Abstract

Rationale:

Atherosclerosis is in part caused by immune and inflammatory cell infiltration into the vascular wall, leading to enhanced inflammation and lipid accumulation in the aortic endothelium. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying this disease is critical for the development of new therapies. Our recent studies demonstrate that epsins, a family of ubiquitin-binding endocytic adaptors, are critical regulators of atherogenicity. Given the fundamental contribution lesion macrophages make to fuel atherosclerosis, whether and how myeloid specific epsins promote atherogenesis is an open and significant question.

Objective:

We will determine the role of myeloid specific epsins in regulating lesion macrophage function during atherosclerosis.

Methods and Results:

We engineered myeloid cell-specific epsins double knockout mice (LysM-DKO) on an ApoE−/− background. On Western diet, these mice exhibited marked decrease in atherosclerotic lesion formation, diminished immune and inflammatory cell content in aortas, and reduced necrotic core content but increased smooth muscle cell content in aortic root sections. Epsins deficiency hindered foam cell formation and suppressed pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype but increased efferocytosis and anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype in primary macrophages. Mechanistically, we show that epsins loss specifically increased total and surface levels of LRP-1, an efferocytosis receptor with anti-atherosclerotic properties. We further show that epsin and LRP-1 interact via epsin’s Ubiquitin Interacting Motif (UIM) domain. Oxidized LDL treatment increased LRP-1 ubiquitination, subsequent binding to epsin, and its internalization from the cell surface, suggesting that epsins promote the ubiquitin-dependent internalization and downregulation of LRP-1. Crossing ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice onto an LRP-1 heterozygous background restored, in part, atherosclerosis, suggesting that epsin-mediated LRP-1 downregulation in macrophages plays a pivotal role in propelling atherogenesis.

Conclusions:

Myeloid epsins promote atherogenesis by facilitating pro-inflammatory macrophage recruitment and inhibiting efferocytosis in part by downregulating LRP-1, implicating that targeting epsins in macrophages may serve as a novel therapeutic strategy to treat atherosclerosis.

Subject Terms: Atherosclerosis, Inflammation, Mechanisms

Keywords: Epsin, macrophage, atherosclerosis, LRP-1, inflammation, efferocytosis

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. with an alarming increase in prevalence in developing countries1,2. Atherosclerosis, the inflammatory process resulting in arterial plaque buildup, is the underlying cause of heart attack and stroke1,3. Despite the advance of therapies to lower lipids and reduce hypertension, cardiovascular disease and atherosclerosis continue to plague society. Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms involved in atheroma progression and associated inflammation is critical for the development of novel therapies to combat this devastating disease.

Macrophages play a critical role in the development and progression of atherosclerosis constituting the majority of cells within the atheroma1,4. Initially, macrophages are beneficial by ingesting oxidized LDL (oxLDL) and clearing it from the subendothelium5,6. However, they eventually become engorged with lipids resulting in dysregulated lipid metabolism and ultimately become lipid-laden foam cells4–7. When these foam cells die and are not cleared from the subendothelium, they contribute to necrotic core formation, which can lead to plaque rupture and thrombosis1. Macrophages expressing anti-inflammatory cytokines promote anti-inflammatory signaling to reduce the inflammatory environment of the plaque and contribute to plaque regression by participating in efferocytosis, the clearance of dying cells8. Furthermore, efferocytosis enhances anti-inflammatory signaling and cholesterol efflux within the phagocytic macrophage preventing it from turning into a pro-inflammatory foam cell9,10. Thus, tipping the balance of macrophage phenotype to an anti-inflammatory phenotype presents a significant therapeutic potential.

Epsins are a family of evolutionarily conserved, multi-domain containing proteins involved in clathrin mediated endocytosis11–15. Epsins 1 and 2 are ubiquitously expressed, while epsin 3 is expressed primarily in the stomach. Mice lacking either epsins 1 or 2 develop normally and exhibit no apparent phenotype suggesting that both are redundant in function11,12,16. Mice constitutively lacking epsins 1 and 2 are embryonic lethal due to vascular defects suggesting that epsins are required for normal development of the vasculature. However, mice with a global inducible knockout of epsins 1 and 2 develop normally12,16. We have previously shown that mice with an inducible endothelial cell-specific deletion of epsins 1 and 2 exhibit impaired tumor growth due to aberrant tumor angiogenesis demonstrating a role for epsins in the regulation of the vasculature11,12. Furthermore, recent genome wide-association studies have identified several genes involved in cancer that are associated with cardiovascular disease suggesting a possible involvement for epsins in cardiovascular disease17,18. In addition, it has been reported that epsin 1 binds to LDLR in a ubiquitin dependent manner19. While other reports as well as our data suggest this is not the case20, it suggests the possibility that epsins bind to proteins essential in the development of atherosclerosis.

Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1 (LRP-1) is a multifunctional and ubiquitously expressed member of the Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor Family consisting of a 515kDa extracellular chain non-covalently linked to an 85kDa chain with transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions21,22. The extracellular chain consists of 4 ligand binding domains that bind to over 40 different ligands22. Global knockout of LRP-1 is embryonic lethal23, but a myeloid-specific deletion of LRP-1 in atherosclerotic mouse models has been shown to exhibit increased atherosclerosis with macrophages that exhibit increased foam cell formation, increased expression of pro-inflammatory markers, and decreased efferocytosis of apoptotic cells24,25. Macrophage LRP-1 is also known to mediate efferocytosis, the phagocytosis of dying cells, by binding to receptors on the dying cell thereby mediating their phagocytosis24,26,27. Furthermore, the process of efferocytosis has been demonstrated to promote an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype9,10. Interestingly, this protein has also been shown to undergo ubiquitination and endocytosis28–31. Thus, deciphering the mechanisms that regulate LRP-1 expression in macrophages is an important step in developing new therapies for the treatment of atherosclerosis.

In this study, we investigate the potential role epsins play in regulating atherosclerosis using a unique mouse model with a myeloid-specific knockout of epsins (LysM-DKO). We discover that epsins are upregulated in macrophages of atherosclerotic mice. Furthermore, myeloid-specific epsins deficiency ameliorates the development of atherosclerosis and shifts macrophage phenotype to an anti-inflammatory phenotype while enhancing efferocytosis. Mechanistically, we found that epsins interact with ubiquitinated LRP-1. Without epsins, surface levels of LRP-1 are abundant in macrophages possibly resulting in enhanced efferocytosis and anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype, but reduced foam cell formation and ultimately reduced atherosclerosis. Genetically reducing the levels of LRP-1 in LysM-DKO mice in part restores the pro-inflammatory phenotype exhibited by WT macrophages. Thus, we propose a model in which epsins’ upregulation in atherosclerosis promotes LRP-1 downregulation thereby enhancing the development of atherosclerosis.

METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article and its online supplementary files. Complete methods are available in the Online Data Supplement.

RESULTS

Epsins are augmented in atherosclerosis.

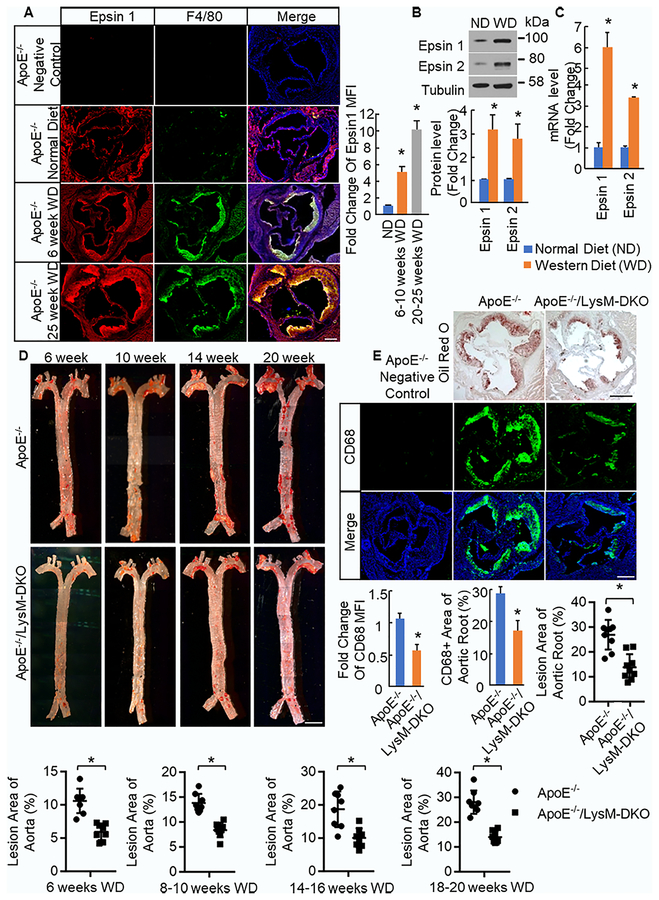

We have previously established that epsins play an important role in angiogenesis and tumor angiogenesis11,12,32,33. Recent genome-wide association studies have identified several genes for cancer that are also associated with coronary artery disease17,18, thus we hypothesized that epsins may play a critical role in atherosclerosis. Immunofluorescent staining for epsin 1 and CD68 (macrophage) in normal human aorta samples and atherosclerotic (AS) patient aorta samples demonstrated increased staining of both epsin 1 and CD68 as well as increased co-staining of epsin 1 and CD68 in atherosclerotic lesion samples compared to normal aorta samples (Online Figure I) suggesting that epsins are upregulated in human atherosclerotic lesions particularly in macrophage rich regions. Additionally, aortic root sections from ApoE−/− mice fed normal diet and Western diet (WD) were stained for epsin 1 and F4/80 (macrophage). The intensity of the epsin 1 staining in the F4/80 positive region of the plaque in mice fed WD was significantly greater than that of mice fed normal diet and increased with increased time on WD (Figure 1a). This suggests that epsin 1 expression is significantly increased in the macrophage rich region of lesions as atherosclerosis progresses. Furthermore, elicited peritoneal macrophages (Mϕs) were isolated from ApoE−/− mice on normal diet and WD. We found that the protein and mRNA expression of both epsin 1 and epsin 2 was upregulated in macrophages from mice fed WD (Figure 1b,c) again suggesting that epsins expression is significantly increased in macrophages in atherosclerosis.

Figure 1. Epsins are upregulated in atheromas and macrophages while epsins deficiency in myeloid cells ameliorates the development of atherosclerosis.

A. Aortic root sections from ApoE−/− mice fed normal diet (ND) (n=5) and Western diet (WD) (n=5) for 6–10 weeks or 20–25 weeks were stained for epsin 1 (red), F4/80 (macrophage, green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar=200μM. *WD group vs. ND group, P<0.01. B. Elicited peritoneal macrophages (Mϕs) from ApoE−/− fed ND (n=5) and WD (n=5) were lysed for Western blot (WB). Total protein levels of epsin 1 and epsin 2 were normalized to Tubulin. *WD group vs. ND group, P<0.01. C. RNA was isolated from elicited peritoneal Mϕs of ApoE−/− mice fed ND (n=5) and WD (n=5), cDNA made, and qPCR performed with primers for the indicated genes. *WD group vs. ND group, P<0.01. D. En face aortas from ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice fed Western diet for 6–7 weeks (n=8), 8–10 weeks (n=8), 14–16 weeks (n=8), and 18–20 weeks (n=8) were stained with Oil Red O. Scale bar=250μM. *ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO group vs. ApoE−/− group, P<0.01.E. Aortic root sections from ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice fed WD for 10 and 14 weeks were stained with Oil Red O (n=9) and CD68 (Mϕ) (n=11) respectively. *ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO group vs. ApoE−/− group, P<0.01.

Generation of myeloid-specific deletion of epsins 1 and 2 mice.

Given the importance of macrophages in the development and progression of atherosclerosis and our findings, we hypothesized that macrophage epsins play a crucial role in atherosclerosis. Thus, we generated a novel mouse model selectively, but constitutively, lacking epsin 1 in myeloid cells on an epsin 2 null background. We achieved this by crossing Epn1fl/fl;Epn2−/− mice11,16 with mice expressing a single copy of LysM Cre34. These mice were backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background to generate Epn1fl/fl;Epn2−/−;LysM Cre+/− (LysM-DKO) mice. Because epsins 1 and 2 are redundant in function, both epsins 1 and 2 were deleted. However, since double knock out of epsins 1 and 2 is embryonic lethal, only epsin 2 was deleted globally while epsin 1 was deleted selectively in myeloid cells using the cre lox system. Deletion of epsins 1 and 2 was validated in elicited peritoneal and bone marrow-derived Mϕs by Western blotting (Online Figure II)11,16,34.

To evaluate the role of myeloid epsins in the development of atherosclerosis, these mice were further crossed to ApoE−/− mice to generate the ApoE−/−;Epn1fl/fl;Epn2−/−;LysM-Cre+/− (ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO) mice. The ApoE−/− cohort of mice consists of ApoE−/−;epn1fl/fl;epn2−/− littermate controls lacking the single copy of LysM-cre, ApoE−/−/WT (Epn1+/+;Epn2+/+) mice, and ApoE−/−/WT mice with a single copy of LysM-cre, all of which exhibit no difference in phenotype. To induce atherosclerosis, ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice were fed WD beginning at 6 weeks of age for 6 or more weeks. Mice were then sacrificed and atherosclerosis evaluated. To ensure sufficient deletion of epsins, aortic root sections of ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice fed WD were stained for epsin 1 and F4/80. Epsin 1 staining is evident throughout the atheroma, or F4/80 positive area, of the ApoE−/− mice but only in the endothelial layer of the atheroma in ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice rather than throughout the F4/80 positive region suggesting that epsin 1 is deleted from macrophages in the atheroma (Online Figure IIIa). Furthermore, staining for epsin 2 and F4/80 demonstrated epsin 2 staining throughout the F4/80 positive region of the ApoE−/− lesion but an absence of epsin 2 staining throughout the ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO tissue (Online Figure IIIb).

Myeloid-specific deletion of epsins ameliorates atherosclerosis.

We analyzed the development and progression of atherosclerosis in the ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice fed WD. No change in plasma glucose, cholesterol levels, or triglyceride levels were observed in ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice fed WD for 14 to 16 weeks (Online Table III). Additionally, no change in circulating myeloid cells or immune and inflammatory cell populations in blood and bone marrow were observed (Online Table IV, Online Figure IV, V). Loss of myeloid epsins resulted in reduced Oil Red O staining in both en face aortas and aortic root sections of hearts, indicating reduced number of lesions, reduced lesion size, and ultimately a reduction in the progression of atherosclerosis (Figure 1d,e). Furthermore, this trend was reproduced at multiple timepoints between 6 and 20 weeks on Western diet through Oil Red O staining of en face aortas: lesion area increased in both ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO aortas over time but was consistently less in ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO aortas compared to ApoE−/− aortas (Figure 1d). This is also evidenced by reduced Bodipy (neutral lipids) staining in aortic root sections of ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice compared to ApoE−/− mice (Online Figure VI). Furthermore, loss of myeloid epsins resulted in a decrease in macrophage content within the atheroma as evidenced by reduced CD68 staining in aortic root sections (Figure 1e). Collectively, this data demonstrates that loss of myeloid epsins ameliorates the development and progression of atherosclerosis.

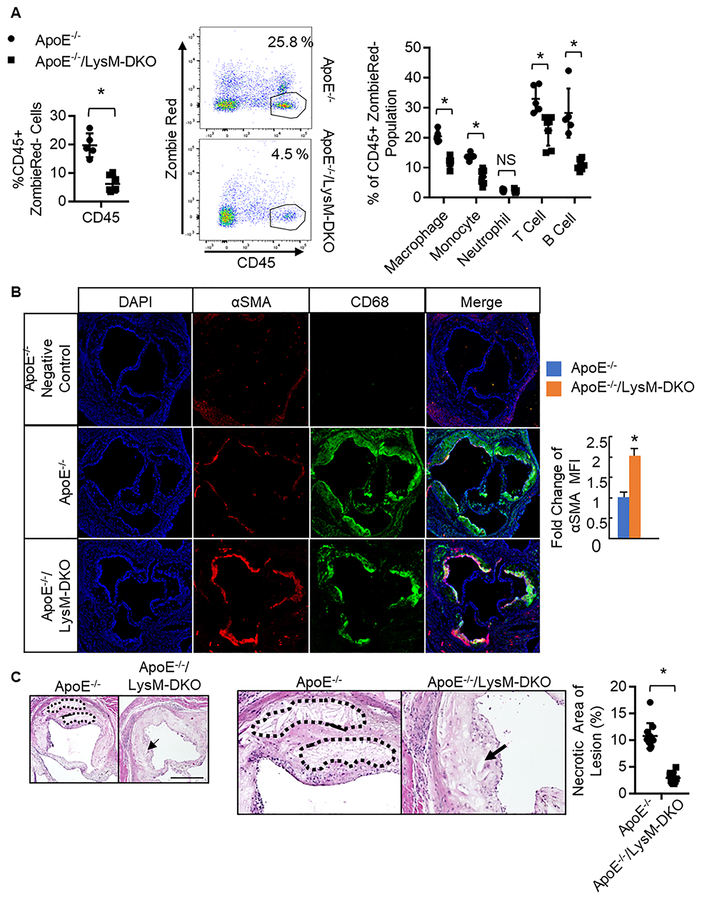

Myeloid-specific deletion of epsins enhances atheroma stability.

The reduction in CD68 staining in ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO aortic root sections not only suggests that these atheromas contain less macrophages but that these atheromas are more stable compared to ApoE−/− atheromas (Figure 1e). Hallmarks of a stable atheroma include reduced recruitment of immune and inflammatory cells, increased smooth muscle cell content within the cap area of the atheroma, as well as decreased apoptosis and necrosis within the atheroma8,35,36. To analyze atheroma stability in vivo, we analyzed the composition of immune and inflammatory cells in the aortas of both ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice fed Western diet. Cells from mouse aortas were isolated, stained with antibodies targeting immune and inflammatory cells, and analyzed via flow cytometry. We determined that the ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice have significantly reduced hematopoietic cell content compared to ApoE−/− mice as determined through CD45 staining (Figure 2a). We also see decreased content of subsets of these immune and inflammatory cells in the ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice compared to the ApoE−/− mice (Figure 2a, Online Figure V). Upon further analysis, we observed a decrease in pro-inflammatory monocyte populations and an increase in anti-inflammatory monocyte populations in aortas from ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice compared to that of ApoE−/− (Online Figure V, VII). These results suggest that the atheromas of ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice may contain fewer immune and inflammatory cells compared to ApoE−/− mice. While LysM-Cre does affect neutrophils, there was no change in neutrophil content within the aortas of ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice suggesting that there may be no phenotypic difference in this cell type. Furthermore, these cells constitute a much smaller portion of the cells within the aorta. We also found increased smooth muscle cell content within the cap area of the atheroma via Immunofluorescent (IF) staining of aortic root sections as well as decreased necrotic core area within the atheroma via H&E staining in aortic root sections in the ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice compared to ApoE−/− mice (Figure 2b,c). This further suggests that myeloid-specific epsins deficiency enables atheroma stability.

Figure 2. Myeloid-specific deletion of epsins decreases immune and inflammatory cell content in the aorta, increases smooth muscle cell content, and decreases necrotic core content within the atheroma.

A. Aortas from ApoE−/−(n=5) and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO (n=5) fed Western diet (WD) were isolated, digested, cells isolated, labeled with CD45 (hematopoietic cells), CD11b (granulocytes, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, NK cells), F4/80 (macrophage; F4/80+CD11b+ defined as macrophage), CD19 (B cells), TCRβ (T cells), Ly6C (monocytes), Ly6G (neutrophils defined as Ly6C+;Ly6G+), and analyzed via flow cytometry. *ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO group vs. ApoE−/− group, P<0.01. Aortic root sections from ApoE−/− (n=8) and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO (n=10) fed WD for 20 weeks (B) and 25 weeks (C) were stained with CD68 (macrophages, green) and α-Smooth Muscle Actin (αSMA) (red, smooth muscle cells) in B and H&E in C. Scale bar=200μM. *ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO group vs. ApoE−/− group, P<0.01.

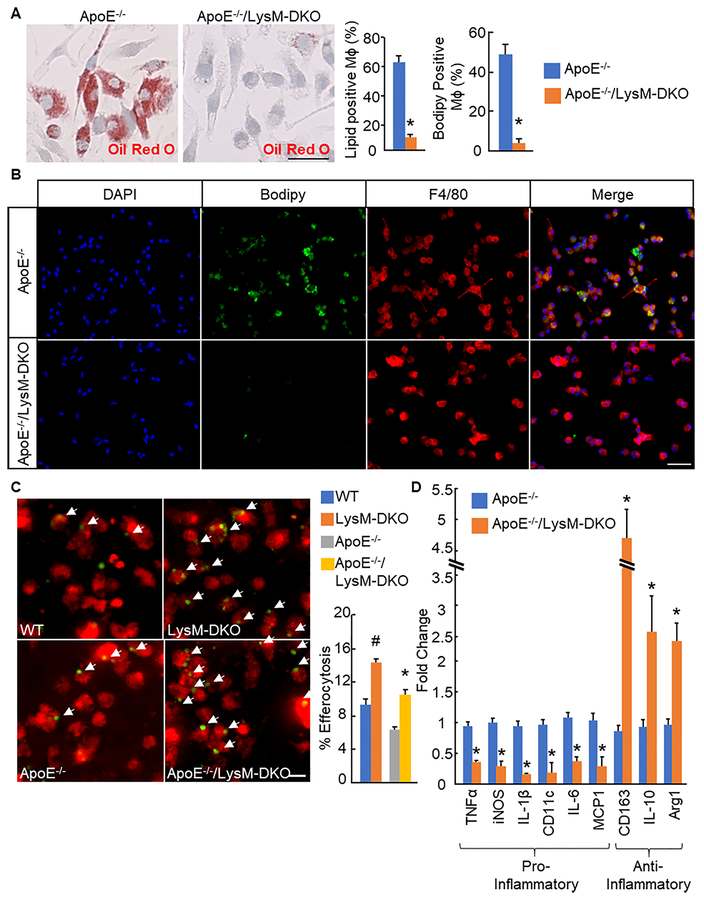

Myeloid-specific deletion of epsins reduces foam cell formation in primary macrophages by inducing macrophage efferocytosis and an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype.

To analyze the effect epsins deficiency had specifically on macrophages from these mice, we isolated primary macrophages from ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice on WD. Epsins deficiency resulted in a significant reduction in foam cell formation as demonstrated with Oil Red O staining of bone marrow-derived Mɸs treated with oxidized LDL (oxLDL) (Figure 3a). This was confirmed in elicited peritoneal macrophages from these mice as shown by a significant reduction in cells double positive for F4/80 and Bodipy37 (Figure 3b). We further confirmed ameliorated atherosclerosis and reduced foam cell formation in epsins deficient macrophages using primary macrophages from WT and LysM-DKO mice injected with PCSK9-AAV, which reduces LDLR levels in the liver and increases lipid levels in the mouse, and fed WD (Online Figure VIII)38. These mice also exhibited no change in cholesterol levels or circulating immune cells (Online Figure IX).

Figure 3. Myeloid-specific deletion of epsins reduces foam cell formation and promotes macrophage efferocytosis and an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype.

A. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (Mϕs) from ApoE−/− (n=7) and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO (n=7) mice fed Western diet (WD) and cultured with M-CSF were treated with oxLDL (25ug/ml, 24h) and stained with Oil Red O. Scale bar=50μM. B. Elicited peritoneal Mϕs from ApoE−/−(n=5) and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO (n=5) mice were treated with oxLDL (25ug/ml, 24h) and stained with Bodipy (lipids, green), F4/80 (Mϕs, red), and DAPI(blue). Scale bar=50μM. C. Primary elicited peritoneal Mϕs (n=10) were co-cultured with CFDA SE (green) labeled apoptotic WT thymocytes and labeled with CMTPX (red). Percent efferocytosis was quantified as the number of Mϕs with engulfed apoptotic cells as a percentage of total Mϕs. Scale bar=20μM. D. RNA was isolated from BMDMϕs (n=5), cDNA was made, and qPCR was performed using primer pairs for the indicated genes. *ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO group vs. ApoE−/− group, P<0.01; #LysM-DKO group vs. WT group, P<0.01.

Efferocytosis, the clearance of dead and dying cells by phagocytes, functions to remove dead cells from the plaque thereby preventing secondary necrosis and release of cytotoxic and inflammatory contents from dying cells8. To analyze the role of epsins deficiency on efferocytosis in vitro, green-labeled apoptotic WT thymocytes were co-cultured with red-labeled primary elicited peritoneal Mϕs from WT and LysM-DKO mice. In epsins deficient Mϕs, with or without an ApoE−/− background, the percentage of efferocytosis was dramatically increased compared to WT Mϕs (Figure 3c). To analyze efferocytosis in vivo, green-labeled apoptotic WT thymocytes were injected into WT and LysM-DKO mice 2 hours prior to harvesting elicited peritoneal Mϕs and analyzed via flow cytometry. Again, with or without the ApoE−/− background, epsins deficient Mϕs exhibited a significant increase in efferocytosis compared to WT Mϕs (Online Figure Xa).

Several studies have shown that macrophage efferocytosis stimulates signaling pathways within the phagocyte resulting in increased production and release of anti-inflammatory signals as well as the induction of anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype9,10. qPCR analysis of pro-inflammatory (TNFα, iNOS, IL-1β, CD11c, IL-6, and MCP-1) and anti-inflammatory markers (CD163, IL-10, and Arg1) showed that epsins deficiency reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory markers and increased the expression of anti-inflammatory markers in bone marrow-derived Mɸs (Figure 3d). Thus, epsins deficiency in macrophages promotes an anti-inflammatory phenotype in bone marrow-derived Mϕs. These results were repeated in bone marrow-derived Mϕs from ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice treated with the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα and primary non-elicited peritoneal Mɸs and bone marrow-derived Mɸs from non-atherosclerotic (ApoE+/+) mice (Online Figure Xb,c,d respectively). Epsins deficiency reduced foam cell formation and the pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype while enhancing the anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype and efferocytosis in primary Mϕs. These characteristics are indicators of stable atheromas that are unlikely to rupture8,35,36. Thus, these findings further suggest that atheromas of myeloid-specific epsins deficient mice may be more stable than those of ApoE−/− mice.

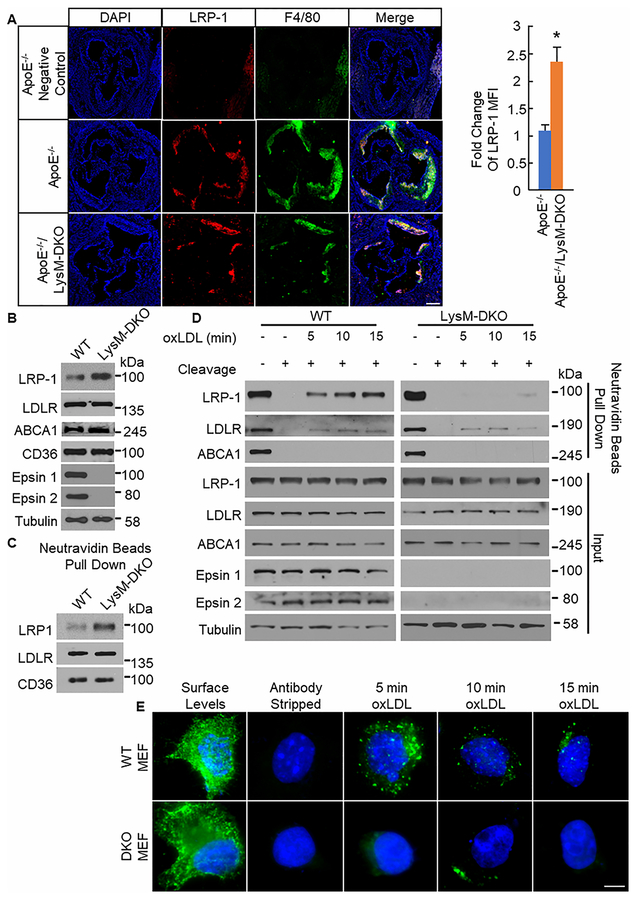

Myeloid-specific epsins deficiency augments total and surface protein levels of LRP-1.

Interestingly, atherosclerotic mice with myeloid-specific deletion of LRP-1 have been shown to have a phenotype that is the opposite of the ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO phenotype24,26,27. Given the negative correlation between atherosclerotic phenotypes of myeloid-specific deletion of LRP-1 and myeloid-specific deletion of epsins mice and epsins’ function as endocytic adaptors for ubiquitinated plasma membrane proteins11–15,24, we hypothesized that the phenotype of our myeloid-specific epsins deletion mice is due to increased LRP-1 surface and total protein levels in macrophages due to the absence of epsins-mediated downregulation of LRP-1. We analyzed protein levels of several surface receptors on macrophages that are involved in the development of atherosclerosis. Specifically, we observed LRP-1 staining with greater intensity in aortic root sections from ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice compared to ApoE−/− mice (Figure 4a). Furthermore, we saw increased protein levels of LRP-1 via Western blot in primary Mɸs from ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice compared to ApoE−/− mice but no change in other such proteins (Figure 4b, Online Figure XIa). LRP-1 is known to have anti-atherosclerotic and anti-inflammatory functions and its deletion from macrophages results in a dramatic increase in lesion size in ApoE−/− mice24. Furthermore, this protein has been shown to undergo both ubiquitination and endocytosis30,31. Thus, epsins may bind to ubiquitinated LRP-1 under inflammatory conditions resulting in the removal of LRP-1 from the macrophage cell surface and thereby reducing efferocytosis and promoting inflammation and the development of atherosclerosis. In fact, when the surface of macrophages from ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO and ApoE−/− mice were biotinylated and pulled down using Neutravidin beads, we saw a dramatic increase in the levels of biotinylated LRP-1 from ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO macrophages compared to ApoE−/− macrophages indicating increased surface levels of LRP-1 in the ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO macrophages compared to ApoE−/− (Figure 4c, Online Figure XIb). However, this change in total and surface levels of LRP-1 is not due to increased transcription of the LRP-1 gene as we see no increase in LRP-1 mRNA via qPCR (Online Figure XIc). Thus, when macrophages lack epsins, total LRP-1 levels increase and LRP-1 accumulates on the surface of the macrophages.

Figure 4. LRP-1 total and surface levels are increased with decreased internalization in plaques and macrophages from myeloid-specific epsins deficient mice.

A. Aortic root sections from ApoE−/− (n=8) and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO (n=8) mice fed Western diet (WD) for 14 weeks were stained with LRP-1 (red) and F4/80 (Mϕ, green). Scale bar=200μM. *ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO group vs. ApoE−/−, group, P<0.01. B. Elicited peritoneal Mϕs from WT (n=5) and LysM-DKO mice (n=5) were lysed forwestern blot (WB). C. Elicited peritoneal Mϕs from WT (n=3) and LysM-DKO (n=3) mice were biotinylated and processed for neutravidin beads pull down followed by WB. D. Elicited peritoneal Mϕs from WT (n=5) and LysM-DKO (n=5) mice were biotinylated, treated with or without oxLDL (10μg/mL) for indicated time points, and treated with or without cleavage buffer followed by processing for neutravidin beads pull down and WB. E. WT and DKO MEFs transfected with FLAG-tagged LRP1 were labeled with anti-FLAG antibodies. Cells were treated with oxLDL (10μg/mL) for the indicated time points followed by treatment with antibody stripping buffer and staining with secondary antibodies and DAPI. Images were taken at 60×. Scale bar=5μm.

Deficiency of epsins reduces LRP-1 internalization.

To determine if epsins interact with ubiquitinated LRP-1 to enable the internalization of LRP-1, we analyzed cell surface and internalized levels of LRP-1 in the presence and absence of epsins. Primary macrophages from WT and LysM-DKO mice in culture were biotinylated followed by treatment or no treatment with oxLDL to induce the internalization of LRP-1. Biotin was cleaved to determine internalized LRP-1 levels only and pulled down using Neutravidin beads. WT macrophages exhibited internalization of LRP-1 at 5, 10, and 15 minutes of oxLDL treatment. However, LysM-DKO macrophages exhibited a significant reduction in internalization of LRP-1 at any time point (Figure 4d, Online Figure XId). These results were confirmed using an antibody feeding assay with WT and epsins 1 and 2 DKO mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) transfected with FLAG-tagged LRP-1 plasmids with oxLDL treatment. We again observed internalization of LRP-1 in WT MEFs treated with oxLDL but little to no LRP-1 internalization in DKO MEFs treated with oxLDL (Figure 4e, Online Figure XII). These findings suggest that not only does oxLDL treatment promotes the ubiquitination of LRP-1 and its binding to epsins but also epsins-dependent internalization of LRP-1 thereby removing LRP-1 from the surface of the cells.

Epsin interacts with LRP-1 via the epsin UIM domain.

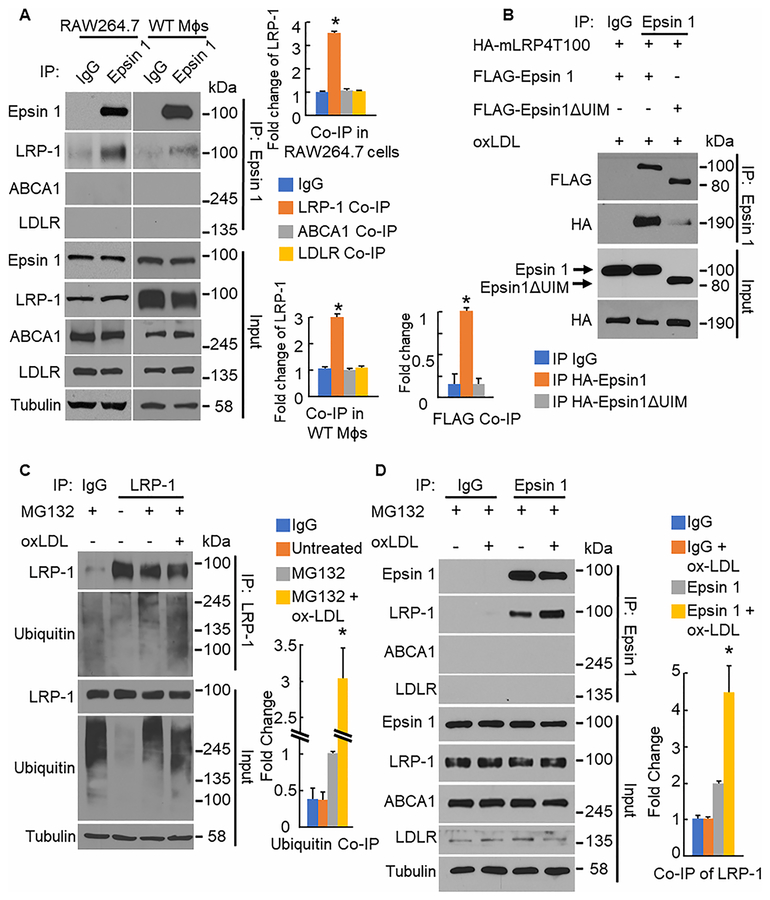

We next sought to determine how epsins and LRP-1 interact to cause this disparity in LRP-1 surface and total protein levels as well as internalization in macrophages from ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice. When WT bone marrow-derived Mϕs and RAW264.7 cells are lysed and processed for immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-epsin 1 antibodies, we saw co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) of LRP-1 (Figure 5a) indicating that epsin 1 and LRP-1 interact endogenously. Furthermore, this interaction between epsin 1 and LRP-1 appears to be specific as epsin 1 does not interact with other cell surface receptors such as LDLR, ABCA1, or CD36 in macrophages (Online Figure XIII). Similar results are obtained with the reciprocal IP (data not shown).

Figure 5. Macrophage epsin interacts with LRP-1 in a ubiquitin dependent manner.

A. RAW264.7 cells (n=3) and WT bone marrow-derived Mϕs (n=3) were lysed and processed for IP with anti-Epsin 1 antibodies followed by western blot (WB). *LRP-1 Co-IP group vs. IgG group, P<0.01. B. 293T cells (n=4) were transfected with full length Epsin1 or Epsin1ΔUIM and LRP-1 minireceptor (mLRP4T100) plasmids, treated with oxLDL(100–200ug/ml, 16h), lysed and processed for IP with anti-Epsin1 antibodies followed by WB. *HA-Epsin1ΔUIM group vs. HA-Epsin1group, P<0.01. C. RAW264.7 cells (n=4) were treated with MG132 (1uM,4h) and oxLDL(200ug/ml, 30min), lysed, and processed for IP with anti-LRP-1 antibodies followed by WB. *MG132+ox-LDL group vs. MG132 group, P<0.01.D. WT elicited peritoneal Mɸs (n=3) were treated with MG132 (1uM, 4h) and oxLDL(200μg/mL,30min), lysed, and processed for IP with anti-Epsin1 antibodies followed by WB. *Epsin 1+ox-LDL group vs. Epsin 1 group, P<0.01.

To determine if the binding between epsin 1 and LRP-1 is ubiquitin dependent, we analyzed the binding between LRP-1 and an epsin 1 construct lacking the ubiquitin interacting motif (Epsin1ΔUIM). We used an LRP-1 construct containing a truncated extracellular domain, which has been shown to function and traffic identically to the full length LRP-1 protein39,40. We recapitulated the binding between full length epsin 1 and LRP-1. However, binding between Epsin1ΔUIM and LRP-1 was significantly reduced suggesting that epsin’s ubiquitin interacting motif is essential for binding with LRP-1 (Figure 5b). Several studies have shown that LRP-1 is ubiquitinated in response to various stimuli30,31. We found that LRP-1 is ubiquitinated in RAW264.7 cells in response to oxLDL treatment in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Figure 5c). This suggests that, within the pro-inflammatory environment of the atheroma with abundant levels of oxLDL, LRP-1 is ubiquitinated. Additionally, we created a ubiquitin deficient LRP-1 plasmid by mutating three lysine residues in the cytoplasmic tail to arginine (Online Figure XIV). Furthermore, if we have increased ubiquitination of LRP-1 in response to a pro-inflammatory environment, then we should also see increased binding between LRP-1 and epsin 1 in this pro-inflammatory environment. We found that, upon oxLDL stimulation, the interaction between epsin 1 and LRP-1 is increased in primary WT Mɸs (Figure 5d) suggesting that within the pro-inflammatory environment of the atheroma, LRP-1 is ubiquitinated, bound to epsin, and internalized.

Genetic Reduction of LRP-1 in macrophage-specific epsins deficient mice restores atherosclerosis.

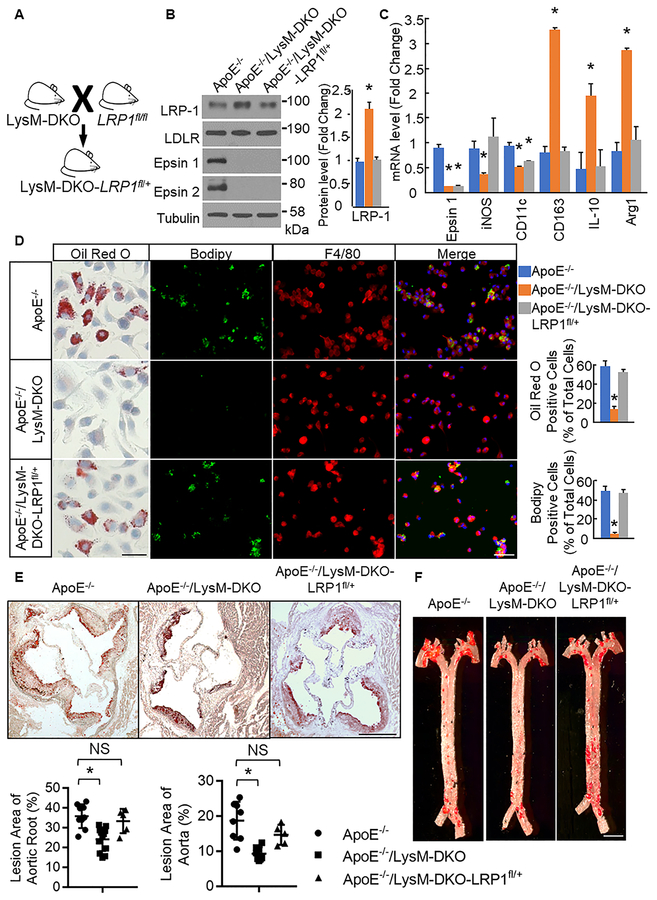

To confirm that the phenotype of the ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice is at least partially a result of increased LRP-1 total and surface protein levels due to loss of epsins, we crossed these mice with LRP-1fl/fl mice to create mice with myeloid-specific epsins deficiency and a myeloid-specific haploinsufficiency of LRP-1 (ApoE−/−;Epn1fl/fl;Epn2−/−;LysM Cre+/−;LRP1fl/+ or ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO-LRP1fl/+) (Figure 6a). By genetically reducing LRP-1 levels in the ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO macrophages, we aim to reduce LRP-1 levels in the ApoE−/−/LysM macrophages to levels similar to ApoE−/− macrophages and thus at least partially restore the phenotype of the ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice to the inflammatory and atherogenic phenotype of the ApoE−/− mice. To test this, we analyzed primary Mϕs from ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO-LRP1fl/+ mice fed WD via Western blot. We found that Mϕs from ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO-LRP1fl/+ mice exhibited reduced levels of total LRP-1 compared to ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO but no change compared to ApoE−/−. Total protein levels of other surface receptors were not significantly different compared to ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO macrophages (Figure 6b). Furthermore, ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO-LRP1fl/+ macrophages exhibited increased expression of a pro-inflammatory marker (iNOS) and decreased expression of anti-inflammatory markers (CD163, IL-10, Arg1) compared to ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO but no significant change compared to ApoE−/−. However, expression of pro-inflammatory marker CD11c was significantly decreased in ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO-LRP1fl/+ macrophages compared to ApoE−/− (Figure 6c). In addition, foam cell formation, as indicated by Oil Red O or Bodipy and F4/80 staining after oxLDL treatment, was increased in ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO-LRP1fl/+ macrophages compared to ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO macrophages with no change compared to ApoE−/− macrophages (Figure 6d). Thus, the haploinsufficiency of LRP-1 in the ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO at least partially restored the pro-inflammatory and foam cell phenotype of the ApoE−/− macrophages. Furthermore, plaque size within the aortic root and plaque area along the length of the aorta was increased in ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice with a myeloid-specific haploinsufficiency of LRP-1 compared to ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO with no change compared to ApoE−/− (Figure 6e,f). Thus, the myeloid-specific genetic reduction of LRP-1 in part restores the macrophage phenotype and gross phenotype of the ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice to the inflammatory and atherogenic phenotype of the ApoE−/− mice. This further confirms that the interaction between LRP-1 and epsins is essential in the development and progression of atherosclerosis.

Figure 6. Genetic reduction of LRP-1 in LysM-DKO mice restores the WT macrophage phenotype and the ApoE−/− atherogenic phenotype.

A. ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice were crossed with LRP-1fl/fl mice to generate ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO-LRP1fl/+ mice. B. Elicited peritoneal Mϕs (n=5) were isolated from mice with the indicated genotypes, lysed, and analyzed by western blot with indicated antibodies. Total protein levels were normalized to Tubulin. *ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO-LRP1fl/+ group vs. ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO group, P<0.01. C. RNA was isolated from bone marrow-derived Mϕs from WT(n=3), LysM-DKO(n=3), and LysM-DKO-LRPfl/+ (n=3)mice, cDNA was made, and qPCR was performed using primers for the indicated genes. *Compared with ApoE−/−group, P<0.01. D. Bone marrow-derived Mϕs and elicited peritoneal Mɸs from WT(n=5), LysM-DKO(n=5), and LysM-DKO-LRPfl/+ (n=5) mice were treated with oxLDL(25ug/ml, 24h) and stained with Oil Red O (bone marrow-derived Mɸs only) or Bodipy (lipids, green) and F4/80 (elicited peritoneal Mɸs, red). Scale bar=50μM. *ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO-LRP1fl/+ group vs. ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO group, P<0.01. E and F. Aortic root sections and en face aortas from ApoE−/− (n=8), ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO (n=8), and ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO-LRPfl/+ (n=5) mice fed Western diet for 14 weeks were stained with Oil Red O. Scale bar=200μM and 250μM respectively. *ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO group vs. ApoE−/− group, P<0.01.

DISCUSSION

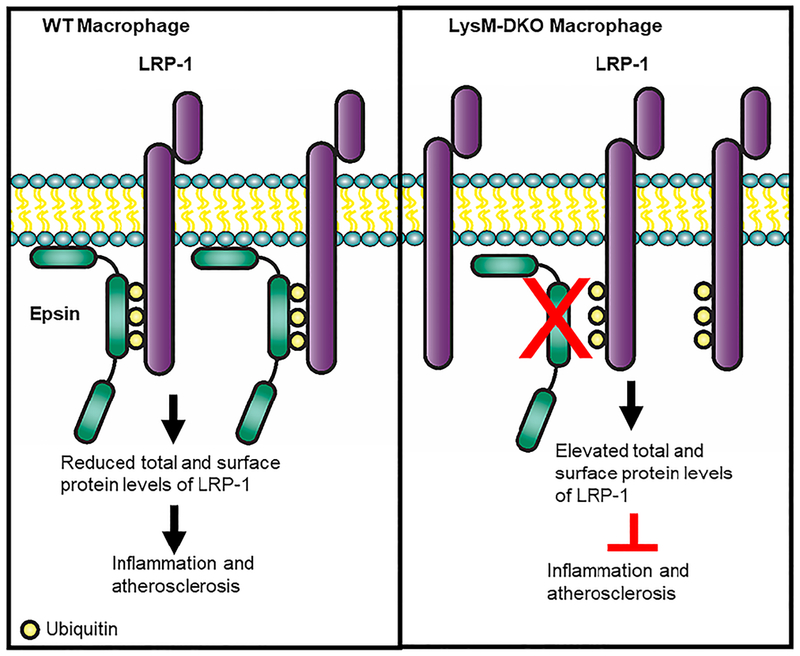

Several studies have demonstrated the importance of epsins in endothelial cells in the regulation of the vasculature both physiologically and pathologically11,12,32,33. However, the role of epsins in macrophages, a significant contributor to the progression of atherosclerosis, is unknown. This study revealed the critical role that epsins play in macrophages and their impact on the development and progression of atherosclerosis. Our findings demonstrate that epsins act in a pro-atherogenic fashion to downregulate receptors involved in reducing inflammation and plaque progression. Furthermore, we demonstrate a novel regulatory mechanism for LRP-1 in macrophages (Figure 7). We propose a model in which epsins bind ubiquitinated LRP-1 resulting in loss of LRP-1 from the cell surface leading to increased foam cell accumulation, decreased efferocytosis, increased inflammation, and further atheroma development. Thus, epsins are critical regulators of LRP-1 expression. However, what ubiquitin ligase ubiquitinates LRP-1 in this context is unknown and this determination will require future studies involving immunoprecipitations and/or siRNA knockdowns. Recent work from our lab has demonstrated that the transcription factor AP-1 enhances epsins expression under diabetic conditions41. Interestingly, AP-1 deficiency has been shown to be athero-protective in hyperlipidemic mice and has increased activation in progressive plaques42. Further studies will need to confirm if AP-1 enhances the transcription of epsins in macrophages in atherosclerotic conditions.

Figure 7.

Epsins interact with LRP-1 resulting in reduced total and surface levels of LRP-1 ultimately leading to increased inflammation and more atherosclerosis.

While it has been reported that epsins interact with the actin cytoskeleton, the role of this interaction in the development and progression of atherosclerosis and the function of macrophages is less clear43. Given this connection between epsins and the actin cytoskeleton, we suspect that epsins deficiency may affect non-receptor mediated lipid uptake, which predominates at levels of oxLDL that exceed receptor saturation and relies heavily on the actin cytoskeleton44. In addition, recent studies have linked autophagy to the actin cytoskeleton and have demonstrated that autophagy is deficient under atherosclerotic conditions45. Thus, further studies are needed to determine what role epsins play in the regulation of autophagy and autophagic flux.

Several studies have shown LRP-1 to be essential to efferocytosis, a process which clears dead cells and promotes plaque regression24,26,27. Importantly, we provide evidence that loss of myeloid epsins increases efferocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages in vitro and in vivo, demonstrating a critical role for macrophage epsins expression in efferocytosis, which may be mediated by its impact on LRP-1 expression. Interestingly, upregulation of LRP-1 with glucocorticoid treatment results in the upregulation of efferocytosis46. This supports a mechanism in which epsins deficiency promotes efferocytosis by upregulating LRP-1, while other proteins traffic LRP-1 to and from the cell surface and lysosomes during efferocytosis. Furthermore, LRP-1 downregulates cell surface expression of tumor necrosis factor 1 (TNFR1)25, which has been shown to upregulate inflammation and apoptosis47. Therefore, the increased expression of LRP-1 in epsins deficient macrophages is likely responsible for the anti-inflammatory phenotype of these macrophages. Future studies will be needed to determine any changes in total and surface protein levels of TNFR1 in WT and LysM-DKO macrophages to confirm that this anti-inflammatory effect of epsins deficiency does act through LRP-1’s downregulation of TNFR1. Decreased signaling of LRP-1 has been demonstrated to result in decreased ABCA1 expression via Akt induced PPARγ/LXR function48. Although we have not seen any significant changes to the ABCA1 expression levels in WT and LysM-DKO macrophages, additional studies will be needed to determine if there is any change in Akt signaling and/or cholesterol efflux in WT and LysM-DKO macrophages. Several publications have reported no phenotype for a cell type-specific haploinsufficient LRP-1 mice suggesting that the phenotype of these mice does not differ from that of control mice24,27. Thus, we suspect that the phenotype seen in ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO-LRP1fl/+ mice is due the reduced expression of LRP-1 in the LysM-DKO background rather than elimination of LRP-1.

We believe the interaction between LRP-1 and epsins to be specific. We have found no interaction between epsins and ABCA1, LDLR, or CD36. However, it is possible that epsins bind other receptors on the macrophage surface that act to reduce inflammation and plaque progression such as ABCG1, SR-BI, or MerTK. The phenotypes of mouse models with a reduction in any of these three proteins, either globally or myeloid-specific, are not only similar to each other but also in opposition to that of the ApoE−/−/LysM-DKO mice49–53. Thus, epsins may act through multiple receptors in macrophages. Efferocytosis receptors may overlap in function; however, removing just one efferocytosis receptor from macrophages results in a significant decrease in efferocytosis and an increase in inflammation and atheroma development. If epsins interact with multiple receptors, targeting epsins may provide a more robust treatment option than simply targeting one protein due to potential effects through several parallel pathways. Future studies will need to address the ability of epsins to bind or regulate any of these other proteins that play such an integral role in the development and progression of atherosclerosis.

Many current therapies used to treat patients with cardiovascular disease focus on ameliorating hypertension and lowering lipid levels. However, these treatments yield less than ideal results. New treatments that address the high levels of inflammation and cell death and low levels of dead cell clearance may help to fill this gap. Targeting a molecule such as epsins would potentially reduce macrophage lipid uptake, reduce macrophage pro-inflammatory phenotype, and increase efferocytosis ultimately reducing the progression of and risk for atherosclerosis. Furthermore, if epsins interact with more efferocytosis receptors than just LRP-1, epsins may have a more profound effect in diminishing atherosclerosis by acting through multiple pathways. In addition, adverse side effects from blocking epsins in adults is predicted to be minimal considering that adult mice with an inducible global knock out of epsins 1 and 2 exhibit no apparent defects under normal conditions16. Previous studies have shown that using a UIM peptide effectively blocks the interaction between epsins and VEGFR2 reducing tumor growth and metastasis with minimal toxicity in a mouse cancer model32,33. Thus, targeting this UIM peptide to macrophages holds significant promise as a potential therapeutic option in atherosclerosis. In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that epsins are critical regulators of inflammation and atherosclerosis and represent a potential novel therapeutic target for the development of treatments for atherosclerosis.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Macrophages are a major contributing cell type in inflammation and atherosclerosis.

Epsins play a role in the endocytosis and degradation of select proteins thereby regulating angiogenesis.

LRP-1 in macrophages promotes anti-inflammatory signaling and efferocytosis, while inhibiting the progression of atherosclerosis.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Using a new mouse model in which epsins are selectively deleted from myeloid cells, we show that epsins promote inflammatory macrophage phenotype and the development and progression of atherosclerosis.

Epsins deficiency in myeloid cells resulted in decreased plaque burden, increased plaque stability, and macrophages exhibiting reduced inflammation and lipid content and increased efferocytosis.

In the presence of pro-inflammatory stimuli, epsins bind to ubiquitinated LRP-1 removing LRP-1 from the surface of macrophages and thereby promoting inflammation and atherosclerosis.

Macrophages play an essential role in inflammatory processes that promote atherosclerosis. We deleted epsins from myeloid cells, including macrophages, in a mouse model of atherosclerosis and found a decrease in lesional macrophage content and overall plaque progression. Epsins deletion shifted macrophage phenotype from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory. Mechanistically, pro-inflammatory stimuli cause increased binding between LRP-1 and epsins resulting in the internalization of LRP-1 from the cell surface and its potential degradation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

We thank Dr. Kandice L. Tessneer for her contributions to this work in its early stages.

We thank Dr. Guojun Bu for providing the HA-tagged LRP-1 minireceptor.

We thank the Flow Cytometry Core at Boston Children’s Hospital for the use of the LSRII, the Viral Core at Boston Children’s Hospital for providing viral stocks, and the Rodent Histopathology Core at Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center for tissue processing and paraffin embedding services.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

These studies were funded in part by NIH grants R01 HL118676 and R01 HL137229 (H.C.), AHA grant 15EIA22210014 (H.C.), NIH NRSA F31HL127982 and AHA 15PRE21400010 (M.L.B.), AHA 17SDG33630161 (K.S.), AHA 17SDG33410868 (H.W.), and NIH grant R01 HL127173 (M.F.L., P.G.Y., H.T).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- Mɸ

macrophage

- DKO

epsins 1 and 2 double knockout mouse

- SKO

epsin 2 single knockout mouse

- UIM

ubiquitin interacting motif

- WT

wild type (Epn1+/+;Epn2+/+) mouse

- LRP-1

Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1

- oxLDL

oxidized low density lipoprotein

- LysM-DKO

Epn1fl/fl;Epn2−/−;LysM-cre+/− or myeloid-specific deletion of epsins 1 and 2 mouse

- WD

Western diet

- IP

Immunoprecipitation

- MEF

Mouse embryonic fibroblast

- WD

Western diet

- AS

Atherosclerotic (human patient)

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Libby P Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 32, 2045–2051, doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179705 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Writing Group M, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 133, e38–360, doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber C & Noels H Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med 17, 1410–1422, doi: 10.1038/nm.2538 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ & Fisher EA Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nat Rev Immunol 13, 709–721, doi: 10.1038/nri3520 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barthwal MK, Anzinger JJ, Xu Q, Bohnacker T, Wymann MP & Kruth HS Fluid-Phase Pinocytosis of Native Low Density Lipoprotein Promotes Murine M-CSF Differentiated Macrophage Foam Cell Formation. PloS one 8, e58054, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058054 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galkina E, Kadl A, Sanders J, Varughese D, Sarembock IJ & Ley K Lymphocyte recruitment into the aortic wall before and during development of atherosclerosis is partially L-selectin dependent. The Journal of experimental medicine 203, 1273–1282, doi: 10.1084/jem.20052205 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruth HS Sequestration of aggregated low-density lipoproteins by macrophages. Current opinion in lipidology 13, 483–488 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorp E & Tabas I Mechanisms and consequences of efferocytosis in advanced atherosclerosis. J Leukoc Biol 86, 1089–1095, doi: 10.1189/jlb.0209115 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korns D, Frasch SC, Fernandez-Boyanapalli R, Henson PM & Bratton DL Modulation of macrophage efferocytosis in inflammation. Front Immunol 2, 57, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00057 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voll RE, Herrmann M, Roth EA, Stach C, Kalden JR & Girkontaite I Immunosuppressive effects of apoptotic cells. Nature 390, 350–351, doi: 10.1038/37022 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasula S, Cai X, Dong Y et al. Endothelial epsin deficiency decreases tumor growth by enhancing VEGF signaling. J Clin Invest 122, 4424–4438, doi: 10.1172/JCI64537 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tessneer KL, Pasula S, Cai X, Dong Y, McManus J, Liu X, Yu L, Hahn S, Chang B, Chen Y, Griffin C, Xia L, Adams RH & Chen H Genetic reduction of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 rescues aberrant angiogenesis caused by epsin deficiency. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34, 331–337, doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302586 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H & De Camilli P The association of epsin with ubiquitinated cargo along the endocytic pathway is negatively regulated by its interaction with clathrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 2766–2771, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409719102 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen H, Fre S, Slepnev VI, Capua MR, Takei K, Butler MH, Di Fiore PP & De Camilli P Epsin is an EH-domain-binding protein implicated in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nature 394, 793–797, doi: 10.1038/29555 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenthal JA, Chen H, Slepnev VI, Pellegrini L, Salcini AE, Di Fiore PP & De Camilli P The epsins define a family of proteins that interact with components of the clathrin coat and contain a new protein module. J Biol Chem 274, 33959–33965 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen H, Ko G, Zatti A, Di Giacomo G, Liu L, Raiteri E, Perucco E, Collesi C, Min W, Zeiss C, De Camilli P & Cremona O Embryonic arrest at midgestation and disruption of Notch signaling produced by the absence of both epsin 1 and epsin 2 in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 13838–13843, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907008106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holdt LM & Teupser D Recent studies of the human chromosome 9p21 locus, which is associated with atherosclerosis in human populations. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32, 196–206, doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.232678 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schunkert H, Konig IR, Kathiresan S et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nature genetics 43, 333–338, doi: 10.1038/ng.784 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang YL, Yochem J, Bell L, Sorensen EB, Chen L & Conner SD Caenorhabditis elegans reveals a FxNPxY-independent low-density lipoprotein receptor internalization mechanism mediated by epsin1. Molecular biology of the cell 24, 308–318, doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-02-0163 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorrentino V, Nelson JK, Maspero E, Marques AR, Scheer L, Polo S & Zelcer N The LXR-IDOL axis defines a clathrin-, caveolae-, and dynamin-independent endocytic route for LDLR internalization and lysosomal degradation. Journal of lipid research 54, 2174–2184, doi: 10.1194/jlr.M037713 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boucher P & Herz J Signaling through LRP1: Protection from atherosclerosis and beyond. Biochemical pharmacology 81, 1–5, doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.09.018 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lillis AP, Van Duyn LB, Murphy-Ullrich JE & Strickland DK LDL receptor-related protein 1: unique tissue-specific functions revealed by selective gene knockout studies. Physiol Rev 88, 887–918, doi: 10.1152/physrev.00033.2007 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herz J, Clouthier DE & Hammer RE LDL receptor-related protein internalizes and degrades uPA-PAI-1 complexes and is essential for embryo implantation. Cell 71, 411–421 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yancey PG, Blakemore J, Ding L, Fan D, Overton CD, Zhang Y, Linton MF & Fazio S Macrophage LRP-1 controls plaque cellularity by regulating efferocytosis and Akt activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30, 787–795, doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.202051 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaultier A, Arandjelovic S, Niessen S, Overton CD, Linton MF, Fazio S, Campana WM, Cravatt BF 3rd & Gonias SL Regulation of tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 and the IKK-NF-kappaB pathway by LDL receptor-related protein explains the antiinflammatory activity of this receptor. Blood 111, 5316–5325, doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127613 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subramanian M, Hayes CD, Thome JJ, Thorp E, Matsushima GK, Herz J, Farber DL, Liu K, Lakshmana M & Tabas I An AXL/LRP-1/RANBP9 complex mediates DC efferocytosis and antigen cross-presentation in vivo. J Clin Invest 124, 1296–1308, doi: 10.1172/JCI72051 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yancey PG, Ding Y, Fan D, Blakemore JL, Zhang Y, Ding L, Zhang J, Linton MF & Fazio S Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 prevents early atherosclerosis by limiting lesional apoptosis and inflammatory Ly-6Chigh monocytosis: evidence that the effects are not apolipoprotein E dependent. Circulation 124, 454–464, doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.032268 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanai Y, Wang D & Hirokawa N KIF13B enhances the endocytosis of LRP1 by recruiting LRP1 to caveolae. J Cell Biol 204, 395–408, doi: 10.1083/jcb.201309066 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zemskov EA, Mikhailenko I, Strickland DK & Belkin AM Cell-surface transglutaminase undergoes internalization and lysosomal degradation: an essential role for LRP1. J Cell Sci 120, 3188–3199, doi: 10.1242/jcs.010397 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cal R, Garcia-Arguinzonis M, Revuelta-Lopez E, Castellano J, Padro T, Badimon L & Llorente-Cortes V Aggregated low-density lipoprotein induces LRP1 stabilization through E3 ubiquitin ligase CHFR downregulation in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33, 369–377, doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300748 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takayama Y, May P, Anderson RG & Herz J Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) controls endocytosis and c-CBL-mediated ubiquitination of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFR beta). J Biol Chem 280, 18504–18510, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410265200 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong Y, Wu H, Rahman HN et al. Motif mimetic of epsin perturbs tumor growth and metastasis. J Clin Invest 125, 4349–4364, doi: 10.1172/JCI80349 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahman HN, Wu H, Dong Y et al. Selective Targeting of a Novel Epsin-VEGFR2 Interaction Promotes VEGF-Mediated Angiogenesis. Circ Res 118, 957–969, doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307679 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clausen BE, Burkhardt C, Reith W, Renkawitz R & Forster I Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res 8, 265–277 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore KJ & Tabas I Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell 145, 341–355, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.005 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tabas I, Garcia-Cardena G & Owens GK Recent insights into the cellular biology of atherosclerosis. J Cell Biol 209, 13–22, doi: 10.1083/jcb.201412052 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dorh N, Zhu S, Dhungana KB, Pati R, Luo FT, Liu H & Tiwari A BODIPY-Based Fluorescent Probes for Sensing Protein Surface-Hydrophobicity. Sci Rep 5, 18337, doi: 10.1038/srep18337 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bjorklund MM, Hollensen AK, Hagensen MK, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Christoffersen C, Mikkelsen JG & Bentzon JF Induction of atherosclerosis in mice and hamsters without germline genetic engineering. Circ Res 114, 1684–1689, doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302937 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Marzolo MP, van Kerkhof P, Strous GJ & Bu G The YXXL motif, but not the two NPXY motifs, serves as the dominant endocytosis signal for low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem 275, 17187–17194, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000490200 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zilberberg A, Yaniv A & Gazit A The low density lipoprotein receptor-1, LRP1, interacts with the human frizzled-1 (HFz1) and down-regulates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 279, 17535–17542, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311292200 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu H, Rahman HNA, Dong Y et al. Epsin deficiency promotes lymphangiogenesis through regulation of VEGFR3 degradation in diabetes. J Clin Invest, doi: 10.1172/JCI96063 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meijer CA, Le Haen PA, van Dijk RA, Hira M, Hamming JF, van Bockel JH & Lindeman JH Activator protein-1 (AP-1) signalling in human atherosclerosis: results of a systematic evaluation and intervention study. Clin Sci (Lond) 122, 421–428, doi: 10.1042/CS20110234 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wendland B, Steece KE & Emr SD Yeast epsins contain an essential N-terminal ENTH domain, bind clathrin and are required for endocytosis. EMBO J 18, 4383–4393, doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4383 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kruth HS Receptor-independent fluid-phase pinocytosis mechanisms for induction of foam cell formation with native low-density lipoprotein particles. Current opinion in lipidology 22, 386–393, doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32834adadb (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coutts AS & La Thangue NB Actin nucleation by WH2 domains at the autophagosome. Nat Commun 6, 7888, doi: 10.1038/ncomms8888 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nilsson A, Vesterlund L & Oldenborg PA Macrophage expression of LRP1, a receptor for apoptotic cells and unopsonized erythrocytes, can be regulated by glucocorticoids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 417, 1304–1309, doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.137 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ting AT & Bertrand MJ More to Life than NF-kappaB in TNFR1 Signaling. Trends Immunol 37, 535–545, doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.06.002 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xian X, Ding Y, Dieckmann M, Zhou L, Plattner F, Liu M, Parks JS, Hammer RE, Boucher P, Tsai S & Herz J LRP1 integrates murine macrophage cholesterol homeostasis and inflammatory responses in atherosclerosis. Elife 6, doi: 10.7554/eLife.29292 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ait-Oufella H, Horvat B, Kerdiles Y, Herbin O, Gourdy P, Khallou-Laschet J, Merval R, Esposito B, Tedgui A & Mallat Z Measles virus nucleoprotein induces a regulatory immune response and reduces atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation 116, 1707–1713, doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699470 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tao H, Yancey PG, Babaev VR, Blakemore JL, Zhang Y, Ding L, Fazio S & Linton MF Macrophage SR-BI mediates efferocytosis via Src/PI3K/Rac1 signaling and reduces atherosclerotic lesion necrosis. Journal of lipid research 56, 1449–1460, doi: 10.1194/jlr.M056689 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thorp E, Cui D, Schrijvers DM, Kuriakose G & Tabas I Mertk receptor mutation reduces efferocytosis efficiency and promotes apoptotic cell accumulation and plaque necrosis in atherosclerotic lesions of apoe−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28, 1421–1428, doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.167197 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Westerterp M, Murphy AJ, Wang M et al. Deficiency of ATP-binding cassette transporters A1 and G1 in macrophages increases inflammation and accelerates atherosclerosis in mice. Circ Res 112, 1456–1465, doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301086 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yvan-Charvet L, Pagler TA, Seimon TA, Thorp E, Welch CL, Witztum JL, Tabas I & Tall AR ABCA1 and ABCG1 protect against oxidative stress-induced macrophage apoptosis during efferocytosis. Circ Res 106, 1861–1869, doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217281 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.