Abstract

In 1998, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Adverse Childhood Experiences study established the profound effects of early childhood adversity on life course health. The burden of cumulative adversities can affect gene expression, immune system development and condition stress response. A scientific framework provides explanation for numerous childhood and adult health problems and high-risk behaviours that originate in early life. In our review, we discuss adverse childhood experiences, toxic stress, the neurobiological basis and multigenerational and epigenetic transmission of trauma and recognized health implications. Further, we outline building resilience, screening in the clinical setting, primary care interventions, applying trauma-informed care and future directions. We foresee that enhancing knowledge of the far-reaching effects of adverse childhood events will facilitate mitigation of toxic stress, promote child and family resilience and optimize life course health trajectories.

Keywords: Adverse childhood experiences, Childhood adversities, Life course, Social paediatrics

It is well established that cumulative adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can have a long lasting impact on child development and life course health. The relationship may be dose responsive. Child development is the result of an ongoing relation between biology (child’s genetic predisposition) and ecology (social and physical environment) (1). Neural connections are particularly sensitive in the first years of life and can be damaged during extreme and frequent stress periods. Toxic stress is repeated exposure to stress without the buffering of responsive relationships (2). ACEs may cumulate to have profound lifelong effects unless mitigated by protective factors (3). Resilience is the ability to overcome significant adversity. Nurturing relationships within the family and community are specifically important for developing resilience. Our review aims to enhance the knowledge of ACEs and explore factors that promote child and family resilience.

WHAT ARE ACES?

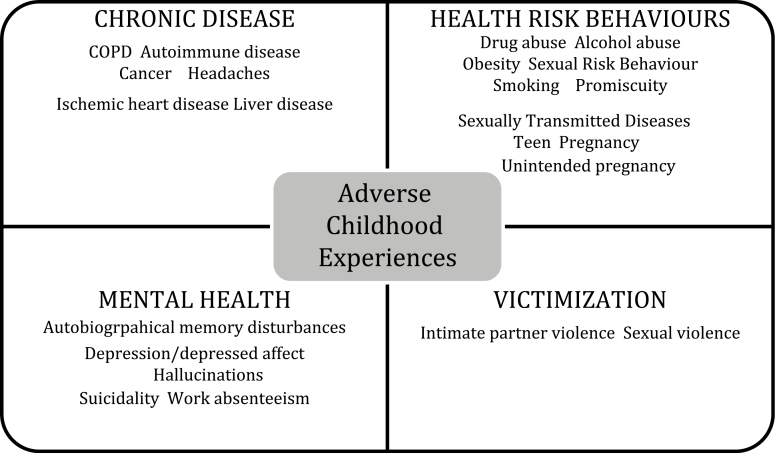

ACEs are events or continuous exposure to circumstances beyond a child’s control that may negatively impact their well-being. In 1998, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente studied the influence of ACEs on adult health outcomes. The ACEs study examined childhood exposure to abuse, neglect, domestic violence and household dysfunction (Table 1) (4). Unexpectedly, ACEs were common and cumulative. Further, a dose–response relationship was observed, whereby people with a greater number of ACEs were more likely to have poorer developmental and health outcomes. Many people had experienced childhood abuse or household dysfunction, such as parental alcohol/drug use, mental health problems or criminality. Leading risk factors for death were increased by ACEs, including smoking, alcohol abuse, obesity, physical inactivity, use of illicit drugs, promiscuity and suicide attempts. Compared to persons with no ACEs, those with four or more ACEs were twice as likely to be smokers and many times more likely to have attempted suicide, be alcoholic and have injected street drugs (5). In addition, persons were more likely to suffer from physical illnesses such as diabetes, cancer, heart disease and mental illness (4) (Figure 2). Later ACEs studies have included other adverse experiences, such as growing up in foster care, poverty (6) and exposure to violence (7). Of note, individuals with more ACEs had poorer developmental and health outcomes even after controlling for health risk behaviours, which pointed to underlying biological impacts of ACEs. These findings prompted research into the biological underpinnings, namely the influence of toxic stress.

Table 1.

Adverse childhood experiences

| 1. Recurrent physical abuse 2. Recurrent emotional abuse 3. Contact sexual abuse 4. An alcohol and/or drug abuser in the household 5. An incarcerated household member 6. Family member who is chronically depressed, mentally ill, institutionalized or suicidal 7. Mother is treated violently 8. One or no parents 9. Physical neglect 10. Emotional neglect |

Adapted from ref. (7). Note: Experiences are prior to age 18.

Figure 2.

Health risks associated with adverse childhood experiences. Note: Adapted from ref. (49). Figure demonstrates health conditions that are associated with adverse childhood experiences.

TOXIC STRESS

Learning how to cope with stress is an important part of healthy child development. When a young child’s stress response system is triggered—the child’s body responds by increasing heart rate, blood pressure and stress hormones, such as cortisol. Positive stress is exposure to a stressor that resolves with the help of a responsive caregiver and a normal and an essential part of healthy child development (e.g., a distressed child being examined by a paediatrician while being comforted by their caregiver). With tolerable stress there is exposure to a non-normative life event (e.g., loss of a family member or family divorce) that is buffered by supportive relationships and allows for resolution of the stress response. However, in the absence of supportive relationships, a toxic stress response can occur (8), which causes prolonged activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and cortisol production (9). The HPA axis plays an important role in managing metabolic and cardiovascular responses to acute and chronic stress (2). Frequent and heightened levels of cortisol exposure on the brain can lead to detrimental effects on brain structure and affect the child’s learning and behaviour (2). In addition, prolonged activation of the stress response may cause HPA dysregulation with over or under production of cortisol (10). Too much cortisol may result in immune suppression and higher risk of infection, while too little cortisol may prolong the length of inflammatory response (2).

The impact of toxic stress on stress circuits can be expressed at the molecular level. These ‘disturbances’ leave a molecular mark on the genome in the form of epigenetic modifications and result in a biological ‘embedding’ of early life experiences. This not only shapes the trajectory of future health outcomes, but can also result in substantial and lasting effects on the molecular structure of genes (10). Epigenetic changes may pass onto future generations resulting in multigenerational dysregulation of the stress response (11). Increasingly apparent, the origins of adult diseases may be traced back to developmental and biological disturbances that occurred in early life (12).

LIFE COURSE HEALTH

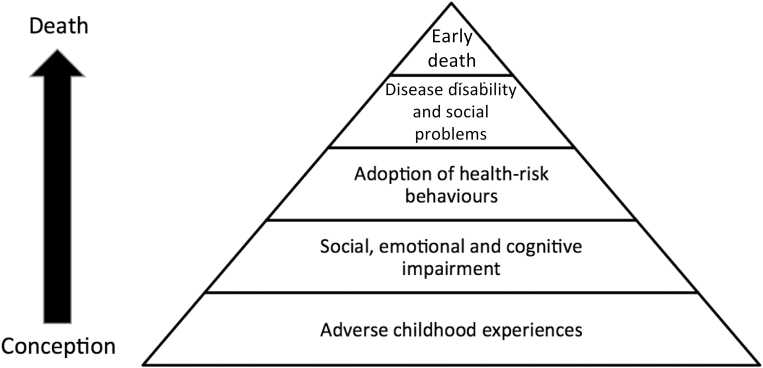

Toxic stress experienced in early life can impact the individual’s mental and physical health (Figure 1). The cumulative and dose–response effect of ACEs predicts a greater likelihood of later problems. Likewise, recent and persistent exposures (13–15), as well as combinations of ACEs (e.g., maternal mental health and poverty) (16) have greater implications for child health. Children with more ACEs have higher rates of infections, asthma and obesity compared to a general paediatric population (17). They are at increased risk of somatic complaints, such as headaches, tiredness and stomach problems, while their caregivers more frequently report poor child health (14,18). Further, mental health conditions are more common, including developmental and educational delays, poor school engagement, attention and oppositional defiant disorders and anxiety/depression (17,19,20). Adolescents are at higher risk of delinquency, internalizing negative behaviours, drug use and early pregnancy (13). Adults with adverse experiences in early childhood are more likely to have health problems and more risky health behaviours (12,21) (Figure 2). Associated physical conditions include diabetes, cancer and heart disease, while mental illnesses include depression and health risk behaviours, such as sexual risk behaviours and substance abuse (21,22).

Figure 1.

Adverse childhood experiences across the life course: the mechanism. Note: Adapted from ref. (5). Figure demonstrates adverse childhood experiences may lead to suboptimal socioemotional development and adoption of health risk. The result may contribute to poor physical and psychosocial health and early death.

BUILDING RESILIENCE

Resilience is the ability to overcome significant adversity. Importantly, resilience is built over time. Nurturing families embedded within strong neighbourhoods and communities can proactively protect from and mitigate the effects of ACEs (23–25). Promoting safe, stable and nurturing relationships can mitigate the effects of ACEs and optimize health, academic success and economic productivity (26). Resilience results from a complex interaction between the child’s genetic makeup, temperament, past experiences and social supports (27).

Modifiable child resilience factors include a child’s positive appraisal style (to assess adverse situations in a non-negative way) and cognitive and executive function skills (28). Household modifiable resilience factors include a nurturing parenting style and consistent household routines (29). Daily routines (e.g., bedtime routine, reading routine) are important for creating feelings of safety in young children and establishing the foundation for self-care, self-regulation and school-readiness. Higher levels of household routines in preschool children predicted less teacher reported hyperactivity and inattention problems, conduct problems and more pro-social behaviour in kindergarten (30). Further, community modifiable resilience factors include home-visiting programs for pregnant women and families with newborns, intimate partner violence prevention programs, social support for parents, high quality child care and sufficient financial support for lower income families (24,31,32). Finally, promoting resilience in the paediatric office include creating a medical home for children with ACEs to create longitudinal relationships, integrating behavioural health care in the paediatric office and familiarizing all paediatric staff with resources in the community (31).

SCREENING FOR ACES IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

In light of health implications, there has been a recent push to identify ACEs in the US paediatric primary care practices (33). However, Canadian guidelines are lacking. Despite this, some health care practitioners have begun screening patients for ACEs, although concerns of identification with little evidence for interventions exist. In response, researchers have suggested that clinicians focus on the child’s home environment, asking specifically about parental depression, intimate partner violence and alcohol or substance abuse, for which evidence-based interventions have been offered (34). Another approach suggests to screen all families with one basic question, ‘Has anything scary or upsetting happened to your child or your family since the last time I saw you?’ (31).

A number of formal screening questionnaires to identify ACEs in paediatric primary care have been published (35). The Safe Environment for Every Kid Model (SEEK) is a 20-item parent screening questionnaire to identify targeted psychosocial risk factors (e.g., substance abuse, maternal depression). A cluster randomized control trial which assessed the SEEK model in US paediatric primary care demonstrated that using this questionnaire led to significant improvement in several psychosocial outcomes, including greater adherence to their child’s medical treatment and reduced involvement of child protective services (36). Recently, the Center for Youth Wellness developed an ACEs questionnaire to identify patients at increased risk of chronic health problems, learning difficulties and mental and behavioural health problems; there is a version for parents of children and adolescents and a self-report adolescent version. The instrument consisted of two sections: the first section screened for the traditional ten ACEs and the second section included items assessing for exposure to additional life stressors identified by community stakeholders (e.g., involvement in foster care, bullying, community violence). This questionnaire is free and takes approximately 5 minutes to complete, however formal evaluation has not been performed (37).

PRIMARY CARE INTERVENTIONS

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) describes the reduction of toxic stress in young children to be a high priority for paediatrics (38). Although evidence for sustainable and effective approaches is limited, integration of interventions into primary care visits is feasible and can favourably affect clinical practice and family outcomes (3,39).

Paediatric providers are challenged by insufficient training. However, didactic instructions have included teaching clinicians to use screening questionnaire (40,41) and recognizing toxic stress (34,42). After screening, procedures to address identified problems have included referral to parenting programs (42), a telephone-based parenting curriculum (42), referral to a social worker (36) or handing out a wallet-size referral card (43). Further, experiential interventions have included having resident physicians spend a rotation with ambulatory clinicians or visit community agencies to learn about biosocial and developmental problems (44), conducting role play sessions (45), interacting with social workers (41) and providing clinicians with a manual on psychosocial issues (42). Training has resulted in improved screening rates (41,45), perceived competence and more positive attitudes toward patients with psychosocial difficulties (46). Furthermore, outcomes among parents and children found reduction in the behavioural consequences of ACEs (36) and increase in referral to community resources (47).

APPLYING TRAUMA-INFORMED CARE

Beyond the implications on development and overall health, ACEs may result in trauma. When screening for ACEs practitioners should be aware of the potential for disclosure of trauma and be able to implement trauma-informed care (TIC). For the health care provider, TIC encompasses inclusion of an understanding of trauma into routine health care and the treatment experience, and provides emotional support, positive coping and guidance for recovery (48). The principles are 1) realizing and understanding the impact of trauma; 2) recognizing trauma in children, families and health care providers; 3) responding by applying knowledge into practice and 4) resisting retraumatization (49). TIC requires collaboration with community partners at all levels to actively address the needs of traumatized children. From the trauma perspective, the insightful question may be ‘what happened to you?’ rather than ‘what is wrong with you?’ (50).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Policy implications

The neurobiological basis of ACEs suggest the possibility that supporting healthy early childhood development can prevent consequences (51,52). Early strategies that identify and support at-risk children and families may decrease the need for subsequent interventions. Policies and programs must be directed toward high quality day care, early childhood education, child protection services, mental health and family income support. However, barriers in health care include the relative lack of health care spending on paediatric preventive services and emphasis on treatment rather than pre-emptive parental guidance (51). Promoting caring, safe and supportive relationships within the family and community can prevent or reverse the adverse outcomes of toxic stress (23,25,53,54).

Professional development

Health care practitioner education is a key component to offering TIC. Physicians are reluctant to screen for ACEs for many reasons, including lack of time, reimbursement or training and have discomfort in discussing trauma. However, when offered professional training, practitioners are more likely to inquire and feel comfortable about ACEs (28). Further, evidence-based clinician training resources (Table 2) should be integrated into paediatric training programs and continuing medical education.

Table 2.

Adverse childhood experiences: educational and professional development resources

| 1. | Center on the Developing Child – Harvard University Excellent website with interactive videos, position statements, and in-depth scientific reviews about toxic stress, resilience and child development |

http://developingchild.harvard.edu |

| 2. | Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Online resources and training to promote children’s health, development and safety- and help prevent child abuse and neglect |

http://theinstitute.umaryland.edu/frames/seek.cfm |

| 3. | The Resilience Project – American Academy of Pediatrics Overview of clinical assessment tools to provide additional support for paediatricians to identify and effectively care for children and adolescents who have been exposed to violence |

https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/resilience/Pages/Clinical-Assessment-Tools.aspx |

| 4. | Center for Youth Wellness; Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (CYW ACE-Q) and user guide | http://sgiz.mobi/s3/ab0291ef106d |

| 5. | Childhood Trauma Toolkit; Center for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) | https://www.porticonetwork.ca/web/childhood-trauma-toolkit/developmental-trauma/what-is-developmental-trauma |

| 6. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Discusses Adverse Childhood Experiences, child maltreatment with excellent presentation graphics. |

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/resources.html |

CONCLUSION

ACEs result in detrimental effects on life course health and negative adult health outcomes. Adverse exposures in childhood are common, inter-related and dose-dependent. ACEs are a major determinant of subsequent health and well-being impacting social cost, health care utilization and quality of life. The future research agenda calls for basic scientists to develop practice-friendly biomarkers; for public health physicians to implement evidence-based interventions; for teachers to find effective methods to educate trainees and practitioners; and for clinicians to support nurturing families and strengthen neighbourhood and community resilience (26). We must take advantage of every opportunity to translate our knowledge of ACEs into practice and policy.

Acknowledgements

Financial Disclosure: There are no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose from all identified authors.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest or financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose from all identified authors.

References

- 1. Shonkoff JP, Garner AS; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012;129:e232–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnson SB, Riley AW, Granger DA, Riis J. The science of early life toxic stress for pediatric practice and advocacy. Pediatrics 2013;131:319–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Flynn AB, Fothergill KE, Wilcox HC, et al. . Primary care interventions to prevent or treat traumatic stress in childhood: A systematic review. Acad Pediatr 2015;15:480–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holman DM, Ports KA, Buchanan ND, et al. . The association between adverse childhood experiences and risk of cancer in adulthood: A systematic review of the literature. Pediatrics 2016;138:81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. . Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner H, Hamby S. Improving the adverse childhood experiences study scale. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cronholm PF, Forke CM, Wade R, et al. . Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. Am J Prev Med 2015;49:354–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Center on the Developing Child. Toxic Stress 2016. http://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/ (Accessed June 19, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schloesser RJ, Manji HK, Martinowich K. Suppression of adult neurogenesis leads to an increased hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis response. Neuroreport 2009;20:553–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bucci M, Marques SS, Oh D, Harris NB. Toxic stress in children and adolescents. Adv Pediatr 2016;63:403–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Pinal C. The developmental origins of adult disease. Matern Child Nutr 2005;1:130–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shonkoff JP, Garner AS; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012;129:e232–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thornberry TP, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The importance of timing: The varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Dev Psychopathol 2001;13:957–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Flaherty EG, Thompson R, Dubowitz H, et al. . Adverse childhood experiences and child health in early adolescence. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:622–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lefebvre R, Fallon B, Van Wert M, Filippelli J. Examining the relationship between economic hardship and child maltreatment using data from the Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2013 (OIS-2013). Behav Sci 2017;7:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lanier P, Maguire-Jack K, Lombardi B, Frey J, Rose RA. Adverse childhood experiences and child health outcomes: Comparing cumulative risk and latent class approaches. Matern Child Health J 2017:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Forkey HC, Morgan W, Schwartz K, Sagor L. Outpatient clinic identification of trauma symptoms in children in foster care. J Child Fam Stud 2016;25:1480–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Flaherty EG, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ, et al. . Adverse childhood exposures and reported child health at age 12. Acad Pediatr 2009;9:150–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bethell C, Gombojav N, Solloway M, Wissow L. Adverse childhood experiences, resilience and mindfulness-based approaches: Common denominator issues for children with emotional, mental, or behavioral problems. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2016;25:139–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Boyle M, Taillieu T, Cheung K, Sareen J. Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. CMAJ 2014:cmaj. 131792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Centers for Disease and Prevention. Violence Prevention. 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/journal.html (Accessed June 28, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gilbert LK, Breiding MJ, Merrick MT, et al. . Childhood adversity and adult chronic disease: An update from ten states and the District of Columbia, 2010. Am J Prev Med 2015;48:345–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ford DE. The community and public well-being model: A new framework and graduate curriculum for addressing adverse childhood experiences. Acad Pediatr 2017;17:S9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sege RD, Harper Browne C. Responding to ACEs with hope: Health outcomes from positive experiences. Acad Pediatr 2017;17:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ellis WR, Dietz WH. A new framework for addressing adverse childhood and community experiences: The building community resilience model. Acad Pediatr 2017;17:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garner AS, Forkey H, Szilagyi M. Translating developmental science to address childhood adversity. Acad Pediatr 2015;15:493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ungar M. Practitioner review: Diagnosing childhood resilience–a systemic approach to the diagnosis of adaptation in adverse social and physical ecologies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2015;56:4–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kleiman EM, Chiara AM, Liu RT, Jager-Hyman SG, Choi JY, Alloy LB. Optimism and well-being: A prospective multi-method and multi-dimensional examination of optimism as a resilience factor following the occurrence of stressful life events. Cogn Emot 2017;31:269–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cohen JA, Kelleher KJ, Mannarino AP. Identifying, treating, and referring traumatized children: The role of pediatric providers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:447–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ferretti LK, Bub KL. Family routines and school readiness during the transition to kindergarten. Early Education and Development 2017;28:59–77. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Traub F, Boynton-Jarrett R. Modifiable resilience factors to childhood adversity for clinical pediatric practice. Pediatrics 2017:e20162569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hargreaves MB, Pecora PJ, Williamson G. Aligning community capacity, networks, and solutions to address adverse childhood experiences and increase resilience. Acad Pediatr 2017;17:7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. American Academy of Pediatrics. Trauma Guide 2017. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-foster-care-america/Pages/Trauma-Guide.aspx (Accessed May 05, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bair-Merritt MH, Zuckerman B. Exploring parents’ adversities in pediatric primary care. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:313–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bethell CD, Carle A, Hudziak J, et al. . Methods to assess adverse childhood experiences of children and families: Toward approaches to promote child well-being in policy and practice. Acad Pediatr 2017;17:51–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, Kim J. Pediatric primary care to help prevent child maltreatment: The Safe Environment for Every Kid (seek) model. Pediatrics 2009;123:858–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Center for Youth Wellness. CYW ACE-Q and User Guide 2017. http://centerforyouthwellness.org/CYW-ACE-Q-and-User-Guide (Accessed May 22, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 38. Garner AS, Shonkoff JP; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: Translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics 2012;129:e224–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Planey B. Aces and state maternal child health programs. Acad Pediatr 2017;17:30–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dubowitz H, Lane WG, Semiatin JN, Magder LS, Venepally M, Jans M. The safe environment for every kid model: Impact on pediatric primary care professionals. Pediatrics 2011;127:e962–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Feigelman S, Dubowitz H, Lane W, Grube L, Kim J. Training pediatric residents in a primary care clinic to help address psychosocial problems and prevent child maltreatment. Acad Pediatr 2011;11:474–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Borowsky IW, Mozayeny S, Stuenkel K, Ireland M. Effects of a primary care-based intervention on violent behavior and injury in children. Pediatrics 2004;114:e392–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Feigelman S, Dubowitz H, Lane W, Grube L, Kim J. Training pediatric residents in a primary care clinic to help address psychosocial problems and prevent child maltreatment. Acad Pediatr 2011;11:474–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Berg RA, Rimsza ME, Eisenberg N, Ganelin RS. Evaluation of a successful biosocial rotation. Am j Dis Child 1983;137:1066–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Berger RP, Bogen D, Dulani T, Broussard E. Implementation of a program to teach pediatric residents and faculty about domestic violence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:804–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bethell CD, Newacheck P, Hawes E, Halfon N. Adverse childhood experiences: Assessing the impact on health and school engagement and the mitigating role of resilience. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:2106–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Garg A, Butz AM, Dworkin PH, Lewis RA, Thompson RE, Serwint JR. Improving the management of family psychosocial problems at low-income children’s well-child care visits: The WE CARE project. Pediatrics 2007;120:547–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Marsac ML, Kassam-Adams N, Hildenbrand AK, et al. . Implementing a trauma-informed approach in pediatric health care networks. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:70–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Trauma-informed Approach and Trauma-specific Interventions 2015. https://www.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions (Accessed September 09, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 50. Szilagyi M, Halfon N. Pediatric adverse childhood experiences: Implications for life course health trajectories. New York, NY: Elsevier Science Inc, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Forrest CB, Riley AW. Childhood origins of adult health: A basis for life-course health policy. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Braveman P, Barclay C. Health disparities beginning in childhood: A life-course perspective. Pediatrics 2009;124:S163–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Center on Developing Child. The Impact of Early Adversity on Children’s Development (In Brief) 2007. http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu (Accessed September 09, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bethell CD, Solloway MR, Guinosso S, et al. . Prioritizing possibilities for child and family health: An agenda to address adverse childhood experiences and foster the social and emotional roots of well-being in pediatrics. Acad Pediatr 2017;17:36–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]