Abstract

Kounis syndrome (KS) is an acute coronary disorder associated with anaphylactic reactions. The purpose of this report is to identify the features of KS triggered by contrast media on the basis of our experience and from literature review.

We have described a case and literature review of KS triggered by injection of contrast media. Including the present case, we reviewed eleven cases of KS. Six cases developed KS in diagnostic radiology departments.

KS could be induced by intravenous injection of contrast media in the radiology department. Radiologists should recognize this critical condition to ensure appropriate management.

Keywords: Kounis syndrome, Contrast media, Coronary vasospasm, Drug hypersensitivity

1. Introduction

Kounis syndrome (KS) is an acute coronary syndrome induced by inflammatory mediators released during allergic reactions [1,2]. Any type of drug or agent, including contrast materials, can potentially trigger allergic reactions associated with KS [3].

Three variants of KS have been proposed so far [[4], [5], [6], [7]]. The type I variant represents coronary artery spasms induced by acute release of inflammatory mediators in patients with normal coronary arteries and without predisposing factors for coronary artery disease. The type II variant represents coronary thrombosis induced by coronary artery spasm, plaque erosion, or rupture of preexisting atheromatous coronary disease. The type III variant, which is a relatively new discovery, represents thrombosis in drug-eluting coronary stents or coronary stent restenosis.

This relatively new concept of KS is being increasingly recognized among allergists and cardiologists; however, it is not well known among radiologists who routinely handle contrast agents. This report aims to present a case of KS induced by anaphylactic reactions to contrast media and to delineate the clinical features and management approaches of KS associated with contrast media through literature review.

2. Case report

A 60-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for radiation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. He had a history of percutaneous coronary intervention for myocardial infarction about 10 years before in another hospital. Routine electrocardiogram (ECG) findings acquired on the date of admission revealed abnormalities suggestive of an old inferoposterior infarction. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was scheduled for evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Infusion of 80 ml iodinated contrast material iopamidol (Iopamiron 370, Bayer, Osaka, Japan) was started in the CT room in the radiology department, and CT images were successfully acquired. However, shortly after the procedure, the patient reported feeling unwell and experienced numbness of the upper limbs, difficulty in breathing, and loss of consciousness. The pulse rate was 160 beats/min, and the systolic blood pressure was 70 mmHg. Pulse oximetry findings revealed oxygen saturation of 75%.

The radiologist in charge of the CT department immediately adjudged these events to be caused by anaphylactic shock to the iodinated contrast medium and, accordingly, administered the patient an intramuscular injection of 0.3 mg adrenaline on the scanner bed and placed an emergency call to the emergency department (ED). The patient continued to present hoarseness of breath, hypoxia, and low blood pressure. Therefore, the lungs were ventilated with a bag-valve-mask, and the patient was again administered 0.3 mg adrenaline, followed by intravenous fluid, and then transferred to the ED.

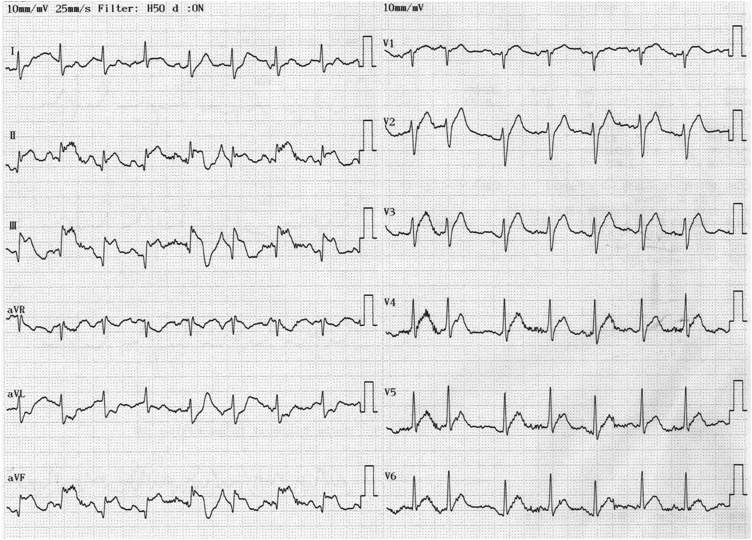

In the ED, the patient was administered 300 mg hydrocortisone sodium succinate, upon which the blood pressure and oxygenation status gradually improved. However, ECG findings acquired in the ED revealed obvious elevation of the ST segment in II, III, aVF, and acute T waves in the precordial leads [Fig. 1]. Since these findings were consistent with acute myocardial infarction, interventional cardiologists were requested.

Fig. 1.

Electrocardiogram findings (consistent with acute myocardial infarction) immediately after transfer to the emergency department.

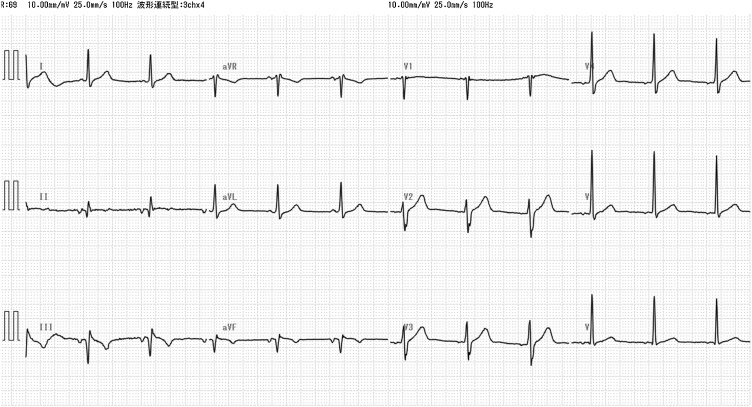

Despite the remarkable ST elevation observed upon ECG, there was only a slight increase in myocardial enzyme levels, and new asynergy on the echocardiogram was not detected. In the following few minutes, ST elevation on the ECG improved [Fig. 2], and the cardiologist suspected KS caused by coronary spasm. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)—although initially considered—was avoided because of its high risk of severe anaphylactic reactions. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and closely monitored by laboratory tests, ECG, and echocardiography under continuous injection of heparin and nicorandil. After 2 days without any further incident, the patient was transferred from the intensive care unit to the general ward. While he did not recognize a history of allergic reaction to contrast media, the patient had experienced hypotension during angiography with iopamidol in another hospital, based on further confirmation after the event. The patient had no history of atopy or allergic reactions to other drugs or substances.

Fig. 2.

Electrocardiogram showing ST-segment resolution.

3. Review of the literature

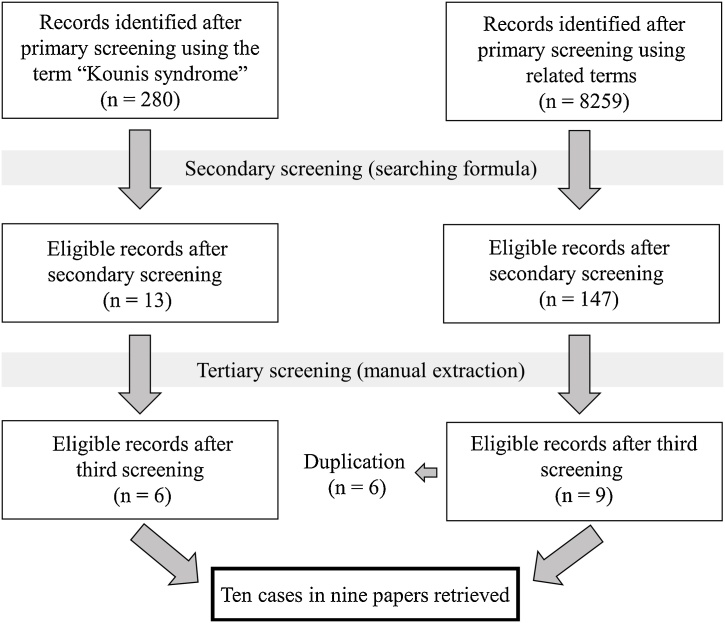

We searched the PubMed database for relevant literature published after January 1991. Primary screening was performed using the key word “Kounis syndrome” or relevant medical subject heading terms, key words, and their combinations, including “heart,” “coronary,” “myocardial infarction,” “coronary vasospasm,” “angina,” “arrest,” “allerg*,” “anaphyla*,” and “hypersensitivity”. Secondary screening was performed using terms such as “contrast” and “agent” or “media,” “medium,” or “material”. All search formulas are presented in Supplement 1. Only English language reports were included. Tertiary screening for identifying cases of KS associated with contrast materials was performed by manual retrieval of cases from eligible reports. From each report on contrast-medium-associated KS, we retrieved data regarding age, sex, type of contrast materials, disease severity, and outcome.

Fig. 3 presents a schematic diagram of the selection process for literature review. To date, excluding the present case report, ten cases of KS associated with contrast materials have been reported. Thus, we reviewed a total of eleven cases of KS triggered by contrast media [Table 1].

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of selection process for literature review.

Table 1.

The reported cases of Kounis syndrome induced by contrast media.

| Study | Sex | Age (years) |

History of Allergy/Cardiac Diseases | Trigger-to-Onset Time | Clinical Presentation | Type of KS | ECG Manifestation | Diagnostic Method | Treatment | Cardiac Complications | Contrast Agent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park JM et al. [29] | Male | 54 | DM; asymptomatic coronary disease; allergy (-) |

30 min (CTCA) | Chest pain; flushing; shortness of breath |

II | ST elevation (precordial) | CAG; CTCA | Methylprednisolone; chlorpheniramine; cimetidine; morphine; heparin; aspirin; clopidogrel; stenting | Hypotension | Unknown |

| Oh KY et al. [30] | Male | 74 | Nausea and vomiting to CM | After administration (CT) | Loss of consciousness | I | ST elevation (II, III, and aVF) | CAG (normal) | Adrenaline; chlorpheniramine; methylprednisolone | Cardiac arrest | Iopromide |

| Kogias JS et al. [31] | Male | 48 | Heavy smoker; MI (post-DES); allergy (-) | 10 min (CT) | Paleness; dizziness; retrosternal discomfort | III | ST elevation (I and aVL); precordial acute T waves | Troponin I; cardiac enzymes; CAG | Hydrocortisone; diphenhydramine; ranitidine; heparin; nitroglycerin; stenting | AMI (intrastent stenosis) | Iopromide (Ultravist) |

| Wang CC et al. [32] | Male | 73 | Smoker; angina; right CCA stenosis; allergy (-) | Immediately (CAG) | Dyspnea; dizziness; cold sweat; blurred vision | I | Unknown | CAG (complete occlusion of LAD and LCX) | IABP; intracoronary nitrates; hydrocortisone; diphenhydramine; fluid therapy; blood transfusion; dopamine; adrenaline | VF; VT; complete AV block; AMI | Iohexol (Omnipaque) |

| Wang CC et al. [32] | Male | 64 | MI (anterior, post-PCI) | Immediately (CAG) | Respiratory distress; angioedema; skin rashes | I | Unknown | CAG (complete occlusion of RCA) | Intubation; mechanical ventilation; fluid therapy; dopamine; IABP; intracoronary nitrates; hydrocortisone; diphenhydramine; adrenaline | Hypotension | Iohexiol |

| Kocabay G et al. [33] | Male | 62 | Pancreatic cancer; allergy (-) | During infusion (CT) | Nausea; loss of consciousness; no pulse | I | ST elevation (II, III, aVF, and precordial) | ECG | Adrenaline | Hypotension | Iohexol |

| Yanagawa Y et al. [34] | Male | 51 | DM; hypertension; chest pain (inferior wall ischemia, suspected by SPECT); allergy (-) | 10 min (CAG) | Chest pain; generalized urticaria; itching; chills | II | ST elevation (anterior) | CAG (complete occlusion of the mid-segment of LCA); prick test | Stenting; steroid; anti-histamine | VF | Iopromide (Ultravist) |

| Zlojtro M et al. [35] | Female | 46 | DM; prolactinoma; allergy to CM; antibiotics | 10 min (MRI) | Generalized urticaria; angioedema | I | ST elevation (inferolateral) | CAG (normal) | Methylprednisolone (pre-medication); adrenaline; chloropiramine chloride; methylprednisolone; fluid therapy | Hypotension | Gadoterate meglumine (Dotarem) |

| Del Furia F et al. [36] | Male | 61 | Chest pain at rest; smoker; allergy (-) | A few min (CAG) | Diffuse erythema; chest pain | II | ST elevation (V1–V5) | CAG (complete occlusion of LAD and diffuse vasospasm of LCX) | Hydrocortisone; hydroxyzine; noradrenaline; fluid therapy; stenting | Hypotension | Unknown |

| Hamilos MI et al. [37] | Male | 51 | Smoker; hyperlipidemia; allergy to aspirin and agricultural chemicals | 90 min (CAG) | Chest pain; nausea; sweating | I | ST elevation (II, III, and aVF) | CAG (complete occlusion of RCA due to vasospasm) | Corticosteroids; antihistamine; intravenous nitrates; heparin; intracoronary nitrates | AMI (vasospasm; mild elevation of cardiac enzymes) | Unknown |

| Present case | Male | 60 | MI (inferoposterior; post-PCI); allergy to CM |

After administration (CT) | Feeling unwell; numbness of upper limbs; dyspnea; loss of consciousness | II | ST elevation (II, III, and aVF); acute T waves (precordial leads) | ECG | Adrenaline; fluid therapy; hydrocortisone; heparin; nicorandil | Hypotension | Iopamidol |

KS, Kounis syndrome; ECG, electrocardiography; CT, computed tomography; DM, diabetes mellitus; CTCA, CT coronary angiography, CAG, coronary angiography; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CM, contrast media; MI, myocardial infarction; DES, drug-eluting stent; CCA, common carotid artery; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; IABP, intraaortic balloon pumping; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia; AV, atrioventricular; RCA, right coronary artery; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

In five of these eleven cases, KS was associated with coronary arteriography (CAG), and nearly complete flow restoration was achieved by immediate primary stenting and/or intracoronary injection of nitrates. The remaining six patients experienced catastrophic events related KS in diagnostic radiology departments. Of these six patients, three had a history of coronary disease and were suspected as having type II KS. Two of these three patients underwent PCI, and the other one was treated by the administration of heparin and nicorandil. The remaining three patients, who were diagnosed with type I KS, were managed by anti-allergic or anaphylactic therapy, although two of these patients underwent CAG, which revealed normal findings in coronary arteries.

Four patients (36%) had a history of allergic reactions, and three of them were diagnosed with type I KS, and the other one was suspected with type II KS. The interval between injection of contrast material and onset of KS ranged from immediately after injection to 90 min later. All patients, including the present one, presented typical clinical features of anaphylactic reactions with acute coronary disease, including ST elevation on ECG findings. Triggers of KS included iopromide (n = 3), iohexiol (n = 3), iooamidol(n = 1), gadoterate meglumine (n = 1), and other unknown iodinated contrast materials (n = 3).

Administration of adrenaline was reported in six cases (55%). Intravenous steroids and anti-histamine drugs were administered in ten (91%) and nine (82%) cases, respectively. Vasodilators for coronary arteries, including intravenous and intracoronary nitrates and nicorandil, were administered in five cases (45%). Anti-platelet drugs, heparin, morphine, and/or dopamine were also administrated in some cases. Severe cardiac complications, including myocardial infarction, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, and/or complete atrioventricular block, were reported in five patients (45%). However, all patients had recovered from KS and had been discharged.

4. Discussion

Kounis syndrome (KS) was recently described as “allergic angina syndrome” by Kounis et al. [1]. It is characterized by cardiovascular allergic and anaphylactic reactions to various allergic stimuli. Following exposure to an allergic stimulus, activated mast cells released histamine, leukotrienes, and serotonin. In typical cases of severe allergic or anaphylactic reactions, these mediators trigger a catastrophic hemodynamic response caused by vascular dilation and hyperpermeability. In KS, these inflammatory mediators cause spastic contraction of smooth muscle cells in the walls of coronary arteries [8]. The exact pathophysiologic mechanism remains unclear. However, some histological reports have confirmed infiltration of mast cells, eosinophils, and lymphocytes in coronary lesions [[9], [10], [11]]. This disease can cause not only vasospastic angina but also fetal myocardial infarction [12].

Accurate diagnosis of the three variants of KS is important for disease management in the acute phase and, in particular, for determining whether or not acute coronary disease caused by KS is reversible. Although the present case was suspected with type II KS because he had a history of coronary arteriosclerotic disease, ST elevation on the ECG was reversible without coronary intervention. The patient also had a history of allergy-like reactions during his previous transarterial chemoembolization. Abdelghany at al. reported that 25% of patients diagnosed with KS have a known history of allergic reactions [3]. Careful review of clinical history of arteriosclerotic disease and allergic reactions is extremely important for appropriate treatment for different types of KS.

The actual etiology of KS is still unclear. Antibiotics are the most frequent triggers [3,[13], [14], [15]], although insect bites [[16], [17], [18]], anticancer drugs [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23]], bee stings [[24], [25], [26], [27], [28]], and anesthetics [29,30] have also been reported to be causative factors. Despite its rare incidence, improvement in awareness of KS among physicians might have led to the recent increase in case reports related to KS. There are also a few case reports of KS associated with different types of contrast materials. Low-osmolar non-anionic contrast materials are less toxic than anionic and monomeric contrast materials, however, most of the KS cases described in Table 1 were caused by low-osmolar non-ionic contrast materials. Almost all of these cases have been reported by cardiologists, emergency physicians, or allergists [[31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]]. These reports, including the present case, clearly show that not only intracoronary injection during CAG but also intravenous injection of contrast materials can cause any type of KS. Therefore, in our opinion, diagnostic radiologists who routinely use any type of contrast material should have knowledge of KS.

There is currently no consensus on the treatment method for KS [3]. Treatments directed at clinical symptoms caused by the allergic or hypersensitivity reactions (such as hypotension, dyspnea, and chest pain) are usually administered concurrently with management measures for acute coronary syndrome. The use of adrenaline—the first-choice drug for severe anaphylactic reactions—is controversial, although it has been frequently administered to patients with KS [40]. It may increase the oxygen demand of the myocardium and lead to worsening of ventricular function in ischemic condition. In the present case, we had no choice but to avoid administration of adrenaline, because the patient had severe symptoms associated with anaphylactic reactions. Adrenaline administration should be considered for avoiding death due to anaphylactic shock only if its benefits outweigh the risk of progression of myocardial ischemia.

Although almost all patients in previous case reports underwent CAG, indication of CAG remains a challenge for preventing KS associated with intravenous contrast injection in the radiology department. The effective prevention method for KS is still unclear. Even if another type of contrast medium were usable, additional use of iodinated contrast medium after or during severe anaphylactic reactions is challenging. However, CAG/PCI should be considered in patients with increased levels of cardiac enzymes/troponins or coronary spasm/thrombosis progressing to acute myocardial infarction.

In summary, KS, an acute coronary disease associated with allergic or anaphylactic reactions, could be induced by intravenous injection of contrast medium. Radiologists should recognize this rare but critical disease to ensure rapid diagnosis and appropriate management.

Authors declaration

There are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work. We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors.

Sources of funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient described herein. Institutional review board exemption was granted for this type of study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejro.2019.02.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Kounis N.G., Zavras G.M. Histamine-induced coronary artery spasm: the concept of allergic angina. Br. J. Clin. Pract. 1991;45(2):121–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kounis N.G. Kounis syndrome (allergic angina and allergic myocardial infarction): a natural paradigm? Int. J. Cardiol. 2006;110(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdelghany M., Subedi R., Shah S., Kozman H. Kounis syndrome: a review article on epidemiology, diagnostic findings, management and complications of allergic acute coronary syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017;232:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.01.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biteker M. A new classification of Kounis syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010;145(3):553. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikolaidis L.A., Kounis N.G., Gradman A.H. Allergic angina and allergic myocardial infarction: a new twist on an old syndrome. Can. J. Cardiol. 2002;18(5):508–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kounis N.G. Kounis syndrome: an update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapeutic management. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2016;54:1545–1559. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2016-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itoh T., Nakajima Y., Morino Y. Proposed classification for a variant of Kounis syndrome. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2017;55:e107. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2016-0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanza G.A., Careri G., Crea F. Mechanisms of coronary artery spasm. Circulation. 2011;124(16):1774–1782. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.037283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kounis G.N., Kounis S.A., Hahalis G., Kounis N.G. Coronary artery spasm associated with eosinophilia: another manifestation of Kounis syndrome? Heart Lung Circ. 2009;18(2):163–164. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovanen P.T., Kaartinen M., Paavonen T. Infiltrates of activated mast cells at the site of coronary atheromatous erosion or rupture in myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;92(5):1084–1088. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venturini E., Magni L., Kounis N.G. Drug eluting stent-induced Kounis syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2011;146(1):e16–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.12.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aykan A.C., Zehir R., Karabay C.Y., Özkan M. A case of Kounis syndrome presented with sudden cardiac death. Anadolu Kardiyol. Derg. 2012;12(7):599–600. doi: 10.5152/akd.2012.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renda F., Marotta E., Landoni G., Belletti A., Cuconato V., Pani L. Kounis syndrome due to antibiotics: a global overview from pharmacovigilance databases. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016;224:406–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biteker F.S., Dogan V., Mert K.U., Mert G.O., Biteker M. Kounis syndrome and antibiotics. Ann. Saudi Med. 2014;34(6):556. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2014.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ridella M., Bagdure S., Nugent K., Cevik C. Kounis syndrome following beta-lactam antibiotic use: review of literature. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets. 2009;8(1):11–16. doi: 10.2174/187152809787582462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cervellin G., Neri G., Lippi G., Curti M., Kounis N.G. Kounis syndrome triggered by a spider bite. A case report. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016;207:23–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patsouras N., Kounis N.G. Scorpion bite, a sting to the heart and to coronaries resulting in Kounis syndrome. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2015;19(6):368–369. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.158295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frangides C., Kouni S., Niarchos C., Koutsojannis C. Hypersersensitivity and Kounis syndrome due to a viper bite. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2006;17(3):215–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kounis N.G., Cervellin G., Lippi G. Cisplatin-induced bradycardia: cardiac toxicity or cardiac hypersensitivity and Kounis syndrome? Int. J. Cardiol. 2016;202:817–818. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oneglia C., Kounis N.G., Beretta G., Ghizzoni G., Gualeni A., Berti M. Kounis syndrome in a patient with ovarian cancer and allergy to iodinated contrast media: report of a case of vasospastic angina induced by chemotherapy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2011;149(2) doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.03.104. e62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kounis N.G., Tsigkas G.G., Almpanis G., Mazarakis A. Kounis syndrome is likely culprit of coronary vasospasm induced by capecitabine. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2012;18(2):316–318. doi: 10.1177/1078155211423118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karabay C.Y., Gecmen C., Aung S.M., Guler A., Candan O., Batgerel U., Kalayci A., Kirma C. Is 5-fluorouracil-induced vasospasm a Kounis syndrome? A diagnostic challenge. Perfusion. 2011;26(6):542–545. doi: 10.1177/0267659111410347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang P.H., Hung M.J., Yeh K.Y., Yang S.Y., Wang C.H. Oxaliplatin-induced coronary vasospasm manifesting as Kounis syndrome: a case report. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29(31):e776–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aminiahidashti H., Laali A., Samakoosh A.K., Gorji A.M. Myocardial infarction following a bee sting: a case report of Kounis syndrome. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2016;19(2):375–378. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.179626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bharadwaj P., Joshi A., Banerji A., Singh N. Kounis syndrome: acute myocardial injury caused by multiple bee stings. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 2016;72(Suppl. 1):S178–S181. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puttegowda B., Chikkabasavaiah N., Basavappa R., Khateeb S.T. Acute myocardial infarction following honeybee sting. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-203832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puvanalingam A., Karpagam P., Sundar C., Venkatesan S., Ragunanthanan Myocardial infarction following bee sting. J. Assoc. Physicians India. 2014;62(8):738–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mytas D.Z., Stougiannos P.N., Zairis M.N., Tsiaousis G.Z., Foussas S.G., Hahalis G.N., Kounis N.G., Pyrgakis V.N. Acute anterior myocardial infarction after multiple bee stings. A case of Kounis syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2009;134(3):e129–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ateş A.H., Kul S. Acute coronary syndrome due to midazolam use: Kounis syndrome during a transurethral prostatectomy. Turk Kardiyol. Dern. Ars. 2015;43(6):558–561. doi: 10.5543/tkda.2015.44567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kounis G.N., Hahalis G., Kounis N.G. Anesthetic drugs and Kounis syndrome. J. Clin. Anesth. 2008;20(7) doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2008.06.004. 562–3; author reply 563–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park J.M., Cho J., Chung S.P., Kim M.J. Kounis syndrome captured by coronary angiography computed tomography. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2010;28(5) doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.08.018. 640.e5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh K.Y., In Y.N., Kwack C.H., Park J.S., Min J.H., Kang M.G., Kim S.M. Successful treatment of kounis syndrome type I presenting as cardiac arrest with ST elevation. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2016;129(5):626–627. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.177004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kogias J.S., Papadakis E.X., Tsatiris C.G., Hahalis G., Kounis G.N., Mazarakis A., Batsolaki M., Gouvelou-Deligianni G.V., Kounis N.G. Kounis syndrome: a manifestation of drug-eluting stent thrombosis associated with allergic reaction to contrast material. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010;139(2):206–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang C.C., Chang S.H., Chen C.C., Huang H.L., Hsieh I.C. Severe coronary artery spasm with anaphylactoid shock caused by contrast medium-case reports. Angiology. 2006;57(2):225–229. doi: 10.1177/000331970605700214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kocabay G., Karabay C.Y., Kounis N.G. Myocardial infarction secondary to contrast agent. Contrast effect or type II Kounis syndrome? Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2012;30(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.10.012. 255.e1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yanagawa Y., Tajima M., Ohara K., Aihara K., Matsuda S., Iba T. A case of cardiac arrest with ST elevation induced by contrast medium. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2012;30(9) doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.11.011. 2083.e3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zlojtro M., Roginic S., Nikolic-Heitzler V., Babic Z., Kaliterna D.M., Marinko A. Kounis syndrome: simultaneous occurrence of an allergic reaction and myocardial ischemia in a 46 year old patient after administration of contrast agent. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2013;15(11):725–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Del Furia F., Matucci A., Santoro G.M. Anaphylaxis-induced acute ST-segment elevation myocardial ischemia treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: report of two cases. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2008;20(3):E73–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamilos M.I., Kochiadakis G.E., Skalidis E.I., Igoumenidis N.E., Zaharaki A., Vardas P.E. Acute myocardial infarction in a patient with normal coronary arteries after an allergic reaction. Hellenic J. Cardiol. 2005;46(1):79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazarakis A., Almpanis G.C., Papathanasiou P., Kounis N.G. Kounis syndrome uncovers critical left main coronary disease: the question of administering epinephrine. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012;157(3):e43–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.