Abstract

Children and youth with developmental and mental health conditions require a wide range of clinical supports and social services to improve their quality of life. However, few children and youth are currently able to adequately access these clinical, community and social services, and newcomers or those living in poverty are even further disadvantaged. Patient navigator programs can bridge this gap by facilitating connections to social services, supporting family coping strategies and advocating for patient clinical services. Although there are few paediatric-focused patient navigator programs in the literature, they offer the potential to improve short and long-term health outcomes. As social and clinical services, particularly for developmental and mental health conditions, become increasingly complex and restricted, it is important that physicians and policymakers consider implementing patient navigator programs with a rigorous evaluation framework to improve accessibility and health outcomes. This can ultimately facilitate policymakers in creating more equitable resources in challenging fiscal climates.

Keywords: Child development disorders, Child health services, Mental health, Patient navigation

Access to appropriate resources for children and youth with mental health and developmental issues continues to be a central topic of discussion and source of frustration for families and care providers alike. While efforts have been made to improve access to childhood and youth mental health programs, these programs remain inaccessible for many families, impairing optimal health and developmental outcomes for our current and future generations. For children who have developmental disorders, patient navigation can promote access to early intervention and critical resources. Of the one in five Canadians who will face mental health problems in their lifetime, more than 70% of these illnesses present in childhood and adolescence (1). Canadian youth suicide rates have risen to the third highest in the industrialized world, and only one in five children with mental health and developmental illnesses receive the proper treatment and attention that they require (2). Mental health and developmental well-being must be addressed as early as possible in a child or youth’s life, to minimize the impact on their developmental and life trajectory (3).

Large income gaps further affect the health of children and youth and their ability to access basic resources in paediatric care (4). Children and youth living in low-income households who present with developmental challenges are often noticeably lagging in comparison to their more affluent peers due to factors such as access to transportation, cultural and linguistic barriers, lack of health insurance, discrimination and stigmatization (4).

In Ontario, the Ministry of Children and Youth Services has acknowledged that the current service delivery system does not build in surveillance or ways of ensuring accountability such that families are able to access care in an equitable and timely fashion (5). For instance, after a child or youth has been diagnosed with a mental health or developmental challenge by their primary caregiver, wait times to see a developmental specialist can be as long as 12 to 18 months (6). In the USA, the 2005/2006 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs described an unmet demand for care coordination and health care access for patients and their families who participated in the study (7). Families who reported having received adequate, coordinated care experienced increased family-centred care, decreased problems with referrals for specialty care, less school days missed because of illness, reduced odds of visiting the emergency department twice in 12 months, reduced out of pocket expenses and reduced family financial burden (7).

Patient Navigation Programs (PNP), also described as care coordination programs in the literature, were developed and implemented with a goal to improve health and social care service delivery, to aid in management of specific health and population needs and to improve patient wellbeing (8). The first PNP was pioneered in Harlem, New York by Harold Freeman as a means to promote increased health screening and timely treatment, based on the idea that patient navigation could alleviate barriers to these services. After the successful implementation of Freeman’s program, it quickly became a leading example of patient navigation in health care (9). Since then, patient navigation programs have been implemented in adult medicine to promote better adherence to follow up and clinical care (8). Although children and youth with developmental and mental health concerns need patient navigation, few programs have been implemented and evaluated in this population, and their quality is variable (10). One such PNP providing patient navigation for children with autism spectrum disorder reported parents were better able to follow up with appointments for both clinical and social supports (11). Another pilot study found increased access to early intervention in children with developmental delays in an urban setting (12).

In Canada, there are few paediatric patient navigation programs that have been studied, and none focused on young children. One example is the Family Navigation Project (FNP) piloted by Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in 2013 to provide support to youth aged 13 to 26 years with mental health or addiction concerns (13). This project paired participating youth and their families with a patient navigator who provided individualized support and connected patients to appropriate specialized care. Preliminary data from this study suggested that implementation of the FNP was correlated with 90% patient satisfaction with the care they are being provided (13). However, the Family Navigation Project did not assign a navigator to patients who fell below the 13 to 26 age range (13). For children and youth with additional vulnerabilities, including those living in poverty, living in inner-city environments and immigrant/refugee families, the need for navigation is even greater (12,14). These barriers further contribute to resource access issues in the mental health and addictions system as described above, yet well-studied navigation programs are scarce in these neighbourhoods and provide little or no measurable data.

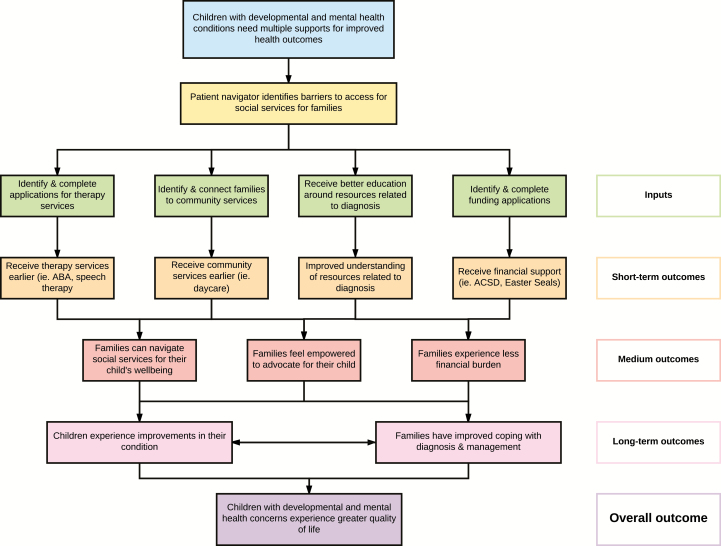

Paediatric patient navigators can light a path toward earlier intervention in children and youth struggling with mental health and development issues. As outlined in Figure 1, patient navigation is a useful strategy to improve both short-term and long-term health outcomes in these patients. Through educating patient and family about resources, identifying needs and facilitating access to available community and therapeutic resources, patient navigation may reduce wait times for services and improve a family’s collective sense of empowerment, and subsequently decrease stressors on a family by improving their ability to cope. For vulnerable paediatric populations, including those living in poverty and newcomer families, patient navigators may be especially beneficial for accessing necessary supports. It is important, however, that strong program evaluation frameworks are embedded in the implementation of paediatric navigator programs, extending beyond patient satisfaction to include measures of clinical and cost-effectiveness, system utilization and self-efficacy.

Figure 1.

Intervention impact model demonstrating the short, medium and long-term health outcomes from pediatric patient navigation.

Given the current political and economic climate, it is likely that there will be greater complexity of patient needs on an already strained system. Thus, paediatric patient navigation programs become a crucial step in ensuring fair access to services and toward health equity. Importantly, with thoughtful design and evaluation, these programs may provide key insights into service utilization, directing future program delivery models and economic and social impacts. It is imperative that physicians and child and youth health advocates adapt and develop pathways to ensure our patients receive the care and treatment they need, from the clinic to the community centre. Patient navigation programs can guide children and youth and their families through a complicated web of oft-scarce but much-needed social services. The ultimate purpose of patient navigation is to improve health outcomes through patient and family education, providing timely access to resources and alleviating obstacles to care due to socioeconomic disparities. Patient navigation programs also function as an opportunity to evaluate and measure the impacts of community-based programs on child and community heath. Combining thoughtfully designed programs with innovative but rigorous surveillance of outcome measures will help guide future policymakers toward brighter health for tomorrow’s children and youth.

In summary, there remain key gaps in access to essential services for child and youth mental health and developmental disorders, due to scarcity, complexity in health systems and socioeconomic disparities. Patient navigation programs offer a clear solution for many families, by facilitating direct connections to services and funding, and supporting family education. Patient navigation programs are a worthy investment of time and money to optimize patient care for our most vulnerable patients. While more programs need to be developed and implemented, they also need to be evaluated to demonstrate their full impact on health outcomes.

References

- 1. Government of Canada [Internet]. The human face of mental health and mental illness in Canada. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; c2006 (cited August 9, 2017). <http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/human-humain06/pdf/human_face_e.pdf> (accessed August 9, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canadian Mental Health Association [Internet]. CMHA; c2017 [cited 2017 June 8]. CMHA: Facts About Mental Health; [about 3 screens]. <http://www.cmha.ca/media/fast-facts-about-mental-illness/#.V5kG25ODGko> (accessed June 8, 2017).

- 3. Hertzman C. The significance of early childhood adversity. Paediatr Child Health 2013;18(3):127–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferguson H, Bovaird S, Mueller M. The impact of poverty on educational outcomes for children. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(8):701–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Office of the Provincial Advocate for Children and Youth for Ontario [Internet]. Statement on Child and Youth Mental Health in Ontario Report Cited June 8, 2017. <https://provincialadvocate.on.ca/documents/en/Statement_of_Child_and_Youth_Mental_Health_in_Ontario.pdf> (accessed June 8, 2017).

- 6. Carter A. Hamilton pediatrician says kids ‘sinking’ because of psych test wait times. Hamilton: CBC News; January 23, 2015; <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/hamilton/news/hamilton-pediatrician-says-kids-sinking-because-of-psych-test-wait-times-1.2928150> (accessed June 8, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turchi RM, Berhane Z, Bethell C, Pomponio A, Antonelli R, Minkovitz CS. Care coordination for CSHCN: Associations with family-provider relations and family/child outcomes. Pediatrics 2009;124(Suppl 4):S428–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Valaitis RK, Carter N, Lam A, Nicholl J, Feather J, Cleghorn L. Implementation and maintenance of patient navigation programs linking primary care with community-based health and social services: A scoping literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17(1):116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Freeman HP. Patient navigation: A community centered approach to reducing cancer mortality. J Cancer Educ 2006;21(1 Suppl):S11–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brown NM, Green JC, Desai MM, Weitzman CC, Rosenthal MS. Need and unmet need for care coordination among children with mental health conditions. Pediatrics 2014;133(3):e530–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roth BM, Kralovic S, Roizen NJ, Spannagel SC, Minich N, Knapp J. Impact of autism navigator on access to services. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2016;37(3):188–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guevara JP, Rothman B, Brooks E, Gerdes M, McMillon-Jones F, Yun K. Fam Syst Health 2016;34(3):281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Markoulakis R, Weingust S, Foot J, Levitt A. The Family Navigation Project: An innovation in working with families to match mental health services with their youth’s needs. Can J Commun Ment Health 2016;35:63–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nicholas D, Fleming-Carroll B, Durrant M, Hellmann J. Examining pediatric care for newly immigrated families: Perspectives of health care providers. Soc Work Health Care 2017;56(5):335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]