Abstract

Context

Prescription drugs are instrumental to managing and preventing chronic disease. Recent changes in cost-sharing could affect access to them.

Objective

To synthesize published evidence on the associations among cost-sharing features of prescription drug benefits and use of prescription drugs, use of nonpharmaceutical services, and health outcomes.

Data Sources

We searched PubMed for studies published in English between 1985 and 2006.

Study Selection & Data Extraction

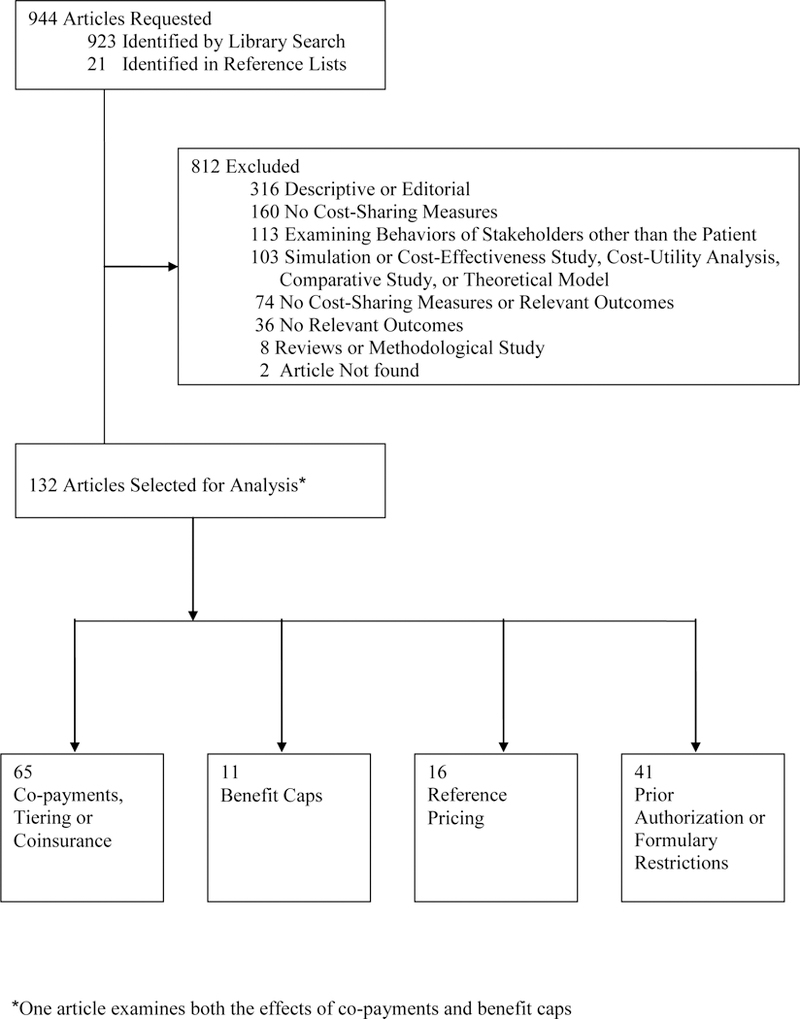

Among 923 articles found in the search, we identified 132 articles examining the associations between prescription drug plan cost-containment measures, including co-payments, tiering, or coinsurance (n = 65), pharmacy benefit caps or monthly prescription limits (n = 11), formulary restrictions (n = 41), and reference pricing (n = 16), and salient outcomes, including pharmacy utilization and spending, medical care utilization and spending, and health outcomes.

Data Synthesis

Increased cost-sharing is associated with lower rates of drug treatment, worse compliance among existing users, and more frequent discontinuation of therapy. For each 10% increase in cost-sharing, prescription drug spending falls by 2% to 6%, depending on the class of drugs and the patient’s condition. The reduction in use associated with a benefit cap, which limits either the coverage amount or the number of covered prescriptions, is consistent with other cost-sharing features. For some chronic conditions, higher cost-sharing is associated with increased use of medical services, at least for patients with congestive heart failure, lipid disorders, diabetes, and schizophrenia. While low-income groups may be more sensitive to increased cost-sharing, there is little evidence to support this contention.

Conclusions

Pharmacy benefit design represents an important public health tool for improving patient treatment and adherence. While increased cost-sharing is highly correlated with reductions in pharmacy use, the long-term consequences of benefit changes on health are still uncertain. guidance on conducting a systematic evidence review.

INTRODUCTION

Medical practice in the United States has changed dramatically in the last several decades, including an increase in use of prescription drugs. More and better-quality drugs are available to prevent and manage chronic illness, and these drugs reduce mortality, forestall complications, and make patients more productive.1 Thus, access to outpatient drugs is now a cornerstone of an efficient health care system.

But with recent increases in pharmacy spending, pharmacy benefit managers and health plans have adopted benefit changes designed to reduce pharmaceutical use or steer patients to less-expensive alternatives. The rapid proliferation of mail-order pharmacies, mandatory generic substitution, coinsurance plans, and multitiered formularies has transformed the benefit landscape. In this review, we analyze how the salient cost-sharing features of prescription drug benefits may affect access to prescription drugs and synthesize what is known about how these features may affect medical spending and health outcomes.

SCOPE OF BENEFIT CHANGES

Most beneficiaries are now covered by incentive-based formularies in which drugs are assigned to one of several tiers based on their cost to the health plan, the number of close substitutes, and other factors.2 For example, generics, preferred brands, and nonpreferred brands might have co-payments of $5, $15, and $35, respectively. In contrast, plans may require beneficiaries to pay coinsurance—ie, a percentage of the total cost of the dispensed prescription. The purpose of tiered co-payments and coinsurance is to give beneficiaries an incentive to use generic or low-cost brand-name medications and to encourage manufacturers to offer price discounts in exchange for inclusion of their brand-name products in a preferred tier. By 2005, most workers with employer-sponsored coverage (74%) were enrolled in plans with 3 or more tiers, nearly 3 times the rate in 2000 (27%).3

Some plans also impose benefit caps that limit either the coverage amount or the number of covered prescriptions. For example, the standard Medicare Part D benefit offers beneficiaries coverage of up to $2400 in spending in 2007, at which point coverage stops until beneficiaries reach a catastrophic cap ($5451). Once the catastrophic cap is reached, coverage resumes with minimal cost sharing. Prior to the introduction of Part D, benefit caps—without this catastrophic limit—were a standard feature of Medicare + Choice plans (now known as Medicare Advantage) and some retiree plans. As of 2002, 94% of Medicare + Choice plans that covered branded drugs had an annual dollar cap ranging from $750 to $2000 per year.4 Analogous policies used by state Medicaid programs place limits on the number of prescriptions dispensed per patient per month. Because benefit caps represent an extreme version of cost sharing—patients who reach them must pay all additional pharmacy costs out of pocket—and their central role in Part D, we include them in our review.

Additional cost-saving measures include prior authorization (requiring permission before certain drugs can be dispensed), step therapy (requiring use of lower-cost medications before providing coverage for more expensive alternatives), closed formularies, mandatory generic substitution, and reference pricing (a cap on the amount a plan will pay for a prescription within a specific therapeutic class). There is a growing literature on each of these cost-containment measures.

METHODS

We conducted electronic searches of PubMed for studies published in English between 1985 and 2006. The primary search was based on combinations of 2 sets of key words. The first set included various terms for drug cost sharing: cost-sharing, incentive-based, copay, coinsurance, tiered benefit, benefit cap, patient charge/fee, user charge/fee, prescription charge/fee, step therapy, reference pricing, prior authorization, formulary, formulary restriction, formulary limit, closed formulary, open formulary, and generic only. The second set included drug spending, drug cost, prescription drug, medication, and pharmacy benefit. Articles that contained at least 1 term were included. We performed another search specifically for Medicaid-related drug cost sharing measures by combining one of the terms access restriction, drug/prescription/reimbursement limit, or preferred drug list with Medicaid and with one of the terms spending, use, or cost. We excluded issue briefs, comments, letters, editorials, essays, articles without author names, and reviews. This process yielded 923 studies. We then screened these studies based on titles, abstracts, and, in a few cases, the full text, as described in the Figure.

A study was included in this review if (1) the article was published in a peer-reviewed journal; (2) it examined the effects of cost sharing (co-payments, tiers, coinsurance, reference pricing, formulary restrictions, or benefit caps) on at least 1 of the relevant outcomes (prescription drug utilization or spending, medical utilization or spending, or health outcomes); and (3) it analyzed primary or secondary data (to exclude simulations).

Among the 923 studies, 111 met these criteria. An additional 21 studies were added based on reference lists, resulting in 132 studies for final analysis. Sixty-five studies examined co-payments, tiers, or coinsurance5–69 11 examined benefit caps4, 43, 70–78 41 examined formulary restrictions79–119 and 16 examined reference pricing.120–135 (One study examined the effects of co-payments and benefit caps.43)

Because the majority of these studies analyze observational data, it is very important to understand how the researchers captured the effects of cost-sharing. We classified study designs as follows:

(Aggregated) time series. Analyzed changes over time in data aggregated at the geographic or plan level, with the data spanning a period when benefits changed;

Cross-sectional. Analyzed individual-level data at a point in time for multiple benefit designs—for example, across health plans;

Repeated cross-sectional. Analyzed cross-sectional data from multiple time periods

Longitudinal. Analyzed individual-level data with repeated observations for the same subjects over time; and

Before and after. Compared outcomes at two points in time, before and after a benefit change.

Randomized trial

The literature on cost-sharing is much more diffused than many medical interventions, which benefit from clear delineation of primary and secondary clinical endpoints. For example, some papers examine pharmaceutical spending, while others look at utilization. And, among the latter, utilization is measured in at least five different ways: the medication possession ratio, the proportion of days covered, the cumulative multiple-refill gap, number of prescriptions, and aggregate days supplied. This problem is further exacerbated by the wide range of “treatments”—adding a second or third tier, raising co-payments, requiring co-insurance, to name a few—and treated populations with very different diseases. The result is tremendous heterogeneity in benefit changes, the way results are reported, and for which affected populations. Thus, many of the conclusions of this review are necessarily qualitative.

RESULTS

Impact of Co-Payments and Co-Insurance on Pharmacy Spending

The evidence from the 656,69 studies that examined the relationship between 3 of the most important features of drug benefits—co-payments, tiering, and coinsurance—and pharmacy utilization and costs is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies examining the impact of co-payment, tiering or coinsurance on prescription drug utilization and spending, medical utilization and spending (65 studies)

| Author | Study sample | Study design | Drug benefit variation | Outcomes | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies that examine the impact on prescription drug utilization only | |||||

| Andersson K et al., 2006 | Delivers of pharmaceuticals to the Swedish population from Jan 1986 to Dec 2002, at the chemical subgroups level ( Aggregated data from National Corporation of Swedish Pharmacies ) | Time series | Three national policies (Jan 1, 1991; Jan 1, 1995 and January 1, 1999) in Sweden increasing patient drug co-payment | Total defined daily doses (DDDs) Total drug costs |

Co-payment increases were not associated with changed level or slope of drug cost or volume |

| Dormuth CR, 2006 | 173,076 elderly patients with COPD or asthma in British Columbia (Pharmacy claims and administrative medical records 1997–2004) |

Before-after no control group |

Drug policies in three periods for BC elderly on patients’ prescription payment: 1) 100% dispensing fee up to an annual ceiling of Can $200 (before 2002); 2) $10 or $25 drug co-payment with annual ceilings of $200 or $275, depending on income (Jan 2002-Apr 2003); 3) 25% coinsurance + income based deductible + revised income-based annual ceilings(Since May 2003) | DDDs per 10,000 patient months Drug initiation and cessation |

Drug policy changes in 2002–2003 for BC elderly were associated with significant reductions in the use of inhaled medications (−12.3% to −5.8%), Newly diagnosed patients were 25% less likely to initiate treatment in period 2) or 3), compared to period 1). Chronic users were 47% and 22% more likely to cease treatment during period 2) and 3), compared to period 1). |

| Gibson TB et al., 2006 | 234,685 statin users continuously enrolled in a health plan during 2001–2003 (Enrollment data, pharmacy and medical claims 2001 – 2003) |

Longitudinal | Variation in statin co-payments across health plans and over time | MPR | A 100% co-payment increase lowered monthly adherence rates for statin medications by 2.6 and 1.1 percentage points among new and continuing users, respectively. Those who recently initiated satins therapy were more price-sensitive. |

| Goldman DP et al., 2006 | 62,774 adults continuously enrolled in a health plan for at least 1 year before and after initiating cholesterol therapy (Pharmacy claims and medical claims data 1997–2002) |

Repeated cross-sectional | Variation in statin co-payments across health plans | MPR |

A 100% co-payment increase lowered the fraction of fully compliant patients for cholesterol therapies by 10 to 6 percentage points, depending on patient risk. Eliminating co-payments for high- and medium- risk patients, while raising them (from $10 to $22) for low-risk patients is predicted to avert 79,837 hospitalizations and 31,411 ED visits annually among a national sample of 6.3 million adults on CL therapy. |

| Goldman DP et al., 2006 | Patients with at lest two primary diagnoses for cancer, kidney disease, Rheumatoid Arthritis(RA) or Multiple Sclerosis(MS) among 1.5 million private insurance enrollees. (Pharmacy claims and medical claims data 2003–2004) | Repeated Cross-sectional | Variation in drug coverage generosity (ratio of total out-of-pocket payments relative to total payments, for a specific drug category) across health plans and over time (2003–2004) | Rx spending | A 100% increase in effective coinsurance rate was associated with 7% decrease in MS total drug spending and 21% decrease in RA drug spending. The spending reductions for cancer drugs and Kidney disease drugs were smaller: 1% and 11% respectively and were not statistically significant. |

| Li X et al., 2006 | 8,017 elderly British Columbia residents with rheumatoid arthritis (Administrative data 2001–2002) |

Before-after no control group |

Drug policy changes for BC elderly on patients’ prescription payment: 1) 100% dispensing fee up to annual ceilings of Can $200 (before 2002); 2) $10 or $25 drug co-payment with annual ceilings of $200 or $275, depending on income (Jan 2002-Apr 2003) | Number of prescriptions filled Physician visits |

100% increase in effective drug price (the price an individual would face under the new cost-sharing policy if their consumption remained at the pre-policy level) was associated with 20% to 11% reduction in drug use, and 4% to 6% increase in physician visits, for low-income seniors and other seniors, respectively. |

| Taira DA et al., 2006 | 114,232 hypertension patients who filled prescriptions for hypertensive medications between Jan 1999 to June 2004 (Administrative data and pharmacy claims data from a MCO 1999–2004) |

Repeated cross-sectional | Three co-payment levels in a tiered formulary: $5, $20, and $20–165 | Adherence (MPR >= 0.8) | Relative to medications with a $5 co-payment, the odds ratio for compliance with drugs having a $20 co-payment was 0.76; for drugs requiring a $20 to $165 co-payment, the odds ratio for compliance was 0.48. |

| Wang J et al., 2006 | 47,115 adult prescription users in Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS) 1996–2001 | Repeated cross-sectional | Cross-sectional variation in generosity of drug benefit (share of annual drug cost paid by insurance) | Number of filled prescriptions | Non-Hispanic blacks were less likely than non-Hispanic whites to receive essential new drugs. The number of essential new drugs acquired is negatively correlated with co-payments. |

| Anis AH, et al., 2005 | 2,968 elderly British Columbia residents with rheumatoid arthritis (Pharmacy claims data and administrative medical records 1996–2000) |

Before-after no control group |

Periods before and after annual drug co-payments reached the maximum, within a calendar year | Number of filled prescriptions Hospital admissions |

Among elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis and who had exceeded the maximum annual co-payment of Can $200 at least once during the period of 1997–2000, there were 0.38 more physician visits per month, 0.50 fewer prescriptions filled per month and 0.52 fewer prescriptions filled per physician visit, during the “cost-sharing” period, compared to the “free” period. Frequency of hospital admissions didn’t differ. |

| Contoyannis P et al., 2005 | 573, 426 elderly randomly selected from the population of Quebec Pharmacare beneficiaries from Aug 1993 – June 1997 (Administrative data 1993 – 1997) |

Before-after no control group |

Two drug policy changes in Quebec Pharmacare program: Before Aug 1996, low-income elderly had free drug coverage while other elderly paid $2 per prescription. Since Aug 1996 all paid %25 coinsurance with income-based annual ceilings. Beginning Jan 1997 a quarterly deductible was added and an annual ceiling was applied per quarter and still varied by income. | Rx spending | A 100% increase in effective drug price (the price an individual would face under the new cost-sharing policy if their consumption remained at the pre-policy level) was associated with 16% to %12% reduction in total drug spending in a given period. |

| Gibson TB et al., 2005 | 114,232 employees in two firms (Pharmacy claims and medical claims 1995–1998) |

Before–after with a control group |

Co-payment level in one firm changed from $2 to $2, $7 for generics and brand-name drugs, respectively; co-payment level in the other firm remained unchanged | Number of filled prescriptions Rx spending |

A 100% co-payment increase in brand drugs was associated with a 4% decrease in total drug use, 27% decrease in the use of multi-source brand drugs and a 32% decrease in the use of single source brands. Total drug expenditures decreased by about 10%. Enrollees with a newly diagnosed chronic condition were less price-sensitive. |

| Hansen RA et al., 2005 | 9,819 privately insured PPI users in year 1998 (Administrative claims data 1997–1998, DTC advertising expenditure data) |

Cross-sectional | Whether or not a plan has > $5 copay for a brand-name PPI prescription across multiple drug benefit plans | Rx switching | Patients paying >$5 copay for brand-name PPI prescription were 12% less likely to switch from lansoprazole to omeprazole than patients paying lower copayments. |

| Huskamp HA et al., 2005 | 36,102 children continuously enrolled for 33 months as dependents in two employer-sponsored managed care plans (Eligibility file and pharmacy claims data 1999–2001) | Before-after with control group |

One employer changed formulary from 1-tier to 3-tier and increased co-payments in all tiers. The other employer had a stable 2-tier formulary | Initiation of drug therapy Discontinuation rate Rx spending OOP and plan Rx spending |

Adding a third tier with a $30 co-payment decreased the probability that children received a drug for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder by 17%, decreased total medication spending by 20% and shifted more medication costs to patients. |

| Landsman PB et al., 2005 | Users of nine drug classes continuously enrolled for two years in one of four managed care plans with total members of 1,630,000 (Enrollment and pharmacy claims data 1999–2001) |

Before-after with control group |

Three plans changed from 2-tier formulary to 3-tier formulary while one plan had a stable 2-tier formulary | MPR Discontinuation rate Rx switching Number of filled prescriptions |

Patients had statistically significant decreases in MPRs in seven out of nine drug classes. A 100% co-payment increase lowered the number of monthly filled prescriptions in each of the nine drug classes. Reductions ranged from 60 percent to 10 percent. |

| Roblin DW et al., 2005 | 26,220 12-month episodes of oral hypoglycemic (OH) from 5 MCOs (Enrollment and pharmacy claims data 1997–1999) |

Time series | Variations in over time co-payment increase ($0 to $10 or more) across 5 MCOs | Standard OH average daily dose (ADD) per month | >$10 co-payment increase decreased use of oral hypoglycemic (OH) medications by 18.5%. Smaller co-payment increases had no significant effect on OH spending. |

| Briesacher B et al., 2004 | 20,868 patients with arthritis, enrolled in 32 employer-sponsored drug plans and used NSAIDs during year 2000 (Pharmacy claims, medical claims and encounter data 2000) |

Cross-sectional | Variation in drug tiers and co-payments for COX II selective inhibitors across drug plans | Probability of using COX II selective inhibitors | The odds of using COX II selective inhibitors were significantly lower (odds ratio 0.36) if their drug formulary designated COX II as only non-preferred products compared with patients with 1-tier drug coverage; Co-payments exceeding $15 were also associated with lower odds (0.49) of drug initiation, relative to co-payments of $5 or less. Such relationship persists even for patients who had GI comorbidities. |

| Crown WH et al., 2004 | 63,231 asthma patients with employer-sponsored drug plans (Pharmacy claims, medical claims and encounter data 1995–2000) |

Repeated cross-sectional | Cross-sectional variations of drug co-payments | Initiation of Rx therapy Days of supply Controller-to-Reliever ratio of asthma drugs |

The level of patient cost-sharing did not affect the use of asthma medications. However, physician/practice prescribing patterns strongly influenced patient-level treatment patterns. |

| Ellis JJ et al., 2004 | 4,802 non-Medicaid enrollees with statin prescriptions in one MCO and between Jan 1998 to Nov 2001 (Pharmacy and medical claims 1998–2001) |

Repeated cross-sectional | Cross-sectional variations of drug co-payments | Cumulative multiple refill-interval gap (CMG) Discontinuation rate |

The mediums duration for statin therapy were 3.9 years, 2.2 years, and 1.0 years for patients whose average monthly statin co-payments were <$10, $10–20, and>$20, respectively. |

| Goldman DP et al., 2004 | 528,969 privately insured beneficiaries aged 18–64 and enrolled from 1 to 4 years in one of 52 health plans (Pharmacy and medical claims data 1997–2000) |

Repeated cross-sectional | Cross-sectional variations of indexes of drug plan generosity | Days of supply | 100% co-payment increase in a two-tier plan lowered utilizations in each of 8 therapeutic classes. Reductions range from 25% to 45%. Largest reductions were for drugs with close OTC substitutes. |

| Kamal-Bahl S et al., 2004 | 149,243 hypertension patients who had prescriptions for at least one of the five classes of drugs during year 1999 (Pharmacy claims, medical claims and encounter data 1999) |

Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional variations in co-payments within 1, 2, or 3 tiered formularies | Initiation of drug therapy Rx spending OOP and plan Rx spending |

Lower likelihood of using ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with co-payment differences of at least $10 between generic and brand drugs. A 100% increases in drug-co-payment was associated with a predicted decrease of 8.9% in total drug spending in a 1-tier plan. |

| Liu SZ et al., 2004 | More than 3 million prescriptions for a sample of elderly patients randomly drawn from 21 hospitals in Taipei (Administrative data 1998 – 2000) |

Before-after with control group |

Since Aug 1999, prescription drug policy in Taiwan changed from full coverage to 20% coinsurance with a maximum of $15.625 per prescription, for prescriptions costing more than $3.125. Selected groups were exempted | Average prescription cost | Compared to the non-cost sharing group, cost sharing group experienced a lower growth of average prescription cost since drug policy change. Elderly with non-chronic diseases were more price-sensitive. |

| Lurk JT et al., 2004 |

Aggregated monthly data Nov 1999 to Dec 2002 in one safety-net provider |

Before-after no control group |

Over-time change in drug co-payments | Number of filled prescriptions OOP and plan Rx spending |

An average $5 increase in co-payment was associated with reduced drug utilization and a $26.07 decrease in prescription drug cost to the clinic per visit per month, in an ambulatory care safety-net provider setting. |

| Meissner BL et al., 2004 | 8,463 beneficiaries continuously enrolled in a public employer health plan from 1998–1999 (Pharmacy claims data 1998–1999) |

Before-after no control group |

Over-time change in drug co-payments | Days of supply Number of filled prescriptions Plan Rx spending |

An average $10 co-payment increase for two classes of allergy medications was not associated with significant change in combined lower-sedating antihistamines (LSA) and nasal steroids (NS). In stead, it was associated with 13% reduction in plan drug cost for allergic rhinitis patients. Unadjusted Arc elasticity is 0.39 for LSA and −0.22 for NS. |

| Blais L et al., 2003 | 34,627 Quebec residents receiving social assistance, aged 64 or less and had any prescription for medications under study (Quebec Administrative claims data 1992–1997) |

Time series | Drug policy changed for Quebec elderly in 1996–1997: from zero or $2 drug co-pay to %25 coinsurance plus a income-based annual ceiling of $200-$925; A control group included privately insured individuals | Total number of prescriptions dispensed per month | Quebec drug policy change didn’t reduce the total monthly consumption for neuroleptics and anticonvulsants, but reduced total monthly consumption for inhaled corticosteroids by 37%. |

| Huskamp HA et al., 2003 | 151,222 enrollees covered by two employers and were users of one of the following three classes of drugs: ACE inhibitors, PPIs and statins (Eligibility file and pharmacy claims data 1999–2001) |

Before-after with control group |

Employer A changed drug co-pay from $7/$15 to $8/$15/$30; employer B changed from $6/$12 to $6/$12/$24. Enrollees from other employers with stable 2-tier benefits were chosen as control groups | Initiation of drug therapy Adherence/compliance/MPR Rx switching Discontinuation rate Rx spending OOP and plan Rx spending |

Dramatic increases in drug co-payments were associated with higher rate of discontinuation with drug therapy (21% versus 11 %) and higher Rx switching to lower cost medications (49% versus 17%), in all three drug classes. A more moderate increase in drug co-payments were associated with higher Rx switching but not higher discontinuation rates. There were no consistent effects of co-payment increase on total drug spending in three drug classes |

| Liu SZ et al., 2003 | More than 1.6 million prescriptions for a sample of elderly patients randomly drawn from 21 hospitals in Taipei (Administrative data 1998 – 2000) |

Before-after no control group |

Since Aug 1999, prescription drug policy in Taiwan changed from full coverage to 20% coinsurance with a maximum of $15.625 per prescription, for prescriptions costing more than $3.125. Selected groups were exempted | Rx spending | Imposing cost-sharing was associated with a 12.86% increase in total prescription drug costs in the cost-sharing group, mainly due to an increase in average drug costs per prescription (explaining 69.20% of the variance) |

| Nair KV et al., 2003 | 8,312 patients with chronic conditions in a managed care plan (Membership data and pharmacy Claims data 2000 – 2001) |

Before-after with control group |

Intervention group had drug benefit changing from 2-tier to 3-tier; two control groups had stable 2 or 3 tier drug benefits |

Rx switching Formulary compliance rate Discontinuation rate |

Moving from a two-tier to a three-tier drug benefit was associated with an increased use of generic drugs (6 to 8 percentage points) and formulary compliance. |

| Rector TS et al., 2003 | Pharmacy claims for three therapeutic classes (ACE inhibitors, PPIs and statins) in four independent physician practice association model health plans (1998–1999) | Before-after with control group |

Four health plans changed drug benefits from two-tiered plans to three-tiered plans in different quarters during 1998–1999 | Use of preferred brands | Moving from a two-tier to a three-tier drug benefit led to increases in the percentage use of preferred brands for ACEI, PPI and statins by 13.3, 8.9, and 6.0 percentage points, respectively, over a 21-month period. |

| Ong M et al., 2003 | Monthly drug-use data for three therapeutic classes (antidepressants, anxiolytics, and sedatives) from July 1990 through Dec 1999 in Sweden | Time series | Drug co-payment increases in 1995 and 1997 | Defined daily doses (DDD) per 1,000 inhabitants | Permanent increases in male antidepressants and sedatives occurred before the 1995 reform; only female antidepressant use was permanently reduced by the 1997 reform. |

| Artz MB et al., 2002 | 6,237 elderly covered by Medicare (Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey 1995) |

Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional variation in drug coverage generosity | Number of filled prescriptions Rx spending |

Prescription drug spending increased with drug plan generosity across a range of insurance types. |

| Joyce G et al., 2002 | 420,786 primary beneficiaries aged 18–64 with employer-provided drug benefits (Pharmacy and medical claims data 1997–1999) |

Repeated cross-sectional | Cross-sectional variations of drug benefits (number of tiers, co-payments and coinsurance rates) | Rx spending OOP and plan Rx spending |

Doubling co-payments decreased annual drug spending by 22% to 33% and increased the fraction beneficiaries paid out-of-pocket from 17.6% to 25.6% in a two-tier plan. |

| Pilote L et al., 2002 | 22,066 Quebec elderly patients who experienced acute myocardial infarction between 1994–1998 (Quebec Administrative claims data 1994–1998) |

Before-after no control group |

Drug policy changed for Quebec elderly in 1996–1997: from zero or $2 drug co-pay to %25 coinsurance plus a income-based annual out-of-pocket maximum of $200-$925 | Initiation of drug therapy Medication persistence Rx switching Hospital admissions, ED visits and physician visits Mortality |

Quebec drug policy change didn’t reduce use for essential cardiac medications among Quebec elderly who experienced acute myocardial infarction, nor medical utilizations. The findings did not vary by sex or socioeconomic status. |

| Thomas CP et al., 2002 | 29,435 elderly with employer-based drug benefit plans for retirees (Pharmacy claims data 2001) |

Cross-sectional | Variation in drug formulary tiers, co-payment and coinsurance rates across 96 health plans | Number of filled prescriptions Rx switching Prescription size(mail/retail) Rx spending OOP Rx spending |

Increased patient cost-sharing and formulary restrictions were associated with lower drug spending, higher out-of-pocket costs, and a shift to lower cost medications (generics and mail-order). |

| Blais L et al., 2001 | 259,616 Quebec elderly residents who had any prescription for the medicines under study during the whole study period: Aug 1992 to Aug 1997 (Quebec Administrative claims data 1992–1997) |

Time series | Drug policy changed for Quebec elderly in 1996–1997: from zero or $2 drug co-pay to %25 coinsurance with maximum OOP payment ceiling, plus a income-based annual out-of-pocket maximum of $200-$925 | Total number of prescriptions dispensed per month | Quebec drug policy change didn’t reduce total number of prescriptions dispensed per month for nitrates, antihypertensive agents, benzodiazepines, and anticoagulants. |

| Kozyrskyj AL et al., 2001 (a) | 10,703 school-aged children in Manitoba who had asthma (Administrative data Apr 1995 – Apr 1998) |

Before-after with control group |

Before Apr 1996, Manitoba’s drug benefit program required a fixed deductible payment of $237 per family plus 40% co-payment on prescription costs above $237. Since April 1996 this policy was replaced by income-based deductibles with low-income family pay up to 2% of their income as deductible and high-income family pay up to 3%. | Initiation of drug therapy Number of prescription filled |

Implementation of income-based deductible in Monitoba’s drug benefit policy was associated with a decrease in the use of inhaled corticosteroids by high-income children with severe asthma and did not improve use of these drugs by low-income children |

| Kozyrskyj AL et al., 2001 (b) | 12,481 school-aged children in Manitoba who had asthma (Administrative data July 1995 – March 1998) |

Repeated cross-section | Same as Kozyrskyj AL et al., 2001 (a) | Initiation of drug therapy | In comparison with higher-income children with asthma, odds ratio of receiving inhaled corticosteroid prescriptions was 0.82 – 0.88 for low-income children with asthma, controlling for asthma severity, type of drug insurance, or health care utilization patterns. |

| Hillman AL et al., 1999 | 134,937 non-elderly enrollees of nine managed care plans (Pharmacy claims data 1990–1992) |

Repeated cross-section |

Variation of drug co-payments both across and within health plans | Initiation of drug therapy Days of supply Rx spending |

Higher co-payments for prescription drugs were associated with lower drug spending in independent practice associations (IPAs) but not in network models where physicians bear financial risk for prescription drug costs. |

| Motheral BR et al., 1999 | 3,184 individuals continuously enrolled in commercial plans from 1996 to 1997 (Pharmacy claims data 1996–1997) |

Before-after with control group |

Enrollees in two different employer plans experienced brand copay increase from $10 to $15, while those in the control group had brand copay of $10 during the study period | Initiation of drug therapy Number of filled prescriptions Rx switching Discontinuation rate Rx spending OOP and plan Rx spending |

Increasing the co-payment from $10 to $15 was associated with lower use of brand drugs, lower plan drug spending and lower total ingredient costs. But There was no statistically significant difference in overall utilization or discontinuation rates for chronic medications. |

| Stuart B et al., 1999 | 1,302 elderly and disabled Medicaid recipients (Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey 1992) |

Cross-sectional | Variation of drug co-payments across state Medicaid programs | Initiation of drug therapy Number of prescriptions filled OOP Rx spending |

Imposing $0.50 - $3.0 drug co-payments in state Medicaid programs reduced drug use among elderly and disabled Medicaid recipients by 15.5% in 1992. Primary effect of co-payments is to reduce the likelihood of any prescription filling (by 7.7 percentage points). Those reporting poor health status were most adversely affected by co-payments. |

| Grootendorst PV et al., 1997 | 5,743 Ontario residents aged 55–75 (Survey data) |

Cross-sectional | Discontinuity in drug benefit availability: the provision of first-dollar prescription drug insurance coverage for Ontario residents at age 65 | Initiation of drug therapy Number of prescriptions filled |

The provision of first-dollar prescription drug insurance coverage at age 65 increased drug use, primarily among individuals with lower levels of health status. Most of the increased use was due to the increased level of use among drug users rather than an increase in the probability of use. |

| Hong SH et al., 1996 | 3,144 children enrolled in five drug benefit plans during Dec 1992 to Dec 1993 (Pharmacy claims and enrollment database 1992–1993) |

Cross-sectional | Variations in drug co-payment and cost-sharing differentials between generic and brand name drugs across five drug benefit plans | Rx initiation Number of filled prescriptions Rx spending OOP Rx spending |

Higher levels of cost-sharing per prescription were associated with higher drug utilization. Larger cost-sharing differentials between generic and brand name drugs were associated with higher rates of generic drug use but were not always associated with lower expenditure rates |

| McManus P et al., 1996 | Summary statistics on total number of prescriptions (Administrative data 1987–1994) |

Time series | In Nov 1990 in Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), patient contribution increased from $A11 to $A15 for the general population. In Jan 1992, a $A2.50 co-payment was required for returned service men and women. | Total monthly number of prescriptions | Increasing drug co-payment was associated with decreased level of drug consumption, but not associated with a changing trend, for both the general population and the returned service men and women. The effect was larger for “discretionary drugs”, relative to “essential drugs”. |

| Coulson NE et al., 1995 | 4,508 elderly Medicare beneficiaries in Pennsylvania (Survey data linked with administrative claims data 1989) |

Cross-sectional | Variation in drug coverage generosity by different insurance types among the elderly. | Number of prescriptions filled | low-income elderly (<$12,000 single or <$15,000 married) in Pennsylvania were covered by the program of Pharmaceutical Assistance Contract for the Elderly (PACE) and only paid $4 per 30 day dosage. Enrollees of the PACE program had 0.29 more prescriptions per two-week period than did elderly who had no prescription drug coverage. |

| Hughes D et al., 1995 | Monthly statistics in England in 1969–1992 (Published government statistics) |

Time series | Over-time variation of drug co-payments in UK National Health Service | Number of non-exempt dispensed prescriptions per year per capita |

A 10% increase in prescription charge was associated with a 3.2% decrease in per capita utilization of drugs within the non-exempt category |

| Smith DG et al., 1993 | Aggregated data on use and costs of prescription drugs for 212 employer-groups covered by one managed care company in 1989 | Cross-sectional | Variation of drug co-payments ($1 to $8) across employer-groups | Number of filled prescriptions Rx spending OOP and plan Rx spending |

Increasing co-payments from $3 to $5 was associated with a 5% decrease in the number of filled prescriptions and a 10% decrease in employer drug spending. |

| Ryan M et al., 1991 | Monthly statistics in England in 1979–1985 (Published government statistics) |

Time series | Over-time variation of drug co-payments in UK National Health Service | Number of non-exempt dispensed prescriptions per month per capita Rx spending |

10% increase in prescription drug charge was associated with 1% reduction in per capita drug utilization during the period of 1979 – 1985. Approximately two thirds of the government expenditure savings were due to reduction in utilization as opposed to increased charges on per item of drugs. |

| Harris BL et al., 1990 | 43,146 beneficiaries continuously enrolled in an HMO for a four-year period (Administrative pharmacy data 1982–1986) |

Before-after with control group |

The intervention group experienced co-payment rates of $1.50, $1.30, $3,00 plus other benefit changes during a three-year period while the control group of the same plan had no drug co-payment during the whole period | Number of filled prescriptions Rx spending |

Graduated increases in drug co-payments (from $0 to $1.50 to $3) plus other formulary restrictions were associated with 10% to 12% reductions in the number of prescriptions and 6.7% reduction in per capita drug costs |

| Lavers RJ 1989 | Monthly statistics in England and Wales in 1971 – 1982 (Published government statistics) |

Time series | Over-time variation of drug co-payments in UK National Health Service | Number of non-exempt dispensed prescriptions per month | 10% increase in prescription drug charge was associated with a 2.0% to 1.5% fall in the monthly volume of non-exempt items during the period of 1971–1982, |

| O’Brien B, 1989 | Monthly statistics in England in 1969–1986 (Published government statistics) |

Time series | Over-time variation of drug co-payments in UK National Health Service | Number of non-exempt dispensed prescriptions per month | 10% increase in prescription drug charge was associated with a 3.3% fall in the volume of non-exempt items during the period of 1969–1986, the reduction was 2.3% in the sub-period 1969–1977 and 6.4% in the later period 1978–1986. Cross-price elasticity on exempted items was |

| Foxman B, 1987 | 5,765 non-elderly enrollees who participated the entire second year of RAND HIE on the fee-for-service plans in six sites | Randomized trial | Participants were randomly assigned into health plans with %0, %25, %50, %95 coinsurance rates or an individual deductible plan | Number of filled prescriptions | People with free medical care used 85% more antibiotics than those required to pay some portion of their medical bills. |

| Birch S 1986 | Annual statistics in NHS in 1979 – 1983 (Published government statistics) |

Time series | NHS patient charges on pharmaceuticals increased from 1979 to 1983. Part of the population were required to pay the charges while others were exempted from the charges. | Number of items dispensed per capita per year | During the period of 1979–1982, the per capita consumption of prescriptions in non-exempt group decreased by 7.5% while the per-capita consumption in exempted group increased by 1%. |

| Leibowitz A et al., 1985 | 3,860 non-elderly enrollees who participated the entire first year of RAND HIE on the fee-for-service plans in three sites | Randomized trial | Participants were randomly assigned into health plans with %0, %25, %50, %95 coinsurance rates or an individual deductible plan | Number of filled prescriptions Rx switching Samples from physicians Rx spending |

Consumers facing a 95% coinsurance rate for prescription drugs (up to a maximum dollar expenditure) spent 57% as much as those in a free-care plan. |

| Reeder CE et al., 1985 | 62,176 Medicaid recipients in South Carolina (claims data 1976–1979) |

Time series | Change in Medicaid outpatient drug co-payments since Jan 1977: from $0.0 to $0.50 per prescription | Rx spending | Imposing a $0.50 co-payment for outpatient prescriptions covered by South Carolina Medicaid programs had differential effects on the utilizations of drugs in ten various therapeutic categories. Drug utilizations dropped immediately after the co-payment increase in eight out of ten classes (except analgesics and sedatives/hypnotics). In the long-term the utilization trends in four therapeutic classes were significantly changed after the co-payment increase. |

| Studies that also examine the impact on medical utilization and spending | |||||

| Cole JA et al., 2006 | 12,776 CHF patients taking ACE inhibitors, Beta blockers or both in 2002 (Claims data 2002, 2003) |

Cross-sectional | Variation in drug co-payments across health plans | Medication possession ratio (MPR) Total medical costs CHF-related hospitalizations |

A $10 increase in drug co-payment is associated with 2.6% and 1.8% decreases in MPRs for patients taking ACE inhibitors and Beta blockers, respectively. Such decreases were associated with predicted increases of CHF-related hospitalizations by 6.1% and 8.7%. Predicted total medical costs were not affected. |

| Gibson TB et al., 2006 | 117,366 statin users continuously enrolled in a health plan during 2000–2003 (Pharmacy and medical claims data 2000–2003) |

Repeated cross-sectional | Variation in statin co-payments across health plans | MPR Hospital admissions ED visits Physician visits |

A $10 increase in co-payment resulted in a 1.8 and 3.0 percentage point reduction in adherence, among new and continuing statin users, respectively. For continuing users, higher statin adherence was associated with lower negative events (hospital admissions and ED visits) but not with total costs. |

| Mahoney JJ et al., 2005 | Diabetes-related claims and drug use and cost statistics in one company (2001–2003) | Before-after no control group |

One company reduced coinsurance rates on diabetes drugs to 10% (from 25% to 50%) in Jan 2002. | Adherence Rx spending Rx + Medical spending ED visits |

From 2001 to 2003, adherence and use of fixed-combination therapy had increased among diabetes patients. Average total pharmacy costs had decreased by 7% and overall medical costs decreased by 6%. ED visits had decreased by 26%. |

| Winkelmann R, 2004 | 37,319 individuals in Germany (Survey data 1995–1999) |

Before-after with control group |

Co-payment for prescriptions increased by 6 DM in 1997. Certain groups were exempted from such an increase and served as the “control” group | Physician visits | In Germany, An additional 6 DM prescription fee reduced the number of doctor visits by 10% on average. |

| Fairman KA et al., 2003 | 7,709 enrollees in a PPO (Pharmacy and medical claims data 1997–2000) |

Before-after with control group |

Enrollees in the intervention group experienced a formulary change from 2-tier to 3-tier; Enrollees in the control group had stable 2-tier formulary | Number of filled prescriptions Rx Continuation rate Rx spending OOP and plan Rx spending Hospitalizations, ED visits and ambulatory visits |

Moving from a two-tier to a three-tier drug benefit was associated with reduced growth in plan cost and lowered utilization of non-formulary medications, but not associated with lower growths of total prescription claims or total drug spending. The associations between adding tiers and drug continuation rates were mixed for four classes of chronic medications. Such drug benefit change was not associated with number of hospitalizations, ED visits or office visits |

| Balkrishnan R et al., 2001 | 2,411 Medicare HMO enrollees in 1998 and 1999 (Data source unknown) |

Before-after no control group |

In 1998, co-payments were $7/$15, for generics and brand names, separately, with quarter OOP maximum of $200. In 1999, there was unlimited coverage for generics and limited coverage for brand drugs. | Plan Rx spending Plan Rx + medical spending Physician visits |

Changing to a drug policy with unlimited coverage for generics and limited coverage for brand drugs was associated with 27% decrease in plan drug costs, 4% decrease in physician visits and 5% decrease in plan total costs |

| Motheral BR et al., 2001 | 20,160 individuals continuously enrolled in a PPO from Jan 1997 to Dec 1999. (Pharmacy and medical claims data 1997–1999) |

Before-after with control group |

Enrollees of the intervention group had drug benefit changed from 2-tier to 3-tier. Those in the control group has stable 2-tier benefit | Initiation of drug therapy Number of filled prescriptions Rx Discontinuation rate Rx spending OOP and plan Rx spending Hospitalizations, ED visits and ambulatory visits |

Moving from a two-tier benefit with co-payments of $7/$12 to a three-tier benefit with co-payments of $8/$15/$25 was associated with slower growth in prescription drug utilization and drug spending (15% vs. 22%). Adding tiers were not consistently associated with medication discontinuation rates of four chronic therapy classes, and not associated with hospitalizations, ED visits or office visits |

| Tamblyn R et al., 2001 | 149,283 Quebec residents 65 years and older or receiving welfare (Administrative data 1993–1997) |

Time series | Drug policy changed for Quebec elderly in 1996–1997: from zero or $2 drug co-pay to %25 coinsurance plus a income-based annual out-of-pocket maximum of $200-$925 | Mean daily drug use Serious adverse events (acute care hospitalizations, long-term care admission, or death) |

Quebec drug policy change was associated with a 9% and 14% reduction in use of essential drugs, for elderly and welfare recipients respectively. Such reductions were associated with increased number of serious adverse events and ED visits. Use of less essential drugs decreased by 15% and 22%. |

| Berndt ER et al., 1997 | 3,470 privately insured individuals from 26 plans treated for depression in 1993 (Medical and pharmacy claims 1993) |

Cross-sectional | Variations of drug copayment across 26 health benefit plans | Initiation of drug therapy Hospitalizations |

Among depressed patients receiving outpatient treatment, higher prescription drug copayment was associated higher share of SSRI utilizations in all anti-depressant medications; higher drug copayment was not associated with higher probability of hospitalizations |

| Johnson RE et al., 1997(a) | Elderly HMO members during a four-year period (Administrative data 1987–1991) |

Before-after with control group |

Two Medicare risk groups in an HMO setting had their co-payments and coinsurance rates increased in different years during a three-year period | Initiation of drug therapy Days of supply Rx spending Health status index |

Graduated increases in co-payments from $1 to $5 and coinsurance (from 50% to 70%, with a $25 max) did not reduce prescription drug utilization and costs in a consistent manner among each of twenty-two therapeutic drug classes. Health status may have been adversely affected as measured by Combined Chronic Disease Score and Diagnostic Cost Groups. |

| Johnson RE et al., 1997(b) | Elderly HMO members during a four-year period (Administrative data 1987–1991) |

Before-after with control group |

Two Medicare risk groups in an HMO setting had their co-payments and coinsurance rates increased in different years during a three-year period | Number of filled prescriptions Rx spending OOP Rx spending Hospitalizations, ED visits and ambulatory visits Rx + Medical spending |

Graduated increases in co-payments from $1 to $5 and coinsurance (from 50% to 70%, with a $25 max) resulted in lower prescription drug uses and expenses, and did not affect medical care utilization and expenses in a consistent manner. |

| Lingle EW et al., 1987 | 9,966 elderly Medicare beneficiaries and not eligible for Medicaid benefits (1975 and 1979) (Medicare claims data 1975,1979) |

Before-after with control group |

The intervention group includes Medicare beneficiaries covered by New Jersey’s Pharmaceutical Assistance for the Aged (PAA); the control group includes beneficiaries in eastern Pensylvania | Medical utilization Plan medical spending |

Re-imbursement for in-patient care for New Jersey’s PAA recipients was on average 238.50 lower than that in eastern Pensylvania. There was no significant increase in total medical costs reimbursed by Medicare among New Jersey’s PAA recipitents. |

Most of the evidence comes from observational studies, with the exception of two studies of the RAND Health Insurance Experiment (HIE). The HIE randomized 2,750 families to different levels of cost-sharing ranging from free care to 95% coinsurance. The HIE demonstrated that individuals subject to higher coinsurance rates reduced their demand for care, and that the cost sharing response for prescription drugs was similar to the response for all ambulatory care.66, 68 However, data from the HIE are more than three decades old. In addition, the health insurance packages in the HIE did not vary by prescription drug benefit. Thus, it is unclear whether the higher drug expenditures among people with more generous coverage were due to lower out-of-pocket costs for drugs or lower cost-sharing for office visits and other medical services that are the usual pathways for receiving prescriptions.

All the remaining studies are observational. Key features of the best studies include large sample sizes, variation in benefit design both across plans and over time, and attempts to control for other factors known to affect pharmaceutical use.19, 20, 22–24, 27, 36, 38, 42 Of particular value are studies that employ data from multiple plans and control for medical benefits, especially when they may be changing in concert with the pharmacy benefit.8, 9, 26, 34, 40, 49, 50, 52 For example, changing office visit co-payments will affect how frequently patients see the doctor, and hence the number of prescriptions they receive. Poor features include analyses that do not control for other factors that might be changing, including most of the designs looking before and after a benefit change with no control group. These designs include (but are not limited to) many international studies where co-payments change for the entire population.5,7,12,15,16,29,30,35,37,41,44,57,59,61,64,65,67

Some of the studies find relatively small changes in utilization in response to higher cost-sharing,17, 51, 55, 60, 62, 69 but these focused on small changes in co-payments. In some studies, the control groups have very different characteristics,28, 32, 39, 45, 46, 53, 67 patients may self-select into the treatment group on the basis of medication choice,13 or the source of co-payment variation is not clear.25 Given the evidence that there is differential response by condition or class of medication, studies that restrict attention to a specific patient population or conduct subgroup analysis can yield additional insight.

The effects of cost-sharing can be summarized using the price elasticity of demand. This measure represents the percentage change in drug spending that would be associated with a 1% increase in cost-sharing. When we exclude the studies that involve very small cost-sharing changes or do not have an adequate control group, we find elasticites ranging from −0.2 to −0.6, indicating that cost-sharing increases of 10% (either through higher co-payments or coinsurance) would be associated with a 2% to 6% decline in prescription drug use or expenditures.

Eleven of the 65 studies in our review explicitly looked at changes in coinsurance rates, 28,32,35,41,42,44,48,54,55,66,68,57 with two of these coming from the HIE and 4 from a benefit change in Quebec in 1996. Overall, the impact of increasing co-insurance is at the low end of our range of −0.2 to −0.6; but these effects are clearly muted by the simultaneous imposition of out-of-pocket maximums in most of these studies.

Differential Responses by Therapeutic Class

Several studies suggest that consumer sensitivity to cost-sharing depends upon a drug’s therapeutic class and that increased cost-sharing may decrease “non-essential” drug use —e.g., antihistamines—more than “essential” drug use such as anti-hypertensives and oral hypoglycemics. However, the empirical evidence in this area is mixed. Harris et al 62 found substantially larger reductions in the use of discretionary medications than essential medications in response to a modest increase in co-payments. More recently, Goldman et al 26 found that doubling co-payments was associated with lower use of eight classes of medication by 25% (antidiabetics) to 45% (antiinflammatories). Patients were less likely to reduce use of these drugs if they were receiving ongoing care from a physician for the disorder, ranging from 8% (antidepressants) to 31% (antihistamines). Landsman et al found similar price responses across nine therapeutic classes.20 Several other studies found modest, but inconsistent, effects of higher co-payments on use of essential and non-essential drug classes.33, 47, 50, 55, 69

Benefit Caps, Prescription Drug Use, and Costs

Information from the 11 studies4,43,70,78 that examined the association between benefit caps, including caps that limit the number of prescriptions and caps on an annual pharmacy benefit, and drug use and drug costs is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies examining the impact of benefit caps on prescription drug utilization and spending, medical utilization and spending (11 studies)

| Author | Study sample | Study design | Drug benefit variation | Outcomes | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies that examine the impact on prescription drug utilization only | |||||

| Tseng CW et al., 2004 | 1,308 Medicare managed care enrollees in 2001 whose drug benefits were capped and annual spending exceeded annual caps of $750 or $1,200 (Survey data 2002) |

Cross-sectional | Variations in annual drug benefit caps across counties | Under-use due to cost Rx switching |

Medicare + Choice beneficiaries exceeding their annual drug benefit cap were more likely than those that did not exceed the cap to switch medications (15% vs. 9%), use samples (34% vs. 27%) and report difficulty paying for prescriptions (62% vs. 37%). |

| Tseng CW et al., 2003 | 438,802 Medicare managed care enrollees in 2001 whose drug benefits were capped at $750, $1,000 or $2,000. (Pharmacy claims data 2001) |

Cross-sectional | Levels of annual drug benefit caps: $750, $1,000, or $2,000. | % exceeding benefit caps OOP Rx spending |

A total of 22%, 14%, and 4% of Medicare patients exceeded annual drug benefit caps of $750, $1,000, and $2,000, respectively. |

| Cox ER et al., 2002 | 212 Medicare+Choice beneficiaries with capped annual prescription drug benefits of $500 or $1,000 in year 2000 (Survey data) |

Cross-sectional | Capped drug benefits | Adherence Discontinuation |

For those who exceeded their cap prior to Oct 2000, they were more likely to stop taking one or more medications or took less than prescribed amount, after reaching the cap, compared to the pre-cap period. But these differences were not statistically significant. |

| Balkrishnan R et al., 2001 | 259 Medicare HMO enrollees in 1997–1998 (Data source unknown) |

Before-after no control group |

Change of drug benefit policy from 1997–1998: benefit cap increased from $500 per year to $200 per quarter; and co-payments changed from $6/$12 to $7/$15, for generics and brand names, separately | Plan Rx spending Plan Rx + medical spending |

Drug benefit cap from $500 per year to $200 per quarter and increased drug co-payments were associated with a 29% increase in plan Rx costs and 38% increase in total plan costs. |

| Cox ER et al., 2001 | 378 Medicare HMO enrollees who had reached >=60% of their prescription drug cap in 1997 (Survey data) |

Cross-sectional | Capped drug benefits ($750 for rural counties, $1,500 for urban counties) | Initiation of drug therapy Adherence/compliance/MPR Rx switching |

Those who reached their prescription cap were more likely to reduce drug use (OR, 2.83), to discontinue a medication (OR, 3.36), and to obtain samples from their physician (OR, 2.02), compared to those who had not reached their cap. |

| Fortess EE et al., 2001 | 343 chronically ill Medicaid enrollees (Pharmacy claims data) |

Before-after no control group |

A state Medicaid program imposed a three-prescription monthly reimbursement limit(12 months pre- and 6 months after policy change) | Standard monthly doses for essential medications | A three-prescription monthly reimbursement limit (cap) in the New Hampshire Medicaid program was associated with a 34.4% reduction in the use of essential medications. |

| Martin BC et al., 1996 | 743 Medicaid enrollees (Pharmacy claims data 1991–1992) |

Time series | A state Medicaid program reduced monthly reimbursement limit of prescriptions from six to five (6 months pre- and 6 months after policy change) | Number of filled prescriptions Rx spending OOP and plan Rx spending |

Reducing the maximum number of monthly reimbursable prescriptions from 6 to 5 was associated with a 6.6% reduction in total prescriptions among Georgia Medicaid beneficiaries with high use of prescription drugs. |

| Soumerai SB et al., 1987 | 10,734 Medicaid enrollees (Pharmacy claims data 1980–1983) |

Time series | New Hampshire Medicaid program imposed a three-prescription monthly reimbursement limit (cap) on Sep 1981, but later discontinued the policy (20 months pre-policy change; 11 months post-policy change; 17 months after the limit was replaced by $1 co-payment). | Number of filled prescriptions | A three-prescription monthly reimbursement limit (cap) in the New Hampshire Medicaid program was associated with a 30% reduction in the number of prescriptions filled. Utilization approached pre-cap levels after the cap was replaced with a $1 co-payment. |

| Studies that also examine the impact on medical utilization and spending | |||||

| Hsu et al., 2006 | 199,179 Medicare managed care enrollees in 2003 (Administrative data 2003) |

Cross-sectional | In 2003, 157,275 Medicare + Choice enrollees had annual drug benefit capped at $1,000; Another 41,904 enrollees had unlimited drug coverage due to employee supplements | Adherence Rx and medical spending Hospitalizations, ED visits, and ambulatory visits Blood pressure, LDL, Glycated hemoglobin, and mortality |

Subjects facing a $1,000 Rx benefit cap had 31% lower pharmacy costs, higher rates of drug non-adherence (Odd ratios of 1.27 to 1.33), ED visits (RR 1.09), non-elective hospitalizations (RR 1.13), and death (RR 1.22). Their total medical costs were not significantly different from those without Rx benefit cap. |

| Soumerai SB et al., 1994 | 2,227 Medicaid enrollees with Schizophrenia (Pharmacy and medical claims data 1980–1983) |

Time series | New Hampshire Medicaid program imposed a three-prescription monthly reimbursement limit (cap) on Sep 1981, but later discontinued the policy (14 months pre-policy change; 11 months post-policy change; 17 months after the limit was replaced by $1 co-payment). | Days of supply Plan Rx spending Plan medical spending Ambulatory visits Hospitalizations |

A three-prescription monthly reimbursement limit (cap) in the New Hampshire Medicaid program was associated with an immediate reduction (ranged 15% to 49%) in the use of psychotropic drugs, a significant increase in the use of emergency mental health services and partial hospitalization, but not associated with hospital admissions. Drug and medical utilizations approached pre-cap levels after the cap was replaced with $1 co-payment. |

| Soumerai SB et al., 1991 | 1,786 Medicaid enrollees who in a baseline year had been taken 3 or more prescriptions per month (Pharmacy and medical claims data 1980–1983) |

Time series | New Hampshire Medicaid program imposed a three-prescription monthly reimbursement limit (cap) on Sep 1981, but later discontinued the policy. | Days of supply Nursing home admissions Hospitalizations |

A three-prescription monthly reimbursement limit (cap) in the New Hampshire Medicaid program was associated with a 35% reduction of drug utilizations, increased risk of nursing home admissions, but not with hospitalizations, among older patients (60 and older) and who were frequent Rx users. |

Soumerai et al 77 compared Medicaid patients in New Hampshire—for whom the program had imposed a three-drug limit per patient per month—with those of New Jersey where no such cap was introduced. They found a 35% reduction in drug use relative to the control group. For patients on psychotropic medications, they found the cap was associated with a 15% to 49% reduction in the use of these drugs.76

The most salient evidence on the impact of benefit caps comes from an analysis of medical and pharmacy claims from a single, closed-network health maintenance organization.70 Members whose benefits were capped at $1,000 had 31% lower pharmacy costs than comparable enrollees not subject to a cap. One survey of Medicare beneficiaries suggest that elderly individuals who experience gaps in coverage report using fewer medications, are more likely to switch to generics or lower cost medications, and rely more on drug samples from their physicians.71 Two other studies found that patients exceeding the cap were two-to-three times more likely to discontinuation a medication 73 and unenroll from the plan.136

Reference Pricing

Information from the 16 studies121,135 examining reference pricing, wherein insurers cap the amount they will pay for a prescription within a specific therapeutic class, is summarized in Table 3.

Table-3.

Studies examining the impact of reference pricing (RP) on prescription drug utilization and spending, medical utilization and spending (16 studies)

| Author | Study sample | Study design | Drug benefit variation | Outcomes | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies that examine the impact on prescription drug utilization only | |||||

| Mabasa VH et al., 2006 | PPI prescriptions for Canadians with private employer-sponsored drug plans (Claims data June 2002-May 2005) | Before-after with control group |

One employer group adopted reference pricing for PPIs since June 2003, while other employer groups didn’t have reference pricing for PPIs through the whole study period | Number of days supplied Rx spending |

Introduction of reference-based pricing for PPIs in one employer in Canada reduced plan spending on PPIs by approximately 26%. Less than one third of the reduction was attributed to average price of PPIs and more than two thirds to a decline of utilization of PPIs. |

| Grootendorst PV et al., 2005 | British Columbia Pharmacare for the elderly (Aggregated data 1993–2001) |

Time series | Pharmacare introduced two types of RP for NSAIDs: Type I in Apr 1994 and Type II in Nov 1995. Under Type I RP, generic and brand versions of the same NSAIDs were exchangeable, under Type II RP, different NSAIDs were considered interchangeable. | Rx plan spending | Imposing reference pricing among all NSAIDS (Type 2 RP) achieved more savings compared to a reference pricing among each NSAID(Type 1 RP). After Type 2 RP, annual plan expenditures for NSAID were cut by $4 million (50%). Most savings accrued from the substitution of low-cost NSAIDs for most costly alternatives. About 20 percent of savings represented expenditures by seniors who paid cost-sharing NSAIDs. |

| Schneeweiss S et al., 2004 | British Columbia Pharmacare for the elderly (Aggregated data 1995–1998) |

Before-after no control group |

Introduction of reference pricing to ACE inhibitors in elderly BC residents in 1997 | Rx plan spending | RP to ACE inhibitors in elderly BC residents was associated with savings of CAN $6 million among continuing users and $0.2 million among new users, during the first year of the implementation. Approximately five sixths were achieved by utilization changes and one sixth by cost shifting to patients. There were no savings through drug price changes |

| Marshall JK et al., 2002 | BC Pharmacare beneficiaries (Aggregated data 1993–1999) |

Time series | Introduction of reference pricing to H2RAs and special authority for PPIs in elderly BC residents in 1995 | Number of defined daily doses per 10,000 beneficiaries OOP and plan drug spending per 10,000 beneficiaries |

RP for H2RAs and special authority for PPIs reduced plan expenditures by $1.8 to $3.2 million per year for H2RAs and $5.5 million per year for PPIs. Beneficiary contributions for H2RAs increased from negligible amount to approximately 16% of total drug expenditures |

| Schneeweiss S et al., 2002 | 119,074 BC Pharmacare beneficiaries who used ACE inhibitors from 1995–1998 (Administrative data 1995–1998) |

Longitudinal | Introduction of reference pricing to ACE inhibitors in elderly BC residents in 1997 | Number of prescriptions Plan Rx spending Rx switching Discontinuation rates |

RP for ACE inhibitors was associated with 11% reduction in use of all ACE inhibitors. But the use of overall antihypertensives was unchanged. The policy saved $6.7 million in pharmaceutical expenditures for existing users during its first 12 months. Relative to high-income patients, patients with low-income status were more likely to stop all antihypertensive therapy (OR 1.65) |

| Aronsson T et al., 2001 | Quarterly time-series data on prices and quantities for twelve brand-name drugs and their generic substitutes from 1972–1996 | Time series | Introduction of reference pricing in 1993 which specifies that any costs exceeding the price of the least expensive generic substitute by more than 10% must be borne by patients | Market share of brand-name drugs Relative price of brand-name versus generics |

Introduction of reference pricing was negatively associated with market shares for three brand-name drugs while positively associated with market shares for other two. Reference pricing was also associated with decreased relative price of brand-name versus generics. |

| Grootendorst PV et al., 2001 | BC Pharmacare for the elderly (Aggregated data 1994 – 1999) |

Before-after no control group |

Introduction of reference pricing to nitrates in elderly BC residents in 1995 | Monthly total number of prescriptions Plan and OOP Rx spending |

During three and a half years after introduction of RP for nitrates, BC Pharmacare expenditures on nitrates for the elderly declined by $14.9 million. Most of these savings were due to the lower prices that Pharmacare paid for restricted nitrates. Prescribing of reference-standard nitrates increased immediately after the policy was introduced but later dropped after nitroglycerin patch was exempted from additional charges. $1.2 million of the savings represented expenditures by senior citizens who bought restricted nitrates. There were no compensatory increases in expenditures for other anti-angina drugs |

| McManus P et al., 2001 | Prescriptions in Australia which were under government subsidy (Claims data 1990, 1994 and 1999) |

Before-after no control group |

Introduction of minimum pricing policy in Australia in 1990 and generic substitution policy in 1994 | Rx switching | After implementation of minimum pricing, share of generic drugs increased from zero in 1990 to 17% in 1994. Generic substitution policy further increased the share to 45% in 1999. |

| Narine L et al., 2001 | BC Pharmacare for the elderly (Aggregated data 1994–1996) |

Before-after no control group |

In 1995, the BC Pharmacare introduced a reference-based pricing (RBP) system for H2 antagonists, nitrates, and NSAIDs | Plan Rx spending Total number of prescriptions Rx switching |

Introduction of RBP was associated with a 44% decrease in Pharmacare drug costs. Total number of prescriptions for H2 antagonists and nitrates decreased by 5.2% and 2.5%, respectively. A significant number of patients were switching from one drug to the other after introduction of RBP. |

| Narine L et al., 1999 | BC Pharmacare (Aggregated data 1994 – 1996) |

Before-after no control group |

Introduction of reference pricing to H2RAs in elderly BC residents in 1995 | Annual total number of prescriptions Plan Rx spending |

In the year following the introduction of RP for H2RAs, the total number of prescriptions decreased by 5.2%, the market share of reference drug increased by 410%. Pharmacare expenditures for Histamine-2 receptor antagonists decreased by 38%. There was no substantial changes in drug prices |

| Jonsson B., 1994 | Swedish reimbursement system for drugs (Aggregated data 1992–1993) | Before-after no control group |

Introduction of a reference price system on Jan 1993 | Plan Rx spending OOP Rx spending |

During the first three months of the introduction of a reference system in Sweden, relative to the same period in the previous year, there was a slight decrease (1.6%) in total expenditure for the reimbursement scheme (NSIB) but a 14% increase for patient co-payments. |

| Studies that also examine the impact on medical utilization and spending | |||||

| Schneeweiss S et al., 2006 | 5 million BC elderly residents (Administrative data Jan 2002 to June 2004) | Longitudinal | Beginning at 2003, BC Pharmacare program only covered one PPI: rabeprazole, and imposed access restrictions on three leading PPIs | Defined daily doses per month Rx discontinuation rates Rx spending Gastrointestinal hemorrhage rates |

Within 6 months after policy change, 45% of all PPI users switched to the covered PPIs, and the provincial health plan saved at least Can $2.9 millions. There were no increased use of H2 blockers, discontinuation of gastroprotective drugs or hospitalizations for hemorrhage. |

| Schneeweiss S et al., 2004 | 5,463 patients covered by British Columbia Pharmacare with at least one prescriptions for a nebulised respiratory drug in the preceding 12 months (Administrative data Sep 1997 - Aug 1999) |

Randomized controlled trial Observational time series |

Since March 1999, Pharmacare restricted reimbursement for nebulised respiratory medications to patients with doctor’s exemption. Patients in the intervention group in a randomized control trial were not subject to this restriction for six months. | Rx utilization Rx spending Contacts with doctors and services Emergent admissions to hospitals |

both in the randomized control trial and the observational analysis found that restricting reimbursement for nebulised respiratory drugs was not associated with increase of unintended health outcomes, |

| Schneeweiss S et al., 2003 | 61,763 elderly British Columbia residents who were dihydropyridine CCBs users and covered by Pharmacare (Administrative data 1995–1997) |

Longitudinal | Introduction of reference pricing to dihydropyridine CCBs in elderly BC residents in 1997 | Median monthly doses Rx switching Hospital admissions ED visits Admissions to long-term care facilities |

RP to dihydropyridine CCBs was associated with increased use of fully-covered dihydropyridine CCBs and reduced total medical costs by Canadian $1.6 million in the first 12 months of implementation. Overall antihypertensive use did not decline, and there were no increases in hospitalizations, ED visits or long-term care admissions. |

| Hazlet TK et al., 2002 | 20,000 British Columbia Pharmacare beneficiaries exposed to Histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and other antisecretory drugs from 1993 through 1996 (Administrative data 1993–1996) |

Longitudinal | Introduction of reference pricing to H2RAs in elderly BC residents in 1995 | Number of prescriptions filled Hospital visits ED visits Hospital admissions Length of hospital stay |

RP to H2RAs in elderly BC residents was not associated with worsening health outcomes among antisecretory drug users. |

| Schneeweiss S et al., 2002 | 37,362 BC Pharmacare beneficiaries who used selective ACE inhibitors before the RP policy for ACE inhibitors (Administrative data 1995–1998) |

Longitudinal | Introduction of reference pricing to ACE inhibitors in elderly BC residents in 1997 | Hospital admissions ED visits Admissions to long0term care facilities RX plan spending |

RP for ACE inhibitors was not associated with cessation of treatment or changes in the rates of visits to physicians, hospitalizations, admissions to long-term care facilities, or mortality. Net savings were estimated to be $6 million during the first 12 months of reference pricing |

Few health plans in the U.S. have adopted reference pricing so far. However, it is widely used in parts of Canada and Europe. In general, almost all of the studies find large increases in use of drugs priced at or below the reference price and sharp declines in use of higher cost drugs that require some patient cost-sharing. In a series of studies of reference pricing in British Columbia (BC), Schneeweiss and colleagues found that an increase in copayments for the most expensive angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (drugs priced above the “reference price”) was not associated with stopping treatment for hypertension or higher health care utilization.123, 128, 129 They found similar effects on use of calcium channel blockers125 and proton pump inhibitors.121 The only potential concern raised by these studies was that low-income patients were more likely to stop hypertensive therapy than high- income patients (odds ratio, 1.65; 95% confidence interval, 1.43–1.89). Grootendorst and colleagues122, 131 examined similar policies for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and nitrates. They found that most of the savings to BC’s Pharmacare program could be explained by the substitution of low cost drugs and higher patient cost-sharing for restricted medications. The remaining studies listed in Table 3 found that reference pricing was only weakly correlated with overall use within the restricted drug class and uncorrelated with medical service use.

Prior Authorization and Formulary Restrictions

Increasingly, public and private health plans are imposing prior authorization and/or fail-first requirements on non-preferred prescription drugs. These programs require use of older or less expensive medications before covering newer therapies. For example, a plan may require a patient to try at least one generic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug before paying for a cox-2 inhibitor. The main concern about these cost containment policies is that patients may switch to less effective medications or become noncompliant, and, as a result, experience adverse health effects. Several studies, as summarized in Table 4, support such concerns. Two of the studies found that Medicaid beneficiaries taking a restricted statin medication filled fewer prescriptions and were more likely to be non-adherent than unrestricted patients.79, 84 Similar effects were found for antihypertensive medications.95 Another study found that a preferred drug list for cardiovascular medications was associated with an increase in outpatient visits in the first six months of implementation, but these differences did not persist over time.93

Table 4.

Studies examining the impact of prior authorization or formulary restrictions on drug utilization and spending, medical utilization and spending (41 studies)

| Author | Study sample | Study design | Drug benefit variation | Outcomes | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies that examine the impact on prescription drug utilization only | |||||

| Abdelgawad T et al., 2006 | Aggregated Measures (at county level) about prescriptions for Statins filled between Apr 2003 and May 2005 and paid by Medicaid in six states (Retail Pharmacy transaction records 2003–2005) |

Before-after with control group |

Three state Medicaid programs implemented Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs) for statins in Feb-Apr 2004 while the other three states didn’t. | Number of prescriptions filled |

Imposing PDLs for statins associated with reduced Medicaid prescription fills for statins |

| Carroll NV et al., 2006 | 104,568 fee-for-service patients enrolled in Medicaid programs of two states during year 2002 to 2003 |

Before-after with control group |

The state of Missouri initiated a prior authorization program for COX-2 inhibitors while the Medicaid program of a controlled state didn’t. | Rx spending Number of prescriptions filled |

Initiating a PA program for COX-2 inhibitors resulted in reduced use and expenditures for COX-2 inhibitors and reduced net expenditures for all pain and GI-protective medications. These effects were greatest for patients at low risk for GI complications |