Abstract

The Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS) is an ongoing community-based epidemiological study of lifestyle-related disease involving dynamic prospective cohorts of approximately 12,000 adults from five communities of Japan: Ikawa, Ishizawa and Kita-Utetsu (Akita Prefecture), Minami-Takayasu (Osaka Prefecture), Noichi (Kochi Prefecture), and Kyowa (Ibaraki Prefecture). One of the most notable features of CIRCS is that it is not only an observational cohort study to identify risk factors for cardiovascular diseases (CVD), such as stroke, coronary heart disease, and sudden cardiac death, but it also involves prevention programs for CVD. Using basic, clinical, epidemiological, and statistical techniques, CIRCS has clarified characteristics of CVD and the related risk factors to develop specific methodologies towards CVD prevention in Japanese middle-aged or older adults for more than half a century.

Key words: community intervention, coronary heart disease, follow-up study, stroke

ORIGIN OF THE COHORT

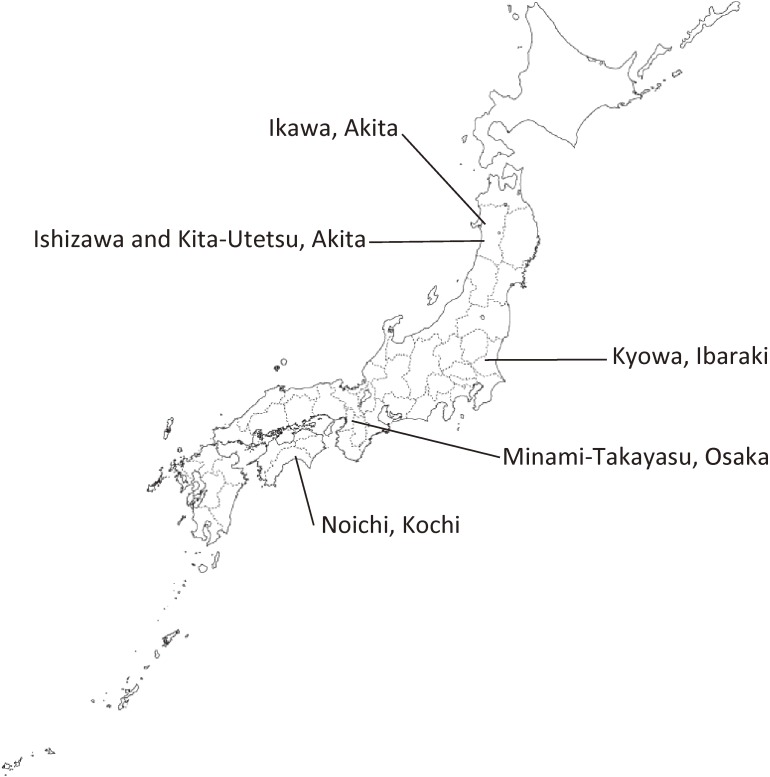

The Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS) is an ongoing community-based epidemiological study using dynamic prospective cohorts involving approximately 12,000 persons per 4-to-6-year period (more than 65,000 people in total) in five Japanese communities: (1) Ikawa in Akita Prefecture (northeastern rural community); (2) Ishizawa and Kita-Utetsu, Honjo (presently Yuri-Honjo) City in Akita Prefecture (northeastern rural communities); (3) Minami-Takayasu, Yao City in Osaka Prefecture (mid-western suburban community); (4) Noichi, Konan City in Kochi Prefecture (western rural community); and (5) Kyowa, Chikusei City in Ibaraki Prefecture (mid-eastern rural community) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Location of study fields of the CIRCS.

In 1963, Dr. Yoshio Komachi, a physician and epidemiologist of the Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases (presently Professor Emeritus of the University of Tsukuba), launched demonstrative surveys to reveal which lifestyle activities, especially those related to traditional Japanese lifestyle, were adversely associated with stroke, the leading cause of death in Japan in the 1960s, and also how to prevent it.1 Komachi and his colleagues started a comparative survey between communities in Akita and Osaka, where, nationally, mortality from stroke had been the highest and lowest, respectively. In 1969, they added the community of Noichi and, in 1981, they added the community of Kyowa as new survey fields. The surveys have been conducted annually, and the survey methods have been unified across those communities. The annual surveys and follow-up work in Ishizawa/Kita-Utetsu and Noichi terminated in 1987 and 2005, respectively. Community registration of stroke and coronary heart disease and mortality surveillance has been done for more than 55 years. Since 1999, registration was started for disabling dementia, based on the Japanese Long Term Care Insurance system.

In the initial ecological and cross-sectional studies by Komachi and his colleagues, which compared the incidence of stroke and coronary heart disease between rural Akita and suburban Osaka, they found that the incidence of stroke (especially that of cerebral hemorrhage), blood pressure levels, and salt intake were much higher in Akita, while the incidence of coronary heart disease, serum total cholesterol levels, and fat and protein intakes were lower. They observed that the lifestyle of people in Akita in the 1960s and 70s was characterized by a high consumption of traditional Japanese foods, such as a large intake of rice, miso soup, salt-preserved fish, pickles, soy sauce, and salt, and a small intake of animal products, as well as heavy agricultural work. Among traditional Akita farmers, lean middle-aged men were more likely to suffer from stroke. Based on their observations, Komachi and his colleagues hypothesized that the most important determinant of stroke was hypertension and not hyperlipidemia or diabetes in Japanese. They also hypothesized that the association between serum total cholesterol levels and cardiovascular disease (CVD) may not be linear, and that very low cholesterol levels, as well as very high blood pressure levels, would carry an adverse impact on risk of stroke, especially intraparenchymal hemorrhage. They also found that high cholesterol levels are positively associated with risk of coronary heart disease, confirming the findings of previous frontier studies: the Minnesota Business and Professional Men’s,2 Framingham Heart,3 and Seven Countries studies.4

Komachi’s U-shaped hypothesis caused strong debate, coming under criticism from some western researchers who suggested that the Japanese physicians may have misdiagnosed coronary heart disease as stroke. They also questioned the accuracy of measurement of the serum total cholesterol. In response, Komachi and his colleagues, as well as the Hisayama Study group, demonstrated that stroke diagnosis was validated using autopsy findings.5,6 They standardized the epidemiological criteria of stroke and coronary heart disease according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria7 since the 1960s, and have used the findings of computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the detailed classification of stroke types since the 1980s.8,9 In 1975, their lipid laboratory participated in the CDC-NHLBI Lipid Standardization Program of the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and since then the laboratory has become well-known for its accuracy and precision.10 From 1992, the laboratory became a member of the Cholesterol Reference Method Laboratory Network (CDC/CRMLN).

The U-shape hypothesis gained wider acceptance after 1989 through the publication of a prospective study conducted in Akita as a part of CIRCS,11 and a cohort study, the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT), in the United States,12 which independently showed the inverse association between low total cholesterol levels and risk of intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Following these reports, the NHLBI held an international conference on low blood cholesterol in 1990 to review and discuss existing data on the U-shaped relationship between total cholesterol levels and mortality from CVD and other causes from 19 cohort studies worldwide.13 The inverse association between the total or low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels and risk of intraparenchymal hemorrhage has since been repeatedly replicated in meta-analyses and cohort studies.14

The study name ‘CIRCS’ was first used in 2008, before which there was no specific study name; sometimes it was referred to as the ‘Akita-Osaka Study’15 or ‘Osaka Medical Center Study’.16 To search the PubMed database for CIRCS papers published on or before 2008, it is useful to use the phrase: “Shimamoto T and Tsukuba”. The key features of CIRCS have previously been introduced in the literature.17,18

CIRCS has been conducted as a part of community prevention program and has, therefore, been sponsored mainly by each local municipality. Osaka Prefecture, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, and other relevant organizations have also supported CIRCS.

SCOPE AND FEATURES

CIRCS is one of the oldest epidemiological studies of CVDs in Japan. When CIRCS was first started in the 1960s, strategies for prevention of CVDs, especially of stroke, were not yet established in Japan. The public health mission of CIRCS was to find out ways to improve stroke prevention in community settings. A systematic mass screening was begun, which constituted measurements of blood pressure, electrocardiogram, ocular funduscopy, and blood test, all of which were not commonly carried out at that time, and the technique for physical examination of the general population had also not yet been established. CIRCS strictly standardized each test as an exposure factor according to international standards. Participants were interviewed about lifestyle-related factors, such as employment, smoking, alcohol, diet, and physical activity. The main outcome measures were incidence of stroke (intraparenchymal hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and cerebral infarction), coronary heart disease (myocardial infarction, effort angina pectoris, and sudden cardiac death), and dementia. Based on CT/MRI imaging, cerebral infarction was further classified in subtypes (lacunar, large-artery occlusive and embolic infarctions). CIRCS is composed of several community-based cohorts with different lifestyles and living environments, which makes it possible to compare incidence of CVD and its risk factors to identify different or common features among the participating communities and to clarify the characteristics of CVD in Japan.

CIRCS has a number of other important characteristics. First, as well as the hard endpoints mentioned above, through its annual surveys CIRCS has been used to identify intermediate outcomes, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, and gout. Second, repeat measures or trajectory analyses can be done based on annual survey data. Third, dietary information, based on 24-hour dietary recall, is available. Fourth, data from over more than 5 decades can be analyzed. Finally, serum samples dating back from the 1980s have been stored and are available for research.

Building and maintaining the cohort

The first survey was conducted in 1963 and included the following examinations: medical history, height, weight, blood pressure, physical examination, urinalysis, laboratory measurements of serum total cholesterol and protein, electrocardiogram, color photographs of the right ocular fundus, and an interview for assessing lifestyle factors.11 This examination system was novel in Japan at that time. These ongoing surveys, alongside some additional examinations, have been conducted annually with the aim of finding of novel risk factors and measures for prevention of CVD.

There follows a brief description for each of the major examinations. (1) Trained physicians, nurses, or technicians measured systolic and fifth-phase diastolic blood pressures using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer placed on the right arm of the participants who had been resting for at least 5 minutes prior to the measurement. (2) Blood samples were collected while the participants were quietly seated. The blood was drawn into siliconized vacuum tubes and was generally kept standing for 10 to 30 minutes at room temperature to let the blood clot before being centrifuged at 1,300 to 1,500 × g for approximately 15 minutes. The serum was separated and stored at −80°C awaiting laboratory analyses. As examples of the laboratory analyses performed, serum total cholesterol was measured using the Zac-Henly method from 1963 to 1974, the Liebermann-Burchard direct method from 1974 to 1986, and the enzymatic method from 1986 to the present. Glucose was measured using the cupric-neocuproine method from 1975 to 1986, the hexokinase method from 1986 to 1993, the glucokinase method from 1993 to 2001 period, and the hexokinase method from 2001 to the present. All blood samples were measured using standardized protocols at the laboratory of the Osaka Medical Center for Health Science and Promotion (currently, the Osaka Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention); and this consistence over a 55-year period has allowed for the investigation of long-term trends. (3) Electrocardiogram was measured in the supine position. Two physicians independently coded each record of electrocardiogram, based on the Minnesota Code. If the codes were in agreement, they were accepted, while disputed codes were discussed by the two physicians, and if necessary, a third experienced physician arbitrated. (4) Color photographs taken of the right ocular fundus were independently read and coded by two trained physicians using a modified Scheie classification. Agreement and disagreement over classifications were dealt with in the same manner as described for electrocardiograms.

With regard to stroke and coronary heart disease registration, CIRCS investigated the following ascertainment sources in addition to all hospitalized cases: baseline surveys, death certificates, ambulance records, national insurance claims, and reports from local physicians, public health nurses, and health volunteers. In order to validate the diagnoses, all living patients were either visited or invited to baseline surveys or their medical history was obtained from their families. Trained physicians reviewed medical records in the local clinics and hospitals. In the cases of deceased participants, their histories were obtained from their families and/or attending physicians, and medical records were reviewed. Modified criteria of the National Survey of Stroke7 and the WHO Expert Committee9 were used for the diagnoses of coronary heart disease and stroke, respectively. The CT and/or MRI images were available in approximately 60% of stroke cases in the 1980s and over 90% thereafter, and these images were used to classify the cases into subtypes based on the affected site.8

First publication

The first CIRCS-related paper was published in 1964 reporting the findings of health examination in two areas of Akita prefecture (Ikawa and Yuri) and two areas of Osaka prefecture (Akegawa area in Yao and Nose).19 At that time, moderate-to-severe hypertension was more prevalent in Akita than in Osaka: the prevalence of hypertension defined using WHO criteria (systolic blood pressure ≥160 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥95 mm Hg) was around 25% in Akita and around 10% in Osaka among residents aged 40–54 years. Among those aged 55–64 years, the corresponding prevalence was around 50% in Akita and around 30% in Osaka. Moreover, in both areas, half of moderate-to-severe hypertension was categorized into severe hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥180 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥110 mm Hg). Such a large difference in blood pressure levels between Akita and Osaka suggested a large regional difference in annual incidence rate of stroke, which was indeed reported several years later.20 The annual incidence rate of stroke was about 2-fold higher in Akita than that in Osaka: among residents aged 40–69 years, the annual incidence rate was 5.0 cases/1,000 population in Nose (Osaka), 5.6 cases/1,000 population in Yao (Osaka), 10.4 cases/1,000 population in Ikawa (Akita), and 12.3 cases/1,000 population in Yuri (Akita). This regional inequality regarding stroke incidence justified the need for intensive intervention programs for stroke, especially in Akita.

Most cited papers

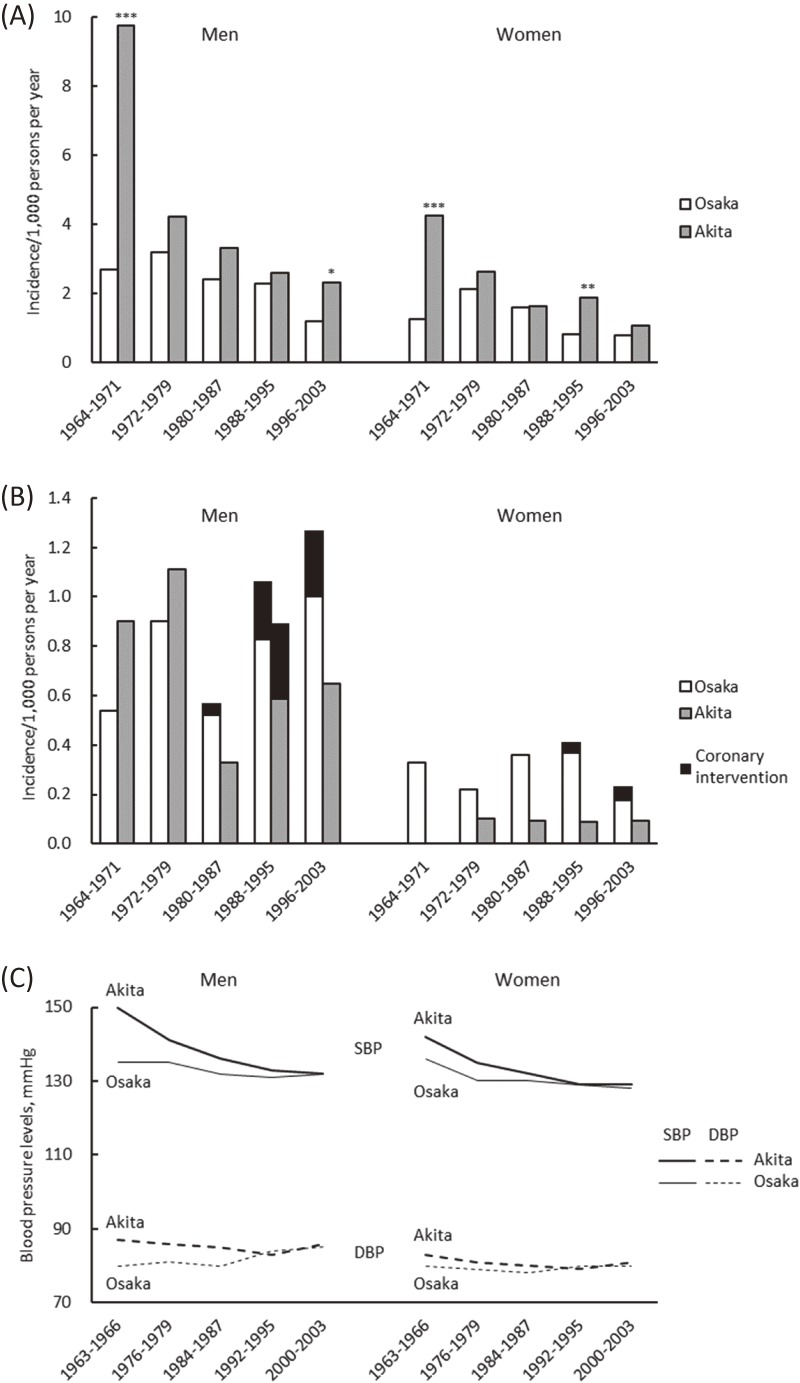

Two decades after the establishment of CIRCS, the time trend of CVD incidence and its risk factors in Ikawa, a rural town of Akita prefecture between 1964–68 and 1979–83 was reported by Shimamoto et al,11 which is the most cited paper from CIRCS. That study was updated up to 2003 and expanded to include a district of Yao City, Osaka Prefecture, a suburban area of mid-western Japan.15 In both Ikawa and Yao, the age-adjusted annual incidence of total stroke (cases/1,000 population) among both men and women aged 40–69 years was declining through 2003: these figures changed from 9.7 for men and 4.2 for women in 1964–1971 to 2.3 for men and 1.1 for women in 1996–2003 in Ikawa; and from 2.7 for men and 1.3 for women to 1.2 for men and 0.8 for women in Yao, respectively (Figure 2A). Regarding coronary heart disease, the age-adjusted incidence in Ikawa decreased slightly through 2003, but the trend was not statistically significant due to the low incidence (Figure 2B). In contrast to Ikawa, the incidence of coronary heart disease in Yao significantly increased among men (from 0.6 cases/1,000 population in 1980–1987 to 1.3 cases/1,000 population in 1996–2003). In terms of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels (Figure 2C) and the proportion of patients with hypertension decreased among men and women in both areas, while mean levels of serum total cholesterol increased. The proportion of patients with medication use for hypertension and high cholesterol also increased. Among men, the prevalence of smoking and heavy drinking declined. During the early period in Ikawa, serum levels of total protein was elevated, which was in part reflected by an increased daily meat intake from 5.8% of energy to 7.1% of energy among men aged 40–59 years.11

Figure 2. Trends for age-adjusted incidence of stroke (A), coronary heart disease (B) and blood pressure levels (C). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 for differences between Akita and Osaka. (Modified from Kitamura, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:71–79).

Other features

One of the most notable features of CIRCS is, again, not only its usefulness for identifying risk factors for CVD, but also as a platform for the introduction of prevention programs for CVD and their risk factors using basic, clinical, epidemiological, and statistical techniques.

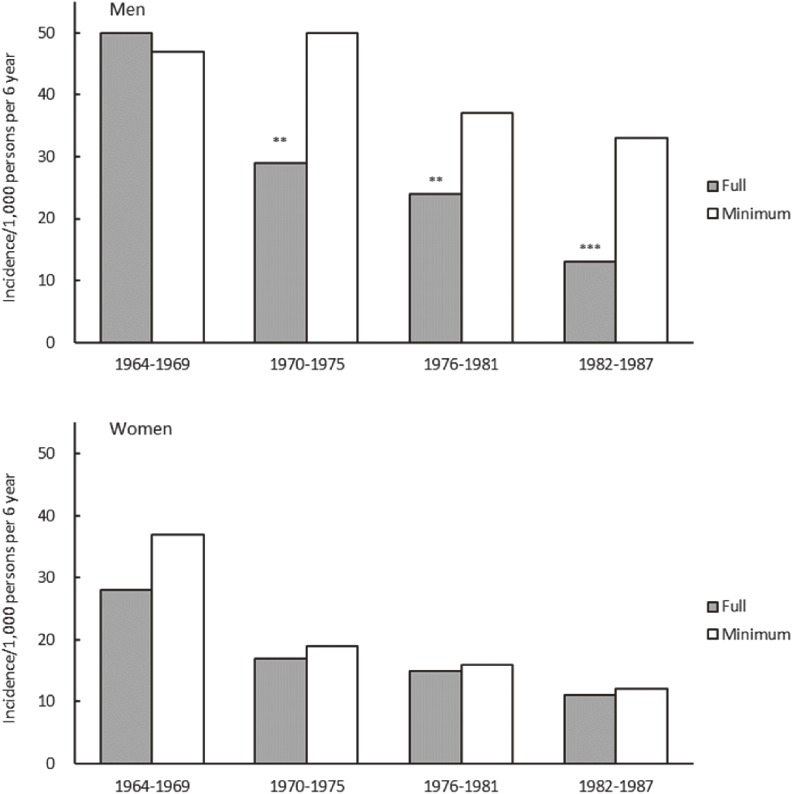

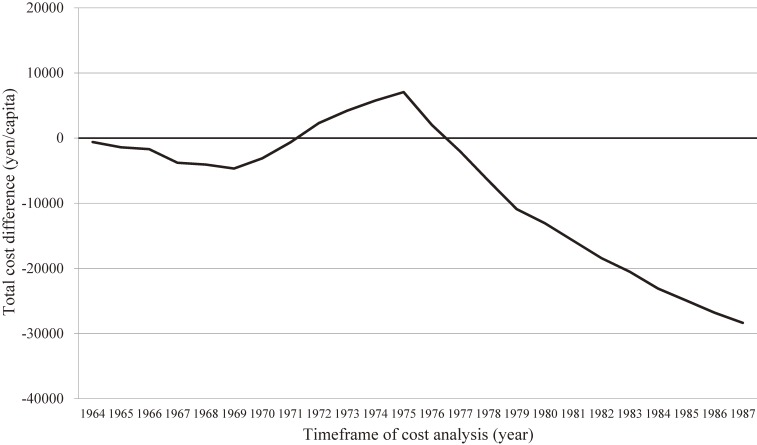

Because CIRCS is a dynamic cohort study, which has consistently performed baseline surveys and has conducted CVD surveillance every year since 1963, it has also allowed for the reporting of trends for stroke and coronary heart disease incidences and their risk factors11,15,21 and impacts of health education programs on hypertension22 and hypercholesterolemia.23 There follows an introduction to two examples of prevention programs that grew out of CIRCS. First, in a report of the effects of a long-term hypertension control program for stroke prevention in communities24 (Figure 3) that compared two communities for trends in blood pressure levels and stroke incidence and prevalence between 1963 and 1987, Ikawa, one of two communities, received a full range of community-wide hypertension interventions, while the other had a minimal intervention. In men, stroke incidence and prevalence declined in the full-intervention area (Ikawa) more than in the minimal-intervention community, and differential trends in systolic blood pressure levels appeared to explain the larger decline in stroke. Second, in a report on the cost-effectiveness of this long-term hypertension control program25 (Figure 4) costs of public health services and of treatment for patients with hypertension or stroke in the full-intervention community (Ikawa) and minimal-intervention communities were compared. It was found that the program in the full-intervention community became cost saving 13 years after its initiation; the incremental costs reduced by 28,358 Japanese yen per capita over 24 years.

Figure 3. Trends for age-adjusted incidence of stroke in full and minimal intervention communities. Difference from the minimal intervention community: **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (Data from Iso, et al. Stroke 1998;29:1510–1518).

Figure 4. Cost analyses of the hypertension detection and control program, 1964–1987. X-axis: Time frame of cost analysis (t). Y-axis: Total cost difference by year defined as follows: Total cost difference = , t = 1964–1987, where CA stands for total cost (after adjustment for consumer price index) in the full intervention community and CB stands for that in the minimal intervention community. Discount rate was 4% per year. (Reprinted from Yamagishi, et al. J Hypertens 2012;30:1874–1879).

CIRCS has led to the identification of several novel risk/preventive factors for CVD: lipids (eg, serum fatty acids composition26,27 and high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol particle size28), glucose tolerance (non-fasting blood glucose29,30), other biochemical factors (serum liver/biliary tract enzymes,31,32 serum homocysteine,33 serum C-reactive protein,34 and adiponectins35), hematological factors (leukocyte counts36), fibrinolytic factors (plasma fibrinogen37–39), electrocardiographic factors (ischemic abnormalities40,41 and Brugada-type electrocardiogram42), other physiological factors (carotid atherosclerosis43 and ankle-brachial blood pressure index44), dietary factors (fat and protein intakes45), psychosomatic factors (depressive symptoms46), height,47 snoring,48 metabolic syndrome,49,50 chronic kidney disease,51 and subclinical end-organ damage,52 as well as traditional risk factors (eg, alcohol,53–55 smoking,56 blood glucose/diabetes,57,58 blood pressure,1,5,11,59 total-,1,5,11 LDL-,60 non-HDL-61 and HDL-cholesterols,62,63 and triglycerides64,65). Recent reports included risk or preventive factors for dementia, such as smoking,66 C-reactive protein,67 serum coenzyme Q10,68 serum α-linoleic acid,69 and retinal vascular changes.70 Cross-cultural comparison studies of lipids,71–73 hemostatic factors,74–77 serum sialic acid,78 and sleep-disordered breathing79 with American populations have also been conducted. CIRCS has also been involved in several international or domestic collaborative studies, such as the Prospective Studies Collaboration,80 Fibrinogen Studies Collaboration,80 Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration,81 Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium,82 Japan Arteriosclerosis Longitudinal Study,83 Japan Arteriosclerosis Longitudinal Study-Existing Cohorts Combine,84 and Evidence for Cardiovascular Prevention from Observational Cohorts in Japan Study.85 These studies have contributed to building evidence on prevention of CVD not only for Japanese, but also for people across the world.

Historical impact on global and local health

During the past half century, CIRCS has continued to provide scientific evidence on issues of public health in Japan. One of the important findings that CIRCS showed is that the fact stroke is preventable via screening and controlling hypertension as well as through lifestyle modifications, such as reduction of salt intake, improvements of nutritional balance, and proper rest and physical activity. Based on the CIRCS findings, the Japanese government launched the first stroke prevention program across a few model municipalities in 1969, which was mainly composed of hypertension screening.86 Since then, the program was gradually extended to other municipalities and eventually the cardiovascular screening system was established in 1982 under the Health and Medical Service Act for the Aged, which made every municipality responsible for offering screening and preventive activities.86 Since 2008, a screening system by health insurers has been conducted, which focuses on prevention and control of metabolic syndrome under the Act on Assurance of Medical Care for Elderly People.

The findings from CIRCS, an ongoing dynamic cohort study, can be applicable not only to the other East Asian countries, but also to Southeast Asian and African countries with high stroke and low coronary heart disease. The CIRCS measures were introduced by the WHO in 2013 as a model program to defeat stroke.87

This seminal epidemiological study revealed that risk factors and characteristics of CVD were in part different between Japan and the United States/Europe and that it was necessary to develop distinct ways of prevention for CVD in the Japanese context. CIRCS has provided scientific evidence to aid the development of national health projects including the basic health checkup systems aimed at prevention of CVD and promotion of health in communities.

The CIRCS Investigators

CIRCS has been led by Yoshio Komachi (Professor Emeritus of University of Tsukuba), Minoru Iida, Hideki Ozawa, the late Takashi Shimamoto (Professor Emeritus of University of Tsukuba), the late Masamitsu Konishi (Professor Emeritus of Ehime University), and Yoshinori Ishikawa. The present investigators of CIRCS are as follows: Hiroyasu Iso, Hironori Imano, Renzhe Cui, Isao Muraki, Hiroyuki Noda, and Hiroshige Jinnnouchi (Osaka University), Masahiko Kiyama, Takeo Okada, Yuji Shimizu, Mina Hayama-Terada, and Yasuhiko Kubota (Osaka Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention), Tomoko Sankai, Kazumasa Yamagishi, and Mizuki Sata (University of Tsukuba), Isao Koyama and Masakazu Nakamura (National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center), Isao Saito (Oita University), Koutatsu Maruyama (Ehime University), Shinichi Sato (Chiba Prefectural Institute of Public Health), Mitsumasa Umesawa and Masanori Nagao (Dokkyo Medical University), Takeshi Tanigawa and Ai Ikeda (Juntendo University), Tetsuya Ohira (Fukushima Medical University), and Akihiko Kitamura (Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Medical Center).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the staff and residents of Ikawa Town and Yuri-Honjo, Chikusei, Yao and Konan Cities, and staff of the Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease (1963–2001), Osaka Medical Center for Health Science and Promotion (2001–2012), and Osaka Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention (2012-present) for their dedicated and important contributions. The authors thank Thomas Mayers, Medical English Communications Center, University of Tsukuba for editorial assistance.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Komachi Y, Iida M, Shimamoto T, Chikayama Y, Takahashi H. Geographic and occupational comparisons of risk factors in cardiovascular diseases in Japan. Jpn Circ J. 1971;35:189–207. 10.1253/jcj.35.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keys A, Taylor HL, Blackburn H, Brozek J, Anderson JT, Simonson E. Coronary heart disease among Minnesota Business and Professional Men followed fifteen years. Circulation. 1963;28:381–395. 10.1161/01.CIR.28.3.381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawber TR, Moore FE, Mann GV. Coronary heart disease in the Framingham study. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1957;47:4–24. 10.2105/AJPH.47.4_Pt_2.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verschuren WM, Jacobs DR, Bloemberg BP, et al. . Serum total cholesterol and long-term coronary heart disease mortality in different cultures. Twenty-five-year follow-up of the seven countries study. JAMA. 1995;274:131–136. 10.1001/jama.1995.03530020049031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueshima H, Iida M, Shimamoto T, et al. . Multivariate analysis of risk factors for stroke. Eight-year follow-up study of farming villages in Akita, Japan. Prev Med. 1980;9:722–740. 10.1016/0091-7435(80)90017-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasuo Y, Ueda K, Kiyohara Y, et al. . Accuracy of diagnosis on death certificates for underlying causes of death in a long-term autopsy-based population study in Hisayama, Japan; with special reference to cardiovascular diseases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:577–584. 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90154-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO Expert Committee on Arterial Hypertension and Ischaemic Heart Disease & World Health Organization. Arterial hypertension and ischaemic heart disease: preventive aspects, report of an expert committee. WHO Technical Report Series No 231. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1962.

- 8.Walker AE, Robins M, Weinfeld FD. The National Survey of Stroke. Clinical findings. Stroke. 1981;12(2 Pt 2 Suppl 1):I13–I44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iso H, Rexrode K, Hennekens CH, Manson JE. Application of computer tomography-oriented criteria for stroke subtype classification in a prospective study. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:81–87. 10.1016/S1047-2797(99)00040-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura M. Organization and standardization activity of the CDC and CRMLN [homepage on the Internet]; c2008. Available from: http://www.osaka-ganjun.jp/effort/cvd/cdc/pdf/intro01.pdf.

- 11.Shimamoto T, Komachi Y, Inada H, et al. . Trends for coronary heart disease and stroke and their risk factors in Japan. Circulation. 1989;79:503–515. 10.1161/01.CIR.79.3.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iso H, Jacobs DR Jr, Wentworth D, Neaton JD, Cohen JD. Serum cholesterol levels and six-year mortality from stroke in 350,977 men screened for the multiple risk factor intervention trial. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:904–910. 10.1056/NEJM198904063201405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs D, Blackburn H, Higgins M, et al. . Report of the Conference on Low Blood Cholesterol: Mortality Associations. Circulation. 1992;86:1046–1060. 10.1161/01.CIR.86.3.1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prospective Studies Collaboration Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55000 vascular deaths. Lancet. 2007;370:1829–1839. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitamura A, Sato S, Kiyama M, et al. . Trends in the incidence of coronary heart disease and stroke and their risk factors in Japan, 1964 to 2003: the Akita-Osaka study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:71–79. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.University of Minnesota. Heart Attack Prevention: A history of cardiovascular disease epidemiology [homepage on the Internet]. Available from: http://www.epi.umn.edu/cvdepi/study-synopsis/osaka-medical-center-study/.

- 17.Ohira T. Psychological distress and cardiovascular disease: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). J Epidemiol. 2010;20:185–191. 10.2188/jea.JE20100011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imano H, Kitamura A, Kiyama M, et al. Usefulness of skinfold thickness measurements for determining body fat distribution and disease risk for Japanese men and women. In: Preedy V, editor. Handbook of Anthropometry: Physical Measures of Human Form in Health and Disease. New York: Springer; 2012:2667–2678. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komachi Y, Ozawa H, Iida M, Tominaga S. An epidemiological study on Japanese hypertension and ischemic heart diseases. Annual Report of the Center for Adult Diseases. 1964;4:118–127. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komachi Y, Ozawa H, Iida M, Tominaga S, Chikayama Y. Epidemiological studies on Japanese hypertension and ischemic heart diseases. Jpn Circ J. 1967;31:563–580. 10.1253/jcj.31.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hori M, Kitamura A, Kiyama M, et al. . Fifty-year time trends in blood pressures, body mass index and their relations in a Japanese community: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24:518–529. 10.5551/jat.36178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iso H, Shimamoto T, Yokota K, Sankai T, Jacobs DR Jr, Komachi Y. Community-based education classes for hypertension control. A 1.5-year randomized controlled trial. Hypertension. 1996;27:968–974. 10.1161/01.HYP.27.4.968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iso H, Imano H, Nakagawa Y, et al. . One-year community-based education program for hypercholesterolemia in middle-aged Japanese: a long-term outcome at 8-year follow-up. Atherosclerosis. 2002;164:195–202. 10.1016/S0021-9150(02)00064-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iso H, Shimamoto T, Naito Y, et al. . Effects of a long-term hypertension control program on stroke incidence and prevalence in a rural community in northeastern Japan. Stroke. 1998;29:1510–1518. 10.1161/01.STR.29.8.1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamagishi K, Sato S, Kitamura A, et al. . Cost-effectiveness and budget impact analyses of a long-term hypertension detection and control program for stroke prevention. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1874–1879. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283568781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato S, Iso H, Naito Y, et al. . Plasma fibrinogen and its correlates in urban Japanese men. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:521–527. 10.1093/ije/25.3.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sato S, Nakamura M, Iida M, et al. . Plasma fibrinogen and coronary heart disease in urban Japanese. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:420–423. 10.1093/aje/152.5.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato S, Iso H, Noda H, et al. . Plasma fibrinogen concentrations and risk of stroke and its subtypes among Japanese men and women. Stroke. 2006;37:2488–2492. 10.1161/01.STR.0000242473.13884.8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohira T, Iso H, Satoh S, et al. . Prospective study of depressive symptoms and risk of stroke among Japanese. Stroke. 2001;32:903–908. 10.1161/01.STR.32.4.903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iso H, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, et al. . Prospective study of fat and protein intake and risk of intraparenchymal hemorrhage in women. Circulation. 2001;103:856–863. 10.1161/01.CIR.103.6.856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iso H, Sato S, Umemura U, et al. . Linoleic acid, other fatty acids, and the risk of stroke. Stroke. 2002;33:2086–2093. 10.1161/01.STR.0000023890.25066.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chei CL, Yamagishi K, Kitamura A, et al. . Serum fatty acid and risk of coronary heart disease: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Circ J. 2018;82:3013–3020. 10.1253/circj.CJ-18-0240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohira T, Iso H, Imano H, et al. . Prospective study of major and minor ST-T abnormalities and risk of stroke among Japanese. Stroke. 2003;34:e250–e253. 10.1161/01.STR.0000103742.83117.FB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sawai T, Imano H, Muraki I, et al. . Changes in ischaemic ECG abnormalities and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease. Heart Asia. 2017;9:36–43. 10.1136/heartasia-2016-010846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iso H, Moriyama Y, Sato S, et al. . Serum total homocysteine concentrations and risk of stroke and its subtypes in Japanese. Circulation. 2004;109:2766–2772. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131942.77635.2D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitamura A, Iso H, Imano H, et al. . Carotid intima-media thickness and plaque characteristics as a risk factor for stroke in Japanese elderly men. Stroke. 2004;35:2788–2794. 10.1161/01.STR.0000147723.52033.9e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iso H, Sato S, Kitamura A, et al. . Metabolic syndrome and the risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke among Japanese men and women. Stroke. 2007;38:1744–1751. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.469072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chei CL, Yamagishi K, Tanigawa T, et al. . Metabolic syndrome and the risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke among middle-aged Japanese. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:1887–1894. 10.1291/hypres.31.1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imano H, Sato S, Kitamura A, et al. . Leukocyte count is an independent predictor for risk of acute myocardial infarction in middle-aged Japanese men. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:147–152. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimizu Y, Imano H, Ohira T, et al. . γ-Glutamyltranspeptidase and incident stroke among Japanese men and women: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Stroke. 2010;41:385–388. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.569061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimizu Y, Imano H, Ohira T, et al. . Alkaline phosphatase and risk of stroke among Japanese: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:1046–1055. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chei CL, Yamagishi K, Kitamura A, et al. . C-reactive protein levels and risk of stroke and its subtype in Japanese: The Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Atherosclerosis. 2011;217:187–193. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimizu Y, Maeda K, Imano H, et al. . Chronic kidney disease and drinking status in relation to risks of stroke and its subtypes: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Stroke. 2011;42:2531–2537. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.600759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagayoshi M, Tanigawa T, Yamagishi K, et al. . Self-reported snoring frequency and incidence of cardiovascular disease: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). J Epidemiol. 2012;22:295–301. 10.2188/jea.JE20110109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Imano H, Iso H, Kiyama M, et al. . Non-fasting blood glucose and risk of incident coronary heart disease in middle-aged general population: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Prev Med. 2012;55:603–607. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imano H, Iso H, Kitamura A, et al. . Nonfasting Glucose and Incident Stroke and Its Types—The Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Circ J. 2018;82:1598–1604. 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chei CL, Yamagishi K, Kitamura A, et al. . High-density lipoprotein subclasses and risk of stroke and its subtypes in Japanese population: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study. Stroke. 2013;44:327–333. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.674812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saito I, Yamagishi K, Chei CL, et al. . Total and high molecular weight adiponectin levels and risk of cardiovascular disease in individuals with high blood glucose levels. Atherosclerosis. 2013;229:222–227. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cui R, Yamagishi K, Imano H, et al. . Relationship between the ankle-brachial index and the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: the circulatory risk in communities study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2014;21:1283–1289. 10.5551/jat.24133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shimizu Y, Imano H, Ohira T, et al. . Adult height and body mass index in relation to risk of total stroke and its subtypes: the circulatory risk in communities study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:667–674. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsuneoka H, Takagi M, Murakoshi N, et al. . Long-Term Prognosis of Brugada-Type ECG and ECG With Atypical ST-Segment Elevation in the Right Precordial Leads Over 20 Years: Results From the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kitamura A, Yamagishi K, Imano H, et al. . Impact of hypertension and subclinical organ damage on the incidence of cardiovascular disease among Japanese residents at the population and individual levels—The Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Circ J. 2017;81:1022–1028. 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iso H, Kitamura A, Shimamoto T, et al. . Alcohol intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease in middle-aged Japanese men. Stroke. 1995;26:767–773. 10.1161/01.STR.26.5.767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kitamura A, Iso H, Sankai T, et al. . Alcohol intake and premature coronary heart disease in urban Japanese men. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:59–65. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sankai T, Iso H, Shimamoto T, et al. . Prospective study on alcohol intake and risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage among Japanese men and women. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:386–389. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb04628.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamagishi K, Iso H, Kitamura A, et al. . Smoking raises the risk of total and ischemic strokes in hypertensive men. Hypertens Res. 2003;26:209–217. 10.1291/hypres.26.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iso H, Imano H, Kitamura A, et al. . Type 2 diabetes and risk of non-embolic ischaemic stroke in Japanese men and women. Diabetologia. 2004;47:2137–2144. 10.1007/s00125-004-1587-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hayama-Terada M, Muraki I, Imano H, et al. . Diabetes trend and impact on risk of cardiovascular disease in middle-aged Japanese people—The CIRCS Study. Circ J. 2016;80:2343–2348. 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Imano H, Kitamura A, Sato S, et al. . Trends for blood pressure and its contribution to stroke incidence in the middle-aged Japanese population: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Stroke. 2009;40:1571–1577. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.538629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Imano H, Noda H, Kitamura A, et al. . Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and risk of coronary heart disease among Japanese men and women: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Prev Med. 2011;52:381–386. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kitamura A, Noda H, Nakamura M, et al. . Association between non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and the incidence of coronary heart disease among Japanese: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). J Atheroscler Thromb. 2011;18:454–463. 10.5551/jat.7237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kitamura A, Iso H, Naito Y, et al. . High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and premature coronary heart disease in urban Japanese men. Circulation. 1994;89:2533–2539. 10.1161/01.CIR.89.6.2533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moriyama Y, Okamura T, Inazu A, et al. . A low prevalence of coronary heart disease among subjects with increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, including those with plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein deficiency. Prev Med. 1998;27:659–667. 10.1006/pmed.1998.0340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iso H, Naito Y, Sato S, et al. . Serum triglycerides and risk of coronary heart disease among Japanese men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:490–499. 10.1093/aje/153.5.490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Iso H, Imano H, Yamagishi K, et al. . Fasting and non-fasting triglycerides and risk of ischemic cardiovascular disease in Japanese men and women: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Atherosclerosis. 2014;237:361–368. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ikeda A, Yamagishi K, Tanigawa T, et al. . Cigarette smoking and risk of disabling dementia in a Japanese rural community: a nested case-control study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:324–331. 10.1159/000118377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chei CL, Yamagishi K, Ikeda A, et al. . C-reactive protein levels and risk of disabling dementia with and without stroke in Japanese: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Atherosclerosis. 2014;236:438–443. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamagishi K, Ikeda A, Moriyama Y, et al. . Serum coenzyme Q10 and risk of disabling dementia: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Atherosclerosis. 2014;237:400–403. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamagishi K, Ikeda A, Chei CL, et al. . Serum α-linolenic and other ω-3 fatty acids, and risk of disabling dementia: Community-based nested case-control study. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:793–797. 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jinnouchi H, Kitamura A, Yamagishi K, et al. . Retinal vascular changes and prospective risk of disabling dementia: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24:687–695. 10.5551/jat.37291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iso H, Sato S, Folsom AR, et al. . Serum fatty acids and fish intake in rural Japanese, urban Japanese, Japanese American and Caucasian American men. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18:374–381. 10.1093/ije/18.2.374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iso H, Koike KA, Folsom AR, et al. . Lipoprotein(a) and its correlates in Japanese and U.S. population samples. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:324–330. 10.1016/S1047-2797(96)00050-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iso H, Harada S, Shimamoto T, et al. . Polymorphism of the apolipoprotein B gene and blood lipid concentrations in Japanese and Caucasian population samples. Atherosclerosis. 1996;126:233–241. 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05912-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Iso H, Folsom AR, Wu KK, et al. . Hemostatic variables in Japanese and Caucasian men. Tissue plasminogen activator, antithrombin III, and protein C and their relations to coronary risk factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:41–46. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iso H, Folsom AR, Koike KA, et al. . Antigens of tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1: correlates in nonsmoking Japanese and Caucasian men and women. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70:475–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iso H, Folsom AR, Sato S, et al. . Plasma fibrinogen and its correlates in Japanese and US population samples. Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:783–790. 10.1161/01.ATV.13.6.783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iso H, Folsom AR, Winkelmann JC, et al. . Polymorphisms of the beta fibrinogen gene and plasma fibrinogen concentration in Caucasian and Japanese population samples. Thromb Haemost. 1995;73:106–111. 10.1055/s-0038-1653733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lindberg G, Iso H, Råstam L, Lundblad A, Folsom AR. Serum sialic acid and its correlates in community samples from Akita, Japan and Minneapolis, USA. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:58–63. 10.1093/ije/26.1.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yamagishi K, Ohira T, Nakano H, et al. . Cross-cultural comparison of the sleep-disordered breathing prevalence among Americans and Japanese. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:379–384. 10.1183/09031936.00118609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Prospective Studies Collaboration Cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure, and stroke: 13,000 strokes in 450,000 people in 45 prospective cohorts. Lancet. 1995;346:1647–1653. 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92836-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration: analysis of individual data on lipid, inflammatory and other markers in over 1.1 million participants in 104 prospective studies of cardiovascular diseases. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22:839–869. 10.1007/s10654-007-9165-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matsushita K, Ballew SH, Astor BC, et al. . Cohort profile: the chronic kidney disease prognosis consortium. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1660–1668. 10.1093/ije/dys173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ueshima H. [A multi-center cohort study for clarifying risk factors on atherosclerosis in Japan (JALS)]. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2005;42:54–57 (in Japanese). 10.3143/geriatrics.42.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Japan Arteriosclerosis Longitudinal Study (JALS) Group Japan Arteriosclerosis Longitudinal Study-Existing Cohorts Combine (JALS-ECC): rationale, design, and population characteristics. Circ J. 2008;72:1563–1568. 10.1253/circj.CJ-07-1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Murakami Y. Meta-analyses using individual participant data from cardiovascular cohort studies in Japan: current status and future directions. J Epidemiol. 2014;24:96–101. 10.2188/jea.JE20130177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Iso H, Shimamoto T. Trends, risk factors and prevention of leading adult diseases: Cerebrovascular disease. In: Ohno Y, editor. TEXT Public Health and Preventive Medicine. Tokyo: Nanzando; 1996:297–318. [Google Scholar]

- 87.World Health Organization. Community-based efforts to reduce blood pressure and stroke in Japan [homepage on the Internet]; c2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/features/2013/japan_blood_pressure/en/.