Abstract

The current study aimed to conceptually replicate previous studies on the effects of actor personality, partner personality, and personality similarity on general and relational well-being by using response surface analyses and a longitudinal sample of 4,464 romantic couples. Similar to previous studies using difference scores and profile correlations, results from response surface analyses indicated that personality similarity explained a small amount of variance in well-being as compared to the amount of variance explained by linear actor and partner effects. However, response surface analyses also revealed that second-order terms (i.e., the interaction term and quadratic terms of actor and partner personality) were systematically linked to couples’ well-being for all traits except neuroticism. In particular, most response surfaces showed a complex pattern in which the effect of similarity and dissimilarity on well-being depended on the level and combination of actor and partner personality. In addition, one small but robust similarity effects was found, indicating that similarity in agreeableness was related to women’s experience of support across the eight years of the study. The discussion focuses on the implications of these findings for theory and research on personality similarity in romantic relationships.

Keywords: Big Five, Well-Being, Romantic Relationships, Response Surface Analysis

Romantic partners tend to be more similar in certain personality characteristics than would be expected by chance (Humbad, Donnellan, Iacono, McGue, & Burt, 2010; McCrae et al., 2008; Watson et al., 2004). This finding has led to much speculation regarding the origins and consequences of spousal similarity and dissimilarity. Research on the consequences of similarity has focused on the question whether similar romantic couples are happier than dissimilar romantic couples. Overall, the findings of this research suggest that the effects of personality trait similarity on both individual and relational well-being are small or negligible (e.g., Barelds, 2005; Dyrenforth, Kashy, Donnellan, & Lucas, 2010; Gaunt, 2006). However, past studies might not have been ideally suited to detect the effects of personality similarity on well-being, producing biased or incomplete results (Edwards, 1994; Griffin, Murray, & Gonzalez, 1999).

In the current study, we conceptually replicate previous research by using response surface analysis (RSA), an approach that can provide a more rigorous test of the link between personality similarity and well-being (Edwards, 1993) than approaches that have previously been used (i.e., difference scores and profile correlations, Dyrenforth et al., 2010). Below, we first review the state of past research on the consequences of personality similarity on relational and general well-being among couples including the most important methodological limitations of this work. We then explain the ways in which longitudinal dyadic data in combination with RSA can be used to overcome some of the limitations of previous studies. Finally, we will apply this approach to examine general and relational well-being correlates of spousal similarity in Big Five personality traits in a large sample of older couples followed over an eight-year period.

Past Research on the Effects of Personality Effects on Well-being within Couples

Romantic relationship research has mostly focused on the implications of a person’s own personality (i.e., “actor” effects) and the personality of their romantic partner (i.e., “partner” effects) for individuals’ or couples’ well-being. This research has shown that well-being is associated with both actor and partner personality. The positive effects are most consistent for low neuroticism, high agreeableness, and high conscientiousness in both individuals and their partners, with partner effects being usually smaller in size (Dyrenforth et al., 2010; Furler, Gomez, & Grob, 2013; Malouff, Thorsteinsson, Schutte, Bhullar, & Rooke, 2010). For example, past research suggests that agreeable partners are more prone to engage in positive daily interactions, which may have a positive effect on an individual’s well-being, over and above their own level of agreeableness (Donnellan, Conger, & Bryant, 2004). Furthermore, studies usually find little evidence for gender differences in actor and partner effects of personality (e.g., Dyrenforth et al., 2010).

In addition to actor and partner effects, several social psychological theories have suggested that similarity in personal characteristics may impact a person’s well-being (Burleson, Kunkel, & Birch, 1994; Byrne, 1961; Duck, 1991). Similarity has been theorized to foster relational and general well-being because it may increase people’s ability to understand and empathize with their partners’ behaviors, intentions, and motivations (Anderson, Keltner, & John, 2003). Specifically, researchers have argued that similar spouses are likely to understand each other better, which could lead to more enjoyable and successful daily interactions and in turn higher relationship satisfaction (Burleson et al., 1994; Karney & Bradbury, 1995). Also, developing relationships with similar partners might be more pleasant because similar partners are more likely to mirror and thus validate a person’s own views and actions (Byrne & Nelson, 1965; Swann, 2011). Having a similar relationship partner may thus reduce uncertainty and anxiety, fostering coherence in views about the self, the romantic relationship, and the world. These processes might then eventually lead to increases in both relational and general well-being.

Early studies have mainly focused on similarity in attitudes, values, and interests as potential determinants of interpersonal attraction and success in social relationships (e.g. Newcomb, 1956; Byrne & Nelson, 1965). More recently, researcher have proposed similar positive effects for personality traits (e.g., Byrne, Griffitt, & Stefaniak, 1976; Botwin, Buss, & Shackelford, 1997). In addition, several researchers have argued that similarity effects may be stronger for some traits than for others. For example, McCrae and colleagues (e.g., McCrae, 1996; McCrae et al., 2008; McCrae & Sutin, 2009) have emphasized the role of similarity in openness to experience in close relationships, because this trait is strongly linked to how people organize their views and attitudes towards various life domains, such as religion and family (Dollinger, Leong, & Ulicni, 1996; McCrae, 1996; McCrae & Sutin, 2009). Others have argued that similarity effects might be especially pronounced for extraversion and agreeableness, because these traits are strongly associated with individual differences in interpersonal behavior. Particularly, similarity in extraversion and agreeableness are associated with similarity in interaction styles, which might lead to more enjoyable interactions, and enhance the predictability of interaction partners (Selfhout et al., 2010; van Zalk & Denissen, 2015). Similarity in these traits may therefore contribute to well-being in social relationships. To conclude, all the theories mentioned above predict that similarity in personality traits is beneficial for both individuals’ and couples’ well-being – even though they emphasize different mechanisms that may produce this effect.

However, virtually all previous studies on personality similarity have failed to support this prediction. In two meta-analyses, the effects of personality similarity on attraction and satisfaction in various types of relationships (Malouff et al., 2010; Montoya, Horton, & Kirchner, 2008) were small and inconsistent across studies. Specifically, Montoya et al. (2008) found some personality similarity effects on attraction when people met for the first time, but no or only negligible similarity effects on attraction and satisfaction in established relationships. Malouff et al. (2010) examined personality similarity effects on relationship satisfaction in long-term romantic relationships. Using data from eight samples, they found that out the 39 possible associations examined, only 6 associations were in the direction of similarity, with similarity effects equally spread over all Big Five traits.

Not included in these meta-analyses were two more recent cross-sectional studies that used large representative samples of German, Australian, British (Dyrenforth et al., 2010) and Swiss adults (Furler et al., 2013). Including more than 11,000 couples, the total sample size of the Dyrenforth et al. (2010) study was almost 10 times larger than the total sample size of the eight samples included in the meta-analysis of Malouff et al. (2010). Consistent with previous meta-analytic results, Dyrenforth et al. (2010) found that, compared to actor and partner effects, the effect sizes for overall personality similarity (i.e., average similarity across the Big Five traits) on relationship satisfaction and life satisfaction were relatively small. In addition, follow-up analyses for trait-specific personality similarity effects (e.g., similarity in conscientiousness specifically, etc.) did not show a consistent pattern of effects on well-being across the different samples. Furler et al. (2013) also studied similarity effects of personality on general well-being in 1,608 Swiss couples. Only one similarity effect was found, indicating that similarity in agreeableness was related to lower general well-being. However, the authors concluded that the effect was small and its statistical significance was likely attributable to chance.

In summary, although there are theoretical arguments for the claim that similar couples are happier than dissimilar couples, past research has found little support for this hypothesis. Overall, reported effects of personality similarity on relationship satisfaction and general well-being have been small, especially compared to actor and partner effects of personality. Yet, the similarity measures used in most previous studies might have not been ideally suited to examine the link between personality similarity and well-being. Next, we discuss how two of the most frequently used measures of similarity have limited the study of personality similarity effects on well-being.

Measurement of Similarity Effects

How to accurately measure similarity effects has been the subject of long-standing debate (e.g., Dyrenforth et al., 2010; Edwards, 1993; Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Weidmann, Ledermann, & Grob, 2017). To date, empirical studies have mainly relied on two measures to study similarity effects: profile correlations and difference scores (e.g., Dyrenforth et al., 2010; Furler et al., 2013). Difference scores reflect the discrepancy between both partners’ personalities and are usually calculated by taking either the absolute or squared difference between the partners’ personality scores on a given trait. In addition, the average of these difference scores can be used as indicator of overall discrepancy across all Big Five traits. In this way, partners with very dissimilar personalities would have high difference scores; partners with similar personalities would have scores close to zero. Profile correlations are related to this approach and capture the degree to which partners have a similar pattern of responses across a given number of personality traits. A positive correlation would indicate similarity in low vs. high scores on traits. For example, if both romantic partners have higher scores on conscientiousness than extraversion, this would contribute to a more positive personality profile correlation (Furr, 2008). Comparing these two approaches to measure similarity, Dyrenforth et al. (2010) and Furler et al. (2013) found that, when main effects (i.e., actor effects andpartner effects) and other possible confounding effects (e.g., the degree to which the results match average or “stereotypic” responses; Wood & Furr, 2016) were properly controlled for, profile correlations and difference scores yielded similar results, in that similarity effects were much smaller compared to actor and partner effects and usually not statistically significant.

Even after controlling for main effects and stereotypic responses, difference scores and profile correlations still have several methodological and interpretative issues (for an overview of these issues, please see Edwards, 1993, 1994; Griffin et al., 1999). One of the most important limitations of both difference scores and profile correlations is that they assume one model (i.e., absolute similarity) without considering the fit of alternative models (Edwards, 1993; Nestler, Grimm, & Schönbrodt, 2015). Past research on personality similarity effects have typically compared models of main effects and absolute similarity with a model including only main effects (Dyrenforth et al., 2010; Furler et al., 2013; Hudson & Fraley, 2014; Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies examining Similarity Effects of Self-Reported Big Five Personality Traits using APIM, and adding either Difference Scores, Profile Correlations, or Second-Order Polynomial Regression Coefficients

| Authors (Year) | Sample |

N couples |

Married | Age | Longitudinal design | Outcome | Similarity Measure | Similarity Effect?a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyrenforth et al. (2010) | HILDA (Australia) | 2,639 | 100% | Mmale = 50.96; Mfemale = 48.49 | no | GWB (1 item) | DS | yes, +extraversion (p < .05), and +neuroticism (p < .05) |

| GWB (1 item) | PC | no | ||||||

| RWB (1 item) | DS | yes, +extraversion (p <.01), +openness (p <.01), and +mean similarity (p < .01) | ||||||

| RWB (1 item) | PC | yes +PC (p < .01) | ||||||

| BHPS (UK) | 3,277 | 100% | Mmale = 51.67; Mfemale = 49.42 | no | GWB (1 item) | DS | yes, -agreeableness (p < .05), and +neuroticism (p < .01) | |

| GWB (1 item) | PC | no | ||||||

| RWB (1 item) | DS | yes, +neuroticism (p < .05) | ||||||

| RWB (1 item) | PC | no | ||||||

| GSOEP (Germany) | 5,709 | 100% | Mmale = 53.7; Mfemale = 51.0 | no | GWB (1 item) | DS | yes, +agreeableness (p < .01) | |

| GWB (1 item) | PC | no | ||||||

| Furler et al. (2013)b | SHP (Switzerland) | 1,608 | 100% | Mmale = 51.88, Mfemale= 49.10 | no | GWB (1 item) | DS | yes, -agreeableness (p < .01) |

| GWB (1 item) | PC | no | ||||||

| Hudson & Fraley (2014)c | Community sample (USA) | 174 | 0% | M = 20.37 | 5 time-points across 1 year | RWB (5 items) | DS | yes, +agreeableness (p < .05) |

| RWB (5 items) | Squared DS | yes, -neuroticism (p < .01) | ||||||

| Weidmann et al. (2017) | CoDip (Switzerland) | 237 | 70.9% | Mmale = 50.7; Mfemale = 48.4 | 2 time-points across 2 years | RWB (7 items) | PR + RSA | no |

| 141 | Change in RWB | PR + RSA | yes, +openness for women |

Note. We only reported studies that (1) controlled for actor and partner effects, and (2) controlled for the dyadic nature of the data (i.e., used an actor- partner- interdependence model). RWB = Relational Well-Being GWB = General Well-Being; DS = absolute Difference Score; PC = Profile Correlation, measured using standardized intra-class correlation across all Big Five traits; RSA = Polynomial Regression and Response Surface Analysis ; HILDA = Household Income and Labor Dynamics in Australia; BHPS = British Household Panel Study; HRS = Health and Retirement Study; GSOEP = German Socio-Economic Panel Study; SHP = Swiss Household Panel; CoDip = Co-Development in Personality Study.

A positive effect indicates that similarity is positively related to GWB or RWB.

In addition to absolute difference scores and standardized ICC, Furler et al. also tested the effect of variance similarity (i.e., absolute value of difference between the variances across all traits within the profiles) on general well-being, and found no significant effects.

The results represent effects on well-being across all time points. Hudson and Fraley also tested if people had higher relational well-being at time-points where they were more similar in personality, and found no significant effects.

The problem with this approach is that the impact of similarity and dissimilarity might depend on the combination of actor and partner effects of personality. For example, for someone low in conscientiousness, having a partner high in conscientiousness might lead to higher well-being compared to having equally low scores (Roberts, Smith, Jackson, & Edmonds, 2009). In social interactions, having opposite levels on certain traits, but equal levels on other traits might work better (e.g., Carson, 1969; Wiggins, 1979; Markey & Markey, 2007). In other words, complementarity might matter more than similarity as suggested by Carson (1969) and others who argued that two people may complement each other when they have equal levels of warmth, but opposite levels of dominance. Even for a single trait, both similarity and complementarity might contribute to well-being in romantic relationships, resulting in moderate levels of similarity leading to optimal well-being (Hudson & Fraley, 2014). Because difference scores and profile correlations treat actor personality, partner personality, and personality similarity as three separate linear predictors, they cannot adequately examine how each combination of actor and partner personality traits relate to well-being.

As an alternative to difference scores and profile correlations, studies in personality and social psychology have recently begun to use polynomial regression in combination with RSA to answer a variety of questions about fit and similarity (e.g., Bleidorn et al., 2016; Denissen et al., 2017; Weidmann, Schönbrodt, Ledermann, & Grob, 2017). Most importantly, polynomial regression does not posit linear constraints on actor, partner, and personality effects but can also examine quadratic effects (Edwards, 1993; Nestler, Grimm, & Schönbrodt, 2015). Related to our research question, RSA further allows to test how matches and mismatches at all levels of personality traits relate to individuals’ well-being. In addition, RSA allows to visualize fit patterns between couples and their implications for well-being in a three-dimensional response surface plot (Shanock et al., 2010).

To the best of our knowledge, only one study applied RSA on cross-sectional (n = 237) and 2-wave longitudinal (n = 141) data from romantic couples to study effects of personality similarity on men’s and women’s relationship satisfaction (Weidmann, Schönbrodt, et al., 2017). In the cross-sectional analysis, Weidmann, Schönbrodt, et al. found no significant effects of personality similarity on relationship satisfaction. Controlling for relationship satisfaction at the first assessment wave, one similarity effect emerged when predicting relationship satisfaction two years later. That is, moderate levels of similarity in openness to experience predicted higher relationship satisfaction in women. Yet, due to relatively small sample sizes, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. Specifically, Weidmann, Schönbrodt, et al. (2017) reported that they only had 41% power to detect small effects (i.e., β = 0.10) in the cross-sectional sample. Power was even more limited in the longitudinal sample because of reduced sample size (n = 141). To be able to reliably detect small (but possibly meaningful) similarity effects, large, longitudinal samples of couples with sufficient statistical power are needed.

The Current Study

The primary goal of the current study was to examine if the findings from previous research on personality similarity and well-being in romantic relationships replicate when using polynomial regression and RSA. We specifically focused on the conceptual replication of recent studies on Big Five personality similarity that controlled for actor and partner effects and took into account the interdependence of romantic partners (see Table 1, for an overview of these studies). Compared to past RSA research on personality similarity effects (Weidmann, Schönbrodt, et al., 2017), we used a substantially larger sample of 4,464 couples (mean age 66.72, SD = 9.47) which granted us sufficient statistical power to detect even small similarity effects (see method section for a power analysis). Furthermore, we rigorously tested the robustness of personality similarity effects using three measurements of well-being across an 8-year period. If similarity effects would replicate across different time-intervals, this would give an indication that these small effects might still be meaningful.

Based on the results of the studies described in Table 1, we expected very small effects of personality similarity and small to moderate associations between low neuroticism, high agreeableness, and high conscientiousness in both actors and partners on general and relational well-being (Dyrenforth et al., 2010; Furler et al., 2013; Malouff et al., 2010). Furthermore, we expected the effects of actor and partner personality traits on general and relational well-being to generalize across gender and measurement waves.

Method

Sample and Procedure

The current study made use of publicly available de-identified data. Therefore, the current study’s analyses were considered exempt by Michigan State University’s Institutional Review Board.

Data came from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative panel study that started in 1992, and has surveyed more than 22,000 Americans aged 50+ every two years (Sonnega et al., 2014).1 The University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research is responsible for the study and provides extensive documentation about the protocol, instrumentation, sampling strategy, and statistical weighting procedures.

In 2006, 50% of the HRS respondents were randomly selected and then visited for an extended face-to-face interview (Cohort 1). In 2008, the remaining 50% of the HRS respondents were visited for an extended face-to-face interview (Cohort 2). After the interview, respondents completed a self-report questionnaire that measured various psychological constructs. This questionnaire was re-administered every four years. Specifically, the psychological questionnaires were completed in 2006 (Wave 1), 2010 (Wave 2), and 2014 (Wave 3) for Cohort 1, and in 2008 (Wave 1), and 2012 (Wave 2) for Cohort 2. The two cohorts were combined into one sample for the present analyses to increase statistical power and precision.

To be able to apply similar types of models as used in previous studies (i.e., models for distinguishable dyads), we first selected data from all households including heterosexual couples. Furthermore, we only included couples of which both partners provided data at Wave 1, resulting in a total sample size of 8,928 individuals (4,464 couples). Ethnicity was 86.8% white, 8.8% black, and 4.4% other. Table 2 shows the sample sizes and descriptive statistics of all study variables (including the control variables age, relationship length and education level) across the three measurement waves. The final sample differed from the broader sample (i.e., including households that provided data from only one individual), but these differences were mostly small. Specifically, compared to the broader HRS sample, the current sample was less agreeable (d = .09), more conscientious (d = .08), more open to experience (d = .05), higher in general well-being (d = .34), reported more support from their spouses (d = .58), and felt less strain from their spouses (d = .10). Thus, our results may be biased towards romantic couples with somewhat higher levels of general and relational well-being.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Sample Sizes across Measurement Waves

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Outcome Variables | |||

| General Well-Being | 3.71 (0.91) | 3.65 (0.94) | 3.71 (0.91) |

| Relational Strain | 1.97 (0.67) | 1.92 (0.65) | 1.90 (0.65) |

| Relational Support | 3.50 (0.60) | 3.51 (0.61) | 3.51 (0.62) |

| Predictors | |||

| Extraversion | 3.20 (0.56) | – | – |

| Neuroticism | 2.06 (0.61) | – | – |

| Agreeableness | 3.51 (0.49) | – | – |

| Conscientiousness | 3.36 (0.48) | – | – |

| Openness | 2.94 (0.55) | – | – |

| Age (years) | 66.72 (9.47) | – | – |

| Marriage Length (years) | 37.15 (16.06) | – | – |

| Years of Education | 12.79 (3.06) | – | – |

| N | N | N | |

| Number of Individuals | 8,928 | 7,652 | 3,529 |

Note. Predictors were only measured at Wave 1. Wave 1 and Wave 2 were assessed for both cohorts, and Wave 3 was only assessed for Cohort 1.

From the final sample, 6,820 (76.4%) individuals provided data for at least two waves. Compared to people that participated in only one wave (n = 2,108 individuals), participants with at least two waves were more extraverted (d = .15), less neurotic (d = 0.13), more agreeable (d = .12), more conscientious (d = .26), more open to experience (d = .15), higher in general well-being (d = .14), felt less strain from their spouses (d = .09), were younger (d = .38), in shorter relationships (d = .15), and had completed more years of education (d = .36).

Measures

Big Five personality

Personality was assessed at Wave 1 using the Midlife Development Inventory personality scales (Lachman & Weaver, 1997). These scales contained Big-Five adjectives selected from various personality measures, such as Goldberg’s (1992) Big-Five markers. Participants were asked to which extent each of 26 adjectives described them on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot). The groups of adjectives were: calm (reverse coded), moody, worrying, nervous (for neuroticism; α = .71); outgoing, friendly, lively, active, talkative (for extraversion; α = .75); creative, imaginative, intelligent, curious, broad-minded, sophisticated, adventurous (for openness to experience; α = .79); organized, responsible, hardworking, careless (reverse coded), thorough (for conscientiousness; α = .67); helpful, warm, caring, softhearted, sympathetic (for agreeableness; α = .78). Responses to each adjective were averaged to yield a composite for each trait.

General well-being

General well-being was assessed with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with each of five items: “In most ways my life is close to ideal”, “The conditions of my life are excellent”, “I am satisfied with my life”, “So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life”, and “If I could live my life again, I would change almost nothing”. Answers were provided on a converted scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Responses were averaged to yield a composite scale tapping into general well-being (α = .89).

Support

Three items assessed the extent to which someone felt supported by their spouse; “How much do they (i.e., the spouse) really understand the way you feel about things?”, “How much can you rely on them if you have a serious problem?”, and “How much can you open up to them if you need to talk about your worries?” Participants responded to each question on a scale ranging from 1 (a lot) to 4 (not at all). We reverse scored and averaged responses to yield a composite scale for spousal support (α = .89).

Strain

Four items measured the amount of strain that someone experienced in the spousal relationship: “How often do they (i.e., the spouse) make too many demands on you?”, “How much do they criticize you?”, “How much do they let you down when you are counting on them?”, and “How much do they get on your nerves?”. Participants responded to each question on a scale ranging from 1 (a lot) to 4 (not at all). We reverse scored and averaged responses to yield a composite score for spousal strain (α = .78). Although the support and strain questions were embedded within the same questionnaire, confirmatory factor analyses suggest that they indeed form two separate constructs (Chopik, 2017).

For Cohort 1, the outcome variables (general well-being, relational support, and relational strain) were assessed in 2006, 2010, and 2014. For Cohort 2, the outcomes were assessed in 2008 and 2012.

Analytic Approach

We used multilevel polynomial regression and response surface analyses (Edwards, 2002) to examine the link between personality similarity and well-being. The multilevel polynomial regression models were estimated using the mixed procedure in IBM SPSS statistics version 22 (IBM Corp, 2013). Response surface analyses were conducted using the RSA package version 0.9.11 (Schönbrodt, 2016a) in R (R Core Team, 2017). We used maximum likelihood (ML) estimators, which handle missing data better than traditional methods (e.g., listwise deletion) by using all available data-points across the three longitudinal measurement waves to estimate the regression parameters. ML gives unbiased variance estimates when large samples are used (Pinheiro & Bates, 2000), and is recommended when comparing multilevel models that differ only in fixed effects (Nakagawa & Schielzeth, 2013).

The SPSS syntax of the multilevel polynomial regression model is included in the supplemental materials. In all models, we included three control variables: age, years of marriage, and years of education. First, even though most participants were older than 50 years, age might still play a role in explaining participants’ well-being (e.g., because of declining health in older ages; Mueller et al, 2017). We included years of marriage and years of education as both of these variables have been found to be associated with couples’ general and relational well-being (e.g., Vanlaningham, Johnson & Amato, 2001; Diener, Sandvik, Seidlitz, & Diener 1993). Gender was contrast-coded (−1 = men, 1 = women) and age, relationship length and years of education were grand-mean centered. To facilitate interpretation of the response surface plots, personality traits were standardized using the means and standard deviations of the broader HRS sample (i.e., additionally including households that provided data from only one individual). Interpersonal and relational well-being outcomes were standardized and served as the dependent measures and were allowed to vary across time points; the linear effect of measurement wave was included in each analysis. The control variables, actor personality, and partner personality were treated as time-invariant predictors of well-being. We also conducted a series of moderation tests examining gender differences and the robustness of personality similarity effects across measurement wave.

To examine the role of actor personality, partner personality, and personality similarity, we added the polynomial regression parameters to the actor-partner interdependence model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006):

In this equation, well-being (i.e., general well-being, support, or strain) was predicted by actor personality Xactor, partner personality Ypartner, their interaction term XactorYpartner, and their quadratic terms Xactor2 and Ypartner2 (Schönbrodt, 2016). The three second-order terms (Xactor2, XactorYpartner, and Ypartner2) together can reflect similarity effects, which can be tested when using RSA. For each of the three outcomes, an initial model (the APIM) fit was compared to a full polynomial model, where the second-order terms Xactor2, XactorYpartner, and Ypartner2 were added.

The APIM and polynomial model were compared for models including all Big Five traits simultaneously and for models including each of the five personality traits separately. Model fit comparisons were made by using the Akaike information criterion (AIC). A better model fit was indicated by a decrease in AIC that was larger than 2 (Burnham & Anderson, 2004). An improvement in model fit would justify the examination of possible similarity effects by using RSA.

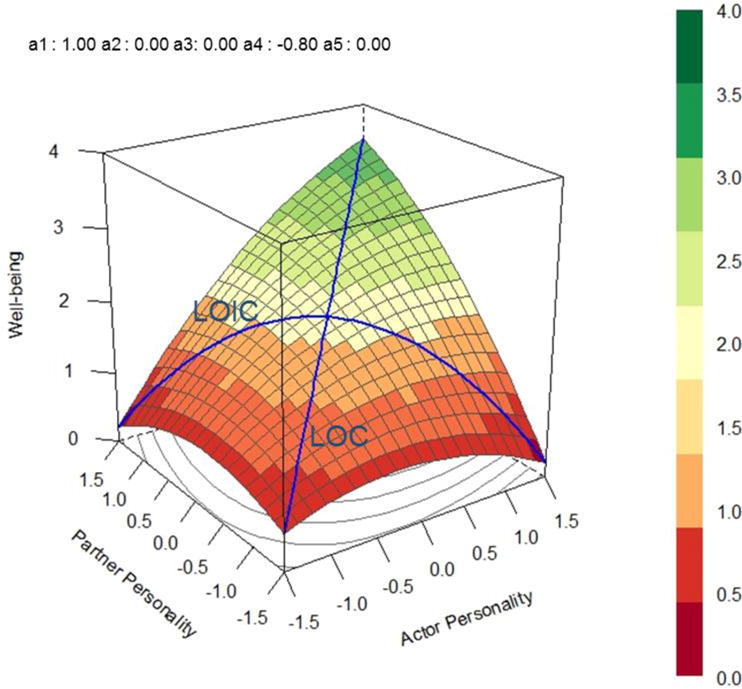

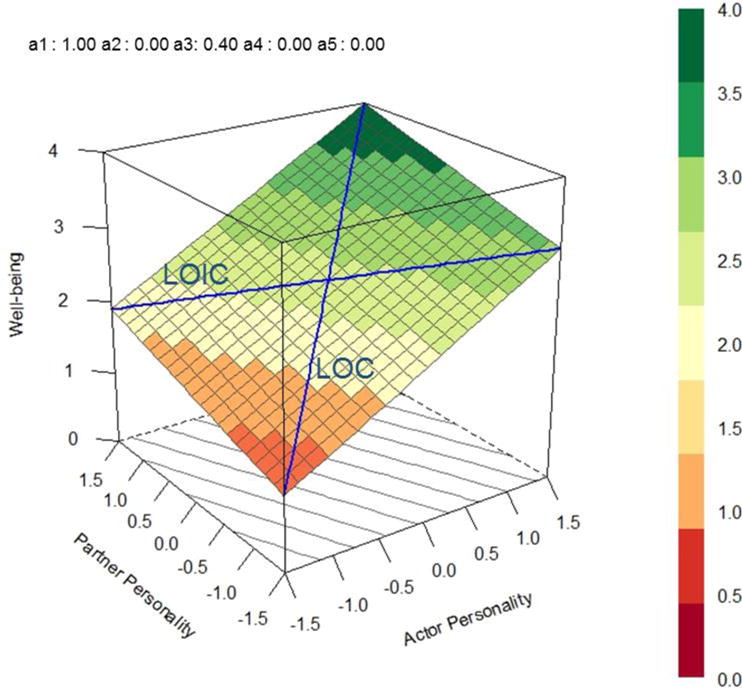

The regression coefficients from the full polynomial model were used to create a response surface plot (Schönbrodt, 2016), which specified the level of well-being (vertical axis, Z) for each combination of actor and partner personality (the two horizontal axes, X and Y), resulting in a three-dimensional response surface (Edwards, 2002). In these response surfaces (see Figures 1 and 2), the blue line that runs from the front corner to the back corner of the cube is called the line of congruence (LOC). This line contains all congruent combinations (i.e., where Xactor = Ypartner, such that couple members are similarly high or low in a trait). The blue line that runs from the left to the right corner of the cube is called the line of incongruence (LOIC). The LOIC is the line of personality combinations where actor and partner personality are equal in magnitude but opposite in sign (i.e., Ypartner = -Xactor). The midpoint of the LOIC represents couples with a similar personality (i.e., where the LOIC crosses the LOC). Moving along the LOIC to the right or left (i.e., away from the midpoint), actor and partner personality become more dissimilar.

Figure 1.

Example of response surface reflecting a combination of positive main effects actor and partner personality that are equal in size, and a positive personality similarity effect on well-being. LOC = line of congruence; LOIC = Line of incongruence.

Figure 2.

Example of response surface reflecting positive main effects of actor and partner personality on well-being, with actor effects larger than partner effects, and no personality similarity effects. LOC = line of congruence; LOIC = Line of incongruence

Support for a similarity effect on well-being should be reflected in the response surface parameters a1 (b1 + b2), a2 (b3 + b4 + b5), a3 (b1 – b2), a4 (b3 – b4 + b5), and the more recently introduced parameter a5 (b3 – b5; Nestler, Humberg, & Schönbrodt, 2017). The third and fourth parameter determine the shape of the LOIC (b0 + a3X + a4X2). Specifically, a4 indicates if there is a curvilinear effect along the LOIC, suggesting an optimal level of well-being. Furthermore, if a4 is significant, a3 indicates at which point of the LOIC this optimal level is reached. The first and the second parameter determine the shape of the LOC (b0 + a1X + a2X2). Conceptually, a1 and a2 reflect linear and curvilinear main effects of actor and partner personality. If a4 is significant, a1 and a2 indicate if optimal levels of well-being differ for low versus high scores on a trait. Finally, a5 indicates the position of the ridge line of the surface, locating partners’ personality combinations associated with optimal levels of well-being.

In view of the large body of evidence for actor and partner personality effects on well-being, a1 was allowed to differ from zero (see also Humberg, Nestler, & Back, in press). In addition, these main effects were allowed to be nonlinear (i.e., a2 ≠ 0). If a1 or a2 would differ from zero, this would indicate that, because of main effects, similarity effects might depend on the level actor and partner personality (i.e., linear or curvilinear effects along the LOC). As such, our definition of similarity is similar to what Humberg et al. (in press) described as congruence effects in a broad sense as opposed to strict congruence effects. The latter would be indicated if similarity effects were relevant over and above the level of actor and partner effects. To establish a similarity effect, the remaining parameters should meet the following conditions: a3 and a5 should be zero, and a4 should be negative (Edwards, 2002; Humberg et al., in press; Nestler et al., 2017).

The response surface that meets these conditions for similarity is visualized in Figure 1. In the hypothetical Figure 1, the LOC matches the ridge line containing the highest levels of well-being (a5 = 0). This indicates that that similarity is best at high levels of a personality trait because of additional linear main effects of actor and partner personality (a1 > 0). Furthermore, well-being is highest at the midpoint of the LOIC (when actor and partners are least dissimilar), compared to lower scores when moving to the left or right along the LOIC, when actor and partner personality become more dissimilar (a4 < 0; a3 = 0).

If the conditions for similarity are not met, the response surface could take several alternative shapes. If we find a response surface similar to the hypothetical Figure 2, this would indicate a model with only main effects from the actor and partner (a1 > 0), actor effects larger than partner effects, and no similarity effects (a3 > 0, and a4 = 0). Furthermore, there might be scenarios in which well-being levels might be comparable between couples that are perfectly similar in personality and couples that show some moderate degree of dissimilarity. Specifically, if a3 differs from zero, this would mean that well-being is highest when actor and partner differ to a certain extent. If a4 is zero, there would be no ridge line containing optimal combinations of actor and partner personality. This means that well-being does not decrease when actor and partner personality become more dissimilar (i.e., the LOIC is linear). If a5 deviates from zero, the ridge line would be shifted or rotated away from the LOC. This would suggest that, instead of having similar levels on a certain trait, it might more beneficial to have a partner with different scores.

Power Analysis

To the best of our knowledge, no specific tool exists for estimating the statistical power in studies of dyadic polynomial regressions. Similar to Weidmann, Schönbrodt, et al. (2017), we therefore used a program developed by Ackerman and Kenny (2016) to determine the sample size needed to detect small and moderate effects when using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. Based on previous research (Table 1), we expected actor effects to be small to medium in size (i.e., β ~ 0.15), and partner effects to be small (i.e., β ~ 0.10). To reliably determine small effects at an alpha level of .01, we would need a sample size of 563 couples. In our sample of 4,464 couples, we had more than 99% power to detect actor and partner effects, even when only examining these effects cross-sectionally at T1.

Because only one previous study (Weidmann, Schönbrodt, et al., 2017) has used RSA to examine personality similarity effects in romantic relationships, we could not reliably estimate the expected effect size of similarity effects. Therefore, we followed the guidelines for determining sample size when examining interaction effects. Aiken and West (1991) recommend a sample size that is 2 to 3 times larger than would be needed when testing main effects, indicating a sample size of 1,659 couples (i.e., three times the sample size needed to study small partner effects of β ~ 0.10) to study interactions. To additionally check the robustness of possibly very small similarity effects, we also tested if personality effects replicated across the three longitudinal time points, optimizing power by using multilevel modeling and ML to handle missing data.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 3 shows the zero-order correlations between all personality and well-being variables for men (lower diagonal) and women (upper diagonal). Big Five personality traits were correlated with each other for both men and women (rs range from |.15| to |.61|). Each of the personality traits was also significantly and positively correlated within couples (similarity), and these correlations were small (rs range from |.07| for extraversion to |.25| for openness to experience). The correlations of actor and partner personality traits with the outcomes replicated established findings (e.g., DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Dyrenforth et al., 2010). Each of the well-being outcomes was also correlated in expected directions (e.g., strain was negatively correlated with general well-being and support).

Table 3.

Correlations between Big Five Personality Traits, General Well-Being, Strain and Support

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Actor Extraversion | .07** | −.24** | −.09** | .55** | .10** | .40** | .14** | .54** | .15** | .26** | −.09** | .17** | |

| 2. Partner Extraversion | .07** | −.08** | −.24** | .10** | .61** | .14** | .41** | .10** | .54** | .12** | −.10** | .15** | |

| 3. Actor Neuroticism | −.24** | −.09** | .17** | −.15** | −.08** | −.26** | −.10** | −.23** | −.08** | −.31** | .27** | −.21** | |

| 4. Partner Neuroticism | −.08** | −.24** | .17** | −.07** | −.20** | −.11** | −.28** | −.09** | −.21** | −.15** | .21** | −.17** | |

| 5. Actor Agreeableness | .61** | .10** | −.20** | −.08** | .14** | .44** | .15** | .41** | .13** | .17** | −.08** | .12** | |

| 6. Partner Agreeableness | .10** | .55** | −.07** | −.15** | .14** | .13** | .44** | .11** | .46** | .12** | −.16** | .19** | |

| 7. Actor Conscientiousness | .41** | .14** | −.28** | −.10** | .44** | .15** | .16** | .43** | .19** | .24** | −.12** | .15** | |

| 8. Partner Conscientiousness | .14** | .40** | −.11** | −.26** | .13** | .44** | .16** | .14** | .50** | .18** | −.17** | .21** | |

| 9. Actor Openness | .54** | .15** | −.21** | −.08** | .46** | .13** | .50** | .19** | .25** | .17** | −.04** | .12** | |

| 10. Partner Openness | .10** | .54** | −.09** | −.23** | .11** | .41** | .14** | .43** | .25** | .13** | −.08** | .17** | |

| 11. General Well-Being | .27** | .10** | −.32** | −.16** | .21** | .07** | .25** | .12** | .19** | .08** | −.37** | .38** | |

| 12. Strain | −.08** | −.06** | .26** | .18** | −.13** | −.11** | −.16** | −.12** | −.04* | −.05** | −.27** | −.59** | |

| 13. Support | .21** | .11** | −.20** | −.16** | .24** | .13** | .22** | .15** | .18** | .10** | .33** | −.47** |

Note. Men are in lower diagonal. Women are in upper diagonal.

p < .05

p < .01

Difference Score Analysis

To provide a more direct replication of the study by Dyrenforth et al. (2010), we first examined (dis)similarity effects operationalized as absolute difference scores. Table 4 shows the effect sizes (i.e., standardized regression coefficients and explained variance) of these analyses next to the effect sizes reported in Dyrenforth et al. (2010). We found that, of the 15 models examined, 11 models showed a significant similarity effect (i.e., p < .01). The four models that were not significant were similarity in neuroticism predicting all three outcome measures, and similarity in agreeableness predicting general well-being. The effect sizes the current study were highly similar to those reported in Dyrenforth et al. (i.e., differences in standardized regression coefficients were ≤ .10).

Table 4.

Effect Sizes of Actor Personality, Partner Personality, Difference Scores, and Second-Order Polynomial Regression Coefficients of Self-Reported Big Five Traits Predicting GWB, RWB, Strain and Support

|

Dyrenforth et al. (2010)

|

Current Study

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Outcome | HILDA GWB |

HILDA RWB |

BHPS GWB |

BHPS RWB |

GSOEP GWB |

HRS GWB |

HRS Strain |

HRS Support |

|

| Predictor | Standardized regression coefficients | ||||||||

| Extraversion | Actor Personality | .19** | .12** | .13** | .08** | .13** | .24** | −.07** | .15** |

| Partner Personality | .10** | .08** | .02 | .01 | .08** | .08** | −.06** | .08** | |

| DS | −.03* | −.06** | .00 | .00 | −.01 | −.04** | .04** | −.04** | |

| Neuroticism | Actor Personality | −.26** | −.18** | −.34** | −.11** | −.26** | −.26** | .23** | −.16** |

| Partner Personality | −.12** | −.15** | −.10** | −.07** | −.12** | −.09** | .14** | −.11** | |

| DS | .03* | −.01 | .04** | .03* | .01 | −.01 | .00 | −.03* | |

| Agreeableness | Actor Personality | .24** | .20** | .21** | .21** | .12** | .16** | −.07** | .13** |

| Partner Personality | .09** | .13** | .06** | .08** | .04** | .05** | −.10** | .11** | |

| DS | .02 | .01 | .04* | .01 | −.04** | −.03* | −.06** | −.05** | |

| Conscientiousness | Actor Personality | .18** | .12** | .23** | .16** | .12** | .21** | −.11** | .13** |

| Partner Personality | .10** | .10** | .04** | .04** | .05** | .10** | −.11** | .12** | |

| DS | .03* | −.03 | .00 | .01 | −.01 | −.04** | .05** | −.08** | |

| Openness | Actor Personality | −.04** | −.09** | .09** | .05** | .14** | .16** | −.02 | .10** |

| Partner Personality | −.02 | −.03* | .02 | .01 | .08** | .06** | −.05** | .08** | |

| DS | −.02 | −.06** | .01 | .00 | −.02 | −.06** | .07** | −.09** | |

| R-Squared

|

|||||||||

| All Big Five traits combined | Actor Personality | .102 | .063 | .151 | .055 | .104 | .107 | .065 | .050 |

| Partner Personality | .017 | .032 | .011 | .010 | .022 | .011 | .025 | .021 | |

| DS | .000 | .005 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .002 | .004 | .008 | |

| Second-order terms | – | – | – | – | – | .003 | .005 | .010 | |

Note. Please see Table 1 for sample characteristics of samples included in Dyrenforth et al. (2010). HILDA = Household Income and Labor Dynamics in Australia; BHPS = British Household Panel Study; GSOEP = German Socio-Economic Panel Study; HRS = Health and Retirement Study; GWB = general well-being; RWB = relational well-being; DS = standardized absolute difference score.

p < .05

p < .01

Polynomial Regression and Response Surface Analysis

We followed procedures similar to previous studies on personality and well-being and only interpreted polynomial and response surface regression coefficients that were significant at a p < .01 level (e.g., Neyer & Asendorpf, 2001; Parker, Lüdtke, Trautwein, & Roberts, 2012; Weidmann, Schönbrodt, et al., 2017). Moreover, similar to Dyrenforth et al. (2010), we calculated the outcome variance (R2) that was explained by actor, partner, and similarity effects to guide our interpretation of the findings.

We first compared three nested models for each of the Big Five traits and the three outcome variables (1) a model including only control variables, (2) the APIM, where actor and partner personality for all Big Five personality traits were added to the model with control variables, (3) and the full the polynomial model, which included control variables, actor and partner personality, and second-order polynomial regression coefficients for all personality traits. For all three outcomes, the full polynomial model showed the best fit to the data (Table 5), indicated by a smaller Akaike information criterion (AIC) value.

Table 5.

Relative Fit of APIM’s and Polynomial Models Predicting General Well-Being, Strain and Support

| Personality trait | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alla | Extraversion | Neuroticism | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | Openness | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Outcome | Model | ΔAIC | ΔR2 | ΔAIC | ΔR2 | ΔAIC | ΔR2 | ΔAIC | ΔR2 | ΔAIC | ΔR2 | ΔAIC | ΔR2 |

| General Well-Being | APIM | −2154.99 | 11.84% | −1168.32 | 6.43% | −1512.76 | 7.24% | −779.82 | 3.03% | −1010.26 | 5.12% | −933.09 | 2.66% |

| Polynomial | −22.31 | 0.37% | −6.30 | 0.10% | −3.66 | 0.06% | −14.48 | 0.16% | −6.66 | 0.11% | −10.51 | 0.17% | |

| Strain | APIM | −1358.81 | 9.04% | −423.15 | 1.07% | −1126.14 | 7.13% | −496.80 | 2.07% | −574.35 | 2.67% | −490.63 | 0.28% |

| Polynomial | −25.12 | 0.50% | −11.81 | 0.17% | 4.41 | 0.00% | −19.46 | 0.29% | −22.86 | 0.26% | −21.74 | 0.33% | |

| Support | APIM | −1189.41 | 7.13% | −646.05 | 3.34% | −813.16 | 3.92% | −673.75 | 3.68% | −679.05 | 3.56% | −610.09 | 1.93% |

| Polynomial | −68.35 | 1.00% | −14.01 | 0.25% | −77.26 | 0.09% | −17.08 | 0.23% | −47.67 | 0.61% | −42.33 | 0.45% | |

Note. APIM = actor-partner interdependence model. The difference in Akaike information criterion (ΔAIC) was used as a relative fit indicator with negative values larger than -2 indicating an improvement in fit. The difference in R-squared (ΔR2) refers to the gain in variance explained in the outcome variable. The fit of the APIM (including control variables, Xactor and Ypartner) was compared with the model including only control variables. In the polynomial model, Xactor2, XactorYpartner, and Ypartner2 were added, which was compared with the APIM.

These models included all Big Five personality traits simultaneously.

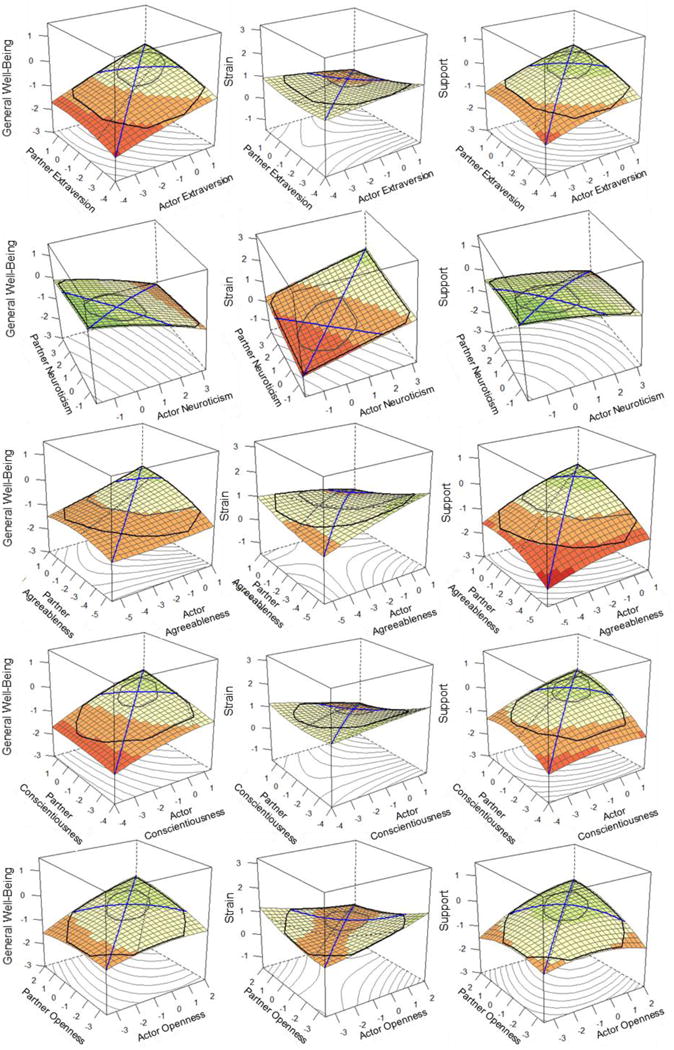

Compared to the model which included only control variables, the APIM explained 11.84% more variance in general well-being, 9.04% in strain, and 7.13% in support. Adding the second-order polynomial regression coefficients additionally explained 0.37% of the variance in general well-being, 0.50% in strain, and 1.00% in support (Table 5). Even though the second-order terms explained a relatively small amount of variance in the outcome variables, the increase in model fit justified further examination of possible personality similarity effects on general and relational well-being. As a next step, we conducted model-comparison tests separately for each Big Five trait (Table 5). For every outcome and personality trait, we tested if the response surface parameters satisfied the conditions for similarity (Table 6, 7, and 8) and interpreted the meaning of the effects by visualizing the results in three dimensional response surface plots. In Figure 3, the black polygons indicate the position of the inner 50% of the bivariate data-points (inner polygon), and the range of the data in the complete sample, excluding outliers (outer polygon). The mean of the sample can be found in the middle of the inner polygon. As can be seen in Figure 3, the bivariate mean of the sample was higher than the midpoint of the scale for extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness, and lower than the midpoint of the scale for neuroticism. The surface can only be interpreted in the regions within the outer polygon.

Table 6.

Standardized Polynomial Regression Coefficients and Response Surface Parameters of Actor- and Partner Personality Predicting General Well-Being

| Extraversion | Neuroticism | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | Openness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polynomial Regression Parameters | |||||

| b1 Actor | .24** [.22, .26] |

−.26** [−.28, −.24] |

.18** [.16, .20] |

.20** [.18, .22] |

.16** [.14, .18] |

| b2 Partner | .08** [.06, .09] |

−.10** [−.11, −.08] |

.03* [.01, .06] |

.11** [.08, .13] |

.06** [.04, .08] |

| b3 Actor2 | −.01 [−.02, .00] |

−.02** [−.04, −.01] |

.01 [−.01, .02] |

−.02** [−.04, −.01] |

−.02** [−.04, −.01] |

| b4 Actor* Partner | .02 [.00, .04] |

.00 [−.02, −.02] |

.02* [.00, .04] |

.03* [.00, .05] |

.04** [.02, .06] |

| b5 Partner2 | −.02** [−.04, −.01] |

.00 [−.02, −.01] |

−.02** [−.04, −.01] |

−0.01 [−.02, .01] |

−.02** [−.04, −.01] |

|

Response Surface Parameters | |||||

| a1 (b1 + b2) | .31** [.28, .34] |

−.35** [−.38, −.32] |

.21** [.17, .25] |

.31** [.27, .34] |

.22** [.19, .25] |

| a2 (b3 + b4 + b5) | −.02 [−.05, .01] |

−.02 [−.05, −.00] |

.01 [−.02, .03] |

.00 [−.03, .02] |

.00 [−.03, .02] |

| a3 (b1 – b2) | .16** [.14, .18] |

−.16** [−.19, −.14] |

.15** [.12, .18] |

.10** [.07, .12] |

.10** [.08, .13] |

| a4 (b3 – b4 + b5) | −.05** [−.08, −.02] |

−.02 [−.06, −.01] |

−.04** [−.07, −.01] |

−.05** [−.09, −.02] |

−.08** [−.12, −.04] |

| a5 (b3 – b5) | .01 [.00, .03] |

−.02* [−.03, −.00] |

.03** [.01, .05] |

−0.02 [−.03, .01] |

.00 [−.02, .01] |

| Similarity effect? | No, a3 ≠ 0 | No, a3 ≠ 0 and a4 = 0 | No, a3 ≠ 0 and a5 ≠ 0 | No, a3 ≠ 0 | No, a3 ≠ 0 |

Note. The 95% confidence intervals are represented within brackets. All polynomial models included control variables.

p < .05

p < .01

Table 7.

Standardized Polynomial Regression Coefficients and Response Surface Parameters of Actor- and Partner Personality Predicting Strain.

| Extraversion | Neuroticism | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | Openness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polynomial Regression Parameters | |||||

| b1 Actor | −.08** [−.11, −.06] |

.23** [.21, .25] |

−.11** [−.13, −.08] |

−.12** [−.15, −.10] |

−.02 [−.04, .00] |

| b2 Partner | −.05** [−.08, −.03] |

.14** [.12, .16] |

−.11** [−.13, −.08] |

−.10** [−.13, −.08] |

−.05** [−.07, −.03] |

| b3 Actor2 | −.01 [−.02, .01] |

.00 [−.02, .01] |

−.01 [−.02, .01] |

.00 [−.02, .01] |

.01 [.00, .03] |

| b4 Actor* Partner | −.03** [−.05, −.01] |

.00 [−.02, .02] |

−.05** [−.07, −.03] |

−.04** [−.07, −.02] |

−.06** [−.09, −.04] |

| b5 Partner2 | .02** [.01, .04] |

.01 [−.01, .02] |

.01 [.00, .03] |

.03** [.01, .04] |

.03** [.01, .04] |

|

Response Surface Parameters | |||||

| a1 (b1 + b2) | −.14** [−.17, −.11] |

.37** [.34, .41] |

−.21** [−.25. −.17] |

−.23** [−.26, −.19] |

−.07** [−.10, −.03] |

| a2 (b3 + b4 + b5) | −.01 [−.05, .02] |

.01 [−.02, .03] |

−.04** [−.07. −.01] |

−.02 [−.05, .01] |

−.02 [−.05, .01] |

| a3 (b1 – b2) | −.03* [−.05, −.01] |

.09** [.07, .12] |

.00 [−.03. .03] |

−.02 [−.05, .01] |

.03* [.00, .05] |

| a4 (b3 – b4 + b5) | .05* [.01, .08] |

.00 [−.04, .04] |

.05** [.02. .08] |

.07** [.03, .11] |

.10** [.06, .14] |

| a5 (b3 – b5) | −.03** [−.04, −.01] |

−.01 [−.03, .01] |

−.02* [−.04. −.01] |

−.03** [−.05, −.01] |

−.01 [−.03, .01] |

| Similarity effect? | No, a4 = 0 and a5 ≠ 0 | No, a4 = 0 | Yes | No, a5 ≠ 0 |

Yes |

Note. The 95% confidence intervals are represented within brackets. All polynomial models included control variables. Because the lowest levels of strain represent the highest levels of well-being, we have to test if a4 is positive, which, in case of a similarity effect, would look like a U-shape along the LOIC.

p < .05

p < .01

Table 8.

Standardized Polynomial Regression Coefficients and Response Surface Parameters of Actor- and Partner Personality Predicting Support

| Extraversion | Neuroticism | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | Openness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polynomial Regression Parameters | |||||

| b1 Actor | .14** [.12, .16] |

−.16** [−.17, −.14] |

.13** [.11, .16] |

.13** [.11, .15] |

.10** [.08, .12] |

| b2 Partner | .08** [.06, .10] |

−.10** [−.12, −.08] |

.09** [.07, .12] |

.10** [.08, .12] |

.08** [.06, .10] |

| b3 Actor2 | −.02** [−.04, −.01] |

−.02** [−.04, −.01] |

−.02** [−.03, .00] |

−.02** [−.04, −.01] |

−.04** [−.06, −.03] |

| b4 Actor* Partner | .02 [.00, .04] |

0.01 [−.01, .03] |

.02* [.00, .04] |

.03** [.01, .06] |

.06** [.04, .08] |

| b5 Partner2 | −.03** [−.04, −.01] |

−.02** [−.04, −.01] |

−.03** [−.05, −.02] |

−.05** [−.06, −.04] |

−.04** [−.06, −.03] |

|

Response Surface Parameters | |||||

| a1 (b1 + b2) | .22** [.19, .25] |

−.26** [−.29, −.23] |

.23** [.19, .26] |

.23** [.20, .27] |

.18** [.15, .21] |

| a2 (b3 + b4 + b5) | −.03* [−.06, .00] |

−.04* [−.06, −.01] |

−.03 [−.06, .00] |

−.04** [−.06, −.01] |

−.02 [−.05, .00] |

| a3 (b1 – b2) | .07** [.04, .09] |

−.05** [−.08, −.03] |

.04** [.01, .07] |

.03 [.00, .05] |

.02 [−.01, .04] |

| a4 (b3 – b4 + b5) | −.07** [−.10, −.04] |

−.05** [−.09, −.01] |

−.07** [−.10, −.04] |

−.11** [−.14, −.07] |

−.14** [−.18, −.10] |

| a5 (b3 – b5) | .01 [−.01, .02] |

.00 [−.02, .02] |

.01 [.00, .03] |

.03** [.01, .05] |

.00 [−.02, .02] |

| Similarity effect? | No, a3 ≠ 0 | No, a3 ≠ 0 | No, a3 ≠ 0 | No, a5 ≠ 0 | yes |

Note. The 95% confidence intervals are represented within brackets. All polynomial models included control variables.

p < .05

p < .01

Figure 3.

Response surfaces indicating the association between general well-being, strain, and support (vertical axes), and combinations of actor and partner personality (horizontal axes). The black dotted line represents the ridge of the surface. The black polygons indicate the position of the inner 50% of the bivariate data-points (inner polygon), and the range of the complete sample, excluding outliers (outer polygon). The surface can only be interpreted in the regions within the outer polygon.

To test if the response surface met the conditions for similarity, we focused on significance testing of the RSA parameters a1-a5 (Humberg et al., in press). When the parameters of the full polynomial model met the conditions for a similarity effect, we tested if they could be constrained to represent a similarity effect above main effects without worsening model fit (i.e., ΔAIC < 2). By imposing the following constraints on the parameters of the full polynomial model: b1 = b2, b3 = b5, and b4 = −2b5 (Schönbrodt, 2016b), similarity effects were constrained to be equal across the entire response surface (i.e., across all lines parallel to the LOIC/perpendicular to the LOC). If the constrained model would have an equal or better model fit compared to the full polynomial model, this would provide support that similarity effects would be similar across all levels of personality.

General well-being

Model-comparison tests indicated that the polynomial model predicting general well-being had the best fit for each of the Big Five traits separately (Table 5). The variance explained in general well-being by the second-order terms ranged from 0.06% for neuroticism to 0.17% for openness. None of the Big Five traits satisfied the conditions for similarity effects in a broad sense in predicting general well-being (Table 6). The specific shapes of the five response surfaces in predicting general well-being indicated more complex patterns, which we describe in more detail below.

Extraversion

The RSA of extraversion in predicting general well-being indicated a complex combination of positive main effects, with actor effects that were larger than partner effects and a ridge line with optimal combinations of actor and partner personality. The conditions of similarity were not met because a3 was significant. This suggested that the highest general well-being along the LOIC was not reached when couples showed an exact match in extraversion. The shape of the LOIC suggested that dissimilarity had a negative impact on actor’s general well-being if partner extraversion exceeded actor extraversion. In contrast, if actor extraversion exceeded partner extraversion, the level of actor reported general well-being was just as high, or slightly higher compared with similar couples. Thus, even if we only considered couples with extraversion scores along the LOIC, similarity was not always related to lower levels of general well-being compared to dissimilarity.

Neuroticism

The RSA indicated that actor and partner neuroticism were negatively related to general well-being, with actor effects larger than partner effects, and no ridge line containing optimal combinations of actor and partner personality. The response surface plot (Figure 3) resembled Figure 2, suggesting only negligible effects of second-order terms over and above linear main effects of actor and partner neuroticism.

Agreeableness

The RSA of agreeableness effects on general well-being (Figure 3) indicated positive actor effects, no partner effects, and a ridge line that was rotated away from the LOC. The rotation of the ridge line (a5 ≠ 0) suggested that if both partners scored relatively low on agreeableness, the highest level of actor-reported general well-being was reached when partner personality exceeded actor personality. Conversely, if both partners scored relatively high on agreeableness, the highest level of general well-being was reached when actor and partner personality were similar, or if actor personality exceeded partner personality. In addition, the significant a3 coefficient indicated that when comparing couples along the LOIC, the highest levels of general well-being were reached when actor personality slightly exceeded partner personality. The shape of the LOIC further suggested that dissimilarity only led to lower well-being if partner agreeableness exceeded actor agreeableness.

Conscientiousness

The RSA of conscientiousness predicting general well-being (Figure 3) suggested that both actor and partner conscientiousness were positively related to general well-being, and that actor effects were larger than partner effects. In addition, optimal well-being along the LOIC was not reached when couples showed an exact match, but when actor conscientiousness exceeded partner conscientiousness (a3 > 0). The shape of the LOIC further suggested that dissimilarity only led to lower well-being if partner conscientiousness exceeded actor conscientiousness.

Openness

The RSA of openness showed a similar pattern as conscientiousness in predicting general well-being. That is, the RSA indicated positive main effects of openness, with actor effects larger than partner effects. Along the LOIC, optimal levels of general well-being were reached if actor openness exceeded partner openness, as compared to lower levels of well-being when actors and partners had similar scores in openness (Figure 3).

Strain

Model-comparison tests indicated that the polynomial model predicting strain was the best-fitting model for extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness. For neuroticism, the APIM had the best fit, suggesting only actor and partner effects but no similarity effects (Table 5). The variance explained in strain by the second-order terms ranged from 0.17% for extraversion to 0.30% for openness.

Optimal scores in the models predicting strain would be reflected by a ‘valley’ line instead of the ridge line (i.e., a4 > 0). This would look like a U-shape along the LOIC. Agreeableness and openness met the four conditions for a similarity effect in predicting relational strain (Table 7). For agreeableness, the response surface (Figure 3) suggested that similarity in agreeableness was associated with less strain, with linear and quadratic main effects (i.e., a curvilinear effect along the LOC). The response surface for openness suggested that similarity in openness was related to less strain, with no actor effects and small partner effects. However, for both models, model fit worsened when parameters of the full polynomial model were constrained to reflect a similarity effect (for agreeableness, ∆AIC = 12.51; for openness, ∆AIC = 4.14), indicating that similarity effects were not be stable across all levels of personality (i.e., across all lines parallel to the LOIC). The findings for the other three traits (extraversion, neuroticism, and conscientiousness) are interpreted below.

Extraversion

The RSA of extraversion predicting relational strain indicated negative actor and partner effects, with actor effects larger than partner effects, and a valley line that was rotated away from the LOC (Figure 3). The a4 coefficient did not meet our threshold of statistical significance (i.e., p = .010), indicating that there was no clear ridge line containing the highest levels of well-being. The response surface indicated that a match was only beneficial at high levels of both actor and partner extraversion. At low and moderate levels of both actor and partner extraversion, the level of relational strain did not seem to depend on the combination of actor and partner personality.

Neuroticism

Despite the APIM having the best fit for neuroticism predicting strain, we also calculated the response surface parameters and created a response surface plot (Figure 3). The response surface plot was similar to Figure 2, indicating only positive main effects of actor/partner neuroticism, with actor effects larger than partner effects and no similarity in neuroticism predicting strain.

Conscientiousness

The RSA of openness predicting relational strain indicated negative actor and partner effects that were equal in size, and a valley line that was rotated away from the LOC (Figure 3). If both partners had low levels of conscientiousness, the lowest levels of strain were reached when partner personality exceeded actor personality to a certain extent. This effect was also found when only considering couples along the LOIC. However, at higher levels of actor and partner conscientiousness, the valley line approached the LOC, which suggested that a match in conscientiousness was associated with the lowest levels of strain.

Support

Model-comparison tests indicated that the polynomial model predicting relational support was the best-fitting model for all Big Five traits (Table 5). The variance explained by the second-order terms in predicting support ranged from 0.09% for neuroticism to 0.61% for conscientiousness. Openness was the only personality trait that satisfied the conditions for a similarity effect in predicting support (Table 8). The response surfaces of openness (Figure 3) resembled Figure 1, thus indicating a combination of positive actor and partner effects that were about equal in size, and a similarity effect. In addition, the full polynomial model and constrained similarity model for openness predicting support fit the data equally well (∆AIC = −0.77), providing support for a similarity effect that was stable across all levels of personality. The shapes of the response surfaces that did not meet the conditions for a similarity effect in predicting support (extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness and conscientiousness) are described below.

Extraversion

The RSA of extraversion predicting support suggested positive actor and partner effects, with actor effects larger than partner effects, and a ridge line with optimal combinations of actor and partner personality. The response surface (Figure 3) indicated that for couples along the LOIC, dissimilarity only led to lower levels of support when partner extraversion exceeded actor extraversion.

Neuroticism

The RSA of neuroticism predicting support indicated negative actor and partner effects, with actor effects larger than partner effects. Even though a4 was negative, the response surface (Figure 3) showed only small curvilinear effects and did not show a clear ridge line that might reflect the highest levels of support. Therefore, the response surface seemed to suggest only negligible effects of second-order terms over and above main effects of actor and partner neuroticism in predicting relational support.

Agreeableness

The RSA of agreeableness predicting support suggested positive actor and partner effects, with actor effects larger than partner effects, and a ridge line with optimal combinations of actor and partner personality. For couples along the LOIC, optimal well-being was reached when actor personality slightly exceeded partner personality.

Conscientiousness

The RSA of conscientiousness predicting support indicated positive actor and partner effects that were equal in size, with a ridge line that was rotated and shifted away from the LOC. The response surface (Figure 3) indicated that if actors and partners scored low on conscientiousness, optimal levels of relational support were reached when partner personality exceeded actor personality to a certain extent. At higher levels of conscientiousness, ridge line approached the LOC, indicating that personality similarity in conscientiousness might be beneficial for relational support.

Summary

Of the 15 models examined (i.e., five personality traits and three outcomes), only three models indicated a similarity effect. Specifically, similarity in openness was related to lower levels of relational strain and higher levels of relational support. In addition, similarity in agreeableness was related to lower levels of strain. However, only for openness predicting support, model fit did not worsen when parameters were constrained to reflect a similarity effect, suggesting that this was the only similarity effect that was stable across all levels of personality. For neuroticism, the second-order terms played a negligible role in predicting relational and general well-being over and above actor and partner effects, explaining less than 0.10% of the variance in general and relational well-being.

For all other traits, including the second-order personality terms improved model fit and systematically explained a small amount of variance (ranging between 0.10% and 0.61%) in each of the three outcomes. One general pattern found was that the LOIC was usually shaped as a U or inverted U. This suggested that there was an optimal combination of actor and partner personality. However, most models indicated that the highest levels of well-being were not reached when actor and partner personality showed an exact match, but rather that the effect of similarity and dissimilarity depended on the level of actor and partner personality. Yet, before drawing final conclusions about similarity effects and alternative patterns, we first examined if the effects were moderated by gender and measurement wave.

Moderating Role of Gender and Measurement Wave

Table 9 shows the relative model fit of all moderator models. For each personality trait, we first compared model fit between the polynomial model (including control variables, Xactor, Ypartner Xactor2, XactorYpartner, and Ypartner2) and a model including interactions of gender (or measurement wave) with main effects Xactor and Ypartner, and second-order terms Xactor2, XactorYpartner, and Ypartner.

Table 9.

Relative Fit of Moderation Models Predicting General Well-Being, Strain and Support

| Outcome | Model | Extraversion

|

Neuroticism

|

Agreeableness

|

Conscientiousness

|

Openness

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔAIC | ΔR2 | ΔAIC | ΔR2 | ΔAIC | ΔR2 | ΔAIC | ΔR2 | ΔAIC | ΔR2 | ||

| General Well-Being | Gender | 4.51 | 0.05% | −4.14 | 0.07% | 9.27 | 0.01% | −7.77 | 0.08% | 1.01 | 0.05% |

| Wave | −6.90 | 0.07% | −23.48 | 0.10% | −11.15 | 0.07% | −13.50 | 0.10% | −0.58 | 0.05% | |

| Strain | Gender | −1.36 | 0.08% | 1.55 | 0.04% | 4.21 | 0.03% | 3.29 | 0.04% | −1.26 | 0.07% |

| Wave | 2.36 | 0.04% | 4.64 | 0.03% | −6.45 | 0.08% | 4.24 | 0.05% | −0.35 | 0.01% | |

| Support | Gender | −15.91 | 0.15% | −11.21 | 0.08% | −8.64 | 0.09% | −14.27 | 0.13% | −19.79 | 0.24% |

| Wavea | −11.98 | 0.10% | −2.31 | 0.05% | −2.49 | 0.09% | −1.97 | 0.05% | 0.83 | 0.05% | |

| Support - male report | Wavea | −4.47 | 0.22% | − | − | 0.57 | 0.14% | – | – | 3.16 | 0.14% |

| Support -female report | Wavea | 3.82 | 0.10% | − | − | 1.40 | 0.13% | – | – | 6.41 | 0.05% |

Note. The Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used as a measure of relative model fit. Negative values larger than -2 indicate an improvement in fit. The difference in R-squared (ΔR2) refers to the gain in variance explained in the outcome variable. The fit of the polynomial model (including control variables, Xactor, Ypartner Xactor2, XactorYpartner, and Ypartner2) was compared to a model including interactions of gender or measurement wave with main effects and second-order terms Xactor2, XactorYpartner, and Ypartner2.

For models that were moderated by gender (see Table S2), we examined the moderation of measurement wave for men and women separately. However, to be able to compare the proportion of variance explained between these models and the other models, ΔR2 was also calculated for the complete sample.

Gender

Seven out of 15 polynomial models improved in model fit after adding interactions between the five polynomial regression coefficients and gender (Table 9). This included all five models for support, two models for general well-being, and no models for strain. Table S1 shows the gender moderation effects for the models that improved in fit. As can be seen in Table S1, most polynomial regression coefficients did not interact with gender (i.e., p ≥ .01 for 32 out of 35 coefficients), indicating small (or no) differences between men and women. In line with this, only a small amount of variance in the outcome measures was explained by the moderation effects of gender, ranging from 0.00% to 0.24% (Table 9).

The polynomial regression coefficients of extraversion, agreeableness, and openness predicting support did show significant interactions with gender (Table S2). For agreeableness, similarity effects were present in predicting women’s but not men’s experiences of relational support. Model fit improved (∆AIC = −3.90) when parameters were constrained to reflect a similarity effect, suggesting that this effect was stable across all levels of personality (i.e., all lines parallel to the LOIC). For extraversion, women experienced optimal relational support when actor extraversion exceeded their partners’ extraversion. The model for extraversion predicting men’s support indicated no ridge line containing optimal levels of well-being.

For openness predicting female’s support, the response surface parameters met the conditions for a similarity effect. However, model fit worsened when parameters were constrained to reflect a similarity effect (∆AIC = 5.60), indicating that similarity effects were not stable across all levels of personality (i.e., all lines parallel to the LOIC). Furthermore, the similarity effect did not hold for men, because a3 was smaller than zero. This indicated that, along the LOIC, support experienced by men was highest when male openness exceeded female openness to a certain extent.

Measurement Wave

Because of the significant gender interactions just described, the moderation of measurement wave was also examined separately for men and women for the models of extraversion, agreeableness, and openness in predicting support (see bottom rows of Table 9). This resulted in 18 models, of which 8 improved in fit after adding interactions between the five polynomial regression coefficients and measurement wave (Table 9). Table S3 shows the moderation effects of measurement wave for the eight models that improved in fit. Similar to the patterns found for gender, most polynomial regression coefficients (i.e., p ≥ 0.01 for 37 out of 40 coefficients) did not interact with measurement wave, indicating that most effects, including all similarity effects, were consistent across the three waves of the study. In line with this, only a small amount of variance in the outcome measures was explained by the moderation effects of measurement wave, ranging from 0.01% to 0.10% (Table 9).

Three models showed significant interactions between measurement wave and the polynomial regression parameters. These three models initially did not meet the conditions for similarity effects, and each of these models only contained one coefficient that interacted with measurement wave. The simple slopes analyses (Table S4) revealed that all three polynomial regression parameters decreased in size and sometimes became nonsignificant at the second or third measurement wave.2,3

In sum, the moderator analyses indicated that actor and partner effects were mostly robust across gender and time.4 One similarity effect initially found for openness in predicting support was moderated by gender, and did not satisfy the conditions for similarity when men and women were examined separately. The only similarity effect that found after the moderator analyses is the effect of agreeableness in predicting women’s support. We found that only three polynomial regression coefficients became weaker across time, indicating that most effects were robust across the eight years of the study (see summary of results in Table 10).

Table 10.

Summary of Main Findings Polynomial Regression, Response Surface, and Moderation Analyses

| Predictor | Outcome | Similarity Effect | b1 Actor | b2 Partner | Moderation Wave |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion | General Well-Being | + | + | ||

| Strain | − | − | |||

| Support - men | + | + | |||

| Support -women | + | + | |||

| Neuroticism | General Well-Being | − | − | b1 Actor | |

| Strain | + | + | |||

| Support | − | − | |||

| Agreeableness | General Well-Being | + | |||

| Strain | − | − | b4 Actor*Partner | ||

| Support - men | + | + | |||

| Support -women | + | + | + | ||

| Conscientiousness | General Well-Being | + | + | b5 Partner2 | |

| Strain | − | − | |||

| Support | + | + | |||

| Openness | General Well-Being | + | + | ||

| Strain | − | ||||

| Support - men | + | + | |||

| Support -women | + | + |

Discussion

The current study aimed to conceptually replicate and extend previous research on personality similarity and individual and relational well-being by using a large longitudinal sample of older couples and response surface analyses. Our results were partly consistent with previous findings. That is, similar to previous studies using difference scores and profile correlations, response surface analyses indicated that second-order terms (i.e., the interaction term and quadratic terms of actor and partner personality) explained a relatively small amount of variance in well-being compared to the variance explained by actor and partner effects (Table 4). However, an important novel finding is that second-order terms were systematically related to well-being for all traits except neuroticism, suggesting a complex pattern in which the impact of similarity and dissimilarity depended on the level of actor and partner of personality. Moreover, one similarity effect was robust across the eight years of the study, indicating that similarity in agreeableness might have small but meaningful implications for women’s relational support. Below, we discuss the implications of our study for theory and research on personality similarity in romantic relationships.

Linear Effects of Actor and Partner Personality