Abstract

Health advice for overweight patients in primary care has been a focus of obesity guidelines. Primary care doctors and nurses are well placed to provide evidence based preventive health advice. This literature review addressed two research questions: ‘When do primary care doctors and nurses provide health advice for weight management?’ and ‘What health advice is provided to overweight patients in primary care settings?’

The study was conducted in the first half of 2018 and followed Arksey and O'Malley (2005) five stage framework to conduct a comprehensive scoping review. The following databases were searched: Emcare, Ovid, Embase, The Cochrane library, Proquest family health, Health source (nursing academic), Joanna Briggs Institute EBP database, Medline, PubMed, Rural and remote, Proquest (nursing and allied health) and TRIP using search term parameters. Two hundred and forty-eight (248) articles were located and screened by two reviewers.

Twenty-three research papers met the criteria and data were analysed using a content analysis method. The results show that primary care doctors and nurses are more likely to give advice as BMI increases and often miss opportunities to discuss weight with overweight patients. Body Mass Index (BMI) is often wrongly categorised as overweight, when in fact it is in the range of obese, or not recorded and when health advice is given, it can be of poor quality. Few studies on this topic included people under 40 years, practice nurses as the focus and those with a BMI of 25–29.9 without a risk factor. A ‘toolkit’ approach to improve advice and adherence to evidence based guidelines should be explored in future research.

Keywords: Health advice, Health prevention, Obese, Overweight, BMI, General practitioner, GP, Nurse, Practice nurse, Primary care

1. Introduction

Preventing excessive weight gain and the management of overweight conditions has been the subject of government guidelines and research projects in recent years. Worldwide obesity has nearly tripled since 1975 (World Health Organisation, 2017). WHO (2017) define overweight and obesity as: “Abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health.” Overweight and obesity are of concern in many countries throughout the world causing more deaths than being underweight (World Health Organisation, 2017). This largely preventable health concern has many associated conditions including, cardiovascular disease, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders and some cancers (Australian Government Department of Health and National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013; National institute for Health and Clinical excellence, 2006; World Health Organisation, 2017).

1.1. Body Mass Index and weight status

A popular measure for classifying overweight and obese adults is the Body Mass Index (BMI) which is, weight in kilograms, divided by the square of height in meters (Australian Government and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017; Australian Government Department of Health and National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013; World Health Organisation, 2017). Adults with a BMI equal to or >25.0 are considered overweight and adults with a BMI equal to or >30.0 are considered obese (WHO, 2017). However, variations do occur in the guidance regarding the classification of obesity (Australian Government Department of Health, 2009) and a BMI of 25.0–30.0 is considered pre-obese. While BMI is widely used in Australia to monitor weight (Australian Government and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017), the parameters of pre-obese are not necessarily clearly applied in primary health practice as a trigger for health advice and intervention.

In 2014–15, almost two in three Australian adults were overweight or obese. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) data indicate that 19% more Australians were obese in 2014–15 than in 1995 (AIHW 2017). This increasing prevalence of obesity and its associated comorbidities has a financial impact on the Australian health system. In 2008 the overall cost of obesity to Australian society and governments was estimated to be 58.2 billion. This includes lost productivity, health system and carer costs (https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/health-topics/obesity-and-overweight). Decreasing the burden of overweight and obesity has become a health priority in Australia (AIHW 2017).

In response to the ‘obesity epidemic’, many nations have developed policies and guidelines to assist in the early identification and management of obesity. One example is the National Institute of Clinical Excellence guidelines ‘Obesity management in primary care’ (2006) from the United Kingdom (UK). These are aimed at primary health practitioners such as general practitioners and practice nurses because they are considered the first point of care for overweight and obese individuals (Australian Government Department of Health, 2009; National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013; National institute for Health and Clinical excellence, 2006). Their position within the community setting enables them to identify, assist and treat individuals, and relay important health messages to promote a healthy lifestyle (National institute for Health and Clinical excellence, 2006; National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013).

1.2. Primary health care and the roles of practitioners in early prevention

In 2013, the NHMRC issued clinical practice guidelines, offering approaches to weight management in primary health care (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013). The scope of these guidelines is to promote weight assessment, and give specific advice on weight management when an adult's BMI is >25.0. The NHMRC guidelines (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013) emphasised that the first point of care for the identification of overweight and obesity is at the primary health level as articulated in the NICE Guidelines (National institute for Health and Clinical excellence, 2006). The NHMRC (2013) also refer to the role of general practitioners and nurses working in the community to identify, assist and treat individuals, while relaying positive health and lifestyle messages (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013).

In Australia the Preventative Health Taskforce (Australian Government and Preventive Health Taskforce, 2009) stress that primary care prevention should be targeted at reducing the likelihood of developing obesity as the health consequences are cumulative and not always reversible. Reducing the likelihood of obesity through primary care health advice strategies may be more beneficial and cost effective than weight loss programmes.

1.3. Rationale for research

The World Health Organisation (2017) refers to health promotion as a process by which people are enabled to gain control and improve their health. Improvements in lifestyle, through nutritional and physical activity health advice for overweight individuals, can prevent obesity (Booth and Nowson, 2010) and its associated comorbidities such as hypertension and Type 2 diabetes (Booth and Nowson, 2010; Dorsey and Songer, 2011). The adoption of health promotion strategies such as behavioural change and cognitive theory appear to be common in the giving of health advice (Anderson, 2008; Brauer et al., 2015; Flocke et al., 2005; Grandes et al., 2009; Noël and Pugh, 2002; Sargent et al., 2012). However, before health advice can be initiated, it is important to identify in a timely way those individuals that require it, underpinned by best available evidence.

The aim of this scoping literature review is to examine and map when health advice is offered to overweight patients by general practitioners and nurses in primary care and to understand the nature of the advice provided.

2. Methods

Peters et al. (2017) guidance for population, concept and context (PCC) was used to develop the title of this review and its related research questions. Population (P) in this case is overweight adults, concept (C) is health advice provided by doctors and nurses, and the context (C) is health advice provided in primary health encounters. We identified two questions for the study:

-

1.

When do primary care doctors and nurses provide health advice relating to weight management?

-

2.

What health advice is provided to overweight patients by doctors and nurses in primary care settings?

A scoping review method was chosen for this research as it allowed us to delve deeper ‘beyond effectiveness’ (Peters et al., 2017) which is the focus of a systematic review of quantitative literature. The complexity of weight management by health professionals is often the subject of research from a qualitative or mixed methodology, which is considered to be a potential source of credible evidence (Peters et al., 2017).

Grant and Booth (2009 p.95) refer to a scoping study as a “preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of research literature” Similarly, the Government of Canada & Research and CIoH (2010) describe a scoping review as a project to systematically map literature available on a topic in order to identify concepts, theories, evidence and gaps within current research. They express the notion that this type of study can be used to assess the feasibility of a full synthesis, which may be a concern due to lack of literature available or a vast amount of diverse literature (Government of Canada & Research and CIoH, 2010).

This interpretation of a scoping review highlights the usefulness of this kind of review for the broad and complex topic of health advice given to overweight patients in primary care. A scoping review allows different kinds of current literature to be explored and examined (Daviset al., 2009). Strengths and weaknesses in the literature can be established and this may inform further research and development opportunities.

The complex nature of offering health advice to overweight patients in primary care necessitates a broad review of literature that includes quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods studies and grey literature. As well as allowing exploration of literature from different theoretical frameworks, a scoping review method will identify if any systematic reviews have already been undertaken and identify gaps in the literature that may lead to future exploration (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005).

The five stage framework identified by Arksey and O'Malley (2005) guided this study; identifying the research; identifying relevant studies; study selection; charting the data; and, collating, summarising and reporting the data.

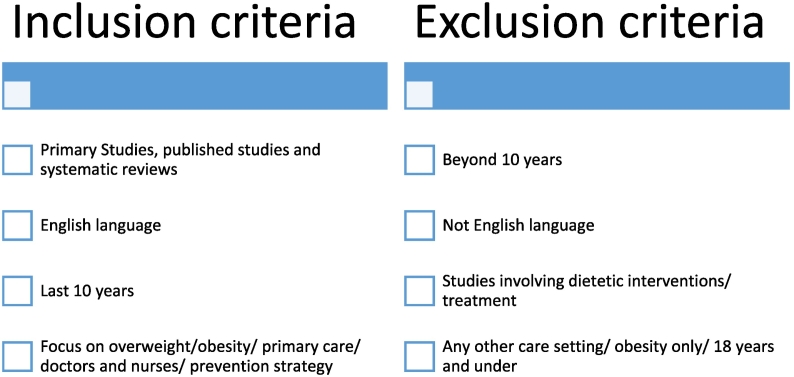

Once the research questions were developed (Stage 1) the researchers identified the search terms for the study. The following electronic databases were searched: Emcare, Ovid, Embase, The Cochrane library, ProQuest family health, Health source (nursing academic), Joanna Briggs Institute EBP database, Medline, PubMed, Rural and remote, Proquest (nursing and allied health) and TRIP. The search terms ‘health advice’, ‘brief advice’, ‘health promotion’, ‘health prevention’, ‘health education’ and ‘obese’, ‘overweight’, BMI ‘weight management’, ‘weight maintenance’, and ‘doctor’, ‘general practitioner’, ‘GP’, ‘physician’, ‘nurs*’, ‘practice nurse’, and ‘primary care’, ‘primary health care’ and ‘community health care’ were used. The terms ‘general practitioners' and ‘nurses' were also used instead of ‘health care professionals’ to keep the focus on the field of general practice rather than dietetics. ‘Physician’ as well as ‘general practitioner’ was used to capture work from an international perspective. Search parameters outlined in the inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Fig. 1. Papers were excluded not based on assessment of study quality but on relevance to the research question. This was utilised to avoid oversaturation of irrelevant literature.

Fig. 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

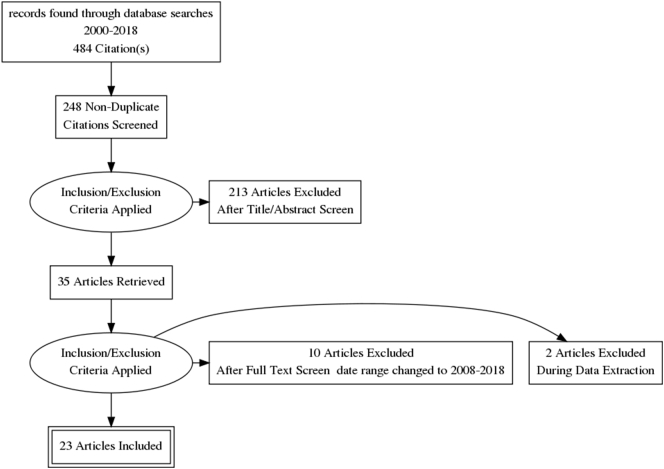

Stage three involved searching of bibliographies for any further articles. In order to manage the vast amount of references, Endnote was utilised and Covidence was used to share the identified literature with the second reviewer. A modified PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 2) was generated to show the way in which studies were selected. During the full text screening process, the date range for inclusion was changed to 2008–2018. The 10 articles generated prior to this did not correspond to the most recent obesity guidelines that were released by NICE (2006). As a scoping literature review is an iterative process (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005), it allows the flexibility to make this change. Two articles were also excluded during data extraction as they had no relevant data.

Fig. 2.

Modified PRISMA flow chart.

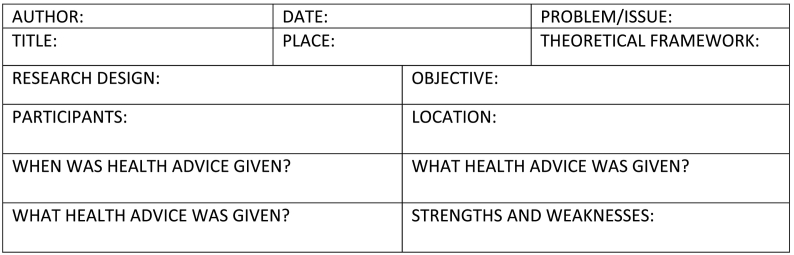

Stage four involved data extraction from the chosen studies using a data extraction tool (Fig. 3). The data extraction tool was adapted from The Joanna Briggs Institute (2015; Arksey and O'Malley, 2005). At this point, it is possible to draw upon Peters et al. (2017) enhancement of previous frameworks for the searching, selecting, extracting and charting of evidence. This enabled the identification of the relevant information for collation into a summary table (Table 1.).

Fig. 3.

Data extraction tool.

Table 1.

Summary table.

| NUMBER/author/year | Location/design/sample | Objective | Theoretical framework | When was health advice given | What health advice was given | Findings | Strengths/weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Alexander et al. (2011) | USA Mixed method 461 patients 40 physicians |

To see if physician weight loss advice results in a change to patient dietary intake, physical activity and weight. | Not explicit. Social cognitive theory/motivational interviewing |

In 63% of encounters of either overweight or obese, BMI 25>. Did not specify BMI category (Overweight or obese) |

Nutrition: 9 subcategories. Physical activity: 6 subcategories. Specific Weight loss advice: 3 categories. |

Combined advice in 34% Physical activity only in 13% Nutrition only in 8% Weight loss only in 3% Patients who received combined advice lost more weight than patients who received no advice but not statistically significant p = 0.08. |

Strengths: Not self- selected and motivated. Large ethnically diverse sample. Weaknesses: Self- report for Not generalizable to young, low income. |

| 2. Barte et al. (2012) | Netherlands Process evaluation. 11 General practices. |

To investigate lifestyle interactions by nurse practitioners compared with general practitioners | Groningen Overweight and Lifestyle (GOAL) Intervention. | BMI 25> | Based on national and international guidelines. | >80% satisfaction that healthy eating and physical activity was useful by the NP. | Weakness: Self report, relies on patient recall. The intervention was not implemented as designed. |

| 3. Brauer et al. (2012) | Canada Qualitative2184 surveys sent to 3 Ontario family health networks. |

To assess patient perceptions of preventive lifestyle counselling in Primary care practice. (Shortly after dieticians joined the family health network and 1 year later). | Not explicit. | Not discussed. | Verbal advice and pamphlets were the most common. Verbal advice 61% initially and 78% 1 year later. Use of pamphlets 34% and 18% 1 year later. Content of advice not reported. |

Overall rate of diet counselling 37%, exercise counselling 24%. Low rates of preventive counselling |

Weakness: Self -report could lead to bias. |

| 4. Clune et al., 2010 | USA Qualitative,793 men and women over 60 |

To examine the prevalence and predictors of health care professionals recommendations to lose weight. | Not explicit. | In those ‘overweight with risks’ 19.8% In those ‘obese with risks’ 52% |

Not reported | 70% of participants met the weight loss criteria but only 36% received advice to lose weight in the past year. | Weakness: Self-report may have led to recall bias |

| 5. Dutton et al. (2014) | USA Cross-sectional survey with 143 respondents |

To examine patient characteristics, physician characteristics and characteristics of the physician/patient relationship associated with weight loss counselling and recommendations provided by physicians. | Not explicit. | Higher BMI was associated with more frequent weight loss counselling, p < 0.001. | Not reported. | A greater number of medical conditions was related to more frequent weight loss counselling, p < 0.05. Female doctors were more likely to give weight loss advice. p < 0.03. |

Weaknesses: Self-report may have led to recall bias. Homogeneous- difficult to compare race and sex. Modest sample size. |

| 6. Eley and Eley (2009) | Rural QLD, Australia Qualitative survey 40 GP practices selected 27 responded. |

To determine whether rural GP's use physical activity as a weight loss strategy and if so, how? | Pope et al. (2000) 5 stage framework | Not reported. | 16 GP practices reported referring to gyms or fitness classes 6 GP practices reported referring to QLD health exercise physiologists and physio. 8 GP surgeries reported using life scripts while 3 stated having never heard of them, 3 noted occasionally using them and 3 considered them a ‘gimmick’ ‘not suitable’ and ‘ineffective’ |

16 GP practices cited motivation and commitment, lack of local facilities and lack of footpaths as barriers to physical activity (relating to rural areas) | Weaknesses: Pilot study. Small sample size. Did not state when they give advice. Did not state what their advice was. |

| 7. Flocke et al. (2014) | USA Mixed method observational study of 811 patient visits to 28 primary care clinicians |

To examine the effectiveness of teachable moments to increase patients' recall of advice, motivation to modify behaviour, and behaviour change. | Health behaviour change. | BMI 25 and over with the presence of a chronic condition. BMI 30 and over with under consumption of fruit and veg |

Not stated. | 86% had at least one opportunity for discussion. 45% had a health behaviour discussion. Missed opportunities 61% |

Weaknesses: No positive association between TM and BMI change at 6 weeks- too short Audio recorder-bias |

| 8. Halbert et al. (2017) | USA Qualitative observational study, cross sectional study. 282 participants |

To examine the receipt of provider advice to lose weight among primary care patients who were overweight and obese. | Not explicit. | 59% of participants advised to lose weight. 41% had not received advice. 40% overweight participants had been advised to lose or maintain weight. |

Not stated | Women were more likely than men to be advised to lose weight. Obese were more likely to report being asked to lose weight than overweight. |

Self –reported may have led to patient recall bias. Cross sectional design led to inability to determine causality of receipt of provider advice. Health advice given was not reported. |

| 9. Harris et al. (2012) | Australia Qualitative survey. 698 participants |

To explore whether education and referral by GP's to patients with smoking, nutrition, alcohol, physical activity and weight (SNAPW) behavioural risk factors is tailored to patients risk and readiness to change. | (Prochaska and Di Clemente, 1986) Stages of behaviour change. | Those given dietary advice had mean BMI of 30.01, those not, mean BMI 27.76 Those given physical activity advice mean BMI 30.23,those not mean BMI 27.52 |

Those with higher BMI recorded were more likely to receive a referral for dietary or physical activity than those with lower BMI score. | High prevalence of behavioural risk factors in diet and physical activity. Diet 72.6% physical activity 57.6%. Mean BMI 28.4. Low frequency of education and referral of patients with SNAPW in general practice. |

Self –reported, potential recall bias. Practices were volunteers that expressed an interest which may have influenced the likelihood of them addressing it. |

| 10. Kable et al. (2015) | Australia Qualitative cross sectional survey. 79 participants, |

To report perceptions, practices and knowledge of nurses about providing healthy lifestyle advice for patients who may be overweight or obese and compare responses from demographic regions. | Not explicit. | 28% measure height and weight 18% measure waist 65% were aware that overweight was defined as BMI 25 and over |

Quality of weight loss advice was not attainable. 72% had no or low level knowledge 44% recommended increasing physical activity. |

74% of nurses provided dietary advice. 81% of nurses provided physical activity advice. Most nurses reported not receiving education Only half of the participants were confident to raise issue |

Weaknesses: Participation was voluntary which may suggest an interest. Low response rate noted, which may have produced a non- response rate bias. Nurses were not all in primary care |

| 11. Korhonen et al. (2014) | Finland Longitudinal cohort study. 2752 at risk subjects. |

To identify overweight and obese with increased cardiovascular risk in the community and provide with lifestyle counselling that is possible to implement in real life. | Not explicit. | BMI 25 and over Waist circumference 80 cm and over in females or 94 cm and over in males. |

Aim to reduce weight by 5% by reducing saturated fat and increasing physical activity to at least 30 mins per day or 4 h per week. | By targeted screening it is possible to find overweight and obese people at increased cardiovascular risk, to induce clinically meaningful, long –term, weight loss or stabilisation in primary care. | Weaknesses: There was no comparison group. 3 year follow up was 42% |

| 12. Noordman et al. (2012) | Netherlands Systematic review RCT, 18 yrs>, lifestyle communication, PCT |

To review literature on relative effectiveness of face to face communication related behaviour change techniques provided in primary care by either physicians or nurse to intervene on patients' lifestyle behaviour. | Reference to Prochaska and Di Clemente's trans theoretical model of behavioural change and Bandura's social cognitive theory. | No difference shown between GP's and nurses' however, few studies include both so caution must be exercised. | Behavioural counselling, motivational interviewing, education and advice are most frequently evaluated as effective face to face communication related BCT's | One primary care professional does not seem better equipped that another to provide face to face related BCT's. | Strengths: High quality strategic review Included studies with rigorous design Weaknesses: Publication bias. Non- English excluded. |

| 13. Pollak et al. (2011) | USA Qualitative40 primary care physicians, 461 encounter |

To analyse time spent on the topic of weight and whether motivational interviewing was used. |

Epstein et al. (2005) patient centred communication. Motivational interviewing. |

Nutritional advice was given on 78% Physical activity advice was given on 82% BMI/weight was taken on 72% |

Not stated. | Mean time of 3.3 min was spent addressing the topic. Obese patients spent longer talking about weight than overweight. |

Weaknesses: Study may not be generalizable to young people with lower incomes. |

| 14. Robertson et al. (2011) | Australia QLD Qualitative1261 participants | To ascertain the extent to which general practitioners in Queensland recommend physical activity to their patients, the types of patients they target, types of activity they suggest and how patients respond to the recommendations. | Not explicit. Health promotion. |

GP's recommended 81% 24.7% was in the last year. 40% of overweight participants were advised to exercise more. 17% had heart problems. 15% had diabetes, asthma or osteoporosis |

75% were advised to walk 13% swimming/aqua aerobics/hydrotherapy/low impact exercise 13% to use gym/weights or aerobics. |

Obese were most likely to be recommended to do more exercise 34%, followed by overweight 15%, acceptable weight 7%, and underweight 4%. | Weaknesses: Self -report may lead to recall and social desirability bias. No description of BMI given. |

| 15. Schauer et al. (2014) | USA Qualitative 30 P.C. physicians, nurses, assistants from 4 multi clinic health centres |

To use qualitative methods to explore how clinicians approach weight counselling, including who, how, what, and what referrals. | Not explicit. | Addressed with all, rapport first, chronic consults, unwritten protocol when to address it, when doing vitals | Specific diets, walking common, increase activity Some develop their own or use existing brochures or handouts. Some told to google weight loss apps. |

Overwhelming majority have no external resources or behavioural treatments, e.g. dietician, classes, programmes. | Weaknesses: Self -report may lead to recall bias. Not generalizable to the whole population. |

| 16. Shay et al. (2009) | USA Comprehensive review of articles | To provide a practical approach to managing overweight and obese adult patients based on data from research and recommendations from established guidelines. | Not explicit. | It should be addressed when BMI is calculated and a diagnosis of overweight or obese is given. | Advice should be: Calorie intake and goal weight, educate, follow up, weight maintenance. |

Nurse practitioners can easily integrate simple, safe, and effective weight management strategies into their practice. | |

| 17. Shuval et al. (2014) | USA Pilot Cross sectional study. 157 patients, |

To examine the reliability and validity of brief sedentary assessment tool for primary care. | 5 A's framework | During routine visits. Most participants were overweight with a mean BMI of 27. |

No specific advice noted. 10% reported sedentary behaviour counselling in the last year. 53% received physical activity counselling 45% advised to modify physical activity time. None received a written plan |

Sedentary behaviour counselling practices are infrequent in primary care clinics. | Weaknesses: No specific advice noted, Self – report, limited sample size, one primary care clinic. |

| 18. Stephens et al. (2008) | USA Qualitative. Survey of 283 participants pre intervention, 386 in post intervention. |

To investigate the effects of a simple visual prompts poster on occurrence of patient/physician weight loss conversation. | 5 A's framework | When patients brought weight up or when GP brought weight up. Not very clear. | Not stated. | 42% reported interest in weight loss but did not discuss it with the physician. Visual prompt poster did not increase proportion of patients reporting they wanted to lose weight. |

Weaknesses: No demographics taken. Poster was not pretested. Not documented who initiated the discussion. |

| 19. Sonntag et al. (2010) | Germany Cross sectional study with 12 GP practices. | To analyse GP encounters with overweight and obese patients. To test whether patients with a BMI 30 or over had longer consultations relating to lifestyle, nutrition and physical activity than those with a BMI under 30. | Not explicit. Behavioural change theory. |

Not clear. During biennial checks of over 35 year olds. | Not stated. | 78% of dialogues were between 0 and 6.76 min. 70% of dialogues had physical activity brought up. Female GPs had longer consults and more consults relating to weight/nutrition than male GP's |

Weaknesses: BMI - self reported may have been influenced by social desirability bias. GP's volunteered- may suggest they were more motivated |

| 20. ter Bogt et al. (2011) | Netherlands. Quantitative. Randomized controlled trial. 11 general practitioners, 457 participants, |

To compare structured lifestyle counselling by nurse practitioners with usual care from GP. To see if results at 1 year were sustained at 3 years. | Not explicit. | BMI 25 or over with a co morbidity. | Not stated. | Preventing weight gain by Nurse practitioners did not lead to better results than GP's. | Strengths: Large population, equal male and female participants, low dropout rate. Weaknesses: Hawthorne effect, participants had to be informed of the study |

| 21. van Dillen et al. (2014) | Netherlands Qualitative. Observational study. 19 practice nurses | To examine the content of Dutch practice nurses' advices about weight, nutrition and physical activity to overweight and obese patients. | Not explicit. | PN initiated/PT initiated. Weight 118/39 Nutrition 161/78 Physical activity 135/66 |

To lose weight. Reduce fat, salt, sugar, alcohol, increase fruit. 1 in 10 included possibility of dietician Be more active- walking, cycling. |

Majority of advice based on guidelines, type II diabetes in particular. Advice based on GP standards for a specific illness. BMI was calculated in 9% Often not tailored |

Weaknesses: No ethics approval Recording may have resulted in bias. |

| 22. Waring et al. (2009) | USA Quantitative |

To examine overweight and obesity management in primary care in relation to Body Mass Index, documentation of weight status, and comorbidities | Not explicit: Behavioural change theory |

The higher the BMI the more likely to have weight status and intervention documented | Behavioural interventions. To lose weight, Physical activity, diet, referral to nutritional counselling |

Documentation of OW/obesity was associated with higher odds of advice to lose weight among OW compared with mild/moderate/severe obesity. Advice was prevalent in >50% of patients with a documented mod/severe obesity. |

Weaknesses: Not generalizable- mostly white non-Hispanic Unclear who initiated the conversations. |

| 23. Yoong et al. (2014) | Australia Qualitative. Cross sectional study. 1111 patients |

To determine extent that Australian GP's recognise overweight and obese patients. | Not explicit. | Not discussed. | Not discussed. | Males without hypertension or type II diabetes had higher odds of not being identified. GP reported prevalence of overweight and obesity was lower than the patient report- 38% v. 53% 12% of obese were categorised as none overweight |

Charting the information from the studies was the final stage. Levac et al. (2010) enhancements in addition to Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) framework were drawn upon to increase consistency and rigour. Three steps were undertaken: 1) analysing data, involving a descriptive numerical summary and a thematic content analysis; 2) reporting the results collated into a table (Table 1) to articulate the findings of the studies; 3) applying meaning involved a content analysis of the results (Levac et al., 2010). Gaps in the literature were identified and recommendations for future research clearly stated.

2.1. Ethical considerations

This review was literature based therefore ethics approval was not sought. Consideration was given to registering with PROSPERO, an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in health and social care, however, it did not meet the criteria outline https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#aboutpage.

3. Results

The data base searches produced 484 journal articles. Duplicates were removed and 248 citations were screened. The exclusion criteria were applied to the title and abstract by two reviewers using Covidence, which excluded 213 articles. Thirty five (35) articles remained after full text screening. A decision was made to change the date range to 2008–2018 to capture more recent work. As a scoping review is considered to be an iterative process (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005), this was deemed appropriate. This excluded an additional 10 articles. During data extraction, 2 articles were found irrelevant to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were also removed. Twenty-three (23) articles were included in this scoping review. This included 2 mixed method studies, 14 qualitative studies, 5 quantitative studies, one systematic review and one literature review. Content analysis identified 4 categories which are reported on below.

3.1. ‘When’ opportunities to give health advice occur

The NHMRC (2013) refer to the ‘usual healthcare provider’, who is most often the GP or practice nurse, as most likely to be involved in giving advice about a healthy lifestyle (p.14). It is suggested that their involvement would include assessing for BMI and health risks and recording them into the individual's records (Australian Government Department of Health and National Health and Medical Research Council (2013). This enables the doctor or nurse to easily identify those in the overweight category, prompting the initiation of health advice.

Clune et al. (2010) carried out a qualitative study in the USA by using questionnaires on 793 participants to examine the prevalence and predictors of health care professionals recommendations to lose weight. They found that 70% of participants met the weight loss criteria but only 36% received advice to lose weight in the past year. However, the study used self – reported data which may have led to recall bias. This notion of missed opportunities for health behaviour discussion is emphasised in the work of Flocke et al. (2014) who examined the effectiveness of teachable moments to increase patients' recall of advice. This was a mixed method observational study of 811 patient visits to 28 primary care clinicians and showed that there were missed opportunities in 61% of observed discussions. Another study which detected a low frequency of education and referrals was Harris et al. (2012). They carried out a qualitative survey of 698 participants and found a high prevalence of behavioural risk factors in diet and physical activity. 72.6% of participants had behavioural risk factors relating to diet and 57.6% of participants had risk factors relating to physical activity. Despite the high figures, a low frequency of education was detected. Stephens et al. (2008) also noted a large number of missed opportunities. They carried out a qualitative study to investigate the effects of a simple visual prompts poster on occurrence of patient/physician weight loss conversation. They found that 42% of patients reported an interest in weight loss but did not discuss it. Although, this study does have notable limitations. The poster was not pre tested and it was not clear whether the GP or the patient brought up weight.

van Dillen et al. (2014) carried out a study in the Netherlands to examine the content of Dutch practice nurses' advice about weight, nutrition and physical activity to overweight and obese patients. This study was a qualitative, observational study of 19 practice nurses, all female. They found that practice nurses initiated conversations around weight, nutrition and physical activity more than their patients. The results may however have been subject to a social desirability bias due to the recording of the conversations. Barte et al. (2012) carried out a study relating to lifestyle interactions carried out by nurse practitioners or a GP. They found that 80% of patients felt the nurse practitioner was satisfactory (Barte et al., 2012).

While van Dillen et al. (2014) found that nurses brought weight up more than patients, it is important to consider who is best placed to bring up weight with patients. ter Bogt et al. (2011) found that patients receiving weight gain prevention strategies given by nurses did not lead to better results than by the GP and similarly, Noordman et al. (2012) found that one primary care professional does not seem to be better than another. However, Dutton et al. (2014) did find that female doctors were more likely to give health advice to lose weight than male doctors and Sonntag et al. (2010) noted that female doctors had longer consults and more relating to weight. Interestingly, Yoong et al. (2014) found that the prevalence of overweight and obesity was reported to be lower by the GP than the patient. 53% of the patients in their study identified as overweight or obese while the GP reported only 38%. It was also reported by Yoong et al. (2014) that 12% of obese were categorised as non - overweight. This finding highlights that there may be barriers faced by doctors and nurses in their identification of overweight patients. While this may be due to lack of time, or poor education (Bocquier et al., 2005; Rogers et al., 2012), it may also support McClinchy et al. (2013) who suggested that health promotion may not happen as health practitioners feel that it is not effective.

This may explain why weight management is often considered to be the role of the practice nurse. Shay et al. (2009) carried out a comprehensive review of articles and found that nurse practitioners were well placed to simply, safely and effectively integrate weight management strategies into their practice. Barte et al. (2012) carried out research to investigate lifestyle interactions by nurse practitioners. In their process evaluation of 11 general practices, with 457 patients, they found that >80% reported satisfaction with health advice from the nurse practitioner.

The BMI category in many of the studies often does not specify whether the intervention takes place in the overweight or the obese category. For example, Alexander et al. (2011), Barte et al. (2012), ter Bogt et al. (2011) and Korhonen et al. (2014) used a similar grouping of BMI over 25. Including the overweight category into the study is beneficial however, distinguishing between the BMI categories as being overweight or obese would have provided a clearer understanding of the representation of overweight and whether the advice resulted in a change to that group. Waring et al. (2009) also found that general practitioners may document that patients are overweight when they are actually obese. Having more accurate and specific data on the BMI category for lifestyle interactions may lessen the blurring of the boundaries between overweight and obese and may assist in more tailored advice for patients.

Dutton et al. (2014) found that a higher BMI was associated with more frequent weight loss counselling, (p < 0.001). BMI was also found to be a significant factor in weight loss recommendations (p < 0.04). Similarly, Waring et al. (2009) found that the higher the BMI, the more likely patients were to have their weight status and intervention documented. However, van Dillen et al. (2014) found that BMI was calculated in only 9% of patients. Without calculating a BMI, a barrier is formed, disengaging the nurse from providing appropriate health advice to those who require it.

3.2. Barriers to giving health advice

Schauer et al. (2014) carried out a qualitative study to explore how clinicians approach weight counselling. Some describe unwritten protocols of when to address it. For example, they may address it with those they have already built a rapport with, they won't address it with a new patient so as to not ‘get off on the wrong foot’ and, ‘if it's not too offensive’, they will bring it up. This study highlights that some of the barriers discussed in other literature such as lack of time and training (Bocquier et al., 2005; Rogers et al., 2012) continue to be an issue in practice. Having time to build a rapport with patients and being given appropriate training to address the issue in a non-offensive manner may increase the likelihood of it being addressed.

Many studies only included overweight participants if there was a comorbidity present. The NHMRA (2013) suggest screening and managing comorbidities in their standard care for those in the overweight BMI range. However, it does not suggest that advice only be given to those with a comorbidity. ter Bogt et al. (2011), Clune et al. (2010), Flocke et al. (2014) and Korhonen et al. (2014) only included the overweight category in their study if the participants had a comorbidity. This is interesting, as health advice would be suited to patients in the overweight category regardless of comorbidity and having the advice sooner may lead to less people developing a comorbidity. Dutton et al. (2014) found that having more medical conditions equalled more frequent counselling. This may relate to Schauer et al. (2014) who found that clinicians were more inclined to bring up weight while in a consult for a chronic condition as opposed to an acute condition.

The literature reviewed also demonstrated an under representation of people in the age category of 18–40 years. An Australian study by Harris et al. (2012) carried out a qualitative survey of 698 participants aged between 40 and 55 years with hyperlipidaemia or hypertension or aged 56–64 years. Those not given dietary advice had a mean BMI of 27.76, the overweight category. Those not given physical activity advice had a mean BMI of 27.52, the overweight category. Clune et al. (2010) also carried out a study in those over 60 years and found low rates of health advice given. As many studies require their overweight participants to have a comorbidity, this may explain the age category of over 40 years as there may be more prevalence in that age category. The presence of the chronic disease may also mean that they present more to the doctor or nurse. People under 40 may also be less likely to go to the GP in general as they may have fewer health issues.

3.3. Nature of the health advice provided

3.3.1. Nutrition

Alexander et al. (2011) found that health advice relating to nutrition was given to only 8% of patients in their study. Brauer et al. (2012) highlight that verbal advice and pamphlets were the most common in diet and exercise counselling. The exact content of the advice was not reported. The use of pamphlets in health advice was also noted by Schauer et al. (2014). They found that some clinicians develop their own or use existing brochures or handouts. The reliability of pamphlets or handouts could be questioned as they may be out of date or disease specific. The array of nutritional information that was given as health advice in Schauer et al. (2014) emphasises the inconsistency around this advice. Some patients were advised to google weight loss apps. Given the oversaturation of weight loss applications and uncertainty of their validity, reliability and use of evidence based practice guidelines, this advice may prove to be of poor quality. It is interesting to note that Schauer et al. (2014) found that the overwhelming majority of primary health care facilities have no external resources or behavioural treatments, for example dietician, classes and programmes. Most existing ones are for diabetes (Schauer et al., 2014). Kable et al. (2015) state that 72% of the nurses in their study had no or low level knowledge about best practice dietary management for overweight. This emphasises the training barriers associated with health advice as discussed by Rogers et al. (2012) and Schauer et al. (2014). It also highlights that education in the form of a toolkit for doctors and nurses, similar to those in other chronic diseases may be useful (Glenister et al., 2017).

3.3.2. Physical activity

Physical activity advice is one part of the multicomponent nature of health advice for weight management. Alexander et al. (2011) found that physical activity advice occurred in 13% of primary care encounters in their study. There was no reference made to whether the advice given derived from evidence based practice or local and national guidelines. This may have influenced the effectiveness of the advice given. Eley and Eley (2009) found that 16 GP practices reported referring to gyms or fitness classes and 6 GP practices reported referring to exercise physiologists and physiotherapists.

Kable et al. (2015) conducted a study to report the perceptions, practices and knowledge of nurses providing healthy lifestyle advice for patients who may be overweight or obese. The quality of the weight loss advice was not attainable. This study reports that 44% of nurses recommended increasing physical activity and 81% of nurses provided physical activity advice. However, most nurses reported not receiving any education in relation to this. It is important to point out that this study included nurses from other areas as well as primary care. This may have influenced the educational level of the nurses as obesity guidelines have targeted primary care workers as those in the best position to provide health advice for weight management. Although, it could be argued that all health care professionals have a duty of care to educate their overweight patients with evidence based health advice.

Korhonen et al. (2014) targeted screening to overweight and obese giving specific health advice relating to physical activity. This advice was to increase physical activity to at least 30 min per day or 4 h per week. While the study does give detail of the advice given, it does not state the evidence base. Robertson et al. (2011) found that 75% of their study participants were advised to walk. Similarly, Schauer et al. (2014) and van Dillen et al. (2014) also reported that very general physical activity recommendations such as walking were used. van Dillen et al. (2014) emphasise that the majority of advice was based on guidelines, type 2 diabetes in particular, or on GP standards for specific illnesses. They report that tailored education was seldom provided. Again, the use of guidelines for other chronic diseases in relation to health advice for overweight patients suggests that the work of Glenister et al. (2017) referring to a ‘toolkit’ approach to break down some of the barriers to offering weight related advice is important.

4. Study strengths and limitations

To ensure quality, this review was conducted following the guidelines set out by the Peters et al. (2017). Strengths include the use of many databases for depth and breadth of coverage, the use of search terms that consider the language of other countries and a strict inclusion and exclusion criteria.

While every attempt was made to ensure that this study was of high quality some limitations apply including the strict 10 year inclusion criteria and the use of English language only research.

5. Conclusion

The literature reviewed in this study has highlighted that there continues to be poor documentation of BMI by doctors and nurses in primary care. Health advice is more likely to be given when BMI increases and can be of poor quality due to educational barriers and availability of resources. Primary care doctors and nurses are well positioned to give weight related health advice. Female practitioners are more likely to raise the topic of BMI and weight control than male practitioners. Very few studies have documented the exact health advice that was given. Barriers to giving health advice to overweight patients in primary care continue to be problematic and need to be acted on to improve population health.

6. Future recommendations

Future recommendations involve the potential of a study which is:

-

•

Longitudinal

-

•

Has primary care nurses as the focus

-

•

Records when BMI is taken and documented

-

•

Details what health advice is given to patients that are overweight

-

•

Includes participants from the age range of 18 +

-

•

Includes participants from all social demographics

These data could be used to generate a tool kit that could be distributed to primary care nurses that provides standardised education for giving brief health advice to overweight patients. This gives clear instructions that link current overweight and obesity guidelines into practice by offering quality, evidence based, brief, nutrition and exercise advice. The tool kit could include quality assessed posters for waiting rooms, strategies for screening patient loads, in order to be proactive in offering preventive advice, and assistance in individualising advice while keeping it brief and simple.

Formatting and funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the University of South Australia library staff for continuous support with this project.

References

- Alexander S.C., Cox M.E., Yancy W.S. Weight-loss talks: what works (and what doesn't) J. Fam. Pract. 2011;60(4):213–219. (01 Apr) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P. Reducing overweight and obesity: closing the gap between primary care and public health. Fam. Pract. 2008;25(1):i10–i16. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government & Australian Institute of Health and Welfare About overweight and obesity viewed 25/10/2017. 2017. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-statistics/behaviours-risk-factors/overweight-obesity/overview

- Australian Government & Preventive Health Taskforce Obesity in Australia: a need for urgent action, NPHT, viewed 14/10/2017. 2009. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/preventativehealth/publishing.nsf/Content/E233F8695823F16CCA2574DD00818E64/$File/obesity-jul09.pdf

- Australian Government Department of Health About overweight and obesity, DOHA, viewed 14/10/2017. 2009. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-strateg-hlthwt-obesity.htm

- Australian Government Department of Health & National Health and Medical Research Council Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children in australia, NHMRC, Melbourne, viewed 14/10/2017. 2013. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/n57_obesity_guidelines_140630.pdf

- Barte J.C.M., Bogt N.C.W., Beltman F.W., van der Meer K., Bemelmans W.J.E. Process evaluation of a lifestyle intervention in primary care: implementation issues and the participants' satisfaction of the GOAL Study. Health Educ. Behav. 2012;39(5):564–573. doi: 10.1177/1090198111422936. (October) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocquier A., Verger P., Basdevant A. Overweight and obesity: knowledge, attitudes, and practices of general practitioners in France. Obesity. 2005;13(4):787–795. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A.O., Nowson C.A. Patient recall of receiving lifestyle advice for overweight and hypertension from their general practitioner. BMC Fam. Pract. 2010;11(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer P.M.P.R.D., Sergeant L.A.B.R.D., Davidson B.M.R.D., Goy R.M., Dietrich L.M.R.D. Patient reports of: lifestyle advice in primary care. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2012;73(3, Fall):122–127. doi: 10.3148/73.3.2012.122. (2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer P., Gorber S.C., Shaw E. Recommendations for prevention of weight gain and use of behavioural and pharmacologic interventions to manage overweight and obesity in adults in primary care. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2015;187(3):184–195. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clune A., Fischer J.G., Lee J.S., Reddy S., Johnson M.A., Hausman D.B. Prevalence and predictors of recommendations to lose weight in overweight and obese older adults in Georgia senior centers. Prev. Med. 2010;51(1, Jul):27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K., Drey N., Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009;46(10):1386–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey R., Songer T. Peer reviewed: lifestyle behaviors and physician advice for change among overweight and obese adults with prediabetes and diabetes in the United States, 2006′. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2011;8(6) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton G.R., Herman K.G., Tan F. Patient and physician characteristics associated with the provision of weight loss counseling in primary care. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2014;8(2, Mar–Apr):e123–e130. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eley D.S., Eley R.M. 'How do rural GPs manage their inactive and overweight patients? A pilot study of rural GPs in Queensland. Aust. Fam. Physician. 2009;38(9):747–748. (Sep 2009 2014-03-23) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R., Franks P., Fiscella K. Measuring patient-centered communication in Patient Physician consultations: Theoretical and practical issues. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005;61(7):1516–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flocke S.A., Clark A., Schlessman K., Pomiecko G. Exercise, diet, and weight loss advice in the family medicine outpatient setting. Fam. Med. 2005;37(6):415–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flocke S.A., Clark E., Antognoli E. Teachable moments for health behavior change and intermediate patient outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014;96(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.03.014. (July) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenister K.M., Malatzky C.A., Wright J. Barriers to effective conversations regarding overweight and obesity in regional Victoria. R. Aust. Coll. Gen. Pract. 2017;46(10):769–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada & Research, CIoH, CIoH . 2010. A Guide to Knowledge Synthesis, viewed 14/10/2017.http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41382.html [Google Scholar]

- Grandes G., Sanchez A., Sanchez-Pinilla R.O. Effectiveness of physical activity advice and prescription by physicians in routine primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009;169(7):694–701. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M.J., Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009;26(2):91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbert C.H., Jefferson M., Melvin C.L., Rice L., Chukwuka K.M. Provider advice about weight loss in a primary care sample of obese and overweight patients. J. Prim. Care Community Health. 2017;8(4, Oct):239–246. doi: 10.1177/2150131917715336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M.F., Fanaian M., Jayasinghe U.W. What predicts patient-reported GP management of smoking, nutrition, alcohol, physical activity and weight? Aust. J. Prim. Health. 2012;18(2):123–128. doi: 10.1071/PY11024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable A., James C., Snodgrass S. Nurse provision of healthy lifestyle advice to people who are overweight or obese. Nurs. Health Sci. 2015;17(4, Dec):451–459. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen P.E., Jarvenpaa S., Kautiainen H. Primary care-based, targeted screening programme to promote sustained weight management. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care. 2014;32(1, Mar):30–36. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2014.886493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O'Brien K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010;5(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClinchy J., Dickinson A., Barron D., Thomas H. Practitioner and patient experiences of giving and receiving healthy eating advice. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2013;18(10) doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2013.18.10.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council . National Health and Medical Research Council; Melbourne: 2013. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children in Australia. [Google Scholar]

- National institute for Health and Clinical excellence Obesity: the prevention, identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children, NICE, viewed 14/10/2017. 2006. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg43 [PubMed]

- Noël P.H., Pugh J.A. Management of overweight and obese adults. Br. Med. J. 2002;325(7367):757. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7367.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordman J., van der Weijden T., van Dulmen S. Communication-related behavior change techniques used in face-to-face lifestyle interventions in primary care: a systematic review of the literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012;89(2):227–244. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.07.006. (November) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M.D.J., Godfrey C., McInerney P., Baldini Soares C., Khalil H., D P. Scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E., Munn Z., editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. (Chapter 11) [Google Scholar]

- Pollak K.I., Coffman C.J., Alexander S.C. Predictors of weight loss communication in primary care encounters. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011;85(3, December):e175–e182. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C., Ziebland S., Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J.O., Di Clemente C.O. Towards a comprehensive model of change. In: Miller W.R., Heather N., editors. Treating addictive behaviours: processes of change. Plenum; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson R., Jepson R., Shepherd A., McInnes R. Recommendations by Queensland GPs to be more physically active: which patients were recommended which activities and what action they took. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 2011;35(6):537–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S., Baker R., Sinfield P., Gunther S., Guo F. Barriers and enablers to managing obesity in general practice: a practical approach for use in implementation activities. Qual. Prim. Care. 2012;20(2):93–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent G., Forrest L., Parker R. Nurse delivered lifestyle interventions in primary health care to treat chronic disease risk factors associated with obesity: a systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2012;13(12):1148–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer G.L., Woodruff R.C., Hotz J., Kegler M.C. A qualitative inquiry about weight counseling practices in community health centers. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014;97(1):82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay L.E., Shobert J.L., Seibert D., Thomas L.E. Adult weight management: translating research and guidelines into practice. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2009;21(4):197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuval K., DiPietro L., Skinner C.S. Sedentary behaviour counselling: the next step in lifestyle counselling in primary care; pilot findings from the Rapid Assessment Disuse Index (RADI) study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014;48(19):1451–1455. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091357. (01 Oct) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag U., Henkel J., Renneberg B., Bockelbrink A., Braun V., Heintze C. Counseling overweight patients: analysis of preventive encounters in primary care. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2010;22(6, Dec):486–492. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzq060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens G.S., Blanken S.E., Greiner K.A., Chumley H.S. Visual prompt poster for promoting patient-physician conversations on weight loss. Ann. Fam. Med. 2008;6(Suppl. 1):S33–S36. doi: 10.1370/afm.780. (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Bogt N.C., Bemelmans W.J., Beltman F.W., Broer J., Smit A.J., van der Meer K. Preventing weight gain by lifestyle intervention in a general practice setting: three-year results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011;171(4):306–313. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute . JBI; Adelaide: 2015. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. [Google Scholar]

- van Dillen S.M., Noordman J., van Dulmen S., Hiddink G.J. Examining the content of weight, nutrition and physical activity advices provided by Dutch practice nurses in primary care: analysis of videotaped consultations. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014;68(1, Jan):50–56. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2013.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring M.E., Roberts M.B., Parker D.R., Eaton C.B. Documentation and management of overweight and obesity in primary care. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2009;22(5):544–552. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.05.080173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation Obesity and overweight, World Health Organisation, viewed 14/10/2017. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/

- Yoong S.L., Carey M.L., Sanson-Fisher R.W., D'Este C.A., Mackenzie L., Boyes A. A cross-sectional study examining Australian general practitioners' identification of overweight and obese patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014;29(2, Feb):328–334. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2637-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]