Abstract

Background and Aims:

National guidelines for colonoscopy screening and surveillance assume adequate bowel preparation. We used New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry (NHCR) data to investigate the influence of bowel preparation quality on endoscopist recommendations for follow-up intervals in average-risk patients following normal screening colonoscopies.

Methods:

The analysis included 9170 normal screening colonoscopies performed on average risk individuals aged 50 and above between February 2005 and September 2013. The NHCR Procedure Form instructs endoscopists to score based on the worst prepped segment after clearing all colon segments, using the following categories: excellent (essentially 100% visualization), good (very unlikely to impair visualization), fair (possibly impairing visualization), and poor (definitely impairing visualization). We categorized examinations into 3 preparation groups: optimal (excellent/good) (n = 8453), fair (n = 598), and poor (n = 119). Recommendations other than 10 years for examinations with optimal preparation, and > 1 year for examinations with poor preparation, were considered nonadherent.

Results:

Of all examinations, 6.2% overall received nonadherent recommendations, including 5% of examinations with optimal preparation and 89.9% of examinations with poor preparation. Of normal examinations with fair preparation, 20.7% of recommendations were for an interval <10 years. Among those examiations with fair preparation, shorter-interval recommendations were associated with female sex, former/nonsmokers, and endoscopists with adenoma detection rate ≥ 20%.

Conclusions:

In 8453 colonoscopies with optimal preparations, most recommendations (95%) were guideline-adherent. No guideline recommendation currently exists for fair preparation, but in this investigation into community practice, the majority of the fair preparation group received 10-year follow-up recommendations. A strikingly high proportion of examinations with poor preparation received a follow-up recommendation greater than the 1-year guideline recommendation. Provider education is needed to ensure that patients with poor bowel preparation are followed appropriately to reduce the risk of missing important lesions.

Keywords: colonoscopy, bowel preparation, adenoma

Colonoscopy is currently the most widely used screening test for colorectal cancer (CRC) prevention and early detection in the United States. Prevention of CRC is accomplished through detection and removal of potentially precancerous polyps before those lesions can progress to CRC. Because adequacy of bowel preparation affects the ability to detect polyps during colonoscopy,1–3 an adequate preparation is essential in order to ensure optimal use of colonoscopy in CRC prevention. National guidelines which recommend screening and surveillance intervals between colonoscopies assume adequate bowel preparation.4,5 However, up to a third of colonoscopies have been found to have fair (visualization possibly impaired) or poor (visualization definitely impaired) bowel preparation,1,6,7 and it has been estimated that inadequate bowel preparation increases colonoscopy costs by 12% to 22%.8

Colonoscopies with a “poor” bowel preparation are considered incomplete due to inadequate mucosal visualization, and shorter intervals for follow-up have been recommended for individuals with poor preparations for almost 2 decades.9–13 Since 200111,13 “prompt repeat” or rescheduling of such examinations has been suggested. In 2012, national guidelines issued by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer (USMSTF) recommended repeat colonoscopies within a year following most colonoscopies with poor (inadequate) bowel preparation.5 Limited evidence suggests that adherence to this guideline is surprisingly inconsistent, with highly variable follow-up recommendations following colonoscopies with a poor preparation.14–16

In colonoscopies with “fair” (suboptimal) bowel preparation, it is unclear whether and to what degree follow-up recommendations should be shortened to accommodate less than ideal, but not significantly impaired, visualization. Data regarding whether detection rates are adversely affected by fair bowel preparations are conflicting,17 although recent studies suggest there may be no decrease in serrated polyp or adenoma detection in examinations with fair bowel preparation as compared with superior quality preparations.18,19 Current national guidelines do not include clear recommendations for follow-up intervals following colonoscopies with fair bowel preparation,5 and recent research indicates that endoscopists often shorten recommended surveillance intervals following colonoscopies with a fair preparation in order to minimize the potential that missed lesions could progress to CRC.14–16,20–23

To date, those studies which have explored the influence of bowel preparation quality on actual interval recommendations have been relatively small in scale,21–23 lacking data on endoscopist characteristics,16,21,22 and without a standardized scoring system for bowel preparation quality. We believe this to be the first large scale ( > 9000 colonoscopies) study of the effect of bowel preparation quality on endoscopist adherence to nationally recommended follow-up interval guidelines.

In this study, we use data from the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry (NHCR) to investigate the influence of bowel preparation quality on endoscopist recommended follow-up intervals in average-risk patients following a normal screening colonoscopy. We compare follow-up interval recommendations given by NHCR endoscopists with USMSTF screening guidelines.

METHODS

Study Design

The NHCR, which began as a pilot study in 2 endoscopy centers in 2004 and subsequently expanded statewide, is a National Cancer Institute, American Cancer Society, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-funded population-based registry that prospectively collects comprehensive colonoscopy data from patients and endoscopists at practices across New Hampshire. Unique features of the NHCR include the ability to link pathology with colonoscopy report findings at the level of the polyp, and the extensive follow-up time (over 10 y) for early enrollees. The methodology and design of the NHCR are described in detail elsewhere.24,25 The NHCR study protocol, consent form and all data collection tools have been approved by the Dartmouth College Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (Hanover, NH), as well as by relevant human subjects review committees at participating sites.

Study Cohort

The study cohort included 9344 average-risk individuals aged 50 years or older and with no family history of CRC, with a normal (no findings) screening colonoscopy between February 2005 and September 2013. We required the screening colonoscopy to have a bowel preparation quality recorded and a specific time interval follow-up recommendation given by the endoscopist immediately following the colonoscopy. We excluded colonoscopies which were incomplete for reasons other than poor bowel preparation (N = 232), as well as colonoscopies completed by endoscopists with fewer than 25 colonoscopies available for this analysis (N = 179). If an individual had more than one colonoscopy eligible for this analysis, only the first colonoscopy was included. The resulting cohort included 9170 average-risk patients whose normal screening colonoscopies were performed in 25 New Hampshire facilities by 65 endoscopists.

Definitions

Exposure (Bowel Preparation)

The NHCR bowel preparation classification has been in use since 2004. Quality of bowel preparation is recorded by endoscopists on the NHCR Procedure Form, which instructs them to score based on the worst prepped segment, and after clearing all colon segments, as recently supported by the USMSTF26 and others.27 Every endoscopy site is oriented to the NHCR and its forms when they begin participating. Four categories of bowel preparation are provided as the preparation quality options on the NHCR Procedure Form, including the following descriptions, which appear in full on every report form: excellent (only scattered, tiny particles and/or clear liquid—100% visualization possible throughout colon), good (easily removable small amounts of particles and/or liquid—very unlikely to impair visualization throughout colon), fair (residual feces and/or non-transparent fluid —possibly impairing visualization), and poor (feces and/or nontransparent fluid—definitely impairing visualization). For the purpose of this study we collapsed colonoscopies with good and excellent bowel preparation into a single category of optimal, supported by recent evidence that adenoma detection rate (ADR) does not significantly differ between these categories of bowel preparation.18

Outcome (Nonadherent Follow-up Recommendations)

The current NHCR procedure form provides options to indicate specific follow-up interval recommendations. For the purposes of this study, nonadherence is defined based on a comparison of the follow-up recommendations chosen by endoscopists on the NHCR Procedure Form and published evidence to support recommendations, as summarized within the USMSTF guidelines.5

A nonadherent follow-up recommendation was defined as a recommended follow-up interval <10 years or > 10 years for those average-risk patients with no findings who received an optimal bowel preparation rating, consistent with the USMSTF recommendation for this group. For poor bowel preparations, a nonadherent follow-up recommendation was identified if the recommended follow-up interval was > 1 year. Additional time interval recommendations are also investigated and reported, to provide more detail about recommendations in general use over the study time period.

The USMSTF guidelines do not provide specific follow-up recommendations for normal colonoscopies with fair bowel preparation, since evidence is lacking on which to base such a recommendation. Furthermore, recommendations commonly used in clinical practice following a fair preparation are also unclear. Investigation into follow-up intervals following fair preparations in the NHCR provides insight into current community practice patterns in the face of unclear guidelines.

Patient and Endoscopist Characteristics

Patient characteristics are collected on the NHCR Patient Questionnaire, completed by each consenting patient before colonoscopy.24,25 These include age at colonoscopy (categorized for this analysis by decade, 50 to 59, 60 to 69, 70+), gender, race (summarized in this analysis as white and nonwhite), body mass index (BMI) [4 BMI groups: <25 (underweight/normal), 25 to <30 (overweight), 30 to <35 (obesity class 1), 35+ (obesity classes 2 and 3)], current or past smoking status, education (dichotomized for this analysis into a high school degree or less, or some college or more) and insurance categories. Endoscopist characteristics used in this analysis include endoscopist gender and specialty (gastroenterology, surgery/other), ADR (< 20%, ≥ 20%), and median withdrawal time in normal colonoscopies (normal withdrawal time: <6 min, ≥ 6 min).

Statistical Analysis

Frequency distributions and χ2 tests were used to investigate the association between bowel preparation and patient and endoscopist characteristics. Associations were considered statistically significant if P < 0.05. In addition to specific time intervals for recommended follow-up, the proportion of nonadherent follow-up recommendations was calculated overall and by bowel preparation, for examinations with optimal and poor bowel preparation. For each level of bowel preparation (optimal, fair, poor), a multivariable logistic regression model examined the impact of patient and endoscopist factors on nonadherence (for optimal and poor) or on follow-up intervals not equal to 10 years (fair), adjusted for patients within endoscopist using a cluster-correlated robust variance estimator. Continuous age at colonoscopy was used when modelling non-adherence among the poor preparation due to low numbers in the age groups. SAS 9.428 and STATA/SE 12.129 were used for analyses.

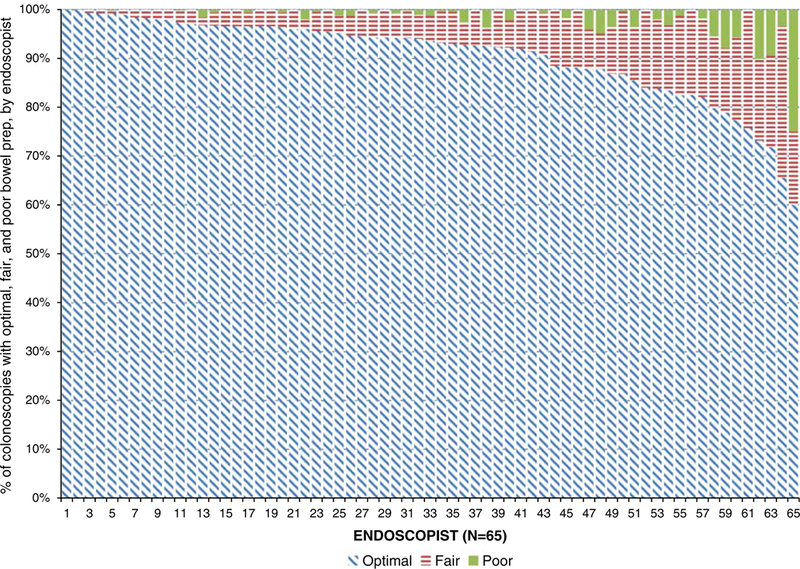

RESULTS

The mean ( ± SD) age of the study cohort was 57.2 ( ± 7.0) years and the majority of patients were white (94.9%). Most of the colonoscopy bowel preparations were reported as optimal (92.2%, including both excellent and good) followed by 6.5% fair and 1.3% poor (Table 1). However, there was variation by endoscopist in the percentage of colonoscopies classified as fair (range of 0.6% to 31.0%) and poor (range of 0.2% to 25.0%) (Fig. 1). Fourteen of the 65 endoscopists (21.5%) classified at least 15% of examinations as fair or poor. The frequency of poor preparations was very low with 62% (40/65), 12% (8/65), and 17% (11/65) of endoscopists reporting poor preparations for <1%, 1% to <2%, and 2% to <5% of examinations, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Distributions (N, %) of Bowel Preparation Quality by Patient and Endoscopist Factors for Screening Colonoscopies With No Findings in 9170 Average-risk New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry Participants

| N (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics*,2 (N = 9170) | Optimal | Fair | Poor | Total |

| Total | 8453 (92.2) | 598 (6.5) | 119 (1.3) | 9170 (100.0) |

| Age at colonoscopy (y) | ||||

| 50–59 | 5664 (92.6) | 379 (6.2) | 76 (1.2) | 6119 (66.7) |

| 60–69 | 2226 (91.6) | 169 (7.0) | 34 (1.4) | 2429 (26.5) |

| 70+ | 563 (90.5) | 50 (8.0) | 9 (1.5) | 622 (6.8) |

| Gender2 | ||||

| Male | 3356 (91.1) | 280 (7.6) | 50 (1.4) | 3686 (40.3) |

| Female | 5077 (93.0) | 316 (5.8) | 69 (1.3) | 5462 (59.7) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 7834 (92.2) | 553 (6.5) | 109 (1.3) | 8496 (94.9) |

| Nonwhite | 421 (91.9) | 30 (6.6) | 7 (1.5) | 458 (5.1) |

| Body mass index2 | ||||

| < 25 (underweight/normal) | 2757 (93.7) | 157 (5.3) | 28 (1.0) | 2942 (33.2) |

| 25 to <30 (overweight) | 3015 (91.9) | 226 (6.9) | 41 (1.3) | 3282 (37.1) |

| 30 to <35 (obesity class 1) | 1537 (92.5) | 106 (6.4) | 18 (1.1) | 1661 (18.8) |

| 35+ (obesity classes 2 and 3) | 864 (89.4) | 78 (8.1) | 24 (2.5) | 966 (10.9) |

| Current smoker2 | ||||

| Yes | 450 (86.2) | 55 (10.5) | 17 (3.3) | 522 (5.9) |

| No | 7760 (94.5) | 524 (6.3) | 98 (1.2) | 8382 (94.1) |

| Education2 | ||||

| Some college or more | 6547 (92.6) | 443 (6.3) | 80 (1.1) | 7070 (79.4) |

| High school or less | 1663 (90.5) | 139 (7.6) | 35 (1.9) | 1837 (20.6) |

| Insurance2 | ||||

| Private/HMO/Medicare | 7432 (92.7) | 500 (6.2) | 90 (1.1) | 8022 (87.5) |

| Medicaid | 194 (82.6) | 28 (11.9) | 13 (5.5) | 235 (2.6) |

| Other/none | 825 (90.9) | 67 (7.4) | 16 (1.8) | 908 (9.9) |

| Endoscopist characteristics*,2 (N = 65) | ||||

| Gender2 | ||||

| Male (N = 57) | 7069 (91.8) | 537 (7.0) | 94 (1.2) | 7700 (84.0) |

| Female (N = 8) | 1384 (94.2) | 61 (4.2) | 25 (1.7) | 1470 (16.0) |

| Specialty2 | ||||

| Gastroenterology (N = 50) | 7261 (92.6) | 486 (6.2) | 97 (1.2) | 7844 (85.5) |

| Surgery (N = 15) | 1192 (89.9) | 112 (8.5) | 22 (1.7) | 1326 (14.5) |

| Adenoma detection rate (ADR) | ||||

| ADR ≥ 20% (N = 39) | 4955 (91.7) | 375 (6.9) | 72 (1.3) | 5402 (58.9) |

| ADR < 20% (N = 26) | 3498 (92.8) | 223 (5.9) | 47 (1.3) | 3768 (41.1) |

| Median normal withdrawal time2 | ||||

| ≥ 6 min (N = 51) | 6983 (92.7) | 460 (6.1) | 94 (1.3) | 7537 (84.5) |

| < 6 min (N = 12) | 1244 (90.1) | 114 (8.3) | 23 (1.7) | 1381 (15.5) |

Missing (N): gender (22), race (216), body mass index (319), current smoker (266), education (263), insurance (5) and normal withdrawal time (252).

P-values (< 0.05) for significant associations between patient’s and endoscopist’s characteristics and bowel preparation quality.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of screening colonoscopies with no findings of 9170 average-risk New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry study participants reported as optimal, fair or poor bowel preparation quality among 65 endoscopists.

Statistically significant differences in bowel preparation quality by patient characteristics were found for gender, BMI, current smoking status, education and insurance, although most of the differences were small (Table 1). Patients who were male or obese, who were current smokers, who had a high school education or less, or who had Medicaid, were significantly more likely to have fair bowel preparation. Male endoscopists, surgeons, and endoscopists whose median normal withdrawal time was <6 minutes were more likely to have patients with fair bowel preparation. Study participants who were obese (other than class 1), current smokers and Medicaid-insured were more likely to have poor bowel preparation (Table 1).

Table 2 depicts the distribution of follow-up recommendations by bowel preparation quality. Overall, 6.2% of colonoscopies with optimal or poor preparations received nonadherent follow-up recommendations. Of colonoscopies with optimal bowel preparation, 5.0% received nonadherent recommendations, with 2.7% receiving a recommendation for <10 years (including 2.1% with a recommendation of 4 to 5 y), and 2.3% receiving a recommendation for > 10 years.

TABLE 2.

Follow-up Recommendations for Screening Colonoscopies With No Findings Among 9170 Average-risk New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry Study Participants by Bowel Preparation Quality

| Follow-up Recommendation [N (%)] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowel Preparation | ≤ 1 y | 2–3 y | 4–5 y | 6–9 y | = 10 y | > 10 y | Total Nonadherent |

| Optimal | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 180 (2.1) | 52 (0.6) | 8028 (95.0) | 191 (2.3) | 425 (5.0) |

| Fair* | 8 (1.3) | 7 (1.2) | 84 (14.1) | 25 (4.2) | 465 (77.8) | 9 (1.5) | NA |

| Poor | 12 (10.1) | 22 (18.5) | 37 (31.1) | 5 (4.2) | 41 (34.5) | 2 (1.7) | 107 (89.9) |

| Total | 21 (0.2) | 30 (0.3) | 301 (3.3) | 82 (0.9) | 8534 (93.1) | 202 (2.2) | 532 (6.2) |

Italicized text represent guideline non-adherent follow-up recommendations.

Adherence to follow-up recommendations could not be assessed because current national guidelines do not include clear recommendations for follow-up intervals following colonoscopies with fair bowel preparation.

NA indicates not available.

For colonoscopies with fair preparation, 20.7% were given follow-up recommendations shorter than 10 years, most ( 14.1%) for 4 to 5 years. Of colonoscopies with poor preparation, 89.9% were nonadherent, with 71.5% of them receiving a follow-up interval recommendation of 4 or more years. Of the 51 colonoscopies with poor preparation since the September 2012 guideline publication specifically recommending follow-up within 1-year, 7 (13.7%) were told to return within 1 year.

Among those who had an optimal bowel preparation, older age groups (60 to 69, and 70 y or older, compared with those who were 50 to 59 y old) were more likely to be given a nonadherent interval as a follow-up recommendation [odds ratio (OR), 1.33; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.01–1.75 and OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.09–2.31, respectively] (Table 3). Among patients with fair bowel preparation, female patients (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.05–2.24), former or nonsmokers (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 1.06–7.14) and patients with colonoscopies performed by female endoscopists (OR, 6.28; 95% CI, 1.71–23.1) or endoscopists with an ADR ≥ 20% were more likely to be given a follow-up recommendation not equal to 10 years (OR for endoscopists with an ADR < 20% = 0.41; 95% CI, 0.17–0.99). No patient or endoscopist factors were statistically significantly associated with nonadherent follow-up recommendations for poor bowel preparation, but the number of colonoscopies with poor bowel preparation was small and the power was limited.

TABLE 3.

OR and 95% CI1,† for the Association Between Patient and Endoscopist Characteristics and Follow-up Recommendations (Not Equal to 10 y for Examinations With Optimal and Fair Preparation, > 1 y for Examinations With Poor Preparation) Among 9170 Average-risk New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry Study Participants by Bowel Preparation Quality

| Patient Characteristics (N = 9170) | Optimal (Interval Not Equal to 10 y) [OR (95% CI)] | Fair* (Interval Not Equal to 10 y) [OR (95% CI)] | Poor (Interval not Equal to ≤ 1 y) [OR (95% CI)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at colonoscopy‡ | 1.06 (0.96–1.17) | ||

| 50–59 | Reference | Reference | |

| 60–69 | 1.33 (1.01–1.75) | 1.02 (0.72–1.45) | — |

| 70+ | 1.58 (1.09–2.31) | 0.80 (0.29–2.25) | — |

| Gender | |||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 1.18 (0.90–1.54) | 1.54 (1.05–2.24) | 1.44 (0.17–12.54) |

| Race | |||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Nonwhite | 0.78 (0.42–1.41) | 1.04 (0.40–2.67) | — |

| Body mass index | |||

| < 25 (underweight/normal) | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 25 to <30 (overweight) | 0.84 (0.67–1.06) | 0.77 (0.47–1.28) | 4.06 (0.50–32.94) |

| 30 to <35 (obesity class 1) | 1.12 (0.81–1.56) | 1.45 (0.83–2.53) | 1.98 (0.31–12.76) |

| 35+ (obesity classes 2 and 3) | 0.70 (0.46–1.08) | 1.35 (0.73–2.49) | 1.47 (0.20–10.91) |

| Current smoker | |||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| No | 1.14 (0.66–1.97) | 2.75 (1.06–7.14) | 0.49 (0.03–8.09) |

| Education | |||

| Some college or more | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| High school or less | 0.87 (0.66–1.16) | 1.12 (0.56–2.26) | 1.21 (0.10–15.34) |

| Insurance | |||

| Private/HMO/Medicare | Reference | Reference | — |

| Medicaid | 1.34 (0.68–2.66) | 1.29 (0.43–3.86) | — |

| Other/none | 0.93 (0.67–1.52) | 0.95 (0.37–2.41) | — |

| Endoscopist characteristics (N = 65) | |||

| Gender | |||

| Male (N = 57) | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Female (N = 8) | 0.79 (0.34–1.84) | 6.28 (1.71–23.1) | 4.51 (0.66–30.75) |

| Specialty | |||

| Gastroenterology (N = 50) | Reference | Reference | — |

| Surgery (N = 15) | 1.45 (0.73–2.87) | 0.45 (0.18–1.16) | — |

| ADR | |||

| ADR ≥ 20% (N = 39) | Reference | — | |

| ADR < 20% (N = 26) | 1.34 (0.72–2.50) | 0.41 (0.17–0.99) | — |

| Median normal withdrawal time | |||

| ≥ min (N = 51) | Reference | Reference | — |

| < 6 min (N = 12) | 1.38 (0.61–3.12) | 1.15 (0.42–3.17) | — |

No guideline is yet established for appropriate follow up for normal colonoscopies with fair preparation. Information is shown here to compare actual practice recommendations to a 10-year recommendation.

Models were adjusted for patient’s age at colonoscopy, race, body mass index, smoking status, education, insurance and endoscopist’s gender, specialty, ADR and median normal withdrawal time.

Continuous age at colonoscopy is used in the model for poor bowel preparation.

— indicates numbers too small to estimate; ADR, adenoma detection rate; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Statistically significant findings (P < 0.05) are bolded.

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of over 9000 NHCR colonoscopies, 95% of examinations with optimal bowel preparation quality received recommended follow-up intervals that were guideline-adherent (10 y). A striking finding of our study was the large proportion (65%) of exams with poor (inadequate) preparation for which the follow-up recommendation was 4 to 5 years or longer. While poor preparations were relatively few in number and percent (N = 119, 1.3% of all colonoscopies), it is noteworthy that 89% of colonoscopies with poor preparation were given follow-up intervals > 1 year. Over 65% were given a recommendation even longer than 3 years, with 31.1% receiving a 4 to 5 years interval recommendation and 34.5% receiving a recommendation for a 10-year interval. This is a surprising finding, as prompt repeat and shorter interval follow-up have been suggested for colonoscopies with poor preparation since as long ago as 2001.9–13 Furthermore, it is not possible to make appropriate recommendations for follow-up in the absence of knowing whether or not there are polyps present in the colon. Appropriate follow-up needs to include information about any possible pathology; therefore, an inconclusive colonoscopy (ie, one with a poor or inadequate preparation), requires early follow-up (and completion of the evaluation) in order to determine an appropriate recommendation.

“Poor” preparation is defined on NHCR forms as “definitely impairing visualization”; relatively short follow-up intervals are clearly appropriate following such colonoscopies as they are, by definition, incomplete examinations. As guidelines came into common use, the recommendation to repeat the colonoscopy at a shorter interval in patients with a poor preparation was formalized and recommended by the 2012 USMSTF guidelines, which made recommendations based on assessment of available evidence. These guidelines specifically state, “If the bowel prep is poor, the MSTF recommends that in most cases the examination should be repeated within 1 year.”5 Of the NHCR patients with poor preparation since publication of this guideline in September 2012, only 13.7% were told to come back within 1 year, leaving 86.3% with recommendations that were nonadherent to that guideline.

Given that a relatively small proportion of colonoscopy preparations were rated as poor, these likely represent colonoscopies with definitely impaired visualization, especially as every NHCR procedure form contains a clear description of “poor” preparation quality next to that choice option. Good visualization is critical to high-quality colonoscopy, and both the need to ensure adequate preparation and recognition of appropriate follow-up for poor preparation are essential to the role of colonoscopy in accomplishing prevention of CRC. Inadequate bowel preparation has been proposed as a contributing factor for interval cancers, which are detected within a few years of the index colonoscopy.30 Our finding regarding screening intervals following an examination with poor bowel preparation that are longer than the 1 year USMSTF recommendation26 highlight an area where immediate quality improvement efforts could be of significant benefit in improving colonoscopy outcomes.

Follow-up recommendations responding to preparation quality should be based on the likelihood of having missed a lesion that should have been detected. Therefore, it is the “worst prepped segment” that must inform the follow-up recommendation, rather than an average preparation quality for the entire colon. For example, if the preparation in the ascending colon is poor, but the preparation in the remaining colon segments is excellent, the preparation would not, and should not, be considered to be “fair” (or an equivalent numeric sum or average) as an average of all segments. In determining appropriate follow-up intervals (based on adequacy of visualization), it is the fact that one segment was poor that determines the interval—the fact that other colon segments may have been excellently prepped does not mitigate the fact that visualization was definitely impaired in a part of the colon.

One issue requiring further investigation is the appropriate follow-up for an examination with a preparation that cannot be cleared to meet the criterion for “good” (see NHCR preparation descriptions above) but nonetheless is not “poor.” In other words, a preparation leaving the endoscopist with the sense that one or more small lesions may have been missed, but not sufficiently suboptimal to be termed “poor” or “inadequate” and therefore requiring of a <1-year follow-up interval. Studies are beginning to shed light on outcomes within this preparation quality group.18,19 In particular, one study examining NHCR data observed that the ADRs for examinations with bowel preparation rated as fair were similar to those with good or excellent bowel preparation quality.18 Within the NHCR rating, a fair bowel preparation, together with excellent and good, constitute an adequate bowel preparation. However, it remains unclear whether follow-up intervals should be shortened in exams with “suboptimal” bowel preparation quality, regardless of the terminology used to describe them. In a society in which malpractice issues for missed cancers on colonoscopy (potentially arising from missed polyps) are a real concern, more research is needed to reassure endoscopists that a normal examination with a preparation “adequate” to find most polyps > 5 mm, but in which some polyps could quite conceivably have been missed, can reasonably receive a 10-year follow-up recommendation as opposed to a shorter interval. Our investigation of the fair group within this study is intended to clarify current “real world” recommendation practices that are being used by endoscopists for this group.

A few preparation quality classification scales have been in use over the past several years. Despite minor differences, most preparation scales, including the NHCR scale and the more recent but parallel Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS), attempt to assess whether the preparation quality should be considered as excellent, good, fair or poor. An important difference is whether the result is assessed for the worst prepped segment versus the entire colon. The Aronchick Scale (developed in 1994)31,32 rates the entire colon rather than individual segments, using a scale from 1 (excellent) to 5 (inadequate). The Ottawa Scale (developed in 2004)33 offers 5 preparation quality options (0 to 4) for each of 3 defined colon segments, and a rating for fluid in the whole colon (0 to 2), which are added to create the composite score of 0 (excellent) to 14 (very poor). The BBPS (developed in 2009),34 provides descriptions for each of the 4 preparation categories (very similar to the NHCR descriptions outlined above), and for each of 3 colonic segments, assigns numeric scores (0, 1, 2, 3) to represent each of the 4 preparation quality descriptions. For example, the BBPS description “entire mucosa of segment well seen after cleaning,” corresponding to the similar NHCR description, would be termed “excellent” in NHCR criteria and would be equivalent to the label “3” in the BBPS). Another important similarity to the NHCR scale is that the BBPS dictates that the quality of preparation be rated after the colon has been cleared of stool. Recent publications using the BBPS suggest earlier follow up for scores of 0 and 1 in any colon segment,35,36 and therefore follow a similar methodology to the NHCR in that follow-up recommendations are based on the lowest scored segment, rather than an overall average for the entire colon. A 2-category preparation scale, adequate versus inadequate, based on adequacy of the preparation for the detection of lesions > 5 mm, was discussed by the USMSTF in the 2012 guidelines, and in 2007 by the Quality Assurance Task Group of the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable (NCCRT).37 As a parallel, NHCR classifications, designed in 2004, consider excellent, good, and fair as adequate preparations, with poor constituting an inadequate preparation.

Overall, we found fewer fair (6.5%) and poor (1.3%) colonoscopies than are commonly reported (with some other studies reporting fair and poor preparation combined ranging from 22% to 44%),1,7,38–40 although 2 recent studies, one with 6097 screening examinations, reported fair (10.1% to 11.2%) and poor (3.8% to 4.2%) bowel preparation rates, similar to our findings.17,21 The lower rates of fair and poor preparation in NHCR data is likely due to our use of a uniform rating method for bowel preparation, which provides standardized descriptions of the categories and instructs the endoscopist to assess the quality of the worst prepped bowel segment after clearing. The fact that instructions on the NHCR procedure form specifically state that quality assessment should be done after clearing may also have contributed to the lower rates of fair and poor preparations. Nonetheless, it is acknowledged that grading of preparation quality is a subjective assessment, and that the frequency of fair and poor preparations noted in our cohort is at the lowest end of that spectrum. In particular, a significant proportion of endoscopists noted a very low frequency of poor preparations. Endoscopists varied in the percent of the examinations they performed that they considered to be in each bowel prep quality category. In part, this variation may reflect the different preparations in use before split-preparation was clearly shown to be superior in multiple publications since 2005.9,41–46 The USMSTF CRC guidelines recommend that at least 85% of an endoscopist’s colonoscopies have adequate bowel preparation.47 In addition, the Quality Assurance Task Group of the NCCRT indicates that inadequate bowel preparation in > 10% of an endoscopist’s examinations may reflect a quality-control issue for which preparation type and instructions should be reviewed.37

Endoscopists in our study recommended follow-up intervals of <10 years for approximately one-fifth of colonoscopies with fair bowel preparation (20.7%), significantly more than when the bowel preparation was optimal (2.7%). As a result of the preparation being perceived as suboptimal for polyp detection, they may have recommended a shortened follow-up interval to decrease the chance of missing important lesions. Current guidelines do not include clear recommendations for a specific shortened interval following colonoscopies with fair bowel preparation and no findings. Per USMSTF, if the bowel preparation is “fair but adequate (to detect lesions > 5 mm) and if small (< 10 mm) tubular adenomas are detected, follow-up at 5 years should be considered.”5 Fair preparation examinations with no findings are not discussed in recent and previous guideline publications.5,26,48 As a result of the preparation being suboptimal, endoscopists may have recommended a shortened follow-up interval to decrease the chance of missing important lesions; nonetheless, in our study the most common recommendation in the “fair” group was for 10 years. Although fair bowel preparation has been found to impair detection of flat polyps,17 both an NHCR analysis and a recent meta-analysis have strengthened evidence that overall ADR19 and SDR18 may not be affected by fair bowel preparation,49 implying that visualization may not be significantly impaired in colonoscopies with fair bowel preparation. A recent study using repeat colonoscopies to assess the impact of bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates found higher rates of missed adenomas in patients with BBPS scores of 1, but this score, which is defined as “portion of mucosa of the colon segment seen, but other areas of the colon segment not well seen due to staining, residual stool and/or opaque liquid”—the corresponding BBPS picture also demonstrates areas of the mucosa that cannot be seen— would correspond to the NHCR preparation classification of poor, rather than fair.35 Our data add to smaller studies which have presented endoscopists with photographs of colons in various states of cleanliness,14,15 as well as others exploring the impact of bowel preparation quality on actual follow-up recommendations,16,21–23 in finding variable follow-up interval recommendations to be common following colonoscopies with fair bowel preparation.14,15,23 Additional research will help to establish appropriate, evidence-based guidelines for follow-up of colonoscopies with fair preparation.

We found that male endoscopists and surgeons were slightly more likely to report bowel preparation as fair, as were endoscopists with shorter (< 6 min) median withdrawal time in normal colonoscopies. Unlike Thomas-Gibson et al,50 we did not find endoscopist ADR to be associated with assessment of bowel quality (Table 1). In addition, our data confirmed a number of patient characteristics reported by others as associated with fair bowel preparation, including male gender,7,39,51,52 higher BMI,7,38,51 smoking,38,51 lower educational levels,18 and being insured through Medicaid.52 Among patients with fair bowel preparation, shorter intervals were more likely to be recommended to women or non-smokers, and by endoscopists who had an ADR > 20% or who were female. Endoscopists may have chosen to recommend shorter follow-up intervals in their female patients with fair bowel preparation due to increased tortuosity from pelvic surgery and anatomic differences that can make visualization more difficult in women than in men.

In patients with optimal preparation, after adjusting for other co-variates, the only patient or endoscopist factor associated with nonadherent recommended follow-up intervals was patient age (Table 3), with increasing percentage of nonadherent follow-up recommendations for older age groups. The association was the strongest for individuals older than 70 years. Given that the USPSTF recommends against routine CRC screening in patients 76 and older, it is possible that some endoscopists might have shortened the recommended interval in order to enable older patients without comorbidities to have an additional colonoscopy before age 76.53

Limitations of this study include the relatively low number of colonoscopies with poor bowel preparation and the limited racial diversity in our sample. This study has several strengths. To prior studies, we added a substantially larger sample size with greater diversity of both endoscopists and centers, reflecting community and academic practices located in both rural and urban environments. This larger sample size and data on endoscopists allowed us to explore characteristics of both patients and endoscopists associated with recommendation of nonadherent follow-up intervals for exams with optimal and poor bowel preparation quality, and to provide insight into community practice with regard to fair preparations, an area in need of clearer understanding. In addition, endoscopists participating in the prospective data collection of this study were all provided with standardized, clear definitions of preparation categories on the NHCR colonoscopy report form in use for over 10 years, and instructed to assess quality after cleaning.

Bowel preparation has long been recognized as a colonoscopy quality indicator27 which should be routinely measured by every endoscopy practice. It is essential to recognize and address the role of preparation quality in the recommendation of inappropriate follow-up screening and surveillance intervals. Follow-up intervals which are too short increase patient risk and health care expenditures, and intervals that are too long undermine the opportunity for CRC prevention. Our current investigation, including a large number of diverse endoscopists, highlights significant variation from guidelines as a result of suboptimal preparation quality, and notably demonstrates that wider dissemination of national guidelines recommending follow-up in ≤ 1 year in colonoscopies with poor bowel preparation is needed to ensure appropriate screening and surveillance.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Contract # 200-2013-M-57405 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;58:76–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, et al. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;61: 378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radaelli F, Meucci G, Sgroi G, et al. Technical performance of colonoscopy: the key role of sedation/analgesia and other quality indicators. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1122–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;63:S16–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2012;143:844–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, et al. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 63:894–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassan C, Fuccio L, Bruno M, et al. A predictive model identifies patients most likely to have inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10:501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, et al. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1696–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected]. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, et al. Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1296–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bond JH. Should the quality of preparation impact postcolonoscopy follow-up recommendations? Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102: 2686–2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levin TR. Dealing with uncertainty: surveillance colonoscopy after polypectomy. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1745–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rex DK, Bond JH, Feld AD. Medical-legal risks of incident cancers after clearing colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96:952–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Horin S, Bar-Meir S, Avidan B. The impact of colon cleanliness assessment on endoscopists’ recommendations for follow-up colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:2680–2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen M, Hills N, Terdiman J. The impact of the quality of colon preparation on follow-up colonoscopy recommendations. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:2058–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menees SB, Elliott E, Govani S, et al. The impact of bowel cleansing on follow-up recommendations in average-risk patients with a normal colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109:148–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh CH, Lee CK, Kim JW, et al. Suboptimal bowel preparation significantly impairs colonoscopic detection of non-polypoid colorectal neoplasms. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:2294–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson JC, Butterly LF, Robinson CM, et al. Impact of fair bowel preparation quality on adenoma and serrated polyp detection: data from the New Hampshire colonoscopy registry by using a standardized preparation-quality rating. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;80:463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark BT, Rustagi T, Laine L. What level of bowel prep quality requires early repeat colonoscopy: systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of preparation quality on adenoma detection rate. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1714–1723; quiz 1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hillyer GC, Basch CH, Lebwohl B, et al. Shortened surveillance intervals following suboptimal bowel preparation for colonoscopy: results of a national survey. Int J Colorectal Dis 2013;28:73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menees SB, Elliott E, Govani S, et al. Adherence to recommended intervals for surveillance colonoscopy in average-risk patients with 1 to 2 small (< 1 cm) polyps on screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;79:551–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chokshi RV, Hovis CE, Colditz GA, et al. Physician recommendations and patient adherence after inadequate bowel preparation on screening colonoscopy. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58: 2151–2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson MR, Grubber J, Grambow SC, et al. Physician non-adherence to colonoscopy interval guidelines in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Gastroenterology 2015;149:938–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greene MA, Butterly LF, Goodrich M, et al. Matching colonoscopy and pathology data in population-based registries: development of a novel algorithm and the initial experience of the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:334–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butterly L, Robinson CM, Anderson JC, et al. Serrated and adenomatous polyp detection increases with longer withdrawal time: results from the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:417–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, et al. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;80:543–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson JC, Butterly L. Colonoscopy: quality indicators. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2015;6:e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS Institute Inc. SAS 94 System Options: Reference, 4th ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12 College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.le Clercq CM, Bouwens MW, Rondagh EJ, et al. Postcolonoscopy colorectal cancers are preventable: a population-based study. Gut 2014;63:957–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aronchick CA. Validation of an instrument (abstract). Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:2667. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aronchick CA. Bowel preparation scale. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;60:1037–1038; author reply 1038–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rostom A, Jolicoeur E. Validation of a new scale for the assessment of bowel preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;59:482–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, et al. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:620–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark BT, Protiva P, Nagar A, et al. Quantification of adequate bowel preparation for screening or surveillance colonoscopy in men. Gastroenterology 2016;150:396–405; quiz e14–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schoenfeld P, Dominitz JA. No polyp left behind: defining bowel preparation adequacy to avoid missed polyps. Gastroenterology 2015;150:303–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lieberman D, Nadel M, Smith RA, et al. Standardized colonoscopy reporting and data system: report of the Quality Assurance Task Group of the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fayad NF, Kahi CJ, Abd El-Jawad KH, et al. Association between body mass index and quality of split bowel preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:1478–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ness RM, Manam R, Hoen H, et al. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96: 1797–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JS, Kang SH, Moon HS, et al. Impact of bowel preparation quality on adenoma identification during colonoscopy and optimal timing of surveillance. Dig Dis Sci 2015; 60:3092–3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parra-Blanco A, Nicolas-Perez D, Gimeno-Garcia A, et al. The timing of bowel preparation before colonoscopy determines the quality of cleansing, and is a significant factor contributing to the detection of flat lesions: a randomized study. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:6161–6166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rostom A, Jolicoeur E, Dube C, et al. A randomized prospective trial comparing different regimens of oral sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol-based lavage solution in the preparation of patients for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;64:544–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aoun E, Abdul-Baki H, Azar C, et al. A randomized single-blind trial of split-dose PEG-electrolyte solution without dietary restriction compared with whole dose PEG-electrolyte solution with dietary restriction for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;62:213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gurudu SR, Ramirez FC, Harrison ME, et al. Increased adenoma detection rate with system-wide implementation of a split-dose preparation for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;76:603–608. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kilgore TW, Abdinoor AA, Szary NM, et al. Bowel preparation with split-dose polyethylene glycol before colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:1240–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Enestvedt BK, Tofani C, Laine LA, et al. 4-Liter split-dose polyethylene glycol is superior to other bowel preparations, based on systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:1225–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:31–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2017;153:307–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sherer EA, Imler TD, Imperiale TF. The effect of colonoscopy preparation quality on adenoma detection rates. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas-Gibson S, Rogers P, Cooper S, et al. Judgement of the quality of bowel preparation at screening flexible sigmoidoscopy is associated with variability in adenoma detection rates. Endoscopy 2006;38:456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borg BB, Gupta NK, Zuckerman GR, et al. Impact of obesity on bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:670–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lebwohl B, Wang TC, Neugut AI. Socioeconomic and other predictors of colonoscopy preparation quality. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:2014–2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. US Preventive Services Task Force Final Recommendation Statement: colorectal cancer: screening. 2016 Available at: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening2. Accessed August 1, 2018.