Abstract

PURPOSE:

According to the Institute of Medicine, high-quality cancer care should include effective communication between clinicians and patients about the risks and benefits, expected response, and impact on quality of life of a recommended therapy. In the delivery of oncology care, the barriers to and facilitators of communication about potential long-term and late effects, post-treatment expectations, and transition to survivorship care have not been fully defined.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

We collected qualitative data through semistructured interviews with medical oncologists and focus groups with breast cancer survivors and applied the Theoretical Domains Framework to systematically analyze and identify the factors that may influence oncologists’ communication with patients with breast cancer about the long-term and late effects of adjuvant therapy.

RESULTS:

Eight key informant interviews with medical oncologists and two focus groups with breast cancer survivors provided data. Both oncologists and patients perceived information on long-term effects as valuable in terms of improved clinical communication but had concerns about the feasibility of inclusion before treatment. They described the current approaches to communication of therapy risks as a brief laundry list that emphasized acute adverse effects and minimized more long-term issues. We describe the barriers to communication about potential long-term effects from the perspectives of both groups.

CONCLUSION:

This study provides insight into oncologists’ communication with patients with breast cancer regarding the potential long-term and late effects of adjuvant chemotherapy and about setting realistic expectations for life after treatment. Opportunities to improve oncologists’ communication about the potential toxicities of therapy, particularly regarding long-term and late effects, should be examined further.

INTRODUCTION

Many cancer survivors have a life expectancy similar to that of their nonaffected peers but suffer additional physical and/or psychosocial sequelae because of their disease and treatments. Long-term effects include symptoms such as fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, and cognitive impairment that begin during treatment and persist after treatment ends.1-4 Late effects, including osteoporosis, heart failure, and secondary leukemia, occur after treatment ends but are causally related to cancer and to treatment exposures.5,6 Despite these known risks, discussions about the potential effects of therapy are generally inadequate, resulting in communication failures, poor symptom management, and missed opportunities to prepare patients for survivorship care and life after treatment.7,8

Effective communication about the potential long-term risks of therapy is imperative for the delivery of high-quality cancer care, as noted in a recent Institute of Medicine report.7 Across the cancer care continuum, clinicians are expected to provide patients and families with understandable information to guide decision making, navigate them through treatments, and set realistic expectations for life after treatment. However, many factors, including treatment complexity,9 misaligned reimbursement incentives,10,11 and inadequate communication skills training,12,13 can impede effective communication in oncology. Furthermore, sufficient data from clinical trials to support complex medical decisions about toxicities, risks of long-term effects, and post-treatment quality of life are not readily available.

Although effective communication about the risks of therapy is essential to quality cancer care, little is known about the practical aspects of when and how to share information on the potential long-term effects with patients in real-world clinical settings. In this study, we initially set out to investigate the feasibility of incorporating this information into treatment planning to tailor treatment decisions on the basis of toxicity risks. We chose breast cancer because of the extensive research on post-treatment outcomes from various adjuvant therapy regimens and because of the availability of clear guidelines on assessing and managing long-term and late effects in this population. We envisioned the development of a treatment decision aid that would integrate information on long-term treatment toxicity with regimen-specific survival outcomes. Early in our study, we learned from both oncologists and patients that this type of tailoring was not feasible because of the time constraints of early consultations, the heavy emphasis on pathway compliance and clinicians’ discomfort with straying from guidelines. Thus, our focus shifted to understanding current practices and identifying the factors, both barriers and facilitators, that influence oncologists’ communication with patients with breast cancer about the potential long-term effects of adjuvant chemotherapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted a qualitative study to explore the factors that influence how oncologists communicate about potential treatment effects in real-world practice settings. The study was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board. All participants provided verbal consent and received a gift card for their participation.

Key Informant Interviews With Medical Oncologists

To explore a range of perspectives, we recruited a convenience sample of medical oncologists from diverse regions across the United States and diverse clinical settings. Approximately one half of the participants were breast cancer specialists, and the remainder had generalist or mixed oncology practices. A medical oncologist (PAG) and a nurse (ERB), both experienced qualitative researchers, conducted all interviews via telephone, with digital audio recording.

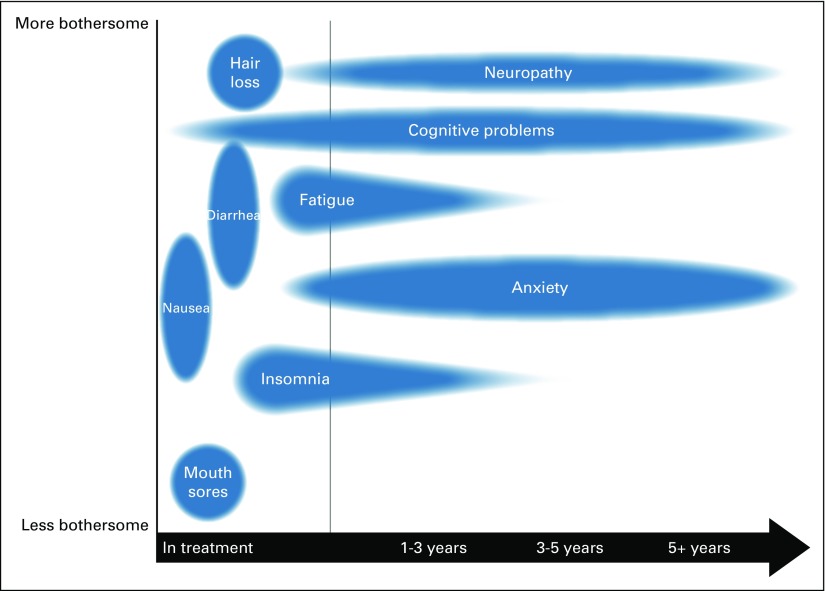

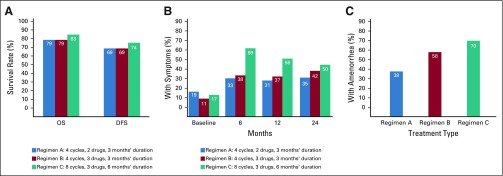

Using a semistructured interview guide, we asked open-ended questions about current practices of communicating the risks of adjuvant chemotherapy and about the barriers to and facilitators of these discussions. Accompanying materials included a conceptual diagram in multiple visual formats of potential treatment effects over time and comparisons of three regimens from a large clinical trial on overall survival, disease-free survival, and risk of long-term toxicities (eg, peripheral neuropathy, amenorrhea, quality of life; Figs 1 and 2). We also inquired about the feasibility of using various resources, including communication tools and graphical materials, in their clinical settings.

Fig 1.

Conceptual diagram of potential treatment effects over time.

Fig 2.

Comparisons of three common adjuvant chemotherapy regimens on (A) overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) at 8 years with regimens A, B, and C; (B) numbness and tingling in the hands and feet; and (C) rates of prolonged amenorrhea at 12 months after start of therapy. Data adapted.14-16

Focus Groups With Breast Cancer Survivors

Breast cancer survivors treated with adjuvant chemotherapy within the past 5 years were recruited from UCLA and community-based organizations to participate in two separate focus groups. The focus groups were cofacilitated by PAG and EFL, an expert on health care decision making and a breast cancer survivor herself, and ERB served as note taker. The focus groups were audio recorded digitally and began with a brief definition of terms (acute, long-term, and late effects of treatment). Participants shared their experiences regarding communication of treatment risks, reflections on information that might have been helpful, and experiences with post-treatment symptoms. We then presented three unnamed regimens with similar survival rates but different toxicity profiles to seek feedback on how this might influence treatment decision making. We also elicited preferences about various information formats (existing decision aid, information sheets, and charts) to assess understandability and perceived value.

After each interview and focus group, the researchers met for an in-depth debriefing in which they discussed key impressions, methodologic issues, and implications for analysis. Data collection was stopped when no new information about barriers and facilitators influencing oncologists’ communication of long-term effects was identified and saturation was reached.

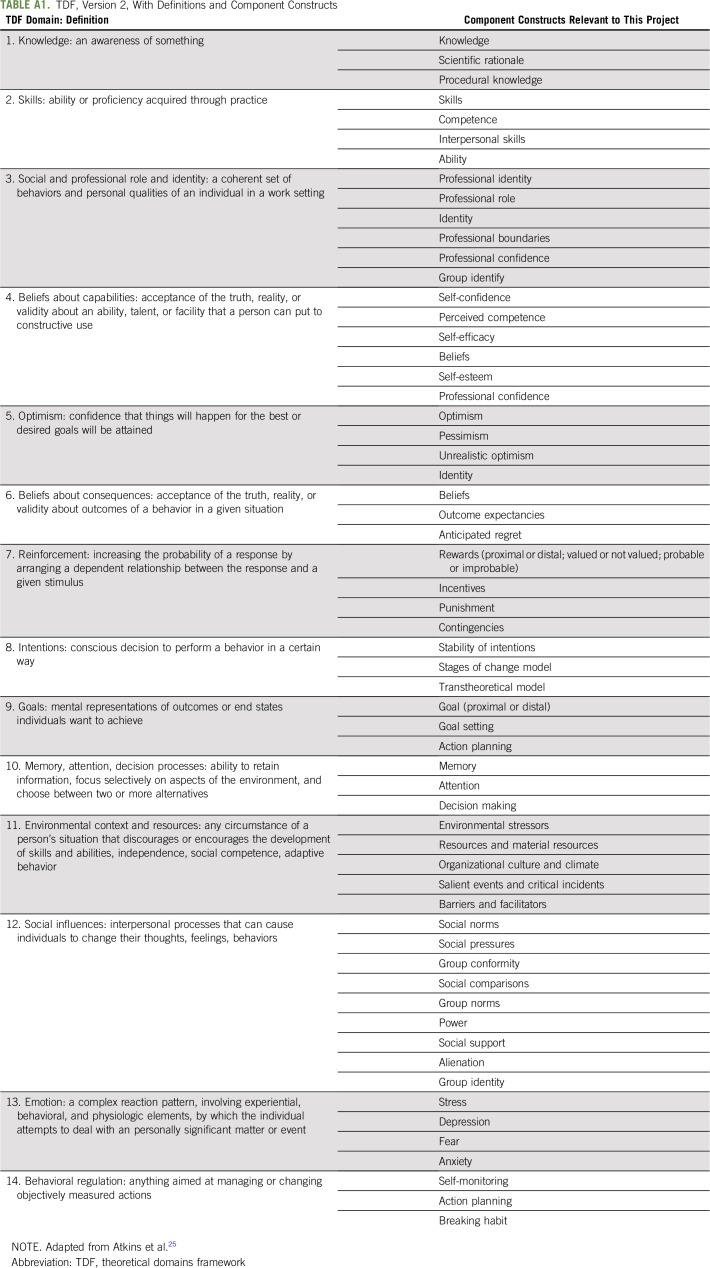

Our analytic approach was guided by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF). Given its applications in implementation research to understanding the behaviors of health care providers,17-22 we selected this framework to identify the barriers to and facilitators of oncologists’ communication about the long-term effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in the realities of today’s clinical settings. The TDF allows researchers to perform a sweeping, systematic assessment of a particular behavior of interest to identify factors that influence that behavior, resulting in a behavioral diagnosis.23,24 The TDF version 2 consists of 14 theoretical domains across individual, group, organizational, and structural levels to consider as potential influences on the target behavior24 (Appendix Table A1, online only).

In this study, the TDF offered a pragmatic analytic framework to assess influences on the behavior of interest: oncologists’ communication about the long-term effects of adjuvant therapy with patients with breast cancer. Using a directed content analysis technique, we followed the steps of TDF-based research described by Atkins et al.25 This process allowed us to review and attribute data to theoretical domains, populate domains with key thematic content, and create data tables. The researchers involved in coding (PAG and ERB) met frequently to discuss challenges and resolve discrepancies, including omitting certain domains that we deemed not relevant or distinct to the target behavior. Regular meetings with another member of the research team (EFL) provided an additional perspective on analytic direction.

RESULTS

Eight medical oncologists participated in key informant interviews that lasted 58 minutes on average. Informants were predominantly female (six of eight), graduated from medical school on average 22.3 years (range, 11 to 44 years) earlier, and consulted on eight to 20 new patients with breast cancer per month. The two focus groups, lasting 105 and 80 minutes, respectively, included nine breast cancer survivors who received treatment at various Southern California institutions.

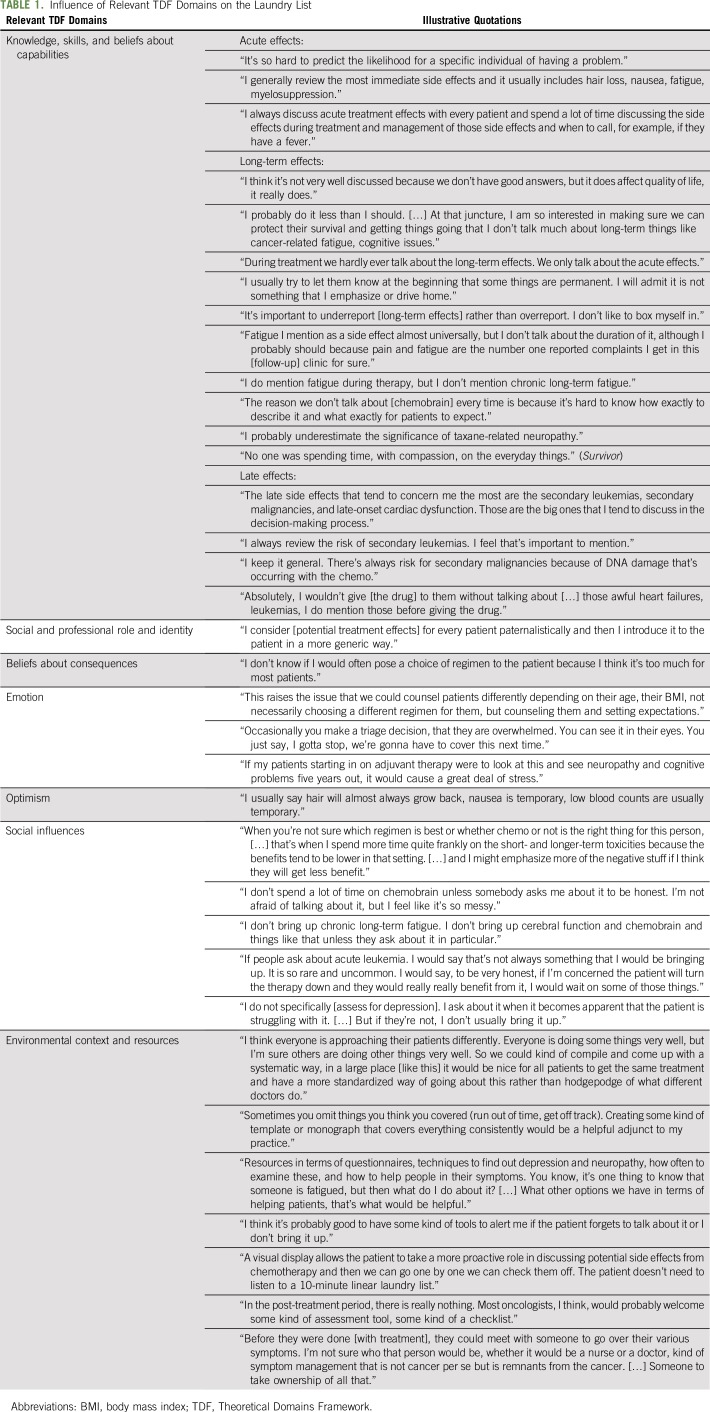

Although tailoring treatment decisions on the basis of potential toxicities did not seem feasible, both oncologists and patients acknowledged the relative absence of this information in current practice settings and underscored its value in strengthening clinical communication. In this analysis, we first describe the current practices related to the communication of the potential risks of adjuvant chemotherapy (the laundry list) and then present the influence of the nine most relevant theoretical domains, organized into four major clusters, on this behavior (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Influence of Relevant TDF Domains on the Laundry List

The Laundry List: Oncologists’ Routine Communication About Potential Risks of Treatment

Nearly all oncologists reported highly routinized communication about potential treatment risks, what several called a laundry list, in which they provided patients with an automatic, almost scripted, rundown of adverse effects before starting a particular regimen. The laundry list typically involved a quick mention rather than an in-depth discussion; as one explained, “I tell them the adverse effects, but I don’t dwell on them.” In addition, the laundry list focused disproportionately on acute effects, such as nausea, hair loss, and fatigue. Focus group participants reiterated that acute effects were listed in a “very nonchalant” way, whereas long-term effects were rarely mentioned at this time.

Most oncologists included, in addition to acute adverse effects, certain rare but serious late effects, such as secondary malignancies and cardiac dysfunction, as part of the laundry list. One oncologist explained, “The big ones should be discussed up front,” whereas another stated that she “wouldn’t give the drug without mentioning them.” They believed it was important to mention these potentially catastrophic events—“the kind you don’t forget in your career”—before initiation of treatment. In some cases, oncologists attributed this urgency to concerns of liability.

Influence of Knowledge, Skills, and Beliefs in Capabilities

The laundry list tended to emphasize acute effects and minimize or neglect long-term effects. Among various explanations for these differences was oncologists’ familiarity with common patient concerns during active treatment. They explained that they had acquired greater knowledge and skills and consequently, more confidence in their ability to discuss acute issues through their experiences monitoring patients receiving chemotherapy. Although oncologists had less experience with managing rare late effects, most felt knowledgeable, skillful, and confident in these discussions with patients, often citing specific percentages to underscore the rarity of these late effects.

In comparison, oncologists’ communication regarding potential long-term effects was vague, less automatic, and avoidant at times. One shared, “These are questions we don’t deal with correctly.” Oncologists also varied in their communication about particular long-term effects compared with others. For example, several participants reported briefly mentioning the possibility of peripheral neuropathy, but only one regularly discussed the impact of treatment on sexual functioning, and none reported routine discussions about potential cognitive issues.

Participants reported that less knowledge, fewer skills, and less confidence about assessing and managing long-term effects contributed to their reluctance to address these issues. For example, when presented with the clinical trial data, many oncologists reported low awareness about the subtle differences in toxicity profiles, such as risk factors for persistent neuropathy or treatment adjustments to avoid amenorrhea. Several oncologists also described the challenge of counseling patients when “not everyone gets everything.”

Influence of Social and Professional Role and Identity, Beliefs About Consequences, and Emotion

Another major barrier to including long-term effects in the laundry list was oncologists’ concern about the emotional consequences of delivering information they perceived to be overwhelming and less urgent. Among the oncologists, there was a strong sense of professional responsibility to filter the complexities of treatment decision making, including nuances related to toxicities (eg, the presence of comorbidities or age-related factors) before presenting recommendations to patients. Only in unusual circumstances did the oncologists elicit treatment preferences and shared decision making from patients, such as in the case of an extreme athlete or a concert pianist.

When communicating about the potential risks of treatment, the oncologists described actively triaging information and prioritizing time-sensitive information to avoid emotional overload. One explained, “Sometimes it’s my job to dilute out what you need to hear today.” This filtering of information was perceived by oncologists to be a way of protecting their patients. Many worried that raising issues that may never manifest could do more harm than good. For example, one oncologist felt that discussing potential long-term effects could precipitate refusal of much-needed treatment, whereas others did not want to worsen patients’ distress levels.

Both oncologists and survivors felt that the emotional intensity and logistical tasks of initial consultations were not conducive to discussions about long-term risks. As one oncologist described, “First visits are so intense. You’re trying to do so many things.” However, they also agreed that this information should be shared at some point before or during treatment, even if conditions were not optimal. One survivor explained, “There is a fine line between ‘TMI,’ too much information, and the relief of anxiety from knowing what to expect.”

Another reason for delaying communication about long-term effects was the shared belief of oncologists and patients that in most cases, this information would not change ultimate treatment decisions. When presented with comparisons of common regimens, participants unequivocally favored a benefit in survival, even when it was marginal and accompanied by higher risks related to symptom burden and quality of life. Therefore, information about long-term effects did not take priority.

Influence of Optimism and Social Influences

Another barrier related to the desire to protect patients from overwhelming or disheartening information was optimism and oncologists’ ability to provide reassurance to patients. Oncologists universally reported a higher inclination to discuss adverse effects that are typically temporary, such as nausea and vomiting, and those with available management strategies (eg, antiemetics). Reassuring patients about long-term effects was difficult because, as one explained, “we don’t have many satisfying solutions.” Because of this, most noted that they typically addressed long-term issues in a reactive manner, “if patients bring it up, if they are experiencing some side effect.” Survivors agreed that oncologists did not mention potential long-term effects “unless I initiated the conversation.”

Discussions about long-term effects relied on patient demand, which falls within the theoretical domain of social influences, and typically emerged only after patients began experiencing symptoms that influenced their quality of life. In several cases, failure to prepare patients for potential long-term effects contributed to distress about symptoms that were unexpected or seemingly unrelated to breast cancer treatment. One recalled asking herself, “Am I crazy?” for months before seeking professional help. Another survivor described the burden of initiating conversations with her oncologist, stating, “Cancer is already stressful, so try to eliminate unnecessary stress.”

Influence of Environmental Context and Resources

The theoretical domain, environmental context, and resources represented another barrier to communication about long-term effects. Both oncologists and survivors were highly receptive to additional resources related to long-term effects, including formal communication tools that could facilitate a systematic approach to these discussions at the point of care. Every oncologist in this sample reported positive previous experiences with communication tools such as Adjuvant Online, Cancer Math, and NHS Predict that enhanced challenging discussions related to prognosis, recurrence, and the role of chemotherapy. Likewise, patients valued resources that presented complex information in a visual format and materials they could review at home at their own pace. However, communication breakdowns occurred when patients were handed packets and “instructed to ‘read this’” without any dialogue or follow-up.

Oncologists described several formats used in practice to convey information about potential treatment effects to patients, such as handouts about adverse effects (from reputable Web sites, linked through the clinical pathway, developed on their own) and chemo classes (led by nurses or physician assistants). However, both groups expressed concern that a lack of unified resources resulted in inconsistent messages among providers. As one oncologist stated, “We could all create our own, but we really need a systematic way.” Many survivors explained how conflicting messages among providers “who were supposed to be a team” increased their anxiety.

There was strong consensus that the laundry list was inadequate for all that chemotherapy entails and that effective communication about the risks of therapy should be systematic and reinforced at multiple time points rather than mentioned briefly amid other overwhelming information. Oncologists also believed that formal communication tools using visual displays would be “better than me running through a list of problems,” normalize long-term issues, result in more cohesive messages among providers, and provide continuity into survivorship care.

DISCUSSION

Conveying accurate, individualized information about potential long-term toxicities of treatment is necessary, given the growing population of cancer survivors. As the landscape continues to shift toward more personalized treatment decisions, effective communication of potential risks will become even more critical. Discussions about the potential risks of therapy are difficult, largely because of the complex nature of risk assessment and the need to discuss a range of potential problems that may or may not occur. Furthermore, conveying this information in a comprehensible manner to patients also poses challenges, especially considering the emotional and hectic nature of early consultations. Previous research suggests that physicians and patients both tend to overestimate the benefits and underestimate the harms of medical procedures.26 Although some work has focused on the delivery of bad news,27,28 less is known about effective communication in routine discussions about treatment risks and likely impact on quality of life.

Another hindrance to communication is that information on long-term treatment-related toxicities is not easily accessible to clinicians. Current clinical trial reporting focuses on short-term toxicities and the most severe (grade 3 or 4) adverse events during treatment. Comprehensive longitudinal data are not collected routinely, resulting in a lack of evidence to guide medical decisions, or, if available, are not often disseminated in a format that is useful to clinicians in their interactions with patients. Our findings indicate that clinicians need information about likely long-term outcomes related to treatment effects to set accurate post-treatment expectations and to proactively assess and manage these issues as part of survivorship care. This may require more extensive data collection in longitudinal studies involving cancer survivors exposed to specific regimens and consolidation of this information into clinically useful resources.

This topic was challenging, even among our selected sample of academic breast oncologists. Nevertheless, clinicians must take a more proactive approach to discussing, assessing, and managing treatment effects. Long-term toxicities can contribute to poorer functional status, quality of life, and morbidity for survivors.15 In one study, nearly one half of long-term survivors had persistent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy symptoms, and symptom severity was associated with poorer function, more disability, and increased fall risk.29 Reluctance to communicate about long-term effects throughout the care trajectory may contribute to unnecessary suffering and poorer outcomes.

Although this report focused on breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy and is limited to the selected nature of our medical oncology informants and discussions with a small number of patients, our findings amplify the recommendations of the Institute of Medicine report by capturing contemporary practice patterns. Our findings across both groups are consistent and provide insight into clinical communication about known therapy risks and suggest potential opportunities to enhance discussions with patients about what they are likely to experience in the post-treatment period. Standardized communication tools may offer an acceptable way to enhance the laundry list by formalizing complex discussions about treatment risks and ensuring that patients receive systematic, understandable information at appropriate times throughout the course of care. Future work that is based on these findings will involve a national survey of medical oncologists, with the ultimate goal of developing tools to improve communication about the long-term effects of treatment and to support a more proactive approach to addressing treatment effects among cancer survivors in real-world clinical settings.30

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under a supplement to award R01CA160427 (PI: Bower, Supplement PI: P.A.G.), by a leadership award from Susan G. Komen (P.A.G.), and by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

TDF, Version 2, With Definitions and Component Constructs

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Eden R. Brauer, Joy Melnikow, Peter M. Ravdin, Patricia A. Ganz

Financial support: Patricia A. Ganz

Administrative support: Peter M. Ravdin, Patricia A. Ganz

Provision of study material or patients: Patricia A. Ganz

Collection and assembly of data: Eden R. Brauer, Patricia A. Ganz

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Communicating Risks of Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer: Getting Beyond the Laundry List

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jop/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Eden R. Brauer

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Pfizer

Elisa F. Long

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Bluebird Bio, Juno Therapeutics

Consulting or Advisory Role: ViiV Healthcare

Patricia A. Ganz

Leadership: Intrinsic LifeSciences (I)

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Xenon Pharma (I), Intrinsic LifeSciences (I), Silarus Therapeutics (I), Teva Neuroscience, Novartis, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Abbott Laboratories

Honoraria: Biogen (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Keryx Biopharmaceuticals (I), Silarus Therapeutics (I), InformedDNA, Vifor Pharma (I), Gilead Sciences (I), La Jolla Pharma (I)

Research Funding: Keryx Biopharmaceuticals (I)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Related to iron metabolism and the anemia of chronic disease (I), Up-to-Date royalties for section editor on survivorship

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Intrinsic LifeSciences (I), Keryx Biopharmaceuticals (I)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bower JE, Ganz PA: Symptoms: Fatigue and cognitive dysfunction. Adv Exp Med Biol 862:53-75, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider BP, Hershman DL, Loprinzi C: Symptoms: Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Adv Exp Med Biol 862:77-87, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bower JE: Behavioral symptoms in patients with breast cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol 26:768-777, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, et al: Physical and psychosocial recovery in the year after primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:1101-1109, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. : American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology breast cancer survivorship care guideline. J Clin Oncol 34:611-635, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenstock AS, Niu J, Giordano SH, et al: Acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome after adjuvant chemotherapy: A population-based study among older breast cancer patients. Cancer 124:899-906, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Institute of Medicine : Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E: From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Institute of Medicine: Patient-Centered Cancer Treatment Planning: Improving the Quality of Oncology Care: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: Toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:755-760, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM: Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff (Millwood) 29:1310-1318, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore PM, Rivera Mercado S, Grez Artigues M, et al. : Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD003751, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Epstein R, Street R Jr: Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD, National Cancer Institute, NIH publication 07-6225, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Swain SM, Jeong JH, Geyer CE Jr, et al: Longer therapy, iatrogenic amenorrhea, and survival in early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 362:2053-2065, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Bandos H, Melnikow J, Rivera DR, et al. : Long-term peripheral neuropathy in breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy: NRG Oncology/NSABP B-30. J Natl Cancer Inst 110: 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ganz PA, Land SR, Geyer CE Jr, et al: Menstrual history and quality-of-life outcomes in women with node-positive breast cancer treated with adjuvant therapy on the NSABP B-30 trial. J Clin Oncol 29:1110-1116, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17. Beenstock J, Sniehotta FF, White M, et al: What helps and hinders midwives in engaging with pregnant women about stopping smoking? A cross-sectional survey of perceived implementation difficulties among midwives in the North East of England. Implement Sci 7:36, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Islam R, Tinmouth AT, Francis JJ, et al: A cross-country comparison of intensive care physicians' beliefs about their transfusion behaviour: A qualitative study using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci 7:93, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19. Murphy K, O'Connor DA, Browning CJ, et al: Understanding diagnosis and management of dementia and guideline implementation in general practice: A qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci 9:31, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20. Patey AM, Islam R, Francis JJ, et al: Anesthesiologists' and surgeons' perceptions about routine pre-operative testing in low-risk patients: Application of the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to identify factors that influence physicians' decisions to order pre-operative tests. Implement Sci 7:52, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.McParlin C, Bell R, Robson SC, et al. : What helps or hinders midwives to implement physical activity guidelines for obese pregnant women? A questionnaire survey using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Midwifery 49:110-116, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schwendicke F, Foster Page LA, Smith LA, et al: To fill or not to fill: A qualitative cross-country study on dentists' decisions in managing non-cavitated proximal caries lesions. Implement Sci 13:54, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23. Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R: The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 6:42, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24. Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S: Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 7:37, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25. Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, et al: A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci 12:77, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Hoffmann TC, Del Mar C: Patients’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: A systematic review. JAMA Intern Med 175:274-286, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bumb M, Keefe J, Miller L, et al. : Breaking bad news: An evidence-based review of communication models for oncology nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs 21:573-580, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. : SPIKES - A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: Application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 5:302-311, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Winters-Stone KM, Horak F, Jacobs PG, et al: Falls, functioning, and disability among women with persistent symptoms of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Clin Oncol 35:2604-2612, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, et al. : Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10:CD001431, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]