Abstract

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a life-threatening disease characterized by recurrent episodes of subcutaneous and mucosal swellings and abdominal cramping. Corticosteroids and antihistamines, which are usually beneficial in histamine-induced acquired angioedema, are not effective in HAE. Therefore, diagnosing HAE correctly is crucial for affected patients. We report a family from Northern Germany with six individuals suffering from recurrent swellings, indicating HAE. Laboratory tests and genetic diagnostics of the genes SERPING1, encoding C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH), and F12, encoding coagulation factor XII, were unremarkable. In three affected and one yet unaffected member of the family, we were then able to identify the c.988A > G (also termed c.1100A > G) mutation in the plasminogen (PLG) gene, which has recently been described in several families with HAE. This mutation leads to a missense mutation with an amino acid exchange p.Lys330Glu in the kringle 3 domain of plasminogen. There was no direct relationship between the earlier described cases with this mutation and the family we report here. In all affected members of the family, the symptoms manifested in adulthood, with swellings of the face, tongue and larynx, including a fatal case of a 19 year-old female individual. The frequency of the attacks was variable, ranging between once per year to once a month. In one individual, we also found decreased serum levels of plasminogen as well as coagulation factor XII. As previously reported in patients with PLG defects, icatibant proved to be very effective in controlling acute attacks, indicating an involvement of bradykinin in the pathogenesis.

To the editor

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a life-threatening disease associated with recurrent episodes of subcutaneous and mucosal swellings and painful abdominal cramping [1]. Anti-allergic drugs, i.e. antihistamines, corticosteroids and epinephrine, which are administered in histamine-mediated angioedema, are not effective in the treatment of HAE. Therefore, a correct and early diagnosis is of utmost importance for affected individuals in order to transfer them to specialized medical centers and to provide effective emergency medications. We here report a family with HAE from Northern Germany, in which we were able to identify the recently described c.988A > G (p.Lys330Glu) mutation in the plasminogen (PLG) gene.

The female index patient (Fig. 1; patient II-2) aged 69 years presented in 2014 with recurrent swellings of tongue and lips, and sometimes also larynx, throat and upper airways. Swelling attacks occurred 1–4 times yearly. Additionally, she suffered from abdominal cramping 2–3 times yearly. The symptoms had started in 2006 at the age of 61 years. Initially, we excluded allergic causes of the recurrent swellings by history and extensive in vivo and in vitro allergy diagnostic testing (skin prick testing and IgE detection). complement factor C4 and C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) concentration as well as function were also unremarkable. The clue for the diagnosis of HAE was then provided by a renewed report of the patient addressing her family history. She reported that her twin brother (patient II-3) has similar symptoms, and his daughter (patient III-7) had died from suffocation due to laryngeal edema at the age of 19 years. Moreover, her two children (patients III-5 and III-6) suffered from similar symptoms. In all cases, the index patient treated swelling attacks immediately with the bradykinin B-2 receptor inhibitor icatibant 30 mg subcutaneously, and swellings responded within 15–20 min after treatment [1, 2]. The son of the index patient (patient III-5), aged 42 years, developed swellings of the lips after he had started an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor for treatment of hypertension. To our knowledge, patient III-5 is the only one of this family who has received an ACE inhibitor. After discontinuation of this treatment, he remained free of symptoms. This patient has a 12 year-old daughter (patient IV-6), who did not experience any symptoms until now, although she was later on also identified as a carrier of the p.Lys330Glu mutation.

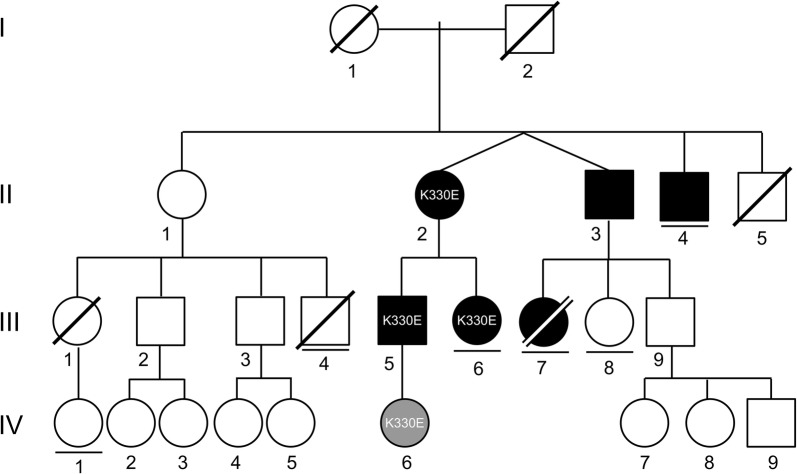

Fig. 1.

Pedigree of a family with hereditary angioedema associated with a plasminogen mutation (HAE-PLG). Symbol description: Circles indicate females, squares males. Black filled symbols indicate affected individuals, gray filled symbols mutation carriers without symptoms. A slash indicates a deceased individual. A horizontal line below a symbol indicates that the (adult) individual has no children. Roman numerals indicate generations, Arabic numerals individuals within a generation. “K330E” in circles or squares indicates individuals who were available for genotyping and showed the plasminogen mutation p.Lys330Glu mutation (K330E). The other affected individuals were so far not available for genotyping

The daughter of the index patient (patient III-6), aged 37 years, reported recurrent swellings of the lips and tongue. Compared to her mother, the frequency of attacks was lower, about 1–2 per year. Rarely, these swellings were also accompanied by abdominal pain. The attacks had started at the age of 20 years. Until now, she never developed a more severe attack with laryngeal edema or dyspnea. For the treatment of acute attacks, icatibant was found to be as effective as in her mother (patient II-2).

In the index patient (patient II-2), genetic analyses for mutations in the SERPING1 (C1-INH) and F12 (coagulation factor XII) genes were negative. For more then 3 years, the diagnosis of HAE was therefore solely based on the family history and the response to treatment with icatibant off-label. At that time, it was not possible to verify the diagnosis, until the first report of a mutation in the PLG gene became available [2].

Using Sanger sequencing of exon 9 of the PLG gene, we then identified the previously described NM_000301.3:c.988A > G (NP_000292.1:p.Lys330Glu) PLG mutation (also termed c.1100A > G; p.Lys311Glu) in four family members (patients II-2, III-5 and III-6 and IV-6). Based on these findings, we were now able to offer accurate genetic counselling and, importantly, predictive genetic analysis for so far unaffected members.

Comparing our family with the recently published patients with HAE associated with a PLG gene mutation (HAE-PLG) [2–6], the age of onset, clinical presentation and frequency of angioedema of all affected members of our family are in line with these previous reports. Patients with HAE-PLG apparently tend to develop first clinical symptoms in adulthood, whereas patients with defects in C1-INH (HAE-C1-INH) usually start with their symptoms during childhood. The clinical picture of recurrent tongue swellings can be considered as indicative for HAE with normal C1-INH (HAE-nC1-INH). Abdominal attacks may also occur, but are less frequent than in HAE-C1-INH [7, 8].

With our family, there are now 24 unrelated families from different countries with HAE-PLG with 105 affected individuals (Table 1) [2, 3]. The number of 89 affected individuals of German origin corresponds to a prevalence of about 1 patient per million inhabitants in Germany, although the number of unrecorded cases must be expected to be higher. In all individuals, the same point mutation in the PLG gene was found, although they were reported to be unrelated. A founder effect was demonstrated in 4 of the families with the PLG gene defect [2]. ACE inhibitors and AT1R inhibitors were reported to induce acute attacks—and sometimes even the first attack—in patients with PLG gene defects [4–6], such as in our patient III-6. Therefore, consideration should be given to whether a PLG defect should be investigated in all cases of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema.

Table 1.

Overview of reported cases with HAE-nC1-INH and the plasminogen mutation PLG:p.Lys330Glu mutation

| Reported families (N) and ethnic origin | Males (N)/females (N) | Mean age of onset (years) | Fatal cases | Treatment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 German | 13/47 | 30.5 | 2 female cases | ICA, TXA | Bork et al. [2] |

| 3 German | 7/15 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Dewald [3] |

| 1 Greece | 3/1 | n.a. | 1 male case | n.a. | Germenis et al. [11] |

| 1 Bulgarian | |||||

| 2 Spanisha | |||||

| 3 French | 2/6 | 6-64 | none | TXA | Belbézier et al. [12] |

| 2 Japanese | 1/3 | 26-94 | none | TXA | Yakushiji H et al. [13] |

| 1 German | 3/4 | ~ 20-60 | 1 female case | ICA | Present report |

All patients shown in this table had the PLG:p.Lys330Glu mutation. Dewald [3] uses a different nomenclature (NM_000301.3:c.1100A > G, p.Lys311Glu) for this mutation. However, the two seemingly different locations correspond to the same amino acid residue A330 (in Uniprot entry P00747-1, GenBank entry NP_000292.1). A311 is the amino acid residue after subtraction of the 19 amino acids long signal peptide (amino acid residues M1-G19). Nucleotide position 1100 and 988 refer to the same position in the sequence of plasminogen transcript 1 (in NBCI RefSeq NM_000301.3). However, 1100 is the position relative to the first nucleotide in the RefSeq entry, while 988 is the position relative to the start codon (nucleotide 113). To follow the more commonly used nomenclature and to adhere to the amino acid and nucleotide positions relative to the coding sequence start as listed in the NCBI database entries, we chose the designation NM_000301.3:c.988A > G (NP_000292.1:p.Lys330Glu)

ICA icatibant, TXA tranexamic acid

aBoth cases carried an additional c.266G > A, p.Arg89Lys mutation in the PLG gene [6]

While treatment guidelines exist for HAE-C1-INH types I and II, there is insufficient evidence to recommend a specific therapy or management strategy for HAE-nC1-INH [1, 2, 7]. Clinical evidence suggests that bradykinin may play a major role in some types of HAE-nC1-INH [1, 2, 9]. In accordance, in our family, icatibant was found to be effective for the treatment of acute attacks. A response to long-term treatment with tranexamic acid 3 g/d was described by Bork et al. [2]. Controlled clinical trials, however, are needed to investigate whether treatment options used for HAE-C1-INH, such as BCX7353, avoralstat, ecallantide, conestat alfa, purified C1-INH and a recombinant antibody inhibiting kallikrein (lanadelumab), are also effective in HAE-nC1-INH [1, 7, 10–13].

Based upon the recent reports of mutations in the PLG and angiopoietin-1 (ANGPT1) genes associated with HAE [2, 3, 9], in addition to the previously known SERPING1 and F12 mutations, a novel classification of HAE was proposed [14]. In general, HAE is here divided into two major groups, HAE-C1-INH and HAE-nC1-INH. HAE-C1-INH is subdivided into (1) reduced plasma concentration of C1-INH and (2) dysfunctional C1-INH with normal plasma concentration. Both variants can be easily detected by measuring C1-INH protein concentration and activity as well as C4. Further, HAE-nC1-INH is now subcategorized into (1) HAE-FXII, (2) HAE-ANGPT1, (3) HAE-PLG and (4) HAE-unknown, according to the respective mutational profile [14]. Identification of patients with HAE-nC1-INH and exclusion of possible differential diagnoses is often challenging and requires careful work-up. It is important to note that gene defects should also be excluded in seemingly unaffected family members, because the swellings can start at nearly any age [2]. The diagnostic workup of angioedema should exclude the possibility of acquired angioedema, i.e. ACE-inhibitor associated angioedema (ACEI-AAE), acquired C1-deficiency angioedema (C1-INH-AAE) and acquired non-histaminergic angioedema (InH-AAE) [15].

HAE-nC1-INH is a life-threatening disease that is, lacking appropriate biomarkers, difficult to diagnose. Therefore, it is of importance to sensitize physicians for this rare and severe, but treatable disease which might be concealed as an ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema or acquired non-histaminergic angioedema.

Authors’ contributions

AR identified the affected family and wrote the manuscript; EGM and UJ wrote the manuscript; LSM performed human genetic analyses and contributed to the manuscript; JS made the pedigree (Fig. 1), discussed the case, performed human genetic analyses and contributed to the manuscript; YH performed human genetic analyses, discussed the case and contributed to the manuscript; IS performed human genetic analyses and contributed to the manuscript; GGK performed human genetic analyses, discussed the case and contributed to the manuscript; DZ discussed the case and contributed to the manuscript; KH discussed the case and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank all people not mentioned here who were involved in patient care and routine laboratory diagnostics.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and material

Does not apply.

Consent for publication

Does not apply. No information that can be used to track back to individuals is revealed.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Does not apply.

Funding

We acknowledge financial support by Land Schleswig–Holstein within the funding programme Open Access Publikationsfonds.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- HAE

hereditary angioedema

- PLG

plasminogen gene

- ANGPT1

angiopoietin 1 gene

- SERPING1

C1-INH gene

- F12

coagulation factor XII gene

- C1-INH

complement factor 1 inhibitor

- HAE-nC1-INH

HAE with normal C1-INH levels or function

- HAE-C1-INH

HAE with with deficient C1-INH

- HAE-PLG

HAE with PLG gene defect

- HAE-ANGPT1

HAE with ANGPT1 gene defect

- HAE-FXII

HAE with F12 gene defect

Contributor Information

Andreas Recke, Email: Andreas.Recke@uksh.de.

Elisabeth G. Massalme, Phone: +49 451 500-41646, Email: Elisabeth.Massalme@uksh.de

Uta Jappe, Email: Uta.Jappe@uksh.de.

Lars Steinmüller-Magin, Email: steinmueller-magin@labor-blessing.de.

Julia Schmidt, Email: julia.schmidt1@med.uni-goettingen.de.

Yorck Hellenbroich, Email: Yorck.Hellenbroich@uksh.de.

Irina Hüning, Email: Irina.Huening@uksh.de.

Gabriele Gillessen-Kaesbach, Email: G.Gillessen@uksh.de.

Detlef Zillikens, Email: Detlef.Zillikens@uksh.de.

Karin Hartmann, Email: Karin.Hartmann@uksh.de.

References

- 1.Maurer M, Magerl M, Ansotegui I, et al. The international WAO/EAACI guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema-the 2017 revision and update. Allergy. 2018 doi: 10.1111/all.13384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bork K, Wulff K, Steinmüller-Magin L, et al. Hereditary angioedema with a mutation in the plasminogen gene. Allergy. 2018;73:442–450. doi: 10.1111/all.13270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewald G. A missense mutation in the plasminogen gene, within the plasminogen kringle 3 domain, in hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;498:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Germenis AE, Loules G, Zamanakou M, et al. On the pathogenicity of the plasminogen K330E mutation for hereditary angioedema. Allergy. 2018;73:1751–1753. doi: 10.1111/all.13324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belbézier A, Hardy G, Marlu R, et al. Plasminogen gene mutation with normal C1 inhibitor hereditary angioedema: three additional French families. Allergy. 2018 doi: 10.1111/all.13543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yakushiji H, Hashimura C, Fukuoka K, et al. A missense mutation of the plasminogen gene in hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor in Japan. Allergy. 2018 doi: 10.1111/all.13550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu SKH, Callum J, Alam A. C1-esterase inhibitor for short-term prophylaxis in a patient with hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor function. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:488–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bork K, Wulff K, Witzke G, Hardt J. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1-INH with versus without specific F12 gene mutations. Allergy. 2015;70:1004–1012. doi: 10.1111/all.12648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bafunno V, Firinu D, D’Apolito M, et al. Mutation of the angiopoietin-1 gene (ANGPT1) associates with a new type of hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerji A, Busse P, Shennak M, et al. Inhibiting plasma kallikrein for hereditary angioedema prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:717–728. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1605767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Longhurst H. Optimum use of acute treatments for hereditary angioedema: evidence-based expert consensus. Front Med. 2017;4:245. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riedl MA, Aygören-Pürsün E, Baker J, et al. Evaluation of avoralstat, an oral kallikrein inhibitor, in a Phase 3 hereditary angioedema prophylaxis trial: the OPuS-2 study. Allergy. 2018;73:1871–1880. doi: 10.1111/all.13466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aygören-Pürsün E, Bygum A, Grivcheva-Panovska V, et al. Oral plasma kallikrein inhibitor for prophylaxis in hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:352–362. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuraw BL. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor: four types and counting. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:884–885. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Firinu D, Loffredo S, Bova M, et al. The role of genetics in the current diagnostic workup of idiopathic non-histaminergic angioedema. Allergy. 2018 doi: 10.1111/all.13667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Does not apply.