Abstract

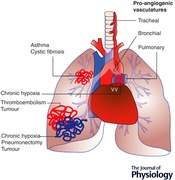

Both systemic (tracheal and bronchial) and pulmonary circulations perfuse the lung. However, documentation of angiogenesis of either is complicated by the presence of the other. Well‐documented angiogenesis of the systemic circulations have been identified in asthma, cystic fibrosis, chronic thromboembolism and primary carcinomas. Angiogenesis of the vasa vasorum, which are branches of bronchial arteries, is seen in the walls of large pulmonary vessels after a period of chronic hypoxia. Documentation of increased pulmonary capillaries has been shown in models of chronic hypoxia, after pneumonectomy and in some carcinomas. Although endothelial cell proliferation may occur as part of the repair process in several pulmonary diseases, it is separate from the unique establishment of new functional perfusing networks defined as angiogenesis. Identification of the mechanisms driving the expansion of new vascular beds in the adult needs further investigation. Yet the growth factors and molecular mechanisms of lung angiogenesis remain difficult to separate from underlying disease sequelae.

Keywords: Endothelium, Bronchial artery, Pulmonary artery

Introduction

Folkman first described angiogenesis in a carcinoma model demonstrating limited capacity for tumour growth beyond a certain size without the commensurate proliferation of a tumour vasculature (Folkman et al. 1963). These studies created intense interest in the process of neovascularization in the adult organism under pathological conditions. Although limited work had been previously performed exploring vasoproliferation, studies of the growth factors that promoted tumour angiogenesis subsequently expanded to studies of therapeutic angiogenesis in ischaemic limbs and other systemic organs. Yet studies of angiogenesis in the lung, and its role in lung disease appear to have lagged behind those in other organs perhaps given the complexity of the lung with its two different circulatory beds. Neovascularization, the process whereby new vascular networks form, is separate from endothelial cell repair processes, and has been difficult to quantify and study as a unique in vivo entity. Angiogenesis, the growth of new perfusing capillary structures from an existing vasculature, shares many of the same properties and mechanisms as both arteriogenesis and vasculogenesis. While each of these physiological phenomena involves the formation of new functional blood vessels, vasculogenesis refers to de novo blood vessel development without initial connection to an existing vascular network (Warburton et al. 2000). Vasculogenesis occurs during embryonic development and is facilitated by bone marrow‐derived stem cell populations (Ribatti et al. 2015; Gao et al. 2016). After a primary vascular plexus is formed, angiogenesis takes over as new capillaries sprout from the primary vascular structures constructed by differentiated endothelial cells. Within the adult organism, angiogenesis is the primary mechanism by which new vessels proliferate from an existing bed. However, some have described postnatal vasculogenesis (Ribatti et al. 2001; Asahara & Kawamoto, 2004) as the process whereby circulating endothelial progenitor cells or tissue‐specific progenitor cells are incorporated into both existing vasculatures and sprouting angiogenic vessels (Duong et al. 2011). Yet it is not clear whether progenitor cells are able to independently reconstitute a neovasculature in the adult organism (Chamoto et al. 2012, Hou et al. 2016; Wakabayashi et al. 2018).

In general terms, arteriogenesis is a mechanism in place to protect and secure tissue blood supply if a main artery supplying a tissue is chronically obstructed (Simons & Eichmann, 2015). In this case, collateral arteries or arterioles will proliferate, bypassing an occluded vessel thus maintaining tissue perfusion. It has been shown that unlike angiogenesis that is driven by local oxygen tension, arteriogenesis is likely driven by changes in upstream biomechanical forces and inflammatory cell mediators (Hsia, 2017).

In a complex, well‐vascularized organ like the lung, it is likely that these processes rarely occur individually but more commonly function in concert in response to pathological challenges. This review focuses on pathological settings where neovascularization occurs in the adult organism, and the challenges presented to defining this process.

General mechanisms of angiogenesis

Angiogenesis commonly occurs in response to local tissue hypoxia through both sprouting and non‐sprouting processes involving endothelial cells. Endothelial cells play the predominant role in angiogenesis because they are the main target for molecular signals for growth, proliferation and migration. At the most basic level, tissues in need of oxygen and basic nutrients secrete pro‐angiogenic molecules. Endothelial cells respond to growth factors by becoming invasive and protrude filapodia (Gerhardt et al. 2003). These tip cells lead vascular sprouts, followed by stalk cells, which proliferate to elongate the sprout (Adams & Eichmann, 2010; Geudens & Gerhardt, 2011). Tip cells can connect with neighbouring tip cells and form new vessel circuits. The most studied driver of this process is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)‐A released by hypoxic tissue, which binds to VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) expressed on endothelial cells (de Vries et al. 1992; Breier et al. 1995). Endothelial cells with high VEGFR2 activity become tip cells and instruct neighbouring cells to become stalk cells by the upregulation of Notch ligand delta‐like 4 (DLL4), which activates NOTCH1 leading to suppression of VEGFR2 in stalk cells (Jakobsson et al. 2010). Interestingly, tip cell migration was shown to respond to a VEGF‐A gradient, while proliferation responds to its concentration (Gerhardt et al. 2003). After a VEGF‐A gradient is established to guide endothelial sprouting, the local extracellular matrix is degraded by several other tissue factors to allow for endothelial cell migration (Wells et al. 2015; De Palma et al. 2017). In addition to VEGF‐A, interleukin‐8 (IL‐8), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), angiopoietins, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and numerous inflammatory cell mediators have been shown to regulate the process of endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis and have been extensively reviewed (Keeley et al. 2008; Eelen et al. 2015; De Palma et al. 2017; Todorova et al. 2017).

Less well understood is another form of neovascular expansion, intussusceptive angiogenesis, a non‐sprouting process whereby an intravascular pillar forms that spans the interior lumen of a capillary resulting in the generation of two daughter vessels (Caduff et al. 1986). Models suggest this process is highly dependent on changes in shear stress, may not require predominant endothelial cell proliferation (Mentzer & Konerding, 2014; Hsia, 2017), and may be uniquely sensitive to microenvironment growth factor concentration (Gianni‐Barrera et al. 2011; Gianni‐Barrera et al. 2014).

Endothelium

Endothelial cell responses have shown substantial heterogeneity between organ systems, vascular beds within an organ, and even cells within the same region of a single vascular bed (Aird, 2012). Endothelial cells maintain barrier function, recruit leukocytes and contribute to vasomotor tone in addition to their role in angiogenesis. The structure of endothelium lining capillaries can be continuous, fenestrated or discontinuous depending on the function of that specific vascular bed. A continuous endothelium, as in the lung, is responsible for tightly regulating permeability and transport of fluids and solutes across cell barriers. The innate properties of each circulation's ability to undergo angiogenesis are a direct representation of the endothelial cells in each vascular bed. Within the lung, examining heterogeneity between endothelial cells of the pulmonary and bronchial circulation with regard to surface receptors, proliferative capacity and bioenergetics might explain the differences between each circulation's responses to angiogenic stimuli.

Numerous studies have investigated differences in the endothelium of the pulmonary circulation where functional differences exist among cells from pulmonary arteries, arterioles and the microvasculature. Differences in leukocyte trafficking, expression of calcium channels, and cell surface markers have been observed between endothelial cells of the pulmonary vasculature (Stevens, 2011; Uhlig et al. 2014; Townsley, 2018). However, less is known about phenotypic differences between pulmonary and bronchial endothelium. In the few reported studies, differences exist between pulmonary and bronchial endothelial cells (Moldobaeva & Wagner, 2003; Eldridge et al. 2016), as well as aortic endothelial cells (Moldobaeva et al. 2008) with regard to in vitro proliferative capacity and surface marker expression. Whether angiogenic capacity is predicted by anatomical, physiological or ontological properties of each vascular bed is unstudied. Recent work exploring general mechanisms of angiogenesis has focused on bioenergetics of endothelium (Potente & Carmeliet, 2017). Endothelial cells are highly glycolytic and when endothelial cells switch from a quiescent state to a pro‐angiogenic state, glycolysis is further accelerated (De Bock et al. 2013). Pro‐angiogenic molecules have been shown to increase glucose uptake and drive glucose activators. Although energetic yield is low, glycolysis can produce ATP faster and it makes endothelial cells more hypoxia resistant. Interestingly, glycolysis differs in endothelial cell subtypes with arterial endothelial cells more oxidative and microvascular endothelial cells more glycolytic and proliferative (Krutzfeldt et al. 1990; Parra‐Bonilla et al. 2010; De Bock et al. 2013). Whether the bioenergetics of pulmonary compared with bronchial endothelium can explain angiogenic propensity requires investigation.

Within a subset of pulmonary vascular endothelial cells, Alvarez and colleagues demonstrated a population of microvascular endothelial cells with high proliferative capacity (Alvarez et al. 2008) These tissue resident progenitor cells (CD31+, CD144+, eNOS+, vWf+, CD34+, CD309+) were capable of forming vascular matrices in vitro. This population is distinct from circulating bone‐marrow derived progenitor cells (CD34+ CD133+) shown to be elevated in subjects with pulmonary arterial hypertension (Asosingh et al. 2008) and involved in changes in the pulmonary vascular wall after extended periods of hypoxia (Davie et al. 2004). Yet the importance and function of tissue resident cells appear to be more related to endothelial repair processes than angiogenesis in the adult. The Tatsumi laboratory has shown in lung injury models of chronic hypoxia (Nishimura et al. 2015) and LPS (Kawasaki et al. 2015), tissue‐resident cells increase, are highly proliferative, form matrices in vitro and appear to contribute to pulmonary vascular repair in vivo. Whether circulating or tissue‐resident progenitors actually engraft (Ohle et al. 2012; Sekine et al. 2016) is an exciting area of research with therapeutic implications for reversal of injury. However, more basic information is needed to support a role for tissue resident progenitor cells in pulmonary angiogenesis.

Challenges to the measurement of lung angiogenesis

The lung provides unique growth conditions for angiogenesis because of its oxygen‐rich environment and unique, ever‐moving matrix with dual circulations. Since the entire cardiac output flows through the pulmonary circulation, capillary recruitment and changes in blood flow provide rapid adaptations for the need for increased perfusion. The pulmonary circulation, a high flow low‐pressure circuit, is responsible for efficient gas exchange and is sensitive to any mechanical and chemical changes. The systemic circulation to the lung, the tracheal and bronchial vasculatures, exposed to systemic arterial pressures, constitutes less than 2% of the cardiac output normally (Onorato et al. 1994). The bronchial circulation provides nutrient blood flow to conducting airways to the level of the terminal bronchioles as well as to nerves, lymph nodes, visceral pleura and the walls of large pulmonary vessels, and drains into the pulmonary arteries and veins (Butler, 1992). Because phenotypic differences exist in the two vasculatures, it cannot be assumed that each has similar angiogenic potential. Herein lie several substantial challenges to quantify and measure angiogenesis in the lung. (1) Confirming the growth of bronchial endothelial networks relative to the pulmonary vasculature requires discrimination and quantification of vessels based on labelling, location and perfusion patterns. While it is conventional to label endothelium with anti‐CD31, anti‐CD34, or anti‐von Willebrand factor, both bronchial and pulmonary endothelial subtypes can take up these labels equivalently as do native compared with angiogenic vessels. Quantification based on these labels alone will lead to erroneous conclusions. These markers, also used for cell sorting or quantification using flow cytometry, are subject to similar criticism. Additionally, other cell types express these cell surface markers adding to errors of quantification. (Piali et al. 1995; Sadler, 1998; Nielsen & McNagny, 2008; Privratsky et al. 2010). (2) Furthermore, morphometric studies of vessels within the lung require strict adherence to fixation protocols at uniform lung volumes and/or pressures to ensure that vessel densities are determined over equivalent areas (Hsia et al. 2010; Mitzner & Ochs, 2018). Lung consolidation due to disease processes can complicate the evaluation of vessel density/unit area. (3) In vitro models estimating proliferation, migration and tube formation require phenotypically relevant endothelial subtypes but do not confirm in vivo perfusing networks under physiological pressures. (4) Angiogenesis (i.e. the growth of new perfusing vascular circuits) is not equivalent to vascular remodelling where endothelial cell proliferation may be part of endothelial repair processes albeit influenced by common growth factors. (5) Capillary growth characteristics measured in implanted artificial gels or matrices lack normal ventilatory expansion, which may play a significant role in vascular expansion (Mammoto et al. 2016; Hsia, 2017). (6) In vivo estimates of blood flow through each circuit can be assessed independently using radiographic techniques with contrast. The time course of changes during matched steady‐state conditions may provide information of increased vascularity. In animal models, multi‐colour labelled microspheres allow for postmortem analysis of the extent and magnitude of perfusion distribution of each vasculature (Bernard et al. 1996; Eldridge et al. 2016 ). Yet analysis can be complicated by vasodilation and increased blood flow, which are not equivalent to neovascularization. This is especially true for the pulmonary vascular bed where vascular recruitment constitutes an important mechanism to accommodate increased blood flow. Each of these six factors contributes to current experimental challenges and complications in interpretation of assessing true angiogenesis in the lung.

Angiogenesis in lung pathologies

Asthma

Perhaps the most clearly documented is the neovascularization of both tracheal and bronchial arteries that occurs in hyperreactive airways disease in patients with asthma as well as several animal models of airways diseases. Kuwano et al. (1993) demonstrated in postmortem lungs an increase in airway vascularity in asthmatic subjects compared to normal controls as well as subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Supporting this work using bronchoscopic biopsies from major airways of normal control subjects and patients with mild asthma, an increase in vessel density as well as in vessel size was demonstrated (Li & Wilson, 1997). In bronchial biopsy materials, Barbato et al. (2006) showed that atopic children without asthma showed increased airway vascularity as well as those with asthma compared to normal controls. Providing an in vivo assessment, Tanaka and colleagues, used a high‐magnification bronchovideoscope and showed significantly increased vessel numbers in the lower trachea of asthmatic subjects compared to normal controls. This increased number was not altered by the use of inhaled corticosteroids (Tanaka et al. 2003). To explore the mechanisms responsible for this neovascularization, biopsy material and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were shown to express increased VEGF, its receptors and angiopoietin‐1 in asthmatic subjects relative to controls, suggesting their potential importance in the process of airway neovascularization (Feltis et al. 2006).

Numerous animal models have been developed to study airway angiogenesis. The McDonald laboratory, in a series of studies, has demonstrated tracheal angiogenesis after Mycoplasma pulmonis infection in mice and rats (McDonald, 2001). Overall, results demonstrated that vascular remodelling and neovascularization were largely due to angiopoetins and Tie signaling (Kim et al. 2016). Unfortunately, due to the cartilaginous structure of the trachea and its lack of effect on overall airway resistance, the effect of altered vascularity on airway function was obscured. In rat models of repeated exposure to allergen, increased airway vascularity has been demonstrated and was associated with enhanced reactivity (Karmouty‐Quintana et al. 2012; Wagner et al. 2015). Several investigators have attempted similar models of allergen‐induced reactivity in mice. However, examination of changes in airway vascularity has been equivocal since mice lack a sub‐carinal bronchial circulation (Mitzner et al. 2000). Histological examination of parenchymal units, using endothelial markers such as CD31 or vWf did not discriminate between bronchial and pulmonary vessels. Hence, evaluation of angiogenesis has been imprecise in these models (Yao et al. 2015; Asosingh et al. 2016).

COPD

Tanaka and colleagues, using a high‐magnification bronchovideoscope showed no difference in vessel numbers in the lower trachea of patients with COPD compared to normal controls (Tanaka et al. 2003). Recently, Fathy et al. (2016) showed, using image‐enhanced bronchoscopic images, that although there was increased erythema in subjects with COPD, assessment of biopsy samples suggested a decrease in vessel density. They speculated that vasodilatation contributed to the enhanced erythema and not angiogenesis. Results are consistent with the earlier morphometric work of Kuwano showing no difference between vessel numbers in patients with COPD compared to healthy controls (Kuwano et al. 1993).

Cystic fibrosis

Haemorrhage and haemoptysis are frequent complications of patients with cystic fibrosis requiring bead embolization of small bronchial arteries. Based on information from the interventional radiology literature, bronchial arteries undergo both hypertrophy and angiogenesis, presumably the result of chronic inflammation (Holsclaw et al. 1970; Hurt & Simmonds, 2012). Most cystic fibrosis patients have recurrent haemoptysis because embolized vessels open back up, but most times the bleeding region gets new collateral supplies from proximal bronchial or other systemic arteries (subclavian, lateral thoracic, thoracoacromial arteries). Epithelial cells from cystic fibrosis patients have been shown to express several angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF‐A, VEGF‐C, bFGF, and PLGF. As might be expected, conditioned medium from these cells cause in vitro endothelial cell proliferation, migration and sprouting (Verhaeghe et al. 2007).

Fibrosis

In 1963 Turner‐Warwick observed an extensive bronchial vascular network with increased bronchial‐pulmonary anastomoses and an unchanged pulmonary vasculature in 12 of 16 lungs from patients with diffuse pulmonary fibrosis (Turner‐Warwick, 1963). In support of this observation, bronchial angiogenesis was demonstrated in a bleomycin rat model, which showed both increased vascularity of peribronchial regions and some distortion of alveolar capillaries (Peao et al. 1994). Thus, there has been a clear demonstration of bronchial vascular angiogenesis in fibrosis. Ackermann and colleagues have demonstrated in corrosion casts of the pulmonary vasculature examples of both sprouting and intussusceptive angiogenesis in a bleomycin mouse model (Ackermann et al. 2017). Growth factors, angiostatic factors, and endothelial cell apoptosis have been measured in the lung parenchyma of fibrotic lungs indicative of vascular remodelling (Mammoto et al. 2016; Bultmann‐Mellin et al. 2017). Some investigators have used the term deregulated angiogenesis to describe this pathological remodelling (Mammoto et al. 2016). Yet whether these parenchymal changes in the pulmonary circulation result in true angiogenesis with new functionally perfusing vessels requires further in vivo study.

Pulmonary chronic thromboembolism

Interestingly, Turner‐Warwick's careful anatomical studies comparing the circulations of diseased lungs with normal human lungs demonstrated that no pulmonary precapillary bronchial to pulmonary anastomoses existed in normal healthy lungs (Turner‐Warwick, 1963). Only under conditions of diseased lung do precapillary bronchial to pulmonary vessels proliferate. These changes are most evident under conditions where a pulmonary artery is obstructed. Massive bronchial arterial arteriogenesis and angiogenesis have been demonstrated in humans (Karsner & Ghoreyeb, 1913; Endrys et al. 1997; Remy‐Jardin et al. 2004), sheep (Charan & Carvalho, 1997), pigs (Fadel et al. 1998), dogs (Michel et al. 1990), rats (Weibel, 1960) and mice (Mitzner et al. 2000). Recent work suggests that inflammatory mediators released by myeloid‐derived cells and tissue ischaemia lead to recruitment, proliferation and growth of bronchial vessels (Moldobaeva et al. 2011). Since tissue hypoxia is not present in this ventilating lung situation, VEGF and hypoxia‐inducible factor (HIF)‐related factors appear not to play a significant role in angiogenesis (Srisuma et al. 2003).

Chronic hypoxia

Studies of angiogenesis in the lung in models of chronic hypoxia have documented changes to both the bronchial and pulmonary vascular beds. Davie demonstrated in histological samples obtained from calves raised at altitude an increase in the vascularity of the vasa vasorum in the pulmonary arterial walls (Davie et al. 2004). These vessels originate from branches of the bronchial artery. Results suggested that bone marrow‐derived progenitor cells were incorporated into the newly remodelled vasculature. Furthermore, adventitial fibroblasts, through endothelin‐1 secretion, demonstrated pro‐angiogenic properties (Davie et al. 2006).

One of the few instances of pulmonary capillary angiogenesis was shown by the McLoughlin laboratory, which studied rats exposed to hypoxia (10% oxygen) for 2 weeks. Using stereoscopic techniques, these investigators showed an increase in total pulmonary vessel length, vascular volume, endothelial cell surface area and number of endothelial cells (Howell et al. 2003). This work was somewhat controversial since most studies have demonstrated increased pulmonary resistance with expectations of vascular pruning (Meyrick & Reid, 1983), the opposite of what McLoughlin and colleagues reported. Yet others have confirmed hypoxia‐induced pulmonary angiogenesis (Beppu et al. 2004; Nishimura et al. 2015) and demonstrated that Rho kinase mediates hypoxia‐induced capillary angiogenesis in the chronically hypoxic rat model (Hyvelin et al. 2005).

Lung pneumonectomy

Another well‐documented instance of pulmonary vascular angiogenesis occurs after pneumonectomy. After removal of a lung lobe there is significant lung remodelling that takes place whereby mechanical stress induced by changes in air and blood flow provide the major stimulus for alveolar capillary growth (Hsia et al. 1994). An upregulation of pro‐angiogenic molecules over the course of weeks leads to the formation of new capillaries from existing vessels through the process of intussusceptive angiogenesis (Hsia et al. 1994; Hsia, 2017). Incorporation of blood‐borne CD34+ endothelial progenitor cells also contributes to neovascularization (Chamoto et al. 2012).

Cancer

Tumours in the lung are angiogenic, non‐angiogenic, or a combination of both, and it remains to be determined which circulation is proliferating under such conditions. Several studies utilizing contrast enhanced computed tomography scanning have implicated major roles of both the pulmonary and bronchial circulations in tumour perfusion. Since these studies were performed in patients, perfusion data were limited to a single time point, without subsequent experiments examining how each vascular bed changed with tumour size (Yuan et al. 2012; Nguyen‐Kim et al. 2015). Further examination of the angiogenic potential of the pulmonary and bronchial circulation independently could provide valuable information for novel therapies and increased drug specificity by targeting one circulation directly. Yuan and colleagues outlined a detailed method for contrast enhanced CT scanning to quantify tumour perfusion. They concluded that the bronchial circulation was dominant and the tumour circulation was dependent on tumour size (Yuan et al. 2012). Complimenting this finding, Nguyen‐Kim et al. (2015), utilizing similar methods, confirmed that tumour perfusion was correlated with tumour size as well as histological subtype. While these studies advanced imaging protocols for bronchial perfusion in patients and provided information on potential vascular relationships with tumour size, the number of scans or surgical interventions was limited. Using contrast enhanced CT of nude rats after implant of non small‐cell lung cancer, only bronchial perfusion was increased to the growing lung tumour. Furthermore, ablation of the bronchial artery after the initiation of tumour growth resulted in significant reduction in tumour volumes at 4 weeks post‐ablation (Eldridge et al. 2016).

Pulmonary arterial hypertension

Although several studies have referred to the endothelial proliferation observed in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) as angiogenesis, this process is more commonly seen as vascular remodelling and not strictly fitting the definition of establishing new vascular networks. However, in patients with PAH, new expanded bronchial‐pulmonary anastomoses were observed (Galambos et al. 2016). This process was shown to be similar to that described originally by Turner‐Warwick (1963).

Lymphangiogenesis

Lymphatic endothelium contributes to an additional vascular network in the lung performing an essential regulatory mechanism to promote fluid homeostasis and immune cell transit. However, the mechanisms that regulate lymphangiogenesis to enhance fluid clearance in lung pathologies are not well understood. Limited work demonstrates that bacteria‐induced angiogenesis in the mouse trachea predicts subsequent lymphangiogenesis (Baluk et al. 2005). In solid tumours, both angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis contribute to tumour progression and metastasis (Lee et al. 2015). The parallel process of blood vascular endothelial proliferation coupled to lymphatic endothelial network proliferation appears to be a consistent observation throughout the body (Detoraki et al. 2010; Sweat et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2015). Angiogenic blood vessels are well described as being hyperpermeable, and in such local environments, increased interstitial protein and fluid clearance would be required. However, lymphangiogenesis in the lung, despite documented pathological angiogenesis, has not been extensively studied. Studies suggest that abnormal lymphangiogenesis may play a role in the remodelling process seen in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (El‐Chemaly et al. 2009).

Conclusion

Angiogenesis has been shown to occur in several inflammatory conditions in the lung leading to proliferation of the bronchial vasculature with the growth of new capillary networks as well as larger bronchial‐to‐pulmonary anastomotic connections. However, it is unclear whether the angiogenesis is essential or whether it is merely a fellow traveller due to persistent inflammatory sequelae. Given the caveats to interpretation of current methodologies, it is important not to be too quick to use the term angiogenesis, which implies a functional network.

Additional information

Competeing interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Author contributions

The authors contributed equally to the writing of this manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

The authors are currently not funded.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the resources of the Johns Hopkins Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine.

Biographies

Lindsey Eldridge is a lung physiologist with experience in endothelial and stem cell biology, and angiogenesis. She received her doctoral degree from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health where her dissertation focused on bronchial artery angiogenesis in lung adenocarcinomas. Currently, she is a postdoctoral fellow at Medimmune where her work is focused on induced pluripotent stem cells and lung regeneration in COPD.

Elizabeth M. Wagner is Professor of Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. She has focused her work on the control of the bronchial circulation in lung disease models. In recent years, she has concentrated on the mechanisms of angiogenesis in the lung during chronic ischaemia, antigen‐induced inflammation and tumour growth.

Edited by: Larissa Shimoda & Harold Schultz

References

- Ackermann M, Kim YO, Wagner WL, Schuppan D, Valenzuela CD, Mentzer SJ, Kreuz S, Stiller D, Wollin L & Konerding MA (2017). Effects of nintedanib on the microvascular architecture in a lung fibrosis model. Angiogenesis 20, 359–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RH & Eichmann A (2010). Axon guidance molecules in vascular patterning. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2, a001875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aird WC ( 2012). Endothelial cell heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2, a006429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez DF, Huang L, King JA, ElZarrad MK, Yoder MC & Stevens T (2008). Lung microvascular endothelium is enriched with progenitor cells that exhibit vasculogenic capacity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294, L419–L430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T & Kawamoto A (2004). Endothelial progenitor cells for postnatal vasculogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287, C572–C579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asosingh K, Aldred MA, Vasanji A, Drazba J, Sharp J, Farver C, Comhair SA, Xu W, Licina L, Huang L, Anand‐Apte B, Yoder MC, Tuder RM & Erzurum SC (2008). Circulating angiogenic precursors in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Pathol 172, 615–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asosingh K, Vasanji A, Tipton A, Queisser K, Wanner N, Janocha A, Grandon D, Anand‐Apte B, Rothenberg ME, Dweik R & Erzurum SC (2016). Eotaxin‐rich proangiogenic hematopoietic progenitor cells and CCR3+ endothelium in the atopic asthmatic response. J Immunol 196, 2377–2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluk P, Tammela T, Ator E, Lyubynska N, Achen MG, Hicklin DJ, Jeltsch M, Petrova TV, Pytowski B, Stacker SA, Yla‐Herttuala S, Jackson DG, Alitalo K & McDonald DM (2005). Pathogenesis of persistent lymphatic vessel hyperplasia in chronic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest 115, 247–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbato A, Turato G, Baraldo S, Bazzan E, Calabrese F, Panizzolo C, Zanin ME, Zuin R, Maestrelli P, Fabbri LM & Saetta M (2006). Epithelial damage and angiogenesis in the airways of children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174, 975–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beppu H, Ichinose F, Kawai N, Jones RC, Yu PB, Zapol WM, Miyazono K, Li E & Bloch KD (2004). BMPR‐II heterozygous mice have mild pulmonary hypertension and an impaired pulmonary vascular remodeling response to prolonged hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 287, L1241–L1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard SL, Glenny RW, Polissar NL & Luchtel DL (1996). Distribution of pulmonary and bronchial blood supply to airways measured by fluorescent microspheres. J Appl Physiol 80, 430–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier G, Clauss M & Risau W (1995). Coordinate expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor‐1 (flt‐1) and its ligand suggests a paracrine regulation of murine vascular development. Dev Dyn 204, 228–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultmann‐Mellin I, Dinger K, Debuschewitz C, Loewe KMA, Melcher Y, Plum MTW, Appel S, Rappl G, Willenborg S, Schauss AC, Jungst C, Kruger M, Dressler S, Nakamura T, Wempe F, Alejandre Alcazar MA & Sterner‐Kock A (2017). Role of LTBP4 in alveolarization, angiogenesis, and fibrosis in lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 313, L687–L698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. (ed.) (1992). The Bronchial Circulation. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York. [Google Scholar]

- Caduff JH, Fischer LC & Burri PH (1986). Scanning electron microscope study of the developing microvasculature in the postnatal rat lung. Anat Rec 216, 154–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamoto K, Gibney BC, Lee GS, Lin M, Collings‐Simpson D, Voswinckel R, Konerding MA, Tsuda A & Mentzer SJ (2012). CD34+ progenitor to endothelial cell transition in post‐pneumonectomy angiogenesis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 46, 283–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charan NB & Carvalho P (1997). Angiogenesis in bronchial circulatory system after unilateral pulmonary artery obstruction. J Appl Physiol 82, 284–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie NJ, Crossno JT Jr, Frid MG, Hofmeister SE, Reeves JT, Hyde DM, Carpenter TC, Brunetti JA, McNiece IK & Stenmark KR (2004). Hypoxia‐induced pulmonary artery adventitial remodeling and neovascularization: contribution of progenitor cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286, L668–L678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie NJ, Gerasimovskaya EV, Hofmeister SE, Richman AP, Jones PL, Reeves JT & Stenmark KR (2006). Pulmonary artery adventitial fibroblasts cooperate with vasa vasorum endothelial cells to regulate vasa vasorum neovascularization: a process mediated by hypoxia and endothelin‐1. Am J Pathol 168, 1793–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bock K, Georgiadou M, Schoors S, Kuchnio A, Wong BW, Cantelmo AR, Quaegebeur A, Ghesquiere B, Cauwenberghs S, Eelen G, Phng LK, Betz I, Tembuyser B, Brepoels K, Welti J, Geudens I, Segura I, Cruys B, Bifari F, Decimo I, Blanco R, Wyns S, Vangindertael J, Rocha S, Collins RT, Munck S, Daelemans D, Imamura H, Devlieger R, Rider M, Van Veldhoven PP, Schuit F, Bartrons R, Hofkens J, Fraisl P, Telang S, Deberardinis RJ, Schoonjans L, Vinckier S, Chesney J, Gerhardt H, Dewerchin M & Carmeliet P (2013). Role of PFKFB3‐driven glycolysis in vessel sprouting. Cell 154, 651–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma M, Biziato D & Petrova TV (2017). Microenvironmental regulation of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 17, 457–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detoraki A, Granata F, Staibano S, Rossi FW, Marone G & Genovese A (2010). Angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in bronchial asthma. Allergy 65, 946–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries C, Escobedo JA, Ueno H, Houck K, Ferrara N & Williams LT (1992). The fms‐like tyrosine kinase, a receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Science 255, 989–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong HT, Erzurum SC & Asosingh K (2011). Pro‐angiogenic hematopoietic progenitor cells and endothelial colony‐forming cells in pathological angiogenesis of bronchial and pulmonary circulation. Angiogenesis 14, 411–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eelen G, de Zeeuw P, Simons M & Carmeliet P (2015). Endothelial cell metabolism in normal and diseased vasculature. Circ Res 116, 1231–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El‐Chemaly S, Malide D, Zudaire E, Ikeda Y, Weinberg BA, Pacheco‐Rodriguez G, Rosas IO, Aparicio M, Ren P, MacDonald SD, Wu HP, Nathan SD, Cuttitta F, McCoy JP, Gochuico BR & Moss J (2009). Abnormal lymphangiogenesis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with insights into cellular and molecular mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 3958–3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge L, Moldobaeva A, Zhong Q, Jenkins J, Snyder M, Brown RH, Mitzner W & Wagner EM (2016). Bronchial artery angiogenesis drives lung tumor growth. Cancer Res 76, 5962–5969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endrys J, Hayat N & Cherian G (1997). Comparison of bronchopulmonary collaterals and collateral blood flow in patients with chronic thromboembolic and primary pulmonary hypertension. Heart 78, 171–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel E, Mazmanian GM, Chapelier A, Baudet B, Detruit H, de Montpreville V, Libert JM, Wartski M, Herve P & Dartevelle P (1998). Lung reperfusion injury after chronic or acute unilateral pulmonary artery occlusion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 157, 1294–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathy EM, Shafiek H, Morsi TS, El Sabaa B, Elnekidy A, Elhoffy M & Atta MS (2016). Image‐enhanced bronchoscopic evaluation of bronchial mucosal microvasculature in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 11, 2447–2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltis BN, Wignarajah D, Zheng L, Ward C, Reid D, Harding R & Walters EH (2006). Increased vascular endothelial growth factor and receptors: relationship to angiogenesis in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173, 1201–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J, Long DM Jr & Becker FF (1963). Growth and metastasis of tumor in organ culture. Cancer 16, 453–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos C, Sims‐Lucas S, Abman SH & Cool CD (2016). Intrapulmonary bronchopulmonary anastomoses and plexiform lesions in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193, 574–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Cornfield DN, Stenmark KR, Thebaud B, Abman SH & Raj JU (2016). Unique aspects of the developing lung circulation: structural development and regulation of vasomotor tone. Pulm Circ 6, 407–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H, Golding M, Fruttiger M, Ruhrberg C, Lundkvist A, Abramsson A, Jeltsch M, Mitchell C, Alitalo K, Shima D & Betsholtz C (2003). VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J Cell Biol 161, 1163–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geudens I & Gerhardt H (2011). Coordinating cell behaviour during blood vessel formation. Development 138, 4569–4583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianni‐Barrera R, Bartolomeo M, Vollmar B, Djonov V & Banfi A (2014). Split for the cure: VEGF, PDGF‐BB and intussusception in therapeutic angiogenesis. Biochem Soc Trans 42, 1637–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianni‐Barrera R, Trani M, Reginato S & Banfi A (2011). To sprout or to split? VEGF, Notch and vascular morphogenesis. Biochem Soc Trans 39, 1644–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsclaw DS, Grand RJ & Shwachman H (1970). Massive hemoptysis in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 76, 829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L, Kim JJ, Woo YJ & Huang NF (2016). Stem cell‐based therapies to promote angiogenesis in ischemic cardiovascular disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310, H455–H465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell K, Preston RJ & McLoughlin P (2003). Chronic hypoxia causes angiogenesis in addition to remodelling in the adult rat pulmonary circulation. J Physiol 547, 133–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia CC (2017). Comparative analysis of the mechanical signals in lung development and compensatory growth. Cell Tissue Res 367, 687–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia CC, Herazo LF, Fryder‐Doffey F & Weibel ER (1994). Compensatory lung growth occurs in adult dogs after right pneumonectomy. J Clin Invest 94, 405–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia CC, Hyde DM, Ochs M & Weibel ER (2010). An official research policy statement of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: standards for quantitative assessment of lung structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181, 394–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt K & Simmonds NJ (2012). Cystic fibrosis: management of haemoptysis. Paediatr Respir Rev 13, 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyvelin JM, Howell K, Nichol A, Costello CM, Preston RJ & McLoughlin P (2005). Inhibition of Rho‐kinase attenuates hypoxia‐induced angiogenesis in the pulmonary circulation. Circ Res 97, 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson L, Franco CA, Bentley K, Collins RT, Ponsioen B, Aspalter IM, Rosewell I, Busse M, Thurston G, Medvinsky A, Schulte‐Merker S & Gerhardt H (2010). Endothelial cells dynamically compete for the tip cell position during angiogenic sprouting. Nat Cell Biol 12, 943–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmouty‐Quintana H, Siddiqui S, Hassan M, Tsuchiya K, Risse PA, Xicota‐Vila L, Marti‐Solano M & Martin JG (2012). Treatment with a sphingosine‐1‐phosphate analog inhibits airway remodeling following repeated allergen exposure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 302, L736–L745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsner H & Ghoreyeb A (1913). Studies in infarction: The circulation in experimental pulmonary embolism. J Exp Med 18, 507–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T, Nishiwaki T, Sekine A, Nishimura R, Suda R, Urushibara T, Suzuki T, Takayanagi S, Terada J, Sakao S & Tatsumi K (2015). Vascular repair by tissue‐resident endothelial progenitor cells in endotoxin‐induced lung injury . Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 53, 500–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley EC, Mehrad B & Strieter RM (2008). Chemokines as mediators of neovascularization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28, 1928–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Allen B, Korhonen EA, Nitschke M, Yang HW, Baluk P, Saharinen P, Alitalo K, Daly C, Thurston G & McDonald DM (2016). Opposing actions of angiopoietin‐2 on Tie2 signaling and FOXO1 activation. J Clin Invest 126, 3511–3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutzfeldt A, Spahr R, Mertens S, Siegmund B & Piper HM (1990). Metabolism of exogenous substrates by coronary endothelial cells in culture. J Mol Cell Cardiol 22, 1393–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwano K, Bosken CH, Pare PD, Bai TR, Wiggs BR & Hogg JC (1993). Small airways dimensions in asthma and in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 148, 1220–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Pandey NB & Popel AS (2015). Crosstalk between cancer cells and blood endothelial and lymphatic endothelial cells in tumour and organ microenvironment. Expert Rev Mol Med 17, e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X & Wilson JW (1997). Increased vascularity of the bronchial mucosa in mild asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156, 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammoto T, Jiang A, Jiang E & Mammoto A (2016). Role of Twist1 phosphorylation in angiogenesis and pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 55, 633–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald DM (2001). Angiogenesis and remodeling of airway vasculature in chronic inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164, S39–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentzer SJ & Konerding MA (2014). Intussusceptive angiogenesis: expansion and remodeling of microvascular networks. Angiogenesis 17, 499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyrick B & Reid L (1983). Pulmonary hypertension. Anatomic and physiologic correlates. Clin Chest Med 4, 199–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel RP, Hakim TS & Petsikas D (1990). Segmental vascular resistance in postobstructive pulmonary vasculopathy. J Appl Physiol 69, 1022–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitzner W, Lee W, Georgakopoulos D & Wagner E (2000). Angiogenesis in the mouse lung. Am J Pathol 157, 93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitzner W & Ochs M (2018). Quantitative histology seriously flawed by lack of lung volume measurement. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 58, 273–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldobaeva A, Baek A & Wagner EM (2008). MIP‐2 causes differential activation of RhoA in mouse aortic versus pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Microvasc Res 75, 53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldobaeva A, van Rooijen N & Wagner E (2011). Effects of ischemia on lung macrophages. PLoS One 6, e26716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldobaeva A & Wagner EM (2003). Angiotensin‐converting enzyme activity in ovine bronchial vasculature. J Appl Physiol 95, 2278–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen‐Kim TD, Frauenfelder T, Strobel K, Veit‐Haibach P & Huellner MW (2015). Assessment of bronchial and pulmonary blood supply in non‐small cell lung cancer subtypes using computed tomography perfusion. Invest Radiol 50, 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen JS & McNagny KM (2008). Novel functions of the CD34 family. J Cell Sci 121, 3683–3692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura R, Nishiwaki T, Kawasaki T, Sekine A, Suda R, Urushibara T, Suzuki T, Takayanagi S, Terada J, Sakao S & Tatsumi K (2015). Hypoxia‐induced proliferation of tissue‐resident endothelial progenitor cells in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308, L746–L758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohle SJ, Anandaiah A, Fabian AJ, Fine A & Kotton DN (2012). Maintenance and repair of the lung endothelium does not involve contributions from marrow‐derived endothelial precursor cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 47, 11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onorato DJ, Demirozu MC, Breitenb_cher A, Atkins ND, Chediak AD & Wanner A (1994). Airway mucosal blood flow in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 149, 1132–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra‐Bonilla G, Alvarez DF, Al‐Mehdi AB, Alexeyev M & Stevens T (2010). Critical role for lactate dehydrogenase A in aerobic glycolysis that sustains pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 299, L513–L522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peao MN, Aguas AP, de Sa CM & Grande NR (1994). Neoformation of blood vessels in association with rat lung fibrosis induced by bleomycin. Anat Rec 238, 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piali L, Hammel P, Uherek C, Bachmann F, Gisler RH, Dunon D & Imhof BA (1995). CD31/PECAM‐1 is a ligand for αvβ3 integrin involved in adhesion of leukocytes to endothelium. J Cell Biol 130, 451–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potente M & Carmeliet P (2017). The link between angiogenesis and endothelial metabolism. Annu Rev Physiol 79, 43–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privratsky JR, Newman DK & Newman PJ (2010). PECAM‐1: conflicts of interest in inflammation. Life Sci 87, 69–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remy‐Jardin M, Bouaziz N, Dumont P, Brillet PY, Bruzzi J & Remy J (2004). Bronchial and nonbronchial systemic arteries at multi‐detector row CT angiography: comparison with conventional angiography. Radiology 233, 741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Nico B & Crivellato E (2015). The development of the vascular system: a historical overview. Methods Mol Biol 1214, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Vacca A, Nico B, Roncali L & Dammacco F (2001). Postnatal vasculogenesis. Mech Dev 100, 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler JE (1998). Biochemistry and genetics of von Willebrand factor. Annu Rev Biochem 67, 395–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine A, Nishiwaki T, Nishimura R, Kawasaki T, Urushibara T, Suda R, Suzuki T, Takayanagi S, Terada J, Sakao S, Tada Y, Iwama A & Tatsumi K (2016). Prominin‐1/CD133 expression as potential tissue‐resident vascular endothelial progenitor cells in the pulmonary circulation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 310, L1130–L1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons M & Eichmann A (2015). Molecular controls of arterial morphogenesis. Circ Res 116, 1712–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srisuma S, Biswal SS, Mitzner WA, Gallagher SJ, Mai KH & Wagner EM (2003). Identification of genes promoting angiogenesis in mouse lung by transcriptional profiling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 29, 172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens T ( 2011). Functional and molecular heterogeneity of pulmonary endothelial cells. Proc Am Thorac Soc 8, 453–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweat RS, Stapor PC & Murfee WL (2012). Relationships between lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis during inflammation in rat mesentery microvascular networks. Lymphat Res Biol 10, 198–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Yamada G, Saikai T, Hashimoto M, Tanaka S, Suzuki K, Fujii M, Takahashi H & Abe S (2003). Increased airway vascularity in newly diagnosed asthma using a high‐magnification bronchovideoscope. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168, 1495–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorova D, Simoncini S, Lacroix R, Sabatier F & Dignat‐George F (2017). Extracellular vesicles in angiogenesis. Circ Res 120, 1658–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsley MI (2018). Permeability and calcium signaling in lung endothelium: unpack the box. Pulm Circ 8, 2045893217738218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner‐Warwick M ( 1963). Precapillary systemic‐pulmonary anastomoses. Thorax 18, 225–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlig S, Yang Y, Waade J, Wittenberg C, Babendreyer A & Kuebler WM (2014). Differential regulation of lung endothelial permeability in vitro and in situ. Cell Physiol Biochem 34, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghe C, Tabruyn SP, Oury C, Bours V & Griffioen AW (2007). Intrinsic pro‐angiogenic status of cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 356, 745–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EM, Jenkins J, Schmieder A, Eldridge L, Zhang Q, Moldobaeva A, Zhang H, Allen JS, Yang X, Mitzner W, Keupp J, Caruthers SD, Wickline SA & Lanza GM (2015). Angiogenesis and airway reactivity in asthmatic Brown Norway rats. Angiogenesis 18, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi T, Naito H, Suehiro JI, Lin Y, Kawaji H, Iba T, Kouno T, Ishikawa‐Kato S, Furuno M, Takara K, Muramatsu F, Weizhen J, Kidoya H, Ishihara K, Hayashizaki Y, Nishida K, Yoder MC & Takakura N (2018). CD157 marks tissue‐resident endothelial stem cells with homeostatic and regenerative properties. Cell Stem Cell 22, 384–397.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton D, Schwarz M, Tefft D, Flores‐Delgado G, Anderson KD & Cardoso WV (2000). The molecular basis of lung morphogenesis. Mech Dev 92, 55–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel ER ( 1960). Early stages in the development of collateral circulation to the lung in the rat. Circ Res 8, 353–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JM, Gaggar A & Blalock JE (2015). MMP generated matrikines. Matrix Biol 44–46, 122–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Wang W, Li Y, Huang P, Zhang Q, Wang J, Wang W, Lv Z, An Y, Qin J, Corrigan CJ, Huang K, Sun Y & Ying S (2015). IL‐25 induces airways angiogenesis and expression of multiple angiogenic factors in a murine asthma model. Respir Res 16, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X, Zhang J, Ao G, Quan C, Tian Y & Li H (2012). Lung cancer perfusion: can we measure pulmonary and bronchial circulation simultaneously? Eur Radiol 22, 1665–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]