Abstract

The disease caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum has traditionally been difficult to control, resulting in tremendous economic losses in oilseed rape (Brassica napus). Identification of important genes in the defense responses is critical for molecular breeding, an important strategy for controlling the disease. Here, we report that a B. napus mitogen-activated protein kinase gene, BnaMPK3, plays an important role in the defense against S. sclerotiorum in oilseed rape. BnaMPK3 is highly expressed in the stems, flowers and leaves, and its product is localized in the nucleus. Furthermore, BnaMPK3 is highly responsive to infection by S. sclerotiorum and treatment with jasmonic acid (JA) or the biosynthesis precursor of ethylene (ET), but not to treatment with salicylic acid (SA) or abscisic acid. Moreover, overexpression (OE) of BnaMPK3 in B. napus and Nicotiana benthamiana results in significantly enhanced resistance to S. sclerotiorum, whereas resistance is diminished in RNAi transgenic plants. After S. sclerotiorum infection, defense responses associated with ET, JA, and SA signaling are intensified in the BnaMPK3-OE plants but weakened in the BnaMPK3-RNAi plants when compared to those in the wild type plants; by contrast the level of both H2O2 accumulation and cell death exhibits a reverse pattern. The candidate gene association analyses show that the BnaMPK3-encoding BnaA06g18440D locus is a cause of variation in the resistance to S. sclerotiorum in natural B. napus population. These results suggest that BnaMPK3 is a key regulator of multiple defense responses to S. sclerotiorum, which may guide the resistance improvement of oilseed rape and related economic crops.

Keywords: Brassica napus, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, MPK3, gain-of-function, loss-of-function, association analysis

Introduction

Oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) is an agriculturally important oilseed crop that is cultivated worldwide, including North America, Europe, and South Asia. A major constraint to its productivity is sclerotinia disease caused by the pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary, resulting in a tremendous loss in seed yield: for example, 10–20% of yield losses in an average year, and up to 80% in severely infected fields in China (Oil Crop Research Institute, 1975; Wu et al., 2013). Indeed, S. sclerotiorum is a hugely destructive necrotrophic fungal plant pathogen that is capable of causing disease on at least 408 described plant species, including many economically important crops, and more than 60 names have been used to refer to diseases caused by this fungal pathogen in agriculture (Bolton et al., 2006). This necrotrophic pathogen exhibits little host specificity, and research on the molecular aspects underlying the interactions that it established with host plants have been mainly concentrated on fungal pathogenesis, which has revealed several virulence mechanisms of this pathogen, including secretion of numerous cell wall degrading enzymes, production of the non-host-selective toxin oxalic acid and secretion of effector proteins during infection (Riou et al., 1991, 1992; Cessna et al., 2000; Rollins and Dickman, 2001; Kim et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2011; Kabbage et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Guyon et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015, 2018). However, the host defense to S. sclerotiorum in the interaction, especially in the B. napus-S. sclerotiorum interaction, is less well understood.

As the first attempts to investigate the host defense to S. sclerotiorum, studies on global profiles of host gene expression in response to the pathogen indicated that genes associated with jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) signal are induced, but no salicylic acid (SA) responsive genes are identified (Zhao et al., 2007, 2009). Several latter studies showed that SA signaling, together with JA and ET signaling contribute to basal resistance against S. sclerotiorum (Guo and Stotz, 2007; Wang et al., 2012; Novakova et al., 2014). However, another study suggested that the resistance to the pathogen is not dependent on SA, and that JA signaling does not seem to play a predominant role in the resistance (Perchepied et al., 2010). Conclusions in these studies about the role of these signaling in resistance to S. sclerotiorum are contradictory. Nevertheless, these data imply that the defense responses to the pathogen involve a multiple and complicated arrange of signaling pathways.

It has been shown that mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs or MPKs) play an important role in signal transduction in response to hormones and environmental stresses (Tena et al., 2001; Zhang and Klessig, 2001; Group, 2002; Nakagami et al., 2005; Meng and Zhang, 2013). An MAPK activity is controlled by sequential activation of two protein kinases, by which an MAPK kinase kinase activates an MAPK kinase that in turn activates an MAPK (Rodriguez et al., 2010). Evidence is now accumulating that some MAPK family members have been implicated in plant defense as a component of defense signaling pathways. For example, in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), such as the bacterial flagellum-derived flg22 peptide, trigger the activation of AtMAPKs including AtMPK1, AtMPK3, AtMPK4, AtMPK6, AtMPK11, and AtMPK13 (Meng and Zhang, 2013; Nitta et al., 2014). Of these MAPKs, AtMPK4 was first described as a negative regulator of plant immunity (Petersen et al., 2000; Brodersen et al., 2006), whereas some others, such as AtMPK3, were believed to play positive roles in plant immunity based on their rapid activation by flg22 and pathogen inoculation (Zhang and Klessig, 2001). Further, the Arabidopsis thaliana mpk3 loss-of-function mutants showed significantly lower bacterial titers of Pseudomonas syringae, and in expression of genes involved in SA biosynthesis and signaling, either control or flg22-treated Atmpk3 loss-of-function mutants have no different from Atmpk4 mutants that display enhanced resistance to biotrophic pathogens Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis and P. syringae (Petersen et al., 2000; Frei dit Frey et al., 2014). However, another trial revealed no clear susceptible phenotype in the Atmpk3 mutants when spray- or infiltration-inoculated with P. syringae (Su et al., 2017).

MPK3 genes have been identified in various crop species and implicated in defense responses and other physiological processes. In tobacco, WIPK (wound-induced protein kinase), the MPK3 ortholog in Nicotiana tabacum, was found to be activated during infection with TMV (tobacco mosaic virus; Zhang and Klessig, 1998a) and treatments such as SA, ET, and jasmonate in suspension cells (Zhang and Klessig, 1997, 1998b; Kumar and Klessig, 2000; Zhang et al., 2000). In Catharanthus roseus, MeJA application resulted in the transcript accumulation of CrMPK3 (Raina et al., 2012), suggesting that the MAPK might be involved in JA-mediated defense response. In cotton, Gossypium barbadense MPK3 (GbMPK3) can be induced during multiple abiotic stress treatments including salt, cold, heat, dehydration and oxidative stress. In rice, OsMPK3 positively regulates the JA signaling pathway and plant resistance to a chewing herbivore Chilo suppressalis (Wang et al., 2013). In B. napus, however, there have been no reports to this date on the biological functions of MPK3 in the defense of B. napus against S. sclerotiorum, one of the most important pathogens of this crop.

B. napus originated from a spontaneous hybridization of Brassica rapa L. (syn. campestris; AA, 2n = 20) and Brassica oleracea L. (CC, 2n = 18). The genome of the crop is more complex than that of the model plants A. thaliana or Oryza sativa. For example, in many cases, a gene has multiple homologous copies distributed in different loci of the B. napus genomic DNA, and among these homologous loci there might be a divergence of roles in contributions to their corresponding phenotypes. Candidate gene association analysis, based on numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that varied across the natural population, is used to dissect the site/locus contributions to the target traits and further to validate gene function. This method was successfully applied to validate the role of genes Hd1, Hd3a and Ehd1 in controlling flowering time in cultivated rice, and showed that Hd1 proteins and Hd3a promoters as well asEhd1 expression levels were major factors affecting rice flowering (Takahashi et al., 2009). Recently, association analysis of a gene locus demonstrated that the B. napus DA1 locus contributed to the seed weight (Wang et al., 2017).

Diseases caused by S. sclerotiorum have traditionally been difficult to control (Bolton et al., 2006). Currently, breeding S. sclerotiorum-resistant oilseed rape cultivars using traditional methods is difficult since no immune or highly resistant germplasm in B. napus is available (Liu et al., 2005). Molecular breeding is pursued as an important strategy for controlling sclerotinia diseases. In this study, we used both gain- and loss-of-function approaches to investigate the specific role of B. napus MPK3 (BnaMPK3) in defense responses against S. sclerotiorum, and a candidate gene association analysis was used to validate the contribution of the genomic loci of the gene to resistance to the pathogen in a natural B. napus population. Our data may guide the resistance improvement of oilseed rape and related economic crops.

Materials and Methods

Plant and Fungal Materials

The B. napus cultivar Zhongshuang9 was used in this study. Plants were grown in a plant growth room under the following growth conditions: 20 ± 2°C with a photoperiod of 16 h light and 8 h dark at a light intensity of 44 μmol/m2/s and 60–90% relative humidity. Fresh sclerotia of the fungus S. sclerotiorum, collected from oilseed rape stems in the field in Zhenjiang, China, were germinated to produce hyphal inoculum on potato dextrose agar (PDA).

Isolation of BnaMPK3 cDNA

Total RNA from B. napus leaf tissues was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). After removal of genomic DNA contamination by DNase I (TaKaRa), 200 ng of poly(A)+ mRNA was converted into cDNA by MMLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega). The cDNA template was used for PCR analysis subsequently. According to the complete CDS of Brassica napus cultivar Huyou15 MAPK 3 mRNA (GenBank: AY642433.1), the BnaMPK3 cDNA was obtained using the primers BnaMPK3-F1 (5′-TCTTCTCATTTCAGTCCCTCA-3′) and BnaMPK3-R1 (5′-GGATATTTAGCCATTCATTCG-3′), cloned into PMD18-T vector (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then sequenced. The resulting plasmid pMD18-BnaMPK3 was used as template for all experiments described below. Subcellular localization of the deduced polypeptides was predicted by Plant-mPLoc1 (Chou and Shen, 2010). Multiple-aligned sequences were determined by MeGa5, and GENEDOC was used to manually edit the results.

Plasmid Construction for Transgenic Plant Generation

To construct a vector for the constitutive expression of BnaMPK3, the vector pCAMBIA1300-35S-Nos was generated by inserting two fragments from the vector pEGAD containing the CaMV 35S promoter and CaMV Nos terminator into the EcoRI/KpnI and BamHI/HindIII sites of pCAMBIA1300 (Dingguo Changsheng Biotech Co. Ltd., Beijing, China), respectively. The PCR primers were 5′-gaattcTTAATTAAGAGCTCGCATGCC-3′ and 5′-ggtaccGTCCCCGTGTTCTCTCCAA-3′ for the insertion of the CaMV 35S promoter. The primers were 5′-ggatccGAATTTCCCCGATCGTTCAA-3′ and 5′-aagcttGATCTAGTAACATAGATGACACCGC-3′ for the insertion of the CaMV Nos terminator. pCAMBIA1300-35S-Nos contains a hygromycin-resistant gene in its T-DNA region for selection of transgenic plants by hygromycin. Then, a 1,299 kb full-length BnaMPK3 cDNA was PCR amplified from its cDNA clone with the primers BnaMPK3-F2 (5′-ggtaccTCTTCTCATTTCAGTCCCTCA-3′), BnaMPK3-R2 (5′-ggatccGGATATTTAGCCATT CATTCG-3′), and inserted into the KpnI/BamHI sites of pCAMBIA1300-35S-Nos, creating a BnaMPK3-overexpressing vector 1300-35S-BnaMPK3-NOS. The inserted sequences were confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion and sequencing, and the 1300-35S-BnaMPK3-NOS vector was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (LBA4404). For construction of RNAi vector, a fragment was amplified with a pair of primers BnaMPK3-F3 (5′-ACCAGGGCTTGTCTGAGGA-3′), and BnaMPK3-R3 (5′-AATCGCAGTTGGCGTTCA-3′), and inserted into the PMD18-T vector. The target BnaMPK3-RNAi fragment was cut out from the vector and then cloned into the pCXSN vector by KpnI/BamHI and then sequenced [Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.].

Subcellular Localization of BnaMPK3

The BnaMPK3 was cloned into the vector pK7FWG2.0 to create a C-terminal GFP fusion (Invitrogen, China). The nuclear marker gene INDEHISCENT (IND) was cloned into pCX-DR (Invitrogen, China) to create a C-terminal RFP fusion. These constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (LBA4404). In these constructs, these genes were constitutively expressed under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter.

Agrobacterium infiltration into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves was performed as described previously (Wood et al., 2009). Cells of A. tumefaciens strain were cultured at 28°C for 2 days on Luria–Bertani (LB) agar medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin and 2.5 μg/mL tetracycline. The recombinant agrobacteria were grown in 10 mL LB liquid medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics at 28°C, and then harvested by centrifugation. The cell pellet was resuspended in buffer [10 mM 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulphonic acid (MES), pH 5.6, 10 mM MgCl2 and 150 μM acetosyringone], adjusted to a final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6, and incubated for 3 h at room temperature before inoculation. N. benthamiana leaves were hand infiltrated using a needleless 1-mL syringe with the transformed Agrobacterium mixed with Agrobacterium containing the gene-silencing suppressor p19 (Voinnet et al., 2003). Inoculated plants were incubated at 26°C in a growth chamber for 1–2 days. Five days after transformation, fluorescence was monitored by confocal microscopy. Fluorescence emission was at 510–540 nm for GFP and 580–584 nm for RFP, and excitation was at 488 nm for GFP and 543 nm for RFP (Wood et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2014b).

For the transient expression in N. benthamiana, the transformation was performed as described in the relevant section of above assay of subcellular localization of BnaMPK3. For the transformation in B. napus, the plants were grown in a protected field in Zhenjiang, China, and transformed by in planta Agrobacterium-mediated transformation according to the procedure described by Wang et al. (2009). The transformants were examined as described in the “Results” section.

Plant Inoculation and Chemical Treatments

Plant inoculation with S. sclerotiorum was performed as described previously (Dong et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009). The experiment was in a randomized complete block design and was repeated three times. For the transgenic plants, the experiment was performed using three independent BnaMPK3-overexpressing or -RNAi transgenic lines, respectively. Six hours after inoculation and at intervals thereafter, the lesion size was determined as the area of the lesion after S. sclerotiorum infection. Chemical treatments with SA, MeJA or ABA were performed as described previously (Wang et al., 2014a,b). The leaves were sprayed with SA (100 μM), MeJA (100 μM), ABA (50 μM) or ACC (100 μM) solutions, respectively, on their leaves for 0, 3, 6, 9, or 12 h in the dark.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from treated and control leaf samples and cDNA was synthesized as described by Wang et al. (2014a). Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR green real-time PCR master mix in an ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System with three technical replicates for each gene using different cDNAs synthesized from three biological replicates. BnTIP41 (TIP41-like protein gene) was used as reference gene (Wang et al., 2014a). The relative expression levels were estimated using the 2-ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Primers used for qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Amplification efficiencies of the primers and variation of ΔCT (CtTarget – CtTIP41) with template dilution were examined and indicated that the amplification efficiencies of the target and reference are approximately equal (Supplementary File S1). These primer sets were tested by dissociation curve analysis and verified for the absence of non-specific amplification (Supplementary File S2).

DAB Staining and Trypan Blue Staining

Procedures for DAB staining were performed as described previously (Wang et al., 2014b). For trypan blue staining, Inoculated leaves were soaked with ethanol/chloroform (3/1, vol/vol) for 24 h, stained with trypan blue solution for 4 h, and then incubated for 24 h in chloral hydrate.

Association Analysis

The association panel consisted of 324 accessions of oilseed rape collected worldwide. All the accessions were grown in the field in Wuhan, Hubei province. The field trials were designed in a randomized complete block design with three replicates. All the accessions were evaluated for resistance to S. sclerotiorum in a naturally infested nursery. Thirty-six plants from each plot were rated with a disease index (Supplementary File S3) and for disease incidence at approximately the beginning of physiological maturity.

Genomic DNA was isolated from juvenile leaves of each self-pollinated lines. The polymorphic SNPs of two genomic homologous loci of BnaMPK3 were genotyped by genomic DNA re-sequencing, and all the re-sequencing data were mapped on the reference genome “Darmor-bzh” (Chalhoub et al., 2014). The SNP variations of 324 lines were acquired using Genome Analysis ToolKit2. An association analysis was performed using general linear mode in Tassel software (Bradbury et al., 2007). The quantile–quantile plot was displayed with –log10 (P) of each SNP and expected P-value. The Manhattan plot was displayed using CMplot software3. The threshold of association analysis was set to P < 0.01.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SAS program (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States). The data relating to lesion size were subjected to one-way analysis of variance followed by a comparison of the means according to a significant difference test at P < 0.05. Using ΔCt values (target – reference), pairwise comparisons relating to PCR were conducted according to Student’s t-test at P < 0.001, 0.001 < P < 0.01 or 0.01 < P < 0.05 under the assumption that variances are unequal.

Results

Cloning of BnaMPK3 and Assessment of Its Subcellular Localization and Tissue-Specific Expression

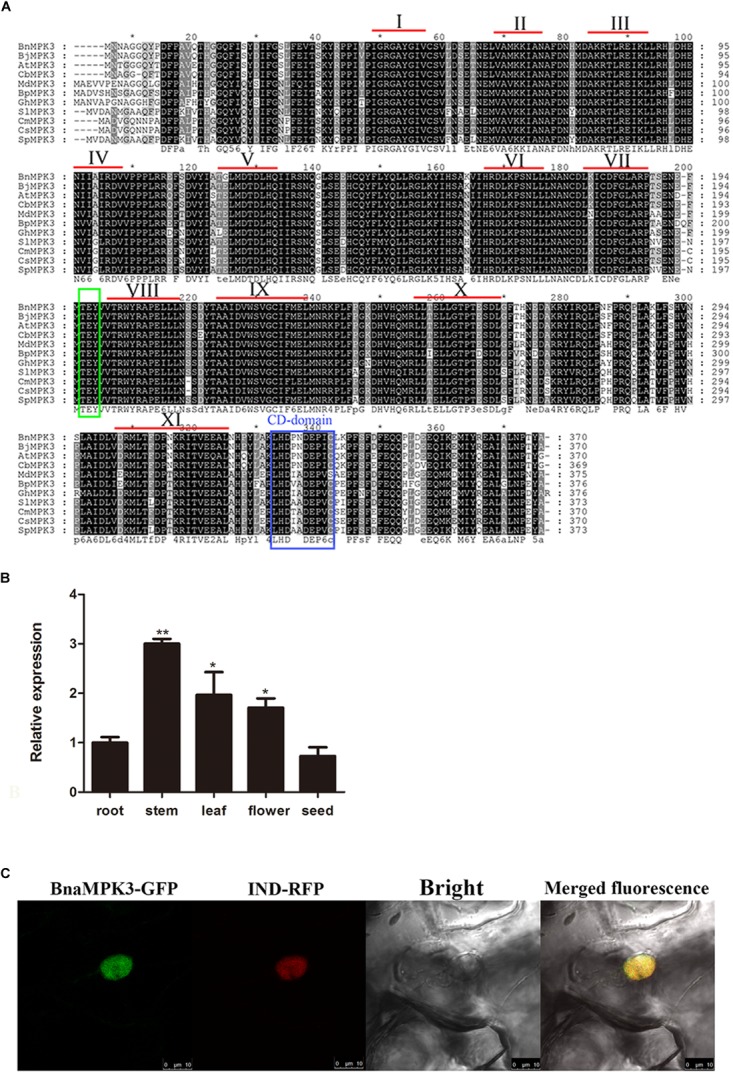

A full-length cDNA was cloned from a cDNA library of B. napus cv. Zhongshuang9, a double low (low erucic acid-low glucosinalate) cultivar with higher resistance to the pathogen S. sclerotiorum than the mid-resistant cultivar Zhongyou 821 (Wang et al., 2004), by a homology cloning approach. The entire open reading frame of the cloned cDNA encodes a protein of 370 amino acid residues with a calculated molecular mass of 42.52 kDa and a predicted pI of 5.79. To identify whether the cDNA encodes the BnaMPK3 protein, the deduced amino acid sequence was used as query in a BLASTP search of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. As shown in Figure 1A, alignment of the 10 top-scoring matches with the amplified sequence indicates that sequences of all the 11 proteins from various plant species are highly similar and contain all the eleven conserved sub-domains that are characteristic of serine/threonine protein kinases (Hanks and Hunter, 1995). Similar to AtMPK3 and other plant MPK3s, the deduced sequence possess a conserved dual phosphorylation activation motif Thr-Glu-Tyr (TEY) located between sub-domains VII and VIII as well as a common docking (CD) domain in its C-terminal extension, which is considered as the typical characteristic of MAPK family and functions as a docking site for MAPKK, phosphatases, and protein substrates (Tanoue et al., 2000). Thus, according to the existing nomenclature of plant MAPKs (Group, 2002), the cloned cDNA was designated as BnaMPK3 (GenBank accession no. KU363194).

FIGURE 1.

Sequence analysis of BnaMPK3. (A) Sequence alignment of BnaMPK3 and its homologs. The amino acid sequence of BnaMPK3 was aligned with those of the 10 closest matching proteins from a BLAST search. Identical amino acids are shown in black boxes, and similar amino acids are shown in gray boxes. The highly conserved domain TEY is shown in green box. The CD-domain is shown in blue box. According to Hanks and Hunter (1995), 11 subdomains (I–XI) are indicated by Roman numerals. Species abbreviations are as follows: Bn: Brassica napus; Bj: Brassica juncea; At: Arabidopsis thaliana; Cb: Chorispora bungeana; Md: Malus domestica; Bp: Betula platyphylla; Gh: Gossypium hirsutum; Sl: Solanum lycopersicum; Cm: Cucumis melo; Cs: Cucumis sativus, Sp: Solanum peruvianum. (B) Expression profiles of BnaMPK3. Relative expression levels of BnaMPK3 in different tissues were determined by real-time quantitative PCR. Values are means of three replicates. The error bars show the standard deviation. The significances of between each tissue and root are indicated (Student’s t-test, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗0.001 < P < 0.01 or ∗0.01 < P < 0.05). (C) Subcellular localization of BnaMPK3. In planta localization in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves of BnaMPK3-green fluorescent protein (GFP), IND (nuclear marker protein)-red fluorescent protein (RFP) and merged fluorescence from RFP and GFP.

We measured the relative expression levels of BnaMPK3 in different plant tissues using quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis. As shown in Figure 1B, the relative expression levels of BnaMPK3 in roots and seeds are very similar, whereas in flowers or leaves there is almost twofold higher expression levels, whereas stems show threefold higher expression levels than roots or seeds. S. sclerotiorum is unusual among other necrotrophic pathogens in its requirement for flower parts that fall on to the leaves or stems. Fungal ascospores then establish in leaves, and colonize leaves and stems (Bolton et al., 2006). Thus, the tissue-specific expression profile of BnaMPK3 may provide an expression support to the potential biological functions associated with the defense to S. sclerotiorum.

The subcellular localization of BnaMPK3 was also investigated. Firstly, its amino acid sequence was analyzed in the Plant-mPLoc, a top-down strategy to augment the power for predicting plant protein subcellular localization (Chou and Shen, 2010), which predicted that BnaMPK3 has a nuclear localization. At the same time, we used TMHMM4 to predict trans-membrane helices (TMHs) of the protein, but failed to identify any TMH (data not shown). In order to examine the possible nuclear localization of BnaMPK3 in planta, one construct expressing BnaMPK3 fusioned to an enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) was produced. The construct, together with another construct expressing a gene fusion of the red fluorescent protein (RFP) gene and a nuclear-localized marker gene (IND), was transiently co-transferred by infiltration of transformed Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells into N. benthamiana leaves. As shown in Figure 1C, 5 days after infiltration, GFP and RFP fluorescence in leaf cells was associated with regions of nuclei autofluorescence, and GFP and RFP fluorescence in leave cells led to yellow fluorescence. As expected, our results indicated that BnaMPK3 is primarily located in the nucleus in planta.

Expression of BnaMPK3 in Oilseed Rape During Infection of S. sclerotiorum and Treatment With Hormones

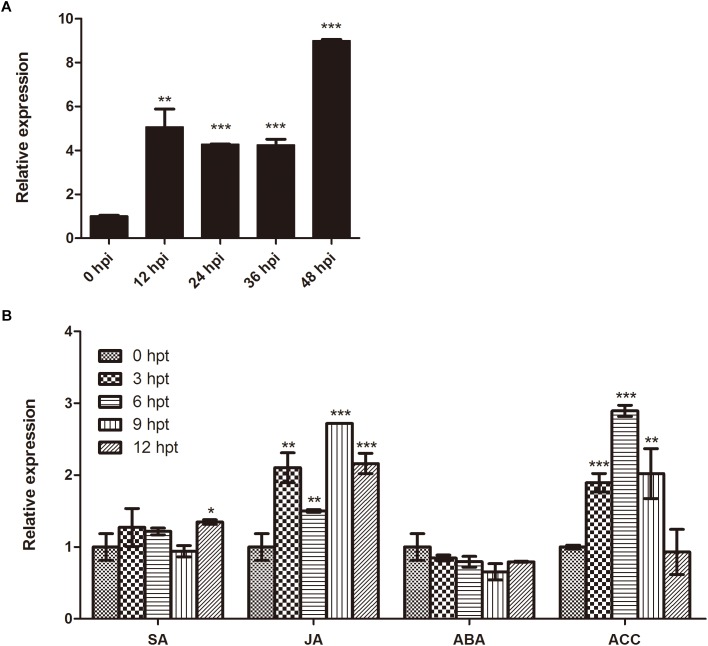

In order to determine whether expression of BnaMPK3 is responsive to S. sclerotiorum infection, we firstly searched the published microarray data and found that the BnaMPK3 gene was not identified in the experiment using an Arabidopsis-based microarray to investigate gene expression profiles in response to S. sclerotiorum in B. napus, but that an experiment using a B. napus oligonucleotide microarray showed that BnaMPK3 is induced by S. sclerotiorum (Zhao et al., 2007, 2009). To confirm the microarray results, we examined the expression of BnaMPK3 in S. sclerotiorum-infected B. napus plants using qRT-PCR. The results showed that the expression of BnaMPK3 was significantly enhanced by fourfold to ninefold (P < 0.01 or P < 0.001) within 48 h post-inoculation with the fungal pathogen (Figure 2A), indicating that BnaMPK3 is highly responsive to S. sclerotiorum infection in B. napus.

FIGURE 2.

Expression of BnaMPK3 in B. napus during infection of S. sclerotiorum and activation of plant defense responses. (A) Response of BnaMPK3 to S. sclerotiorum infection in B. napus. Relative expression levels of BnaMPK3 in B. napus were determined by real-time quantitative PCR at 0, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h post S. sclerotiorum inoculation (hpi). (B) Expression of BnaMPK3 during activation of defense responses in B. napus. Relative expression levels of BnaMPK3 in B. napus were determined by real-time quantitative PCR at 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 h post various chemicals treated. SA, salicylic acid; MeJA, methyl jasmonate; ABA, abscisic acid; ACC, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid. Values are means of three replicates. The error bars show the standard deviation. The significances of the gene expression differences between each time point and the 0-h time point are indicated (Student’s t-test, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗0.001 < P < 0.01 or ∗0.01 < P < 0.05).

Previous studies have showed that defense to S. sclerotiorum in oilseed rape involved plant defense responses mediated by various plant hormones, including SA, JA, and ET as well as ABA (Wang et al., 2012; Novakova et al., 2014). Thus, we investigate the expression of the S. sclerotiorum-induced gene BnaMPK3 during activation of these plant defense responses mediated by these hormones using the pharmacological approach. As shown in Figure 2B, the BnaMPK3 gene was induced rapidly and strongly by JA and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC), the natural precursor of ET biosynthesis. In contrast, the transcript expression of BnaMPK3 was induced only slightly by SA and was even weakly restrained by ABA. The results suggested that the expression of BnaMPK3 may be associated with the defense responses mediated by JA and ET in oilseed rape.

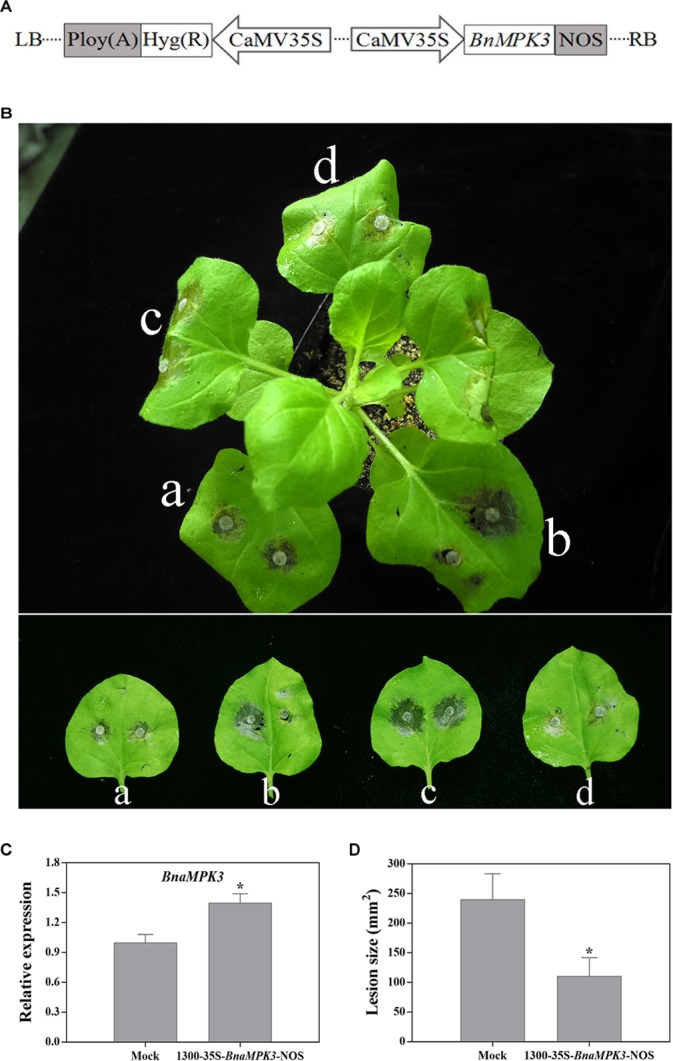

N. benthamiana Plants Transiently Expressing BnaMPK3 Enhance Resistance to S. sclerotiorum

N. benthamiana transient leaf expression system is capable of rapidly providing a clue to the gene function prior to the laborious and time-consuming stably transgenic experiment (Wood et al., 2009). Thus, to rapidly estimate the function of BnaMPK3 in defense to S. sclerotiorum, we injected the leaves of N. benthamiana with Agrobacterium containing the 1300-35S-BnaMPK3-Nos vector that contains the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter, BnaMPK3 cDNA and the CaMV Nos terminator in its T-DNA (Figure 3A). Then the leaves were inoculated with S. sclerotiorum mycelial plugs 3-day post injection and the lesion size was determined 36 h after inoculation. To minimize the effects of variables, we also injected the left or right panel of the same leaf with Agrobacterium containing the 1300-35S-BnaMPK3-Nos vector or mock solution with Agrobacterium containing the 1300-35S-Nos vector, respectively, and then investigated their difference of resistance to S. sclerotiorum. As shown in Figure 3B–D, the 1300-35S-BnaMPK3-Nos-treated leaves with the higher expression level of BnaMPK3 showed smaller lesion area than the mock-treated control, indicating that transient expression of BnaMPK3 in N. benthamiana enhances resistance to S. sclerotiorum. These primary results in N. benthamiana led us to conduct further studies on oilseed rape.

FIGURE 3.

Nicotiana benthamiana transiently expressing BnaMPK3 enhances resistance to S. sclerotiorum. (A) Diagram of the plasmids of 1300-35S-BnaMPK3-Nos used in this analysis. CaMV35S, cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter; NOS, terminator. (B) Expression of BnaMPK3 in N. benthamiana enhanced resistance to S. sclerotiorum. (a) Both left and right panel of the leaves were treated with 1300-35S-BnaMPK3-Nos vector solution. (b) The left panel of a leaves was treated with mock solution, and the right panel of the leaf was treated with 1300-35S-BnaMPK3-Nos vector solution. (c) Both left and right panel of the leaves were treated with mock solution. (d) Both left and right panel of the leaves were treated with 1300-35S-BnaMPK3-Nos vector solution. (C) Relative expression of BnaMPK3 in the treatment with mock or 1300-35S-BnaMPK3-Nos vector. (D) Lesion diameters were measured 36 h post-inoculation. Means and standard errors are shown. Letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). The experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

Altered Expression of BnaMPK3 Results in Altered Resistance to S. sclerotiorum in BnaMPK3-OE and BnaMPK3-RNAi B. napus Plants

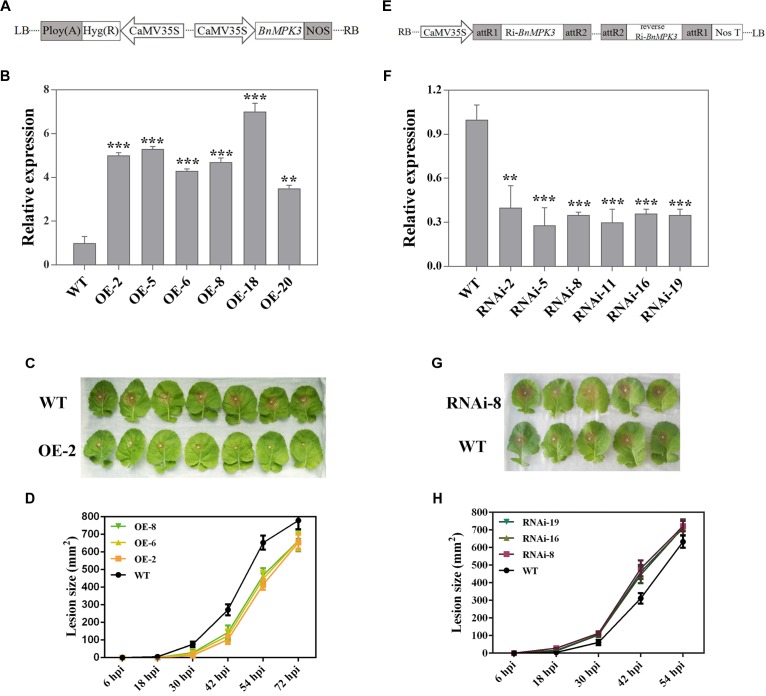

In order to determine the function of BnaMPK3 in the resistance of B. napus to S. sclerotiorum, we generated transgenic lines with overexpression (OE) of BnaMPK3 and investigated its phenotype against S. sclerotiorum infection. The full-length BnaMPK3 cDNA was cloned behind the 35S promoter and transformed into B. napus plants (Figure 4A). Hygromycin and PCR were used to screen BnaMPK3 transgenic lines. Six independent transgenic lines (OE-2, -5, -6, -8, -18, and -20) showed much higher levels of expression of the BnaMPK3 gene than the untransformed wild-type control (WT) by qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 4B), and the OE-2, -6, and -8 transgenic lines were used for further analysis.

FIGURE 4.

Altered expression of BnaMPK3 results in altered resistance to S. sclerotiorum in oilseed rape. (A) Diagram of T-DNA of the plasmid used in this overexpression analysis. CaMV35S, cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter; NOS, terminator. (B) Validation of BnaMPK3-overexpressing lines at transcription levels revealed by real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR). The significances of the gene expression differences between each BnaMPK3-overexpressing line and WT are indicated (Student’s t-test, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗0.001 < P < 0.01 or ∗0.01 < P < 0.05). (C) Disease responses of inoculated plants at 42 hour post-inoculation (hpi). (D) Disease progression is shown from 6 to 72 hpi. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Differences in susceptibility between WT and the transgenic lines were significant (P < 0.05) from 18 to 54 hpi. (E) Diagram of T-DNA of the plasmid used in this RNAi analysis. CaMV35S, cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter; NOS, terminator. (F) Validation of BnaMPK3-RNAi lines at transcription levels revealed by real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR). The significances of the gene expression differences between each BnaMPK3-RNAi line and WT are indicated (Student’s t-test, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗0.001 < P < 0.01 or ∗0.01 < P < 0.05). (G) Disease responses of inoculated plants at 30 hpi. (H) Disease progression is shown from 6 to 54 hpi. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Differences in susceptibility between WT and the transgenic lines were significant (P < 0.05) from 18 to 42 hpi. WT, untransformed wild-type control; OE-2, -5, -6, -8, -18, -20 are six independent BnaMPK3-overexpressing transgenic lines; RNAi-2, -5, -8, -11, -16, -19 are six independent BnaMPK3-RNA-interfering transgenic lines.

To test the effect of BnaMPK3 overexpression on resistance to S. sclerotiorum, T3 generation transgenic plants were selected by hygromycin screening and confirmed by PCR for the presence of the BnaMPK3 transgene. Leaves from these PCR-positive plants and their untransformed controls at the six-true-leaf stage were used for inoculation with S. sclerotiorum mycelial plugs. The results indicated that BnaMPK3-OE plants developed less severe disease symptoms and showed less tissue damage than WT controls (Figure 4C). Investigation of disease progression showed that the lesion size differences between the transgenic plants and WT controls became significant (P < 0.05) at 18–54 h post-inoculation (hpi), and there were no significant (P < 0.05) differences between these transgenic lines (Figure 4D and Supplementary Figure S1), suggesting that transgenic plants did not support rapid lesion expansion when compared with WT controls. The difference in the rate of lesion expansion suggests that BnaMPK3-mediated defenses appear to inhibit or delay the spread of the pathogen. Ultimately, disease symptoms were limited to leaves that had been inoculated and fungal spread virtually stopped in WT controls after 72 hpi. Above all we must mention that soft-rotting necrosis occurred in WT controls as early as 18 h post-inoculation (hpi) but, in transgenic plants, the necrosis lesions are invisible in this time point, and the average lesion area of transgenic plants was reduced by ∼71, 54, and 35% at 30, 42, and 54 hpi, respectively, compared with that of WT controls (Figure 4D and Supplementary Figure S1). These results strongly suggest that overexpression of BnaMPK3 significantly enhances oilseed rape resistance to S. sclerotiorum infection.

Next, we assessed the effects of the loss of BnaMPK3 function on oilseed rape resistance to S. sclerotiorum. One 214-bp complementary DNA fragment and its reverse sequence were cloned into pCXSN vector under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter for subsequent generation of oilseed rape transgenic plants with the RNA interfering (RNAi)-mediated suppression of BnaMPK3 (Figure 4E). Hygromycin and PCR were used to screen the transgenic lines. Six independent transgenic lines (RNAi-2, -5, -8, -11, -16, and -19) showed much lower expression levels of the BnaMPK3 gene than WT controls by qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 4F), and the RNAi-8, -16, and -19 transgenic lines were used for further analysis.

To investigate the effect of decrease in the BnaMPK3 expression on resistance to S. sclerotiorum, antibiotic- and PCR-positive RNAi T3 transgenic line plants were tested. As shown in Figure 4G, the BnaMPK3-RNAi plants developed more severe disease symptoms and showed more tissue damage than WT controls. Investigation of disease progression showed that from 18 to 42 hpi, lesion sizes of all the three transgenic lines tested were significantly larger (P < 0.05) than those of WT controls, and there were no significant (P < 0.05) differences between these transgenic lines (Figure 4H and Supplementary Figure S2), suggesting that down-expression of BnaMPK3 enhances susceptibility to S. sclerotiorum infection. Ultimately, disease symptoms were limited to inoculated leaves and fungal spread virtually stopped in these RNAi plants after 54 hpi.

The BnaMPK3-OE and BnaMPK3-RNAi plants grew and developed normally, indistinguishable from WT controls, at vegetable and reproductive stages (Supplementary Figure S3). Similarly, the Arabidopsis mpk3 loss-of-function mutants resemble wild type plants, showing normal development, and only the combination of both mpk3 and mpk6 mutations impairs normal development, suggesting a strongly developmental redundancy (Wang et al., 2007).

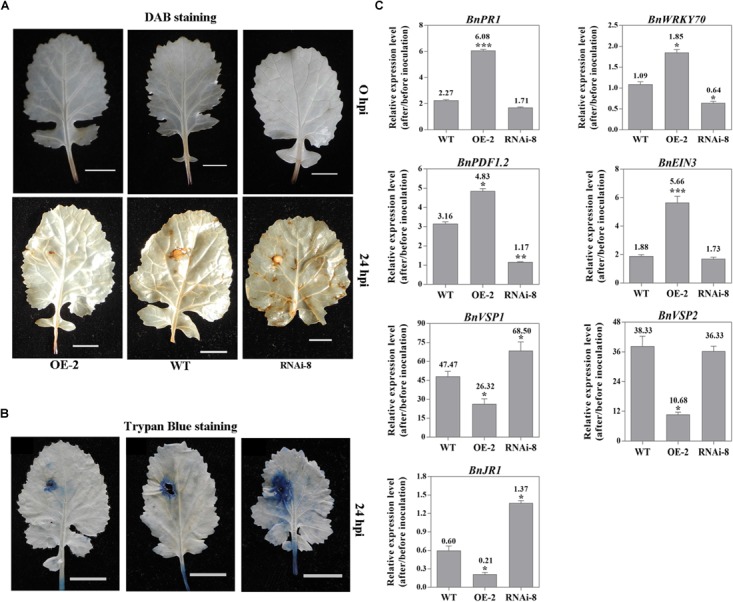

Altered Expression of BnaMPK3 Affects S. sclerotiorum-Induced Defense Responses in BnaMPK3-OE and BnaMPK3-RNAi B. napus Plants

To examine whether altered expression of BnaMPK3 affected the defense responses under the infection by S. sclerotiorum, we analyzed and compared the patterns for accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and expression of defense genes after the pathogen infection in the WT as well as BnaMPK3-OE and BnaMPK3-RNAi lines. In assays for in situ detection of ROS, accumulation of H2O2, a major component of ROS, in leaves was detected by 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining. As shown in Figure 5A, without pathogen challenge, no difference in accumulation of H2O2 was seen among different plant lines. In turn, at 24 h after inoculation by S. sclerotiorum, accumulation of H2O2 remarkably increased in inoculated leaves. In turn, more staining was observed in leaves of BnaMPK3-RNAi plants exhibiting enhanced susceptibility to S. sclerotiorum while less in leaves of BnaMPK3-OE plants exhibiting enhanced resistance to the pathogen, as compared to that in WT controls (Figure 5A). The ROS accumulation is one of most universal responses observed in plants following pathogen challenge (Apel and Hirt, 2004), and accumulating evidence has shown that the induction of plant ROS by S. sclerotiorum infection leads to cell death in host tissue and that the control of cell death governs the outcome of the S. sclerotiorum–plant interaction (Dickman et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2011; Kabbage et al., 2013). Thus, we investigated the cell death extent using Trypan Blue staining when H2O2 accumulates in the infected leaves. As shown in Figure 5B, in response to S. sclerotiorum infection, plant cell death as shown by trypan blue staining is in agreement with the accumulation of H2O2 as shown by DAB staining. These results demonstrate that the resistance-enhanced BnaMPK3-overexpressing plants inhibited both H2O2 accumulation and cell death in response to S. sclerotiorum infection, whereas the susceptibility-enhanced RNAi plants intensify them, when compared with WT controls.

FIGURE 5.

Altered expression of BnaMPK3 affects S. sclerotiorum-induced defense response in BnaMPK3-OE and BnaMPK3-RNAi plants. (A) H2O2 accumulation in inoculated leaves. In situ detection of H2O2 was performed using 3,3-diaminobenzidine staining in the BnaMPK3-overexpressing transgenic line 2 (OE-2), the untransformed wild-type (WT) control and the BnaMPK3-RNA-interfering transgenic line 8 at 0 and 24 h post-inoculation with S. sclerotiorum (hpi). (B) Plant cell death was examined by using trypan blue staining on leaves of the line OE-2, WT control and the line RNAi-8. (C) Changes in expression of defense genes associated with SA, JA, and ET defense signaling in OE-2, WT, and RNAi-8 plants after 24 hpi. Samples were collected at the indicated time for total RNAs isolation. Expressions of these genes were quantified by real-time PCR, and then change of gene expression (folds of change relative to the level before inoculation) was calculated. Values are means of three replicates, and error bars indicate standard deviations. The significances of the gene expression differences between each transgenic line and WT are indicated (Student’s t-test, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗0.001 < P < 0.01 or ∗0.01 < P < 0.05). These above experiments were repeated with the BnaMPK3-overexpressing lines 6 and 8, and the BnaMPK3-RNAi lines 16 and 19, respectively, and results are similar.

On the other hand, we investigate changes in the expression of defense genes associated with SA, JA, and ET defense signaling in the three kinds of plants after S. sclerotiorum infection. Seven signaling marker genes were selected to represent the well-characterized SA- and JA/ET-dependent defense pathways, including SA signaling marker genes PR1, encoding a pathogenesis-related protein1, and WRKY70, encoding a plant-specific transcription factor WRKY70 that is downstream of NPR1 in SA signal pathway, the JA/ET signaling marker gene PDF1.2, encoding a JA/ET-responsive plant defensin, JA responsive genes including VEGATATIVE STORAGE PROTEIN1 (VSP1), VSP2 and JASMONATE RESPONSIVE1 (JR1), and the ET signaling marker gene EIN3, encoding the critical transcription factor that is downstream of EIN2, which quickly accumulate in the presence of ET and confer specificity to ET response (Solano et al., 1998; Rojo et al., 1999; Guo and Ecker, 2003; Potuschak et al., 2003; Gagne et al., 2004; Li et al., 2004; Lorenzo et al., 2004; An et al., 2010; Zhao and Guo, 2011; Ji and Guo, 2013). The qRT-PCR analyses indicated that all the signaling marker genes exhibited enhanced expression in WT controls after S. sclerotiorum infection, which is in good agreement with the previous observation (Wang et al., 2012; Novakova et al., 2014). However, the expression of BnPR1, BnWRKY70, BnPDF1.2 and BnEIN3 was higher in the plants overexpressing BnaMPK3 and was lower in the plants down-expressing BnaMPK3 than in WT controls, whereas BnVSP1, BnVSP2 and JR1 exhibit inverse expression pattern by comparison (Figure 5C). The results suggest that altered expression of BnaMPK3 affects the pathogen-induced defense responses including ROS accumulation, cell death and expression of defense genes associated with SA, JA, and ET defense signaling in BnaMPK3-OE and BnaMPK3-RNAi plants, and the expression of these defense responses is generally in an inverse pattern between the BnaMPK3-OE and the BnaMPK3-RNAi plants.

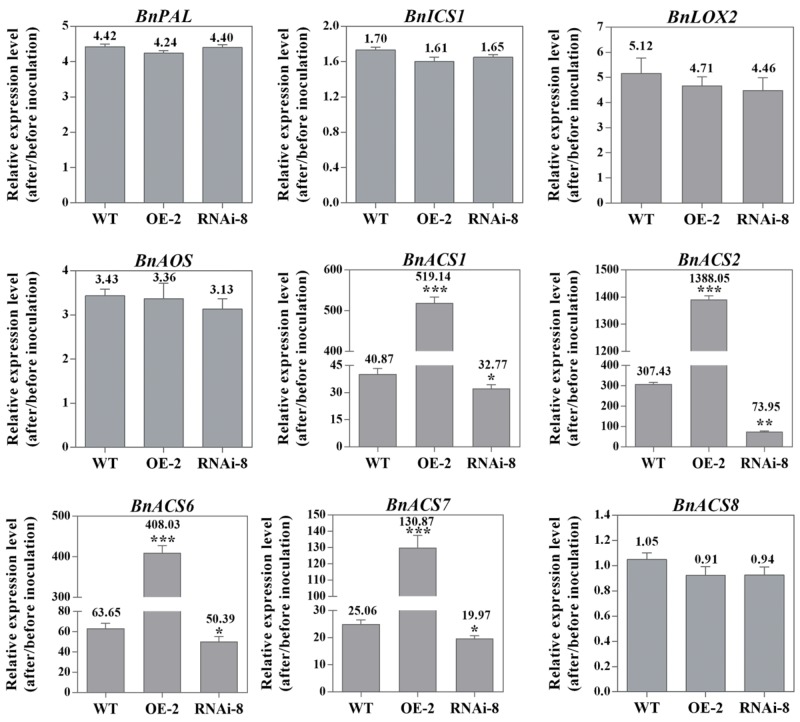

BnaMPK3 Differentially Regulates the Expression of SA, JA, and ET Biosynthesis Genes in Response to S. sclerotiorum Infection

We have shown that the marker genes associated with SA, JA, and ET defense signaling are differentially express in different plant lines under S. sclerotiorum infection. In order to have a deeper understand of these important signaling pathways, we next tested if the biosynthetic genes of the three important defense signaling molecules SA, JA, and ET have corresponding expression profiles. For SA, we selected phenylalanine ammonia lyase gene (PAL) and isochorismate synthase gene (ICS1), two key SA biosynthesis genes (Lee et al., 1995; Wildermuth et al., 2001). The results showed that the two genes have not significant difference in transcript level among different plant lines, though they all are induced by S. sclerotiorum (Figure 6). Similar expression profiles appear also in lipoxygenase gene (LOX2) and allene oxide synthase gene (AOS), two key JA biosynthesis genes (Figure 6) (Sasaki et al., 2001; Park et al., 2002; von Malek et al., 2002). The results suggested that the expression of SA and JA biosynthesis genes in response to S. sclerotiorum infection is independent on BnaMPK3, though the pathogen can induce their expression.

FIGURE 6.

BnaMPK3 differentially regulates the expression of SA, JA, and ET biosynthesis genes in response to S. sclerotiorum infection. Changes in expression of the genes involving in SA, JA, and ET biosynthesis in the BnaMPK3-overexpressing transgenic line 2 (OE-2), the untransformed wild-type (WT) control and the BnaMPK3-RNA-interfering transgenic line 8 (RNAi-8) plants after 24 hpi. Samples were collected at the indicated time for total RNAs isolation. Expressions of these genes were quantified by real-time PCR, and then change of gene expression (folds of change relative to the level before inoculation) was calculated. Values are means of three replicates, and error bars indicate standard deviations. The significances of the gene expression differences between each transgenic line and WT are indicated (Student’s t-test, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗0.001 < P < 0.01 or ∗0.01 < P < 0.05). These experiments were repeated with the BnaMPK3-overexpressing lines 6 and 8, and the BnaMPK3-RNAi lines 16 and 19, and results are similar.

In ET biosynthesis, the rate-limiting enzyme is ACS (1-amino-cyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase, ACC synthase), encoded by a small gene family in plants, and based on the presence/absence of phosphorylation sites in their C-termini. The different ACS isoforms have been classified into three types (Yoshida et al., 2005). In the study, to test whether BnaMPK3 regulates the three types ACS isoforms in the interaction between the crop oilseed rape and S. sclerotiorum, we selected the Type I ACS genes BnACS1, BnACS2 and BnACS6, the Type II gene BnACS8 and the Type III gene BnACS7. As shown in Figure 6, transcripts of BnACS1, BnACS2, BnACS6 and BnACS7 accumulated approximately 40, 307, 63, and 25 folds, respectively, over their basal levels in the untransformed WT controls in response to S. sclerotiorum infection. However, when observed on the transgenic plants, we found that their transcripts were further elevated to about 519, 1388, 408, and 130 folds, respectively, in the BnaMPK3-OE plants, whereas they were suppressed in BnaMPK3-RNAi plants exhibiting about 32, 73, 50, and 19 folds, respectively, over their basal levels. In contrast, transcript of BnACS8 was not affected in different plant lines when infected by the pathogen. These results showed that BnaMPK3 is a positive regulator of Type I ACS genes BnACS1, BnACS2 and BnACS6 and the Type III gene BnACS7 in response to S. sclerotiorum infection.

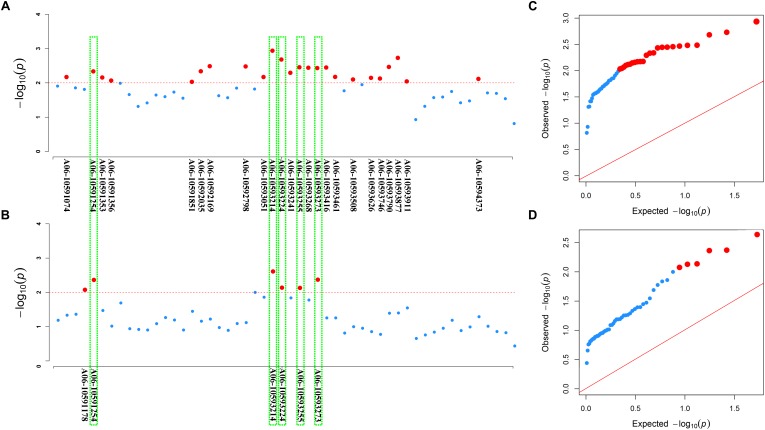

Association Analysis of the BnaMPK3 Homologous Copies in the Genomic DNA

Through a BLAT search in B. napus genomic database5, the coding sequence of BnaMPK3 was mapped into the genomic region of 44389463–44391236 (BnaC03g55440D) of the chrC03 chromosome and the other genomic region of 10591788–10593582 (BnaA06g18440D) of the chrA06 chromosome of B. napus cv. ZS11 (Chalhoub et al., 2014), indicating that the gene has two homologous copies in the genomic DNA, and sequence comparison showed that the two copies have the same exon–intron organization (Supplementary Figures S4, S5).

Furthermore, we used association analysis of a set of 324 accessions collected from different geographic position to dissect roles of the two loci BnaC03g55440D and BnaA06g18440D in contributing to the resistance to S. sclerotiorum. In the natural B. napus population, disease index varied from 7.14 to 100, and disease incidence rate varied from 19 to 100%. The results displayed there are 24 and 6 significantly associated SNPs for disease index and disease incidence rate, respectively, were detected in the locus BnaA06g18440D by re-sequencing (Figure 7A,B). For disease index, the 24 significantly associated SNPs explain 3.56–4.88% of the variation in this population, and for disease incidence rate, the six significantly associated SNPs explain 3.60–4.39%. And of these, five SNPs are for both disease index and disease incidence rate (Figure 7A,B). In the QQ plot, the observed value of these SNPs significantly deviates from expected value (Figure 7C,D), indicating that they were associated with the resistance to S. sclerotiorum. In contrast, in the locus BnaC03g55440D, no significantly associated SNPs for both disease index and disease incidence rate are found (data not shown), indicating that for the two homologs of BnaMPK3, BnaA06g18440D, but not BnaC03g55440D, is a cause of variation in the resistance to S. sclerotiorum in natural B. napus population.

FIGURE 7.

Association of SNP polymorphisms with disease index or disease incidence rate across the BnaA06g18440D locus of BnaMPK3. (A) Manhattan plot for disease index or (B) disease incidence rate. The threshold of association analysis was set to P < 0.01. The red-dotted line was –log10(p) = –log10(0.01) = 2.0, and the red dot above the red-dotted line represents a significantly associated SNP. The red dots in the green box are significantly associated SNPs for both disease index and disease incidence rate. (C) The Q–Q plots for disease index or (D) disease incidence rate from association analysis. The red line was the unbiased estimates of the expected and observed value. Red dots were the significant SNPs.

Discussion

In this study, we provide new data that enlarge the understanding of MPK3 functions, indicating that BnaMPK3, an MPK3 ortholog in B. napus, plays an important role in the defense against S. sclerotiorum, the most important pathogen of the crop. Our results show that not only is the expression of BnaMPK3 highly responsive to the necrotrophic S. sclerotiorum infection, but it is also induced by JA and the biosynthesis precursor of ET, two signaling molecules associated with defense against necrotrophic pathogens (Wang et al., 2012). Further, overexpression of BnaMPK3 in B. napus and N. benthamiana results in significantly enhanced resistance to S. sclerotiorum, the RNAi transgenic plants significantly reduce the resistance, and the expression of defense responses is generally in an inverse pattern between the BnaMPK3-OE and the BnaMPK3-RNAi plants. These results indicate a clear biological function of BnaMPK3 in the host defense of the crop to the agriculturally devastating plant pathogen. Unlike Arabidopsis, B. napus, the allotetraploid species, usually has multiple homologs with putatively redundant functions on the A and C genomes. To alter a monogenic trait for evaluating the role of the target gene, therefore, it is necessary to combine mutated homologs from both subgenomes (Wells et al., 2014; Emrani et al., 2015). Indeed, in this study, the RNAi construct can down-regulate the expression of both BnaA06g18440D and BnaC03g55440D, the two homologs from A and C subgenomes, respectively, because both BnaA06g18440D and BnaC03g55440D contain the RNAi sequence (Supplementary Figures S4, S5). Further, the candidate gene association analysis yield additional insights and suggest that the allelic variation in BnaA06g18440D, the homeolog on A genomes, is a source of resistance diversity in cultivated B. napus. We also noticed that the phenotypic contribution of these significant SNPs, detected by association analysis, was low. The reason may be that the resistance to S. sclerotiorum is a complex quantitative trait controlled by many quantitative trait loci (QTLs) (Bert et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2006). In fact, most of the QTLs identified through QTL mapping studies also show small effects on the resistance to S. sclerotiorum in B. napus (Zhao, 2003; Zhao et al., 2006; Yin et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2014). A similar phenomenon also is observed in the resistance of soybean to the pathogen, in which many of the SNPs explains 3.2–5.1% of the variation in the soybean population (Wen et al., 2018). Thus, these results suggested that the resistance to S. sclerotiorum is a trait with very complex genetic basis determined by multiple minor QTLs.

The positive role of BnaMPK3 in the defense responses is closely associated with high expression levels of BnACS genes. First, the expression of BnACSs, consistent with BnaMPK3, is highly responsive to S. sclerotiorum infection. For example, S. sclerotiorum-responsive expression of BnACS2 increased by more than 300 folds relative to its basal level. Further, the expression level of the BnACSs was striking elevated in the BnaMPK3-overexpressing resistant plants and suppressed in the BnaMPK3-downexpressing susceptible plants. Especially in the case of BnACS2, its elevated expression level is up to about 1400 folds in the BnaMPK3-OE plants. These results indicate that BnaMPK3 strongly positively regulates ET signaling in response to S. sclerotiorum infection. This is also supported by the expression of BnEIN3, a key gene that regulates most, if not all, of the ET responsiveness (Alonso et al., 2003; An et al., 2010), in BnaMPK3-OE plants (Figure 5). Previously, studies on Arabidopsis showed that the mutant eto3, affected in the regulation of ET signaling (Chae et al., 2003), is significantly affected in resistance to S. sclerotiorum, and the ET-insensitive mutant ein2-1 showed a significantly increased susceptibility to the fungus (Guo and Stotz, 2007; Perchepied et al., 2010). Thus, taking these data together, it is possible that the positive regulation of ET signaling by BnaMPK3 plays a key role in the defense response to S. sclerotiorum. On the other hand, in contrast to the positive effect of BnaMPK3 on ET signaling, we also observed that application of ACC, the biosynthesis precursor of ET, results in the activation of BnaMPK3 expression, indicating that the expression of BnaMPK3 and ET biosynthesis genes forms a positive feedback loop in response to S. sclerotiorum infection. Thus, our results suggest that the activation of ET defense signaling is important for the resistance conferred by BnaMPK3.

Previously, based on the microarray data, Zhao et al. (2009) detected that S. sclerotiorum induces the type I BnACS6 expression in B. napus plants. Recently, Novakova et al. (2014) reported that in addition to BnACS6, BnACS2, another type I ACS, can also be induced in response to the pathogen infection. Here, our data suggest that in addition to BnACS2 and BnACS6, the Type I ACS gene BnACS1 and the Type III gene BnACS7 are also highly responsive to S. sclerotiorum infection, and further indicate that the expression of these BnACSs is positively regulated by BnaMPK3. By contrast, in the case of the Type II BnACS8, while the gene cannot be induced by S. sclerotiorum infection, its expression is also not affected by the alteration of BnaMPK3 expression, suggesting differential implication of these types of enzymes in response to the pathogen and in the regulatory mechanism. Additionally, we observed that the reduced magnitude of expression of these pathogen-responsive BnACS genes as well as other genes in the BnaMPK3-RNAi plants is obviously less than the elevated magnitude in BnaMPK3-overexpressing plants. This may be due to overlapping function shared by others in activating the expression of these genes in the interaction of B. napus-S. sclerotiorum, as observed in the Arabidopsis and B. cinerea interaction in which the expression of AtACS2 and AtACS6 genes decrease only slightly in the mpk3 or mpk6 single mutant, whereas greatly decrease in mpk3/mpk6 double mutant, suggesting the absence of only one MAPK may not be sufficient to block ACSs activation (Li et al., 2012).

By contrast, the expression change of BnAOS and BnLOX2 in BnaMPK3-OE or BnaMPK3-RNAi lines had not significant difference from that in the WT after S. sclerotiorum infection, suggesting that the two JA-biosynthetic genes do not appear to be involved in the defense responses mediated by BnaMPK3. Previously, it has been shown that JAR1, another JA signaling gene encoding an enzyme that generates the jasmonyl-isoleucine (JA-Ile) conjugate (Staswick and Tiryaki, 2004), does not play a role in the resistance because the jasmonate-resistant mutant jar1-1 was not affected for responsiveness to S. sclerotiorum and showed a completely wild-type phenotype in response to the pathogen (Perchepied et al., 2010), though exhibiting enhanced sensitivity to another fungal necrotrophic Pythium irregulare (Adie et al., 2007). However, the Arabidopsis mutant coi1-1 that completely blocks both JA- and ET-induced PDF1.2 expression (Pré et al., 2008; Perchepied et al., 2010) is highly susceptible to S. sclerotiorum (Guo and Stotz, 2007), suggesting a role for a cooperation of JA and ET signaling. It has been well established that ET and JA signaling interact both synergistically and antagonistically in Arabidopsis (Glazebrook, 2005; Pieterse et al., 2009). For instance, some genes, including EIN3 and PDF1.2, are synergistically activated by JA and ET (Chao et al., 1997; Solano et al., 1998; Alonso et al., 2003; An et al., 2010), whereas JA-mediated activation of other genes, including VSP1, VSP2, and JR1, are suppressed by ET (Rojo et al., 1999; Lorenzo et al., 2004). The two signaling interactions are compatible with our observation in which the expression of BnEIN3 and BnPDF1.2 is positively correlated with that of BnACSs in BnaMPK3-OE or –RNAi plants, whereas BnVSP1, BnVSP2, and BnJR1 exhibit negative correlation, suggesting that the different expression patterns of these JA and/or ET signaling genes are outcomes of the interaction between the two signaling.

It is generally accepted that SA signaling has a central role in response to biotrophic pathogens, but mutant affected in the signaling showed significantly reduced resistance to the necrotrophic S. sclerotiorum in Arabidopsis (Guo and Stotz, 2007). In favor of a role of the signaling in this interaction between B. napus and S. sclerotiorum, is the recent discoveries that exogenous SA induces resistance to the pathogen (Li et al., 2012; Novakova et al., 2014). Further supporting the role of SA signaling in the resistance, the expression of BnPR1 and BnWRKY70, two SA signaling downstream genes, are significantly elevated expression in the resistance-enhanced BnaMPK3-overexpressing plants, although the expression of SA biosynthesis genes BnICS1 and BnPAL are not affected by BnaMPK3, suggesting that BnaMPK3 act in the downstream of SA signaling to activate the defense response that takes part in the contributions to the resistance. Recently, it was suggested that there is a potential short biotrophic phase in the lifestyle of S. sclerotiorum, and a new model depicting the lifestyle transition of the pathogen from biotrophic to necrotrophic growth was proposed (Kabbage et al., 2015). Thus, our previous observations suggest that SA defense signaling might function on the biotrophic phase of the pathogen.

BnaMPK3 might involve redox control to be in favor of inhibition to the S. sclerotiorum infection, as cell death caused by the infection is significantly inhibited in H2O2 accumulation-suppressed BnaMPK3-OE plants. Previously, Kim et al. (2008) have showed that when ROS induction is inhibited, programmed cell death (PCD) induced by oxalic acid, an important pathogenicity determinant of S. sclerotiorum, does not occur and the PCD response is required for disease development of the pathogen. Recent studies showed that the control of cell death governs the outcome of the S. sclerotiorum–plant interaction (Kabbage et al., 2013) and, once infection is established, the S. sclerotiorum induces the generation of plant ROS, leading to PCD of host tissue, the result of which is of direct benefit to the pathogen (Williams et al., 2011). These results are also supported by our observation in which the S. sclerotiorum-induced H2O2 accumulation is negatively correlated with the altered resistance in the OE and RNAi plants, suggesting that the control of ROS accumulation is another defense mechanism of the resistance conferred by BnaMPK3 against S. sclerotiorum.

In summary, our study reveals that BnaMPK3 is a key regulator of defense responses to S. sclerotiorum in oilseed rape. These data, especial those in the analysis on the overexpression of the gene, suggested that BnaMPK3 is a promising gene for crop improvement, and that the BnaA06g18440D could be developed as a functional molecular marker in marker assistant breeding for the improvement in resistance to S. sclerotiorum because of the allelic variation of the locus in cultivated B. napus.

Author Contributions

ZW and X-LT designed the experiments. ZW, L-LB, F-YZ, TC, HF, and G-YL carried out the experiments. ZW, X-LT, S-YL, YL and BF analyzed experimental results. ZW, JC, B-XW, L-ND, and K-MZ analyzed sequencing data and did statistical analysis. M-QT and B-XW analyzed GWAS data and made figures. ZW wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Nos. 2016YFD0101904 and 2016YFD0100305), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31771836, 31071672, and 31671590), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation-funded project (2013T60507).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.00091/full#supplementary-material

Disease progression of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in BnaMPK3 overexpression lines and the untransformed wild-type control. The pictures were taken at leaves from seven plants of WT and seven hygromycin- and PCR-positive plants of line 2. WT means the untransformed wild-type control; OE-2 means the BnaMPK3-overexpressing transgenic line 2; hpi means hour post-inoculation.

Disease progression of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in BnaMPK3 RNAi lines and the untransformed wild-type control. The pictures were taken at leaves from five plants of WT and five hygromycin- and PCR-positive plants of line 8. WT means the untransformed wild-type control; RNAi-8 means the BnaMPK3-RNA-interfering transgenic line 8; hpi means hour post-inoculation.

The BnaMPK3-OE and BnaMPK3-RNAi line plants grow and develop normally at vegetable and reproductive stages. (A) Seedling height. (B) Seedling fresh weight. (C) Plant height in the mature stage. (D) Efficient primary branches. (E) Liliques on main inflorescence. (F) Efficient siliques/plant. (G) Seeds/silique. (H) 1000 seeds weight. (I) Whole plant seeds weight. Value represents mean and error bars indicate standard deviations from three independent rapeseed samples. There were no significant difference between transgenic lines (OE-2 or RNAi-8) and WT (P < 0.05). These above experiments were repeated with the BnaMPK3-overexpressing lines 6 and 8, and the BnaMPK3-RNAi lines 16 and 19, respectively, and results are similar.

Sequence alignment of BnaMPK3 and BnaC03g55440D. The coding sequence of BnaMPK3 was aligned with BnaC03g55440D from a BLAT search. Identical nucleotide bases are shown in black boxes. The intron sequences are shown in the yellow boxes. The RNAi sequences are showed within the red frame.

Sequence alignment of BnaMPK3 and BnaA06g18440D. The coding sequence of BnaMPK3 was aligned with BnaA06g18440D from a BLAT search. Identical nucleotide bases are shown in black boxes. The intron sequences are shown in the yellow boxes. The RNAi sequences are showed within the red frame.

Primers used for qRT-PCR.

The efficiencies (E) of the primer-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifications and variation of ΔCT (CtTarget - CtTIP41) with template dilution.

Dissociation curves for all amplicons generated by all primer sets.

A disease index used to evaluate the symptom severity at maturity.

References

- Adie B. A., Pérez-Pérez J., Pérez-Pérez M. M., Godoy M., Sánchez-Serrano J. J., Schmelz E. A., et al. (2007). ABA is an essential signal for plant resistance to pathogens affecting JA biosynthesis and the activation of defenses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19 1665–1681. 10.1105/tpc.106.048041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J. M., Stepanova A. N., Solano R., Wisman E., Ferrari S., Ausubel F. M., et al. (2003). Five components of the ethylene-response pathway identified in a screen for weak ethylene-insensitive mutants in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 2992–2997. 10.1073/pnas.0438070100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An F., Zhao Q., Ji Y., Li W., Jiang Z., Yu X., et al. (2010). Ethylene-induced stabilization of ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 and EIN3-LIKE1 is mediated by proteasomal degradation of EIN3 binding F-box 1 and 2 that requires EIN2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22 2384–2401. 10.1105/tpc.110.076588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel K., Hirt H. (2004). Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55 373–399. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bert P. F., Jouan I., Labrouhe T. D. D., Serre F., Nicolas P., et al. (2002). Comparative genetic analysis of quantitative traits in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) 1. QTL involved in resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Diaporthe helianthi. Theor. Appl. Genet. 105 985–993. 10.1007/s00122-002-1004-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton M. D., Thomma B. P., Nelson B. D. (2006). Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary: biology and molecular traits of a cosmopolitan pathogen. Mol. Plant Pathol. 7 1–16. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury P. J., Zhang Z., Kroon D. E., Casstevens T. M., Ramdoss Y., Buckler E. S. (2007). TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics 23 2633–2635. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen P., Petersen M., Bjørn Nielsen H., Zhu S., Newman M.-A., Shokat K. M., et al. (2006). Arabidopsis MAP kinase 4 regulates salicylic acid- and jasmonic acid/ethylene-dependent responses via EDS1 and PAD4. Plant J. 47 532–546. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cessna S. G., Sears V. E., Dickman M. B., Low P. S. (2000). Oxalic acid, a pathogenicity factor for Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, suppresses the oxidative burst of the host plant. Plant Cell 12 2191–2200. 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae H. S., Faure F., Kieber J. J. (2003). The eto1, eto2, and eto3 mutations and cytokinin treatment increase ethylene biosynthesis in Arabidopsis by increasing the stability of ACS protein. Plant Cell 15 545–559. 10.1105/tpc.006882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalhoub B., Denoeud F., Liu S., Parkin I. A., Tang H., et al. (2014). Plant genetics. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science 345 950–953. 10.1126/science.1253435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao Q., Rothenberg M., Solano R., Roman G., Terzaghi W., Ecker J. R. (1997). Activation of the ethylene gas response pathway in Arabidopsis by the nuclear protein ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and related proteins. Cell 89 1133–1144. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80300-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K. C., Shen H. B. (2010). Plant-mPLoc: a top-down strategy to augment the power for predicting plant protein subcellular localization. PLoS One 5:e11335. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman M. B., Park Y. K., Oltersdorf T., Li W., Clemente T., French R. (2001). Abrogation of disease development in plants expressing animal antiapoptotic genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 6957–6962. 10.1073/pnas.091108998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X., Ji R., Guo X., Foster S. J., Chen H., Dong C., et al. (2008). Expressing a gene encoding wheat oxalate oxidase enhances resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in oilseed rape (Brassica napus). Planta 228 331–340. 10.1007/s00425-008-0740-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emrani N., Harloff H. J., Gudi O., Kopisch-Obuch F., Jung C. (2015). Reduction in sinapine content in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) by induced mutations in sinapine biosynthesis genes. Mol. Breed. 35:37 10.1007/s11032-015-0236-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frei dit Frey N., Garcia A. V., Bigeard J., Zaag R., Bueso E., et al. (2014). Functional analysis of Arabidopsis immune-related MAPKs uncovers a role for MPK3 as negative regulator of inducible defences. Genome Biol. 15:R87. 10.1186/gb-2014-15-6-r87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne J. M., Smalle J., Gingerich D. J., Walker J. M., Yoo S. D., Yanagisawa S., et al. (2004). Arabidopsis EIN3-binding F-box 1 and 2 form ubiquitin-protein ligases that repress ethylene action and promote growth by directing EIN3 degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 6803–6808. 10.1073/pnas.0401698101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J. (2005). Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43 205–227. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group M. (2002). Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in plants: a new nomenclature. Trends Plant Sci 7 301–308. 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02302-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Ecker J. R. (2003). Plant responses to ethylene gas are mediated by SCF (EBF1/EBF2)-dependent proteolysis of EIN3 transcription factor. Cell 115 667–677. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00969-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Stotz H. U. (2007). Defense against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Arabidopsis is dependent on jasmonic acid, salicylic acid, and ethylene signaling. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20 1384–1395. 10.1094/MPMI-20-11-1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon K., Balague C., Roby D., Raffaele S. (2014). Secretome analysis reveals effector candidates associated with broad host range necrotrophy in the fungal plant pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. BMC Genomics 15:336. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks S. K., Hunter T. (1995). Protein kinases 6. the eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification. FASEB J. 9 576–596. 10.1096/fasebj.9.8.7768349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y., Guo H. (2013). From endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to nucleus: EIN2 bridges the gap in ethylene signaling. Mol. Plant 6 11–14. 10.1093/mp/sss150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbage M., Williams B., Dickman M. B. (2013). Cell death control: the interplay of apoptosis and autophagy in the pathogenicity of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003287. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbage M., Yarden O., Dickman M. B. (2015). Pathogenic attributes of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: switching from a biotrophic to necrotrophic lifestyle. Plant Sci. 233 53–60. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. S., Min J. Y., Dickman M. B. (2008). Oxalic acid is an elicitor of plant programmed cell death during Sclerotinia sclerotiorum disease development. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 21 605–612. 10.1094/MPMI-21-5-0605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D., Klessig D. F. (2000). Differential induction of tobacco MAP kinases by the defense signals nitric oxide, salicylic acid, ethylene, and jasmonic acid. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 13 347–351. 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.3.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. I., Leon J., Raskin I. (1995). Biosynthesis and metabolism of salicylic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 4076–4079. 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Brader G., Palva E. T. (2004). The WRKY70 transcription factor: a node of convergence for jasmonate-mediated and salicylate-mediated signals in plant defense. Plant Cell 16 319–331. 10.1105/tpc.016980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Meng X., Wang R., Mao G., Han L., Liu Y., et al. (2012). Dual-level regulation of ACC synthase activity by MPK3/MPK6 cascade and its downstream WRKY transcription factor during ethylene induction in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002767. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Wang H., Zhang J., Fitt B. D., Xu Z., Evans N., et al. (2005). In vitro mutation and selection of doubled-haploid Brassica napus lines with improved resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Cell Rep. 24 133–144. 10.1007/s00299-005-0925-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo O., Chico J. M., Sanchez-Serrano J. J., Solano R. (2004). Jasmonate-insensitive1 encodes a MYC transcription factor essential to discriminate between different jasmonate-regulated defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16 1938–1950. 10.1105/tpc.022319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X., Zhang S. (2013). MAPK cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 51 245–266. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami H., Pitzschke A., Hirt H. (2005). Emerging MAP kinase pathways in plant stress signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 10 339–346. 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta Y., Ding P., Zhang Y. (2014). Identification of additional MAP kinases activated upon PAMP treatment. Plant Signal. Behav. 9:e976155. 10.4161/15592324.2014.976155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakova M., Sasek V., Dobrev P. I., Valentova O., Burketova L. (2014). Plant hormones in defense response of Brassica napus to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum - reassessing the role of salicylic acid in the interaction with a necrotroph. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 80 308–317. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oil Crop Research Institute (1975). Sclerotinia disease of oilseed crops. Beijing: Agriculture Press; 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01328.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. H., Halitschke R., Kim H. B., Baldwin I. T., Feldmann K. A., Feyereisen R. (2002). A knock-out mutation in allene oxide synthase results in male sterility and defective wound signal transduction in Arabidopsis due to a block in jasmonic acid biosynthesis. Plant J. 31 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perchepied L., Balagué C., Riou C., Claudel-Renard C., Rivière N., Grezes-Besset B., et al. (2010). Nitric oxide participates in the complex interplay of defense-related signaling pathways controlling disease resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23 846–860. 10.1094/MPMI-23-7-0846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M., Brodersen P., Naested H., Andreasson E., Lindhart U., Johansen B., et al. (2000). Arabidopsis map kinase 4 negatively regulates systemic acquired resistance. Cell 103 1111–1120. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00213-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse C. M., Leon-Reyes A., Van Der Ent S., Van Wees S. C. (2009). Networking by small-molecule hormones in plant immunity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5 308–316. 10.1038/nchembio.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potuschak T., Lechner E., Parmentier Y., Yanagisawa S., Grava S., Koncz C., et al. (2003). EIN3-dependent regulation of plant ethylene hormone signaling by two arabidopsis F box proteins: EBF1 and EBF2. Cell 115 679–689. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00968-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pré M., Atallah M., Champion A., De Vos M., Pieterse C. M., Memelink J. (2008). The AP2/ERF domain transcription factor ORA59 integrates jasmonic acid and ethylene signals in plant defense. Plant Physiol. 147 1347–1357. 10.1104/pp.108.117523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina S. K., Wankhede D. P., Jaggi M., Singh P., Jalmi S. K., Raghuram B., Sheikh A. H., Sinha A. K. (2012). CrMPK3, a mitogen activated protein kinase from Catharanthus roseus and its possible role in stress induced biosynthesis of monoterpenoid indole alkaloids. BMC Plant Biol. 12:134. 10.1186/1471-2229-12-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou C., Freyssinet G., Fevre M. (1991). Production of cell wall-Degrading enzymes by the phytopathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57 1478–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou C., Freyssinet G., Fevre M. (1992). Purification and characterization of extracellular pectinolytic enzymes produced by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58 578–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M. C., Petersen M., Mundy J. (2010). Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61 621–649. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo E., Leon J., Sanchez-Serrano J. J. (1999). Cross-talk between wound signalling pathways determines local versus systemic gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 20 135–142. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins J. A., Dickman M. B. (2001). pH signaling in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: identification of a pacC/RIM1 homolog. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67 75–81. 10.1128/AEM.67.1.75-81.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y., Asamizu E., Shibata D., Nakamura Y., Kaneko T., Awai K., et al. (2001). Monitoring of methyl jasmonate-responsive genes in Arabidopsis by cDNA macroarray: self-activation of jasmonic acid biosynthesis and crosstalk with other phytohormone signaling pathways. DNA Res. 8 153–161. 10.1093/dnares/8.4.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano R., Stepanova A., Chao Q., Ecker J. R. (1998). Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: a transcriptional cascade mediated by ethylene-insensitive3 and ethylene-response-factor1. Genes Dev. 12 3703–3714. 10.1101/gad.12.23.3703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick P. E., Tiryaki I. (2004). The oxylipin signal jasmonic acid is activated by an enzyme that conjugates it to isoleucine in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16 2117–2127. 10.1105/tpc.104.023549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J., Zhang M., Zhang L., Sun T., Liu Y., Lukowitz W., et al. (2017). Regulation of stomatal immunity by interdependent functions of a pathogen-responsive MPK3/MPK6 cascade and Abscisic acid. Plant Cell 29:526. 10.1105/tpc.16.00577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y., Teshima K. M., Yokoi S., Innan H., Shimamoto K. (2009). Variations in Hd1 proteins, Hd3a promoters, and Ehd1 expression levels contribute to diversity of flowering time in cultivated rice. Proc. Natl, Acad. Sci, U.S.A. 106 4555–4560. 10.1073/pnas.0812092106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanoue T., Adachi M., Moriguchi T., Nishida E. (2000). A conserved docking motif in MAP kinases common to substrates, activators and regulators. Nat. Cell Biol. 2 110–116. 10.1038/35000065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tena G., Asai T., Chiu W. L., Sheen J. (2001). Plant mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascades. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4 392–400. 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00191-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet O., Rivas S., Mestre P., Baulcombe D. (2003). An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus. Plant J. 33 949–956. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01676.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Malek B., Van Der Graaff E., Schneitz K., Keller B. (2002). The Arabidopsis male-sterile mutant dde2-2 is defective in the ALLENE OXIDE SYNTHASE gene encoding one of the key enzymes of the jasmonic acid biosynthesis pathway. Planta 216 187–192. 10.1007/s00425-002-0906-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Yang C., Dong L., Zhu J., Wang J., Zhang S., et al. (2015). Comparative transcriptome analyses of drought-resistant and - susceptible Brassica napus L. and development of EST-SSR markers by RNA-Seq. J. Plant Biol. 58 259–269. 10.1007/s12374-015-0113-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Ngwenyama N., Liu Y., Walker J. C., Zhang S. (2007). Stomatal development and patterning are regulated by environmentally responsive mitogen-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19 63–73. 10.1105/tpc.106.048298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zheng Y., Wang X., Yang Q. (2004). Breeding of the Brassica napus cultivar Zhongshuang 9 with high-resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and dynamics of its important defense enzyme activity. Sci. Agric. Sin. 37 22–28. [Google Scholar]