.e., would a provider adopt a new practice if mandated), openness (i.e., openness to learning and implementing innovations), and divergence (i.e., extent to which provider perceives EBIs as clinically useful), which was reverse-scored. We averaged the subscales; higher scores reflect more positive attitudes (α = 0.84).

Clinical flexibility.

We developed a 9-item subscale on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all; 4 = definitely) to assess clinical flexibility (e.g., “I would like to try a new therapy, even if it differs from what I am doing”; see Appendix A). Higher scores reflect more flexibility. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) supported one-factor: χ2(26) = 36.32; RMSEA = 0.06, 90% CI (0.01, 0.10) (Steiger, 1989); CFI = 0.99 (Bentler, 1990), TLI = 0.98 (Tucker & Lewis, 1973), and SRMR = 0.01 (α = 0.71).

Supervisory support.

We developed a 9-item subscale on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all; 4 = definitely) to assess supervisory support (e.g., “to what extent does your supervisor help you set boundaries with clients”; see Appendix A). Higher scores reflect more support. A CFA provided less than adequate fit to the data. After reviewing modification indices, we allowed 3 items (i.e., “review and give feedback on session audio tapes,” “review and give feedback on session video tapes,” and “discuss your case treatment plans with you”) to covary. The revised model fit adequately: χ2(24) = 47.18; RMSEA = 0.09, 90% CI (0.05, 0.13); CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.93; and SRMR = 0.05 (α= 0.91).

Work-related enthusiasm and engagement.

We used the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (Demerouti, Mostert, & Bakker, 2010). It has two subscales (work-related exhaustion and disengagement); each has 8 items on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly agree; 4 = strongly disagree). We reverse scored the response scale so higher scores reflect more enthusiasm (i.e., “when I work I usually feel energized”) and engagement (i.e., “I always find new and interesting aspects of my work”; α = 0.87).

Provider well-being.

We developed a 7-item subscale on a 4-point scale (1 = none at all; 4 = nearly all) for provider self-report on number of days they experienced various symptoms in the past month (e.g., “feeling down, depressed or hopeless”; see Table A1). A CFA provided excellent fit: χ2(13) = 14.23 RMSEA = 0.03, 90% CI (0.01, 0.10); CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99; and SRMR = 0.02. Two items, “feeling angry or irritable” and “not being able to control hostile or aggressive feelings,” covaried (α = 0.85).

Personality characteristics.

The PRA has four subscales from the Big Five Inventory (Goldberg, 1990): openness (10 items; α = 0.78), conscientiousness (8 items; α = 0.79), extroversion (8 items; α = 0.85), and agreeableness (8 items; α =0.70). Items are on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree); higher scores equal more of the characteristic.

Data Analyses.

We used Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (IBM, 2016) to conduct a Missing Value Analysis (MVA) to test whether PRA data were missing completely at random (Little, 1988). We conducted latent class analysis (LCA) using MPlus 8.0 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2018). The LCA included 112 providers, with PRA subscales as class indicators. LCA models were estimated using full information maximum likelihood and a sandwich estimator to adjust standard errors for clustering by site. We selected the optimal number of classes based on: 1) Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978); 2) sample size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SABIC; Sclove 1987); 3) entropy > 0.80; 4) average class probabilities >.80; and 5) whether all classes were substantively useful. The BIC and SABIC consider fit and parsimony, with lower values favored. Entropy and average class probabilities range from 0 to 1; higher values indicate greater confidence in classification. We used 500 random starting values and required that the best log-likelihood replicate. After selecting a model, we used MODEL CONSTRAINT to test the significance of between-class differences on conditional response means to aid interpretation. When running the final model, we used the SAVEDATA command to save probabilities of class membership for each class, which we modeled as predictors of fidelity in separate univariate regressions. We used listwise deletion to include only 23 providers with fidelity data in the regression analyses. Prior to the LCA, we computed correlations between class indicators.

Results

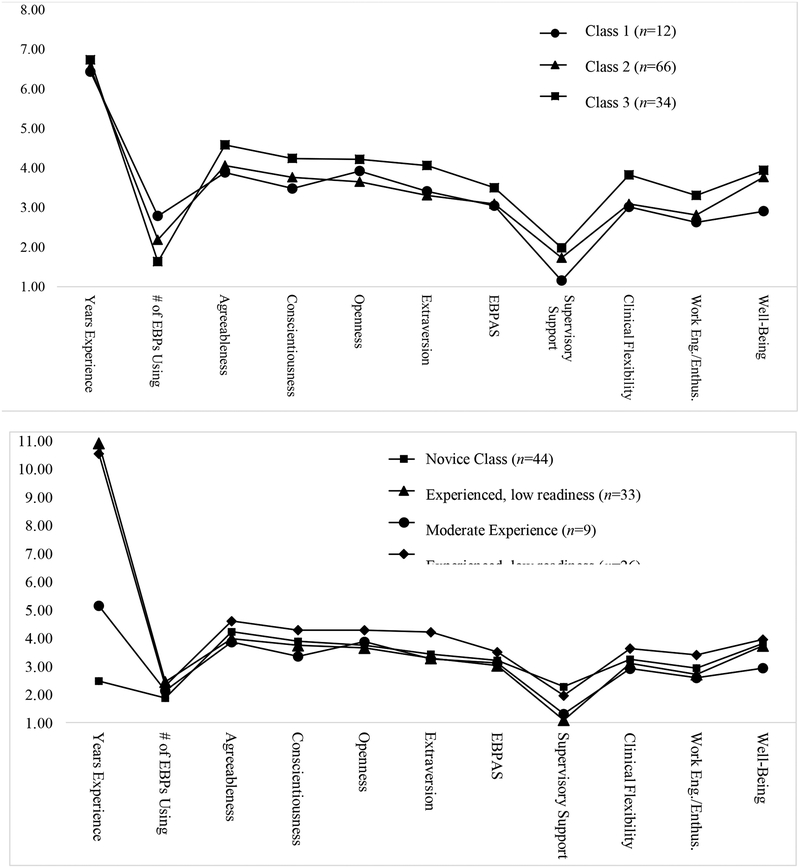

Means and standard deviations for PRA subscales modeled as indicators in the LCA are presented in Table 1; correlations between latent class indicators are presented in Table 2. The pattern of missing values was completely random (χ2 (46) =59.44, p > .05). We estimated 1, 2, 3, and 4-class solutions; see Table 3 for fit criteria. The covariance coverage for LCA indicators ranged from 0.44 to 1.0, exceeding minimum thresholds (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2018). The SABIC improved with the addition of classes and was best for the 4-class solution. For the 3 and 4-class solutions, entropy was greater than .80 and better than the 2-class solution, so we eliminated the 2-class solution. The average class probabilities for the 3- and 4-class solutions were greater than .80. To explore the substantive meaningfulness of the 4-class solution, we plotted conditional response means for the 3 and 4-class solutions (see Figure 1) and examined results of MODEL CONSTRAINT tests.

Table 1.

Conditional Response means and SEs of the means for the 4-class solution and mean and SD for the full sample

| NC | ExLR | ME | ExHR | Full Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SE) | M(SE) | M(SE) | M(SE) | M (SD) | |

| Years of Experience | 2.48 (0.38)a | 10.91 (0.14)b | 5.15 (0.96)c | 10.54 (0.76)b | 6.55 (4.28) |

| # of EBIs Using | 1.88 (0.31)a | 2.45 (0.34)a | 2.14 (0.65)a | 2.31 (0.72)a | 2.15 (1.50) |

| Agreeableness | 4.22 (0.07)a | 3.98 (0.07)b | 3.86 (0.27)a, b | 4.60 (0.08)c | 4.21 (0.47) |

| Conscientiousness | 3.88 (0.07)a | 3.74 (0.04)a | 3.35 (0.17)b | 4.29 (0.05)c | 3.89 (0.43) |

| Openness | 3.74 (0.06)a | 3.65 (0.09)a | 3.87 (0.20)a | 4.28 (0.03)b | 3.85 (0.56) |

| Extraversion | 3.43 (0.12)a | 3.29 (0.28)a | 3.26 (0.14)a | 4.21 (0.07)b | 3.55 (0.73) |

| EBIAS | 3.21 (0.04)a | 3.03 (0.08)a | 3.11 (0.18)a | 3.51 (0.04)b | 3.22 (0.45) |

| Supervision Practices | 2.27 (0.21)a | 1.10 (0.22)b | 1.31 (0.32)b | 1.96 (0.46)a, b | 1.68 (1.07) |

| Clinical Flexibility | 3.25 (0.18)a, b | 3.10 (0.12)b | 2.92 (0.20)b | 3.63 (0.27)a | 3.18 (0.64) |

| Work Engagement/Enthusiasm | 2.94 (0.05)a | 2.71 (0.07)b | 2.59 (0.07)b | 3.40 (0.06)c | 2.95 (0.45) |

| Well-Being | 3.81 (0.04)a | 3.73 (0.06)a | 2.94 (0.10)b | 3.95 (0.02)c | 3.74 (0.35) |

Note. NC = novice class; ExLR = experienced, low readiness class; ME = moderate experience class; ExHR = experienced, high readiness class. Degree was also included in the LCA; providers with a master’s degree had a 90% or higher probability of being in C2 or C4 and providers with a bachelor’s or doctorate had a 5% or less probability of being in these classes; providers had a 27%, 58%, and 15% probability of being in C1 if they had a bachelor’s, master’s, or doctorate, respectively; providers had a 21%, 66%, and 13% probability of being in C1 if they had a bachelor’s, master’s, or doctorate, respectively.

In each row, values with the same alphabetic superscript are not significantly different from each other, but are significantly different from values with different superscripts.

Table 2.

Correlations between PRA subscales modeled as indicators in the latent class analysis

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Years of Experience | |||||||||||

| 2. # of EBIs Using | 0.167 | ||||||||||

| 3. Agreeableness | −0.034 | −0.099 | |||||||||

| 4. Conscientiousness | 0.090 | 0.210 | 0.430*** | ||||||||

| 5. Openness | 0.051 | −0.106 | 0.199* | 0.208* | |||||||

| 6. Extraversion | 0.046 | 0.074 | 0.265** | 0.273** | 0.325** | ||||||

| 7. EBIAS | −0.010 | 0.024 | 0.449*** | 0.343** | 0.120* | 0.325** | |||||

| 8. Supervision Practices | −0.412* | −0.123 | 0.119 | −0.033 | 0.020 | 0.092 | 0.029 | ||||

| 9. Clinical Flexibility | −0.069 | −0.030 | 0.398*** | 0.041 | 0.064 | −0.027 | 0.415*** | −0.065 | |||

| 10. Work Engagement/Enthusiasm | −0.185 | −0.001 | 0.340*** | 0.390*** | 0.287** | 0.247* | 0.271** | 0.175** | 0.283* | ||

| 11. Well-Being | −0.079 | −0.028 | 0.270** | 0.392*** | 0.012 | 0.140 | 0.206** | 0.127* | 0.202* | 0.374*** | |

| 12. Degree | 0.249* | 0.120 | 0.170 | 0.116 | 0.126 | 0.003 | 0.026 | −0.112 | −0.180 | 0.079 | 0.017 |

Note. PRA =_______________________; EBIs =__________________________; EBIAS =_______________________.

p <.05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 3.

Model fit indices for latent class solutions

| 1-class | 2-class | 3-class | 4-class | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIC | 2099.831 | 2056.471 | 2064.685 | 2079.447 |

| SABIC | 2023.983 | 1936.377 | 1900.347 | 1870.864 |

| Entropy | N/A | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.82 |

| Average class probabilities | N/A | c1 = 0.94 c2 = 0.94 |

c1 = 0.87 c2 = 0.94 c3 = 0.94 |

c1 = 0.86 c2 = 0.87 c3 = 0.99 c4 = 0.93 |

| class sizes (n) | 112 | c1 = 77 c2 = 35 |

c1 = 12 c2 = 66 c3 = 34 |

c1 = 44 c2 = 33 c3 = 9 c4 = 26 |

Note. BIC = Bayesian information criterion; SABIC = sample size adjusted Bayesian information criterion; c = class. The BIC and SABIC consider fit and parsimony, with lower values being favored. Entropy is an index that reflect accuracy of classification, with higher values (i.e., closer to 1.0) suggesting solution is a good fit.

Figure 1.

Conditional response means for each class for the 3-class and 4-class solutions. The 4-class solution was accepted as the final solution. The upper figure displays the conditional response means for each of three classes for the 3-class solution. The lower figure displays the conditional response means for each of the four classes for the 4-class solutions. EBPs = evidence-based programs; EBP AS = Evidence-Based Practice Attitudes Scale; Work Eng/Enthus = Work-related engagement and enthusiasm.

The 4-class solution distinguished two highly experienced classes, with one higher than all others on readiness indicators, except number of EBIs and supervisory support (see Table 1). We labeled these classes “experienced, high readiness” (ExHR) and “experienced, low readiness” (ExLR). For both classes, the probability of having a master’s was 90% or higher; the probability of having a bachelor’s or less or a doctorate was 5% or less. Providers in the third class (moderate experience; ME) had slightly more than 5 years of experience. The final class (novice class; NC) had less than 2.5 years of experience. The NC was higher than the ME class on conscientiousness, supervision, well-being, and work-related enthusiasm and engagement and higher than the ExLR class on agreeableness, supervision, and work-related enthusiasm and engagement. The ME class was lower than the ExLR class on conscientiousness and well-being. Based on these results, we considered the 4-class solution to be substantively useful. Probability of class membership for ExHR was positively associated with fidelity (β = 1.09, SE = 0.45, p < .05), whereas probability of class membership for ExLR was negatively associated with fidelity (β = −0.52, SE = 0.24, p < .05). Class membership for the other classes was unrelated to fidelity.

Discussion

This study used data collected by staff at the agency disseminating the FCU (i.e., REACH) to profile diversity in implementation readiness among providers in community settings and to examine the relationship between profiles and fidelity. Four provider profiles emerged: experienced high readiness (ExHR), experienced low readiness (ExLR), moderate experience (ME), and novice. The likelihood of being in the ExHR class was related to higher FCU fidelity, whereas the likelihood of being in the ExLR class was related to lower fidelity. The ExHR class was higher than all others on personality variables, evidence-based practice attitudes, work-related enthusiasm and engagement, and well-being. The ME class was lowest on: conscientiousness, supervisory support, clinical flexibility, work-related enthusiasm and engagement, and well-being. Consistent with other research showing more experience does not predict better fidelity (Campbell et al., 2013), our study suggests individual personality attributes, attitudes about EBIs, and personal and professional well-being, may differentiate high and low fidelity better than experience. Experienced providers who were high on indicators of implementation readiness were more likely to implement FCU with fidelity than were providers with an equivalent amount of experience who were low on these indicators.

Consistent with EPIS (Aarons et al., 2011), our results suggest that provider characteristics are an important inner context factor and emphasize the value of assessing provider readiness. If provider readiness promotes adoption and fidelity, identifying and assessing provider characteristics associated with readiness may promote EBI sustainment. Selecting providers likely to adopt and implement an intervention well will optimize its effectiveness and facilitate its integration into the service system in which it is embedded. Because training and consultation quality may also promote EBI sustainment, assessing provider readiness and using this information to optimize training and consultation experiences can also support EBI sustainment.

Implications for FCU Implementation

Even though this study is exploratory due to its limited number of sites and providers, the results have implications for optimizing provider selection, training, and post-training consultation.

Provider selection.

PRA data can be used by sites to support assessment-driven provider selection and by providers to assess if the FCU is a good fit for them. During a provider orientation in the preparation phase, potential FCU providers learn about personal and professional capacities of effective FCU providers based on the PRA to encourage self-assessment of their readiness for training and implementation. Administrators are encouraged to allow providers to opt out of training because top-down administrative mandates requiring their participation are an implementation barrier (Lewis et al., 2016).

Training.

Because provider perceptions that EBIs are rigid contribute to negative attitudes towards them (Mahrer, 2005), when training providers who report strong negative attitudes, trainers should focus on the FCU as an adaptive intervention that providers can tailor to individual families; highlighting the FCU’s flexibility promotes uptake (Lewis et al., 2016). Because resistance to EBIs can be rooted in providers’ beliefs that EBI adherence impedes rapport (Mahrer, 2005), trainers also may emphasize that relational process skills are integral to FCU fidelity. Because the use of multiple EBIs may diminish motivation to develop expertise in the FCU (Beidas et al., 2014), trainers should teach providers how to integrate the FCU with other EBIs.

Consultation and certification.

PRA data can inform provider certification timelines, with those low on readiness receiving more intensive consultation. If PRA data suggest supervision is not normative, the FCU dissemination team at REACH explores whether providers’ time for consultation and certification is protected and, if not, works with administrators to resolve this barrier (e.g., implement policies to incentivize certification). Consultants can also use provider profiles to guide consultation. For example, when initially learning the model, some providers experience the preparation to deliver the FCU (e.g., rating family interaction tasks) as a challenge. Consultants may offer more support to providers low on work-related enthusiasm and engagement who may be particularly vulnerable to these frustrations.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study’s small sample size is a limitation, restricting the variety of profiles that may otherwise have emerged. Moreover, completing the PRA is voluntary and some providers opted out, introducing self-selection bias. To understand differences between providers that do and do not complete the PRA, the REACH staff disseminating the FCU now collect descriptive data at registration from all trainees. Also, because fidelity data was limited to a subset of providers that completed the PRA, the sample in the regression analyses may not represent the larger population of FCU-trained providers. Due to limited resources, several sites only contracted with REACH for training. This is concerning given that fidelity to the FCU may improve with additional consultation (Smith et al., under review).

We did not include measures assessing organizational readiness, which can affect implementation. Another measures-related limitation is that PRA indices are self-reported. For example, we did not verify providers’ self-reports of the number of EBIs they are using against an objective measure, and providers may have overestimated this figure. As the FCU dissemination team at REACH collects additional data, a future study should replicate our results with a larger and more representative sample and include measures of organizational readiness and other site descriptors to explore how site-level factors moderate the relation between provider profiles and fidelity.

Conclusions

Providers in community practice vary widely in skills, experience, and characteristics (August et. al., 2004). The uptake, effectiveness, and sustainability of an EBI requires adapting implementation strategies to accommodate this variation (Chambers et al., 2013). As the FCU continues scale up, diversity in service contexts and providers will increase. We will learn more about the ways that contextual factors affect implementation, and the capacity to adapt to the increasing diversity will be essential. Tools such as the PRA, which are employed in the context of data feedback systems like the FCU ISS, are key in supporting data-driven adaptations to implementation strategies to increase EBI uptake, effectiveness, and sustainment.

Acknowledgments

Funding. There was no funding support for the development of this manuscript.

Table A1. Items for the three Provider Readiness Assessment (PRA) subscales that were developed for the Family Check-Up: Clinical Flexibility, Supervisory Support, and Provider Well-Being.

| Clinical Flexibility: We are interested in understanding your current practices, your interest in learning tools and techniques, and your current supervision. How much do you agree with the following statements? |

| 0 = Not at all |

| 1 = A little |

| 2 = Somewhat |

| 3= Very Much |

| 4= Definitely |

|

| Supervisory Support: The following questions ask about your current level of clinical supervision and your expectations about supervision. |

| 0 = Not at all |

| 1 = A little |

| 2 = Somewhat |

| 3= Very Much |

| 4= Definitely |

Your current supervisor does which of the following:

|

| Well-Being: Here are a number of statements that may or may not apply to you. Please indicate how many days in the last month you been bothered by any of the following problems? |

| 1 = Not at all |

| 2 = Several days |

| 3 = Over ½ the days |

| 4= Nearly All |

|

|

Footnotes

Research involving Human Participants. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Arizona State University’s IRB and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent. We obtained informed consent from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Thomas Dishion is the developer of the Family Check-Up. Dr. Anne M. Mauricio is an Associate Research Professor at the Arizona State University REACH Institute, and Mrs. Letham and Lopez are staff at the REACH Institute. The authors declare that they have no other conflicts of interest.

References

- Aarons GA (2004). Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services Research, 6(2), 61–74. doi: 10.1023/B:MHSR.0000024351.12294.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Fettes DL, Flores LE Jr, & Sommerfeld DH (2009). Evidence-based practice implementation and staff emotional exhaustion in children’s services. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(11), 954–960. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, & Horwitz SM (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35(1), 4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Edmunds J, Ditty M, Watkins J, Walsh L, Marcus S, & Kendall P (2014). Are inner context factors related to implementation outcomes in cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth anxiety? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(6), 788–799. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0529-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BK, Buti A, Fussell HE, Srikanth P, McCarty D, & Guydish JR (2013). Therapist predictors of treatment delivery fidelity in a community-based trial of 12-step facilitation. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 39(5), 304–311. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.799175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DA, Glasgow R, & Stange K (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science, 5(1), 117–128. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Gardner F, & Wilson MN (2014). Direct and indirect effects of the Family Check-Up on self-regulation from toddlerhood to early school-age. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(7), 1117–1128. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9859-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti E, Mostert K, & Bakker AB (2010). Burnout and work engagement: A thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(3), 209–222. doi: 10.1037/a0019408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, & Kavanagh K (2003). Intervening in Adolescent Problem Behavior: A Family-Centered Approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Connell A, Weaver C, Shaw D, Gardner F, & Wilson M (2008). The Family Check-Up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development, 79(5), 1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Knutson N, Brauer L, Gill A, & Risso J (2010). Family Check-Up: COACH ratings manual. Unpublished coding manual. Available from Child and Family Center.

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, & Kavanagh KA (2012). Everyday parenting: A professional’s guide to building family management skills. Research Press Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, & Kavanagh K (2003). The Family Check-Up with high-risk young adolescents: Preventing early-onset substance use by parent monitoring. Behavior Therapy, 34(4), 553–571. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80035-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, & Stormshak EA (2007). Intervening in children’s lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/11485-000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Blase KA, Naoom SF, & Wallace F (2009). Core implementation components. Research on Social Work Practice, 19(5), 531–540. doi: 10.1177/1049731509335549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Dorsey S, Jones DJ, Long N, & McMahon RJ (2010). Adherence and flexibility: They can (and do) coexist! Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(3), 258–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01217.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR (1990). An alternative” description of personality”: The big-five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1216–1229. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.6.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmelgarn AL, Glisson C, & James LR (2006). Organizational culture and climate: Implications for services and interventions research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(1), 73–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00008.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kakeeto M, Lundmark R, Hasson H, & Thiele Schwarz U (2017). Meeting patient needs trumps adherence. A cross-sectional study of adherence and adaptations when national guidelines are used in practice. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 23(4), 830–838. doi: 10.1111/jep.12726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, Bauer MS, & Stall R (2007). Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: Application of the replicating effective programs framework. Implementation Science, 2, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimes-Dougan B, August GJ, Lee CYS, Realmuto GM, Bloomquist ML, Horowitz JL, & Eisenberg TL (2009). Practitioner and site characteristics that relate to fidelity of implementation: The Early Risers prevention program in a going-to-scale intervention trial. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(5), 467–475. doi: 10.1037/a0014623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Darnell D, Kerns S, Monroe-DeVita M, Landes SJ, Lyon AR, … & Puspitasari A (2016, June). Proceedings of the 3rd Biennial Conference of the Society for Implementation Research Collaboration (SIRC) 2015: Advancing efficient methodologies through community partnerships and team science. In Implementation Science, 11(1), 85. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0428-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim A, Nakamura BJ, Higa-McMillan CK, Shimabukuro S, & Slavin L (2012). Effects of workshop trainings on evidence-based practice knowledge and attitudes among youth community mental health providers. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(6), 397–406. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 53(404), 1198–1202. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahrer AR (2005). Empirically supported therapies and therapy relationships: What are the serious problems and plausible alternatives? Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 35, 3–25. doi: 10.1007/s10879-005-0800-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2011). Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TD & Steele RG (2007). Predictors of practitioner self-reported use of evidence-based practices: Practitioner training, clinical setting, and attitudes toward research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34(4), 319–330. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell ME, Boat T, & Warner KE (2009). Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse among Children, Youth, and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities.

- Salyers MP, Fukui S, Rollins AL, Firmin R, Gearhart T, Noll JP, … & Davis CJ (2015). Burnout and self-reported quality of care in community mental health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(1), 61–69. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0544-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Sheidow AJ, & Chapman JE (2009). Clinical supervision in treatment transport: Effects on adherence and outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 410–421. doi: 10.1037/a0013788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176344136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sclove SL (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52, 333–343. doi: 10.1007/BF02294360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Connell A, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, & Gardner F (2009). Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects on early childhood problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 21(2), 417–439. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skriner LC, Wolk CB, Stewart RE, Adams DR, Rubin RM, Evans AC, & Beidas RS (2017). Therapist and organizational factors associated with participation in evidence-based practice initiatives in a large urban publicly-funded mental health system. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11414-017-9552-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, & Wilson MN (2013). Indirect effects of fidelity to the family check-up on changes in parenting and early childhood problem behaviors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(6), 962–974. doi: 10.1037/a0033950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Rudo-Stern J, Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, Montag S, Brown K, Ramos K, Shaw DS, & Wilson MN (under review). A quasi-experimental study of the effectiveness and efficiency of observationally assessing fidelity to a family-centered intervention. Manuscript submitted for publication [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger J (1989). Causal modeling: A supplementary module for SYSTAT and SYGRAPH. Evanston, IL: Systat. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, & Lewis C (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02291170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, & Dishion TJ (2012). The impact of a family-centered intervention on the ecology of adolescent antisocial behavior: Modeling developmental sequelae and trajectories during adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 24(03), 1139–1155. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Stormshak EA, & Dishion TJ (2012). Engaging parents in the family check-up in middle school: Longitudinal effects on family conflict and problem behavior through the high school transition. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(6), 627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]