Abstract

Objective:

To determine contraception use among a cohort of reproductive-age women (18–50 years) with rheumatic diseases.

Methods:

We conducted a study of administrative data from a single, large medical center between years 2013 and 2014. Women who had 1 of 21 rheumatic disease diagnoses and had at least 2 outpatient rheumatology visits were included in this analysis. We used logistic regression analyses to evaluate adjusted associations between the use of prescription contraception, use of potentially fetotoxic medications, and visits with rheumatologists, primary care providers (PCP), and gynecologists.

Results:

Of 2455 women in this sample, 32.1% used any prescription contraception, and 7.9% of women used highly effective prescription methods (intrauterine devices, implants, and surgical sterilization). Over 70% of women used at least one fetotoxic medication during the two-year study timeframe. Fetotoxic medication use was not associated with overall use of prescription contraception, but was associated with the use of highly effective contraceptive methods (aOR 2.26, 95%CI: 1.44–3.54). Women who saw gynecologists or PCPs were more likely to use prescription contraception overall (aOR 3.35, 95%CI: 2.77–4.05 and aOR 1.43, 95%CI: 1.18–1.73, respectively). Women who saw gynecologists were more likely to use highly versus moderately effective contraceptive methods (aOR 2.35, 1.41–3.94). Rheumatology visits were not associated with use of prescription contraception in any models.

Conclusions:

This is the largest study to describe contraceptive usage among reproductive-age women with rheumatic diseases, and reveals low usage of prescription contraception. Urgent efforts are needed to improve contraceptive care and access, for some women with rheumatic diseases.

Introduction

While over two-thirds of reproductive-age women in the United States actively use contraception (1), little is known about contraceptive use among young women with rheumatic diseases. In addition to preventing unintended pregnancy, contraception may uniquely benefit these women by delaying pregnancy until their diseases are quiescent. Indeed, fewer perinatal disease flares, higher neonatal birth weights, more live births, and fewer complications such as preeclampsia, may occur among women with inactive versus active diseases at time of conception; such benefits have been reported for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), ankylosing spondylitis, systemic sclerosis, vasculitis, and the inflammatory myopathies (2–9). As several medications used by women with rheumatic diseases have substantial teratogenic potential, contraception use may also prevent pregnancy until women and their doctors have established an acceptably safe medication regimen.

Despite the benefits of pregnancy planning and contraceptive care for women with rheumatic diseases, several prior surveys of young women with SLE, APS, RA, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) indicated that a minority of women received contraceptive counseling, used any contraception, and rarely used highly-effective methods (e.g., subdermal implants, intrauterine devices (IUD)) (10–12); reasons for this are unclear, and findings from these surveys have rarely been substantiated. Also unclear is the prevalence of contraception use among women with rarer rheumatic diseases.

This study uses administrative data to describe the prevalence and predictors of contraception use among reproductive-age women with a variety of rheumatic diseases. We hypothesized that teratogenic medication use and engagement with medical providers (e.g., primary care providers (PCPs), gynecologists, and rheumatologists) would be associated with greater use of prescription contraception overall and with highly effective as compared to less effective prescription contraceptive methods.

Patients and Methods:

Study Population and Data Sources

This retrospective cohort study utilized administrative data from a large, multi-site health care system in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Approximately 28,000 unique patients visit this system’s rheumatology outpatient clinics annually, of which 75% are cared for in community practices. Females aged 18–50 years constitute 26% of all patients, and 93% of these women have either private or public insurance.

In the current study, electronic health record data were accessed for female patients aged 18–50 years who had received care on at least two occasions at any one of twelve outpatient rheumatology clinics between years 2013 and 2014. We required women to have had at least two rheumatology visits in order to capture women who received longitudinal care for their rheumatic diseases within this single health care system.

Study criteria also required a patient diagnosis of at least one of twenty-one rheumatic diseases identified by International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) codes: SLE, Sjogren’s Syndrome, RA, APS/antiphospholipid antibodies, undifferentiated connective tissue disease, psoriatic arthritis, spondyloarthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic sclerosis, dermatomyositis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, polymyositis, Bechet’s, sarcoidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, Takaysu arteritis, reactive arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis (Appendix A).

Women were excluded from this analysis if they had any evidence of a hysterectomy in the preceding 10 years, as this procedure is generally not indicated for contraceptive purposes (n=97).

Study Variables

Our key independent variables of interest were medications by pregnancy risk category, and visits with PCPs, gynecologists, and rheumatologists. We used the former FDA classification system of medication risk in pregnancy established in the 1970s to assess the teratogenic potential of drugs used by this cohort of women. In 2014, the FDA developed a new system to classify drug safety (13), but because this classification scheme is descriptive, personalized, and is still in the process of implementation, we elected to use the former FDA classification scheme. In addition, the former FDA classification scheme was used during our study timeframe.

All non-contraceptive medications prescribed to patients between 2013 and 2014, and including but not limited to anti-rheumatic drugs, were identified and assigned a FDA Pregnancy Risk Category using a commercial indexing database (Thomson Micromedex 2017). When no pregnancy class was presented in the indexing database, we consulted another reference guide to confirm the classification (14). FDA Class A and B medications are generally considered safe to use during pregnancy, Class C medications have not been adequately studied to assign a pregnancy classification, and Class D and X drugs are potentially teratogenic and are relatively or absolutely contraindicated for use during pregnancy. A single medication may be assigned more than one FDA Class based on the trimester of pregnancy (e.g., non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs); our classification was based on the highest fetal risk attributed to the drug. For women who were prescribed multiple drugs with different FDA Pregnancy Risk classifications, we also assigned their FDA risk category based on their drug with the greatest potential teratogenicity. We did not classify drugs without an FDA Pregnancy Risk designation. Our analysis categorizes drugs as either A/B/C or D/X, (“low risk” versus “high risk”) (Appendix E), although by definition, Class C medications could be associated with fetal risk that is yet undescribed.

Outpatient visits with primary care providers (PCPs), obstetrician-gynecologists, and rheumatologists were identified in patients’ records. Study criteria required patients to have had at least two outpatient rheumatology visits, but patients could have any number of outpatient visits with other providers over the two-year study period. To identify women who had more than minimal engagement with rheumatologists over the study timeframe, we categorized women who had two rheumatology visits separately from women who had greater than two visits. We categorized the number of patients’ visits to PCPs or gynecologists over the study timeframe as no visits versus one or more visits.

This analysis had two main outcomes of interest. We first looked at prescription contraception use versus non-use. Among women with documented prescription contraception use, we next considered highly effective versus moderately effective contraception use.

We defined prescription contraception as female surgical sterilization (e.g., tubal ligation), IUD, subdermal implant, oral contraceptive pill (including the progestin-only pill), patch, vaginal ring, or injectable. Prescription contraception medications or devices prescribed in years 2013 and 2014 were identified in patients’ medication lists. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and ICD-9 codes were used to identify IUD or subdermal implant insertion or removal procedures, or surgical sterilization procedures that occurred within the prior 10 years.

Contraceptive methods were also classified by relative efficacy based generally on World Health Organization (WHO) categories (15): 1) IUDs, implants, and surgical sterilization were highly effective methods, 2) hormonal methods were moderately effective (i.e., oral contraceptive pills (OCP), patches, vaginal rings, and shots); and 3) methods that are rarely prescribed and generally are less effective at preventing pregnancy than are prescription methods were least effective methods (i.e., condoms, sponges, diaphragms, emergency contraception, and spermicide) (Appendix B). Least effective methods were rarely documented in this cohort, so the few women who had any documentation of these methods were combined with women who had no documentation of a contraceptive method into a single category labeled “no documented prescription method.”

When women had more than one contraceptive method listed in their chart, we categorized them by their most effective method as this would have the greatest influence on their risk of unintended pregnancy. We identified contraceptive counseling in the medical records through billing codes.

Data Analysis

We described patient demographic variables, provider visits, the four most common rheumatic diagnoses, FDA medication risk categories of medications, outpatient visits with providers, and prescription contraception methods in Table 1. We also presented study variables based on the presence or absence of documented prescription contraception (Table 2). We used Chi-square tests to assess comparisons between groups for each of the categorical variables.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (n=2455)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 18-34 | 696 (28.4) |

| 35-50 | 1759 (71.6) |

| Race | |

| White | 2007 (81.8) |

| Black | 276 (11.2) |

| Asian | 144 (5.9) |

| Other | 28 (1.1) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 908 (37.0) |

| Married | 1291 (52.6) |

| Other | 256 (10.4) |

| Rheumatic Diseases | |

| SLE | 510 (20.8) |

| Sjogren’s | 487 (19.8) |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 615 (25.1) |

| Antiphospholipid antibodies/syndrome |

103 (4.2) |

| FDA Medication Risk Category | |

| Class A/B/C | 687 (28.0) |

| Class D/X | 1761 (71.7) |

| Outpatient Clinic Visits | |

| Rheumatology Visits (median, range) | 3 (2-30) |

| PCP Visit ≥1 | 980 (39.9) |

| Gynecology Visit ≥1 | 790 (32.2) |

| Prescription Contraception Methods | |

| Any Prescription Method | 787 (32.1) |

| Highly Effective Method | 194 (7.9) |

| Moderately Effective Method | 593 (24.2) |

| LARC | 139 (5.7) |

| No Method/Least Effective Method | 1668 (67.9) |

Prescription Contraception Methods are defined in Appendix B. SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics by Presence or Absence of Documented Prescription Contraception (n=2455)

|

Prescription Contraception N=787 (32%) |

No Documented Prescription Contraception N=1668 (68%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 18-34 | 347 (44.1) | 349 (20.9) | <0.001 |

| 35-50 | 440 (55.9) | 1319 (79.1) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 659 (83.7) | 1348 (80.8) | 0.002 |

| Black | 95 (12.1) | 181 (10.9) | |

| Asian | 4 (0.5) | 24 (1.4) | |

| Other | 29 (3.7) | 115 (6.9) | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 270 (47.0) | 921 (55.2) | <0.001 |

| Married | 361 (45.9) | 547 (32.8) | |

| Other | 56 (7.1) | 200 (12.0) | |

| Rheumatic Diseases | |||

| SLE | 155 (19.7) | 355 (21.3) | 0.37 |

| Sjogren’s | 158 (20.1) | 329 (19.7) | 0.84 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 179 (22.7) | 436 (26.1) | 0.07 |

| Antiphospholipid antibodies/syndrome | 35 (4.4) | 68 (4.1) | 0.67 |

Differences between groups were assessed using X2 tests for categorical variables. Rheumatic diseases were assessed separately, as presence versus absence of each disease. SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus. Variables are presented as N (%).

We conducted logistic regression analyses to evaluate the associations between the key independent variables (D/X versus A/B/C medication risk and provider engagement) with our outcomes, use of: 1) prescription contraception versus non-use in the entire sample, and 2) highly effective versus moderately effective contraception among prescription contraception users. We used bivariable models to evaluate associations between the key predictor variables and both outcomes. We also created adjusted models for each contraceptive outcome that included the key independent variables in addition to age, race, and marital status, as these variables may affect a woman’s choice to use contraception or a particular contraceptive method (16).

Furthermore, while surgical sterilization is only performed by gynecologists, subdermal implants can be inserted by any provider who receives the appropriate training (17), and IUDs are routinely inserted by PCPs in addition to gynecologists. For this reason, we were particularly interested in use of LARC methods in this population (i.e., implants and IUDs). In a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the logistic regression analysis that evaluated associations between the prescription of highly effective versus moderately effective contraception, but focused on LARC methods by excluding surgical sterilization from the highly effective contraception group.

Finally, while our analysis generally uses the FDA pregnancy risk categories, azathioprine, which was categorized as a FDA Class D medication, is widely considered to be compatible with pregnancy. Azathioprine is routinely prescribed to pregnant women with rheumatic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, the vasculitides, and the inflammatory myopathies, and use of azathioprine has been advocated in various consensus guidelines (18, 19). We therefore conducted two sensitivity analyses in which we re-categorized azathioprine as a Class A/B/C (i.e., low-risk) drug, and also omitted it from the analyses altogether; we then repeated the logistic regression analyses described above.

P values were two-sided and significant at the level of <0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS. This study was designated as exempt by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for the sample of 2455 women are presented in Table 1. Most women were married and White, with mean age of 39.4 (S.D. 7.7). Overall, 71.7% of women in this cohort used at least one medication with teratogenic potential over the study timeframe. Women had a median of 3 rheumatology visits (range: 2 – 30) over the 2 years of the study. We found that 60.1% of women had no documented primary care visits, 67.8% had no gynecology visits, and 45% of patients had neither primary care nor gynecology visits documented over the study timeframe. RA (25.1%), SLE (20.8%), Sjogren’s syndrome (19.8%), and Undifferentiated Connective Tissue Disease (13.2%) were among the most common rheumatic diagnoses, and 4.2% of women had antiphospholipid antibodies or syndrome (APS) (Appendix C). Methotrexate (26.1%), tumor necrosis alpha inhibitors (23.3%), and hydroxychloroquine (49.3%) were among the most common traditional and biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs prescribed in the sample; azathioprine was prescribed to fewer women (6.76%). Prednisone and/or methylprednisolone were prescribed to 58.0% of the sample (Appendix D).

Contraceptive Use

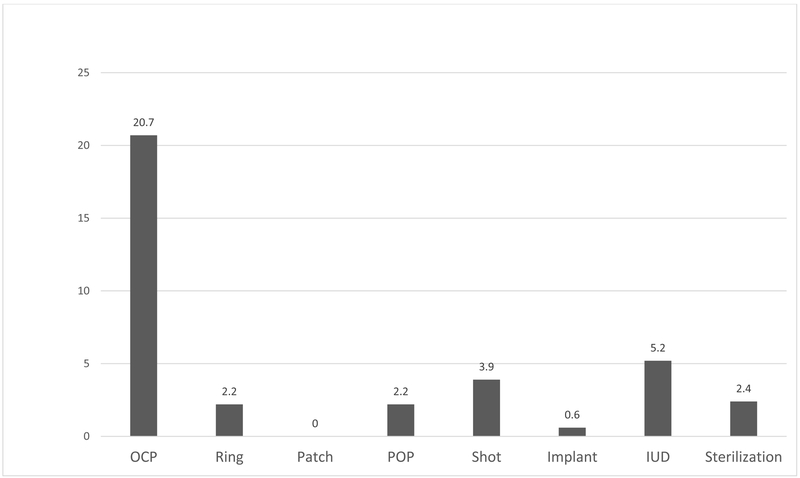

In our cohort, 32.1% of women used prescription contraception. Young and single women were more likely to use prescription contraception than were older women or women who were either married or not single (Table 2). Most women used moderately effective contraceptive methods (Table 1), and OCPs were the most commonly prescribed method type (Figure 1). Billing codes for contraception counseling were used for 4.5% of women in the sample.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Prescription Contraceptive Methods Used in Cohort, by Percentage (%) (n=2455)

Abbreviations defined as follows: OCP= oral contraceptive pill, Ring= vaginal ring, Patch= transdermal patch, POP= progestin-only pill, Shot = Depomedroxyprogesterone acetate, Implant = subdermal implant, IUD = intrauterine device, Sterilization = tubal ligation or Essure procedure.

Potential Unmet Need for Prescription Contraception

The prescription of FDA Class D/X medications was also not associated with use versus non-use of prescription contraception. However, women who saw gynecologists (aOR 3.35, 95%CI: 2.77–4.05) and PCPs (aOR 1.43 95%CI: 1.18–1.73) were more likely to use prescription contraception than were women who did not see these providers in unadjusted and fully adjusted models (Table 3). In contrast, women who had more than 2 rheumatology visits were no more likely to use prescription contraception than were women who had fewer visits in fully adjusted models.

Table 3.

Predictors of Any Documented Prescription Contraception versus No Documented Contraception (n=2455)

|

Unadjusted OR (95%CI) p value |

Adjusted OR (95%CI) p value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA Medication Risk Category | ||||

| Class D/X | 1.04 (0.86-1.26) | 0.68 | 1.04 (0.84-1.29) | 0.69 |

| Class A/B/C | REF | REF | ||

| Outpatient Clinic Visits | ||||

| Rheumatology Visits ˃ 2 Visits = 2 |

1.22 (1.01-1.47) REF |

0.036 | 1.22 (1.0-1.50) REF |

0.06 |

| PCP Visit ≥1 Visits <1 |

1.75 (1.48-2.08) REF |

<0.0001 | 1.43 (1.18-1.73) REF |

<0.0001 |

| Gynecology Visit ≥1 Visits <1 |

3.53 (2.95-4.23) REF |

<0.0001 | 3.35 (2.77-4.05) REF |

<0.0001 |

Table 3 includes unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios. Reference category for all models is No Documented Contraception. Adjusted models include all covariates in addition to age, race, and marital status.

Among prescription contraception users (n=787), potentially fetotoxic medication use and care by gynecologists or PCPs were each associated with use of highly effective versus moderately effective methods in adjusted models (Table 4). Women who used potentially teratogenic medications were more likely to use highly effective methods as compared to moderately effective methods (aOR 2.26, 95%CI: 1.44–3.54). Women with at least one gynecology visit were also significantly more likely to use highly effective contraceptive methods (aOR 1.51, 95%CI: 1.07–2.14). Women with at least one PCP visit were no more likely to use highly effective contraceptive methods than were women who did not see a PCP. Having more than two documented rheumatology visits was not associated with the prescription of highly effective methods. In sensitivity analysis excluding women with surgical sterilization (n=55), we found that the associations between our key predictors of interest and contraceptive efficacy did not change. Specifically, we found that potentially fetotoxic medications and gynecologic care were associated with use of LARC methods, and rheumatology visits were not associated with LARC prescription in any models.

Table 4.

Predictors of Highly Effective Contraception versus Moderately Effective Contraception (n=787)

|

Unadjusted OR (95%CI) p value |

Adjusted OR (95%CI) p value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA Medication Risk Category | |||||

| Class D/X | 2.40 (1.57-3.65) | <0.0001 | 2.26 (1.44-3.54) | <0.0001 | |

| Class A/B/C | REF | REF | |||

| Outpatient Clinic Visits | |||||

| Rheumatology Visits ˃2 Visits = 2 |

1.02 (0.71-1.45) | 0.94 | 0.80 (0.54-1.17) | 0.25 | |

| PCP Visit ≥1 Visits <1 |

1.54 (1.11-2.13) | 0.01 | 1.31 (0.92-1.86) | 0.13 | |

| Gynecology Visit ≥1 Visits <1 |

1.56 (1.13-2.17) | 0.0008 | 1.51 (1.07-2.14) | 0.02 | |

Table 4 includes unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios. Reference category for all models is Moderately Effective Contraception. Adjusted models include all covariates in addition to age, race, and marital status.

In a sensitivity analysis in which we re-categorized azathioprine as a Category A/B/C medication (i.e., lower-risk), thirty-three women were reclassified from the D/X to the A/B/C category. This change in classification did not change our results: 1) prescription of Class D/X medications remained unassociated with prescription of any contraception (aOR: 1.08 [0.87–1.33]), and 2) Class D/X medications remained significantly associated with highly effective contraception prescription (aOR 2.33 [1.49–3.62]). In the sensitivity analysis in which we omitted azathioprine entirely, results were similar: Class D/X medications were not associated with prescription of any contraception (aOR: 1.08 [0.88–1.33]), but remained associated with prescription of highly effective contraception (aOR 2.32 [1.49–3.61]).

Discussion

This analysis used administrative data from a large multi-site health care system to describe contraception use among reproductive-age women with diverse rheumatic diseases. We found that 32.1% of these women used prescription contraception. Use of potentially teratogenic medication was not associated with greater usage of prescription contraception; notably, over two-thirds of women in this sample used at least one medication with teratogenic potential. Teratogenic medication use was associated with the prescription of highly effective methods, including LARC methods, among those women who used prescription contraception. While gynecology and PCP visits were associated with prescription contraception use, and gynecology visits were associated with use of highly effective methods, most women had no documentation of a PCP or gynecology visit over the 2-year study interval.

An estimated 43.1% of reproductive-age women in the general U.S. population used at least one prescription contraception method during our study timeframe of 2013–2014 (1). Given disease-specific considerations, patients’ exceptionally common use of fetotoxic medications, and their regular engagement with rheumatologists and perhaps other health providers, we had expected that the contraceptive usage rate among our cohort would have exceeded that of the general population. It is unclear how many of these women received contraception counseling; while some health care providers may have administered family planning conversations for which they did not submit a billing code, only 4.5% of women in our cohort had billing codes for family planning conversations (20). Therefore, our overall findings reveal a potentially urgent and unmet need for contraception and family planning counseling among some reproductive-age women with rheumatic diseases.

Few studies have examined contraceptive use among women with rheumatic diseases, but our findings are generally consistent with prior results. One study of insurance plan data found that only 20% of female enrollees with RA and SLE (n=93) had filled prescriptions for any contraceptive method during the 3-year study timeframe (21). A survey of young women with SLE found that only 24% used prescription contraceptive methods—and of note, 23% had unprotected sex most of the time (11). Another survey of women with SLE reported that only 33% of patients used hormonal contraceptive methods or IUDs (10); consistent with our own findings, fetotoxic medication use did not predict the use of contraception.

Gynecologists and PCPs appear to have an important role in the prescription of contraception overall, and of highly effective methods in particular. However, we found that the majority of women in this cohort had no documentation of PCP or gynecology visits during the study timeframe. This finding will require further investigation, as we may not have captured out-of-network PCPs and gynecologists. However, regional patterns in insurance coverage in addition to limited health care competition in western Pennsylvania, lead many patients to receive health care from in-network providers. Therefore, while our results might underestimate to some degree the level of care that our cohort received from PCPs and gynecologists, it is still likely that many of these women did not receive regular care from these providers. Recent work has found that some rheumatic disease patients perceive their rheumatologists to be their “main doctors,” and are less inclined to seek routine care from other providers (22). Furthermore, as pelvic exam, cervical and breast exam screening recommendations have changed over the last few years, fewer annual women’s health visits with PCPs or gynecologists are required for many young women (23–25).

Rheumatologists may be able to fill important and unique gaps in family planning counseling and care for women with rheumatic diseases. For example, some rheumatologists may be able to advise other providers about contraceptive safety for women with rheumatic diseases. We noted that among the 35 women with antiphospholipid antibodies or APS who used prescription contraception in our cohort, the majority (n=23, 65.7%) used estrogen-containing methods; estrogen-containing contraception is considered to pose an unacceptable thrombotic risk for these patients as per the CDC Medical Eligibility Criteria and other consensus guidelines (26, 27). In addition, while most women with rheumatoid arthritis have no disease-related contraindications to hormonal contraception, only 29% of women with RA in this sample used prescription contraception. Many RA patients are exposed to methotrexate, a fetotoxic anti-rheumatic drug that is widely recommended as a first-line treatment; therefore, some women in our sample may have been at risk of unintended pregnancy while taking a fetotoxic medication (28, 29). Rheumatologists may be more aware of these and other disease-specific considerations than are other providers. Through referrals to gynecologists and PCPs, rheumatologists may also help patients to gain access to quality family planning care; this may be particularly important as our findings suggest infrequent utilization of gynecology and PCP care. Educational resources and tools are available to provide support and guidance to all providers who wish to provide more comprehensive family planning care to their patients, and who want more guidance about safe medication prescribing among women with rheumatic diseases (30–38).

Our study has several strengths. First, it is the largest study to date that describes contraceptive usage among women with rheumatic diseases, and includes women with rare, understudied diseases. Additionally, we used administrative data, which may have circumvented some biases that are associated with survey-based methods (e.g., selection, recall and response biases). Our findings may also reflect general practice patterns, as three-quarters of women received care in community-based rheumatology practices. The great majority of patients were insured (over 90%), so many patients likely had access to longitudinal rheumatologic care, medications, and contraception; in fact, we would expect that many insured patients had at least some access to low- or no-cost contraception given that the Affordable Care Act of 2010 required insurance plans to cover the costs of birth control.

Our study does have limitations. First, although our results were comparable to those reported in other studies and our sample primarily received care in community-based clinics, generalizability may be somewhat limited as all rheumatologic care occurred within a single medical center in North America. Results may vary in poorer states that offer less access to contraception care, or in countries that have a higher prevalence of contraception use due to policies that facilitate access to low- or no-cost contraception (39). Our sample was predominately White and older; young and minority women may less likely to use prescription contraception (40), so contraception utilization could be even lower in a more diverse population. Our methodology also did not capture other factors that may influence contraception use or choice of method, such as a woman’s personal preferences, pregnancy intentions, current heterosexual activity, fertility, health insurance status, current family size, or socioeconomic status.

In addition, incomplete documentation could not be ascertained via our methodology. For example, a sterilization procedure performed in an outside hospital or prescription contraception provided by a third party (e.g., Planned Parenthood) may have been missed. We also could not accurately capture non-prescription contraceptive methods (e.g., behavioral methods), nor could we confirm patient compliance with any prescribed contraceptive method. These factors could overestimate or underestimate the risk of unintended pregnancy of this group, respectively. However, medication lists and procedures should be updated in the EHR with each outpatient visit, so documentation of contraception methods and potentially teratrogenic drugs should ideally have been indicative of current use.

We also could not determine how long a patient used any specific medication, which would affect the degree of risk of fetal drug exposure; however, we consider any exposure to fetotoxic medications as high risk, no matter the duration. In addition, while fetotoxic medication classification in this study followed the former FDA risk categories that were actively used during the timeframe of this study (2013–2014), these categories may overestimate fetal risk for anti-rheumatic drugs such as azathioprine (Category D)(41), leflunomide (Category X) (42) and many non-rheumatic medications (43). Sensitivity analyses suggested that azathioprine, which is considered relatively safe to use during pregnancy, did not influence our findings (18, 19, 33). Despite these limitations, our findings are generally consistent with prior work involving smaller samples with less disease diversity and with primarily survey methodology, and suggest that a minority of women with rheumatic diseases receive prescription contraception.

In summary, our analysis found a low prevalence of prescription contraception use among reproductive-age women with rheumatic diseases, even among those women who used potentially teratogenic medications. Gynecologists and PCPs appear to be particularly important resources for delivering contraceptive care. Rheumatologists may help to fill important remaining gaps in care by referring patients to gynecologists or PCPs providers, educating patients about the associations between disease activity, pregnancy, and fetal risks of certain rheumatic drugs, and helping to either prescribe contraception or partnering with other providers to ensure the safe prescription of contraception when appropriate. While our work highlights potential gaps in contraceptive access and women’s health care, findings should be substantiated through chart review, pharmacy registries, and/or other confirmatory methodologies. Future work should also identify personal and systemic barriers that limit the receipt of contraception and family planning care by women with rheumatic diseases. By identifying and implementing interventions that enhance consistent, comprehensive and high-quality reproductive health care, we may enhance the health and well-being of young women with rheumatic diseases, and their families.

Significance/Innovation.

-

−

This is the largest study to describe contraception use among reproductive-age women with rheumatic diseases

-

−

Low contraception usage was found among reproductive-age women with rheumatic diseases, even when using potentially fetotoxic medications

-

−

Gynecology and PCP visits were associated with overall prescription contraception, but nearly half of patients did not see a gynecologist or PCP over the study timeframe

Acknowledgements:

We acknowledge Seo Young Park and Kwonho Jeong for their assistance with statistical support.

M.B.T. was supported by grant number K12HS022989 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Funding Disclosures: M.E.B.C. is a consultant for UCB Pharma.

APPENDIX A

ICD-9 codes

| Diagnoses | ICD-9 Codes |

|---|---|

| Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome/antibodies | 289.81, 795.79 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 714.0 |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | 710.0 |

| Sjogren’s Syndrome | 710.0, 580.81-583.81 |

| Undifferentiated Connective Tissue Disease | 710.9 |

| Psoriatic Arthritis | 696 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis/Spondyloarthritis | 720.0, 720.9 |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | 550.0-555.2, 555.9, 556.0, 556.2, 556.5, 556.8, 556.9 |

| Systemic Sclerosis | 710.1 |

| Dermatomyostis | 710.3 |

| Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis | 714.30 |

| Mixed Connective Tissue Disease | 710.8 |

| Polymyositis | 710.4 |

| Bechet’s | 136.1 |

| Sarcoidosis | 135 |

| Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis/Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis |

446.4 |

| Still’s Disease | 714.2 |

| Takayasu Arteritis | 446.7 |

| Reactive Arthritis | 99.3 |

| Microscopic Polyangiitis | 446.0 |

ICD-9 codes for antiphospholipid antibodies and anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome are nonspecific. In addition to codes, accompanying diagnoses were reviewed to ensure that women were properly diagnosed.

APPENDIX B

Prescription Contraceptive Methods Categorized by Efficacy or Subtype

A. Highly-Effective Methods

Subdermal implant

Intrauterine device (IUD)

Surgical sterilization (tubal ligation, Essure procedure)

1. Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Methods (LARC)

Subdermal implant

IUD

B. Moderately-Effective Contraceptive Methods

Oral contraceptive pill

Transdermal patch

Vaginal ring

Depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate (shot)

C. Least Effective Contraceptive Methods (Rarely prescribed or least efficacious)

Condoms (male, female)

Sponges

Diaphragms

Spermicides

Withdrawal method

Fertility-based awareness methods

Emergency contraception

APPENDIX C

Frequency of Rheumatic Diagnoses in Cohort

| Rheumatic Diagnosis | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 615 (25.1) |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | 510 (20.8) |

| Sjogren’s Syndrome | 487 (19.8) |

| Undifferentiated connective tissue disease | 325 (13.2) |

| Psoriatic Arthritis | 208 (8.5) |

| Spondyloarthritis | 129 (5.3) |

| Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome/antibodies | 103 (4.2) |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | 99 (4.0) |

| Systemic sclerosis | 77 (3.1) |

| Dermatomyositis | 43 (1.8) |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 43 (1.8) |

| Mixed connective tissue disease | 41 (1.7) |

| Polymyositis | 36 (1.5) |

| Sarcoidosis | 17 (0.7) |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | 14 (0.6) |

| Still’s Disease | 7 (0.3) |

| Takayasu Arteritis | 6 (0.2) |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis | 3 (0.1) |

| Microscopic polyangiitis | 3 (0.1) |

Patients may have more than 1 diagnosis.

APPENDIX D

Frequency of Anti-Rheumatic Drugs Prescribed in Cohort (n=2455)

| Anti-rheumatic drug | N (%) |

| Abatacept | 50 (2.0) |

| Adalimumab | 225 (9.2) |

| Apremilast | 7 (0.29) |

| Azathioprine | 166 (6.8) |

| Belimumab | 19 (0.77) |

| Certolizumab pegol | 32 (1.3) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 8 (0.33) |

| Cyclosporine | 125 (5.1) |

| Etanercept | 244 (9.9) |

| Golimumab | 22 (0.90) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1210 (49.3) |

| Infliximab | 50 (2.0) |

| Leflunomide | 104 (4.3) |

| Methotrexate | 641 (26.1) |

| Rituximab | 17 (0.69) |

| Prednisone | 1423 (58.0) |

| Sulfasalazine | 182 (7.4) |

| Tacrolimus | 36 (1.5) |

| Tocilizumab | 28 (1.1) |

| Tofacitinib | 18 (0.7) |

Patients may use more than one anti-rheumatic drug.

Appendix E

FDA Pregnancy Class A, B, D, and X Medications Prescribed to Study Cohort during 2013–2014

Categorized as class A/B/C

Abatacept

Acarbose

Acebutolol hydrochloride

Acetaminophen

Acyclovir

Acyclovir sodium

Adalimumab

Afluzosin

Alendronate sodium

Alosetron hydrochloride

Amiloride hydrochloride

Amoxicillin clauvalanate

Amoxicillin trihydrate

Amoxicillin trihydrate

Amphotericin B

Amphotericin B lipid complex

Ampicillin sodium

Ampicillin trihydrate

Ampicillin/sulbactam

Anakinra

Ascorbic acid

Aspirin

Aripiprazole

Azatadine maleate

Azelaic acid

Azithromycin

Balsalazide disodium

Belimumab

Brimonidine tartrate

Buprenorphine/naloxone

Bupropion hydrochloride

Buspirone hydrochloride

Butenafine hydrochloride

Cabergoline

Caffeine citrated solution

Capsaicin

Carbenicillin indanyl sodium

Cefaclor

Cefadroxil hydrate

Cefazolin 50 mg/mL super eye drops

Cefazolin fortified 50 mg/mL eye drops

Cefazolin sodium

Cefdinir

Cefixime

Cefotetan disodium

Cefpodoxime proxetil

Ceftazidime

Ceftizoxime sodium

Ceftriaxone sodium

Cefuroxime axetil

Cephalexin MH

Certolizumab pegol

Cetirizine hydrochloride

Chlorhexidine gluconate

Chlorhexidine gluconate/isopropanol

Chlorpheniramine maleate

Chlorthalidone

Cholecalciferol

Cholestyramine/aspartame

Cholestyramine/sucrose

Ciclopirox olamine

Ciclopirox

Cimetidine

Cimetidine hydrochloride

Clemastine fumarate

Clindamycin 1% in Cetaphil moisturizing lotion

Clindamycin 2% in 70% isopropyl alcohol

Clindamycin 2% in Cetaphil moisturizing lotion

Clindamycin 2% in clotrimazole vaginal cream

Clindamycin 2% in Ionax astringent

Clindamycin 2% solution

Clindamycin hydrochloride

Clindamycin palmitate

Clindamycin phosphate

Clopidogrel bisulfate

Clotrimazole

Clotrimazole 3% topical solution

Clozapine

Colchicine

Colestipol hydrochloride

Cromolyn powder/acid mantle cream

Cromolyn sodium

Cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride

Cyclosporine

Cyproheptadine hydrochloride

Desmopressin acetate

Dexamethasone

Desoximetasone

Dexchlorpheniramine maleate

Dicloxacillin sodium

Dicyclomine hydrochloride

Didanosine

Diethylpropion hydrochloride

Dihydrotachysterol

Diltiazem hydrochloride

Diphenhydramine hydrochloride

Dipivefrin-Q6JX

Dipyridamole

Doxepin hydrochloride

Doxercalciferol

Duloxetine hydrochloride

Enoxaparin sodium

Ergocalciferol

Erythromycin base

Erythromycin base/ethyl alcohol

Erythromycin estolate

Erythromycin ethylsuccinate

Erythromycin stearate

Escitalopram oxalate

Esomeprazole mag trihydrate

Etanercept

Ethacrynic acid

Ethambutol hydrochloride

Famciclovir

Famotidine

Fenoprofen calcium

Fentanyl lozenge/transdermal patch

Flavoxate hydrochloride

Fludricortisone

Fluoxetine

Flurbiprofen

Flurbiprofen sodium

Folic acid

Folic acid/multivitamins

Furosemide

Gabapentin

Glatiramer acetate

Glimepiride

Glipizide

Glucagon

Glucagon, human recombinant

Glycopyrrolate

Golimumab

Granisetron hydrochloride

Guanfacine hydrochloride

Hydrochlorothiazide

Hydrochlorothiazide/amiloride hydrochloride

Hydrocodone bitartrate

Hydromorphone hydrochloride

Hydroxychloroquine

Hydrocortisone

Ibuprofen

Immune globulin

Indapamide

Infliximab

Insulin glargine, human recombinant analog

Insulin lispro

Insulin neutral protamine Hagedorn human recombinant

Insulin regular human recombinant

Insulin regular human recombinant buffered

Ipratropium bromide

Kaopectate/diphenhydramine EL 1:1

Ketoprofen

Lactulose

Lamotrigine

Lansoprazole

Levocarnitine

Levothyroxine sodium

Lidocaine 4% nasal spray

Lidocaine 5% in silver sulfadiazine cream

Lidocaine 5% ointment/orabase 1:1

Lidocaine hydrochloride (anesthetic)

Lidocaine hydrochloride

Lidocaine

Lidocaine/prilocaine

Lindane

Liothyronine sodium

Liotrix

Loperamide hydrochloride

Loracarbef

Loratadine

Magnesium gluconate

Magnesium sulfate

Maprotiline hydrochloride

Meloxicam

Meclizine hydrochloride

Meperidine hydrochloride

Meropenem

Mesalamine

Metformin hydrochloride

Methadone hydrochloride

Methyldopa

Methylprednisolone

Metoclopramide hydrochloride

Metolazone

Metronidazole

Metronidazole/sodium chloride

Miglitol

Milnacipran

Mirtazapine

Montelukast sodium

Morphine sulfate

Nafcillin sodium

Naftifine hydrochloride

Naproxen

Naproxen sodium

Naratriptan hydrochloride

Nedocromil sodium

Nelfinavir mesylate

Niacin

Niacinamide

Nitrofurantoin

Nitrofurantoin macrocrystal

Nitrofurantoin/nitrofuran macro

Nizatidine

Nortriptyline

Octreotide acetate

Ondansetron

Ondansetron hydrochloride

Orlistat

Oxiconazole nitrate

Oxybutynin chloride

Oxycodone hydrochloride

Oxycodone hydrochloride/acetaminophen

Oxymorphone hydrochloride

Pantoprazole sodium

Paregoric

Pemoline

Penciclovir

Penicillin G benzathine

Penicillin G potassium

Penicillin G procaine/penicillin G potassium

Penicillin G sodium

Penicillin V potassium

Pentosan polysulfate sodium

Pergolide mesylate

Permethrin

Phenazopyridine hydrochloride

Pindolol

Piperacillin sodium

Piperacillin sodium/tazobactam sodium

Pramipexole dihydrochloride

Praziquantel

Prednisone

Prenatal vitamins

Probenecid

Propranolol hydrochloride

Pyridoxine hydrochloride

Quetiapine fumarate

Rabeprazole sodium

Ranitidine hydrochloride

Rifabutin

Ritonavir

Risperidone

Rituximab

Rizatriptan

Ropinirole

Saquinavir

Sertraline

Sildenafil citrate

Silver sulfadiazine

Sotalol hydrochloride

Spectinomycin hydrochloride

Spironolactone

Sucralfate

Sulfasalazine

Sulindac

Sumatriptan succinate

Tacrolimus

Tadalafil

Tamsulosin hydrochloride

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

Terbinafine hydrochloride

Terbutaline sulfate

Thiamine hydrochloride

Thyroid hormone

Tiagabine hydrochloride

Ticlopidine hydrochloride

Tocilizumab

Tofacitinib

Torsemide

Tramadol

Tranexamic acid 4.8% solution

Trastuzumab

Ursodiol

Ustekinumab

Valacyclovir hydrochloride

Vancomycin 25 mg/mL eye drops

Vancomycin hydrochloride

Venlafaxine

Vitamin A

Vitamin E

Zafirlukast

Ziprasidone hydrochloride

Zolmitriptan

Zolpidem tartrate

Categorized as class D/X

Acitretin

Atorvastatin calcium

Alprazolam

Amikacin sulfate

Amiodarone hydrochloride

Amitriptyline hydrochloride/chlordiazepoxide

Anastrozole

Arsenic trioxide

Atenolol

Atorvastatin calcium

Azathioprine

Belladonna alkaloids/phenobarbital

Bexarotene

Bleomycin sulfate

Bosentan

Busulfan

Cadexomer iodine

Capecitabine

Carbamazepine

Carboplatin

Celecoxib

Cerivastatin sodium

Chlorambucil

Chlordiazepoxide hydrochloride

Cisplatin

Cladribine

Clidinium bromide/chlordiazepoxide

Clonazepam

Clorazepate dipotassium

Cyclophosphamide

Cytarabine

Dactinomycin

Danazol

Daunorubicin hydrochloride

Demeclocycline hydrochloride

Dexamethasone/diphenhydramine/nystatin/tetracycline solution

Dexamethasone/diphenhydramine/tetracycline 1:1:1

Diazepam

Diclofenac potassium

Diclofenac sodium

Diclofenac sodium/misoprostol

Dienestrol

Dihydroergotamine mesylate

Divalproex sodium

Docetaxel

Doxorubicin hydrochloride liposome

Doxorubicin hydrochloride

Doxycycline calcium

Doxycycline hyclate

Doxycycline monohydrate

Epirubicin hydrochloride

Ergotamine tartrade/caffeine

Ergotamine/belladonna/phenobarbital

Estazolam

Estradiol

Etoposide

Exemestane

Finasteride

Fluorouracil

Fluoxymesterone

Flurazepam hydrochloride

Flutamide

Gemcitabine hydrochloride

Gentamicin 14 mg/mL eye drops

Gentamicin fortified eye drops

Gentamicin in Ocean Nasal Spray (Fleming Pharmaceuticals, Fenton, Missouri)

Gentamicin sulfate

Gentamicin sulfate/sodium chloride

Gentamicin sulfate/prednisolone acetate

Goserelin acetate

Hydroxyurea

Idarubicin hydrochloride

Fosfamide

Ibuprofen

Imatinib mesylate

Imipramine hydrochloride

Imipramine pamoate

Indomethacin

Irinotecan hydrochloride

Isotretinoin

Leflunomide

Letrozole

Leuprolide acetate

Liraglutide

Lithium carbonate

Lorazepam

Lovastatin

Mechlorethamine 0.01% (10 mg %) in Aquaphor

Mechlorethamine hydrochloride

Meclofenamate sodium

Megestrol

Melphalan

Mephobarbital

Meprobamate

Mercaptopurine

Methimazole

Methotrexate sodium

Methyltestosterone

Methyltestosterone/estrogens

Midazolam hydrochloride

Minocycline hydrochloride

Misoprostol

Mitomycin

Mitoxantrone hydrochloride

Mycophenolate mofetil

Mycophenolate sodium

Neomycin sulfate

Nicotine

Nortriptyline hydrochloride

Olmesartan

Oxandrolone

Oxazepam

Paclitaxel, semisynthetic

Pamidronate disodium

Paroxetine

Penicillamine

Pentobarbital sodium

Phenobarbital

Phenytoin

Phenytoin sodium extended

Potassium iodide (for oral use)

Potassium iodide/iodine

Povidone–iodine

Povidone–iodine swabs

Pravastatin sodium

Prednisone-delayed release

Primidone

Procarbazine hydrochloride

Propylthiouracil

Quazepam

Quinine sulfate

Raloxifene hydrochloride

Ribavarin

Secobarbital sodium

Simvastatin

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim

Tazarotene

Tamoxifen citrate

Temazepam

Temozolomide

Testosterone/cypionate/enanthate

Tetracycline hydrochloride

Tetracycline, nystatin, hydrocortisone mouthwash

Tetracycline, nystatin, hydrocortisone powder, water

Thalidomide

Thioguanine

Tobramycin fortified ophthalmic drops

Tobramycin sulfate

Tobramycin sulfate/dexamethasone

Tobramycin/sodium chloride

Topiramate

Toremifene citrate

Triazolam

Tretinoin

Tretinoin A 0.05% cream/hydrocortisone 1% cream

Tretinoin

Valproic acid

Vinblastine sulfate

Vincristine sulfate

Vinorelbine tartrate

Warfarin sodium

REFERENCES

- 1.Daniels KDJ, Jones J. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–44: United States, 2011–2013 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Huong D, Wechsler B, Vauthier-Brouzes D, Seebacher J, Lefebvre G, Bletry O, et al. Outcome of planned pregnancies in systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective study on 62 pregnancies. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36(7):772–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buyon JP, Kim MY, Guerra MM, Laskin CA, Petri M, Lockshin MD, et al. Predictors of Pregnancy Outcomes in Patients With Lupus: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(3):153–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinal-Fernandez I, Selva-O’Callaghan A, Fernandez-Codina A, Martinez-Gomez X, Rodrigo-Pendas J, Perez-Lopez J, et al. “Pregnancy in adult-onset idiopathic inflammatory myopathy”: report from a cohort of myositis patients from a single center. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(2):234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taraborelli M, Ramoni V, Brucato A, Airo P, Bajocchi G, Bellisai F, et al. Brief report: successful pregnancies but a higher risk of preterm births in patients with systemic sclerosis: an Italian multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):1970–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostensen M, Fuhrer L, Mathieu R, Seitz M, Villiger PM. A prospective study of pregnant patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis using validated clinical instruments. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(10):1212–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vancsa A, Ponyi A, Constantin T, Zeher M, Danko K. Pregnancy outcome in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Rheumatol Int. 2007;27(5):435–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clowse ME, Richeson RL, Pieper C, Merkel PA. Pregnancy outcomes among patients with vasculitis. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65(8):1370–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakravarty EF, Khanna D, Chung L. Pregnancy outcomes in systemic sclerosis, primary pulmonary hypertension, and sickle cell disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(4):927–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yazdany J, Trupin L, Kaiser R, Schmajuk G, Gillis JZ, Chakravarty E, et al. Contraceptive counseling and use among women with systemic lupus erythematosus: a gap in health care quality? Arthritis Care Res 2011;63(3):358–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwarz EB, Manzi S. Risk of unintended pregnancy among women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):863–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chakravarty E, Clowse ME, Pushparajah DS, Mertens S, Gordon C. Family planning and pregnancy issues for women with systemic inflammatory diseases: patient and physician perspectives. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e004081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Food and Drug Administration: Pregnancy, Lactation, and Reproductive Potential: Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products — Content and Format. Department of Health and Human Services Federal Register, Vol. 9; No. 233: 12/2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briggs GGFR, Sumner JY. Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. 9th Edition: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steiner MJ, Trussell J, Mehta N, Condon S, Subramaniam S, Bourne D. Communicating contraceptive effectiveness: A randomized controlled trial to inform a World Health Organization family planning handbook. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(1):85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callegari LS, Zhao X, Schwarz EB, Rosenfeld E, Mor MK, Borrero S. Racial/ethnic differences in contraceptive preferences, beliefs, and self-efficacy among women veterans. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(5):504 e1–e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nexplanon Clinical Training Program. Available from: http://www.nexplanon-usa.com/en/hcp/services-and-support/request-training/request-form/index.asp. Accessed 6/2018.

- 18.Gotestam Skorpen C, Hoeltzenbein M, Tincani A, Fischer-Betz R, Elefant E, Chambers C, et al. The EULAR points to consider for use of antirheumatic drugs before pregnancy, and during pregnancy and lactation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(5):795–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kavanaugh A, Cush JJ, Ahmed MS, Bermas BL, Chakravarty E, Chambers C, et al. Proceedings from the American College of Rheumatology Reproductive Health Summit: the management of fertility, pregnancy, and lactation in women with autoimmune and systemic inflammatory diseases. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67(3):313–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwarz EB, Postlethwaite DA, Hung YY, Armstrong MA. Documentation of contraception and pregnancy when prescribing potentially teratogenic medications for reproductive-age women. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(6):370–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeNoble AE, Hall KS, Xu X, Zochowski MK, Piehl K, Dalton VK. Receipt of prescription contraception by commercially insured women with chronic medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1213–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartels CM, Roberts TJ, Hansen KE, Jacobs EA, Gilmore A, Maxcy C, et al. Rheumatologist and Primary Care Management of Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Patient and Provider Perspectives. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(4):415–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: USPTF Recommendation Statement; Final Recommendations. Ann Intern Med.151:716–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Harris R, Starkey M, Denberg TD, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of P. Screening pelvic examination in adult women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(1):67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moyer VA, Force USPST. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880–91, W312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curtis KJT, Tepper NK, Zapata L, Horton L, Jamieson DJ, Whiteman MK. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andreoli L, Bertsias GK, Agmon-Levin N, Brown S, Cervera R, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, et al. EULAR recommendations for women’s health and the management of family planning, assisted reproduction, pregnancy and menopause in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and/or antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(3):476–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr., Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(1):1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):960–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birru Talabi M, Clowse MEB, Schwarz EB, Callegari LS, Moreland L, Borrero S. Family Planning Counseling for Women with Rheumatic Diseases. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clowse ME. Managing contraception and pregnancy in the rheumatologic diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24(3):373–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meade T, Dowswell E, Manolios N, Sharpe L. The motherhood choices decision aid for women with rheumatoid arthritis increases knowledge and reduces decisional conflict: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flint J, Panchal S, Hurrell A, van de Venne M, Gayed M, Schreiber K, et al. BSR and BHPR guideline on prescribing drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding-Part I: standard and biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and corticosteroids. Rheumatology. 2016;55(9):1693–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flint J, Panchal S, Hurrell A, van de Venne M, Gayed M, Schreiber K, et al. BSR and BHPR guideline on prescribing drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding-Part II: analgesics and other drugs used in rheumatology practice. Rheumatology. 2016;55(9):1698–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Organization of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS): MothertoBaby. Available from: https://mothertobaby.org. Accessed 6/2018.

- 36.Ostensen M Sexual and reproductive health in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13(8):485–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ostensen M Preconception Counseling. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2017;43(2):189–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ntali S, Damjanov N, Drakakis P, Ionescu R, Kalinova D, Rashkov R, et al. Women’s health and fertility, family planning and pregnancy in immune-mediated rheumatic diseases: a report from a south-eastern European Expert Meeting. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(6):959–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alkema L, Kantorova V, Menozzi C, Biddlecom A. National, regional, and global rates and trends in contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning between 1990 and 2015: a systematic and comprehensive analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1642–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dehlendorf C, Park SY, Emeremni CA, Comer D, Vincett K, Borrero S. Racial/ethnic disparities in contraceptive use: variation by age and women’s reproductive experiences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(6):526 e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldstein LH, Dolinsky G, Greenberg R, Schaefer C, Cohen-Kerem R, Diav-Citrin O, et al. Pregnancy outcome of women exposed to azathioprine during pregnancy. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79(10):696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chambers CD, Johnson DL, Robinson LK, Braddock SR, Xu R, Lopez-Jimenez J, et al. Birth outcomes in women who have taken leflunomide during pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(5):1494–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gentile S, Bellantuono C. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure during early pregnancy and the risk of fetal major malformations: focus on paroxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(3):414–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]