Abstract

Background:

Access to community-based specialist palliative care teams has been shown to improve patients’ quality of life; however, the impact on health system expenditures is unclear. This study aimed to determine whether exposure to these teams reduces health system costs compared with usual care.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective matched cohort study in Ontario, Canada, using linked administrative data. Decedents treated by 1 of 11 community-based specialist palliative care teams in 2009/10 and 2010/11 (the exposed group) were propensity score matched (comorbidity, extent of home care, etc.) 1 to 1 to similar decedents in usual care (the unexposed group). The teams are comprised of a core group of specialized physicians, nurses and other providers; their role is to manage symptoms around the clock, provide education and coordinate care. Our primary outcome was the overall difference in health system costs (among 5 health care sectors) between all matched pairs of exposed versus unexposed patients in the last 30 days of life.

Results:

The total cohort of decedents included 3109 matched pairs. Among matched pairs, the mean health system cost difference was $512 (95% confidence interval [CI] −$641 to −$383) lower in the last 30 days among exposed than among unexposed patients. In the last 30 days, the mean home care costs of the exposed group were $189 higher (95% CI −$151 to $227) than those of the unexposed group, but their mean hospital costs were $733 lower (95% CI −$950 to −$516).

Interpretation:

Our study suggests that health system costs are lower for patients who have access to community-based specialist teams than for those who receive usual care alone, largely because of decreased hospital costs. Ensuring access to in-home palliative care support, as provided by these teams, is an efficacious strategy for reducing health care expenditures at the end of life.

Research has consistently demonstrated that access to specialist palliative care teams in the community improves the quality of life of patients at the end of life1–3 and helps actualize their preference for a home death.4–6 Although the teams that have been evaluated vary widely in terms of configuration, they often consist of a core team of interdisciplinary providers with palliative care expertise including physicians, nurses and personal support workers who deliver support to patients in their homes.7 In addition, there is growing evidence that these specialist palliative care teams help reduce the use of health system resources.8 Specialist teams provide enhanced symptom management, monitor the patient’s condition and offer education to family caregivers and may thus proactively avoid crises that would otherwise result in hospital admissions, which can be costly.6,9,10 However, the actual impact of these interventions in reducing health system costs is less clear. Systematic reviews of outcomes of community-based palliative care, including services in the home, have reported mixed evidence of lower costs, and it has been difficult to draw definitive conclusions because of heterogeneity in the components of interventions and different health systems.4,11–13

The purpose of our study is to examine the impact of community-based specialist palliative care teams on health system costs compared with usual care, such as end-of-life home care alone. In Ontario, Canada, several regions have independently created their own specialist palliative care teams, which vary in terms of team composition, caseload and geographic region served. This forms a natural experiment to examine diverse specialist palliative care teams within a single health care system. Specifically, this study investigates whether there are differences in health system costs between propensity score matched pairs of patients who received care from specialist palliative care teams and patients who received usual care within the overall cohort and individual teams.

Methods

Study design

This is a retrospective matched cohort study of deceased palliative care patients in Ontario, Canada, during fiscal years 2009/10 and 2010/11. We examined health system costs in the last 30 days of life for patients who received services from 1 of 11 interdisciplinary palliative care teams (the exposed group) and used propensity score matching to create an equivalent comparison group of patients who received usual care (the unexposed group). The demographic and service use characteristics of the cohort were identified by linking health care administrative data sets using encrypted unique patient identifiers. The cost difference between matched pairs was determined for each of the teams separately and collectively to determine an overall cohort effect.

Study setting

In Ontario, most community-based palliative care is delivered by home care providers (e.g., nurses and personal support workers).14 Patients who receive this type of care are referred to in this study as the unexposed “usual care” group. In usual care, there is no involvement from community-based specialist palliative care teams. Patients are eligible for home care if they require nursing care, personal support care or therapy, and they are eligible for end-of-life home care if they also have a life-limiting or life-threatening health condition with a prognosis of less than 6 months to live and they have pain and symptom issues related to the end of life. The end-of-life designation entitles patients to more home care hours and sometimes to providers with more end-of-life care experience.15 Population-based data in the province show that about a third of deceased patients received home care in the last year of life and 19% received end-of-life home care.16 Over half (56%) of deaths occur in hospital, while only 20% occur at home.14,17 Access to home care or other palliative care services such as residential hospices (i.e., free-standing, home-like facilities in the community) and hospital palliative care units is very limited.18 End-of-life home care may be provided by 1 or more service provider organizations, with little coordination between them. Furthermore, care provided by these organizations varies in terms of the palliative care training of the home care workers and the extent of after-hours coverage. Moreover, most family physicians provide care independently of home care and rarely make home visits.19 In contrast, patients who receive care from a specialist palliative care team, referred to in this study as the exposed group, get care that is accessible around the clock, coordinated and provided by specially trained providers.

Specialist palliative care teams

In Ontario, regions have independently developed their own community-based specialist palliative care teams to improve palliative care access and delivery over time.20 These teams vary in terms of the geographic area they serve, patient admissions (range 90–830 patient deaths over 2 yr) and team size (3 to 18 full-time equivalent [FTE] positions) (Table 1). The mean time from admission to a specialist palliative care team to death was 73 days.6 However, they all consist of a core group of interdisciplinary providers including community physicians and nurses with specialized palliative care expertise. Some teams also involve allied health professionals, such as social workers and psychosocial-spiritual counsellors. Common roles of the community-based specialist palliative care teams include ongoing comfort care, symptom management 24/7, education and care coordination. Patients are usually referred to the teams during the last months of life on the basis of clinical factors, functional decline and expected prognosis of less than 6 months. The specialist team visits the patient in their home to assess their needs and develop a care plan. These teams work in conjunction with home care service providers, including nurses and personal support workers, to provide integrated palliative care in patients’ homes, similar to the visiting hospice services provided by MacMillan nurses in the United Kingdom. The structure and development of these teams have been previously described in detail.20,21

Table 1:

Team characteristics before matching

| Team | Date established | Geographic area served | No. decedents in FY 2009/10 and FY 2010/11 | Median time on service, d | Palliative care physicians, no. of FTE (funding source) | Nurses, no. of FTE | Other team members, no. of FTE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2009 | Urban | 830 | 40 | 1 (FFS) | 8 | 2 |

| 2 | 2009 | Suburban | 221 | 53 | 3 (FFS) | 3.5 | 5 |

| 3 | 2009 | Suburban | 144 | 38 | 1 (FFS) | 1 | 0.6 |

| 4 | 2009 | Suburban | 125 | 40 | 1 (FFS) | 2 | 1 |

| 5 | 2009 | Suburban | 105 | 36 | 0.5 (FFS) | 1 | 0.2 |

| 6 | 2009 | Rural | 90 | 63 | 2 (APP) | 2 | 1.2 |

| 7 | 1986 | Urban | 676 | 45 | 11.5 (APP) | 1 | 5.9 |

| 8 | 2007 | Suburban | 497 | 49 | 2 (FFS and APP) | 2 | 1 |

| 9 | 1998 | Urban | 775 | 38 | 1.3 (FFS) | 3 | 1.7 |

| 10 | 2004 | Rural | 268 | 23 | 0.6 (APP) | 1 | 2.5 |

| 11 | 1979 | Rural | 181 | 32 | 6 (FFS) | 2 | 4.7 |

Note: APP = alternative payment plan (i.e., physician reimbursement is a combination of FFS and salary), FFS = fee-for-service (i.e., physicians bill for each aspect of care and service they provide according to a set price mechanism), FTE = full time equivalent, FY = fiscal year.

Cohort selection

Exposed group

Eleven teams were identified that met the above criteria as well as the following: (a) had little or no change in staffing or structure during the cohort time frame (2009 to 2011), (b) did not limit admission criteria to 1 disease (e.g., cancer) and (c) served more than 50 patients per year. Within each team, patients were included if they had died by Apr. 1, 2011, were at least 18 years of age and had a valid provincial health insurance number.

Unexposed group

One of 2 a priori approaches was taken to identify appropriate control groups, depending on when the team in question was established. First, for teams that were established after 2009 (teams 1–6), all decedents were matched within the same health regions during fiscal years 2007/08 and 2008/09 (2 yr before the team was established). The research team confirmed that no major policy or organizational changes occurred in these study regions between 2007 and 2011, with the exception of the introduction of the teams.6 Second, for teams that started before 2009 (teams 7–11), all decedents were matched from similarly resourced regions (i.e., regions that were similar in size, geography and access to home care services but did not have access to community-based specialist palliative care teams) during the study period of 2009/10 and 2010/11. This second approach was taken because (a) many of these teams were established a decade or more ago, and the home care system in the era before the teams were introduced might have been considerably different than in 2009/10 and 2010/11; and (b) a major health policy that regionalized home care was instituted in 2006, making comparisons before this time problematic.22

Data sources

The teams provided their patient lists during fiscal years 2009/10 and 2010/11, which were linked to multiple administrative databases using the patients’ provincial health insurance numbers. The provincial vital statistics database was used to confirm date of death. The Discharge Abstract Database was used to determine hospital and palliative care unit admissions, as well as comorbidity score weight, presence of cancer condition and hospital death. We used the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System to determine emergency department visits. The Continuing Care Reporting System was used to calculate costs for patients in chronic or complex inpatient beds. The Home Care Database provided dates of publicly funded home care service use and service type. The Ontario Health Insurance Plan database and physician billing codes were used to determine physician visits. We used Statistics Canada census data on postal codes to determine region and rurality. These linked data sets were also used to determine the population of unexposed patients, from which matches were selected.

Propensity score matching

We used propensity score matching to match on propensity to have received care from the community-based specialist palliative care team and create equivalent comparison groups in usual care for each intervention team. Matching on the propensity score can estimate the effect of the intervention, which is unbiased by differences in measured preintervention covariates.23 We matched on variables before exposure to the intervention: age at death, sex, cancer or noncancer, home care service type (palliative, supportive, maintenance, rehabilitation) and time in home care, Aggregated Diagnosis Group (comorbidity weighting that determines clinically cogent groups from 6 to 18 mo before death)24 and hospital and emergency department use before death (during the period from 6 to 18 months before death).6 Eleven cohorts were created, consisting of pairs of exposed patients and unexposed subjects who were selected from the appropriate control population (see cohort selection).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the difference in total health system costs between the individual matched pairs of exposed versus unexposed decedents in the last 30 days of life across the overall aggregated cohort. We also calculated the paired difference in health system costs for each individual team. Health system costs were determined for the 5 health care sectors: (a) physician visits, (b) subacute care,25 (c) home care, (d) inpatient hospital admission and (e) emergency department visits. The secondary outcome was the individual matched-pair difference in costs for each specific health care sector in the last 30 days of life for the overall cohort. Costing macros that have been validated in Ontario data were applied to calculate costs for the above services.26 All physician costs beyond palliative home visits were included, regardless of specialty or care setting.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine patient characteristics and health system costs. The overall cohort comprised the matched pairs. We used paired t tests to determine significance in the differences in health system costs in the last 30 days of life between exposed and unexposed patients within each matched pair, summarized by team and overall cohort in a forest plot.27 Additionally, we report the paired difference in cost for each health care sector for the overall cohort. Finally, we performed a post hoc sensitivity analysis where overall and individual health care sector matched-pair differences in cost were weighted according to the number in each team cohort. Analysis was completed using SAS version 9 statistical software. All tests were 2 sided and a p value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Hamilton Health Sciences/McMaster University research ethics review board (11–403).

Results

In total, the specialist teams served 3912 patients (exposed group), whereas there were 41 113 patients available for inclusion in the unexposed group (Table 2). The characteristics between the initial exposed and unexposed groups differed greatly before propensity score matching. For instance, 79% had a cancer diagnosis and 78% received end-of-life home care services in the exposed group, compared with only 35% and 15% in the unexposed group (p < 0.001), respectively. Propensity score matching created similar groups across a number of patient characteristics, generating 3109 paired decedents. After matching, in both groups 79% of patients had a cancer diagnosis and 78% received end-of-life home care services. The main difference between the 2 groups was their exposure to a community-based specialist palliative care team.

Table 2:

Comparison of patient characteristics before and after propensity score matching

| Characteristic | Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | p value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Unexposed | Exposed | Unexposed | Exposed | ||

| No. of patients (pooled across the teams) | 41 133 | 3912 | 3109 | 3109 | |

|

| |||||

| Age at death, yr, median (IQR) | 80 (69–87) | 75 (64–84) | 74 (63–83) | 75 (64–84) | NS |

|

| |||||

| Cancer diagnosis, no. (%) | 14 443 (35.1) | 3073 (78.6) | 2481 (79.8) | 2469 (79.4) | 0.7 |

|

| |||||

| Female, no. (%) | 20 895 (50.8) | 2032 (51.9) | 1609 (51.8) | 1600 (51.5) | 0.8 |

|

| |||||

| Adjusted Clinical Group comorbidity weighting, mean ± SD | 5.12 ± 4.09 | 6.30 ± 4.04 | 6.21 ± 3.93 | 6.20 ± 3.98 | NS |

|

| |||||

| Home care service type, no. (%) | |||||

|

| |||||

| End of life | 6208 (15.1) | 3041 (77.7) | 2409 (77.5) | 2409 (77.5) | 1.0 |

|

| |||||

| Long-term supportive | 3408 (8.3) | 210 (5.4) | 145 (4.7) | 145 (4.7) | 1.0 |

|

| |||||

| Maintenance | 7692 (18.7) | 328 (8.4) | 278 (8.9) | 278 (8.9) | 1.0 |

|

| |||||

| Rehab/acute care | 6478 (15.7) | 157 (4.0) | 106 (3.4) | 106 (3.4) | 1.0 |

|

| |||||

| None | 17 347 (42.2) | 176 (4.5) | 171 (5.5) | 171 (5.5) | 1.0 |

|

| |||||

| Time from first receipt of most severe home care service type to death, d, mean ± SD | |||||

|

| |||||

| End of life | 15.47 ± 56.48 | 86.18 ± 107.29 | 79.23 ± 102.02 | 79.32 ± 102.05 | NS |

|

| |||||

| Long-term supportive | 23.92 ± 81.17 | 31.00 ± 87.25 | 37.96 ± 95.92 | 27.84 ± 83.51 | NS |

|

| |||||

| Maintenance | 63.68 ± 124.80 | 82.02 ± 131.69 | 81.64 ± 131.06 | 83.55 ± 132.16 | NS |

|

| |||||

| Rehab/acute care | 69.70 ± 113.27 | 76.05 ± 113.98 | 79.29 ± 112.60 | 80.12 ± 114.96 | NS |

|

| |||||

| No. of prior emergency department visits, mean ± SD | 1.16 ± 2.10 | 1.43 ± 2.11 | 1.40 ± 1.95 | 1.36 ± 1.96 | NS |

|

| |||||

| Prior length of stay in hospital, d, mean ± SD | 7.18 ± 22.23 | 7.53 ± 17.09 | 6.84 ± 14.17 | 6.73 ± 14.85 | NS |

|

| |||||

| No. of prior hospital visits, mean ± SD | 0.56 ± 1.04 | 0.75 ± 1.14 | 0.76 ± 1.15 | 0.70 ± 1.07 | NS |

|

| |||||

| Income quintile, no. (%) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 1 (lowest) | 10 288 (25.0) | 668 (17.1) | 772 (24.8) | 536 (17.2) | < 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| 2 | 9053 (22.0) | 746 (19.1) | 703 (22.6) | 605 (19.5) | 0.003 |

|

| |||||

| 3 | 7565 (18.4) | 720 (18.4) | 604 (19.4) | 550 (17.7) | 0.08 |

|

| |||||

| 4 | 7460 (18.1) | 872 (22.3) | 585 (18.8) | 675 (21.7) | 0.005 |

|

| |||||

| 5 (highest) | 6555 (15.9) | 906 (23.2) | 437 (14.1) | 743 (23.9) | < 0.001 |

Note: IQR = interquartile range, NS = not significant, SD = standard deviation.

For characteristics reported as means and medians it was not possible to calculate actual p values at the time of publication because the individual data were no longer accessible, for privacy reasons.

Health system costs for the overall cohort and individual teams

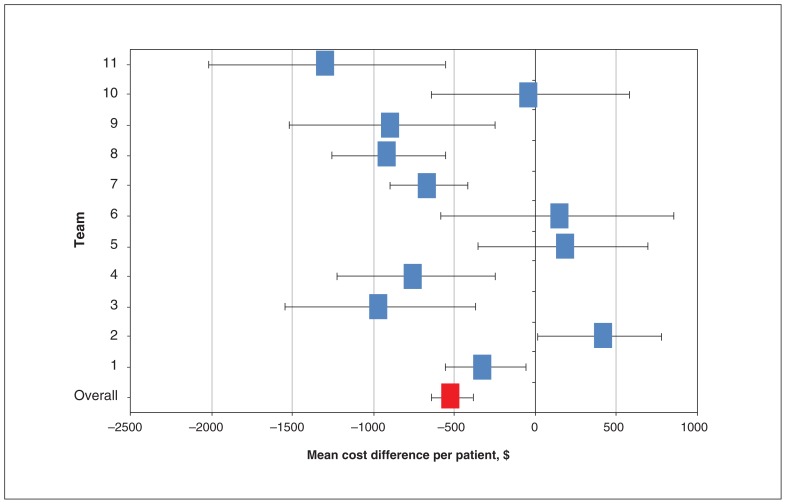

In the overall cohort, the mean health system costs in the last 30 days of life were $10 649 per decedent in the exposed group compared with $12 185 per decedent in the unexposed group. Using the matched-pair analysis, the mean difference in health system costs per patient pair was $512 lower (95% confidence interval [CI] −$641 to −$383) at 30 days (p < 0.001) among exposed patients than among unexposed patients (Figure 1, Appendix 1 [available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/1/E73/suppl/DC1]). In the post-hoc sensitivity analysis, when team-weighted, this overall matched-pair cost difference was $460 (95% CI −$610 to −$310) per patient (p < 0.001) (Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/1/E73/suppl/DC1).

Figure 1:

Mean matched-pair differences in health care costs by team and overall, between exposed and unexposed patients in the last 30 days of life (n = 3109). Note: Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Looking at regional teams individually in the last 30 days of life, we found 7 of the 11 teams were associated with significant mean paired cost reductions. The costs for the 7 teams with significant mean paired differences in costs wer $1285 to $307 lower among the exposed group than among the unexposed group. The differences in costs for the 4 teams that did not have significant paired cost reductions at 30 days ranged from a $31 decrease to a $396 increase.

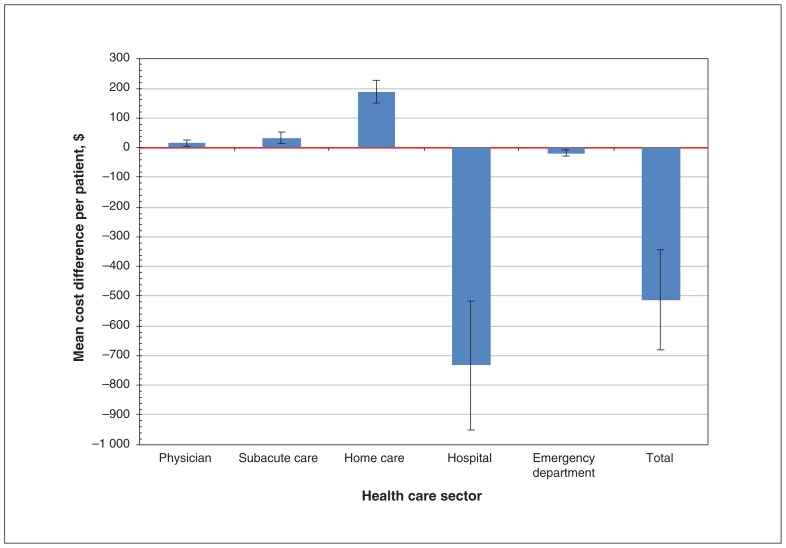

Costs by health care sector

Mean paired differences in health care costs in the last 30 days before death differed by sector as well (Figure 2, Appendix 2). The greatest cost differences were observed in the home care and hospital sectors. At 30 days, the paired difference analysis showed that the mean home care costs of the exposed group were $189 (95% CI $151 to $227) higher than those of the unexposed group, but their hospital costs were $733 (95% CI −$950 to −$516) lower. There were statistically but not clinically significant differences in costs among matched pairs in the use of emergency department services, subacute care or physician services.

Figure 2:

Mean matched-pair differences in health care sectorial costs between exposed and unexposed patients in the last 30 days of life (n = 3109). Note: Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Interpretation

Our overall analysis of 11 community-based specialist palliative care teams suggests that exposure to these teams compared with usual home care is associated with a reduction in health system costs at the end of life. Our data suggest that access to community-based specialist palliative care teams, in addition to usual care (which was primarily end-of-life home care services), helps to reduce end-of-life hospital costs. These findings were consistent even though the teams differed in geographic area served, team size and team organization.

Generally, teams seemed to keep patients in the home and avoid or reduce hospital admissions. Because the teams aim to expertly manage, constantly monitor and rapidly respond to complex symptoms and changes in the patient’s condition in the home 24/7, they can help patients to stay at home where they might otherwise go to hospital. Indeed, for most teams, we found a reduction in hospital costs for the exposed versus the unexposed groups that more than offset the higher home care costs. The cost of home care service (including the cost of delivering community-based specialist palliative care teams) was a fraction of the cost of a hospital bed, which typically ranges from $1000 to $2000 per day for noncritical care9,28–30; this can lead to overall health system savings. Furthermore, support and education from the specialist palliative care teams may prompt patients and families to choose comfort care measures rather than aggressive treatments in hospital.

Nonetheless, 4 of the 11 community-based specialist palliative care teams (team 2, 5, 6 and 10) did not individually show significant cost savings. This may be due to a few factors: they tended to be very small teams, serving no more than 40–100 decedents per year in large rural or suburban geographic areas. As well, 2 of the teams only had a half-FTE palliative care physician.

Two systematic reviews examined the cost benefits of home-based palliative care interventions, identifying over a dozen randomized trials that included cancer and noncancer populations.4,8 These reviews concluded that the evidence for cost-benefit was inconclusive, because the community-based team interventions were very heterogeneous: the interventions differed (e.g., some were telephone-based, some were educational only, some were nurse led only, some did not include after-hours coverage), the countries and health systems differed and the cost outcome definitions differed. Our study is unique because it includes independent teams, where the core components of the team-based intervention were the same and they occurred in the same health system, with standardized outcome definitions. However, our study population did mainly (80%) serve cancer patients.

Limitations

We could not match on data that are unavailable in administrative data, such as availability of existing caregiver support, patient preferences for hospital use, marital status and education level. We did not adjust for covariates using a regression because there were no significant differences after propensity score matching, though income quintiles were not balanced. Furthermore, not all potential costs were accounted for, such as drugs, costs of private home care services or other indirect costs incurred by informal caregivers. Our study period was 2009–2011 because of lags in administrative data linkage, but the data from this period remain relevant in that there have been no major policy changes within the home care sector and there has been little decrease in the proportion of deaths in hospital since then.17 In addition, for the 5 older teams matched to decedents from a comparable region, there may have been regional differences leading to confounding. We did not differentiate multiple visits within hospital costs; nonetheless, even among cancer patients who die in hospital in Ontario, the majority (77%) only have a single visit in the last month.31 Because we used a matched-pair analysis at the individual pair level (and pairs are chosen from within the same or similar regions), we did not account for clustering within teams. Our post hoc sensitivity analysis, however, weighted by team, produced results that were similar in value and in level of significance. Finally, we were not able to isolate and compare the specific personnel costs of each team. A strength of the study is that we propensity score matched the exposed and unexposed groups on the basis of cancer/noncancer diagnosis, end-of-life home care use, length of time in home care, and comorbidity, controlling for major factors affecting access to a specialist palliative care team.

Conclusion

Although the teams varied in composition and geographic area served, the core team interventions contained common components, such as expert symptom management, patient education, coordination of care, 24/7 telephone access and ongoing conversations about care preferences. Our findings demonstrate that specialist palliative care teams that feature these qualities are associated with reduced use of costly hospital care, which contributed to health system cost savings. Involvement from a community-based specialist palliative care team is a method for reducing the high cost of end-of-life care. Future research should examine which aspects of the specialist palliative care teams contribute most to reducing health system costs using multilevel regression models and should assess the impact of these teams on informal caregiver costs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Hsien Seow was responsible for study design and data acquisition. All authors were involved in the data analysis, interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript, gave approval of the final version for publication and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (ref. no. 115112).

Disclaimer: This study used databases maintained by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/1/E73/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Higginson IJ, Evans CJ. What is the evidence that palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients and their families? Cancer J. 2010;16:423–35. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181f684e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassianos AP, Ioannou M, Koutsantoni M, et al. The impact of specialized palliative care on cancer patients’ health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:61–79. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3895-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepperd S, Wee B, Straus SE. Hospital at home: home-based end of life care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD009231. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD007760. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007760.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luckett T, Davidson PM, Lam L, et al. Do community specialist palliative care services that provide home nursing increase rates of home death for people with life-limiting illnesses? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:279–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seow H, Brazil K, Sussman J, et al. Impact of community based, specialist palliative care teams on hospitalisations and emergency department visits late in life and hospital deaths: a pooled analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g3496. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bainbridge D, Seow H, Sussman J. Common components of efficacious in-home end-of-life care programs: a review of systematic reviews. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:632–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith S, Brick A, O’Hara S, et al. Evidence on the cost and cost-effectiveness of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med. 2014;28:130–50. doi: 10.1177/0269216313493466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bekelman JE, Halpern SD, Blankart CR, et al. International Consortium for End-of-Life Research (ICELR) Comparison of site of death, health care utilization, and hospital expenditures for patients dying with cancer in 7 developed countries. JAMA. 2016;315:272–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung MC, Earle CC, Rangrej J, et al. Impact of aggressive management and palliative care on cancer costs in the final month of life. Cancer. 2015;121:3307–15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Candy B, Holman A, Leurent B, et al. Hospice care delivered at home, in nursing homes and in dedicated hospice facilities: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48:121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.García-Pérez L, Linertová R, Martín-Olivera R, et al. A systematic review of specialised palliative care for terminal patients: Which model is better? Palliat Med. 2009;23:17–22. doi: 10.1177/0269216308099957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;299:1698–709. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.14.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bainbridge D, Seow H. Palliative care experience in the last 3 months of life: a quantitative comparison of care provided in residential hospices, hospitals, and the home from the perspectives of bereaved caregivers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35:456–63. doi: 10.1177/1049909117713497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bainbridge D, Seow H, Sussman J, et al. Factors associated with not receiving homecare, end-of-life homecare, or early homecare referral among cancer decedents: a population-based cohort study. Health Policy. 2015;119:831–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanuseputro P, Budhwani S, Bai YQ, et al. Palliative care delivery across health sectors: a population-level observational study. Palliat Med. 2017;31:247–57. doi: 10.1177/0269216316653524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Table 13-10-0715-01: Deaths, by place of birth (hospital or non-hospital) Ottawa: Statistics Canada; [accessed 2018 Dec 20]. modified 2018 Dec 20. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310071501&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sussman J, Barbara L, Bainbridge D, et al. Health system characteristics of quality care delivery: a comparative case study evaluation of palliative care for cancer patients in four regions in Ontario, Canada. Palliat Med. 2012;26:322–35. doi: 10.1177/0269216311416697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall D, Howell D, Brazil K, et al. Enhancing family physician capacity to deliver quality palliative home care: an end-of-life, shared-care model. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1703–1703.e7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seow H, Bainbridge D, Brouwers M, et al. Common care practices among effective community-based specialist palliative care teams: a qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017 Apr 19; doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001221. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seow H, Bainbridge D. The development of specialized palliative care in the community: a qualitative study of the evolution of 15 teams. Palliat Med. 2018;32:1255–66. doi: 10.1177/0269216318773912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Local Health System Integration Act, 2006, S.O. 2006, c.4. [accessed 2018 Dec 20]. Available: Available: www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/06l04.

- 23.Rosenbaum P, Rubin D. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat. 1985;39:33–8. doi: 10.2307/2683903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austin PC, van Walraven C, Wodchis WP, et al. Using the Johns Hopkins Aggregated Diagnosis Groups (ADGs) to predict mortality in a general adult population cohort in Ontario, Canada. Med Care. 2011;49:932–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318215d5e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hospital chronic care co-payment questions and answers. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2018. [accessed 2018 Dec 20]. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/publications/chronic/chronic.aspx#chroniccare. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wodchis WP, Bushmeneva K, Nikitovic M, et al. Working Paper Series Vol 1. Toronto: Health System Performance Research Network; May, 2013. [accessed 2018 Dec 20]. Guidelines on person-level costing using administrative databases in Ontario. Available: www.hsprn.ca/uploads/files/Guidelines_on_PersonLevel_Costing_May_2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bravata DM, Olkin I. Simple pooling versus combining in meta-analysis. Eval Health Prof. 2001;24:218–30. doi: 10.1177/01632780122034885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.2014 Annual report of the Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2014. [accessed 2018 Dec 20]. Chapter 3, section 3.08: Palliative care; pp. 258–88. Available: www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en14/308en14.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Georghiou T, Bardsley M. Exploring the cost of care at the end of life. London (UK): Nuffield Trust; 2014. [accessed 2018 Dec 20]. Available: www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-01/end-of-life-care-web-final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hospital-adjusted expenses per inpatient day by ownership — Timeframe: 2016. San Francisco: Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation; [accessed 2018 Dec 20]. Available: http://kff.org/health-costs/state-indicator/expenses-per-inpatient-day-by-ownership. [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeCaria K, Dudgeon D, Green E, et al. Acute care hospitalization near the end of life for cancer patients who die in hospital in Canada. Curr Oncol. 2017;24:256–61. doi: 10.3747/co.24.3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.