Abstract

Background

Recurrent laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas (LSCCs) are associated with poor outcomes, without reliable biomarkers to identify patients who may benefit from adjuvant therapies. Given the emergence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) as a biomarker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, we generated predictive models to understand the utility of CD4+, CD8+ and/or CD103+ TIL status in patients with advanced LSCC.

Methods

Tissue microarrays were constructed from salvage laryngectomy specimens of 183 patients with recurrent/persistent LSCC and independently stained for CD4+, CD8+, and CD103+ TIL content. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was employed to assess combinations of CD4+, CD8+, and CD103+ TIL levels for prediction of overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival (DSS), and disease-free survival (DFS) in patients with recurrent/persistent LSCC.

Results

High tumor CD103+ TIL content was associated with significantly improved OS, DSS, and DFS and was a stronger predictor of survival in recurrent/persistent LSCC than either high CD8+ or CD4+ TIL content. On multivariate analysis, an “immune-rich” phenotype, in which tumors were enriched for both CD103+ and CD4+ TILs, conferred a survival benefit (OS hazard ratio: 0.28, p = 0.0014; DSS hazard ratio: 0.09, p = 0.0015; DFS hazard ratio: 0.18, p = 0.0018) in recurrent/persistent LSCC.

Conclusions

An immune profile driven by CD103+ TIL content, alone and in combination with CD4+ TIL content, is a prognostic biomarker of survival in patients with recurrent/persistent LSCC. Predictive models described herein may thus prove valuable in prognostic stratification and lead to personalized treatment paradigms for this patient population.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-018-2256-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: CD103, Resident memory, T-cell, HNSCC, Larynx

Introduction

Advanced stage laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) remains a clinical challenge, with recurrence rates of up to 50% after primary radiation (RT) or chemoradiation (CRT) [1]. For patients with recurrent disease after RT/CRT, salvage surgery is often the only established curative option [2, 3]. However, operative morbidity is significant and survival rates after salvage laryngectomy are poor [4, 5]. The significant proportion of patients who develop recurrence after RT/CRT and the poor prognosis for patients with recurrent LSCC provide the rationale for new biomarker studies to improve prognostication and treatment selection in this vulnerable cohort. Although a variety of biomarkers ranging from genetic alterations [6], to protein expression [7], to tumor-infiltrating cells [8–13] have been evaluated in this population, no prognostic model has demonstrated sufficient sensitivity and specificity to warrant further evaluation in prospective cohorts or to dictate clinical decisions.

Despite the dearth of prognostic data within this population, the role of the adaptive immune system in tumor surveillance has emerged as an area of increasing interest for development of predictive assays of oncologic outcomes in patients with LSCC [14]. Certain immunologic signatures, including number of CD4+ and CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), portend improved survival and response to therapy in head and neck cancer [8, 9]. For example, we have recently shown that a higher proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ TILs correlates with improved disease-specific and disease-free survival (DFS) in patients with recurrent/persistent LSCC [9]. Subsequently, in order to further enhance the sensitivity and specificity of our model, we questioned whether prognostication in this cohort could be improved by considering immunologic biomarkers of cytotoxic TIL activity and tumor-cell kill, in addition to TIL number itself.

CD103, or αEβ7 integrin, localizes antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes to epithelial tissues and is an indicator of enhanced cytotoxicity and proliferative ability of these cells [14]. In recent studies of non-small cell lung cancer [15] and serous ovarian cancer [16, 17], the survival benefit conferred by CD8+ TILs was shown to be dependent upon co-expression of CD103. Thus, we sought to address whether CD103 expression may better define the most beneficial subsets of TILs with important prognostic and immunotherapeutic implications in patients with recurrent/persistent LSCC.

Herein, we evaluated the potential of CD103+ TIL density to act as a robust predictor of improved survival in patients with recurrent/persistent LSCC. Further, we hypothesize that there are patients with distinct immunologic phenotypes of “immune-rich” and “immune-poor” tumors that predict survival in recurrent/persistent LSCC.

Materials and methods

Patient population

We performed a single-institution, retrospective analysis of patients with recurrent/persistent LSCC using a clinical epidemiology and tissue database. Inclusion criteria stipulated: (1) adults with biopsy-proven LSCC; (2) recurrent/persistent disease at the primary site after RT or CRT; (3) laryngectomy for surgical salvage; between 1997 and 2014 and (4) tumor tissue available for creation of tissue microarray, as previously described [9]. In total, 183 patients met inclusion criteria, and demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients were staged in accordance with the 7th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging System [18].

Table 1.

Characteristics of recurrent/persistent LSCC patient cohort

| (n = 183) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 153 (83.6) |

| Female | 30 (16.4) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 161 (88.0) |

| Black/other/unknown | 22 (12.0) |

| Age at initial tumor (years) | 58.63 |

| Initial clinical stage | |

| I | 46 (25.1) |

| II | 54 (29.5) |

| III | 44 (24.0) |

| IV | 25 (13.7) |

| Unknown | 14 (7.7) |

| Initial treatment | |

| RT | 112 (61.2) |

| CRT | 71 (38.8) |

| Age at recurrence (years) | 60.87 |

| Time to recurrence (months) | 23.48 |

| Recurrent pathologic stage | |

| I | 6 (3.3) |

| II | 53 (29.0) |

| III | 48 (26.2) |

| IV | 76 (41.5) |

Immunohistology

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks from salvage surgery and representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides were assessed for ≥ 70% tumor cellularity by a head and neck pathologist (Jonathan B. McHugh). A tissue microarray (TMA) was subsequently constructed with triplicate 0.7-mm-diameter cores from each patient [19].

TMAs were stained for CD4+, CD8+, and CD103+ TILs on arrays constructed as previously described [9]. Briefly, 5-micron tissue sections were incubated overnight in a 65 °C oven, then deparaffinized and rehydrated with stepwise xylene, graded alcohols, and buffer immersion. Heat-induced epitope retrieval was then performed, followed by incubation of the slides in a preheated pressure cooker with citrate buffer (pH 6) or Tris–EDTA buffer (Ph 9) and horse serum. Immunohistochemical staining was done with a DAKO autostainer using liquid streptavidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex and DBA (DAKO labeled avidin-biotin-peroxidase kits, Thermo Fisher Scientific) as chromogens, as previously described [9]. Deparaffinized sections were stained with monoclonal antibodies at the following titrations: CD103-1:500 (Abcam Ab129202); CD4-1:250 (Abcam Ab846); CD8-1:40 (Novocastra VP-C320). TMA slides were digitally imaged, scanned, and retrieved with Aperio ImageScope v.12 software (Leica Biosystems).

TIL scoring and statistical analysis

Cores consisting of < 50% tumor parenchyma, partial cores, and those with significant tumor necrosis were excluded from the analysis. The positively stained cells in each included core were manually counted at 200× magnification (20× objective lens) by two independent blinded reviewers (Jacqueline E. Mann and Joshua D. Smith). Inter-rater reliability was determined by calculation of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) using R. Only intratumoral TILs were quantified, consistent with the biological function of the CD103 antigen and previous studies demonstrating reliability and reproducibility of this measurement parameter [14, 16, 17]. Mean TIL counts per core of triplicate samples for each patient were calculated, averaged between the two reviewers, and used in subsequent statistical analysis.

CD4+, CD8+, and CD103+ TIL counts were first input as continuous variables into univariate and multivariate models to document that each marker was a significant predictor of OS, DSS, and DFS. Next, optimal cutpoints for each TIL marker were determined from the data to maximize survival differences based on Cox proportional hazards regression of DSS using the survMisc v0.5.4 package in R [20]. Subsequently, combinations of the markers CD4, CD8 and CD103 were explored with multivariable Cox model and ROC analysis.

Deaths were confirmed through the electronic medical record and the Social Security Death Index. Primary outcome measures were overall survival (OS; time from salvage laryngectomy to death from any cause), disease-specific survival (DSS; time from salvage laryngectomy to death from any disease recurrence/persistence), and disease-free survival (DFS; time from salvage laryngectomy to any disease recurrence/persistence).

Results

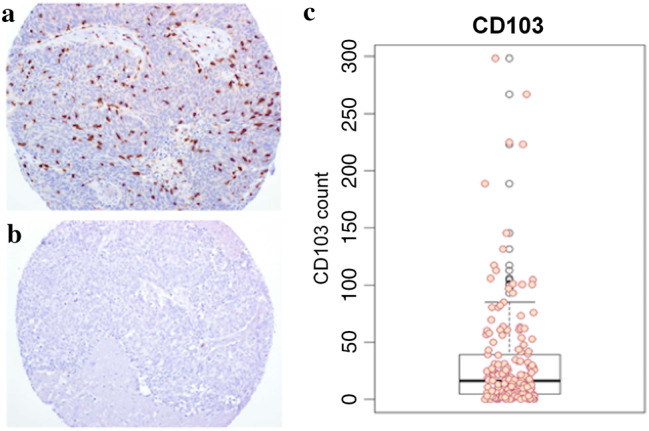

CD103 staining patterns and TIL cutpoints

For our entire cohort, the mean (range) CD103+ TIL count per tumor was 32.1 (0–298) and the median count was 16 (Fig. 1). Inter-rater reliability for TIL counts between the two blinded reviewers was excellent (ICC: 0.919, 95% CI 0.906–0.930). As continuous variables, CD4+, CD8+, and CD103+ TIL counts were each predictive of OS, DSS, and DFS (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

CD103 staining patterns and TIL counts. Representative stains from CD103+ high (a) and low (b) TIL tumor specimens from our TMA (magnification ×20). A box and whisker plot of TIL counts was constructed (c) with mean CD103+ TIL count of 32.1 and median count of 16

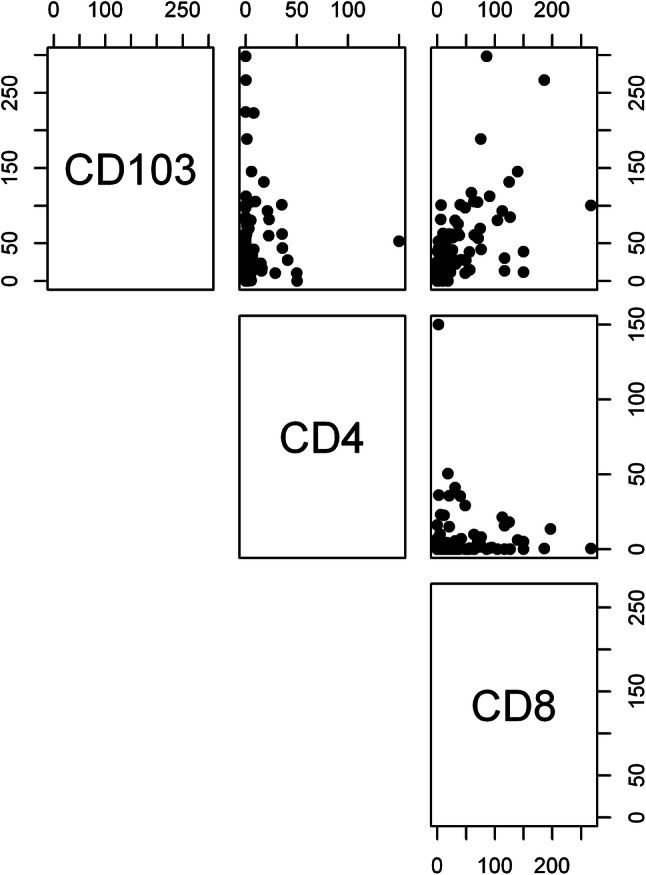

We then determined the optimal cutpoint for CD103+ TIL counts to allow for stratification of recurrent/persistent LSCC into CD103+ low (< 11 TILs) and CD103+ high groups (≥ 11 TILs) optimized for DSS [20]. Of our entire cohort (n = 183), ten (5.5%) tumors were excluded due to partial or absent tumor cores, yielding 69 (40%) CD103+ low tumors and 104 (60%) CD103+ high tumors. In a similar fashion, we determined optimal cutpoints for CD4+ and CD8+ TIL counts to stratify low and high groups with respect to these T-cell markers. CD4+ high tumors were defined as having greater than or equal to 3 TILs, yielding 36 (26%) CD4+ high and 101 (74%) CD4+ low tumors in our cohort after excluding 46 due to partial or absent tumor cores. Finally, the CD8+ cutpoint was determined to be greater than or equal to 12 TILs, yielding 63 (41%) CD8+ high and 92 (59%) CD8+ low tumors in our cohort after excluding 28 due to partial or absent tumor cores. Each of the three dichotomized T-cell markers alone was correlated strongly with DSS (Supplemental Figure). We had previously noted this for CD4+ and CD8+ TILs [9], but identified a new stronger association with CD103 status and DSS (p < 0.0001). Importantly, we noted significant correlation between CD8+ and CD103+ TIL content, confirming a unique population of cytotoxic T-cells that co-express these markers in recurrent/persistent LSCC (Pearson rho = 0.62, p < 0.0001). There was no similar overlap between CD4 and CD103 expression (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of co-expression of TIL markers in tumors. Comparing CD103+, CD4+, and CD8+ TIL counts for each tumor specimen, we identified a strong overlap between CD103+ and CD8+ TIL expression status (Pearson rho = 0.62, p < 0.0001). There was no correlation between CD4+ expression status and CD103+/CD8+ TIL expression status

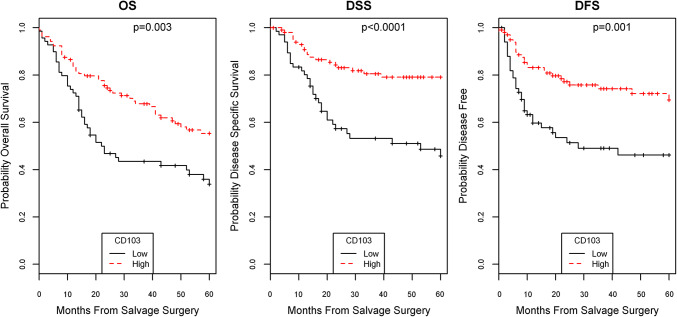

Univariate analysis of CD103+ TILs on survival

We next performed univariate analysis to assess the prognostic value of CD103+ TILs with respect to all three survival outcomes in patients with recurrent/persistent LSCC. Cox proportional hazards models found that patients with CD103+ high TILs had a better OS (p = 0.003), DSS (p < 0.0001), and DFS (p = 0.001) in comparison to patients with CD103+ low TILs (Fig. 3). In comparing CD103 with CD8 on prognostication of survival, CD103 status more strongly predicted survival. Thus, we continued forward with CD103 in multivariate analysis.

Fig. 3.

CD103 status association with survival. On univariate analysis, CD103+ high TIL status was strongly predictive of improved OS (p = 0.003), DSS (p < 0.0001), and DFS (p = 0.001)

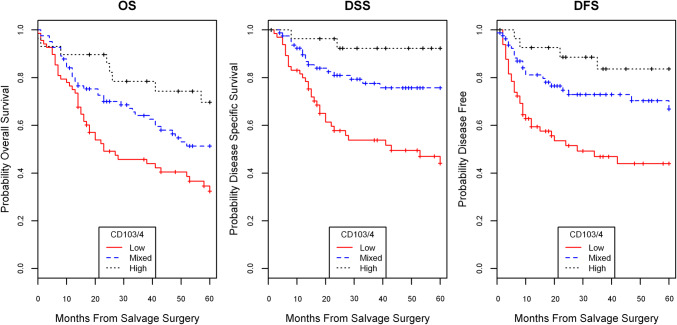

Multivariate analysis of CD103 and other predictors of survival

Next, we performed multivariate analysis in order to account for additional variables that have a prognostic survival value. We included variables previously validated in our cohort to be predictive of survival, namely CD4+ TILs, ACE-27 comorbidity status and node positivity [5, 9]. We found an interrelated effect between CD103+ and CD4+ TIL content, such that these variables combined were more predictive of survival parameters than either CD103+ or CD4+ TILs alone. Using the TIL cutpoint modeling described above, tumors were stratified into three groups: CD103+/4+ low (neither CD103+ or CD4+ high), CD103+/4+ mixed (either CD103+ or CD4+ high), and CD103+/4+ high staining (both CD103+ and CD4+ high). In univariate and multivariate modeling, high and mixed CD103+/4+ status were strong predictors of improved OS, DSS, and DFS in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 4; Table 2). These models with combined CD103+/4+ status had good predictive value with c-indices of 0.75, 0.71, and 0.76, respectively, for DSS, OS, and DFS.

Fig. 4.

CD103/4 status association with survival. CD103 and CD4 status stratified into high (both CD103+ and CD4+ high TIL status), mixed (either CD103+ or CD4+ high TIL status), or low (both CD103+ and CD4+ low TIL status) demonstrated significant association with OS, DSS, and DFS, with high the best prognosis, mixed with moderate prognosis, and low with poor prognosis

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of CD103/4 status and survival

| Variable | OS | DSS | DFS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

| pN0 status | 0.31 (0.20–0.49) | < 0.0001 | 0.24 (0.14–0.43) | < 0.0001 | 0.22 (0.13–0.38) | < 0.0001 |

| pN+ | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| ACE27 Grade 0 | 0.20 (0.09–0.49) | 0.0004 | 0.30 (0.08–1.10) | 0.07 | 0.44 (0.14–1.37) | 0.16 |

| ACE27 Grade 1 | 0.23 (0.10–0.50) | 0.0002 | 0.27 (0.08–0.95) | 0.04 | 0.29 (0.10–0.84) | 0.02 |

| ACE27 Grade 2 | 0.24 (0.10–0.58) | 0.0014 | 0.26 (0.07–1.01) | 0.05 | 0.24 (0.07–0.79) | 0.02 |

| ACE27 Grade 3 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| CD103/4 mixed | 0.51 (0.33–0.80) | 0.0036 | 0.32 (0.18–0.59) | 0.0002 | 0.39 (0.23–0.69) | 0.0009 |

| CD103/4 high | 0.28 (0.13–0.61) | 0.0014 | 0.09 (0.02–0.41) | 0.0015 | 0.18 (0.06–0.53) | 0.0018 |

| CD103/4 low | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| c-index | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.76 | |||

Multivariable modeling with established variables for survival along with CD103/4 status demonstrates a significant survival benefit for CD103/4 mixed status and further greater survival for CD103/4 high status

Discussion

An immunologic statistical profile informed by CD103+ TIL content appears to be a valuable predictive marker for survival in recurrent LSCC after RT/CRT. This adds to our previous findings that an immune-rich tumor-infiltrating phenotype carries a better prognosis in head and neck cancers [8, 9]. Greater TIL content in tumor specimens, whether CD103+, CD4+ or CD8+, portends a better prognosis. CD103+ TILs, in particular, were highly correlated with a favorable prognosis in our cohort. Moreover, combined high CD103+ and CD4+ TIL status had the best prognosis, suggesting an interrelated role of unique adaptive immune cells in controlling tumor progression and metastasis. Conversely, patients with “immune depleted” tumors relatively devoid of CD103+ and CD4+ TILs had significantly worse observed outcomes. These findings support previous studies in suggesting that “immune depleted” tumor status may be a key prognostic factor in many malignancies [21–23].

In our cohort, CD103+ and CD8+ TIL content overlapped significantly, supporting the presence of a distinct subtype of activated, epithelial-localized, cytotoxic T-cells capable of malignant cell kill and tumor control. While a similar, albeit moderate, overlap of CD103 and CD8 expression was recently reported in TILs of non-small cell lung cancers [15], ours is the first study to confirm specialized TIL expression patterns in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck with translational implications. Further investigations into TIL expression patterns of CD4, CD8 and CD103 across a variety of head and neck cancers, both primary and recurrent, may lead to the discovery and functional characterization of further T-cell subpopulations vital to the adaptive immune response to malignancy.

Given our findings, it is quite likely that CD103+ TIL content may also prove to be a clinically useful biomarker for predicting response to induction chemotherapy, successful larynx preservation, and survival in primary laryngeal cancers treated with organ preservation protocols. To this aim, we are currently analyzing CD103+, CD8+ and CD4+ TIL content in our extensive repository of primary LSCC specimens treated with organ preservation protocols and hope to publish these data soon.

Of note, the pathogenesis of LSCC is not associated with human papillomavirus (HPV), and this is reflected in our LSCC cohort [5, 24]. Other HNSCC subsites, specifically oropharyngeal tumors, are more commonly associated with HPV, and these cancers are marked by a distinct immune phenotype with high levels of CD8+ T-cell infiltration and activation [25, 26]. HPV infection represents a favorable prognostic factor in HNSCC and it has been postulated that the associated immune response may play a role in this relationship. Thus, it is of great interest that an immune-rich tumor microenvironment was still associated with an improved prognosis in this cancer traditionally not associated with HPV and immune activation. Further studies investigating HPV + oropharyngeal cancers in the primary and salvage setting will be important in determining the importance of CD103 status and other immune markers in disease prognosis for these head and neck cancer subsites.

While “immune depleted” tumors carry a worse prognosis, it remains to be seen whether they may respond differently to immunotherapeutics. Given that the anti-PD-1 antibodies pembrolizumab and nivolumab are dependent on T-cell activity, there is theoretical concern that these “immune depleted” tumors may also be more resistant to immunotherapies, given their relative depletion of TILs [27, 28]. Nevertheless, there remains significant room for further characterization of TIL status and “immune depletion” status in head and neck cancers, both in vitro and in the clinic. This will be crucial to validate our initial findings and to generate algorithms with which to prognosticate patients and potentially stratify treatments.

The importance of immune signatures in cancer prognosis and the related response of immunotherapy in cancer treatment is becoming increasingly apparent. Thus, further elucidation of prognostic biomarkers will be a watershed in predicting patient outcomes, and potentially selecting patients who may benefit from adjuvant immunotherapy. Accordingly, as future genetic studies are completed, it is possible that molecular variables ranging from the status of genomic alterations to gene expression may further improve these immune signature-driven predictive models. The present study describes for the first time the value of the TIL marker CD103 in survival prognostication in head and neck cancer (specifically recurrent LSCC). Our findings suggest that CD103 status may be the most significant immune biomarker for disease prognostication and thus warrants further investigation in prospective studies and in consideration of treatment stratification paradigms.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (TIFF 22298 KB)

Abbreviations

- ACE-27

Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- CRT

Chemoradiation

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- DSS

Disease-specific survival

- FFPE

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- HNSCC

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- LSCC

Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- OS

Overall survival

- PD-1

Programmed cell death protein 1

- RT

Radiation

- TIL

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte(s)

- TMA

Tissue microarray

Author contributions

JEM and JDS designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. ACB and EB performed statistical analyses. PS, MM, SBC, AGS, KMM, KAC, SAM, JSM, GTW, CRB, MEP and TEC contributed to study design and sample procurement. JBM ensured quality of pathological specimens and tissue microarray. MES and JCB oversaw study design, execution, data analysis and manuscript drafts. All authors provided edits and approved of the final manuscript.

Funding

J. Chad Brenner received funding from NIH Grants U01-DE025184, P30-CA046592 and R01-CA194536. Thomas E. Carey received funding from NIH Grants U01-DE025184 and R01-CA194536. Jacqueline E. Mann was funded by NIH Grant F31-DE02760001. Joshua D. Smith received funding from NIH Grant T32-DC535615. J. Chad Brenner and Matthew E. Spector also received funding from the American Head and Neck Society.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this paper.

Ethical approval and ethical standards

This study was approved by the University of Michigan Hospital and Health Systems Institutional Review Board (HUM00081554).

Informed consent

The patients had provided informed consent to a prospectively maintained clinical epidemiology and tissue database.

Footnotes

Jacqueline E. Mann, Joshua D. Smith, Andrew C. Birkeland, Matthew E. Spector and J. Chad Brenner contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Matthew E. Spector, Phone: 734-936-3172, Email: mspector@umich.edu

J. Chad Brenner, Phone: 734-763-2761, Email: chadbren@umich.edu.

References

- 1.Forastiere AA, Zhang Q, Weber RS, Maor MH, Goepfert H, Pajak TF, et al. Long-term results of RTOG 91–11: a comparison of three nonsurgical treatment strategies to preserve the larynx in patients with locally advanced larynx cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:845–852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forastiere AA, Weber RS, Trotti A. Organ preservation for advanced larynx cancer: issues and outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3262–3268. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf GT, Fisher SG, Hong WK, Hillman R, Spaulding M, Laramore GE, et al. Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1685–1690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106133242402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Putten L, de Bree R, Kuik DJ, Rietveld DH, Buter J, Eerenstein SE, et al. Salvage laryngectomy: oncological and functional outcome. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birkeland AC, Beesley L, Bellile E, Rosko AJ, Hoesli R, Chinn SB, et al. Predictors of survival after total laryngectomy for recurrent/persistent laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2017;39:2512–2518. doi: 10.1002/hed.24918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris LG, Chandramohan R, West L, Zehir A, Chakravarty D, Pfister DG, et al. The molecular landscape of recurrent and metastatic head and neck cancers: insights from a precision oncology sequencing platform. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:244–255. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann JE, Hoesli R, Michmerhuizen NL, Devenport SN, Ludwig M, Vandenberg TR, et al. Surveilling the potential for precision medicine-driven PD-1/PD-L1-targeted therapy in HNSCC. J Cancer. 2017;8:332–344. doi: 10.7150/jca.17547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lei Y, Xie Y, Tan YS, Prince ME, Moyer JS, Nor J, et al. Telltale tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) in oral, head & neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2016;61:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoesli R, Birkeland AC, Rosko AJ, Issa M, Chow KL, Michmerhuizen NL, et al. Proportion of CD4 and CD8 tumor infiltrating lymphocytes predicts survival in persistent/recurrent laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2018;77:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf GT, Hudson JL, Peterson KA, Miller HL, McClatchey KN. Lymphocyte subpopulations infiltrating squamous carcinomas of the head and neck: correlations with extent of tumor and prognosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;95:142–152. doi: 10.1177/019459988609500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wansom D, Light E, Thomas D, Worden F, Prince M, Urba S, et al. Infiltrating lymphocytes and human papillomavirus-16 associated oropharynx cancer. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:121–127. doi: 10.1002/lary.22133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf GT, Chepeha DB, Bellile E, Nguyen A, Thomas D, McHugh J, The University of Michigan Head and Neck SPORE Program Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) and prognosis in oral cavity squamous carcinoma: a preliminary study. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen N, Bellile E, Thomas D, McHugh J, Rozek L, Virani S, et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and survival in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2016;38:1074–1084. doi: 10.1002/hed.24406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anz D, Mueller W, Golic M, Kunz WG, Rapp M, Koelzer VH, et al. CD103 is a hallmark of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2417–2426. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganesan A, Clarke J, Wood O, Garrido-Martin EM, Chee SJ, Mellows T, et al. Tissue-resident memory features are linked to the magnitude of cytotoxic T cell responses in human lung cancer. Nature Immunol. 2017;18:940–950. doi: 10.1038/ni.3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webb JR, Milne K, Watson P, deLeeuw RJ, Nelson BH. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes expressing the tissue resident memory marker CD103 are associated with increased survival in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:434–444. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webb JR, Milne K, Nelson BH. PD-1 and CD103 are widely coexpressed on prognostically favorable intraepithelial CD8 T cells in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:926–935. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Joint Committee on Cancer . AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th. Chicago: Springer Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keck MK, Zuo Z, Khattri A, Stricker TP, Brown CD, Imanguli M, et al. Integrative analysis of head and neck cancer identifies two biologically distinct HPV and three non-HPV subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:870–881. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandrekar JN, Mandrekar SJ, Cha SS (2003) Cutpoint determination methods in survival analysis using SAS. In: Proceedings of the 28th SAS users group international conference (SUGI) 261-28

- 21.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brambilla E, Le Teuff G, Marguet S, Lantuejoul S, Dunant A, et al. Prognostic effect of tumor lymphocytic infiltration in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1123–1130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang D, Liu Y, Wang H, Wang H, Song Q, Sujie A, et al. Tumour infiltrating lymphocytes correlate with improved survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44823. doi: 10.1038/srep44823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Gao L, Sturgis EM, Liang Z, Zhu Y, Xia X, et al. HPV16 DNA and integration in normal and malignant epithelium: implications for the etiology of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1105–1110. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Koneva LA, Virani S, Arthur AE, Virani A, Hall PB, et al. Subtypes of HPV-positive head and neck cancers are associated with HPV characteristics, copy number alterations, PIK3CA mutation, and pathway signatures. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:4735–4745. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon B, Young RJ, Bressel M, Urban D, Hendry S, Thai A, et al. Prognostic significance of PD-L1+ and CD8+ immune cells in HPV+ oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:295–304. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandal R, Senbabaoglu Y, Desrichard A, Havel JJ, Dalin MG, Riaz N, et al. The head and neck cancer immune landscape and its immunotherapeutic implications. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e89829. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moskovitz J, Moy J, Ferris RL. Immunotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2018;20:22. doi: 10.1007/s11912-018-0654-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 (TIFF 22298 KB)