Abstract

Background

Because conventional prostate biopsy has some limitations, optimal variations of prostate biopsy strategies have emerged to improve the diagnosis rate of prostate cancer. We conducted the systematic review to compare the diagnosis rate and complications of transperineal versus transrectal prostate biopsy.

Main body of the abstract

We searched for online publications published through June 27, 2018, in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure databases. The relative risk and 95% confidence interval were utilized to appraise the diagnosis and complication rate. The condensed relative risk of 11 included studies indicated that transperineal prostate biopsy has the same diagnosis accuracy of transrectal prostate biopsy; however, a significantly lower risk of fever and rectal bleeding was reported for transperineal prostate biopsy. No clue of publication bias could be identified.

Short conclusion

To conclude, this review indicated that transperineal and transrectal prostate biopsy have the same diagnosis accuracy, but the transperineal approach has a lower risk of fever and rectal bleeding. More studies are warranted to confirm these findings and discover a more effective diagnosis method for prostate cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12957-019-1573-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Transperineal, Transrectal, Prostate biopsy, Diagnosis accuracy, Complication

Background

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common cancer in men and has the second highest mortality in the USA [1]. In 2018, approximately 164,690 PCa cases were identified, accounting for almost one in five new cancer diagnoses [1]. Although PCa is common worldwide, the detection method and diagnostic technology has remained controversial. Generally, the following two significant problems about PCa diagnosis must be settled urgently: (a) prostate-specific antigen (PSA) has been widely adopted for screening PCa; however, the conventional threshold for biopsy (4.0 ng/ml) has been associated with a positive predictive value of approximately 20–30% [2, 3]. Thus, a great number of patients underwent an unnecessary prostate biopsy. Are there better biomarkers to help physicians make biopsy decisions? (b) In 1989, Hodge et al. first reported the systematic sextant prostate biopsy to detect PCa by transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) guidance [4]. Since then, TR systematic prostate biopsy has been the most valuable technology for diagnosing PCa [5]. Conventional prostate biopsy does have some limitations including severe complications and high rate of false negatives. Therefore, prostate biopsy strategies including guidance technology, biopsy approaches, and number of cores have emerged to improve the diagnosis rate of PCa [6–11]. An urgent need to identify the most effective and safe way to diagnose PCa still remains.

There are the two principle approaches for the diagnosis of PCa: the transperineal (TP) biopsy and the transrectal (TR) biopsy. The systematic TR prostate biopsy, which is the gold standard for the detection of PCa, has been conducted for decades worldwide. This method, however, reportedly underestimates PCa incidence with a false negative rate up to 49% [12]. Additionally, TR prostate biopsy has been reported to cause severe complications such as rectal bleeding, fever, sepsis, hematuria, and acute urinary retention [13–15]. Due to the high false negative and complication rates of the systematic TR prostate biopsy, the TP approach was introduced to improve the detection rate and safety of prostate biopsy. Though a number of studies were carried out to compare the detection rate and complications of the TP and TR prostate biopsy approaches, the results were controversial regarding the detection rate of the two approaches [16–19]. This controversy was mainly on account of the shortage of sample size and insufficient study design. For instance, the study by Tewes et al. reported cancer detection rates of 39% for TR and 75% for TP [10]; however, the study included only 154 patients and the retrospective study design led to a relatively low comparability of the two cohorts. Therefore, the conclusion of the study was not convincing. Without the limitations of observational studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) represent the gold standard methodology for clinical studies but the results of several RCTs were also inconsistent [20–23].

Meta-analysis could merge the evidence provided by observational studies and RCTs. To this end, we could not only attain the most extensive study population but also minimize the impact of methodological heterogeneity of each study and eliminate low-quality studies [24]. A meta-analysis that offers a higher level of evidence is needed to draw a reliable conclusion about the two biopsy approaches. Previous meta-analyses simply merged observational studies and RCTs together, which brought methodological heterogeneity to the analyses because the study designs and quality assessment methods differed [8]. Aiming to achieve a more precise and convincing conclusion about the detection rates and complications of TP and TR approaches, we separately synthesized observation studies and RCTs after a strict study quality assessment. Additionally, we systematically reviewed all eligible studies to compare the complications of the two biopsy methods.

Materials and methods

Literature search

Our review was conducted on the basis of the PRISMA guidelines [25]. We searched for literatures in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases to cover publications through June 27, 2018 [24, 26]. We utilized a robust and comprehensive retrieval strategy including phrases of two approaches (perineal or transperineal) and (rectal or transrectal). Then, we assessed the obtained papers by looking through their headings and abstracts. Every single potentially relevant study that matched our inclusion requirements was included. The reference documents of the included articles were also completely reviewed to detect any other related study. The language was restricted to English and Chinese. The literature retrieving was performed by two authors solely, and disagreement was settled by consensus.

Inclusion criteria

For the studies contained in our review, all of the subsequent undermentioned criteria should be met: (1) they were designed to be an RCT study, cohort study, or case-control study. (2) The subjects of the studies comprised patients who underwent prostate biopsy. (3) The intervention method included the transperineal approach and the transrectal approach. (4) Apart from the biopsy approach, the number of cores and the guidance method remained the same. (5) The final outcome of the cases included a diagnosis of PCa or complications of the two approaches. (6) The studies provided odds ratios (ORs) or relative risks (RRs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), or adequate evidence to estimate them [26].

Data extraction

The data from the included studies was separately condensed by two authors utilizing a predetermined statistics table and any disagreement was settled by discussion. The crucial aspects were assembled from the included studies: the first author’s last name and country, the publication year, the age of the patients, study design, study population, the number of patients in the two groups, the PSA level and prostate volume of the patients, biopsy methods, and the covariates in the analyses. For respective study, we alternatively extracted the RR or OR which were adjusted for the largest number of confounders [26]. If no RR or OR could be extracted for the whole study, we extracted the original data and calculated the raw RR or OR to estimate the diagnosis accuracy of the two approaches.

Quality assessment

Two authors separately conducted the quality assessment of studies based on the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) applied for observational studies with Cochrane Tool Review Manager 5.3 for RCTs. Observational studies with a < 7 NOS score were defined as low quality and excluded. For RCTs, only one RCT by Udeh et al. was excluded because one in four patients was lost follow-up, representing a high attrition bias [27]. Disagreements between the authors were settled by consensus. If no agreement was achieved, another third expert was invited to resolve the problem.

Statistical methods

As all included studies were cohort studies and RCTs, RR was used to estimate the diagnosis accuracy of TP and TR approaches. If the paper did not contain an adjusted RR and its 95% CI, the initial data was extracted to estimate the raw RR and its 95% CI. We synthesized the RRs and their matching 95% CIs by a random effect model because this model considers the variation both inside the study and between the study [28]. The heterogeneity between the studies was determined by the Q test and I2, as a quantification of heterogeneity, simultaneously calculated to precisely demonstrate the scale of heterogeneity. If significant heterogeneity was detected (I2 > 50%), a systematic review would be conducted instead of a meta-analysis. As the number of patients with complications was zero in some studies, the complications after prostate biopsy were systematically reviewed rather than calculating the overall RR. Publication bias was checked utilizing Begg’s test and Egger’s test, and P < 0.05 was defined to indicate a significant publication bias for the meta-analysis [29, 30]. The stability of the attained results was checked by sensitivity analyses. We deleted a lone study each time to reveal the impact of a particular study to the merged RR.

Results

Literature search

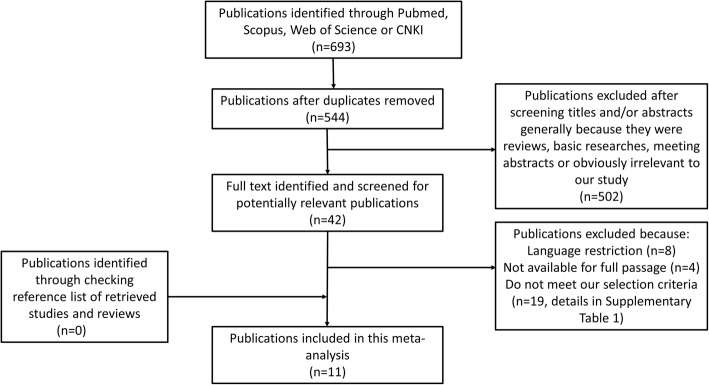

Figure 1 details our retrieval and selection and collection process. Briefly, 544 publications were identified after duplicates were removed. Of these, a large portion of the publications was excluded after scanning the headings and abstracts because they were reviews, fundamental research, meeting abstracts, or extraneous to our study. Next, we identified and carefully reviewed 42 potentially relevant publications of which 31 studies were excluded for language restriction, not available for full passage or not meeting our selection criteria (details in Additional file 1: Table S1). No publications were obtained by trailing through the references of the included articles. Hence, a total of seven cohort studies and four RCTs meeting the inclusion criteria were included in this meta-analysis [13, 16–23, 31, 32].

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study assessment and selection

Study characteristics

We displayed the components of the seven observational studies in Table 1 and four RCTs in Table 2. The study population in the 11 studies was from Italy, China, and Japan. All the included studies were reported between 2002 and 2017. The sample volume fluctuated from 107 [16] to 402 [32]. The total population included in this meta-analysis reached 2569 with 1644 for the TP approach and 1634 for the TR approach (study by Emiliozzi et al., Pepe et al., and Watanabe et al. were performed with a self-control method). More than two potential confounding factors were adjusted in all observational studies.

Table 1.

Study characters of RCTs comparing TP and TR prostate biopsy

| Study | Age | Study population | Patients | PSA level | Prostate volume | Biopsy methods | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP group | TR group | TP group | TR group | TP group | TR group | ||||

| Hara et al., 2008, Japan [21] | 71 | Patients with a PSA level of 4.0 to 20.0 ng/mL from 2003.5 to 2005.10 | 126 | 120 | 8.34 | 8.48 | 33.2 | 36 | Systematic 12-core biopsy |

| Takenaka et al., 2008, Japan [22] | 71 in TP group, 72 in TR group | Consecutive patients with an elevated PSA level (> 4 ng/mL) | 100 | 100 | 17.1 | 19.6 | 34.5 | 37.2 | Systematic 12-core biopsy |

| Cerruto et al., 2014, Italy [23] | 66.5 in TP group, 67.3 in TR group | Consecutive patients with a PSA > 4 ng/mL | 54 | 54 | 15.95 | 12.36 | 56.29 | 61.49 | Systematic 14-core initial prostatic biopsy |

| Guo et al., 2015, China [20] | 67 | Patients between 2012.6 and 2014.8 with a PSA > 4.0 ng/ml | 173 | 166 | 8.81 | 10.48 | 47.2 | 45.9 | Systematic 12-core biopsy |

Abbreviations: TP transperineal, TR transrectal, PSA prostate-specific antigen

Table 2.

Study characters of observational studies comparing TP and TR prostate biopsy

| Study | Age | Study design | Study population | Patients | PSA level | Prostate volume | Biopsy methods | Covariates | NOS score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR group | TP group | TR group | TP group | TR group | TP group | |||||||

| Emiliozzi et al., 2002, Italy [16] | 68 | Cohort study | Patients with a PSA > 4 ng/ml between 2000.4 and 2001.5 | 107 | 8.2 | NA | Six transperineal cores plus six transrectal cores | Self-control | 9 | |||

| Watanabe et al., 2005, Japan [32] | 72.5 | Cohort study | Patients with clinically suspicious prostatic irregularities between 1995.1 and 2001.12 | 402 | 10.3 | NA | Combined 6-core transperineal and 6-core transrectal biopsies | Self-control | 9 | |||

| Abdollah et al., 2010, Italy [19] | 66.3 | Cohort study | Patients who underwent a rebiopsy between 2005.9 and 2008.6 | 140 | 140 | 9.7 | 10 | 65.4 | 62.3 | Ultrasound-guided saturate prostate rebiopsy | Age, PSA, PV, DRE, histologic findings on previous biopsy, the number of previous negative biopsy sets | 8 |

| Tian et al., 2014, China [31] | 63 in TP group, 64 in TR group | Cohort study | Patients who underwent a biopsy between 2007.8 and 2012.7 | 175 | 137 | 1.91–112.52 | 1.45–108.27 | 59.5 | 62.4 | Ultrasound-guided systematic prostate biopsy | Age, PSA, DRE findings, PV | 7 |

| Yuan et al., 2014, China [13] | 66 | Cohort study | Patients who underwent a biopsy between 2009.1 and 2014.1 | 59 | 97 | 21.2 | 19.7 | 33.7 | 35.8 | Ultrasound-guided systematic prostate biopsy | Age, PSA, PV | 7 |

| Pepe et al., 2016, Italy [18] | 61 | Cohort study | Patients persistently suspicious of PCa between 2015.1 and 2016.1 | 200 | 8.6 | NA | mpMRI/TRUS fusion-targeted biopsy | Self-control | 9 | |||

| Franco et al., 2017, Italy [17] | 68 in TP group, 66 in TR group | Cohort study | Random patients that received a prostate biopsy between 2004 and 2014 | 108 | 111 | 7.8 | 6.9 | NA | Ultrasound-guided systematic sextant prostate biopsy | Age, PSA, PSA ratio (F/T), DRE/TRUS findings, LUTS, BPH, biopsy cores, complications | 7 | |

Abbreviations: TP transperineal, TR transrectal, PSA prostate-specific antigen, PV prostate volume, DRE digital rectal examination, PSA ratio F/T free PSA/total PCA, TRUS transrectal ultrasonography, LUTS lower urinary tract syndrome, BPH benign prostate hyperplasia, NA not available

Data obtained from RCTs

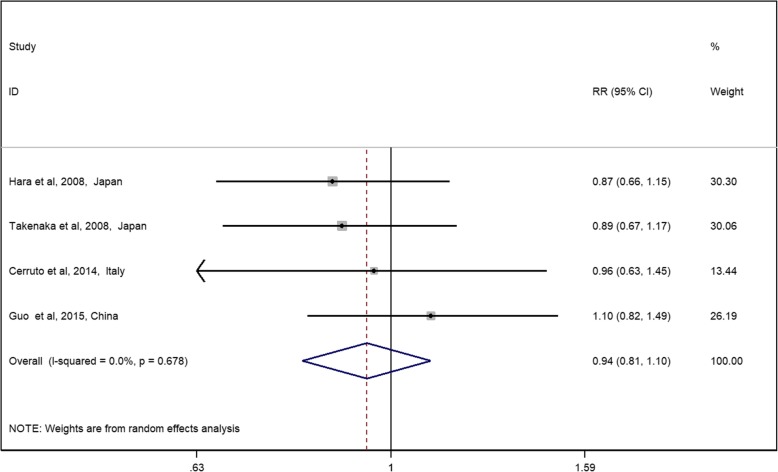

The general RR and its 95% CI showed no significant difference between the TP and TR approaches on diagnosis accuracy (Fig. 2, RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.81–1.10). No significant heterogeneity was detected among these studies with Q = 1.52, I2 = 0%, and P = 0.678. Generally, all RCTs were assessed to have a low risk of bias (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The performance bias was high in all studies because blinding patients with biopsy approach is not possible; however, in this study, performance bias may not affect the accuracy of the results.

Fig. 2.

Relative risks for RCTs assessing the diagnosis rate of the TP approach vs the TR approach. Notes: diamonds represent study-specific relative risks (RRs) or summary relative risks with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Horizontal lines represent 95% CIs. Test for heterogeneity among studies: P = 0.678, I2 = 0.0%

Data obtained from observational studies

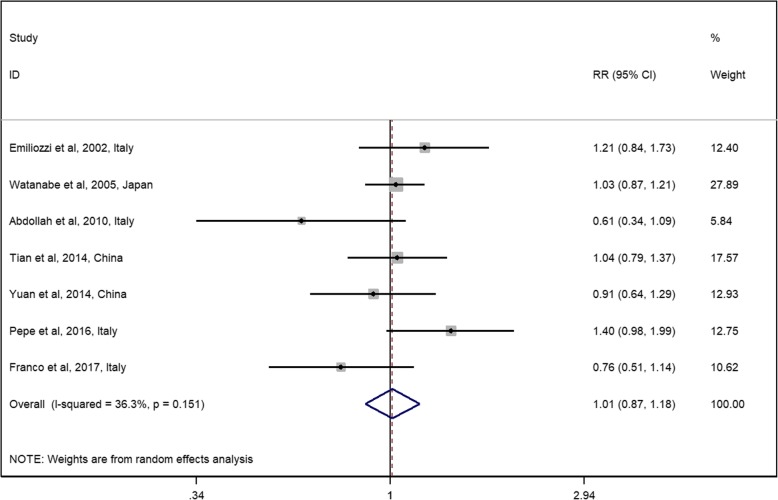

The general RR and its 95% CI showed no significant difference between the TP and TR approaches on diagnosis accuracy (Fig. 3, RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.87–1.18), which is consistent with the results of the RCTs. No significant heterogeneity was detected among the observational studies (Q = 9.42, I2 = 36.3%, and P = 0.151). All included observational studies were assessed to be of high quality (NOS score > 6).

Fig. 3.

Relative risks for observational studies assessing the diagnosis rate of the TP approach vs the TR approach. Notes: diamonds represent study-specific relative risks (RRs) or summary relative risks with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Horizontal lines represent 95% CIs. Test for heterogeneity among studies: P = 0.151, I2 = 36.3%

Comparison of complications of the two approaches

As every RR for each complication was not available, we systematically reviewed all studies comparing the complications of the two approaches. The detailed number of patients with complications is shown in Table 3. In addition, we calculated the RR of each complication using the synthesized data. The TP approach significantly protected the patients from rectal bleeding (RR = 0.02, 95% CI 0.01–0.06) and fever (RR = 0.26, 95% CI 0.14–0.28); however, the TP approach significantly increased patient pain (RR = 1.83, 95% CI 1.27–2.65). No significant difference was found in the acute retention of urine and hematuria between the two approaches.

Table 3.

Comparison of complications of TP and TR prostate biopsy

| Study | Total population | Rectal bleeding | Acute retention of urine | Hematuria | Fever | Pain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | TR | TP | TR | TP | TR | TP | TR | TP | TR | TP | TR | |

| Hara et al., 2007, Japan [21] | 126 | 120 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 2 | NA | |

| Takenaka et al., 2008, Japan [22] | 100 | 100 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 12 | 1 | 2 | NA | |

| Tian et al., 2014, China [31] | 175 | 137 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 11 | 6 | 13 | 16 | 11 |

| Yuan et al., 2014, China [13] | 59 | 97 | 2 | 49 | 4 | 7 | 25 | 53 | 2 | 15 | NA | |

| Cerruto et al., 2014, Italy [23] | 54 | 54 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | |

| Guo et al., 2015, China [20] | 173 | 166 | 0 | 16 | NA | 33 | 37 | 2 | 9 | 58 | 26 | |

| Franco et al., 2017, Italy [17] | 125 | 132 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | |

| Total Number | 812 | 806 | 2 | 81 | 20 | 25 | 102 | 127 | 11 | 42 | 74 | 40 |

| RR (95% CI), TR as the control group | / | 0.02 (0.01–0.06) | 0.89 (0.50–1.59) | 0.79 (0.63–1.01) | 0.26 (0.14–0.48) | 1.83 (1.27–2.65) | ||||||

Abbreviations: TP transperineal, TR transrectal, RR relative risk, NA not available

Sensitivity analysis

To confirm the stability of the merged results, a sensitivity analysis of the integrated RRs was conducted. Based on the random effects model, the general RRs were once again calculated through discarding every single study in the meta-analysis. As a result, the RRs (Additional file 1: Tables S2-S3) persist constantly.

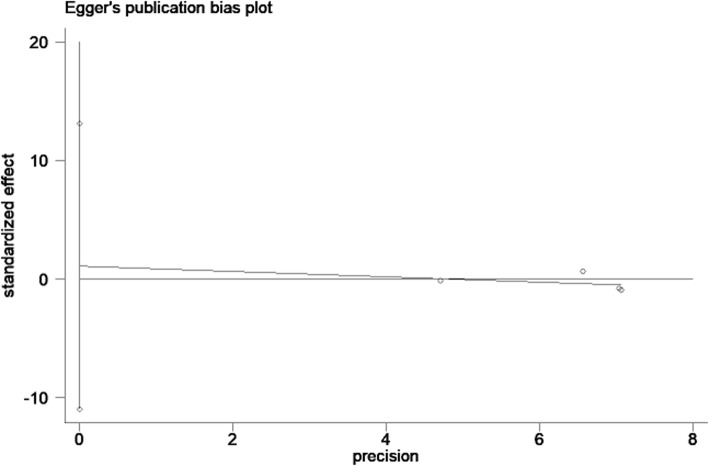

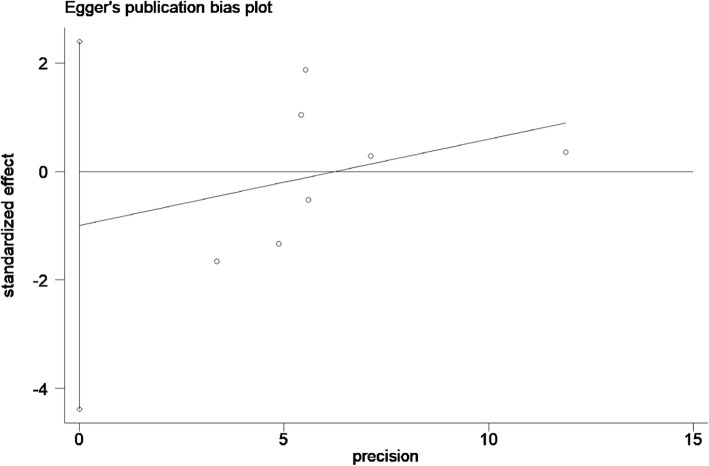

Publication bias

For the RCTs, neither Begg’s test (P = 0.31) nor Egger’s test (Fig. 4, P = 0.74) demonstrated a significant publication bias. Similarly, for the observational studies, publication bias was not significant upon Begg’s test (P = 0.37) or Egger’s test (Fig. 5, P = 0.49).

Fig. 4.

Egger’s publication bias plot for RCTs. Notes: Egger’s regression asymmetry test (P = 0.74). Standardized effect was defined as the odds ratio divided by its standard error. Precision was defined as the inverse of the standard error

Fig. 5.

Egger’s publication bias plot for observational studies. Notes: Egger’s regression asymmetry test (P = 0.49). Standardized effect was defined as the odds ratio divided by its standard error. Precision was defined as the inverse of the standard error

Comparison of MRI/US fusion-guided biopsy with systematic transrectal biopsy

Emerging evidence has shown that multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) as an innovative guidance approach for prostate biopsy increases the detection rate of prostate cancer. Hence, we also reviewed RCT studies comparing MRI/US fusion-guided biopsy and traditional systematic transrectal biopsy. This review was not included in our meta-analysis as our aim was to assess the diagnosis accuracy of transperineal and transrectal biopsy.

Observational studies have limitations in population selection, comparability, and recall bias; however, RCT studies as the gold standard in clinical trial design could significantly avoid known disadvantages. Here, we identified two RCT studies comparing MRI/US fusion-guided transperineal biopsy with systematic transrectal biopsy. Both the studies were assessed to have a low risk of bias. In the study by Baco et al. [33], a total of 175 biopsy-naive patients with suspicion for PCa were randomized into two groups: the MRI group (n = 86) and the control group (n = 89). In the MRI group, the patients underwent an MRI/US fusion-guided 2-core biopsy followed by a traditional 12-core transrectal biopsy. In the cases with negative MRI findings, only a 12-core RB was performed. For the patients in the control group, a 2-core targeted biopsy for abnormal DRE/TRUS and 12-core traditional transrectal biopsy were conducted. The authors revealed a comparable detection rate between the 2-core MRI/US fusion biopsy and traditional 12-core systematic transrectal biopsy, suggesting that the traditional systematic transrectal biopsy could be replaced by the transrectal 2-core MRI/US fusion biopsy.

In the other RCT study by Kasivisvanathan et al. [34], the authors randomized 252 patients in an MRI-targeted group and 248 patients in a standard biopsy group. In the MRI-targeted group, 71 patients did not undergo prostate biopsy because of negative MRI results. The patients in the MRI-targeted group received a 4-core MRI/US fusion biopsy and the patients in the standard biopsy group received a systematic transrectal biopsy. Clinically significant prostate cancer was diagnosed in 38% patients in the MRI-targeted group and 26% patients in the standard biopsy group. The detection rate of the MRI-targeted biopsy is significantly higher than the traditional biopsy.

Discussion

This meta-analysis of seven observational studies and four RCTs indicated that the transperineal prostate biopsy and the transrectal prostate biopsy were similar in diagnosis efficiency. A quantified Q test and I2 test were performed to appraise the intensity of heterogeneity between the studies and showed no significant heterogeneity. We calculated the synthesized RR again using the fixed effect model and the results remained the same (RR = 1.02, 95% CI 0.92–1.14 for observational studies and RR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.81–1.10 for RCTs). The heterogeneity of our study was not significant. Our results remained consistent upon sensitivity analysis, indicating that our results are stable and reliable. Additionally, no evidence of significant publication bias was detected with either Begg’s test or Egger’s test. These results vastly improved the reliability and certainty of our work. Our results were consistent with previous studies [13, 16–23, 31, 32].

Apart from the detection efficiency of prostate biopsy, complications also play an important role in evaluating the safety and value of the biopsy method. Our study revealed that the TP approach significantly decreased the risk of complications including rectal bleeding and fever, while the TR approach significantly protected patients from pain. The two approaches had no significant difference in acute retention of urine and hematuria. Generally, rectal bleeding and hematuria are self-limited complications and patients would obtain relief within several days; however, bleeding can be severe, especially in patients taking anticoagulation drugs such as aspirin. For these patients, anticoagulation drugs should be withdrawn for at least 1 week prior to undergoing prostate biopsy to avoid severe bleeding events. Infections or fever are also common after prostate biopsy. Though enemas are conducted before the transrectal prostate biopsy, the TR approach still had a significantly higher risk of infection than the TP approach. For patients who are prone to infection including those with diabetes, prostatitis, and urinary catheterization, the transperineal prostate biopsy was recommended to avoid sepsis and severe fever after the procedure. Additionally, transperineal prostate biopsy was more comfortable prior to the biopsy because the enema was unnecessary. Most patients would undertake pain after prostate biopsy. Though our study showed that patients that underwent transperineal prostate biopsy were more likely have pain, it is often diminished within several days [31]. Analgesia drugs could be used in moderation for relieving patients’ pain. On the other hand, the TP approach was confirmed to be superior in detecting tumors in the transitional zone and apex of the prostate [16, 22, 23].

Our study evaluating the diagnosis accuracy of the two approaches was more credible because (a) a clear and powerful approach was taken to search the online database to obtain all potentially relevant publications and obedience to PRISMA guidelines and (b) the most comprehensive studies up to date were included in this study. We utilized a strict inclusion criteria constraint in which only RCTs with a low risk of bias and high-quality cohort studies (defined as NOS score > 6) were included. The RCT by Udeh et al. was excluded because 25% of patients were lost follow-up, indicating a high risk of bias [27]. (c) Unlike previous meta-analyses, we separately synthesized observational studies and RCTs because they have different quality assessment methods and simply pooling these results may reduce the reliability of the meta-analysis [8].

At the same time, some limitations should be mentioned. First, only four RCTs, which represented the gold standard methodology of clinical trials, were included in our study. For cohort studies, the selection and comparability problems could not be avoided. We could not solve the potential confounding factors such as free PSA, benign prostate hyperplasia, or other unreported factors in the included cohort studies. Second, though no significant publication bias could be detected, we could not rule out the possibility that our conclusions may be affected by potential publication bias mainly because of the language limitation and the screening approach that only published studies could be included in our study.

MRI/US fusion biopsy as a novelty for prostate biopsy could significantly reduce the biopsy cores. In light of the RCT by Baco et al., the detection efficiency of 2-core MRI/US fusion biopsy was similar with systematic transrectal biopsy [33]; however, the MRI group in Baco’s trial included patients with negative MRI results that underwent only systematic transrectal biopsy. These patients could reduce the detection rate of MRI/US fusion biopsy. In the other RCT by Kasivisvanathan et al. [34], the authors excluded patients with negative MRI results and detected a significantly higher detection rate upon MRI/US fusion biopsy compared to traditional transrectal biopsy. With these findings, we may conclude that along with improving the biopsy accuracy, MRI might also free patients from an unnecessary prostate biopsy [33–36]. This result was in accordance with our previous review for observational studies in this field [37].

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study indicated that transperineal prostate biopsy has the same diagnosis accuracy of transrectal prostate biopsy; however, transperineal prostate biopsy is safer and more valuable because it poses a significantly lower risk of infection and rectal bleeding. Despite the increased risk of pain after TP biopsy, we recommend that doctors should perform transperineal prostate biopsy if possible. An MRI should be conducted before a biopsy to avoid an unnecessary prostate biopsy. To the best of our knowledge, a 2–4-core MRI/US fusion-targeted transperineal biopsy may be the best method for prostate biopsy. More studies should be conducted to confirm findings and discover a more effective diagnosis method for prostate cancer.

Additional file

Table S1. Details of excluded studies. Table S2. Sensitivity analysis of RCTs. Table S3. Sensitivity analysis of observational studies. Figure S1. Risk of bias assessment of RCTs. (ZIP 605 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81472375 And No. 81802564) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Grant (2018 M632489).

Availability of data and materials

All analyses were based on previous published studies and could be searched in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure.

Abbreviations

- BPH

Benign prostate hyperplasia

- CI

Confidence interval

- DRE

Digital rectal examination

- LUTS

Lower urinary tract syndrome

- mpMRI

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging

- NA

Not available

- NOS

Newcastle–Ottawa scale

- OR

Odds ratio

- PCa

Prostate cancer

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- PSA ratio F/T

Free PSA/total PSA

- PSA

Prostate-specific antigen

- PV

Prostate volume

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- RR

Relative risk

- TP

Transperineal

- TR

Transrectal

- TRUS

Transrectal ultrasonography

- US

Ultrasonography

Authors’ contributions

JX extracted and analyzed the data of the study. HY searched the online database, extracted the data, and was a major contributor in the writing of the manuscript. JL searched the online database. XW and HC checked the data and participated in the discussion part. XZ was the expert to resolve disagreements. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All analyses were based on previous published studies thus no ethical approval and patient consent are required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jianjian Xiang, Email: xiangjianjianzju@163.com.

Huaqing Yan, Email: yanhuaqing@zju.edu.cn.

Jiangfeng Li, Email: lijf@zju.edu.cn.

Xiao Wang, Email: zjuwangxiao@zju.edu.cn.

Hong Chen, Email: 10918090@zju.edu.cn.

Xiangyi Zheng, Email: zheng_xy@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayes JH, Barry MJ. Screening for prostate cancer with the prostate-specific antigen test: a review of current evidence. Jama. 2014;311:1143–1149. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee A, Chia SJ. Contemporary outcomes in the detection of prostate cancer using transrectal ultrasound-guided 12-core biopsy in Singaporean men with elevated prostate specific antigen and/or abnormal digital rectal examination. Asian J Urol. 2015;2:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodge KK, McNeal JE, Terris MK, Stamey TA. Random systematic versus directed ultrasound guided transrectal core biopsies of the prostate. J Urol. 1989;142:71–74. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)38664-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2017;71:618–629. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Gao X, Yang Q, et al. Three-dimensional printing technique assisted cognitive fusion in targeted prostate biopsy. Asian J Urol. 2015;2:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JW, Lee HY, Hong SJ, Chung BH. Can a 12 core prostate biopsy increase the detection rate of prostate cancer versus 6 core?: a prospective randomized study in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:671–675. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue J, Qin Z, Cai H, et al. Comparison between transrectal and transperineal prostate biopsy for detection of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:23322–23336. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bor R, Farkas K, Balint A, et al. Prospective comparison of magnetic resonance imaging, transrectal and transperineal sonography, and surgical findings in complicated perianal Crohn disease. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:2367–2372. doi: 10.7863/ultra.15.09043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tewes S, Peters I, Tiemeyer A, et al. Evaluation of MRI/ultrasound fusion-guided prostate biopsy using transrectal and transperineal approaches. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:2176471. doi: 10.1155/2017/2176471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen K, Tay KJ, Law YM, et al. Outcomes of combination MRI-targeted and transperineal template biopsy in restaging low-risk prostate cancer for active surveillance. Asian J Urol. 2018;5:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sazuka T, Imamoto T, Namekawa T, et al. Analysis of preoperative detection for apex prostate cancer by transrectal biopsy. Prostate Cancer. 2013;2013:705865. doi: 10.1155/2013/705865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan L-r, Zhang C-g, Lu L-x, et al. Comparison of ultrasound-guided transrectal and transperineal prostate biopsies in clinical application. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2014;20:1004–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller J, Perumalla C, Heap G. Complications of transrectal versus transperineal prostate biopsy. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:48–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grummet JP, Weerakoon M, Huang S, et al. Sepsis and ‘superbugs’: should we favour the transperineal over the transrectal approach for prostate biopsy? BJU Int. 2014;114:384–388. doi: 10.1111/bju.12536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emiliozzi P, Corsetti A, Tassi B, Federico G, Martini M, Pansadoro V. Best approach for prostate cancer detection: a prospective study on transperineal versus transrectal six-core prostate biopsy. Urology. 2003;61:961–966. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)02551-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Franco CA, Jallous H, Porru D, et al. A retrospective comparison between transrectal and transperineal prostate biopsy in the detection of prostate cancer. Archivio Italiano di Urologia e Andrologia. 2017;89:55–59. doi: 10.4081/aiua.2017.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pepe P, Garufi A, Priolo G, Pennisi M. Transperineal versus transrectal MRI/TRUS fusion targeted biopsy: detection rate of clinically significant prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15:e33–ee6. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdollah F, Novara G, Briganti A, et al. Trans-rectal versus trans-perineal saturation rebiopsy of the prostate: is there a difference in cancer detection rate? Urology. 2011;77:921–925. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo L-H, Wu R, Xu H-X, et al. Comparison between ultrasound guided transperineal and transrectal prostate biopsy: A prospective, randomized, and controlled trial [J]. Scientific reports. 2015;5(16089). https://www.nature.com/articles/srep16089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Hara R, Jo Y, Fuji T, et al. Optimal approach for prostate cancer detection as initial biopsy: prospective randomized study comparing transperineal versus transrectal systematic 12-core biopsy. Urology. 2008;71:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takenaka A, Hara R, Ishimura T, et al. A prospective randomized comparison of diagnostic efficacy between transperineal and transrectal 12-core prostate biopsy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2008;11:134–138. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cerruto MA, Vianello F, D’Elia C, Artibani W, Novella G. Transrectal versus transperineal 14-core prostate biopsy in detection of prostate cancer: a comparative evaluation at the same institution. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2014;86:284–287. doi: 10.4081/aiua.2014.4.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan H, Xie H, Ying Y, et al. Pioglitazone use in patients with diabetes and risk of bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:1627–1638. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S164840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan H, Ying Y, Xie H, et al. Secondhand smoking increases bladder cancer risk in nonsmoking population: a meta-analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:3781–3791. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S175062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Udeh EI, Amu OC, Nnabugwu II, OFN O. Transperineal versus transrectal prostate biopsy: our findings in a tertiary health institution. Niger J Clin Pract. 2015;18:110–114. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.146991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tian X, Zhu C, Li T, Li X. Comparison of the clinical value of transperineal and transrectal prostate biopsy guided by transrectal ultrasonography in diagnosis of prostate cancer. China J Modern Med. 2014;24:80–82. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe M, Hayashi T, Tsushima T, Irie S, Kaneshige T, Kumon H. Extensive biopsy using a combined transperineal and transrectal approach to improve prostate cancer detection. Int J Urol. 2005;12:959–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baco E, Rud E, Eri LM, et al. A randomized controlled trial to assess and compare the outcomes of two-core prostate biopsy guided by fused magnetic resonance and transrectal ultrasound images and traditional 12-core systematic biopsy. Eur Urol. 2016;69:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasivisvanathan V, Rannikko AS, Borghi M, et al. MRI-targeted or standard biopsy for prostate-cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1767–1777. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown LC, Ahmed HU, Faria R, et al. Multiparametric MRI to improve detection of prostate cancer compared with transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy alone: the PROMIS study. Health Technol Assess. 2018;22:1–176. doi: 10.3310/hta22390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borkowetz A, Hadaschik B, Platzek I, et al. Prospective comparison of transperineal magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasonography fusion biopsy and transrectal systematic biopsy in biopsy-naive patients. BJU Int. 2018;121:53–60. doi: 10.1111/bju.14017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu J, Ji A, Xie B, et al. Is magnetic resonance/ultrasound fusion prostate biopsy better than systematic prostate biopsy? An updated meta- and trial sequential analysis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:43571–43580. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Details of excluded studies. Table S2. Sensitivity analysis of RCTs. Table S3. Sensitivity analysis of observational studies. Figure S1. Risk of bias assessment of RCTs. (ZIP 605 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All analyses were based on previous published studies and could be searched in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure.