Introduction

Clostridium difficile toxin (CDT) colitis is the most common cause of infectious diarrhoea in hospitalized patients and is a frequent cause of morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients. Failure to mount an immune response to CDT appears to be an important mechanism for recurrent diarrhoea [1, 2]. One of the factors associated with an increased risk for recurrence of CDT colitis is advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1]. There is anecdotal evidence of benefit from treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in adults with refractory CDT colitis [3–7] following failure of standard treatment with metronidazole and vancomycin [8]. However, none of the cases reported have CKD. We report two cases of CKD patients with refractory CDT colitis, treated successfully with IVIG.

Case Report 1

A 67-year-old lady with type I diabetes mellitus (DM), diabetic nephropathy and hypertension was admitted to the hospital for tests regarding diabetic gastroparesis. During her stay, she developed three episodes of sepsis, two due to pneumonia and one urinary tract infection. All these septic episodes were associated with shock, acute-on-chronic kidney disease (background CKD stage 4) and admission to the intensive therapy unit. During her last septic episode, in March 2007, she developed life-threatening CDT diarrhoea and pseudo-membranous colitis that required aggressive hydration, inotropic support and haemofiltration. The diarrhoea was refractory to two coures of treatment with metronidazole and one of vancomycin. Computerized tomography scan of the abdomen and subsequent sigmoidoscopy confirmed severe pseudo-membranous colitis. A total colectomy was considered, but she was deemed unfit for surgery, in view of the underlying sepsis and her acute kidney injury.

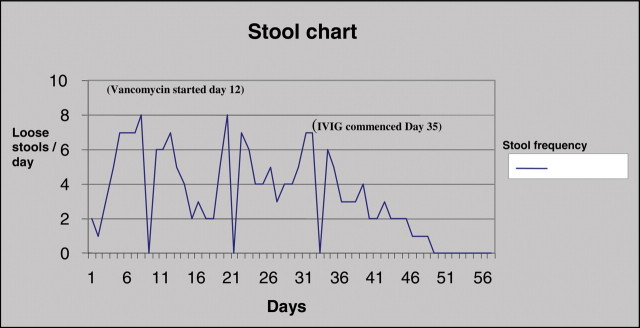

After liaising with a consultant microbiologist (RC), she was started on IVIG in the form of Intratect® 0.4 g/kg each infusion by five infusions, which resulted in an improvement of symptoms, resolution of diarrhoea (Figure 1) and inflammatory markers. Her acute kidney injury recovered and she became independent of haemofiltration during the course of therapy. Subsequent stool samples showed clearance of CDT.

Fig. 1.

Patient 1: Stool frequency chart for patient with Clostridium difficile toxin colitis.

Case Report 2

A 57-year-old man with type 2 DM and CKD stage 3 was admitted with a 4-week history of non-specific symptoms of lethargy, general malaise, nausea, weight loss, hypotension and severe cardiac failure. Subsequent investigations confirmed the diagnosis of primary amyloidosis on rectal biopsy. He was started on intravenous cefuroxime for chest infection whilst on chemotherapy, melphalan and dexamethasome. Four days later he developed CDT diarrhoea. His CDT infection was complicated with acute-on-chronic renal failure, with peak urea and creatinine of 61.5 mmol/L and 347 μmol/L respectively. He had a colonoscopy that confirmed pseudo-membranous colitis. His diarrhoea was refractory to two courses of metronidazole and vancomycin. Subsequently, he was started on IVIG (Intratect® 0.4 g/kg each infusion). Two days into his therapy, his diarrhoea started settling and he showed marked symptomatic improvement. Inflammatory markers started to come down and his diarrhoea completely settled after a 3-day course of IVIG therapy. His renal function improved with urea and creatinine of 22.4 mmol/L and 164 μmol/L respectively. Unfortunately, the patient later died of an unrelated cause—ventricular tachyarrhythmia secondary to his cardiac amyloid.

The treatment of refractory CDT colitis remains controversial. There is some evidence of successful use of IVIG in the treatment of refractory CDT colitis, used as salvage therapy after failure of standard therapy with metronidazole and vancomycin [3–8].

The five most important factors associated with a complicated recurrent CDT disease include increasing age >65, leucocytosis >20 × 109 cells/L, immunosuppression, hospital acquired infection and CKD [9]. Complicated CDT disease can be associated with toxic megacolon (disease requiring colectomy) and shock or death. Deficiency of one or more IgG subclasses in patients with renal failure has been implicated as one of the plausible mechanisms, suggesting inhibition of their synthesis in the uraemic state. [10]. At present, no lab provides a diagnostic service to identify poor IgG response to C. difficile. It would have been useful in both of the above cases.

Passive or active immunization against CDT protects animals against C. difficile-induced colitis [11]. Serum antibodies to CDTs A and B are present in approximately 60% of adults in the United States. In one study of patients with nosocomial CDT infection, an increase in serum IgG anti-toxin A antibody levels was strongly associated with asymptomatic carriage. The lack of this antibody response in patients with CKD has been associated with a greater risk for CDT diarrhoea.

The rationale for the use of IVIG in both our CKD patients is based on four points:

Case reports of successful clinical use of IVIG in refractory CDT colitis [3–7].

Patients with refractory or relapsing CDT colitis have low levels of anti-toxin antibodies [12–14].

Possible deficiency of Ig subclasses in CKD.

CDT colitis is toxin-mediated and we assume that the immunoglobulin acts by binding and neutralizing the CDT. The intravenous administration of 150 mg/kg of immunoglobulin results in the serum level of IgG levels of 5 mg/ml whereas toxin neutralizing activity is evident in vitro at IgG levels of approximately 1 mg/ml [15]. Thus the neutralizing levels of IgG in the blood are readily achievable with IVIG. However, the precise mechanism of action of IVIG is not clear, as to be effective, IgG anti-toxin must leave the blood circulation and bind to toxins A and B within the colonic lamina propria or lumen [15].

Since our success, two lupus patients with CKD 5, on a chronic haemodialysis programme and immunosuppression, had refractory CDT diarrhoea following antibiotic therapy in the Royal Liverpool University hospital. They were both treated with metronidazole and vancomycin without any success. After a 5-day course of Vigam® 0.4 g/kg, CDT diarrhoea resolved in both patients (personal communication from Hameed Anijeet and Shahed Ahmed).

Currently in the United Kingdom, IVIG is only licensed for use in the treatment of primary immunodeficiency syndromes (congenital agammaglobulinemia, severe combined immunodeficiency syndromes, common variable immunodeficiency, X-linked immunodeficiency, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome); idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; Kawasaki disease (in combination with aspirin). However, there is increasing use of IVIG as an immune modulator in a variety of autoimmune, inflammatory diseases and in acute infections. The increased risks associated with use of IVIG in sick patients can be minimized by using it in a controlled environment under close monitoring, and the potential benefits when used appropriately could be lifesaving, as clearly demonstrated in both our cases.

Most adverse effects of intravenous immunoglobulin are mild and transient, including headaches, flushing, fever, chills, fatigue, nausea, diarrhoea, blood pressure changes and tachycardia. Major adverse effects include acute renal failure, aseptic meningitis and thromboembolic complications [16]. Thromboembolic complications occur due to hyperviscosity, especially in patients with risk factors including advanced age, previous thromboembolic events, immobilization, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia or those receiving high-dose IVIG in a rapid infusion rate or excessive dose. Slow infusion rate and good hydration may prevent renal failure, thromboembolic events and aseptic meningitis. Although the use of intravenous immunoglobulin has been implicated in acute renal failure, in neither of our patients was a deterioration in their underlying renal function, as monitored throughout the course of therapy. We avoided the use of sucrose-based IVIG, as sucrose has been implicated in nephrotoxicity associated with the use of IVIG [17]. However, we believe that further research is required to assess the nephrotoxic effects of immunoglobulin in advanced CKD patients. We were also encouraged by various case reports where IVIG was used as an alternative agent in many renal diseases such as membranous nephropathy, IgA nephropathy, transplant rejection, etc.

A CD toxoid vaccine has induced strong antibody, anti-toxin A response in humans, but whether this can confer protective immunity against CDT diarrhoea and colitis remains to be proven [18].

Warny et al. [19] used bovine immunoglobulin concentrate (BIC) C. difficile prepared from the colostrum of cows immunized against the CDTs, resulting in high levels of neutralizing IgG anti-toxin. BIC C. difficile seems to be resistant to digestion in the human gastrointestinal tract, and specific anti-toxin A binding and neutralizing capacity has been retained. Hence, it can potentially be used as a passive oral immunotherapy to prevent and treat CDT-associated diarrhoea and colitis [19].

The incidence of CDT colitis is higher in the CKD population, with greater disease severity and higher mortality in the CKD group [20]. A combination of impaired immune function, malnutrition and disturbances in intestinal motility in CKD has been attributed to this higher incidence. Commonly implicated agents are cephalosporin (second and third generation) and co-amoxiclav, which are widely being used in current clinical practice.

We recommend that when treating CKD patients, the risk of CDT colitis should be borne in mind, the unnecessary use of drugs should be avoided and appropriate antibiotics be used once an infective cause is identified. The duration of antibiotic therapy should be kept to a minimum and should be stopped promptly if no infective cause is found.

Prevention of the disease should be encouraged by strict adherence to infection control measures and rational antibiotic prescription. The need for a high index of suspicion of CDT colitis is required for CKD patients, as the symptoms can be mistaken for drug-related side effects, i.e. from phosphate binders.

Further study is required before IVIG can be recommended as standard therapy for CKD patients with refractory CDT diarrhoea. However, the above-mentioned findings suggest that host factors, such as a reduced anti-toxin antibody response in patients with CKD, may be an important determinant of the likelihood of symptomatic relapse [21].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Fekety R, McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, et al. Recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea: characteristics of and risk factors for patients enrolled in a prospective, randomized, double-blinded trial. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:324. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly CP. Immune response to Clostridium difficile infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:1048. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199611000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salcedo J, Keates S, Pothoulakis C, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for severe Clostridium difficile colitis. Gut. 1997;41:366. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.3.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilcox MH. Descriptive study of intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53:882–884. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beales ILP. Intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Gut. 2005;51:451. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.3.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyne L, Kelly CP. Recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Gut. 2001;49:151–152. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.1.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mcpherson S, Rees CJ, Ellis R, et al. Treatment of severe, refractory, and recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:640–645. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McFarland LV, Elmer GW, Surawicz CM. Breaking the cycle: treatment strategies for 163 cases of recurrent Clostridium difficile disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1769. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pepin J, Routhier S, Gagnon S, et al. Management and outcomes of a first recurrence of Clostridium difficile-associated disease in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:758. doi: 10.1086/501126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antonia HM Bouts, Jean-Claude Davin, Raymond T Krediet, et al. Immunoglobulins in chronic renal failure of childhood: effects of dialysis modalities. Kidney International. 2000;58:629–637. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viscidi R, Laughon BE, Yolken R, et al. Serum antibody response to toxins A and B of Clostridium difficile. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:93. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aronsson B, Granstrom M, Mollby R, et al. Serum antibody response to Clostridium difficile toxins in patients with Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Infection. 1985;13:97–101. doi: 10.1007/BF01642866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aronsson B, Granstrom M, Mollby R, et al. Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for antibodies to Clostridium difficile toxins in patients with pseudomembranous colitis and antibiotic associated diarrhoea. J Immunol Methods. 1983;60:341–350. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyne L, Warny M, Qamar A, et al. Asymptomatic carriage of Clostridium difficile and serum levels of IgG antibody against toxin A. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:391–396. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pirofsky B, Campbell SM, Montanaro A. Individual patient variations in the kinetics of intravenous immune globulin administration. J Clin Immunol. 1982;2:7S–14S. doi: 10.1007/BF00918361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz U, Achiron A, Sherer Y, et al. Safety of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6:257–259. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itkin YM, Trujillo TC. Intravenous immunoglobulin-associated acute renal failure: case series and literature review. Pharmacotherapy. 2005 Jun;25:886–892. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.6.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aboudola S, Kotloff KL, Kyne L, et al. Clostridium difficile vaccine and serum immunoglobulin G antibody response to toxin A. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1608–1610. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1608-1610.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warny M, Fatimi A, Bostwick EF, et al. Bovine immunoglobulin concentrate (BIC) Clostridium difficile retains C. difficile toxin neutralising activity after passage through human stomach and small intestine. Gut. 1999;44:212–217. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunney RJ, Magee C, McNamara E, et al. Clostridium difficile colitis associated with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:2842–2846. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.11.2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tedesco FJ. Treatment of recurrent antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1982;77:220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]