Abstract

Because little is known about the mental health status of Syrian refugees in the United States, we conducted a survey among a convenience sample of those resettled in Atlanta between March 2011 and 2017. Though home visits, we delivered a questionnaire including standardized instruments (HSCL25 and PTSD-8) to assess symptoms of anxiety, depression and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. We found high rates of anxiety (60%), depression (44%) and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (84%) symptoms; however, only 20% of participants had seen a mental health professional. Reported reasons for not seeking professional help were lack of transportation and access to information. Findings of this survey indicate the high burden of mental health symptoms and the need for services to the study population. A longitudinal study with a larger sample size would improve the understanding of mental health needs and resilience factors of Syrian refugees resettled in the US.

Keywords: Mental health, Refugees, Depression, PTSD, Anxiety, Psychological distress, Syria, Global health security

Background

The war in Syria has generated the largest exodus of refugees since World War II [1] and has displaced over eleven million people [1]. Resettlement is the “key to safety” for many refugees escaping war and persecution [2]. Over 20,000 of these refugees have come to the United States between October 2011 and March 2017 [3]; 628 have come to the State of Georgia. After being exposed to multiple traumatic events, adjusting to a country of resettlement may pose its own challenges. Traumatic events during the conflict, in addition to years of stressors during displacement in refugee camps or in urban areas, as well as those experienced after resettlement, may contribute to severe mental illness among Syrian refugees [4]. These mental disorders can be a worsening of existing conditions, new symptoms as a result of violence and displacement, and/or problems adjusting to post-emergency contexts like refugee camps and host countries [4].

As is the case for many victims of war and displacement, the most common and clinically significant mental illnesses among Syrian refugees are emotional disorders [5]. Emotional disorders include depression, prolonged grief disorder, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and various anxiety disorders [4].

Other studies among Syrian refugees residing in refugee camps in Beirut, Lebanon [6] described elevated levels of anxiety and depression and among Syrian refugees in Turkey [7], elevated prevalence of PTSD.

Psychological trauma, as a result of the conflict, has increased the demand for psychological support among Syrian refugees [8]. An increase of the number of Syrians with severe mental health disorders has been found by Lebanese psychiatric hospitals [5]. Similarly, over half (54%) of the Syrians assessed in four countries (Lebanon, Syria, Turkey and Jordan), had severe psychological disorders—including depression and anxiety [4]. Improving refugees’ mental health and psychosocial well-being has been identified as a priority by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) [9]. However, the quality of services is often inadequate given limited response capacity and a shortage of trained mental health professionals in emergency contexts [10].

Even after resettlement, refugees are still vulnerable to the development of mental illnesses. Several studies have shown the importance of risk and resilience factors among refugees, as well as post-migration stressors. A study of Bhutanese refugees resettled in the United States found high rates of depression (21%), anxiety symptoms (19%), PTSD (4.5%) and suicidal ideation (3%) [11]. Among the same population, family separation and worrying about the family left behind was strongly linked to suicide [12]. Lack of social support is one of the most important mental health risk factors among refugees, as is ongoing war in the country of origin [4]. In a meta-analysis of 59 studies, among refugees and a non-refugee comparison group, the authors describe the role of contextual factors before and after displacement as moderators of mental health. The presence of economic opportunities and access to work as well as the maintenance of a socioeconomic status are protective factors [13].

Another study describes in a theoretical resource-based model the post-migration adaptation and psychological well-being among refugees. Access to a variety of resources is particularly relevant to the post-migration phase.

In a review of 29 studies [14] assessing mental disorders of long-settled war-refugees worldwide, a total of 16,010 war-affected refugees, the findings indicate (1) generally high prevalence rates of depression, PTSD and other anxiety disorders among refugees 5 years or longer after displacement, with prevalence estimates typically in the range of 20% and above.

In a systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence rates of PTSD and depression in the refugee and post conflict mental health field, the authors found significant between-study heterogeneity in prevalence rates of depression (range 2.3–80%), PTSD (4.4–86%), and unspecified anxiety disorder (20.3–88%), although prevalence estimates were typically in the range of 20% and above [15].

Based on these findings, we would expect a high burden of mental illness among Syrian refugees even after resettlement in the United States. Adjusted policy changes can therefore lessen the impact of psychological traumas and other risk factors on refugees. Yet, without data on the mental health status among resettled Syrian refugees in the United States, it is difficult to adequately adjust public polices to aid current and future resettled refugees. The purpose of this study was to assess the mental status of the resettled Syrian refugee population and available mental health care services in Metropolitan Atlanta.

Methods

Participants

Our sampling frame consisted of the database of “Georgians for Syria”, a community organization supporting Syrian refugees in Atlanta. Syrian refugees aged 18 years old and older who resettled between March 2011 and March 2017 in Metropolitan Atlanta were eligible for inclusion. Among the list of 40, a total of 25 Syrian refugees were included in the sample. Among the 15 who were not enrolled, three refused to be part of the study and 12 did not answer to our call (response rate of 62.5%).

Procedure

The investigator called all the 25 Syrian refugees by phone in Arabic. He explained to them the aim of the study and the interview sequence. He emphasizes on the anonymous nature and on the non-obligation to answer to all the questions asked. In two cases, the investigator was helped by a respected community member to gain acceptance and be able to conduct the interview.

Data Collection

Our survey instruments consisted of 90 items, many taken directly from existing validated survey instruments. The questionnaire included closed and partially closed ended questions.

The survey included a socio-demographic component and a mental health services assessment developed by the study team. In order to assess post migration stressors and mental health condition symptoms (PTSD, depression and anxiety), standardized instruments were used.

These instruments included: the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 25 (HSCL 25); the traumatic events list, PTSD-8, and the post migration trauma events scale [16–19]. All the instruments used in this study (HSCL 25, PTSD 8 and HTQ) have previously been validated in Arabic [20, 21]. The investigator visited participants in their homes to administer the survey to each adult household member. He read the questions in Arabic to each participant separately and filled the questionnaire sheets. On average each questionnaire took 24 min excluding the introduction.

Analysis Plan

We used the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 25 (HSCL 25) to assess symptoms of anxiety, depression and psychological distress on a four-point scale of severity. The HSCL-25 is a set of 25 questions designed to assess symptoms of anxiety and depression and includes ten anxiety symptom questions and 15 depression symptoms questions. We considered an average score of 1.75 or higher out of 4 as positive for anxiety and depression symptoms, respectively [17]. The psychological distress score is calculated based on the average of the anxiety and depression scores. We considered a person as positive for psychological distress when the mean score was 1.75 or higher out of 4.

We assessed pre-migration traumatic experiences using a traumatic events list of 15 items, derived from the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) [17, 22]. Participants were asked to say if they encountered certain events since the beginning of the war in Syria.

To assess the presence of PTSD, four intrusive, two avoidance and two hypervigilance items on the PTSD-8 were used. Participants were asked to respond using a four-point scale where four was a feeling that occurred “all the time.” We considered each set of items (intrusion, avoidance and hypervigilance) positive if at least one item was scored three or higher. The calculated score gave a score for PTSD symptom severity [18]. This test showed good psychometric properties in three independent samples [18].

A 14-item checklist was adapted from the post-migration living difficulties checklist used with Bhutanese refugees [19]. The study team chose the items relevant to the Syrian context. The checklist assessed the causes of stress faced by Syrian refugees resettled in Atlanta. The participants were asked to scale the stressors on a four-point scale: ‘not at all’ (1), ‘a little’ (2), ‘quite a bit’ (3), and ‘extremely’ (4).

To assess mental health services, we designed five original questions. These questions assessed preexisting mental health conditions and treatments, the need for mental health support since resettlement, and the availability and quality of the mental health services offered to refugees.

Microsoft Excel was used for the data entry and the data analysis (Microsoft Excel version 15.13.1). Due to the small sample size, a simple descriptive analysis was conducted. We report demographic characteristics in frequencies and percentages for the total with a stratification by gender. We report medians and ranges for continuous variables. We were unable to perform multivariable analyses or show associations between traumatic events, demographic characteristics and mental health illnesses as a result of the small sample size.

IRB Statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Approval number IRB00087212).

Results

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 25 participants between June 2016 and March 2017 in Metropolitan Atlanta. The majority of the participants were males (75%). Nearly all (92%) were married with a median of 3.8 children per family (range 1–8) (Table 1). The majority came from three main Syrian governorates: Dar’aa (40%), Damascus (24%) and Aleppo (20%). The median of age of the participants was 37.5 (range 20–55; SD 9.4). Both genders were similar in terms of mean ages (males: 37.6 and females: 37.3). Nearly half (40%) were between 30 and 40 years of age, while 20% were under age 30. Three participants (12%) had no education. Twenty-four per cent went only to primary school, 36% went to secondary school and 28% were college educated. A third (32%) were able to both read and write English. Three (12%) participants presented a physical disability.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Syrian refugees in Metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, 2016 (N = 25)

| Variable | Male n (col%) (n = 15) | Female n (col%) (n = 10) | Total N = 25 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Median | 37.6 | 37.3 | 37.5 |

| Range | 21–55 | 20–54 | 20–55 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 15 (100%) | 8 (80%) | 23 (92%) |

| Single | 0 | 1 (10%) | 1 (4%) |

| Widowed | 0 | 1 (10%) | 1 (4%) |

| Education | |||

| None | 2 (13.4%) | 1 (20%) | 3 (12%) |

| Primary | 4 (26.6%) | 2 (20%) | 6 (24%) |

| Secondary | 6 (40%) | 3 (30%) | 9 (36%) |

| University | 3 (20%) | 4 (40%) | 7 (28%) |

| English literacy | |||

| Yes | 4 (26.7%) | 4 (40%) | 8 (32%) |

| No | 11 (73.3%) | 6 (60%) | 17 (68%) |

| Employed | |||

| Yes | 9 (60%) | 3 (30%) | 12 (48%) |

| No | 6 (40%) | 7 (70%) | 13 (52%) |

Participants reported a median of 3.7 forced migrations inside and outside of Syria. Most (84%) fled Syria in 2012, while 8% fled in 2011 and 12% in 2013. After leaving Syria, 60% stayed in refugee camps; nearly half (48%) of these participants fled to Jordan. The average time spent in refugee camps was 8.6 months (range 0.25–60 months). While many participants reported spending time in camps, 84% of the population ended up at some point of their displacement in a non-camp setting. The average time spent in non-camp settings was 43 months (range 24–60 months). The migration procedure to the US took more than 2 years for 13.5% of the participants, between 1 and 2 years for 73%, and between 6 and 12 months for 13.5% of them. Median time in the US following resettlement was 11 months (range 6–15 months) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Migration history of Syrian refugees in Metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, 2016 (N = 25)

| Variable | Total N (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of forced migrations inside Syria | |

| Median | 4.27 |

| Range | 1–20 |

| Been in refugee camps | |

| Yes | 15 (60%) |

| No | 10 (40%) |

| Length of time in camps (in months) | |

| Median | 8.6 |

| Range | 0.25–60 |

| Stayed in non camp settings | |

| Yes | 21 (84%) |

| No | 4 (16%) |

| Length of time in non-camp settings (in months) | |

| Median | 40.5 |

| Range | 24–60 |

| Length of the US migration procedure | |

| 6–12 months | 6 (24%) |

| 1–2 years | 11 (44%) |

| More than 2 years | 8 (32%) |

| Length of stay in the U.S. (in months) | |

| Median | 11 |

| Range | 6–15 |

Nearly all (96%) of participants experienced at least one traumatic event prior to resettlement. Within the range of traumatic events, the five most commonly reported were: lack of food or water (72%), murder or death of a family member (68%), exposure to a combat situation (64%), forced separation from family members (64%) and lack of shelter (60%) (Table 3). No one reported having been a victim of rape or sexual abuse or having had a life-threatening accident.

Table 3.

Traumatic events before resettlement

| Traumatic event | Number of participants N (%) |

|---|---|

| Suffered from a lack of food or clean water | 18 (72) |

| Murder or violent death of a family member | 17 (68) |

| Exposed to a combat situation | 16 (64) |

| Forced separation from family members | 16 (64) |

| Lacked shelter | 15 (60) |

| Oppressed because of ethnicity, religion or sect | 14 (56) |

| Serious physical injury of family member or friend from combat situation or landmine | 14 (56) |

| Ill health without access to medical care | 11 (44) |

| Threatened with a weapon | 9 (36) |

| Witnessed murder | 7 (28) |

| Tortured | 6 (24) |

| Being abducted | 2 (8) |

| Serious physical injury from a combat situation | 1 (4) |

| Rape or sexual abuse | 0 (0) |

| A life-threatening accident | 0 (0) |

The most common post-migration difficulty reported was the language barrier (88%) followed by worries about family members in Syria (84%) (Table 4). Inability to pay living expenses was also a significant concern expressed by 60% of the surveyed population, while a lack of help from charity organizations was reported by 56% of participants. Discrimination and difficulties maintaining cultural and religious traditions were not reported nor was the lack of religious community.

Table 4.

Top 5 post-migrations concerns among Syrian refugees in Metropolitan Atlanta, 2016

| Post migration traumatic event | Total reporting trauma event as severe to very severe (%) |

|---|---|

| Language barrier | 22 (88) |

| Worries about family back at home | 21 (84) |

| Inability to pay living expenses | 15 (60) |

| Little help from charities or other agencies | 14 (56) |

| Poor access to counseling services | 14 (56) |

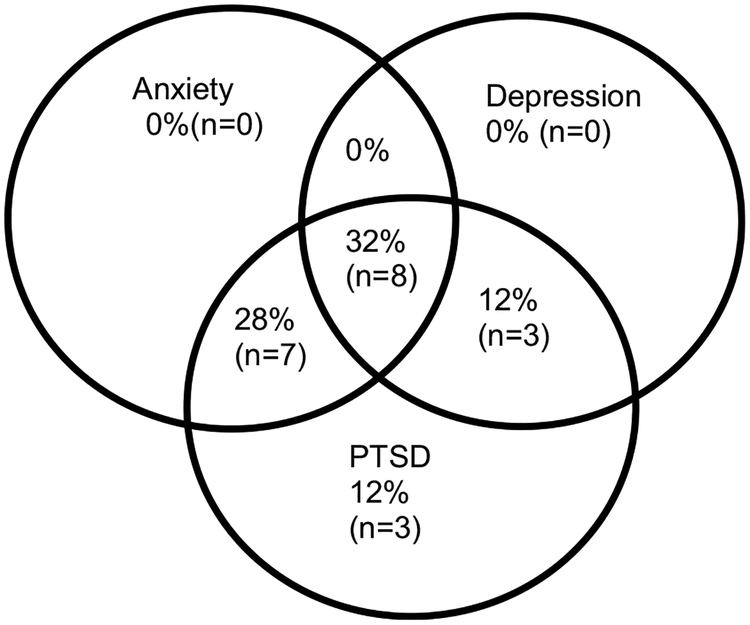

Using the HSCL 25 and 1.75 cut-off point, 60% of the participants reported anxiety symptoms, 44% depression symptoms and 60% psychological distress (Table 5). Using the PTSD-8, 21 participants experienced at least one item from each of the PTSD symptom clusters. This means that 84% of the study group presented symptoms of PTSD. Only four participants had a negative score for the three PTSD items. These findings show overlaps between depression, anxiety and PTSD (Fig. 1). Eight (32%) participants exhibited symptoms of all three conditions. Of the participants, 75% (18) had an overlap of at least two conditions. Depression and anxiety symptoms did not occur in isolation.

Table 5.

Mental health symptoms among Syrian refugees in Metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, 2016 (N = 25)

| Condition | n (%) |

|---|---|

| History of diagnosed mental health condition | 3 (12) |

| Anxietya | 15 (60) |

| Depressiona | 11 (44) |

| Psychological distressa | 15 (60) |

| PTSD | |

| Intrusion | 17 (68) |

| Avoidance | 16 (64) |

| Hypervigilance | 15 (60) |

| Overall PTSD diagnosis (case definition)b | 21 (84) |

In order to assess symptoms of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress, we used the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSC). We considered positive for the anxiety and depression symptoms, respectively an average score of 1.75 or higher out of 4. The psychological distress score is the average of the anxiety and depression. We considered a person to be positive for psychological distress when the score is of 1.75 or higher out of 4

A possible PTSD diagnosis would be considered if at least one item from each of the PTSD symptom clusters (Intrusion, Avoidance, hypervigilance) is positive (an item score of 3 or above is considered positive)

Fig. 1.

Overlapping symptoms of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in Syrian refugees (n = 25)

Only seven participants (28%) reported having felt the need to talk with a health provider about psychological discomfort. Only five actually went to see a mental health professional. Of those who saw a health professional, most (60%) thought the visit to be very helpful. For the two participants who felt the need to see a health provider but did not go, a lack of information and access to transportation were the two main reasons reported.

Discussion

In our study, we found high rates of anxiety (60%), depression (44%) and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (84%) symptoms; however, only 20% of participants had seen a mental health professional. Among our sample of resettled Syrian refugees, rates of depression symptomatology (44%) were consistent with previous studies. Previous studies have shown depression prevalence at around 44% [23, 24].

A systematic review of research done between 1980 and 2009 showed a global prevalence for anxiety disorders of 7.3% [25]. This rate is higher among refugee populations. In fact, a meta-analysis including 24,051 refugees (regardless of the country of origin) found a combined prevalence rate for anxiety of 40% [23]. Another study conducted among a mixed urban-refugee population in Beirut found anxiety disorders to be the second most frequent primary diagnoses (after depression) with a rate of 15.6% [6]. In the present study, anxiety symptoms were reported among 60% of our sample.

The occurrence of PTSD symptoms reported in our study was 84%. PTSD signs occurred more frequently than was found among other surveys of Syrian refugees. In Turkey, a cross sectional survey reported 33.5% of the Syrian refugees with PTSD symptoms [7]. In this study the highest prevalence of PTSD was 71% among refugees “with the following characteristics: females diagnosed with a history of a psychological disorders, having a family history of psychiatric disorder and experiencing two or more traumatic events” [7]. Almost three quarters (72%) of the refugees surveyed reported suffering from a lack of food or clean water, and 68% had a family member or a friend murdered during the war.

Only 20% of participants went to see a mental health professional despite reports of high levels of symptoms of mental illness which highlights the gap between the need for mental health services and their use [12].

The social stigma of a diagnosed mental illness is deeply ingrained in the Syrian culture. Such stigma may deter help seeking behavior [4]. The provision of mental health services in non-medical settings may help reduce this stigma. Integrating psychosocial programs in community centers can help reduce stigma and increase access [4]. Study participants mentioned that the main reasons for not seeking professional help were a lack of information and access to transportation. Availability, accessibility, and perceived efficacy of mental services highly influence the use of such services [12]. This may indicate a lack of awareness from the resettlement agencies and health institutions.

Lutheran Services of Georgia and International Rescue Committee, two of the main resettlement agencies in Georgia, already screen for mental disorders as part of the Refugee Health Screening (RHS-15) [26]. However, this screening is not systematic and lacks active counselling and follow-up. More culturally and linguistically appropriate services are critical to ease refugees’ access to and increase the use of mental health support [4]. All the refugees interviewed lived in a housing complex with limited access to public transportation. Better access to public transportation would improve accessibility and use of the mental health services by refugees.

Several limitations should be noted. Our data describe a specific group of Syrian refugees in Metropolitan Atlanta and cannot be generalized to the overall Syrian refugee populations in the US or to other refugee populations. The results are limited by a modest convenience sample of 25 participants. It was difficult to gather data from a group where mental health illnesses are still strongly socially stigmatized. Five individuals directly refused participation. Having the survey delivered by a native Arabic speaker who grew up in a similar culture helped reduce these difficulties to some extent.

Because the PTSD-8 is not commonly used in refugee studies, it was more difficult to make direct comparisons with the PTSD results of other refugee studies.

To our knowledge this is the first study of the mental health needs of Syrian refugees resettled in the United States. In spite of the study limitations, our data highlight the high burden of mental health illnesses symptoms among Syrian refugees as well as the critical need for better access and more culturally acceptable mental health services for this vulnerable population.

In order to gain a better understanding of the mental health needs and resilience factors of Syrian refugees resettled in the US, we recommend conducting a longitudinal study with a larger sample size. The preliminary results of this survey indicate that mental health services are needed for Syrian refugees in the United States.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere appreciation to the Syrian refugee community for their hospitality and trust. We are grateful to Mary Helen O’Connor for her review of the manuscript prior to submission.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.UNHCR. Global Trends: forced displacement in 2015 [Internet]. 2015. http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/statistics/unhcrstats/576408cd7/unhcr-global-trends-2016.html.

- 2.UNHCR. Resettlement [Internet]. http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/resettlement.html.

- 3.Refugee Processing Center, the U.S department of State, bureau of population, refugees and migration. Syrian Refugees resettled in the United States, FY 2012–17: admissions and arrivals database. Refugee Processing Center; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassan G, Ventevogel P, Jefee-Bahloul H, Barkil-Oteo A, Kir-mayer LJ. Mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of Syrians affected by armed conflict. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25:129–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNHCR. Culture, context and the mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of Syrians a review for mental health and psychosocial support staff working with syrians affected by armed conflict 2015 [Internet]. 2015. http://www.unhcr.org/55f6b90f9.pdf.

- 6.Bastin P, Bastard M, Rossel L, Melgar P, Jones A, Antierens A. Description and Predictive Factors of Individual Outcomes in a Refugee Camp Based Mental Health Intervention (Beirut, Lebanon). PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alpak G, Unal A, Bulbul F, Sagaltici E, Bez Y, Altindag A, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder among Syrian refugees in Turkey: a cross-sectional study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2015;19:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IMC. SYRIA CRISIS addressing regional mental health needs and gaps in the context of the Syria crisis [Internet]. 2014. http://internationalmedicalcorps.org/document.doc?id=526.

- 9.Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Geneva: IASC; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissbecker I, Leichner A: Addressing mental health needs among Syrian refugees. Washington, DC: Middle East Inst.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ao T, Shetty S, Sivilli T, Blanton C, Ellis H, Geltman PL, et al. Suicidal ideation and mental health of Bhutanese refugees in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18:828–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagaman AK, Sivilli TI, Ao T, Blanton C, Ellis H, Lopes Cardozo B, et al. An investigation into suicides among Bhutanese refugees resettled in the United States between 2008 and 2011. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18:819–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porter M, Haslam N. Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2005;294:602–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bogic M, Njoku A, Priebe S: Long-term mental health of war-refugees: a systematic literature review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights [Internet]. 2015. http://bmcinthealthhumrights.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Steel Z, Chey T, Silove D, Marnane C, Bryant RA, van Ommeren M. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009;302:537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parloff MB, Kelman HC, Frank JD. Comfort, effectiveness, and self-awareness as criteria of improvement in psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1954;111:343–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mollica R: The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire. Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180(2):111–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen M, Andersen TE, Armour C, Elklit A, Palic S, Mackril T. PTSD-8: a short PTSD inventory. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2010;1:101–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellis BH, Lankau EW, Ao T, Benson MA, Miller AB, Shetty S, et al. Understanding Bhutanese refugee suicide through the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2015;85:43–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnetz BB, Broadbridge CL, Jamil H, Lumley MA, Pole N, Barkho E, et al. Specific trauma subtypes improve the predictive validity of the Harvard trauma questionnaire in Iraqi refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16:1055–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vonnahme LA, Lankau EW, Ao T, Shetty S, Cardozo BL. Factors associated with symptoms of depression among Bhutanese refugees in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17:1705–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleijn WC, Hovens JE, Rodenburg JJ. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in refugees: assessments with the Harvard trauma questionnaire and the hopkins symptoms checklist- 25 in different languages. Psychol Rep. 2001;88:527–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindert J, von Ehrenstein OS, Priebe S, Mielck A, Brähler E. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:246–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naja WJ, Aoun MP, El Khoury EL, Abdallah FJB, Haddad RS. Prevalence of depression in Syrian refugees and the influence of religiosity. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;68:78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol Med. 2013;43:897–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollifield M, Verbillis-Kolp S, Farmer B, Toolson EC, Woldehaimanot T, Yamazaki J, et al. The Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15): development and validation of an instrument for anxiety, depression, and PTSD in refugees. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:202–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]