Abstract

Background

Michigan expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (Healthy Michigan Plan [HMP]) to improve the health of low-income residents and the state’s economy.

Objective

To understand HMP’s impact on enrollees’ health, ability to work, and ability to seek employment

Design

Mixed methods study, including 67 qualitative interviews and 4090 computer-assisted telephone surveys (response rate 53.7%)

Participants

Non-elderly adult HMP enrollees

Main Measures

Changes in health status, ability to work, and ability to seek employment

Key Results

Half (47.8%) of respondents reported better physical health, 38.2% better mental health, and 39.5% better dental health since HMP enrollment. Among employed respondents, 69.4% reported HMP helped them do a better job at work. Among out-of-work respondents, 54.5% agreed HMP made them better able to look for a job. Among respondents who changed jobs, 36.9% agreed HMP helped them get a better job. In adjusted analyses, improved health was associated with the ability to do a better job at work (aOR 4.08, 95% CI 3.11–5.35, p < 0.001), seek a job (aOR 2.82, 95% CI 1.93–4.10, p < 0.001), and get a better job (aOR 3.20, 95% CI 1.69–6.09, p < 0.001), but not with employment status (aOR 1.08, 95% CI 0.89–1.30, p = 0.44). In interviews, several HMP enrollees attributed their ability to get or maintain employment to improved physical, mental, and dental health because of services covered by HMP. Remaining barriers to work cited by enrollees included older age, disability, illness, and caregiving responsibilities.

Conclusions

Many low-income HMP enrollees reported improved health, ability to work, and job seeking after obtaining health insurance through Medicaid expansion.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-018-4736-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

INTRODUCTION

Recent efforts to reform US health care have proposed sweeping changes to the Medicaid program for low-income individuals.1–3 Seven of the 33 states that have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) have implemented their programs through Section 1115 waivers that allow state-specific program modifications.4 Such modifications have included changes in eligibility time limits, cost sharing, and encouragement of consumer behaviors.5 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) under the Trump administration has recently signaled greater willingness to consider a broad array of Medicaid waivers, including programs that encourage or require work for non-elderly adult enrollees.6, 7

While early studies of ACA Medicaid expansions have focused on assessing changes in access and utilization,8 less is known about the impacts of Medicaid expansion through either the standard program or 1115 waiver programs on employment outcomes. State-specific studies of labor demand in Colorado, Kentucky, and Michigan have estimated significant job growth associated with increased funding provided by Medicaid expansions.9–11 National studies of labor supply have shown no impact of Medicaid expansion on overall employment, working hours, or retirement decisions.12–16 But scant evidence is currently available regarding how Medicaid expansion might affect individual enrollees’ ability to look for and maintain work. One study found that people with disabilities were more likely to be employed after Medicaid expansion.17 Another study of Medicaid expansion enrollees in Ohio showed that the program was associated with improvements in ease of working or looking for work, which the authors attributed to health improvements.18 These studies suggest that changes in health associated with insurance coverage could help achieve improvements in employment outcomes.19

However, more evidence is needed about the impact of Medicaid expansion on individual enrollees’ ability to work.8 Our study focuses on Michigan’s Medicaid expansion, known as the “Healthy Michigan Plan” (HMP). This program was launched in April 2014 to improve the health of low-income residents and the state’s economy.20 Michigan expanded its Medicaid program through an 1115 waiver to cover approximately 680,000 low-income adults.21 The objective of our study was to assess the impact of obtaining Medicaid expansion coverage on enrollees’ health and how that affected their self-reported ability to work and seek employment.

METHODS

Study Design

Under contract with the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS), we conducted a sequential mixed methods study of enrollees as part of a formal evaluation of the Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration. Data sources included qualitative interviews and a telephone survey with enrollees across the State of Michigan. The University of Michigan and MDHHS Institutional Review Boards considered the study exempt from review as a federally mandated evaluation of a public program.

Qualitative Interview Participants and Recruitment

To inform survey development and to aid in interpretation of survey findings, we conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with 67 HMP enrollees from five geographic regions across Michigan (Detroit, Western Michigan, Central Lower Michigan, Northeastern Michigan, and the Upper Peninsula) in April–August 2015. Regions included a diverse range of medically underserved populations, racial/ethnic groups, and urban and rural environments.

Interview participants with ≥ 6 months of HMP enrollment who had used at least one HMP-covered health care service were recruited through community outreach efforts guided by a statewide community advisory board (see Appendix Methods for recruitment methods). Purposive sampling methods were used to select interviewees with a diversity of age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, health conditions, and urban/rural residence. See Appendix Table 1 for interviewee characteristics.

Qualitative Interviews and Analysis

The study team developed an interview guide and pilot tested it with two HMP enrollees. Domains were assessed by open-ended questions with follow-up probes, and included perceptions of the impact of HMP on health, employment and other aspects of enrollees’ lives. Interviews were conducted by phone in English or Spanish and lasted approximately one hour. A thank you letter and $40 gift card were mailed to each participant after the interview. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and coded iteratively using in-depth coding and thematic analysis by two qualitative analysts with the aid of Dedoose software (http://www.dedoose.com).22, 23

Survey Sampling

During January through October 2016, a stratified sample of HMP enrollees was drawn each month with proportionate allocations to overall HMP enrollment by income (0–35%, 36–99%, and 100–133% of the federal poverty level [FPL]) and geographic region (Northern Michigan, Central Michigan, Southern Michigan, and Detroit). Inclusion criteria at the time of sample selection were age 19–64; initial HMP enrollment ≥ 12 months prior to sampling with ≥ 9 months in a HMP managed care plan; preferred language of English, Spanish, or Arabic; and a complete Michigan address and phone number in the MDHHS Medicaid claims data warehouse.

Survey Administration

HMP enrollees selected for the survey sample were mailed an introductory packet from the University of Michigan containing a letter and brochure describing the project, and a postage-paid postcard that could be optionally mailed to indicate their preferred time/day for the survey. Study team members called sampled HMP enrollees on weekdays 9 a.m.–9 p.m. or at enrollees’ requested time. Surveys were conducted with a computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) system in English, Arabic, and Spanish and lasted approximately one hour. A thank you letter and $25 gift card were mailed to each participant after the survey.

Survey Responses

Overall, 9350 HMP enrollees were sampled during the data collection period. Of those sampled, 123 enrollees were never contacted by phone due to exclusions (non-mailable addresses; no available language-specific interviewers; never contacted because data collection goals were already achieved). Pre-notification letters were sent to the remaining 9227 enrollees. Among these HMP enrollees, 4108 enrollees (weighted N = 379,627) ultimately completed the survey (weighted response rate = 53.7% using the American Association for Public Opinion Research’s response rate formula 3).24 Eighteen surveys with > 20% missing data were excluded from further analysis, leaving 4090 respondents with fully completed surveys for analysis. Appendix Fig. 1 depicts a flowchart of survey responses.

Enrollees who were younger, male, or living in Detroit were slightly less likely to respond to the survey (Appendix Table 2). Income was not associated with nonresponse. To account for potential nonresponse bias, we applied nonresponse adjustment to sampling weights in which we controlled for age, gender, race/ethnicity, enrollment month, sampling strata, sampling month, and the interaction between sampling strata and sampling month.25

Survey Measures

Our main outcomes were perceptions of changes in health status, ability to work, ability to seek a job, and current employment status. As this was a cross-sectional survey following implementation of the HMP program, enrollees’ reports of perceived changes were assessed by individual survey items. Changes in health status were assessed by the following survey items: “Overall, since you enrolled in the Healthy Michigan Plan, would you say your physical health has gotten better, stayed the same, or gotten worse?”; “Overall, since you enrolled in the Healthy Michigan Plan, would you say your mental and emotional health has gotten better, stayed the same, or gotten worse?”; “Thinking about your dental health, since you enrolled in the Healthy Michigan Plan, has the health of your teeth and gums gotten better, stayed the same, or gotten worse?”. For respondents who were working, changes in ability to work were assessed by the following survey items: “In the past 12 months, about how many days did you miss because of illness or injury (do not include maternity leave)?”; “Compared to the 12 months before this time, was this more, less, or about the same?”; “Has getting health insurance through the Healthy Michigan Plan helped you do a better job at work?”. Changes in job seeking were assessed by the following survey items with response options of strongly agree/agree/neutral/disagree/strongly disagree: “Having health insurance through the Healthy Michigan Plan has made me better able to look for a job” (for those not working) and “Having health insurance through the Healthy Michigan Plan helped me get a better job” (for those with a recent job change but currently working).

Employment status was assessed at a single point in time by the following survey item: “What is your current job status. Are you currently [employed or self-employed; out of work for 1 year or more; out of work for less than 1 year; a homemaker; a student; retired; unable to work]?”

The survey also included standard measures of demographics, health status, insurance status, health care access, and utilization from established national surveys.26–30 When established measures were not available, new items were developed based on findings from the qualitative interviews (e.g., related to HMP’s specific features or impact). New items underwent cognitive pre-testing before being included in the survey instrument.

Survey Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to report responses to individual survey items. We then used multivariable logistic regression to assess the adjusted association between reported changes in health and work outcomes, adjusting for age, gender, race, income, health status, presence of chronic health condition, and functional limitation. We checked for collinearity of variables, including between health status, chronic conditions, and functional limitation, and found no collinearity in the model. To represent the eligible HMP enrollee population, all analyses were weighted to account for sampling and nonresponse. Analyses were performed with Stata version 14.2, and two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Mixed Methods Analysis

The study team interpreted the findings from the qualitative interviews and the survey in light of each other, considering synergies across findings. We integrated findings from the interviews and the survey using a joint display,31 allowing us to compare convergence or divergence of findings across data sources.32

RESULTS

Survey Respondents’ Demographic Characteristics and Employment Status

Most survey respondents (74.0%) were age 50 or younger, approximately half (51.6%) were women, and approximately a quarter (26.1%) were Black/African-American (Table 1). Most respondents (80.2%) had incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level. Nearly half (48.9%) reported they were currently employed/self-employed, approximately a quarter (27.6%) were out of work, 11.3% were unable to work, and smaller percentages were retired, students, or homemakers.

Table 1.

Healthy Michigan Plan Enrollee Survey Respondent Characteristics

| Characteristics |

n = 4090 (weighted N = 379,627) (weighted %) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 19–34 | 40.0% |

| 35–50 | 34.0% |

| 51–64 | 26.0% |

| Gender | |

| Male | 48.4% |

| Female | 51.6% |

| Race | |

| White/Caucasian | 61.2% |

| Black/African-American | 26.1% |

| Other | 8.8% |

| More than one race | 4.0% |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5.2% |

| Arab/Chaldean/Middle Eastern | 6.2% |

| Income (% of federal poverty level) | |

| 0–35% | 51.8% |

| 36–99% | 28.4% |

| 100–133% | 19.8% |

| Marital status | |

| Married/partnered | 24.7% |

| Single/divorced/widowed/separated | 75.4% |

| Health status | |

| Excellent | 9.5% |

| Very good | 26.8% |

| Good | 33.8% |

| Fair | 22.2% |

| Poor | 7.5% |

| Chronic health condition | |

| Any condition present | 69.2% |

| At least 1 physical health condition present | 60.8% |

| At least 1 mental health condition present | 32.1% |

| Functional limitation (≥ 14 of past 30 days) | |

| Physical | 22.8% |

| Mental | 19.9% |

| Employment status | |

| Employed/self-employed | 48.9% |

| Out of work | 27.6% |

| < 1 year | 7.9% |

| ≥ 1 year | 19.7% |

| Unable to work | 11.3% |

| Retired | 2.5% |

| Student | 5.2% |

| Homemaker | 4.5% |

| Geographic region | |

| Northern Michigan | 9.0% |

| Central Michigan | 28.6% |

| Southern Michigan | 18.6% |

| Detroit Metro | 43.8% |

Perceived Impact of HMP on Health

Among survey respondents, 70.1% reported they had excellent, very good, or good health (Table 1). A similar proportion (69.2%) reported they had at least one chronic health condition. Nearly one quarter of respondents (22.8%) reported they had a physical functional limitation, and one fifth (19.9%) had a mental functional limitation that limited their daily activities during at least 14 of the past 30 days. Respondents were more likely to be employed if they had good or better health status or if they had no chronic conditions (Appendix Table 3). However, a substantial number of enrollees with fair or poor health status (32.3%) or with chronic conditions (44.1%) were working.

Since enrollment in HMP, 47.8% of respondents reported their physical health had gotten better, 46.1% reported it had stayed the same, and 5.5% reported it had gotten worse. 38.2% reported their mental health had gotten better, 56.8% reported it had stayed the same, and 4.6% reported it had gotten worse. 39.5% reported their dental health had gotten better, 45.5% reported it had stayed the same, and 10.4% reported it had gotten worse. These survey reports of changes in physical, mental, and dental health correlated with themes identified in qualitative interviews (see joint display of interview and survey findings in Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in Health and Ability to Work After Healthy Michigan Plan Enrollment: a Joint Display of Survey and Interview Findings

| Survey findings | Illustrative quotes from enrollee interviews |

|---|---|

| 47.8% of enrollees reported better physical health since HMP. |

“With moving around, you know, climbing a ladder [for work] and doing all that stuff, it’s helped a lot with my back and all that.” (Male, age 19–34, Western Michigan) “If you do not know you got it, and you do not know what’s causing your ailment, then you are not able to get the medications that you need or the care that you need, then that prevents you from being employable…I start school on the 22nd for a semi-truck driver. So I plan on driving trucks, and I need to know what’s going on with me if I am being careful myself on the road as well as others.” (Male, age 35–50, Detroit) |

| 38.2% of enrollees reported better mental health since HMP. |

“I have personally gotten better since being able to seek help for my mental issues, and that falls out over the rest of my life. I'm happier. I'm more able to work. I can function.” (Female, age 19–34, Northern Michigan) “I have actually changed my life around from what I used to be. Instead of sitting in the house all day, I can actually get out. I got a job now. I am actually getting my life together and trying to work on getting my daughter back…I can't do this without the suboxone program and I can't be on that without [Healthy Michigan Plan].” (Male, age 19–34, Northern Michigan) |

| 39.5% of enrollees reported better dental health since HMP. | “My teeth were pretty bad…and they fixed it up fine, and now…I feel better when I am looking for a job…I feel better because my appearance has changed a lot. That has helped me a lot, physically and mentally.” (Male, age 51–64, Detroit) |

| 29.7% of enrollees reported fair or poor health. |

“Right now, I haven't been able to work so I'm kind of slowed down by the illness. I don't have cancer any more but I'm going through post treatments and I have to start going through physical therapy. Once I'm done with that, I’ll probably be able to return to work. It’s actually good that I have [Healthy Michigan Plan] because, like I said, my job doesn't cover anything like this.” (Female, age 19–34, Detroit) “I was actually thinking about going to the Social Security office and applying for disability because…my eyes are bad because of my diabetes, but that’s the only bad thing I have that prevents me from getting a job.” (Female, age 35–50, Detroit) “…if you look at my age…Nobody trying to hire you…Most of the time when you're past 55…That’s just the way it is because, you know, they're saying you're old, you move slow, you can't pick up no kind of weight or nothing…’” (Female, age 51–64, Western Michigan) “I don't work. I stay home and take care of my handicapped husband and son.” (Female, age 51–64, Central Michigan) |

In interviews, several HMP enrollees attributed their ability to get or maintain their employment to improved physical, mental, or dental health because of services covered by HMP. However, some barriers to employment remained, including persistent poor health/illness, disability, older age, and caregiving responsibilities.

Perceived Changes in Ability to Work Among Employed Enrollees

Employed respondents missed a mean of 7.2 work days in the past year due to illness or injury. Most (68.4%) thought this was about the same number of missed work days as before HMP (Table 3). Regarding productivity at work, over two thirds (69.4%) of employed respondents reported that getting HMP insurance helped them to do a better job at work; 25.9% reported no change.

Table 3.

Changes in Ability to Work Among Employed Enrollees

| Ability to work among employed respondents | Mean (95% CI) or weighted % |

|---|---|

| Number of work days missed in past 12 months due to illness or injury | 7.2 days (5.6–8.7) |

| Compared to before HMP, missed work days are the following: | |

| Less | 17.2% |

| About the same | 68.4% |

| More | 12.3% |

| Do not know | 2.1% |

| “Has getting health insurance through the Healthy Michigan Plan helped you do a better job at work?” | |

| Yes | 69.4% |

| No | 25.9% |

| Do not know | 4.7% |

Perceived Changes in Job Seeking Among Enrollees Who Were Out of Work or Had a Recent Job Change

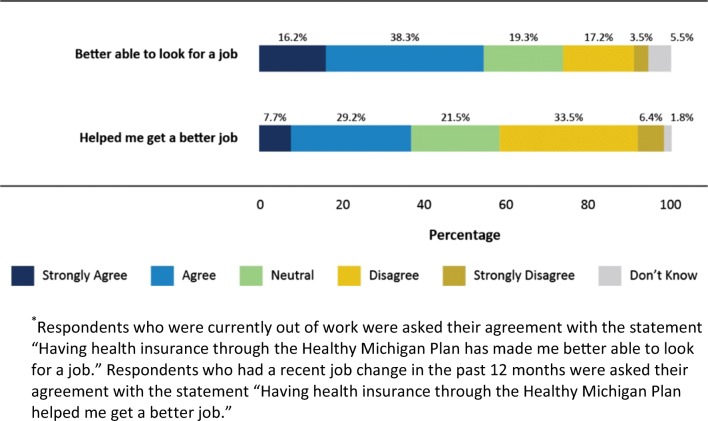

Respondents who were currently out of work were asked about their perceived ability to look for a job (Fig. 1). More than half (54.5%) strongly agreed or agreed that having HMP insurance made them better able to look for a job; 19.3% were neutral; and 20.7% disagreed. Respondents who had a job change in the past 12 months were asked about their success in recent job seeking. Over a third (36.9%) strongly agreed or agreed that having HMP insurance helped them get a better job, 21.5% were neutral, and 39.9% disagreed.

Figure 1.

Changes in job seeking ability among healthy Michigan plan enrollees who were out of work or had a recent job change. Respondents who were currently out of work were asked their agreement with the statement “Having health insurance through the Healthy Michigan Plan has made me better able to look for a job.” Respondents who had a recent job change in the past 12 months were asked their agreement with the statement “Having health insurance through the Healthy Michigan Plan helped me get a better job.”

Relationship Between Changes in Health and Work

While we were not able to assess longitudinal changes in employment status in this cross-sectional survey, we did examine the association between survey respondents’ reported changes in health and work outcomes. In multivariable analyses, enrollees with improved physical or mental health since enrollment were more likely (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 4.08, 95% CI 3.11–5.35, p < 0.001) to report that HMP helped them do a better job at work (Table 4). In addition, the presence of a chronic health condition was associated with a greater association between improved health and ability to do a better job at work (aOR 1.57, 95% CI 1.18–2.09, p = 0.002). However, we found no statistically significant association between improved physical or mental health since enrollment and current employment status (aOR 1.08, 95% CI 0.89–1.30, p = 0.44). Respondents older than age 50 had lower odds of employment (aOR 0.56, 95% CI 0.45–0.70, p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Association of Health Changes with Employment and Ability to Work among Employed Enrollees, and Job Seeking Ability among Enrollees Who Were Out of Work or had a Recent Job Change

| Characteristics | Outcomes* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employed/self-employed† (weighted N = 106,619) |

Better job at work‡ (weighted N = 75,282) |

Better able to look for job§ (weighted N = 35,711) |

Helped get a better jobǁ (weighted N = 9275) |

|||||

| aOR (95% CI) | p value | aOR (95% CI) | p value | aOR (95% CI) | p value | aOR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Physical or mental health better since HMP enrollment | 1.08 (0.89, 1.30) | 0.44 | 4.08 (3.11, 5.35) | < 0.001 | 2.82 (1.93, 4.10) | < 0.001 | 3.20 (1.69, 6.09) | < 0.001 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–34 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 35–50 | 0.98 (0.78, 1.24) | 0.89 | 0.96 (0.70, 1.31) | 0.78 | 1.36 (0.87, 2.11) | 0.17 | 1.01 (0.55, 1.87) | 0.97 |

| 51–64 | 0.56 (0.45, 0.70) | < 0.001 | 1.10 (0.80, 1.51) | 0.57 | 1.76 (1.14, 2.72) | 0.01 | 1.30 (0.65, 2.59) | 0.46 |

| Female gender | 1.00 (0.83, 1.21) | 0.98 | 1.42 (1.08, 1.85) | 0.01 | 0.73 (0.50, 1.07) | 0.10 | 0.72 (0.41, 1.25) | 0.24 |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Black | 0.96 (0.77, 1.21) | 0.74 | 1.55 (1.10, 2.19) | 0.01 | 0.80 (0.53, 1.22) | 0.30 | 1.31 (0.68, 2.55) | 0.42 |

| Other | 0.87 (0.61, 1.23) | 0.44 | 1.24 (0.69, 2.21) | 0.47 | 1.52 (0.73, 3.19) | 0.27 | 1.69 (0.65, 4.41) | 0.28 |

| More than one race | 1.10 (0.67, 1.82) | 0.71 | 1.70 (0.79, 3.67) | 0.18 | 0.51 (0.22, 1.23) | 0.13 | 0.46 (0.13, 1.67) | 0.24 |

| Income, % of federal poverty level (FPL) | ||||||||

| 0–35 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 36–99 | 3.72 (3.02, 4.58) | < 0.001 | 0.79 (0.54, 1.15) | 0.22 | 0.83 (0.53, 1.29) | 0.40 | 0.90 (0.47, 1.73) | 0.76 |

| 100–133 | 4.40 (3.51, 5.52) | < 0.001 | 0.62 (0.42, 0.90) | 0.01 | 0.74 (0.41, 1.36) | 0.33 | 0.60 (0.31, 1.17) | 0.13 |

| Fair or poor health | 0.67 (0.53, 0.83) | < 0.001 | 1.09 (0.76, 1.57) | 0.64 | 1.17 (0.79, 1.74) | 0.42 | 1.17 (0.56, 2.45) | 0.67 |

| Chronic health condition | 0.84 (0.67, 1.06) | 0.14 | 1.57 (1.18, 2.09) | 0.002 | 0.87 (0.54, 1.40) | 0.57 | 1.31 (0.72, 2.36) | 0.37 |

| Functional limitation, physical or mental | 0.26 (0.19, 0.34) | < 0.001 | 1.20 (0.69, 2.09) | 0.53 | 0.85 (0.56, 1.30) | 0.46 | 1.51 (0.47, 4.89) | 0.49 |

Associations with p < 0.05 are in italic

aOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence interval; HMP Healthy Michigan Plan

*Each column represents a different multivariable logistic regression model, adjusted for age, gender, race, income, health status, presence of chronic health condition, and functional limitation

†Employment status was dichotomized as employed/self-employed vs. all other responses

‡Employed enrollees who responded “Yes” to the question, “Has getting health insurance through the Healthy Michigan Plan helped you do a better job at work?”

§Out of work enrollees who strongly agreed or agreed that “Having health insurance through the Healthy Michigan Plan has made me better able to look for a job”

ǁEnrollees with a recent job change who strongly agreed or agreed that “Having health insurance through the Healthy Michigan Plan helped me get a better job”

We also conducted multivariable analyses examining the association between improved health and enrollees’ reported ability to seek a job. For enrollees who were out of work, those with improved physical or mental health since enrollment were more likely (aOR 2.82, 95% CI 1.93–4.10, p < 0.001) to report that HMP made them better able to look for a job. In addition, while those over age 50 were less likely to be employed, they were the age group most likely to report that HMP made them better able to look for a job (aOR 1.76, 95% CI 1.14–2.72, p = 0.01). For enrollees who had a recent job change, those with improved physical or mental health since enrollment were more likely (aOR 3.20, 95% CI 1.69–6.09, p < 0.001) to report that HMP helped them get a better job.

Qualitative Interview Findings: Improvements in Health and Ability to Work; Ongoing Barriers to Employment

In interviews, we asked enrollees about perceived changes in health since enrollment in HMP. Many interviewees reported improvements in physical, mental, or dental health since enrollment (Table 2). We also asked about changes in work and job seeking. Many interviewees attributed their ability to obtain or maintain employment to improved health because services covered by HMP led to detection and treatment of chronic health conditions that previously inhibited their job performance or ability to seek a job. After HMP enrollment, many interviewees reported being able to function better physically or mentally at work. Some enrollees reported improved confidence in job seeking after dental procedures that improved their appearance. However, other interviewees discussed ongoing barriers to work, including persistent poor health/illness, disability, caregiving responsibilities, and older age, including age discrimination by employers (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this mixed methods study examining changes in health and employment among enrollees in Michigan’s Medicaid expansion program, we found that many enrollees reported improved health, ability to work, and job seeking since enrollment. We were not able to assess longitudinal changes in employment status in this single cross-sectional study. However, in adjusted analyses, we found that enrollees with improved physical or mental health since enrollment were more likely to report improved ability to work, look for a job, or get a better job. This association between improvements in health and job outcomes after Medicaid expansion reported in both surveys and interviews was especially pronounced among older enrollees or those with chronic health conditions.

Overall, our findings demonstrate more positive job outcomes associated with Medicaid expansion than those seen in some other state33 and national studies.12–16 There may be several explanations for these differences. First, we studied different outcomes than prior studies. While much of the prior literature focuses on overall labor force participation or the number of working hours, we additionally focused on assessing changes in ability to work (presenteeism) and job seeking. Enrollees reported improvements in their ability to work (presenteeism), which may be important for employers and state economies, as the economic burden of illness in low-income workers is likely high.34 However, we found no significant changes in missed work days (absenteeism) after insurance enrollment, which is consistent with prior studies.35

Second, our study examined a different group than national population-level studies of non-elderly adults eligible for coverage expansion, which conducted secondary analyses of federal surveys such as the Current Population Survey or American Community Survey. Our focus on self-report of Medicaid expansion enrollees rather than the eligible working-age population may have allowed us to detect differences in the target group most likely to be impacted. Interestingly, the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment found positive impacts of self-reported health associated with obtaining pre-ACA Medicaid coverage, but no effects on employment.33, 36

Third, our study design used enrollee interviews and a survey focused on assessing perceived impact of the Medicaid expansion program, while the majority of other studies used federal economic surveys. Though this assessment was limited to cross-sectional assessments of enrollees’ perceived impact of the program, it is notable that our findings of favorable job outcomes were more consistent with findings from Ohio—the only other recent study from the viewpoint of individual Medicaid expansion enrollees.18 Our study added further depth by analyzing the relationships between expanded coverage, changes in health, and job outcomes, and portraying enrollees’ perspectives on these relationships in their own words.

There are several potential limitations to consider when interpreting our study findings. First, while the self-report of outcomes in our interviews and survey highlights enrollees’ experiences and perceived health, it may also be limited by recall bias and social desirability bias. It is also possible that some enrollees would feel inclined to report favorable impressions of the program. To minimize the potential for such biases, we emphasized the role of the study team as independent evaluators of the HMP program and ensured the confidentiality of survey and interview responses. In addition, we reviewed survey responses across all items/domains and found appropriate variability of survey responses, rather than a skewed distribution. Second, this was a single cross-sectional study conducted approximately 1–2 years after enrollees obtained coverage through Medicaid expansion, which limits causal inference based on perceptions of changes in job-related outcomes. Future planned longitudinal surveys will examine whether Medicaid expansion in Michigan was associated with increased rates of employment participation among enrollees over time. Third, while we did not have an available comparison group of similar individuals who did not gain Medicaid coverage, we were able to achieve a very high participation rate for Medicaid enrollees in the HMP program (including a survey response rate exceeding 50%, compared with response rates of 23–44% in other studies of low-income and Medicaid populations).37–40 Finally, the study was conducted in one large Midwestern state that pursued a Medicaid Section 1115 waiver. Findings could differ in other states, particularly if they have different program features or economic circumstances.

Despite these limitations, this study has important implications that inform the current policy debate over reforms to the Medicaid program, including reforms targeted “to improve [enrollees’] economic standing”.6 As state and federal policymakers consider different approaches for improving the health and economic circumstances of low-income enrollees—including expanding coverage, implementing job/skills training programs, or instituting work requirements41—it will be important to carefully consider favorable and unfavorable effects of current Medicaid expansion programs.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we found that at least a third of Medicaid expansion enrollees reported improvements in physical, mental, and dental health. A majority of respondents reported improved ability to work or seek a job, and one third of those who changed jobs reported HMP helped them obtain a better job. These reports were more likely among enrollees who reported improved health, particularly for older enrollees and those with chronic conditions. However, some enrollees faced persistent barriers to employment such as poor health, disability, caregiving responsibilities, and older age. Future research should assess longitudinal changes in health and employment outcomes associated with Medicaid expansion. Our findings suggest that Medicaid expansion may have long-term value to enrollees and the economies of expansion states, but that continued careful consideration of job-related outcomes is needed to inform states’ decisions about whether or how to implement work requirements in Medicaid programs.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(PDF 518 kb)

Acknowledgments

Contributors

We thank the following evaluation team members for their additional contributions to survey and interview development and administration: Lisa Szymecko, JD, PhD; Cengiz Salman, MA; Tolu Olorode, MSW, MUP; Zachary Rowe, BBA; and the members of the Community Advisory Board (Adnan Hammad, Global Health Research, Management and Solutions; Lynnette LaHahnn, AuSable Valley Community Mental Health Authority; Charo Ledón, Acción Buenos Vecinos; Raymond Neff, Spectrum Health; Jennifer Raymond, Mid Michigan Community Action; George Sedlacek, Marquette County YMCA; and Ashley Tuomi, American Indian Health and Family Services). We also thank Sarah Sugar, BA, for assistance with literature review, and Helen Levy, PhD, for thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Funding Source

The study was funded by a contract from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) to the University of Michigan to conduct an evaluation of the Healthy Michigan Plan, as required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) through a Section 1115 Medicaid waiver.

Prior Presentations

Preliminary findings were presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, April 2017, and at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting, New Orleans, LA, June 2017.

Funders

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) funded the study and approved the manuscript, but had no role in the conduct of the research, data analysis, interpretation of findings, or drafting of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of MDHHS.

Dr. Tipirneni is additionally supported by a K08 Clinical Scientist Development Award from the National Institute on Aging. Support was also provided to Dr. Kullgren by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service. Dr. Kullgren is a VA HSR&D Career Development awardee at the Ann Arbor VA. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Kullgren has received consulting fees from SeeChange Health and HealthMine, and a speaking honorarium from AbilTo, Inc. There are no other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Congressional Budget Office. Cost estimate: H.R. 1628, American Health Care Act of 2017. May 24, 2017. Accessed at https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/hr1628aspassed.pdf on 4 September 2017.

- 2.Congressional Budget Office. Cost estimate: H.R. 1628, Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017. June 26, 2017. Accessed at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52849 on 4 September 2017.

- 3.Congressional Budget Office. Preliminary analysis of legislation that would replace subsidies for health care with block grants. 2017 Sept. Accessed at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53126 on 26 September 2017.

- 4.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Current status of state Medicaid expansion decisions. 2017 Jan 1. Accessed at http://www.kff.org/health-reform/slide/current-status-of-the-medicaid-expansion-decision on 4 September 2017.

- 5.Singer PM, Nelson DB, Tipirneni R. Consumer-directed health care for Medicaid patients: past and future reforms. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(10):1592–1594. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS announces new policy guidance for states to test community engagement for able-bodied adults. Accessed at https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2018-Press-releases-items/2018-01-11.html on 22 May 2018.

- 7.Musumeci, M. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid and work requirements. 2017 Mar 23. Accessed at http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-and-work-requirements on 4 September 2017.

- 8.Antonisse L, Garfield R, Rudowitz R, Artiga S, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: updated findings from a literature review. 2017 Sept 25. Accessed at http://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review on 26 September 2017.

- 9.The Colorado Health Foundation. Assessing the economic and budgetary impact of Medicaid expansion in Colorado: FY 2015–16 through FY 2034–35. 2016 Mar. Accessed at http://www.coloradohealth.org/sites/default/files/documents/2017-01/Medicaid_ExecutiveSummary_ONLINE.pdf on 4 September 2017.

- 10.Deloitte Development LLC. Commonwealth of Kentucky Medicaid expansion report 2014. 2015 Feb. Accessed at http://jointhehealthjourney.com/images/uploads/channel-files/Kentucky_Medicaid_Expansion_One-Year_Study_FINAL.pdf on 4 September 2017.

- 11.Ayanian JZ, Ehrlich GM, Grimes DR, et al. Economic effects of Medicaid expansion in Michigan. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:407–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1613981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrett AB, Kaestner R, Gangopadhyaya A. Recent evidence on the ACA and employment: Has the ACA been a job killer? 2016 update. The Urban Institute, ACA Implementation — Monitoring and Tracking; 2017 Feb. Accessed at https://ssrn.com/abstract=2922288 on 4 September 2017.

- 13.Gooptu A, Moriya AS, Simon KI, et al. Medicaid expansion did not result in significant employment changes or job reductions in 2014. Health Aff. 2016;35:111–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung P, Mas A. Employment effects of the ACA Medicaid expansions. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 22540; 2016 Aug. Accessed at http://www.nber.org/papers/w22540.pdf on 4 September 2017.

- 15.Kaestner R, Garrett B, Chen J, et al. Effects of ACA Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and labor supply. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36:608–42. doi: 10.1002/pam.21993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy H, Buchmueller TC, Nikpay S. Health reform and retirement. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016; 2016 Sep 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Hall JP, Shartzer A, Kurth NK, et al. Effect of Medicaid expansion on workforce participation for people with disabilities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:262–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohio Department of Medicaid. Ohio Medicaid Group VIII assessment: a report to the Ohio General Assembly. 2016. Accessed at http://medicaid.ohio.gov/portals/0/resources/reports/annual/group-viii-assessment.pdf on 4 September 2017.

- 19.Rutledge MS. The interconnected relationships of health insurance, health, and labor market outcomes. Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, WP2016–2; 2016 Jul. Accessed at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2812211 on 4 September 2017.

- 20.Office of Governor Rick Snyder. Snyder making the case for Healthy Michigan at two town hall meetings. 2013 Aug 19. Accessed at http://www.michigan.gov/snyder/0,4668,7-277-57577_57657-310966%2D%2Drss,00.html on 4 September 2017.

- 21.Ayanian JZ. Michigan’s approach to Medicaid expansion and reform. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1773–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1310910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. Oakbrook Terrace (IL): AAPOR; 2016. Accessed at http://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf on 4 September 2017.

- 25.Lee S, Valliant R. Weighting telephone samples using propensity scores. Adv Tel Survey Methodol 2008:170–83.

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National health and nutrition examination survey. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm on 4 September 2017.

- 27.Center for Studying Health System Change. Health tracking household survey. 2009-10-16. Accessed at 10.3886/ICPSR26001.v1 on 4 September 2017.

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National health interview survey. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/index.htm on 4 September 2017.

- 29.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems. Accessed at https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/index.html on 4 September 2017.

- 30.U.S. Census Bureau. American community survey. Accessed at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs on September 4, 2017.

- 31.Guetterman TC, Fetters MD, Creswell JW. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:554–61. doi: 10.1370/afm.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research: SAGE. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baicker K, Finkelstein A, Song J, et al. The impact of medicaid on labor market activity and program participation: evidence from the oregon health insurance experiment. Am Econ Rev. 2014;104:322–8. doi: 10.1257/aer.104.5.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goetzel RZ, Long SR, Ozminkowski RJ, et al. Health, absence, disability, and presenteeism cost estimates of certain physical and mental health conditions affecting US employers. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46:398–412. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000121151.40413.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu X, Jensen GA. Does health insurance reduce illness-related worker absenteeism? Appl Econ. 2012;44:4591–603. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2011.593498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, et al. The Oregon experiment—effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1713–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ku L, Brantley E.Medicaid work requirements: who’s at risk? Bethesda (MD): Health Affairs Blog; 2017 Apr 12. Accessed at http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2017/04/12/medicaid-work-requirements-whos-at-risk on 4 September 2017.

- 38.Askelson NM, Golembiewski EH, Baquero B, et al. The importance of matching the evaluation population to the intervention population: using Medicaid data to reach hard-to-reach intervention populations. Eval Program Plann. 2017;60:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gidengil C, Parast L, Burkhart Q, et al. Development and implementation of the family experiences with coordination of care survey quality measures. Acad Pediatr. 2017; 2017 Mar 31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Sommers BD, Maylone B, Nguyen KH, et al. The impact of state policies on ACA applications and enrollment among low-income adults in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Texas. Health Aff. 2015;34:1010–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Call KT, McAlpine DD, Garcia CM, et al. Barriers to care in an ethnically diverse publicly insured population: is health care reform enough? Med Care. 2014;52:720–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 518 kb)