Abstract

Combining a ketogenic diet with standard chemotherapeutic and radiotherapeutic options may help improve tumor response, although more research is needed.

As early as 500 bc, fasting was used as an effective treatment for many medical ailments. Fasting continued into modern times, and in 1910, Guelpa and Marie proposed fasting as an antiepilepsy treatment. In 1921, Woodyatt noted that starvation or use of high-fat, low-carbohydrate diets in individuals with no significant medical comorbidities yielded acetone and β-hydroxybutyrate, 2 energy sources produced by the liver in the absence of glucose. A low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet was thought to be an alternative to fasting or starvation, having many of the same desired effects while continuing to nourish healthy cells. The term ketogenic diet (KD) was later coined by Wilder and Peterman, who formulated the fat-to-carbohydrate ratio that is still used today: 1 g protein per kg of body weight in children and 10 to 15 g carbohydrates daily, and fat for the remainder of calories. Both investigators reported that this diet improved their patients’ mentation and cognition.1

Use of the KD as an adjuvant to cancer therapy also began to emerge. In 1922, Braunstein noted that glucose disappeared from the urine of patients with diabetes after they were diagnosed with cancer, suggesting that glucose is recruited to cancerous areas where it is consumed at higher than normal rates. During that same time, Nobel laureate Otto Warburg found that cancer cells thrive on glycolysis, producing high lactate levels, even in the presence of abundant oxygen. Warburg conducted many in vitro and animal experiments demonstrating this outcome, known as the Warburg effect.

By the mid-20th century, KD use in epilepsy treatment and cancer research had waned. However, in the mid-to-late 1990s, with the establishment of the Charlie Foundation, the diet slowly started regaining recognition. 1 Results of many in vitro and animal studies were reported, and human data also began to accumulate.

MECHANISMS OF ACTION

Glucose normally stimulates pancreatic β cells to release insulin, which allows glucose to enter cells and provide energy. With high carbohydrate and glucose intake, the pancreas increasingly secretes more insulin, which promotes the interaction of growth hormone receptors and growth hormones to produce insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) in the liver—promoting cell growth and proliferation, which can be detrimental to patients with cancer. Overexpression of glucose transporters 1 and 3 (Glut-1, Glut-3) also occurs in many cancers and corresponds to the degree of glucose uptake in aggressive tumors, as seen on positron emission tomography (PET).2 Overexpression of hexokinase, the rate-limiting enzyme of glycolysis, further drives production of pyruvate and lactate, which cause reactive oxygen species damage. Translocation of the hexokinase rate-limiting enzyme from the cytosol into the outer mitochondrial membrane, where it interacts with voltage-dependent anion channels, can disrupt caspase-dependent cytochrome release, which suppresses the apoptotic pathways of cancer cells and makes cancer more resistant to chemotherapy.3

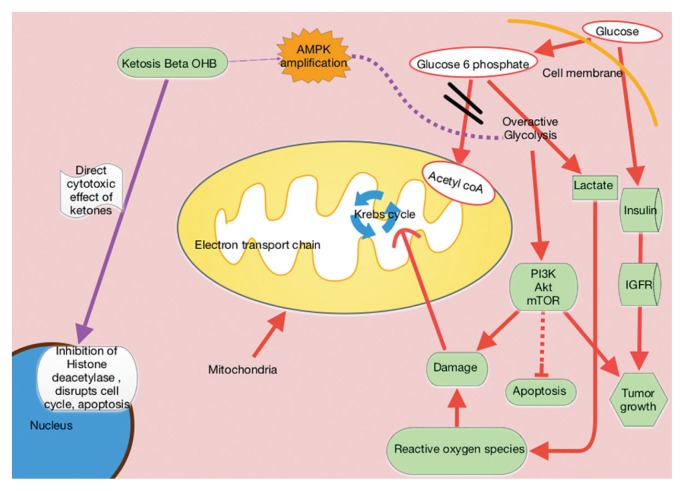

When glucose is scarce, the body senses the need to make an alternative form of energy for cells. The liver then produces ketones and fatty acids, which provide for normal cells but do not benefit cancer cells. Cancer cells have dysfunctional mitochondria and possibly electron transport chain defects, which disrupt normal adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production from the mitochondria. The result is that the cancer cells become heavily dependent on ATP coming from the less efficient process of glycolysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ketogenic Diet Metabolic Pathways

Ketogenic diets mimic the fasting state, wherein the body responds to the lack of glucose by producing ketones for energy. Excess lactate production, which is part of the Warburg effect, compensates for ATP production defects caused by dysfunctional mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation.2,4 The resulting tumor dependence on glucose can be exploited with KD use. Ketogenic diets selectively starve tumors by providing the fat and protein that otherwise could not be used by glucose-dependent tumor cells.

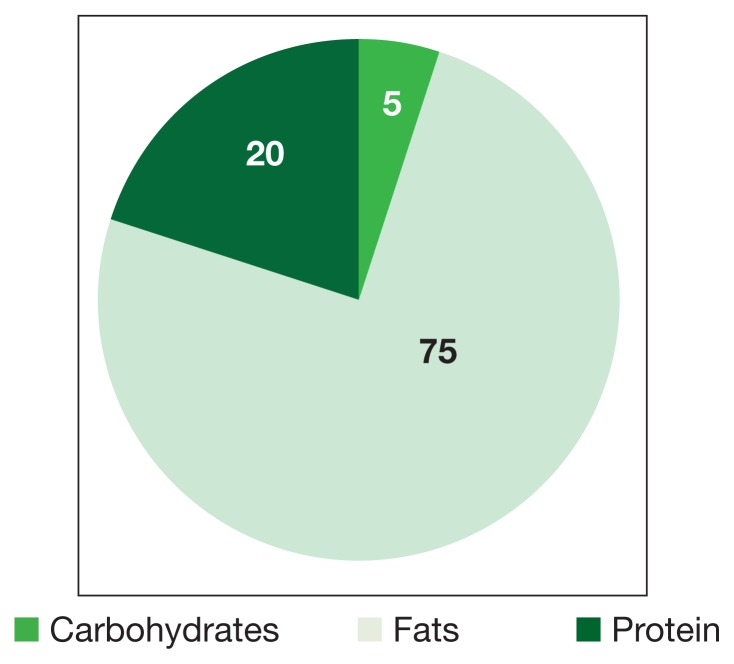

In KDs, the 4:1 ratio of high fat to low carbohydrates mimics the metabolic effects of starvation (Figure 2). These diets slow cancer by inhibiting insulin/IGF and downstream intracellular signaling pathways, such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). Ketogenic diets also amplify adenosine monophosphate—activated protein kinase (AMPK), which inhibits aerobic glycolysis and suppresses tumor proliferation, invasion, and migration. Mouse models of metastatic cancer show that exogenous ketones themselves have direct cytotoxic effects on tumor viability.5 β-hydroxybutyrate can modify chromatin by binding to and thereby inhibiting histone deacetylase, ultimately repressing transcription and curbing cancer cell proliferation (Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Macronutrient Composition of Ketogenic Diets

KETOGENIC DIET BENEFITS

There are concerns about providing protein to patients who are at risk for renal problems. However, mouse models of diabetic nephropathy showed improved renal function with KD use. The hypothesis was that KD use, which produces prolonged elevated 3-β-hydroxybutyric acid levels, also reduces molecular responses to glucose and consequently reduces renal damage.6 Use of the diet also reduced pain and inflammation in both juvenile and adult rats. Mechanisms of action were thought to be reduced reactive oxygen species and increased central adenosine levels.7,8

ADVERSE EFFECTS

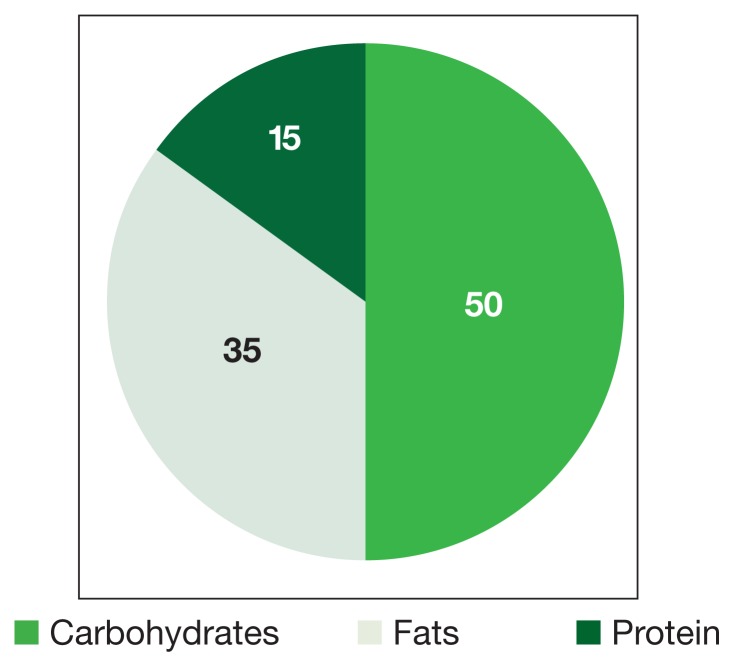

Dieting is of concern to cancer patients worried about additional weight loss. The standard diet is made up predominantly of carbohydrates and is high in caloric value (Figure 3). Beck and Tisdale investigated the effect of KD use on delaying cachexia in mouse models of colon carcinoma. They found that dieting was more effective than insulin in reversing weight loss and had the added effect of reducing tumor size.7 Moreover, Tisdale and colleagues found that KD use in cachectic cancer patients could promote weight gain.8

Figure 3.

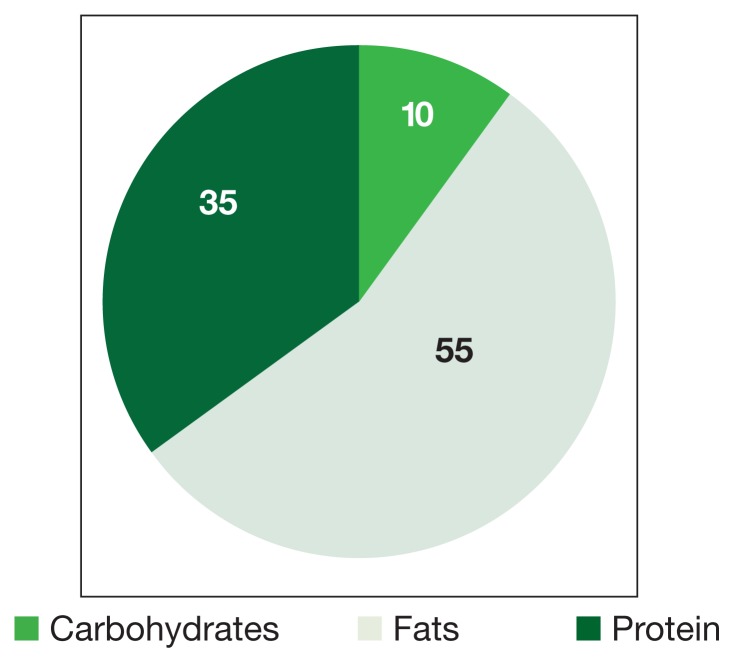

Macronutrient Composition of Modified Ketogenic (Atkins) Diets

A possible explanation is that healthy tissue nutrition selectively delays tumor growth, while cancer cells are deprived of nutrition (carbohydrates). A therapeutic weight plateau should follow initial weight loss with KD, in contrast to pathologic rapid weight loss in non-KD patients. 9 Kidney stones, gout, and symptomatic hypoglycemia were also potential expected adverse effects (AEs).

Case Reports

In 1962, the New York Department of Mental Hygiene published an article about 2 women whose metastatic cancers disappeared after a series of daily hypoglycemia-induced insulin comas (brief and reversible). These patients could not undergo conventional electric shock therapy, hence, the medically induced psychotherapy. Not only did their psychotic and depressive symptoms resolve, but their cancers (grossly visible cervical cancer and metastatic melanoma) became undetectable as early as 2 months into treatment.10 Zuccoli and colleagues reported on a glioblastoma that was effectively treated with temozolomide oral chemotherapy after the patient was weaned off steroids. The patient had a radiographic response and good tumor control for about a year, before discontinuing the diet. She transitioned to chemotherapy, which included bevacizumab (antivascular endothelial growth factor), but the disease progressed and she died.11 In addition, during 8 weeks of ketogenic dieting, 2 pediatric female astrocytoma patients experienced improved mood and showed decreased glucose uptake on PET-computed tomography (PET-CT) of their tumor sites. One of these patients continued the diet and remained disease-free another 12 months.12 These early case reports provide compelling evidence for further research into the role of glucose metabolism in cancer treatment.

CURRENT RESEARCH

Compared with normal mice, tumor-bearing mice placed on a low-carbohydrate diet had lower glucose, insulin, and lactic acid levels.4 An in vivo microdialysis study of patients with head and neck cancers found decreased lactic acid levels in the tumor tissues after a 4-day KD.13 Most early studies and case reports involving KD in cancer focused on brain tumors.11,14–16 Human clinical studies on this diet in cancer care were limited to small, nonrandomized, brief trials (4–12 weeks) or single case studies (Table).11,17–20

Table.

Low-Carbohydrate Pilot Safety and Tolerability Trials

| Trial | Diet Duration | Patients Enrolled, n |

Patients Tolerated Diet, n |

Patients That Quit Early or Unable to Diet Due to Poor Health, n | Early Deaths, n | Stable Disease, n | Progressive Disease, n | Partial Response, n | Adverse Effects | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECHARGE: Fine and colleagues17 | 4 wk | 10 Breast Ovarian/fallopian Colorectal Lung Esophageal |

5 | 5 | 0 | 5 (4 wk) | 4 | 1 | Mean weight loss: 4.1% (P = .45) No adverse effects |

Modified Atkins diet: 20 carbohydrate g/d Unlimited protein 2 cups of vegetables per day Ketosis correlated with standardized uptake value on positron emission tomography–computed tomography Stable disease correlated to 3-fold ketosis (P = .018) |

| ERGO: Rieger and colleagues18 | Until progression | 20 Relapsed glioblastoma |

17 | 3 Poor intake | 0 | 0 | 17 1 minor response 2 patients with stable disease (6 wk) |

Seen only after salvage chemotherapy with or without radiation 8 patients total received salvage 1 complete response 5 partial responses |

Mean weight loss: 2.2% (statistically significant) 2 patients had grade 3 leucopenia No other grade 3 adverse effects |

60 carbohydrate g/d Low-carbohydrate diet and plant oils Unlimited calories Primary endpoint: % discontinuation of diet Secondary endpoints: safety, % achieving ketosis, quality of life 8 of the 17 patients with progressive disease underwent salvage chemotherapy and dietary changes, which resulted in 5 partial responses and 1 complete response Median overall survival with diet: 32 wk Median progression-free survival: 5 wk |

| Wuerzburg study: Schmidt and colleagues19 | 5–12 wk | 16 Utero-ovarian Breast Parotid Sarcoma Pancreas Thyroid Colon Lung |

5 (12 wk) 2 (6 wk) 2 (7 wk) 2 (8 wk) 1 (5 wk) 1 (4 wk) 3 (2 wk) |

3 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 0 | Mean weight loss: 2.9% (P < .05) No adverse effects |

Stable lipid and cholesterol profile 70 carbohydrate g/d Low-carbohydrate diet Oil-protein shakes as snacks |

| VA Pittsburgh safety trial: Tan and colleagues21 | 4–116 wk | 17 | 12 (≥ 2 wk) 11 (≥ 4 wk) 6 (≥ 8 wk) 4 (≥ 16 wk) |

6 Screen failures | 0 | 6 (4 wk) 6 (8 wk) 4 (16 wk) |

5 (4 wk) 1 voluntary withdrawal (8 wk) |

2 mixed responses (16 wk) 1 no evidence of disease status postmetastectomy |

Mean weight loss: 8% (P < .0001) 8 patients had grade 3 weight loss |

Modified Atkins diet: 20–40 carbohydrate g/d Primary endpoints: safety and feasibility Quality of life unchanged Ketosis did not correlate with glucose or weight loss |

Abbreviations: ERGO, ketogenic diet for recurrent glioblastoma; RECHARGE, Reduced Carbohydrates Against Resistant Growth Tumor.

Fine and colleagues conducted a 4-week feasibility study of the low-carbohydrate modified Atkins KD (≤ 20 g of carbohydrates daily) in PET-positive advanced cancer patients with solid tumors. There was a correlation between insulin levels and ketosis but not IGF. Stable disease or partial remission (measured standardized uptake value) on PET-CT correlated with 3-fold higher ketosis (but not weight loss or reduced caloric intake) relative to patients with progressive disease.17 In the ERGO trial, Rieger and colleagues studied 20 relapsed glioblastoma patients who were on KD supplemented with plant oils.18 Calories were unlimited. The primary endpoint was percentage of patients who discontinued the diet. Mean weight loss was significant, but quality of life (QOL) was maintained. The investigators also studied the effects of KD alone or combined with bevacizumab in a mouse glioblastoma model. In this mouse study, KD alone had no effect; however, it increased median survival from 52 to 58 days (P < .05) with bevacizumab.

In a pilot study, Schmidt and colleagues provided KD plus oil-protein shakes as snacks to 7 of 16 patients with a variety of advanced metastatic cancers. Mean weight loss was statistically significant, blood lipid or cholesterol levels remained stable, some QOL measures improved, and there were no severe AEs.19 Schwartz and colleagues reviewed the cases of 32 glioma patients treated with energy restricted KDs —5 from case reports, 19 from a clinical trial by Rieger and colleagues, and 8 from Champ.18,20,21 They also reported on 2 of their own glioma cases treated with the energy-restricted KD and studied tissues for expression of key ketolytic enzymes. Prolonged remission was noted from 4 months to more than 5 years in these case reports.20

The VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System safety that trial enrolled 17 patients, 11 of whom were evaluated. Mean weight loss was significant, and weight loss of ≥ 10% was noted in responders (stable or improved disease) compared with nonresponders. Three patients dieted longer than 16 weeks (survival, 80–116 weeks). One of these patients was alive at 121 weeks.22

The safety and feasibility data suggest that cancer patients can tolerate KD use. Investigators should consider combining the KD approach with standard treatment modalities, including chemotherapy and radiation.

Already investigators have conducted in vitro studies of the effect of gene expression of ketolytic and glycolytic enzymes within tumor tissue on KD response. Tumors expressing mutations in key mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation enzymes were more likely to respond to KD use than were tumors without mutations.16,23

Ongoing Clinical Trials

Duke University has initiated a randomized study (NCT00932672) of the Atkins diet and androgen deprivation therapy for patients with prostate cancer. Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center in Israel is recruiting previously treated chemoradiation patients with high-grade glial tumors for an open-label study (NCT01092247) of the efficacy of KD in preventing tumor growth and recurrence. St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center (Phoenix, AZ) is recruiting newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients for a phase 1/2 prospective trial (NCT02046187) involving upfront resection followed by KD with radiotherapy and concurrent temozolomide, followed by adjuvant temozolomide chemotherapy. The primary endpoint is number of patients with AEs and the secondary endpoints are overall survival, time to progression, and QOL. The University of Iowa is recruiting patients with prostate cancer and non-small cell lung cancer for 2 phase 1 studies (NCT01419483 and NCT01419587, respectively) involving KD using Nutritia KetoCal 4:1 (Gaithersburg, MD).

CONCLUSION

Data from case reports and trials suggest KD use is safe and tolerable for patients with cancer. Although it would be ideal to conduct a larger trial using a randomized therapeutic approach, the current emphasis on drug-based trials is a formidable obstacle. Other major obstacles are patient initiative and adherence. For now, investigators must work with anecdotal data. Examination of gene expression patterns in mitochondria and mutations in ketolytic and glycolytic enzymes may prove useful in selecting potentially responsive patients. Combining this dietary approach with standard chemotherapeutic and radiotherapeutic options may help improve tumor response, and further research is desperately needed.

Figure 4.

Macronutrient Composition of Standard Diets

Footnotes

Author disclosure

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wheless JW. History of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2008;49(suppl 8):3–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tian M, Zhang H, Nakasone Y, Mogi K, Endo K. Expression of Glut-1 and Glut-3 in untreated oral squamous cell carcinoma compared with FDG accumulation in a PET study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31(1):5–12. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1316-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pastorino JG, Hoek JB. Regulation of hexokinase binding to VDAC. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40(3):171–182. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9148-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho VW, Leung K, Hsu A, et al. A low carbohydrate, high protein diet slows tumor growth and prevents cancer initiation. Cancer Res. 2011;71(13):4484–4493. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poff AM, Ari C, Arnold P, Seyfried TN, D’Agostino DP. Ketone supplementation decreases tumor cell viability and prolongs survival of mice with metastatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(7):1711–1720. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poplawski MM, Mastaitis JW, Isoda F, Grosjean F, Zheng F, Mobbs CV. Reversal of diabetic nephropathy by a ketogenic diet. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck SA, Tisdale MJ. Effect of insulin on weight loss and tumour growth in a cachexia model. Br J Cancer. 1989;59(5):677–681. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tisdale MJ, Brennan RA, Fearon KC. Reduction of weight loss and tumour size in a cachexia model by a high fat diet. Br J Cancer. 1987;56(1):39–43. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan-Shalaby J, Seyfried T. Ketogenic diet in advanced cancer: a pilot feasibility and safety trial in the Veterans Affairs cancer patient population. J Clin Trials. 2013;3(4):149. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koroljow S. Two cases of malignant tumors with metastases apparently treated successfully with hypoglycemic coma. Psychiatr Q. 1962;36:261–270. doi: 10.1007/BF01586115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuccoli G, Marcello N, Pisanello A, et al. Metabolic management of glioblastoma multiforme using standard therapy together with a restricted ketogenic diet: case report. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2010;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nebeling LC, Miraldi F, Shurin SB, Lerner E. Effects of a ketogenic diet on tumor metabolism and nutritional status in pediatric oncology patients: two case reports. J Am Coll Nutr. 1995;14(2):202–208. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1995.10718495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masino SA, Ruskin DN. Ketogenic diets and pain. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(8):993–1001. doi: 10.1177/0883073813487595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maroon J, Bost J, Amos A, Zuccoli G. Restricted calorie ketogenic diet for the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(8):1002–1008. doi: 10.1177/0883073813488670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroeder U, Himpe B, Pries R, Vonthein R, Nitsch S, Wollenberg B. Decline of lactate in tumor tissue after ketogenic diet: in vivo microdialysis study in patients with head and neck cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2013;65(6):843–849. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2013.804579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang HT, Olson LK, Schwartz KA. Ketolytic and glycolytic enzymatic expression profiles in malignant gliomas: implication for ketogenic diet therapy. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2013;10(1):47. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-10-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fine EJ, Segal-Isaacson CJ, Feinman RD, et al. Targeting insulin inhibition as a metabolic therapy in advanced cancer: a pilot safety and feasibility dietary trial in 10 patients. Nutrition. 2012;28(10):1028–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rieger J, Bähr O, Maurer GD, et al. ERGO: a pilot study of ketogenic diet in recurrent glioblastoma. Int J Oncol. 2014;44(6):1843–1852. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2382. [published correction appears in Int J Oncol 2014; 45(6): 2605] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt M, Pfetzer N, Schwab M, Strauss I, Kämmerer U. Effects of a ketogenic diet on the quality of life in 16 patients with advanced cancer: a pilot trial. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2011;8(1):54. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-8-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz K, Chang HT, Nikolai M, et al. Treatment of glioma patients with ketogenic diets: report of two cases treated with an IRB-approved energy-restricted ketogenic diet protocol and review of the literature. Cancer Metab. 2015;3:3. doi: 10.1186/s40170-015-0129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Champ CE, Palmer JD, Volek JS, et al. Targeting metabolism with a ketogenic diet during the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2014;117(1):125–131. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan-Shalaby J, Carrick J, Edinger K, et al. Modified ketogenic diet in advanced malignancies—final results of a safety and feasibility trial within the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl) doi: 10.1186/s12986-016-0113-y. Abstract e23173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langbein S, Zerilli M, Zur Hausen A, et al. Expression of transketolase TKTL1 predicts colon and urothelial cancer patient survival: Warburg effect reinterpreted. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(4):578–585. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]