Summary

Objective:

This study examines medication adherence among women with epilepsy via use of an electronic diary, as part of a prospective multicenter observational study designed to evaluate fertility in women with epilepsy (WWE) versus age-matched controls.

Methods:

WWE and healthy age-matched controls, seeking pregnancy, were given an iPod Touch using a customized mobile application (the WEPOD App) for daily data tracking. Eighty-six WWE tracked seizures and antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Tracking of nonepilepsy medications was optional. Diary data were counted from enrollment date until date of delivery, or up to 12 months if pregnancy was not achieved. Each day that subjects reported missing one or more AED was counted as nonadherence. Because adherence can only be determined in women who track consistently, we elected to include adherence data only for women who tracked >80% of days in the study.

Results:

Approximately 75% of WWE tracked >80% of days and were included in medication adherence data analysis. In this group, medication adherence rate was 97.71%; 44% of women admitted to missing an AED on at least 1 day. Among the subgroup of WWE who recorded nonepilepsy medications, AED adherence rate was 98.56%, versus 93.91% for non-AEDs.

Significance:

The 75% compliance rate with an electronic diary suggests that it may be useful to track medication adherence in future studies and in the clinical setting. In those who tracked, the observed medication adherence rate was considerably higher than the 75% adherence rate seen in previous epilepsy studies. This might be explained in part by selection bias, but may also result from properties of the diary itself (daily reminders, real time feedback given to the provider). Women reported a higher rate of adherence to AEDs than to other prescribed medications and supplements, suggesting that perceived importance of medications likely influences medication adherence, and warrants future study.

Keywords: Medication adherence, Pregnancy, Electronic diary, Epilepsy

Epilepsy lends itself well to the study of medication adherence in that it is a chronic, often lifelong illness with a relatively frequent and measurable primary outcome (seizures), in contrast to other chronic diseases such as hypertension, which may or may not lead to an associated negative outcome such as stroke. Failure to take epilepsy medications as prescribed may lead to severe consequences.1 Yet, despite the dangers associated with adherence failure, previous studies have shown that patients with epilepsy are only about 75% adherent to antiepileptic drug (AED) regimens.2,3 One population that is considered particularly at risk for both nonadherence and the consequences of nonadherence, are women with epilepsy (WWE) who are pregnant.4 Women may elect not to take AEDs because they are nauseated, and unable to ingest medication, or because they are worried that medication will injure the fetus.5 Unfortunately, if nonadherence leads to seizure breakthroughs, the consequences may be felt by both mother and baby.

Barriers to medication adherence in epilepsy and monitoring of medication adherence present a tremendous challenge to clinicians and to clinical researchers. Poor adherence has been shown to negatively impact healthcare spending by resulting in more emergency room visits and hospitalizations,6 and may result in incomplete seizure control and increased risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).7,8 Pregnant women with epilepsy may have a higher risk of death, and this may relate to nonadherence to medication.9 Although incompletely understood, it is thought that AED adherence is affected by multiple factors, including the sporadic nature of epilepsy symptoms, the lack of immediate consequences of missing doses, and the variable seizure frequency within each patient’s disease course.10 In addition, patients with epilepsy often have cognitive and memory impairments associated with their disease, which may add to medication errors.

The Women with Epilepsy: Pregnancy Outcomes and Delivery (WEPOD) trial is a four-center prospective observational study designed to evaluate fertility among WWE compared to a group of age-matched controls. Trial participants use a specially designed electronic diary mobile application that provides an opportunity to examine medication adherence among this group of WWE. WEPOD participants were given a mobile device (an iPod Touch), and taught to use a mobile application (The WEPOD App) to track menstrual cycles and sexual activity, and for WWE, to also track seizures and daily medication use. Some of these women also tracked use of nonepilepsy medications, which consisted primarily of folic acid and prenatal vitamins. The mobile application gives the participants a daily reminder to enter data, and data are stored centrally, allowing researchers to monitor use on a regular basis. There is limited literature addressing the utility of electronic diaries for tracking medication adherence. Most previous studies on medication adherence have used either traditional paper diaries, or medication event monitor systems (MEMS), which involve a microprocessor installed in the lid of a pill bottle. The MEMS cap device is a useful research tool, but is not practical for routine clinical use.11 We used the data from the WWE enrolled in our study to determine whether an electronic diary was successful in tracking medication adherence, and to assess adherence prior to and during pregnancy in our enrolled patients.

Methods

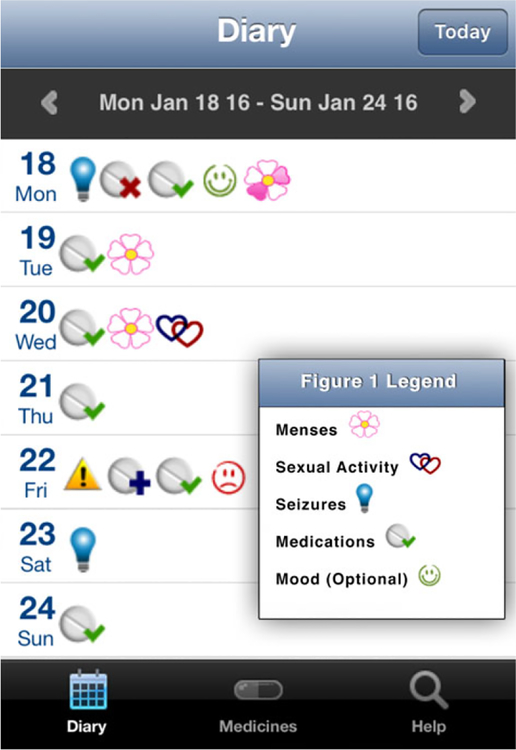

WWE and healthy age-matched controls, seeking pregnancy, were enrolled within 6 months of contraceptive discontinuation. WEPOD participants were given a mobile device (an iPod Touch) and trained to use a customized mobile application (the WEPOD App) for daily data tracking. All subjects and controls were given the option of using paper diaries instead of the electronic application, but only one (control patient) chose this option. Participants in both groups were given daily “pop-up” reminders to enter data. The WEPOD App is a personalized diary that includes menstrual cycle and sexual activity logs for all participants and seizure and medication diaries for WWE (Fig. 1). The app was prepopulated with all AEDs used by the women at enrollment, including intended schedule of administration. Each day women could indicate use by clicking on the appropriate icon “I took it,” “I missed it,” or “I took extra” for each prescribed dose (see Fig. 2). There was also an optional mood tracking option for WWE. The app is connected to a cloud-based system that allows for data entry into a cloud database, and provides continuous central data monitoring. WWE were instructed to track AEDs, but tracking of other nonepilepsy medications was optional. All subjects were instructed to track data daily for the duration of time enrolled in the study; diary data were counted from date of enrollment until date of delivery, or up to 12 months if pregnancy was not achieved. If a day of tracking was missed, it could be backfilled at any time.

Figure 1.

Epilepsy group diary. Epilepsia ©ILAE

Figure 2.

Medication data entry. Epilepsia ©ILAE

Subjects indicated whether medications were taken at prescribed times. Clicking the icon of a pill with a green check indicated “I took it,” a pill with a red check indicated “I missed it,” and a pill with a blue plus indicated “I took extra.”

Medication adherence data from the WWE group were electronically reviewed and counted from each participant’s data log. Each day on which subjects reported missing one or more doses of AEDs was counted as nonadherence. For the purposes of this analysis, taking an extra dose the same day or the day after the missed dose was still considered to be nonadherence. Days on which participants did not enter medication data were also counted. Some WWE also chose to record use of non-AED medications, which were counted separately.

Because adherence can be determined only in women who track consistently, we elected to only include adherence data for women who tracked >80% of days in the study.

Results

Diary adherence

Ninety WWE enrolled in the study and met entry criteria. Of these 90 women, 4 were ineligible for medication adherence analysis because they were not prescribed an AED during some or all of the days enrolled in the study. Of the eligible 86 subjects, 66 (76.74%) tracked >80% of total possible days and were included in adherence analysis (Table 1). Collectively, these women who were >80% compliant with the diary tracked 98.91% of possible days. The group of 20 women who tracked <80% of enrolled days in the study collectively tracked an average of 43% of days (median 33%), and percentage of days tracked ranged from 0% to 76%. These women reported taking AEDs as prescribed on 99.66% of recorded days, and only 5 of these 20 women admitted to any missed doses of AEDs. A total of 16 women in the WWE group dropped out of the study; of these dropouts, 6 had tracked <80% of days enrolled in the study.

Table 1.

Demographics of WWE

| Diary adherent group (n = 66) | Diary nonadherent group (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean | 32.05 | 32 |

| Median | 32 | 32 |

| Range | 25–40 | 25–39 |

| Race (%) | ||

| Asian | 4.55 (3) | 10 (2) |

| African American/black | 0 (0) | 5 (1) |

| White | 87.87 (58) | 85 (18) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1.51 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Other/mixed | 6.06 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 13.64 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 86.36 (57) | 100 (20) |

| Highest education level (%) | ||

| Less than high school | 1.52 (1) | 0 (0) |

| High school | 9.09 (6) | 10 (2) |

| Some college | 12.12 (8) | 5 (1) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 31.81 (21) | 3.5 (7) |

| Advanced degree | 42.42 (28) | 50 (10) |

| Missing | 1.52 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Employment status (%) | ||

| Student (not currently employed) | 1.52 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Unemployed | 21.21 (14) | 15 (3) |

| Part-time | 10.61 (7) | 10 (2) |

| Full-time | 63.62 (42) | 70 (14) |

| Missing | 3.03 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Smoking status (%) | ||

| Present history | 10.61 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Past history | 13.64 (9) | 10 (2) |

| No history | 72.73 (48) | 85 (17) |

| Missing | 3.03 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Seizure reported in the past 9 months(%) | ||

| Yes | 39.40 (26) | 50 (10) |

| No | 56.06 (37) | 45 (9) |

| Missing | 4.54 (3) | 5 (1) |

Medications used

Table 2 lists the number of subjects for each AED type, and illustrates that the majority of WWE were taking lamotrigine either as monotherapy or in combination with another AED, followed by levetiracetam as the second most common agent. The majority of WWE were taking AEDs with only b.i.d. dosing (42 of 66), with 10 of 66 taking AEDs with only daily dosing, and the other 12 taking either AEDs with a combination of dosing schedules or t.i.d. scheduling.

Table 2.

AED regimens

| AED regimen | Number of subjects (total 66) | % Collective days with missed AED doses |

|---|---|---|

| Lamotrigine monotherapy | 29 | 2.28 |

| Levetiracetam monotherapy | 19 | 2.76 |

| Oxcarbazepine monotherapy | 5 | 1.13 |

| Carbamazepine monotherapy | 3 | 6.68 |

| Lamotrigine/carbamazepine | 2 | 0/0 |

| Pregabalin monotherapy | 1 | 0 |

| Zonisamide monotherapy | 1 | 0.28 |

| Felbamate monotherapy | 1 | 1.13 |

| Lamotrigine/levetiracetam | 1 | 0/0 |

| Lamotrigine/lorazepam | 1 | 0.27/0 |

| Lacosamide/levetiracetam/oxcarbazepine | 1 | 0/0/0 |

| Levetiracetam/carbamazepine | 1 | 0/0 |

| Lamotrigine/phenytoin | 1 | 0/1.44 |

Medication adherence

Participants in the WWE group who tracked >80% of possible days reported taking all AEDs as prescribed on 97.71% of days. Forty-four percent of patients overall had at least 1 day recorded on which they admitted missing a dose. The number of days on which at least one dose was missed ranged from 0 to 98, with a mean of 6.7 days and a median of 0. Among the diary nonadherent group, the reported percentage of medication adherence on days they tracked was 99.84%, with only 5 of 20 or 25% of the diary nonadherent subgroup reporting at least 1 day on which an AED dose was missed. For the entire group of WWE that provided any medication data (n = 86), the overall reported percentage of days on which AEDs were taken as prescribed was 97.76%.

Pregnancy and medication adherence

Of the 66 women studied in the medication adherence analysis, 42 achieved pregnancy. Adherence to AEDs was examined in this subgroup, and an overall AED adherence rate of 98.02% was seen, which was comparable to the 97.71% adherence rate in the group as a whole. When comparing days during which these women were pregnant versus not yet pregnant, adherence rates were again similar, with medications taken as prescribed on 98.03% of days while pregnant, and 98.02% of days when not yet pregnant.

Non-AED medication adherence

A subgroup of 41 of the 64 WWE included in the medication adherence analysis opted to also track non-AEDs along with AEDs. Among women in this subgroup, overall AED adherence rate was 98.56%. Participants recorded having missed at least one dose of AED, while still taking non-AEDs on 0.49% of days, and recorded missing a dose of AED as well as at least one non-AED on 3.97% of days. They recorded having missed at least one dose of non-AEDs, while taking their AEDs on 3.48% of days. The overall adherence rate with non-AEDs among this subgroup was 93.91%, with 30% of these women reporting at least 1 day on which they did not take a non-AED. The number of days of reported missed doses ranged from 0 to 21, with an average of 12.2 days. These results are summarized in Table 3. Non-AED medications recorded on an optional basis by WWE are listed in Table 4. Only medications that were prescribed to be taken on a daily basis were counted in adherence analysis.

Table 3.

Adherence results from subgroup of WWE (n = 41) reporting both AED and non-AED adherence

| Overall AED adherence (%) | 98.56 |

| Overall non-AED adherence (%) | 93.91 |

| % days on which AEDs were taken as prescribed, but non-AEDs were missed | 3.48 |

| % days non-AEDs were taken as prescribed, but AEDs were missed | 0.49 |

| % days both AEDs and non-AEDs were missed | 3.97 |

Table 4.

Non-AED medications

| Non-AED medications recorded | Number of subjects (total 41) |

|---|---|

| Folic acid + multivitamins/prenatal vitamins | 16 |

| Folic acid only | 8 |

| Folic acid + prenatal vitamins + DHA + Xanax (prescribed nightly for anxiety, not epilepsy) | 1 |

| Folic acid + prenatal vitamins + DHA | 1 |

| Folic acid + prenatal vitamins + levothyroxine | 1 |

| Folic acid + Clomid | 1 |

| Folic acid + levothyroxine | 1 |

| Folic acid + acyclovir + Pepcid | 1 |

| Folic acid + prenatal vitamins + Advair + Singulair | 1 |

| Folic acid + prenatal vitamins + iron + vitamin D | 1 |

| Folic acid + prenatal vitamins + iron | 1 |

| Folic acid + prenatal vitamins + iron + Zyrtec | 1 |

| Folic acid + prenatal vitamins + enoxaparin | 1 |

| Folic acid + vitamin BI2 | 1 |

| Folic acid + vitamin B complex | 1 |

| Folic acid + prenatal vitamins + Claritin | 1 |

| Folic acid + prenatal vitamins + vitamin D | 1 |

| Folic acid + prenatal vitamins + escitalopram | 1 |

| Folic acid + nifedipine + nortriptyline | 1 |

DHA, docosahexaenoic acid.

Of the 40 women tracking non-AED use, 27 became pregnant during the study. Among women in this subgroup, a collective total of 288 prepregnancy days (or 3.30% of nonpregnant days) was recorded on which one or more doses of non-AEDs were missed, and 64 days during pregnancy (or 0.73% of pregnant days) were recorded on which one or more doses of non-AEDs were missed (Table 4).

Discussion

We assessed compliance in women with epilepsy planning pregnancy who were using an electronic diary to track seizures and medication compliance. The disadvantage of this or any other compliance device, is that in order for it to be informative, it has to be employed regularly by the patient. One finding from the study was that of the 86 patients who were taking AEDs, about three fourths were able to regularly adhere to electronic tracking. Of those who did, adherence to medications was very high. This issue is present with every type of compliance assessment. Pill counting is another strategy often employed by physicians and researchers to assess medication adherence, but it has several limitations. The number of pills taken in a given time interval does not provide any information to the researcher/clinician about dose timing. In addition, patients may discard pills or set pills aside prior to visits to appear to be adherent to the medication regimen.12 The MEMS device involves a microprocessor installed in the lid of a pill bottle, and counts the number of times the bottle is opened, and a dose presumably taken.1–3 The cap can be manipulated, or patients can remove pills for multiple doses at one time, creating a false impression of noncompliance.

A possible explanation for the high reported adherence rate is that the subjects falsely reported better adherence to AEDs. Multiple studies have suggested that patients typically report good rates of adherence to their doctor, with most reporting either missing no doses or one to two per month.13,14 In a questionnaire distributed to neurologists all over the United States to be placed in waiting rooms, 661 patients completed and returned the questionnaires and collectively reported a mean of approximately two missed doses per month. Only 32% of these patients reported that they had informed their doctors about missed medication doses.3 However, in fact, telling a “diary” may be more akin to the waiting room questionnaire and may lead to more truthful information. Approximately half of the women in our study admitted to at least one occasion on which they missed an AED dose.

In further support of the accuracy of diary reports was the interesting discrepancy between reported rates of adherence to AEDs versus non-AEDs within the subgroup of WWE tracking medications other than AEDs. Despite potential consequences associated with missing folic acid or vitamin supplementation, the women reported taking all scheduled doses of AEDs on 98.52% of days, whereas they reported adherence with non-AEDs on 93.76% of days. The fact that the participants recorded having taken some of their medications and not others may be evidence that they are reporting honestly, and that they are prioritizing one medication over another and choosing not to take the supplements. On >98% of days on which WWE collectively reported missing non-AEDs, the missed medications were either folic acid or vitamins. Most non-AEDs tracked were vitamins and supplements, rather than prescribed medications for chronic medical conditions. The adherence rates prepartum and during pregnancy suggest that the women may have given higher priority to these supplements during pregnancy than before pregnancy. Very few women were taking medications for chronic medical conditions during the study. Only three women reported missing non-AED prescriptions that were not supplements (one missed an anxiolytic several times, another missed an antihistamine, and the third a thyroid replacement on a few occasions).

The 97.71% AED adherence rate observed in WEPOD women who were tracking well is well above the previously mentioned AED adherence rate of approximately 75% seen in prior studies of antiepileptic medication adherence.1,2 One might argue that the patients in this study were more highly motivated to adhere to medication regimens than the average epilepsy patient, since they not only faced the typical consequences associated with seizures, but were also motivated by trying to achieve pregnancy under high-risk conditions. Few studies address the effect of pregnancy on medication adherence in patients with chronic medical conditions. One study used self-report questionnaires to assess antiretroviral medication adherence in women with HIV in the partum and postpartum periods, and showed a higher rate of complete adherence in the partum period compared to the postpartum period (61% vs. 44%).15 Women in our study who became pregnant did not appear to have a different adherence rate before or during their pregnancies, but it is possible that they may have a lower adherence rate when not actively seeking pregnancy.

The electronic device itself may have aided in reminding patients to take their medications, especially considering that the device has a built-in daily “pop-up” reminder. Electronic diaries have many potential advantages over traditional paper diaries, including real-time data transfer, electronic reminders, convenience, and time-stamping.11 In our study, participants were able to back-fill their diaries, which may impact accuracy, but time-stamping is a way to assess when participants actually use their diaries and could be useful in future research. A 2002 study compared use of paper diaries to electronic diaries as a tool to track pain scores among a group of 80 patients with chronic pain. The electronic diary included timed alerts as a reminder to input information. Results showed significantly improved diary adherence in the electronic diary group.16 Although the study did not address medication adherence, it demonstrates the utility of use of real-time reminders in electronic diary use, and may be applicable to not only diary adherence but medication adherence. Also as noted earlier, 75% of the WWE were >80% adherent with the diary, and selecting this group for analysis may represent a selection bias of the patients who are more adherent in general, to both use of the diary and to taking medications as prescribed. Adherence is defined and assessed differently in different studies, and limits the ability to compare medication adherence rates between studies.

The device also provides the study investigators with real-time information about patients’ medication adherence and seizure frequency, and allows the physicians and investigators to identify problems between visits and contact the patients to potentially intervene. Future studies using this or a similar electronic tracking device may further elucidate the role of these devices with daily reminder alerts as an aid in improving medication adherence. This tracking device may also prove to be useful in the clinic. Although it remains to be seen whether patients would be willing to use an electronic diary on a long-term basis, the ubiquity and accessibility of electronic devices and “apps” makes them more likely to be integrated into a daily routine. Furthermore, there are many instances where electronic devices might be clinically useful for a discrete period, such as during a pregnancy, when it may be useful to monitor compliance and review it at visits. This might allow a discussion of why medication was missed on certain days.

One can infer that the discrepancy in reported rate of medication adherence implies that woman feel that their AEDs are more important than other medication, and that missing them may carry graver consequences than missing the nonepilepsy medications. Tracking of non-AEDs was optional in this study (only 62.5% of subjects tracked non-AEDs), but it would be valuable to more closely examine this discrepancy in future studies with a larger sample size. Further examination of the root of motivation behind taking different types of medications may allow physicians to better understand and ultimately improve patient adherence to medications.

Conclusion

The majority of women planning pregnancy can maintain electronic diaries. Compliance for AEDs was excellent both prior to and during pregnancy among those who tracked >80% of days. Electronic diaries can be employed both in clinical trials and in practice to monitor adherence. The fact that some women took their AEDs but not their folic acid and supplements suggests that perceived importance of medication is one element in compliance.

Key Points.

This study examines medication adherence among women with epilepsy who are seeking pregnancy, via use of an electronic tracking diary

Seventy-five percent of women were compliant with the electronic diary, tracking medication use on >80% of days; these women were included in adherence analysis

Diary-compliant women reported high rates of AED medication adherence (97.1%)

Subjects who tracked both AEDs and nonepilepsy medications reported a higher rate of adherence with AEDs than with other medications

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Milken Family Foundation, the Epilepsy Therapy Project, and the Epilepsy Foundation, who provided funding for WEPOD. We would like to thank Nicolette D. Ernst, graphic artist, for editing the figure images used in this paper.

Biography

Lia de Leon Ernst is an assistant professor of neurology specializing in epilepsy at OHSU, Portland, Oregon.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

The Epilepsy Study Consortium pays Dr. Jacqueline French’s university employer for her consultant time related to Acorda, Adamas, Alexza, Anavex, BioPharm Solutions, Concert, Eisai, Georgia Regents University, GW Pharma, Marathon, Marinus, Neurelis, Novartis, Pfizer, Pfizer-Neusentis, Pronutria, Roivant, Sage, SciFluor, SK Life Sciences, Takeda, UCB Inc., Ultragenyx, Upsher Smith, Xenon Pharmaceuticals, Zynerba grants; and research from Acorda, Alexza, LCGH, Eisai Medical Research, Lundbeck, Pfizer, SK Life Sciences, UCB, Upsher-Smith, Vertex, and grants from National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), Epilepsy Therapy Project, Epilepsy Research Foundation, and Epilepsy Study Consortium. She is on the editorial board of Lancet Neurology, Neurology Today, and Epileptic Disorders, and was an Associate Editor of Epilepsia, for which she received a fee. Dr. Cynthia Harden has received support from, and/or has served as a paid consultant for, UpToDate and Wiley Publishing. Dr. Eyal Bartfeld is employed by Irody, Inc., who is the developer of the electronic epilepsy diary that was used in this study. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

References

- 1.Cramer JA, Mattson RH, Prevey ML, et al. How often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment technique. JAMA 1989;261:3273–3277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claxton AJ, Cramer JA, Pierce C. Medication compliance: the importance of the dosing regimen. Clin Ther 2001;23:1296–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cramer JA, Glassman A, Rienzi V. The relationship between poor medication compliance and seizures. Epilepsy Behav 2002;3:338–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawicki E, Stewart K, Wong S, et al. Medication use for chronic health conditions by pregnant women attending an Australian Maternity Hospital. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2011;51:333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olesen C, Søndergaard C, Thrane N, et al. Do pregnant women report use of dispensed medications? Epidemiology 2001;12:497–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faught E, Duh MS, Weiner JR, et al. Nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs and increased mortality: findings from the RANSOM study. Neurology 2008;71:1572–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson GM, McLean S, Millingen KS. A randomised trial of strategies to improve patient compliance with anticonvulsant therapy. Epilepsia 1984;25:412–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams J, Lawthom C, Dunstan FD, et al. Variability of antiepileptic medication taking behaviour in sudden unexplained death in epilepsy: hair analysis at autopsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:481–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDonald SC, Bateman BT, McElrath TF, et al. Mortality and morbidity during delivery hospitalization among pregnant women with epilepsy in the United States. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:981–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faught E Adherence to anti epilepsy drug therapy. Epilepsy Behav 2012;25:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher RS, Blum DE, DiVentura B, et al. Seizure diaries for clinical research and practice: limitations and future prospects. Epilepsy Behav 2012;24:304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown I, Sheeran P, Reuber M. Enhancing antiepileptic drug adherence: a randomized controlled trial. Epilepsy Behav 2009;16:634–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buck D, Jacoby A, Baker GA, et al. Factors influencing compliance with antiepileptic drug regimes. Seizure 1997;6:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mellins CA, Chu C, Malee K, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral treatment among pregnant and postpartum HIV-infected women. AIDS Care 2008;20:958–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone AA, Shiffman S, Schwartz JE, et al. Patient compliance with paper and electronic diaries. Control Clin Trials 2003;24:182–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]