Abstract

Introduction

Routine HIV viral load (VL) monitoring is recommended for patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) but frequent VL testing, required in pregnant and postpartum women, is often not feasible. Self-reported adherence can be valuable, but little is known about its longitudinal characteristics.

Methods

We followed women living with HIV from ART initiation in pregnancy through 18 months postpartum in Cape Town, South Africa, with repeated measurement of VL and self-reported adherence using a three-item scale. We used generalized estimating equations (with results presented as odds ratios [OR] with 95% confidence intervals [CI]) to investigate the association between viremia and change in adherence over pairs of consecutive visits.

Results

Among 2085 visit pairs from 433 women, a decrease in self-reported adherence relative to the previous visit on any of three self-report items, or the combined scale, was associated with VL >50 and >1000 copies/mL. The best performing thresholds to predict VL >50 copies/mL were a single level decrease on the Likert response item “how good a job did you do at taking your HIV medicines in the way that you were supposed to?” (OR 2.08 95% CI 1.48–2.91), and a decrease equivalent to ≥5 missed doses or a one level decrease in score on either of two Likert items (OR 1.34 95% CI 1.06–1.69).

Conclusion

Longitudinal changes in self-reported adherence can help identify patients with viremia. This approach warrants consideration in settings where frequent viral load monitoring or other objective adherence measures are not possible.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, self-reported adherence, viral load

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is the cornerstone of HIV treatment and prevention efforts. Current global guidelines recommend that all individuals living with HIV start lifelong ART as soon as they are diagnosed, thereby improving their long-term health outcomes [1]. HIV transmission during pregnancy, labor and delivery, and breastfeeding can be reduced to below 1% in the presence of suppressive ART [2]. However, optimal ART adherence is essential to achieve sustained viral suppression and to realize the treatment and prevention benefits.

Routine HIV viral load monitoring is being rolled out globally [3]. Viral load offers an objective marker of treatment success and a signal for poor adherence and antiretroviral resistance but, even with the push to scale up routine viral load monitoring, numerous challenges persist [3,4]. During pregnancy and postpartum, ART adherence is a particular concern due to the added risk of vertical HIV transmission [5,6]. An increased frequency of viral load testing is recommended during these periods, but this is not always feasible [7,8]. In low-resource settings where viral loads are infrequent or unavailable, other methods of assessing ART adherence are still required [9].

Self-reported adherence – which is inexpensive, immediate and easy to administer – is often used to assess ART adherence in both routine care and research settings. Although validated self-reported adherence measures exist, finding an optimal measure has been a focus of much research [10–13]. Self-reported adherence, which can often overestimate individual medication taking behavior, measures an individual’s perception of their treatment adherence [10]. It may be influenced by various biases such as social desirability or recall bias and this may vary between individuals depending on their own reference points regarding their medication-taking practices [11,14,15]. Despite these issues, self-reported adherence has often shown a reasonable correlation with viral load and other objective markers of adherence, including in low-resource settings [9,11,16].

Although there have been calls for longitudinal adherence measures to assess changes in ART adherence [17,18], the vast majority of studies have only evaluated the association between adherence and viral load at a single time point. Longitudinal measures provide an opportunity to examine relative changes in reported adherence which could help to account for individual reporting patterns. Predictors of changes in reported adherence have been explored but few studies have assessed whether changes in reported adherence are associated with an objective marker such as viral load [19–24]. Here we examined self-reported adherence and viral load among women living with HIV over multiple measurement points during and after pregnancy and investigate the association between changes in self-reported adherence and viremia.

Methods

We conducted a longitudinal analysis of women enrolled into a multi-phase implementation science study (the MCH-ART study, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01933477) which has been described previously [25]. Women were followed from ART initiation during pregnancy for up to18 months postpartum. Study visits occurred 2–3 times during pregnancy (depending on gestational age), once shortly after delivery and approximately every three months thereafter.

Setting

Women were recruited into the parent study between April 2013 and June 2014 when they presented for antenatal care at a large primary care antenatal and obstetric care clinic in Gugulethu, Cape Town, with follow-up through January 2016. This setting is characterized by high levels of poverty and unemployment, and a very high burden of HIV [26]. The local antenatal HIV prevalence was estimated to be 22% in 2015 [27] and all women starting ART received a fixed dose combination of efavirenz, tenofovir and emtricitabine [28].

Measures

Data were collected at study visits which occurred independently of routine HIV and antenatal care. Interviews were conducted by trained interviewers in the predominant local language, isiXhosa. Demographic characteristics including age, marital status, employment and timing of HIV diagnosis were collected at the time of enrolment. CD4 cell count and gestational age at presentation for antenatal care were abstracted from routine medical records.

Self-reported adherence was measured using a simple three-item adherence scale that was developed through a process of rigorous cognitive interviewing and has been validated in the United States [29–31]. It was translated into isiXhosa for use in South Africa and the cross-sectional validity of the translated individual scale items and the overall scale score were evaluated previously in this setting (Cronbach α=0.79) [32]. The three items in the scale (Table 1) include a quantification of missed doses as well as two Likert response scales that ask patients “how good a job did you do taking your medications in the way you were supposed to” and “how often did you take your medications in the way that you were supposed to,” all with reference to the past 30 days. To analyze the combined scale score, these three items were aggregated based on a re-coding of each item with equal weighting, to create a score ranging from 0 to 100, with the latter representing the best possible self-reported adherence.

Table 1.

Description of items in the three-item self-reported adherence scale and the thresholds used to assess change in adherence across visits.

| Item | Threshold |

|---|---|

|

1. In the last 30 days, on how many days did you miss at least one dose of any of your HIV medicines? X: Kwintsuku ezi-30 ezidlulileyo,zimini ezingaphi okhe walibala ukutya amchiza akho entsholongwana? Range 0–30 |

Stayed the same Increased by ≥1 missed dose Decreased by ≥1 missed dose |

|

2. In the last 30 days, how good a job did you do at taking your HIV medicines in the way that you were supposed to? X: Kwintsuku ezi-30 ezidlulileyo,zimini ezingaphi okhe walibala ukutya amchiza akho entsholongwana? Range “very poor” to “excellent” (1–6) |

Stayed the same Increased by ≥1 level Decreased by ≥1 level |

|

3. In the last 30 days how often did you take your HIV medicines in the way that you were supposed to? X: Kwezi ntsuku zi-30 zidlulileyo,kukangaphi usitya amachiza akho entsholongwane ngendlela omele kuwatya ngayo? Range “never” to “always” (1–6) |

Stayed the same Increased by ≥1 level Decreased by ≥1 level |

|

Combined three-item scale Range 0–100 |

Change ≤1 missed dose, both Likert items stayed the same Score increased ≥2 missed doses Score decreased ≥2 missed doses Change ≤4 missed doses, both Likert items stayed the same Increased by ≥1 level or ≥5 missed doses on any item Decreased by ≥1 level or ≥5 missed doses on any item Change ≤9 missed doses or 1 level change in either Likert item Increased by ≥2 levels or ≥10 missed doses on any item Decreased by ≥2 levels or ≥10 missed doses on any item |

E – English; X – isiXhosa

HIV RNA viral load, the “gold standard” in our analyses, was measured at each study visit on the same day as the self-reported adherence scale was administered. Separate from routine HIV care services, venous blood was collected and batch tested by the National Health Laboratory Services (Abbott RealTime HIV-1 assay, Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, USA), with results only available at the end of the study period.

Visits

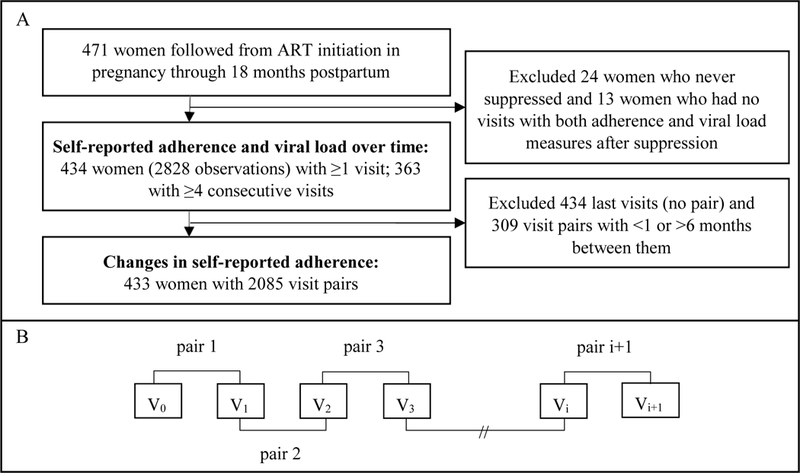

Women were included in analyses from their first suppressed viral load after ART initiation (V0). To minimize potential bias introduced by attrition from the study, we included only women who had at least four consecutive study visits after V0 in primary analyses of self-reported adherence and viral load over time (n=363). Data on trends over time for all women where at least one visit with both an adherence and a viral load measure was available after V0 are presented in supplementary material (n=434). We examined changes in self-reported adherence from each visit (Vi) to the next visit (Vi+1) among all available visit pairs from initial viral suppression (or from 16 weeks on ART in sensitivity analyses). Vi+1 was defined as the first visit occurring 1–6 months after Vi. Figure 1 summarizes A) the women and visits included in each analysis and B) the visit pair structure.

Figure 1.

A) Flow diagram of patient and visit inclusion and B) schematic of visit pairs where the first visit (V0) is the first suppressed visit after ART initiation in pregnancy.

Adherence and viral load thresholds

To describe the adherence scale score over time, thresholds of 100 versus <100 and ≥80 versus <80 were used. In prior work these cut-offs produced a reasonable balance between sensitivity and specificity [32]. To analyze changes in adherence score from Vi to Vi+1, we used a simple approach that could potentially be applied in routine care. We determined thresholds based on the minimum possible change in each self-reported adherence item. For item 1, reporting missed doses during the past 30 days, we examined a change of a single missed dose. For the other two items, 6-level Likert-type responses, a one-level change in response was examined. Larger changes in reported adherence were explored in sensitivity analyses, however there were very few visit pairs with larger changes and thus these data are not presented. For the combined scale score, we examined changes ranging from a single missed dose change in item 1 or a one level change in either of the Likert rating items, through to a change of ≥10 missed doses or ≥2 level change in either of the Likert rating items. All the change thresholds are outlined in Table 1. Viral load thresholds of >50 and >1000 copies/mL were examined based on the South African National ART guideline definitions of suppression and flags for treatment failure [33].

Analyses

Data were analyzed in Stata v14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). Means with standard deviation (SD) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) were used to describe continuous variables. Frequencies and proportions were used to describe categorical variables. Regression coefficients (as slopes) with standard error (SE) and chi-squared tests for trend were used to assess trends in reported adherence and viral load over time.

Generalized estimating equations (GEE) with robust SE and exchangeable correlation structures were used to explore the association between changes in reported adherence from Vi to Vi+1 and viral load at Vi+1 [13,34]. Quasi-likelihood under the independence model criterion (QIC), a modification of the Akaike information criterion (AIC), was used for model selection [35]. We included baseline self-reported adherence, viral load at Vi and time between Vi and Vi+1 in all models and examined additional baseline covariates (maternal age, marital status, education, employment, gravidity, gestational age at presentation for antenatal care, timing of diagnosis and CD4 cell count) that are often available in routine care and have previously been found to be associated with poor adherence or loss follow-up [36]. We then selected the final adjusted model based on the lowest QIC. Model results were reported as crude (OR) and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Primary analyses included all women who achieved viral suppression after ART initiation and who had at least one visit with both adherence and viral load data available following initial suppression (n=434; 92% of the total cohort of 471). Sensitivity analyses were conducted including an additional 17 women who did not achieve viral suppression but had adherence and viral load measurements after 16 weeks on ART. These results were very similar and are presented in supplementary material.

Ethics

All women included in this analysis provided written informed consent on enrolment into the parent study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board and the University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Among 471 women followed in the parent cohort, 37 women were excluded from analyses either because they were never observed to reach viral suppression (n=24) or they did not have at least one visit with adherence and viral load measured after achieving suppression (n=13). A total of 2828 visits were available from 434 included women (mean 4 visits per woman after initial viral suppression [range 1–9]). The median age was 28 years (IQR 25–33), 41% were married or cohabiting and 56% had been diagnosed with HIV in the incident pregnancy (Table 2). Only 18% were in their first pregnancy and median gestational age at presentation for antenatal care was 21 weeks (IQR 16–26). Adherence and viral load over time were examined among women who had at least four consecutive visits after initial suppression (n=363) to minimize the impact of attrition, as well as among all 434 women. Women excluded were younger, more likely to be in their first pregnancy, presented later for antenatal care and had slightly lower baseline CD4 cell counts compared to the women included (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of women at the time of presentation for antenatal care, presented as n (%) unless otherwise stated.

| Included, ≥4 consecutive visits after first viral suppression |

Excluded | Included, ≥1 visit after first viral suppression |

Excluded | All women in the parent cohort |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of women | 363 (77) | 108 (33) | 434 (92) | 37 (8) | 471 |

| Median age (IQR) | 28 (25–33) | 27 (23–31) | 28 (25–33) | 26 (23–30) | 28 (24–32) |

| Age ≤25 | 95 (26) | 42 (39) | 121 (28) | 16 (43) | 137 (29) |

| Married/cohabiting | 152 (42) | 41 (38) | 178 (41) | 15 (41) | 193 (41) |

| Completed secondary school | 87 (24) | 30 (28) | 104 (24) | 13 (35) | 117 (25) |

| Employed | 143 (39) | 41 (38) | 169 (39) | 15 (41) | 184 (39) |

| First pregnancy | 60 (17) | 27 (25) | 78 (18) | 9 (24) | 87 (18) |

| Diagnosed with HIV in this pregnancy | 199 (55) | 69 (64) | 245 (56) | 23 (62) | 268 (57) |

| Median CD4 (IQR) | 355 (254–544) | 327 (214–469) | 354 (251–534) | 284 (173–456) | 354 (248–517) |

| Median weeks gestation (IQR) | 20 (16–25) | 24 (19–30) | 21 (16–26) | 25 (21–31) | 21 (16–26) |

| Median adherence score at first visit on ART | 89 (78–94) | 89 (78–94) | 89 (78–94) | 93 (78–94) |

Self-reported adherence and viral load over time

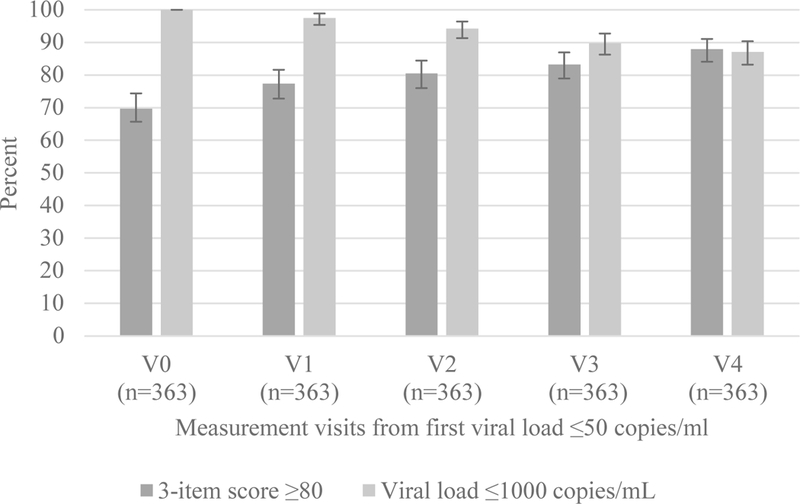

Among women with at least four visits after initial suppression (n=363), the proportion reporting adherence scores ≥80 increased slightly over time (slope 0.024, SE 0.004; chi-squared for trend p<0.001) while the proportion with viral loads ≤1000 copies/mL decreased (slope −0.028, SE 0.003; chi-squared for trend p<0.001) (Figure 2). These patterns were consistent when including all 434 women (S Figure 2) and in sensitivity analyses including women who did not suppress after ART initiation (S Figure 3). Although individual fluctuations in reported adherence were observed (S Figure 1), the median reported adherence remained stable over time (S Table 1).

Figure 2.

Proportion of women with adherence scores ≥80 and HIV viral loads ≤1000 copies/mL among 363 women with at least four study visits after V0 (first visit with a viral load ≤50 copies/mL after ART initiation during pregnancy). Data are shown from V0 through 4 additional visits (V1-V4).

Association between changes in self-reported adherence score and viral load

To analyze changes in reported adherence, 2085 visit pairs were available for 433 women (mean 3 visit pairs per woman [range 1–8]). The average time between Vi and Vi+1 was 2.4 months (SD 1.1). An adherence score ≥80 was reported at Vi in 81% and at Vi+1 in 83% of visit pairs. Viral load at Vi and Vi+1 was ≤50 copies/mL in 89% and 84% of visit pairs, and ≤1000 copies/mL in 93% and 89% of visit pairs, respectively. Overall, viral load remained below 50 copies/mL in most visit pairs. Viral load declined from >50 to ≤50 copies/mL in only 1% of visit pairs and increased from ≤50 to >50 copies/mL in 5% of pairs (S Table 2).

The results of univariable GEE models predicting viral load >50 and >1000 copies/mL at Vi+1, independent of the viral load measure at Vi, are presented in Table 3. Using the change thresholds outlined in Table 1 for a minimum change in each individual item and three different change thresholds on the combined scale score, a decrease in score was associated with viral load >50 and >1000 copies/mL. These results persisted in sensitivity analyses that included women who had never suppressed but who had at least 16 weeks on ART (S Table 3). In stratified analyses restricted to visit pairs where the viral load at the first visit of the pair (Vi) was ≤50 copies/mL (1852 visit pairs), the strength of association increased. However, when restricted to women who already had a raised viral load at Vi (126 visit pairs), a change in reported adherence was no longer predictive of having a raised viral load at Vi+1 (Table 3).

Table 3:

Univariable GEE models for change in each reported adherence from Vi to Vi+1 to predict viremia >50 and >1000 copies/mL at Vi+1 in all visit pairs and stratified by viral load ≤50 or >50 copies/mL at Vi. Results are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals; statistically significant associations are in bold.

| All visit pairs | Pairs with Vi viral load ≤50 copies/mL | Pairs with Vi viral load >50 copies/mL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of women | 433 | 428 | 126 | ||||

| Number of visit pairs | 2085 | 1852 | 233 | ||||

| Number of visit pairs, N (%) | To predict viral load >50 copies/mL | To predict viral load >1000 copies/mL | To predict viral load >50 copies/mL | To predict viral load >1000 copies/mL | To predict viral load >50 copies/mL | To predict viral load >1000 copies/mL | |

| Change in item 1 (missed dose) | |||||||

| No change in missed doses | 1621 (78) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Increased ≥1 missed dose | 223 (11) | 0.95 (0.65–1.40) | 0.97 (0.62–1.23) | 0.96 (0.54–1.71) | 1.37 (0.71–2.65) | 1.28 (0.51–3.21) | 0.85 (0.41–1.76) |

| Decreased ≥1 missed dose | 241 (12) | 1.45 (1.07–1.97) | 1.41 (1.04–1.93) | 1.72 (1.11–2.66) | 1.54 (0.84–2.81) | 1.87 (0.71–4.92) | 1.64 (0.87–3.07) |

| Change in item 2 (good job) | |||||||

| No change | 1824 (87) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Increased ≥1 level | 139 (7) | 1.07 (0.70–1.64) | 0.93 (0.55–1.58) | 0.98 (0.49–1.94) | 0.72 (0.26–1.97) | 2.36 (0.53–10.52) | 1.83 (0.88–3.78) |

| Decreased ≥1 level | 122 (6) | 2.08 (1.48–2.91) | 1.89 (1.33–2.68) | 2.30 (1.32–3.99) | 2.09 (1.03–4.25) | 5.57 (0.80–38.64) | 1.85 (0.67–3.93) |

| Change in item 3 (how often) | |||||||

| No change | 1600 (77) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Increased ≥1 level | 240 (12) | 0.98 (0.72–1.33) | 0.76 (0.51–1.34) | 1.23 (0.75–2.00) | 1.09 (0.55–2.16) | 0.83 (0.33–2.12) | 0.61 (0.30–1.23) |

| Decreased ≥1 level | 245 (12) | 1.34 (0.98–1.83) | 1.10 (0.79–1.54) | 1.72 (1.09–2.71) | 1.73 (0.97–3.09) | 1.73 (0.63–4.75) | 0.82 (0.43–1.57) |

| Change in combined score | |||||||

| No change in missed doses | 565 (27) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Increased ≥1 missed dose | 784 (38) | 1.00 (0.78–1.27) | 0.96 (0.73–1.25) | 1.08 (0.70–0.66) | 1.05 (0.58–1.89) | 1.04 (0.45–2.40) | 0.94 (0.51–1.76) |

| Decreased ≥1 missed dose | 736 (35) | 1.23 (0.98–1.54) | 1.22 (0.96–1.55) | 1.53 (1.01–2.31) | 1.72 (0.99–2.97) | 1.00 (0.43–2.32) | 1.03 (0.57–1.87) |

| Change ≤4 missed doses | 1209 (58) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Increased ≥1 levels or ≥5 missed doses | 447 (21) | 1.02 (0.78–1.34) | 0.95 (0.69–1.30) | 1.19 (0.78–1.81) | 1.23 (0.42–2.12) | 1.21 (0.54–2.72) | 1.08 (0.60–1.93) |

| Decreased ≥1 levels or ≥5 missed doses | 429 (21) | 1.34 (1.06–1.69) | 1.32 (1.05–1.68) | 1.69 (1.16–2.47) | 1.71 (1.05–2.78) | 1.19 (0.55–2.57) | 1.37 (0.79–2.36) |

| Change ≤9 missed doses or 1 level | 1321 (63) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Increased ≥2 levels or ≥10 missed doses | 387 (19) | 0.94 (0.72–1.24) | 0.87 (0.63–1.21) | 1.19 (0.78–1.82) | 1.24 (0.71–2.16) | 1.28 (0.53–3.11) | 1.09 (0.61–1.92) |

| Decreased ≥2 levels or ≥10 missed doses | 377 (18) | 1.29 (1.02–1.63) | 1.28 (0.99–1.65) | 1.65 (1.11–2.45) | 1.76 (1.07–2.90) | 1.25 (0.56–2.77) | 1.22 (0.66–2.24) |

Multivariable models were examined for the two thresholds with the strongest associations: Item 2 “How good a job did you do at taking your HIV medicines in the way that you were supposed to?”, and the combined three-item scale threshold of a change of one level on either of the Likert items or ≥5 missed doses. A single level decrease in reported adherence on item 2 remained predictive of having a viral load >50 and >1000 copies/mL (aOR 2.62 95% CI 1.57–4.30 and aOR 1.91 95% CI 1.15–3.17, respectively) in adjusted models (S Table 4). Similarly, a decrease in self-reported adherence score equivalent to ≥5 missed doses or a one level decrease in score on either item 2 or 3 also remained predictive of viral load >50 and >1000 copies/mL (aOR 1.62 95% CI 1.11–2.38 and aOR 1.42 95% CI 1.00–2.03, respectively). Again, these results were consistent in sensitivity analyses (S Table 5). In all analyses, there was no association between an improvement in reported adherence and odds of viral suppression at Vi+1. Increasing age, being married/cohabiting and being employed all independently reduced the odds of having a raised viral load, while increasing months on ART, presenting later for antenatal care, having a viral load >50 or >1000 copies/mL at Vi, and increasing time between Vi and Vi+1, increased the odds of having a viral load >50 and >1000 copies/mL at Vi+1 (S Table 4; univariable associations presented in S Table 6).

Discussion

In this cohort of women living with HIV who were followed from ART initiation during pregnancy through 18 months postpartum, decreases in self-reported adherence relative to the previous visit were independently predictive of raised viral load. Self-reported adherence remained high over repeated follow-up visits and, despite decreases in the proportion of women with viral suppression over time, over 80% of women attending each visit were virally suppressed.

With a rapidly growing population on ART, routine viral load monitoring is recommended at least annually with increased frequency during pregnancy and breastfeeding, but not all settings are able to implement such frequent viral load testing [3,8]. Assessing change in reported adherence may provide an interim assessment to flag patients requiring additional intervention between viral load measures. The association between reporting decreased adherence and having a raised viral load in our cohort was most marked when restricted to visits where the viral load at the previous visit was suppressed. When participants had an unsuppressed viral load at the first visit of the pair, a decline in reported adherence did not predict viremia. However, in this adherent cohort there were relatively few such cases, which reduced statistical power to detect these differences. In routine practice this may be less of a concern as women with any raised viral loads should already be flagged for further intervention. One possible application may be to measure change in reported adherence following a suppressed viral load as an interim screening tool to prompt adherence counselling or viral load testing only among women reporting worse adherence. Further exploration of the utility and application of this approach is warranted in routine care settings where resources limit the frequency of viral load testing or other objective adherence measures.

Self-reported adherence measures, although subject to well-documented biases, present the patient’s perception of their own adherence behavior, e.g. some patients may miss a few doses and report excellent adherence while others may miss the same number of doses and report very poor adherence. Assessing a change in reported adherence in an individual over two consecutive visits could be a straightforward way for providers to flag emerging adherence problems, relative to each patient’s individual reporting. We found that, on average, women with viremia >50 or >1000 copies/mL, had increased odds of reporting worsening adherence across two visits on one or more of the three adherence scale items. These findings persisted after adjusting for duration between visits, viral load at the previous visit, and other covariates. Previous studies have used similar methods to assess the predictors of changes in reported adherence, but few have linked this change to a biological or objective adherence marker [21,22,24]. The three individual scale items examined independently did not all perform equally. The second item, a Likert rating scale of how good a job you did taking your medication in the last 30 days, had the highest point estimates (OR 2.08 95% CI 1.48–2.91 to detect viral load >50 copies/mL). An additional benefit of this change in adherence approach is that no adherence score conversions would be required. A provider could, for example, plot a patient’s response to each of the three questions at each visit. A patient reporting a poorer score on any or a combination of the questions could be flagged for further evaluation and appropriate interventions. Whether longitudinal changes in adherence could be assessed in this way, or even using a single item, merits testing in other populations and in routine care settings.

Although a strength of this study is the very well-characterized cohort contributing over 2800 visits, it is important to note that there was attrition over time. Women excluded from these analyses were younger, more likely to be in their first pregnancy, presented later for antenatal care and had lower CD4 cell counts compared to the overall cohort. These characteristics are all potential risk factors for loss to follow-up and poor ART adherence [36]. In pregnant and postpartum women, younger age in particular has been consistently found to predict loss to follow-up and poor adherence [36,37]. By including only the available data, selection bias was introduced and women at higher risk of poor adherence or viremia are likely to have been excluded. While this is a limitation, it is equivalent to the selection bias that would be present in the monitoring of ART services in routine care settings. This emphasizes the importance of comprehensive efforts to retain all people living with HIV in ART services.

The longitudinal relationships between changes in self-reported adherence and viral load will likely vary depending on the distribution of reported adherence and viral load levels in the population being examined, the population sampled (e.g. pregnant and postpartum women), and other contextual factors. Here we studied pregnant and postpartum women from a single site in Cape Town, South Africa. This is likely representative of other urban sites in South Africa and sub-Saharan Africa but generalizability to other settings and populations should be considered with caution. All adherence and viral load measures were taken as part of research study visits, independent of routine HIV care, which may have reduced socially desirable response bias. Language and context translation are complex issues that may have impacted these results. The self-report scale was translated into isiXhosa directly from the questions designed and validated in the United States and translation could partly explain the differences observed between the individual adherence items. Results may be strengthened by exploring cognitive interviewing approaches in the local language. We studied a population with excellent adherence and high rates of viral suppression for whom, in most cases, adherence could only decrease. It would be important to repeat this analysis in less adherent populations for whom adherence could both increase and decrease. Lastly, we were unable to assess the association between changes in self-reported adherence and an objective adherence marker, such as electronic drug monitoring or drug-level monitoring, which may be better “gold standard” measures of adherence behaviors than viral load.

Conclusion

In this cohort of South African women who initiated ART during pregnancy as part of routine care, self-reporting worse adherence relative to the previous visit on any of three simple adherence questions, and specifically the Likert item asking how good a job you did taking your medications in the way you were supposed to, was consistently associated with viremia. These results show that changes in self-reported adherence could provide a simple flag for women at risk for raised viral loads. This approach warrants further consideration in the context of monitoring ART adherence in settings with limited access to viral load and objective adherence monitoring.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the women who participated in this study, as well as the study staff for their support of this research.

sources of funding:

This research was supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), grant number 1R01HD074558. Additional funding comes from the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation. Dr. Wilson is partially supported by the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research (P30AI042853) and by Institutional Development Award Number U54GM115677 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, which funds Advance Clinical and Translational Research (Advance-CTR) from the Rhode Island IDeA-CTR award (U54GM115677). Dr Orrell is partially supported through DAIDS grants (1R01AI122300 – 01, 1R34MH108393–01 and 2UM1AI0695–08). Drs. Mellins and Remien are partially supported by NIMH Center Grant (P30-MH43520).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

For the remaining authors none were declared.

Meetings where data has been presented: N/A

References

- 1.The INSIGHT START Study Group. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sturt A, Dokubo E, Sint T. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) for treating HIV infection in ART-eligible pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lecher S, Ellenberger D, Kim AA, et al. Scale-up of HIV Viral Load Monitoring — Seven Sub-Saharan African Countries. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015. November 27;64(46):1287–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts T, Cohn J, Bonner K, et al. Scale-up of Routine Viral Load Testing in Resource-Poor Settings: Current and Future Implementation Challenges. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(8):1043–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnack A, Rempis E, Decker S. Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV in Option B + Era : Uptake and Adherence During Pregnancy. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(3):110–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas AD, Msukwa MT, Egger M, et al. Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy during and after Pregnancy: Cohort Study on Women Receiving Care in Malawi’s Option B+ Program. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(9):1227–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Psaros C, Remmert JE, Bangsberg DR, et al. Adherence to HIV Care After Pregnancy Among Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: Falling Off the Cliff of the Treatment Cascade. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesosky M, Glass T, Mukonda E, et al. Optimal timing of viral load monitoring during pregnancy to predict viraemia at delivery in HIV-infected women initiating ART in South Africa: A simulation study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20:26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mekuria LA, Prins JM, Yalew AW, et al. Which adherence measure – self-report, clinician recorded or pharmacy refill – is best able to predict detectable viral load in a public ART programme without routine plasma viral load monitoring? Trop Med Int Heal. 2016;21(7):856–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garfield S, Clifford S, Eliasson L, et al. Suitability of measures of self-reported medication adherence for routine clinical use: A systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stirratt MJ, Dunbar-Jacob J, Crane HM, et al. Self-report measures of medication adherence behavior: recommendations on optimal use. Transl Behav Med. 2015;5(4):470–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson IB, Carter AE, Berg KM. Improving the self-report of HIV antiretroviral medication adherence: Is the glass half full or half empty? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2009;6(4):177–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simoni JM, Huh D, Wang Y, et al. The Validity of Self-Reported Medication Adherence as an Outcome in Clinical Trials of Adherence-Promotion Interventions: Findings from the MACH14 Study. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(12):2285–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austin EJ, Deary IJ, Gibson GJ, et al. Individual response spread in self-report scales: Personality correlations and consequences. Pers Individ Dif. 1998;24(3):421–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson MO, Neilands TB. Neuroticism, Side Effects, and Health Perceptions Among HIV-Infected Individuals on Antiretroviral Medications. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2007;14(1):69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nieuwkerk PT, Oort FJ. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection and virologic treatment response: a meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(4):445–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voils CI, Hoyle RH, Thorpe CT, et al. Improving the measurement of self-reported medication nonadherence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(3):250–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook PF, Schmiege SJ, Starr W, et al. Prospective State and Trait Predictors of Daily Medication Adherence Behavior in HIV. Nurs Res. 2017;66(4):275–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker BW, Thames AD, Woo E, et al. Longitudinal change in cognitive function and medication adherence in HIV-infected adults. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1888–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu H, Miller LG, Hays RD, et al. Repeated measures longitudinal analyses of HIV virologic response as a function of percent adherence, dose timing, genotypic sensitivity, and other factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(3):315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glass TR, Battegay M, Cavassini M, et al. Longitudinal Analysis of Patterns and Predictors of Changes in Self-Reported Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy: Swiss HIV Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;54(2):197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleeberger CA, Buechner J, Palella F, et al. Changes in adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy medications in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. AIDS. 2004;18(4):683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okawa S, Chirwa M, Ishikawa N, et al. Longitudinal adherence to antiretroviral drugs for preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Zambia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazo M, Gange SJ, Wilson TE, et al. Patterns and Predictors of Changes in Adherence to Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy: Longitudinal Study of Men and Women. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(10):1377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myer L, Phillips TK, Zerbe A, et al. Optimizing Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) for Maternal and Child Health (MCH): Rationale and Design of the MCH-ART Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(Suppl 2):S189–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.City of Cape Town – 2011 Census Suburb Gugulethu. Cape Town, South Africa; 2013.

- 27.South African National Department of Health. The 2015 National Antenatal Sentinal HIV & Syphilis Survey Report. Pretoria, South Africa: National Department of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myer L, Phillips T, Manuelli V, et al. Evolution of antiretroviral therapy services for HIV-infected pregnant women in Cape Town, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(2):e57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson IB, Lee Y, Michaud J, et al. Validation of a New Three-Item Self-Report Measure for Medication Adherence. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(11):2700–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fowler FJ, Lloyd SJ, Cosenza CA, et al. Coding Cognitive Interviews: An Approach to Enhancing the Value of Cognitive Testing for Survey Question Evaluation. Field Methods. 2014;28(1):3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson IB, Fowler FJ, Cosenza CA, et al. Cognitive and Field Testing of a New Set of Medication Adherence Self-Report Items for HIV Care. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:2349–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips T, Brittain K, Mellins CA, et al. A Self-Reported Adherence Measure to Screen for Elevated HIV Viral Load in Pregnant and Postpartum Women on Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(2):450–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.South African National Department of Health. National consolidated guidelines for the Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the managment of HIV in children, adolescents and adults. Pretoria, South Africa; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huh D, Flaherty BP, Simoni JM. Optimizing the analysis of adherence interventions using logistic generalized estimating equations. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):422–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui J QIC program and model selection in GEE analyses. Stata J. 2007;7(2):209–20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodgson I, Plummer ML, Konopka SN, et al. A systematic review of individual and contextual factors affecting ART initiation, adherence, and retention for HIV-Infected pregnant and postpartum women. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gourlay A, Birdthistle I, Mburu G, et al. Barriers and facilitating factors to the uptake of antiretroviral drugs for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.