Abstract

Background:

Knowing about risks of water contamination is the first step in making informed choices to protect our health and environment. Researchers were challenged with sharing water quality research information with local communities.

Objectives:

The purpose of this paper is to describe the formative evaluation used to develop and implement an Environmental Health Literacy summer camp and after-school water curriculum for Native American children in the 4th-6th grades.

Methods:

Community and university scientists, elders, and educators came together and co-developed a summer camp and after-school program for local youth to address the issues of water and its importance to the tribal community.

Lessons Learned:

Research partners must continually balance research needs with relationships and service to the community. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) helped to build trust and culturally center the intervention. The health literacy framework used to develop our curriculum also complimented our CBPR approach and may benefit other partnerships.

Conclusions:

Project partners built upon the mutual commitment to ‘do what we say we will do’ within the community context. Using the CBPR approach provided a strong framework for the collaboration necessary for this project. Trust relationships were key to the successes experienced during the development, implementation, and multiple revisions of this intervention.

Keywords: environmental health literacy, Native American children, water quality education, community-university partnerships, intervention development

Clean, healthy water is an essential element for life. Respecting and protecting this resource will become the responsibility of the children of today. For a group of tribal elders and researchers on one northern plains reservation, the passing down of knowledge and respect of water has become a priority. A decade of tribally-directed water quality research on surface and groundwater within the Apsáalooke (Crow) Nation reservation revealed potential threats to the health of the reservation’s water sources and communities.1−6 Studies conducted through collaboration of the Crow Environmental Health Steering Committee (CEHSC), and tribal college and university partners beginning as early as 2007 revealed levels of Escherichia coli that made the water unsafe for swimming and raised concern about the potential for other microbial contaminants that pose health risks such as Cryptosporidium.6 Cummins et al. (2010) also reported community member concerns of children contracting Shigellosis during the summer months, which they related to swimming in the local rivers. More recent studies of well water in homes within the tribal reservation have also revealed some wells are contaminated with uranium3, and contained other analytes such as manganese, nitrates, arsenic, or microbial contamination that made over half of those tested wells unsafe for drinking (personal communication, CEHSC member, 7/13/2016).

Knowing about risks of water contamination is the first step in making informed choices to protect our health and environment. However, warnings to limit contact with potentially contaminated water may conflict with practical economic and resource constraints3 and cultural understandings of health and wellness of tribal people.1–3,5 To address this challenge, tribal researchers and elders called for a community-based participatory research (CBPR) partnership with a Native researcher (Crow Tribal member, second author) at a nearby state university to find a way to disseminate water-related information within this community cultural context.

In early project planning meetings, the CEHSC, and the first two authors of this paper met and identified the lack of environmental health knowledge within the local communities as an area of concern. The group also cited examples within the community where children had been effective in previous campaigns for spreading information about health effects of smoking and the importance of seat belt use. We hypothesized that extended family structures might enhance the diffusion of the water quality information and provide sustained levels of change as children adopted and developed more conscious attitudes and behaviors regarding water quality and protection. The purpose of this paper is to describe the formative evaluation used to develop and implement the Guardians of the Living Water Environmental Health Literacy summer camp and after-school water curriculum for Native American (NA) children in the 4th-6th grades.

METHODS

Partnership

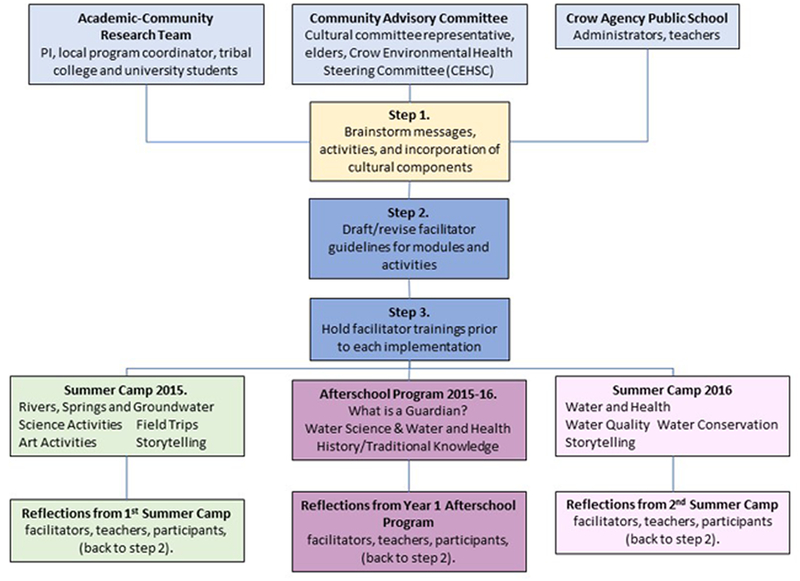

This CBPR project brought together a well-established, reservation-based research group—the Crow Environmental Health Steering Committee (CEHSC)—an academic research team composed of a university faculty (Crow tribal member), a local tribal member project coordinator, several Native and non-Native university and tribal college student interns; a tribal culture committee representative; and a local elementary school administrator to establish the Guardians of the Living Water Environmental Health Literacy Project (GLWP), and the current GLWP committee. In 2014, this collaborative research group embarked on a journey, using principles of CBPR, to plan, develop and implement week-long summer camps and after-school program aimed to increase levels of environmental health literacy (EHL) of local NA 4th-6th grade students. This project received approval by the Montana State University Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the IRB at Little Big Horn College. The university and community committee members continue to meet monthly to discuss the progress, challenges, and successes of this project. The committee oversees camp planning, including referrals of local guest speakers, and have actively participated in presentations, publications, and in facilitating activities during the camps. Figure 1 illustrates the main groups in the collaboration and the iterative process of curriculum development in this project.

Figure 1. Collaborative Partners and Curriculum Development Process.

Conceptual Framework

The development of the Guardians of the Living Water intervention was guided by CBPR principles7–10 utilizing iterative participation throughout (see Figure 1). The premise of the program was that 4th-6th grade camp participants assume the role of ‘Guardians of the Living Water’, be responsible for learning and sharing information about water, and become role models for respecting and protecting water in their communities. It was important to all partners in this project to use tribal stories and knowledge, to incorporate research-based local water quality information,1–6 and to focus on the development of interest, understanding, and skills within the tribe’s children regarding the holistic importance and significance of water to the tribal community.

This intervention was developed based on environmental health literacy (EHL) and children as agents of change models.11–14 These models aided in selecting and designing the curriculum components to deliver water-related information that students could share with family, friends, and the community. Since lay-educators implemented the intervention, we relied on published curriculum materials, and tapped into the rich tribal community resources such as local professionals and elders to teach activities, tell stories, and promote the importance of water and how to protect water.

In broad terms, environmental health literacy (EHL) focuses on educating individuals about the environment, its relevance to human health, and the actions one can take to reduce health risks and protect the environment.11–12 The goal of the GLWP is to improve EHL among the tribe’s children by focusing on the development of three levels of EHL (functional, interactive, and critical) adapted from Nutbeam’s heath literacy model.12 The model proved to be central to our ability to operationalize EHL and align our curriculum objectives and measures to help students move beyond science knowledge to interactive and action-focused activities.

The children as agents of change model13−14also impacted the development of the intervention. Messages and knowledge needed to be translatable to the community through the students participating in this study. That meant first finding out if the children could be that agent within the context of the tribal culture and community/family structure. Our intervention was developed and implemented in a way that would help us test that idea.

Intervention Development

The CEHSC and university research team spent considerable time conceptualizing how to translate, teach, and share information about water quality and the importance of water to, and through, the student participants in this program. Tying in the previous water quality work1–6 to be presented to and distributed by young students proved to be a formidable challenge. Much of the work done previously by the CEHSC was beyond the scope of this age level.1–6 Once the messages were drafted and agreed upon by the GLWP committee, the PI and students searched existing environmental and water curricula to provide knowledge and skills related to those messages, and looked at several other projects that utilized the children as agent of change model.1–14,16–20 After discussion of options, Project WET15 was selected and approved by the GLWP committee. Project WET, (Water Education for Teachers) is a foundation based in Montana that develops and publishes experiential science-based water education resource materials and provides training workshops for formal and informal educators.15 This material was a good fit based on ease of use and availability of local training opportunities that provided our facilitators access to the published materials to implement the intervention.

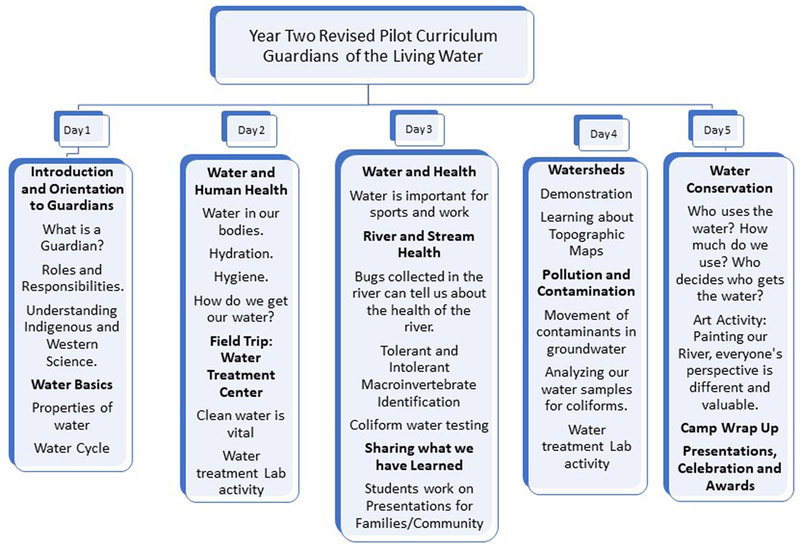

The initial intervention draft contained multiple modules: Introduction and Orientation to Guardians of the Living Water; Rivers and Springs; Wells and Groundwater, Water Treatment; Policy Implications and Sharing information. Each module included similar components: learning objectives; experiential objectives; art-based activities and sharing activities. Despite multiple iterative revisions however, the initial curriculum model ended up being too large to cover during a five-day camp, so we selected some activities from these modules to try out at the first summer camp. Work continued throughout the first two years of development to refine these messages and activities. The messages were eventually simplified for the 2016 summer camp to broadly cover 1) respecting water 2) water and human health 3) water can be contaminated, and 4) sharing the responsibility for conserving water. (see Figure 2.)

Figure 2. 2016 Guardians of the Living Water Camp Activity Schedule.

Four main messages were emphasized through activities over the five-day camp: Water, affects Human Health, Water can be Contaminated, and Respondibility for Conserving Water.

Facilitator Training

Trainings for staff and student interns became an important part of the development of the intervention activities. Prior to the first summer camp, three tribal college and three university team members attended a formal Project WET15 training, which also provided the project access to their full curriculum materials. Once we developed the first draft of camp activities, the PI and graduate students provided a three-day face-to-face training for camp facilitators that included information on the goals of the program, CBPR, basic water science, the research from the tribal community and required lab safety training. In addition, the facilitators conducted a walk-through of the planned activities for the camp, and attended an on-site training provided by a member of the CEHSC on how to conduct a river health assessment. Final revisions to the planned activities were completed prior to the 2015 summer camp based on feedback provided during these trainings. Ten facilitators completed an additional three-day training prior to the second summer camp in 2016. The second facilitator training session included the same topics as previous trainings, however, based on teacher/facilitator recommendations, activities were refined to provide more focused practice on delivery and learning objectives.

Curriculum Delivery

The curriculum was delivered first, through an annual five-day, M-F, 9AM to 4PM summer camp, and then through after-school sessions, both held at the local elementary school and at various important water-related locations within the reservation. In the first camp, university graduate students facilitated most activities, while tribal college interns and the local program coordinator were main facilitators for the after-school sessions, and the two teams shared responsibility for teaching the activities in the second camp. The after-school phase of the intervention consisted of 12 two-hour sessions (3:30PM-5:30PM). Sessions were held in an informal classroom setting at the elementary school each month throughout the 2015–2016 school year. The community partners were clear that our intervention should not add to the workload of teachers, so, we did not implement this intervention within the formal classroom, but rather compensated two participating teachers for their professional insight and observational feedback. The activities piloted at the 2015 summer camp were used for these sessions, with the addition of greater focus on the concept of being a Guardian, and incorporation of tribal language activities. Qualitative facilitator and teacher feedback was collected and used to refine activities for the next summer camp.

Guest speakers were incorporated throughout the camp and after-school sessions to enhance the participants understanding of the connection between water and health, history, and culture of the Apsáalooke people. Newsletters were sent home daily with the participants attending the camps and after-school sessions to encourage them to share what they learned with family members. In addition to the curriculum activities and field trips, daily activities at the camps included free breakfast and lunch provided by the school, and snacks provided by the project. The project provided snacks and dinner for the after-school sessions.

All participants were NA and were in the 4th, 5th or 6th grade. Most of the participants were from the local community, however some traveled from neighboring communities to participate in the camps. The camps were planned to accommodate up to 50 participants; however, the first camp had 22 participants on the first day of camp and 18 participants that completed the full camp. In the second year, fewer participants were recruited, with 14 participants attending the first day and nine completing the full week. Lower recruitment was mainly due to unanticipated scheduling conflicts with other community events. During the 2015–2016 after-school program, we initially recruited 24 participants, however only 12 participants attended at least 75% of the 12 sessions. Again, our after-school sessions competed with other family and community events. For example, basketball is very popular with this age group and even though the principal negotiated an attendance policy with the basketball coach we still lost participants.

Formative Evaluation

Following each day of the camps and at the end of the school year, facilitators met and reflected on the day’s activities, and provided a written reflection about the experience. Reflection meetings were also held with local teachers and GLWP committee members for additional feedback. We conducted interviews with participants at the end of the camp and asked what they liked and disliked. Four main themes resulted from the reflection sessions and are briefly described below. Relevant comments and resulting year two revisions are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of Post-Camp Reflection Meetings.

| Recommendation Categories | Reflection Evaluation Comments | Resulting Changes to Year 2 Curriculum |

|---|---|---|

| Terminology in Activity and Assessments |

The language seems to be a problem. Students may not have the opportunity to show what they really learned because the wording [in pre-post-tests] of the survey questions were confusing to some of the kids. [It’s] like taking an exam on something you know, but the questions are in a foreign language, so you don’t give the right answers—Crow Agency School (CAS) Teacher “Some of the terminology was over their heads”—Camp Facilitator “the real real big words were confusing and hard to read”—Camp Participant |

Team reviewed and revised all activities and assessments to make terminology more appropriate for this age group. |

| Introduce Fewer New Concepts |

“Have specific learning objectives for each day. Reinforce key messages each day. Review previous day’s messages in the morning”—CAS Teacher Don’t introduce too much at once or introduce a lot of new or difficult material at the end of a day or the end of a week. The end of day or program should be a celebration of what they learned. Not a party, but review in a way that highlights the student’s achievements—CAS Teacher “Tying in speakers more directly with activities, and giving the speakers more guidance about what activities were going on that day would help align their talks with what the students are learning”— GLWP Committee Member |

The number of topics covered were reduced to four main messages in Year Two. Guest speakers, activities and take-home activities were better aligned to reinforce these messages. |

| Reinforce Information in Multiple Ways |

“Keep the activities and games interactive, multimedia or hands on”—Camp Facilitator “I liked when we’re, like we look at the bugs.”—Camp Participant Using Native stories, build on the cultural practices of storytelling and developing listening skills. Then also give them opportunities to write draw, or talk about what they understand and learned…make sure the got it right, and are not leaving with misinformation—CAS Teacher “More consistent incorporation and reinforcement of cultural and tribal knowledge throughout the activities would enhance the program”—GLWP Steering Committee Member “I had fun and we got to go to that spring place and that guy told us our stories. And I got to make stuff”—Camp Participant |

Students were given more opportunities to hear stories, read, watch video clips, and to hands-on activities such as creating art, videos, posters to enhance the activities and make connections between classroom activities and real-world experiences. More guest speakers were invited to share about topics directly related to science-based activities, and helped students learn Crow names of rivers and relevant places. The speakers also related more directly to the roles, responsibility, and expectations of what Guardians should be and do within the community. |

| Time and Classroom Management |

“Make sure everyone (facilitators) knows the activities we are doing, the main messages and concepts of the activities”—CAS Teacher “Incorporate clans and clan leaders…when students have issues questions they can go back to their clan leader who is responsible for them”—Camp Facilitator “Have each person in the group have a role so they don’t just sit back and do nothing”—Camp Facilitator “Assign project staff (facilitators) specific daily tasks like attendance, food, icebreakers, data collection, photography”—Camp Facilitator “Life circumstance differences may lead to different levels of respect for education and teachers, need to start out establishing and talking about respect and acceptable behaviors and continually reinforce it”— CAS Teacher |

The facilitator training guide was revised so the learning objectives for each activity were highlighted and were reviewed for alignment with the assessments for each activity. Additional facilitators hired, and all staff were assigned specific tasks as needed and scheduled breaks for facilitators and participants were added into the schedule to keep activities moving at an appropriate pace throughout the day. More facilitators enabled us to establish smaller permanent groups that allowed more individual attention to participants. We developed a short contract for parents and students to make sure both understood the expectations of the camp. |

1). Terminology in Activities and Assessments.

Teachers, facilitators, and participants commented that some participants struggled with understanding certain terminology. This was believed to be the result of cultural language differences and the complexity of language used without adequate explanation. All activities and assessment instruments were revised to be more understandable to the students.

2). Fewer New Concepts Each Day.

Facilitators and teachers recommended reducing the number of new topics introduced each day and within the week. This required an extensive revision of camp planning, however as we focused more on learning objectives within activities, it became easier to reinforce the messages and align our activities and speakers.

3). Reinforce Information in Multiple Ways.

Other comments suggested development of more innovative ways to reinforce the messages each day. We focused on activities that captured the attention of participants, and could be paired with traditional stories, or trips to local sites. The addition of more local facilitators and speakers, and Crow language words into some activities was also incorporated.

4). Time and Classroom Management.

Recommendations for one-on-one attention toward the participants and assigning facilitators to specific tasks addressed time management challenges. The incorporation of clan leaders allowed planning the activities around a specific number of groups, who would stay together throughout the week, avoiding the need to continually take time to regroup the participants and reduced the “getting acquainted” period for the participants. The GLWP team collaborated to incorporate many recommendations into a revised guide and schedule for the year two camp. Figure 2 illustrates the resulting year two camp activity schedule.

LESSONS LEARNED

This project has been a practical experience in bringing together several partners to translate water quality research, tribal knowledge, and environmental health knowledge into messages appropriate for 4th-6th grade students. Through our process of developing and piloting the intervention in two successive summer camps and an after-school program, we have several valuable lessons learned along the way.

First, the CBPR approach to co-designing a project involves humility, and flexibility. Based on initial meetings with community partners, the university team initially proposed an idea of sharing information within the adult population. However, in subsequent meetings, this idea evolved when the committee brought up their interest in using children as a means for reaching adults. This novel approach interested the academic partners; however, as the team stood they had limited experience working with children. Although we made sure that several educators comprised the steering committee and we met monthly to review progress on development of the project, the academic partners struggled to meet what they perceived as the community partners’ expectations. This resulted in a long and laborious process of going from a very science education intensive curriculum design that frankly overwhelmed us as facilitators, to the more recent interactive and action-based curriculum. It had taken much of the first two years of work to get to this level of trust and understanding to call for a shift in our planning path. However, this changed the dynamic of our partnership for the better, and we feel better serves both our interests and the overall goals of the community.

In the first year, the task of translating water quality research into a children-focused camp became too academic and did not adequately reflect the public health and health literacy focus that we were interested in and were reflected in our conceptual framework of EHL and children as agents of change models. The post camp reflections led us to rethink our approach and forced us to come up with a more workable operational definition of environmental health literacy to help the committee see the difference between EHL and strictly science education. We went through several iterations of how we could apply a health literacy framework to our intervention development, but found that Nutbeam’s (2008) health literacy model was most appropriate for helping us to shift the focus of the program from focusing only on knowledge acquisition, to also incorporating the interactive and critical functions of EHL that may create the desired outcomes of change and action within the participants and broader community. Nutbeam’s framework draws directly from Paulo Freire21 and is highly compatible with CBPR approaches to research that extend from personal behaviors to enhancing one’s well-being to social action to influence the determinants of health. Our adoption of Nutbeam’s framework was compatible with our desire to promote children as agents of change. Other CBPR partnerships working to promote efficacious change in communities may also benefit from using Nutbeam’s framework to guide intervention development.

Additional challenges related to fulfilment of responsibility to community included our decision to jump into the first camp when we had not yet fully developed the framework for the EHL model. However, our community partners had obtained funding for the camp and we felt a responsibility to demonstrate our commitment to the community. The project had also experienced several serious setbacks in our timeline. For example, because of staff turnover, we did not have an opportunity to provide training for newly hired tribal college interns prior to the start of the camp, so they were unable to facilitate any of the activities. Since we did not have adequate time to prepare and develop the research-component, the first camp was essentially a pre-pilot testing of some of the activities and knowledge assessment instruments. While this was not ideal from a research perspective, it proved to be important for our work from a relationship building perspective. It was important for us to demonstrate our commitment to the community. This example illustrates how research partners must continually balance research needs with relationships and service to the community.

CONCLUSION

This project brought together a diverse group of individuals with a common goal of passing on knowledge and understanding of water and its importance to individuals and communities within the Crow Agency community. Partners recognized strengths and challenges in working across scientific and social-behavioral disciplines. Using the CBPR approach provided a strong framework for the collaboration necessary for this project. Trust relationships were key to the successes experienced during the development, implementation, and multiple revisions of this intervention. This trust was developed through commitment of all members toward the goals of the program: to pass on the knowledge and understanding of water to the children of the community. The ability of the group to come together to provide the first camp under difficult time restraint and personnel challenges is just one example of the commitment to “do what we say we will do” within the community context. The relationships and lessons learned will continue to develop as we move to the final stages of this project and begin the planning of future collaborations within this community.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the participants and their families, as well as our many partners for their assistance with this project: Grant Bull Tail*, Lisa Stevens, Kristen Merchant, Jonna Chavez, Frederica Lefthand*, Winters Plain Bull, Melvin Ware, Eduardo Nunez, SaRayna Stops, Bruce Goes Ahead Pretty, Christine Martin, Hannah Rieth, Jess Malokovich, Kendra Veo. Crow Environmental Health Steering Committee: Sara L. Young*, Myra Lefthand, Dr. Mari Eggers, Robin Stewart, David Small*, John Doyle*, Ada L. Bends. Consultants and Advisors: Dr. Suzanne Held and Dr. Rima Rudd. Special Thanks to all the local community professionals, elders and educators who shared your knowledge and experience with our project!

*Also, on the Guardians of Living Water Steering Committee

This project was made possible by the Center for American Indian and Rural Health Equity Montana (CAIRHE), grant P20GM104417[PI: Alex Adams], sponsored by the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences. Research reported in this publication was also supported by Montana INBRE Graduate Fellowship grant sponsored by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20GM103474[PI: Brian Bothner]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. 2015 Summer Camp funding also provided through a grant from Phillips 66 and the Crow Tribe to Crow Agency Public School.

Contributor Information

Deborah LaVeaux, Department of Education, Montana State University.

Vanessa W. Simonds, Department of Health and Human Development, Montana State University.

Velma Picket, Environmental Health Literacy Program, Little Big Horn College.

Jason Cummins, Crow Agency Public School.

Erin Calkins, Department of Health and Human Development.

References

- 1.Cummins C, Doyle J, Kindness L, Lefthand MJ, Don’t Walk UB, Bends A, Broadaway SC, Camper AK, Fitch R, Ford TE, Hamner S. Community-based participatory research in Indian country: Improving health through water quality research and awareness. Family & Community Health. 2010. July;33(3):166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle JT, Redsteer MH, Eggers MJ. Exploring effects of climate change on Northern Plains American Indian health. Climatic Change. 2013. October 1;120(3):643–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eggers MJ, Moore-Nall AL, Doyle JT, Lefthand MJ, Young SL, Bends AL, Camper AK. Potential health risks from uranium in home well water: An investigation by the Apsaalooke (Crow) tribal research group. Geosciences. 2015. March 20;5(1):67–94. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamner S, Broadaway SC, Berg E, Stettner S, Pyle BH, Big Man N, Old Elk J, Eggers MJ, Doyle J, Kindness L, Good Luck B. Detection and source tracking of Escherichia coli, harboring intimin and Shiga toxin genes, isolated from the Little Bighorn River, Montana. International Journal of Environmental Health Research. 2014. July 4;24(4):341–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormick AKHG, Pease B, Lefthand MJ, Eggers MJ, McCleary T, Felicia DL, Camper AK. Water, A resource for health: Understanding impacts of water contamination in a Native American community Roundtable presentation, American Public Health Association Conference; October 27–31; San Francisco, CA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ford TE, Eggers MJ, Old Coyote TJ, Good Luck B and Felicia DL. Additional contributors: Doyle JT, Kindness L, Leider A, Moore-Nall A, Dietrich E, Camper AK. Comprehensive community-based risk assessment of exposure to water-borne contaminants on the Crow Reservation. EPA Tribal Environmental Health Research Program Webinar. October 17, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaVeaux D, Christopher S. Contextualizing CBPR: Key principles of CBPR meet the Indigenous research context. Pimatisiwin. 2009. June 1;7(1):1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holkup PA, Tripp-Reimer T, Salois EM, Weinert C. Community-based participatory research: an approach to intervention research with a Native American community. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science 2004. July;27(3):162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ablah E, Brown J, Carroll B., Bronleewe T. A Community-Based Participatory Research Approach to Identifying Environmental Concerns. Journal of Environmental Health 2016. 12;79(5):14–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJ, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles. Community-based Participatory Research for Health. 2003; 1:53–76. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finn S, O’Fallon L. The emergence of environmental health literacy—from its roots to its future potential. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2017. April;125(4):495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nutbeam D The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science & Medicine. 2008. December 31;67(12):2072–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onyango-Ouma W, Aagaard-Hansen J, Jensen BB. The potential of schoolchildren as health change agents in rural western Kenya. Social Science & Medicine. 2005. October 31;61(8):1711–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamo N, Carlson M, Brennan RT, Earls F. Young citizens as health agents: Use of drama in promoting community efficacy for HIV/AIDS. American Journal of Public Health. 2008. February;98(2):201–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Project WET Foundation. 2015. www.projectwet.org [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown B, Noonan C, Harris KJ, Parker M, Gaskill S, Ricci C, Cobbs G, Gress S. Developing and piloting the Journey to Native Youth health program in Northern Plains Indian communities. The Diabetes Educator. 2013. January;39(1):109–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown BD, Harris KJ, Harris JL, Parker M, Ricci C, Noonan C. Translating the diabetes prevention program for Northern Plains Indian youth through community-based participatory research methods. The Diabetes Educator. 2010. November 1;36(6):924–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tovar A, Vikre EK, Gute DM, et al. Development of the Live Well curriculum for recent immigrants: A community-based participatory approach. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2012;6(2):195–204. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izumi BT, Peden AM, Hallman JA, Barberis D, Stott B, Nimz S, Ries WR, Capello A. A community-based participatory research approach to developing the Harvest for Healthy Kids curriculum. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2013;7(4):379–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaRowe TL, Wubben DP, Cronin KA, Vannatter M, & Adams AK. Development of a culturally appropriate, home-based nutrition and physical activity curriculum for Wisconsin American Indian families. Prevention of Chronic Disease (2007). 4 (4); A109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freire P Pedagogy of the Oppressed (30th Anniversary Edition) (Ramos MB, Trans.). (2000). New York, NY: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. [Google Scholar]