Abstract

This essay reviews the discoveries, synthesis, and biological significance of prostaglandins (PGs) and other eicosanoids in insect biology. It presents the most current – and growing – understanding of the insect mechanism of PG biosynthesis, provides an updated treatment of known insect phospholipase A2 (PLA2), and details contemporary findings on the biological roles of PGs and other eicosanoids in insect physiology, including reproduction, fluid secretion, hormone actions in fat body, immunity and eicosanoid signaling and cross-talk in immunity. It completes the essay with a prospectus meant to illuminate research opportunities for interested readers. In more detail, cellular and secretory types of PLA2, similar to those known on the biomedical background, have been identified in insects and their roles in eicosanoid biosynthesis documented. It highlights recent findings showing that eicosanoid biosynthetic pathway in insects is not identical to the solidly established biomedical picture. The relatively low concentrations of arachidonic acid (AA) present in insect phospholipids (PLs) (< 0.1% in some species) indicate that PLA2 may hydrolyze linoleic acid (LA) as a precursor of eicosanoid biosynthesis. The free LA is desaturated and elongated into AA. Unlike vertebrates, AA is not oxidized by cyclooxygenase, but by a specific peroxidase called peroxinectin to produce PGH2, which is then isomerized into cell-specific PGs. In particular, PGE2 synthase recently identified converts PGH2 into PGE2. In the cross-talks with other immune mediators, eicosanoids act as downstream signals because any inhibition of eicosanoid signaling leads to significant immunosuppression. Because host immunosuppression favors pathogens and parasitoids, some entomopathogens evolved a PLA2 inhibitory strategy activity to express their virulence.

Keywords: insects, reproduction, prostaglandins, immunity, hormone signaling, phospholipase A2

Introduction

Prostaglandins (PGs) and other eicosanoids are oxygenated metabolites of three C20 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), 20:3n-6, 20:4n-6, and 20:5n-3. Of the three, conversion of 20:4n-6, arachidonic acid (AA), into eicosanoids is the most widely considered pathway. Although 20:5n-3, eicosapentaenoic acid has been detected in terrestrial animals, it occurs in higher proportions of total phospholipid fatty acids in marine and aquatic invertebrates and vertebrates. In this essay we focus on AA metabolism, which is converted into three broad groups of eicosanoids, PGs, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids and a collection of lipoxygenase (LOX) products, such as hydroxyeicosatrienoic acids and leukotrienes. All three groups of eicosanoids occur in insects.

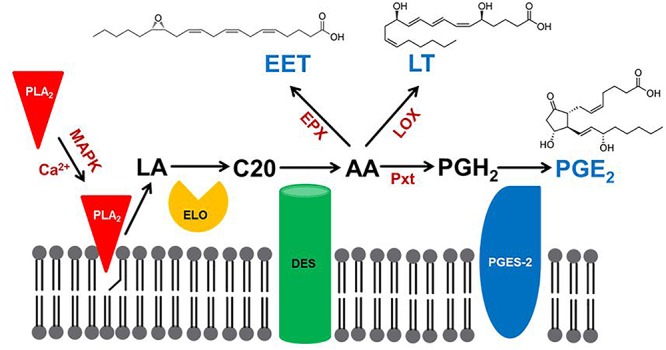

Eicosanoids are generally biosynthesized within cells. They are exported into circulating blood or, in insects, hemolymph, where they may act in autocrine or paracrine mechanisms through cell surface receptors. Here, we review the three major steps of PG biosynthesis in insects. The first step is the release of PUFAs from membrane phospholipids (PLs) by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Figure 1). The second step marks a major departure from the biomedical background, because genes encoding the cyclooxygenase (COX) responsible for converting C20 PUFAs into PGs do not occur in the known insect genomes. In an alternative insect mechanism, a peroxidase (peroxinectin: Pxt) catalyzes the formation of PGH2, with the five-membered ring structure that characterizes PGs (Park et al., 2014). The third step depends on cell-specific enzymes that convert PGH2 into any of several PGs, PGE2 (Ahmed et al., 2018). Here, we treat new discoveries in insect PG biosynthesis.

Figure 1.

A model for eicosanoid biosynthesis in insects. PLA2 activated by calcium or mitogen-activating protein kinase (MAPK) catalyzes the hydrolysis of linoleic acid (LA), which is extended in chain length to C20 fatty acid by a specific elongase (ELO). The C20 precursor is oxidized by desaturases (DES) to produce arachidonic acid (AA; Stanley-Samuelson et al., 1988), which is oxygenated by epoxidase (EPX) to produce epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (EET), by lipoxygenase (LOX) to produce leukotriene (LT) or by a specific peroxinectin (Pxt) to produce prostaglandin H2 (PGH2). PGH2 is then isomerized by PGE2 synthase-2 (PGES-2) to PGE2.

Stanley (2000), a monograph covering all invertebrates, and Stanley and Kim (2014) provide detailed chemical structures and outline eicosanoid biosynthetic pathways. We do not repeat the chemical structures in detail here, with the exception of structures of three major eicosanoid groups to facilitate reading without looking up the structures. The purpose of this review is to integrate the new information into a slightly clearer picture of eicosanoid biosynthesis with current transcriptome-based functional studies. In addition, eicosanoid actions in insects are explained in different physiological processes of reproduction, metabolism, and immunity.

Discovery and Expansion of Known Insect PLA2s

PLA2 was initially discovered from snake venom components (Davidson and Dennis, 1990) and in mammalian systems (Kramer et al., 1989). Later, as non-disulfide bond-containing PLA2s were recognized, it became necessary to classify PLA2s into groups (Dennis, 1994). At least 16 PLA2 groups are now recognized, including five major types: secretory PLA2s (sPLA2s: Groups I–III, V, IX, X, XI, XII, XIII, XIV, and XV), calcium-dependent intracellular PLA2 (cPLA2: Group IV), calcium-independent intracellular PLA2 (iPLA2: Group VI), Lipoprotein-associated PLA2 (LpPLA2: Groups VII and VIII), and adipose phospholipase A2 (AdPLA2: Group XVI) (Vasquez et al., 2018). sPLA2 and LpPLA2 are secretory proteins that act on extracellular membrane lipids, while cPLA2 and iPLA2 catalyze hydrolysis of fatty acids from intracellular PLs. However, the localization of LpPLA2 and AdPLA2 remains unclear.

PLA2 actions include digestion of dietary lipids, remodeling cellular membranes, signal transduction, host immune defenses, and production of various lipid mediators or inactivation of a lipid mediator. There also are non-catalytic PLA2s that act as ligands by binding to receptors or binding proteins (Triggiani et al., 2005). Here, we briefly introduce general characters of five major types of PLA2s before discussing various insect PLA2s.

Classification of PLA2s

sPLA2s are small enzymes (14–18 kDa) with calcium activation (Schaloske and Dennis, 2006). They contain highly conserved amino acid residues and sequences. All organisms express sPLA2, including viruses (Farr et al., 2005), bacteria (Sato and Frank, 2004), plants (Ståhl et al., 1999), and invertebrates (Kishimura et al., 2000), where they exert various actions.

iPLA2, PNPLA9, or iPLA2β, is a calcium-independent PLA2 that acts in membrane remodeling (Ackermann et al., 1994). The longest variant of iPLA2 has a catalytic dyad of Ser/Asp and is comprised of seven ankyrin repeats, a linker region, and a patatin-like α/β hydrolase catalytic domain (Larsson Forsell et al., 1999).

cPLA2 is classified into Group IVA of the PLA2 superfamily (Clark et al., 1991). It is an 85 kDa protein and regulated by intracellular calcium. This enzyme is widely distributed in cells throughout most types of human tissues and consists of two functional domains C2 and α/β hydrolase. Calcium-binding to the C2 domain causes translocation of the protein to a PL membrane (Channon and Leslie, 1990). cPLA2 catalyzes AA release from various PLs and has lysophospholipase and trans-acylase activities (Reynolds et al., 1991).

Platelet-activating factor (PAF) is a potent PL mediator that plays a major role in clotting and inflammatory pathways (Prescott et al., 2000). LpPLA2 catalyzes the hydrolysis of the sn-2 fatty acid in PAF or other lipid substrate and is thus called PAF acetyl hydrolase (PAF-AH; Tjoelker et al., 1995; Stafforini et al., 1997).

Group XVI PLA2 is AdPLA2 abundant in adipose tissue (Duncan et al., 2008) and acts in lipolysis via the production of eicosanoid mediators (Jaworski et al., 2009).

Biochemical and Molecular Characters of Insect PLA2s

Like vertebrates, PLA2 activity acts in lipid digestion, metabolism, secretion, reproduction, and immunity in insects (Stanley, 2006a). Three types of PLA2s are detected in insects (Table 1). In lipid digestion, PLA2 performs two crucial roles by direct hydrolysis of dietary PLs at the sn-2 position to generate nutritionally essential PUFAs and by providing lysophospholipids as insect “bile salts” that solubilize dietary neutral lipids for digestion by other lipases (Stanley, 2006b). The predatory tiger beetle, Cicindella circumpicta expresses a midgut calcium-dependent PLA2 activity (Uscian et al., 1995). Protein fractionation indicated that the enzyme activity was detected in low molecular weight range (about 22 kDa), suggesting a sPLA2. Manduca sexta secretes PLA2 activity from midgut in vitro cultures and catalyzes AA release from PL (Rana et al., 1998; Rana and Stanley, 1999). Larvae of the mosquitoes Aedes aegypti, A. albopictus, and Culex quinquefasciatus express midgut PLA2 activity (Nor Aliza and Stanley, 1998; Abdul Rahim et al., 2018). The peaks of the enzyme activity followed feeding cycles of the mosquito larvae. Similar iPLA2-like activity comes from salivary gland of M. sexta (Tunaz and Stanley, 2004). Burying beetles, Nicrophorus marginatus, inter small mammals as larval food and express a salivary PLA2 to protect the bodies from decomposition during larval development (Rana et al., 1997). Ryu et al. (2003) characterized a gene encoding a D. melanogaster PLA2, which increased interest in insect PLA2s.

Table 1.

Phospholipase A2 activities in insects and their predicted PLA2 types.

| Types | Species | Tissues | Enzyme activities1 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sPLA2 | Cicindella circumpicta | Midgut lumen | • Calcium dependency | Uscian et al., 1995 |

| • AA release from PL | ||||

| • Sensitivity to OOPC inhibitor | ||||

| • <22 kDa size | ||||

| Nicrophorus marginatus | Oral secretion | • Calcium dependency | Rana et al., 1997 | |

| • AA release from PL | ||||

| Cochliomyia hominivorax | Midgut | • Calcium dependency | Nor Aliza et al., 1999 | |

| • AA release from PL | ||||

| • Sensitivity to OOPC inhibitor | ||||

| Manduca sexta | Midgut secretion | •In vitro secretion of PLA2 activity | Rana and Stanley, 1999 | |

| • AA release from PL | ||||

| Drosophila melanogaster | Recombinant protein | • Calcium dependency | Ryu et al., 2003 | |

| • AA release from PL | ||||

| • 138 amino acids | ||||

| Rhodnius prolixus | Plasma | • Calcium dependency | Figueiredo et al., 2008 | |

| •sn-2 ester bond hydrolysis | ||||

| Tribolium castaneum | Recombinant protein | • BPB sensitivity | Shrestha et al., 2010 | |

| •sn-2 ester bond hydrolysis | ||||

| • 173–261 amino acids | ||||

| Spodoptera exigua | Plasma | • BPB sensitivity | Vatanparast et al., 2018 | |

| •sn-2 ester bond hydrolysis | ||||

| iPLA2 | Aedes aegypti | Midgut | • Calcium independency | Nor Aliza and Stanley, 1998 |

| • AA release from PL | ||||

| • Insensitivity to OOPC inhibitor | ||||

| Manduca sexta | Midgut | • Calcium independency | Rana et al., 1998 | |

| • AA release from PL | ||||

| • Insensitivity to OOPC inhibitor | ||||

| Salivary gland | • Calcium independency | Tunaz and Stanley, 2004 | ||

| • AA release from PL | ||||

| • Sensitivity to OOPC inhibitor | ||||

| Rhodnius prolixus | Hemocytes | • Calcium independency | Figueiredo et al., 2008 | |

| •sn-2 ester bond hydrolysis | ||||

| Spodoptera exigua | All tissues | • BEL sensitivity | Sadekuzzaman and Kim, 2017 | |

| •sn-2 ester bond hydrolysis | ||||

| cPLA2 | Rhodnius prolixus | Hemocytes | • Calcium dependency | Figueiredo et al., 2008 |

| •sn-2 ester bond hydrolysis | ||||

| Spodoptera exigua | All tissues | • MAFP sensitivity | Sadekuzzaman and Kim, 2017 | |

| •sn-2 ester bond hydrolysis |

1PL, for phospholipid; AA, for arachidonic acid; BPB, for promophenacyl promide; BEL, for bromoenol lactone; MAFP, for methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphates; OOPC, for oleyloxyethylphosphorylcholine.

Recent work by Sadekuzzaman and Kim (2017) using specific PLA2 inhibitors supports the concept of multiple PLA2 activities in several tissues of larval Spodoptera exigua. Vatanparast et al. (2018) recorded cellular PLA2 activity in S. exigua plasma which is enhanced in response to immune challenge.

All venomous sPLA2s are clustered into the Group III in PLA2s. Similar sPLA2s were predicted from Tribolium castaneum genome (Shrestha et al., 2010). Five sPLA2s encode 173–261 amino acids, in which eight cysteines are conserved. We infer the enzyme is stabilized by formation of four disulfide bonds. All five sPLA2s are expressed in different developmental stages of T. castaneum. Among them, four PLA2s are associated with cellular immune functions. Two sPLA2 genes are encoded and expressed in a hemipteran insect, R. prolixus (Defferrari et al., 2014). These are named as Rhopr-PLA2III and Rhopr-PLA2XII because they have Group III and XII-specific active site sequences of “C-C-R-T-H-D-L-C” and “C-C-N-E-H-D-I-C,” respectively. Both sPLA2 genes are expressed in most nymphal tissues (especially salivary gland) of R. prolixus, in which Rhopr-PLA2XII was more highly expressed than Rhopr-PLA2III.

The first lepidopteran non-venom sPLA2 was identified from S. exigua (Vatanparast et al., 2018), which encodes 194 amino acids containing three domains, a signal peptide, a calcium-binding domain, and a catalytic site. This enzyme clusters with other Group III sPLA2s. Though all insect sPLA2s are clustered in Group III, venomous and non-venomous sPLA2s are distinct in amino acid sequences (Figure 2). Venomous sPLA2s have more cysteine residues than their non-venomous counterparts, which they may need more stable structures to sustain enzyme activity in external environments (Kim et al., 2018).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of venomous and non-venomous sPLA2s. The tree was constructed with Neighbor-joining method using MEGA6.0. Bootstrapping values on branches were obtained with 1,000 repetitions. Amino acid sequences were retrieved from GenBank. Accession numbers are PBC33208.1 for Apis cerana cerana (Acer), XP_006621273.1 for A. dorsata (Ador), XP_003694784.1 for A. florea (Aflo), KYM84159.1 for Atta colombica (Acol), XP_003491197.1 for Bombus impatiens (Bimp), XP_003400956.1 for B. terrestris (Bter), XP_017884585.1 for Ceratina calcarata (Ccal), KYM98685.1 for Cyphomyrmex costatus (Ccos), KOC68767.1 for Habropoda laboriosa (Hlab), XP_003699810.1 for Megachile rotundata (Mrot), KOX79218.1 for Melipona quadrifasciata (Mqua), JAC85837.1 for Panstrongylus megistus (Pmeg), XP_015172342.1 for Polistes dominula (Pdom), XP_014602740.1 for P. canadensis (Pcan), XP_011150082.1 for Harpegnathos saltator (Hsal), XP_008560296.1 for Microplitis demolitor (Mdem), NP_001014501.1 for Drosophila melanogaster (Dmel), XP_021189466.1 for Helicoverpa armigera (Harm), MH061374 for Spodoptera exigua (Sexi), JAI14574.1 for Tabanus bromius (Tbro), KYQ53077.1 for Trachymyrmex zeteki (Tzet), JAS01512.1 for Triatoma infestans (Tinf), NP_001139389.1 for Tribolium castaneum A (TcasA), NP_001139390.1 for TcasB, NP_001139461.1 for TcasC, NP_001139342.1 for TcasD, XP_966735.2 for TcasE, and XP_021915493.1 for Zootermopsis nevadensis (Znev).

As seen in the Tribolium and Spodoptera systems, sPLA2s are likely to mediate immune responses via AA release because RNA interference (RNAi)-treated larvae exhibited significant immunosuppression and AA treatments rescued the immune responses (Shrestha et al., 2010; Vatanparast et al., 2018). An additional sPLA2 immune function may be its direct antibacterial activity in hemolymph. In mammals, Group IIa sPLA2 is one of the most effective antibacterial agents by hydrolyzing the bacterial membrane PLs (Wu et al., 2010).

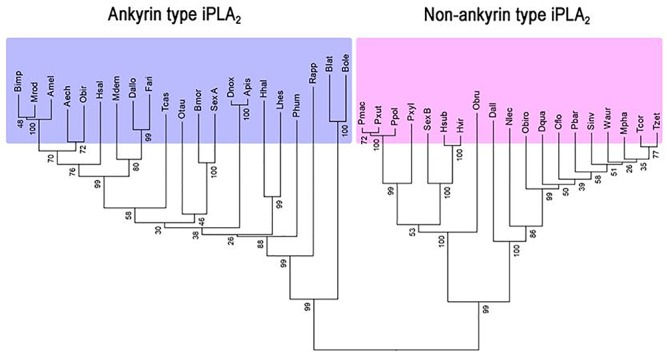

Park et al. (2015a) reported an insect iPLA2 in S. exigua (SeiPLA2A). SeiPLA2A encodes a protein with 816 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 90.5 kDa. SeiPLA2A clusters with Group VIA, which is characterized by multiple ankyrin repeats in the N-terminal region with a consensus lipase motif (“GTSTG”) in the C-terminal region (Winstead et al., 2000). SeiPLA2A was localized in cytoplasm by an immunofluorescence assay. dsSeiPLA2A treatments suppressed gene expression and enzyme activity and led to two pathological phenotypes, loss of cellular immune response and extended larval-to-pupal development. Another iPLA2, denoted SeiPLA2B, was identified in S. exigua (Sadekuzzaman et al., 2017). This enzyme differs from SeiPLA2A in several fundamental ways. SeiPLA2B is a small iPLA2, encoding 336 amino acids with a predicted size of about 36.6 kDa. It lacks ankyrin repeats in the N-terminal region. SeiPLA2B clusters with Group VIF. Both SeiPLA2A and SeiPLA2B are expressed in all developmental stages. The insect iPLA2s are separated into ankyrin and non-ankyrin types (Figure 3). An iPLA2 gene was also identified from another lepidopteran insect, Bombyx mori (Orville Singh et al., 2016) and it is rich in glycine-histidine repeats. This iPLA2 is highly expressed in fat body and RNAi treatments led to severe abnormal development and mortality.

Figure 3.

Two groups of insect iPLA2s. Phylogenetic analysis was performed by the Neighbor-joining method using the software package MEGA 6.0. Bootstrap values (expressed as percentage of 1,000 replications) are shown next to the branches. Amino acid sequences were retrieved from GenBank with accession numbers: XP_011063787.1 for Acromyrmex echinatior (Aech), XP_006565723 for Apis mellifera (Amel), XP_001944054.1 for Acyrthosiphon pisum (Apis), XP_004931589.1 for Bombyx mori (Bmor), JAI19791.1 for Bactrocera latifrons (Blat), XP_014090410.1 for Bactrocera oleae (Bole), XP_003492592.1 for Bombus impatiens (Bimp), XP_011261757.1 for Camponotus floridanus (Cflo), XP_015115454.1 for Diachasma alloeum (Dall), XP_015122829.1 for Diachasma alloeum (Dallo), XP_014488689.1 for Dinoponera quadriceps (Dqua), XP_015368613.1 for Diuraphis noxia (Dnox), JAG76826.1 for Fopius arisanus (Fari), XP_014284806.1 for Halyomorpha halys (Hhal), XP_011144133 for Harpegnathos saltator (Hsal), AGG55019.1 for Heliothis subflexa (Hsub), AGG55005.1 for Heliothis virescens (Hvir), JAQ13976.1 for Lygus hesperus (Lhes), XP_003702751.1 for Megachile rotundata (Mrod), XP_008559240.1 for Microplitis demolitor (Mdem), XP_012538958.1 for Monomorium pharaonis (Mpha), XP_015521797.1 for Neodiprion lecontei (Nlec), XP_022912622.1 for Onthophagus taurus (Otau), XP_011347626.1 for Ooceraea biroi (Obir), XP_011340273.1 for Ooceraea biroi (Obiro), KOB75232.1 for Operophtera brumata (Obru), XP_013147925.1 for Papilio polytes (Ppol), XP_014361526.1 for Papilio machaon (Pmac), XP_002432031.1 for Pediculus humanus corporis (Phum), XP_011641703.1 for Pogonomyrmex barbatus (Pbar), XP_013165315.1 for Papilio xuthus (Pxut), XP_011550190.1 for Plutella xylostella (Pxyl), JAP82800.1 for Rhipicephalus appendiculatus (Rapp), XP_011170109.1 for Solenopsis invicta (Sinv), XP_018367102.1 for Trachymyrmex cornetzi (Tcor), XP_018301493.1 for Trachymyrmex zeteki (Tzet), XP_971204.1 for Tribolium castaneum (Tcas), XP_011693263.1 for Wasmannia auropunctata (Waur), AIN39484.1 for Spodoptera exigua A (SexA), and AQW44791.1 for Spodoptera exigua B (SexB).

A molecular signature of vertebrate cPLA2 is the C2 domain, responsible for calcium-dependent translocation of the enzyme to membranes (Nalefski et al., 1998), which has not been recorded in insects. Variation of PLA2 types were analyzed in S. exigua in different developmental stages and tissues (Sadekuzzaman and Kim, 2017). All developmental stages have significant PLA2 activities. Among larval tissues, hemocytes had higher PLA2 activities than fat body, gut, or epidermis. Different tissues of fifth instar larvae exhibited variation in susceptibility to inhibitors, with epidermal tissue sensitive to cPLA2 inhibitor alone while other tissues are sensitive to all three inhibitor types. The variation of PLA2 types in a one species may offer differential mediation of immune functionalities via eicosanoid signaling. In S. exigua plasmatocytes, intracellular calcium ion is required for cell spreading, which is inhibited by a calcium chelator (Srikanth et al., 2011). In M. sexta, PLA2 activity in the cytosolic fraction was significantly inhibited by treatment with a cPLA2-specific inhibitor, methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphate (Park et al., 2005). We infer insect cPLA2s occur in a novel molecular form.

Some Entomopathogens Target Insect PLA2 for Pathogenicity

Eicosanoids transmit non-self recognition to hemocytes and fat body for systemic immune responses (Stanley and Kim, 2014). Blocking eicosanoid biosynthesis would be a highly effective immunosuppressive strategy in entomopathogen-insect interactions (Kim et al., 2018). This pathogenic strategy is used by some entomopathogens. One example is Trypanosoma rangeli, which is a mammalian parasite transmitted by the bite of triatomid bugs, Rhodnius, and Triatoma (Groot, 1952). The parasites develop within the insect hemolymph and then make their way to the salivary glands for the transmission. In R. prolixus, T. rangeli suppresses hemocyte phagocytosis by suppressing PLA2 activity to inhibit eicosanoid biosynthesis (Figueiredo et al., 2008). Indeed, the addition of AA prevented the parasite infection. Another example is reported in two genera of entomopathogenic bacteria, Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus (Kim et al., 2005). These bacteria are symbionts of entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) in the Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae (Gaugler, 2002; Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2012). After infective juvenile (IJ) nematodes enter host insects, they release symbiotic bacteria into host hemocoel (Forst et al., 1997), which rapidly induces immunosuppression in their hosts (Park and Kim, 2000, 2003). Subsequently, the nematodes develop and reproduce in the insect cadaver (Akhurst, 1980). To induce the host immunosuppression, Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus inhibit PLA2 activity to block eicosanoid biosynthesiss (Kim et al., 2005). In pioneering research with X. nematophila and their symbiont EPN, S. carpocapsae, Park and Kim (2000) injected the bacteria into S. exigua. They explored the hypothesis that bacterial factors act to suppress insect immunity by inhibiting eicosanoid biosynthesis. In their first test of the hypothesis, they injected AA into bacterial-infected larvae, which rescued the insect immune responses. They also injected the PLA2 inhibitor, dexamethasone (DEX) which substantially increased the bacterial virulence. This led to another hypothesis that bacterial secretions inhibit PLA2 activity and all downstream biosynthesis of eicosanoids. The authors used a quantifiable, specific immune function, hemocyte nodule formation (nodulation), to monitor the change in immune response after bacterial challenge. Injection of heat-killed X. nematophila induced about 57 nodules per larva, compared to the same treatment with live X. nematophila, with less than 10 nodules, indicating substantial reduction in the cellular immunity. Injecting AA increased nodulation in the larvae treated with live X. nematophila. Therefore, the authors inferred that two genera of entomopathogenic bacteria, Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus inhibit PLA2 to induce host immunosuppression (Kim et al., 2005). Several commercial sPLA2 preparations from porcine pancreas, honey bee venom, and snake (Naja mossambica) venom were strongly inhibited by an organic extract of the Xenorhabdus culture broth (Park et al., 2004). To test the bacterial extract on insect sPLA2 activity, an immune-associated sPLA2 from T. castaneum was overexpressed, and it was inhibited by the bacterial extract (Shrestha and Kim, 2009). We propose the principle that host nematodes and their symbiotic bacteria suppress insect host immune responses by inhibiting PLA2 activity to optimize their pathogenicity. Ahmed and Kim (2018) supports the idea with their report of a functional correlation between the bacterial virulence and its inhibitory intensity against host PLA2 activity.

Production of multiple PLA2 inhibitors by the bacteria is more nuanced that first thought because the inhibitors are produced in a sequential pattern during bacterial growth and they exert additional inhibitory activities against different immune responses (Eom et al., 2014). They identified seven bacterial secondary metabolites, in which benzylideneacetone and a dipeptide (pro-tyr) are the most potent to inhibit PLA2. Though other five bacterial compounds can inhibit PLA2, they exhibit high inhibitory activities against PO enzyme activity or hemolytic activity to lead to insect immunosuppression (Seo et al., 2012). Because these bacterial secondary metabolites are produced at different bacterial growth phases, we infer that X. nematophila sequentially produces them to sequentially and cooperatively inhibit different steps of insect immune responses, including PLA2 activity.

The entomopathogens also inhibit the direct PLA2-mediated antibacterial activity. In S. exigua, the hemolymph from naïve larvae exhibits high sPLA2 activity, which is further increased in response to bacterial immune challenge (Vatanparast et al., 2018). Thus, we propose that Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus bacteria released from host nematodes inhibit sPLA2 in the hemolymph to protect themselves from antibacterial enzyme activity and suppress insect immunity.

Biological Significance of Eicosanoids in Insects

Eicosanoid and Insect Reproduction

Loher (1979) injected 50 mg PGE2 into virgin female crickets, Teleogryllus commodus, and observed more than fourfold increase in oviposition behavior compared to saline-injected controls. He concluded that PGE2 is an oviposition stimulant, noting that the PG action site was unknown, possibly via direct action on ovaries or muscles involved in oviposition. We will see that neither was correct.

Loher and his colleagues investigated the point in more detail (Loher et al., 1981). They found about 500 pg PGE2 in spermathecae from mated, but not virgin females. Spermathecae contained far less PGE2, about 20 pg/spermatophore. They found that spermatophores and spermathecae from mated, but not virgin, females biosynthesized about 25–35 pmol PGE2/h/gland and smaller amounts of PGF2α. This became the basis of the “enzyme transfer” model, in which a PG biosynthesis activity is transferred to females via spermatophores. Within spermathecae, the transferred enzyme activity converts AA into PGE2, which is released into hemolymph circulation. The precise target of the PGE2 remains unknown, although the PGs may interact with a specific receptor located in the terminal abdominal ganglion, the site of the egg-laying behavioral program.

Lange (1984) reported the transfer of PG synthase activity during mating in Locusta migratoria. Mating led to a fourfold increase in PG biosynthesis, compared to virgins, in spermathecal preparations. Mating, but not PG treatments, led to substantial increases in egg laying. Similarly, Brenner and Bernasconi (1989) recorded the presence of AA and PG biosynthesis in spermatophores and testes of the hematophagous kissing bug, Triatoma infestans. The PG synthase activity is transferred to females during mating because there was PGE2 synthase activity in spermatophores and a low enzyme activity in spermathecae from mated, but not virgin, bugs. The authors speculated the PGs release egg-laying behavior in T. infestans.

PGs release egg-laying behavior in an unknown number of insect species, certainly not all and not even all cricket species. Lee and Loher (1995) reported that treating short-tailed crickets, Anurogryllus muticus with PGs did not influence oviposition behavior. Nonetheless, releasing egg-laying behavior is one of several PG actions in insect reproduction.

Machado et al. (2007) investigated the idea that PG signaling acts in follicle development in silk moth, B. mori. Incubating follicular epithelial cells in the presence of PG biosynthesis inhibitors, aspirin and, separately, indomethacin, blocked transition from follicle development to choriogenesis. They suggested the PGs act in follicle homeostatic physiology, rather than signaling a more specific developmental step.

Tootle and Spradling (2008) used in vitro follicle cultures prepared from D. melanogaster to show that stage 10B egg chamber maturation is inhibited in a dose-related manner by the presence of aspirin or the selective COX-2 inhibitor, NS-398. Treating follicles with PGH2 partially rescued development. Noting that mammalian COXs may have evolved from heme-dependent peroxidases, the authors identified a Drosophila peroxidase, Pxt, which produces PGs in a COX-like manner. They also advanced thinking about PG actions beyond general homeostasis to identification of a specific PG action in the actin cytoskeleton within ovarian follicles (Spracklen et al., 2014).

Tootle and her colleagues found more than 150 genes are expressed in specific stages during the final day of follicle development (Tootle et al., 2011), including known and new genes encoding egg shell proteins. Mutations in the Drosophila Pxt and RNAi treatments lead to mis-timed appearance of transcripts encoding egg shell proteins and defective egg shells.

The biological significance of the work on Drosophila follicle development lies in Drosophila as a model of insect and mammalian molecular processes, which teaches that these molecular processes are very basic biological events. They likely occur in most, if not all, animals. Here, we pose this as a recurrent theme, indicating that some PG actions recorded in insects are fundamental actions in virtually all insects, and likely arthropod, species.

PG Actions in Cockroach Fat Body

Steele and his colleagues investigated the biology of hypertrehalocemic hormones (HTH-I and -II). Their model was composed of disaggregated trophocytes prepared by treating fat bodies isolated from the cockroach, Periplaneta americana, with collagenase. HTH treatments led to increased concentrations of free fatty acids in the trophocytes. Treatments with the LOX inhibitor nordihydroguairaretic acid (NDGA) and COX-inhibitor (indomethacin: INDO) inhibited the release of free fatty acids. The authors inferred the free fatty acids, or their metabolites, act in synthesis and release of trehalose from trophocytes (Ali and Steele, 1997c). They later suggested the increased free fatty acid concentrations are regulated by PLA2 and COX activities (Ali and Steele, 1997a). This is the first recognition that PG and other eicosanoid signaling mediate HTH actions. In direct testing of the idea that PGs act in trehalose synthesis in the isolated trophocytes, they treated separate preparations with HTH, 18:0, 18-1n-9, 18:2n-6, or AA, all of which created similar increases in trehalose synthesis. They also reported that HTH-I treatments led to increased biosynthesis of 20:3n-6 and 20:4n-6, which was blocked by INDO treatments and that treatments with PGF2α, but not PGE2, led to dose-related increases in trehalose efflux from the trophocytes (Ali and Steele, 1997b). The sugar efflux was inhibited by the COX inhibitors, indomethacin and diclofenac. A LOX inhibitor, NDGA and two PLA2 inhibitors, mepacrine and 4′-bromophenacyl bromide (BPB), similarly led to decreased sugar efflux from HTH-I-treated fat body. Again, the authors inferred eicosanoids act in trehalose synthesis and efflux (Ali et al., 1998).

Sun and Steele (2002) reported that HTH-I and –II treatments substantially increased PLA2 activity in membrane-enriched trophocyte preparations. The hormone effect, tested with HTH-II, was dose-dependent up to about 20 pmol/ml. Treating trophocytes with the PLA2 inhibitor, BPB, over the range 0 to 1,000 μM, inhibited PLA2 activity. The fat body PLA2 activity may result from a cytosolic PLA2 because HTH-II treatment led to translocation of the PLA2 activity from the cytosol to the membrane fraction. This indicates Ca2+ is needed for translocation to the membrane and that the PLA2 per se is Ca2+-independent. Their work documents PGs actions in homeostatic hormone signaling.

Eicosanoids and Insect Immunity

Stanley-Samuelson et al. (1991) posed the hypothesis that eicosanoids mediate insect immune responses to bacterial infection. They tested the hypothesis in a series of simple experiments based on treating tobacco hornworms, M. sexta, with an inhibitor of eicosanoid biosynthesis, DEX, and ethanol for controls and separately injecting them with a red-pigmented strain of the bacterium Serratia marcescens. They withdrew hemolymph samples over a 60-min time course, and recovered no bacteria in hemolymph from controls and increasing numbers of bacterial colonies from the DEX-treated insects. The DEX treatments led to dose-dependent decreases in insect survival, which were reversed in insects treated with AA. In light of the short timeframes of their experiments, the authors surmised that eicosanoid metabolism mediates some or all of the early immune responses in insects. These experiments opened a new research corridor on biochemical signaling in insect immunity.

Nodule formation of hemocytes is a cellular immune response to bacterial and other microbial infection (Dunn and Drake, 1983). Miller et al. (1994) reported that PGs and LOX products mediate formation of hemocyte microaggregates and melanotic nodules following S. marcescens infections. Hemocytes migrate toward sites of infection and wounding, where they act in host defense. Merchant et al. (2008) reported that eicosanoids mediate hemocyte migration. Phagocytosis is another cellular immune response by engulfing and secondary killing of invading microbes by phagocytic cells. PGE2 stimulates phagocytosis in the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella (Mandato et al., 1997), the beet armyworm, S. exigua (Shrestha and Kim, 2007) and the bug Rhodnius prolixus (Figueiredo et al., 2008). The secondary killing of engulfed microbes is driven by reactive oxygen species (ROS). Park et al. (2015b) demonstrated that eicosanoids mediate ROS production by activating NADPH-dependent oxidase (NOX), as seen also in vertebrates. We infer that both phases of phagocytosis, the engulfment and secondary killing of bacteria are mediated by eicosanoids. Upon infection by parasitoid eggs or EPNs, insects form several hemocyte layers around the relatively large size of pathogens to prevent oxygen or nutrient supply (Strand, 2008). Carton et al. (2002) showed that the hemocytic encapsulation is mediated by eicosanoids in D. melanogaster exposed to the endoparasitoid wasp, Leptopilina boulardi. Thus, eicosanoids are key mediators of insect cellular immunity (Stanley and Kim, 2014; Kim et al., 2018).

Humoral immune responses in insects include quinone melanization by phenoloxidase (PO) and killing microbes by antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) (Lemaitre and Hoffmann, 2007). In the S. exigua model, PGE2 mediates release of inactive prophenoloxidase (PPO) from specific hemocytes (oenocytoids) into hemolymph by activating oenocytoid cell lysis (OCL) through a specific membrane receptor (Bos et al., 2004) that is expressed solely in oenocytoids in all life stages. Inhibiting expression of the S. exigua PGE2 receptor led to reduced OCL and PO activity (Shrestha and Kim, 2008; Shrestha et al., 2011). PPO is activated into PO by enzymes in hemolymph, which initiates melanization, a key step in both humoral and cellular immune responses, and also in wound-healing response (Bidla et al., 2005). Indeed, a treatment of eicosanoid biosynthesis inhibitor (EBI) significantly suppressed clot formation around wounds of Drosophila larvae (Hyršl et al., 2011). EBI treatment inhibits expression of two AMP genes of B. mori against bacterial challenge (Morishima et al., 1997). In Drosophila, EBI specifically inhibits expression of AMP genes in IMD signal pathway (Yajima et al., 2003). In contrast, eicosanoids may mediate expression of AMP genes in both Toll/IMD pathways in the Oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Li et al., 2017). In the fruit fly, a PLA2 gene is linked with immune responses. Its RNAi treatment led to reduced gene expression of MyD88 and Relish along with suppressive expression of defensin (Toll pathway marker) and diptericin (IMD pathway marker). Similarly, both Toll/IMD signal pathways are controlled by EBI treatment in S. exigua, which led to significant suppression of AMP biosynthesis (Hwang et al., 2013). Thus, eicosanoids also mediate humoral immune responses in insects.

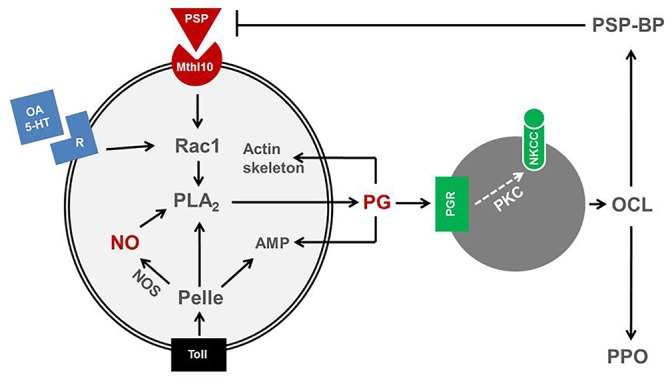

Eicosanoids mediating insect immune responses exhibit functional cross-talks with other immune mediators. Upon non-self recognition, immune mediators propagate the recognition signal to nearby immune effectors, hemocytes and fat body (Gillespie et al., 1997). These immune mediators include cytokines (small protein molecules, 5–20 kDa) such as the insect cytokine, plasmatocyte-spreading peptide (PSP; Clark et al., 1997), biogenic monoamines, nitric oxide (NO), and eicosanoids (Kim et al., 2018). Recent reports indicate that there is substantial cross-talk among immune mediators, in which eicosanoids play a crucial role in mediating most downstream signal (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cross-talk among immune mediators in insects. A cytokine, plasmatocyte-spreading peptide (PSP) binds to its receptor, methuselah 10 (Mthl10) activates a small G protein, Rac1, which is also activated by biogenic monoamines, octopamine (OA) or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT). Rac1 activates PLA2 to produce prostaglandin (PG). PLA2 is also activated by a protein kinase, Pelle, which is activated by Toll receptor. The Toll pathway also induces nitric oxide synthase (NOS) or antimicrobial peptide (AMP) genes. NOS synthesizes nitric oxide (NO) and activates PLA2. The activated PLA2 is involved in PG biosynthesis. PG triggers oenocytoid cell lysis (OCL) and release PSP-binding protein (PSP-BP) and prophenoloxidase (PPO). OCL is induced by sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter (NKCC) via protein kinase C (PKC). PSP-BP facilitates PSP degradation. PG also mediates cytoskeletal rearrangement and AMP production.

Octopamine (OA) and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptophan: 5-HT) are biogenic monoamines that stimulate phagocytosis and nodulation in insects via the small G protein, Rac1 (Baines et al., 1992; Kim et al., 2009; Kim and Kim, 2010) through specific cell surface receptors (Dunphy and Downer, 1994; Qi et al., 2016). Phentolamine (an OA receptor antagonist) and ketanserin (a 5-HT receptor antagonist) suppress cellular immune responses of S. exigua in a competitive manner, and their inhibitory effects are reversed by an addition of AA (Kim et al., 2009). Eicosanoids are the downstream signals of the monoamines probably by increasing intracellular calcium concentrations as seen in the forest tent caterpillar moth, Malacosoma disstria (Jahagirdar et al., 1987) and by subsequently translocating cPLA2 to its substrate PLs (Six and Dennis, 2000). Indeed, a PLA2 of T. castaneum associated with immunity was translocated from cytosol to membrane in response to bacterial challenge (Shrestha et al., 2010).

The insect cytokine, PSP, is expressed as a proPSP in hemocytes and fat body (Clark et al., 1997) and cleaved into a 23 residue PSP that mediates plasmatocyte-spreading behavior in some plasmatocyte subpopulations (Clark et al., 1998). PSP is a member of the ENF peptide family which includes growth-blocking peptide (GBP) and paralytic peptides (PPs; Skinner et al., 1991). PSP induces cell-spreading via an approximately 190 kDa receptor (Clark et al., 2004), identified in Drosophila (Sung et al., 2017) as a Methuselah-like receptor-10 (Mthl10), for GBP. PSP mediates hemocyte-spreading behavior via cross-talk with other immune mediators (Kim et al., 2018). The effects of silencing the gene encoding proPSP were reversed by PSP or AA treatments (Srikanth et al., 2011). The PSP-stimulated hemocyte-spreading was impaired by inhibiting eicosanoid biosynthesis. Activation of eicosanoid biosynthesis by PSP or biogenic monoamines follows receptor-driven activation of Rac1. A Rac1 gene (SeRac1) that acts in cytoskeleton functions (Kim and Kim, 2010) was identified in S. exigua hemocytes (Park et al., 2013). Bacterial challenge up-regulated SeRac1 expression (by >37-fold) and silencing SeRac1 inhibited PSP- or biogenic monoamine-mediated hemocyte-spreading behavior. Injection of PGE2 into SeRac1-silenced larvae rescued the influence of these immune mediators on hemocyte-spreading. PSP and biogenic amines increased PLA2 activity, but not in hemocytes from SeRac1-silenced larvae. Therefore, we inferred that Rac1 transduces PSP and biogenic monoamine signaling by activating PLA2 activity, which leads to eicosanoid biosynthesis. PSP and eicosanoids mediate PPO activation via eicosanoids (Park and Kim, 2014). OCL is required for the release of PPO into plasma, where it is activated (Jiang and Kanost, 2000). In S. exigua, PO is activated by PGs, which mediate OCL to release PPO (Shrestha and Kim, 2008). PSP induces PPO activation in S. exigua (Park and Kim, 2014), suggesting that PG acts downstream of PSP for PPO activation. Injection of PGE2 to the larvae treated with DEX rescued the PPO activation. Park et al. (2013) reported that Rac1 facilitates cross-talk between PSP and eicosanoids. In S. exigua Rac1 activates PLA2 for PG biosynthesis. The PPO induction period by PGE2 treatment was significantly reduced in Rac1-silenced larvae. This reduction of PPO activation by PSP silencing is explained by the absence of endogenous PSP to sustain PLA2 activation for PG biosynthesis. Thus, PSP requires PGE2 as a downstream mediator of PPO activation.

Cross-talk between PSP and eicosanoids acts in down-regulation of PPO activation during later infection stages (Park and Kim, 2014). A specific PSP-binding protein (PSP-BP) terminates the PSP activation of PO because RNAi silencing of PSP-BP extended the PPO activation period (Park and Kim, 2014). This explains how eicosanoids mediate both activation and inactivation of PPO.

NO is a small, membrane-permeable signal molecule that acts in nervous and immune systems in insects and vertebrates (Rivero, 2006). NO is synthesized from L-arginine by NO synthase (NOS), which in mammals exists in three forms (Colasanti et al., 2002). NO mediates immunity in mosquitoes, defending them from malarial parasites (Dimopoulos et al., 1998; Luckhart et al., 1998). In M. sexta, RNAi suppressed NOS expression showed that NO is directly associated with immunity (Eleftherianos et al., 2009). Cross-talk between cytokine and NO signaling induces AMP gene expression in B. mori, where a PSP-like cytokine elevates NO concentration by inducing NOS expression (Ishii et al., 2013). Sadekuzzaman et al. (2018) showed that bacterial injection increased NO concentrations in larval hemocytes and fat body and that silencing a S. exigua nitric oxide synthase (SeNOS) gene suppressed NO concentrations. The silencing of SeNOS expression and, separately, injecting L-NAME (a specific NOS inhibitor) led to reduced PLA2 activities in hemocytes and fat body relative to controls. Injecting a NO donor, S-nitroso-N-acetyl-DL-penicillamine, increased PLA2 activity in a dose-dependent manner. Eicosanoids did not influence NO concentrations in immune challenged larvae, from which it can be inferred that eicosanoid signaling is downstream to NO signaling.

NO treatments alone led to AMP induction because injection of an NO analog, SNAP, without bacterial challenge induced AMP gene expression (Sadekuzzaman and Kim, 2018). There is an additional line of cross-talk between the Toll/IMD pathways and NO signaling because RNAi of Toll or IMD signal components led to reduced levels of NO by inhibiting NOS expression in S. exigua (Sadekuzzaman and Kim, 2018). We infer that Toll/IMD signaling triggers NO signaling, which activates PLA2 to synthesize eicosanoids. In addition, a recent study (Shafeeq et al., 2018) showed that two Toll signal components (MyD88 and Pelle) activate PLA2 in S. exigua, suggesting a direct cross-talk between Toll and eicosanoid signal pathways.

Prospectus

Prostaglandins and other eicosanoids make up a fundamental signaling system in insect biology. We described their actions at the whole animal, cellular and molecular levels of biological organization. These points mark valuable new knowledge on insect biology. So far, the idea that eicosanoids mediate cellular immune reactions has been confirmed in 29 or so insect species from seven orders (Stanley et al., 2012). Broader testing is necessary to develop the general principle that eicosanoids mediate insect immune functions. Similarly, intracellular cross-talk among immune signal moieties has been investigated in one lepidopteran species, S. exigua, which opens questions and hypotheses on the mechanisms of PG actions in insects generally. The overall picture is a broad outline of eicosanoid actions, each of which is an open field of meaningful research.

The eicosanoid signaling system may be a valuable target in applied entomology. Park and Kim (2000) first recognized the pathogenic mechanisms of bacteria in the genera Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus, target insect immune reactions by blocking PLA2s in their insect hosts. Similarly, T. rangeli protects itself from immune actions of its host, R. prolixus (Figueiredo et al., 2008). We infer that host PLA2s are such potent targets that at least two bacterial genera and a eukaryotic parasite in the phylum Euglenozoa evolved mechanisms to down-regulate host immunity by blocking eicosanoid signaling via PLA2s. We identified several genes that were silenced to inhibit insect immunity. We put these genes forward as potential targets that can lead to functional limitations in pest insect immune reactions to microbial and/or parasitic invasions. On the idea that virtually all pest insects become infected during their life cycles in crop plants (Tunaz and Stanley, 2009), targeted inhibition of insect immunity has potential for development into a novel insect management technology.

Author Contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a grant (No. 2017R1A2B3009815) of National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (MSIP), South Korea. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. All programs and services of the U.S. Department of Agriculture are offered on a non-discriminatory basis without regard to race, color, national origin, religion, sex, age, marital status, or handicap.

References

- Abdul Rahim N. A., Othman M., Sabri M., Stanley D. W. (2018). A midgut digestive phospholipase A2 in larval mosquitoes, Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus. Enzyme Res. 2018:9703413. 10.1155/2018/9703413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann E. J., Kempner E. S., Dennis E. A. (1994). Ca2+-independent cytosolic phospholipase A2 from macrophage-like P388D1 cells. Isolation and characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 269 9227–9233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S., Kim Y. (2018). Differential immunosuppression by inhibiting PLA2 affects virulence of Xenorhabdus hominickii and Photorhabdus temperata temperata. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 157 136–146. 10.1016/j.jip.2018.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S., Stanley D., Kim Y. (2018). An insect prostaglandin E2 synthase acts in immunity and reproduction. Front. Physiol. 9:1231. 10.3389/fphys.2018.01231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhurst R. J. (1980). Morphological and functional dimorphism in Xenorhabdus spp. bacteria symbiotically associated with the insect pathogenic nematodes Neoplectana and Heterorhabditis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 121303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali I., Finley C., Steele J. E. (1998). Evidence for the participation of arachidonic acid metabolites in trehalase efflux from hormone activated fat body of the cockroach (Periplaneta americana). J. Insect Physiol. 44 1119–1126. 10.1016/S0022-1910(97)00076-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali I., Steele J. E. (1997a). Evidence that free fatty acids in trophocytes of Periplaneta americana fat body may be regulated by the activity of phospholipase A2 and cyclooxygenase. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 27 681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali I., Steele J. E. (1997b). Fatty acids stimulate trehalose synthesis in trophocytes of the cockroach (Periplaneta americana) fat body. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 108 290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali I., Steele J. E. (1997c). Hypertrehalosemic hormones increase the concentration of free fatty acids in trophocytes of the cockroach (Periplaneta americana) fat body. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 18A, 1225–1231. 9404012 [Google Scholar]

- Baines D., Desantis T., Downer R. G. H. (1992). Octopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine enhance the phagocytic and nodule formation activities of cockroach (Periplaneta americana) haemocytes. J. Insect Physiol. 38 905–914. 10.1016/0022-1910(92)90102-J [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bidla G., Lindgren M., Theopold U., Dushay M. S. (2005). Hemolymph coagulation and phenoloxidase in Drosophila larvae. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 29 669–679. 10.1016/j.dci.2004.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos C. L., Richel D. J., Ritsema T., Peppelenbosch M. P., Versteeg H. H. (2004). Prostanoids and prostanoid receptors in signal transduction. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36 1187–1205. 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner R. R., Bernasconi A. (1989). Prostaglandin biosynthesis in the gonads of the hematophagus [sic] insect Triatoma infestans. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 93B, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Carton Y., Frey F., Stanley D. W., Voss E., Nappi A. (2002). Dexamethasone inhibition of cellular immune response of Drosophila melanogaster against a parasitoid. J. Parasitol. 88 405–407. 10.1645/0022-3395(2002)088[0405:DIOTCI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channon J. Y., Leslie C. C. (1990). A calcium-dependent mechanism for associating a soluble arachidonoyl-hydrolyzing phospholipase A2 with membrane in the macrophage cell line RAW 264.7. J. Biol. Chem. 265 5409–5413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J. D., Lin L. L., Kriz R. W., Ramesha C. S., Sultzman L. A., Lin A. Y., et al. (1991). A novel arachidonic acid-selective cytosolic PLA2 contains a Ca2+-dependent translocation domain with homology to PKC and GAP. Cell 65 1043–1051. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90556-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K., Pech L. L., Strand M. R. (1997). Isolation and identification of a plasmatocyte spreading peptide from hemolymph of the lepidopteran insect Pseudoplusia includens. J. Biol. Chem. 272 23440–23447. 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K. D., Garczynski S. F., Arora A., Crim J. W., Strand M. R. (2004). Specific residues in plasmatocyte-spreading peptide are required for receptor binding and functional antagonism of insect human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279 33246–33252. 10.1074/jbc.M401157200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K. D., Witherell A., Strand M. R. (1998). Plasmatocyte spreading peptide is encoded by an mRNA differentially expressed in tissues of the moth Pseudoplusia includens. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 250 479–485. 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasanti M., Gradoni L., Mattu M., Persichini T., Salvati L., Venturini G., et al. (2002). Molecular bases for the anti-parasitic effect of NO. Int. J. Mol. Med. 9 131–134. 10.3892/ijmm.9.2.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson F. F., Dennis E. A. (1990). Evolutionary relationships and implications for the regulation of phospholipase A2 from snake venom to human secreted forms. J. Mol. Evol. 31 228–238. 10.1007/BF02109500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defferrari M. S., Lee D. H., Fernandes C. L., Orchard I., Carlini C. R. (2014). A phospholipase A2 gene is linked to Jack bean urease toxicity in the Chagas’ disease vector Rhodnius prolixus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1840 396–405. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis E. A. (1994). Diversity of group types, regulation, and function of phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 269 13057–13060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulos G., Seeley D., Wolf A., Kafatos F. C. (1998). Malaria infection of the mosquito Anopheles gambiae activates immune-responsive genes during critical transition stages of the parasite life cycle. EMBO J. 17 6115–6123. 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R. E., Sarkadi-Nagy E., Jaworski K., Ahmadian M., Sul H. S. (2008). Identification and functional characterization of adipose-specific phospholipase A2 (AdPLA2). J. Biol. Chem. 283 25428–25436. 10.1074/jbc.M804146200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn P. E., Drake D. R. (1983). Fate of bacterial injected into naïve and immunized larvae of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 41 77–85. 10.1016/0022-2011(83)90238-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunphy G. B., Downer R. G. H. (1994). Octopamine, a modulator of the haemocytic nodulation response of non-immune Galleria mellonella larvae. J. Insect Physiol. 40 267–272. 10.1016/0022-1910(94)90050-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eleftherianos I., Felföldi G., ffrench-Constant R. H., Reynolds S. E. (2009). Induced nitric oxide synthesis in the gut of Manduca sexta protects against oral infection by the bacterial pathogen Photorhabdus luminescens. Insect Mol. Biol. 18 507–516. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00899.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eom S., Park Y., Kim Y. (2014). Sequential immunosuppressive activities of bacterial secondary metabolites from the entomopathogenic bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophila. J. Microbiol. 52 161–168. 10.1007/s12275-014-3251-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr G. A., Zhang L. G., Tattersal P. (2005). Parvoviral virions deploy a capsid-tethered lipolytic enzyme to breach the endosomal membrane during cell entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 17148–17153. 10.1073/pnas.0508477102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo M. B., Genta F. A., Garcia E. S., Azambuja P. (2008). Lipid mediators and vector infection: Trypanosoma rangeli inhibits Rhodnius prolixus hemocyte phagocytosis by modulation of phospholipase A2 and PAF-acetylhydrolase activities. J. Insect Physiol. 54 1528–1537. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forst S., Dowds B., Boemare N., Stackebrandt E. (1997). Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus spp.: bugs that kill bugs. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51 47–72. 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler R. (2002). Entomopathogenic Nematology. Wallingford: CABI Publishing; 10.1079/9780851995670.0000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie J. P., Kanost M. R., Trenczek T. (1997). Biological mediators of insect immunity. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 42 611–643. 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groot H. (1952). Further observations on Trypanosoma ariarii of Colombia, South America. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1 585–592. 10.4269/ajtmh.1952.1.585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J., Park Y., Lee D., Kim Y. (2013). An entomopathogenic bacterium, Xenorhabdus nematophila, suppresses expression of antimicrobial peptides controlled by Toll and IMD pathways by blocking eicosanoid biosynthesis. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 83 151–169. 10.1002/arch.21103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyršl P., Dobes P., Wang Z., Hauling T., Wilhelmsson C., Theopold U. (2011). Clotting factors and eicosanoids protect against nematode infections. J. Innate Immun. 3 65–70. 10.1159/000320634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K., Adachi T., Hamamoto H., Oonishi T., Kamimura M., Imamura K., et al. (2013). Insect cytokine paralytic peptide activates innate immunity via nitric oxide production in the silkworm Bombyx mori. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 39 147–153. 10.1016/j.dci.2012.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahagirdar A. P., Milton G., Viswanatha T., Downer R. G. H. (1987). Calcium involvement in mediating the action of octopamine and hypertrehalosemic peptides on insect haemocytes. FEBS Lett. 219 83–87. 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81195-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski K., Ahmadian M., Duncan R. E., Sarkadi-Nagy E., Varady K. A., Hellerstein M. K., et al. (2009). AdPLA ablation increases lipolysis and prevents obesity induced by high-fat feeding or leptin deficiency. Nat. Med. 15 159–168. 10.1038/nm.1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Kanost M. R. (2000). The clip-domain family of serine proteinases in arthropods. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 30 95–105. 10.1016/S0965-1748(99)00113-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G., Kim Y. (2010). Up-regulation of circulating hemocyte population in response to bacterial challenge is mediated by octopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine via Rac1 signal in Spodoptera exigua. J. Insect Physiol. 56 559–566. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2009.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Madanagopal N., Lee D., Kim Y. (2009). Octopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine mediate hemocytic phagocytosis and nodule formation via eicosanoids in the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 70 162–176. 10.1002/arch.20286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Ahmed S., Stanley D., An C. (2018). Eicosanoid-mediated immunity in insects. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 83 130–143. 10.1016/j.dci.2017.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Ji D., Cho S., Park Y. (2005). Two groups of entomopathogenic bacteria, Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus, share an inhibitory action against phospholipase A2 to induce host immunodepression. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 89 258–264. 10.1016/j.jip.2005.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimura H., Ojima T., Hayashi K., Nishita K. (2000). cDNA cloning and sequencing of phospholipase A2 from the pyloric ceca of the starfish Asterina pectinifera. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 126 579–586. 10.1016/S0305-0491(00)00227-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer R. M., Hession C., Johansen B., Hayes G., McGray P., Chow E. P., et al. (1989). Structure and properties of a human non-pancreatic phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 264 5768–5775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange A. B. (1984). The transfer of prostaglandin-synthesizing activity during mating in Locusta migratoria. Insect Biochem. 14 551–556. 10.1016/0020-1790(84)90011-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson Forsell P. K., Kennedy B. P., Claesson H. E. (1999). The human calcium-independent phospholipase A2 gene: multiple enzymes with distinct properties from a single gene. Eur. J. Biochem. 262 575–585. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00418.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. J., Loher W. (1995). Changes in the behavior of the female short-tailed cricket, Anurogryllus muticus (DeGeer) (Orthoptera: Gryllidae) following mating. J. Insect Behav. 8 547–562. 10.7717/peerj.4923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B., Hoffmann J. (2007). The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25 697–743. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Dong X., Zheng W., Zhang H. (2017). The PLA2 gene mediates the humoral immune responses in Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel). Dev. Comp. Immunol. 67 293–299. 10.1016/j.dci.2016.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loher W. (1979). The influence of prostaglandin E2 on oviposition in Teleogryllus commodus. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 25 107–109. 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1979.tb02853.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loher W., Ganjian I., Kubo I., Stanley-Samuelson D., Tobe S. S. (1981). Prostaglandins: their role in egg-laying of the cricket Teleogryllus commodus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78 7835–7838. 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckhart S., Vodovotz Y., Cui L., Rosenberg R. (1998). The mosquito Anopheles stephensi limits malaria parasite development with inducible synthesis of nitric oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 5700–5705. 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado E., Swevers L., Sdralia N., Medeiros M. N., Mello F. G., Kostas I. (2007). Prostaglandin signaling and ovarian follicle development in the silkmoth, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37 876–885. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandato C. A., Diehl-Jones W. L., Moore S. J., Downer R. G. H. (1997). The effects of eicosanoid biosynthesis inhibitors on prophenoloxidase activation, phagocytosis and cell spreading in Galleria mellonella. J. Insect Physiol. 43 1–8. 10.1016/S0022-1910(96)00100-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant D., Ertl R. L., Rennard S. I., Stanley D. W., Miller J. S. (2008). Eicosanoids mediate insect hemocyte migration. J. Insect Physiol. 54 215–221. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. S., Nguyen T., Stanley-Samuelson D. W. (1994). Eicosanoids mediate insect nodulation responses to bacterial infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91 12418–12422. 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishima I., Yamano Y., Inoue K., Matsuo N. (1997). Eicosanoids mediate induction of immune genes in the fat body of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. FEBS Lett. 419 83–86. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01418-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalefski E. A., McDonagh T., Somers W., Seehra J., Falke J. J., Clark J. D. (1998). Independent folding and ligand specificity of the C2 calcium-dependent lipid binding domain of cytosolic phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 273 1365–1372. 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nor Aliza A. R., Rana R. L., Skoda S. R., Berkebile D. R., Stanley D. W. (1999). Tissue polyunsaturated fatty acids and a digestive phospholipase A2 in the primary screwworm, Cochliomyia hominivorax. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 29 1029–1038. 10.1016/S0965-1748(99)00080-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nor Aliza A. R., Stanley D. W. (1998). A digestive phospholipase A2 in larval mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 28 561–569. 10.1155/2018/9703413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orville Singh C., Xin H. H., Chen R. T., Wang M. X., Liang S., Lu Y., et al. (2016). BmPLA2 containing conserved domain WD40 affects the metabolic functions of fat body tissue in silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Sci. 23 28–36. 10.1111/1744-7917.12189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Kim Y. (2014). Prostaglandin mediates down-regulation of phenoloxidase activation of Spodoptera exigua via plasmatocyte-spreading peptide-binding protein. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 85 234–247. 10.1002/arch.21156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Stanley D., Kim Y. (2013). Rac1 mediates cytokine-stimulated hemocyte spreading via prostaglandin biosynthesis in the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua. J. Insect Physiol. 59 682–689. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2013.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Stanley D., Kim Y. (2014). Roles of peroxinectin in PGE2-mediated cellular immunity in Spodoptera exigua. PLoS One 9:e105717. 10.1371/journal.pone.0105717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Aliza A. R., Stanley D. (2005). A secretory PLA2 associated with tobacco hornworm hemocyte membrane preparations acts in cellular immune reactions. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 60 105–115. 10.1002/arch.20086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Kim Y. (2000). Eicosanoids rescue Spodoptera exigua infected with Xenorhabdus nematophilus, the symbiotic bacteria to the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema carpocapsae. J. Insect Physiol. 46 1469–1476. 10.1016/S0022-1910(00)00071-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Kim Y. (2003). Xenorhabdus nematophila inhibits p-bromophenacyl bromide (BPB)-sensitive PLA2 of Spodoptera exigua. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 54 134–142. 10.1002/arch.10108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Kim Y., Stanley D. W. (2004). The bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophila inhibits phospholipases A2 from insect, prokaryote and vertebrate sources. Naturwissenschaften 91 371–373. 10.1007/s00114-004-0548-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Sunil K., Rahul K., Stanley D., Kim Y. (2015a). A novel calcium-independent cellular PLA2 acts in insect immunity and larval growth. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 66 13–23. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Stanley D. W., Kim Y. (2015b). Eicosanoids up-regulate production of reactive oxygen species by NADPH-dependent oxidase in Spodoptera exigua phagocytic hemocytes. J. Insect Physiol. 79 63–72. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott S. M., Zimmerman G. A., Stafforini D. M., McIntyre T. M. (2000). Platelet-activating factor and related lipid mediators. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69 419–445. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y. X., Huang J., Li M. Q., Wu Y. S., Xia R. Y., Ye G. Y. (2016). Serotonin modulates insect hemocyte phagocytosis via two different serotonin receptors. eLife 5:e12241. 10.7554/eLife.12241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana R. L., Hoback W. W., Nor Aliza A. R., Bedick J., Stanley D. W. (1997). Pre-oral digestion: a phospholipase A2 associated with oral secretions in adult burying beetles, Nicrophorus marginatus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 118 375–380. 10.1016/S0305-0491(97)00105-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rana R. L., Sarath G., Stanley D. W. (1998). A digestive phospholipase A2 in midgut of tobacco hornworms, Manduca sexta L. J. Insect Physiol. 44 297–303. 10.1016/S0022-1910(97)00118-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana R. L., Stanley D. W. (1999). In vitro secretion of digestive phospholipase A2 by midguts isolated from tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 42 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds L. J., Washburn W. N., Deems R. A., Dennis E. A. (1991). Assay strategies and methods for phospholipases. Methods Enzymol. 197 3–23. 10.1016/0076-6879(91)97129-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivero A. (2006). Nitric oxide: an antiparasitic molecule of invertebrates. Trends Parasitol. 22 219–225. 10.1016/j.pt.2006.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu Y., Oh Y., Yoon J., Cho W., Baek K. (2003). Molecular characterization of a gene encoding the Drosophila melanogaster phospholipase A2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1628 206–210. 10.1016/S0167-4781(03)00143-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadekuzzaman M., Gautam N., Kim Y. (2017). A novel calcium-independent phospholipase A2 and its physiological roles in development and immunity of a lepidopteran insect, Spodoptera exigua. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 77 210–220. 10.1016/j.dci.2017.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadekuzzaman M., Kim Y. (2017). Specific inhibition of Xenorhabdus hominickii, an entomopathogenic bacterium, against different types of host insect phospholipase A2. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 149 95–105. 10.1016/j.jip.2017.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadekuzzaman M., Kim Y. (2018). Nitric oxide mediates antimicrobial peptide gene expression by activating eicosanoid signaling. PLoS One 13:e0193282. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadekuzzaman M., Stanley D., Kim Y. (2018). Nitric oxide mediates insect cellular immunity via phospholipase A2 activation. J. Innate Immun. 10 70–81. 10.1159/000481524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H., Frank D. W. (2004). ExoU is a potent intracellular phospholipase. Mol. Microbiol. 53 1279–1290. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaloske R. H., Dennis E. A. (2006). The phospholipase A2 superfamily and its group numbering system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761 1246–1259. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo S., Lee S., Hong Y., Kim Y. (2012). Phospholipase A2 inhibitors synthesized by two entomopathogenic bacteria, Xenorhabdus nematophila and Photorhabdus temperata subsp. temperata. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 3816–3823. 10.1128/AEM.00301-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafeeq T., Ahmed S., Kim Y. (2018). Toll immune signal activates cellular immune response via eicosanoids. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 84 408–419. 10.1016/j.dci.2018.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro-Ilan D. I., Han R., Dolinksi C. (2012). Entomopathogenic nematode production and application technology. J. Nematol. 44 206–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha S., Kim Y. (2007). An entomopathogenic bacterium, Xenorhabdus nematophila, inhibits hemocyte phagocytosis of Spodoptera exigua by inhibiting phospholipase A2. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 95 64–70. 10.1016/j.jip.2007.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha S., Kim Y. (2008). Eicosanoids mediate prophenoloxidase release from oenocytoids in the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38 99–112. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha S., Kim Y. (2009). Biochemical characteristics of immune-associated phospholipase A2 and its inhibition by an entomopathogenic bacterium, Xenorhabdus nematophila. J. Microbiol. 47 774–782. 10.1007/s12275-009-0145-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha S., Kim Y., Stanley D. (2011). PGE2 induces oenocytoid cell lysis via a G protein-coupled receptor in the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua. J. Insect Physiol. 57 1568–1576. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha S., Park Y., Stanley D., Kim Y. (2010). Genes encoding phospholipase A2 mediate insect nodulation reactions to bacterial challenge. J. Insect Physiol. 56 324–332. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2009.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Six D. A., Dennis E. A. (2000). The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A2 enzymes: classification and characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1488 1–19. 10.1016/S1388-1981(00)00105-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner W. S., Dennis P. A., Li J. P., Summerfelt R. M., Carney R. L., Quistad G. B. (1991). Isolation and identification of paralytic peptides from hemolymph of the lepidopteran insects Manduca sexta, Spodoptera exigua, and Heliothis virescens. J. Biol. Chem. 266 12873–12877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spracklen A. J., Kelpsch D. J., Chen X., Spracklen C. N., Tootle T. L. (2014). Prostaglandins temporally regulate cytoplasmic actin bundle formation during Drosophila oogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 25 397–411. 10.1091/mbc.E13-07-0366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikanth K., Park J., Stanley D. W., Kim Y. (2011). Plasmatocyte-spreading peptide influences hemocyte behavior via eicosanoids. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 78 145–160. 10.1002/arch.20450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafforini D. M., McIntyre T. M., Zimmerman G. A., Prescott S. M. (1997). Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolases. J. Biol. Chem. 272 17895–17898. 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ståhl U., Lee M., Sjödahl S., Archer D., Cellini F., Ek B., et al. (1999). Plant low-molecular-weight phospholipase A2s (PLA2s) are structurally related to the animal secretory PLA2s and are present as a family of isoforms in rice (Oryza sativa). Plant Mol. Biol. 41 481–490. 10.1023/A:1006323405788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley D. (2006a). Prostaglandins and other eicosanoids in insects: biological significance. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 51 25–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley D. (2006b). The non-venom insect phospholipases A2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761 1383–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley D., Haas E., Miller J. (2012). Eicosanoids: exploiting insect immunity to improve biological control programs. Insects 3 492–510. 10.3390/insects3020492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley D. W. (2000). Eicosanoids in Invertebrate Signal Transduction Systems. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley D. W., Kim Y. (2014). Eicosanoid signaling in insects: from discovery to plant protection. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 33 20–63. 10.1080/07352689.2014.847631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley-Samuelson D. W., Jensen E., Nickerson K. W., Tiebel K., Ogg C. L., Howard R. W. (1991). Insect immune response to bacterial infection is mediated by eicosanoids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 1064–1068. 10.1073/pnas.88.3.1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley-Samuelson D. W., Jurenka R. A., Cripps C., Blomquist G. J., de Renobales M. (1988). Fatty acids in insects: composition, metabolism and biological significance. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 9 1–33. 10.1002/arch.940090102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strand M. R. (2008). “Insect hemocytes and their role in immunity,” in Insect Immunology, ed. Beckage N. E. (San Diego, CA: Academic Press; ), 25–47. 10.1016/B978-012373976-6.50004-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D., Steele J. E. (2002). Control of phospholipase A2 activity in cockroach (Periplaneta americana) fat body trophocytes by hypertrehalosemic hormone: the role of calcium. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 32 1133–1142. 10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00049-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung E. J., Ryuda M., Matsumoto H., Uryu O., Ochiai M., Cook M. E., et al. (2017). Cytokine signaling through Drosophila Mthl10 ties lifespan to environmental stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 13786–13791. 10.1073/pnas.1712453115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjoelker L. W., Eberhardt C., Unger J., Trong H. L., Zimmerman G. A., McIntyre T. M., et al. (1995). Plasma platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase is a secreted phospholipase A2 with a catalytic triad. J. Biol. Chem. 270 25481–25487. 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tootle T. L., Spradling A. C. (2008). Drosophila Pxt: a cyclooxygenase-like facilitator of follicle maturation. Development 135 839–847. 10.1242/dev.017590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tootle T. L., Williams D., Hubb A., Frederick R., Spalding A. (2011). Drosophila eggshell production: identification of new genes and coordination by Pxt. PLoS One 6:e19943. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triggiani M., Granata F., Giannattasio G., Marone G. (2005). Secretory phospholipases A2 in inflammatory and allergic diseases: not just enzymes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 116 1000–1006. 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunaz H., Stanley D. (2009). An immunological axis of biocontrol: Infections in field-trapped insects. Naturwissenschaften 96 1115–1119. 10.1007/s00114-009-0572-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunaz H., Stanley D. W. (2004). Phospholipase A2 in salivary glands isolated from tobacco hornworms, Manduca sexta. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 139 27–33. 10.1016/j.cbpc.2004.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uscian J. M., Miller J. S., Sarath G., Stanley-Samuelson D. W. (1995). A digestive phospholipase A2 in the tiger beetle Cicindella circumpicta. J. Insect Physiol. 41 135–141. 10.1016/0022-1910(94)00094-W [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez A. M., Mouchlis V. D., Dennis E. A. (2018). Review of four major distinct types of human phospholipase A2. Adv. Biol. Regul. 67 212–218. 10.1016/j.jbior.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatanparast M., Ahmed S., Herrero S., Kim Y. (2018). A non-venomous sPLA2 of a lepidopteran insect: its physiological functions in development and immunity. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 89 83–92. 10.1016/j.dci.2018.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstead M. V., Balsinde J., Dennis E. A. (2000). Calcium-independent phospholipase A2: structure and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1488 28–39. 10.1016/S1388-1981(00)00107-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Raymond B., Goossens P. L., Njamkepo E., Guiso N., Paya M., et al. (2010). Type-IIA secreted phospholipase A2 is an endogenous antibiotic-like protein of the host. Biochimie 92 583–587. 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yajima M., Tanaka M., Tanahashi N., Kikuchi H., Natori S., Oshima Y., et al. (2003). A newly established in vitro culture using transgenic Drosophila reveals functional coupling between the phospholipase A2-generated fatty acid cascade and lipopolysaccharide-dependent activation of the immune deficiency (imd) pathway in insect immunity. Biochem. J. 371 205–210. 10.1042/bj20021603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]