Abstract

Angiogenesis requires co-ordination of multiple signalling inputs to regulate the behaviour of endothelial cells (ECs) as they form vascular networks. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is essential for angiogenesis and induces downstream signalling pathways including increased cytosolic calcium levels. Here we show that transmembrane protein 33 (tmem33), which has no known function in multicellular organisms, is essential to mediate effects of VEGF in both zebrafish and human ECs. We find that tmem33 localises to the endoplasmic reticulum in zebrafish ECs and is required for cytosolic calcium oscillations in response to Vegfa. tmem33-mediated endothelial calcium oscillations are critical for formation of endothelial tip cell filopodia and EC migration. Global or endothelial-cell-specific knockdown of tmem33 impairs multiple downstream effects of VEGF including ERK phosphorylation, Notch signalling and embryonic vascular development. These studies reveal a hitherto unsuspected role for tmem33 and calcium oscillations in the regulation of vascular development.

Calcium signalling downstream of VEGF is essential for VEGF-induced angiogenesis. Here Savage et al. show that Transmembrane Protein 33 (TMEM33) is required for angiogenesis and the endothelial calcium response to VEGF, revealing a function for TMEM33 in multicellular organisms.

Introduction

The formation of a complex vascular network is an essential process during embryonic development, which is vital for growth of tissues and is frequently dysregulated during disease in the adult. Endothelial cells (ECs) line the inner lumen of blood vessels and their organisation into complex branching networks requires co-ordination of molecular outputs coupled to specific cellular behaviours via a process primarily orchestrated by signalling from vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)1.

VEGF is a morphogen that signals via different ligands to induce motile and invasive behaviour, which drives blood vessel sprouting. VEGFA primarily controls angiogenesis from arteries via its cognate receptor VEGFR2/KDR, whereas VEGFC promotes sprouting from veins via VEGFR3/FLT42. Migrating ECs extend filopodia to sense VEGF signals via Kdr (VEGFR2), as they form a new sprouting vessel3. Leading angiogenic ECs are termed tip cells, which upregulate dll4 transcription, inducing Notch signalling in neighbouring cells, and this acts to limit excessive angiogenic sprouting4. Neighbouring Notch-expressing cells join the sprout as stalk cells, which in zebrafish tend to exhibit reduced proliferative capacity compared with tip cells4,5.

VEGFA has been shown to promote proliferation of ECs in vitro via VEGFR2-mediated activation of the RAS/RAF/ERK pathway without affecting migration6. Others, however, have shown that inhibition of ERK phosphorylation in vivo inhibits EC migration but not proliferation during angiogenesis7. ERK activation is induced via PLCG1 phosphorylation in vitro8, which generates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). IP3 subsequently activates inositol triphosphate receptor (IP3R) Ca2+ channels within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to increase cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations and activate protein kinase C to phosphorylate ERK9. ERK activation is required to promote angiogenesis and has been shown to promote expression of tip cell markers including dll47,10 and flt47. VEGF and Notch therefore balance formation of tip and stalk cells within developing blood vessels and modulate the relative migration and proliferation of ECs during angiogenesis11. Ca2+ is a universal secondary messenger, which achieves specificity using complex signalling modalities. These include encoding information to activate cellular responses within cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations12. How EC Ca2+ oscillations integrate complex molecular outputs to precisely control discrete cellular behaviours in a developing vascular network remains unknown.

ECs are generally thought to be non-excitable and as such utilise store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) as their primary means to maintain Ca2+ levels in the ER after influx13,14. The principal trigger for SOCE activation occurs when intracellular calcium stores with the ER are depleted and these are refilled via interaction of TRPC1 and ORAI1 on the plasma membrane with ER-resident STIM1, which form the calcium-release activated channel15–18. SOCE relies on modulation of the actin cytoskeleton, which requires Ca2+-dependent proteins for ER motility19.

We have identified transmembrane protein 33 (TMEM33) as a component of the ER Ca2+ signalling machinery required for angiogenesis. TMEM33 is a three-pass transmembrane domain protein conserved throughout evolution with two paralogues in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pom33 and Per33, showing enrichment in the nuclear pore and ER, respectively20,21. In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the TMEM33 orthologue Tts1p contributes to maintenance of the cortical ER network22. Human TMEM33 has been shown to localise to the nuclear envelope and ER in vitro, where it has been suggested to regulate the tubular structure of the ER by suppressing the membrane-shaping activity of reticulons23,24. However, its function within the ER in multicellular organisms remains unknown.

Here we describe the first characterisation of tmem33 in a multicellular organism and show that tmem33 is required in an EC-specific manner for Vegfa-mediated Ca2+ oscillations, to promote angiogenesis in zebrafish embryos. The requirement for tmem33 during the response to VEGF is conserved from zebrafish to humans. Furthermore, tmem33-mediated endothelial Ca2+ oscillations are critical for formation of endothelial filopodia and contribute to activation of ERK and induction of Notch signalling to co-ordinate vascular morphogenesis.

Results

tmem33 knockdown impairs vascular and pronephric development

We find tmem33 is expressed ubiquitously during zebrafish segmentation (Fig. 1a–c) and by 26 h post fertilisation (hpf) is enriched in the trunk vasculature and pronephros (Fig. 1d). TMEM33 expression has been previously identified within the nuclear envelope and ER in human cells23,24. We expressed a full-length C-terminal tmem33-EGFP fusion messenger RNA in developing zebrafish embryos and found Tmem33-EGFP fusion protein to localise to structures indicative of nuclear envelope (Fig. 1e–g, blue arrowheads) and ER (Fig. 1e–g, white arrowheads) of ECs within the caudal artery.

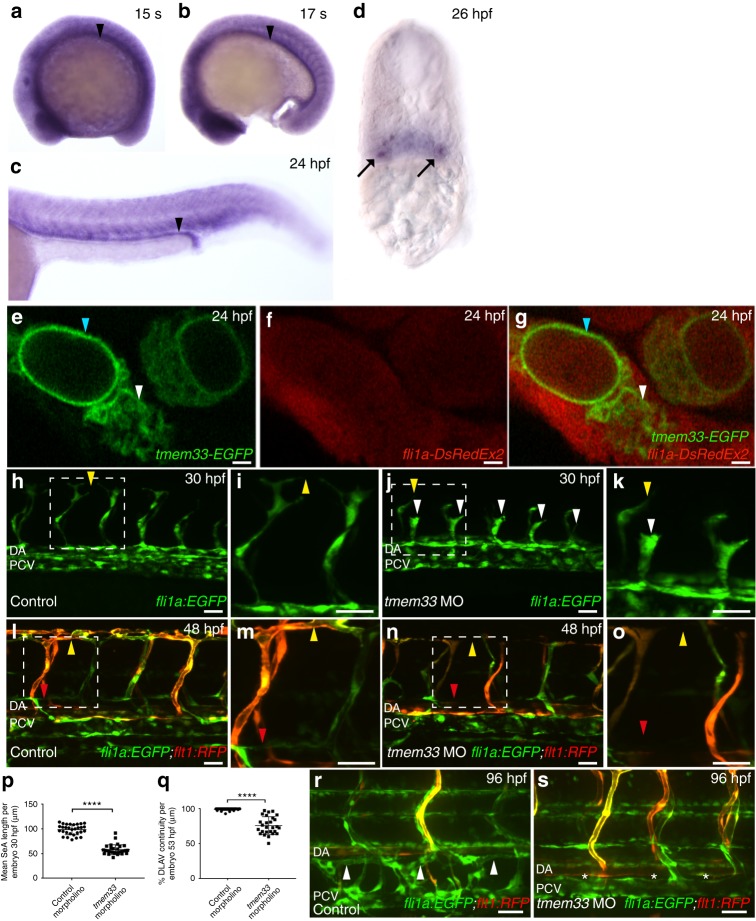

Fig. 1.

tmem33 knockdown inhibits angiogenesis and localises to the ER in ECs. a–d tmem33 is expressed ubiquitously during segmentation, but displays enrichment in the pronephros (black arrowheads) and somite boundaries, which is more pronounced from 24 hpf. Pronephric expression is evident in 26 hpf transverse sections (black arrows). e–g Tmem33-EGFP protein localises to the nuclear envelope (blue arrowheads) and ER (white arrowheads) within the caudal artery in fli1a:DsRedEx2 embryos (Scale bars 1 µm). h–k tmem33 morphants injected with 0.4 ng morpholinos display delayed migration of Tg(fli1a:egfp) positive SeAs, which stall at the horizontal myoseptum (j, k, white arrowheads), compared with control Tg(fli1a:egfp) positive morphants (h, i), which begin to anastomose by 30 hpf (yellow arrowheads) (scale bars 50 µm). l–o By 48 hpf, Tg(fli1a:EGFP;−0.8flt1:RFP) tmem33 morphant SeAs complete dorsal migration, but display incomplete DLAV formation (n, o, yellow arrowheads) and lack lymphatic vasculature (red arrowheads). At 48 hpf Tg(fli1a:EGFP; −0.8flt1:RFP) control morphants display secondary angiogenesis (l, m, yellow arrowheads) and parachordal lymphangioblasts (red arrowhead) (scale bars 50 µm). p tmem33 morphants injected with 0.4 ng morpholinos display reduced SeA length at 30 hpf (t-test ****p = < 0.0001; t = 4.075; DF = 24. n = 3 repeats, 10 embryos per group). q tmem33 morphants injected with 0.4 ng morpholinos display incomplete formation of DLAV (t-test ****p = < 0.0001; t = 5.618; DF = 28. n = 3 repeats, 9 or 10 embryos per group). r, s Thoracic duct formation is impaired in tmem33 morphants injected with 0.4 ng morpholinos (white asterisks), compared with control morphants (white arrowheads) (scale bars 50 µm). DA, dorsal aorta; PCV, posterior cardinal vein. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

To knock down tmem33 expression and establish its function during embryonic development, we next used two splice blocking morpholinos targeting exon 3, (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). All experiments were conducted using co-injection of both morpholinos. tmem33 morphants exhibited reduced segmental artery (SeA) length compared with controls (Fig. 1h-k, white arrowheads, p). By 30 hpf, SeAs in control morphants had reached the dorsal roof of the neural tube and begun to sprout laterally to form the dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessel (DLAV) (Fig. 1h, i yellow arrowhead), whereas tmem33 morphants often displayed abnormal spade-shaped tip cell morphology (Fig. 1k, white arrowhead) and were observed to stall at the level of the horizontal myoseptum. Consistent with this, tmem33 morphants displayed reduced SeA migration rate (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d, yellow arrowheads, Supplementary Fig. 2e). Expression of an arterial marker Tg(0.8flt1:RFP)25 in tmem33 morphants was indistinguishable from controls and restricted to the dorsal aorta (DA) and SeAs from day 1, suggesting the DA was correctly specified in tmem33 morphants (Fig. 1l, n). Onset of circulation and blood flow was normal in tmem33 morphants (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Movies 1–3). Despite this early delay in sprouting angiogenesis, by 48 hpf, most SeAs in tmem33 morphants had completed their dorsal migration, but many failed to migrate laterally, resulting in a primitive and discontinuous DLAV (Fig. 1l–o, yellow arrowheads, q). In addition, tmem33 morphants displayed absent parachordal lymphangioblasts (Fig. 1l, n, red arrowheads). The thoracic duct (TD) is the first major lymphatic vessel to develop in zebrafish26 and forms by ventral migration of parachordal lymphangioblasts. In keeping with the absence of parachordal lymphangioblasts, the TD was absent in tmem33 morphants (Fig. 1r, s, asterisks).

tmem33 knockdown reduces EC Ca2+ oscillations and filopodia

VEGF signalling is essential for SeA formation in zebrafish7,27–31 and lymphatic development26,32–36. Although TMEM33 has never been implicated in angiogenesis or VEGF signalling, the similarity of the phenotype of embryos with loss-of-function of tmem33 or VEGF signalling led us to hypothesise that tmem33 may regulate VEGF signalling in ECs. Furthermore, as VEGF increases EC intracellular Ca2+ 37, which is dependent upon the interaction of plasma membrane proteins with ER-resident proteins via SOCE16,38, we also postulated that tmem33 may regulate VEGF-induced EC Ca2+ signalling, given its indicative expression in the ER (Fig. 1e–g).

To determine the effect of tmem33 knockdown on EC calcium signalling in vivo, we generated an endothelial Ca2+ reporter line Tg(fli1a:gal4FFubs3;uas-gCaMP7ash392), hereafter referred to as fli1a:gal4FFubs3;uas-GCaMP7a. Recently, a similar transgenic has been employed as an indirect readout of VEGF signalling activity in zebrafish ECs39. To first establish whether fli1a:gal4FFubs3;uas-GCaMP7a embryos reliably reported fluctuations in endothelial Ca2+ signalling, we treated embryos with Thapsigargin to inhibit the sarcoplasmic or ER Ca-ATPase (SERCA) family of Ca2+ pumps40 and thereby raise endothelial Ca2+ levels. Indeed, Thapsigargin treatment significantly increased GCaMP7a fluorescence in tip cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b,d) and reduced cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations in tip cells (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Conversely, as VEGF-mediated elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ are dependent upon IP3R function37, we treated embryos with an IP3R antagonist 2-APB, to reduce cytosolic Ca2+ (Supplementary Fig. 4a,c). fli1a:GCaMP7a embryos treated with 2-APB displayed reduced EC GCaMP7a fluorescence and reduced frequency of Ca2+ oscillations in tip cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a,c,d,e).

Having established fli1a:gal4FFubs3;uas-GCaMP7a as a reporter of EC cytosolic Ca2+ levels in vivo, we examined the effect of tmem33 knockdown on EC Ca2+ oscillations. tmem33 knockdown in fli1a:gal4FFubs3;uas-GCaMP7a embryos significantly reduced the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations and GCaMP7a fluorescence intensity in EC tip cells (Fig. 2a–e and Supplementary Movies 4,5). Furthermore, treatment of fli1a:gal4FFubs3;uas-GCaMP7a embryos with the VEGFR inhibitor Tivozanib/AV951 reduced Ca2+ oscillations in a similar manner to tmem33 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d,i). In contrast, N-[N-(3,5-Difluorophenacetyl)-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT)-mediated inhibition of Notch signalling, which negatively regulates VEGF signalling41, significantly increased cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations within EC tip cells (Supplementary Fig. 5e,f,i). These data indicate tmem33 knockdown reduced endothelial Ca2+ activity to a similar level as VEGF inhibition and are consistent with studies that demonstrate EC calcium signalling mediates the response to VEGF in vivo39.

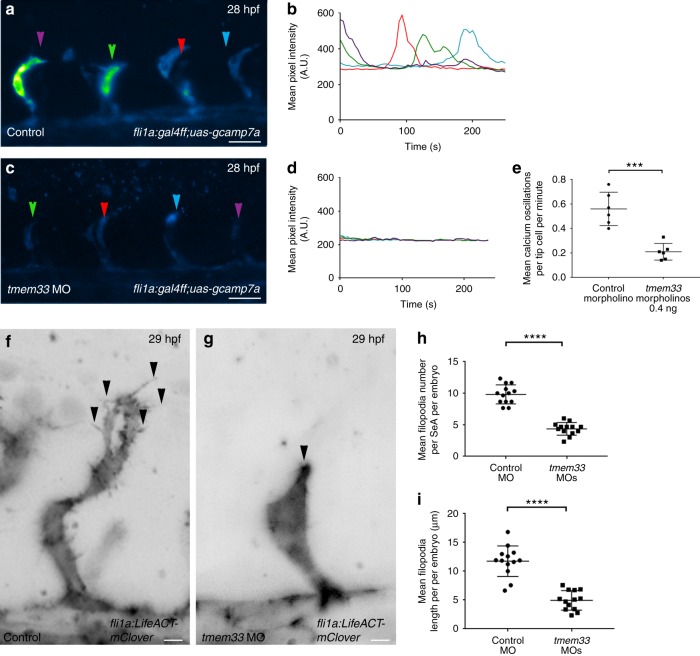

Fig. 2.

tmem33 knockdown reduces Ca2+ oscillations in tip cells and reduces EC filopodia. a–d tmem33 morphants injected with 0.4 ng morpholinos display reduced endothelial Ca2+ oscillations. Intensity projections show Ca2+ oscillations in both control and tmem33 morphants, highlighting intensity over duration of the time lapse. Change in fluorescence over 300 s for four SeAs, trace colours correspond to equivalent arrowheads (scale bars 50 µm). e tmem33 morphants display a significant reduction in Ca2+ oscillations when compared with control morphants (unpaired t-test ****p = < 0.001; t = 5.633; DF = 10, 2 repeats, n = 3 embryos per group). f, g tmem33 morphants injected with 0.4 ng morpholinos display delayed migration of SeAs, which extend fewer filopodia, compared with controls (black arrowheads) (scale bars 5 µm). h tmem33 morphants display significantly fewer filopodia per SeA compared with controls. Measurements taken from n = 4 SeAs per embryo. Unpaired t-test, ****p = < 0.0001; t = 7.805; DF = 24, 2 repeats, n = 6 or 7 embryos per group). i tmem33 morphants display reduced filopodia length compared with controls, measurements taken from n = 4 SeAs. Unpaired t-test ****p < 0.0001; t = 10.86; DF = 24; 2 repeats, n = 6 or 7 embryos per group. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

The delayed SeA sprouting, abnormal tip cell morphology and aberrant DLAV anastomosis following tmem33 knockdown (Fig. 1h–o) are similar to phenotypes observed following inhibition of filopodia formation in endothelial tip cells42. Knockdown of tmem33 in Tg(fli1a:lifeACT-mClover)sh467, which labels filamentous actin in ECs, substantially reduced the number and length of filopodia present on EC tip cells (Fig. 2f-i), suggesting defective filopodia formation may contribute to impaired angiogenesis in tmem33 morphants. As filopodia are known to express VEGF receptors and transduce the migratory signal upon VEGF ligand binding3,43, we examined whether loss of filopodia could account for the reduction in EC Ca2+ oscillations observed in tmem33 morphants (Fig. 2a–e, Supplementary Movies 4,5). Tg(fli1a:lifeACT-mClover) embryos treated with the actin depolymerising agent Latrunculin B did not form filopodia (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c, black arrowheads), instead forming rapidly depolymerising F-actin foci in keeping with previous reports42. Treatment of fli1a:gal4FFubs3;uas-GCaMP7a embryos with Latrunculin B had no significant effect on frequency of endothelial Ca2+ oscillations in tip cells in comparison with controls (Supplementary Fig. 6d–f, white arrowheads). This suggests loss of EC filopodia in tmem33 morphants is not responsible for reduced EC Ca2+ oscillations.

tmem33 mutant zebrafish embryos display genetic compensation

As morpholino knockdown is transient and may induce off-target effects, we next generated zebrafish tmem33 mutants using transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs)44. We identified a mutant allele (hereafter referred to as sh443) with a 2 bp deletion in exon 3, which induces a premature stop codon within exon 4 encoding the second conserved transmembrane helix (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). tmem33sh443 mutants display substantially reduced expression of tmem33 mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 7c–e) likely via nonsense-mediated decay, indicating this mutation represents a severe loss-of-function or null allele. However, in contrast to tmem33 morphants, vascular (Supplementary Fig. 7f,g) and pronephric development was normal in tmem33sh443 mutants and homozygous tmem33 mutant adults were viable. Recent studies describe mechanisms by which the zebrafish genome can compensate for genetic mutations but not morpholino knockdown45. Consistent with such compensation, homozygous tmem33sh443 mutants injected with tmem33 morpholinos titrated to a level, which did not significantly induce p53 expression (Supplementary Fig. 7h), displayed significantly longer SeAs compared with heterozygote or wild-type embryos (Supplementary Fig. 7i–l, arrowheads). In addition to the described effect on vascular and lymphatic development, tmem33 morphants exhibited increased glomerular size (Supplementary Fig. 7m–o, arrows) and homozygous tmem33sh443 mutants were protected against the effect of the tmem33 morpholino on glomerular size (Supplementary Fig. 7m–o, arrows). These data suggest tmem33sh443 mutants exhibit genetic compensation or transcriptional adaptation46.

tmem33 crispant embryos phenocopy tmem33 morphant embryos

As tmem33 mutants appeared to display genetic compensation, and in order to confirm the morpholino-induced phenotype, we next knocked down tmem33 using Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats interference (CRISPRi). This acts via steric inhibition of transcription47 and has been previously successful in zebrafish embryos45. In comparison with co-injection of mRNA encoding a catalytically inactive Cas9 nuclease (dCas9)47 and control single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) lacking the dCas9 binding motif (Supplementary Table 2), co-injection of sgRNAs flanking the start codon of tmem33 with dCas9 mRNA into zebrafish embryos (hereafter referred to as crispants) reduced tmem33 expression by in situ hybridisation (Supplementary Fig. 8a,b, arrowhead) and quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) (Supplementary Fig. 8c). tmem33 CRISPRi significantly reduced Ca2+ oscillations in tip cells (Supplementary Fig. 8d–h) and endothelial filopodia number and length (Supplementary Fig. 8i–l, arrowheads). We were able to rescue the angiogenic defects in tmem33 morphants and crispants by co-injection of full-length tmem33 mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 9) confirming that these were due to reduced expression of tmem33. Interestingly, at minimal phenotypic doses, induction of p53 expression was substantially reduced in tmem33 crispants in comparison with tmem33 morphants injected with 4 ng morpholino (Supplementary Fig. 8m), suggesting CRISPRi may be less subject to nonspecific effects than morpholinos. Taken together, these data demonstrate that transcriptional inhibition of tmem33 via CRISPRi induces endothelial defects highly similar to those generated by morpholino-mediated translational inhibition of tmem33 (Fig. 2). These data indicate tmem33 is required for endothelial cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations, endothelial filopodia formation and normal angiogenesis.

tmem33 promotes angiogenesis in an EC-specific manner

The morphant and crispant phenotypes described above were induced by global translational/transcriptional inhibition and tmem33 is expressed in tissue other than ECs and the developing kidney. We therefore sought to examine the effect of EC- and pronephros-specific inhibition of tmem33. As CRISPRi employs a genetically encoded catalytically inactive Cas9 nuclease (dCas9)47, we postulated that co-expressing dCas9 under the control of a tissue-specific promoter and gene targeting sgRNAs may facilitate tissue-specific knockdown of tmem33. We therefore generated fli1a:dCas9, cryaa:cfp and enpep:dCas9, cryaa:cfp constructs (Supplementary Fig. 10a,b) that drive transient dCas9 expression under control of either EC or pronephros-specific promoters, respectively. These constructs were injected alongside Tol2 mRNA and gene-targeting sgRNAs to elicit tissue-specific gene knockdown.

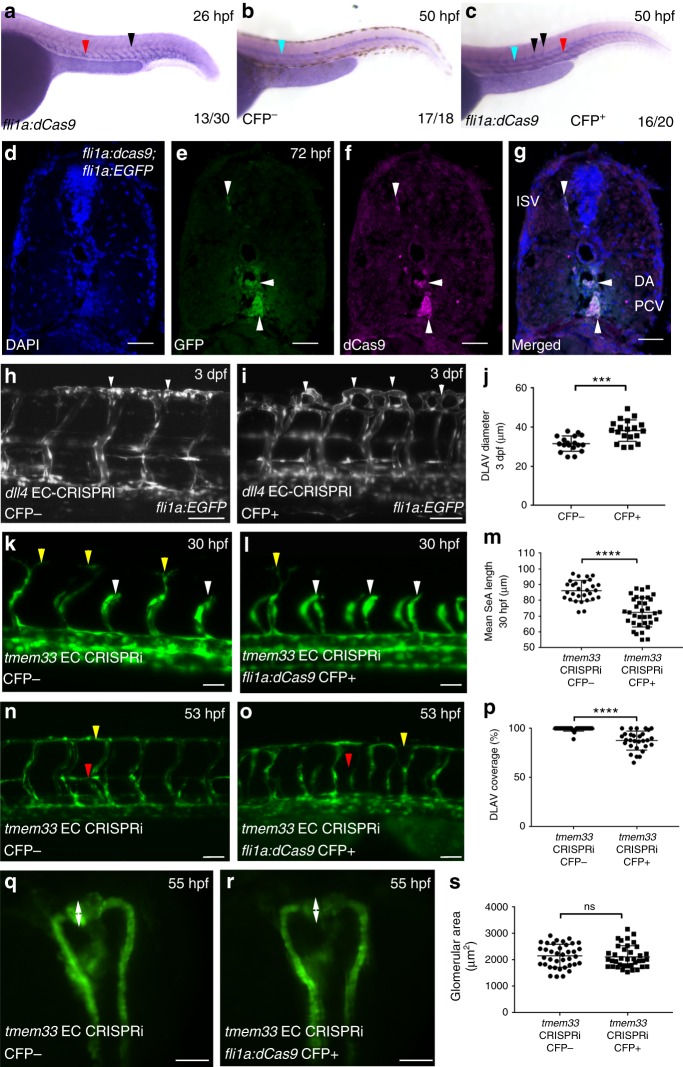

In comparison with co-injection of dCas9 mRNA and control sgRNAs lacking the dCas9-binding motif (Supplementary Fig. 10c, arrowheads, g arrows, k, l), co-injection of sgRNAs targeting tmem33 and dCas9 mRNA into progeny of an intercross between Tg(fli1a:AC-TagRFP)sh511/+ and Tg(wt1b:egfp)/ + fish induced both abnormal vascular and pronephric development (Supplementary Fig. 10d, arrowheads h, arrows k, l,) as previously demonstrated. In contrast, embryos injected with tmem33 sgRNAs and fli1a:dCas9, cryaa:cfp construct displayed significantly reduced DLAV continuity but normal kidney development (Supplementary Fig. 10e, arrowheads i, arrows k, l), whereas embryos injected with tmem33 sgRNAs and enpep:dCas9, cryaa:cfp construct, restricting CRISPRi knockdown to the kidney, developed distended glomeruli, whereas the vasculature was normal (Supplementary Fig. 10f, arrowheads j, arrows k, l). We next generated a stable transgenic line expressing dCas9 in EC Tg(fli1a:dCas9, cryaa-cerulean)sh512, hereafter referred to as Tg(fli1a:dCas9). To avoid the potential for reduced of knockdown efficiency by fluorescent tagging, we employed untagged dCas945. We screened for embryos expressing dCas9 in ECs by in situ hybridisation (Fig. 3a–c) and validated EC-restricted expression of dCas9 using immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3d–g). As co-injection of dCas9 mRNA and control sgRNAs were consistent with normal vascular and pronephric development (Supplementary Fig. 8, S10), to test efficacy of EC gene knockdown in stable dCas9 expressing transgenics, we first injected progeny of outcrosses from Tg(fli1a:dCas9)/+ × Tg(fli1a:EGFP)/+ with an sgRNA targeting dll4 (Fig. 3h–j). Injection of sgRNA therefore served as an internal control in Cerulean Fluorescent Protein (CFP)-negative embryos. CFP-positive embryos displayed significantly increased DLAV diameter in comparison with CFP-negative embryos (Fig. 3h,i, arrowheads, j), consistent with previously observed ectopic DLAV sprouting in dll4 morphants and mutants48. Injection of tmem33 sgRNAs into Tg(fli1a:dCas9) embryos delayed SeA sprouting (Fig. 3k–m, compare white arrowheads with yellow arrowheads) and induced discontinuous DLAV formation (Fig. 3n–p, yellow arrowheads) only in CFP-positive embryos, similar to tmem33 morphants (Fig. 1h–o) and crispants (Supplementary Fig. 10d,e, arrowheads, k). Furthermore, Tg(fli1a:dCas9) embryos injected with tmem33 sgRNA displayed absent parachordal lymphangioblasts (Fig. 3n, o, red arrowheads) only in CFP-positive embryos, similar to tmem33 morphants (Fig. 1l–o, red arrowheads). By contrast, Tg(fli1a:dCas9) embryos injected with tmem33 sgRNA displayed no significant difference in glomerular area between CFP-positive and -negative embryos (Fig. 3q–s, arrows). Collectively, these data demonstrate tissue-specific CRISPRi-mediated uncoupling of tmem33 functions within the endothelium and pronephros, and indicate EC-specific and pronephros-specific functions of tmem33 during angiogenesis and pronephric development, respectively, in zebrafish. Importantly, all approaches to knockdown tmem33 function were compatible with normal gross embryonic morphology at phenotypic doses (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Fig. 3.

Injection of sgRNAs targeting tmem33 into stable Tg(fli1a:dCas9;cryaa:CFP)sh512 embryos recapitulates knockdown of tmem33. a dCas9 is expressed within the developing vasculature (red arrowhead) including SeAs (black arrowheads) in ~50% of progeny from a Tg(fli1a:dCas9;cryaa:Cerulean)sh512/ + outcross at 26 hpf. At this stage the dominant cryaa:Cerulean marker is not expressed. b dCas9 is not expressed within the developing vasculature in CFP- Tg(fli1a:dCas9;cryaa:Cerulean)sh512 transgenic embryos at 50 hpf. Probe trapping in notochord is highlighted (blue arrowhead). c dCas9 is expressed within the dorsal aorta (red arrowhead) and SeAs (black arrowheads) in CFP+ Tg(fli1a:dCas9;cryaa:Cerulean)sh512 transgenic embryos at 50 hpf. Probe trapping in notochord is highlighted (blue arrowhead). d–g Colocalisation of dCas9 and GFP in 72 hpf fli1a:dCas9; fli1a:EGFP embryo indicates EC restricted expression of dCas9 (white arrowheads) Scale bars 20 μm. h, i Tg(fli1a:dCas9;cryaa:Cerulean) embryos injected with sgRNA targeting dll4 phenocopies ectopic vascular looping within the DLAV previously observed in dll4 morphants and mutants at 3 dpf (white arrowheads). j Tg(fli1a:dCas9;cryaa:Cerulean)-positive embryos injected with sgRNAs targeting dll4 display increased DLAV diameter (unpaired t-test ***p = < 0.001; t = 4.203 DF = 35; 2 repeats; n = 9 embryos per group). Scale bars 50 µm. k-m Tg(fli1a:dCas9;cryaa:Cerulean) embryos injected with sgRNAs targeting tmem33 display reduced SeA length (yellow arrowheads highlight normal SeAs, white arrowheads highlight delayed SeAs) at 30 hpf (unpaired t-test ***p = < 0.0001; t = 6.716 DF = 62; 3 repeats; n = 9–12 embryos per group). Scale bars 50 µm. n–p Tg(fli1a:dCas9;cryaa:Cerulean) embryos injected with sgRNAs targeting tmem33 display absent parachordal lymphangioblasts (red arrowhead) and reduced DLAV continuity (yellow arrowheads) (unpaired t-test ***p = < 0.0001; t = 6.399 DF = 56; 3 repeats; n = 9–11 embryos per group). Scale bars 50 µm. q–s Tg(fli1a:dCas9;cryaa:Cerulean) embryos injected with sgRNAs targeting tmem33 display no significant difference in glomerular area, compared with Tg(fli1a:dCas9;cryaa:Cerulean)-negative siblings embryos (unpaired t-test, ns = not significant; t = 0.4048; DF = 74; 3 repeats; n = 12–13 embryos per group). Scale bars 200 µm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

tmem33 functions downstream of VEGF during angiogenesis

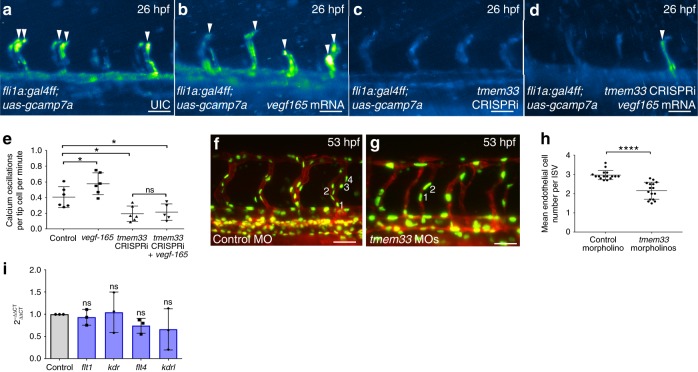

Elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ are induced when EC tip cells respond to extracellular Vegfa via the Kdrl receptor39 and EC Ca2+ oscillations are reduced in tip cells following tmem33 knockdown (Fig. 2a–e, Supplementary Movies 4, 5 and Supplementary Fig. 8d-h). We therefore sought to establish epistasis between VEGF signalling and tmem33. We overexpressed vegfa165 mRNA, which increases EC Ca2+ signalling (Supplementary Fig. 5g, h, j) and examined the effect on EC Ca2+ activity in the presence or absence of tmem33 CRISPRi knockdown (Fig. 4a–e and Supplementary Movies 6–9). As expected, vegfa165 overexpression increased the frequency of cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations in endothelial tip cells (Fig. 4a, b, arrowheads, e) but this was significantly reduced by simultaneous tmem33 knockdown by CRISPRi (Fig. 4d,e) similar to knockdown of tmem33 alone without vegfa165 overexpression (Fig. 4c-e). Thus, tmem33 is required for Vegfa-induced Ca2+ oscillations in endothelial tip cells.

Fig. 4.

tmem33 functions downstream of Vegfa during angiogenesis. a–e tmem33 knockdown prevents Vegfa-mediated increases in Ca2+ oscillations. Overexpression of vegfa165 significantly increases frequency of Ca2+ oscillations in SeAs, whereas tmem33 knockdown alone and in the presence of vegfa165 significantly reduce frequency of Ca2+ oscillations in SeAs. Intensity projection over time showing Ca2+ oscillations highlighting intensity change over duration of time lapse. Embryos display changes in fluorescence in SeA tip cells (white arrowheads) (two-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s corrections: *p = < 0.05. 2 Repeats, n = 3 embryos per group) (scale bars 50 µm). f–h tmem33 knockdown using 0.4 ng morpholinos reduces EC number in ISVs at 53 hpf. h Unpaired t-test; ****p < 0.0001; t = 6.507; df = 30; 2 repeats; n = 8 embryos per group. i VEGF receptor expression is not significantly affected in tmem33 crispants (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s corrections; p = < 0.05, n = 3 repeats). Source data are provided as a Source Data file

In addition, Vegfa promotes proliferation of intersegmental vessel (ISV) ECs via a process normally limited by Notch signalling4. We therefore asked whether tmem33 knockdown suppresses EC number in ISVs. Vessels are referred to as ISVs where the transgene employed did not allow distinction between SeAs and SeVs. Knockdown of tmem33 reduced EC number within ISVs (Fig. 4f-h), similar to previous studies following VEGF inhibition5. Furthermore, VEGF receptor expression was unaffected in tmem33 crispants (Fig. 4i). Taken together, these data demonstrate that tmem33 mediates the effects of VEGF during angiogenesis and is required for VEGF-mediated cytosolic Ca2+ signalling within endothelial tip cells. Furthermore, these data suggest tmem33 knockdown inhibits EC proliferation in response to VEGF.

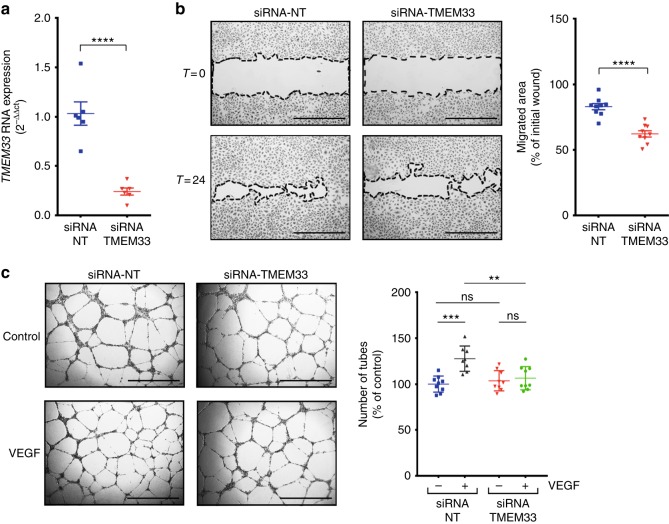

TMEM33 is required for VEGFA-mediated angiogenesis in HUVECs

As tmem33 mediates the effects of Vegfa in zebrafish, we next sought to establish whether this was conserved in humans. We used RNA interference to knock down TMEM33 in human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) (Fig. 5a) and examined the effect on EC migration and tube formation in response to VEGFA (Fig. 5b). Consistent with our findings in zebrafish, TMEM33-deficient HUVECs migrated less than controls (Fig. 5b). In addition, HUVEC tubular morphogenesis induced by VEGFA was significantly reduced by TMEM33 knockdown (Fig. 5c), indicating the requirement for TMEM33 during the response to VEGFA is conserved in humans.

Fig. 5.

TMEM33 is required for VEGFA-mediated angiogenesis in HUVECs. a TMEM33 expression is significantly reduced by small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown. b Representative images of wound-healing migration assays performed with HUVECs transfected with a non-targeting control siRNA (siRNA-NT) or a siRNA specific for human TMEM33 (siRNA-TMEM33) after incubation in culture medium supplemented with VEGF (25 ng/ml). Data are shown as mean ± SE, n = 9, obtained from three independent experiments for comparison of cells transfected with siRNA-TMEM33 vs. siRNA-NT (unpaired two-tailed, Student’s t-test ****p ≤ 0.001). Images were taken at time zero and after incubation for 24 h. The migrated area was calculated by subtracting the value of the non-migrated area from the wound area at time zero and expressing this as a percentage of the total area at time zero. Scale bars, 1000 µm. c HUVECs transfected as described in a were plated on Growth-Factor Reduced Matrix (Geltrex) in Medium 200 containing 2% FBS (Control), supplemented with VEGF (25 ng/ml) when indicated (VEGF). Images show representative fields from experiments quantified in the histogram. Data are shown as mean ± SE, n = 8, obtained from three independent experiments; ns = nonsignificant; **p ≤ 0.01; ***one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s comparison test p ≤ 0.005. Scale bars, 1000 µm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

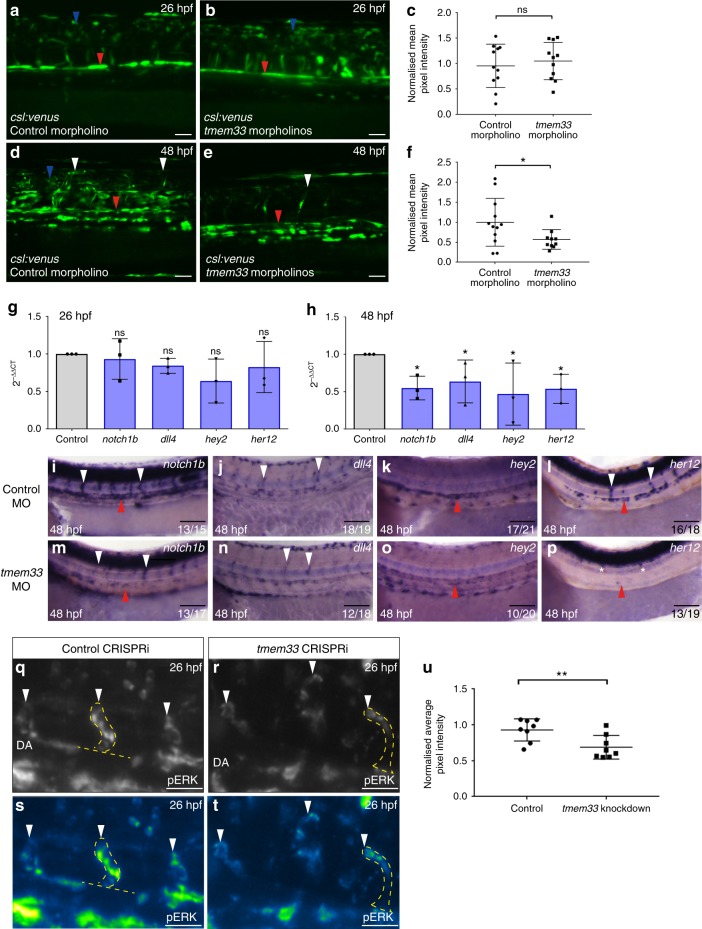

tmem33 knockdown reduces EC Notch and ERK signalling

VEGF signalling via VEGF receptor 2 (kdr), and VEGFR4 (kdrl) in zebrafish, induces transcription of dll4 in endothelial tip cells via the MEK-ERK signalling pathway. Upregulation of Dll4 in endothelial tip cells induces Notch signalling in neighbouring stalk cells, which balance tip and stalk cell identity via regulation of VEGFR expression7,41. As tmem33 mediates the response to VEGF, we examined whether Dll4/Notch signalling was perturbed by tmem33 knockdown. Using a transgenic Notch reporter Tg(csl:venus)49, which reliably reports endothelial Notch signalling (Supplementary Fig. 12a–f), we observed no significant differences in reporter expression at 26 hpf (Fig. 6a, b red arrowhead, c), but by 48 hpf, Notch reporter expression was significantly reduced in the DA (Fig. 6d, e, red arrowheads, f) and SeAs displayed reduced Venus fluorescence in tmem33 morphants (Fig. 6d, e, white arrowheads). In keeping with this, expression of dll4, notch1b and the Notch targets hey2/gridlock and her12 were reduced by tmem33 knockdown using global CRISPRi at 48 hpf but not 26 hpf (Fig. 6g, h and Supplementary Table 3). In situ hybridisation confirmed reduced arterial expression of all genes assayed by qPCR at 48 hpf (Fig. 6i–p, arrowheads). Phosphorylation of the serine/threonine kinase ERK preferentially occurs in angiogenic ECs7. In keeping with this requirement downstream of VEGF signalling during angiogenesis, tmem33 knockdown reduced phosphorylated ERK (pERK) in sprouting SeAs (Fig. 6q–t, white arrowheads, u). pERK promotes expression of dll4 in zebrafish angiogenic ECs7,10 and dll4 expression was reduced by tmem33 knockdown (Figs. 6h, n, arrowheads). These data indicate tmem33 is required for ERK phosphorylation and Notch signalling, which act downstream of VEGF in angiogenic ECs.

Fig. 6.

tmem33 knockdown reduces endothelial Notch and ERK signalling during angiogenesis. a–c Notch reporter expression is unaffected by injection of 0.4 ng tmem33 morpholinos at 26 hpf. Notch signalling activity in control embryos is present in neural tube (blue arrowhead) and DA (red arrowhead) (c, unpaired t-test; t = 0.5553; DF = 20; 2 repeats; n = 5 or 6 embryos per group). Scale bars 50 µm. d–f Injection of 0.4 ng tmem33 morpholinos reduces Notch reporter expression at 48 hpf. Notch expression in control Tg(csl:venus) embryos is present in the neural tube (blue arrowhead), DA (red arrowhead) and SeAs (white arrowheads) (f, unpaired t-test; p = 0.0451; t = 2.138; DF = 20; 2 repeats; n = 6 and 4 embryos per group). Scale bars 50 µm. g Expression of notch1b, dll4, hey2 and her12 are not significantly altered by tmem33 CRISPRi at 26 hpf (one-way ANOVA using post hoc Tukey’s comparison test. n = 3 repeats). h Expression of notch1b, dll4, hey2 and her12 are significantly reduced at 48 hpf by tmem33 CRISPRi (one-way ANOVA using post hoc Tukey’s comparison test. *p = < 0.05; **p = < 0.01. n = 3 repeats). i–p In comparison with control morphants (i–l), embryos injected with 0.4 ng tmem33 morpholino (m–p) display reduced expression of notch1b within the DA (i, m, red arrowheads) and SeAs (i, m, white arrowheads), dll4 within SeAs (j, n, white arrowheads), hey2 within the DA (k, o, red arrowheads) and her12 within the DA (l, p, red arrowheads) and SeAs (l, p, white arrowheads). Scale bars 100 µm. q–t tmem33 knockdown by CRISPRi reduces endothelial ERK phosphorylation (q, r, SeAs highlighted by yellow outline and white arrowheads). Intensity plot of ERK staining is shown (s, t, SeAs highlighted by yellow outline and white arrowheads). Scale bars 50 µm. u tmem33 crispants display significantly reduced levels of pERK phosphorylation. Pixel intensity normalised to neural tube ERK fluorescence (unpaired t-test, **p = 0.0097, t = 2.993 DF = 14. n = 2 repeats, 4 embryos per group). Source data are provided as a Source Data file

As tmem33 promotes sprouting angiogenesis cell autonomously (Fig. 3), we examined whether several other molecular and cellular consequences of tmem33 inhibition were due to tmem33 function within ECs. Similar to knockdown of tmem33 by morpholino and CRISPRi, Tg(fli1a:dCas9) embryos injected with tmem33 sgRNA displayed reduced endothelial Ca2+ oscillations (Supplementary Fig. 13a–c, white arrowheads), reduced filopodia number and length (Supplementary Fig. 13d–g, black arrowheads), reduced EC number in ISVs (Supplementary Fig. 13h–j) and reduced endothelial Notch signalling (Supplementary Fig. 13k–m, arrowheads) in CFP-positive embryos in comparison with CFP-negative siblings. Collectively, this indicates tmem33 is required cell autonomously to promote endothelial Ca2+ oscillations, filopodia formation, Notch signalling and to regulate EC number during angiogenesis.

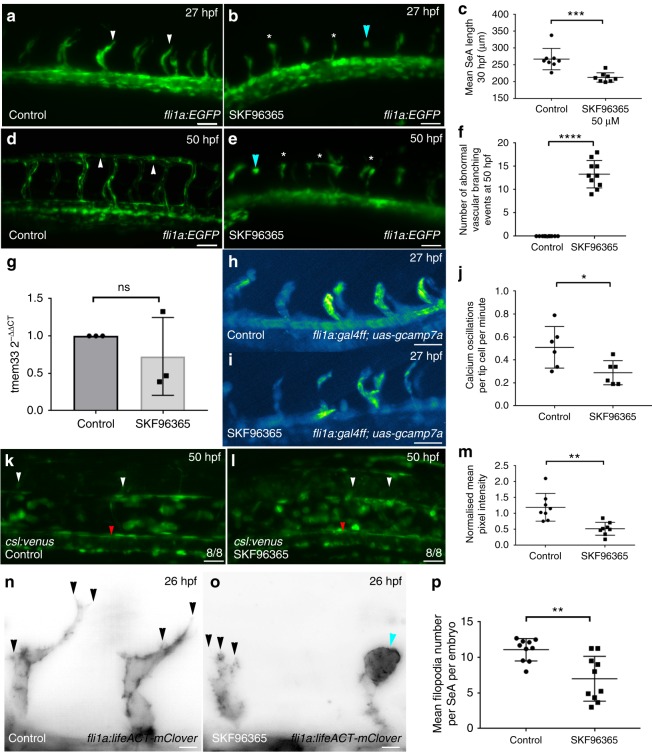

SOCE inhibition inhibits angiogenesis

Although tmem33 knockdown impairs angiogenesis and reduces endothelial cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations, it was possible that these effects were due to different roles of tmem33 rather than causally linked. We therefore sought to determine whether inhibiting EC cytosolic Ca2+ release was sufficient to cause the observed phenotype of tmem33 knockdown. We inhibited SOCE using SKF-96365, a compound that inhibits STIM1 and TRPC1 function7,50. SKF-96365 treatment between 21 hpf and 27 hpf reduced SeA length (Fig. 7a–c arrowheads) as induced by tmem33 knockdown (Fig. 1j, k white arrowheads). Embryos treated from 21 hpf until 50 hpf displayed incomplete DLAV formation (Fig. 7d–f, arrowheads) similar to tmem33 knockdown (Fig. 1n, o). Importantly, although tmem33 expression was unaffected by SKF-96365 treatment (Fig. 7g), frequency of endothelial Ca2+ oscillations was significantly reduced in tip cells (Fig. 7h–j). Furthermore, Notch reporter expression (Fig. 7k–m) and endothelial tip cell filopodia number (Fig. 7n–p) was reduced in ECs following SKF-96365 treatment similar to tmem33 knockdown (Fig. 6d–f and Fig. 2f-i, respectively). SKF-96365-treated embryos also displayed abnormal spade-shaped tip cell morphology (Fig. 7b, e, o, blue arrowheads) as induced by tmem33 knockdown (Fig. 1k, white arrowhead). Given the similar angiogenic defects induced by tmem33 knockdown and SKF-96365 treatment, we examined whether inhibition of SOCE could account for reduced EC number and migration previously observed in tmem33 morphants (Fig. 4f–h, and Supplementary Fig. 2). We treated embryos from 21 hpf until 30 hpf and quantified EC proliferation and migration in the presence and absence of SKF-96365 between 24 and 30 hpf (Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Movies 10, 11), and observed that both SeA migration (Supplementary Fig. 14a–e, arrowheads) and tip and stalk cell proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 14a–d,f–h) were significantly reduced in migrating SeAs treated with SKF-96365. Consistent with this, expression of VEGF receptors in tmem33 crispants were unaffected (Fig. 4i) and thus unlikely to account for reduced EC number (Fig. 4f–h and Supplementary Fig. 13h–j). Collectively, these data demonstrate that SOCE inhibition impairs angiogenesis in vivo by limiting EC migration, proliferation, disrupting signalling pathways downstream of VEGF and inhibiting filopodia formation similar to tmem33 knockdown. This is consistent with our hypothesis that reduced cytosolic EC Ca2+ oscillations account for the angiogenic defects observed caused by tmem33 knockdown. Thus, tmem33 is essential for VEGF-mediated endothelial Ca2+ oscillations that are required for tip cell filopodia formation, the downstream consequences of VEGF signalling and developmental angiogenesis (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

SOCE inhibition limits sprouting angiogenesis and disrupts signalling pathways downstream of VEGF. a, b SKF9635 impairs angiogenesis in Tg(fli1a:EGFP) embryos (white arrowheads) and induces abnormal tip cell morphology (blue arrowhead) by 27 hpf. Scale bars 50 µm. c SKF-96365-treated embryos display reduced SeA length by 27 hpf (unpaired t-test; p = < 0.0001; t = 11.22 DF = 14; 2 repeats, n = 4 embryos per group). d, e SKF-96365 treatment impairs DLAV formation (white asterisks) in comparison with control embryos, which form the DLAV normally by 50 hpf (white arrowheads). Abnormal tip cell morphology (blue arrowhead) remain in SKF-96365-treated embryos by 50 hpf. Scale bars 50 µm. f SKF-96365-treated embryos display increased frequency of abnormal vascular branching (stunted SeAs or incomplete DLAV anastomosis) by 50 hpf (unpaired t-test; p = < 0.0001; t = 14.28 DF = 18. n = 2 repeats, n = 5 embryos per group). g tmem33 expression is not significantly altered by SKF-96365 treatment (unpaired t-test; t = 0.911, DF = 4, n = 3 repeats). h–j SKF-96365 reduces frequency of endothelial Ca2+ oscillations in Tg(fli1a:gal4FFubs3;uas-gcamp7a) embryos. Intensity projection over time showing calcium oscillations in control embryos, highlighting intensity change over duration of time lapse (unpaired t-test; p = < 0.05; t = 2.594, DF = 10, n = 2 repeats, 3 embryos per group). k, l Notch reporter expression is reduced in SeAs (white arrowheads) and DA (red arrowhead) of Tg(csl:venus) embryos. Scale bars 50 µm. m DA expression of Notch reporter is reduced by SKF treatment (unpaired t-test, **p = 0.0097, t = 3.982 DF = 15, 2 repeats, n = 4 embryos per group). n, o SKF-96365 treatment reduces endothelial filopodia number (black arrowheads) and abnormal spade-shaped tip cell morphology (blue arrowhead), in Tg(fli1a:lifeact-mClover) embryos. Scale bars 5 µm. p SKF-96365 treatment reduces mean filopodia number per SeA per embryo by 26 hpf (unpaired t-test; p = < 0.05; t = 2.525, DF = 10, n = 2 repeats, n = 5 embryos per group). Source data are provided as a Source Data file

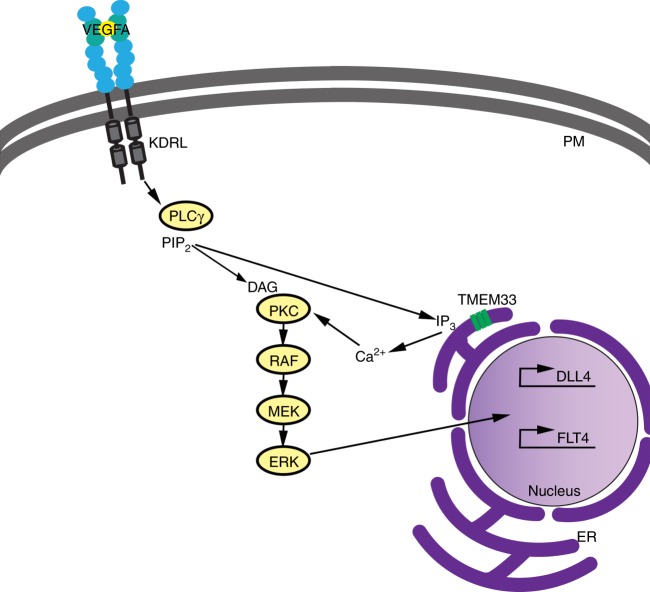

Fig. 8.

Proposed model for tmem33 function in endothelial cells during angiogenesis. When VEGFA binds to its cognate receptor, e.g., Kdrl, the resulting phosphorylation of PLCγ generates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and this, in turn, binds to IP3 receptors on the ER membrane, which release Ca2+ into the cytosol from intracellular stores. Our data suggest the VEGF-mediated release of Ca2+ from ER stores during angiogenesis is dependent on Tmem33 function within the ER membrane. Furthermore, resultant Ca2+ oscillations generated in tip cells downstream of Vegfa contribute to phosphorylation of ERK and induction or maintenance of downstream targets including Dll4/Notch signalling, to co-ordinate cellular behaviours during vascular morphogenesis. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; P, plasma membrane

Discussion

No previous study has examined the function of tmem33 in a multicellular organism. Previous studies in yeast20–22 and transformed human cells23,24 had localised tmem33 to the ER, but no function has been demonstrated during development. We find tmem33 is expressed widely throughout the developing zebrafish embryo and localised to structures indicative of ER in zebrafish ECs. In keeping with its expression patterns, tmem33 knockdown demonstrated a requirement for tmem33 during normal angiogenesis and pronephric development. Furthermore, TMEM33 is also required for VEGFA-mediated angiogenesis in human ECs, indicating a conserved function between zebrafish and human.

We find that tmem33 is required for Vegfa-mediated cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations in endothelial tip cells. Although increases in cytosolic Ca2+ are a well-established response to VEGF in ECs37, it remained unclear whether Ca2+ signalling was required for its effects in vivo and, if so, how Ca2+ co-ordinated EC behaviours during angiogenesis. Recent studies have established that Vegfa/Kdrl signalling is required for endothelial Ca2+ oscillations during sprouting angiogenesis in vivo39. Our findings are consistent with these, as VEGFR inhibition abrogated Ca2+ oscillations and overexpression of vegfa165 mRNA or Notch inhibition increased Ca2+ oscillations in tip cells. Reduction of Ca2+ oscillations in tip cells following either tmem33 knockdown or acute SOCE inhibition were associated with reduced formation of filopodia, abnormal tip cell migration and aberrant anastomosis. Impaired SeA migration and DLAV anastomosis have been observed in embryos with reduced EC filopodia formation, suggesting this may contribute to the angiogenic defects induced by tmem33 knockdown42. Importantly, the frequency of cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations in tip cells was unaffected following loss of filopodia. This is in keeping with studies that demonstrated tip cells without filopodia retained their ability to respond to Vegfa42 and suggests reduced filopodia formation induced by tmem33 knockdown was secondary to reduced EC Ca2+ oscillations. Ca2+ oscillations have been reported to promote F-actin reorganisation and cell migration in vitro51,52. It therefore seems likely to be that tmem33-mediated cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations induced by VEGF signalling promote tip cell migration in vivo via organisation of the actin cytoskeleton. As such, tmem33-mediated Ca2+ oscillations permit tip cells to respond quickly to the proangiogenic Vegfa stimulus.

Vegfa-mediated activation of ERK signalling is also required for angiogenic sprouting and induction of tip cell marker expression including dll4 7,10,33,53. tmem33 knockdown reduced ERK phosphorylation and Dll4/Notch signalling, and delayed tip cell migration in a similar way to ERK inhibition7,53 without significantly affecting vegfr expression. This indicates tmem33 function contributes to activation of these pathways in vivo, likely to be via Ca2+-dependent mechanisms downstream of Vegfa. Interestingly, induction of Dll4/Notch signalling at 26 hpf was not dependent on tmem33 function; however, its attenuation at 48 hpf, suggests tmem33 contributes to maintenance of Dll4/Notch signalling in ECs. Consistent with this, inhibition of SOCE reduced Notch reporter activity at 48 hpf, suggesting an input from VEGF-mediated calcium signalling between 1 and 2 dpf to maintain Dll4/Notch signalling within developing arteries. Furthermore, recent studies indicate a requirement for Ca2+ binding during folding of Notch receptors and ligand engagement, including the Dll4–Notch1 interaction54. Reduced expression of dll4 induced by tmem33 knockdown is in keeping with observed reductions in ERK phosphorylation. ERK phosphorylation is required for development of the lymphatic system33-35,55; therefore, reduced ERK phosphorylation induced by tmem33 knockdown may contribute to defective lymphatic sprouting.

Surprisingly, tmem33 mutants exhibited normal angiogenesis, yet displayed substantial reductions in tmem33 expression. The relative ease with which one can now generate targeted lesions within the zebrafish genome and widespread adoption of these approaches by the community has generated substantial evidence that many loss-of-function mutants fail to recapitulate morpholino-induced phenotypes56. Although this was initially attributed to well-established off-target effects of morpholinos57, recent studies have indicated a greater degree of compensation within the zebrafish genome than previously considered45. The tmem33sh443 allele is predicted to generate a premature stop codon within coding exon 4, located 53 nucleotides downstream of an exon junction. This is consistent with the requirement for induction of nonsense-mediated decay58 and observed reductions in tmem33 expression. It is therefore likely that this allele represents a severe loss of function or null mutation, and that compensatory machinery exists within the zebrafish genome to account for normal angiogenesis in tmem33sh443 mutant embryos.

To circumvent these compensatory pathways, we have developed a strategy to transiently knock down gene function within zebrafish endothelium and pronephros using tissue-specific CRISPRi. Using this approach we were able to uncouple tissue-specific functions of tmem33 and show that tmem33 is required cell autonomously in both tissues for their normal development. tmem33 functions within ECs to promote endothelial Ca2+ oscillations and filopodia formation during angiogenesis, and also to promote Notch signalling and regulate EC number. Tissue-specific CRISPRi offers a relatively straightforward method to study gene function within different tissues and represents an alternative to laborious cell transplantation procedures. Tissue-specific CRISPRi can be employed transiently to uncouple tissue-specific functions of genes, via co-injection of gene-targeting sgRNAs, dCas9 expression constructs and Tol2 mRNA. However, we observed more severe defects using this approach than when using stable transgenic lines expressing dCas9. We suspect this may be due to variable copy number integration mediated by Tol2 and thus variable dCas9 expression, in addition to inherent toxicity of DNA microinjections. At minimal phenotypic doses, CRISPRi is less prone to induction of p53 than some morpholinos and although this will vary depending upon the sgRNA, target and morpholino employed, our experience with the genes we have studied to date suggests CRISPRi may be susceptible to fewer off-target effects.

The localisation of tmem33 within the ER in zebrafish ECs suggest it may have an important function in regulation of endothelial SOCE. Consistent with this, acute antagonism of SOCE induced similar reductions in cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations, filopodia formation and endothelial Notch activity as tmem33 knockdown, without affecting tmem33 expression. Furthermore, SOCE inhibition reduced EC proliferation, consistent with reduced EC number induced by tmem33 knockdown. Genome-wide protein interaction studies in Drosophila embryos, have shown that the Drosophila Tmem33 orthologue, Kr-h2, physically interacts with SERCA59, and although this requires functional validation, the interaction appears to be conserved in humans. This suggests an ancestral function of Tmem33 in regulation of SOCE. Tmem33 may also act to augment the activity of Ca2+ channels such as IP3R within the ER. Alternatively, tmem33 may be involved in mediating cortical distribution of the ER, as has been described for a yeast orthologue Tts1p22. Interestingly, rapid changes in cytosolic Ca2+ are known to induce dynamic changes in actin cytoskeleton organisation in vitro60. The actin cytoskeleton has been linked to normal SOCE function by facilitating interaction of ER-resident proteins with their plasma membrane counterparts19,61. As tmem33 knockdown reduces Ca2+ oscillations and inhibits filopodia formation, this represents an intriguing possibility. VEGF has been shown to induce distinct modalities of calcium oscillations that correlate with different EC behaviours, including migration and proliferation62. We find that inhibition of SOCE impairs both migration and proliferation of ECs and knockdown of tmem33 similarly impairs EC migration and reduces EC number, suggesting an essential requirement for Ca2+oscillations in both processes. The endothelial actin cytoskeleton is necessary for efficient mitosis and migration, and is notably disrupted by tmem33 knockdown or SOCE inhibition. This suggests that reduced EC proliferation and migration induced by inhibition of SOCE or reduced migration and EC number induced by tmem33 knockdown may represent a consequence of Ca2+-dependent disruption of the endothelial actin cytoskeleton. Further studies will be required to address the precise function of Tmem33-mediated Ca2+ within the ER in ECs in response to VEGF.

Methods

Zebrafish strains, morpholinos and sgRNA

All zebrafish were maintained according to institutional and national ethical and animal welfare guidelines. All experiments were performed under UK Home Office licences 40/3708 and 70/8588. The following published zebrafish lines were employed: Tg(fli1a:EGFP)y1 63 Tg(−0.8flt1:enhRFP)hu5333 25, Tg(−26wt1b:EGFP)li1 64, Tg(flk1:EGFP-NLS)zf109 65, Tg(kdrl:HRAS-mCherry-CAAX)s916 66 and Tg(csl:venus)qmc6149. For details on mutant and transgenic line generation, see Supplementary Methods. A quantity of 0.2 or 2 ng of Sp2b and Sp3 morpholinos were injected. Where these were co-injected, a total of 0.4 ng or 4 ng was injected. Four nanograms of morpholino was found to exhibit some induction of p53 (Supplementary Fig. 7h) and was titrated to 0.4 ng to reduce this; however, phenotypes were equivalent at each dose. One nanogram of each sgRNA was injected alongside 500 pg of dCas9 mRNA45. Negative control sgRNAs contained the DNA-binding element of the active gRNA but lacked the stem-loop forming region associated with binding to the Cas9 or dCas9 protein. For morpholino, sgRNA and primer sequences, see Supplementary Methods.

Generation of tmem33sh443 mutant allele

TALENs specific for tmem33 (ENSDARG00000041332) were designed against the following sequence 5′-cttcctggcccaggctt-3′ targeting an EcoNI site within exon 3. TALENs were assembled using the Golden Gate TALEN and TAL Effector Kit (Addgene, MA, USA)44 to generate the pTmem33Tal1L&R plasmids. Following linearisation of pTmem33Tal1L&R with NotI, capped mRNA was generated by in vitro transcription and 1500 pg TALEN mRNA was injected per embryo. Individual G0 embryos were tested by PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism using tmem33ex3F and tmem33ex3R primers (Table S1), to identify somatic mutations that destroyed the EcoNI restriction site. The progeny of TALEN-injected G0 adults were incrossed and genotyped to confirm the presence of the sh443 allele. All studies were performed using F3 and F4 generations.

Generation of fli1a:dCas9 and enpep:dCas9 constructs

pME-dCas9 was generated by cloning the nls-dCas9-nls coding sequence from pT3TS-dCas9, a kind gift of Didier Stainier, into pME-MCS2, which contained the multiple cloning site of pCS2+. fli1a:dCas9;cryaa:cfp and enpep:dCas9;cryaa:cfp constructs (Supplementary Fig. 10a) were subsequently generated using the Tol2 Kit via standard methods67. Each construct was injected into Nacre embryos alongside Tol2 mRNA at 25 pg/nl.

Generation of transgenic lines

Tg(fli1a:Gal4FFubs3;UAS-GCaMP7a)sh392 was generated via injection of pTol2UASGCaMP7a into progeny of tg(fli1a:Gal4FF)ubs3 68 heterozygous outcross alongside tol2 mRNA according to standard protocols67. Tg(fli1a:LifeAct-mClover)sh467 was generated by fusing the LifeAct F-Actin binding motif69 to the N terminus of mClover by PCR (Table S1) to generate pME-LifeAct-mClover. fli1a:LifeAct-mClover construct was generated using the tol2 Kit via standard methods67 and the following components: fli1a enhancer/promoter70, pME-LifeAct-mClover, pDestTol2-pA267, and p3E-SV40pA67. Tg(fli1a:DsRedEx2)sh495 was generated using the tol2 Kit via standard methods67 and the following components: fli1a enhancer/promoter70, pENTRDSRedEx270, pDestTol2-pA267, and p3E-SV40pA67. Tg(fli1a:AC-TagRFP)sh511 was generated by amplifying the actin-VHH-TagRFP coding sequence from pAC-TagRFP (Chromotek) and adding attB1/B2R sites (Table S1) to generate pME-AC-TagRFP. fli1a:AC-tagRFP construct was generated using the Tol2 Kit67 and components listed above. Tg(fli1a:dCas9, cryaa:Cerulean)sh512 was generated by co-injecting fli1a:dCas9, cryaa:cfp plasmid with Tol2 mRNA. Embryos were injected at one-cell stage with 25 ng/μl Tol2 mRNA and corresponding plasmid DNA.

mRNA microinjections

Microinjections of both vegfa16563 (300 pg), tmem33 (250 pg) and tmem33-gfp (1200 pg) mRNA were performed on single-cell-stage embryos with 1 nl injection volume.

RNA in situ hybridisation and immunohistochemistry

Alkaline phosphatase wholemount in situ hybridisation experiments were performed using standard methods as described previously71. Detailed protocols are available upon request. EC dCas9 expression was detected using Cas9 in situ probe72. Immunohistochemistry to detect pERK was performed using Phospho-p44/42 Erk1.2 (Thr202.Tyr204) Rabbit mAb (#4370, cell signal, 1:250) and quantified by normalising EC signal against ERK staining within the neural tube as described7,73. Immunohistochemistry to detect dCas9 was performed on whole-mount and sectioned embryos as described74 using mouse anti-CRISPR/Cas9 (7A9-3A3) (Novus Biologicals, NBP2-36440, 1:100), chicken anti-GFP (Abcam, ab13970, 1:500) primary antibodies, goat anti-mouse IgG (H&L) Alexa Fluor® 647 (Thermo Fisher A21235, 1:1000), and goat anti-chicken IgY (H&L) Alexa Fluor® 488 (Thermo Fisher A11039, 1:1000) secondary antibodies. Sectioned embryos were fixed at 3 dpf in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, washed into 30% sucrose and sectioned at 14 μm thickness on a Jung Frigocut cryostat (Leica).

Quantitative RT-PCR

qRT-PCR was performed using Taqman™ assays according to the manufacturer’s instructions (see Supplementary Methods for probe details). RNA was extracted from batches of 20 or 30 whole embryos per repeat using Trizol®, as a template for complementary DNA synthesis (Verso™ cDNA synthesis kit, Thermo Fisher). A 7900 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) was used for qPCR experiments. Gene expression levels were normalised to eef1α and for each comparison the experimental group was normalised to their relative control unless otherwise stated. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Results display triplicate 2−ΔΔCT values and SEM (unless otherwise stated).

Image acquisition and analysis

For light sheet imaging, embryos were anaesthetised using tricaine in E3 medium and mounted in 1% agarose. A light sheet Z.1 system was used and images were acquired using ZEN software (Zeiss). For confocal microscopy, still images were taken using an Ultraview VOX confocal spinning disc system (Perkin Elmer), Zeiss LSM880 with Airyscan and Leica SP5. Images were analysed using Volocity®V5.3.2, ZEN software (Zeiss) and Leica LCS Confocal software. In cases where samples displayed drift during time lapses, these were corrected using the translation algorithm in ZEN (Blue Edition).

Calcium imaging

Calcium oscillations were quantified using 12–14 SeAs between 24 and 28 hpf on a Zeiss Lightsheet Z.1. All time lapses were taken at 3 µm z-intervals at 20 frames per second (fps) with an acquisition time of 4–6 s per stack using a × 20 objective lens for 300 s. Changes in fluorescence over time were measured throughout the DA to establish a baseline. Changes in fluorescence measured in tip cells were determined to be peaks by subtracting mean DA fluorescence. Changes in fluorescence were normalised to DA baseline values. In experiments where ectopic Ca2+ oscillations were induced in the DA, the mean DA value of control embryos was used to normalise datasets. Absolute calcium peak number was quantified and averaged per SeA, per minute. FIJI was employed to quantify fluorescence intensity. Tip cells were manually segmented as regions of interest and mean and peak fluorescence (arbitrary units) were determined.

Pharmacological treatment

VEGF inhibition using Tivozanib/AV951 (500 nM), Notch inhibition using DAPT (100 μM) or inhibition of F-actin polymerisation using Latrunculin B (380 nM) was conducted using dechorionated embryos between 24 and 28 hpf in E3 medium with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a control. SERCA inhibition using Thapsigargin (5 μM) was performed for 45 min before immediate imaging using a Perkin Elmer Spinning Disk. SOCE inhibition using SKF-963656 (50 μM) dissolved in water was performed on dechorionated embryos using untreated embryos as control. The effect of SKF-96365 treatment on EC proliferation and migration (Supplementary Fig. 14) was performed using continuous exposure to compound within a light sheet chamber using SKF-96365 at a concentration of 50 μM within 0.7% agarose mounting medium and surrounding E3 medium + Tricaine. Embryos were treated from 21 hpf and imaged between 24 and 30 hpf. One to two embryos were imaged for each individual condition and three congruent repeats of each condition were performed.

Calculation of DA blood flow velocimetry

Single Z-plane time lapses of 3 dpf zebrafish DA were acquired at 66 fps using a Zeiss Lightsheet Z.1 microscope. The resulting images were subjected to axial line scan particle image velocimetry designed for Lightsheet imaging using custom authored scripts in MATLAB 2017b®. Each time lapse was analysed frame by frame using intensity-based thresholding of circulating erythrocytes. Thresholded images were made binary followed by conversion of two-dimensional image to one-dimensional (1D) signal by summing up in ‘y’ direction (all column pixels). The 1D signal was low pass filtered to remove spurious and highly correlated pixels (low correlation implies displacement of 1D wave signal). Cross-correlation across time was calculated on filtered images for each time frame using inbuilt MATLAB 2017b® functions. Thus, the obtained correlation (in pixels/frames) was then converted to mm/s using the following equation:

Algorithm is available on request.

siRNA-TMEM33 knockdown in HUVEC

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of TMEM33 gene expression in HUVEC cells was performed using ON-TARGET-plus SMART pool human TMEM33 (Thermo Scientific). ON-TARGET-plus non-targeting pool control duplexes (Thermo Scientific) were used as a control. For siRNA transfection, HUVECs (Cellworks, ZHC-2301) were plated in 0.1% gelatin pre-coated six-well tissue culture plates (3 × 105 cells/well) and incubated overnight. The following morning, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated in serum-free, antibiotic-free OPTIMEM medium for 1 h. Then, 100 pmol of siRNA/well were transfected using 5 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Scientific). Transfection medium was removed after incubation for 6 h and substituted by ECGM supplemented with ECGM-supplement mix and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were incubated for 72 h and then used for further experiments.

Wound-healing EC migration assay

Cell migration of HUVECs and MLECs, treated as indicated, was assayed using the Cytoselect™ 24-well Wound Healing Assay kit (Cell Biolabs). Images were captured with a Nikon DSFi1 digital camera coupled to a Nikon ECLIPSE TS100 microscope at × 4 magnification. Cell-free area was quantified with ImageJ software.

Matrigel EC tube-formation assay

HUVECs transfected with the corresponding siRNA were plated onto Geltrex Reduced Growth-Factor Matrix (Invitrogen) in Medium 200 with no phenol red and supplemented with 2% foetal calf serum and VEGF (25 ng/ml) when indicated. Tube formation was quantified after incubation at 37 °C for 16 h. Images were recorded with a Nikon DSFi1 digital camera coupled to a Nikon ECLIPSE TS100 microscope at 4× magnification.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis employed two-tailed tests and are described in figure legends. All error bars display the mean and SD, except for qPCR error bars, which display the mean and SEM. Numbers of experimental repeats are listed in figure legends. P-values, unless exact value is listed, are as follows: * < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001 and **** < 0.0001. F-values, t-values and degrees of freedom are listed in individual figure legends.

Reporting Summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this Article.

Supplementary Information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Honoré for personal communication, helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank D. Stainier for the pT3TS-dCas9 plasmid; K. Kawakami for the pTol2UASGCaMP7a plasmid; E. Markham and K. Plant for technical support; E. Seward and N. Ogryzko for sharing reagents; and K. Fisher for helpful discussions. This work was supported by a JG Graves Medical Research Fellowship awarded to R.N.W., Royal Society Research grant RG120564 awarded to R.N.W., Diabetes UK grant 17/0005678 awarded to R.N.W., BHF Infrastructure Grant IG/15/1/31328 awarded to T.J.A.C. and R.N.W., BBSRC grant BB/R015457/1 awarded to F.v.E. and R.N.W., NC3Rs grant NC/P001173/1 awarded to T.J.A.C. and R.N.W., and Wellcome Trust Seed Award (210152/Z/18/Z) to R.B.M. A.M.S. was funded by a Jules Thorne PhD scholarship awarded to R.N.W. and T.J.A.C.

Author contribution

R.N.W. conceived the project. A.M.S., F.v.E., A.L.A., H.L.W. and R.N.W. designed experiments. A.M.S., S.K., Y.C., Z.J., R.B.M., H.R.K., K.C., F.V.E. and R.N.W. conducted experiments. A.M.S., S.K., Y.C., Z.J., K.C., R.B.M., A.L.A., H.L.W., F.v.E., T.J.A.C. and R.N.W. analysed data. R.N.W. and A.M.S., aided by the other authors, wrote the paper.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The source data underlying Figs. 1l–m, 2b, d, e, h, i, 3g, j, m, p, 4e, h, i, 5a–c, 6c, f–h, u and 7c, f, g, j, m, p, and Supplementary Figs. 2e, 3d, 4d, e, 5b, d, f, h–j, 6c, f, 7e, h, l, o, 8c , e, g, h, k–m, 9j, k, 10k, l , 12c, f , 13c, f, g, j, m and 14e–h are provided as a Source Data file. A Reporting Summary for this Article is available as a Supplementary Information file.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Timothy J. A. Chico, Robert N. Wilkinson.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-08590-7.

References

- 1.Potente M, Gerhardt H, Carmeliet P. Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell. 2011;146:873–887. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koch S, Tugues S, Li X, Gualandi L, Claesson-Welsh L. Signal transduction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Biochem. J. 2011;437:169–183. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerhardt H, et al. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:1163–1177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siekmann AF, Lawson ND. Notch signalling limits angiogenic cell behaviour in developing zebrafish arteries. Nature. 2007;445:781–784. doi: 10.1038/nature05577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costa G, et al. Asymmetric division coordinates collective cell migration in angiogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:1292–1301. doi: 10.1038/ncb3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meadows KN, Bryant P, Pumiglia K. Vascular endothelial growth factor induction of the angiogenic phenotype requires Ras activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:49289–49298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shin M, et al. Vegfa signals through ERK to promote angiogenesis, but not artery differentiation. Development. 2016;143:3796–3805. doi: 10.1242/dev.137919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi T, Yamaguchi S, Chida K, Shibuya M. A single autophosphorylation site on KDR Flk-1 is essential for VEGF-A-dependent activation of PLC-g and DNA. EMBO J. 2001;20:2678–2778. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran, Q. K. & Watanabe, H. Calcium signalling in the endothelium. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 145–187 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Wythe JD, et al. ETS factors regulate Vegf-dependent arterial specification. Dev. Cell. 2013;26:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanco R, Gerhardt H. VEGF and Notch in tip and stalk cell selection. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2013;3:a006569. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parekh AB. Decoding cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011;36:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oike, M., Gericke, M., Droogmans, G. & Nilius, B. Calcium entry activated by store depletion in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Cell Calcium 16, 367–376 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Vaca L, Kunze DL. Depletion of intracellular Ca2 stores activates a Ca(2)-selective channel in vascular endothelium. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:C920–C925. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.4.C920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng KT, Liu X, Ong HL, Swaim W, Ambudkar IS. Local Ca(2)+entry via Orai1 regulates plasma membrane recruitment of TRPC1 and controls cytosolic Ca(2)+signals required for specific cell functions. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feske S, et al. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liou J, et al. STIM is a Ca2+sensor essential for Ca2+−store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roos J, et al. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Vliet AR, et al. The ER stress sensor PERK coordinates ER-plasma membrane contact site formation through interaction with Filamin-A and F-actin remodeling. Mol. Cell. 2017;65:885–899 e886. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Floch AG, et al. Nuclear pore targeting of the yeast Pom33 nucleoporin depends on karyopherin and lipid binding. J. Cell Sci. 2015;128:305–316. doi: 10.1242/jcs.158915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chadrin A, et al. Pom33, a novel transmembrane nucleoporin required for proper nuclear pore complex distribution. J. Cell Biol. 2010;189:795–811. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang D, Vjestica A, Oliferenko S. The cortical ER network limits the permissive zone for actomyosin ring assembly. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:1029–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakabe I, Hu R, Jin L, Clarke R, Kasid UN. TMEM33: a new stress-inducible endoplasmic reticulum transmembrane protein and modulator of the unfolded protein response signaling. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015;153:285–297. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3536-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urade T, Yamamoto Y, Zhang X, Ku Y, Sakisaka T. Identification and characterization of TMEM33 as a reticulon-binding protein. Kobe J. Med. Sci. 2014;60:E57–E65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bussmann J, et al. Arteries provide essential guidance cues for lymphatic endothelial cells in the zebrafish trunk. Development. 2010;137:2653–2657. doi: 10.1242/dev.048207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaniv K, et al. Live imaging of lymphatic development in the zebrafish. Nat. Med. 2006;12:711–716. doi: 10.1038/nm1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bahary N, et al. Duplicate VegfA genes and orthologues of the KDR receptor tyrosine kinase family mediate vascular development in the zebrafish. Blood. 2007;110:3627–3636. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Covassin LD, Villefranc JA, Kacergis MC, Weinstein BM, Lawson ND. Distinct genetic interactions between multiple Vegf receptors are required for development of different blood vessel types in zebrafish. Proc. . Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:6554–6559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506886103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawson ND, Mugford JW, Diamond BA, Weinstein B. M. phospholipase C gamma-1 is require downstream of vascular endothelial growth factor during arterial development. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1346–1351. doi: 10.1101/gad.1072203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nasevicius A, Larson J, Ekker SC. Distinct requirements for zebrafish angiogenesis revealed by a VEGF-A morphant. Yeast. 2000;17:294–301. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(200012)17:4<294::AID-YEA54>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossi A, et al. Regulation of Vegf signaling by natural and synthetic ligands. Blood. 2016;128:2359–2366. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-04-711192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Astin JW, et al. Vegfd can compensate for loss of Vegfc in zebrafish facial lymphatic sprouting. Development. 2014;141:2680–2690. doi: 10.1242/dev.106591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin M, et al. Vegfc acts through ERK to induce sprouting and differentiation of trunk lymphatic progenitors. Development. 2016;143:3785–3795. doi: 10.1242/dev.137901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hogan BM, et al. Vegfc/Flt4 signalling is suppressed by Dll4 in developing zebrafish intersegmental arteries. Development. 2009;136:4001–4009. doi: 10.1242/dev.039990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Guen L, et al. Ccbe1 regulates Vegfc-mediated induction of Vegfr3 signaling during embryonic lymphangiogenesis. Development. 2014;141:1239–1249. doi: 10.1242/dev.100495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villefranc JA, et al. A truncation allele in vascular endothelial growth factor c reveals distinct modes of signaling during lymphatic and vascular development. Development. 2013;140:1497–1506. doi: 10.1242/dev.084152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brock TA, Dvorak HF, Senger DR. Tumor-secreted vascular permeability factor increases cytosolic Ca2+ and von Willebrand factor release in human endothelial cells. Am. J. Pathol. 1991;138:213–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou Y, et al. STIM1 gates the store-operated calcium channel ORAI1 in vitro. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yokota, Y. et al. Endothelial Ca 2+ oscillations reflect VEGFR signaling-regulated angiogenic capacity in vivo. eLife4, e08817 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Lytton J, Westlin M, Hanley MR. Thapsigargin inhibits the sarcoplasmic or endoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase family of calcium pumps. ournal Biol. Chem. 1991;266:17067–17071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phng LK, Gerhardt H. Angiogenesis: a team effort coordinated by notch. Dev. Cell. 2009;16:196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phng LK, Stanchi F, Gerhardt H. Filopodia are dispensable for endothelial tip cell guidance. Development. 2013;140:4031–4040. doi: 10.1242/dev.097352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tammela T, et al. Blocking VEGFR-3 suppresses angiogenic sprouting and vascular network formation. Nature. 2008;454:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature07083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cermak T, et al. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossi A, et al. Genetic compensation induced by deleterious mutations but not gene knockdowns. Nature. 2015;524:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature14580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.El-Brolosy MA, Stainier DYR. Genetic compensation: a phenomenon in search of mechanisms. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larson MH, et al. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:2180–2196. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leslie JD, et al. Endothelial signalling by the Notch ligand Delta-like 4 restricts angiogenesis. Development. 2007;134:839–844. doi: 10.1242/dev.003244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gray C, et al. Loss of function of parathyroid hormone receptor 1 induces Notch-dependent aortic defects during zebrafish vascular development. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013;33:1257–1263. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zou JJ, Gao YD, Geng S, Yang J. Role of STIM1/Orai1-mediated store-operated Ca(2)(+) entry in airway smooth muscle cell proliferation. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2011;110:1256–1263. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01124.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei C, et al. Calcium flickers steer cell migration. Nature. 2009;457:901–905. doi: 10.1038/nature07577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martini FJ, Valdeolmillos M. Actomyosin contraction at the cell rear drives nuclear translocation in migrating cortical interneurons. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:8660–8670. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1962-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fish JE, et al. Dynamic regulation of VEGF-inducible genes by an ERK/ERG/p300 transcriptional network. Development. 2017;144:2428–2444. doi: 10.1242/dev.146050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luca VC, et al. Structural basis for Notch1 engagement of Delta-like 4. Science. 2015;347:847–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1261093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karkkainen MJ, et al. Missense mutations interfere with VEGFR-3 signalling in primary lymphoedema. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:153–159. doi: 10.1038/75997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kok FO, et al. Reverse genetic screening reveals poor correlation between morpholino-induced and mutant phenotypes in zebrafish. Dev. Cell. 2015;32:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robu ME, et al. p53 activation by knockdown technologies. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McGlincy NJ, Smith CWJ. Alternative splicing resulting in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: what is the meaning of nonsense? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008;33:385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guruharsha KG, et al. A protein complex network of Drosophila melanogaster. Cell. 2011;147:690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wales, P. et al. Calcium-mediated actin reset (CaAR) mediates acute cell adaptations. eLife5, e19850 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Hartzell, C. A., Jankowska, K. I., Burkhardt, J. K. & Lewis, R. S. Calcium influx through CRAC channels controls actin organization and dynamics at the immune synapse. eLife5, e14850 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Noren, D. P. et al. Endothelial cells decode VEGF-mediated Ca2+ signaling patterns to produce distinct functional responses. Sci. Signal.9, ra20 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Lawson, N. D., Vogel, A. M. & Weinstein, B. M. Sonic hedgehog and vascular endothelial growth factor act upstream of the Notch pathway during arterial endothelial differentiation. Dev. Cell3, 127–136 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Bollig F, et al. A highly conserved retinoic acid responsive element controls wt1a expression in the zebrafish pronephros. Development. 2009;136:2883–2892. doi: 10.1242/dev.031773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blum Y, et al. Complex cell rearrangements during intersegmental vessel sprouting and vessel fusion in the zebrafish embryo. Dev. Biol. 2008;316:312–322, 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chi NC, et al. Foxn4 directly regulates tbx2b expression and atrioventricular canal formation. Genes Dev. 2008;22:734–739. doi: 10.1101/gad.1629408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kwan KM, et al. The Tol2kit: a multisite gateway-based construction kit for Tol2 transposon transgenesis constructs. Dev. Dyn. 2007;236:3088–3099. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]